Abstract

Atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) isoforms ζ and λ interact with polarity complex protein Par3 and are evolutionarily conserved regulators of cell polarity. Prkcz encodes aPKC-ζ and PKM-ζ, a truncated, neuron-specific alternative transcript, and Prkcl encodes aPKC-λ. Here we show that, in embryonic hippocampal neurons, two aPKC isoforms, aPKC-λ and PKM-ζ, are expressed. The localization of these isoforms is spatially distinct in a polarized neuron. aPKC-λ, as well as Par3, localizes at the presumptive axon, whereas PKM-ζ and Par3 are distributed at non-axon-forming neurites. PKM-ζ competes with aPKC-λ for binding to Par3 and disrupts the aPKC-λ–Par3 complex. Silencing of PKM-ζ or overexpression of aPKC-λ in hippocampal neurons alters neuronal polarity, resulting in neurons with supernumerary axons. In contrast, the overexpression of PKM-ζ prevents axon specification. Our studies suggest a molecular model wherein mutually antagonistic intermolecular competition between aPKC isoforms directs the establishment of neuronal polarity.

Keywords: axonogenesis, symmetry breaking, neurodevelopment

A ternary complex of Par6, Par3, and a protein kinase, atypical protein kinase C (aPKC), forms an essential molecular determinant of cell polarity (1–3). There are two aPKC genes in the vertebrate genome, Prkcl and Prkcz, which code for three distinct proteins. Prkcl encodes aPKC-λ, and Prkcz codes for aPKC-ζ and the alternatively transcribed PKM-ζ. aPKC-ζ contains an N-terminal regulatory region comprising a protein–protein interaction motif and a pseudosubstrate sequence and a C-terminal kinase domain (4). PKM-ζ is a truncated kinase that lacks the N terminus entirely (5). In the invertebrates Aplysia and Drosophila, there is only one aPKC gene. However, proteolytic cleavage of the full-length aPKC generates a catalytic domain-only product, similar to PKM-ζ (6). aPKC-λ and -ζ interact with Par proteins and function in the regulation of cell polarity in epithelia, neurons, and neural progenitors (7–9). The most well-known, albeit controversial, function of PKM-ζ is in learning and memory storage and as a target for reversal of chronic pain states (10, 11). In memory storage, PKM-ζ, through its sustained kinase activity, regulates AMPA receptor trafficking at the postsynaptic density. Although multiple isoforms of aPKC are often detected in cells, the functional significance of coexpression remains unclear.

The structural and functional asymmetry between the axon and the dendrites is essential for the physiological function of a neuron. The specification of a single axon from among multiple, equipotent neurites defines symmetry breaking and the establishment of polarization within a newborn neuron. In vitro culture of CNS neurons derived from embryonic rat hippocampus represents a model system to study the establishment of neuronal polarity (12, 13). Stage II neurons have multiple neurites without a discernable axon (14). Stage III neurons are defined by the specification of the axon (14). Neuronal polarity is observed in the absence of asymmetric external polarity cues in this system (15). Multiple intracellular signaling pathways have been implicated in neuronal polarity and axonogenesis, including the aPKC–Par polarity complex (14, 16–19). In a stage II neuron, where all immature neurites have the potential to become an axon, the aPKC–Par3 polarity complex is localized at the tip of every neurite. However, this complex is eventually restricted to and functionally active only in the axon in a stage III neuron (20). The stochastic activation of PI3K signaling and a cascade of small G proteins at a single neurite, along with positive feedback between these systems, is believed to regulate the biochemical activity of the polarity complex for the specification of the axon (16–20). The functional evidence of the role of aPKCs in axonogenesis originated primarily from pharmacological approaches. By using a myristoylated peptide inhibitor derived from the autoinhibitory pseudosubstrate peptide sequence of aPKC-ζ (myrZIP) that ostensibly is specific for aPKC-ζ, it was concluded that this specific isoform of aPKC was fundamental for axon specification (20). However, recent data challenge the specificity of myrZIP and its scrambled control peptide, as well as the isoform selectivity of this reagent (21–23). Zhang et al. overexpressed aPKC-ζ and ascribed a role of this kinase in neuronal polarization (24). Overexpression of the full-length kinase promoted neuronal polarization, whereas expression of N- or C-terminal fragments inhibited axon specification (24). Additionally, expression of aPKC-ζ, Par6, and Par3, but not aPKC-ζ alone, partially rescued the loss of neuronal polarity induced by the overexpression of microtubule affinity-regulating kinase (MARK2/Par1b), identified as a downstream substrate of aPKC (25). Notwithstanding, the fragments used in these studies were essentially exogenously expressed artificial constructs. The identity and function of the endogenous aPKC isoforms in neuronal polarity remain unknown.

Multiple isoforms of aPKC, including PKM-ζ, are present in embryonic hippocampal neurons (26). We hypothesized that aPKC isoforms may have distinct functions in establishing neuronal polarity. Here we describe that two aPKC isoforms, PKM-ζ and full-length aPKC-λ, are expressed in these cells. These isoforms are localized at distinct regions of a stage III neuron—aPKC-λ localizes at the presumptive axon, whereas PKM-ζ is distributed at non-axon-forming neurites. We identify a unique molecular interaction of PKM-ζ with Par3. PKM-ζ competes with full-length aPKC-λ for Par3 binding. The selective silencing of PKM-ζ disrupts neuronal polarity, resulting in the specification of supernumerary axons. Conversely, the overexpression of PKM-ζ, but not of a Par3-binding mutant of PKM-ζ, inhibits axon specification. Our results reveal a unique mechanism for the regulation of neuronal polarity by intermolecular competition between aPKC isoforms expressed within the same cell.

