Abstract

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotypes have distinct genetic and geographic diversity and may be associated with specific clinical characteristics, progression, severity of disease and antiviral response. Herein, we provide an updated overview of the endemicity of HBV genotypes H and G in Mexico. HBV genotype H is predominant among the Mexican population, but not in Central America. Its geographic distribution is related to a typical endemicity among the Mexicans which is characterized by a low hepatitis B surface antigen seroprevalence, apparently due to a rapid resolution of the infection, low viral loads and a high prevalence of occult B infection. During chronic infections, genotype H is detected in mixtures with other HBV genotypes and associated with other co-morbidities, such as obesity, alcoholism and co-infection with hepatitis C virus or human immunodeficiency virus. Hepatocellular carcinoma prevalence is low. Thus, antiviral therapy may differ significantly from the standard guidelines established worldwide. The high prevalence of HBV genotype G in the Americas, especially among the Mexican population, raises new questions regarding its geographic origin that will require further investigation.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus genotypes, Hepatitis B virus genotype H, Hepatitis B virus genotype G, Molecular epidemiology, Mexico, Antiviral therapy, Severity of liver disease, Clinical outcome

Core tip: Molecular, clinical, geographical and ethnicity evidence are characteristics that define any hepatitis B virus (HBV) genotype. All of these features are there for HBV genotype H, which is most predominant in Mexico, but not in Central America. Likewise, HBV genotype G has unique molecular characteristics and a similar route of transmission among those infected with this viral genotype, but it lacks a geographic origin. To date, despite the high prevalence of HBV genotype G cases from the Americas, especially among Mexicans, the limited number of complete sequences hinders further investigation to establish a hypothesis of an Amerindian origin.

INTRODUCTION

Definition of hepatitis B virus genotypes and their association with human liver disease

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and humans share a close relationship through the process of evolution and migration[1,2]. Numerous studies have demonstrated that most HBV genotypes are associated with a host population and geographical area of the world, while others tend to have a worldwide distribution, or still remain unknown[3,4].

In 1988, Okamoto et al[3] proposed the first genetic classification for HBV strains, defining a genotype as a viral sequence with an intertypic nucleotide divergence of more than 8% based on the entire genome. Later, a 4.2% nucleotide divergence using the S gene sequence was proposed by Norder et al[5]. Throughout their discovery, each new genotype was defined by the same criterion and designated with letters in an alphabetical order, from A to J. However, given the wide diversity of HBV genomes worldwide, several authors have proposed over the years that precise criteria be fulfilled in order to identify and describe a specific genotype/subgenotype[6-9]. Recently, Kurbanov et al[10] have endorsed and updated these recommendations which, in summary, are the following: use of whole genome sequences, divergence of ≥ 7.5% (> 4% to < 7.5% in the case of a subgenotype), strong independent clustering on molecular evolutionary analysis, avoidance of recombinants, as well as substantial epidemiological, virological and clinical evidence.

Regarding these latter points, in 2002, Chu et al[11] raised key questions about the association of HBV genotypes with clinical practice: (1) “What is the predominant HBV genotype in each country or geographic region” (2) “Is the geographic distribution of HBV genotypes related to the endemicity of HBV infection” (3) “Is there a correlation between HBV genotype and HBV replication activity of liver disease, clinical outcome and treatment response” and (4) “Is there a correlation between HBV genotype and risk of progression to chronic infection”

Accordingly, the geographic distribution of HBV genotypes in regard to their regional host population and endemicity has been widely considered. In general, HBV genotypes B and C are associated with the populations of the Asian countries[3] while genotypes A and D are prevalent among European countries and the United States[3]; genotypes E and F are confined to countries of the African continent[12] and the Americas[12] (Central and South America), respectively. HBV genotype G (HBV/G) was originally reported in France[13] but has a global distribution, and HBV genotype H (HBV/H) was first revealed in Central America[14]. HBV genotypes I and J have been reported in dispersed regions of Asia and Japan, respectively[15,16]. Likewise, the genetic diversity, disease progression and response to antiviral therapy[17-20] of the European and Asian genotypes (A-D)[21-23] have received greater attention than those that are typically prevalent in the western hemisphere (E-H)[24-27], while evidence about genotypes I and J is insufficient to respond to such arguments[10,28].

Milestones in the discovery of HBV genotypes G and H worldwide and in Mexico

HBV/G and HBV/H were revealed almost at the same time. Both discoveries represent the culminating results of investigations carried out in the 1990s by many different laboratories worldwide. HBV/G was first described as an HBV variant[29,30] and formally reported by Stuyver et al[13] in 2000. In our laboratory, HBV/G was detected in 2000, but not reported until 2002 by Sánchez et al[31]. Further on, research studies focused on the development of molecular diagnostic methods[32] and the relationship between clinical and virological characteristics in comparison with the other known genotypes[26,33]. However, unlike the rest of them, the geographic origin of HBV/G is still unknown[34].

