Abstract

Objective

To compare in vitro three-dimensional (3D) culture systems that model chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs).

Methods

MSCs from five horses 2–3 years of age were consolidated in fibrin 0.3% alginate, 1.2% alginate, 2.5×105 cell pellets, 5×105 cell pellets, and 2% agarose, and maintained in chondrogenic medium with supplemental TGF-β1 for 4 weeks. Pellets and media were tested at days 1, 14, and 28 for gene expression of markers of chondrogenic maturation and hypertrophy (ACAN, COL2B, COL10, SOX9, 18S), and evaluated by histology (hematoxylin and eosin, Toluidine Blue) and immunohistochemistry (collagen type II and X).

Results

alginate, fibrin alginate (FA), and both pellet culture systems resulted in chondrogenic transformation. Adequate RNA was not obtained from agarose cultures at any time point. There was increased COL2B, ACAN, and SOX9 expression on day 14 from both pellet culture systems. On day 28, increased expression of COL2B was maintained in 5×105 cell pellets and there was no difference in ACAN and SOX9 between FA and both pellet cultures. COL10 expression was significantly lower in FA cultures on day 28. Collagen type II was abundantly formed in all culture systems except alginate and collagen type X was least in FA hydrogels.

Conclusion

equine MSCs respond to 3D culture in FA blended hydrogel and both pellet culture systems with chondrogenic induction. For prevention of terminal differentiation and hypertrophy, FA culture may be superior to pellet culture systems.

Introduction

Osteoarthritis is common in man and animals alike1 and is often a sequelae to focal articular cartilage injury.2,3 Cell-based therapy for the repair of articular cartilage injury4–6 has been pursued due to the poor intrinsic healing of injured cartilage,2 the poor long-term response to surgical therapies,7 and the lack of effective disease-modifying osteoarthritis drugs.8,9 Repair with chondrocyte grafts improves long-term outcome,10 but must be either allogeneic, with risk of immune rejection,11,12 or autologous, with donor-site morbidity and added complexity.13 Adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) are a stem cell source for autologous cell transplantation to musculoskeletal tissues with minimal donor-site morbidity, and good proliferative and chondrogenic potential.14–16 MSCs have been utilized for joint tissue regeneration in horses indirectly through intra-articular injection after microfracture,17 and directly with the arthroscopic application of concentrated bone marrow grafts to focal cartilage defects18 and implantation of culture-expanded MSC grafts.19–22 However, several authors consider that MSCs are inferior to chondrocytes for cartilage defect repair because they are unable to attain the chondrocyte phenotype following implantation.22,23 Many studies have evaluated culture additives and conditions that might drive chondrogenesis of MSCs in vivo, however, long-term outcome data suggest that fibrous tissue persists throughout the repaired defect.22 Additional work using culture models that more completely mimic the in vivo conditions experienced by implanted MSCs may better discern methods to drive more hyaline-like tissue after joint repair by MSC grafting.

For chondrogenic induction of MSCs, transforming growth factor beta supplementation of a defined serum-free medium in a three-dimensional (3D) pellet culture is used routinely in vitro and has been well characterized for several species.15,16,24 Pellet culture is a stable, biomaterial-free culture system and is the gold standard for both chondrocyte re-differentiation studies as well as MSC differentiation studies in vitro. However, several investigators report that bone marrow-derived MSCs from many species, including equine, have poor long-term survival in pellet culture, with apoptosis and necrosis of central cells, poor RNA quality and quantity, and reduced total chondrogenesis.25 To fully evaluate in vitro methods to optimize MSC chondrogenesis, a 3D system that will allow cell survival, growth, differentiation, and matrix production for at least 1 month is required.

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effect of differing 3D culture systems on MSC chondrogenesis in long-term in vitro culture. We used 3D systems that have been characterized to induce MSC chondrogenesis in various species; pellet culture, agarose, alginate, and fibrin alginate (FA) hydrogel composites.16,26–29 Identification and use of the best system will allow better characterization of MSC chondrogenesis and methods to improve it. Further, the best system may also elucidate methods to enhance in vivo MSC survival and engraftment.

Materials and Methods

Study design

Bone marrow-derived MSCs from five horses were isolated, expanded, and dispensed to each culture condition and maintained in the chondrogenic medium (CM). Pellets and supernatant media were collected on days 1, 14, and 28 for gene expression of selected marker genes and routine histology. This study was approved by the Institution's Animal Care and Use Committee.

