Abstract

We tested several molecular and cellular mechanisms of cardiomyocyte contraction-relaxation function that could account for the reduced systolic and enhanced diastolic function observed with exposure to extracellular Zn2+. Contraction-relaxation function was monitored in isolated rat and mouse cardiomyocytes maintained at 37°C, stimulated at 2 or 6 Hz, and exposed to 32 μM Zn2+ or vehicle. Intracellular Zn2+ detected using FluoZin-3 rose to a concentration of ∼13 nM in 3–5 min. Peak sarcomere shortening was significantly reduced and diastolic sarcomere length was elongated after Zn2+ exposure. Peak intracellular Ca2+ detected by Fura-2FF was reduced after Zn2+ exposure. However, the rate of cytosolic Ca2+ decline reflecting sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+-ATPase (SERCA2a) activity and the rate of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger activity evaluated by rapid Na+-induced Ca2+ efflux were unchanged by Zn2+ exposure. SR Ca2+ load evaluated by rapid caffeine exposure was reduced by ∼50%, and L-type calcium channel inward current measured by whole cell patch clamp was reduced by ∼70% in cardiomyocytes exposed to Zn2+. Furthermore, ryanodine receptor (RyR) S2808 and phospholamban (PLB) S16/T17 were markedly dephosphorylated after perfusing hearts with 50 μM Zn2+. Maximum tension development and thin-filament Ca2+ sensitivity in chemically skinned cardiac muscle strips were not affected by Zn2+ exposure. These findings suggest that Zn2+ suppresses cardiomyocyte systolic function and enhances relaxation function by lowering systolic and diastolic intracellular Ca2+ concentrations due to a combination of competitive inhibition of Ca2+ influx through the L-type calcium channel, reduction of SR Ca2+ load resulting from phospholamban dephosphorylation, and lowered SR Ca2+ leak via RyR dephosphorylation. The use of the low-Ca2+-affinity Fura-2FF likely prevented the detection of changes in diastolic Ca2+ and SERCA2a function. Other strategies to detect diastolic Ca2+ in the presence of Zn2+ are essential for future work.

Keywords: cardiac, myocyte, sarcomere, L-type channel, ryanodine receptor

the importance of zinc and zinc ion (Zn2+) in cardiac muscle function is only partially understood at this time. Cardiac zinc content correlates positively with ejection fraction (EF) in humans (18), and zinc supplementation to cardioplegic solution protects against the loss of systolic function and enhances diastolic function during and after ischemia-reperfusion injury (23–25). It has been suggested that zinc combats oxidative stress associated with ischemia-reperfusion and diabetes in part by enhancing the capacity of the zinc-binding protein metallothionein (15), which shields against reactive oxygen species (13, 23–25, 27, 36).

Zinc deficiency (<10.7 μM plasma Zn2+), which occurs in as high as 15% of nonhospitalized aging persons in Western society (5) and a higher percentage in many non-Western societies (26), furthermore accompanies all incidences of congestive heart failure as detected in one cohort of octogenarians (21) and correlates with incidence and severity of ischemic cardiomyopathy (31). There are also credible anecdotal and correlative reports that zinc supplementation can reduce angina pectoris (8). A more complete understanding of zinc-sensitive mechanisms at a cellular level is clearly warranted.

We have reported that extracellular Zn2+ elongates diastolic cardiomyocyte sarcomere length (20) and especially enhances relaxation function in cardiomyocytes isolated from hyperglycemic, prediabetic rats (39). Zinc-sensitive mechanisms of cardiomyocyte relaxation function were not fully identified in previous studies, although Zn2+ would be expected to have some effect on Ca2+ regulation. It has been reported, for example, that intracellular Zn2+ regulation closely mimics Ca2+ regulation, and both intracellular Zn2+ transients and Zn2+ sparks in isolated cardiomyocytes appear similar to those of Ca2+ (32). To our knowledge, the only other reports regarding the effects of zinc on cardiac function demonstrate that extracellular Zn2+ reduces Ca2+ influx through the voltage-gated L-type channel (1, 33). These findings collectively suggest that Zn2+ competes with Ca2+ for common regulatory processes at the cellular level. However, specific molecular and cellular mechanisms responsible for cardiac relaxation function have not yet been examined for zinc sensitivity.

In the present study, we examine possible mechanisms by which extracellular Zn2+ exposure enhances cardiac relaxation as observed previously at the whole heart (23–25) and cellular levels (20, 39). We found that Zn2+ did not affect myofilament force production, thin-filament sensitivity to calcium activation or Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX), but did reduce L-type channel inward current, sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) Ca2+ load, and ryanodine receptor (RyR) and phospholamban (PLB) phosphorylation status, which are all consistent with a reduced cellular Ca2+ load that improves relaxation function by a concomitant reduction in diastolic intracellular Ca2+.

METHODS

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of The University of Vermont and complied with the Guide for the Use and Care of Laboratory Animals published by the National Institutes of Health. Male Wistar-Kyoto rats were obtained from Harlan Sprague Dawley (Indianapolis, IN) and used between 10 and 16 wk of age. Male C57BL/6N mice at least 30 wk old were obtained from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). Animals were anesthetized by inhalation of 1.5–5% isoflurane for at least 5 min and until unresponsive to tail pinch. Hearts were then rapidly removed for isolation of papillary muscles and cardiomyocytes, and subjects died by exsanguination. All chemicals and reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted.

Intracellular Zn2+ distribution.

Rat left ventricle (LV) cardiomyocytes were isolated using retrograde perfusion of collagenase solution according to methods described elsewhere (19). Isolated rat cardiomyocytes were imaged using a confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510 META) fitted with 100× oil objective. Cardiomyocytes were loaded with Zn2+ indicator FluoZin-3AM and T-tubules indicator Di-8-ANEPPS (Invitrogen). Cardiomyocytes were electrically simulated at 2 Hz at 37°C with normal superfusion solution containing (in mM) 120 NaCl, 5.4 KCl, 0.5 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, 5.5 glucose, pH 7.4. Confocal images of FluoZin-3 and Di-8-ANEPPS were acquired prior to and after cardiomyocyte exposure to our normal superfusion solution containing 32 μM Zn2+ by addition of zinc acetate (ZnAc).

Cardiomyocyte function in response to Zn2+.

Isolated rat cardiomyocytes were placed on a heated stage of an inverted Nikon fluorescence microscope fitted with a 40× objective and electrically stimulated at 2 and 6 Hz while bathed in normal superfusion solution containing 0, 8, 16, 24, and 32 μM Zn2+. Dynamic sarcomere length was detected by Fourier transform of the digital image (IonOptix, Milton, MA) at 240 Hz. Eight cardiomyocytes were examined under each combination of Zn2+ concentration and stimulation rate.

To estimate intracellular Zn2+ concentration achieved with 32 μM Zn2+, isolated rat cardiomyocytes were loaded with FluoZin-3AM. Excitation and emission wavelengths were 490 nm and 510 nm, respectively, and background fluorescence was detected after lysing with 4 μM digitonin. Cardiomyocytes were exposed to 32 μM Zn2+ until intracellular Zn2+ reached equilibrium. Then 200 μM Zn2+ was applied to achieve a maximum intracellular Zn2+ followed by 100 μM N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN), a strong Zn2+ chelator, to achieve a minimum intracellular Zn2+. The fluorescence values at maximum and minimum Zn2+ conditions (Imax and Imin, respectively) were used to calculate intracellular Zn2+ concentration according to the following calibration equation:

| (1) |

where Kd is the dissociation constant of FluoZin-3 for Zn2+. We used a Kd value of 15 nM as provided by the manufacturer (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA).