As for HBV/H, Dr. Norder from Sweden and two other laboratories, Dr. Misokami from Japan and Dr. Panduro in Mexico, were studying the genetic variability of HBV that resulted in the identification of HBV/H in the last decade of the preceding century. However, the first HBV/H strains from Mexico were classified as HVB genotype F (HBV/F) by Sánchez et al[31] since complete sequences of genotype H were not available for comparison. Later, after discussing our findings with Dr. Norder in Mexico, two strains from Nicaragua and one from the United States were made known as the new genotype H[14]. Since then, HBV/H has often been referred to as from Central America, because of the two original Nicaraguan strains. Further discussion regarding the validity of genotype H was provided by Kato et al[35], given that seven HBV isolates (doubtfully H) differed from a number of selected HBV/F strains by a genetic divergence of 7.3%-9.5%, thus proposing a new subtype (F2) of HBV/F.

Overall, in the last ten years, the knowledge on HBV/H regarding the relationship between virological-clinical characteristics and its geographical and host population prevalence has increased significantly, allowing us to have a better understanding of HBV-infected patients. Herein, we provide an updated overview of such evidence concerning the endemicity of HBV infection based on genotypes H and G in Mexico.

HBV GENOTYPE H

Molecular characteristics of HBV genotype H

In the study by Arauz-Ruiz et al[14], the three original samples (1853Nic, 2928Nic, LAS2523) designated as HBV/H diverged from selected genotype F strains by 7.2%-10.2%. In the polymerase region, the three strains had 16 unique conserved amino acid residues not present in genotype F strains. Additionally, HBV/H also differs from them by two distinct substitutions in the surface antigen protein, at Val44 and Pro45, as well as at Ile57, Thr140, Phe158 and Ala224[4]. Furthermore, by “TreeOrder Scan” analysis, genotype H strains show evidence of recombination with genotype F within the small S gene (nucleotide 350-500)[1].

As mentioned before, the limited number of sequences available at that time made it difficult to distinguish HBV/H as an independent genotype, due to its close phylogenetic relatedness with HBV/F[14,35]. Nevertheless, the amount of HBV/H sequences reported in GenBank has increased; hence pair-wise analysis of complete sequences of HBV/F compared against the latest Mexican HBV/H strains result in a genetic distance of at least 0.08 (data not shown). Thus, the initial differences reported by the authors could have been related to the fact that the earlier isolates came from subjects with residence outside of Mexico[14,35].

Additionally, the estimated maximum likelihood phylogeny of HBV/H and HBV/F genomes exhibits a distinct genetic divergence from a common ancestor while HBV/H sequences tend to cluster into multiple and nested clades[36]. Further phylogeographic studies based on coalescent models are necessary to provide fresh information regarding these evolutionary characteristics, and integrate them to the timeline of migrations of the prehispanic people from ancient Mexico towards South America.

Molecular epidemiology of HBV genotype H in Mexico

During the last 10 years, the geographic origin of HBV/H was referred to as from Central America. Today, it is clearly evident that most HBV/H sequences deposited in GenBank are from Mexico, while those isolated worldwide come from individuals reporting sexual relationships with people from the Americas, and no further H strains have been reported from Central America[36].

Epidemiological studies using only hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) determinations have shown a steady prevalence rate of 0.3% since 1976 to date, ranking Mexico as a region of low endemicity[37]. However, by anti-HBc marker and molecular diagnosis of HBV genomes, high endemic areas of HBV infection have been detected in the native population[37-39], similar to the indigenous populations of the Central and South American countries[40].

It has been estimated that nearly 15 million Mexican adults have been infected by HBV during their lifetime, since the anti-HBc prevalence increases with age[41,42]. Additionally, estimates suggest that at least another 5 million native people could be at risk of acquiring infection[41]. HBV/H infection is acquired primarily during adulthood by horizontal transmission, through sexual relationships and contact with contaminated body fluids, which could explain why the majority of infected patients do not develop chronic liver disease[41].

HBV/H is the predominant genotype in asymptomatic infected patients living in high endemic areas[36,38], as well as in patients with acute and chronic liver disease[43,44]. Indeed, HBV/H is prevalent in more than 90% of the cases, followed by HBV/A, HBV/D and HBV/G, whereas other known HBV genotypes are rare[36]. Furthermore, the predominance of HBV/H in Mexico is historically related to the migrations of the prehispanic people, the settlement of the Aztecs in Mesoamerica before the Spanish conquest and the successive admixture of the population; hence, it is the predominant genotype detected in both Mexican native (Amerindian) and mestizo populations[36,38].

Clinical presentation of HBV/H infected patients

HBV/H infected patients usually are asymptomatic without clinical or laboratory manifestations of liver disease[38,43]; thus, the existence of liver damage is modest or undetectable, whereas occult B infection (OBI) is a common manifestation[38,45]. This situation may be attributed to a rapid resolution of the disease, associated with the genetic characteristics of either the virus or the host[46].

