Abstract

Connective tissue growth factor (CCN2/CTGF) mediates transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-induced fibrosis. Drug-induced gingival overgrowth is tissue specific. Here the role of the phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) pathway in mediating TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF expression in primary human adult gingival fibroblasts and human adult lung fibroblasts was compared. Data indicate that PI3K inhibitors attenuate upregulation of TGF-β1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression in human gingival fibroblasts independent of reducing JNK MAP kinase activation. Pharmacologic inhibitors and small interfering (si)RNA-mediated knockdown studies indicate that calcium-dependent isoforms and an atypical isoform of protein kinase C (PKC-δ) do not mediate TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF expression in gingival fibroblasts. As glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) can undergo phosphorylation by the PI3K/pathway, the effects of GSK-3β inhibitor kenpaullone and siRNA knockdown were investigated. Data in gingival fibroblasts indicate that kenpaullone attenuates TGF-β1-mediated CCN2/CTGF expression. Activation of the Wnt canonical pathways with Wnt3a, which inhibits GSK-3β, similarly inhibits TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF expression. In contrast, inhibition of GSK-3β by Wnt3a does not inhibit, but modestly stimulates, CCN2/CTGF levels in primary human adult lung fibroblasts and is β-catenin dependent, consistent with previous studies performed in other cell models. These data identify a novel pathway in gingival fibroblasts in which inhibition of GSK-3β attenuates CCN2/CTGF expression. In adult lung fibroblasts inhibition of GSK-3β modestly stimulates TGF-β1-regulated CCN2/CTGF expression. These studies have potential clinical relevance to the tissue specificity of drug-induced gingival overgrowth.

Keywords: CCN2, connective tissue growth factor, transforming growth factor, gingival growth, GSK-3β

gingival overgrowth is a side-effect of certain medications including the anticonvulsant phenytoin, dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine, and the immunosuppressant cyclosporine A (25, 43, 55, 61). This condition results in speech impairment and interference with mastication and jeopardizes effective oral hygiene leading to increased levels of oral microbes, with potential systemic consequences (10, 38). Strict oral plaque control and oral hygiene can reduce the severity of gingival overgrowth lesions (53), but this approach is recognized to have only limited effectiveness (34). Surgical treatments are unsatisfactory because repeated surgeries are required due to the recurrence of gingival overgrowth (42). The cessation of drug treatment can improve clinical outcomes but is not always possible (44, 56). Thus there is a need to understand the biological and molecular mechanisms that contribute to this condition to develop alternative prevention and treatment strategies.

Levels of transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) are significantly elevated in the lamina propria of gingival overgrowth compared with control tissues (54) and suggest that TGF-β1 contributes to the pathogenesis of drug-induced gingival overgrowth. Furthermore, TGF-β1 strongly induces the expression of connective tissue growth factor (CCN2/CTGF; Refs. 27, 47). Studies have also shown that TGF-β1 may initiate, but CCN2/CTGF sustains, the fibrotic response in fibroblasts obtained from patients with scleroderma (27). We have previously reported that gingival overgrowth lesions from patients taking phenytoin display an overexpression of CCN2/CTGF, in spite of the presence of inflammatory mediators that downregulate CCN2/CTGF in other tissues (28, 33, 64). Unique aspects of cAMP production and MAP kinase and Rho signaling partially account for this observation (5, 6). Therefore, CCN2/CTGF is an attractive potential therapeutic target to prevent or treat oral fibrotic disorders. Further work is required to understand tissue specific signaling relationships in TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF expression with the goal of identifying potential pharmacologic targets.

While signaling through SMADs is vital for TGF-β regulation of CCN2/CTGF (35, 68), we and others have shown that additional signaling pathways act in parallel with Smads to mediate tissue-specific TGF-β effects (5, 6), including the phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/AKT pathway (3, 18, 22, 40). Here we investigate in gingival and lung fibroblasts respective roles for PI3K, protein kinase C (PKC), and glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) in mediating TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF expression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell culture.

Primary human lung fibroblasts were purchased from Lonza. Primary human gingival fibroblasts were grown from explants obtained from three different adult donors without gingival overgrowth from the Clinical Research Center at Boston University Henry M. Goldman School of Dental Medicine, and cells were not used beyond passage 4 (26). Informed consent was obtained under an approved Boston University Institutional Review Board protocol. All cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 10% FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a fully humidified incubator in six-well plates. Cells were grown to 80% confluence and then placed in serum-free medium containing 0.1% BSA for a minimum of 12 h before treatment. Where indicated, specified inhibitors were added in serum-free medium containing 0.1% BSA for 30 or 60 min before treatment with 5 ng/ml TGFβ1 or vehicle for 6 h (5). The PI3K inhibitors (wortmannin and LY294002) and the JNK inhibitor SP600125 were obtained from Sigma. PKC inhibitors used were the broad-spectrum PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (Bis I; 10 μM; Calbiochem); Gö 6976, which selectively inhibits Ca2+-dependent PKC isozymes such as PKC-α (0.1 μM; Calbiochem); and rottlerin, which selectively inhibits PKC-δ over other isoforms (10 μM; Calbiochem). These concentrations have previously been shown to be effective in inhibiting the respective PKCs (17, 29). The GSK-3β inhibitor kenpaullone was purchased from Calbiochem. Wnt3a was purchased from R&D Systems. When performed, separation of nuclei of gingival fibroblasts was performed using the NE-PER and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit purchased from Pierce.

Western blot analysis.

Total cell layer proteins were extracted with 200 μl sample buffer containing 62.5 mM Tris, 10% glycerol, 2% SDS, and 5% β-mercaptoethanol. Samples were then boiled for 5 min and stored at −80°C. Protein concentrations were determined using the Nano Orange Kit (Molecular Probes). Samples were then subjected to 10% SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with antibodies specific for the protein of interest as we have previously described (5, 6). Membranes were subsequently stripped using Restore Western Stripping Solution and reprobed for β-actin for loading control, as required. Densitometric analyses were performed with a Bio-Rad VersaDoc Imaging System equipped with Quantity One software. Antibodies employed were goat polyclonal anti-CCN2/CTGF, IgG, and secondary donkey anti-goat IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody, and anti-lamin A/C mouse monoclonal antibody (sc-7292) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; phospho-AKT/PKB (S473), total AKT/PKB, phospho-GSK-3β (S9), total GSK-3β, total PKC-δ (catalog no. 2058) antibodies, and secondary anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibodies were from Cell Signaling; and rabbit monoclonal anti-phospho-SMAD3 (S424 + S425) antibody was obtained from Abcam (ab52903).

Transfection.

Transfections were performed using the Amaxa Nucleofector II (Lonza) electroporation device according to the manufacturer's instructions for small interfering (si)RNA and plasmid transfections. Briefly, 1 × 106 primary human gingival fibroblasts or adult human lung fibroblasts were suspended in 100 μl of Nucleofector solution and 1 or 2 μg of plasmid were then added and the solution was mixed gently. For gingival fibroblasts, the Nucleofector solution used was from the Nucleofector Kit for Primary Mammalian Fibroblasts (VPI-1002) with the V-13 or U-023 pulse setting. This condition resulted in a transfection efficiency of 87% without alterations in cell morphology or diminished viability as determined in optimization studies with a green fluorescent protein expression vector (Lonza). For lung fibroblasts, the Nucleofector Kit R was used (Lonza VCA-1001) with the U-03 pulse setting as optimized by Lonza and confirmed by us with the green fluorescent protein expression plasmid. After pulsing, cells were pooled as necessary to provide sufficient cells for each experiment and then immediately transferred into six-well plates containing prewarmed culture medium. After 12 h, the medium was changed to serum-free medium containing 0.1% BSA and allowed to grow for another 12 h after which the cells were treated as indicated.