Results

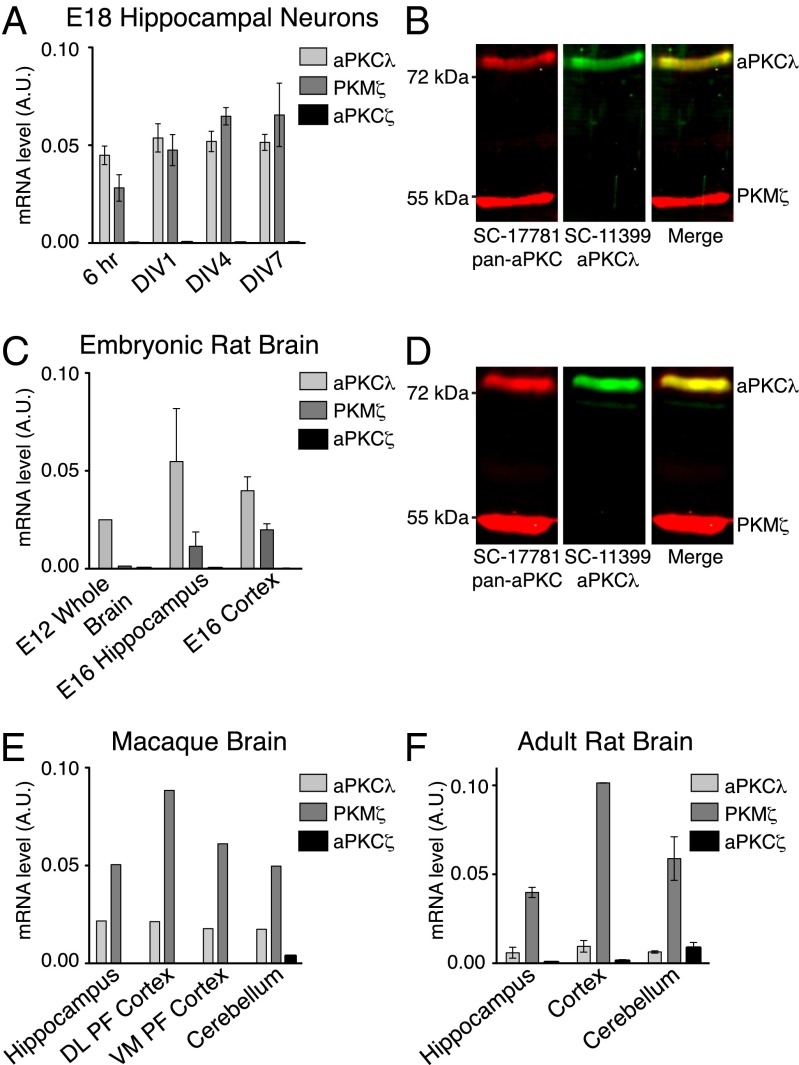

We characterized the expression of aPKC isoforms at various days during in vitro culture of hippocampal neurons by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) using primer pairs corresponding to unique regions of the three aPKC transcripts (Fig. S1A and Table S1). Expression of aPKC-λ and PKM-ζ was detected at different time points during in vitro culture (Fig. 1A), whereas aPKC-ζ was not detected over background levels (Fig. 1A). Additionally, we validated a panel of aPKC antibodies for isoform selectivity (Fig. S1B) and confirmed that aPKC-λ and PKM-ζ were expressed in hippocampal neurons by immunoblotting. Whereas SC-17781 recognized the ∼70-kDa aPKC-λ and the ∼55-kDa PKM-ζ, SC-11399 was specific for aPKC-λ and did not detect PKM-ζ (Fig. 1B). Characterization of aPKC expression in acutely isolated embryonic hippocampus validated our in vitro observations (Fig. 1 C and D). SC-216 antibody also recognized both aPKC-λ and PKM-ζ by Western blotting (Fig. S1C). An additional antibody, CS-C24E6, was specific for aPKC-ζ and PKM-ζ but failed to detect endogenous levels by Western blot (Fig. S1B). The expression pattern of aPKC isoforms was also conserved in a primate—macaque (Fig. 1E). Although only aPKC-λ and PKM-ζ were detected in the adult hippocampus, all three isoforms, including aPKC-ζ, were detected in the cerebellum (Fig. 1E and F).

Fig. 1.

Two isoforms of aPKC, aPKC-λ and PKM-ζ, are expressed in hippocampal neurons. Expression of the indicated aPKC isoforms, as detected by RT-qPCR (A, C, E, and F) and Western blot (B and D) in embryonic day (E) 18 rat hippocampal neurons in culture at indicated time points in vitro (A and B), embryonic rat brain tissues (C), E18 hippocampus (D), brain tissues of macaque (E), and adult rat (F). DL PF, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; VM PF, ventromedial prefrontal cortex. mRNA expression was normalized to GAPDH, and relative levels are presented in arbitrary units (A.U.), relative to GAPDH. Data are representative images or mean ± SEM of three independent biological replicates.