HBV/H is often detected in patients with acute liver damage. This clinical symptom is observed in male patients, such as men who have sex with men, mainly during the acute phase, and then with viral clearance or OBI after acute infection and flares during immunosuppressive conditions[46]. In chronic patients, HBV/H is predominant also; however, OBI is common so that the association of the HBV/H with the progression and severity of liver disease is masked by the presence of other co-morbidities, such as alcoholism, obesity and co-infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)[36]. HBV/H-infected patients tend to have low viral loads, usually < 4000 UI/L, that are easily detected as they increase, up to 100000 UI/L or above when patients are infected with mixtures of HBV genotypes[36].

Lastly, the low prevalence of HBV infection among the Mexican population is associated with a low prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) from 1953 to date[47-49]. This is contrary to what occurs in the Asian countries, where acute and chronic HBV infection with genotypes B and C and HCC are highly prevalent. Thus, the predominance of HBV/H among the Mexican population is associated with low endemicity, low viral load, minimum cases of acute and chronic liver diseases due to HBV infection and a low prevalence of HCC.

This matter raises a word of caution regarding the strategy for antiviral therapy in Mexico since the main cause of liver disease may be attributed to co-morbidities, such as HCV or HIV infection, alcoholism or obesity, but not to HBV infection exclusively. Therefore, antiviral therapy for HBV/H-infected patients should be given with precaution until the usefulness of the conventional antivirals is fully demonstrated for this genotype, considering that the international guidelines for the treatment of chronic B infection have been designed for populations of other geographic regions that have different HBV genotypes, endemicity and progression of liver disease.

HBV GENOTYPE G

Molecular characteristics of HBV genotype G

The HBV/G genome has some unique characteristics. It contains a 36-nt/12 amino acid insertion with pleiotropic effects on core protein expression, genome replication and virion secretion, not found in any other HBV genotype[50]. It also has two stop codons in the preC region at position 2 and 28, which prohibits the translation of the hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg)-precursor; thus, patients who are mono-infected with HBV/G are negative for HBeAg[51]. Other molecular characteristics include two deletions, one at the carboxyl terminal region of HBcAg and another in the preS1 region[51].

At the nucleotide level, the majority of the complete genome sequences of HBV/G strains share a remarkable sequence conservation of more than 99%[52]. Furthermore, there is a high nucleotide similarity within the S gene sequence (94.6%-97.5%), considered as evidence of recombination with genotype A (HBV/A) in the small S fragment (nucleotide 250-350)[1] and a 30 base pair fragment in the preS region that is almost identical to genotype E[34].

Molecular epidemiology of HBV/G in Mexico

Worldwide, a significant number of HBV/G strains have been detected in men who have sex with men[13,26,29,30,52-54], suggesting that sexual genital-anal contact may play a significant role in the transmission of HBV infection[55]. However, parenteral transmission has been reported, mainly as mono-infection, such as in blood donors[56-58] and hemodialysis patients[59].

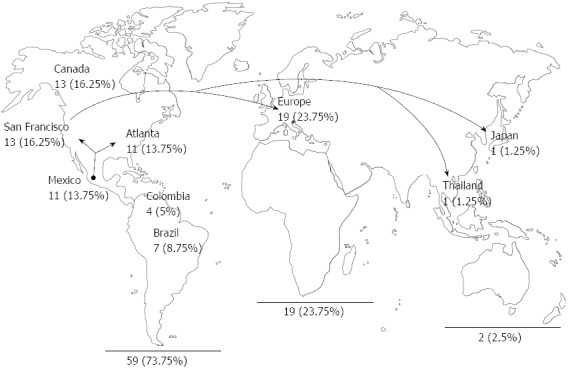

In the past years, several publications continue to report that little is known about the geographical origin of HBV/G, and yet it is considered ubiquitous. Such statements have arisen due to earlier HBV/G cases reported from France[13], Germany[54] and the cities of San Francisco, CA[26,29,52] and Atlanta, Georgia[13] in the United States. However, despite the limitations of using RFLPs or strip molecular methods for the detection of HBV/G, instead of complete genome sequences[10], most of the cases of this genotype have been reported from the Americas (73.5%), including Mexico[31,38,46,55,60,61] and to a lesser degree from Europe[30,50,56,62-65] (23.75%) and other regions of the world (2.5%)[66-68] (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Geographic distribution of the worldwide epidemiology of the hepatitis B virus genotype G isolates. Fifty-nine genome sequences out of a total of 80 have been reported from the Americas (73.75%), whereas 23.75% are from Europe and 2.5% from Asia. The high prevalence of hepatitis B virus genotype G in America may be related to a common source of infection and transmission route.

As mentioned before, the geographic origin of HBV/G is still unknown, due to its low global prevalence combined with the lack of epidemiological and clinical data. The genomic characteristics of this genotype are puzzling. On one hand, HBV/G complete sequences share such a close similarity that a specific molecular epidemiological route of transmission among the international cases or a simple evolutionary history cannot be elaborated. On the other hand, the similarity of certain regions of the HBV/G genome with genotypes A[1] and E[34] suggest co-evolutionary processes among themselves[10]. These features have created considerable difficulties to pinpoint a distinct geographic origin for HBV/G.

