Abstract

Periplasmic flagella are essential for the distinctive morphology, motility, and infectious life cycle of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. In this study, we genetically trapped intermediates in flagellar assembly and determined the 3D structures of the intermediates to 4-nm resolution by cryoelectron tomography. We provide structural evidence that secretion of rod substrates triggers remodeling of the central channel in the flagellar secretion apparatus from a closed to an open conformation. This open channel then serves as both a gateway and a template for flagellar rod assembly. The individual proteins assemble sequentially to form a modular rod. The hook cap initiates hook assembly on completion of the rod, and the filament cap facilitates filament assembly after formation of the mature hook. Cryoelectron tomography and mutational analysis thus combine synergistically to provide a unique structural blueprint of the assembly process of this intricate molecular machine in intact cells.

Keywords: protein secretion, molecular machines, macromolecular assemblages, bacterial motility

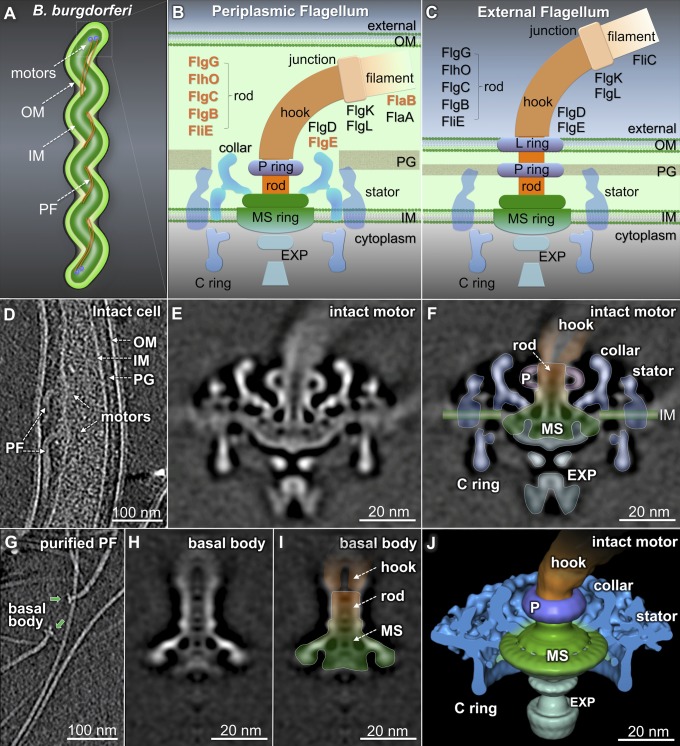

The Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi, is a highly motile and invasive bacterium (1). Seven to eleven periplasmic flagella (PFs) are inserted near both cell poles (Fig. 1A). The PFs are essential for the flat-wave morphology, distinct motility, and infectious life cycle of B. burgdorferi (2–6). They are different from external flagella (e.g., in Escherichia coli) in that both the hook and the filament are located in the periplasmic space. Nevertheless, the major components are remarkably similar among different bacterial species (Fig. 1 B and C and refs. 7–9).

Fig. 1.

Structural differences between the intact flagellar motor and the purified flagella. (A) Model of a B. burgdorferi cell: outer membrane (OM), inner membrane (IM), and periplasmic flagella (PFs). (B and C) Models of a PF and an external flagellum. (D) A section from a wild-type cell tomogram. A central section (E) and an outline overlapping onto the map (F) of the intact motor. The MS ring is colored green, the rod and hook are colored orange, and the P ring (P), the export apparatus (EXP), the stator, and the collar are labeled accordingly. (G) A section from a purified PFs tomogram. A section (H) and an outline (I) of the basal body. The MS ring–rod complex remains in both the basal body (I) and the intact motor (F). (J) A 3D surface rendering of the intact motor (F).

The flagellum is a sophisticated self-assembling molecular machine (10, 11). It contains at least 25 different proteins that form a rotary motor, a hook, and a helical filament (Fig. 1 B and C) (11–13). The morphogenetic pathway for flagellar biosynthesis has been extensively studied in E. coli and Salmonella typhimurium, in which the expression of motility genes is coordinated with flagellar assembly (10, 11). Assembly is initiated by the insertion of the MS ring (consisting of FliF) into the cytoplasmic membrane. The MS ring then acts as a platform for assembly of the C ring (the switch complex), the stator (the torque generator), and the flagellum-specific type III secretion (T3S) apparatus. Most flagellar proteins are secreted by the T3S system, which is powered by the transmembrane ion-motive force (14, 15). The secretion and assembly of each substrate is highly ordered; flagellar assembly proceeds in a linear fashion from proximal rod to distal filament (10, 11). However, this progressive assembly process has not been visualized in detail.

The flagellar rod is the first structure secreted by the T3S system, and it functions both as a hollow secretion channel and a drive shaft that transmits torque. The structure of the intact rod of S. typhimurium was deduced by comparing electron microscopy images of purified flagellar basal bodies with MS ring complexes (16, 17). Five proteins (FliE, FlgB, FlgC, FlgF, and FlgG) are involved in assembly of the flagellar rod. FliE is postulated to be a structural adaptor between the MS ring and the rod (18, 19). Moreover, assembly of FliE is required for exporting other substrates (20). It is generally thought that the rod proteins assemble cooperatively to build a stable rod (21, 22). However, no direct structural evidence has been reported, because rod mutations in S. typhimurium result in structural instability (22). Visualization of the nascent rod assembly, either in vivo or in vitro, has been a formidable technical challenge.