For silencing studies, four siRNA sequences (Dharmacon), each targeting a different sequence of the respective target mRNA, were tested for optimal efficiency with a constant concentration of 215 pmol/100 μl per Amaxa transfection. At intervals following transfection (24, 48, and 72 h), silencing efficiency was tested by Western blot analysis for the respective targets. The optimal sequence was then used at different concentrations (215, 100, and 50 pmol/100 μl transfection) to determine the lowest concentration of siRNA needed for silencing. For PKC-δ (no. MQ-003524-01; Dharmacon) the sequences assayed in this manner were sequence #1: GAAAGAACGCUUCAACAUC, sequence #2: GUUGAUGUCUGUUCAGUAU, sequence #3: AGAAAUGCAUCGACAAGAU, and sequence #4: AGAAGAAGCCGACCAUGUA; and for GSK-3β (no. MQ-003010-03; Dharmacon) sequence #1: GAAGAAAGAUGAGGUCUAU, sequence #2: GAUGAGGUCUAUCUUAAUC, sequence #3: GGACCCAAAUGUCAAACUA, and sequence #4: GAAGUCAGCUAUACAGACA. For all of these experiments, the nontargeting siRNA UAAGGCUAUGAAGAGAUAC (no. D-001210-02; Dharmacon) was used as a negative control at equivalent respective concentrations. For individual experimental results presented here, the optimal sequence and minimum concentrations to fully inhibit expression of the target proteins were used following the same transfection procedure described above. The sequences and concentrations employed for knockdowns were, respectively, 215 pmol/100 μl of sequence #4 for PKC-δ; 215 pmol/100 μl of sequence #3 for GSK-3β, and 215 pmol/100 μl of the nontargeting control siRNA.

A constitutively active β-catenin (S33Y) expression vector was kindly provided by Dr. Bert Vogelstein (Howard Hughes Medical Institute and Sidney Kimmel Comprehensive Cancer Center, John Hopkins Oncology Center; Ref. 48), and the empty vector (pCLneo) was purchased from Promega. These vectors were propagated in Escherichia coli DH5α, and isolated using a plasmid purification kit (Qiagen) and employed for transient transfections as described above.

RESULTS

Inhibition of PI3K decreases the TGF-β1-induced expression of CCN2/CTGF in gingival fibroblasts independent of JNK.

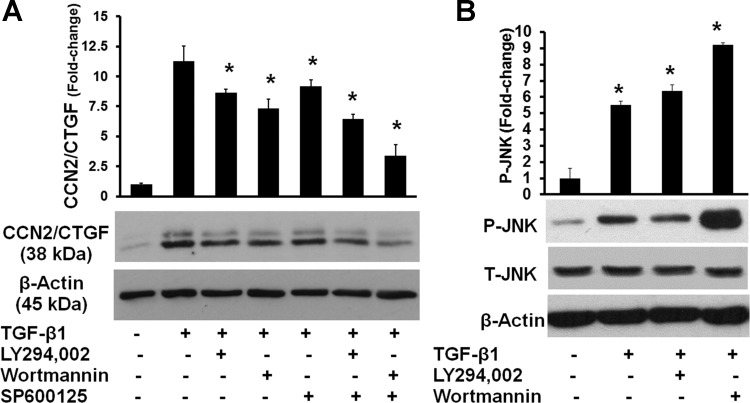

We have previously reported that TGF-β1-induced expression of CCN2/CTGF in human gingival fibroblasts is mediated primarily by JNK-MAP kinase activation and not ERK1/2 or p38 MAP kinases (5). In human fetal lung fibroblasts, the PI3K inhibitors wortmannin and LY294002 were each reported to inhibit TGF-β1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression mediated by downstream JNK MAP kinase activation (63). Hence, we first investigated the effects of PI3K inhibition on TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF expression and JNK activating phosphorylation in human gingival fibroblasts. Gingival fibroblast cultures were pretreated for 1 h with either 1 μM wortmannin or 50 μM LY294002 (PI3K inhibitors), 10 μM SP600125 (JNK inhibitor), or a PI3K inhibitor and the JNK inhibitor together as indicated in experimental procedures. TGF-β1 was then added and harvested after 6 h for Western blot analysis (5). The results show that PI3K inhibitor and JNK inhibitor treatments each result in downregulation of CCN2/CTGF expression, while the combination of both appears to have an additive effect (Fig. 1A). PI3K inhibitors do not reduce the activation of JNK in response to TGF-β1 (Fig. 1B). Data indicate that PI3K contributes to TGF-β1-induced upregulation of CCN2/CTGF but that JNK activation by TGF-β1 is not inhibited by PI3K in human gingival fibroblasts. Wortmannin does, however, inhibit AKT/PKB activating phosphorylation, suggesting that effects of PI3K can be mediated by the typical downstream PDK1/AKT activations in human gingival fibroblasts (data not shown).

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of phosphoinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) diminishes transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1)-induced connective tissue growth factor (CCN2/CTGF) expression independent of JNK in human gingival fibroblasts. A: preconfluent human gingival fibroblast cultures were serum starved and then pretreated with 10 μM JNK inhibitor (SP600125), 1 μM PI3K inhibitor wortmannin, or 50 μM LY294002 or both the JNK inhibitor and a PI3K inhibitor for 1 h followed by treatment with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 6 h. Cell lysates were then collected and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against CCN2/CTGF and β-actin for normalization. A: representative blot and densitometric analyses of 3 replicates from cells derived from 1 subject for CCN2/CTGF and data are means ± SD; n = 3; *P < 0.05. B: representative blot and densitometry analyses of 3 replicates from cells derived from 1 subject for phosphorylated JNK and data are means ± SD; n = 3; *P < 0.05. For both A and B, respective data are representative of experiments performed with cells from 3 different subjects and each experiment was performed with 3 replicates, all with the same outcomes.

Evaluation of PKC isoforms as effectors of PI3K.

We next investigated downstream effectors of the PI3K pathway in mediating the TGF-β1 response. Previous studies have shown that PKC mediates the profibrotic effect of TGF-β and expression of CCN2/CTGF in serosal fibroblasts (49). Moreover, PI3K is an important activator of PKCs in a variety of cell types (14, 41, 52, 59). Gingival fibroblast cultures were pretreated for 1 h with different PKC inhibitors or DMSO (vehicle) and treated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1, and cell lysates were analyzed as described above. Results show that 10 μM Bis I and 10 μM rottlerin each inhibit TGF-β1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression, while 0.1 μM Gö 6976, does not have any inhibitory effect (Table 1). These data suggest that Ca2+-dependent conventional PKCs are not involved in the induction of CCN2/CTGF by TGF-β1 and atypical PKCs, such as PKC-δ, could possibly participate in CCN2/CTGF regulation by TGF-β1.

Table 1.

Effect of protein kinase C inhibitors on TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF protein expression in human gingival fibroblasts

| Treatment | CCN2/CTGF Protein Level Compared with Vehicle-Only Control Cultures (Fold Change ± SD) |

|---|---|

| 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 | 17.80±0.85 |

| Bis I (10 μM) + 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 | 2.71±0.89* |

| Gö 6976 (0.1 μM) + 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 | 17.10±0.95 |

| Rottlerin (10 μM) + 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 | 2.32±1.01* |

Preconfluent human gingival fibroblast cultures were serum starved and then treated for 1 h with 10 μM bisindolylmaleimide I (Bis I), 0.1 μM Gö 6976, 10 μM rottlerin, or control (vehicle) as indicated, followed by addition of 5 ng/ml transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) or vehicle. After 6 h, cell lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against connective tissue growth factor (CCN2/CTGF) and subsequently with β-actin antibodies for normalization and quantitation as indicated in experimental procedures. Data are derived from cells from 9 independent cultures performed in 3 different experiments in cells derived from 1 subject (n = 9;

P < 0.05, Students t-test compared with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 treatment group).