A hypothesis on a plausible African geographic origin of HBV/G was proposed by Lindh[34] in 2005, based on its similarity with HBV/E which is prevalent in Africa and that the worldwide spread of HIV infection from Africa may have been the cause of the dispersion of HBV/G. Unfortunately, HBV/G African sequences have not been deposited in GenBank nor have G/E recombinants been associated with a host population to date. Furthermore, based on the low genetic diversity of HBV/E (1.67%) and its short evolutionary history[69], it has been suggested that it was introduced into the African population after the Atlantic slave trade[69-71]. This is consistent with the fact that HBV/E is virtually absent in the Americas, despite the significant number of African slaves introduced into the United States and Latin America (including Mexico), both regions having a high presence of black population, the former of Afro origin and the latter mixed descendents of a large black population forced into slavery. Thus, the worldwide spread of HBV/G appears to have not co-dispersed HBV/E, since G/E recombination or G-E co-infection is absent among the admixture populations. Interestingly, the similarity of the 150 base pair fragment between HBV/A and HBV/G could be related to the most common dual HBV G/A infection reported in the United States[26,52], Canadian[53] and European cases[56]. Given that HBV/A is common in Europe, it may be speculated that genotype G could have reached the Americas by way of the Caucasian people. However, despite the fact that HBV/A is a minor strain in Mexico[36], HBV G/H co-infection is more frequent than G/A[55]. Thus, G/H co-infection may be related to the plausibility that genotype G is endemic to Mexico, as well as genotype H. Furthermore, HBV/G has been detected in patients with chronic liver disease; pathogenesis of liver fibrosis has been documented in in vitro experiments[60,72] and corroborated in patients with co-infection with other HBV genotypes.

The relationship of HBV/G sequences with the Mexican population is based on the following observations: (1) the high prevalence of HBV/G sequences in the American continent (73.75%) (Figure 1); (2) 16 HBV/G cases were detected among 77 HIV/HBV co-infected individuals (21%)[61]; (3) 5 HBV/G cases out of 49 high risk individuals (10.2%)[27]; and (4) HBV/G sequences have been identified in an ongoing study cohort of young children with HBV infection in our laboratory. These findings lead us to ask ourselves: “Is HBV/G endemic to the Americas, including Mexico, Colombia, and Brazil or was it introduced into the continent” The evidence that could support an Amerindian hypothesis requires that sequences from native and mestizo populations be analyzed. To date, 11 sequences from Mexico[31,38,55,60], 7 from Brazil[73-75] and 4 from Colombia[58] have been retrieved from mestizo populations, except for one Mexican case belonging to a native from the Huichol community[38]. The presence of HBV/G in this community could be explained by the fact that native individuals engage in multi-partner sexual relationships and male-to-male sexual activity[38,76,77]. However, further phylogeographic studies are required in order to determine if these findings may be related to the transmission of HBV/G infection among distinct Amerindian communities before the global dissemination of blood-borne infectious diseases.

Nevertheless, Mexican and United States HBV/G strains share a close genetic homology[55]. This is consistent with the fluent migration events that have occurred for centuries across the United States-Mexican border, especially from the western states of Jalisco, Michoacan and Guanajuato, towards the large United States Hispanic communities, such as in Los Angeles, San Francisco and Atlanta, among others[78] (Figure 1). However, despite this feasible epidemiological association, further evidence is required to verify if the transmission of HBV/G infection may have occurred among same-sex couples/transgender individuals traveling to and from Mexico and the United States[79,80].

CONCLUSION

The predominance of HBV genotype H among the Mexican population is associated with a definite geographic region and historical context. The endemicity of HBV infection in Mexico manifests with a low HBsAg seroprevalence, due to a rapid response to the infection, low viral loads and a high prevalence of occult B infection. During chronic infections, HBV infection may be undetectable and associated with co-morbidities, such as obesity, alcoholism and co-infection with HCV or HIV. These manifestations correlate with the low prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma. Based on these features, antiviral therapy may differ significantly from the international guidelines that have been established for patients within the regions of high endemicity. As for the high prevalence of HBV/G cases reported in Mexico, more detailed phylogenetic analysis of other HBV/G complete sequences will be required in order to elucidate its geographic origin.

Footnotes

Supported by National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT-FONDO SECTORIAL, Mexico), Grant No. Salud-2010-1-139085, to Roman S; and Jalisco State Council of Science and Technology (COECYTJAL-Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara, Jalisco, Mexico), Grant No. 2009-1-06-2009-431, to Panduro A

