Abstract

This study examined the effect of the volume of fluid ingested on urine concentrating ability during prolonged heavy exercise in a hot environment at low levels of dehydration. Seven healthy males performed 105 min of intermittent cycle exercise at 70% maximum oxygen uptake (32°C, 60% relative humidity) while receiving no fluid ingestion (NF), voluntary fluid ingestion (VF), partial fluid ingestion equivalent to one-half of body mass loss (PF), and full fluid ingestion equivalent to body mass loss (FF). Fluid (5°C, 3.4% carbohydrate, 10.5 mmol·L-1 sodium) was ingested just before commencing exercise and at 15, 33, 51, 69, and 87 min of exercise, and the total amount of fluid ingested in PF and FF was divided into six equal volumes. During exercise, body mass loss was 2.2 ± 0.2, 1.1 ± 0.5, 1.1 ± 0.2, and 0.1 ± 0.2% in NF, VF, PF, and FF, respectively, whereas total sweat loss was about 2% of body mass in each trial. Subjects in VF ingested 719 ± 240 ml of fluid during exercise; the volume of fluid ingested was 1.1 ± 0.4% of body mass. Creatinine clearance was significantly higher and free water clearance was significantly lower in FF than in NF during exercise. Urine flow rate during exercise decreased significantly in NF. There were significant decreases in creatinine and osmolar clearance and was a significant increase in free water clearance during exercise in NF and VF. Creatinine clearance decreased significantly and free water clearance increased significantly during exercise in PF. There was no statistical change in urinary indices of renal function during exercise in FF. The findings suggest that full fluid ingestion equivalent to body mass loss has attenuated the decline in urine concentrating ability during prolonged heavy exercise in a hot environment at low levels of dehydration.

Key points.

During prolonged heavy exercise in a hot environment at low levels of dehydration, fluid ingestion equivalent to body mass loss results in no changes in urinary indices of renal function.

Fluid ingestion equivalent to body mass loss can attenuate the decline in urine concentrating ability during exercise.

Ad libitum or voluntary fluid ingestion is ineffective in reducing the decline in urine concentrating ability during exercise.

Key words: Body fluid, dehydration, heat stress, rehydration, renal function

Introduction

Fluid ingestion during prolonged exercise is able to attenuate progressive dehydration and body fluid imbalance. Although the large part of volume and composition of the body fluids are maintained by the kidneys, the relationship between the volume of fluid ingested and renal function during exercise remains unclear. Partial fluid ingestion, consuming volumes less than body mass loss, has been demonstrated to be effective in reducing the decline in urine concentrating ability during prolonged exercise in temperate (Castenfors and Piscator, 1967; Mallié et al., 2002) and hot (Melin et al., 1997) environments. These studies have compared only no-fluid trial to a trial with imposed fluid ingestion, however, the effect of differing fluid volumes ingested on urine concentrating ability during prolonged exercise has never been investigated. Moreover, although the fact that ad libitum or voluntary fluid ingestion is the most common procedure in the athletic and occupational fields, there is only one investigation comparing the effect of voluntary fluid ingestion and imposed fluid ingestion on renal response to exercise (Dann et al., 1990); but this study was conducted in a cold environment (0°C). Thus, the variation in renal function during exercise between voluntary fluid ingestion and imposed fluid ingestion is still poorly understood. Because there is a considerable variability in the volume of fluid ingested between individuals when they ingested fluid voluntarily during exercise (Maughan and Shirreffs, 2008; Sawka et al., 2007), there may be a large interindividual variability in urine concentrating ability.

It has been known that exercise results in the decline in urine concentrating ability in proportion to its intensity (Freund et al., 1991; Grimby, 1965; Kachadorian and Johnson, 1970; Wade and Claybaugh, 1980). Several studies (Freund et al., 1991; Kachadorian and Johnson, 1970; Refsum and Strømme, 1975; 1978; Wade and Claybaugh, 1980) have reported the decline in urine concentrating ability, as reflected by reductions in glomerular filtration rate (GFR) and urine volume and the elevation in free water clearance (CH2O), when the exercise intensity is higher than 60% of maximum oxygen uptake (VO2max). The decline in renal function associated with exercise has been attributed to the decrease in GFR (Freund et al., 1991; Melin et al., 1997; Refsum and Strømme, 1978; Wade et al., 1989), resulting from the decrease in renal blood flow (RBF). Radigan and Robinson, 1949 have demonstrated that the combined effects of exercise-heat stress caused reductions in renal plasma flow (RPF) and GFR that were 20% and 29% greater, respectively, than the effect of exercise alone. Then, Smith, Robinson, and Pearcy (1952) have observed that the combined effects of exercise- heat stress and dehydration reduce RPF and GFR to a greater degree than the effects of exercise- heat stress alone. It is therefore reasonable to expect that renal function is further impaired when dehydration and heat stress are added to a high intensity exercise. Under these conditions, however, no studies have examined the influence of drink volume on urine concentrating ability.