Bone marrow collection and MSC isolation

Bone marrow aspirates were obtained from the sternum of five horses, 2–3 years of age.30 Local anesthesia and light sedation was used for bone marrow collection. Bone marrow biopsy needles (Jamshidi; VWR Scientific) were used to aspirate bone marrow into four 60-mL syringes containing heparin (APP Pharmaceuticals, LLC) for a final concentration of 1000 units/mL. Each 60 mL was collected from a separate site with advancement of the Jamshidi needle after each 15 mL of marrow had been drawn. Bone marrow aspirate was diluted 1:1 in the growth medium (Dulbecco's modified Eagle's media; 1000 mg/L glucose; 2 mM l-glutamine; 100 units/mL penicillin–streptomycin; 1 ng/mL bFGF; 10% fetal calf serum) and 60 mL was plated to T-175 tissue culture flasks, and maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity in room air. Nonadherent cells were removed through daily feeding. Once colony formation was evident, adherent cells were passaged using trypsin and replated at 20,000 cells/cm2, and fed every other day. Monolayer cultures were passaged a second time when plates were 80%–90% confluent. When passage 2 cultures were 80%–90% confluent, adherent MSCs from each horse were cryopreserved.

At the start of the in vitro experiment, cryopreserved MSCs were plated in monolayer culture at 20,000 cells/cm2. When cultures were 85% confluent, cells from each horse were trypsinized, counted, and aliquoted to each group.

Fibrin alginate

For culture in a FA scaffold, cells were resuspended to 10×106 cells/mL in 30 mg/mL fibrinogen in Dulbecco's phosphate-buffered saline (dPBS) and mixed 1:1 with 0.6% alginate (ultrapure low-viscosity 67% guluronate, UPLVG, NovaMatrix, FMC Corporation) for a final concentration of 0.3% alginate. Allogeneic fibrinogen had been cryoprecipitated from plasma collected from horses using a technique previously described.31 For scaffold polymerization, the cell suspension was dropped via a 19 gauge 1.5 inch needle into 102 mM CaCl2 with 5 units/mL bovine thrombin, for ∼150,000 cells per bead. After 10 min, the CaCl2 solution was aspirated and FA beads were rinsed three times in dPBS.

Alginate culture

For culture in a pure alginate scaffold, cells were resuspended to 10×106 cells/mL in dPBS and mixed 1:1 with 2.4% alginate (ultrapure low-viscosity 67% guluronate, UPLVG; NovaMatrix, FMC Corporation) in dPBS for a final concentration of 1.2% alginate. For scaffold polymerization, the cell suspension was dropped via a 19 gauge 1.5 inch needle into 102 mM CaCl2 for ∼125,000 cells per alginate bead. After 5 min, CaCl2 was aspirated and beads were rinsed three times with dPBS.

Agarose

For culture in an agarose (Ultra-Pure LMP Agarose; Invitrogen) scaffold, cells were resuspended to 60×106 cells/mL in dPBS and mixed 1:1.5 with 3% agarose in dPBS for a final concentration of 2% agarose. Low-melting temperature agarose was maintained at 38°C during cell preparation. The agarose MSC suspension was then dispensed to a casting frame (10-cm Petri dish) to a thickness of 1.6 mm and allowed to polymerize at room temperature for 10 min. Once polymerized, a 6-mm biopsy punch was used to cut discs containing ∼1.8×106 cells per disk.

Pellet culture

MSCs were resuspended to 2×106 cells/mL and 1×106 cells/mL in the CM. Aliquots of 250 μL were dispensed to wells of 96-well, v-bottom, polypropylene plates (PHENIX Research Products). Plates were spun in a swinging bucket rotor at 400g for 10 min for pellet formation of 2.5×105 cells per pellet and 5×105 cells per pellet.

Three-dimensional culture

Each group was maintained in the CM (high-glucose DMEM; 12.5 mL/500 mL HEPES buffer; 100 nM dexamethasone; 50 μg/mL ascorbate 2 phosphate; 100 μg/mL sodium pyruvate; 40 μg/mL proline; 1×ITS+; 100 IU/mL penicillin–streptomycin) supplemented with 10 ng/mL TGF-β1 (Recombinant Human TGF-β1; Gibco Invitrogen). Two hundred microliters of the CM was exchanged daily and all culture systems were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 95% humidity in room air until the harvest time point at day 1, 14, or 28. All culture systems were maintained in wells of 12-well polypropylene plates except pellet cultures, which were maintained in polypropylene 96-well plates from pellet initiation.

For scaffold dissolution and RNA isolation at the end of the culture period, FA beads were rinsed once in dPBS, incubated 120 min at 37°C in 0.25% bacterial collagenase (Sigma) in dPBS, vortexed, and then incubated until dissolved (5–15 min) at 37°C in a reconstruction buffer (50 mM EDTA, 10 mM HEPES at pH 7.4), vortexed, and centrifuged at 470 g for 5 min. The resulting cell pellet was washed three times in dPBS and frozen at −80°C in the RNA lysis solution. Alginate beads were rinsed once in dPBS, incubated until dissolved (5–15 min) at 37°C in the reconstruction buffer, vortexed, and centrifuged at 470 g for 5 min. The resulting cell pellet was washed three times in dPBS and frozen at −80°C in the RNA lysis solution. Alginate beads at day 14 and 21 required pretreatment with 0.25% bacterial collagenase in addition to the reconstruction buffer, similar to dissolution for FA beads. Pellets and agarose cultures were pulverized with a mortar and pestle, while immersed in the lysis buffer and kept on ice. All samples were collected and frozen (−80°C) in the lysis buffer for RNA isolation at a later time. Each culture product was homogenized with a commercial homogenizer solution (Qiashredder; Qiagen) followed by RNA extraction with a commercial kit (RNeasy® Plus Mini Kit; Qiagen). Genomic DNA was removed from RNA samples before polymerase chain reaction (PCR) by selective filter centrifugation.

