Abstract

The activity of persistent Ca2+ sparklets, which are characterized by longer and more frequent channel open events than low-activity sparklets, contributes substantially to steady-state Ca2+ entry under physiological conditions. Here, we addressed two questions related to the regulation of Ca2+ sparklets by PKC-α and c-Src, both of which increase whole cell Cav1.2 current: 1) Does c-Src activation enhance persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity? 2) Does PKC-α activate c-Src to produce persistent Ca2+ sparklets? With the use of total internal reflection fluorescence microscopy, Ca2+ sparklets were recorded from voltage-clamped tsA-201 cells coexpressing wild-type (WT) or mutant Cav1.2c (the neuronal isoform of Cav1.2) constructs ± active or inactive PKC-α/c-Src. Cells expressing Cav1.2c exhibited both low-activity and persistent Ca2+ sparklets. Persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity was significantly reduced by acute application of the c-Src inhibitor PP2 or coexpression of kinase-dead c-Src. Cav1.2c constructs mutated at one of two COOH-terminal residues (Y2122F and Y2139F) were used to test the effect of blocking putative phosphorylation sites for c-Src. Expression of Y2122F but not Y2139F Cav1.2c abrogated the potentiating effect of c-Src on Ca2+ sparklet activity. We could not detect a significant change in persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity or density in cells coexpressing Cav1.2c + PKC-α, regardless of whether WT or Y2122F Cav1.2c was used, or after PP2 application, suggesting that PKC-α does not act upstream of c-Src to produce persistent Ca2+ sparklets. However, our results indicate that persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity is promoted by the action of c-Src on residue Y2122 of the Cav1.2c COOH terminus.

Keywords: calcium entry, L-type calcium channel, patch clamp, PKC, TIRF microscopy

l-type calcium (cav1.2) channels are a primary pathway for Ca2+ entry in smooth muscle cells (SMCs) and, therefore, play a key role in regulation of vascular tone (18, 29). Previous studies on Cav1.2 channels have revealed the occurrence of a high activity-gating mode characterized by frequent, prolonged channel openings, in addition to a more prevalent gating mode with brief and rare channel openings (13, 23, 24, 39). When recording Cav1.2 channel activity using total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, these low and high activity-gating modes correspond to low activity and persistent Ca2+ sparklets, respectively (23, 24, 27, 34).

Persistent Ca2+ sparklets account for ∼50% of the steady-state Ca2+ entry through Cav1.2 channels under physiological conditions, even though they constitute a very small population of the total Cav1.2 channels on the plasma membrane (1). Furthermore, an increase in persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity has been shown to underlie increased intracellular Ca2+ during angiotensin II-induced hypertension and hyperglycemia (27, 28). This evidence points to an important physiological role for the small population of Cav1.2 channels that conforms to persistent Ca2+ sparklets. In vascular smooth muscle, these events are thought to be highly regulated by the classical isoform of protein kinase C (PKC-α; Refs. 4, 5), and membrane targeting of PKC-α by A-kinase anchoring protein 150 (AKAP150) is considered essential in this process (27).

However, the mechanism of PKC-α action on Cav1.2 channels that results in the induction of persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity is not clear. Biochemical evidence points to residue S1928, the canonical PKA phosphorylation site on Cav1.2a, (corresponding to S1901 on Cav1.2c), as a PKC phosphorylation site (36) but whether the phosphorylation of S1928 by PKC-α translates into an increase in channel function remains unresolved. Electrophysiological and imaging studies demonstrating the regulation of persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity by PKC-α have not addressed the question of whether PKC-α phosphorylates the Cav1.2 α-subunit directly or acts via another kinase. While c-Src, another highly expressed kinase in SMCs, is known to directly phosphorylate the Cav1.2 channel and potentiate whole cell Cav1.2 current (2, 12, 14–17, 35, 36), its role in producing persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity through Cav1.2 channels has not been explored. Regulation of persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity by c-Src may or may not be related to PKC-α as several isoforms of PKC have been shown to activate c-Src (3–5, 11). On the basis of this evidence, we hypothesized that c-Src regulates persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity and that at least part of the effect of PKC-α on persistent sparklet activity is mediated through c-Src.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture and transfection of tsA-201 cells.

The cells were maintained at 37°C in a 5% CO2 incubator in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% penicillin and streptomycin solution. tsA-201 cells between passages 6 and 25 were plated on autoclaved glass coverslips in 35-mm Petri dishes, 24–48 h before transfection. These cells are derived from a human embryonic kidney cell line and immortalized by expression of the T antigen; they do not express any endogenous voltage-gated calcium channels. Cells were transfected with Cav1.2 channel subunits [wild-type (WT)/mutant α1C, β1b, and α2δ] along with either green fluorescent protein (GFP) or protein kinase constructs tagged with GFP, using jetPEI (Polyplus transfection). In all protocols, 840 ng of α1c cDNA and 200 ng each of α2-δ and β1b were used for transfection in a 35-mm dish with ∼70% cell confluency. When appropriate, 200 ng c-Src-GFP, PKC-α, and/or GFP cDNA were added to the transfection mixture. Successfully transfected cells were identified on the basis of GFP fluorescence. To confirm that cotransfection of a kinase cDNA with Cav1.2c cDNA does not alter the expression of Cav1.2c, we compared current densities in cells expressing Cav1.2c alone with those of cells coexpressing Cav1.2c and c-Src. Both groups were found to have similar current densities [WT Cav1.2c peak calcium current (ICa) = 8.99 ± 2.18 pA/pF (n = 18); and WT Cav1.2c + c-Src peak ICa = 10.29 ± 2.66 pA/pF (n = 16)] indicating that cotransfection with a kinase cDNA does not significantly impact expression levels of Cav1.2c.

Rat neuronal WT α1C (accession no. P22002), β1b, and α2δ DNA, subcloned into pcDNA3.1 vectors, were gifts from Dr. G. W. Zamponi. Site-directed mutagenesis was carried out in the laboratory of Zamponi (12) to obtain Y2122F and Y2139F mutations of the rat neuronal α1C-subunit. PKC-α tagged with GFP was a gift from Dr. J. Exton. Kinase-dead (kd) c-Src and c-Src tagged with GFP were gifts from Dr. A. P. Braun and Dr. G. E. Davis, respectively.

Electrophysiology.

tsA-201 cells were voltage clamped at −70 mV in the whole cell configuration using an EPC10 (HEKA, Bellmore, NY) or Axopatch 200B (Axon Instruments, Union City, CA) patch-clamp amplifier controlled by Patchmaster (HEKA) or pClamp (Axon Instruments) software, respectively. The cells were perfused with a solution composed of the following (in mM): 140 N-methyl-d-glucamine, 5 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 10 glucose, 10 HEPES, and 2 CaCl2. After gigaseal formation, the bath solution was switched to a solution containing 20 mM CaCl2 and 120 N-methyl-d-glucamine without any change in the concentrations of the other constituents. The patch pipette solution consisted of the following (in mM): 87 Cs-Asp, 20 CsCl, 1 MgCl2, 5 MgATP, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, and 0.2 Rhod-2. The pH of bath and patch pipette solutions were adjusted to 7.4 using HCl and 7.2 using CsOH, respectively. Patch pipettes filled with pipette solution exhibited resistances between 3 and 6 MΩ. All experiments were performed at room temperature (23, 24).

