Abstract

The purpose of this study was the immunohistochemical evaluation of (1) cartilage tissue-engineered constructs; and (2) the tissue filling cartilage defects in a goat model into which the constructs were implanted, particularly for the presence of the basement membrane molecules, laminin and type IV collagen. Basement membrane molecules are localized to the pericellular matrix in normal adult articular cartilage, but have not been examined in tissue-engineered constructs cultured in vitro or in tissue filling cartilage defects into which the constructs were implanted. Cartilaginous constructs were engineered in vitro using caprine chondrocyte-seeded type II collagen scaffolds. Autologous constructs were implanted into 4-mm-diameter defects created to the tidemark in the trochlear groove in the knee joints of skeletally mature goats. Eight weeks after implantation, the animals were sacrificed. Constructs underwent immunohistochemical and histomorphometric evaluation. Widespread staining for the two basement membrane molecules was observed throughout the extracellular matrix of in vitro and in vivo samples in a distribution unlike that previously reported for cartilage. At sacrifice, 70% of the defect site was filled with reparative tissue, which consisted largely of fibrous tissue and some fibrocartilage, with over 70% of the reparative tissue bonded to the adjacent host tissue. A novel finding of this study was the observation of laminin and type IV collagen in in vitro engineered cartilaginous constructs and in vivo cartilage repair samples from defects into which the constructs were implanted, as well as in normal caprine articular cartilage. Future work is needed to elucidate the role of basement membrane molecules during cartilage repair and regeneration.

Introduction

Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine provide new approaches for treating articular cartilage defects by utilizing a combination of scaffolds and cells, along with regulators, to engineer and regenerate new tissue. In this study, autologous chondrocyte-seeded type II collagen scaffolds were produced in vitro to form a known amount of glycosaminoglycan (GAG).1 The goal was to reach about 90% of the GAG density found in normal articular cartilage, resulting in a construct of some maturity, before implantation in a caprine model for evaluation after 8 weeks. The GAG content was used as a quantitative measure of the degree of chondrogenesis. Our rationale for achieving a construct with ∼90% GAG before implantation was based on previous work2,3 showing that chondrocyte-seeded type II collagen scaffolds cultured in vitro for 4 weeks before implantation resulted in more hyaline cartilage and more total reparative tissue filling the defect site compared to type II collagen scaffolds seeded with chondrocytes within 12 h of implantation, suggesting that implantation of a more mature cartilaginous construct may yield better healing in vivo.

Objectives of the present study included the immunohistochemical evaluation of the tissue-engineered constructs and the tissue filling the defects implanted with the constructs for the presence of type I and II collagen; lubricin, the principal boundary lubricating protein for articular cartilage (also known as proteoglycan 4)4; and the basement membrane molecules, laminin and type IV collagen. Basement membranes are specialized extracellular matrix structures generally found at the epithelial–mesenchymal interface and found surrounding muscle, peripheral nerve fibers, and fat cells, and it is recognized that basement membranes play important roles in cell growth, differentiation, and migration and in tissue development and repair.5 Although articular cartilage is not generally thought of as having a traditional basement membrane structure, the presence of basement membrane molecules, including laminin,6–8 type IV collagen,7 perlecan,7,9–12 nidogen,7 and type XVIIII collagen/endostatin,13 has been reported in normal adult articular cartilage. These molecules have generally been found to be localized to the pericellular matrix, resulting in description of the pericellular matrix as a functional equivalent of the basement membrane in articular cartilage.7 To our knowledge, work has not been done to examine the presence of basement membrane molecules in tissue-engineered constructs cultured in vitro and in tissue filling cartilage defects in vivo.

Materials and Methods

Cell isolation and two-dimensional monolayer expansion

Autologous chondrocytes were isolated from articular cartilage shavings obtained from nonarticulating regions of the stifle joints (left knee) of four skeletally mature female goats (ages 2–5 years). The animal experiment was approved by the Veterans Affairs Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in compliance with the “Principles of Laboratory Animal Care” formulated by the National Society for Medical Research. Cells were expanded in monolayer culture using a standard chondrocyte expansion medium consisting of the high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium, containing 1% nonessential amino acids (v/v), 1% HEPES buffer, 1% penicillin/streptomycin/l-glutamine, and 10% fetal bovine serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), and supplemented with 1 ng/mL transforming growth factor-β1, 5 ng/ml fibroblast growth factor-2, and 10 ng/mL platelet-derived growth factor-ββ (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). The cells were incubated at in a humidified chamber at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 21% O2 and grown through two subcultures to obtain P2 cells.