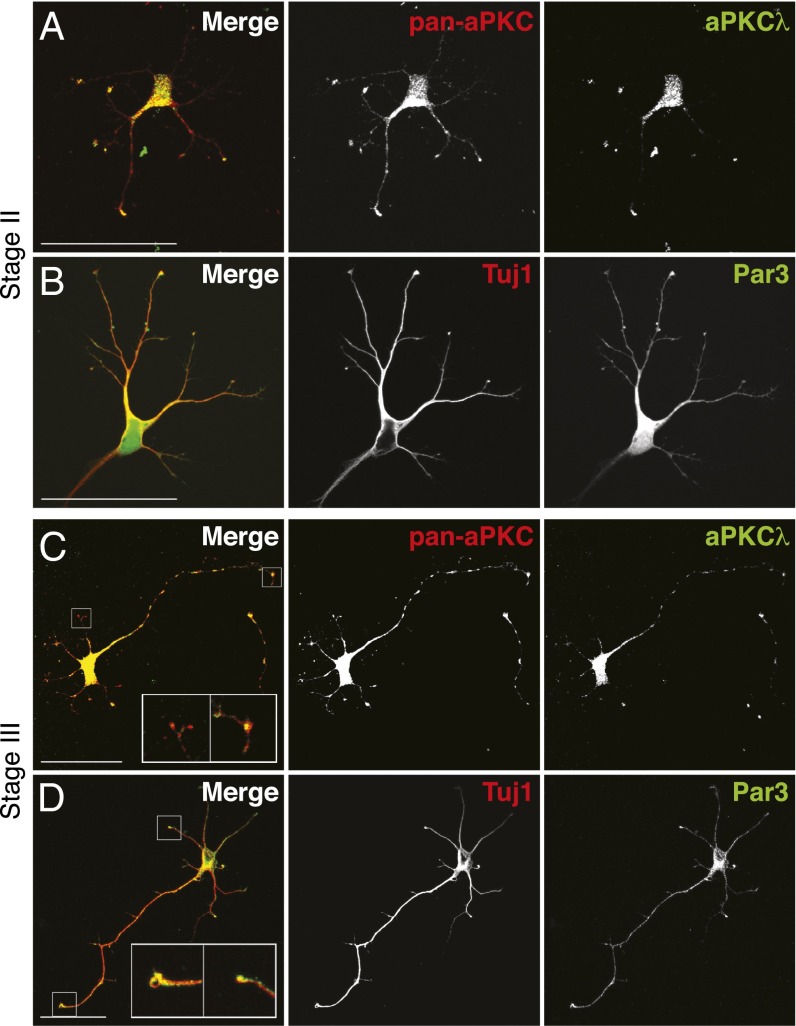

A role of full-length aPKC has been described in neuronal polarity (20). However, whether PKM-ζ also functions in specifying the axon remains unknown. We determined the localization of the two aPKC isoforms by using a combination of two antibodies—the antibody SC-17781 that recognizes both aPKC-λ and PKM-ζ (pan-aPKC) and SC-11399, which that is aPKC-λ–specific. In stage II neurons, both of the aPKC antibodies, as well as Par3 antibody, stained the tips of all immature neurites (Fig. 2 A and B). These results are consistent with the observation that aPKC-λ and Par3 localize to all neurites at stage II (18, 20, 27). In stage III neurons, staining with both aPKC antibodies was detected at the tip of the axon (Fig. 2 C, Right Inset). However, at the minor neurites (neurites not specified as axon), aPKC-λ–specific staining was absent, and only the pan-aPKC antibody staining was detected (Fig. 2 C, Left Inset). Therefore, in stage III neurons, PKM-ζ, but not aPKC-λ, localized to the minor neurites. Par3 staining was detected at the tip of the newly specified axon and also frequently detected at the minor neurites (Fig. 2D). Although we could not directly detect PKM-ζ when aPKC-λ was present, together, our results suggest a model in which both isoforms colocalize at neurites in stage II neurons. In contrast, in stage III, PKM-ζ localizes at the tips of minor neurites, spatially segregated from aPKC-λ, which localizes to the presumptive axon. This model is also consistent with the localization and function of PKM-ζ and Par3 in the postsynaptic regions of mature neurons (28–30).

Fig. 2.

aPKC-λ and PKM-ζ localization in hippocampal neurons overlap at stage II but is spatially segregated at stage III. (A and C) Pan-aPKC– and aPKC-λ–specific immunofluorescence staining at stages II and III. (C) aPKC-λ localization at the tip of the axon in stage III neuron (Right Inset) and pan-aPKC staining at the minor neurites (Left Inset). (B and D) Par3 and beta-III-tubulin/Tuj1 immunofluorescence staining at stages II and III Par3 localization at the axon tip (D, Left Inset), and at minor neurites (D, Right Inset). (Scale bars: 50 μm.) Data are representative images of three independent experiments.