TIRF microscopy.

Voltage-clamped tsA-201 cells were imaged using a through-the-lens TIRF system coupled to an IX-71 Olympus microscope that was integrated with a high-speed Andor iXON EMCCD camera (Belfast, Ireland). The microscope was equipped with an Olympus PlanApo (×60, 1.45 NA) oil immersion objective and appropriate filter sets to separate excitation (491 nm for GFP and 563 nm for Rhod-2) and emission wavelengths. Images were acquired at a frequency >100 Hz using TILL imaging software (TILL Photonics, Rochester, NY), which also controlled the laser intensity and angle of laser incidence on the objective.

The acquired images were imported into a custom analysis program written in Interactive Data Language (IDL; ITTVIS, Boulder, CO) to perform Ca2+ sparklet detection using the amplitude threshold criteria (23, 24). Briefly, a Ca2+ fluorescence transient qualified as a sparklet if the average fluorescence amplitude of the 3 × 3 grid of the adjoining pixels (centered at the pixel with the highest fluorescence amplitude) was equal to or greater than the mean basal fluorescence plus 2.5 times its standard deviation.

Mean Ca2+ sparklet activity and Ca2+ sparklet density analysis.

To test our hypothesis, we compared two parameters across different test groups: mean Ca2+ sparklet activity (nPs) and mean persistent Ca2+ sparklet density.

In previous Ca2+ sparklet studies (23–27), Ca2+ sparklet activity was determined using nPs analysis (where n = no. of quantal levels and Ps = probability of occurrence of Ca2+ sparklet), which is analogous to open probability (nPo) analysis for single-channel data. We followed a similar approach in this study with one difference. Instead of converting fluorescence units to Ca2+ concentration, we computed ΔFtotal at each time point in Ca2+ sparklet traces. First, the total fluorescence intensity, Ftotal, for each time point was calculated by summing the Rhod-2 fluorescence over a predefined region from the raw image stacks acquired over a fixed length of time. The area of the predefined region was greater than the entire fluorescence signal produced by the Ca2+ sparklet. Subsequently, Ftotal of the basal fluorescence value was subtracted from Ftotal observed during channel opening to determine ΔFtotal value (1). The quantal ΔFtotal value (2,500 arbitrary units), q, was calculated by plotting an all-points histogram of several Ca2+ sparklet traces and then fitting the histogram with a multicomponent Gaussian function. Following that, nPs analysis was performed on Ca2+ sparklet traces using “threshold detection analysis” with no duration constraints and a q value of 2,500 arbitrary units in pClamp 9.0. For the purpose of quantal value comparison with previous Ca2+ sparklet studies, we converted the fluorescence from some of our Ca2+ sparklet traces to Ca2+ concentration and obtained a Ca2+ sparklet quantal value of 34.4 nM (data not shown); this quantal value was similar to that obtained in other Ca2+ sparklet studies (23–25).

Persistent Ca2+ sparklet density in each cell was determined by dividing the number of persistent Ca2+ sparklet sites by the area of the cell visible in its TIRF image.

Data from cells that were transfected with Cav1.2c but did not exhibit measurable ICa upon depolarization were not included in the analyses. For mean nPs calculation, we did not consider cells in which sparklet activity could not be detected even if they expressed measurable ICa because it was not possible to calculate an accurate nPs value in such cases. However, those cells were accounted for in persistent Ca2+ sparklet density analysis since any cell that did not exhibit persistent Ca2+ sparklets could be assigned a sparklet density value of 0. In addition, we found that 9–10% of our traces fell into the nonstationary category (e.g., Fig. 4A). This was due to the limitation of our image acquisition software where some of the images were acquired during the occurrence of a sparklet event. Inclusion of such traces would lead to an inaccurate estimate (on the lower side) of nPs. However, every nonstationary trace in this study could be very clearly classified as a persistent or low sparklet activity group except for two traces. Putting those data in either sparklet activity group did not alter our conclusions.

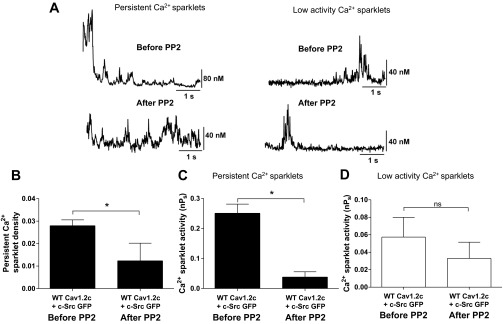

Fig. 4.

Effect of PP2 (10 μM) on Ca2+ sparklets in tsA-201 cells coexpressing WT Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 5). A: representative traces of persistent and low activity Ca2+ sparklets before and after application of PP2 (10 μM). B: bar plot of means ± SE persistent Ca2+ sparklet density before and after PP2 application (N = 5). Bar plots of mean nPs ± SE of persistent (C; N = 5) and low activity (D; N = 6) Ca2+ sparklet sites before and after PP2 application. Error bars represent SE values; n, number of cells; N, number of sparklet sites; *P < 0.05.

Application of drugs.

Xestospongin C (90 μM) was included in the patch-pipette solution to block inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors. Tetracaine (50 μM) was added to the bath solution to inhibit ryanodine receptors. For some experiments, PP2 (10 μM) was included in the bath solution to inhibit c-Src activity.

Statistical analysis.

Previous analyses of Ca2+ sparklet density and Ca2+ sparklet activity by two of our laboratories (1, 23–28) have shown that while sparklet density follows a normal distribution, sparklet activity does not if it is not divided into low and persistent sparklet sites. Parametric statistical analyses are appropriate for normally distributed data and nonparametric analyses for nonnormally distributed data. Here, the data as presented followed a normal distribution and thus parametric analyses were used. A one-tail unpaired t-test was used to compare the Ca2+ sparklet activities and persistent Ca2+ sparklet densities of the control and test groups. A one-tail paired t-test was used to evaluate the effect of PP2 on Ca2+ sparklets. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Chemical reagents.

Xestospongin C and PP2 were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA). Rhod-2 was procured from Invitrogen (San Diego, CA). All other chemicals were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

RESULTS

Ca2+ fluorescence events in tsA-201 cells.