On completion of the rod, a cap protein is required for hook assembly. The hook-cap protein, FlgD, has been detected at the distal end of the hook (23). Hooks are thought to assemble at their distal ends by inserting FlgE subunits underneath the hook cap. After the hook reaches its mature length (∼55 nm), two junction proteins, FlgK and FlgL, and a filament cap protein, FliD, are added sequentially to the distal end of the hook (24). The filament cap is predicted to stay at the end of the growing filament to facilitate polymerization of filament proteins (25). Understanding the intermediates in this complex process will shed light on the polymerization activity that yields a functional assembly.

Given the high degree of conservation among flagellar proteins, T3S-mediated flagellar assembly in B. burgdorferi likely resembles that of other bacterial species. The multiple flagellar motors of B. burgdorferi are located close to both of its narrow (diameter ≤0.3 µm) cell poles. This location is optimal for cryoelectron tomography (cryo-ET) determination of the molecular architecture of the flagellar motor in intact cells (7–9, 26, 27). In this study, we selectively deleted individual genes whose products play key roles in flagellar assembly and then used cryo-ET and subvolume averaging to determine intermediate structures. This approach permitted a molecular characterization of the nascent structures of flagellar intermediates, thereby providing detailed insights into the sequential processes of T3S-mediated flagellar assembly.

Results

Structural Differences Between the Intact Flagellar Motor in Situ and Purified Flagella.

In B. burgdorferi, multiple flagellar motors are embedded in the inner membrane (Fig. 1 A and D; Movie S1). A 3.5-nm-resolution structure of the intact flagellar motor (Fig. 1E) clearly shows the straight rod with a channel in the middle. The rod also adopts a tilted conformation (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), suggesting it is either intrinsically flexible or has at least two fixed orientations. The MS ring is associated with the export apparatus, the rod, the C ring, and the collar (Fig. 1 B and E). To define the MS ring from the intact motor of B. burgdorferi, we purified PFs (Fig. 1G) and determined the 3D structure of the basal body (Fig. 1 H and I). The purified basal body was significantly smaller than the intact motor (Fig. 1 E and F). Many membrane-associated and periplasmic structures of the intact motor were removed during PF purification. The remaining basal body is structurally comparable to the MS ring and rod of the S. typhimurium basal body (16) (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). On this basis, we propose a model of the MS ring–rod complex in B. burgdorferi (Fig. 1 F and J).

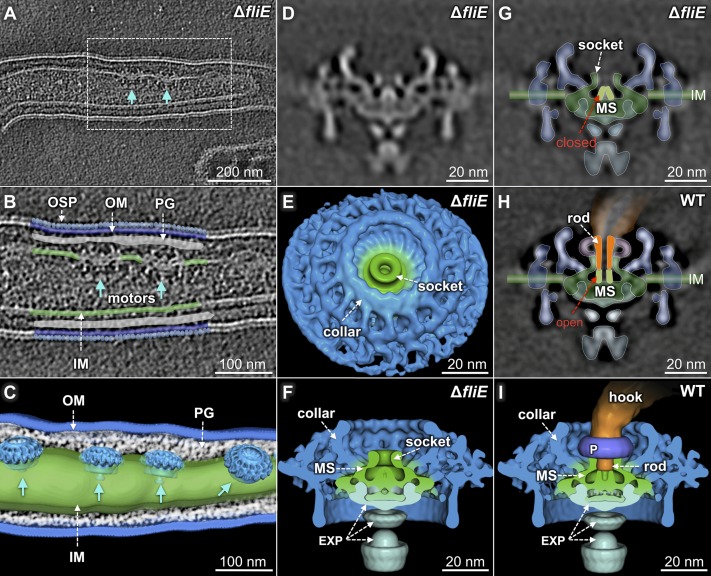

Flagellar Motor Structure in a ΔfliE Mutant.

To define the boundary between the rod and the MS ring, we constructed a fliE deletion mutant (ΔfliE), using a recently reported gene-inactivation system that does not impose a polar effect on downstream gene expression (28). The ΔfliE cells are rod-shaped and nonmotile (SI Appendix, Table S1), and there is no hook or filament in the periplasmic space (Fig. 2A; Movie S2). However, multiple flagellar motors are clearly visible at the cell poles (Fig. 2 B and C). The motor structure from the ΔfliE mutant (Fig. 2 D–F) is significantly different from that of the wild-type motor, as the mutant lacks the rod, the hook, and the filament. Other components of the motor (the MS ring, the C ring, the stator, the export apparatus, and the collar) remain unaffected, suggesting those motor components assemble independent of the T3S-mediated pathway.

Fig. 2.

The flagellar motor structure of the ΔfliE mutant reveals a closed conformation of the central channel. (A) Multiple flagellar motors are embedded in the inner membrane. Enlarged image (B) and 3D surface rendering (C) of the region outlined in A. A central section (D) and 3D surface rendering in top (E) and side (F) views of the ΔfliE motor. (G) A central channel domain (light green) is closed in the ΔfliE mutant. (H) Outline of the rod (orange) and the MS ring (green), and a 3D surface rendering (I) of the wild-type motor. The channel domain of the MS ring is in an open conformation, and the rod is assembled on top of the channel domain.

