Abstract

Background

Proteasome functional insufficiency is implicated in a large subset of cardiovascular diseases and may play an important role in their pathogenesis. The regulation of proteasome function is poorly understood, hindering the development of effective strategies to improve proteasome function.

Methods and Results

Protein kinase G (PKG) was manipulated genetically and pharmacologically in cultured cardiomyocytes. Activation of PKG increased proteasome peptidase activities, facilitated proteasome-mediated degradation of surrogate (GFPu) and bona fide misfolded proteins (CryABR120G), and attenuated CryABR120G overexpression-induced accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and cellular injury. PKG inhibition elicited the opposite responses. Differences in the abundance of the key 26S proteasome subunits Rpt6 and □5 between PKG manipulated and the control groups were not statistically significant, but the isoelectric points of were shifted by PKG activation. In transgenic mice expressing a surrogate substrate (GFPdgn), PKG activation by sildenafil increased myocardial proteasome activities and significantly decreased myocardial GFPdgn protein levels. Sildenafil treatment significantly increased myocardial PKG activity and significantly reduced myocardial accumulation of CryABR120G, ubiquitin conjugates, and aberrant protein aggregates in mice with CryABR120G-based desmin-related cardiomyopathy. No discernible effect on bona fide native substrates of the ubiquitin-proteasome system was observed from PKG manipulation in vitro or in vivo.

Conclusions

PKG positively regulates proteasome activities and proteasome-mediated degradation of misfolded proteins likely through posttranslational modifications to proteasome subunits. This may be a new mechanism underlying the benefit of PKG stimulation in treating cardiac diseases. Stimulation of PKG by measures such as sildenafil administration is potentially a new therapeutic strategy to treat cardiac proteinopathies.

Keywords: Protein kinase G, proteasome, misfolded proteins, desmin-related cardiomyopathy

The ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) mediates the degradation of most intracellular proteins and regulates diverse cellular processes, including protein quality control (PQC). UPS-mediated proteolysis generally involves two steps: targeting of the substrate protein by ubiquitination and the subsequent degradation of the ubiquitinated protein by the 26S proteasome.1, 2 The UPS is responsible for the removal of terminally misfolded proteins; however, the UPS, particularly the proteasome, can be overwhelmed by increased production of misfolded proteins,3 as observed in proteinopathy and ischemia-reperfusion injury,4 which causes proteasome functional insufficiency (PFI) and PQC inadequacy.5 Inadequate PQC causes cellular dysfunction and cell death. Adult cardiomyocytes are particularly vulnerable to the toxic effects of misfolded proteins, due to poor regenerative capability. The majority of failing human hearts with hypertrophic, dilated, or ischemic cardiomyopathy display increases in ubiquitinated proteins and abnormal protein aggregation in the form of, for example, pre-amyloid oligomer formation from unknown proteins,6–9 and often decreased proteasome activities.10, 11 These seminal findings implicate an important role for PFI in the progression of a large subset of cardiovascular disease to congestive heart failure (CHF) in humans.5, 12 Indeed, experimental studies have revealed that PFI may play an important role in the development of at least a subset of heart diseases, such as desmin-related cardiomyopathy (DRC) and myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury.13, 14 Hence, the improvement of proteasome function has potential as a new therapeutic strategy in the treatment of heart disease. However, adopting this strategy is hindered by the lack of effective means to enhance proteasome function.

Increased cGMP production and resultant activation of cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) has been demonstrated to reverse pre-existing hypertrophy while inhibiting hypertrophic pathways.15, 16 It remains untested whether PKG regulates UPS-mediated degradation of misfolded proteins. The present study tests the hypothesis that PKG activation in cardiomyocytes enhances proteasome function and facilitates the degradation of misfolded proteins. Our results support the hypothesis and also suggest that stimulating PKG may become a therapeutic strategy to treat heart diseases with increased proteotoxic stress.

METHODS

Animal models

Protocols for animal care and use in this study were approved by the University of South Dakota Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The creation and validation of a transgenic (tg) mouse model expressing GFPdgn were reported.17 GFPdgn is a slightly shorter version of GFPu. GFPu is an enhanced green fluorescence protein (GFP) modified by carboxyl fusion of degron CL1.18 GFPu and GFPdgn are surrogates for misfolded proteins and have proven to be UPS substrates.3, 17 The line 708 tg mouse model expressing a missense mutant (R120G) □B-crystallin (CryABR120G) was described.19 CryABR120G and GFPdgn tg mice were maintained in the FVB/N inbred background. Genotypes were determined using PCR analysis.

Mouse sildenafil treatment

Age-matched male GFPdgn mice received two consecutive intraperitoneal injections of sildenafil (10mg/kg/12hr) or vehicle control. At 12hr after the second injection, ventricular myocardium was sampled for total RNA isolation, protein extraction, and histological assessments. A cohort of age-matched (~10 weeks old) line 708 male CryABR120G tg and non-tg (Ntg) littermate mice received chronic sildenafil infusion (10mg/kg/day) via subcutaneous mini-osmotic pumps (Alzet 2002 model) for 4 weeks before terminal experiments. The dose was determined based on previous reports.15, 20 Serial echocardiography was performed on this cohort as previously described.14

Recombinant adenoviruses infection of cultured neonatal rat ventricular myocytes (NRVMs)

NRVMs were isolated using the Cellutron Neomyocytes isolation system (Cellutron Life Technology, Baltimore, MD) following the manufacturer’s instructions, and cultured as described.21 Adenoviruses harboring the expression cassette for β-galactosidase (Ad-β-gal), GFPu (Ad-GFPu),3 red fluorescent protein (RFP) (Ad-RFP),22 or an HA-tagged CryABR120G (Ad-HA-CryABR120G) were described.3 We purchased from Addgene (Cambridge, MA) a pHACE plasmid harboring the coding sequence for a constitutively active human PKG1□ (designated PKGcat) which was created via deletion of the autoinhibitory domain of PKG1□□23 We sub-cloned the PKGcat coding sequence into a pShuttle-CMV vector, which was used by ViraQest Inc. (North Liberty, IA) to create Ad-PKGcat using RAPAd® technology.