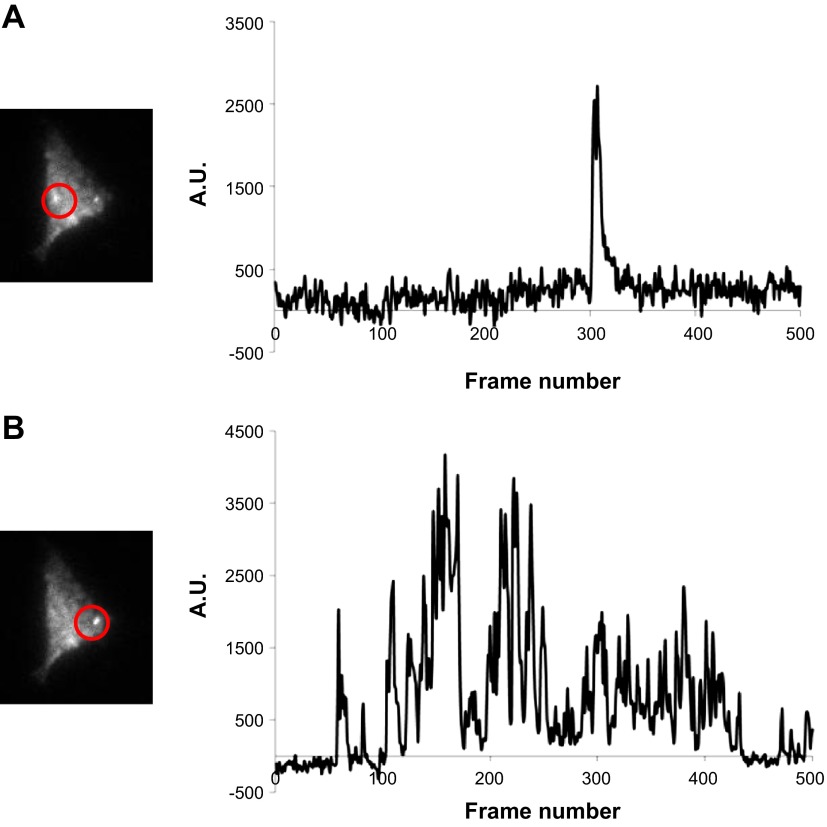

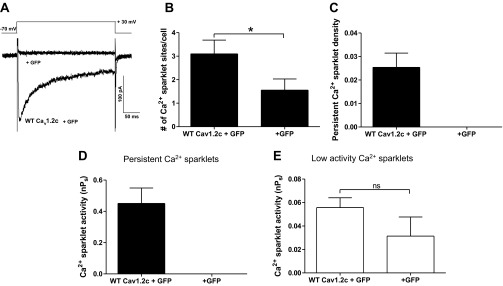

TIRF imaging of cells expressing WT Cav1.2c channels confirmed the presence of Ca2+ sparklets (Fig. 1). Based on their nPs values, Ca2+ sparklets were characterized as either persistent (nPs ≥ 0.2) or low (nPs < 0.2) activity events. We also recorded Ca2+ fluorescence events similar to Ca2+ sparklets from cells expressing GFP alone in the absence of measurable ICa upon depolarization (Fig. 2A). Since we had no objective reasons for excluding such anomalous events, they were analyzed in the same manner as Ca2+ sparklets. Importantly, the mean number of anomalous event sites per cell in cells expressing GFP alone (n = 9 cells) was significantly lower than the mean number of Ca2+ sparklet sites per cell observed after expression of Cav1.2c channels (+GFP; n = 10 cells; P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). Persistent Ca2+ sparklets were not observed in absence of Cav1.2c expression (Fig. 2, C and D), and the activity of all anomalous events, measured as nPs, was <0.2, similar to low activity Ca2+ sparklets (Fig. 2E). These results indicated that Cav1.2c channels were responsible for all of the persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity under the recording conditions used in our experiments and the occurrence and inclusion of anomalous Ca2+ events would not influence the persistent Ca2+ sparklet data analysis in further protocols.

Fig. 1.

Total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) images and fluorescence traces from a tsA-201 cell exhibiting low activity (A) and persistent Ca2+ sparklets (B). AU, arbitrary units.

Fig. 2.

Whole cell Ca2+ current and Ca2+ sparklet activity in tsA-201 cells expressing wild-type (WT) Cav1.2c + green fluorescent protein (GFP) or GFP alone. A: representative calcium current (ICa) traces evoked by a depolarization step from −70 mV to +30 mV in GFP alone and WT Cav1.2c expressing tsA-201 cells. Bar plots of means ± SE (B) Ca2+ sparklet or anomalous Ca2+ fluorescence event sites per cell and (C) persistent Ca2+ sparklet densities in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + GFP (n = 10) and GFP alone (n = 9). Bar plots of mean Ca2+ sparklet activity (nPs; where n = no. of quantal levels and Ps = probability of occurrence of Ca2+ sparklet) ± SE of persistent (D) and low (E) activity Ca2+ sparklets in cells expressing GFP alone (n = 7) and WT Cav1.2c + GFP (n = 10). Error bars represent SE values; n, number of cells; *P < 0.05.

c-Src underlies persistent Ca2+ sparklets through Cav1.2c in tsA-201 cells.

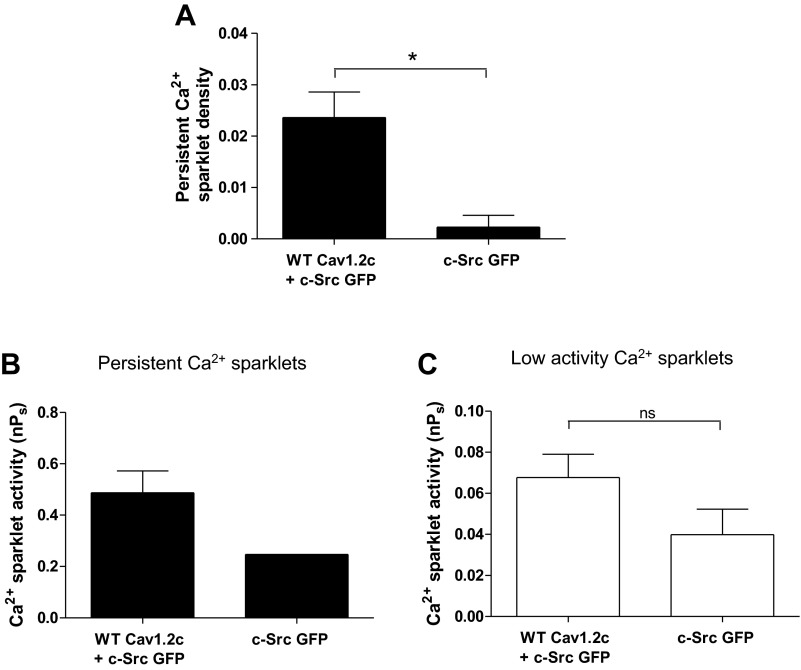

To investigate the role of c-Src in regulation of persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity, we employed pharmacological means as well as manipulated the expression of proteins of interest in tsA-201 cells. First, TIRF imaging was performed on tsA-201 cells expressing c-Src alone and WT Cav1.2c + c-Src. The latter test group (n = 9 cells) exhibited almost 10-fold higher persistent Ca2+ sparklet density than cells expressing only c-Src (n = 9 cells; P < 0.05; Fig. 3A). Similar to nontransfected cells, we also observed anomalous Ca2+ events in cells expressing c-Src alone (Fig. 3, B and C). However, all of these anomalous Ca2+ events had nPs <0.2 with the exception of one event (n = 9 cells). These data further corroborated our inference that the occurrence of anomalous Ca2+ events would not substantially affect persistent Ca2+ sparklet data analysis. Of note, the activity and density of persistent Ca2+ sparklets in cells coexpressing WT Cav1.2c and c-Src were similar to those observed in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c alone (compare Figs. 2 and 3). This observation suggests at least two possible explanations. First, c-Src may not be involved in the production of persistent Ca2+ sparklets. Second, endogenous c-Src expression may be sufficient to promote persistent sparklet activity. Indeed, tsA-201 cells have been shown previously to express endogenous c-Src (12).

