Abstract

Purpose

Graduate medical education (GME) plays a key role in the U.S. health care workforce, defining its overall size and specialty distribution, and influencing physician practice locations. Medicare provides nearly $10 billion annually to support GME, and faces growing policymaker interest in creating accountability measures. The purpose of this study was to develop and test candidate GME outcome measures related to physician workforce.

Method

The authors performed a secondary analysis of data from the American Medical Association Physician Masterfile, National Provider Identifier file, Medicare claims, and National Health Service Corps, measuring the number and percentage of graduates from 2006 to 2008 practicing in high-need specialties and underserved areas aggregated by their U.S. GME program.

Results

Average overall primary care production rate was 25.2% for the study period, although this is an overestimate since hospitalists could not be excluded. Of 759 sponsoring institutions, 158 produced no primary care graduates, and 184 produced more than 80%. An average of 37.9% of Internal Medicine residents were retained in primary care, including hospitalists. Mean general surgery retention was 38.4%. Overall, 4.8% of graduates practiced in rural areas; 198 institutions produced no rural physicians, and 283 institutions produced no Federally Qualified Health Center or Rural Health Clinic physicians.

Conclusions

GME outcomes are measurable for most institutions and training sites. Specialty and geographic locations vary significantly. These findings can inform educators and policy-makers during a period of increased calls to align the GME system with national health needs.

Graduate Medical Education (GME) plays a key role in the make-up of the U.S. physician workforce and it represents the largest public investment in health workforce development through Medicare, Medicaid, and other federal funding. Yet, the physician workforce is struggling to meet the nation's health care needs, particularly in primary care and geographically underserved areas. Amid increasing calls for greater accountability in the GME system, we propose a method for examining institutional GME outcomes that can ultimately inform future education and policy decisions.

Background

The graduate medical education (GME) system dictates the overall size and specialty mix of the U.S. physician workforce. With few exceptions, physician licensing in every state requires at least 1 year of U.S. GME. Therefore, the total availability of U.S. training positions defines the overall size of the physician workforce, and the number of GME training positions available for each specialty effectively determines the number of individuals who can pursue a career in that specialty. The location of GME programs affects long-term practice locations since physicians tend to locate in the same geographic area as their residency,1-3 and exposure to rural and underserved settings during GME increases the likelihood of continuing to work with these populations after graduation.4-7

GME has been publicly funded since the passage of Medicare in 1965. In 2009, Medicare contributed $9.5 billion8 to GME. Medicaid provided an additional $3.18 billion.9 These two contributions represent the largest public investment in US health workforce development.10 Despite this public investment, physician shortages in certain specialties, including primary care, general surgery, and psychiatry, and in rural and underserved areas, persist.11-18 These shortages limit access to care, and a growing number of studies suggest that health systems built on strong primary care bases improve quality and constrain the cost of health care.19-22 Even with good evidence that the composition of the physician workforce affects access, quality and cost, federal GME funding is provided without specialty training expectations or requirements to evaluate training outcomes.

As early as 1965 and as recently as 2011, advisory bodies have recommended GME be more accountable to the public's health needs.23-25 In 2010, there were three prominent calls for increased GME accountability. The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation issued a report concluding that, because GME is financed with public funds, it should be accountable to the public.26 The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission recommended greater transparency with and accountability for Medicare GME payments.27 The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act mandated the Council on Graduate Medical Education develop performance measures and guidelines for longitudinal evaluation for GME programs.28

Despite these calls for accountability, important characteristics of GME programs such as training in priority health needs and relevant delivery systems, and workforce outcomes, including specialty and geographic distribution, remain unaddressed. The impact of residency programs on local or regional physician workforce is not measured or tracked. Nonetheless, measuring GME outcomes is essential to inform deliberations about medical workforce problems and policies. This is particularly true given current GME resource constraints and the reexamination of the adequacy of the U.S. physician workforce following the passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.29,30

Attention has been paid to geographic and specialty outcomes of undergraduate medical education;31 however, relatively little scholarship has been applied to these issues in GME programs. Measuring GME outcomes is difficult because of the complex arrangement of the training institutions and the variable paths traveled by the trainees. At the current time, approximately 111,586 “residents” and “fellows” are employed in 8,967 training programs in 150 specialty areas.32 These programs are (usually) parts of larger institutions designated as “sponsoring institutions” for the purpose of accreditation or “primary teaching sites” for the purpose of Medicare reimbursement. In 2011, there were approximately 679 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME)-accredited sponsoring institutions and over 1,135 ACGME-accredited primary teaching sites33.

For the purposes of this study, we focus on the workforce outcomes of these GME programs. We propose a method for measuring workforce-relevant outcomes of GME by sponsoring institutions and primary teaching sites, using existing data. We purposefully examine both. Sponsoring institutions, identified for accreditation purposes, assume the ultimate financial and academic responsibility for the GME program34. Primary teaching sites, generally hospitals, are the organizations directly receiving Medicare GME payments. Both sponsoring institutions and teaching sites often represent a consortium of academic institutions, hospitals, and ambulatory clinics that collectively take responsibility for residency training programs. Useful tracking systems with different emphases could be constructed using either sponsoring institutions or primary teaching sites.

Method

With approval from the Institutional Review Boards of the George Washington University and the American Academy of Family Physicians, the 2011 American Medical Association (AMA) Masterfile and its GME historical supplement were used to identify physicians completing residency between 2006 and 2008 (117,504 physicians). We selected a historical cohort to ensure that physicians had time to locate after training and to allow the AMA Masterfile to update their information. Given our focus on characterizing institutional and training site outcomes, we identified physicians who had completed more than one residency during this period and were represented more than once in our data set (8,977 physicians). We used the same AMA Masterfile to characterize these physicians 3-5 years after they had completed residency program in the study period in order to estimate primary care, general surgery, psychiatry, and ob-gyn output. In cases where physicians did training beyond their primary specialty, we used the specialty of their final training program as their practicing specialty. Primary care was defined as family medicine, general internal medicine, general pediatrics, internal medicine-pediatrics, internal medicine geriatrics, family medicine geriatrics. Ob-gyn data were not included in the primary care outcome but were reported separately.

We calculated general internal medicine retention as the number of general internal medicine graduates who did no further training beyond their primary residency divided by the number of all general internal medicine graduates at each sponsoring institution or primary teaching site (including those who completed subspecialty training). General surgery retention rates were similarly calculated.

We used AMA Masterfile addresses to determine physician location. We supplemented these data with information from the National Provider Identifier (NPI) database35 to improve the quality of practice addresses we found in the AMA Masterfile. Using unique combinations of name and address, we were able to match 97% of the physicians in the 2011 NPI with physicians in the Masterfile. We preferentially used the NPI physician address if the NPI update year was later than the last year of residency for an individual physician. As the cohort (2006-2008 graduates) was a relatively recent cohort, the NPI correction increased the likelihood of capturing current work addresses. We geocoded practice addresses to determine practice in a rural (non-metro) county and in a primary care Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA). Rural was defined using the U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural Urban Continuum Codes.36 The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Data Warehouse was used to identify HPSA geographies.37

We also matched our data with 2009 Medicare claims data to identify physicians working in a Federally Qualified Health Center (FQHC) or Rural Health Center (RHC). We used the AMA Masterfile - NPI match to link physicians with a unique physician identification number (UPIN) that we then matched to a 100% sample of 2009 FQHC and RHC Medicare claims files. Using this method, we identified 2,373 physicians who had at least one claim in an RHC or FQHC. Using data provided by HRSA38, we identified graduates who had ever participated in the National Health Service Corps (NHSC) using unique combinations of first name, last name, specialty, and birth year. We used Hospital Cost Reports (2008)39 to identify Medicare GME funding for hospitals.