For detection of contraction-relaxation function and intracellular Ca2+ in response to Zn2+, cardiomyocytes were loaded with Fura-2FF (Teflabs, Austin, TX) and FluoZin-3 (Invitrogen) to monitor both intracellular Ca2+ and Zn2+ according to Devinney et al. (7). Cardiomyocytes were bathed in normal superfusion solution and electrically paced at 2 Hz for at least 5 min prior to bathing with superfusion solution containing 32 μM Zn2+. Excitation wavelengths of 490 nm and 405 nm were interleaved, and fluorescence emission recorded at 510 nm. Excitation at 365 nm was performed after the experiment, and background fluorescence was detected after lysing with 4 μM digitonin. Fluorescence ratio (R) of Fura-2FF was calculated as 365/405, which is linearly related to intracellular Ca2+ concentration (19). A nonlinear, least-squares fit of a single exponential was fit to the decay in fluorescence ratio as a measure of intracellular Ca2+ uptake rate (IDL 7.0, ITT Visual Information Solutions).

SR Ca2+ load and Ca2+ efflux rate via NCX.

Prior to and after exposure to 32 μM Zn2+, extracellular solution was rapidly switched to superfusion solution containing 10 mM caffeine, Li+ replacing Na+, and 0 Ca2+, which inhibited NCX and retained intracellular Ca2+. After 3 s, extracellular solution was rapidly switched to another solution containing 10 mM caffeine, 140 mM Na+, and 0 Ca2+ to allow efflux of Ca2+ via NCX. Peak fluorescence ratio after caffeine exposure (RCaff) relative to baseline ratio (Rbaseline) was taken to indicate releasable SR Ca2+ load. Ca2+ efflux rate (kefflux) by NCX was estimated from the nonlinear, least-squares fit of a single-exponential curve to the recorded fluorescence ratio: R = Rbaseline + Refflux·exp(−kefflux·t).

Whole cell patch clamp.

Isolated mouse cardiomyocytes were placed on glass coverslips and washed before recording with the following regular bathing solution (in mM): 117 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 2 CaCl2, 5 HEPES, 10 glucose, pH 7.4. Electrodes with a resistance of 2–3 MΩ were pulled from LE16 glass capillaries using a P-97 Flaming/Brown Micropipette puller and filled with intracellular solution containing (in mM) 120 CsCl, 4 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 EGTA, 5 ATP, 1 GTP, pH 7.4. Once a high-resistance seal of 1–2 GΩ was formed, the membrane was ruptured with gentle suction to achieve the whole cell configuration. The L-type channel inward current was isolated by exchanging regular bathing solution with Na+/K+ free solution containing (in mM) 117 choline chloride, 20 CsCl, 1.7 MgCl2, 1.8 BaCl2, 10 HEPES, 10 glucose, pH 7.4 for 5 min. The cell was later placed in 60 μM Zn2+ by ZnAc for 5 min and allowed to recover upon washout of Zn2+ for 6 min. The barium current (IBa) was elicited both in the presence and absence of Zn2+ by +10-mV voltage steps (37.5 ms) from −90 to +20 mV. Currents were recorded with an Axon Instruments CV-7B headstage connected to a Multiclamp 700A that was integrated by a Digidata 1322A to a Dell PC running pClamp 8.2. All currents were recorded after neutralization of cell capacitance with a Bessel filter of 4 kHz and a sampling frequency of 10 kHz. In order to monitor any changes in series resistance, no effort was made to compensate for series resistance during the experiment.

Current/voltage plots were analyzed offline using Clampfit 8.2. Peak IBa recorded at each voltage in the presence and absence of Zn2+ was divided by the peak IBa recorded at −10 mV in the absence of Zn2+ (I/IMax) and plotted against the corresponding voltage, V. All data were tested for normality with the Shapiro-Wilk test.

Excitable rat papillary muscle.

Excised rat papillary muscles were tied onto Ω-shaped platinum clamps, transferred to the muscle chamber containing oxygenated normal superfusion solution at 37°C, and connected between a force transducer (Scientific Instruments, Heidelberg, Germany) and micromanipulator as described by Selby et al. (28). Isometric contractions were evoked at 20% above threshold voltage, duration of 4.0 ms, and stimulation frequency of 2 Hz. After 10 min of steady-state contractures, half of the papillary muscles were exposed for 10 min to 50 μM Zn2+ added to the superfusion solution. The other half, not exposed to Zn2+, were monitored over the same time period and served as controls. Muscle strips were then removed from the apparatus, chemically skinned, and prepared for analysis of myofilament calcium sensitivity.

Myofilament calcium sensitivity.

Skinned papillary muscle strips were studied as previously described (28). Skinned strip was mounted between a piezoelectric motor and a strain gauge, lowered into relaxing solution (pCa 8.0) maintained at room temperature, and incrementally stretched to 2.2 μm sarcomere length. Isometric tension was recorded over various calcium concentrations between pCa 8.0 and 4.8 and analyzed for developed tension and calcium sensitivity.

Protein phosphorylation.

LVs were removed from eight rats, and aortas cannulated to allow retrograde perfusion of the coronary beds with modified Krebs-Hensleit solution containing (in mM) 108.8 NaCl, 4.0 KCl, 1.4 MgSO4, 1.4 KH2PO4, 25.0 NaHCO3, 11.1 glucose, 10.0 sodium pyruvate, 2.0 CaCl2, pH 7.4. LVs were electrically paced at 4 Hz. After reaching steady-state contractile function, four LVs were subjected with Krebs-Hensleit solution with 50 μM Zn2+ for 15 min and four LVs were perfused for similar time period without Zn2+ to serve as controls. LV homogenates were loaded into a 3–8% Tris-acetate gel and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. Western blot analysis was performed to detect phosphorylation of RyR S2808, PLB S16/T17, cardiac troponin I (TnI) S23,24 and myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) S20.

We used the following antibodies: anti-RyR (Thermo Scientific MA3–916); anti-phospho-RyR2 S2808 (Badrilla A010–30); anti-PLB (Thermo Scientific 2D12); anti-phospho-PLB-S16,T17 (Cell Signaling no. 8496); anti-phospho-TnI-S23,24 (Cell Signaling no. 4004) and anti-phospho-RLC-S20 (Abcam ab2480). Secondary anti-mouse antibody (Promega W4021) and secondary anti-rabbit antibody (Promega W4011) were used. Blots were developed with West Femto chemiluminescence (Thermo Scientific no. 34095). Ponceau staining (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to detect protein transferred onto nitrocellulose.

Statistical analysis.

Analysis of contraction-relaxation function of rat cardiomyocytes was performed using PASW Statistics 18.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Repeated-measures ANOVA, using different extracellular Zn2+ exposure conditions as repeated measures, was used to detect the relative effects of intracellular Zn2+ concentrations and extracellular Zn2+ exposure. Analysis of L-type channel inward currents collected with mouse cardiomyocytes was performed by one-way ANOVA using Origin 7.5. Paired samples t-tests were used to compare I/IMax recorded at −20 mV for the control, zinc, and wash conditions. All data are presented as means ± SE, and significance by statistical tests are reported at P < 0.05, P < 0.01, and P < 0.001. A significance level of P < 0.10 is presented if consistent with significant findings found for a similar variable.

RESULTS

Intracellular Zn2+ distribution in cardiomyocytes.