Fig. 3.

Ca2+ sparklet analysis in tsA-201 cells expressing c-Src alone or with WT Cav1.2c. A: bar plot of means ± SE persistent Ca2+ sparklet density in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 9) and c-Src alone (n = 9). Bar plots of mean nPs ± SE of persistent (B) and low (C) activity Ca2+ sparklets in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 8) or c-Src alone (n = 6). Error bars represent SE values; n, number of cells; *P < 0.05.

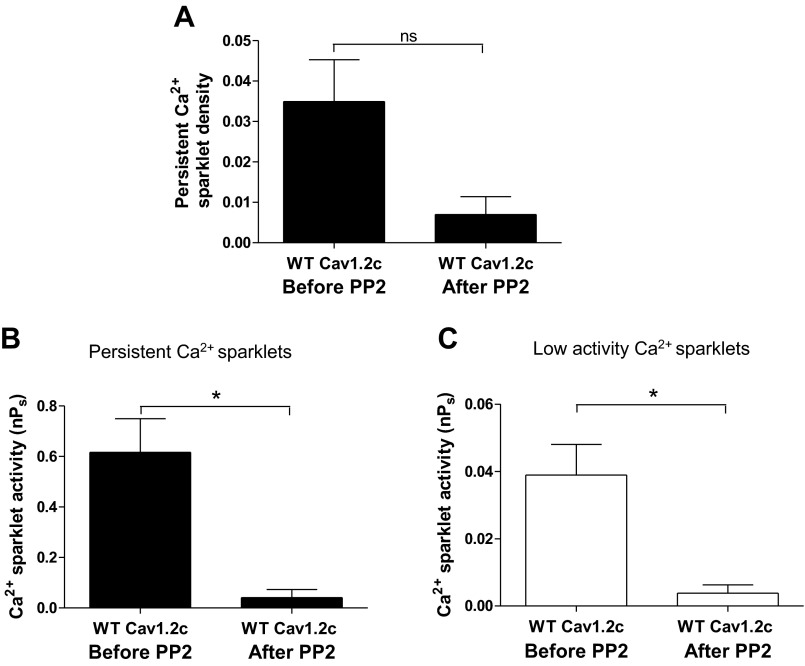

We substantiated the role of c-Src in producing persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity through Cav1.2c by recording Ca2+ sparklets from cells coexpressing WT Cav1.2c and c-Src before and after treatment with 10 μM PP2, a membrane-permeable c-Src antagonist (Fig. 4). Application of PP2 resulted in a 2.3- and 6.5-fold decrease in the mean density and activity respectively, of persistent Ca2+ sparklets (N = 5 sparklet sites; n = 5 cells; P < 0.05; Fig. 4, A–C) without significantly changing the mean activity of low activity Ca2+ sparklet sites (N = 6 sparklet sites; n = 5 cells; P > 0.05; Fig. 4D). To address whether endogenous c-Src was responsible for producing persistent Ca2+ sparklets, we tested the effect of PP2 on Ca2+ sparklet activity in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c alone. Indeed, PP2 application decreased persistent Ca2+ sparklet density (Fig. 5A) while reducing Ca2+ sparklet activity significantly in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c alone (N = 8 sparklet sites; n = 5 cells; P < 0.05; Fig. 5B). Interestingly, PP2 treatment also resulted in a significant reduction in the activity of low activity Ca2+ sparklets (N = 13 sparklet sites; n = 5 cells; P < 0.05; Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Effect of PP2 (10 μM) on Ca2+ sparklets in tsA-201 cells expressing WT Cav1.2c alone (n = 5). A: bar plot of means ± SE persistent Ca2+ sparklet density before and after PP2 application (N = 5). Bar plots of means nPs ± SE of persistent (B; N = 8) and low activity (C; N = 13) Ca2+ sparklet sites before and after PP2 application. Error bars represent SE values; n, number of cells; N, number of sparklet sites; *P < 0.05.

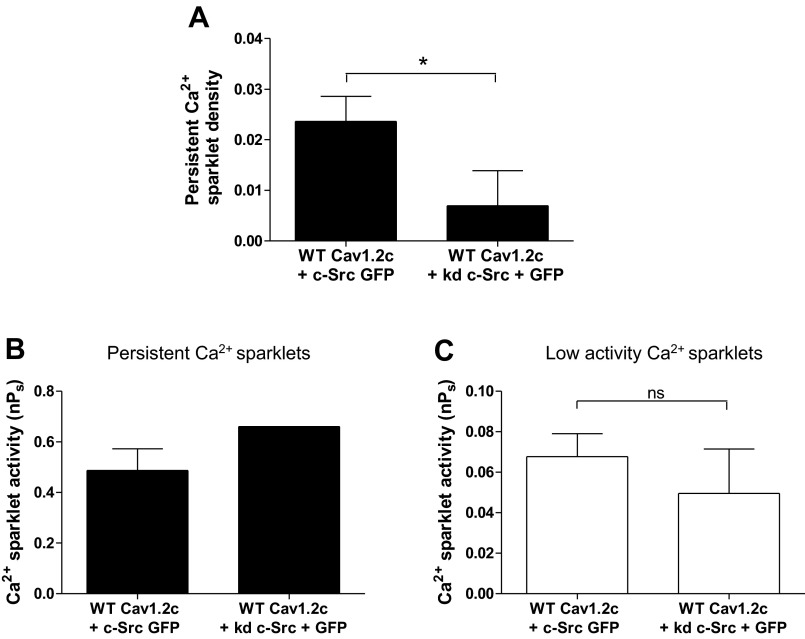

To further test the involvement of c-Src, we coexpressed WT Cav1.2c with kinase dead c-Src (kd c-Src) in tsA-201 cells to competitively inhibit endogenous c-Src (Fig. 6). kd c-Src harbors a single point mutation in the kinase domain of the enzyme resulting in ablation of c-Src kinase activity. Out of six cells cotransfected with WT Cav1.2c and kd c-Src, persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity was detected in only one cell. Evaluation of persistent Ca2+ sparklet density revealed a 3.4-fold reduction in cells transfected with WT Cav1.2c and kd c-Src (n = 6 cells) compared with cells coexpressing WT Cav1.2c and c-Src (n = 9 cells; P < 0.05; Fig. 6A). The means of persistent Ca2+ sparklet activities of the two transfection groups were comparable but could not be statistically compared due to an insufficient number of persistent sparklets in the WT Cav1.2c + kd c-Src transfection group (Fig. 6B). As expected, the means for nPs of low activity Ca2+ sparklets in cells coexpressing c-Src or kd c-Src with WT Cav1.2c were similar (Fig. 6C). Collectively, these data suggest that c-Src expression promotes persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity.

Fig. 6.

