Abstract

A new practical route to chaetomellic acid A (ACA), based on the copper catalysed radical cyclization (RC) of (Z)-3-(2,2-dichloropropanoyl)-2-pentadecylidene-1,3-thiazinane, is described. Remarkably, the process entailed: i) a one-pot preparation of the intermediate N-α-perchloroacyl-2-(Z)-alkyliden-1,3-thiazinanes starting from N-(3-hydroxypropyl)palmitamide, ii) a two step smooth transformation of the RC products into ACA and iii) only one intermediate chromatographic purification step. The method offers a versatile approach to the preparation of ACA analogues, through the synthesis of an intermediate maleic anhydride with a vinylic group at the end of the aliphatic tail, a function that can be transformed through a thiol-ene coupling. Serendipitously, the disodium salt of 2-(9-(butylthio)nonyl)-3-methylmaleic acid, that we prepared as a representative sulfurated ACA analogue, was a more competent FTase inhibitor than ACA. This behaviour was analysed by a molecular docking study.

Keywords: Chaetomellic acid A, Farnesyl pyrophosphate, FTase inhibitors, Modelling studies, Radical cyclization

1. Introduction

Prenylation of proteins with polyisoprenoids is an important post-translational modification, which plays a major role in cell proliferation of both normal and cancerous cells.1 Proteins, which undergo prenylation, are all characterized by a CAAX motif at their carboxy terminus, where C is a cysteine residue, A is any aliphatic amino acid, and X could be variable (usually alanine, serine, methionine, or glutamine).1,2 Prenylation can occur via the covalent attachment of either a 15-carbon farnesyl moiety or a 20-carbon geranylgeranyl moiety to the cysteine of CAAX motif-containing proteins, the process being catalysed by farnesyltransferase (FTase) or geranylgeranyltransferase (GGTase) enzymes.1d Geranylgeranylation is found to be responsible for the prenylation of 80–90% of prenylated proteins;3 whereas, lamins A and B,1b,c,4 the fungal mating factor,2a γ-transducin,2e,f the γ subunit of heterotrimeric G-proteins4 and Ras-proteins2c,4 are farnesylated.

Farnesylation is required for the subcellular localization and transformation activity of the oncogenic variants of Ras.1a,2c,5 Consequently, the inhibition of farnesylation prevents localization of these proteins at the cell membrane, thereby prohibiting cell transformation. For this reason, the development of farnesyltransferase (FTase) inhibitors have emerged as novel class of pharmaceutical agents in noncytotoxic anticancer therapy.1a,6 Enzymatic and crystallographic techniques have explained the mechanism of FTase catalysis, demonstrating that farnesylation proceeds via an ordered mechanism with farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) binding first, followed by the CAAX moiety of the Ras-protein and then by the farnesyl transfer to the cysteine residue C.1d,6,7

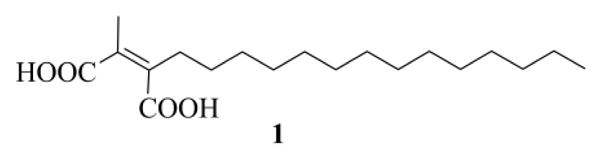

Inhibitors design is largely based on the CAAX motif, the farnesyl moiety, or both (in the latter case inhibitors mimic the transition state).1a,d,6a,8 Also several natural products are able to inhibit the FTase.1a,9 These substances have been generally identified through screening program of microbial natural products.9 It was just during one of these screening tests that a Merck's team isolated, from extracts of the coelomycete Chaetomella acutiseta, chaetomellic acid A (ACA) 1 (Figure 1),10 a dicarboxylic acid that inhibited, in its dianionic form 2, the recombinant human FTase, with an IC50 value of 55 nM.11 Chaetomellic acid A (1) has a high tendency to cyclize and, in fact, it was isolated as anhydride 3.10a The cyclic form, however, is unstable under mild basic conditions (pH=7.5) and is readily hydrolysed to the dicarboxylate anion 2, the biologically active component (Scheme 1).10a

Figure 1.

Chaetomellic acid A (1).

Scheme 1.

pH dependent equilibrium between the active dianionic open form 2 and the anhydride chaetomellic A (3).