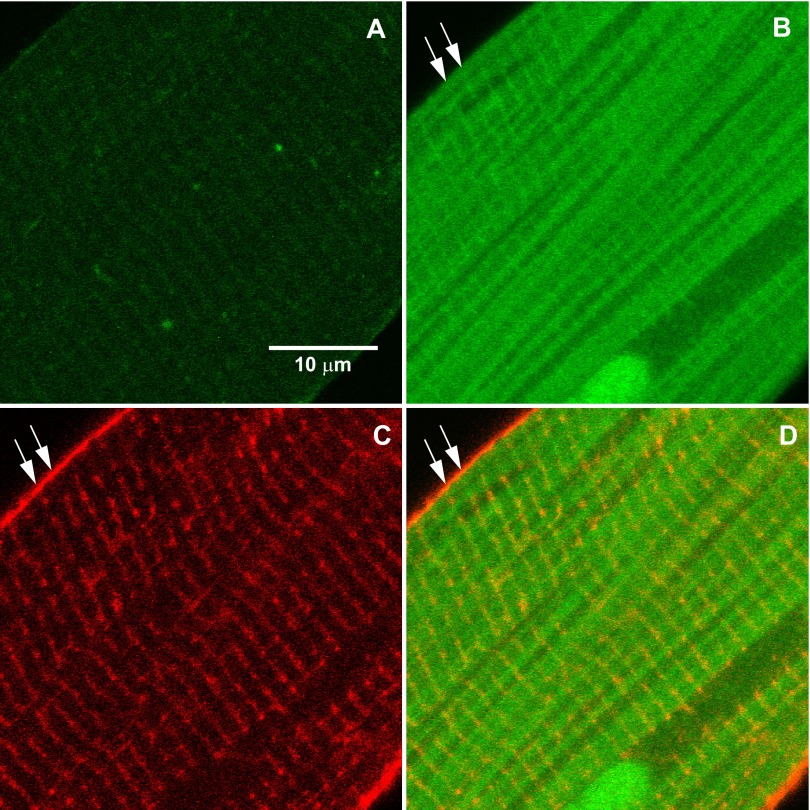

Figure 1, A and B, presents confocal microscopy images of FluoZin-3 fluorescence in a representative rat cardiomyocyte electrically paced at 2 Hz in Tyrode's solution at 37°C before and after 32 μM extracellular Zn2+ exposure. It is important to note that the accumulation of intracellular Zn2+ did not occur with extracellular Zn2+ exposure alone, but required electrical pacing (1). The accumulation of free intracellular Zn2+ detected by confocal microcopy appeared in and around myofilaments and particularly localized to stripes spaced ∼1.7–1.9 μm apart (indicated by the white arrows in Fig. 1B) corresponding to the length of the sarcomere.

Fig. 1.

Localization of Zn2+ in rat cardiomyocytes. A and B: confocal microscopy of cardiomyocyte loaded with FluoZin-3 before (A) and after (B) exposure to 32 μM Zn2+ and electrical pacing shows localization of intracellular Zn2+ accumulation around the myofilaments and most prominently along strips corresponding to a sarcomeric structure (at arrows). C: T-tubules were detected using Di-8-ANEPPS. D: orange color in the merged images of Zn2+ (green) and T-tubules (red) demonstrate that significant Zn2+ accumulation was localized to subcellular structures, possibly the terminal sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR).

Images of T-tubules (Fig. 1C), which colocalize with the Z-line of the sarcomere, provided a spatial reference for position of the Zn2+ stripes. The orange color of Fig. 1D illustrates the merged images of T-tubules (red) and intracellular Zn2+ (green) and suggests that a large portion of intracellular Zn2+ accumulated into specific cellular structures, such as in or near the terminal SR, adjacent to T-tubules.

Concentration-dependent effects of Zn2+.

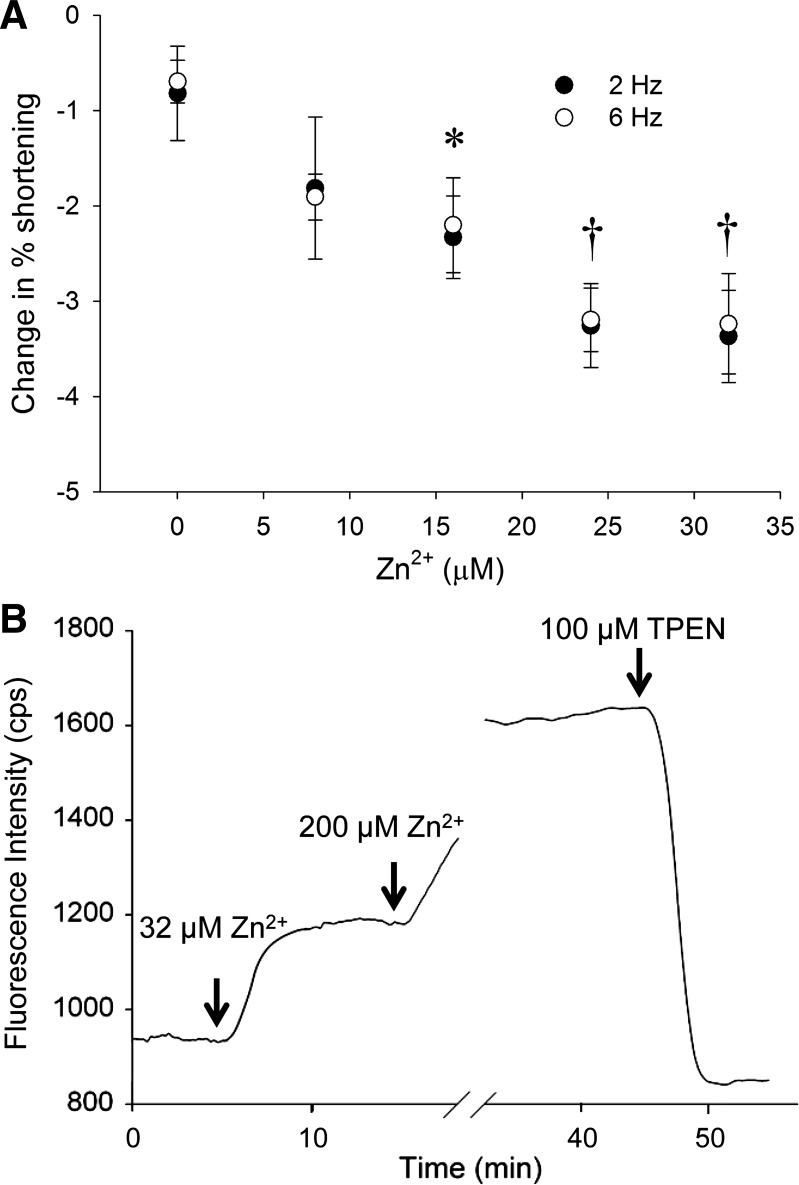

We tested various Zn2+ concentrations and stimulation frequencies on cardiomyocyte contractile function. Figure 2A illustrates the reduction in sarcomere shortening observed with 5-min exposure to various Zn2+ concentrations and at 2 and 6 Hz. Sarcomere shortening was reduced in proportion to Zn2+ concentration and similarly for 2 and 6 Hz, thus verifying that data acquired at 2 Hz reflect similar physiological responses at the more physiological pacing frequency of 6 Hz. Both 24 μM and 32 μM Zn2+ provided highly significant effects on reducing cardiomyocytes contraction. We therefore chose concentrations at 32 μM Zn2+ or higher in all subsequent experiments to better guarantee detectable physiological responses.

Fig. 2.

Cardiomyocyte shortening with Zn2+ exposure and calibration of Zn2+ accumulation. A: cardiomyocyte shortening was reduced with Zn2+ concentration and was highly significantly different with concentrations greater than 24 μM Zn2+. B: representative fluorescence data illustrate the experimental protocol used with cardiomyocytes to detect intracellular Zn2+ by FluoZin-3. After Zn2+ exposure, intracellular Zn2+ fluorescent reached a steady state in 3–5 min. With exposure of 200 μM Zn2+, intracellular Zn2+ achieved a maximum fluorescence, and exposure to N,N,N′,N′-tetrakis(2-pyridylmethyl)ethylenediamine (TPEN) produced a minimum fluorescence condition. *P < 0.05; †P < 0.01.