In the absence of the rod, a socket-like domain of the MS ring is clearly visible (Fig. 2 E and G, white arrows). It forms a well-defined pocket for anchoring the rod. Notably, the central channel of the MS ring is closed in the ΔfliE motor (Fig. 2 D and G), whereas it is open in the wild-type motor (Figs. 1E and 2H). The outer diameter of the channel is 6 nm (Fig. 2H). Apparently, the rod assembles on top of the open channel and forms an integrated complex with the MS ring (Figs. 1E and 2H).

Flagellar Motor Structures in the Rod Mutants ΔflgB, ΔflgC, and ΔflhO.

To investigate assembly of the rod in detail, we introduced nonpolar mutations into each of the rod genes [flgB, flgC, flhO (a flgF homolog), and flgG; SI Appendix, Table S1]. We also generated a double-knockout mutant ΔflgBC (SI Appendix, Table S1). All of the mutant cells were rod-shaped and nonmotile, and no flagellar filament or hook was assembled in the periplasmic space of any of these rod mutants. As in the ΔfliE mutant, multiple motors were readily visible at the cell poles (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

The central channel of the ΔflgB flagellar motor remains in a closed conformation (Fig. 3 A, D, and G). In contrast, the channel is in an open conformation in the ΔflgC mutant (Fig. 3 B, E, and H). An additional globular density is also evident in the ΔflgC mutant, suggesting FlgB is secreted and accumulates in that region. The globular density is more pronounced and extends beyond the MS-ring socket in the ΔflhO mutant (Fig. 3 C, F, and I), suggesting FlgC also locates to the globular density. Together, secretion of FlgB and FliE appears to trigger opening of the channel, which then permits the secretion of other substrates.

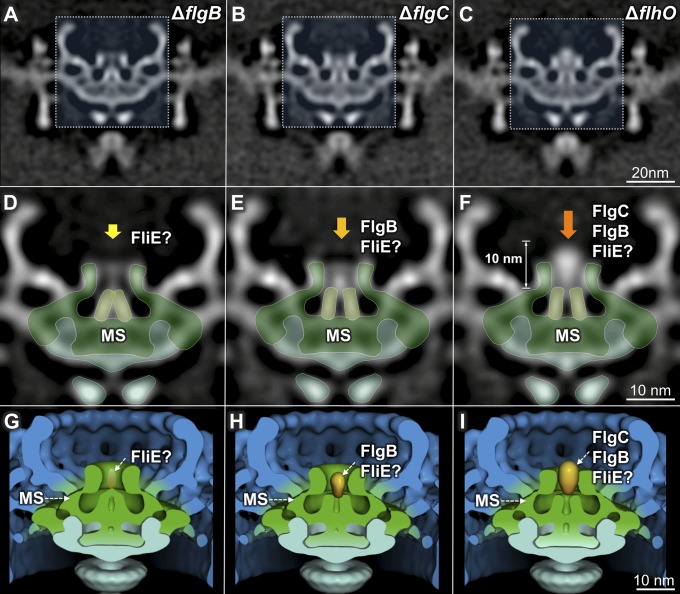

Fig. 3.

Intermediate structures of the flagellar rod. (A–C) Three-dimensional maps of the ΔflgB, ΔflgC, and ΔflhO flagellar motors. (D–F) Enlarged images of the regions outlined in (A–C). In the ΔflgB mutant, the channel in the MS ring remains closed (D). In the ΔflgC mutant, the channel is in an open conformation, and a globular density is visible (E). In the ΔflhO mutant, the globular density is larger and extends beyond the MS ring (F). (G–I) Three-dimensional surface rendering of the motors from the ΔflgB, ΔflgC, and ΔflhO mutants.

Proximal Rod and Distal Rod Structures in the ΔflgG and ΔflgE Mutants.

The flagellar motor structure in the ΔflgG mutant (Fig. 4 A and B) differs from those of the mutants described earlier (Figs. 2 and 3) in that a 13-nm-long tube-shaped structure extends from the apex of the central channel of the MS ring. It is significantly longer than the globular densities observed in the ΔflgC and ΔflhO mutants (Fig. 3 B and C) and constitutes the proximal rod. The 3D structure of the proximal rod (Fig. 4C) was derived from the difference map between the ΔflgG motor and the ΔfliE motor. Evidently the rod undergoes a transformative change from a globular density in the ΔflhO mutant into a tube-like structure in the ΔflgG mutant, suggesting FlhO is essential for the ordered assembly of a conformationally and functionally intact proximal rod (Fig. 4A).

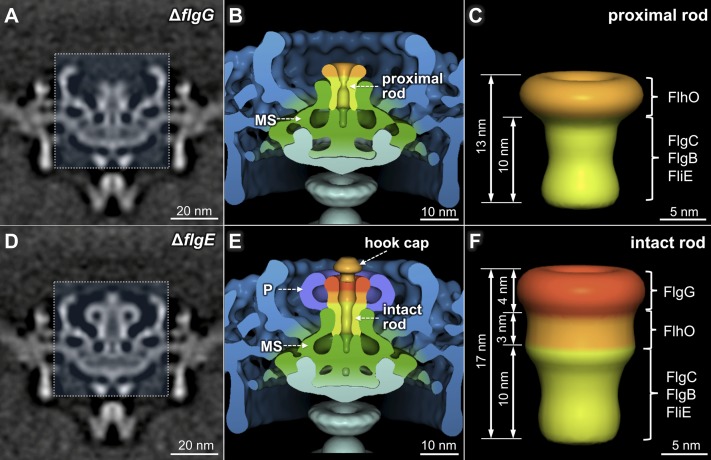

Fig. 4.