Ca2+ sparklet analysis in tsA-201 cells expressing WT Cav1.2c with c-Src or kd c-Src. A: bar plot of means ± SE persistent Ca2+ sparklet density in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 9) and WT Cav1.2c + kd c-Src (n = 6). Bar plots of mean nPs ± SE of persistent (B) and low (C) activity Ca2+ sparklets in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 8) and WT Cav1.2c + kd c-Src (n = 3). Error bars represent SE values; n, number of cells; *P < 0.05.

c-Src phosphorylates Cav1.2c at residue Y2122 to produce persistent Ca2+ sparklets.

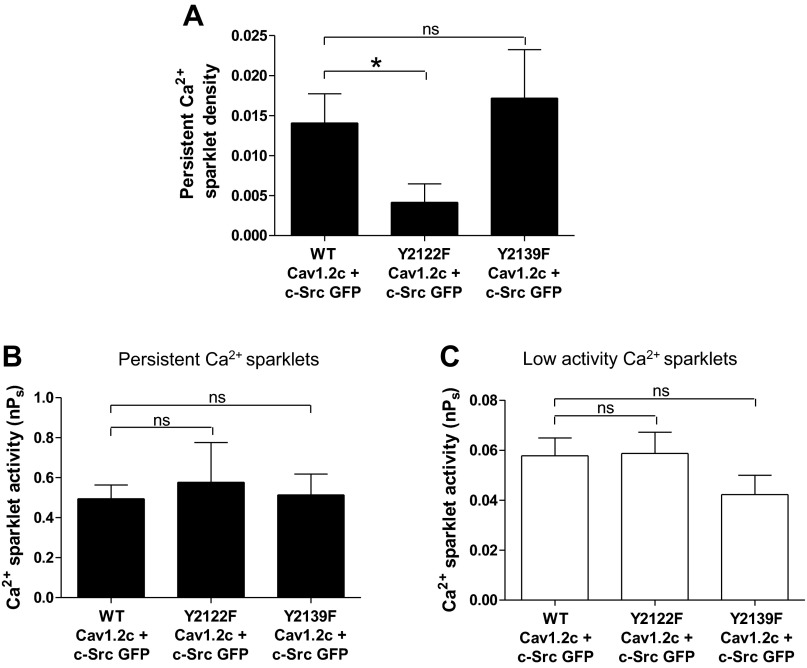

To elucidate the mechanism by which c-Src enhances Cav1.2c activity, we tested the role of two potential phosphorylation sites (Y2122 and Y2139) on the COOH terminus of rat Cav1.2c (2, 12). Coexpression of the Y2122F Cav1.2c construct with c-Src (n = 19 cells) resulted in a 3.4-fold decrease in the density of persistent Ca2+ sparklets with respect to cells transfected with WT Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 19 cells; P < 0.05; Fig. 7A). No such differences were observed between mean persistent Ca2+ sparklet densities of cells expressing Y2139F Cav1.2c + c-Src and WT Cav1.2c + c-Src (P > 0.05; Fig. 7A). Neither of the single point mutations on Cav1.2c led to significant changes in the mean activities of persistent or low activity Ca2+ sparklets compared with cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + c-Src (Fig. 7, B and C). These findings suggest that Y2122 on the COOH terminus of Cav1.2c is the major phosphorylation site involved in production of persistent Ca2+ sparklets by c-Src.

Fig. 7.

Ca2+ sparklet analysis in tsA-201 cells coexpressing c-Src with WT, Y2122F or Y2139F Cav1.2c constructs. A: bar plot of means ± SE persistent Ca2+ sparklet density in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 19), Y2122F Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 19), and Y2139F Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 17). Bar plots of mean nPs ± SE of persistent (B) and low (C) activity Ca2+ sparklets in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 17), Y2122F Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 17), and Y2139F Cav1.2c + c-Src (n = 12). Error bars represent SE values; n, number of cells; *P < 0.05.

PKC-α does not induce persistent Ca2+ sparklets via c-Src.