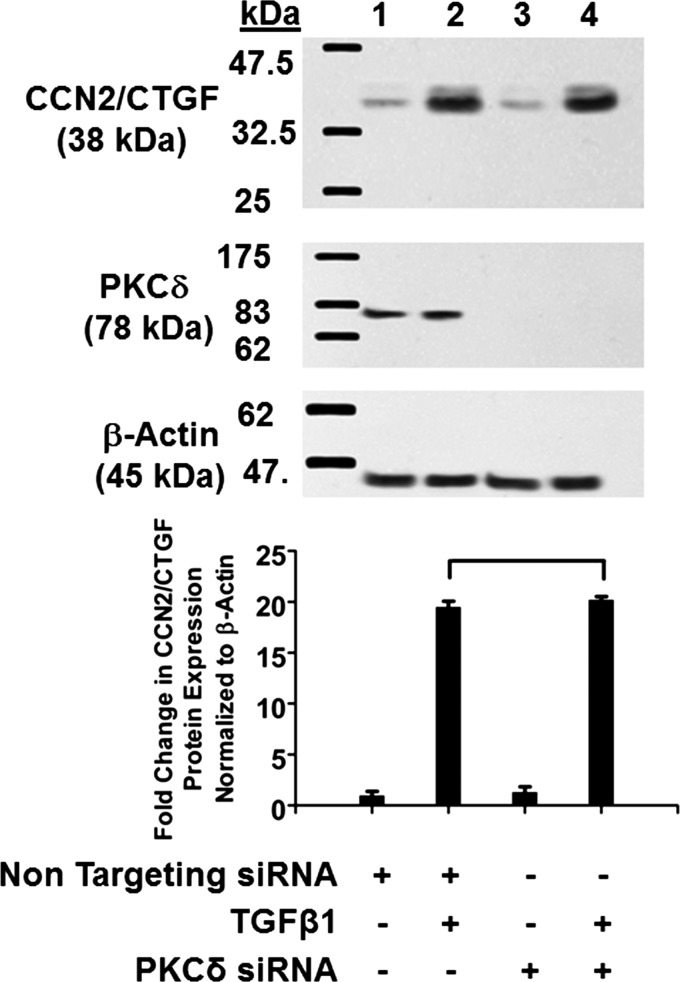

To directly address the role of PKC-δ, gingival fibroblasts were next transfected with siRNA targeting PKC-δ or nontargeting siRNA controls (see experimental procedures). Cells were then treated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 or vehicle, and cell lysates were subjected Western blot analysis. The results show that siRNA targeting PKC-δ did not reduce the ability of TGF-β1 to induce CCN2/CTGF expression (Fig. 2). Assay of the blots with anti-PKC-δ antibody confirmed that PKC-δ was efficiently silenced in cells transfected with PKC-δ siRNA compared with nontargeting siRNA (Fig. 2). These data indicate that PKC-δ is not involved in TGF-β1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression in gingival fibroblasts.

Fig. 2.

Protein kinase C (PKC)-δ is not involved in TGF-β1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression in human gingival fibroblasts. Human gingival fibroblast cultures were transfected with either nontargeting small interfering (si)RNA (lanes 1 and 2) or PKC-δ siRNA (lanes 3 and 4; 215 pmol each) for 48 h followed by stimulation with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 (lanes 2 and 4). After 6 h, cell lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against CCN2/CTGF. The same blot was stripped and probed with anti-PKC-δ antibody to confirm knockdown. Top: representative blots of experiments performed twice for CCN2/CTGF (top), PKC-δ (middle), and β-actin (bottom) all from the same gel. Bottom: densitometric analysis of blots for mean CCN2/CTGF band intensity normalized to β-actin ± SD from 6 independent cultures derived from 1 subject (n = 6; bracket shows P > 0.05).

GSK-3β and TGF-β1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression in gingival fibroblasts.

While challenge of gingival fibroblasts with the PKC inhibitors Bis I and rottlerin inhibited TGF-β1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression in gingival fibroblasts, silencing studies did not yield similar results (Fig. 2). Concentrations of Bis I and rottlerin employed can also inhibit GSK-3β (2, 17). Because GSK-3β is a known target of the PI3K/AKT pathway (9), we hypothesized that active GSK-3β could in some way mediate TGF-β1 regulation of CCN2/CTGF. Gingival fibroblast cultures were pretreated with the GSK-3β inhibitor kenpaullone or DMSO (vehicle) for 1 h (17), followed by TGF-β1 and analyzed. Results show a potent downregulation of TGF-β1-mediated CCN2/CTGF expression by kenpaullone (Table 2). Data suggest that GSK-3β activity is important in mediating TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF levels in human gingival fibroblasts.

Table 2.

Effect of GSK-3β inhibitor on TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF protein levels in human gingival fibroblast cell cultures

| Treatment | CCN2/CTGF Protein Level Compared with Vehicle-Only Control Cultures (Fold Change ± SD) |

|---|---|

| Subject 1 | |

| 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 | 20.50±2.71 |

| Kenpaullone (10 μM) + 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 | 2.28±1.13* |

| Subject 2 | |

| 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 | 40.1±0.06 |

| Kenpaullone (10 μM) + 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 | 17.8±0.12* |

Preconfluent human gingival fibroblast cultures were grown in serum-free medium for 12 h and then pretreated for 1 h with 10 μM kenpaullone or vehicle, followed by addition of 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 or vehicle. GSK-3β, glycogen synthase kinase-3β. After 6 h, cell lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against CCN2/CTGF and β-actin for normalization by densitometry as described in experimental procedures. Data are derived from cells from 9 independent cultures derived from subject 1 (n = 9) performed in 3 independent experiments and 3 independent cultures from subject 2 (n = 3);

P < 0.05, Students t-test compared with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1-treated group.

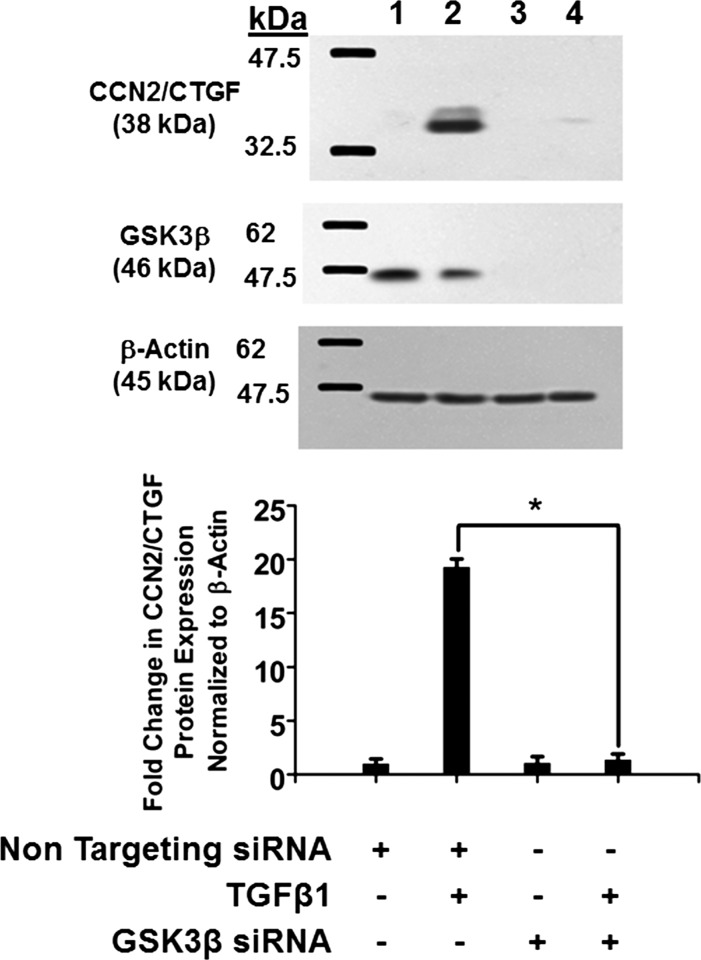

To directly confirm these findings, we next performed gene knockdown studies of GSK-3β in human gingival fibroblasts using siRNA technology described in experimental procedures. Silencing GSK-3β completely blocks the ability of TGF-β1 to induce CCN2/CTGF expression (Fig. 3). GSK-3β silencing was confirmed by Western blotting with anti-GSK-3β antibodies (Fig. 3). Taken together with pharmacologic inhibition of GSK-3β (Table 2), these data strongly suggest that active GSK-3β significantly contributes to TGF-β1 induction of CCN2/CTGF expression in human gingival fibroblasts.

Fig. 3.