P- Reviewers Chen GY, Murakami Y S- Editor Zhai HH L- Editor Logan S E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Simmonds P, Midgley S. Recombination in the genesis and evolution of hepatitis B virus genotypes. J Virol. 2005;79:15467–15476. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15467-15476.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kay A, Zoulim F. Hepatitis B virus genetic variability and evolution. Virus Res. 2007;127:164–176. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Okamoto H, Tsuda F, Sakugawa H, Sastrosoewignjo RI, Imai M, Miyakawa Y, Mayumi M. Typing hepatitis B virus by homology in nucleotide sequence: comparison of surface antigen subtypes. J Gen Virol. 1988;69(Pt 10):2575–2583. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-69-10-2575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Norder H, Couroucé AM, Coursaget P, Echevarria JM, Lee SD, Mushahwar IK, Robertson BH, Locarnini S, Magnius LO. Genetic diversity of hepatitis B virus strains derived worldwide: genotypes, subgenotypes, and HBsAg subtypes. Intervirology. 2004;47:289–309. doi: 10.1159/000080872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Norder H, Hammas B, Löfdahl S, Couroucé AM, Magnius LO. Comparison of the amino acid sequences of nine different serotypes of hepatitis B surface antigen and genomic classification of the corresponding hepatitis B virus strains. J Gen Virol. 1992;73(Pt 5):1201–1208. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-5-1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyakawa Y, Mizokami M. Classifying hepatitis B virus genotypes. Intervirology. 2003;46:329–338. doi: 10.1159/000074988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramvis A, Kew M, François G. Hepatitis B virus genotypes. Vaccine. 2005;23:2409–2423. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2004.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schaefer S. Hepatitis B virus taxonomy and hepatitis B virus genotypes. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:14–21. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schaefer S, Magnius L, Norder H. Under construction: classification of hepatitis B virus genotypes and subgenotypes. Intervirology. 2009;52:323–325. doi: 10.1159/000242353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kurbanov F, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M. Geographical and genetic diversity of the human hepatitis B virus. Hepatol Res. 2010;40:14–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2009.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chu CJ, Lok AS. Clinical significance of hepatitis B virus genotypes. Hepatology. 2002;35:1274–1276. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norder H, Couroucé AM, Magnius LO. Complete genomes, phylogenetic relatedness, and structural proteins of six strains of the hepatitis B virus, four of which represent two new genotypes. Virology. 1994;198:489–503. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stuyver L, De Gendt S, Van Geyt C, Zoulim F, Fried M, Schinazi RF, Rossau R. A new genotype of hepatitis B virus: complete genome and phylogenetic relatedness. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:67–74. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-1-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arauz-Ruiz P, Norder H, Robertson BH, Magnius LO. Genotype H: a new Amerindian genotype of hepatitis B virus revealed in Central America. J Gen Virol. 2002;83:2059–2073. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-83-8-2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu H, Yuan Q, Ge SX, Wang HY, Zhang YL, Chen QR, Zhang J, Chen PJ, Xia NS. Molecular and phylogenetic analyses suggest an additional hepatitis B virus genotype “I”. PLoS One. 2010;5:e9297. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatematsu K, Tanaka Y, Kurbanov F, Sugauchi F, Mano S, Maeshiro T, Nakayoshi T, Wakuta M, Miyakawa Y, Mizokami M. A genetic variant of hepatitis B virus divergent from known human and ape genotypes isolated from a Japanese patient and provisionally assigned to new genotype J. J Virol. 2009;83:10538–10547. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00462-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kramvis A, Kew MC. Relationship of genotypes of hepatitis B virus to mutations, disease progression and response to antiviral therapy. J Viral Hepat. 2005;12:456–464. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2005.00624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tanaka Y, Mizokami M. Genetic diversity of hepatitis B virus as an important factor associated with differences in clinical outcomes. J Infect Dis. 2007;195:1–4. doi: 10.1086/509898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tseng TC, Kao JH. HBV genotype and clinical outcome of chronic hepatitis B: facts and puzzles. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:1272–1273; author reply 1273. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pujol FH, Navas MC, Hainaut P, Chemin I. Worldwide genetic diversity of HBV genotypes and risk of hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett. 2009;286:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erhardt A, Blondin D, Hauck K, Sagir A, Kohnle T, Heintges T, Häussinger D. Response to interferon alfa is hepatitis B virus genotype dependent: genotype A is more sensitive to interferon than genotype D. Gut. 2005;54:1009–1013. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.060327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu WC, Phiet PH, Chiang TY, Sun KT, Hung KH, Young KC, Wu IC, Cheng PN, Chang TT. Five subgenotypes of hepatitis B virus genotype B with distinct geographic and virological characteristics. Virus Res. 2007;129:212–223. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2007.