Scaffold fabrication

Scaffolds were prepared using 1% porcine cartilage-derived collagen (Geistlich Biomaterials, Wolhusen, Switzerland) as previously described.1 The proprietary treatment of the type II collagen-containing porcine cartilage degraded the type II collagen epitope. Briefly, porous sheets (∼2.5 mm thick) were fabricated by freeze drying (VirTis, Gardiner, NY). The sheets were sterilized and lightly crosslinked by dehydrothermal treatment using a vacuum greater than 30 mmHg at a temperature of 105°C. Disks (8 mm in diameter and 2.5 mm in thickness) were cut from the sheets using a dermal biopsy punch. The scaffolds were incubated in 2.5 mL of an aqueous carbodiimide solution consisting of 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide hydrochloride and N-hydroxysuccinimide (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO) at a molar ratio of 5:2:5 (EDAC:NHS:COOH, relative to the carboxyl contained in the collagen scaffold) for 2 h, and then washed with phosphate-buffered saline (Invitrogen).

Cell seeding and culture in collagen scaffolds

Collagen scaffolds were placed in agarose-coated wells for cell seeding. P2 cells were trypsinized and resuspended in the low-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium. Two million chondrocytes were pipetted onto one side of the scaffold and incubated for 10 min, followed by the addition of 2 million cells on the second side for 30 min, for a total of 4 million cells seeded per scaffold. Then, the chondrogenic medium, as previously described,14 was added to each well.

The medium was changed every 2–3 days, and constructs were cultured for 35 days, and then trimmed to 4-mm diameter using a biopsy punch before implantation. Additional constructs were terminated after 1 (n=24) and 35 (n=22) days for biochemical analysis and histological examination.

Analysis of DNA and GAG content

Constructs cultured in vitro were lyophilized and enzymatically digested overnight using proteinase K (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). The DNA content was measured using the PicoGreen dye assay kit (Molecular Probes, Inc., Eugene, OR) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The number of cells was estimated from the DNA content using an average value of 7.7 pg DNA/cell determined for goat chondrocytes.15 The sulfated GAG content was measured using the dimethylmethylene blue dye assay, with a standard curve obtained using chondroitin-6-sulfate from shark cartilage (Sigma Chemical Co.). The amount of GAG per construct was divided by its volume, and then reported as a percentage of normal, using 15.8 mg/mm3 as the normal GAG density for goat articular cartilage.1

Surgical implantation in animal model

All implantations were performed on the right knee of four goats under general anesthesia and using sterile conditions. The joint was opened by an anteromedial approach, and the patella was displaced laterally to expose the trochlea. Two 4-mm diameter chondral defects were created in the trochlear groove as previously described.16 The two defects were located ∼1.25 and 2.25 cm proximal to the intercondylar notch, slightly lateral or medial to the midline. A dermal punch was used to create the outline of the defects. All noncalcified cartilage was removed from the defects by lightly scraping the calcified cartilage surface using a curette, with the aid of loupe visualization. The autologous cell-seeded constructs were fit into the defects and secured using sutures. The knee joint was closed by zero point suturing.

The knee was immobilized by external fixation (IMEX Veterinary, Longview, TX) for the first 8 days after surgery, followed by normal ambulation until sacrifice, planned for 8 weeks postoperative.

Histological and immunohistochemical evaluation

Constructs cultured in vitro and allocated for histology were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin. In vivo samples, which consisted of reparative tissue filling the original defect sites as well as surrounding cartilage and bone, were removed from the joints, fixed in 10% formalin, and decalcified using ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid. All samples were processed and embedded in paraffin, and sectioned by microtomy. The sections were mounted on glass slides and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Safranin-O using standard histological techniques.

Type I and II collagen distributions were examined immunohistochemically using an anti-type I collagen mouse monoclonal antibody (I-8H5 CP17, final concentration of 5 μg/mL; Calbiochem, Gibbstown, NJ) and an anti-type II collagen mouse monoclonal antibody (CIIC1, final concentration 4 μg/mL; Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA). Staining for lubricin was done using anti-lubricin mouse monoclonal (S.679, final concentration 4.6 μg/mL; Dr. T. Schmid, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL). Laminin and type IV collagen were also examined immunohistochemically, using an anti-laminin rabbit polyclonal antibody (final concentration 27 μg/mL; Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and an anti-type IV collagen rabbit polyclonal antibody (final concentration 17 μg/mL; Abcam). The laminin antibody used was created against a protein purified from the basement membrane of Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma and not to a specific isoform of laminin. All staining was performed using the Dako Autostainer (DakoCytomation, Carpinteria, CA) and the peroxidase-aminoethyl carbazole-based Envision+ kit (Dako) following the manufacturer's recommendations.