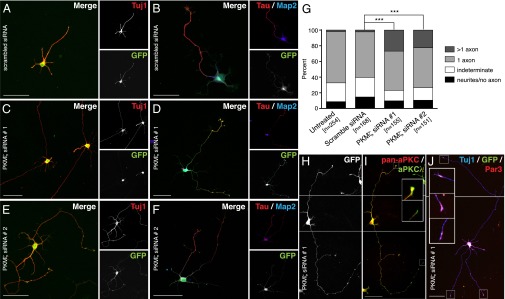

To investigate the functional role of PKM-ζ in axon specification, we selectively silenced PKM-ζ using two independent PKM-ζ–specific siRNA sequences during in vitro culture of hippocampal neurons. GFP plasmid was used for cotransfection, and transfected neurons were identified by GFP signal. The specificity of PKM-ζ silencing was confirmed by RT-qPCR, as well as by immunoblotting (Fig. S2 A–C). These results confirm that there were no significant changes to the levels of aPKC-λ transcript or protein levels after PKM-ζ silencing (Fig. S2 A–C). We observed, on average, ∼50% PKM-ζ–specific silencing in a pool of neurons in culture, consistent with the transfection efficiency of ∼40–50% as estimated by visual quantitation. Control, scrambled siRNA-transfected neurons featured only a single axon at stage III (Fig. 3 A and B). In contrast, multiple axon-like processes were observed in PKM-ζ–silenced neurons (Fig. 3 C and E and Fig. S3B). These processes were Tau+, indicating that these neurons indeed possessed supernumerary axons (Fig. 3 D and F and Fig. S3A). Quantitative analyses revealed that 27.7 ± 1.8% of neurons transfected with PKM-ζ siRNA 1 and 22.4 ± 1.0% of neurons transfected with PKM-ζ siRNA 2 had more than one axon, in contrast to 1.8 ± 0.4% and 3.5 ± 2.5% of scrambled siRNA-transfected or untransfected cells, respectively (Fig. 3G). These results indicate that PKM-ζ represses axon specification. Interestingly, after PKM-ζ silencing, aPKC-λ and Par3 were detected in the supernumerary axons (Fig. 3 H–J), suggesting that loss of PKM-ζ allows the persistence of aPKC-λ localization at all neurites leading to the multiple-axon phenotype. Our observations indicate that PKM-ζ expression at minor neurites at stage III may have an active role in precluding axon specification.

Fig. 3.

Silencing PKM-ζ leads to the formation of supernumerary axons. (A–F and H–J) E18 rat hippocampal neurons were cotransfected with GFP plasmid and either scrambled (A and B) or PKM-ζ–specific siRNA sequences (PKM-ζ siRNA 1, C and D; PKM-ζ siRNA 2, E and F). Cells were fixed on day 3 in vitro (DIV3) and stained with beta-III-tubulin/Tuj1 (A, C, and E) or Tau and Map2 (B, D, and F). (G–I) Quantitation of the effects of siRNAs on neuronal polarity (G). GFP (H), and pan-aPKC– and aPKC-λ–specific immunofluorescence staining (I) in stage III neurons cotransfected with a GFP plasmid and PKM-ζ siRNA 1. (J) Par3 and Tuj1 immunofluorescence and GFP signal in stage III neurons cotransfected with a GFP plasmid and PKM-ζ siRNA 1. Images in H–J are composites. (Scale bars: 50 μm.) Data are representative images or mean ± SEM of neurons counted (n) from three independent experiments. ***P < 0.001; χ2 test.

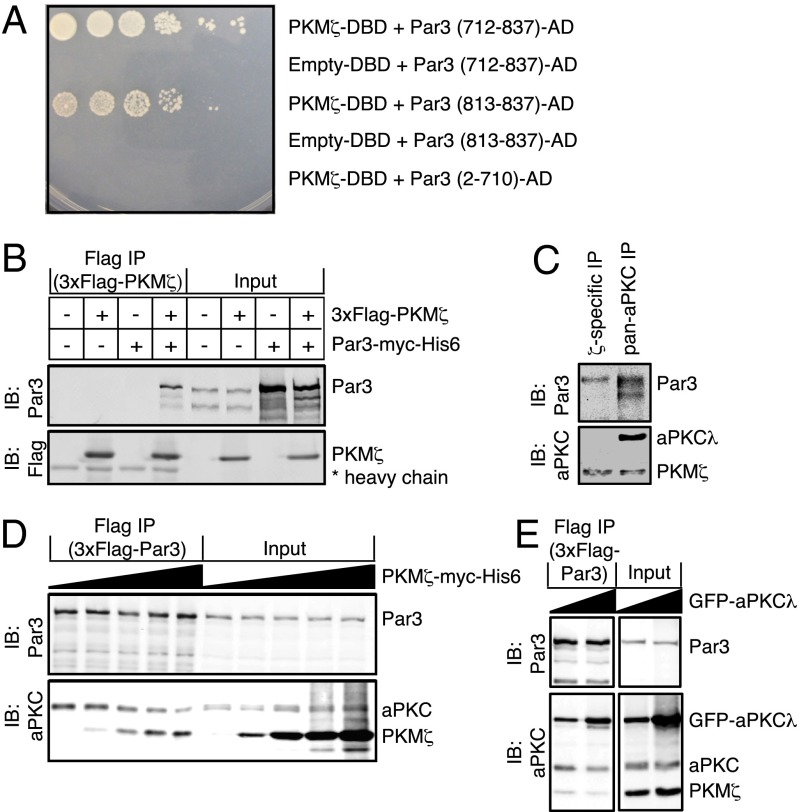

We hypothesized that aPKC-λ and PKM-ζ may have competing biochemical interactions with common partners, such as Par3. Although Par3 is established as an interaction partner of full-length aPKC isoforms, whether it can also bind PKM-ζ is unknown. Therefore, we directly tested whether PKM-ζ can interact with Par3. Using the yeast two-hybrid system, we observed that PKM-ζ can indeed directly interact with a region of Par3 encoding amino acids 813–837, homologous to the domain through which Par3 binds aPKC-ζ (31) (Fig. 4A). Next, we expressed Flag-tagged PKM-ζ and myc-tagged Par3 in HEK293 cells and demonstrated that these proteins interact by coimmunoprecipitation (Fig. 4B). We also reciprocally tagged these proteins and confirmed this interaction (Fig. S4). Importantly, we did not detect interaction between aPKC-λ and PKM-ζ in these experiments (Fig. S5C). Finally, the PKM-ζ–specific antibody (CS-C24E6) successfully coimmunoprecipitated Par3 from untransfected E19 rat hippocampal lysates (Fig. 4C). This result indicates that endogenous PKM-ζ interacts with Par3 in neurons. Furthermore, we established a Flag-tagged Par3-expressing stable HEK293 cell line and transfected increasing amounts of PKM-ζ plasmid DNA. Increased expression of PKM-ζ in these cells correlated with increased coimmunoprecipitation with 3xFlag–Par3 and a progressively decreased association of endogenous aPKC with Par3 (Fig. 4D). These experiments provide biochemical evidence of an interaction of PKM-ζ with Par3 and indicate that PKM-ζ can directly compete with aPKC for Par3 binding. The reverse experiment, in which PKM-ζ overexpression was held constant and expression of GFP-tagged aPKC-λ was increased, demonstrates that there is a mutually antagonistic relationship between the two complexes. aPKC-λ can displace PKM-ζ for Par3 binding (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