Glycogen synthase kinase-3β (GSK-3β) mediates TGF-β1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression in human gingival fibroblasts. Human gingival fibroblast cultures were transfected with either GSK-3β siRNA or nontargeting siRNA (215 pmol) for 48 h before stimulation with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. After 6 h, cell lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against CCN2/CTGF. The same blot was stripped and probed with anti-GSK-3β antibody to confirm knockdown. Top: representative blot of experiments performed twice. Bottom: densitometric analysis of blots depicting mean band intensity normalized to β-actin ± SD of six independent cultures derived from 1 subject (n = 6, *P < 0.05, Students t-test). Lane 1, nontargeting siRNA; lane 2, nontargeting siRNA plus TGF-β1; lane 3, GSK-3β siRNA; lane 4, GSK-3β siRNA plus TGF-β1.

Wnt3a inhibits TGF-β1-induced expression of CCN2/CTGF in human gingival fibroblasts.

GSK-3β has a vital role in canonical Wnt signaling. In the absence of Wnt ligands, GSK-3β is constitutively active and phosphorylates β-catenin, targeting it for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation (51). In the presence of Wnt ligands, GSK-3β activity is inhibited and β-catenin escapes degradation (45). Hence, the inhibition of GSK-3β kinase activity is an essential component of an active canonical Wnt/β-catenin pathway. We utilized Wnt3a stimulation as an independent means to inhibit GSK-3β in gingival fibroblasts and lung fibroblasts to test its effects on TGF-β1-mediated CCN2/CTGF expression.

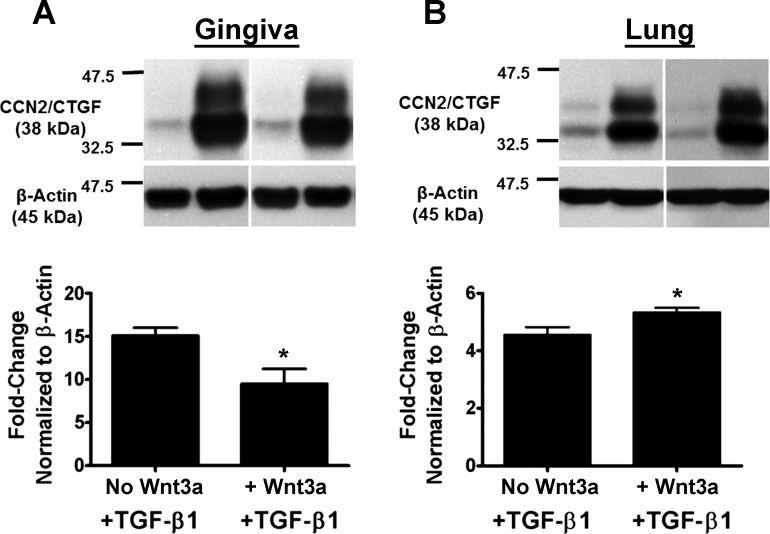

Gingival fibroblast and human lung fibroblast cultures were pretreated with or without 150 ng/ml Wnt3a for 1 h followed by treatment with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 6 h. Cell lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot for CCN2/CTGF protein levels. Results show that Wnt3a treatment inhibits TGF-β1-mediated CCN2/CTGF expression by 35% in gingival fibroblasts (Fig. 4A), consistent with data obtained with pharmacologic GSK-3β inhibitors and silencing (Table 2 and Fig. 3). This observation is in sharp contrast to results obtained in human adult lung cells in which Wnt3a does not downregulate CCN2/CTGF but modestly upregulates TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF levels (Fig. 4B). Data in lung cells (Fig. 4B) are consistent with published studies performed in a variety of other non-oral mesenchymal cells and in tissues in which canonical Wnt signaling increases upregulates CCN2/CTGF and fibrosis (1, 4, 12, 19, 67).

Fig. 4.

Wnt3a attenuates TGFβ1-induced expression of CCN2/CTGF in human gingival fibroblasts but upregulates CCN2/CTGF in lung fibroblasts. Preconfluent human gingival fibroblast cultures (A) or adult human primary lung cells (B) were grown in serum-free medium for 12 h and then pretreated for 1 h with 150 ng/ml Wnt3a followed by addition of 5 ng/ml TGFβ1. After 6 h, cell lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against CCN2/CTGF. Top: representative blot from 1 subject of experiments performed with 3 independent transfections in gingival fibroblasts and twice with adult human primary fibroblasts. Bottom: densitometric analysis of blots depicting mean band intensity normalized to β-actin ± SD of the 3 independent transfections 1 subject each (n = 3; *P < 0.05, Students t-test). These experiments were performed a total of 3 times from an additional 2 subjects with the same outcome of Wnt3a inhibition of TGF-β stimulated CCN2/CTGF levels in gingival fibroblasts, and a modest stimulation by Wnt3a in lung cells. Lanes shown in each panel are from the same experiment and gel.

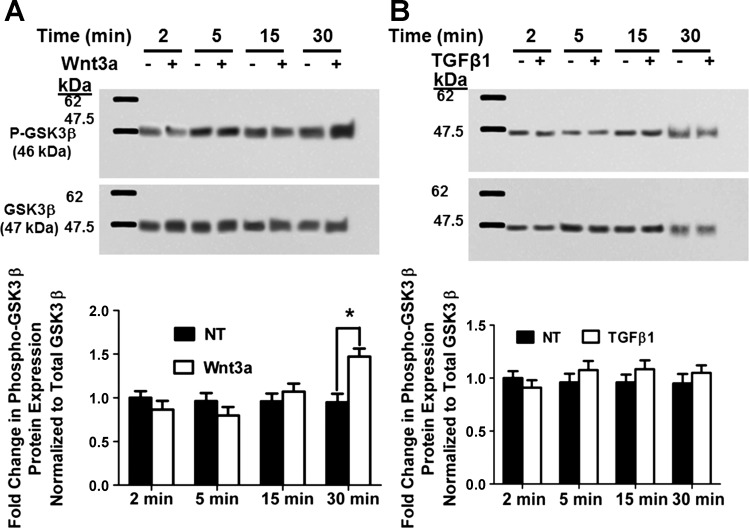

Regulation of GSK-3β inhibitory phosphorylation by Wnt3a and TGF-β1.

GSK-3β activity is inhibited by phosphorylation at serine 9. Blocking or reducing phosphorylation at serine 9 would, therefore, be expected to increase GSK-3β activity. Thus we next investigated whether TGF-β1 could itself enhance GSK-3β activity by inhibiting the basal level of phosphorylation at serine 9 in gingival fibroblasts, thereby increasing GSK-3β activity leading to increased CCN2/CTGF levels. To test this notion, preconfluent gingival fibroblast cultures were grown in serum free medium for 12 h. Cultures were treated with or without 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 or 150 ng/ml Wnt3a for different time points up to 30 min. Cells were subsequently subjected to Western blot analysis for GSK-3β phosphorylated at serine 9. The results show that there is significantly increased inhibitory phosphorylation at serine 9 after 30 min of Wnt3a treatment as expected (Fig. 5A). However, no decrease in serine 9 inhibitory phosphorylation in response to TGF-β1 was found in human gingival fibroblasts (Fig. 5B). Data indicate that TGF-β1 does not reduce the inhibitory phosphorylation of GSK-3β at serine 9 and hence does not promote CCN2/CTGF expression by this mechanism in gingival fibroblasts. Wnt3a-induced phosphorylation of GSK-3β serine 9, however, further supports the finding that in gingival fibroblasts, GSK-3β inhibition attenuates, rather than stimulates, TGF-β1 upregulation of CCN2/CTGF levels.

Fig. 5.

Wnt3a increases GSK-3β serine 9 phosphorylation at 30 min in human gingival fibroblasts (A), whereas TGF-β1 does not reduce the degree of GSK-3β phosphorylation on serine 9 (B). Preconfluent human gingival fibroblast cultures were serum-starved and then were treated with or without 150 ng/ml Wnt3a (A) or 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 (B) for different time intervals. Cell lysates were then collected for Western blot analysis of GSK-3β phosphorylation at serine 9. Top: representative blots of experiments performed 3 times. Bottom: densitometric analysis of blots depicting mean band intensity normalized to β-actin ± SD from 9 independent cultures derived from 1 subject (n = 9; *P < 0.05, Students t-test).