Gene expression

Six pellets, beads or discs from each group and horse were isolated at each time point (days 1, 14, or 28) with a combination of two per sample, for an n=3 for each group, horse, and time point. For quantitative PCR (qPCR), the primers and dual-labeled fluorescent probes (6-FAM as the 5′ label [reporter dye] and TAMRA as the 3′ label [quenching dye]) were designed using Primer Express Software version 2.0b8a (Applied Biosystems) using equine-specific sequences published in GenBank: 18S-Fwd CGGCTTTGGTGACTCTAGATAACC 18S-Rev CCATGGTAGGCACAGCGACTA; COL2b-Fwd CGCTGTCCTTCGGTGTCA, COL2b-Rev CTTGATGTCTCCAGGTTCTCCTT; COL10a-Fwd GAGAACATGCTGCCACAAACA, COL10a-Rev TCAGCATAAAACTCGCCATGAA; ACAN-Fwd GATGCCACTGCCACAAAACA, ACAN-Rev GGGTTTCACTGTGAGGATCACA; SOX9-Fwd CAGGTGCTCAAGGGCTACGA, SOX9-Rev GACGTGAGGCTTGTTCTTGCT.

Total RNA was reverse transcribed and amplified using the One-Step reverse transcription-PCR technique and the ABI PRISM 7900HT Sequence Detection System (Applied Biosystems, Life Technologies). Samples for each molecule for each time point were assessed on the same qPCR plate to minimize variation. The qPCR program included reverse transcription at 48°C for 30 min and denaturing at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 cycles of 90°C for 15 s and 60°C for 1 min. Each well of the qPCR plate was loaded with 10 ng of RNA in 20 μL. Other than 18S, a standard curve was generated from equine-specific plasmid DNA for each gene at known concentrations to allow copy number estimation. All samples were run in duplicate on the qPCR plate and total copy number per 10 ng of RNA of each gene was obtained from a standard curve and normalized to 18S gene expression.

Histology

Two pellets, beads or discs per group, horse, and time point, were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 12 h. Cultures were then confined to a 2% agarose gel, processed and embedded in paraffin, sectioned (5 μm), and stained using standard procedures for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Toluidine Blue.

Immunohistochemistry

Sections for collagen immunohistochemistry were treated with 5 mg/mL hyaluronidase (Sigma Chemical Co.) at 37°C for 60 min, and the rat anti-human type II collagen primary antibody or rabbit anti-human type X collagen primary antibody, diluted 1:100 in PBS applied for 60 min. The secondary biotinylated goat anti-rat antibody (type II) or goat anti-rabbit antibody (type X; Super Sensitive Immunodetection System, Biogenex) was applied, followed by streptavidin-conjugated peroxidase to catalyze chromogen development in 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrachloride. Tissue sections were counter stained with hematoxylin, and examined by microscopy to determine type II and type X collagen distribution. Positive control samples for type II were derived from equine costochondral junctions, using the cartilaginous portion as a positive and the spongiosa as a negative control. Control samples for type X were derived from the equine fetal articular–epiphyseal cartilage. Each slide had serial sections included that were reacted with nonimmune serum, as procedural controls.

Statistical analysis

As data were not normally distributed, nonparametric tests were used. Differences between groups were detected by Kruskal–Wallis one-way ANOVA and the Dunn's multiple comparison test. Data were reported as a median and interquartile range. Statistical analyses were performed with commercially available software (Statistix 9) and the level of significance was set at p<0.05.

Results

MSC harvest and culture

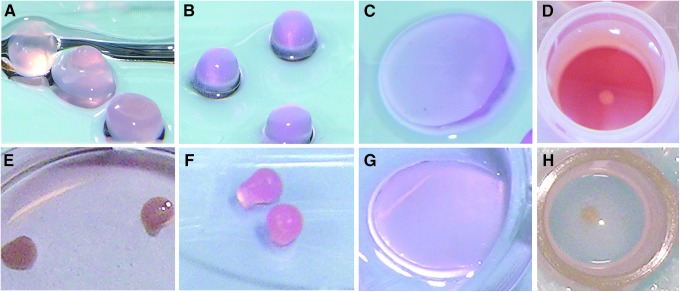

At least 100×106 passage 2 cells per horse were cryopreserved after primary cell harvest. Cells from all horses had good viability (>85%) postfreeze. Cell suspension in each scaffold or pellet culture was successful for all groups. By 1 week, FA and alginate cultures had become opaque and remained this way until harvest. Pellets (opaque and white) and agarose (translucent without color) did not change in color or translucency during the culture period (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Photographs of mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) three-dimensional (3D) constructs on day 1 (A, fibrin alginate [FA]; B, alginate; C, agarose; D, pellet) and day 28 (E, FA; F, alginate; G, agarose; H, pellet) of culture.