Histomorphometry

Histomorphometric analysis of specific tissue types filling the defect was carried out on one H&E-stained section from the center portion of each defect. Previous work found that the interobserver error associated with this quantitative histological method was generally less than the interanimal variation in the results.17 Digital micrographs were taken of the defect and surrounding tissues. The total cross-sectional area of the original defect and the percentages of fibrous tissue, fibrocartilage, and hyaline cartilage filling the original defect were measured using ImageJ software (NIH, Bethesda, MD). Tissue types were classified according to the textbook appearance of cell morphology and extracellular matrix structure as previously described.16 In many of the samples, surrounding cartilage flowed into the peripheral areas of the defect. These regions were classified separately as matrix flow. When the percentages do not add up to 100%, it is due to rounding of values.

Quantitative evaluation of tissue bonding

The linear percentages of the base of the defect to which the healing tissue was bonded and of the height of the edges of the repair tissue on the left and right sides of the defect in apposition with adjacent cartilage (divided by the total height of the repair tissue) were measured on the digital micrographs using ImageJ software (NIH).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean±standard error of the mean. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed using StatView software (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). Statistical significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

Biochemical analysis of DNA and GAG content of the in vitro constructs

One day after seeding, the average number of chondrocytes in the cell-seeded scaffolds (n=24) was 2.0±0.2 million cells, compared to the 4 million cells seeded. This indicates that ∼50% of the cells were retained in the scaffolds 1 day postseeding. At the time of implantation, after 35 days of culture, the average number of chondrocytes in the cell-seeded scaffolds (n=22) increased to 3.5±0.2 million cells. One-factor ANOVA indicated a significant effect of culture time (p<0.0001, power=1) on the cell number.

One day after seeding, the average GAG density (GAG content per volume) of the constructs (n=24) was 13±1% of that in native cartilage. At the time of implantation, after 35 days of culture, the average GAG density (n=22) was much higher, at 88±7%. One-factor ANOVA indicated a significant effect of culture time (p<0.0001, power=1) on the GAG percentage.