The AMA Masterfile GME supplement assigns an “icode” to each residency program. The icode most often corresponds with the ACGME sponsor institution code, less frequently with the primary teaching site code. In all cases, we were able to uniquely assign individuals to sponsoring institutions. In cases where the icode matched to the sponsor code, we assigned primary teaching sites using 2011 data from the ACGME that identified all residency programs by specialty with their sponsoring institutions and primary teaching sites. This match raised some methodological challenges. It is possible for a single sponsoring institution's residency programs in different specialties to be situated in different primary teaching sites. To address this problem, we linked unique combinations of sponsoring institution and specialty in both the AMA Masterfile and the AGCME data. A second challenge was that residencies in the same specialty can be situated in two or more primary teaching sites. In these cases, we could not uniquely match a residency with a particular primary teaching institution. In the analysis file, we flagged these cases. Third, because we matched later (2011) ACGME lists of sponsoring and primary teaching sites with earlier (2006-2008) AMA information, we were unable to match programs that had closed or opened or changed their affiliation during the intervening period of time. Finally, some ACGME primary teaching site information was missing and we did not have institutional information for osteopathic or Canadian residency programs. We hand-edited non-matches when possible, using the internet to search for programs to determine if programs had closed, changed names, or changed affiliations; we called programs to confirm.

After hand-editing, we were able to find unique matches for 7,219 of the 8,810 unique sponsoring institution/specialty combinations. This corresponds to 101,304 of the 117,504 residents in our sample. Our inability to situate a resident in a primary teaching institution was mainly due to those cases where a sponsoring institution sponsored programs in the same specialty in multiple primary teaching sites (10,089 residents).

We used pairwise correlation analysis, weighted for the number of residents, to examine the relationships between institution-level primary care, IM retention, and rural outcomes with institutional characteristics, including number of specialties trained, rurality, percent female, percent osteopathic (in all allopathic residency programs), percent international medical graduate (IMG), and average age.

Results

Summary outcomes

Sponsoring institutions

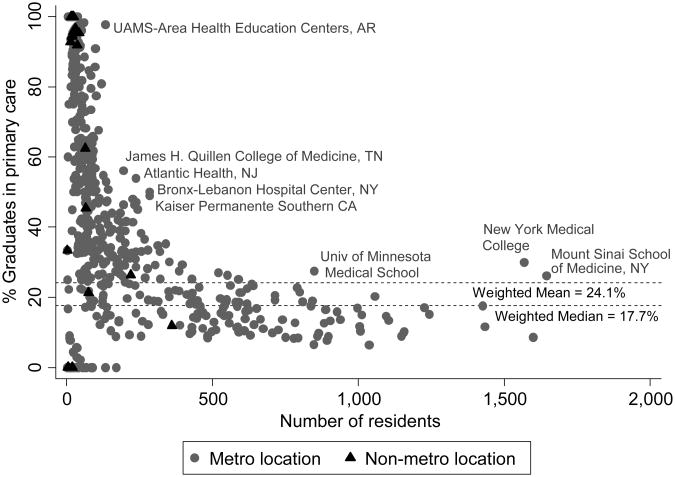

Table 1 provides summary outcome measures for sponsoring institutions and primary teaching sites. For the 2006–2008 period we identified 759 sponsoring institutions, whose weighted, mean percentage of graduates in primary care was 24.2%, median 17.7% (see Figure 1). Considering only unique individuals, the average rose to 25.2%; however, this over estimates primary care production, as we could not account for primary care physicians practicing as hospitalists. We found 158 institutions produced no primary care graduates, and 184 institutions produced more than 80%; the latter tended to be smaller institutions. For sponsoring institutions providing internal medicine training, retention in general internal medicine (GIM) ranged widely from 8.3% to 95.2% (limited to programs training at least the minimum required by the ACGME40 in one year and weighted for the number of GIM graduates). A total of 255 sponsoring institutions graduated general surgery residents between 2006 and 2008 with an average general surgery retention of 38.4% (weighted for the number of general surgery graduates). We identified 183 sponsoring institutions graduating psychiatry residents.

Table 1. Summary of U.S. Graduate Medical Education Outcome Measures for Residents Graduating in 2006–2008.

| Sponsoring Institutions | Primary Teaching Sites | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome measure* | No. of programs included in analyses | No. of programs with outcome > 0 | Mean (SD) | Median | Range | No. of programs included in analyses | No. of programs with outcome > 0 | Mean (SD) | Median | Range |

| % of Graduates in primary care (PC) | 759 | 601 | 24.17 (19.29) | 17.71 | 0–100 | 957 | 667 | 22.45 (21.83) | 14.96 | 0–100 |

| % of internal medicine (IM) Graduates retained in general IM | 343† | 357 | 37.88 (17.22) | 33.82 | 8.28– 95.24 | 299† | 305 | 38.43 (17.91) | 33.72 | 8.28– 95.24 |

| No. of graduates in general surgery (GS) | 759 | 264 | 14.25 (12.23) | 12 | 0–62 | 957 | 249 | 9.50 (9.02) | 9 | 0–47 |

| % of GS Graduates retained in GS | 255 | 248 | 38.42 (14.12) | 35.71 | 0–100 | 222 | 221 | 38.19 (14.26) | 25.44 | 0–100 |

| No. of graduates in psychiatry | 759 | 266 | 14.97 (13.42) | 14 | 0–64 | 957 | 271 | 9.22 (10.22) | 6 | 0–40 |

| % of Graduates practicing in Health Professional Shortage Areas‡ | 725 | 637 | 25.84 (14.11) | 21.95 | 0–100 | 937 | 823 | 25.91 (15.02) | 21.41 | 0–100 |

| % of Graduates practicing in rural areas‡ | 725 | 561 | 8.51 (9.05) | 6.33 | 0–100 | 937 | 682 | 8.33 (9.41) | 5.88 | 0–100 |

| No. of graduates practicing in Federally Qualified Health Centers | 759 | 430 | 5.39 (5.08) | 4 | 0–20 | 957 | 454 | 2.79 (2.85) | 2 | 0–20 |

| No. of graduates practicing in Rural Health Centers | 759 | 286 | 2.12 (2.79) | 1 | 0–27 | 957 | 281 | 1.13 (1.74) | 1 | 0–12 |

| No. of graduates practicing in the National Health Service Corps | 759 | 280 | 2.12 (2.27) | 2 | 0–11 | 957 | 291 | 1.23 (1.53) | 1 | 0–8 |

| No. of specialties | 759 | 759 | 39.35 (25.01) | 42 | 1–83 | 957 | 957 | 7.55 (12.48) | 2 | 1–71 |

All results are weighted for number of residents in a program, except % of Graduates retained in IM and % of Graduates retained in GS, which are weighted for number of IM or GS residents in a program, respectively, and No. of specialties, which is not weighted.