PKM-ζ and aPKC-λ mutually compete for biochemical interaction with Par3. (A) Yeast two-hybrid interaction of PKM-ζ and the indicated amino acid sequences of Par3. DBD, DNA-binding domain; AD, activation domain. (B) 3xFlag–PKM-ζ alone, Par3–myc–His6 alone, or both were expressed in HEK293 cells as indicated (+). Anti-Flag antibody was used for immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitates and input samples were resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against Par3 and Flag. (C) ζ-Specific or pan-aPKC antibodies were used for immunoprecipitation from E19 rat hippocampal lysates. Immunoprecipitates were resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against Par3 and pan-aPKC. (D) Stably transfected Flag-tagged Par3 HEK293 cells were transfected with increasing concentrations of a PKM-ζ–myc–His6-encoding plasmid. Anti-Flag antibody was used for immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitates and input samples were resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against Par3 and pan-aPKC. (E) Stably transfected Flag-tagged Par3 HEK293 cells were transfected with PKM-ζ–myc–His6 and increasing concentrations of GFP–aPKC-λ–encoding plasmid. Anti-Flag antibody was used for immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitates and input samples were resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against Par3 and pan-aPKC. Data are representative images of three independent experiments.

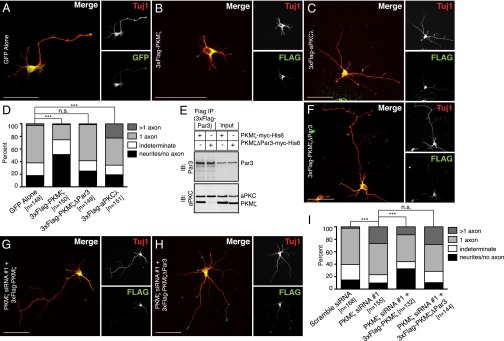

Our biochemical results predict that altering the stoichiometry of aPKC isoforms would disrupt neuronal polarity. Overexpression of PKM-ζ should prevent axon specification, whereas aPKC-λ overexpression should lead to multiple axons. In control experiments (GFP transfection) 59.8 ± 2.8% had a single, normal axon and 17.4 ± 0.6% of neurons failed to develop an axon; 2.7 ± 0.3% neurons had supernumerary axons (Fig. 5 A and D). PKM-ζ overexpression resulted in neurons that lacked a discernable axon; 51.3 ± 1.3% of neurons failed to develop an axon (Fig. 5 B and D and Fig. S3C). Conversely, increasing the amount of aPKC-λ by overexpression led to supernumerary axons; 24.3 ± 5.9% of neurons featured multiple axons (Fig. 5 C and D and Fig. S3D).

Fig. 5.

PKM-ζ directs neuronal polarity in a Par3-binding-dependent manner. (A–C and F) E18 hippocampal neurons were transfected with GFP alone (A), 3xFlag–PKM-ζ (B), 3xFlag–aPKC-λ (C), or PKM-ζ–ΔPar3 (F). Neurons were fixed at DIV3 and stained with antibodies detecting Tuj1 and Flag. (D) Quantitation of the phenotypic effect in experiments described above. (E) PKM-ζ–myc–His6 or Par3-binding mutant PKM-ζΔPar3–myc–His6 were expressed in HEK293 cells as indicated (+). Anti-Flag antibody was used for immunoprecipitation. Immunoprecipitates and input samples were resolved by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotted with antibodies against Par3 and pan-aPKC. (G and H) PKM-ζ was silenced in E18 hippocampal neurons, and siRNA-resistant PKM-ζ (G) or PKM-ζΔPar3 (H) was expressed. Neurons were fixed at DIV3 and stained with antibodies detecting Tuj1 and Flag. (I) Quantitation of the phenotypic effect in experiments described above. (Scale bars: 50 μm.) Data are representative images or mean ± SEM of neurons counted (n) from three independent experiments. n.s., nonsignificant; ***P < 0.001; χ2 test.

Furthermore, we hypothesized that PKM-ζ effects on neuronal polarity would be dependent on its ability to bind Par3. Based on the published structure of aPKC-λ–Par3 interaction (32), we deleted seven amino acids in PKM-ζ, corresponding to the Par3-binding region of aPKC-λ (Fig. S5A). This construct (PKM-ζΔIITDNPD; henceforth referred to as PKM-ζΔPar3) failed to bind Par3 (Fig. 5E and Fig. S5 B and C). Unlike PKM-ζ, PKM-ζΔPar3 overexpression did not significantly alter axon specification or neuronal polarity (Fig. 5F). We found that 56.9 ± 2.9% of PKM-ζΔPar3-transfected neurons exhibited a normal morphology with 26.1 ± 4.4% failing to develop an axon and 1.1 ± 1.1% exhibiting multiple axons (Fig. 5D). We also expressed an siRNA-resistant PKM-ζ in neurons where the endogenous PKM-ζ was silenced. This process resulted in a partial rescue of normal morphology (Fig. 5G). In contrast, an siRNA-resistant form of PKM-ζΔPar3 failed to rescue the effects of PKM-ζ silencing (Fig. 5H). As shown in Fig. 3G originally and reproduced in Fig. 5I, scrambled siRNA had only 1.8 ± 0.4% neurons with multiple axons, whereas PKM-ζ silencing resulted in 27.7 ± 1.8% neurons with supernumerary axons. Additionally, 13.1 ± 1.9% of neurons cotransfected with PKMζ-siRNA and siRNA-resistant PKMζ had multiple axons indicating a partial rescue (Fig. 5I). However, 28.8 ± 2.3% of PKM-ζ silenced, PKM-ζΔPar3 rescue cells had more than one axon (Fig. 5I). Therefore, Par3 binding is essential for PKM-ζ function in regulating neuronal polarity. These results are consistent with our model in which PKM-ζ has an axon-repressive role, whereas aPKC-λ promotes axon specification. The competing interactions of these two aPKC isoforms for Par3 binding regulate neuronal polarity.