Histological and immunohistochemical evaluation of the in vitro constructs

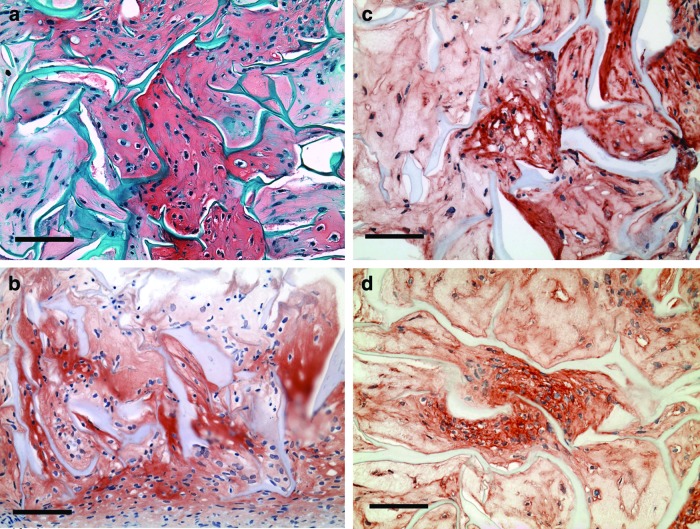

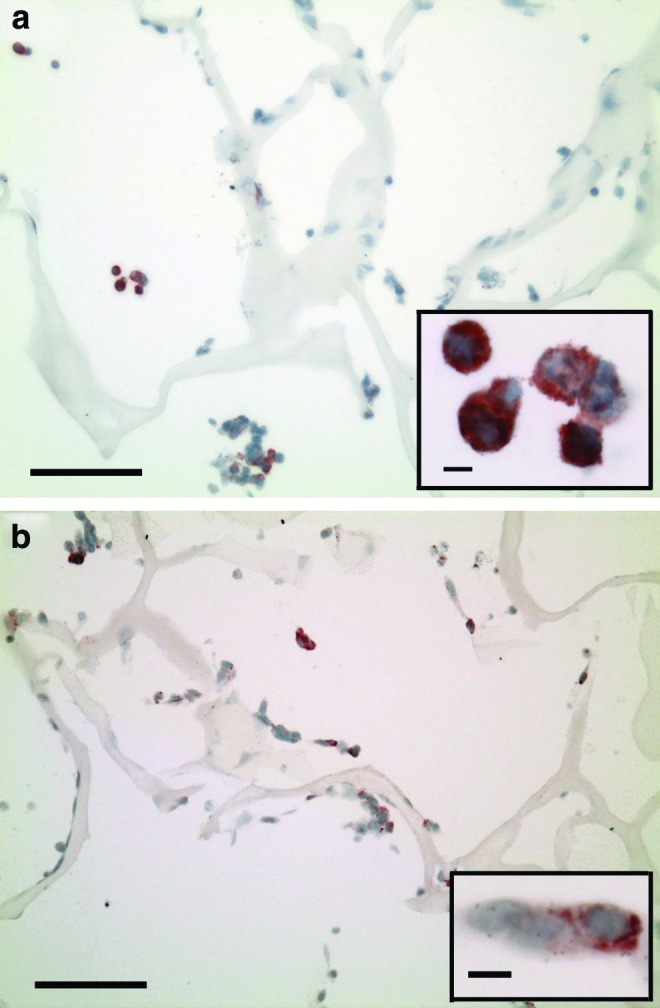

Immunohistochemical evaluation of the cell-seeded constructs collected 1 day postseeding revealed cells distributed throughout porous scaffolds (Fig. 1a, b). Of note was the positive intracellular staining for laminin (Fig. 1a) and type IV collagen (Fig. 1b), suggesting that some of the cultured chondrocytes were synthesizing these basement membrane molecules in vitro. No notable staining for laminin or type IV collagen was observed on the collagen scaffold itself.

FIG. 1.

In vitro cultured constructs, 1 day postseeding. (a) Laminin (red chromogen indicates positive stain); scale bar, 100 μm. Inset shows cells at higher magnification; scale bar, 5 μm. (b) Type IV collagen (red chromogen indicates positive stain); scale bar, 100 μm. Inset shows higher magnification; scale bar, 5 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Constructs collected at the time of implantation revealed cells, many rounded and in lacunae, residing in the newly synthesized extracellular matrix (Fig. 2a). Residual struts of the collagen scaffold could be seen (Fig. 2a). The newly synthesized extracellular matrix stained for sulfated GAGs (Fig. 2a) and type II collagen (Fig. 2b). Interestingly, large areas of the extracellular matrix also stained for laminin (Fig. 2c) and type IV collagen (Fig. 2d); the residual collagen struts did not stain for type I or II collagen (Fig. 2c, d). Little to no positive staining for lubricin was seen in the in vitro cultured constructs (data not shown).

FIG. 2.

In vitro cultured constructs at the time of implantation, 35 days postseeding. (a) Safranin O (red chromogen indicates sulfated glycosaminoglycans [GAGs]). Scale bar, 100 μm. (b) Type II collagen (red chromogen indicates positive stain). Scale bar, 100 μm. (c) Laminin (red chromogen indicates positive stain). Scale bar, 100 μm. (d) Type IV collagen (red chromogen indicates positive stain). Scale bar, 100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

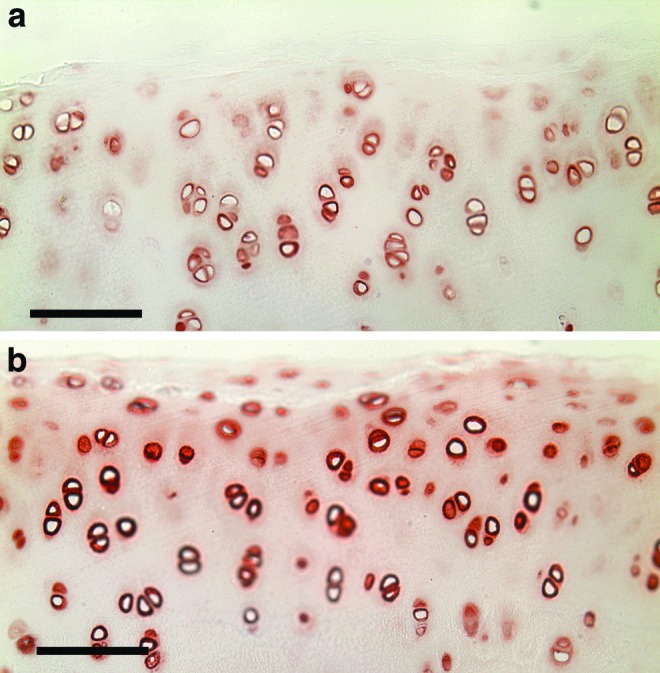

Laminin and type IV collagen distribution in normal goat articular cartilage

Both laminin and type IV collagen were observed in normal goat articular cartilage, staining colocally as an intense and distinct layer in the pericellular matrix (Fig. 3a, b). Faint staining was also observed around many of the cells in the territorial matrix, while negligible staining was seen in the interterritorial matrix (Fig. 3a, b).

FIG. 3.

Normal goat articular cartilage. (a) Laminin (red chromogen indicates positive stain). Scale bar, 100 μm. (b) Type IV collagen (red chromogen indicates positive stain). Scale bar, 100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

Qualitative gross and histological assessment of the in vivo cartilage repair

One animal died at 7 weeks, before reaching the planned sacrifice time of 8 weeks, unrelated to the cartilage repair; the two defects from this animal were collected and processed in the same manner as those from the other animals, and the data were recorded as 7-week data. The other three animals went to term.