Therefore, the first aim of this study was to investigate the effect of consuming different volumes of fluid on urine concentrating ability during prolonged exercise in a hot environment at dehydration. The second aim was to compare the effect of voluntary fluid ingestion and imposed fluid ingestion on renal response to exercise. To address these questions, this study compared full fluid ingestion equivalent to body mass loss, partial fluid ingestion equivalent to one-half of body mass loss, voluntary fluid ingestion, and no fluid ingestion. It was hypothesized that full fluid ingestion, compared with other fluid ingestions, would be effective in reducing the decline in urine concentrating ability.

Methods

Subjects

Seven healthy males (age 22.6 ± 3.3 years; height 1.69 ± 0.06 m; body mass 68.4 ± 4.9 kg; VO2max 49.0 ± 2.8 ml·min-1·kg-1,) participated in this investigation. All subjects were active, but none was accustomed to exercise in a hot environment at the time of the study. Prior to volunteering all participants received written information regarding the nature and purpose of the study. Following an opportunity to ask any questions, a written statement of consent was signed. The protocol employed was approved by the local Ethical Advisory Committee, and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Experimental protocol

All subjects completed a preliminary test, a familiarization trial, and four experimental trials. The preliminary test consisted of incremental cycle exercise (Monark 816, Varberg, Sweden) to volitional exhaustion and was used to determine VO2max (AE300S, Minato Medical Science, Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The familiarization trial followed the same format as the experimental trials. This was undertaken to familiarize the subjects with all the procedures involved in the study. During the familiarization trial, subjects did not ingest any fluid. Since it has been known that dehydration of less than 2% of body mass is common in most athletic events (Casa, 2000; Noakes and Martin, 2002), the familiarization trial and all experimental trials were performed 105 min of intermittent cycle exercise at 70% VO2max, which consisted of 6 bouts of 15 min of exercise with 3 min rest intervals in between the bouts. The trials took place in a climatic chamber with ambient temperature and relative humidity maintained at 32°C and 60%, respectively, and the estimated exercise-induced dehydration was about 2% of body mass. Following the familiarization trial, we confirmed that body mass loss averaged about 2% of body mass. During an experimental trial, subjects received one of the following: 1) no fluid ingestion (NF), 2) voluntary fluid ingestion (VF), 3) partial fluid ingestion equivalent to one-half of body mass loss or 1% of body mass (PF; total volume 691 ± 46 ml), and 4) full fluid ingestion equivalent to body mass loss or 2% of body mass (FF; total volume 1370 ± 87 ml). Since fluid consumption that exceeds sweating rate is the primary factor leading to hyponatremia during exercise (Maughan and Shirreffs, 2008; Sawka et al., 2007), we did not investigate fluid consumption exceeding body mass loss. During the PF and FF trials, fluid was ingested just before commencing exercise and then at 15, 33, 51, 69, and 87 min of exercise, and the total amount of fluid ingested was divided into six equal portions. Each subject completed four experimental trials which were randomized and undertaken in a counterbalanced manner. Trials were separated by at least 7 days. The rehydration beverage was a commercially available carbohydrate-electrolyte beverage (POCARI SWEAT, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), which was diluted with water to one-half of the original concentration (final concentration: 3.4% carbohydrate, 10.5 mmol·L-1 sodium, 2.5 mmol·L-1 potassium, and 153 mOsm·kgH2O-1 osmolality). During the VF, PF, and FF trials, subjects ingested this solution to enhance its palatability (Shirreffs et al., 2004), gastric empting rate (Vist and Maughan, 1995), and water absorption from the small intestine (Rehrer et al., 1992), and to attenuate copious urine production (Shirreffs et al., 1996). In addition, the solution was maintained at about 5°C to enhance gastric empting rate (Costill and Saltin, 1974) and the volume consumed (Mündel et al., 2006). Subjects were instructed to record dietary intake and physical activity during the 24 h before the first trial and to replicate this on the day prior to the subsequent experimental trials. No exercise or alcohol consumption was permitted in the 24 h before each trial.

On the morning of the trial, subjects emptied their bladder voluntarily and recorded this time to calculate urine flow rate (UFR). Subjects entered the laboratory after an overnight fast, other than the consumption of a controlled breakfast (CALORIE MATE, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; composition: 400 kcal of energy) and the ingestion of 250 ml of isotonic carbohydrate-electrolyte beverage (POCARI SWEAT) 3 h before the start of the trial. Upon arrival a urine sample was collected and nude body mass was measured to the nearest 10 g (MT-150, Ishida, Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan). Subjects then inserted a rectal thermistor (Z2502, Takara Industries, Co. Ltd., Yokohama, Japan) 13 cm beyond the anal sphincter for the measurement of rectal temperature (Tre). Skin thermistors (PZL64, Takara Industries, Co. Ltd., Yokohama, Japan) were attached to the skin at four sites (chest, upper arm, thigh, and calf) to determine mean skin temperature (Tsk; Ramanathan, 1964), and a heart rate (HR) telemetry band was positioned (Vantage NV, Polar, Kempele, Finland). Subjects were dressed in cycling shorts, socks, and shoes for all trials.