Discussion

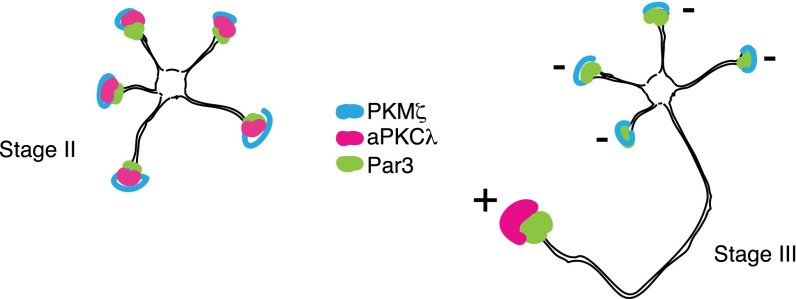

In hippocampal neurons, polarity is established as a single axon is specified from multiple, equipotent neurites. Axon specification involves the localization and activation of aPKC–Par complex at a unique neurite. Molecular mechanisms that favor biochemical activation and physiological function of the aPKC–Par complex at the presumptive axon represent stochastic, positive signals and positive feedbacks (16–19). If there are active signals that prevent other neurites from adopting axonal fate, they are not known. We demonstrate a previously undescribed functional role of the truncated aPKC isoform, PKM-ζ that is coexpressed with aPKC-λ in hippocampal neurons, in regulating neuronal polarity through intermolecular competition for Par3 binding. PKM-ζ biochemically disrupts full-length aPKC–Par3 complex at the minor neurites and prevents their specification into axons. In the absence of PKM-ζ, the tightly regulated process of specifying only one axon is compromised, and neurons with multiple axons result. Therefore, a combination of positive signals favoring assembly of aPKC–Par polarity complexes at the presumptive axon together with an opposing negative signal, PKM-ζ–mediated disruption of the formation of aPKC–Par polarity complex at the minor neurites, leads to hippocampal neuron polarization (Fig. 6). Recently, mathematical modeling and experimental validation approaches have begun to reveal how negative feedback and mutual antagonism mechanisms add to positive feedback pathways and allow for stability and robustness of polarity signaling in yeast and Drosophila (33–35). Our proposed model is consistent with such paradigms that amplify transient, stochastic signal variation into symmetry breaking and the generation of stable asymmetry. The biochemical mechanisms by which the aPKC-λ–Par6–Par3 complex favors axonogenesis, while the PKM-ζ–Par3 complex inhibits axon formation remains to be elucidated. However, a recent paper describes conformation-dependent function of Par3 in differentially regulating microtubule organization and growth at dendrites vs. axon (36). It is possible that aPKC-λ–Par6 vs. PKM-ζ binding to Par3 can lead to distinct Par3 conformations.

Fig. 6.

Schematic representation of the spatial segregation of polarity components and axon specification. aPKC isoforms and Par3 are colocalized at the tips of immature neurites at stage II. Whereas aPKC-λ is restricted to the axon at stage III, PKM-ζ is localized at minor neurites. aPKC–Par3 complex favors axonogenesis (+), whereas PKM-ζ–Par3 complex represses axon formation (−).

Whether the localization of positive signals such as PI3K-mediated aPKC–Par complex activation at the nascent axon vs. negative signals such as PKM-ζ–mediated disruption of aPKC–Par complex at the minor neurites is regulated by external cues in vivo remains unknown. Although the “Banker culture” is a well-recognized model for investigating cell-intrinsic mechanisms that can define neuronal polarity and specify an axon in cultured neurons (13), the necessity and sufficiency of these mechanisms in axon specification in vivo remain poorly understood. For example, the genetic loss of function of Drosophila Par3, Par6, or aPKC was shown not to affect axon formation in vivo (37). Although neural precursor-specific genetic ablation of aPKC-λ in mouse (aPKC-λloxP/loxP/Nestin–cre) resulted in early neurodevelopmental abnormalities (38), recent studies that knock out Prkcz in mice demonstrate no effect on learning and memory and do not report any alterations in brain anatomy or neuronal circuits (22, 23). These reports indicate that, perhaps unsurprisingly, redundant mechanisms govern physiologically fundamental processes such as axon specification and memory storage in vivo. For example, several mechanisms exist that prune exuberant axonal connections and ensure proper neuronal circuits (39, 40). Even the regulation of polarity is ascribed to functionally redundant pathways, and single gene knockouts mostly fail to reveal phenotypic effects (41). The in vivo role of PKM-ζ in axon specification remains unaddressed in the present study.

