Abstract

Extramammary Paget’s disease (EMPD) is a rare entity, especially in the perinoscrotal region, and typically presents in elderly white patients as a pruritic white or red patch in the area of distribution of apocrine glands. Typically, it affects a single site. Since its manifestations are insidious and easily misdiagnosed, the appropriate management is delayed. Management of this problem is complex and effective treatment can not only lower recurrence rates but also provide an optimal reconstructive result.

The present report describes three patients with scrotal EMPD. Based on literature search, the etiopathology, diagnosis and management of these lesions is discussed. Reconstructive options, with special emphasis on scrotal lesions, are also discussed.

Keywords: Cutaneous pruritic patch, Extramammary Paget’s disease, Scrotal lesion

Abstract

La maladie de Paget extramammaire (MPEM) est une maladie rare qui se manifeste surtout dans la région périnéoscrotale et qui se présente généralement chez des personnes âgées de race blanche sous forme de tache prurigineuse rougeâtre ou blanchâtre dans la zone de distribution des glandes apocrines. D’ordinaire, elle atteint un seul foyer. Puisque ses manifestations sont insidieuses et faciles à mal diagnostiquer, sa prise en charge convenable est retardée. D’ailleurs, cette prise en charge est complexe. Toutefois, un traitement efficace peut non seulement faire chuter le taux de récidive mais également assurer une reconstruction optimale. Le présent rapport décrit trois patients atteints d’une MPEM scrotale. Compte tenu d’une recherche dans la documentation scientifique, l’étiopathologie, le diagnostic et la prise en charge de ces lésions sont abordés. Les possibilités de reconstruction, surtout axées sur les lésions scrotales, sont également examinées.

Sir James Paget first described mammary Paget’s disease in 1874. He noted “chronic affectations of the skin of the nipple of the areola and very often succeeded by formation of schirrous cancer in the mammary gland” (1). It was not until 1888 that Crocker described extramammary Paget’s disease (EMPD) (2). Scrotal EMPD is rare, and its diagnosis and management are complex. Accurate diagnosis is typically delayed due to a variety of reasons, and usually the lesion is fairly advanced at the time of definitive therapy. Management of this problem requires a thorough understanding of the etiopathology of this disease entity and its prognostic course. Also fundamental to the treatment of EMPD is an acute awareness of the growing numbers of treatment modalities that are useful in specific circumstances. Used effectively, these therapeutic strategies not only lead to lower recurrence rates, but also provide an optimal reconstructive result.

To increase awareness of this unusual disease, our report describes three patients with scrotal EMPD. Based on a literature search, we discuss etiopathology, diagnosis and management of these lesions. Reconstructive options, with special emphasis on scrotal lesions, are also discussed.

CASE PRESENTATIONS

Case 1

A 71-year-old white man presented three months after developing a pruritic erythematous rash on the left side of his scrotum, that extended to the medial aspect of his thigh (Figure 1). The lesion was initially misdiagnosed as a tenia, but local skin treatments were ineffective. Subsequently, a punch biopsy revealed EMPD. Rectal examination was negative for rectal or prostatic masses and the serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) was negative. Local treatment with fluorouracil (5-FU) was unsuccessful. A wide local excision of the lesion with a margin of 1 cm was performed. Each quadrant was sampled by frozen section and excision was performed until margins were clear. The resultant defect was 16 cm×17 cm×10 cm. The fascia covering the left testis was exposed, as were the cord structures supporting it. Reconstructive surgery involved a scrotal fasciocutaneous advancement using the right scrotal sac to cover the scrotal defect. The defect on the medial thigh required a local advancement flap from the adjacent area. The final postoperative result is seen in Figure 2. Histology confirmed EMPD (Figures 3 and 4). No adjuvant therapy was considered. The wounds healed uneventfully and the patient remains disease-free for the past 17 months.

Figure 1).

Preoperative view of patient in Case 1 reveals an erythematous area along the medial aspect of the thigh and extending to the scrotum on the right side. Note the lack of ulceration and a seemingly well-defined macroscopic border

Figure 2).