Limited to programs graduating 5 or more internal medicine residents in the 2006-2008 period.

Limited to physicians in direct patient care in the 2011 American Medical Association Masterfile.

Figure 1.

Relationship between percentage of graduates in primary care and number of residents trained in U.S. graduate medical education sponsoring institutions. Data are limited to sponsoring institutions with more than three graduates during 2006–2008. Puerto Rico institutions are not included.

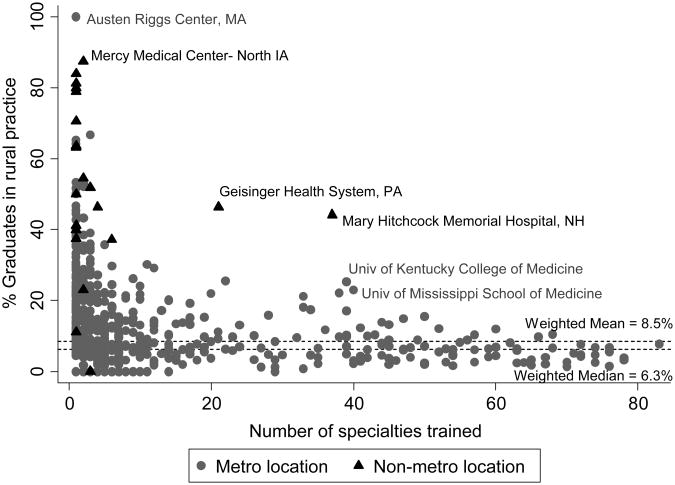

Overall, 198 institutions produced no rural physicians, 10 institutions had all graduates go to rural areas (weighted mean for all programs was 8.5% rural; median 6.3%). Considering only unique individuals, the average percentage of graduates providing direct patient care in rural areas was 4.8%. We found 283 institutions produced no physicians practicing in FQHCs or RHCs; 479 institutions produced no NHSC physicians.

Primary teaching sites

We identified 957 primary teaching sites for the 2006-2008 period. Of the 117,504 physicians in our study, we were unable to uniquely assign 16,200 individuals to primary teaching sites (13.8%), and 99 primary teaching sites had incomplete data due to sponsoring institutions sponsoring multiple same-specialty GME programs in different primary teaching sites. In 63 of the 99 primary teaching sites, residents who could not be uniquely associated with those sites included residents in primary care fields, most commonly family medicine and internal medicine.

Program-level outcomes

We compared program-level outcomes for the 161 sponsoring institutions producing more than 200 graduates per year—more than three-fourths of all residents (90,217). Table 2 shows the bottom and top 20 primary care producers. These institutions had an average of 40 training programs (SD = 20). This group of larger training institutions could similarly have been ranked on production of rural physicians, which ranged from none to 61.2%, or on other measures.

Table 2. Correlation Analysis of Graduate Medical Education Outcome Measures for Sponsoring Institutions*.

| Outcome measures | % of Graduates in primary care | % of Graduates retained in internal medicine (IM) | % of Graduates practicing in rural areas | No. of specialties trained at sponsoring institution | Rurality of sponsoring institution† | % Female graduates | % DO graduates | %International medical graduates (IMG) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % of Graduates retained in IM | 0.751‡ (364) | |||||||

| % of Graduates practicing in rural areas | 0.409‡ (759) | 0.252‡ (364) | ||||||

| No. of specialties trained at sponsoring institution | −0.631‡ (759) | −0.567‡ (364) | −0.331‡ (745) | |||||

| Rurality of Sponsoring institution | 0.205‡ (759) | 0.047 (356) | 0.608‡ (745) | −0.158‡ (745) | ||||

| % Female graduates | 0.217‡ 759 | 0.021 (364) | −0.116‡ (759) | −0.050 (759) | −0.207‡ (745) | |||

| % DO graduates | 0.335‡ (759) | 0.202‡ (364) | 0.175‡ (759) | −0.387‡ (759) | 165‡ (745) | −0.089§ (759) | ||

| % IMG | 0416‡ (759) | 0424‡ (364) | 0142‡ (759) | −0.398‡ (759) | 0.010 (745) | −0.020 (759) | −0.008 (759) | |

| Mean age | 0.278‡ (759) | 0.335‡ (364) | 0.157‡ (759) | 0.143‡ (759) | 44‡ (745) | −0.119‡ (759) | 0.092§ (759) | 447‡ (759) |

No. of valid observations reported in parentheses.

Rurality determined by U.S. Department of Agriculture Rural-Urban Continuum Code (coded 1-9; rurality increases with increasing number). See: United State Department of Agriculture. Measuring rurality: Rural-urban continuum codes. (http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/Rurality/RuralUrbCon/). 2004. Accessed April 22, 2013.

P < .01.

P < .05.

For primary teaching sites, 158 sites produced more than 150 graduates between 2006 and 2008, collectively training 60.8% (61,632) of graduates that can be assigned to primary teaching sites. Table 3 shows the top and bottom primary care producers, excluding primary teaching sites for which we were unable to uniquely assign all residents to that site. The top 20 primary care producing sites graduated 1,658 primary care graduates out of a total of 4,044 graduates (41.0%) and received $292.1 million in total Medicare GME payments ($72,230 per resident). The bottom 20 graduated 684 primary care graduates out of a total of 10,937 graduates (6.3%) and received $842.4 million ($77,004 per resident).

Full sponsoring institution and primary teaching site outcomes are available at www.graham-center.org/gmemapper [[LWW: insert hyperlink]].

Associations

There was a negative relationship between the number of specialties trained and graduates practicing in rural areas (see Figure 2). Increasing rurality of a sponsoring institution was associated with increasing rural output. The evaluation of relationships identified outliers. For example, despite training more than 20 different specialties, we found more than 40% of Geisinger Health System and Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital graduates to be practicing in rural areas. Both institutions are located in non-metropolitan areas. This example points to the need for further analysis that could be done using program-level outcomes. Correlation analysis suggests positive associations between percent primary care output and percent internal medicine residents retained in primary care, percent rural output, rurality of the program, percent female, percent osteopathic graduates, percent international medical graduates, and mean age. We also observed positive correlations between percent rural output and rurality of the program, percent internal medicine residents retained in primary care, percent osteopathic graduates, percent international medical graduates, and mean age. We found negative associations between percent primary care output and number of specialties trained, and between percent rural output and number of specialties trained and percent female. Table 4 provides correlation analysis.

Figure 2.

Relationship between percentage of graduates practicing in rural areas and number of specialties trained at U.S. graduate medical education sponsoring institutions. Data are limited to sponsoring institutions with more than three graduates during 2006–2008. Puerto Rico institutions are not included.

Discussion

GME accountability

In public policy discussions, Medicare GME funding is being targeted simultaneously for reduction and for increased accountability, highlighting a need for recipient organizations to be able to measure relevant outcomes of their GME expenditures. This analysis demonstrates that outcomes can be measured for all Medicare sponsoring institutions and approximately 90% of ACGME primary teaching sites, demonstrating outcome measures are possible for GME training.