Figure 2B illustrates the FluoZin-3 fluorescence recorded during exposure to 32 μM Zn2+, 200 μM Zn2+, and 100 μM TPEN. Taking the latter fluorescence values as Imax and Imin, respectively, we calculated using Eq. 1 that 5 min continuous exposure of 32 μM Zn2+ resulted in steady-state intracellular Zn2+ concentration of 12.6 ± 1.6 nM. We applied the same protocol to analyze the response of Fura-2FF to the same Zn2+ exposure protocol and found that Fura-2FF had a Kd for Zn2+ of 125.9 ± 27.6 nM, which is almost 10 times greater than that for FluoZin-3 and much greater than that reported previously for Fura-2FF in vitro (11). We therefore considered it reasonable to use Fura-2FF to detect intracellular Ca2+ without significant interference from physiological Zn2+ as proposed by Devinney et al. (7).

For purposes of analyzing the effects of extracellular Zn2+ exposure and intracellular Zn2+ accumulation, we defined three Zn2+ conditions as follows: 1) Pre condition (no Zn2+) prior to any extracellular Zn2+ exposure; 2) Acute condition immediately after extracellular Zn2+ exposure but without any appreciable rise in intracellular Zn2+; and 3) Post or steady state condition after intracellular Zn2+ had come to equilibrium with extracellular Zn2+ or similar time period for control experiment.

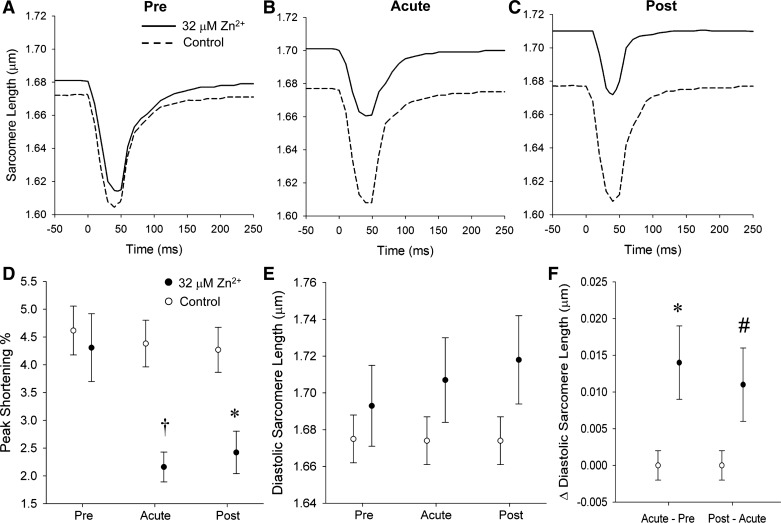

Cardiomyocyte sarcomere dynamics.

Figure 3, A–C, presents representative sarcomere dynamics tracings at the Pre, Acute, and Post conditions. Sarcomere dynamics under the Pre condition show similar function in Zn2+-exposed and control cardiomyocytes. Peak sarcomere shortening was significantly decreased from 4.31 ± 0.61 to 2.16 ± 0.27% (P < 0.01 by repeated-measures ANOVA) with acute exposure to Zn2+, and there was no measurable change in peak shortening in the control group (Fig. 3D). All of the temporal characteristics of sarcomere dynamics, e.g., time to peak and time to 50% recovery, were not differentially affected by 32 μM Zn2+ exposure (not shown).

Fig. 3.

Cardiomyocyte sarcomere dynamics. A–C show representative sarcomere length transients in Pre, Acute, and Post conditions. Exposure of extracellular Zn2+ (solid line) immediately reduced sarcomere shortening and enhanced diastolic sarcomere length (B). With intracellular Zn2+ accumulation from Acute to Post conditions, diastolic sarcomere length was continually increased. However, sarcomere shortening was not significantly changed. D: acute exposure to 32 μM extracellular Zn2+ reduced sarcomere shortening; however, there was no further reduction in the Post condition compared with Acute condition. E: diastolic sarcomere length was continually increased from Acute to Post conditions in the Zn2+ exposure group. F: both the changes of Acute vs. Pre and Post vs. Acute diastolic sarcomere length were longer in Zn2+ exposure group compared with control. #P < 0.10; *P < 0.05; †P < 0.01 by repeated-measures ANOVA.

Diastolic sarcomere length was significantly enhanced from 1.693 ± 0.022 μm in the Pre condition to 1.707 ± 0.023 μm (P < 0.05 by repeated-measures ANOVA) under Acute exposure to 32 μM Zn2+ (Fig. 3E). Diastolic sarcomere length increased further to 1.718 ± 0.024 μm in the Post condition compared with 1.707± 0.023 μm in the Acute (P < 0.1) (Fig. 3F).

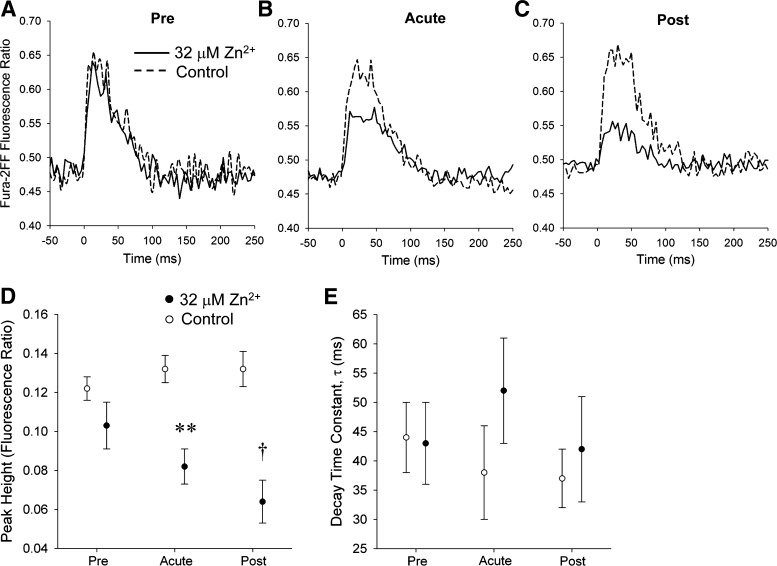

Ca2+ dynamics.

Figure 4, A–C, provides representative intracellular calcium transients at the Pre, Acute, and Post conditions in the Zn2+ exposure and control groups. Comparisons of ratio dynamics under the Pre condition indicate that cardiomyocytes yet to be exposed to Zn2+ displayed functional characteristics similar to those of control cardiomyocytes.

Fig. 4.

Cardiomyocyte Ca2+ dynamics. A–C show the Fura-2FF fluorescence ratio transients under Pre, Acute, and Post conditions. D: systolic Ca2+ fluorescence ratio was similar between the two groups under the Pre condition. Under Acute and Post conditions, Ca2+ fluorescence ratio was significantly lower in Zn2+ exposure group compared with control. E: decay time constant (and other temporal characteristics) showed no significant difference between the two groups. †P < 0.01; **P < 0.001 by repeated-measures ANOVA.

Within just a few stimulations after 32 μM Zn2+ application, peak Fura-2FF fluorescence ratio (R) was reduced from 0.103 ± 0.012 to 0.082 ± 0.009 (P < 0.001 by repeated-measures ANOVA) while remaining unchanged in the unexposed control group (Fig. 4D). Temporal characteristics of the Fura-2FF fluorescence ratio transient were not differentially affected by extracellular Zn2+ application including decay time constant τ (Fig. 4E), time to peak, and time to 50% return (not shown).