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jardi R, Rodriguez-Frias F, Schaper M, Giggi E, Tabernero D, Homs M, Esteban R, Buti M. Analysis of hepatitis B genotype changes in chronic hepatitis B infection: Influence of antiviral therapy. J Hepatol. 2008;49:695–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2008.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lacombe K, Massari V, Girard PM, Serfaty L, Gozlan J, Pialoux G, Mialhes P, Molina JM, Lascoux-Combe C, Wendum D, et al. Major role of hepatitis B genotypes in liver fibrosis during coinfection with HIV. AIDS. 2006;20:419–427. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000200537.86984.0e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erhardt A, Göbel T, Ludwig A, Lau GK, Marcellin P, van Bömmel F, Heinzel-Pleines U, Adams O, Häussinger D. Response to antiviral treatment in patients infected with hepatitis B virus genotypes E-H. J Med Virol. 2009;81:1716–1720. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kato H, Gish RG, Bzowej N, Newsom M, Sugauchi F, Tanaka Y, Kato T, Orito E, Usuda S, Ueda R, et al. Eight genotypes (A-H) of hepatitis B virus infecting patients from San Francisco and their demographic, clinical, and virological characteristics. J Med Virol. 2004;73:516–521. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alvarado-Esquivel C, de la Ascensión Carrera-Gracia M, Conde-González CJ, Juárez-Figueroa L, Ruiz-Maya L, Aguilar-Benavides S, Torres-Valenzuela A, Sablon E. Genotypic resistance to lamivudine among hepatitis B virus isolates in Mexico. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;57:221–223. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kurbanov F, Tanaka Y, Kramvis A, Simmonds P, Mizokami M. When should “I” consider a new hepatitis B virus genotype. J Virol. 2008;82:8241–8242. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00793-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bhat RA, Ulrich PP, Vyas GN. Molecular characterization of a new variant of hepatitis B virus in a persistently infected homosexual man. Hepatology. 1990;11:271–276. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tran A, Kremsdorf D, Capel F, Housset C, Dauguet C, Petit MA, Brechot C. Emergence of and takeover by hepatitis B virus (HBV) with rearrangements in the pre-S/S and pre-C/C genes during chronic HBV infection. J Virol. 1991;65:3566–3574. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.7.3566-3574.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sánchez LV, Maldonado M, Bastidas-Ramírez BE, Norder H, Panduro A. Genotypes and S-gene variability of Mexican hepatitis B virus strains. J Med Virol. 2002;68:24–32. doi: 10.1002/jmv.10166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kato H, Orito E, Sugauchi F, Ueda R, Gish RG, Usuda S, Miyakawa Y, Mizokami M. Determination of hepatitis B virus genotype G by polymerase chain reaction with hemi-nested primers. J Virol Methods. 2001;98:153–159. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(01)00374-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kato H, Orito E, Gish RG, Bzowej N, Newsom M, Sugauchi F, Suzuki S, Ueda R, Miyakawa Y, Mizokami M. Hepatitis B e antigen in sera from individuals infected with hepatitis B virus of genotype G. Hepatology. 2002;35:922–929. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.32096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lindh M. HBV genotype G-an odd genotype of unknown origin. J Clin Virol. 2005;34:315–316. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kato H, Fujiwara K, Gish RG, Sakugawa H, Yoshizawa H, Sugauchi F, Orito E, Ueda R, Tanaka Y, Kato T, et al. Classifying genotype F of hepatitis B virus into F1 and F2 subtypes. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:6295–6304. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i40.6295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Panduro A, Maldonado-Gonzalez M, Fierro NA, Roman S. Distribution of HBV genotypes F and H in Mexico and Central America. Antivir Ther. 2013;18:475–484. doi: 10.3851/IMP2605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roman S, Panduro A, Aguilar-Gutierrez Y, Maldonado M, Vazquez-Vandyck M, Martinez-Lopez E, Ruiz-Madrigal B, Hernandez-Nazara Z. A low steady HBsAg seroprevalence is associated with a low incidence of HBV-related liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma in Mexico: a systematic review. Hepatol Int. 2009;3:343–355. doi: 10.1007/s12072-008-9115-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Roman S, Tanaka Y, Khan A, Kurbanov F, Kato H, Mizokami M, Panduro A. Occult hepatitis B in the genotype H-infected Nahuas and Huichol native Mexican population. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1527–1536. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alvarez-Muñoz T, Bustamante-Calvillo E, Martínez-García C, Moreno-Altamirando L, Guiscafre-Gallardo H, Guiscafre JP, Muñoz O. Seroepidemiology of the hepatitis B and delta in the southeast of Chiapas, Mexico. Arch Invest Med (Mex) 1989;20:189–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cardona NE, Loureiro CL, Garzaro DJ, Duarte MC, García DM, Pacheco MC, Chemin I, Pujol FH. Unusual presentation of hepatitis B serological markers in an Amerindian community of Venezuela with a majority of occult cases. Virol J. 2011;8:527. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-8-527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Panduro A, Escobedo Meléndez G, Fierro NA, Ruiz Madrigal B, Zepeda-Carrillo EA, Román S. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 2011;53 Suppl 1:S37–S45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valdespino JL, Conde-Gonzalez CJ, Olaiz-Fernandez G, Palma O, Sepulveda J. Prevalence of hepatitis B infection and carrier status among adults in Mexico. Salud Publica Mex. 2007;49 Suppl 3:S404–S411. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruiz-Tachiquín ME, Valdez-Salazar HA, Juárez-Barreto V, Dehesa-Violante M, Torres J, Muñoz-Hernández O, Alvarez-Muñoz MT. Molecular analysis of hepatitis B virus “a” determinant in asymptomatic and symptomatic Mexican carriers. Virol J. 2007;4:6. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-4-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alvarado-Esquivel C, Sablon E, Conde-González CJ, Juárez-Figueroa L, Ruiz-Maya L, Aguilar-Benavides S. Molecular analysis of hepatitis B virus isolates in Mexico: predominant circulation of hepatitis B virus genotype H. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:6540–6545. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i40.6540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.García-Montalvo BM, Ventura-Zapata LP. Molecular and serological characterization of occult hepatitis B infection in blood donors from Mexico. Ann Hepatol. 2011;10:133–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fierro NA, Roman S, Realpe M, Hernandez-Nazara Z, Zepeda-Carrillo EA, Panduro A. Multiple cytokine expression profiles reveal immune-based differences in occult hepatitis B genotype H-infected Mexican Nahua patients. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2011;106:1007–1013. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762011000800018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vivas-Arceo C, Bastidas-Ramıirez BE, Panduro A. Hepatocellular carcinoma is rarely present in Western Mexico. Hep Res. 1999;16:26–35. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pujol F, Roman S, Panduro A, Navas MC, Lampe E. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Latin America. In: Chemin I, editor. Hepatocellular carcinoma: a global challenge. New York: Nova Science Publishers; 2012. pp. 55–68. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Roman S, Fierro NA, Moreno-Luna L, Panduro A. Hepatitis B virus genotype H and environmental factors associated to the low prevalence of hepatocellular carcinoma in Mexico. J Cancer Ther. 2013;2A:367–376. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li K, Zoulim F, Pichoud C, Kwei K, Villet S, Wands J, Li J, Tong S. Critical role of the 36-nucleotide insertion in hepatitis B virus genotype G in core protein expression, genome replication, and virion secretion. J Virol. 2007;81:9202–9215. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00390-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carman WF, Jacyna MR, Hadziyannis S, Karayiannis P, McGarvey MJ, Makris A, Thomas HC. Mutation preventing formation of hepatitis B e antigen in patients with chronic hepatitis B infection. Lancet. 1989;2:588–591. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90713-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kato H, Orito E, Gish RG, Sugauchi F, Suzuki S, Ueda R, Miyakawa Y, Mizokami M. Characteristics of hepatitis B virus isolates of genotype G and their phylogenetic differences from the other six genotypes (A through F) J Virol. 2002;76:6131–6137. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.12.6131-6137.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Osiowy C, Gordon D, Borlang J, Giles E, Villeneuve JP. Hepatitis B virus genotype G epidemiology and co-infection with genotype A in Canada. J Gen Virol. 2008;89:3009–3015. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.2008/005124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vieth S, Manegold C, Drosten C, Nippraschk T, Günther S. Sequence and phylogenetic analysis of hepatitis B virus genotype G isolated in Germany. Virus Genes. 2002;24:153–156. doi: 10.1023/a:1014572600432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sánchez LV, Tanaka Y, Maldonado M, Mizokami M, Panduro A. Difference of hepatitis B virus genotype distribution in two groups of mexican patients with different risk factors. High prevalence of genotype H and G. Intervirology. 2007;50:9–15. doi: 10.1159/000096307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chudy M, Schmidt M, Czudai V, Scheiblauer H, Nick S, Mosebach M, Hourfar MK, Seifried E, Roth WK, Grünelt E, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype G monoinfection and its transmission by blood components. Hepatology. 2006;44:99–107. doi: 10.1002/hep.21220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zaaijer HL, Boot HJ, van Swieten P, Koppelman MH, Cuypers HT. HBsAg-negative mono-infection with hepatitis B virus genotype G. J Viral Hepat. 2011;18:815–819. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2010.01397.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alvarado Mora MV, Romano CM, Gomes-Gouvêa MS, Gutierrez MF, Botelho L, Carrilho FJ, Pinho JR. Molecular characterization of the Hepatitis B virus genotypes in Colombia: a Bayesian inference on the genotype F. Infect Genet Evol. 2011;11:103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2010.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sayan M, Dogan C. Hepatitis B virus genotype G infection in a Turkish patient undergoing hemodialysis therapy. Hepat Mon. 2012;12:118–121. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tanaka Y, Sanchez LV, Sugiyama M, Sakamoto T, Kurbanov F, Tatematsu K, Roman S, Takahashi S, Shirai T, Panduro A, et al. Characteristics of hepatitis B virus genotype G coinfected with genotype H in chimeric mice carrying human hepatocytes. Virology. 2008;376:408–415. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mata Marín JA, Arroyo Anduiza CI, Calderón GM, Cazares Rodríguez S, Fuentes Allen JL, Arias Flores R, Gaytán Martínez J. Prevalence and resistance pattern of genotype G and H in chronic hepatitis B and HIV co-infected patients in Mexico. Ann Hepatol. 