Additionally, it provides perspective to policy-makers and educators by allowing direct comparisons between GME training institutions similar in size and scope, and allowing identification of institutions that have achieved particular success in producing physicians in primary care and geographically underserved areas despite prevailing trends. Given critical health workforce needs that may vary at national, state, and local levels, a better understanding of outputs at the institution level will allow educators and local, regional, and national policy-makers to assess the performance of programs relative to local and national workforce needs, and focus interventions and policies for improvement. This analytic approach can also be used to look at any number of specialty and geographic outcomes.

GME outcomes

Beyond demonstrating a method to measure GME outcomes, some findings bear comment. Primary care physician production of 25.2% and rural physician production of 4.8% will not sustain the current workforce, solve problems of maldistribution, or address acknowledged shortages. The relatively small number of physicians choosing to work in RHCs, FQHCs, HPSAs, and the NHSC will not support a doubling of the capacity of safety net services envisioned by the Affordable Care Act.41

Past GME policies have often relied on proxies, such as choice of residency specialty or statements of intent to practice in rural or shortage areas, for measuring institutional production of physicians in primary care and underserved areas. However, a substantial portion of internal medicine and general surgery graduates subsequently subspecialize. The results reported here show some institutions retain fewer than 10% of their internal medicine residents in primary care. Actual outcomes will enable much higher precision in designing institutional, regional and national workforce training policies. While these findings represent a cross section of GME graduates, these measures can be repeated on an ongoing basis with the potential to monitor trends, target limited resources, and prioritize institutions producing physicians in high-need specialties. These measures also have potential use in evaluating GME demonstration projects and the long-term impact of GME policy changes.

Evaluating relationships between various institutional characteristics and outcomes in high-need specialties and underserved areas also provides an opportunity to identify outliers. For example, rural physician production and retention of internal medicine residents in primary care are negatively associated with training larger numbers of specialties; however, some programs appear to defy the trends. Geisinger Health System and Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital both train more than 20 different specialties, yet more than 40% of their graduates practice in rural areas. Wright State University School of Medicine, Madigan Healthcare System and the National Capital Consortium train in more than 15 different specialties, yet retain more than 60% of their internal medicine residents in GIM. The ability to identify these outliers allows further study of the factors that contribute to their success.

Training patterns

It is not surprising that large teaching hospitals and academic health centers train sizable numbers of subspecialists. Conspicuous, however, is that the magnitude and consistency of these numbers, relative to primary care graduates, across these institutions is striking. This bifurcation of outcomes invites the conclusion that institutions with more subspecialty training programs are inclement for the production of primary care. Do residents choose large teaching hospitals for the subspecialty opportunities available or does the environment of the multiple specialties influence the subsequent training choices of generalist trainees – or both? The low primary care output observed in specialty-rich training institutions is reinforced by the current Medicare GME formulae that result in higher payments to those large institutions, as well the ability of more specialized GME programs to support generally more highly reimbursed services. These are important questions to consider in the national discussion about imbalance in the workforce and strategies to increase primary care physician output.

A similar pattern emerges with regard to rural physicians whose training sites are predominantly in institutions with fewer specialties. Yet, there are academic health centers with substantial numbers of training programs graduating significant numbers into rural practice. Geisinger Health System and Mary Hitchcock Medical Center are located in less urban areas and train using local facilities. While major medical centers are not often based in rural areas, the pattern of graduates in the general analysis and the success of these two programs in rural health staffing suggest that targeted funding for rurally based residencies in small or large residency programs offers a strategy for augmenting the rural physician workforce.

Limitations

The AMA Masterfile presents known limitations in accuracy; however, the GME supplement is generally more accurate due to how these data are collected. Concerns exist regarding specialty and practice self-designation by physicians, address inaccuracies, and delays in information updating.42-44 When possible, we addressed these issues by correcting specialties when residency training information suggested more recent training in a different field. We preferentially used secondary addresses when the primary address was a home address and also used NPI addresses when the NPI update year was more recent than the last year of residency training.

The inability to uniquely associate approximately 16,000 individuals to primary teaching sites produced incomplete primary teaching site outcomes. In reporting program level outcomes for primary teaching sites we indicate those programs at which we are unable to uniquely assign all graduates.

Further, the ACGME database only allowed identification of primary teaching sites. Primary teaching sites do not represent all teaching hospitals. In 2008, an additional 460 hospitals received Medicare GME payments according to CMS hospital cost reports. These are likely secondary teaching sites and represent a relatively small portion of the total Medicare spending on GME – approximately $706 million (7.6%) of $9.3 billion. However, to implement an accountability system using our findings, these hospitals would need to identify either their sponsoring institution or primary teaching site affiliations for their residency training programs.

Our study also largely excludes those physicians trained in osteopathic residency programs. Due to the separation of the accreditation processes between the allopathic and osteopathic medical school and GME systems, the AMA Masterfile has an increased delay in capturing individuals trained purely in the osteopathic pathway. In the future, these individuals may be added to the analysis by collaborating with the American Osteopathic Association who maintains a similar database to the AMA Masterfile.

Conclusions

Medicare GME financing is the largest public investment in health care workforce development in the nation, with two-thirds of nearly $10 billion in annual funding going to the 200 hospitals training the largest number of residents. Despite this funding, the physician workforce continues to face critical shortages in specific specialties and locations, most of which are minimally served by the graduates of those 200 hospitals. As a result, Medicare GME-funded institutions face increasing scrutiny and calls for greater accountability. Our findings demonstrate outcome measures in key workforce areas at the institution and hospital level are achievable. These outcomes can be used to develop an accountability system, inform policy and education, and evaluate the results of changes in the GME system.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Chen would like to thank Dr. Marion Danis in the Department of Clinical Bioethics in the Clinical Center of the National Institutes of Health for acting as her intramural mentor for her DREAM Award. The authors are also grateful for the input of key stakeholders who participated in a qualitative study that informed the outcome measures used in this study.

Funding/Support: The Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation supported this work. Dr. Chen is supported through a DREAM Award by the National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities, National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Appendix 1.

Outcomes of the Top and Bottom Producers of Primary Care Graduates, U.S. Graduate Medical Education Sponsoring Institutions with More Than 200 Graduates Between 2006-2008.

| Sponsoring institution | Location | Total no. of graduates |

No. of specialties trained |

No. (%) in primary care |

% Retained in general internal medicine |

No. in general surgery |

No. in psychiatry |

No. in OB/gyn |

No. in an HPSA*† |

No. in a rural area*† |

No. in an FQHC* |

No. in an RHC* |

No. in the NHSC* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top producers of primary care graduates | |||||||||||||

| 1. University of Nevada School of Medicine | Reno, NV | 239 | 11 | 129 (54.0) | 56.64 | 8 | 18 | 11 | 42 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| 2. Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center | Bronx, NY | 286 | 12 | 143 (50.0) | 75.25 | 16 | 8 | 14 | 47 | 19 | 20 | 4 | 1 |

| 3. Kaiser Permanente Southern California | Los Angeles, CA | 286 | 16 | 140 (49.0) | 37.25 | 8 | 1 | 15 | 21 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 4. Brooklyn Hospital Center | Brooklyn, NY | 227 | 9 | 109 (48.0) | 57.14 | 15 | 1 | 13 | 35 | 14 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 5. James H Quillen College of Medicine | Johnson City, TN | 240 | 12 | 113 (47.1) | 37.50 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 47 | 40 | 14 | 5 | 1 |