Postoperative view following complete resection of the lesion followed by reconstruction of the scrotal defect using a fasciocutaneous advancement flap from the scrotum itself and a rhomboid flap from the medial aspect of the thigh to close the defect in that area

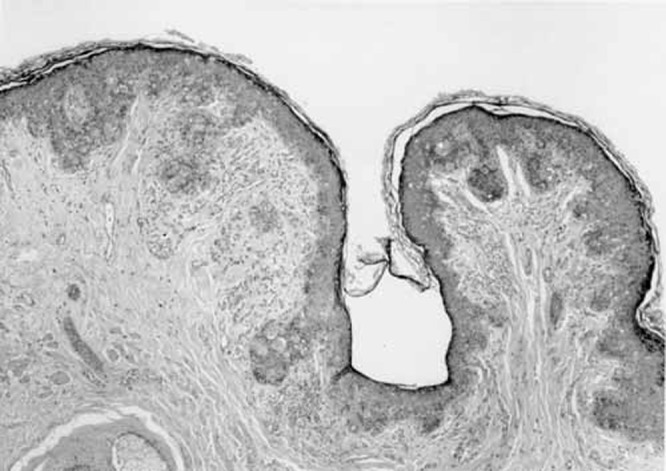

Figure 3).

Low power microscopic view of the specimen reveals tumour cells infiltrating the skin and the adnexa

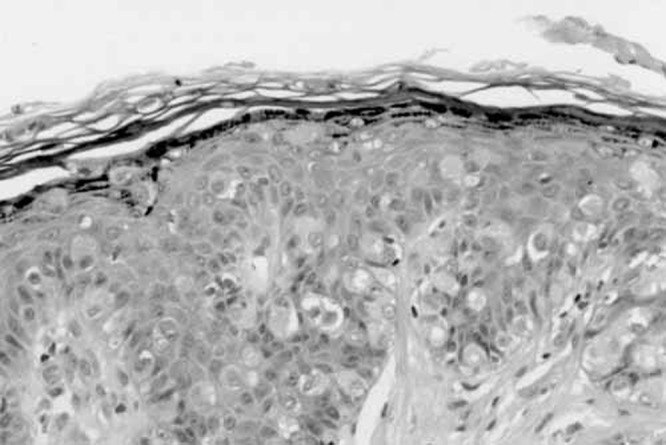

Figure 4).

High power microscopy confirm the presence of Paget cells – abundant and large, these cells are characteristic with pale cytoplasm.Distributed singly and in groups they are noted throughout the epidermis and the epithelia of the adnexa. Upper regions of the dermis show dense inflammatory cells

Case 2

A 76-year-old white man, treated unsuccessfully for an eczematous lesion on his scrotum before the diagnosis of EMPD, presented for excision biopsy of the scrotal skin. The specimen measured 6.5 cm ×6 cm×1.2 cm and included skin and subcutaneous tissue. Deep margins were marked with methylene blue. The resultant skin and soft tissue defect was primarily closed in layers, with good postoperative healing of the wound. The patient has been disease-free for the past 18 months. Histologically, the margins were free. Tumour cells infiltrated through the epidermis and skin adnexa with a page-toid pattern. Immunohistochemical stains were positive for cytokeratin, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and mucicarmine and negative for high mucin production (HMP)-45, S-100, and PSA. No underlying tumour was found.

Case 3

A 66-year-old white man presented with a diffuse 3 cm×4 cm slightly indurated erythematous patch in the perineum. A colonoscopy performed two months prior was negative for malignancy. An incisional biopsy revealed EMPD. Subsequently, the patient underwent Mohs microsurgery (MMS) requiring three layers of excision owing to the lateral epidermal spread of the tumour. The final defect of 4 cm×5 cm was closed primarily. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis. Atypical intraepidermal Paget cells were identified that stained positive for CEA and cytokeratin but negative with S-100 immunostain. Follow-up visits six months postoperatively reveal no evidence of disease.

DISCUSSION

Incidence

Commonly occurring in apocrine gland-bearing skin, especially on the vulva (65%), EMPD has also been reported on the scrotal (14%) and perianal regions (20%), buttocks, eyelids, ear canal and other sites. It generally appears between ages of 50 to 80 years, with an increased predilection in Caucasians and women (1:3) (3). The overall incidence is difficult to determine because most reported cases are anecdotal. Ectopic EMPD has been rarely described in cutaneous areas devoid of apocrine glands (4).