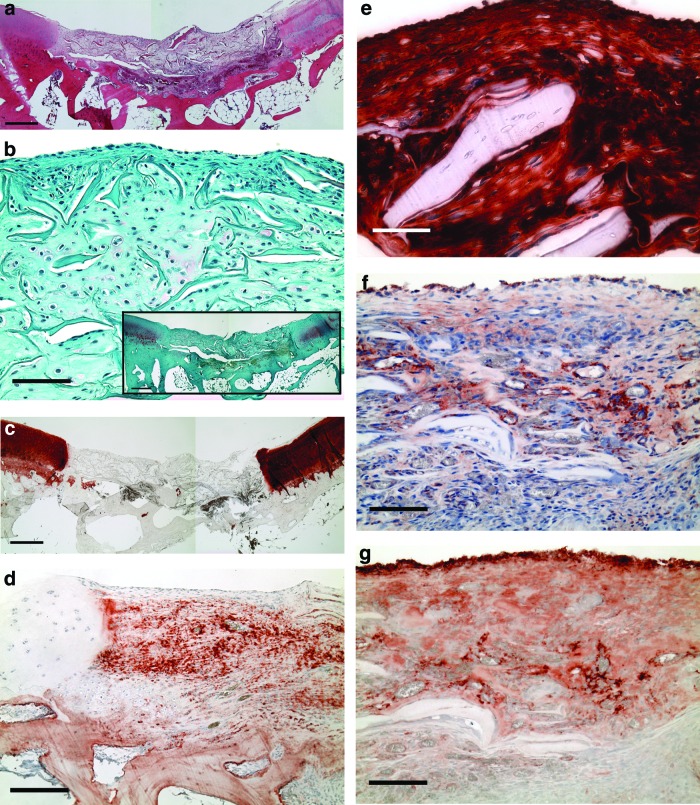

Gross examination revealed normal joint condition at sacrifice. All defect sites were clearly identifiable, and the surrounding cartilage appeared mostly normal (Fig. 4a). Residual collagen struts from the implanted scaffolds could be observed in some of the defects (Fig. 4a).

FIG. 4.

In vivo reparative tissue, 7–8 weeks postsurgery. (a) Hematoxylin & eosin. Scale bar, 500 μm. (b) Safranin O (red chromogen indicates sulfated GAGs). Scale bar, 100 μm. Inset shows the section at lower magnification, scale bar, 500 μm. (c) Type II collagen (red chromogen indicates positive stain). Scale bar, 500 μm. (d) Type I collagen (red chromogen indicates positive stain). Scale bar, 200 μm. (e) Lubricin (red chromogen indicates positive stain). Scale bar, 50 μm. (f) Laminin (red chromogen indicates positive stain). Scale bar, 100 μm. (g) Type IV collagen (red chromogen indicates positive stain). Scale bar, 100 μm. Color images available online at www.liebertpub.com/tea

The staining patterns for sulfated GAGs and type II collagen were similar. Some positive staining for sulfated GAGs was seen in the extracellular matrix, typically in the middle and deep zones of the surrounding articular cartilage, while little to no staining was observed in the reparative tissue (Fig. 4b). Intense positive staining for type II collagen was observed throughout the extracellular matrix of the cartilage surrounding the defect site (Fig. 4c). There was no notable staining for type II collagen in the reparative tissue (Fig. 4c).

Positive staining for type I collagen was present in large areas of the extracellular matrix of the reparative tissue filling the defect sites (Fig. 4d).

Lubricin was also noted in the reparative tissue (Fig. 4e). Staining intensity varied from sample to sample, but was generally seen on the surface of the reparative tissue and throughout the extracellular matrix. Discrete surface staining was also noted on the residual collagen struts. This was in contrast to the staining of the surrounding articular cartilage, in which, lubricin was limited to the superficial zone (data not shown).

Of note was the presence of laminin (Fig. 4f) and in all of the samples type IV collagen (Fig. 4g) in the in vivo reparative tissue. Intense staining was seen on the surface and surrounding some of the newly forming blood vessels in the reparative tissue. Diffuse staining was also noted throughout large areas of the extracellular matrix and in large percentages of the articular surface layer of the reparative tissue, clearly unrelated to the basement membrane of blood vessels.

Histomorphometric evaluation of reparative tissue

On average, 69±5% of the defect site was filled with reparative tissue 7–8 weeks postimplantation (n=8 defects). The reparative tissue consisted primarily of fibrous tissue (57±5% of the original defect area) and a small amount of fibrocartilage (6±2%). No hyaline cartilage was found filling the defects. A negligible amount of matrix flow (<4% of the total defect site) was noted.

Two-factor ANOVA failed to find a significant effect of defect location (proximal or distal) on the percentages of fibrocartilage (p=0.83, power=0.05), fibrous tissue (p=0.13, power=0.30), matrix flow (p=0.31, power=0.15), or total fill (p=0.13, power=0.30). ANOVA also revealed no significant effect of survival time on any of the outcome variables (p>0.05).