RNA interference

The small interference RNA (siRNA) specific for rat PKG (PKG siRNA: 5′-AAGGTAAGCGTTACCCGAGAA-3′) was purchased from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). The siRNA transfection using LipofectamineTM 2000 transfection reagent (Invitrogen) was generally started at 24–48 hours after NRVMs were plated. The same amounts of luciferase siRNA (as control) and PKG siRNA (100 pmol) were applied to 2x106 NRVMs.

Total protein extraction and western blot analysis

Proteins were extracted from ventricular myocardium or cultured NRVMs. Protein concentration was determined using bicinchoninic acid reagents (Pierce biotechnology, Rockford, IL). SDS-PAGE, immunoblotting analysis, and densitometry were performed as described.21

Reverse transcription- polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR)

Total RNA isolated from ventricular myocardium was used for RT-PCR to assess GFPdgn mRNA levels as described.14

Cycloheximide (CHX) chase assay

This assay was performed as described.13 CHX (100μM, Sigma-Aldrich) was used to block further protein synthesis.

PKG activity assay

A PKG activity assay kit from Cyclex (Cat # CY-1161, Nagano, Japan) was used to determine myocardial PKG activities.15

Soluble/Insoluble protein extraction and filter-trap assay

Extraction was done as described.14 Briefly, ventricular myocardium tissue was homogenized in PBS (pH7.4) containing 2% Triton X-100, 5mM EDTA, 1mM PMSF, and the protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche) and centrifuged at 10,000g in 4°C for 10 minutes. The soluble fraction (supernatant) was collected. The pellet was resuspended in 1X loading buffer (40mM Tris HCl [pH 8.8], 1% SDS, 8% glycerol), boiled for 5 minutes, and centrifuged at 3000g for 5min; the supernatant was collected as the insoluble fraction. A total of 2.5□g of the insoluble fraction proteins were filtered through nitrocellulose membrane (pore diameter 0.22μm, Millipore) using a dot blot apparatus (BioRad) and immuno-probed for CryAB using mouse anti-CryAB antibodies (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY).

Fluorescence confocal microscopy

Microscopy was performed as described.21 Ventricular myocardium from GFPdgn or CryABR120G tg mice was fixed with 3.8% paraformaldehyde and processed for obtaining 6□m cryosections. The myocardial sections were stained with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated phalloidin (Invitrogen) to reveal F-actin and identify cardiomyocytes. CryAB positive aggregates were stained with the rabbit anti-CryAB antibodies. GFPdgn direct fluorescence (green) or CryAB immunofluorescence and the stained F-actin were visualized and imaged using a confocal microscope as described.21

Statistical analysis

All continuous variables are presented as mean±SD. Unless otherwise indicated, differences between two groups were evaluated for statistical significance using two-tailed Student’s t-test. When difference among 3 or more groups was evaluated, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or when appropriate, 2-way ANOVA, followed by the Holm-Sidak test for pair-wise comparisons were performed. The p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

PKG manipulation alters proteasome-mediated proteolysis in cardiomyocytes

We first tested the effect of PKG gain- and loss-of-function on proteasome-mediated proteolysis in cultured NRVMs. Ser-239 of VASP is a well-established PKG target. As evidenced by increased Ser-239 phosphorylated VASP (P-VASP, Supplementary Figure 1), PKG gain-of-function was successfully achieved by either Ad-PKGcat infection or administration of the phosphodiesterase (PDE) 5 inhibitor sildenafil which raises cGMP levels and activates PKG. In Ad-GFPu and Ad-RFP co-infected cells, the ratio of GFPu to RFP was 50~60% lower in the PKG gain-of-function groups than the respective controls (p<0.0001, Figure 1A, 1C), indicative of increased degradation of GFPu. Moreover, CHX chase assays further showed that PKG activation shortened the half-life of GFPu by >50% (p<0.05, Figure 1B, 1D), demonstrating that PKG activation enhances UPS proteolytic function. Conversely, PKG loss-of-function in cultured NRVMs, which was achieved via siRNA-mediated PKG knockdown or treatment with KT5823 (Supplementary Figure 2), increased the GFPu to RFP ratio by a factor of 2.2~2.6 (p<0.0001,), and elongated the half-life of GFPu proteins from <20min to >60min (p<0.05, Supplementary Figure 3), indicating that PKG activity is required for UPS-mediated degradation of a surrogate misfolded protein. Notably, PKG manipulation showed no discernible effect on the steady state protein level of PTEN and β-catenin (Supplementary Figure 4), two bona fide native endogenous UPS substrates.

Figure 1.

PKG activation enhances GFPu degradation in cardiomyocytes. Cultured NRVMs were infected with Ad-GFPu and Ad-RFP. Western blot analyses for the steady state protein levels of GFPu and RFP (A, C) were performed using total cell lysates from NRVMs collected at 72h after Ad-PKGcat or Ad-β-gal infection (10MOI, A) or after 48h of sildenafil treatment (1μM, C). In the cycloheximide (CHX) chase assays for GFPu (B, D), CHX treatment (100μM) was started 24h after the infection of Ad-PKGcat/Ad-β-gal (B) or the treatment of sildenafil/DMSO (D). In each run of the CHX chase, the GFPu image density immediately before CHX treatment (i.e., 0 min) was set as an arbitrary unit of one and the GFPu levels of subsequent CHX treated time points were calculated relative to it. A representative western blot image of the CHX chase is shown in the upper section of panels B and D; and GFPu protein decay and half-lives (t1/2) in NRVMs under a given treatment derived from six runs of chase were summarized in the lower section of the panels. *p<0.05 vs. the control group.

PKG activation by sildenafil decreases GFPdgn protein levels in mouse hearts

To confirm in intact animals the findings from cultured NRVMs, we treated GFPdgn mice with sildenafil (i.p., 10mg/kg/12hr ) for 24hrs and assessed cardiac GFPdgn expression. PKG activation was confirmed by increased P-VASP (p<0.0001, Figure 2A). Sildenafil treatment decreased myocardial GFPdgn protein levels by ~50% (p<0.0001, Figure 2B) but showed no discernible effects on GFPdgn mRNA levels (p=0.545, Figure 2C). The decease of GFPdgn in the cardiomyocyte compartment is confirmed by confocal microscopy (Figure 2D). These in vivo data confirm our in vitro findings that PKG activation by sildenafil stimulates UPS proteolytic function and facilitates the removal of a surrogate misfolded protein in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 2.