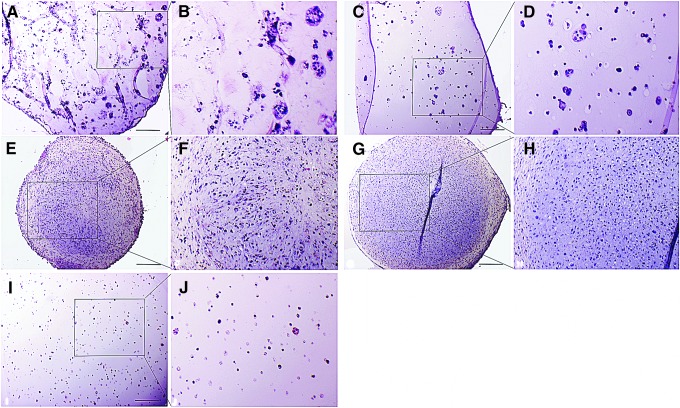

Histology

Morphology of the 3D constructs varied depending on whether the culture was a solid suspension such as alginate or agarose, where the MSCs formed small groups and clusters interspersed throughout the support, or a cell condensation such as the various sized pellet cultures, where cells were more tightly packed in a more tissue-like structure (Fig. 2). As a result, basophilic staining matrix accumulation was evident around small cell clusters in alginate derivatives, but more generalized throughout the MSC pellets, but particularly in the center. Agarose had fewer and smaller cell clusters and a minimal territorial matrix. This was verified by a toluidine histochemical reaction, where each group had toluidine-reactive matrix accumulation evident starting on day 14 and increasing on day 28. There was increased matrix staining in 2.5×105 pellets and 5×105 pellets compared to alginate and FA, and very little matrix accumulation in agarose on day 14 and 28. Within both pellet cultures, there was reduced matrix staining and obvious stratification with elongated cells and lacunae-like structures in the outer third of the pellets at day 28. The development of lacunae-like structures within the central region did not appear to be different between the different groups within each time point. Cellular migration within the scaffold, with subsequent clustering of cells was greatest at day 28 in alginate and FA cultures, and was occasionally present in agarose cultures, but was not noted in either 2.5×105 pellets or 5×105 pellets.

FIG. 2.

Photomicrographs of MSC 3D cultures collected at 28 days and stained with hematoxylin and eosin. (A, B) FA, (C, D) alginate, (E, F) 2.5×105 pellet, (G, H) 5×105 pellet, and (I, J) agarose. 200× magnification. Images were taken at 100× magnification. Black box represents area for magnified image adjacent to original. Scale bar=200 μm.

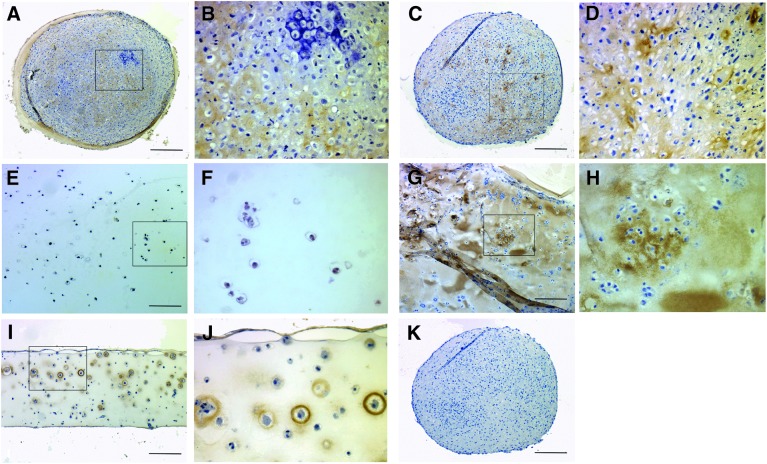

Immunohistochemistry

Collagen type II was abundantly expressed after 28 days in pellet culture and in FA hydrogels (Fig. 3). Collagen formation was widespread throughout the pellet cultures, but in FA culture was more obvious around larger clusters of cells. A thin zone of MSCs in the middle to deep region of agarose cultures also expressed collagen type II, while little collagen type II was evident in alginate cultures.

FIG. 3.