Quantitative evaluation of the bonding of the reparative tissue to the adjacent tissue

Nearly complete bonding was noted between the left (91±5%) and right (87±7%) sides of the reparative tissue and the surrounding cartilage 7–8 weeks postimplantation. Significant bonding was also observed at the base of the reparative tissue (72±8%).

Discussion

In this study, we engineered cartilaginous constructs in vitro and implanted them into chondral defects in the goat knee, after 35 days of culture when the GAG density was almost 90% of normal and a substantial amount of type II collagen was present. A novel finding of this study was the observation of laminin and type IV collagen, two common basement membrane molecules, in both in vitro engineered cartilaginous constructs and in vivo cartilage repair samples, as well as in normal caprine articular cartilage. The pericellular staining pattern observed in native goat articular cartilage in this study was similar to what has been reported in the literature for other species, including cow,7 mouse,7,8 and human.6 In contrast, widespread and extensive staining for the two molecules was observed throughout the extracellular matrix of our in vitro and in vivo samples, different than the localized pericellular staining pattern seen in normal adult articular cartilage, underscoring the difference in the make-up of our engineered constructs and reparative tissue compared to normal articular cartilage.

Chondrocytes cultured in vitro in this study were shown to be capable of synthesizing laminin and type IV collagen, even though a number of the cells appeared morphologically to be dedifferentiated. This is in agreement with previous work showing that chondrocytes can synthesize the two molecules in vitro.18 It has also been shown that chondrocytes can synthesize the molecules in vivo7; however, the source of the laminin and type IV collagen in the reparative tissue in this study was not investigated.

It is of interest to note that diffuse generalized staining for many basement membrane molecules, including laminin, type IV collagen, and perlecan, has been reported throughout the extracellular matrix during knee joint maturation, with no apparent organization of the molecules in the pericellular matrix.7,12 Additionally, staining for perlecan in osteoarthritic cartilage is also not localized to the pericellular matrix, and has been reported in the interterritorial matrix.19 The similarity in staining patterns seen in our study and in maturing and osteoarthritic cartilage may suggest that aspects of the cartilage repair process are recapitulating either normal joint maturation or matrix remodeling events and repair following the onset of osteoarthritis.

This study and others have demonstrated that normal adult articular cartilage chondrocytes are surrounded by common basement membrane molecules in the pericellular matrix, suggesting that the pericellular matrix may be the functional equivalent of a basement membrane.6–13 It is thought that this functional basement membrane may have important structural and organizational roles in normal articular cartilage. For example, perlecan has been shown to interact with a number of anchoring and fibrillar proteins in the cartilage extracellular matrix.12 Chondrocytes have also been shown to express several cell surface integrins that bind type IV collagen, laminin, and perlecan, and the basement membrane components may play important roles in chondrocyte survival and differentiation and may aid cells in sensing and responding to changes in their biomechanical environment by modulating signal transduction events.7,12 Future work is needed to elucidate the role of basement membrane molecules during cartilage repair and regeneration.

At the time of implantation, the constructs completely filled the defects with the articulating surface at least at the level of the surrounding articular cartilage. At sacrifice 7–8 weeks postimplantation, however, only 70% of the defect site was filled with reparative tissue, which consisted largely of fibrous tissue and some fibrocartilage. The decrease in the percentage of the defect filled by the construct may have been due to its mechanical compression and to some degradation. The presence of a substantial amount of the collagen scaffold in the defects at the time of sacrifice suggested that most of the implanted construct had not undergone degradation and replacement with newly formed tissue (i.e., the construct had not undergone remodeling). There was virtually no staining for GAG or type II collagen in the tissue in the defect, in contrast to the histologic makeup of the constructs that were implanted. The histology of the defects after 7–8 weeks was consistent with depletion of GAG and type II collagen in the implanted construct, and a change in the phenotype of the cells with their synthesis of type I collagen. On a positive note, over 70% of the reparative tissue filling the microscopic gap between the construct and surrounding host cartilage appeared to be bonded to the adjacent host tissue. Also of note was that the essential boundary lubricating glycoprotein, lubricin, was found in the articulating surface layer of in vivo samples, despite the fact that little to no lubricin was seen in the constructs in vitro. This result raises the question of how the reparative tissue would function tribologically. These findings underscore the challenge of determining the degree to which, tissue-engineered constructs should be allowed to mature in vitro before implantation.