Sildenafil stimulates cardiac proteasome proteolytic function in mice. Male GFPdgn mice were subject to two peritoneal injections of sildenafil (10mg/kg) or vehicle control, with a 12-hour interval. Ventricular myocardial samples were collected at 12h after the second injection for the indicated assays. A, Western blot analyses for PKG, total VASP (T-VASP), and Ser-239 phosphorylated VASP (P-VASP). B, Western blot analysis for myocardial GFPdgn protein levels. C, RT-PCR analysis of myocardial GFPdgn mRNA levels. D, Representative fluorescence confocal micrographs of sildenafil or vehicle treated GFPdgn mouse ventricular myocardium. n=6 mice/group.

PKG stimulates proteasome peptidase activities in vivo and in vitro

To probe whether PKG regulates the proteasome, we examined proteasome peptidase activities in sildenafil treated GFPdgn mice and PKG manipulated NRVMs. Sildenafil treatment increased myocardial ATP-dependent chymotrypsin-like activity by ~50% (p<0.005) and ATP-independent and dependent trypsin-like activities by ~50% (p<0.01, Figure 3A). Compared with their respective controls, both PKGcat overexpression and sildenafil treatment caused significant increases in the ATP-dependent proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity (p<0.005, 0.01) and in the ATP-independent proteasomal trypsin-like activity in cultured NRVMs (p<0.005, 0.01, Figure 3B, 3C). Conversely, PKG inhibition in cultured NRVMs by either PKG knockdown or KT5823 treatment decreased all three proteasome peptidase activities in both the absence and presence of ATP (p<0.05 or 0.01, Supplementary Figure 5).

Figure 3.

PKG activation increases proteasome peptidase activities and decreases the pI of proteasome subunits. A, Changes in myocardial proteasome peptidase activities in GFPdgn mice treated with sildenafil as described in Figure 3. Crude protein exacts from ventricular myocardium were used for the indicated peptidase activity assays in presence or absence of ATP. B and C, Effects of PKG activation on proteasome peptidase activities in cultured NRVMs. PKG activation by either forced expression of PKGcat (B) or sildenafil treatment (C) in NRVMs was as described in Figure 1. Crude protein extracts from the cultured cells were used for proteasomal peptidase activity assays in presence or absence of ATP. n=6 biological repeats. NS=not significant, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.005; the same for all subsequent figures. D, Representative images of 2D western blot analyses of Rpt6 and β5 proteasome subunits 72h after Ad-PKGcat or Ad-β-gal infection. Isoelectric focusing gels (IFG) with a pH range from 7 to10 were used for the first dimension separation of proteins based on their pI. For the second dimension separation based on molecular weights, the fully executed IFG was placed in a large center well that was flanked by regular small wells (arrow heads) which were used for one dimensional fractionation of the same source of protein samples as that used for the IFG. The 2D gel was transferred to PVDF membrane and subject to immunoblotting for the indicated proteins.

Alterations of proteasome activities may result from altered proteasome abundance and/or post-translational modifications. Thus, we assessed relative amounts of the Rpt6 of the 19S cap and of the β5 subunit of the 20S core. No statistically significant changes in proteasome subunit abundance were detected from sildenafil-treated mouse hearts (Supplementary Figure 6) or PKG-manipulated cultured cardiomyocytes (Supplementary Figure 7), indicating that altered proteasome abundance is unlikely the underlying mechanism. Two dimensional western blot analyses from NRVMs infected with PKGcat showed that the isoelectric point (pI) of a remarkable subpopulation of Rpt6 and β5 displayed a shift toward the acidic side (Figure 3D), whereas PKG knockdown elicited a shift towards the basic end (Supplementary Figure 8). These results indicate that post-translational modifications, likely phosphorylation, of the proteasome may be a mechanism underlying PKG modulation of proteasomal function.

PKG activation enhances proteasomal degradation of a human disease-linked misfolded protein

The results described above establish the ability of PKG to regulate proteasome-mediated proteolysis. As such, we sought to further demonstrate the translational relevance of the newly discovered function of PKG by examining the impact of PKG manipulation on the removal of CryABR120G, a bona fide misfolded protein known to cause DRC in humans and mice.19, 24 HA-tagged CryABR120G was overexpressed in NRVMs via adenoviral gene delivery. Activation of PKG by PKGcat overexpression or sildenafil significantly decreased the steady-state protein levels of CryABR120G (23 kDa) and its higher molecular weight modified species (~25–26 and ~29–30 kDa; Figure 4A, 4B). The reduction of CryABR120G protein levels by PKG activation is proteasome-dependent because the reduction was blocked in presence of proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (BZM, Figure 4C~4E). Conversely, PKG inhibition with PKG knockdown or KT5823 increased the steady state protein levels of CryABR120G and its higher molecular weight modified species (Supplemental Figure 9). Moreover, as revealed by the CHX chase assay, PKG activation significantly shortened CryABR120G protein half-life by >70% (p<0.01, Figure 4F, 4G). In contrast, PKG activation showed no discernible effects on the half-life of β-tubulin (Supplementary Figure 10). These results further demonstrate that PKG activation enhances the proteasome-mediated degradation of misfolded but not native proteins.

Figure 4.