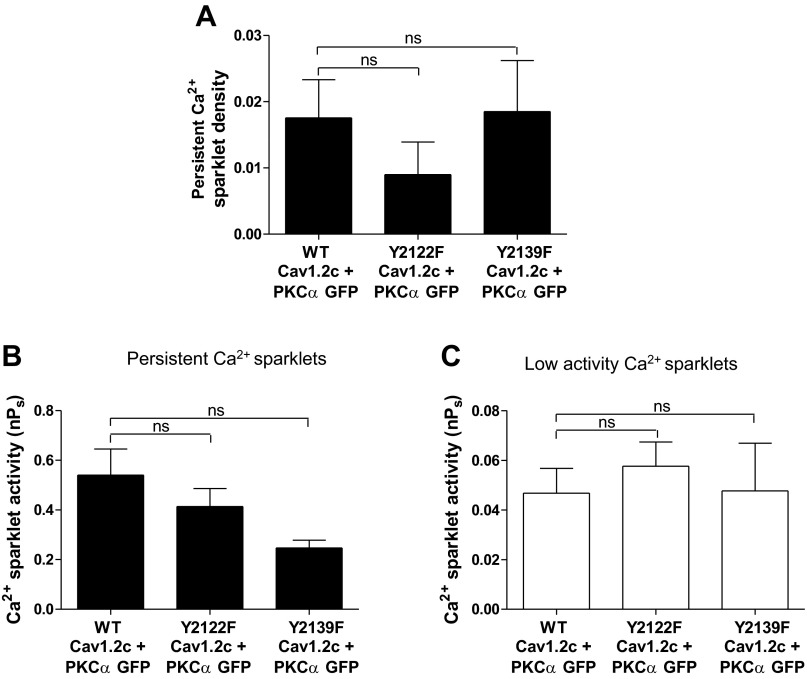

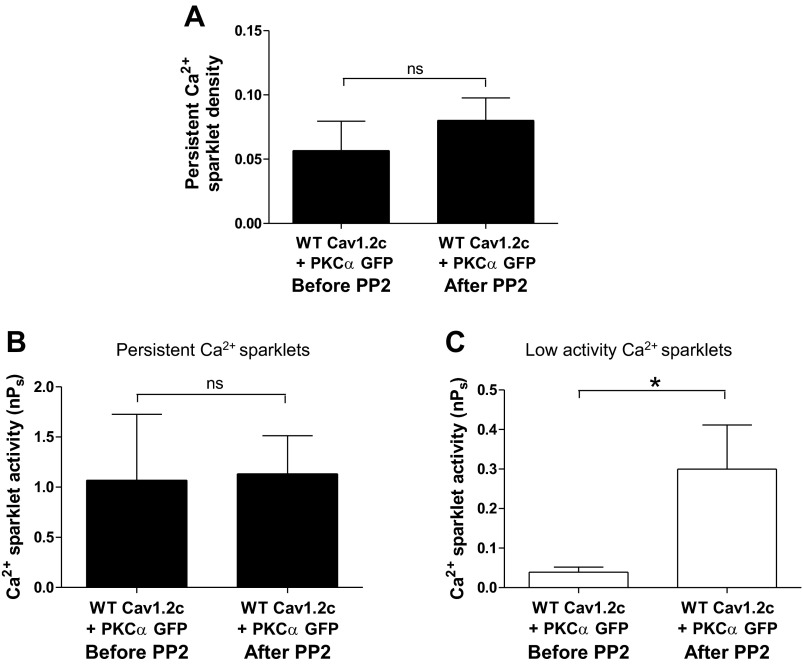

To test if PKC-α induces persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity by activating endogenous c-Src, we performed Ca2+ sparklet experiments on cells coexpressing PKC-α and Y2122F Cav1.2c, Y2139F Cav1.2c, or WT Cav1.2c. The mean persistent Ca2+ sparklet densities of the Y2122F Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 12 cells) and Y2139 F Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 8 cells) transfection groups did not show any significant reduction compared with the WT Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 9 cells) transfection group (Fig. 8A). Similarly, the mean nPs values of both low and persistent Ca2+ sparklets in cells expressing Y2122F Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 7 cells; P > 0.05) or Y2139F Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 7 cells; P > 0.05) were similar to those in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 9 cells) (Fig. 8, B and C). Furthermore, inhibition of endogenous c-Src by PP2 (10 μM) did not change the activity (N = 4 sparklet sites; n = 3 cells) or the density (N = 3 sparklet sites; n = 3 cells) of PKC-α-induced persistent Ca2+ sparklets in cells coexpressing PKC-α and WT Cav1.2c (P > 0.05; Fig. 9, A and B). In contrast, PP2 application led to an increase in the activity of low activity Ca2+ sparklet sites (N = 9 sparklet sites; n = 7 cells; P < 0.05; Fig. 9C). Overall, these data suggest that PKC-α does not induce persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity through c-Src.

Fig. 8.

Ca2+ sparklet analysis in tsA-201 cells coexpressing PKC-α with WT, Y2122F or Y2139F Cav1.2c constructs. A: bar plot of means ± SE persistent Ca2+ sparklet density in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 9), Y2122F Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 12), and Y2139F Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 8). Bar plots of mean nPs ± SE of persistent (B) and low (C) activity Ca2+ sparklets in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 9), Y2122F Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 7), and Y2139F Cav1.2c + PKC-α (n = 7). Error bars represent SE values; n, number of cells.

Fig. 9.

Effect of PP2 (10 μM) on Ca2+ sparklets in tsA-201 cells coexpressing WT Cav1.2c and PKC-α. A: bar plot of means ± SE of persistent Ca2+ sparklet density before and after PP2 application (N = 3; n = 3). Bar plots of mean nPs ± SE of persistent (B; N = 4; n = 3) and low activity (C; N = 9; n = 7) Ca2+ sparklet sites before and after PP2 application. Error bars represent SE values; n, number of cells; N, number of sparklet sites; *P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The present study is the first to investigate the role of c-Src in the production of persistent Ca2+ sparklets. Our findings suggest that c-Src promotes persistent Ca2+ sparklets by phosphorylation of Cav1.2c on residue Y2122. We could not find evidence that PKC-α acts via c-Src to induce persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity of Cav1.2c. The possibility of parallel actions of c-Src and PKC-α conforms to existing ideas about the complex regulation of Cav1.2 channels to fully explain their central roles in the regulation of many physiological functions.

One challenge that arose in the present study was dealing with the presence of anomalous Ca2+ events in untransfected tsA-201 cells. The origin of these anomalous events could not be resolved, but they might be related to the endogenous expression of Ca2+-permeable transient receptor potential channels in this cell line. Similar events have been observed in Xenopus oocytes expressing N-type Ca2+ channels at negative (−60 to −120 mV) holding potentials and have been reported to have similar amplitudes, durations and spatial spread as N-type Ca2+ channel fluorescence events (7). Reportedly, the amplitudes of those anomalous events decreased with the application of depolarizing pulses that were used to record events associated with N-type Ca2+ channels. We could not use a similar strategy to eliminate anomalous Ca2+ events for at least two reasons: 1) Cav1.2 channels exhibit a higher open probability with membrane depolarization, which results in increased basal Ca2+ fluorescence (24); and 2) the driving force for Ca2+ decreases at higher potentials, leading to smaller changes in Ca2+ fluorescence upon Cav1.2 channel opening that are more difficult to resolve. Due to these limitations, we focused primarily on the analysis of persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity. The frequency of anomalous Ca2+ events resembling persistent Ca2+ sparklets was very low, thus making our results less prone to errors caused by the presence of such events among persistent Ca2+ sparklets in cells that expressed Cav1.2c alone or with kinases.

Effect of c-Src on persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity.

c-Src activation has previously been shown to increase whole cell Cav1.2c current in response to insulin-like growth factor-I and α5β1 integrin activation (2, 12, 36), and c-Src has been implicated in the basal regulation of Cav1.2c current as well (36). In the present study, we tested the involvement of c-Src in the production of persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity. Our results suggest that c-Src promotes persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity by acting on residue Y2122 of the COOH terminus of Cav1.2c (Fig. 7). Of the various intracellular regions on rat Cav1.2c, only the region from amino acid residues 1,932 to 2,143, containing tyrosine residues at positions 2,122 and 2,139, is known to be phosphorylated by c-Src (2). Furthermore, previous studies have provided evidence for phosphorylation of Y2122 by c-Src, resulting in an increase in Cav1.2 channel current (2, 12, 36). Interestingly, in the present study, mutation of Y2122 on Cav1.2c did not completely eliminate persistent Ca2+ sparklets (Fig. 7, A and B). There are at least two possible explanations for the residual persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity: 1) c-Src phosphorylates another tyrosine residue on Cav1.2c, or 2) the presence of another Cav1.2c activating mechanism independent of c-Src. Here, we used PP2 treatment and kd c-Src overexpression to selectively inhibit c-Src-induced persistent Ca2+ sparklets. These c-Src inhibition strategies have been used successfully in previous studies (2, 12, 36), and both approaches attenuated the occurrence of persistent Ca2+ sparklets here (Figs. 4 and 6).

An interesting observation was that PP2 application significantly reduced both persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity and density in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c and c-Src whereas the Y2122F mutation on Cav1.2c or expression of kd c-Src had an effect only on persistent Ca2+ sparklet density. Exclusion of cells that did not show any sparklet activity (see materials and methods) based on nPs analysis may have masked the attenuating effect of the Y2122F mutation or kd c-Src expression on nPs values. Another plausible explanation could be the presence of a population of persistent Ca2+ sparklets regulated by another kinase like PKC in addition to that promoted by c-Src. Such a population of persistent Ca2+ sparklets might not be affected by the Y2122F mutation or kd c-Src expression.