The PKM-ζ transcript, although primarily neuronal in its expression pattern, has been described to be present in nonneuronal cells (5). Alternatively, although neuronal expression of PKM-ζ is regulated at the transcriptional level, the free catalytic domain of aPKC-ζ can be generated by protease cleavage in other cell types (42, 43). It is tempting to speculate that this truncated isoform is also capable of disrupting aPKC–Par complexes. It will be interesting to test whether loss of polarity in epithelial cells, such as during the loss of barrier function in the intestine during inflammation or aberrant migration of cancer cells, is mediated by PKM-ζ expression or proteolytic processing of full-length aPKC-ζ.

Materials and Methods

Rat Hippocampal Cell Culture.

Timed pregnant Sprague–Dawley rats were purchased from Harlan Laboratories. All experimental procedures were conducted with approval from the University of Arizona Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Hippocampal neurons were isolated from E18 rat hippocampus by methods described by Kaech and Banker (44). Stages of polarization within transfected populations of neurons were quantified by counting at least 150–250 GFP or Flag-positive neurons, and categorizing was done as described in Dotti et al. (13). In brief, short processes of equal length were classified as neurites. “Indeterminate” refers to a single process of length greater than other neurites, but not greater than three times the length of other processes. Axons were defined as Tau-positive processes whose length exceeded three times the length of other minor processes.

Plasmids.

Mutations were generated by site-directed mutagenesis as described in Zheng et al. (45). siRNA-resistant plasmids were generated by introducing silent mutations by site-directed mutagenesis. Table S2 contains a list of all plasmids.

Yeast Two-Hybrid Assay.

Yeast two-hybrid DNA-binding domain and activation domain constructs were subcloned into the pGAD-GH and pGBT9 backbones. Transformation and growth were performed in the strain PJ69-4A (MATα leu2-3, 112 ura3-52 trp1-901, his3-200 Gal4Δ gal80Δ::GAL2-ADE2 lys2::GAL1-HIS3 met2::GAL7-LacZ) as described in James et al. (46). Plasmids were cotransfected onto synthetic defined (SD)–Leu–Trp dropout plates. Independent colonies were grown under selection, and saturated cultures were used for dilution series plating. The ADE (Adenine) reporter was selected for high stringency.

Imaging and Microscopy.

Immunofluorescent imaging was performed on Olympus FluoView1000 or FluoView1200 confocal laser scanning microscope. Images of hippocampal neurons were captured by using a 60× 1.42-numerical-aperture oil-immersion objective. All images are presented as z-projections of z-stacks. Images were processed by using Adobe Photoshop CS5.

Western Blotting and Coimmunoprecipitation.

Coimmunoprecipitations were performed as described in SI Materials and Methods and analyzed by Western blotting. A list of primary and secondary antibodies and concentrations used can be found in Table S3. Signal was detected by using the Odyssey Imaging System (LI-COR).

Statistics.

Statistical significance for stages of neuronal polarization was determined by χ2 test using Prism 5. All data are presented as mean ± SEM unless indicated otherwise.