Activation of PKG enhances proteasome-mediated removal of CryABR120G. NRVMs were cultured for 24h before PKG was manipulated via Ad-PKGcat infection (A, C, F) or sildenafil treatment (B, D, G). Following an additional 24h in culture, NRVMs were infected with either control Ad-β-gal or Ad-HA-CryABR120G. A and B, Representative images of western blot analyses of HA-CryABR120G (upper panel) and β-tubulin in NRVMs 72h after infection with Ad-HA-CryABR120G or Ad-β-gal. C–E, Reduction of steady state HA-CryABR120G protein levels by PKGcat or sildenafil is proteasome-dependent. The proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (BZM, 10nM) or volume corrected saline was applied upon changing of the infection media to normal growth media. NRVMs were harvested after an additional 72 hours for protein extraction. Representative images (C, D) of western blot analyses of the indicated proteins and the pooled densitometry data (E) from four (PKGcat cohort) or three (sildenafil cohort) biological repeats are shown. F and G, CHX chase of HA-CryABR120G and β-tubulin in NRVMs at the indicated time points during PKG activation with PKGcat (F) or sildenafil (G). CHX was administered 24h after Ad-HA-CryABR120G infection. Representative western blot images (upper panel) and the pooled data of the HA-CryABR120G decay and half-life (lower panel) are shown. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 vs. the control group; n= 4 repeats.

Overexpression of misfolded proteins (e.g., CryABR120G) causes PFI and accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in cardiomyocytes.3 Here we observed that CryABR120G overexpression-induced accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in NRVMs was effectively attenuated by PKG activation via PKGcat or sildenafil (p<0.005) and exacerbated by PKG inhibition with PKG knockdown or KT5823 (p<0.005, Figures 5). These findings support the conclusion that PKG positively regulates proteasome function and thereby facilitates the removal of misfolded proteins in cardiomyocytes.

Figure 5.

PKG regulates the abundance of ubiquitin conjugates in cardiomyocytes overexpressing CryABR120G. A and B, Western blot analyses for total ubiquitinated (Ub’n) proteins in PKG activated NRVMS. NRVMs were cultured and manipulated as described in Figure 4. NRVMs were harvested 72h post Ad-HA-CryABR120G infection. β-Tubulin was probed as loading control. Representative images and a summary of pooled densitometry data from the PKGcat/β-gal cohort (A) and the sildenafil/DMSO cohort (B) are shown in the upper and lower sections of each panel, respectively. C and D, Western blot analyses for total ubiquitinated proteins in PKG inhibited NRVMS. NRVMs were transfected with siPKG/siLuc (C) or treated with KT5823/DMSO (D) 24h after plating, cultured for additional 24h before Ad-HA-CryABR120G or Ad-β-gal infection was performed. The cells were harvested 72h after adenoviral infection.

PKG activation by sildenafil decreases protein aggregation and slows down disease progression in DRC mice

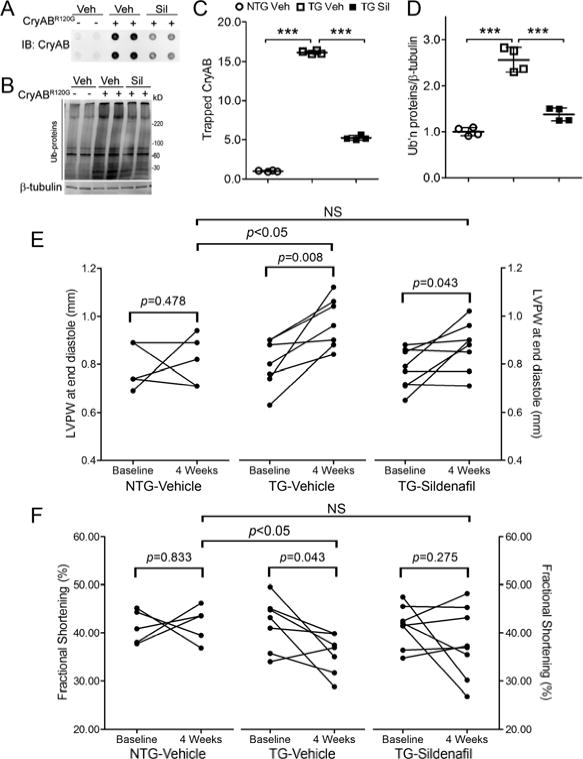

To test whether PKG activation by sildenafil can exert the same effect in mouse hearts as observed in cultured cardiomyocytes, we treated line 708 CryABR120G tg mice with sildenafil (10mg/kg/day) for 4 weeks via mini-osmotic pumps. PKG activation by sildenafil treatment is confirmed by the >100% higher myocardial PKG activity (p<0.005, Figure 6A) and ~60% greater P-VASP levels (p<0.01, Figure 6B, 6C) in the sildenafil-treated CryABR120G tg group than the vehicle control CryABR120G tg group. Soluble, and especially insoluble CryAB, protein (Figure 6E~6H) but not mRNA levels (data not shown) in the CryABR120G tg hearts were significantly decreased by sildenafil treatment. Filter-trap assays show that detergent-resistant aggregated CryAB proteins were increased by a factor of ~16 in CryABR120G tg hearts compared with Ntg (p<0.005); these increases were attenuated by ~65% by sildenafil treatment (p<0.005, Figure 7A, 7C). As expected, total high molecular weight ubiquitinated proteins (Figure 7B, 7D) and CryAB-positive protein aggregates (Supplementary Figure 11) were significantly increased in CryABR120G tg hearts; importantly, these increases were remarkably attenuated by sildenafil treatment. These in vivo data provide compelling evidence that PKG activation by sildenafil facilitates CryABR120G removal and reduces aberrant protein aggregation, a key pathological process in disease with increased proteotoxic stress.

Figure 6.

Sildenafil increases PKG activity and CryABR120G protein degradation in CryABR120G tg mouse hearts. Line 708 CryABR120G tg (+) and Ntg (-) littermate mice were treated with sildenafil (Sil, 10mg/kg/day) or vehicle control (Veh) for 4 weeks via subcutaneous implantation of mini-osmotic pumps. Ventricular myocardium was sampled at the end of treatment for analyses reported here. A, Changes in myocardial PKG activity. B~D, Western blot analyses for PKG, P-VASP, and T-VASP. Representative images (B) and pooled densitometry data (C, D) are presented. E~H, Western blot analyses for CryAB in the soluble (E, G) and insoluble (F, H) fractions. Representative images (E, F) and pooled densitometry data (G, H) are presented.

Figure 7.