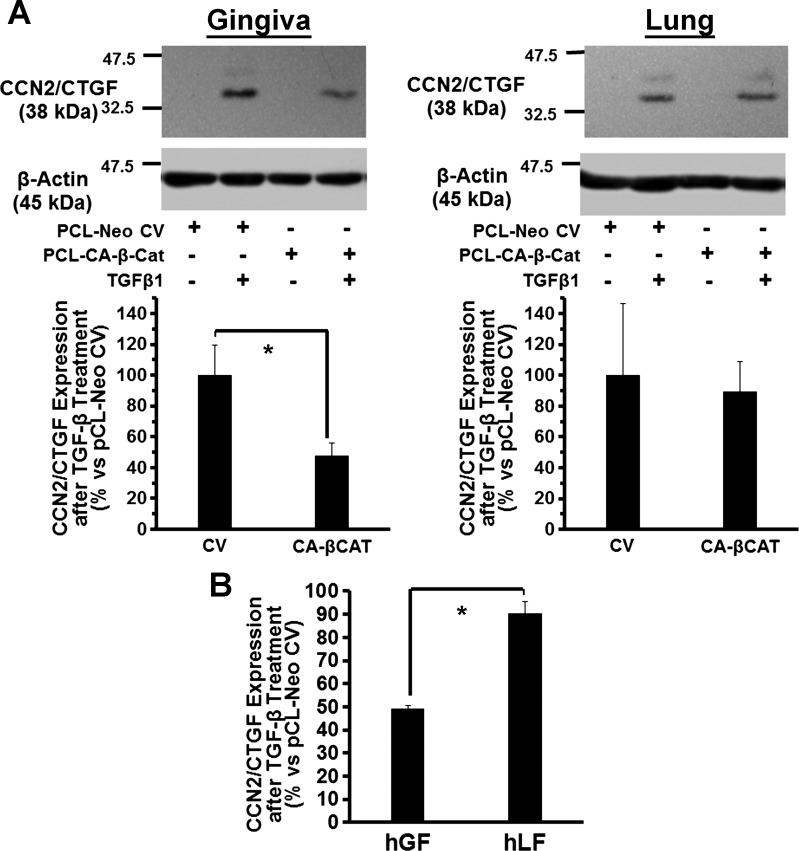

Constitutively active β-catenin (S33Y) inhibits TGF-β1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression in adult human gingival fibroblasts in contrast to lung cells.

Wnt3a leads to GSK-3β inhibition by phosphorylation at serine 9 that ultimately contributes to active β-catenin accumulation and activation of TCF/LEF dependent transcription (46, 57, 66). We next tested whether β-catenin could in some way mediate the Wnt3a/GSK-3β inhibitory effects on TGF-β1 signaling in human gingival fibroblasts. An expression plasmid for constitutively active β-catenin (S33Y) was transfected into human gingival fibroblasts, and empty vector (pCl-neo) served as a control (see experimental procedures). After transfection (36 h), cells were serum-starved for 12 h and then treated with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 or vehicle, and CCN2/CTGF levels were assessed. Data (Fig. 6A) indicate that gingival cells transfected with constitutively active β-catenin (S33Y) showed 50% attenuation of TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF expression; no significant effects on TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF expression were seen in lung cells. Figure 6B shows data combined from three separate gingival fibroblast donors compared with lung fibroblasts. Data further support the notion that β-catenin mediates Wnt3a inhibition of TGF-β1 stimulated CCN2/CTGF expression in gingival fibroblasts.

Fig. 6.

Constitutively active β-catenin (S33Y) inhibits TGF-β1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression in adult human gingival fibroblasts but not in human adult lung cells. A: human gingival fibroblast cultures or human adult lung fibroblast cultures were transfected by electroporation with either 1 μg of a constitutively active mutant plasmid expressing β-catenin (S33Y) or empty control vector (pCl-neo) for 48 h before stimulation with 5 ng/ml TGF-β1. After 6 h, cell lysates were collected and analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against CCN2/CTGF. Top: 1 representative blot each of 3 experiments performed with cells from 3 different gingival tissue donors and 3 experiments performed with primary lung fibroblasts obtained commercially, while the graphs show densitometry data from cells derived from 1 gingival tissue donor performed with 3 replicates (means ± SD; *P < 0.05). B: percentage of CCN2/CTGF expression in constitutively active β-catenin expressing cells compared with empty vector in gingiva and lung cells in data from all 3 subjects combined expressed as means ± SE (n = 3; *P < 0.05, Students t-test), showing that active β-catenin inhibits CCN2/CTGF expression only in gingival fibroblasts and not lung fibroblasts.

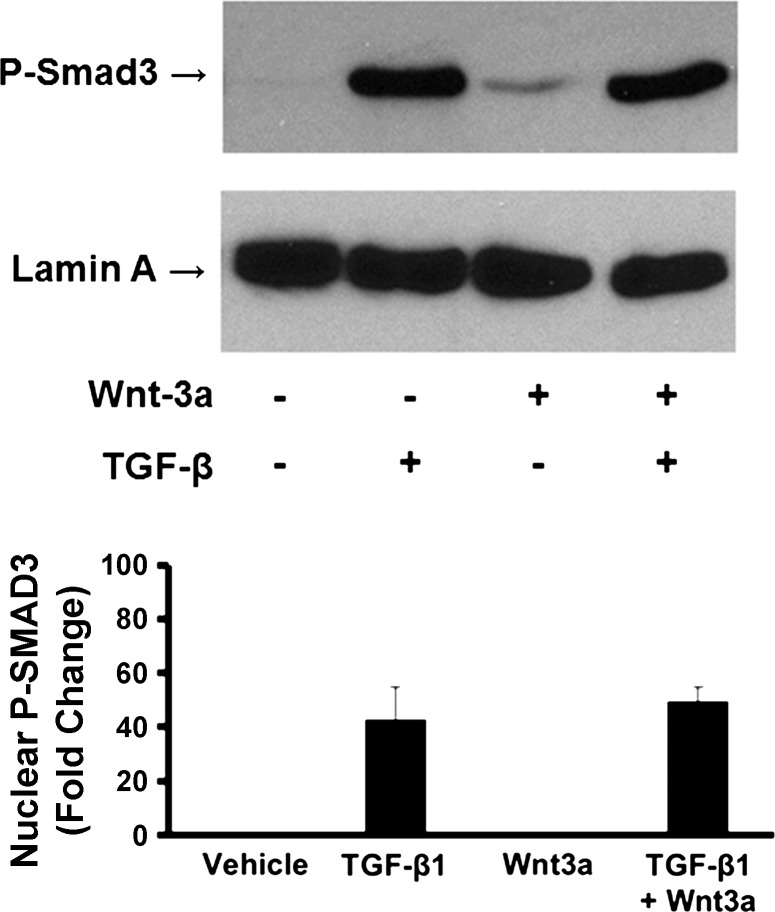

We next asked whether Wnt3a could inhibit SMAD3 activating phosphorylations as an index of global attenuation of TGF-β signaling. This was accomplished by treating cells with 150 ng/ml Wnt3a for 1 h, followed by 5 ng/ml TGF-β1 for 30 min and isolation and extraction of cell nuclei. Extracts were then subjected to Western blots for phosphorylated SMAD3 with the nuclear protein lamin A employed as the loading control. Data in Fig. 7 show that Wnt3a did not regulate the relative amount of nuclear phosphorylated SMAD3 in human gingival fibroblasts. This finding is consistent with the notion that tissue-specific regulations of TGF-β signaling are mediated by pathways which are independent of SMAD activation (5, 24).

Fig. 7.