2012;11:47–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Trimoulet P, Boutonnet M, Winnock M, Faure M, Loko MA, De Lédinghen V, Bernard PH, Castéra L, Foucher J, Dupon M, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotypes: a retrospective survey in Southwestern France, 1999-2004. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2007;31:1088–1094. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(07)78341-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.De Maddalena C, Giambelli C, Tanzi E, Colzani D, Schiavini M, Milazzo L, Bernini F, Ebranati E, Cargnel A, Bruno R, et al. High level of genetic heterogeneity in S and P genes of genotype D hepatitis B virus. Virology. 2007;365:113–124. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ramos B, Núñez M, Martín-Carbonero L, Sheldon J, Rios P, Labarga P, Romero M, Barreiro P, García-Samaniego J, Soriano V. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and lamivudine resistance mutations in HIV/hepatitis B virus-coinfected patients. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2007;44:557–561. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3180314b46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toy M, Veldhuijzen IK, Mostert MC, de Man RA, Richardus JH. Transmission routes of hepatitis B virus infection in chronic hepatitis B patients in The Netherlands. J Med Virol. 2008;80:399–404. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Suwannakarn K, Tangkijvanich P, Theamboonlers A, Abe K, Poovorawan Y. A novel recombinant of Hepatitis B virus genotypes G and C isolated from a Thai patient with hepatocellular carcinoma. J Gen Virol. 2005;86:3027–3030. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shibayama T, Masuda G, Ajisawa A, Hiruma K, Tsuda F, Nishizawa T, Takahashi M, Okamoto H. Characterization of seven genotypes (A to E, G and H) of hepatitis B virus recovered from Japanese patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Med Virol. 2005;76:24–32. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kato H, Sugauchi F, Ozasa A, Kato T, Tanaka Y, Sakugawa H, Sata M, Hino K, Onji M, Okanoue T, et al. Hepatitis B virus genotype G is an extremely rare genotype in Japan. Hepatol Res. 2004;30:199–203. doi: 10.1016/j.hepres.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mulders MN, Venard V, Njayou M, Edorh AP, Bola Oyefolu AO, Kehinde MO, Muyembe Tamfum JJ, Nebie YK, Maiga I, Ammerlaan W, et al. Low genetic diversity despite hyperendemicity of hepatitis B virus genotype E throughout West Africa. J Infect Dis. 2004;190:400–408. doi: 10.1086/421502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Olinger CM, Venard V, Njayou M, Oyefolu AO, Maïga I, Kemp AJ, Omilabu SA, le Faou A, Muller CP. Phylogenetic analysis of the precore/core gene of hepatitis B virus genotypes E and A in West Africa: new subtypes, mixed infections and recombinations. J Gen Virol. 2006;87:1163–1173. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.81614-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Andernach IE, Nolte C, Pape JW, Muller CP. Slave trade and hepatitis B virus genotypes and subgenotypes in Haiti and Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1222–1228. doi: 10.3201/eid1508.081642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sugiyama M, Tanaka Y, Sakamoto T, Maruyama I, Shimada T, Takahashi S, Shirai T, Kato H, Nagao M, Miyakawa Y, et al. Early dynamics of hepatitis B virus in chimeric mice carrying human hepatocytes monoinfected or coinfected with genotype G. Hepatology. 2007;45:929–937. doi: 10.1002/hep.21584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bottecchia M, Souto FJ, O KM, Amendola M, Brandão CE, Niel C, Gomes SA. Hepatitis B virus genotypes and resistance mutations in patients under long term lamivudine therapy: characterization of genotype G in Brazil. BMC Microbiol. 2008;8:11. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-8-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Silva AC, Spina AM, Lemos MF, Oba IT, Guastini Cde F, Gomes-Gouvêa MS, Pinho JR, Mendes-Correa MC. Hepatitis B genotype G and high frequency of lamivudine-resistance mutations among human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis B virus co-infected patients in Brazil. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2010;105:770–778. doi: 10.1590/s0074-02762010000600007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mendes-Correa MC, Pinho JR, Locarnini S, Yuen L, Sitnik R, Santana RA, Gomes-Gouvêa MS, Leite OM, Martins LG, Silva MH, et al. High frequency of lamivudine resistance mutations in Brazilian patients co-infected with HIV and hepatitis B. J Med Virol. 2010;82:1481–1488. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Olivier-Durand G. Homosexualidad y prostitución entre los nahuas y otros pueblos del Posclasico. In: Escalante-Gonzalbo P, editor. Historia de la Vida Cotidiana en Mexico, Tomo 1, Mesoamérica y los Ámbitos de la Nueva España. Mexico: El Colegio de Mexico, Fondo de Cultura Económica; 2004. pp. 301–338. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sahagun B de. Historia General de las Cosas de la Nueva España, “Colección sepan cuantos". Mexico: Editorial Porrúa; 2006. pp. 1–1093. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Geografía. Censo de Población y Vivienda 2010. Available from: http://www.inegi.org.mx/sistemas/TabuladosBasicos/Default.aspxc =27303&s=est.

- 79.Lieb S, Fallon SJ, Friedman SR, Thompson DR, Gates GJ, Liberti TM, Malow RM. Statewide estimation of racial/ethnic populations of men who have sex with men in the U.S. Public Health Rep. 2011;126:60–72. doi: 10.1177/003335491112600110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Howe C, Zaraysky S, Lorentzen L. Transgender sex workers and sexual transmigration between Guadalajara and San Francisco. Latin American Perspectives. 2007;35:31–50. [Google Scholar]