Subjects then rested in a seated position for 15 min in a comfortable environment (25-28°C), and then venous blood samples were taken from an antecubital vein. Subjects entered the climatic chamber and began 105 min of intermittent cycle exercise at 70% VO2max (60 rev·min-1). Tre, skin temperatures, and HR were recorded at 3-min interval during exercise. Venous blood samples were taken from an antecubital vein at 51 min and at the end of the exercise. Following the exercise, subjects returned to a comfortable environment and emptied their bladder voluntarily. Nude body mass was re-measured to allow the estimation of total sweat loss after all instruments were removed. Total sweat loss was calculated as: body mass loss + the volume of fluid ingested - urine volume.

Blood and urine analyses

Hemoglobin concentration (cyanmethemoglobin method) and hematocrit (microcentrifugation) were used to estimate percentage change in plasma volume (%∆PV) relative to the resting sample (Dill and Costill, 1974). Serum and urine osmolality were measured by freezing-point depression (MARK3, Fiske Associates, Norwood, MA, USA). Serum and urine concentrations of sodium and potassium were measured by flame photometry (FP-33D, Hekisa Science, Co., Ltd., Funabashi, Japan). Serum and urine concentrations of chloride were measured by coulometric titration (CL-3, Hiranuma Industries, Co., Ltd., Mito, Japan). Serum and urine concentrations of creatinine were measured by the Jaffe method (Spectrophotometer U- 2000, Hitachi, Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). UFR was calculated by dividing the urine volume by the time period. The urine-to-serum osmolality ratio (U/Sosm) was calculated by dividing urine osmolality by serum osmolality. GFR was estimated from creatinine clearance (Ccr), which was calculated by the following equations: Ccr = ([Cr]U × UFR) / [Cr]S, where [Cr]U and [Cr]S are urine and serum creatinine concentrations, respectively. Osmolar clearance (Cosm) was calculated by the following equations: Cosm = (urine osmolality × UFR) / serum osmolality. CH2O was calculated by the following equations: CH2O = UFR - Cosm. Urinary excretion of sodium (UNa+V), potassium (UK+V), and chloride (UCl-V) were calculated by dividing the urine volumes of sodium, potassium, and chloride by the time period, respectively. All analyses were carried out in duplicate, except for the hematocrit measurements, which were made in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SD. One- and two-way (time × trial) repeated-measures ANOVAs were performed to test the significance between and within trials. Where a significant interaction was apparent, pairwise differences were evaluated using the Tukey post hoc procedure. The significance level was set at p < 0.05. Effect sizes (Cohen d) were calculated using the Cohen method for paired samples (Cohen, 1988). An effect size of 0.2 to < 0.5 and ≥ 0.5 to < 0.8 has been suggested to represent a small and medium treatment effect, respectively, while an effect size ≥ 0.8 represents a large treatment effect (Cohen, 1988).

Results

Pre-exercise body mass was not different between trials (68.7 ± 4.4 kg, 68.6 ± 4.8 kg, 69.0 ± 4.6 kg, and 68.5 ± 4.4 kg in the NF, VF, PF, and FF trials, respectively) and there was also no difference between trials in the pre-exercise hematocrit (45.8 ± 2.0%, 44.1 ± 1.6%, 45.0 ± 1.2%, and 45.8 ± 2.0% in the NF, VF, PF, and FF trials, respectively), hemoglobin concentration (15. 4 ± 0.7 g·dL-1, 15.0 ± 0.7 g·dL-1, 15.1 ± 0.6 g·dL-1, and 15.4 ± 0.8 g·dL-1 in the NF, VF, PF, and FF trials, respectively), and urine osmolality (949 ± 233 mOsm·kgH2O-1, 955 ± 123 mOsm·kgH2O-1, 956 ± 269 mOsm·kgH2O-1, and 931 ± 230 mOsm·kgH2O-1 in the NF, VF, PF, and FF trials, respectively), suggesting that subjects began each trial in a similar physiological state.

Fluid balance

During the VF trial, subjects ingested 719 ± 240 ml of fluid and the overall range was from 299 to 1039 ml; the volume of fluid ingested was 1.1 ± 0.4% of body mass. Consuming different volumes of fluid during exercise resulted in the graded magnitude of body mass loss. Body mass loss was 1.5 ± 0.2 kg or 2.2 ± 0.2% of body mass, 0.8 ± 0.1 kg or 1.1 ± 0.5% of body mass, 0.8 ± 0.1 kg or 1.1 ± 0.2% of body mass, and 0.0 ± 0.1 kg or 0.1 ± 0.2% of body mass in the NF, VF, PF, and FF trials, respectively. Total sweat loss was similar between trials and averaged about 2% of body mass; total sweat loss was 1.5 ± 0.1 kg or 2.1 ± 0.2% of body mass, 1.4 ± 0.1 kg or 2.1 ± 0.2% of body mass, 1.4 ± 0.1 kg or 2.0 ± 0.2% of body mass, and 1.3 ± 0.1 kg or 2.0 ± 0.2% of body mass in the NF, VF, PF, and FF trials, respectively.