Three-dimensional structures of the proximal rod and fully assembled rod. A central section (A) and 3D surface rendering (B) of the ΔflgG motor. A flanged tube structure is readily observed above the channel domain of the MS ring. (C) Three-dimensional surface rendering of the proximal rod. A central section (D) and 3D surface rendering (E) of the ΔflgE motor. The fully assembled rod, the P ring, and a cap structure (probably the hook cap) are revealed in E. (F) Three-dimensional surface rendering of the intact rod.

To reveal the structure of the distal rod, we determined the motor structure from a mutant deleted for the flgE gene, which encodes the major hook subunit (Fig. 4 D and E). Comparative analysis of the intact motor (Fig. 1E) and the ΔflgG and ΔflgE motors (Fig. 4) reveals that the intact rod is ∼17 nm long, meaning the distal rod is ∼4 nm in length (Fig. 4F). The torus-shaped P ring (9) is present in the ΔflgE mutant (Fig. 4D), but not in the ΔflgG mutant (Fig. 4A), demonstrating that the distal rod is a necessary substrate for the assembly of the P ring. The intact rod is thus bound by the MS ring at the bottom and by the P ring on the lateral surface at the top (Fig. 4E). The diameter and density of the intact rod vary along its length. Therefore, the rod is not a simple cylindrical structure with a uniform diameter. Instead, it is composed of modular cylinders, each with well-defined but distinct diameters ranging from 8 to 14 nm (Fig. 4F).

A plug-like structure is inserted into the distal rod in the ΔflgE motor (Fig. 4 D and E). There is no similar structure in either the intact motor (Fig. 1E) or the ΔflgG motor (Fig. 4A). In the absence of the hook subunit FlgE, the assembly process presumably terminates right before the initiation of hook assembly. Therefore, we propose that the plug-like structure represents the hook cap, a structure that is predicted to be required for hook assembly (23).

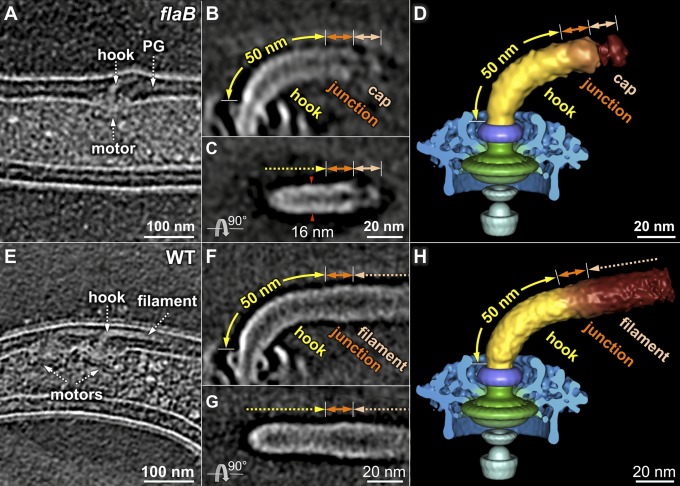

Flagellar Hook and Hook–Filament Junction Structures Revealed in a flaB Mutant.

The flagellar filament of B. burgdorferi contains a major filament protein, FlaB, and a minor filament protein, FlaA (29, 30). The B. burgdorferi flaB mutant cells are nonmotile and rod-shaped, and they are completely deficient in filament assembly (2, 6). Both flagellar motors and hooks are visible near the cell poles in the flaB mutant (Fig. 5A). A ∼62-nm tube-like structure and a ∼14-nm cap-like structure are evident in the flaB mutant (Fig. 5 B and C), which probably represent an assembly intermediate that contains a mature hook and hook-filament junction associated with the filament cap, respectively.

Fig. 5.

Three-dimensional structures of the hook and the hook–filament junction. (A) Cryo-tomogram of a flaB mutant cell. The flagellar hook complex in two different orientations (B and C). The hook length is estimated to be ∼50 nm, and another ∼12 nm density is probably the hook–filament junction, as labeled in B and C. (D) Three-dimensional surface rendering of the flaB mutant flagellar structure. The hook (together with the hook–filament junction) and the filament cap are segmented. (E) Cryo-tomogram of a wild-type cell showing the flagellar motor with a hook and filament. (F and G) Three-dimensional structures of the flagellar hook and filament in wild-type cells. The diameter of the axial structure gradually becomes larger at the junction region. (H) Three-dimensional surface rendering of an intact flagellum.

The mature hook is ∼50 nm long (Fig. 5B), which is similar to that of the hook in S. typhimurium (∼55 nm; 31). At the distal end of the hook, an additional ∼12-nm-long structure differs slightly from the hook in density and diameter (Fig. 5 B and C); we postulate that this region represents the hook–filament junction. Furthermore, a cap-like structure is connected to the distal end of the hook–filament junction (Fig. 5 C and D). The observed density of the cap is structurally similar to the filament cap of S. typhimurium (25). The filament cap is absent at the hook–filament junction in wild-type cells (Fig. 5 E–H), supporting the idea that the filament cap remains at the distal end of the growing filament (24, 25).