Sildenafil reduces cardiac aberrant protein aggregation and cardiac hypertrophy and blunts heart function decline in CryABR120G tg mice. The same mouse cohorts as described in Figure 6 were used for data collection here. A and B, The immunoblot images (A) and summary of densitometry data (C) of the filter trap assay for CryAB. The insoluble fraction of myocardial proteins was filtered through a nitrocellulose membrane (pore diameter=0.22μm) and the proteins trapped on the membrane were detected by immunoblotting (IB) for CryAB. B and D, Representative images (B) and a summary of densitometry data (D) of western blot analyses for total ubiquitinated proteins. Each dot represents an individual mouse. E and F, The effect of sildenafil on changes in the end-diastolic left ventricular posterior wall thickness (LVPW) (E) and the fractional shortening (FS) (F) during the 4 weeks of treatment. LVPW and FS data were from serial echocardiographs recorded at 1 day before (baseline) and the final day of (4 weeks) treatment with sildenafil or vehicle (see also online Supplementary Table 1). Two-tailed paired t-tests are used to compare the 4 week time point with the baseline within the group. Inter-group comparisons use one way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s pair-wise tests.

Serial echocardiography revealed that immediately before sildenafil treatment was initiated, there were no statistically significant differences in either the end diastolic left ventricle posterior wall thickness (LVPWd) or the fractional shortening (FS) among the three groups (Supplementary Table 1). At the end of 4 weeks of treatment, compared with the vehicle-treated NTG group, LVPW;d was 18.2% greater (p<0.05) but FS is 15.3% smaller (p<0.05) in the vehicle-treated CryABR120G tg group; however, the differences in both LVPWd and FS between the sildenafil-treated tg and vehicle-treated NTG groups are not statistically significant (p>0.05) (Figure 7E, 7F). These results indicate that sildenafil treatment attenuates both cardiac hypertrophy and heart function decline in the DRC mice.

PKG activation protects cardiomyocytes from proteotoxic stress

It has been previously shown that overexpression of CryABR120G in cardiomyocytes leads to cell injury as manifested by increased cardiomyocyte death.25–27 As expected, we observed that overexpression of CryABR120G in cultured NRVMs led to increases in the level of cleaved (activated) caspase 3, significantly elevated leakage of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) to culture media (p<0.005), decreased survival of cardiomyocytes as revealed by MTT assays (p<0.005), and increased LDH/MTT ratios (p<0.005). Importantly, changes in all these parameters of cell injury were significantly attenuated by PKGcat overexpression or by treatment with sildenafil (p<0.05, 0.005; Figure 8) and exacerbated by PKG inhibition achieved by PKG knockdown or KT treatment (Supplementary Figure 12). These data show that PKG activation protects cardiomyocytes against proteotoxic stress triggered by overexpression of a bona fide misfolded protein.

Figure 8.

PKG activation protects against proteotoxic stress in cardiomyocytes. PKG activation in NRVMs overexpressing CryABR120G was achieved by PKGcat overexpression (A, C) or sildenafil treatment (B, D), as described in Figure 5. The cultured cells were collected for western blot analyses for caspase 3 and MTT assay and the culture media were simultaneously collected for LDH assays. The LDH/MTT ratio is used to minimize the impact of potential variation resulting from the potential difference in the total cell number on a dish.

DISCUSSION

In the research field of UPS-mediated proteolysis, extensive attention was directed towards understanding the factors that control the ubiquitination of specific proteins. By contrast, only a few reported studies have investigated whether and how proteasome function is regulated.2, 28–30 However, increasing evidence suggests a role for PFI in the progression of at least a subset of heart diseases.5, 11 Preserving proteasome function was shown to underlie cardiac protection of ischemic preconditioning.31, 32 Previously, we experimentally demonstrated that improving proteasome-mediated degradation of misfolded proteins via a genetic approach alleviates cardiac pathological conditions characterized by an increased production of misfolded/damaged proteins.13, 14 The present study demonstrates for the first time that PKG is an important regulator of proteasome-mediated proteolysis, and that pharmacological activation of PKG by PDE5 inhibitor sildenafil can stimulate proteasome activities, facilitate the clearance of a surrogate and a bona fide misfolded protein, and decrease aberrant protein aggregation in vitro and in vivo, thereby protecting cardiomyocytes against proteotoxic stress.

PKG positively regulates UPS-mediated degradation of misfolded proteins in vitro and in vivo

We have discovered that PKG activation by either genetic or pharmacological means was sufficient to destabilize a surrogate misfolded protein (GFPu) substrate of the UPS, whereas PKG inhibition stabilizes the GFPu proteins in cultured cardiomyocytes. Moreover, we have also shown that PKG activation by sildenafil treatment significantly decreases myocardial GFPdgn protein levels, but displays no discernible effect on GFPdgn mRNA levels, in GFPdgn tg mice. These findings suggest that PKG positively regulates the degradation of a misfolded protein by the UPS. We have further tested this postulate in both cultured cardiomyocytes and intact mice that overexpress CryABR120G, a bona fide misfolded protein known to cause human disease.24 We collected compelling evidence that PKG activation by either genetic or pharmacological methods facilitates, whereas PKG inhibition by genetic and pharmacological means decreases, the UPS-mediated degradation of CryABR120G in cultured NRVMs.

Sildenafil treatment showed no discernible effects on myocardial calpain activities in CryABR120G tg mice (Supplementary Figure 13) or on the protein levels of an autophagosome marker LC3-II and a well-established autophagic substrate p62/SQSTM1 in GFPdgn mouse hearts (Supplementary Figure 14). These data suggest that calpain and the autophagic-lysosomal pathway are unlikely involved in our observed effects.