| 6. University of Kansas School of Medicine (Wichita) | Wichita, KS | 233 | 11 | 108 (46.4) | 45.45 | 14 | 12 | 15 | 83 | 46 | 4 | 27 | 3 |

| 7. Atlantic Health | Florham Park, NJ | 244 | 10 | 110 (45.1) | 55.10 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 6 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| 8. UCSF Fresno Medical Education Program | Fresno, CA | 206 | 9 | 86 (41.8) | 35.06 | 9 | 15 | 8 | 25 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 1 |

| 9. Advocate Lutheran General Hospital | Park Ridge, IL | 205 | 11 | 85 (41.5) | 34.04 | 0 | 7 | 9 | 18 | 5 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 10. Kaiser Permanente Med Group | Oakland, CA | 227 | 4 | 94 (41.4) | 46.47 | 0 | 1 | 32 | 9 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 11. University of Illinois College of Medicine at Peoria | Peoria, IL | 201 | 13 | 78 (38.8) | 28.85 | 7 | 0 | 7 | 75 | 20 | 4 | 7 | 2 |

| 12. New York Methodist Hospital | Brooklyn, NY | 256 | 14 | 98 (38.3) | 47.58 | 10 | 0 | 12 | 25 | 7 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 13. Southern Illinois Univ School Of Medicine | Springfield, IL | 268 | 22 | 98 (36.6) | 22.39 | 2 | 7 | 11 | 72 | 43 | 14 | 14 | 3 |

| 14. Long Island College Hospital | Brooklyn, NY | 203 | 7 | 72 (35.5) | 37.74 | 0 | 1 | 11 | 20 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 15. Wright State University School of Medicine | Dayton, OH | 340 | 18 | 120 (35.3) | 70.33 | 25 | 21 | 19 | 67 | 18 | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| 16. Eastern Virginia Medical School | Norfolk, VA | 313 | 24 | 109 (34.8) | 39.68 | 5 | 12 | 12 | 31 | 26 | 4 | 0 | 3 |

| Grand Rapids Medical Education Partners | Grand Rapids, MI | 278 | 14 | 93 (33.5) | 82.35 | 14 | 0 | 25 | 40 | 19 | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| 18. Brookdale Univ Hospital and Medical Center | Brooklyn, NY | 257 | 10 | 85 (33.1) | 59.38 | 9 | 11 | 15 | 54 | 12 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| 19. Good Samaritan Regional Med Center | Phoenix, AZ | 239 | 15 | 79 (33.1) | 47.25 | 10 | 10 | 21 | 59 | 7 | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| 20. Pitt County Memorial Hospital | Greenville, NC | 321 | 28 | 106 (33.0) | 51.79 | 4 | 14 | 16 | 51 | 31 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| Bottom producers of primary care graduates | |||||||||||||

| 142. Henry Ford Hospital | Detroit, MI | 591 | 42 | 60 (10.2) | 30.09 | 10 | 14 | 12 | 44 | 21 | 3 | 4 | 0 |

| 143. University of Texas Southwestern Medical School | Dallas, TX | 1,157 | 76 | 116 (10.0) | 20.79 | 18 | 23 | 55 | 95 | 31 | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| 144. Thomas Jefferson University Hospital | Philadelphia, PA | 705 | 54 | 70 (9.9) | 21.99 | 12 | 19 | 29 | 38 | 6 | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 145. Yale-New Haven Hospital | New Haven, CT | 865 | 67 | 84 (9.7) | 24.75 | 12 | 34 | 22 | 142 | 14 | 8 | 1 | 3 |

| 146. Children's Hospital | Boston, MA | 423 | 29 | 41 (9.7) | N/A | 0 | 0 | 0 | 75 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 147. Ochsner Clinic Foundation | New Orleans, LA | 215 | 17 | 20 (9.3) | 25.76 | 5 | 0 | 11 | 40 | 17 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 148. Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center | Boston, MA | 631 | 35 | 58 (9.2) | 19.37 | 17 | 3 | 15 | 95 | 5 | 8 | 0 | 2 |

| 149. University Hospital Inc | Cincinnati, OH | 485 | 48 | 44 (9.1) | 29.41 | 11 | 10 | 23 | 44 | 20 | 8 | 3 | 1 |

| 150. Naval Medical Center (San Diego) | San Diego, CA | 256 | 21 | 23 (9.0) | 66.67 | 39 | 14 | 20 | 83 | 14 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 151. Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine | Baltimore, MD | 1,148 | 76 | 103 (9.0) | 20.55 | 19 | 28 | 26 | 162 | 6 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 152. Duke University Hospital | Durham, NC | 861 | 71 | 77 (8.9) | 15.48 | 10 | 22 | 23 | 62 | 21 | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| 153. University of Pennsylvania Health System | Philadelphia, PA | 898 | 63 | 79 (8.8) | 22.86 | 17 | 26 | 19 | 38 | 9 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| 154. New York Presbyterian Hospital | New York, NY | 1,599 | 70 | 137 (8.6) | 19.67 | 33 | 53 | 33 | 125 | 7 | 9 | 2 | 3 |

| 155. Cleveland Clinic Foundation | Cleveland, OH | 752 | 54 | 64 (8.5) | 30.47 | 31 | 14 | 1 | 132 | 16 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 156. Temple University | Philadelphia, PA | 484 | 34 | 41 (8.5) | 25.81 | 7 | 10 | 15 | 21 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Hospital | |||||||||||||

| 157. Vanderbilt University Med Center | Nashville, TN | 793 | 59 | 67 (8.5) | 13.22 | 30 | 15 | 20 | 67 | 15 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| 158. Stanford Hospital and Clinics | Palo Alto, CA | 781 | 70 | 65 (8.3) | 23.81 | 9 | 27 | 11 | 44 | 10 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| 159. Brigham and Women's Hospital | Boston, MA | 893 | 45 | 69 (7.7) | 25.37 | 19 | 28 | 30 | 109 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 160. Massachusetts General Hospital | Boston, MA | 848 | 44 | 55 (6.5) | 15.93 | 11 | 37 | 0 | 120 | 11 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 161. Washington Univ/B-JH/SLCH Consortium | Saint Louis, MO | 1,038 | 72 | 66 (6.4) | 8.28 | 10 | 22 | 24 | 161 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

HPSA = Health Professional Shortage Area; FQHC = Federally Qualified Health Center; RHC = Rural Health Center; NHSC = National Health Service Corps.

Limited to individuals in direct patient care in the 2011 American Medical Association Masterfile.

Appendix 2.