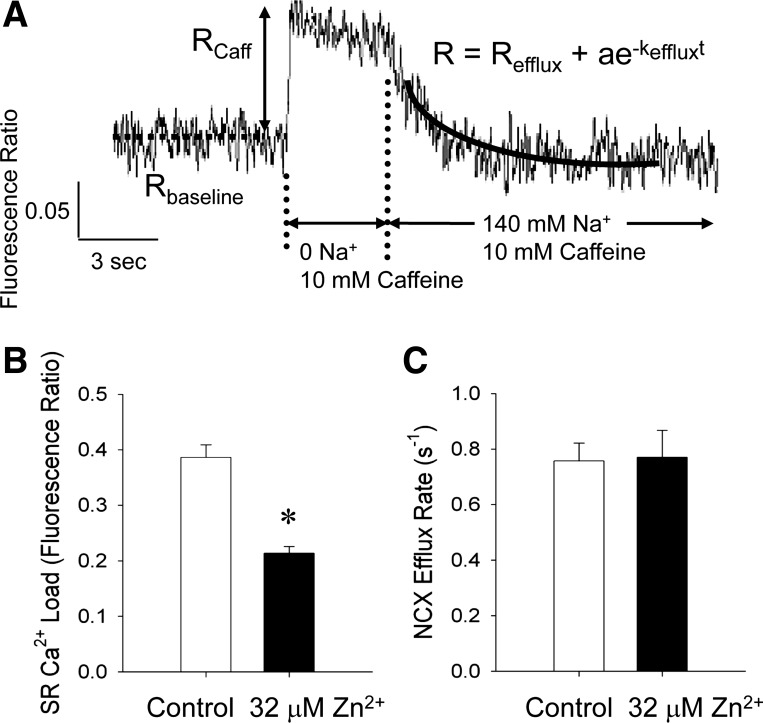

SR Ca2+ load and Ca2+ efflux rate via NCX.

Figure 5A illustrates the experimental protocol and representative fluorescence ratio tracing used to measure SR Ca2+ load and NCX efflux rate with Fura-2FF. We found SR Ca2+ load, represented by Rcaff, was reduced ∼50% in the Zn2+ exposure group (Fig. 5B). NCX efflux rate was not significantly changed after several minutes of Zn2+ exposure that led to a steady-state accumulation of intracellular Zn2+ (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Measures of Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX) efflux rate and total SR Ca2+ load. A: representative Fura-2FF transient is illustrated for cardiomyocyte under the Post condition and during rapid solution switching as described in methods. Fluorescence ratio after caffeine exposure (RCaff) was used to measure the total SR Ca2+ load. The exponential rate constant, kefflux, was used as a measure the NCX Ca2+ efflux rate. B: total Ca2+ content in the SR was greatly reduced in the cardiomyocytes exposed to 32 μM Zn2+. C: NCX efflux rate was similar between the control and Zn2+ exposure groups. *P < 0.05.

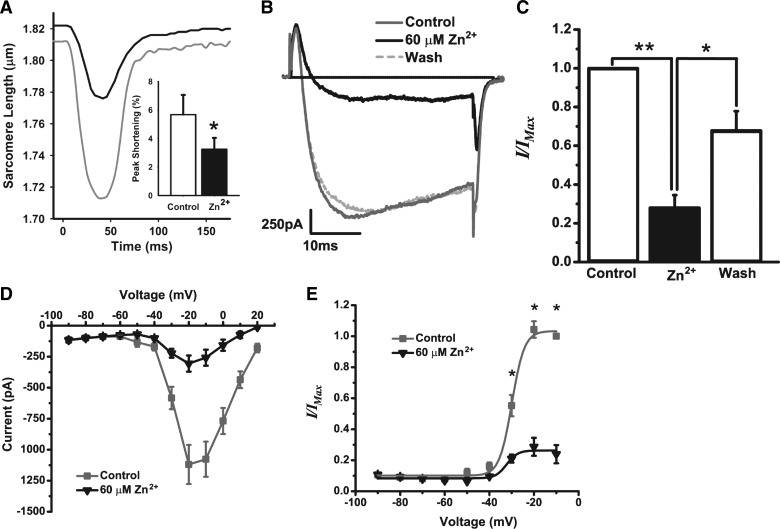

L-type calcium channel inward current.

It has been reported previously that L-type channel inward current in rat cardiomyocytes is reduced with exposure of extracellular Zn2+ (1, 33). To better understand the mechanisms by which Zn2+ reduces SR Ca2+ load without affecting NCX and Ca2+ efflux, we examined the L-type calcium channel inward current and its voltage dependence using whole cell patch clamp with isolated mouse cardiomyocytes, whose contractile response to extracellular Zn2+ was similar to that of rat cardiomyocytes (Fig. 6A). Peak contraction of mouse cardiomyocytes was reduced from 5.68 ± 1.38 to 3.25± 0.80% (P < 0.05) with exposure to Zn2+ and diastolic sarcomere length was significantly elongated from 1.742 ± 0.036 to 1.767 ± 0.033 μm (P < 0.05).

Fig. 6.

Effect of Zn2+ on the L-type channel inward current carried by barium ion (Ba2+) in mouse cardiomyocytes. A: mouse cardiomyocyte sarcomere length dynamics demonstrated a response to 32 μM Zn2+ similar to that observed in rat cardiomyocytes. Inset: peak shortening was reduced ∼50% after 5 min of 32 μM Zn2+ exposure. B: the Ba2+ current (IBa) was elicited by +10-mV voltage steps (37.5 ms) from −90 to +20 mV. In a representative cell, 60 μM Zn2+ reduced IBa recorded at −20 mV in a reversible manner. C: IBa recorded at −20 mV in the presence of Zn2+ (zinc) and after washout of Zn2+ (wash) was normalized to IBa recorded at −20 mV before Zn2+ exposure (control). Extracellular Zn2+ significantly reduced IBa and recovery was incomplete, but significantly close to baseline. D: current/voltage plot of IBa both in the presence (zinc, black triangles) and absence (control, gray squares) of Zn2+. E: IBa recorded at each voltage in both the presence (zinc, black triangles) and absence (control, gray squares) of Zn2+ was normalized to maximal IBa recorded at −10 mV. **P < 0.001; *P < 0.05.

In our measures of L-type calcium channel inward current, barium ion (Ba2+) was used instead of Ca2+ to resolve the L-type channel inward current and to reduce the contribution of Ca2+-dependent processes. The Ba2+ current (IBa) was elicited by +10-mV voltage steps (37.5 ms) from −90 to +20 mV and was maximal between −20 and −10 mV in all cells tested (n = 5). In a representative cell, IBa was maximally reduced by Zn2+ exposure after 5 min and was recovered following washout of Zn2+ after 6 min (Fig. 6B). Across all cells tested, there was a significant reduction in IBa by Zn2+ (27.97 ± 14.75%, P < 0.001) followed by incomplete yet significant recovery of IBa after washout of Zn2+ (67.86 ± 22.45%, P < 0.05; Fig. 6C).

Furthermore, Zn2+ did not shift the voltage that elicited maximal IBa (Fig. 6D), but significantly reduced the current at all voltages that elicited submaximal to maximal IBa (P < 0.05; Fig. 6E). Data were fit with the Boltzmann equation (r2 = 0.99) (2), and the voltage of half-maximal activation (V1/2) was not different between the absence (−29.91 ± 0.39 mV) and presence of Zn2+ (−32.25 ± 3.02 mV; Fig. 6E), suggesting that the reduction in IBa by Zn2+ was not due to a shift in the voltage dependence of activation.