Discussion

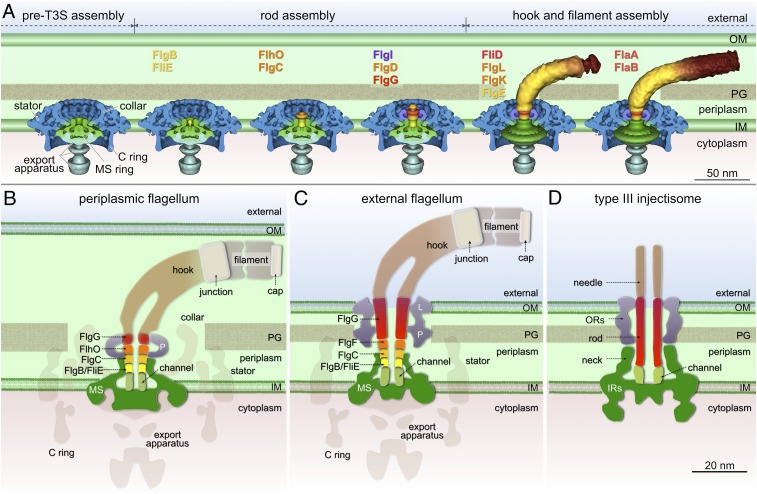

The PF plays critical roles in the distinct morphology, motility, and infectivity of the Lyme disease spirochete B. burgdorferi and other spirochetes (such as Treponema pallidum, the causative agent of syphilis) (26). Because B. burgdorferi is genetically tractable, it has proven to be an excellent model for visualizing the sequential assembly of flagella in intact spirochetes (Fig. 6A and Movie S3). In addition, the PFs of spirochetes have enough in common with external flagella to serve as a global model for flagellar assembly.

Fig. 6.

Modular architecture and assembly blueprint of bacterial flagella. (A) A model of flagellar assembly in B. burgdorferi. In the pre-T3S assembly state, many flagellar components assemble, including the MS ring, the C ring, the stators, the export apparatus, and the collar. The secretion channel in the MS ring is closed (first panel). In the presence of FliE and FlgB, rod substrates can be secreted but are unable to form a stable structure (second panel) until all of the proximal rod substrates (FliE, FlgB, FlgC, and FlhO) are present (third panel). The distal rod protein FlgG adds onto the proximal rod and polymerizes until it reaches a determined length (fourth panel). A hook cap composed of FlgD forms at the distal end of the rod (fourth panel) and promotes hook assembly (fifth panel). Assembly of the filament (FlaA and FlaB) is promoted by the filament cap (FliD) (sixth panel). (B) A cartoon model of a PF. Five rod proteins assemble sequentially on top of the channel domain of the MS ring and are enclosed by the socket domain of the MS ring and the P ring. The FlgG distal rod in the PF is shorter than that in the external flagellum (C). (D) A cartoon model of type III injectisome shows that the rod is anchored on a structure similar to the channel domain of the flagellar motor. The rod is a straight tube formed by one protein, PrgJ.

MS Ring Assembly.

The MS ring is the first stage in the assembly of the C ring, the export apparatus, the collar, and the stator. Those components all assemble independent of the T3S-mediated export pathway (Fig. 6A). A socket and a central channel in the MS ring are well defined in the absence of any rod components (Fig. 2). The socket appears similar in all of the B. burgdorferi flagellar motor structures examined, suggesting it provides a compact and stable platform for rod assembly. A unique segment of FliF (residues 280–360 in E. coli) has been proposed to form the socket domain, and mutations targeting this region cause release of the filament and the rod from the basal body (17, 32, 33).

Before rod assembly, the channel of the MS ring is closed, providing an explanation for the observation that substrate secretion is very low in the absence of FliE (20). When the rod substrates FliE and FlgB are secreted, the central channel adopts an open conformation that also serves as a template for the initiation of the rod assembly (34). The open channel of the MS ring and the rod forms a tightly integrated structure with no distinguishable boundary (Fig. 1E). The presence of heptad repeats of hydrophobic residues in the terminal regions of the rod proteins (SI Appendix, Table S3) may mean that an α-helical coiled-coil is the motif required to form a continuous mechanically stable axial structure (35, 36). The sequence of residues 130–230 of FliF is highly conserved and contains hydrophobic residues at several heptad positions (SI Appendix, Table S4). Therefore, the rod proteins apparently assemble on top of the open channel, probably through hydrophobic α-helical coiled-coil interactions.

Rod Assembly.

The flagellar rod is a multicomponent complex that functions as an export channel and drive shaft. It has been suggested that rod proteins assemble cooperatively to form an intact rod but that rod intermediates are unstable (22). Here we were able to determine structures corresponding to intermediate stages of rod assembly. The rod elongates sequentially in ΔflgB, ΔflgC, ΔflhO, ΔflgG, and ΔflgE mutants, implying the rod assembles in the order FliE-FlgB-FlgC-FlhO-FlgG. In the presence of FlgB, FlgC, and FlgO, the proximal rod forms a tube-like structure (Fig. 4A), whereas the intermediate structures visible in the ΔflgB, ΔflgC, and ΔflhO mutants do not show any tube-like character (Fig. 3). Therefore, we conclude that the proper assembly of the proximal rod requires cooperative interactions between the FlgB, FlgC, and FlhO. FlgG can then form a distal rod and serve as the substrate for subsequent addition of the P ring and hook.