Characteristics of the Top and Bottom Producers of Primary Care Graduates, U.S. Graduate Medical Education (GME) Primary Teaching Sites with More than 150 Graduates Between 2006-2008.

| Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) primary teaching site name | Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) provider number | Location | CMS provider number duplicates† | No. of hospital bed(2008)† | Medicare GME payments received (2008)† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top producers of primary care graduates | |||||

| 1. Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center | 330080 | Bronx, NY | 0 | 302 | $17,179,828 |

| 2. Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center | 330009 | Bronx, NY | 0 | 481 | $23,733,028 |

| 3. Nationwide Children's Hospital | 363305 | Columbus, OH | 0 | 410 | $85,645 |

| 4. Brooklyn Hospital Center | 330056 | Brooklyn, NY | 0 | 364 | $27,509,848 |

| 5. University Medical Center of El Paso | 450024 | El Paso, TX | 1 | 269 | $5,553,256 |

| 6. John Peter Smith Hospital (Tarrant County Hosp District) | 450039 | Fort Worth, TX | 0 | 408 | $4,553,886 |

| 7. Riley Hospital for Children at Indiana University Health | N/A‡ | Indianapolis, IN | 0 | ||

| 8. St Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center | 30024 | Phoenix, AZ | 1 | 615 | $10,771,564 |

| 9. Advocate Lutheran General Hospital | 140223 | Park Ridge, IL | 0 | 490 | $23,213,696 |

| 10. Advocate Christ Medical Center | 140208 | Oak Lawn, IL | 0 | 591 | $35,666,904 |

| 11. Harlem Hospital Center | 330240 | New York, NY | 0 | 221 | $12,423,069 |

| 12. Children's Hospital of Michigan | 233300 | Detroit, MI | 0 | 211 | $133,472 |

| 13. Miami Valley Hospital | 360051 | Dayton, OH | 0 | 630 | $12,372,810 |

| 14. Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital | 490024 | Roanoke, VA | 0 | 696 | $14,610,493 |

| 15. Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center | 30002 | Phoenix, AZ | 0 | 558 | $15,792,211 |

| 16. Palmetto Health Richland | 420018 | Columbia, SC | 0 | 606 | $11,730,481 |

| 17. Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center | 330233 | Brooklyn, NY | 0 | 446 | $22,368,976 |

| 18. Children's Hospital of Wisconsin | 523300 | Milwaukee, WI | 0 | 236 | $35,374 |

| 19. Pitt County Memorial Hospital | 340040 | Greenville, NC | 1 | 618 | $30,479,116 |

| 20. University of Tennessee Memorial Hospital | 440015 | Knoxville, TN | 0 | 513 | $23,894,986 |

| Bottom producers of primary care graduates | |||||

| 138. Duke University Hospital | 340030 | Durham, NC | 0 | 783 | $58,542,408 |

| 139. Northwestern Memorial Hospital | 140281 | Chicago, IL | 0 | 819 | $29,946,880 |

| 140. Baylor University Medical Center | 450021 | Dallas, TX | 0 | 856 | $14,391,194 |

| 141. Vanderbilt University Medical Center | 440039 | Nashville, TN | 0 | 725 | $41,585,176 |

| 142. Medical Center of Louisiana at New Orleans | 190005 | New Orleans, LA | 0 | 202 | $5,790,103 |

| 143. Cleveland Clinic Foundation | 360180 | Cleveland, OH | 0 | 1,083 | $73,565,216 |

| 145. Brigham and Women's Hospital | 220110 | Boston, MA | 0 | 750 | $61,175,680 |

| 146. Temple University Hospital | 390027 | Philadelphia, PA | 1 | 596 | $29,359,426 |

| 147. Thomas Jefferson University Hospital | 390174 | Philadelphia, PA | 0 | 811 | $72,987,688 |

| 148. Tulane University Hospital and Clinics | 190176 | New Orleans, LA | 1 | 279 | $11,098,661 |

| 149. University of Chicago Medical Center | 140088 | Chicago, IL | 1 | 571 | $36,772,172 |

| 150. Massachusetts General Hospital | 220071 | Boston, MA | 0 | 883 | $77,197,552 |

| 151. Stanford Hospital and Clinics | 50441 | Palo Alto, CA | 0 | 436 | $60,190,088 |

| 152. Johns Hopkins Hospital | 210009 | Baltimore, MD | 0 | 924 | $52,406,516 |

| 153. Barnes-Jewish Hospital | 260032 | Saint Louis, MO | 0 | 1,167 | $67,630,928 |

| 154. Harper-Hutzel Hospital | 230104 | Detroit, MI | 0 | 406 | $27,470,668 |

| 155. Indiana University Health University Hospital | 150056 | Indianapolis, IN | 2 | 1,405 | $43,707,992 |

| 156. NYU Hospitals Center | 330214 | New York, NY | 1 | 602 | $55,463,648 |

| 157. Mayo Clinic (Rochester) | 240061 | Rochester, NY | 1 | 336 | $17,149,348 |

| 158. Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center | 330154 | New York, NY | 0 | 433 | $5,959,722 |

Limited to ACGME primary teaching sites where all primary care residency programs can be uniquely affiliated with Sponsoring Institutions.

CMS provider number duplicates may represent one hospital with multiple ACGME primary teaching site codes or multiple hospitals that bill under one provider number. Hospital beds and Medicare GME funding received will therefore reflect total beds and GME payments for all hospitals with a particular provider number.

Children's hospital receiving no Medicare GME payments. Children's hospital GME training is supported through the Health Resources and Services Agency Children's Hospital GME program.

Appendix 3.

Outcomes of the Top and Bottom Producers of Primary Care Graduates, U.S. Graduate Medical Education Primary Teaching Sites with More than 150 Graduates Between 2006–2008.

| Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education primary teaching site name (ACGME) | Total no. of graduates |

No. of specialties trained |

No. (%) in primary care |

No. in general surgery |

No. in psychiatry |

No. in OB/gyn |

No (%) in an HPSA*† |

No. (%) in a rural area† |

No. in an FQHC* |

No. in an RHC* |

No. in the NHSC* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Top producers of primary care graduates | |||||||||||

| 1. Lincoln Medical and Mental Health Center | 195 | 6 | 110 (56.41) | 1 | 6 | 12 | 37 (36.63) | 14 (13.86) | 7 | 2 | 0 |

| 2. Bronx-Lebanon Hospital Center | 261 | 11 | 140 (53.64) | 0 | 8 | 14 | 45 (34.88) | 19 (14.73) | 20 | 4 | 1 |

| 3. Nationwide Children's Hospital | 172 | 19 | 85 (49.42) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12 (14.81) | 8 (9.88) | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| 4. Brooklyn Hospital Center | 227 | 9 | 109 (48.02) | 15 | 1 | 13 | 35 (27.56) | 14 (11.02) | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 5. University Medical Center of El Paso | 165 | 7 | 74 (44.85) | 5 | 1 | 14 | 56 (56.00) | 7 (7.00) | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| 6. John Peter Smith Hospital (Tarrant County Hosp District) | 156 | 7 | 69 (44.23) | 0 | 12 | 13 | 23 (22.33) | 22 (21.36) | 5 | 11 | 3 |

| 7. Riley Hospital for Children at Indiana University Health | 171 | 19 | 74 (43.27) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 14 (12.96) | 12 (11.11) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 8. St Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center | 188 | 11 | 78 (41.49) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 26 (32.10) | 2 (2.47) | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| 9. Advocate Lutheran General Hospital | 199 | 10 | 79 (39.70) | 0 | 7 | 9 | 17 (16.83) | 5 (4.95) | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| 10. Advocate Christ Medical Center | 309 | 6 | 122 (39.48) | 1 | 0 | 0 | 43 (26.22) | 4 (2.44) | 6 | 0 | 3 |