UPS-mediated protein degradation takes two consecutive steps: ubiquitination and proteasomal cleavage.5 When the proteasome was inhibited, genetic PKG activation displayed no discernible effect on the levels of total ubiquitin conjugates in GFPu or HA-CryABR120G overexpressing NRVMs (Supplementary Figure 15), indicating that PKG activation does not appear to have a global effect on ubiquitination in cardiomyocytes. When GFPu or HA-CryABR120G proteins were probed in proteasome-inhibited NRVMs, we found that PKG activation showed no discernible effect on the levels of the higher molecular weight (HMW) species of GFPu (p>0.05) but significantly increased the level of multiple HMW species of CryABR120G (p<0.005, Supplementary Figure 16). These HMW CryABR120G species are likely ubiquitinated forms of CryABR120G; hence, these data suggest that PKG activation has differential effects on the ubiquitination of GFPu and CryABR120G. Given UPS-mediated degradation of both GFPu and CryABR120G are facilitated by PKG activation, it is likely that facilitation of UPS-mediated misfolded protein degradation by PKG is primarily due to proteasome enhancement. This is consistent with the notion that the rate-limiting step for UPS-mediated degradation of misfolded proteins resides in the proteasome not ubiquitination. This notion is supported by multiple lines of evidence: first, total ubiquitinated proteins are always increased in cells overexpressing misfolded proteins,33 as illustrated by the increases in ubiquitin conjugates in NRVMs overexpressing CryABR120G (Figure 5); second, aberrant protein aggregation resulting from misfolded proteins impairs proteasome function, leading to PFI in vitro and in vivo;3 and finally, direct proteasomal enhancement via overexpression of a proteasome activator (PA28α) was sufficient to facilitate degradation of GFPdgn and CryABR120G and protects against CryABR120G-based proteinopathy injury, demonstrating that PFI play a major role in the genesis of CryABR120G-based cardiomyopathy.14 Here we observed that while increasing proteasome function, PKG activation by PKGcat overexpression or sildenafil treatment significantly shortened the half-life of CryABR120G proteins, decreased the steady state CryABR120G protein level, and attenuated the associated ubiquitin conjugate accumulation in cultured cardiomyocytes.

This is a highly significant discovery as currently no pharmacological agent has been shown capable of increasing proteasome function and facilitating the removal of misfolded proteins in cardiomyocytes. The very favorable actions of PKG have potential to be capitalized on to treat heart disease with increased proteotoxic stress. Indeed, we have further demonstrated in CryABR120G tg mice that chronic infusion of sildenafil activates PKG and decreases the soluble, the insoluble, and the detergent-resistant aggregated forms of CryAB, mimicking the previous reported effect of proteasomal enhancement by PA28α overexpression.14 Notably, PKG activation does not seem to alter the protein levels of bona fide native endogenous substrates of the UPS (e.g., β-catenin and PTEN). These observations suggest that PKG stimulation activates selective pathways for misfolded protein degradation, making the said approach an attractive strategy to treat disease.

Potential mechanisms by which PKG enhances proteasome function

The 26S proteasome is composed of a 20S proteolytic core (where the three peptidase activities reside) flanked at one or both ends by the 19S regulatory subcomplex. The 19S recognizes, binds to, and deubiquitinates polyubiquitinated proteins, unfolds them, and channels the unfolded polypeptide into the 20S.34 In the cell, the 19S and the 20S complexes can both exist in free forms or associate with each other to form the 26S proteasome. The association of the 19S with the 20S requires ATP; hence, in vitro peptidase activity assays are often performed in the presence and absence of ATP to decipher the impact of the association of 19S proteasomes on individual peptidase activities.35 PKG inhibition by either siPKG or KT5823 decreased all three proteasome peptidase activities in either the absence or presence of ATP, suggesting that a basal level of PKG activity is necessary for all proteasome peptidase activities. PKG gain-of-function did not show a discernible effect on caspase-like activities in vitro or in vivo. Interestingly, both overexpressing PKGcat and sildenafil treatment in cultured NRVMs could only stimulate trypsin-like activity in the absence of ATP. This indicates that raising PKG activities above the baseline can enhance the 20S proteasome trypsin-like activities but not when the 20S is associated with the 19S in cultured cardiomyocytes. Notably, myocardial proteasomal trypsin-like activities, both ATP-dependent and independent, were significantly increased in mice treated with sildenafil, compared with the control treatment group, indicating that PKG activation by sildenafil may increase cardiac trypsin-like activity of both 20S and 26S proteasomes in vivo. The cause of the extra in vivo stimulating effect of sildenafil is unknown but might involve a cross-talk between cGMP and cAMP signaling. Increased cGMP from sildenafil treatment could inhibit PDE3 and thereby raise cAMP levels and activate cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA).36 PKA activation has been shown to increase 26S trypsin-like activity.37 By contrast, PKG gain-of-function both in vitro and in vivo could only increase chymotrypsin-like activities in the 26S. It is generally believed that the 26S proteasome is primarily responsible for the degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins. The chymotrypsin-like activity conferred by the β5 subunit of the 20S is the most important one among the three peptidase subunits in determining proteasome proteolytic function.38, 39 Hence, our data from peptidase assays suggest that increased UPS function by PKG is primarily attributable to enhanced chymotrypsin-like activities of the 26S proteasome.

The regulation of PKG on cardiac proteasome function is unlikely by altering proteasome abundance, as no discernible changes in the protein level of representative subunits of 19S and 20S proteasomes were detected in PKG manipulated cardiomyocytes and sildenafil-treated mouse hearts. This is also supported by our findings that PKG gain-of-function does not increase all three proteasome peptidase activities uniformly, but rather, differentially. This generates a hypothesis that post-translational modification may be responsible. Indeed, we found that the pI of a representative 20S subunit (β5) and 19S proteasome subunit (Rpt6) were shifted to the acidic side (consistent with hyperphosphorylation) by PKG activation and conversely to the basic side (consistent with hypophosphorylation) by PKG inhibition. Notably, it has been reported that hyperphosphorylated proteasomes show higher activities.2 For example, protein kinase A (PKA) was shown to increase nuclear proteasome function by phosphorylating Rpt6 at Ser120.30 Hence, a likely mechanism by which PKG activation enhances proteasome function is to directly or indirectly increase the phosphorylation of proteasome subunits, such as β5 and Rpt6, thereby increasing the chymotrypsin-like activities of the 26S proteasome. It will be important to elucidate the mechanism underlying PKG mediated positive regulation of proteasome function.