Wnt3a has no effect on phosphorylation of Smad3 in n = 3, -induced expression of CCN2/CTGF in human gingival fibroblasts. Preconfluent primary human gingival fibroblast cultures were grown in serum free medium for 12 h and then pretreated for 1 h with 150 ng/ml Wnt3a followed by addition of 5 ng/ml n = 3,. After 30 min, nuclei were collected, extracted, and then analyzed by Western blot using antibodies against phospho-SMAD3 and lamin A. One representative blot is shown from 1 experiment performed with 3 replicates. Graph shows the effect of Wnt3a on TGF-β1-stimulated levels of P-Smad3 normalized to lamin A. Data are expressed as fold change of P-Smad3 of TGFβ1 stimulated cells to vehicle control ± SD; n = 3; *P = 0.34, Students t-test. This experiment was repeated with cells from a 2nd subject with the same outcome.

DISCUSSION

A goal of TGF-β1 signal transduction studies in human gingival fibroblasts is to understand tissue-specific signaling pathways that have the potential to serve as therapeutic targets in the treatment or prevention of human oral fibrotic conditions including gingival overgrowth. Because PI3K and downstream effectors have been associated with fibrosis in other tissues, here we chose to investigate roles for PI3K-, PKC- and GSK-3β-mediated pathways in the regulation of CCN2/CTGF in human gingival fibroblasts compared with human lung fibroblasts.

PKC isoforms regulate events leading to the deposition of collagen and regulate fibrosis in various tissues including cardiac, renal, and pulmonary tissues (13, 23, 30, 62). Our data that employed pharmacological and gene-specific knockdown technologies indicate that PKCs do not appear to play any role in mediating the upregulation of CCN2/CTGF in human gingival fibroblasts by contrast to reports in fibroblasts from other tissues (7, 12, 39). Most important, our data demonstrate unique aspects of TGF-β1-induced cell signaling and PI3K effectors in the control of CCN2/CTGF expression by gingival fibroblasts.

GSK-3β exerts a broad regulatory influence on cellular functions such as cell metabolism, protein synthesis, cell proliferation, cell differentiation, cell motility, and apoptosis (20, 21, 23, 65). The use of pharmacological inhibitors selective for GSK-3β, as well as gene-specific knockdown of GSK-3β using siRNA, resulted in inhibition of TGF-β1-mediated effects in gingival fibroblasts and suggest that the activity of GSK-3β contributes to the expression of CCN2/CTGF induced by TGF-β1. We employed Wnt3a as an independent inhibitor of GSK-3β activity that similarly inhibited TGF-β1-mediated CCN2/CTGF expression in gingival fibroblasts. These effects of GSK-3β inhibition are opposite to findings in NIH3T3 fibroblasts, muscle cells, and mesenchymal stem cells where activation of the Wnt pathway leads to the increased expression of CCN2/CTGF (7, 12, 39). Consistent with these studies, but in sharp contrast, our data performed with gingival fibroblasts under the same conditions show that treatment of adult human lung fibroblasts with Wnt3a resulted in a modest upregulation of CCN2/CTGF. In combination with TGF-β1, Wnt3a has a positive effect on CCN2/CTGF expression in lung fibroblasts, rather than an inhibitory effect seen in adult human gingival fibroblasts. This emphasizes that gingival fibroblasts respond differently to stimuli compared with other tissue fibroblasts.

GSK-3β is normally constitutively active in cells and is primarily regulated through inhibitory phosphorylation at serine 9 (16, 20). If active GSK-3β is vital for the regulation of CCN2/CTGF by TGF-β1, it is possible that TGF-β1 itself could further activate basal GSK-3β activity by decreasing serine 9 phosphorylation. While Wnt3a treatment increased GSK-3β phosphorylation, TGF-β1 did not decrease GSK-3β phosphorylation at serine 9.

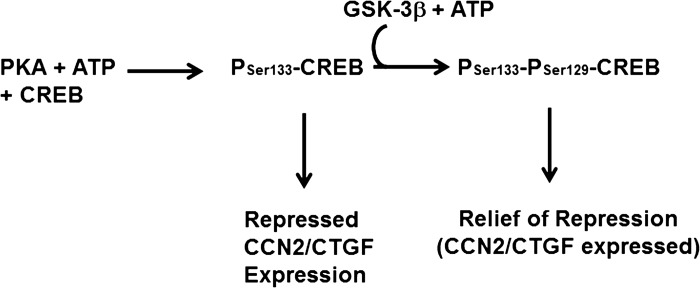

GSK-3β activity is required for TGF-β1-mediated CCN2/CTGF in human gingival fibroblasts. Constitutively active β-catenin inhibits TGF-β1-stimulated CCN2/CTGF levels in gingival fibroblasts (Fig. 6), indicating that the effects of Wnt3a on CCN2/CTGF are dependent on GSK-3β in gingival fibroblasts. GSK-3β typically catalyzes inhibitory phosphorylations (50, 65). One target of GSK-3β is the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB; Ref. 60). GSK-3β phosphorylation of CREB requires previous activating phosphorylation of CREB on Ser133 by the cAMP-dependent PKA. The effect of secondary GSK-3β phosphorylation of CREB on Ser129 is to inhibit CREB binding to cis-acting elements in promoter regions of target genes, thereby preventing its ability to activate transcription (8, 32). We have previously shown that the direct activation of cAMP/PKA pathway by forskolin that activates CREB results in inhibition of CCN2/CTGF expression in lung and kidney fibroblasts (5), while this effect is weak in gingival fibroblasts. Interestingly, the cAMP response to forskolin and prostaglandins is very weak in gingival fibroblasts compared with lung cells (5). Therefore, we propose a working model in which different ratios of the levels of GSK-3β to PKA can provide a mechanism by which inhibition of GSK-3β could have the observed differential effects in gingival fibroblasts compared with lung (Fig. 8). Assuming that active CREB represses CCN2/CTGF transcription and active GSK-3β relieves this repression, a high GSK-3β-to-PKA ratio would result in potential decreased CCN2/CTGF levels if GSK-3β phosphorylation were inhibited (gingiva, Fig. 3), while inhibition of GSK-3β in the context of high PKA/GSK-3b would have little consequence for CCN2/CTGF expression. In this model, increased CCN2/CTGF levels seen in Wnt3a-stimulated lung cells (Fig. 4 and Refs. 7, 12, 39) would be related to other transcriptional effects of β-catenin. Generally supporting this model is our observation that although the cAMP/PKA pathway in gingival fibroblasts is muted compared with lung cells (5), TGF-β1 stimulates a transient phosphorylation of Ser133 of CREB (data not shown). Clearly, at this time, transcriptional repressors other than CREB, which could be inactivated by inhibitory phosphorylations by GSK-3β, must also be considered in the context of tissue-specific regulation of CCN2/CTGF. This and similar models clearly require an analysis of transcriptional regulation of CCN2/CTGF in gingival and other tissue fibroblasts.

Fig. 8.

Model for GSK-3β activity for optimal expression of CCN2/CTGF in human gingival fibroblasts. The model proposes that active CREB(Ser133) represses CCN2/CTGF expression, while subsequent GSK-3β phosphorylation to CREB(Ser133,Ser129) releases CREB-dependent repression of CCN2/CTGF expression. Thus inhibition of GSK-3β would reduce CCN2/CTGF expression, as is observed in human gingival fibroblast cultures.