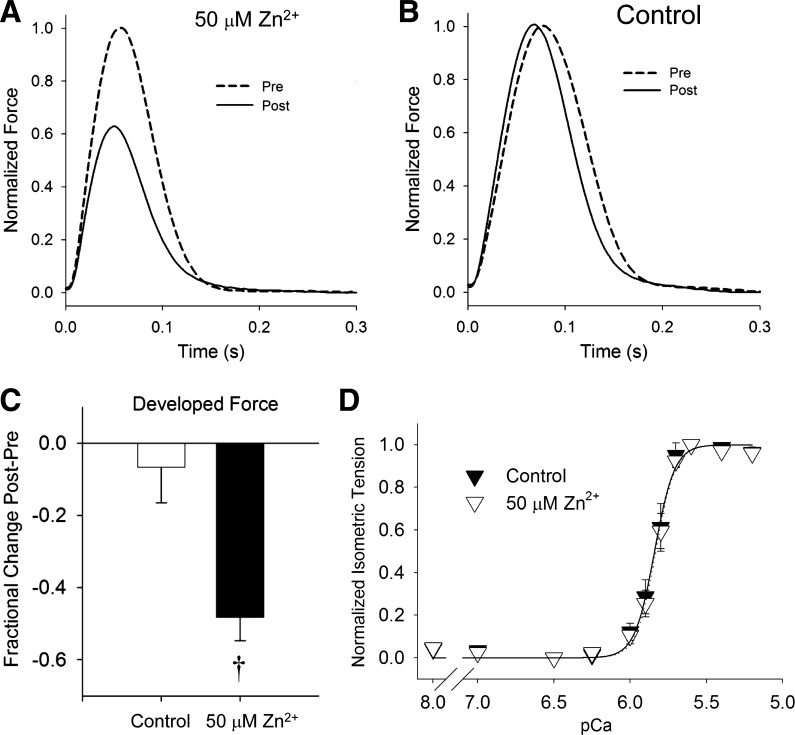

Myofilament calcium sensitivity.

To test whether Zn2+ exposure affected myofilament characteristics, we examined tension development and calcium sensitivity of myofilaments prepared from intact papillary muscles that had been exposed to Zn2+. Representative force transients from rat papillary muscle exposed to 50 μM Zn2+ for 10 min are presented in Fig. 7, A and B. Developed force was reduced by ∼50% with exposure to Zn2+ compared with unexposed controls (Fig. 7C). Temporal characteristics, such as time to peak (not shown), were not differentially affected by Zn2+. After chemically skinning the papillary muscles, myofilament maximal tension was found to be similar between Zn2+ exposed (7.62 ± 0.74 mN/mm2) and unexposed controls (7.80 ± 0.63 mN/mm2). Myofilament calcium sensitivity reflected in the normalized tension vs. pCa relationship was unaffected by Zn2+ exposure compared with controls (Fig. 7D).

Fig. 7.

Effects of Zn2+ on excitable papillary muscle force and myofilament calcium sensitivity. A and B: examples of normalized force produced by excitable papillary muscle stimulated at 2 Hz. After 50 μM extracellular Zn2+ exposure (A), developed force was significantly reduced in Post condition compared with Pre condition. Over the same time period, developed force was unchanged under control conditions (B). C: there was ∼50% reduction in developed force after 50 μM Zn2+ exposure compared with control. D: myofilament sensitivity to calcium activation was similar between papillary muscles that had been previously exposed to 50 μM Zn2+ and unexposed controls. †P < 0.01.

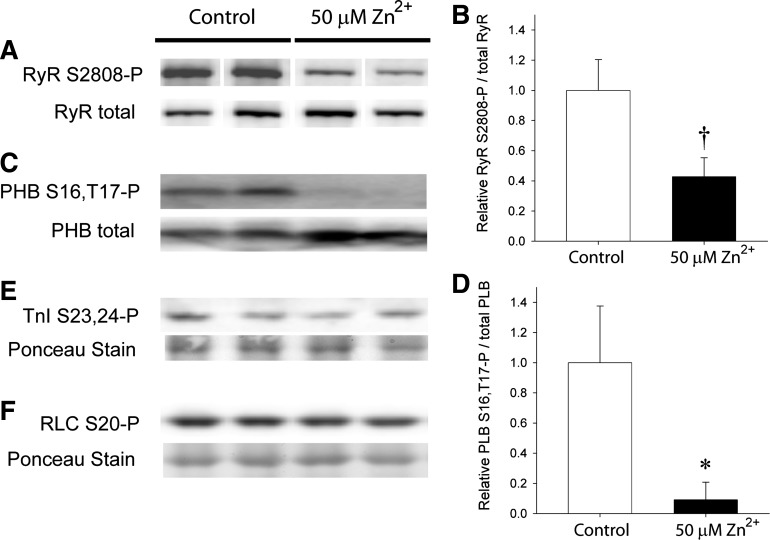

Protein phosphorylation.

Phosphorylation of RyR S2808 has already been demonstrated to be associated with a high open probability of RyR and SR Ca2+ leak (16, 29). We were curious to test if Zn2+ exposure could alter RyR S2808 phosphorylation and thus signal an effect on SR Ca2+ leak, which could underlie diastolic function. After LV perfusion with 50 μM Zn2+, RyR S2808 phosphorylation was visually reduced compared with unexposed LVs (Fig. 8A). Using the total RyR content for normalization, S2808 phosphorylation after Zn2+ exposure was reduced to about 55% of that of controls (Fig. 8B), indicating that Zn2+ can affect RyR phosphorylation level and channel open probability.

Fig. 8.

Protein phosphorylation with Zn2+ exposure. Western blots were examined for n = 4 rat hearts for each condition. Representative blots are shown for n = 2 in each condition. A: phosphorylated RyR S2808 in rat LV was reduced after exposure to 50 μM Zn2+ compared with nonexposed controls. Total RyR content was similar in all the LV homogenates examined. (White lines indicate repositioning of noncontiguous lanes to represent results from males only.) B: densitometry of RyR S2808 phosphorylation normalized to total RyR was significantly reduced with Zn2+ exposure. C: phosphorylation of PHB at S16 and T17 was visibly detectable under control conditions and nearly undetectable after Zn2+ exposure. D: densitometry of PHB S16,T17 phosphorylation normalized to total PLB was significantly reduced with Zn2+ exposure. E and F: phosphorylation of troponin I (TnI) at S23,24 and myosin regulatory light chain (RLC) at S20 was not discernibly affected with Zn2+ exposure. †P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

We further examined the phosphorylation status of PLB, TnI, and RLC. Phosphorylation of PLB was clearly detectable prior to Zn2+ exposure, but was nearly undetectable after Zn2+ exposure (Fig. 8, C and D). The expected functional effect would be an inhibition of SERCA2a and a reduction in the rate of calcium reuptake during diastole. Phosphorylation states of TnI (Fig. 8E) and RLC (Fig. 8F) were unchanged, however. The possible mechanisms by which zinc accumulation may have affected the activation of kinases or phosphatases are discussed below.

DISCUSSION

The enhancement of cardiac diastolic function elicited by extracellular Zn2+ exposure is exemplified at the organ level by lowering end-diastolic ventricular pressure (24, 25) and at the cellular level by elongating diastolic sarcomere length (20, 39). Cardiomyocytes of prediabetic rats are especially sensitive to Zn2+-dependent mechanisms of cardiac relaxation (39). With these findings in mind, we sought to uncover specific mechanisms of cardiomyocyte contraction-relaxation function affected by Zn2+. We did not detect significant effects of Zn2+ on Ca2+ reuptake rate by SERCA2a, Na+-dependent Ca2+ efflux by NCX, myofilament force production, or myofilament Ca2+ sensitivity, all of which are important contributors to cardiac relaxation function (4).

We did find a significant elongation of diastolic cardiomyocyte sarcomere length and significant reductions in peak intracellular Ca2+, SR Ca2+ load, L-type channel inward current and RyR S2808 and PLB S16,T17 phosphorylation with Zn2+ exposure. These data collectively implicate Zn2+ as an inhibitor of Ca2+ influx and intracellular Ca2+ accumulation by its blocking or competing for the L-type channel pore, which in turn reduces the trigger for Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release from the SR. The reduced phosphorylation of RyR S2808 after Zn2+ exposure would be expected to reduce SR Ca2+ leak and the sensitivity to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and thereby further contribute to reducing intracellular Ca2+ and myofilament activation in diastole (4). The reduction in PLB phosphorylation suggests that SERCA2a was also likely inhibited after Zn2+ exposure even if undetected by Fura-2FF, and SR Ca2+ load was reduced in part as a consequence. We consider these scenarios the most likely basis for reduced cardiac contractility and enhanced relaxation function after Zn2+ exposure.