PKG activation protects cardiomyocytes against proteotoxic stress

Genetic enhancement of proteasomal degradation of misfolded proteins and resulted inhibition of aberrant protein aggregation can protect the heart from proteotoxic stress.14 Hence, activation of PKG, which stimulates proteasomal degradation of misfolded proteins, should protect cardiomyocytes against the toxicity of misfolded proteins. This is exactly what we have observed in both DRC mice and cultured NRVMs. During the 4-week period of sildenafil trial, vehicle-treated, but not sildenafil-treated, CryABR120G tg mice displayed significantly greater LV posterior wall thickening and FS decline than the vehicle-treated NTG control mice (Figure 7E, 7F), suggesting that sildenafil can slow down DRC progression. By measuring caspase 3 activation, LDH leakage, and cell survival, we found that PKG gain-of-function by PKGcat overexpression or sildenafil treatment significantly attenuated, whereas PKG inhibition by PKG knockdown or KT5823 treatment significantly exacerbated, cardiomyocyte injury induced by overexpression of CryABR120G.

Taken together, our results suggest that strategies to increase PKG activity may conceivably be utilized to treat disease with increased proteotoxic stress, such as DRC and other proteinopathy. Currently, no treatment is available for these debilitating diseases. FDA approved drugs (e.g., sildenafil) are readily available to stimulate PKG. Moreover, this study provides a potentially new mechanism for PDE5 inhibition in treating heart diseases. PDE5 inhibition by sildenafil elicits reverse remodeling and improves cardiac function in CHF animal models and human patients.15, 40–42 Inadequate PQC, especially PFI, is suggested as a common pathogenic factor in the progression of a large subset of heart diseases.6–9 Accumulation of misfolded proteins, including pre-amyloid oligomers in cardiomyocytes, is sufficient to cause cardiomyopathy in mice and conversely, improving proteasome function slows down the progression of cardiac proteinopathy.14, 43 Therefore, it is highly possible that improvements to PQC in cardiomyocytes of diseased hearts are a benefit of PKG stimulation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Imaging Core of the Division of Basic Biomedical Sciences for assistance with confocal microscopy.

Funding Sources: This work was supported in part by NIH grants R01HL072166 and R01HL085629 and American Heart Association grants 0740025N (to X.W.) and 11PRE5730009 (to M.J.R). The Imaging Core was supported by an NIH grant 5P20RR015567.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None.