Our primary objective was to study intracellular signaling pathways controlling TGF-β1 regulation of CCN2/CTGF in gingival fibroblasts with an aim to identify unique pathways that drive drug-induced gingival overgrowth lesions where both TGF-β1 and CCN2/CTGF are involved. Here we have identified a novel role for active GSK-3β in permitting TGF-β1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression in gingival fibroblasts. The potential importance of GSK-3β in the pathogenesis of different diseases has led to much interest in identifying selective pharmacologic inhibitors of GSK-3β that may be of therapeutic usefulness (11, 58). Certain derivatives of paullones (37), maleimide (15), lithium (58), and indirubin (36) have been identified as potent and selective inhibitors of GSK-3β. Hence, it appears that important new therapeutic agents may be available and could be considered as potential therapeutic or preventative agents of oral fibrosis, either alone or in combination with other agents (5, 6). This finding adds to our previous studies pointing to forskolin and statins as potential therapeutic agents to address oral fibrosis that were similarly based on analyses of cell signaling pathways in gingival fibroblasts (5, 6). Although systemic use of GSK-3β inhibitors to treat neurodegenerative diseases, bipolar disorders and inflammation are being considered, concerns regarding negative effects on cardiac tissues and promotion of tumors may limit these uses (65). Oral tissues, however, are unique in that they are easily accessed, and one can envision formulations in which inhibitors could be applied locally without systemic complications.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research Grants R01-DE-11004 (to P. C. Trackman) and K08-DE-016609 (to S. A. Black) and by the Faculty of Dentistry, King Abdulaziz University, Ministry of Higher Education, Saudi Arabia (to M. Bahammam and M. A. Assaggaf).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: M.B., S.A.B., S.S.S., M.A.A., and M.F. performed experiments; M.B., M.F., and P.C.T. prepared figures; M.B., S.A.B., S.S.S., M.A.A., M.F., and P.C.T. approved final version of manuscript; S.A.B. and P.C.T. analyzed data; S.A.B. and P.C.T. interpreted results of experiments; P.C.T. conception and design of research; P.C.T. drafted manuscript; P.C.T. edited and revised manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Present address of M. Bahammam: King Abdulaziz University, Faculty of Dentistry, Department of Oral and Basic Clinical Sciences, P. O. Box 80209, Jeddah 21589, Saudi Arabia.