Renal response

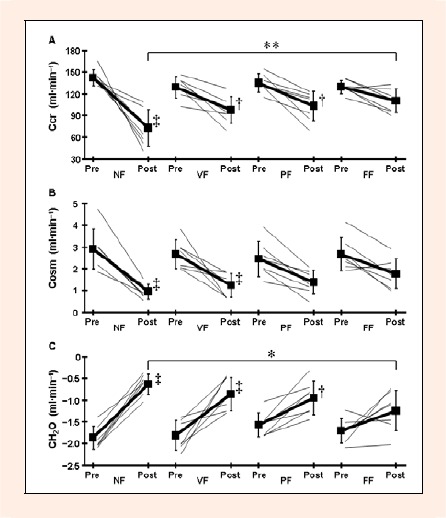

Ccr at post- exercise was significantly lower in the NF trial than in the FF trial (p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.74; Figure 1A). There was a significant decrease in Ccr during exercise in the NF (p < 0.01, Cohen d = 3.51), VF (p < 0.05, Cohen d = 1.88), and PF (p < 0.05, Cohen d = 1.91) trials. Although there was no significant difference in Ccr at post-exercise compared with pre-exercise, strong effect sizes were found in the FF trial (p = 0.419, Cohen d = 1. 43). Although no statistical difference between trials was apparent in Cosm (p = 0.176; Figure 1B), strong effect sizes were found in Cosm at post- exercise between the NF and FF trials (p = 0.336, Cohen d = 1.54). Cosm during exercise decreased significantly in the NF (p < 0.01, Cohen d = 2.88) and VF (p < 0.01, Cohen d = 2.39) trials. There was a tendency for Cosm to be decreased in the PF trial (p = 0.082, Cohen d = 1.55). There was a significant difference between the NF and FF trials in CH2O at post-exercise (p < 0.05, Cohen d = 1.64; Figure 1C). CH2O during exercise increased significantly in the NF (p < 0.01, Cohen d = 4.82), VF (p < 0.01, Cohen d = 2.66), and PF (p < 0.05, Cohen d = 1.83) trials. There was no significant difference between trials in UFR (p = 0. 764), U/Sosm (p = 0.381), UNa+V (p = 0.576), UK+V (p = 0.276), and UCl-V (p = 0.932) at post- exercise (Table 1). UFR (p < 0.05, Cohen d = 0.96) and UNa+V (p < 0.05, Cohen d = 1.45) during exercise decreased significantly in the NF trial. There was no statistical difference in urine osmolality between trials (p = 0.540); urine osmolality at post-exercise were 936 ± 100 mOsm·kgH2O-1, 983 ± 50 mOsm·kgH2O-1, 959 ± 104 mOsm·kgH2O-1, and 1028 ± 150 mOsm·kgH2O-1 in the NF, VF, PF, and FF trials, respectively.

Figure 1.

Creatinine clearance (Ccr; A), osmolar clearance (Cosm; B), and free water clearance (CH2O; C) during exercise. Thick lines are mean ± SD for 7 subjects and thin lines are individual subjects. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference between the NF and FF trials. †p < 0.05 and ‡p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference from pre-exercise.

Table 1.

Urine flow rate, urine to serum osmolality ratio, and urinary excretion of electrolytes during exercise. Values are mean (SD) for 7 subjects.

| NF | VF | PF | FF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| UFR (ml·min–1) | ||||

| Pre | 1.04 (.77) | .85 (.35) | .88 (.61) | .95 (.67) |

| Post | .29 (.11) * | .36 (.16) | .42 (.17) | .51 (.23) |

| U/Sosm | ||||

| Pre | 3.3 (.8) | 3.3 (.4) | 3.3 (.9) | 3.2 (.8) |

| Post | 3.2 (.3) | 3.4 (.1) | 3.3 (.4) | 3.6 (.5) |

| UNa+V (μmol·min–1) | ||||

| Pre | 179 (73) | 175 (117) | 162 (85) | 152 (41) |

| Post | 59 (39) * | 72 (45) | 80 (68) | 88 (71) |

| UK+V (μmol·min–1) | ||||

| Pre | 44 (22) | 38 (11) | 34 (18) | 38 (14) |

| Post | 38 (14) | 45 (24) | 55 (29) | 55 (31) |

| UCl−V (μmol·min–1) | ||||

| Pre | 161 (57) | 161 (94) | 154 (77) | 183 (151) |

| Post | 73 (46) | 97 (55) | 99 (63) | 113 (73) |

UFR, urine flow rate; U/Sosm, urine to serum osmolality ratio; UNa+V, urinary excretion of sodium; UK+V, urinary excretion of potassium; UCl−V, urinary excretion of chloride.