References

- 1.Willis MS, Townley-Tilson WH, Kang EY, Homeister JW, Patterson C. Sent to destroy: The ubiquitin proteasome system regulates cell signaling and protein quality control in cardiovascular development and disease. Circ Res. 2010;106:463–478. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.208801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scruggs SB, Zong NC, Wang D, Stefani E, Ping P. Post-translational modification of cardiac proteasomes: Functional delineation enabled by proteomics. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2012;303:H9–18. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00189.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Q, Liu JB, Horak KM, Zheng H, Kumarapeli AR, Li J, Li F, Gerdes AM, Wawrousek EF, Wang X. Intrasarcoplasmic amyloidosis impairs proteolytic function of proteasomes in cardiomyocytes by compromising substrate uptake. Circ Res. 2005;97:1018–1026. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000189262.92896.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tian Z, Zheng H, Li J, Li Y, Su H, Wang X. Genetically induced moderate inhibition of the proteasome in cardiomyocytes exacerbates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Circ Res. 2012;111:532–542. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.270983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang X, Pattison JS, Su H. Posttranslational modification and quality control. Circ Res. 2013;112:367–381. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.268706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weekes J, Morrison K, Mullen A, Wait R, Barton P, Dunn MJ. Hyperubiquitination of proteins in dilated cardiomyopathy. Proteomics. 2003;3:208–216. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200390029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kostin S, Pool L, Elsasser A, Hein S, Drexler HC, Arnon E, Hayakawa Y, Zimmermann R, Bauer E, Klovekorn WP, Schaper J. Myocytes die by multiple mechanisms in failing human hearts. Circ Res. 2003;92:715–724. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000067471.95890.5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanbe A, Osinska H, Saffitz JE, Glabe CG, Kayed R, Maloyan A, Robbins J. Desmin-related cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice: A cardiac amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10132–10136. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401900101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gianni D, Li A, Tesco G, McKay KM, Moore J, Raygor K, Rota M, Gwathmey JK, Dec GW, Aretz T, Leri A, Semigran MJ, Anversa P, Macgillivray TE, Tanzi RE, del Monte F. Protein aggregates and novel presenilin gene variants in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2010;121:1216–1226. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.879510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsukamoto O, Minamino T, Okada K, Shintani Y, Takashima S, Kato H, Liao Y, Okazaki H, Asai M, Hirata A, Fujita M, Asano Y, Yamazaki S, Asanuma H, Hori M, Kitakaze M. Depression of proteasome activities during the progression of cardiac dysfunction in pressureoverloaded heart of mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:1125–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Predmore JM, Wang P, Davis F, Bartolone S, Westfall MV, Dyke DB, Pagani F, Powell SR, Day SM. Ubiquitin proteasome dysfunction in human hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies. Circulation. 2010;121:997–1004. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.904557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schlossarek S, Carrier L. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in cardiomyopathies. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2011;26:190–195. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e32834598fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Powell SR, Wang X. Enhancement of proteasome function by pa28α overexpression protects against oxidative stress. FASEB J. 2011;25:883–893. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-160895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Horak KM, Su H, Sanbe A, Robbins J, Wang X. Enhancement of proteasomal function protects against cardiac proteinopathy and ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:3689–3700. doi: 10.1172/JCI45709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Takimoto E, Champion HC, Li M, Belardi D, Ren S, Rodriguez ER, Bedja D, Gabrielson KL, Wang Y, Kass DA. Chronic inhibition of cyclic gmp phosphodiesterase 5a prevents and reverses cardiac hypertrophy. Nat Med. 2005;11:214–222. doi: 10.1038/nm1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castro LR, Verde I, Cooper DM, Fischmeister R. Cyclic guanosine monophosphate compartmentation in rat cardiac myocytes. Circulation. 2006;113:2221–2228. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.599241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumarapeli AR, Horak KM, Glasford JW, Li J, Chen Q, Liu J, Zheng H, Wang X. A novel transgenic mouse model reveals deregulation of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in the heart by doxorubicin. Faseb J. 2005;19:2051–2053. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-3973fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilon T, Chomsky O, Kulka RG. Degradation signals for ubiquitin system proteolysis in saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 1998;17:2759–2766. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang X, Osinska H, Klevitsky R, Gerdes AM, Nieman M, Lorenz J, Hewett T, Robbins J. Expression of r120g-alphab-crystallin causes aberrant desmin and alphab-crystallin aggregation and cardiomyopathy in mice. Circ Res. 2001;89:84–91. doi: 10.1161/hh1301.092688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chau VQ, Salloum FN, Hoke NN, Abbate A, Kukreja RC. Mitigation of the progression of heart failure with sildenafil involves inhibition of rhoa/rho-kinase pathway. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;300:H2272–2279. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00654.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su H, Li F, Ranek MJ, Wei N, Wang X. Cop9 signalosome regulates autophagosome maturation. Circulation. 2011;124:2117–2128. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.048934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tydlacka S, Wang CE, Wang X, Li S, Li XJ. Differential activities of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in neurons versus glia may account for the preferential accumulation of misfolded proteins in neurons. J Neurosci. 2008;28:13285–13295. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4393-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deguchi A, Soh JW, Li H, Pamukcu R, Thompson WJ, Weinstein IB. Vasodilator-stimulated phosphoprotein (vasp) phosphorylation provides a biomarker for the action of exisulind and related agents that activate protein kinase g. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:803–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vicart P, Caron A, Guicheney P, Li Z, Prevost MC, Faure A, Chateau D, Chapon F, Tome F, Dupret JM, Paulin D, Fardeau M. A missense mutation in the alphab-crystallin chaperone gene causes a desmin-related myopathy. Nat Genet. 1998;20:92–95. doi: 10.1038/1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maloyan A, Sanbe A, Osinska H, Westfall M, Robinson D, Imahashi K, Murphy E, Robbins J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis underlie the pathogenic process in alpha-b-crystallin desmin-related cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;112:3451–3461. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.572552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pattison JS, Osinska H, Robbins J. Atg7 induces basal autophagy and rescues autophagic deficiency in cryabr120g cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2011;109:151–160. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.237339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng Q, Su H, Ranek MJ, Wang X. Autophagy and p62 in cardiac proteinopathy. Circ Res. 2011;109:296–308. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.244707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Asai M, Tsukamoto O, Minamino T, Asanuma H, Fujita M, Asano Y, Takahama H, Sasaki H, Higo S, Asakura M, Takashima S, Hori M, Kitakaze M. Pka rapidly enhances proteasome assembly and activity in in vivo canine hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2009;46:452–462. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lu H, Zong C, Wang Y, Young GW, Deng N, Souda P, Li X, Whitelegge J, Drews O, Yang PY, Ping P. Revealing the dynamics of the 20 s proteasome phosphoproteome: A combined cid and electron transfer dissociation approach. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:2073–2089. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800064-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang F, Hu Y, Huang P, Toleman CA, Paterson AJ, Kudlow JE. Proteasome function is regulated by cyclic amp-dependent protein kinase through phosphorylation of rpt6. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:22460–22471. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702439200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Divald A, Kivity S, Wang P, Hochhauser E, Roberts B, Teichberg S, Gomes AV, Powell SR. Myocardial ischemic preconditioning preserves postischemic function of the 26s proteasome through diminished oxidative damage to 19s regulatory particle subunits. Circ Res. 2010;106:1829–1838. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.219485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Churchill EN, Ferreira JC, Brum PC, Szweda LI, Mochly-Rosen D. Ischaemic preconditioning improves proteasomal activity and increases the degradation of deltapkc during reperfusion. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:385–394. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang X, Terpstra EJ. Ubiquitin receptors and protein quality control. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;55:73–84. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.09.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gomes AV, Zong C, Edmondson RD, Li X, Stefani E, Zhang J, Jones RC, Thyparambil S, Wang GW, Qiao X, Bardag-Gorce F, Ping P. Mapping the murine cardiac 26s proteasome complexes. Circ Res. 2006;99:362–371. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000237386.98506.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Powell SR, Davies KJ, Divald A. Optimal determination of heart tissue 26s-proteasome activity requires maximal stimulating atp concentrations. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;42:265–269. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zaccolo M, Movsesian MA. Camp and cgmp signaling cross-talk: Role of phosphodiesterases and implications for cardiac pathophysiology. Circ Res. 2007;100:1569–1578. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.106.144501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drews O, Tsukamoto O, Liem D, Streicher J, Wang Y, Ping P. Differential regulation of proteasome function in isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res. 2010;107:1094–1101. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.110.222364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jager S, Groll M, Huber R, Wolf DH, Heinemeyer W. Proteasome beta-type subunits: Unequal roles of propeptides in core particle maturation and a hierarchy of active site function. J Mol Biol. 1999;291:997–1013. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen P, Hochstrasser M. Autocatalytic subunit processing couples active site formation in the 20s proteasome to completion of assembly. Cell. 1996;86:961–972. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kass DA. Res-erection of viagra as a heart drug. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:2–4. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.960062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Guazzi M, Vicenzi M, Arena R, Guazzi MD. Pde5 inhibition with sildenafil improves left ventricular diastolic function, cardiac geometry, and clinical status in patients with stable systolic heart failure: Results of a 1-year, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Circ Heart Fail. 2011;4:8–17. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.110.944694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lindman BR, Zajarias A, Madrazo JA, Shah J, Gage BF, Novak E, Johnson SN, Chakinala MM, Hohn TA, Saghir M, Mann DL. Effects of phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibition on systemic and pulmonary hemodynamics and ventricular function in patients with severe symptomatic aortic stenosis. Circulation. 2012;125:2353–2362. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.081125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pattison JS, Sanbe A, Maloyan A, Osinska H, Klevitsky R, Robbins J. Cardiomyocyte expression of a polyglutamine preamyloid oligomer causes heart failure. Circulation. 2008;117:2743–2751. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.750232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.