| 11. Harlem Hospital Center | 182 | 10 | 71 (39.01) | 15 | 9 | 0 | 36 (46.15) | 17 (21.79) | 6 | 2 | 0 |

| 12. Children's Hospital of Michigan | 173 | 19 | 67 (38.73) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (16.67) | 4 (6.06) | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 13. Miami Valley Hospital | 173 | 5 | 66 (38.15) | 25 | 0 | 19 | 37 (34.58) | 6 (5.61) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 14. Carilion Roanoke Memorial Hospital | 174 | 8 | 65 (37.36) | 8 | 1 | 12 | 11 (15.07) | 14 (19.18) | 6 | 2 | 2 |

| 15. Banner Good Samaritan Medical Center | 217 | 12 | 79 (36.41) | 10 | 10 | 21 | 47 (37.60) | 7 (5.60) | 1 | 4 | 4 |

| 16. Palmetto Health Richland | 202 | 15 | 73 (36.14) | 6 | 6 | 11 | 27 (21.60) | 19 (15.20) | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| 17. Brookdale University Hospital and Medical Center | 241 | 9 | 85 (35.27) | 9 | 11 | 0 | 50 (44.64) | 9 (8.04) | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| 18. Children's Hospital of Wisconsin | 152 | 16 | 51 (33.55) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 13 (16.25) | 2 (2.50) | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| 19. Pitt County Memorial Hospital | 299 | 23 | 99 (33.11) | 4 | 14 | 16 | 47 (26.11) | 28 (15.56) | 4 | 2 | 2 |

| 20. University of Tennessee Memorial Hospital | 188 | 14 | 62 (32.98) | 14 | 0 | 10 | 41 (35.65) | 23 (20.00) | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Bottom producers of primary care graduates | |||||||||||

| 138. Duke University Hospital | 861 | 71 | 77 (8.94) | 10 | 22 | 23 | 62 (14.94) | 21 (5.06) | 5 | 2 | 0 |

| 139. Northwestern Memorial Hospital | 722 | 39 | 64 (8.86) | 13 | 18 | 28 | 38 (12.88) | 6 (2.03) | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| 140. Baylor University Medical Center | 170 | 16 | 15 (8.82) | 23 | 1 | 12 | 11 (9.73) | 7 (6.19) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 141. Vanderbilt University Medical Center | 775 | 55 | 67 (8.65) | 30 | 15 | 20 | 66 (18.03) | 15 (4.1) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 142. Medical Center of Louisiana at New Orleans | 375 | 27 | 32 (8.53) | 27 | 25 | 25 | 83 (44.39) | 16 (8.56) | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| 143. Cleveland Clinic Foundation | 761 | 55 | 64 (8.41) | 31 | 14 | 1 | 135 (37.5) | 16 (4.44) | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| 145. Brigham and Women's Hospital | 844 | 40 | 69 (8.18) | 19 | 28 | 30 | 103 (40.71) | 5 (1.98) | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| 146. Temple University Hospital | 429 | 27 | 34 (7.93) | 7 | 1 | 15 | 19 (10.86) | 8 (4.57) | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| 147. Thomas Jefferson University Hospital | 515 | 43 | 37 (7.18) | 12 | 18 | 29 | 30 (10) | 4 (1.33) | 6 | 1 | 1 |

| 148. Tulane University Hospital and Clinics | 382 | 31 | 27 (7.07) | 11 | 8 | 23 | 68 (38.2) | 19 (10.67) | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| 149. University of Chicago Medical Center | 523 | 44 | 35 (6.69) | 9 | 10 | 17 | 64 (31.84) | 5 (2.49) | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| 150. Massachusetts General Hospital | 842 | 42 | 55 (6.53) | 11 | 37 | 0 | 119 (48.57) | 10 (4.08) | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| 151. Stanford Hospital and Clinics | 623 | 49 | 29 (4.65) | 9 | 27 | 11 | 35 (11.74) | 10 (3.36) | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| 152. Johns Hopkins Hospital | 848 | 70 | 39 (4.6) | 19 | 27 | 26 | 137 (39.83) | 5 (1.45) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| 153. Barnes-Jewish Hospital | 848 | 50 | 30 (3.54) | 10 | 22 | 24 | 129 (33.33) | 14 (3.62) | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| 154. Harper-Hutzel Hospital | 244 | 17 | 5 (2.05) | 16 | 1 | 33 | 22 (16.06) | 12 (8.76) | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 155. Indiana University Health University Hospital | 411 | 27 | 3 (0.73) | 12 | 0 | 28 | 50 (15.97) | 19 (6.07) | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| 156. NYU Hospitals Center | 352 | 29 | 2 (0.57) | 18 | 0 | 31 | 20 (17.39) | 4 (3.48) | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| 157. Mayo Clinic (Rochester) | 243 | 30 | 0 (0) | ‡ | 0 | 0 | 29 (17.9) | 11 (6.79) | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| 158. Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center | 169 | 10 | 0 (0) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 (14.55) | 1 (1.82) | 1 | 0 | 0 |

HPSA = Health Professional Shortage Area; FQHC = Federally Qualified Health Center; RHC = Rural Health Clinic; NHSC = National Health Service Corps.

HPSA and Rural area outcomes are limited to individuals in direct patient care in the 2011 American Medical Association Masterfile.

Trains general surgery residents but unable to uniquely identify individuals to the primary teaching site due to multiple general surgery programs at one sponsoring institution

Footnotes

Other disclosures: None.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the George Washington University and the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Previous presentations: Limited findings from this study were presented at the 2012 Association of American Medical Colleges Physician Workforce Research Conference and at the Beyond Flexner Social Mission in Medical Education Conference in May, 2012.

Disclaimers: The views expressed by Dr. Chen do not represent those of the NIH or the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The information and opinions contained in research from the Graham Center do not necessarily reflect the views or policy of the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Dr. Candice Chen, National Institute for Minority Health and Health Disparities, and an assistant research professor, Department of Health Policy, The George Washington University.

Dr. Stephen Petterson, the Robert Graham Center.

Dr. Robert L. Phillips, Research and Policy, American Board of Family Medicine.

Dr. Fitzhugh Mullan, Medicine and Health Policy, Department of Health Policy, The George Washington University.

Dr. Andrew Bazemore, the Robert Graham Center.

Ms. Sarah D. O'Donnell, Department of Health Policy, The George Washington University.

References

- 1.Dorner FH, Burr RM, Tucker SL. The geographic relationships between physicians' residency sites and the locations of their first practices. Acad Med. 1991;66:540–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seifer SD, Vranizan K, Grumbach K. Graduate medical education and physician practice location. JAMA. 1995;274:685–691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steele MT, Schwab RA, McNamara RM, Watson WA. Emergency medicine resident choice of practice location. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;31:351–357. doi: 10.1016/s0196-0644(98)70346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pathman DE, Steiner BD, Jones BD, Konrad TR. Preparing and retaining rural physicians through medical education. Acad Med. 1999;74:810–820. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199907000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks RG, Walsh M, Mardon RE, Lewis M, Clawson AM. The roles of nature and nurture in the recruitment and retention of primary care physicians in rural areas: A review of the literature. Acad Med. 2002;77:790–798. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200208000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Morris CG, Johnson B, Kim S, Chen F. Training family physicians in community health centers: A health workforce solution. Fam Med. 2008;40:271–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reese VF, McCann JL, Bazemore AW, Phillips RL. Residency footprints: Assessing the impact of training programs on the local physician workforce and communities. Fam Med. 2008;40:339–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed May 1, 2013];Hospital Cost Reports. 2009 https://www.cms.gov/costreports/02_hospitalcostreport.asp.