Collagen type II formation in MSC 3D cultures collected at 28 days. (A, B) 2.5×105 pellet, (C, D) 5×105 pellet (E, F) alginate, (G, H) FA, and (I, J) agarose. Collagen type II has formed throughout the FA and pellet cultures, but is not evident in alginate culture. Black box represents area for magnified image adjacent to original in all paired images. (K) Serial section from (C) after reaction with nonimmune serum. Scale bar=200 μm.

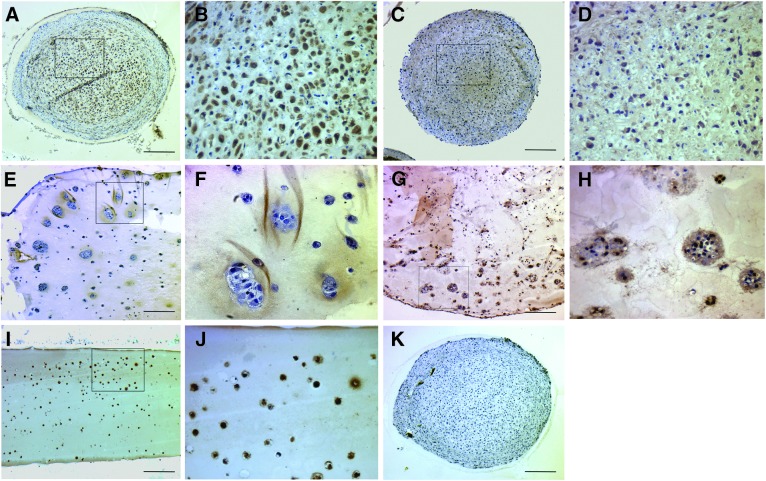

Collagen type X formation was evident in all culture systems, and was confined only to the cytoplasm and immediate pericellular matrix (Fig. 4). Formation was abundant in pellet culture and agarose culture systems. Alginate and FA hydrogels had less or no cellular and pericellular type X formation (Fig. 4).

FIG. 4.

Collagen type X formation in MSC 3D cultures collected at 28 days. (A, B) 2.5×105 pellet, (C, D) 5×105 pellet, (E, F) alginate, (G, H) FA, and (I, J) agarose. Collagen type X is formed in all culture systems, but less so in FA hydrogels. Black box represents area for magnified image adjacent to original in all paired images. (K) Serial section from (A) after reaction with nonimmune serum. Scale bar=200 μm.

Gene expression

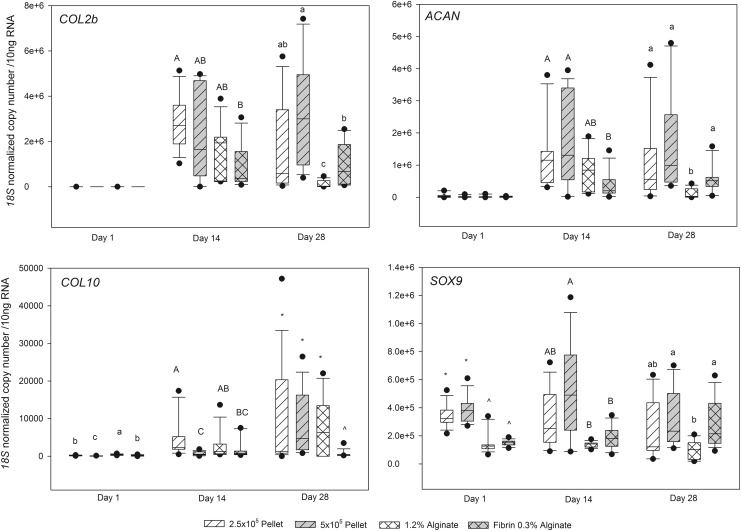

Good quality RNA was isolated from 3D cultures at all time points from all groups, other than agarose, with significant differences between groups in the total RNA isolated within each time point (Table 1). Sufficient quantities of RNA were not generated from agarose at any time point, and therefore RT-PCR was not performed on agarose samples. On day 14 and 28, but not day 1, there were significant differences between the groups in ACAN and COL2b expression. Expression of both was highest in 5×105 cell pellet cultures and lower in alginate and FA mixtures (Fig. 5). On day 1, 14, and 28, there were significant differences between the groups in COL10 and SOX9 expression, with FA having significantly lower COL10 abundance on day 14 and 28, and SOX9 being lower in alginate cultures on day 28 (Fig. 5).

Table 1.

Total RNA (μg/mL) in 35 μL from Mesenchymal Stem Cell Three-Dimensional Culture Systems

| |

Day 1 |

Day 14 |

Day 28 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | IQR | Median | IQR | Median | IQR | |

| Fibrin alginate | 94AB | 54–168 | 113A | 44–248 | 96A | 35–190 |

| Alginate | 48B | 41–55 | 10B | 9–17 | 30AB | 5–60 |

| Pellet 2.5 | 49AB | 38–70 | 18B | 14–24 | 10B | 5–15 |

| Pellet 5 | 121A | 91–144 | 20B | 13–23 | 12B | 8–18 |

| Agarose | 1C | 0–2 | 1C | 1–2 | 3C | 2–4 |

Superscript letters demonstrate statistically significant differences within each time point.