* p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference from pre-exercise.

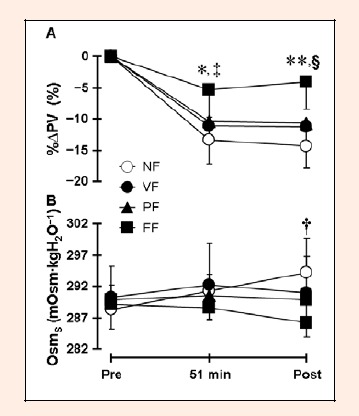

%∆PV, serum osmolality, and serum electrolyte responses

%∆PV was significantly higher at 51 min of exercise (NF vs. FF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.40; VF vs. FF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.26; PF vs. FF: p < 0.05, Cohen d = 1.04) and post-exercise (NF vs. FF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.82; VF vs. FF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.39; PF vs. FF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.28) in the FF trial than in other trials (Figure 2A). There was a significant decrease in %∆PV at 51 min of exercise in all trials (NF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 5.09; FF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 7.99; PF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 7.16; FF: p < 0.05, Cohen d = 1.77) and at post-exercise in the NF, VF, and PF trials (NF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 5.78; FF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 5.84; PF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 5.51). Serum osmolality at post-exercise was significantly lower in the FF trial than in the NF trial (p < 0.05, Cohen d = 1.49; Figure 2B). There was a significant difference between the NF and FF trials in serum sodium (p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.59) and chloride (p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.35) concentrations at post-exercise (Table 2). Serum sodium concentration during exercise increased significantly in the NF trial (p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.31). Serum potassium concentration increased significantly during exercise in the NF (p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.62) and VF (p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.44) trials (Table 2).

Figure 2.

Percentage change in plasma volume (%∆PV; A) and serum osmolality (OsmS; B) during exercise. Values are mean ± SD for 7 subjects. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference between the FF and other trials. † p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference between the NF and FF trials. ‡ p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference from pre-exercise in all trials. § p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference from pre-exercise in the NF, VF, and PF trials.

Table 2.

Serum electrolyte concentrations, body temperature, and heart rate during exercise. Values are mean (SD) for 7 subjects.

| NF | VF | PF | FF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum sodium (mmol·L-1) | ||||

| Pre | 138 (2) | 139 (2) | 139 (3) | 138 (1) |

| Post | 142 (2) § | 139 (2) | 139 (2) | 138 (1) † |

| Serum potassium (mmol·L-1) | ||||

| Pre | 3.5 (0.2) | 3.6 (0.3) | 3.6 (0.2) | 3.6 (0.2) |

| Post | 4.1 (0.3) § | 4.2 (0.3) § | 4.0 (0.2) | 4.0 (0.3) |

| Serum chloride (mmol·L-1) | ||||

| Pre | 104 (1) | 104 (2) | 104 (1) | 104 (2) |

| Post | 106 (2) | 103 (2) | 103 (1) | 102 (2) † |

| Tre (°C) | ||||

| Rest | 37.0 (0.2) | 37.0 (0.2) | 37.0 (0.2) | 36.9 (0.2) |

| End of exercise | 38.8 (0.3) | 38.3 (0.3) † | 38.2 (0.2) † | 37.9 (0.2) † |

| Tsk (°C) | ||||

| Rest | 33.7 (0.5) | 33.6 (0.7) | 33.5 (0.6) | 33.5 (0.6) |

| End of exercise | 34.9 (1.0) | 34.9 (0.9) | 34.4 (0.8) | 34.4 (0.9) |

| HR (beats·min-1) | ||||

| Rest | 83 (5) | 84 (5) | 88 (5) | 90 (6) |

| End of exercise | 181 (9) | 167 (8) * | 164 (10) † | 154 (11) †‡ |

Tre, rectal temperature; Tsk, mean skin temperature; HR, heart rate.

* p < 0.05 and

† p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference from the NF trial.

‡ p < 0.05 denotes a significant difference from the VF trial.

§ p < 0.01 denotes a significant difference from pre-exercise.

Body temperature and HR responses

As shown in Table 2, Tre at the end of exercise was significantly higher in the NF trial than in other trials (NF vs. VF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.39; NF vs. PF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.55; NF vs. FF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 2.44). No significant difference was observed between trials in Tsk during exercise (p = 0.930). At the end of exercise, HR was significantly higher in the NF trial than in other trials (NF vs. VF: p < 0.05, Cohen d = 1.12; NF vs. PF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1. 29; NF vs. FF: p < 0.01, Cohen d = 1.95) and in the VF trial than in the FF trial (p < 0.05, Cohen d = 1.03).