- 9.Henderson TM. Medicaid direct and indirect graduate medical education payments: a 50-state survey. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2010. [Accessed May 1, 2013]. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/Medicaid%20Direct_Indirect%20GME%20Payments%20Survey%202010.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wynn B, Guarino C, Morse L, Cho M. Alternative ways of financing graduate medical education. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Health; 2006. [Accessed May 1, 2013]. http://aspe.dhhs.gov/health/reports/06/AltGradMedicalEdu/report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper RA, Getzen TE, McKee HJ, Laud P. Economic and demographic trends signal an impending physician shortage. Health Aff. 2002;21:140–154. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.21.1.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doescher MP, Fordyce MA, Skillman SM, Jackson JE, Rosenblatt RA. Persistent Primary Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) and Health Care Access in Rural America. Seattle, WA: WWAMI Rural Health Research Center; 2009. [Accessed May 1, 2013]. http://depts.washington.edu/uwrhrc/uploads/Persistent_HPSAs_PB.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams TE, Satiani B, Thomas A, Ellison EC. The impending shortage and the estimated cost of training the future surgical workforce. Ann Surg. 2009;250:590–597. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b6c90b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lynge DC, Larson EH, Thompson MJ, Rosenblatt RA, Hart LG. A longitudinal analysis of the general surgery workforce in the United States, 1981-2005. Arch Surg. 2008;143:345–351. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.143.4.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thomas CR, Holzer CE. The continuing shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45:1023–1031. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000225353.16831.5d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S Department of Health Services Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Health Professions. The Physician Workforce: Projections and Research into Current Issues Affecting Supply and Demand. Washington, DC: Health Resources and Services Administration; 2008. [Accessed May 1, 2013]. http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/healthworkforce/reports/physwfissues.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.U.S Department of Health Services Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Health Professions. Physician Supply and Demand: Projections to 2020. Washington, DC: Health Resources and Services Administration; 2006. [Accessed May 1, 2013]. http://www.achi.net/HCR%20Docs/2011HCRWorkforceResources/Physician%20Supply%20and%20Demand-2020%20kl.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Association of American Medical Colleges Center for Workforce Studies. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections through 2025. Washington DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2008. [Accessed May 1, 2013]. https://members.aamc.org/eweb/upload/The%20Complexities%20of%20Physician%20Supply.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang CH, Stukel TA, Flood AB, Goodman DC. Primary care physician workforce and Medicare beneficiaries' health outcomes. JAMA. 2011;305:2096–2104. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jerant A, Fenton JJ, Franks P. Primary care attributes and mortality: A national person-level study. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10:34–41. doi: 10.1370/afm.1314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83:457–502. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher ES, Wennberg DE, Stukel TA, Gottlieb DJ, Lucas FL, Pinder EL. The implications of regional variations in Medicare spending. Part 1: The content, quality, and accessibility of care. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:273–287. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-4-200302180-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coggeshall LT. Planning for Medical Progress Through Education. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Institute of Medicine. Primary care physicians: financing their graduate medical education in ambulatory settings. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine; 1989. [Accessed May 1, 2013]. http://iom.edu/Reports/1989/Primary-Care-Physicians-Financing-Their-Graduate-Medical-Education-in-Ambulatory-Settings.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Council on Graduate Medical Education. Advancing primary care. Washington DC: Health Resources and Services Administration; 2010. [Accessed may 1, 2013]. http://www.hrsa.gov/advisorycommittees/bhpradvisory/cogme/Reports/twentiethreport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation. Ensuring an effective physician workforce for America: Recommendations for an accountable graduate medical education system. New York, NY: Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation; 2011. [Accessed November May 1, 2013]. http://www.josiahmacyfoundation.org/docs/macy_pubs/Effective_Physician_Workforce_Conf_Book.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Aligning Incentives in Medicare. Washington DC: Medicare Payment and Advisory Commission; 2010. [Accessed May 1, 2013]. http://www.medpac.gov/documents/jun10_entirereport.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pub L No. 111-148,152.

- 29.Hofer AN, Abraham JM, Moscovice I. Expansion of Coverage under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act and Primary Care Utilization. Milbank Quarterly. 2011;89:69–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2011.00620.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kirch DG, Henderson MK, Dill M. Physician Workforce Projections in an Era of Health Care Reform. Annual Review of Medicine. 2012;63:435–445. doi: 10.1146/annurev-med-050310-134634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mullan F, Chen C, Petterson S, Kolsky G, Spagnola M. The Social Mission of Medical Education: Ranking the Schools. Ann Int Med. 2010;152:804–811. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brotherton SE, Etzel SI. Graduate Medical Education, 2010-2011. JAMA. 2011;306:1015–1030. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miller, RS. Senior Vice President of Applications and Data Analysis, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Personal communication with R. Phillips, April 6, 2011.

- 34.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. [Accessed May 1, 2013];Glossary of Terms. 2011 http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/ab_ACGMEglossary.pdf.

- 35.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed May 1, 2013];NPI Files. 2012 http://nppes.viva-it.com/NPI_Files.html.

- 36.United States Department of Agriculture. [Accessed May 1, 2103];Measuring rurality: Rural-urban continuum codes. 2004 http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/Rurality/RuralUrbCon/

- 37.Health Resources and Services Administration. [Accessed May 1, 2103];Data Warehouse. 2011 http://datawarehouse.hrsa.gov/

- 38.Berry M. Office of Shortage Designation, Health Resources and Services Administration. Personal communication with R. Phillips, September 2, 2010.

- 39.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Accessed May 1, 2013];Cost Reports by Fiscal Year. 2012 https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Files-for-Order/CostReports/Cost-Reports-by-Fiscal-Year.html.

- 40.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. [Accessed May 1, 2013];ACGME program requirements for graduate medical education in internal medicine. 2009 http://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/140_internal_medicine_07012009.pdf.

- 41.Geiger Gibson/RCHN Community Health Foundation Research Collaborative. [Accessed May 1, 2013];Policy Research Brief No 19: Strengthening Primary Care to Bend the Cost Curve: The Expansion of Community Health Center Through Health Reform. 2010 http://sphhs.gwu.edu/departments/healthpolicy/dhp_publications/pub_uploads/dhpPublication_895A7FC0-5056-9D20-3DDB8A6567031078.pdf.

- 42.Freed GL, Nahra TA, Wheeler JR Research Advisory Committee of American Board of Pediatrics. Counting physicians: Inconsistencies in a commonly used source for workforce analysis. Acad Med. 2006;81:847–852. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200609000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Grumbach K, Becker SH, Osborn EH, Bindman AB. The challenge of defining and counting generalist physicians: An analysis of Physician Masterfile data. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:1402–1407. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.10.1402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Konrad TR, Slifkin RT, Stevens C, Miller J. Using the American Medical Association physician masterfile to measure physician supply in small towns. J Rural Health. 2000;16:162–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2000.tb00450.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]