REFERENCES

- 1. Akhmetshina A, Palumbo K, Dees C, Bergmann C, Venalis P, Zerr P, Horn A, Kireva T, Beyer C, Zwerina J, Schneider H, Sadowski A, Riener MO, MacDougald OA, Distler O, Schett G, Distler JH. Activation of canonical Wnt signalling is required for TGF-beta-mediated fibrosis. Nat Commun 3: 735, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bain J, McLauchlan H, Elliott M, Cohen P. The specificities of protein kinase inhibitors: an update. Biochem J 371: 199–204, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Bakin AV, Tomlinson AK, Bhowmick NA, Moses HL, Arteaga CL. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase function is required for transforming growth factor beta-mediated epithelial to mesenchymal transition and cell migration. J Biol Chem 275: 36803–36810, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Beyer C, Schramm A, Akhmetshina A, Dees C, Kireva T, Gelse K, Sonnylal S, de Crombrugghe B, Taketo MM, Distler O, Schett G, Distler JH. β-Catenin is a central mediator of pro-fibrotic Wnt signaling in systemic sclerosis. Ann Rheum Dis 71: 761–767, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Black SA, Jr, Palamakumbura AH, Stan M, Trackman PC. Tissue-specific mechanisms for CCN2/CTGF persistence in fibrotic gingiva: interactions between cAMP and MAPK signaling pathways, and prostaglandin E2-EP3 receptor mediated activation of the c-JUN N-terminal kinase. J Biol Chem 282: 15416–15429, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Black SA, Jr, Trackman PC. Transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGFbeta1) stimulates connective tissue growth factor (CCN2/CTGF) expression in human gingival fibroblasts through a RhoA-independent, Rac1/Cdc42-dependent mechanism: statins with forskolin block TGFbeta1-induced CCN2/CTGF expression. J Biol Chem 283: 10835–10847, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brack AS, Conboy MJ, Roy S, Lee M, Kuo CJ, Keller C, Rando TA. Increased Wnt signaling during aging alters muscle stem cell fate and increases fibrosis. Science 317: 807–810, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bullock BP, Habener JF. Phosphorylation of the cAMP response element binding protein CREB by cAMP-dependent protein kinase A and glycogen synthase kinase-3 alters DNA-binding affinity, conformation, and increases net charge. Biochemistry 37: 3795–3809, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Cantley LC. The phosphoinositide 3-kinase pathway. Science 296: 1655–1657, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Casamassimo PS. Relationships between oral and systemic health. Pediatr Clin North Am 47: 1149–1157, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Castro V, Murillo R, Klaas CA, Meunier C, Mora G, Pahl HL, Merfort I. Inhibition of the transcription factor NF-kappa B by sesquiterpene lactones from Podachaenium eminens. Planta Med 66: 591–595, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen S, McLean S, Carter DE, Leask A. The gene expression profile induced by Wnt 3a in NIH 3T3 fibroblasts. J Cell Commun Signal 1: 175–183, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chintalgattu V, Katwa LC. Role of protein kinase Cdelta in endothelin-induced type I collagen expression in cardiac myofibroblasts isolated from the site of myocardial infarction. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 311: 691–699, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chou MM, Hou W, Johnson J, Graham LK, Lee MH, Chen CS, Newton AC, Schaffhausen BS, Toker A. Regulation of protein kinase C zeta by PI 3-kinase and PDK-1. Curr Biol 8: 1069–1077, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coghlan MP, Culbert AA, Cross DA, Corcoran SL, Yates JW, Pearce NJ, Rausch OL, Murphy GJ, Carter PS, Roxbee Cox L, Mills D, Brown MJ, Haigh D, Ward RW, Smith DG, Murray KJ, Reith AD, Holder JC. Selective small molecule inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3 modulate glycogen metabolism and gene transcription. Chem Biol 7: 793–803, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cross DA, Alessi DR, Cohen P, Andjelkovich M, Hemmings BA. Inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase-3 by insulin mediated by protein kinase B. Nature 378: 785–789, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Davies SP, Reddy H, Caivano M, Cohen P. Specificity and mechanism of action of some commonly used protein kinase inhibitors. Biochem J 351: 95–105, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature 425: 577–584, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Distler A, Deloch L, Huang J, Dees C, Lin NY, Palumbo-Zerr K, Beyer C, Weidemann A, Distler O, Schett G, Distler JH. Inactivation of tankyrases reduces experimental fibrosis by inhibiting canonical Wnt signalling. Ann Rheum Dis 2012. November 12 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Doble BW, Woodgett JR. GSK-3: tricks of the trade for a multi-tasking kinase. J Cell Sci 116: 1175–1186, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Frame S, Cohen P. GSK3 takes centre stage more than 20 years after its discovery. Biochem J 359: 1–16, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ghosh Choudhury G, Abboud HE. Tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent PI 3 kinase/Akt signal transduction regulates TGFbeta-induced fibronectin expression in mesangial cells. Cell Signal 16: 31–41, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Grimes CA, Jope RS. The multifaceted roles of glycogen synthase kinase 3beta in cellular signaling. Prog Neurobiol 65: 391–426, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Hartsough MT, Mulder KM. Transforming growth factor-beta signaling in epithelial cells. Pharmacol Therap 75: 21–41, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hassell TM, Hefti AF. Drug-induced gingival overgrowth: old problem, new problem. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 2: 103–137, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Heng EC, Huang Y, Black SA, Jr, Trackman PC. CCN2, connective tissue growth factor, stimulates collagen deposition by gingival fibroblasts via module 3 and alpha6- and beta1 integrins. J Cell Biochem 98: 409–420, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Holmes A, Abraham DJ, Sa S, Shiwen X, Black CM, Leask A. CTGF and SMADs, maintenance of scleroderma phenotype is independent of SMAD signaling. J Biol Chem 276: 10594–10601, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hong HH, Uzel MI, Duan C, Sheff MC, Trackman PC. Regulation of lysyl oxidase, collagen, and connective tissue growth factor by TGF-beta1 and detection in human gingiva. Lab Invest 79: 1655–1667, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hsia E, Richardson TP, Nugent MA. Nuclear localization of basic fibroblast growth factor is mediated by heparan sulfate proteoglycans through protein kinase C signaling. J Cell Biochem 88: 1214–1225, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hua H, Goldberg HJ, Fantus IG, Whiteside CI. High glucose-enhanced mesangial cell extracellular signal-regulated protein kinase activation and alpha1(IV) collagen expression in response to endothelin-1: role of specific protein kinase C isozymes. Diabetes 50: 2376–2383, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Janssens K, ten Dijke P, Janssens S, Van Hul W. Transforming growth factor-beta1 to the bone. Endocr Rev 26: 743–774, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Johannessen M, Moens U. Multisite phosphorylation of the cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB) by a diversity of protein kinases. Front Biosci 12: 1814–1832, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kantarci A, Black SA, Xydas CE, Murawel P, Uchida Y, Yucekal-Tuncer B, Atilla G, Emingil G, Uzel MI, Lee A, Firatli E, Sheff M, Hasturk H, Van Dyke TE, Trackman PC. Epithelial and connective tissue cell CTGF/CCN2 expression in gingival fibrosis. J Pathol 210: 59–66, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kantarci A, Cebeci I, Tuncer O, Carin M, Firatli E. Clinical effects of periodontal therapy on the severity of cyclosporin A-induced gingival hyperplasia. J Periodontol 70: 587–593, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Leask A, Abraham DJ, Finlay DR, Holmes A, Pennington D, Shi-Wen X, Chen Y, Venstrom K, Dou X, Ponticos M, Black C, Bernabeu C, Jackman JK, Findell PR, Connolly MK. Dysregulation of transforming growth factor beta signaling in scleroderma: overexpression of endoglin in cutaneous scleroderma fibroblasts. Arthritis Rheum 46: 1857–1865, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Leclerc S, Garnier M, Hoessel R, Marko D, Bibb JA, Snyder GL, Greengard P, Biernat J, Wu YZ, Mandelkow EM, Eisenbrand G, Meijer L. Indirubins inhibit glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta and CDK5/p25, two protein kinases involved in abnormal tau phosphorylation in Alzheimer's disease. A property common to most cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors? J Biol Chem 276: 251–260, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leost M, Schultz C, Link A, Wu YZ, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Bibb JA, Snyder GL, Greengard P, Zaharevitz DW, Gussio R, Senderowicz AM, Sausville EA, Kunick C, Meijer L. Paullones are potent inhibitors of glycogen synthase kinase-3beta and cyclin-dependent kinase 5/p25. Eur J Biochem 267: 5983–5994, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li X, Kolltveit KM, Tronstad L, Olsen I. Systemic diseases caused by oral infection. Clin Microbiol Rev 13: 547–558, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Luo Q, Kang Q, Si W, Jiang W, Park JK, Peng Y, Li X, Luu HH, Luo J, Montag AG, Haydon RC, He TC. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) is regulated by Wnt and bone morphogenetic proteins signaling in osteoblast differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells. J Biol Chem 279: 55958–55968, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Mahimainathan L, Das F, Venkatesan B, Choudhury GG. Mesangial cell hypertrophy by high glucose is mediated by downregulation of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Diabetes 55: 2115–2125, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Maines MD. Biliverdin reductase: PKC interaction at the cross-talk of MAPK and PI3K signaling pathways. Antioxid Redox Signal 9: 2187–2195, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Marshall DE, Gower DB, Silver M, Fowden A, Houghton E. Cannulation in situ of equine umbilicus. Identification by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS) of differences in steroid content between arterial and venous supplies to and from the placental surface. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 68: 219–228, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Marshall RI, Bartold PM. A clinical review of drug-induced gingival overgrowths. Aust Dent J 44: 219–232, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meraw SJ, Sheridan PJ. Medically induced gingival hyperplasia. Mayo Clin Proc 73: 1196–1199, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Miller JR, Hocking AM, Brown JD, Moon RT. Mechanism and function of signal transduction by the Wnt/beta-catenin and Wnt/Ca2+ pathways. Oncogene 18: 7860–7872, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Molenaar M, van de Wetering M, Oosterwegel M, Peterson-Maduro J, Godsave S, Korinek V, Roose J, Destree O, Clevers H. XTcf-3 transcription factor mediates beta-catenin-induced axis formation in Xenopus embryos. Cell 86: 391–399, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mori T, Kawara S, Shinozaki M, Hayashi N, Kakinuma T, Igarashi A, Takigawa M, Nakanishi T, Takehara K. Role and interaction of connective tissue growth factor with transforming growth factor-beta in persistent fibrosis: a mouse fibrosis model. J Cell Physiol 181: 153–159, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Morin PJ, Sparks AB, Korinek V, Barker N, Clevers H, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Activation of beta-catenin-Tcf signaling in colon cancer by mutations in beta-catenin or APC. Science 275: 1787–1790, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Mulsow JJ, Watson RW, Fitzpatrick JM, O'Connell PR. Transforming growth factor-beta promotes pro-fibrotic behavior by serosal fibroblasts via PKC and ERK1/2 mitogen activated protein kinase cell signaling. Ann Surg 242: 880–887, discussion 887–889, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Nikolakaki E, Coffer PJ, Hemelsoet R, Woodgett JR, Defize LH. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 phosphorylates Jun family members in vitro and negatively regulates their transactivating potential in intact cells. Oncogene 8: 833–840, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Orford K, Crockett C, Jensen JP, Weissman AM, Byers SW. Serine phosphorylation-regulated ubiquitination and degradation of beta-catenin. J Biol Chem 272: 24735–24738, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Peterson RT, Schreiber SL. Kinase phosphorylation: keeping it all in the family. Curr Biol 9: R521–524, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pilatti GL, Sampaio JE. The influence of chlorhexidine on the severity of cyclosporin A-induced gingival overgrowth. J Periodontol 68: 900–904, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Saito K, Mori S, Iwakura M, Sakamoto S. Immunohistochemical localization of transforming growth factor beta, basic fibroblast growth factor and heparan sulphate glycosaminoglycan in gingival hyperplasia induced by nifedipine and phenytoin. J Periodontal Res 31: 545–555, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Seymour RA, Ellis JS, Thomason JM. Risk factors for drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J Clin Periodontol 27: 217–223, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Sharma S, Dasroy SK. Images in clinical medicine. Gingival hyperplasia induced by phenytoin. N Engl J Med 342: 325, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Sparks AB, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Mutational analysis of the APC/beta-catenin/Tcf pathway in colorectal cancer. Cancer Res 58: 1130–1134, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Stambolic V, Ruel L, Woodgett JR. Lithium inhibits glycogen synthase kinase-3 activity and mimics wingless signalling in intact cells. Curr Biol 6: 1664–1668, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Standaert ML, Galloway L, Karnam P, Bandyopadhyay G, Moscat J, Farese RV. Protein kinase C-zeta as a downstream effector of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase during insulin stimulation in rat adipocytes. Potential role in glucose transport. J Biol Chem 272: 30075–30082, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Sugden PH, Fuller SJ, Weiss SC, Clerk A. Glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) in the heart: a point of integration in hypertrophic signalling and a therapeutic target? A critical analysis. Br J Pharmacol 153, Suppl 1: S137–153, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Trackman PC, Kantarci A. Connective tissue metabolism and gingival overgrowth. Crit Rev Oral Biol Med 15: 165–175, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Tuttle KR. Protein kinase C-beta inhibition for diabetic kidney disease. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 82, Suppl 1: S70–74, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Utsugi M, Dobashi K, Ishizuka T, Masubuchi K, Shimizu Y, Nakazawa T, Mori M. C-Jun-NH2-terminal kinase mediates expression of connective tissue growth factor induced by transforming growth factor-beta1 in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 28: 754–761, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Uzel MI, Kantarci A, Hong HH, Uygur C, Sheff MC, Firatli E, Trackman PC. Connective tissue growth factor in drug-induced gingival overgrowth. J Periodontol 72: 921–931, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Woodgett JR. Judging a protein by more than its name: GSK-3. Sci STKE 2001: RE12, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Zeng L, Fagotto F, Zhang T, Hsu W, Vasicek TJ, Perry WL, Lee JJ, 3rd, Tilghman SM, Gumbiner BM, Costantini F. The mouse Fused locus encodes Axin, an inhibitor of the Wnt signaling pathway that regulates embryonic axis formation. Cell 90: 181–192, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhang B, Zhou KK, Ma JX. Inhibition of connective tissue growth factor overexpression in diabetic retinopathy by SERPINA3K via blocking the WNT/beta-catenin pathway. Diabetes 59: 1809–1816, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Zhou S, Buckhaults P, Zawel L, Bunz F, Riggins G, Dai JL, Kern SE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. Targeted deletion of Smad4 shows it is required for transforming growth factor beta and activin signaling in colorectal cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95: 2412–2416, 1998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]