Discussion

The aims of this study were to investigate the effect of drink volume on urine concentrating ability and to compare the effect of voluntary fluid ingestion and imposed fluid ingestion on renal response to exercise when performing prolonged heavy exercise in a hot environment at low levels of dehydration. The results of the present study demonstrated no statistical change in urinary indices of renal function during exercise in the FF trial (Figure 1 and Table 1). These observations suggest that full fluid ingestion equivalent to body mass loss may be effective in attenuating the decline in urine concentrating ability. In contrast, significant decreases in Ccr and Cosm and a significant increase in CH2O were observed during exercise in the VF trial (Figure 1). These data indicate that voluntary fluid ingestion may not be sufficient to attenuate the decline in urine concentrating ability compared with full fluid ingestion. However, the sample size for the present study might have been too small that might result in no significant difference within and between trials in any urinary indices of renal function. Additionally, pre-exercise UFR was 9-18% higher in the NF trial than in other trials and this might affect the difference in the renal handling of sodium and water during exercise between trials.

Previous studies have concluded that the combination of reductions in UFR and GFR and the elevation in CH2O during exercise largely reflect the decline in urine concentrating ability (Freund et al., 1991; Kachadorian and Johnson, 1970; Refsum and Strømme, 1975; 1978; Wade and Claybaugh, 1980). In particular, one of the major roles of declining urine concentrating ability during exercise is to decrease the GFR (Freund et al., 1991; Melin et al., 1997; Refsum and Strømme, 1978; Wade et al., 1989). Mostly, this causes the decrease in Cosm (Freund et al., 1991; Kachadorian and Johnson, 1970; Melin et al., 2001; Refsum and Strømme, 1978; Wade and Claybaugh, 1980), which reflects the decrease in sodium delivery to the ascending loop of Henle due to the increase in the proximal tubular sodium reabsorption (Wade et al., 1989). If sodium delivery to the ascending loop of Henle decreases, the medullary interstitium osmolality decreases, resulting in the reduction in the medullary concentration gradient (Wade et al., 1989; Zambraski, 1990). In these conditions, urine concentrating ability is limited, even though the plasma arginine vasopressin concentration (not measured in this study) increases significantly compared with the pre-exercise level (Freund et al., 1991; Melin et al., 2001; Wade and Claybaugh, 1980; Wade et al., 1989). In the present study, Ccr during exercise reduced significantly by 49%, 25%, and 24% in the NF, VF, and PF trials, respectively, but no significant change (Ccr = -15%) was apparent in the FF trial. This response suggests that GFR, as estimated by Ccr, reduced as the volume of fluid ingested decreased. Additionally, there were the significant reduction in Cosm and elevation in CH2O in proportion to decreased Ccr in the NF and VF trials. These relationships indicate that the tubular sodium reabsorption might elevate and the tubular water reabsorption might reduce as the volume of fluid ingested decreased. In general, the decrease in GFR during exercise results from the reduction in RBF, which is due to active vasoconstriction of the renal blood vessels (Poortmans, 1984; Zambraski, 1990; 2006) and is mediated by the increase in renal sympathetic nerve activity (Poortmans, 1984; Zambraski, 1990; 2006). Radigan and Robinson, 1949 have reported that during exercise, the decrease in RBF is somewhat greater if subjects are exercising in a hot environment and/or are dehydrated. In addition, Freund et al., 1991 have reported that GFR reduces during moderate (60%VO2max) to heavy (>80%VO2max) exercise, whereas it is either elevated or maintained during light (25%VO2max) to moderate (40%VO2max) exercise. Thus, in this study, the increased sympathetic nerve activity due to performing heavy exercise in a hot environment would result in the significant decrease in GFR in the NF, VF, and PF trials.

During the NF trial, exercise resulted in significant decreases in UFR, Ccr, and Cosm and the significant increase in CH2O, clearly demonstrating the decline in urine concentrating ability. During the VF trial, although there was a substantial interindividual variation in the volume of fluid ingested (range 299 to 1039 ml), there was no large interindividual variability in urine concentrating ability. In this trial, subjects ingested 719 ± 240 ml of fluid that it was almost identical to the volume of fluid ingested in the PF trial. This response compares well with previous studies which reported the volume of fluid ingested was about 50% of body mass loss when subjects ingested fluid voluntarily during exercise in a hot environment (Hubbard et al., 1984). Although decreased UFR was not significantly different in the VF trial, given that there were significant decreases in Ccr and Cosm and the significant increase in CH2O, this trial would decline urine concentrating ability during exercise. Besides, although decreased UFR and Cosm during exercise were not significant in the PF trial, given that the significant decrease in Ccr and increase in CH2O were observed, it is possible to decline urine concentrating ability in this trial. In contrast, there were no significant changes in UFR, Ccr, Cosm, and CH2O during exercise in the FF trial, clearly indicating no change in urine concentrating ability. However, these results might have been due to a small sample size for this study, given that strong effect sizes (Cohen d = 1. 43) were apparent in Ccr between pre- and post-exercise in the FF trial. Based on the results of this study, it has been demonstrated that full fluid ingestion equivalent to body mass loss can attenuate the decline in urine concentrating ability during prolonged heavy exercise in a hot environment at low levels of dehydration. Moreover, this study demonstrates that voluntary fluid ingestion is ineffective for maintaining urine concentrating ability compared with imposed fluid ingestion equivalent to body mass loss. On the other hand, renal sympathetic nerve activity, arginine vasopressin, aldosterone, atrial natriuretic peptide, and nitric oxide were not measured in the present study. Thus, the extent of its influence was not evaluated. A response of the kidneys accompanying fluid ingestion during exercise may be complex and influenced by multiple factors, involving exercise intensity, the dehydration level and the rehydration beverage. It has been known that heavy exercise, especially combined with dehydration and heat stress, could cause acute renal failure accompanied by exertional rhabdomyolysis (Clarkson, 2007), and fluid ingestion sufficient to maintain adequate urine excretion is critical to prevent acute renal failure during exercise (Cianflocco, 1992). Further investigations are therefore needed to clarify the interrelationships between fluid ingestion and renal function during exercise in a hot environment at dehydration.