Hook and Filament Assembly.

Hook assembly (23) and filament assembly (24, 25) are mediated by the hook-cap protein (FlgD) and the filament-cap protein (FliD), respectively. Assembly is blocked right before hook formation in the ΔflgE mutant and before filament formation in the flaB mutant. As a consequence, we were able to capture intermediates containing the hook cap (Fig. 4D) and the filament cap (Fig. 5B), respectively. Both the structures can be divided into cap and leg domains (Figs. 4D and 5B); a similar cap–leg architecture was seen in a high-resolution structure of the filament cap (25). We therefore suggest that the hook cap facilitates assembly of the hook by a rotational mechanism similar to the one used by the filament cap to promote assembly of the filament (25).

Modular Architecture of the Flagellar Rod.

The flagellar rod is formed by five proteins that interact through α-helical coiled-coils that join the N terminus of one subunit to the C terminus of the adjacent subunit (35–38). The rod assembles on top of the open channel in the MS ring, likely through similar hydrophobic interactions. The rod is further reinforced by strong interactions with the socket of the MS ring and with the P ring (Fig. 6B). This organization of rod components differs from that of external flagella (Fig. 6C). The distal rod of external flagella is estimated to consist of four turns containing 26 FlgG subunits (∼15 nm in S. typhimurium) (11, 39). In contrast, the distal rod (∼4 nm) of the B. burgdorferi flagellar motor is too short to penetrate the outer membrane (Fig. 6B). We conjecture that FlgG and the three other rod proteins (FlgB, FlgC, FlhO) in B. burgdorferi each polymerize for only a single turn. The underlying mechanism for control of the length of the distal rod must therefore be different during the formation of external flagella and PFs.

The flagellum and the virulence-associated injectisome share an analogous architecture and homologous T3S components (40). However, the structure and function of the rod are quite different in the two systems. The rod of the injectisome is formed by a protein (PrgJ in S. typhimurium). Rod assembly is required for proper anchoring of the needle structure (41). The function of the injectisome rod is to provide a conduit for protein transport from the bacterial cytoplasm to the host cell (Fig. 6D). In contrast, the flagellar rod and its complex interactions with the MS ring, P ring, and hook (Fig. 6B) provide dual functions: a hollow channel for protein secretion and a sturdy drive shaft to transmit torque between the motor and filament.

In summary, high-throughput cryo-ET, coupled with mutational analysis, revealed a complete series of high-resolution molecular snapshots of the periplasmic flagella assembly process in the Lyme disease spirochete. The resulting composite picture provides a structural blueprint depicting the assembly process of this intricate molecular machine. This approach should be applicable in determining the sequence of events in intact cells that generate a broad range of molecular machines.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains.

High-passage avirulent B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain B31A (wild-type) and its isogenic mutants (SI Appendix, Table S1) were grown in Barbour–Stoenner–Kelly (BSK-II) liquid medium supplemented with 6% (vol/vol) rabbit serum or on semisolid agar plates at 34 °C in the presence of 3–5% carbon dioxide, as previously described (42). The flgB (bb0294), flgC (bb0293), fliE (bb0292), and flgE (bb0283) genes are located in the flgB operon (SI Appendix, Fig. S4), consisting of ∼26 motility genes (43); flhO (bb0775, a homolog of FlgF) and flgG (bb0774) are located within the flhO motility gene operon (42). To avoid potential polar effect on a downstream gene expression, our recently reported gene replacement in-frame deletion method (28) was used to construct the targeted mutagenesis in the flgB, flgC, flgBC (deleting both flgB and flgC), fliE, flgE, and flhO genes. See SI Appendix, Materials and Methods) for details.

Cryo-Electron Tomography.

Frozen-hydrated specimens were prepared as described previously (9). Briefly, the B. burgdorferi culture was centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 5 min, and the resulting pellets were rinsed gently with 1 mL PBS. The cells were centrifuged again and were finally suspended in 30∼50 μL PBS. The cultures were mixed with 10-nm (or 15-nm) colloidal fiducial gold markers and then deposited onto freshly glow-discharged, holey carbon grids for 1 min. Grids were blotted with filter paper and then rapidly frozen in liquid ethane, using a homemade gravity-driven plunger apparatus.

Frozen-hydrated specimens were imaged at −170 °C, using a Polara G2 electron microscope (FEI) equipped with a field emission gun and a 16-megapixel CCD camera (TVIPS). The microscope was operated at 300 kV with a magnification of 31,000×, resulting in an effective pixel size of 5.7 Å after 2 × 2 binning. Using the FEI batch tomography program, low-dose, single-axis tilt series were collected from cell poles at −6 to −9 µm defocus, with a cumulative dose of ∼100 e−/Å2 distributed over 87 images and covering an angular range of −64° to +64°, with an angular increment of 1.5°. Tilt series were automatically aligned and reconstructed using a combination of IMOD (44) and RAPTOR (45). In total, 234,552 CCD images and 2,696 tomographic reconstructions were generated and used for further processing (SI Appendix, Table S2).

Subvolume Analysis.