IQR, interquartile range.

FIG. 5.

Box plots of gene expression for COL2b, ACAN, COL10, and SOX9 from 3D cultures of MSCs. Differing superscript letters and symbols indicate statistical differences between groups within each time point.

Discussion

This study confirmed the utility of FA, alginate, and pellet culture, but not agarose, for long-term 3D culture of equine MSCs for studying chondrogenesis. The technical failure to retrieve RNA from agarose with sufficient quality or quantity for qPCR analysis of gene expression reduced the value of agarose as a culture scaffold. Lack of gene expression data certainly limited comparison of the cellular dynamics of agarose in contrast to the other systems in these experiments. Histologically, all culture conditions induced some degree of MSC chondrogenesis, confirmed by rounding of cells and formation of lacunae-like structures. Immunohistochemistry also indicated agarose supported formation of significant pericellular collagen type II and X at some stage during culture. In the remaining culture systems, FA, 2.5×105 pellet and 5×105 pellet systems were superior to alginate in chondrogenic induction, with increased ACAN and SOX9 expression. The biomaterial vehicle-free pellet culture systems were superior for chondrogenic induction on the basis of increased COL2b expression, and therefore may be best for the study of chondrogenesis.

The FA culture provided several compelling features. Although the FA scaffold had lower COL2b expression at 4 weeks compared to pellet culture, ACAN or SOX9 were no different, and COL10 was dramatically lower compared to all other systems. In vivo, collagen type 10 is produced by prehypertrophic and hypertrophic chondrocytes during chondrogenesis,32,33 and its expression is used as a marker of chondrocyte hypertrophy.34,35 It is not surprising that pellet culture induced COL10 expression, as the cell to cell interactions of pellet culture closely mimic those that occur in precartilage condensation of the physis during development. The reduced COL10 message at day 28 in FA beads suggests that in longer term culture, FA MSCs are remaining in a more hyaline-like differentiated state, while 2.5×105 cell pellet and 5×105 pellet MSCs are progressing on to terminal differentiation and hypertrophy. Avoiding terminal differentiation would be desirable in cartilage repair applications and may support the value of fibrin glue or mixtures of fibrin and alginate for MSC grafting to cartilage defects.

Collagen type II immunohistochemistry confirmed the gene expression data, showing robust matrix type II formation in both small and large pellet systems, and FA cultures. MSCs in agarose culture also showed moderate type II formation in a discrete zone close to the base of agarose layers, while alginate culture had little or no collagen type II formation. In contrast, all culture systems resulted in MSCs that produced collagen type X. However, the significant difference between matrix collagen II and X, including the widespread formation of type X in almost all MSCs in agarose and pellet cultures, but a much lower expression around cells in alginate and FA systems, confirmed the gene expression data, and suggested that FA culture models may be more suitable for the study of mechanisms to induce articular chondrogenesis.

In addition to reduced cell to cell contact in FA cultures compared to pellets, that may have led to the reduced COL10 expression, FA may contain growth factors that enhance hyaline-like chondrogenesis. Fibrinogen derived by cryoprecipitation has platelet-derived growth factors such as TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3, PDGF, and VEGF,36 and the combination of recombinant TGF-β1 exposure from CM and TGF-β1 and -β3 exposure from the fibrin, may have influenced the progression toward a stable chondrocyte phenotype.

Pellet culture of equine MSCs had not been an ideal model in our laboratory, given the central necrosis and lamination that frequently developed, and it was surprising that the pellet culture system performed as well as it did, allowing adequate RNA isolation and the highest degree of MSC chondrogenesis. Many investigators, including ourselves, utilize a mixed pool of MSCs from several different donors for in vitro studies. This is done to increase the number of early passage MSCs available for the experiment, and to minimize the effect of interanimal heterogeneity of MSC cultures and subsequent variability in growth characteristics and response to experimental conditions. However, MSCs are exquisitely responsive to their microenvironment and cell to cell contacts,37 and mixing of MSCs from different donors may confound MSC studies. The experiment we report here was performed with five individual horses rather than a mixed population of donors and this may explain the success of both pellet culture systems in this experiment in contrast to our laboratory's previous experience with pellet culture. Subsequent use of the pellet culture system in our laboratory using individual horses has yielded similar success and when we have used a mixed population there has been reduced longevity and chondrogenesis of pellet cultures. Further investigation into the response of MSCs to the combination of donors versus individual donors is indicated.