Etiology

Three hypotheses have been made regarding the etiopathology of EMPD. The first hypothesis is that it arises from underlying cutaneous adnexa (apocrine or eccrine) (5–8). The second hypothesis examines a correlation between metastasis from gastrointestinal (9) or genitourinary malignancies (10). While this unusual feature has been disparately described in the literature, a recent series (11) showed that vulvar EMPD is associated with an adnexal adenocarcinoma in 7% of cases and an internal visceral malignancy in 14%. The third hypothesis suggests that EMPD is a multifocal malignant transformation of pluripotent germinative epidermal cells (12,13). Overall, the etiological hypotheses yields one major lead in terms of management of EMPD – that one must make every attempt to exclude a synchronous gastrointestinal or genitourinary malignant lesion.

Diagnosis

EMPD typically presents in elderly white patients as a pruritic (3) white or red patch in the area of distribution of apocrine glands. Typically it affects a single site. However, Japanese investigators have documented triple lesions involving the anogenital regions and axilla simultaneously (14). The microscopic appearance of EMPD is virtually identical to that of mammary Paget’s disease (MPD). Despite these similarities, the two conditions differ with respect to histogenesis, staining properties and the relative frequency of underlying malignancy. EMPD is classified as primary or secondary. Primary EMPD is derived from epidermis or its appendages (13). Secondary EMPD denotes an epidermatropism wherein intraepidermal invasion or metastasis occurs from visceral malignancies (3), or urogenital organs (15). Differential diagnoses of EMPD include candida, tinea, seborrheic dermatitis, lichen sclerosis, histiocytosis, psoriasis, eczema, necrolytic migratory erythema and contact dermatitis. EMPD is characterized histologically by intraepidermal proliferation of unique tumour cells, named Paget cells. On routine staining these cells appear identical to ones seen in classic areolar-type MPD. Paget cells of EMPD are characterized by strong cytoplasmic staining for Periodic Acid Schiff (PAS), muccarmine and Alcian blue indicating the presence of mucopolysaccharides. EMPD is CEA-positive in 93% to 100% of cases, whereas MPD is more frequently negative for CEA, PAS, mucin and Alcian blue. The tumour may also be confused with pagetoid melanoma, a tumour that universally stains positive for S-100 protein (16). Both EMPD and MPD are S-100-negative, allowing for easy differentiation (17,18).

Delayed diagnosis of an average of one year from onset of symptoms has been reported (19). Lack of specific clinical findings, and delayed histological sampling are the main reasons for misdiagnosis and extended periods of topical or systemic medical management.

Management

EMPD is associated with concurrent visceral malignancy in 12% to 50% of cases (20). The frequency and site of associated malignancies differ in various anatomic locations. Chandra (21) observed that the location of the EMPD predicts the underlying malignancy. Vulvar and scrotal Paget’s disease are often associated with gastrointestinal malignancies, especially of the colon and rectum. This strong correlation between the presence of EMPD and underlying malignancy warrants lifelong endoscopic and radiographic evaluation to exclude this possibility.

EMPD that has well-defined margins with or without underlying adenocarcinoma is treated with wide local excision. Recurrence rates of 15% to 50% have been described, depending upon the site and type of resection (15, 22,23). Newer primary and adjuvant strategies for preventing recurrences are MMS, radiation, chemotherapy, CO2 laser ablation and photodynamic therapy. Furthermore, the ideal therapy for EMPD is one that addresses the complexities of the disease process, which include multicentricity, irregular clinical margins or indeterminate histological margins that extend well beyond the clinically uninvolved margins (24).

Although local wide excision, MMS or chemoradiation were effective when used alone for the treatment of noninvasive, well-defined unicentric lesions, none of these used alone is well suited for invasive, poorly defined, multicentric EMPD.

Recurrence rates were lower in patients treated with MMS than with wide local resection (3). The addition of frozen sections to the wide local excision is not as effective as MMS because MMS examines the entire histological margin, whereas conventional frozen sections sample barely 5% of the margin, missing lesions that are typically discontinuous.

Noninvasive EMPD responded well to primary and adjuvant radiation therapy, whereas the invasive type was poorly controlled with radiation therapy alone, with a 50% recurrence. As adjuvant therapy, radiation was effective in both types of lesions (25,26).