The current cell-seeded constructs matured in vitro yielded results generally comparable to other cell-based methods. Earlier work in which the same type of defect in a canine model was treated using autologous chondrocyte implantation resulted in 41±10% total fill after 1.5 months, and 48±6.5% total fill and up to 76±12% bonding after 3 months.17 Breinan et al.2 showed that autologous chondrocyte-seeded type II collagen matrices implanted in chondral defects in dog knees within 12 h of seeding yielded 62±13% filling of the defect site and 34±8% bonding to the adjacent cartilage after 15 weeks. Lee et al.3 found that chondrocyte-seeded type II collagen matrices implanted in dogs after 4 weeks of in vitro culture resulted in 88±6% filling of the defect site and 64±12% bonding to the adjacent tissue after 15 weeks. While the total fill seen in this study is slightly lower than what was seen in the study with 4 weeks of in vitro culture, it should be noted that differences existed in the in vitro culture conditions between the two studies, likely resulting in different GAG densities at implantation, and that the longer animal survival time in the study with 4 weeks of in vitro culture may have allowed for the formation of the additional reparative tissue seen. It is recognized that 8 weeks is an early time point for assessing cartilage repair in goats, and that the healing process may not be complete. Future work could benefit from longer time points, to assess the long-term effects of the cell-seeded constructs in cartilage repair.

The results of this study are at least as good as results from previous work in our laboratory examining untreated defects, microfracture-treated defects, and defects implanted with scaffolds alone. Breinan et al.17 found that untreated defects in the canine trochlear groove were 41±4.3% filled with reparative tissue 1.5 months after defect creation, with the majority of the reparative tissue consisting of tissue that was fibrous in nature and not hyaline cartilage. In the same study, 34±6.9% of the untreated defect was filled with reparative tissue after 3 months.17 Another study examining microfracture-treated chondral defects in the trochlear groove of dogs found that 56±12% of the defect site was filled with reparative tissue 15 weeks after treatment, all of it consisting of tissue fibrous in nature.2 Nehrer et al. evaluated chondral defects implanted with collagen scaffolds and found that 37±7% of the defects were filled after 15 weeks, with none of the reparative tissue consisting of hyaline cartilage.20 Similar to the previously reported control groups, our study also showed that the majority of the reparative tissue filling the defect site was fibrous in nature. Our study resulted in the greatest percentage of total fill compared to our previous work; however, it should be noted that there were differences among the studies that may have affected the outcomes.

The goat animal model was chosen for this study for reasons of: articular cartilage thickness (∼1 mm), which more closely approaches the thickness found in humans compared with smaller laboratory animal models, such as rabbits (typically <0.5 mm); and the loading of the joint.21 Goats are commonly employed for cartilage repair studies, and recent work using this animal model has demonstrated its value for investigating cartilage repair.22–28

In summary, we report on the notable finding of laminin and type IV collagen in both in vitro engineered cartilaginous constructs and in vivo cartilage repair samples, as well as in normal caprine articular cartilage. These findings will be of value in furthering the understanding of cartilage biology, pathophysiology, and repair.

Funding Declaration

This work was supported by the Rehabilitation Research and Development Service of the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs; the Department of Defense; the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (L. Jeng); and the Siebel Scholarship (L. Jeng). M. Spector was supported by a VA Research Career Scientist Award.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the assistance of Alix Weaver, and gratefully acknowledge receipt of the anti-lubricin antibody from T.M. Schmid, Rush University Medical Center, Chicago, IL.