One drawback of using pellet culture compared to biomaterial scaffolds such as alginate, fibrin, or agarose, is that a very large number of cells are required to generate sufficiently sized constructs. This is especially important when trying to avoid mixing cells from different donors within 3D constructs. It has recently been shown that the yield of MSCs from raw marrow is significantly greater in the first 5 mL collected, compared to subsequent aliquots in an equine sternal bone marrow collection.38 Therefore, to facilitate expansion of high numbers of early passage MSCs from individual donors, we maximized the MSC concentration from each bone marrow collection by aspirating only 15 mL per sternum site and collected a total of 180 mL of marrow per donor. By advancing the biopsy needle after each 15 mL of bone marrow had been drawn, we collected a larger proportion of MSCs to marrow and this allowed expansion of MSCs to at least 100×106 passage 2 cells.

Our results demonstrate the utility of FA, alginate, or pellet culture at both 2.5×105 cells per pellet and 5×105 cells per pellet, but not agarose, for long-term 3D culture of equine MSCs when gene expression is the study end point. Agarose failed to yield adequate RNA for qPCR. For the study of chondrogenic induction, both 2.5×105 pellet and 5×105 pellet systems appear to be superior, based upon COL2b gene expression and matrix accumulation within the pellets. Where minimal chondrocyte hypertrophic differentiation is also vital, FA may be a better choice than pellet culture.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the Harry M. Zweig Foundation at Cornell University and the Grayson Jockey Club Foundation. Dr. Watts was supported by NIH/NIAMS grant number F32AR057299-01 during the course of this study. We would like to thank Michael Scimeca for technical assistance. This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of Cornell University.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no competing financial or professional affiliations to disclose that may bias this work.