Chemotherapy remains controversial. Topical 5-FU application was effective for patients with scrotal and penile EMPD (27). Topical bleomycin has also been used with variable results (28). Spontaneous clinical resolution with histological persistence of EMPD in response to topical 5-FU has been described (29) and may be particularly useful when extent of disease or general health preclude surgery or radiation therapy. Systemic chemotherapy using carboplatin, calcium folate and 5-FU has been found to be effective in patients with perineal EMPD (30).

Besides adjuvant therapy, other methods of obtaining better control rates include perioperative tumour mapping (31). We did not use this technique in any of our cases, but will certainly consider it for future patients. The method involves using photodynamic substances such as fluorescin, which is taken up by EMPD cells preferentially to normal tissue. Besides ensuring completeness of excision, this method allows for conservation of uninvolved tissue leading to an optimal reconstructive result. Used before modified radical vulvectomy for EMPD, fluorescin injected preoperatively showed a sensitivity and specificity of 99.8% and 98%, respectively, for the detection of EMPD margins and a successful margin-free excision. Tagged cytokeratin antibodies (18) are also specifically taken up by EMPD cells and can be used for mapping, although the sensitivity and specificity of this modality is controversial (32).

CONCLUSIONS

In conclusion, we emphasize the following salient points in management of EMPD.

Early diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion. EMPD must be considered in patients with ill-defined lesions in apocrine gland-bearing areas that are recalcitrant to conventional therapy.

If an excision biopsy confirms EMPD, a thorough search must be made to determine whether it is a primary or a secondary EMPD with an underlying adenocarcinoma. Larger lesions may be amenable to an incisional biopsy facilitating an accurate diagnosis before definitive surgery.

If noninvasive, well-defined and unicentric on histology, wide local excision may suffice. While no consensus on adequacy of margins exists, frozen section control may provide a suitable guideline. Mohs treatment may be beneficial in carefully selected cases.

In invasive lesions with ill-defined margins and multicentricity, adjuvant therapy is essential. High recurrence rates demand a close follow up for long periods of time. Guidelines on frequency and duration of follow up are yet to be defined.