In agreement with previous studies during exercise in a hot environment (Gonzalez-Alonso et al., 1998; Montain and Coyle, 1992), we observed increases in core temperature and HR and the decrease in %ΔPV as body mass loss increased. During exercise with progressive dehydration, Nielsen, 1974 has demonstrated that fluid ingestion enables humans to attenuate the increase in core temperature resulting from maintained serum osmolality. In support of this observation, there was a relatively lower serum osmolality as the volume of fluid ingested increased in this study. Additionally, ingestion of a cold beverage during exercise is known to attenuate the increase in core temperature (Lee et al., 2008; Mündel et al., 2006). It is thus possible in this study that a lesser increase in Tre as drink volume increased was attributed in part to the combined effect of maintained serum osmolality and consuming large volumes of cold fluid.

Conclusion

We conclude that full fluid ingestion equivalent to body mass loss has attenuated the decline in urine concentrating ability during prolonged heavy exercise in a hot environment at low levels of dehydration. This is accompanied by no statistical changes in urine excretion, GFR, Cosm, CH2O, and urinary excretion of electrolytes during exercise. In contrast, given significant reductions in GFR and Cosm and the significant elevation in CH2O during exercise, voluntary fluid ingestion does not seem to be effective in reducing the decline in urine concentrating ability under our experimental conditions.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the cooperation of all of our participants. This study was undertaken with no external financial support and there are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Biographies

Hidenori Otani

Employment

Associate Professor, Faculty of Health Care Sciences, Himeji Dokkyo University, Himeji, Japan.

Degree

PhD

Research interests

Exercise physiology, environmental physiology, sports medicine.

E-mail: hotani@himeji-du.ac.jp

Mitsuharu Kaya

Employment

Lecturer, General Education Center, Hyogo University of Health, Kobe, Japan.

Degree

PhD

Research interests

Exercise physiology, exercise biochemistry, health science

E-mail: kaya@huhs.ac.jp

Junzo Tsujita

Employment

Associate Professor, Department of Health and Sport Sciences, Hyogo College of Medicine, Nishinomiya, Japan.

Degree

BS

Research interests

Exercise physiology, sports medicine

E-mail: tsujitaj@hyo-med.ac.jp

References

- Casa D.J. (2000) National athletic trainer’s association position statement: fluid replacement for athletes. Journal of Athletic Training 35, 212-224 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castenfors J., Piscator M. (1967) Renal haemodynamics, urine flow and urinary protein excretion during exercise in supine position at different loads. Acta Medica Scandinavica Suppl. 472, 231-244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cianflocco A.J. (1992) Renal complications of exercise. Clinics in Sports Medicine 11, 437-451 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson P.M. (2007) Exertional rhabdomyolysis and acute renal failure in marathon runners. Sports Medicine 37, 361-363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988) Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2ndedition Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum [Google Scholar]