Conventional imaging analysis, including 4 × 4 × 4 binning, contrast inversion, and low-pass filtering, enhanced the contrast of binned tomograms (46). The subvolumes (256 × 256 × 256 voxels) of the flagellar motors were extracted computationally from the tomograms and were further aligned as previously described (9, 26, 47, 48). A total of 15,380 flagellar motor subvolumes were manually selected from 2,696 reconstructions (SI Appendix, Table S2). Class averages were computed in Fourier space, so the missing wedge problem of tomography was minimized (46, 48). Fourier shell correlation coefficients with a threshold of 0.5 were estimated by comparing the correlation between two randomly divided halves of the aligned images used to generate the final maps (SI Appendix, Table S2).

Three-Dimensional Visualization.

Segmentation of 3D flagellar structure is based on the density maps and the difference maps (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). The software package UCSF Chimera (49) was mainly used for 3D visualization and surface rendering. Segmentations of cryo tomographic reconstructions from a wild-type cell and a ΔfliE cell were constructed using the 3D modeling software Amira (Visage Imaging). The filaments, the outer and inner membranes, and the peptidoglycan layer were manually segmented (Movies S1 and S2). The isosurface maps from the flagellar motor were computationally mapped back into the original cellular context.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ken Taylor and Dr. Jeff Actor for comments. This work was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Grant R01AI087946 (to J.L., S.J.N., and M.A.M.), Welch Foundation Grant AU-1714 (to J.L.), NIAID Grant R01AI078958 (to K.Z. and C.L.), NIAID Grant R21AI093917 and the American Heart Association (K.A.M., M.E.J., and N.W.C.), and National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) Grant R01AR060834 (to T.B. and M.A.M.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The electron microscopy maps have been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank, www.ebi.ac.uk/pdbe/emdb (accession nos. EMD-5627–EMD-5633).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1308306110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Charon NW, et al. The unique paradigm of spirochete motility and chemotaxis. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2012;66:349–370. doi: 10.1146/annurev-micro-092611-150145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motaleb MA, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi periplasmic flagella have both skeletal and motility functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(20):10899–10904. doi: 10.1073/pnas.200221797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sal MS, et al. Borrelia burgdorferi uniquely regulates its motility genes and has an intricate flagellar hook-basal body structure. J Bacteriol. 2008;190(6):1912–1921. doi: 10.1128/JB.01421-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sze CW, et al. Carbon storage regulator A (CsrA(Bb)) is a repressor of Borrelia burgdorferi flagellin protein FlaB. Mol Microbiol. 2011;82(4):851–864. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07853.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li C, Xu H, Zhang K, Liang FT. Inactivation of a putative flagellar motor switch protein FliG1 prevents Borrelia burgdorferi from swimming in highly viscous media and blocks its infectivity. Mol Microbiol. 2010;75(6):1563–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07078.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sultan SZ, et al. Motility is crucial for the infectious life cycle of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2013;81(6):2012–2021. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01228-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen S, et al. Structural diversity of bacterial flagellar motors. EMBO J. 2011;30(14):2972–2981. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kudryashev M, Cyrklaff M, Wallich R, Baumeister W, Frischknecht F. Distinct in situ structures of the Borrelia flagellar motor. J Struct Biol. 2010;169(1):54–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu J, et al. Intact flagellar motor of Borrelia burgdorferi revealed by cryo-electron tomography: evidence for stator ring curvature and rotor/C-ring assembly flexion. J Bacteriol. 2009;191(16):5026–5036. doi: 10.1128/JB.00340-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chevance FF, Hughes KT. Coordinating assembly of a bacterial macromolecular machine. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2008;6(6):455–465. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Macnab RM. How bacteria assemble flagella. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2003;57:77–100. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.57.030502.090832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berg HC. The rotary motor of bacterial flagella. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72:19–54. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terashima H, Kojima S, Homma M. Flagellar motility in bacteria structure and function of flagellar motor. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2008;270:39–85. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(08)01402-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minamino T, Namba K. Distinct roles of the FliI ATPase and proton motive force in bacterial flagellar protein export. Nature. 2008;451(7177):485–488. doi: 10.1038/nature06449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul K, Erhardt M, Hirano T, Blair DF, Hughes KT. Energy source of flagellar type III secretion. Nature. 2008;451(7177):489–492. doi: 10.1038/nature06497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Francis NR, Sosinsky GE, Thomas D, DeRosier DJ. Isolation, characterization and structure of bacterial flagellar motors containing the switch complex. J Mol Biol. 1994;235(4):1261–1270. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Suzuki H, Yonekura K, Namba K. Structure of the rotor of the bacterial flagellar motor revealed by electron cryomicroscopy and single-particle image analysis. J Mol Biol. 2004;337(1):105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Minamino T, Yamaguchi S, Macnab RM. Interaction between FliE and FlgB, a proximal rod component of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella. J Bacteriol. 2000;182(11):3029–3036. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3029-3036.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Müller V, Jones CJ, Kawagishi I, Aizawa S, Macnab RM. Characterization of the fliE genes of Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium and identification of the FliE protein as a component of the flagellar hook-basal body complex. J Bacteriol. 1992;174(7):2298–2304. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.7.2298-2304.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minamino T, Macnab RM. Components of the Salmonella flagellar export apparatus and classification of export substrates. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(5):1388–1394. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.5.1388-1394.