References

- 1.Jeffcott L.B. Rossdale P.D. Freestone J. Frank C.J. Towers-Clark P.F. An assessment of wastage in thoroughbred racing from conception to 4 years of age. Equine Vet J. 1982;14:185. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.1982.tb02389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mankin H.J. The response of articular cartilage to mechanical injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1982;64:460. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strauss E.J. Goodrich L.R. Chen C.T. Hidaka C. Nixon A.J. Biochemical and biomechanical properties of lesion and adjacent articular cartilage after chondral defect repair in an equine model. Am J Sports Med. 2005;33:1647. doi: 10.1177/0363546505275487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brittberg M. Lindahl A. Nilsson A. Ohlsson C. Isaksson O. Peterson L. Treatment of deep cartilage defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:889. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199410063311401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrickson D.A. Nixon A.J. Grande D.A. Todhunter R.J. Minor R.M. Erb H. Lust G. Chondrocyte-fibrin matrix transplants for resurfacing extensive articular cartilage defects. J Orthop Res. 1994;12:485. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100120405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sams A.E. Nixon A.J. Chondrocyte-laden collagen scaffolds for resurfacing extensive articular cartilage defects. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 1995;3:47. doi: 10.1016/s1063-4584(05)80037-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hunziker E.B. Biologic repair of articular cartilage. Defect models in experimental animals and matrix requirements. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;(367 Suppl):S135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hunter D.J. Pharmacologic therapy for osteoarthritis—the era of disease modification. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2011;7:13. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qvist P. Bay-Jensen A.C. Christiansen C. Dam E.B. Pastoureau P. Karsdal M.A. The disease modifying osteoarthritis drug (DMOAD): is it in the horizon? Pharmacol Res. 2008;58:1. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ortved K.F. Nixon A.J. Mohammed H.O. Fortier L.A. Treatment of subchondral cystic lesions of the medial femoral condyle of mature horses with growth factor enhanced chondrocyte grafts: a retrospective study of 49 cases. Equine Vet J. 2011;44:606. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2011.00510.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elves M.W. A study of the transplantation antigens on chondrocytes from articular cartilage. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1974;56:178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyc A. Malejczyk J. Osiecka A. Moskalewski S. Immunological response against allogeneic chondrocytes transplanted into joint surface defects in rats. Cell Transplant. 1997;6:119. doi: 10.1177/096368979700600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matricali G.A. Dereymaeker G.P. Luyten F.P. Donor site morbidity after articular cartilage repair procedures: a review. Acta Orthop Belg. 2010;76:669. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pittenger M.F. Mackay A.M. Beck S.C. Jaiswal R.K. Douglas R. Mosca J.D. Moorman M.A. Simonetti D.W. Craig S. Marshak D.R. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackay A.M. Beck S.C. Murphy J.M. Barry F.P. Chichester C.O. Pittenger M.F. Chondrogenic differentiation of cultured human mesenchymal stem cells from marrow. Tissue Eng. 1998;4:415. doi: 10.1089/ten.1998.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnstone B. Hering T.M. Caplan A.I. Goldberg V.M. Yoo J.U. In vitro chondrogenesis of bone marrow-derived mesenchymal progenitor cells. Exp Cell Res. 1998;238:265. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McIlwraith C.W. Frisbie D.D. Rodkey W.G. Kisiday J.D. Werpy N.M. Kawcak C.E. Steadman J.R. Evaluation of intra-articular mesenchymal stem cells to augment healing of microfractured chondral defects. Arthroscopy. 2011;27:1552. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2011.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fortier L.A. Potter H.G. Rickey E.J. Schnabel L.V. Foo L.F. Chong L.R. Stokol T. Cheetham J. Nixon A.J. Concentrated bone marrow aspirate improves full-thickness cartilage repair compared with microfracture in the equine model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92:1927. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.I.01284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wakitani S. Okabe T. Horibe S. Mitsuoka T. Saito M. Koyama T. Nawata M. Tensho K. Kato H. Uematsu K. Kuroda R. Kurosaka M. Yoshiya S. Hattori K. Ohgushi H. Safety of autologous bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cell transplantation for cartilage repair in 41 patients with 45 joints followed for up to 11 years and 5 months. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2011;5:146. doi: 10.1002/term.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kuroda R. Ishida K. Matsumoto T. Akisue T. Fujioka H. Mizuno K. Ohgushi H. Wakitani S. Kurosaka M. Treatment of a full-thickness articular cartilage defect in the femoral condyle of an athlete with autologous bone-marrow stromal cells. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2007;15:226. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsumoto T. Okabe T. Ikawa T. Iida T. Yasuda H. Nakamura H. Wakitani S. Articular cartilage repair with autologous bone marrow mesenchymal cells. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225:291. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilke M.M. Nydam D.V. Nixon A.J. Enhanced early chondrogenesis in articular defects following arthroscopic mesenchymal stem cell implantation in an equine model. J Orthop Res. 2007;25:913. doi: 10.1002/jor.20382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.De Bari C. Dell'Accio F. Luyten F.P. Failure of in vitro-differentiated mesenchymal stem cells from the synovial membrane to form ectopic stable cartilage in vivo. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:142. doi: 10.1002/art.11450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tuan R.S. Biology of developmental and regenerative skeletogenesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004;(427 Suppl):S105. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000143560.41767.ee. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rickey E.J. Nixon A.J. Mesenchymal stem cell aggregate cell number influences culture viability and chondrogenesis. Vet Surg. 2007;36:E21. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buschmann M.D. Gluzband Y.A. Grodzinsky A.J. Kimura J.H. Hunziker E.B. Chondrocytes in agarose culture synthesize a mechanically functional extracellular matrix. J Orthop Res. 1992;10:745. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Diduch D.R. Jordan L.C. Mierisch C.M. Balian G. Marrow stromal cells embedded in alginate for repair of osteochondral defects. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:571. doi: 10.1053/jars.2000.4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang I.H. Kim S.H. Kim Y.H. Sun H.J. Kim S.J. Lee J.W. Comparison of phenotypic characterization between “alginate bead” and “pellet” culture systems as chondrogenic differentiation models for human mesenchymal stem cells. Yonsei Med J. 2004;45:891. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2004.45.5.891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ho S.T. Cool S.M. Hui J.H. Hutmacher D.W. The influence of fibrin based hydrogels on the chondrogenic differentiation of human bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2010;31:38. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fortier L.A. Nixon A.J. Williams J. Cable C.S. Isolation and chondrocytic differentiation of equine bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Am J Vet Res. 1998;59:1182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dresdale A. Rose E.A. Jeevanandam V. Reemtsma K. Bowman F.O. Malm J.R. Preparation of fibrin glue from single-donor fresh-frozen plasma. Surgery. 1985;97:750. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lefebvre V. Smits P. Transcriptional control of chondrocyte fate and differentiation. Birth Defects Res C Embryo Today. 2005;75:200. doi: 10.1002/bdrc.20048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lefebvre V. Li P. de Crombrugghe B. A new long form of Sox5 (L-Sox5), Sox6 and Sox9 are coexpressed in chondrogenesis and cooperatively activate the type II collagen gene. EMBO J. 1998;17:5718. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Winter A. Breit S. Parsch D. Benz K. Steck E. Hauner H. Weber R.M. Ewerbeck V. Richter W. Cartilage-like gene expression in differentiated human stem cell spheroids: a comparison of bone marrow-derived and adipose tissue-derived stromal cells. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:418. doi: 10.1002/art.10767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ichinose S. Tagami M. Muneta T. Sekiya I. Morphological examination during in vitro cartilage formation by human mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;322:217. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1140-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rock G. Neurath D. Lu M. Alharbi A. Freedman M. The contribution of platelets in the production of cryoprecipitates for use in a fibrin glue. Vox Sang. 2006;91:252. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2006.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prockop D.J. Repair of tissues by adult stem/progenitor cells (MSCs): controversies, myths, and changing paradigms. Mol Ther. 2009;17:939. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kasashima Y. Ueno T. Tomita A. Goodship A.E. Smith R.K. Optimisation of bone marrow aspiration from the equine sternum for the safe recovery of mesenchymal stem cells. Equine Vet J. 2011;43:288. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-3306.2010.00215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]