Zn2+ and protein phosphorylation.

Our finding that Zn2+ reduces RyR S2808 phosphorylation is novel and potentially important in cardiomyocyte Ca2+ regulation. Phosphorylation of RyR S2808 has been associated with increased RyR open probability and SR Ca2+ leak due to dissociation of the stabilizing protein FKBP1B (16, 29). Phosphorylation of RyR S2808 has been found especially high in the context of hyperglycemia and diabetes (30, 38, 39). A Zn2+-dependent reduction in S2808 phosphorylation and subsequent reduction in SR Ca2+ leak could explain the enhanced sensitivity of the hyperglycemic prediabetic rat cardiomyocyte to the relaxing effects of Zn2+ (39). We could speculate that zinc acts as a structural component of RyR or of the RyR-FKBP complex such that adequate zinc conforms the RyR to reduce Ca2+ leak but also the S2808 site to be exposed to phosphatases or inaccessible to kinases. The RyR amino acid sequence immediately proximal to S2808 is RRIS, which implicates a PKA site and therefore a potentially important substrate for β-adrenergic signaling. Such exposure would furthermore leave RyR function particularly susceptible to oxidative stress, which is known to liberate protein-bound zinc (9, 34) and also to enhance RyR open probability (37).

We also report a significant reduction on PLB phosphorylation after Zn2+ exposure, but no change in TnI or RLC phosphorylation. At this point there are many possible phosphosignaling mechanisms affected by Zn2+ including the upregulation of phosphodiesterase (10) which would reduce cAMP availability and in turn PKA activity. However, given that both PLB and TnI are known to be phosphorylated by PKA and RLC is phosphorylated by a calmodulin-dependent kinase, we would surmise that Zn2+ did not downregulate activity of PKA or calmodulin-dependent kinases, except perhaps calmodulin-dependent SR kinase (3). We instead suspect that Zn2+ activated protein phosphatase 1 (PP1) or some other yet undetermined Zn2+-dependent mechanism. PP1 is known to dephosphorylate PLB with high selectivity, while other phosphatases like protein phosphatase 2a and the zinc-dependent alkaline phosphatase would be expected to dephosphorylate TnI, which was not detected.

We did not examine the phosphostatus of L-type calcium channel subunits, because the direct influence of phosphorylation on inward current is not completely well understood and may not be well founded (12, 35). Our use of the mouse cardiomyocytes to characterize L-type calcium channel response to Zn2+ exposure should be considered relevant to the observations in the rat due to the similar contractile responses observed in the mouse and rat cardiomyocytes and due to the >95% homologous amino acid sequence between the species. The mouse cardiomyocyte also provides us a foundation from which we can use transgenic models and further investigate the submolecular basis of competitive inhibition of inward current by Zn2+ and the possible influence of subunit phosphorylation and dephosphorylation on Zn2+ conductance.

Diastolic Ca2+ concentration and sarcomere length.

In the absence of a change in myofilament tension or calcium sensitivity with Zn2+, lengthening of the cardiomyocyte sarcomere in diastole must be due to a lower diastolic intracellular Ca2+. We would have preferred to measure diastolic Ca2+ directly rather than to make this inference. However, Ca2+ indicators suited to detect changes in diastolic Ca2+ are also highly sensitive to Zn2+. Fura-2, for example, is 100 fold more sensitive to Zn2+ than to Ca2+ (1), and a rise in Zn2+ on the order of 10 nM would add detectable artifact to Fura-2 fluorescence. We used Fura-2FF to obviate any possible fluorescence artifact due to intracellular Zn2+ as suggested by Devinney et al. (7). However, Fura-2FF bears a Kd for Ca2+ of ∼6 μM, and as a consequence Fura-2FF is unable to differentiate cytosolic Ca2+ concentrations under ∼600 nM (7). Thus we were prevented from detecting any significant Zn2+-dependent changes in diastolic intracellular Ca2+. Noting that PLB was significantly dephosphorylated with Zn2+, it is natural to expect that SERCA2a function is inhibited (4). To continue with this line of questioning, we will need to find a new strategy, methodology, or dye to allow detection of diastolic Ca2+ without interference from Zn2+.

There has been a previous report of Zn2+ inhibiting NCX function in vesicles prepared from brain tissue (6). We found no significant effect of intracellular Zn2+ accumulation on NCX efflux rate of cytosolic Ca2+. Our results furthermore suggest no competition between Zn2+ and Ca2+ for NCX due to either the dramatically lower concentration of cytosolic Zn2+ compared with Ca2+ in the cardiomyocyte or the specificity of cardiac NCX for Ca2+ as reported previously (17). Our findings implicate the reduction in Ca2+ influx via L-type calcium channel and reduction in SR Ca2+ leak as contributing to a reduction in diastolic Ca2+, which underlies the longer diastolic sarcomere length induced by Zn2+.

Intracellular Zn2+ regulation and accumulation.

In the present study we observed that prolonged exposure to extracellular Zn2+ resulted in a slow (over minutes) yet significant rise in intracellular Zn2+ accumulation and a significant reduction of releasable SR Ca2+. The temporal characteristics we observe with regard to Zn2+ accumulation are consistent with those reported previously by Atar et al. (1), but differ from the relatively fast (under seconds) intracellular Zn2+ transients reported by Tuncay et al. (32).

The structures containing nanomolar concentrations of free Zn2+ in the I-band detected using confocal microscopy correspond well to the structures containing millimolar concentrations of total zinc in the I-band detected by X-ray fluorescence microscopy (20). This structure does not exhibit accumulation of free Zn2+ until after electrical pacing commences and therefore cannot represent an extracellular space. We speculate that the SR would be the most likely organelle to participate in Zn2+ accumulation and protein-bound zinc retention. Picello et al. (22) report that skeletal muscle RyR strongly binds zinc. RyR is rich in histidines, glutamic acids, aspartic acids and cysteines, which singly or as part of motifs avidly bind metals (14). To our knowledge, specific zinc-binding sites, however, have not yet been identified on this protein or other SR associated proteins.

Conclusion.

While Zn2+ exposure to excitable myocardium does not affect the function or activity of the force-producing myofilaments or NCX, our findings do suggest that Zn2+ can affect relaxation function through a significant reduction in cardiomyocyte intracellular Ca2+ due in part to a potent inhibition of L-type channel inward current by Zn2+. The reduced phosphorylation of RyR S2808 and PLB S16,T17 would furthermore be expected to reduce SR Ca2+ leak and load, respectively, which together would contribute to a reduced diastolic [Ca2+]. A reduced diastolic [Ca2+] achieved with reduced SERCA function appears at first to be paradoxical. We believe at this time that the concomitant and potent reduction in L-type calcium channel inward current represents the mechanism most responsible for reducing total intracellular Ca2+ load. There is still much to learn about the role of Zn2+ in its competitive inhibition of Ca2+ through channels such as the L-type calcium channel, the modulation of Ca2+ regulatory proteins, and activation of signaling pathways including those responding to oxidative stress or leading to modifications in gene expression.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-086902.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: T.Y., J.S.V., R.J.D., and B.M.P. conception and design of research; T.Y., J.S.V., M.J.V., K.J.B., and S.P.B. performed experiments; T.Y., J.S.V., M.J.V., K.J.B., S.P.B., and B.M.P. analyzed data; T.Y., J.S.V., R.J.D., and B.M.P. interpreted results of experiments; T.Y., J.S.V., and B.M.P. prepared figures; T.Y. and B.M.P. drafted manuscript; T.Y., J.S.V., and B.M.P. edited and revised manuscript; B.M.P. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful for the expert technical assistance of Marilyn Wadsworth and Dr. Douglas Taatjes and for the use of the Microscopy Imaging Center at The University of Vermont.