The activity of a channel at any given time is determined by the balance of the activity of specific kinases and phosphatases in its immediate vicinity. The balance between the local activities of PKC-α, PP2A, and PP2B has previously been suggested to produce different patterns of Cav1.2 activity across the plasma membrane, and these sites with differential activities have been classified as silent, low, and persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity sites (23). Preferential phosphorylation of some Cav1.2 channels over the others by PKC-α, based on the colocalization of PKC-α with Cav1.2, has been suggested to be responsible for the production of localized persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity (24). Immunofluorescence and confocal imaging experiments indicate that Cav1.2 channels have a diffuse distribution while PKC-α is distributed in clusters near the plasma membrane (24). Whether c-Src has a clustered distribution on the cell membrane under the conditions of our experiments is not known; however, c-Src has been shown in multiple studies to localize preferentially to focal adhesions (36, 20). Based on the observation that both low activity and persistent Ca2+ sparklets occur in cells transfected with WT Cav1.2c and c-Src, we can speculate that c-Src, like PKC-α, regulates a small population of Cav1.2 channels on the plasma membrane. In that case, the activity of a sparklet site may be determined by the activities of nearby c-Src and possibly unidentified phosphatases.

Although the experiments in this study were performed on tsA-201 cells expressing Cav1.2c, it is highly likely that c-Src also induces persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity in native vascular smooth muscle cells. Most vascular smooth muscle cells have high expression levels of c-Src (30). c-Src activation has been shown to increase Cav1.2 current in rat arteriolar, rabbit portal vein, and human colonic smooth muscle cells (5, 12, 14–17, 36). Because Cav1.2c and Cav1.2b share identical sequences (in rat) around residue Y2122, these results are likely to be applicable to rat Cav1.2b. Both rabbit and human Cav1.2b lack the tyrosine residue corresponding to Y2122, suggesting that in those species Cav1.2b is phosphorylated by c-Src at other tyrosine residues (17).

Mechanism of PKC-α action on persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity.

PKC-α activation is linked to an increase in persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity in freshly isolated cerebral arterial myocytes and in tsA-201 cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + PKC-α (23, 24); however, the mechanism by which PKC-α acts on Cav1.2 channels is not well understood. In this study, we tested whether c-Src acts downstream of PKC-α in the series of events that lead to increased persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity. PKC has been shown to lie upstream of c-Src in signaling pathways controlling actin reorganization (3, 4), podosome formation (11), as well as in the regulation of smooth muscle Cav1.2 channels in smooth muscle (5). PKC may activate c-Src directly or indirectly, and c-Src activation mechanisms may also vary among the various PKC isoforms expressed by any particular cell type. If PKC-α acts solely via c-Src to produce persistent Ca2+ sparklets, mutation of Y2122 should have resulted in at least a partial reduction of persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity. However, the data in Fig. 8 do not support such an effect. Furthermore, PP2 application did not significantly change persistent Ca2+ sparklet density or activity in cells coexpressing WT Cav1.2c + PKC-α (Fig. 9, A and B). These data clearly suggest that PKC-α induces persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity in a c-Src independent manner. In the same test groups, the PP2-induced increase in nPs of low activity Ca2+ sparklets was intriguing (Fig. 9C), particularly as PP2 inhibited low activity Ca2+ sparklets in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c alone (Fig. 5C). This fundamental difference in the effect of PP2 on low activity Ca2+ sparklets in the presence or absence of PKC-α may be related to the ∼10-fold difference in the basal nPs level for low activity Ca2+ sparklets. A possible explanation is that PP2 is acting to inhibit c-Src phosphorylation of tyrosine residues in other regions of Cav1.2 when PKC is activated.

By what alternative mechanisms could PKC-α induce persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity? It is possible that PKC-α directly phosphorylates Cav1.2c to produce persistent Ca2+ sparklets. The NH2 terminus of the cardiac Cav1.2 isoform has been implicated in both PKC-mediated stimulation and inhibition of Cav1.2 (21, 31, 32), but the NH2 terminus of the (neuronal) Cav1.2c isoform lacks the potential serine and threonine PKC phosphorylation sites of the Cav1.2a (cardiac) and Cav1.2b (smooth muscle) isoforms. The occurrence of persistent Ca2+ sparklets in cells expressing WT Cav1.2c + PKC-α suggests that phosphorylation of the NH2 terminus of Cav1.2c by PKC-α is not required to produce persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity. Site S1901 on Cav1.2c (S1928 on Cav1.2a and b) is conserved among different Cav1.2 channel isoforms in different species and has long been considered the primary PKA phosphorylation site on Cav1.2 channels (6, 10, 22, 33). However, some recent studies have challenged the role of S1928 phosphorylation in PKA-mediated potentiation of Cav1.2 current (8, 9, 19) by suggesting that PKA acts primarily by phosphorylation of a more proximal residue, S1700 to relieve the inhibition by the noncovalently associated distal COOH-terminal inhibitory domain (8, 37). The S1928 residue of Cav1.2 is also implicated as a PKG phosphorylation site using in vitro kinase assays, but PKG phosphorylation of S1928 does not seem to be involved in PKG-mediated inhibition of Cav1.2 current. In addition, biochemical experiments provide evidence for S1928 phosphorylation by PKC-α (38), but whether this phosphorylation event translates into increased channel function or sparklet activity remains unknown.