Detailed description of materials and methods can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shane Andrews (Olympus) and Dr. Pat Mantyh (University of Arizona) for their support for confocal imaging and Carla V. Rothlin for critical evaluation of the manuscript and helpful suggestions and discussions. This research was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 CA95060 (to S.G.), R01 NS065926 (to T.J.P.), R01 DK084047 (to J.M.W.), and T32 CA009213 (to E.K.M.) and an Achievement Rewards for College Scientists Foundation Scholar Award (to S.S.P.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1301588110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Goldstein B, Macara IG. The PAR proteins: Fundamental players in animal cell polarization. Dev Cell. 2007;13(5):609–622. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCaffrey LM, Macara IG. Signaling pathways in cell polarity. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2012;4(6) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a009654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson BJ. Cell polarity: Models and mechanisms from yeast, worms and flies. Development. 2013;140(1):13–21. doi: 10.1242/dev.083634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirai T, Chida K. Protein kinase Czeta (PKCzeta): Activation mechanisms and cellular functions. J Biochem. 2003;133(1):1–7. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hernandez AI, et al. Protein kinase M zeta synthesis from a brain mRNA encoding an independent protein kinase C zeta catalytic domain. Implications for the molecular mechanism of memory. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(41):40305–40316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307065200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sacktor TC. Memory maintenance by PKMζ—an evolutionary perspective. Mol Brain. 2012;5:31. doi: 10.1186/1756-6606-5-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohno S. Intercellular junctions and cellular polarity: The PAR-aPKC complex, a conserved core cassette playing fundamental roles in cell polarity. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13(5):641–648. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00264-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henrique D, Schweisguth F. Cell polarity: The ups and downs of the Par6/aPKC complex. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2003;13(4):341–350. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(03)00077-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh S, et al. Instructive role of aPKCzeta subcellular localization in the assembly of adherens junctions in neural progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(1):335–340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705713105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sacktor TC. How does PKMζ maintain long-term memory? Nat Rev Neurosci. 2011;12(1):9–15. doi: 10.1038/nrn2949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Asiedu MN, et al. Spinal protein kinase M ζ underlies the maintenance mechanism of persistent nociceptive sensitization. J Neurosci. 2011;31(18):6646–6653. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6286-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Banker GA, Cowan WM. Rat hippocampal neurons in dispersed cell culture. Brain Res. 1977;126(3):397–425. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(77)90594-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dotti CG, Sullivan CA, Banker GA. The establishment of polarity by hippocampal neurons in culture. J Neurosci. 1988;8(4):1454–1468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-04-01454.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Polleux F, Snider W. Initiating and growing an axon. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(4):a001925. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dotti CG, Banker GA. Experimentally induced alteration in the polarity of developing neurons. Nature. 1987;330(6145):254–256. doi: 10.1038/330254a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Insolera R, Chen S, Shi SH. Par proteins and neuronal polarity. Dev Neurobiol. 2011;71(6):483–494. doi: 10.1002/dneu.20867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng PL, Poo MM. Early events in axon/dendrite polarization. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2012;35:181–201. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wiggin GR, Fawcett JP, Pawson T. Polarity proteins in axon specification and synaptogenesis. Dev Cell. 2005;8(6):803–816. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barnes AP, Polleux F. Establishment of axon-dendrite polarity in developing neurons. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:347–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi SH, Jan LY, Jan YN. Hippocampal neuronal polarity specified by spatially localized mPar3/mPar6 and PI 3-kinase activity. Cell. 2003;112(1):63–75. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01249-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wu-Zhang AX, Schramm CL, Nabavi S, Malinow R, Newton AC. Cellular pharmacology of protein kinase Mζ (PKMζ) contrasts with its in vitro profile: Implications for PKMζ as a mediator of memory. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(16):12879–12885. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.357244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volk LJ, Bachman JL, Johnson R, Yu Y, Huganir RL. PKM-ζ is not required for hippocampal synaptic plasticity, learning and memory. Nature. 2013;493(7432):420–423. doi: 10.1038/nature11802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee AM, et al. Prkcz null mice show normal learning and memory. Nature. 2013;493(7432):416–419. doi: 10.1038/nature11803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhang X, et al. Dishevelled promotes axon differentiation by regulating atypical protein kinase C. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9(7):743–754. doi: 10.1038/ncb1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen YM, et al. Microtubule affinity-regulating kinase 2 functions downstream of the PAR-3/PAR-6/atypical PKC complex in regulating hippocampal neuronal polarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(22):8534–8539. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509955103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jiang X, Naik MU, Hrabe J, Sacktor TC. Developmental expression of the protein kinase C family in rat hippocampus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1994;78(2):291–295. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(94)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schwamborn JC, Püschel AW. The sequential activity of the GTPases Rap1B and Cdc42 determines neuronal polarity. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(9):923–929. doi: 10.1038/nn1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang H, Macara IG. The PAR-6 polarity protein regulates dendritic spine morphogenesis through p190 RhoGAP and the Rho GTPase. Dev Cell. 2008;14(2):216–226. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2007.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang H, Macara IG. The polarity protein PAR-3 and TIAM1 cooperate in dendritic spine morphogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2006;8(3):227–237. doi: 10.1038/ncb1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruiz-Canada C, et al. New synaptic bouton formation is disrupted by misregulation of microtubule stability in aPKC mutants. Neuron. 2004;42(4):567–580. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00255-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nagai-Tamai Y, Mizuno K, Hirose T, Suzuki A, Ohno S. Regulated protein-protein interaction between aPKC and PAR-3 plays an essential role in the polarization of epithelial cells. Genes Cells. 2002;7(11):1161–1171. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang C, Shang Y, Yu J, Zhang M. Substrate recognition mechanism of atypical protein kinase Cs revealed by the structure of PKCι in complex with a substrate peptide from Par-3. Structure. 2012;20(5):791–801. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chau AH, Walter JM, Gerardin J, Tang C, Lim WA. Designing synthetic regulatory networks capable of self-organizing cell polarization. Cell. 2012;151(2):320–332. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Howell AS, et al. Negative feedback enhances robustness in the yeast polarity establishment circuit. Cell. 2012;149(2):322–333. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fletcher GC, Lucas EP, Brain R, Tournier A, Thompson BJ. Positive feedback and mutual antagonism combine to polarize Crumbs in the Drosophila follicle cell epithelium. Curr Biol. 2012;22(12):1116–1122. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen S, et al. Regulation of microtubule stability and organization by mammalian Par3 in specifying neuronal polarity. Dev Cell. 2013;24(1):26–40. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rolls MM, Doe CQ. Baz, Par-6 and aPKC are not required for axon or dendrite specification in Drosophila. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7(12):1293–1295. doi: 10.1038/nn1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Imai F, et al. Inactivation of aPKClambda results in the loss of adherens junctions in neuroepithelial cells without affecting neurogenesis in mouse neocortex. Development. 2006;133(9):1735–1744. doi: 10.1242/dev.02330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Faulkner RL, Low LK, Cheng HJ. Axon pruning in the developing vertebrate hippocampus. Dev Neurosci. 2007;29(1-2):6–13. doi: 10.1159/000096207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo L, O’Leary DD. Axon retraction and degeneration in development and disease. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2005;28:127–156. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.28.061604.135632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fievet BT, et al. Systematic genetic interaction screens uncover cell polarity regulators and functional redundancy. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(1):103–112. doi: 10.1038/ncb2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith L, et al. Activation of atypical protein kinase C zeta by caspase processing and degradation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(51):40620–40627. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M908517199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Frutos S, Moscat J, Diaz-Meco MT. Cleavage of zetaPKC but not lambda/iotaPKC by caspase-3 during UV-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(16):10765–10770. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaech S, Banker G. Culturing hippocampal neurons. Nat Protoc. 2006;1(5):2406–2415. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zheng L, Baumann U, Reymond JL. An efficient one-step site-directed and site-saturation mutagenesis protocol. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32(14):e115. doi: 10.1093/nar/gnh110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.James P, Halladay J, Craig EA. Genomic libraries and a host strain designed for highly efficient two-hybrid selection in yeast. Genetics. 1996;144(4):1425–1436. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.