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- 1.Pfeiffer E. Vickers S.M. Frank E. Grodzinsky A.J. Spector M. The effects of glycosaminoglycan content on the compressive modulus of cartilage engineered in type II collagen scaffolds. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2008;16:1237. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breinan H.A. Martin S.D. Hsu H.P. Spector M. Healing of canine articular cartilage defects treated with microfracture, a type-II collagen matrix, or cultured autologous chondrocytes. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:781. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee C.R. Grodzinsky A.J. Hsu H.P. Spector M. Effects of a cultured autologous chondrocyte-seeded type II collagen scaffold on the healing of a chondral defect in a canine model. J Orthop Res. 2003;21:272. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(02)00153-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schmidt T.A. Gastelum N.S. Nguyen Q.T. Schumacher B.L. Sah R.L. Boundary lubrication of articular cartilage—role of synovial fluid constituents. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:882. doi: 10.1002/art.22446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Erickson A.C. Couchman J.R. Still more complexity in mammalian basement membranes. J Histochem Cytochem. 2000;48:1291. doi: 10.1177/002215540004801001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Durr J. Lammi P. Goodman S.L. Aigner T. von der Mark K. Identification and immunolocalization of laminin in cartilage. Exp Cell Res. 1996;222:225. doi: 10.1006/excr.1996.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kvist A.J. Nystrom A. Hultenby K. Sasaki T. Talts J.F. Aspberg A. The major basement membrane components localize to the chondrocyte pericellular matrix—a cartilage basement membrane equivalent? Matrix Biol. 2008;27:22. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lee S.K. Malpeli M. Cancedda R. Utani A. Yamada Y. Kleinman H.K. Laminin chain expression by chick chondrocytes and mouse cartilaginous tissues in vivo and in vitro. Exp Cell Res. 1997;236:212. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vincent T.L. McLean C.J. Full L.E. Peston D. Saklatvala J. FGF-2 is bound to perlecan in the pericellular matrix of articular cartilage, where it acts as a chondrocyte mechanotransducer. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:752. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2007.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chia S.L. Sawaji Y. Burleigh A. McLean C. Inglis J. Saklatvala J. Vincent T. Fibroblast growth factor 2 is an intrinsic chondroprotective agent that suppresses ADAMTS-5 and delays cartilage degradation in murine osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2019. doi: 10.1002/art.24654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iozzo R.V. Cohen I.R. Grassel S. Murdoch A.D. The biology of perlecan: the multifaceted heparan sulphate proteoglycan of basement membranes and pericellular matrices. Biochem J. 1994;302:625. doi: 10.1042/bj3020625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Melrose J. Smith S. Cake M. Read R. Whitelock J. Perlecan displays variable spatial and temporal immunolocalisation patterns in the articular and growth plate cartilages of the ovine stifle joint. Histochem Cell Biol. 2005;123:561. doi: 10.1007/s00418-005-0789-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pufe T. Petersen W.J. Miosge N. Goldring M.B. Mentlein R. Varoga D.J. Tillmann B.N. Endostatin/collagen XVIII—an inhibitor of angiogenesis—is expressed in cartilage and fibrocartilage. Matrix Biol. 2004;23:267. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vickers S.M. Squitieri L.S. Spector M. Effects of cross-linking type II collagen-GAG scaffolds on chondrogenesis in vitro: dynamic pore reduction promotes cartilage formation. Tissue Eng. 2006;12:1345. doi: 10.1089/ten.2006.12.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim Y.J. Sah R.L.Y. Doong J.Y.H. Grodzinsky A.J. Fluorometric assay of DNA in cartilage explants using Hoechst-33258. Anal Biochem. 1988;174:168. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90532-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Breinan H.A. Minas T. Hsu H.P. Nehrer S. Sledge C.B. Spector M. Effect of cultured autologous chondrocytes on repair of chondral defects in a canine model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1439. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199710000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breinan H.A. Minas T. Hsu H.P. Nehrer S. Shortkroff S. Spector M. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in a canine model: change in composition of reparative tissue with time. J Orthop Res. 2001;19:482. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(00)90015-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ulbrich C. Westphal K. Pietsch J. Winkler H.D.F. Leder A. Bauer J. Kossmehl P. Grosse J. Schoenberger J. Infanger M. Egli M. Grimm D. Characterization of human chondrocytes exposed to simulated microgravity. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2010;25:551. doi: 10.1159/000303059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tesche F. Miosge N. Perlecan in late stages of osteoarthritis of the human knee joint. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2004;12:852. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nehrer S. Breinan H.A. Ramappa A. Hsu H.P. Minas T. Shortkroff S. Sledge C.B. Yannas I.V. Spector M. Chondrocyte-seeded collagen matrices implanted in a chondral defect in a canine model. Biomaterials. 1998;19:2313. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(98)00143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Breinan H.A. Hsu H.P. Spector M. Chondral defects in animal models: effects of selected repair procedures in canines. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;391(Suppl):S219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jackson D.W. Lalor P.A. Aberman H.M. Simon T.M. Spontaneous repair of full-thickness defects of articular cartilage in a goat model. A preliminary study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2001;83-A:53. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200101000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Driesang I.M. Hunziker E.B. Delamination rates of tissue flaps used in articular cartilage repair. J Orthop Res. 2000;18:909. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100180609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jackson D.W. Halbrecht J. Proctor C. Van Sickle D. Simon T.M. Assessment of donor cell and matrix survival in fresh articular cartilage allografts in a goat model. J Orthop Res. 1996;14:255. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100140214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Butnariu-Ephrat M. Robinson D. Mendes D.G. Halperin N. Nevo Z. Resurfacing of goat articular cartilage by chondrocytes derived from bone marrow. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;330:234. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199609000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Athanasiou K. Korvick D. Schenck R. Biodegradable implants for the treatment of osteochondral defects in a goat model. Tissue Eng. 1997;3:363. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shahgaldi B.F. Amis A.A. Heatley F.W. McDowell J. Bentley G. Repair of cartilage lesions using biological implants—a comparative histological and biomechanical study in goats. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73:57. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B1.1991776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chu C.R. Szczodry M. Bruno S. Animal models for cartilage regeneration and repair. Tissue Eng Part B Rev. 2010;16:105. doi: 10.1089/ten.teb.2009.0452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]