In conclusion, our data show that c-Src can enhance the activity of persistent Ca2+ sparklets in transfected tsA-201 cells through phosphorylation of Cav1.2c at residue Y2122. However, cells coexpressing Y2122F Cav1.2c and PKC-α continue to show an increase in persistent Ca2+ sparklet activity. These findings indicate that PKC-α does not act upstream of c-Src to produce persistent Ca2+ sparklets under these conditions.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants P01 HL-095486, HL-085870, HL-085686, and HL-098200 and American Heart Association Grants 0735251N and 0840094N.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.G., L.F.S., and M.J.D. conception and design of research; J.G., M.F.N., P.G., J.-T.C., J.L.M., and L.F.S. performed experiments; J.G. and J.L.M. analyzed data; J.G., M.F.N., P.G., J.-T.C., L.F.S., and M.J.D. interpreted results of experiments; J.G., J.L.M., and M.J.D. prepared figures; J.G. and M.J.D. drafted manuscript; J.G., M.F.N., L.F.S., and M.J.D. edited and revised manuscript; J.G. and M.J.D. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amberg GC, Navedo MF, Nieves-Cintron M, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. Calcium sparklets regulate local and global calcium in murine arterial smooth muscle. J Physiol 579: 187–201, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bence-Hanulec KK, Marshall J, Blair LAC. Potentiation of neuronal L-type calcium channels by IGF-1 requires phosphorylation of the α1 subunit on a specific tyrosine residue. Neuron 27: 121–131, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt D, Gimona M, Hillmann M, Haller H, Mischak H. Protein kinase C induces actin reorganization via a Src- and Rho-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 277: 20903–20910, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandt DT, Goerke A, Heuer M, Gimona M, Leitges M, Kremmer E, Lammers R, Haller H, Mischak H. Protein kinase C delta induces Src kinase activity via activation of the protein tyrosine phosphatase PTP alpha. J Biol Chem 278: 34073–34078, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callaghan B, Koh SD, Keef KD. Muscarinic M2 receptor stimulation of Cav1.2b requires phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase, protein kinase C, and c-Src. Circ Res 94: 626–633, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Jongh KS, Murphy BJ, Colvin AA, Hell JW, Takahashi M, Catterall WA. Specific phosphorylation of a site in the full-length form of the alpha1 subunit of the cardiac L-type calcium channel by adenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Biochemistry 35: 10392–10402, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demuro A, Parker I. Optical single-channel recording: imaging Ca2+ flux through individual N-type voltage-gated channels expressed in Xenopus oocytes. Cell Calcium 34: 499–509, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuller MD, Emrick MA, Sadilek M, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Molecular mechanism of calcium channel regulation in the fight-or-flight response. Sci Signal 3: ra70, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ganesan AN, Maack C, Johns DC, Sidor A, O'Rourke B. β-Adrenergic stimulation of L-type Ca2+ channels in cardiac myocytes requires the distal carboxyl terminus of α1C but not serine 1928. Circ Res 98: e11–e18, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao T, Yatani A, Dell'Acqua ML, Sako H, Green SA, Dascal N, Scott JD, Hosey MM. cAMP-dependent regulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels requires membrane targeting of PKA and phosphorylation of channel subunits. Neuron 19: 185–196, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gatesman A, Walker VG, Baisden JM, Weed SA, Flynn DC. Protein kinase Cα activates c-Src and induces podosome formation via AFAP-110. Mol Cell Biol 24: 7578–7597, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gui P, Wu X, Ling S, Stotz SC, Winkfein RJ, Wilson E, Davis GE, Braun AP, Zamponi GW, Davis MJ. Integrin receptor activation triggers converging regulation of Cav1.2 calcium channels by c-Src and protein kinase A pathways. J Biol Chem 281: 14015–14025, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hess P, Lansman JB, Tsien RW. Different modes of Ca channel gating behaviour favoured by dihydropyridine Ca agonists and antagonists. Nature 311: 538–544, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu XQ, Singh N, Mukhopadhyay D, Akbarali HI. Modulation of voltage-dependent Ca2+ channels in rabbit colonic smooth muscle cells by c-Src and focal adhesion kinase. J Biol Chem 273: 5337–5342, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jiang LH, Gawler DJ, Hodson N, Milligan CJ, Pearson HA, Porter V, Wray D. Regulation of cloned cardiac L-type calcium channels by cGMP-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 273: 6135–6143, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jin X, Morsy N, Shoeb F, Zavzavadjian J, Akbarali HI. Coupling of M2 muscarinic receptor to L-type Ca2+ channel via c-src kinase in rabbit colonic circular smooth muscle. Gastroenterology 123: 827–834, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang M, Ross GR, Akbarali HI. COOH-terminal association of human smooth muscle calcium channel Cav1.2b with Src kinase protein binding domains: effect of nitrotyrosylation. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 293: C1983–C1990, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knot HJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J Physiol 508: 199–209, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lemke T, Welling A, Christel CJ, Blaich A, Bernhard D, Lenhardt P, Hofmann F, Moosmang S. Unchanged beta-adrenergic stimulation of cardiac L-type calcium channels in Cav1.2 phosphorylation site S1928A mutant mice. J Biol Chem 283: 34738–34744, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu R, Alioua A, Kumar Y, Kundu P, Eghbali M, Weisstaub NV, Gingrich JA, Stefani E, Toro L. c-Src tyrosine kinase, a critical component for 5-HT2A receptor-mediated contraction in rat aorta. J Physiol 586: 3855–3869, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McHugh D, Sharp EM, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Inhibition of cardiac L-type calcium channels by protein kinase C phosphorylation of two sites in the N-terminal domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 97: 12334–12338, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naguro I, Nagao T, Adachi-Akahane S. Ser1901 of [alpha]1C subunit is required for the PKA-mediated enhancement of L-type Ca2+ channel currents but not for the negative shift of activation. FEBS Lett 489: 87–91, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Nieves M, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. Mechanisms underlying heterogeneous Ca2+ sparklet activity in arterial smooth muscle. J Gen Physiol 127: 611–622, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Votaw VS, Santana LF. Constitutively active L-type Ca2+ channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 11112–11117, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navedo MF, Amberg GC, Westenbroek RE, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Catterall WA, Striessnig J, Santana LF. Cav1.3 channels produce persistent calcium sparklets, but Cav1.2 channels are responsible for sparklets in mouse arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H1359–H1370, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Navedo MF, Cheng EP, Yuan C, Votaw S, Molkentin JD, Scott JD, Santana LF. Increased coupled gating of L-type Ca2+ channels during hypertension and Timothy Syndrome. Circ Res 106: 748–756, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navedo MF, Nieves-Cintron M, Amberg GC, Yuan C, Votaw VS, Lederer WJ, McKnight GS, Santana LF. AKAP150 is required for stuttering persistent Ca2+ sparklets and angiotensin II-Induced hypertension. Circ Res 102: e1–e11, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Navedo MF, Takeda Y, Nieves-Cintron M, Molkentin JD, Santana LF. Elevated Ca2+ sparklet activity during acute hyperglycemia and diabetes in cerebral arterial smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 298: C211–C220, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson MT, Patlak JB, Worley JF, Standen NB. Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 259: C3–C18, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oda Y, Renaux B, Bjorge J, Saifeddine M, Fujita DJ, Hollenberg MD. cSrc is a major cytosolic tyrosine kinase in vascular tissue. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 77: 606–617, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shistik E, Ivanina T, Blumenstein Y, Dascal N. Crucial role of N terminus in function of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel and its modulation by protein kinase C. J Biol Chem 273: 17901–17909, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shistik E, Keren-Raifman T, Idelson GH, Blumenstein Y, Dascal N, Ivanina T. The N terminus of the cardiac L-type Ca2+ channel alpha(1C) subunit. J Biol Chem 274: 31145–31149, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Perets T, Blumenstein Y, Shistik E, Lotan I, Dascal N. A potential site of functional modulation by protein kinase A in the cardiac Ca2+ channel alpha 1C subunit. FEBS Lett 384: 189–192, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang SQ, Song LS, Lakatta EG, Cheng H. Ca2+ signalling between single L-type Ca2+ channels and ryanodine receptors in heart cells. Nature 410: 592–596, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wijetunge S, Hughes AD. Activation of endogenous c-Src or a related tyrosine kinase by intracellular (pY)EEI peptide increases voltage-operated calcium channel currents in rabbit ear artery cells. FEBS Lett 399: 63–66, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu X, Davis GE, Meininger GA, Wilson E, Davis MJ. Regulation of the L-type calcium channel by alpha5 beta1 integrin requires signaling between focal adhesion proteins. J Biol Chem 276: 30285–30292, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wei X, Neely A, Lacerda AE, Olcese R, Stefani E, Perez-Reyes E, Birnbaumer L. Modification of Ca2+ channel activity by deletions at the carboxyl terminus of the cardiac alpha 1 subunit. J Biol Chem 269: 1635–1640, 1994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yang L, Liu G, Zakharov SI, Morrow JP, Rybin VO, Steinberg SF, Marx SO. Ser1928 is a common site for Cav1.2 phosphorylation by protein kinase C isoforms. J Biol Chem 280: 207–214, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yue DT, Herzig S, Marban E. Beta-adrenergic stimulation of calcium channels occurs by potentiation of high-activity gating modes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 87: 753–757, 1990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]