REFERENCES

- 1.Atar D, Backx PH, Appel MM, Gao WD, Marban E. Excitation-transcription coupling mediated by zinc influx through voltage-dependent calcium channels. J Biol Chem 270: 2473–2477, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aulbach F, Simm A, Maier S, Langenfeld H, Walter U, Kersting U, Kirstein M. Insulin stimulates the L-type Ca2+ current in rat cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 42: 113–120, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baltas LG, Karczewski P, Krause EG. Effects of zinc on phospholamban phosphorylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 232: 394–397, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bers DM. Cardiac excitation-contraction coupling. Nature 415: 198–205, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bogden JD, Oleske JM, Munves EM, Lavenhar MA, Bruening KS, Kemp FW, Holding KJ, Denny TN, Louria DB. Zinc and immunocompetence in the elderly: baseline data on zinc nutriture and immunity in unsupplemented subjects. Am J Clin Nutr 46: 101–109, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Colvin RA. Zinc inhibits Ca2+ transport by rat brain Na+/Ca2+ exchanger. Neuroreport 9: 3091–3096, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Devinney MJ, 2nd, Reynolds IJ, Dineley KE. Simultaneous detection of intracellular free calcium and zinc using fura-2FF and FluoZin-3. Cell Calcium 37: 225–232, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eby GA, Halcomb WW. High-dose zinc to terminate angina pectoris: a review and hypothesis for action by ICAM inhibition. Med Hypotheses 66: 169–172, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fliss H, Menard M, Desai M. Hypochlorous acid mobilizes cellular zinc. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 69: 1686–1691, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Francis SH, Blount MA, Corbin JD. Mammalian cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases: molecular mechanisms and physiological functions. Physiol Rev 91: 651–690, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hyrc KL, Bownik JM, Goldberg MP. Ionic selectivity of low-affinity ratiometric calcium indicators: mag-Fura-2, Fura-2FF and BTC. Cell Calcium 27: 75–86, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamp TJ, Hell JW. Regulation of cardiac L-type calcium channels by protein kinase A and protein kinase C. Circ Res 87: 1095–1102, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kang YJ. The antioxidant function of metallothionein in the heart. Proc Soc Exper Biol Med 222: 263–273, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karlin S, Zhu ZY. Classification of mononuclear zinc metal sites in protein structures. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 94: 14231–14236, 1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maret W. The function of zinc metallothionein: a link between cellular zinc and redox state. J Nutr 130: 1455S–1458S, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marx SO, Reiken S, Hisamatsu Y, Jayaraman T, Burkhoff D, Rosemblit N, Marks AR. PKA phosphorylation dissociates FKBP12.6 from the calcium release channel (ryanodine receptor): defective regulation in failing hearts. Cell 101: 365–376, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ohana E, Segal D, Palty R, Ton-That D, Moran A, Sensi SL, Weiss JH, Hershfinkel M, Sekler I. A sodium zinc exchange mechanism is mediating extrusion of zinc in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 279: 4278–4284, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oster O, Dahm M, Oelert H. Element concentrations (selenium, copper, zinc, iron, magnesium, potassium, phosphorous) in heart tissue of patients with coronary heart disease correlated with physiological parameters of the heart. Eur Heart J 14: 770–774, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Palmer BM, Moore RL. Excitation wavelengths for fura 2 provide a linear relationship between [Ca2+] and fluorescence ratio. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 279: C1278–C1284, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Palmer BM, Vogt S, Chen Z, Lachapelle RR, Lewinter MM. Intracellular distributions of essential elements in cardiomyocytes. J Struct Biol 155: 12–21, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pepersack T, Rotsaert P, Benoit F, Willems D, Fuss M, Bourdoux P, Duchateau J. Prevalence of zinc deficiency and its clinical relevance among hospitalised elderly. Arch Gerontol Geriatr 33: 243–253, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Picello E, Damiani E, Margreth A. Low-affinity Ca2+-binding sites versus Zn2+-binding sites in histidine-rich Ca2+-binding protein of skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 186: 659–667, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Powell SR, Aiuto L, Hall D, Tortolani AJ. Zinc supplementation enhances the effectiveness of St. Thomas' Hospital No 2 cardioplegic solution in an in vitro model of hypothermic cardiac arrest. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 110: 1642–1648, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Powell SR, Hall D, Aiuto L, Wapnir RA, Teichberg S, Tortolani AJ. Zinc improves postischemic recovery of isolated rat hearts through inhibition of oxidative stress. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 266: H2497–H2507, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Powell SR, Nelson RL, Finnerty J, Alexander D, Pottanat G, Kooker K, Schiff RJ, Moyse J, Teichberg S, Tortolani AJ. Zinc-bis-histidinate preserves cardiac function in a porcine model of cardioplegic arrest. Ann Thorac Surg 64: 73–80, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad AS. Discovery of human zinc deficiency: 50 years later. J Trace Elem Med Biol 26: 66–69, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prasad AS, Bao B, Beck FW, Kucuk O, Sarkar FH. Antioxidant effect of zinc in humans. Free Radic Biol Med 37: 1182–1190, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Selby DE, Palmer BM, LeWinter MM, Meyer M. Tachycardia-induced diastolic dysfunction and resting tone in myocardium from patients with a normal ejection fraction. J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 147–154, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shan J, Betzenhauser MJ, Kushnir A, Reiken S, Meli AC, Wronska A, Dura M, Chen BX, Marks AR. Role of chronic ryanodine receptor phosphorylation in heart failure and beta-adrenergic receptor blockade in mice. J Clin Invest 120: 4375–4387, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shao CH, Wehrens XH, Wyatt TA, Parbhu S, Rozanski GJ, Patel KP, Bidasee KR. Exercise training during diabetes attenuates cardiac ryanodine receptor dysregulation. J Appl Physiol 106: 1280–1292, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shokrzadeh M, Ghaemian A, Salehifar E, Aliakbari S, Saravi SS, Ebrahimi P. Serum zinc and copper levels in ischemic cardiomyopathy. Biol Trace Elem Res 127: 116–123, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tuncay E, Bilginoglu A, Sozmen NN, Zeydanli EN, Ugur M, Vassort G, Turan B. Intracellular free zinc during cardiac excitation-contraction cycle: calcium and redox dependencies. Cardiovasc Res 89: 634–642, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Turan B. Zinc-induced changes in ionic currents of cardiomyocytes. Biol Trace Elem Res 94: 49–60, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turan B, Fliss H, Desilets M. Oxidants increase intracellular free Zn2+ concentration in rabbit ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 272: H2095–H2106, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Heyden MA, Wijnhoven TJ, Opthof T. Molecular aspects of adrenergic modulation of cardiac L-type Ca2+ channels. Cardiovasc Res 65: 28–39, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vassort G, Turan B. Protective role of antioxidants in diabetes-induced cardiac dysfunction. Cardiovasc Toxicol 10: 73–86, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yan Y, Liu J, Wei C, Li K, Xie W, Wang Y, Cheng H. Bidirectional regulation of Ca2+ sparks by mitochondria-derived reactive oxygen species in cardiac myocytes. Cardiovasc Res 77: 432–441, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yaras N, Ugur M, Ozdemir S, Gurdal H, Purali N, Lacampagne A, Vassort G, Turan B. Effects of diabetes on ryanodine receptor Ca release channel (RyR2) and Ca2+ homeostasis in rat heart. Diabetes 54: 3082–3088, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi T, Cheema Y, Tremble SM, Bell SP, Chen Z, Subramanian M, LeWinter MM, VanBuren P, Palmer BM. Zinc-induced cardiomyocyte relaxation in a rat model of hyperglycemia is independent of myosin isoform. Cardiovasc Diabetol 11: 135, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]