Perioperative mapping using fluorescin is useful and must be considered before a wide local excision is undertaken.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the efforts of Judy Knight, Librarian, Akron General Medical Center for her assistance with the preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Paget J. On disease of the mammary areola preceding cancer of the mammary gland. St Bartholomew’s Hosp Rep. 1874;10:87–9. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kageyama N, Izumi AK. Bilateral scrotal extramammary Paget’s disease in a Chinese man. Int J Dermatol. 1997;36:695–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.1997.00044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zollo JD, Zeitouni NC. The Roswell Park Cancer Institute experience with extramammary Paget’s disease. Br J Dematol. 2000;142:59–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heymann WR. Extramammary Paget’s disease. Clin Dermatol. 1993;11:83–7. doi: 10.1016/0738-081x(93)90101-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Merot Y, Mazoujian G, Pinkus G, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease of the perianal and perineal regions. Evidence of apocrine derivation. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:750–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hashimoto T, Inamoto N, Nakamura K. Triple extramammary Paget’s disease: Immunohistochemical studies. Dermatologica. 1986;173:174–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsuji T. Mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease: Expression of CA15-3, Ka-93, CA 19-9, and CD44 in Paget cells and adjacent normal skin. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb08617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nadji M, Morales AR, Girtanner RE, et al. Paget’s disease of the skin. A unifying concept of histogenesis. Cancer. 1982;50:2203–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19821115)50:10<2203::aid-cncr2820501037>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller LR, McCunniff AJ, Randall ME. An immunohistochemical study of perianal Paget’s disease. Possible origins and clinical implications. Cancer. 1992;69:2166–71. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920415)69:8<2166::aid-cncr2820690825>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Allan SJ, McLaren K, Aldridge RD. Paget’s disease of the scrotum: A case exhibiting positive prostate-specific antigen staining and associated prostatic adenocarcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 1998;138:689–91. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.1998.02187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marchesa P, Fazio VW, Oliart S, et al. Long-term outcome of patients with perianal Paget’s disease. Ann Surg Oncol. 1997;4:475–80. doi: 10.1007/BF02303671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fetherson WC, Friedrich EG. The origin and significance of vulvar Paget’s disease. Obstet Gynecol. 1972;39:735–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Watanabe S, Ohnishi T, Takahashi H, et al. A comparative study of cytokeratin expression in Paget’s cells located at various sites. Cancer. 1993;72:3323–30. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19931201)72:11<3323::aid-cncr2820721131>3.0.co;2-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Koseki S, Mitsuhashi Y, Yoshikawa K, et al. A case of triple extramammary Paget’s disease. J Dermatol. 1997;24:535–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.1997.tb02835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Begin LR, Deschenes J, Mitmaker B. Pagetoid carcinomatous involvement of the penile urethra in association with high grade transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1991;115:632–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones RR, Spaull J, Gusterson B. The histogenesis of mammary and extramammary Paget’s disease. Histopathology. 1989;14:409–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1989.tb02169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Battles OE, Page DL, Johnson JE. Cytokeratins, CEA, and mucin histochemistry in the diagnosis and characterization of Extramammary Paget’s Disease. Am J Clin Pathol. 1997;108:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glasgow BJ, Wen DR, Al-Jitawi S, et al. Antibody to S-100 protein aids the sepraration of pagetoid melanoma from mammary and extramammary Pagets disease. J Cutan Path. 1987;14:223–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.1987.tb01337.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregori CA, Smith CI, Breen JL. Extramammary Paget’s disease. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1978;21:1107–15. doi: 10.1097/00003081-197821040-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jongen J, Reh M, Bock JU, Rabenhorst G. Perianal precancerous conditions (Bowen disease, Paget disease, Carcinoma in situ, Buschke-Lowenstein tumor) Kongressbd Dtsch ges Chir Kongr. 2001;118:79–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chanda JJ. Extramammary Paget’s disease prognosis and relationship to internal malignancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1985;13:1009–14. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(85)70254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fanning J, Lambert HC, Hale TM, et al. Paget’s disease of the vulva: prevalence of associated vulvar adenocarcinoma, invasive Paget’s disease and recurrence after surgical excision. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:24–7. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70143-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coldiron BM, Goldsmith BA, Robinson JK. Surgical treatment of extramammry Paget’s disease. A report of six cases and a reexamination of Mohs micrographic surgery compared with conventional surgical excision. Cancer. 1991;67:933–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910215)67:4<933::aid-cncr2820670413>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gunn RA, Gallager HS. Vulvar Paget’s disease: A topographic study. Cancer. 1980;46:590–4. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19800801)46:3<590::aid-cncr2820460327>3.0.co;2-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Besa P, Rich TA, Delclos L, et al. Extramammry Paget’s disease of the perineal skin: Role of radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;24:73–8. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)91024-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burrows NP, Jones DH, Hudson PM, et al. Treatment of extramammary Paget’s disease by radiotherapy. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132:970–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb16957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bewley AP, Bracka A, Staughton RC, et al. Extramammary Paget’s disease of the scrotum: Treatment with topical 5-fluorouracil and plastic surgery. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:445–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1994.tb08535.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Watring WG, Roberts JA, Lagasse LD, et al. Treatment of recurrent Paget’s disease of the vulva with topical bleomycin. Cancer. 1978;41:10–1. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197801)41:1<10::aid-cncr2820410103>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Del Castillo LF, Garcia C, Schoendorff C, et al. Spontaneous apparent clinical resolution with histologic persistence of a case of extramammary Paget’s disease: response to topical 5-fluorouracil. Cutis. 2000;65:331–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Voigt H, Bassermann R, Nathrath W. Cytoreductive combination chemotherapy for regionally advanced unresectable extramammary Paget carcinoma. Cancer. 1992;70:704–8. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920801)70:3<704::aid-cncr2820700327>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Misas JE, Cold CJ, Hall FW. Vulvar Paget disease: Fluorescein-aided visualization of margins. Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:156–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lundquist K, Kohler S, Rouse RV. Intraepidermal cytokeratin 7 expression is not restricted to Paget cells but is also seen in Toker cells and Merkel cells. Am J Surg Path. 1999;23:212–9. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199902000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]