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones CJ, Macnab RM. Flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium: analysis with temperature-sensitive mutants. J Bacteriol. 1990;172(3):1327–1339. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.3.1327-1339.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kubori T, Shimamoto N, Yamaguchi S, Namba K, Aizawa S. Morphological pathway of flagellar assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol. 1992;226(2):433–446. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)90958-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ohnishi K, Ohto Y, Aizawa S, Macnab RM, Iino T. FlgD is a scaffolding protein needed for flagellar hook assembly in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1994;176(8):2272–2281. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.8.2272-2281.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Homma M, Iino T. Locations of hook-associated proteins in flagellar structures of Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1985;162(1):183–189. doi: 10.1128/jb.162.1.183-189.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yonekura K, et al. The bacterial flagellar cap as the rotary promoter of flagellin self-assembly. Science. 2000;290(5499):2148–2152. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5499.2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liu J, et al. Cellular architecture of Treponema pallidum: novel flagellum, periplasmic cone, and cell envelope as revealed by cryo electron tomography. J Mol Biol. 2010;403(4):546–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.09.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Murphy GE, Leadbetter JR, Jensen GJ. In situ structure of the complete Treponema primitia flagellar motor. Nature. 2006;442(7106):1062–1064. doi: 10.1038/nature05015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Motaleb MA, Pitzer JE, Sultan SZ, Liu J. A novel gene inactivation system reveals altered periplasmic flagellar orientation in a Borrelia burgdorferi fliL mutant. J Bacteriol. 2011;193(13):3324–3331. doi: 10.1128/JB.00202-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ge Y, Li C, Corum L, Slaughter CA, Charon NW. Structure and expression of the FlaA periplasmic flagellar protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 1998;180(9):2418–2425. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.9.2418-2425.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Motaleb MA, Sal MS, Charon NW. The decrease in FlaA observed in a flaB mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi occurs posttranscriptionally. J Bacteriol. 2004;186(12):3703–3711. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.12.3703-3711.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirano T, Yamaguchi S, Oosawa K, Aizawa S. Roles of FliK and FlhB in determination of flagellar hook length in Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1994;176(17):5439–5449. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.17.5439-5449.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ueno T, Oosawa K, Aizawa S. Domain structures of the MS ring component protein (FliF) of the flagellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol. 1994;236(2):546–555. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1994.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okino H, et al. Release of flagellar filament-hook-rod complex by a Salmonella typhimurium mutant defective in the M ring of the basal body. J Bacteriol. 1989;171(4):2075–2082. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.4.2075-2082.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Saijo-Hamano Y, Uchida N, Namba K, Oosawa K. In vitro characterization of FlgB, FlgC, FlgF, FlgG, and FliE, flagellar basal body proteins of Salmonella. J Mol Biol. 2004;339(2):423–435. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.03.070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yonekura K, Maki-Yonekura S, Namba K. Complete atomic model of the bacterial flagellar filament by electron cryomicroscopy. Nature. 2003;424(6949):643–650. doi: 10.1038/nature01830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Homma M, DeRosier DJ, Macnab RM. Flagellar hook and hook-associated proteins of Salmonella typhimurium and their relationship to other axial components of the flagellum. J Mol Biol. 1990;213(4):819–832. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80266-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Homma M, Kutsukake K, Hasebe M, Iino T, Macnab RM. FlgB, FlgC, FlgF and FlgG. A family of structurally related proteins in the flagellar basal body of Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol. 1990;211(2):465–477. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90365-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samatey FA, et al. Structure of the bacterial flagellar hook and implication for the molecular universal joint mechanism. Nature. 2004;431(7012):1062–1068. doi: 10.1038/nature02997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jones CJ, Macnab RM, Okino H, Aizawa S. Stoichiometric analysis of the flagellar hook-(basal-body) complex of Salmonella typhimurium. J Mol Biol. 1990;212(2):377–387. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90132-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Erhardt M, Namba K, Hughes KT. Bacterial nanomachines: the flagellum and type III injectisome. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(11):a000299. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Marlovits TC, et al. Assembly of the inner rod determines needle length in the type III secretion injectisome. Nature. 2006;441(7093):637–640. doi: 10.1038/nature04822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang K, Tong BA, Liu J, Li C. A single-domain FlgJ contributes to flagellar hook and filament formation in the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. J Bacteriol. 2012;194(4):866–874. doi: 10.1128/JB.06341-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ge Y, Charon NW. Identification of a large motility operon in Borrelia burgdorferi by semi-random PCR chromosome walking. Gene. 1997;189(2):195–201. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00848-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kremer JR, Mastronarde DN, McIntosh JR. Computer visualization of three-dimensional image data using IMOD. J Struct Biol. 1996;116(1):71–76. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1996.0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amat F, et al. Markov random field based automatic image alignment for electron tomography. J Struct Biol. 2008;161(3):260–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2007.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liu J, Wright ER, Winkler H. 3D visualization of HIV virions by cryoelectron tomography. Methods Enzymol. 2010;483:267–290. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)83014-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winkler H. 3D reconstruction and processing of volumetric data in cryo-electron tomography. J Struct Biol. 2007;157(1):126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Winkler H, et al. Tomographic subvolume alignment and subvolume classification applied to myosin V and SIV envelope spikes. J Struct Biol. 2009;165(2):64–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.