- Costill D.L., Saltin B. (1974) Factors limiting gastric emptying during rest and exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology 37, 679-683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dann E.J., Gillis S., Burstein R. (1990) Effect of fluid intake on renal function during exercise in the cold. European Journal of Applied Physiology 61, 133-137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dill D.B., Costill D.L. (1974) Calculation of percentage changes in volumes of blood, plasma, and red cells in dehydration. Journal of Applied Physiology 37, 247-248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund B.J., Shizuru E.M., Hashiro G.M., Claybaugh J.R. (1991) Hormonal, electrolyte, and renal responses to exercise are intensity dependent. Journal of Applied Physiology 70, 900-906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Alonso J., Calbet J.A., Nielsen B. (1998) Muscle blood flow is reduced with dehydration during prolonged exercise in humans. Journal of Physiology 513, 895-905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimby G. (1965) Renal clearances during prolonged supine exercise at differents loads. Journal of Applied Physiology 20, 1294-1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubbard R.W., Sandick B.L., Matthew W.T., Francesconi R.P., Sampson J.B., Durkot M.J., Maller O., Engell D.B. (1984) Voluntary dehydration and alliesthesia for water. Journal of Applied Physiology 57, 868-875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kachadorian W.A., Johnson R.E. (1970) Renal responses to various rates of exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology 28, 748-752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J.K.W., Shirreffs S.M., Maughan R.J. (2008) Cold drink ingestion improves exercise endurance capacity in the heat. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 40, 1637-1644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallié J. P., Ait-Djafer Z., Saunders C., Pierrat A., Caira M.V., Courroy O., Panescu V., Perrin P. (2002) Renal handling of salt and water in humans during exercise with or without hydration. European Journal of Applied Physiology 86, 196-202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maughan R.J., Shirreffs S.M. (2008) Development of individual hydration strategies for athletes. International Journal of Sport Nutrition and Exercise Metabolism 18, 457-472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melin B., Jimenez C., Savourey G., Bittel J., Cottet-Emard J.M., Pequignot J.M., Allevard A.M., Gharib C. (1997) Effects of hydration state on hormonal and renal responses during moderate exercise in the heat. European Journal of Applied Physiology 76, 320-327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melin B., Koulmann N., Jimenez C., Savourey G., Launay J.C., Cottet-Emard J.M., Pequignot J.M., Allevard A.M., and Gharib C. (2001) Comparison of passive heat or exercise-induced dehydration on renal water and electrolyte excretion: the hormonal involvement. European Journal of Applied Physiology 85, 250-258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montain S.J., Coyle E.F. (1992) Influence of graded dehydration on hyperthermia and cardiovascular drift during exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology 73, 1340-1350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mündel T., King J., Collacott E., Jones D.A. (2006) Drink temperature influences fluid intake and endurance capacity in men during exercise in a hot, dry environment. Experimental Physiology 91, 925-933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen B. (1974) Effects of changes in plasma volume and osmolarity on thermoregulation during exercise. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica 90, 725-730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noakes T., Martin D. (2002) IMMDA-AIMS advisory statement on guidelines for fluid replacement during marathon running. New Studies in Athletics 17, 15-24 [Google Scholar]

- Poortmans J.R. (1984) Exercise and renal function. Sports Medicine 1, 125-153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radigan L.R., Robinson S. (1949) Effects of environmental heat stress and exercise on renal blood flow and filtration rate. Journal of Applied Physiology 2, 185-191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanathan N.L. (1964) A new weighting system for mean surface temperature of the human body. Journal of Applied Physiology 19, 531-533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refsum H.E., Strømme S.B. (1975) Relationship between urine flow, glomerular filtration, and urine solute concentrations during prolonged heavy exercise. Scandinavia Journal of Clinical Laboratory Investigation 35, 775-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Refsum H.E., Strømme S.B. (1978) Renal osmol clearance during prolonged heavy exercise. Scandinavia Journal of Clinical Laboratory Investigation 38, 19-22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehrer N.J., Wagenmakers A.J., Beckers E.J., Halliday D., Leiper J.B., Brouns F., Maughan R.J., Westerterp K., Saris W.H. (1992) Gastric emptying, absorption, and carbohydrate oxidation during prolonged exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology 72, 468-475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawka M.N., Burke L.M., Eichner E.R., Maughan R.J., Montain S.J., Stachenfeld N.S. (2007) American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand: Exercise and fluid replacement. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 39, 377-390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirreffs S.M., Armstrong L.E., Cheuvront S.N. (2004) Fluid and electrolyte needs for preparation and recovery from training and competition. Journal of Sports Science 22, 57-63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirreffs S.M., Taylor A.J., Leiper J.B., Maughan R.J. (1996) Post-exercise rehydration in man: effects of volume consumed and drink sodium content. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise 28, 1260-1271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J.H., Robinson S., Pearcy M. (1952) Rend responses to exercise, heat and dehydration. Journal of Applied Physiology 4, 659-665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vist G.E., Maughan R.J. (1995) The effect of osmolality and carbohydrate content on the rate of gastric emptying of liquids in man. Journal of Physiology 486, 523-531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade C.E., Claybaugh J.R. (1980) Plasma renin activity, vasopressin concentration, and urinary excretory responses to exercise in men. Journal of Applied Physiology 49, 930-936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wade C.E., Freund B.J., Claybaugh J.R. (1989) Fluid and electrolyte homeostasis during and following exercise: hormonal and non-hormonal factors. In: Hormonal regulation of fluid and electrolytes. Environmental effects. Eds: Claybaugh J.R., Wade C.E.New York: Plenum Press; 1-44 [Google Scholar]

- Zambraski E.J. (1990) Renal regulation of fluid homeostasis during exercise. In: Fluid homeostasis during exercise. Eds: Gisolfi C.V., Lamb D.Carmel: Benchmark; 247-280 [Google Scholar]

- Zambraski E.J. (2006) The renal system. In: ACSM’s advanced exercise physiology. Ed: Tipton C.M.Baltimore: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 521-531 [Google Scholar]