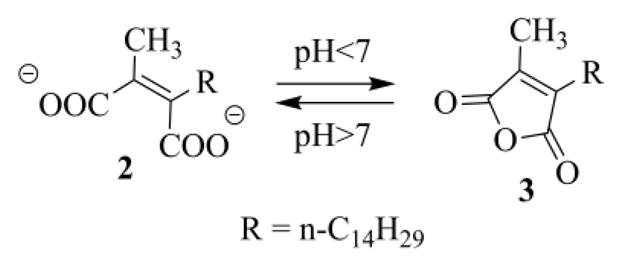

FTase activity of the diacid anion of 1 is noncompetitive towards the acceptor peptide Ras, but is highly competitive with respect to farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP).11 This may be explained by the structural similarity between the dicarboxylate anion 2 and FPP, since both possess a hydrophilic head group bound to a hydrophobic tail (Figure 2).10a The maleate unit aligns well with the corresponding diphosphate moiety, since the negatively charged oxygen atoms can achieve a spacing within 0.1 Å,12 while the difference in the distance between the carboxyl carbons and between the phosphorus atoms is only 0.4 Å.10a The flexible nature of the aliphatic chain, instead, permits it to fill the same space, as the hydrophobic end of FPP, upon binding to the enzyme.

Figure 2.

Structural similarity between the dianionic form of chaetomellic acid A 2 and farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP).

Unfortunately 1 did not inhibit Ras processing in ras-transformed NIH3T3, perhaps because of poor penetration in these cells or its untimely enzymatic transformation.11 However, Bach, on studying the capacity of branch-specific inhibitors of the cytosolic isoprenoid pathway - downstream from mevalonic acid - to block cell cycle progression in tobacco BY-2 cells, observed that ACA (1) behaved like a true cell cycle inhibitor, in that it led to a specific arrest in the cell cycle.13 Vederas, instead, in an effort to characterize the FPP binding site of rubber transferase showed that 1 is able to inhibit, in vitro, rubber biosynthesis promoted by rubber transferase from Hevea Brasiliensis.14 Besides, the same author found that 1 was also able to reduce the activity of the PBP1b (penicillin-binding protein 1b), albeit with modest potency.15 Recently, Sabbatini has shown that the inhibition of the Ras/ERK1/2 pathway by 1 resulted in a beneficial effect on acute ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats, preserving either renal function and histology.16 These results were the consequence of the reduced apoptosis/necrosis of renal cells observed after oxidative stress in rats, as also shown both in human tubular and endothelial cells in culture. ACA (1) selectively inhibited the membrane-bound Ha-Ras (a pro-apoptotic pathway), since it did not alter the membrane-bound Ki-Ras (an antiapoptotic pathway), nor different prenylated intracellular proteins like Rab.16 Similar results have been also described in an experimental murine model of ischemic stroke (exocytoxic lesion), in which ACA (1) administration increased the intracellular concentration of inactive Ha-Ras, significantly reducing the production of superoxide anion and the volume of cerebral necrotic tissue, following the improved survival of hypoxic neuronal cells.17

Because of its biological activity10a,11,13–17 and potential employment as therapeutic agents,18 chaetomellic acid A (1) has been the subject of considerable synthetic efforts. In general, the synthesis of anhydride 3 has been targeted since this compound is easier to manipulate/isolate than diacid 1. The synthetic strategies investigated can be roughly grouped into two general categories: i) alkylation of maleic precursors18a,19 and ii) assembly of the pivotal 1,4-dicarbonyl group.20

Singh prepared a number of analogues of 1, characterized by a modified hydrophobic tail – having one C=C double bond or a shorter chain length – or by the replacement of the methyl in the polar head with H, hydroxymethyl or larger groups.20c No modified ACA, however, showed more potent inhibition than 2 against the recombinant human FTase. Also the groups of Vederas and Poulter synthesized some ACA analogues, namely those with R = n-C12H25, farnesyl, or geranylgeranyl.19a These substances were evaluated for inhibition of the yeast FTase and, unlike Singh's observations, the compounds with the shorter tail showed greater activity than ACA (1).

In spite of the variety of known methods, all of the reported synthetic procedures to 3 suffer from one or more of the following disadvantages: i) low yields, ii) costly reagents, iii) unstable precursors and/or reactants, iv) harmful solvents, v) unwieldy protocols, or vi) lack of versatility.

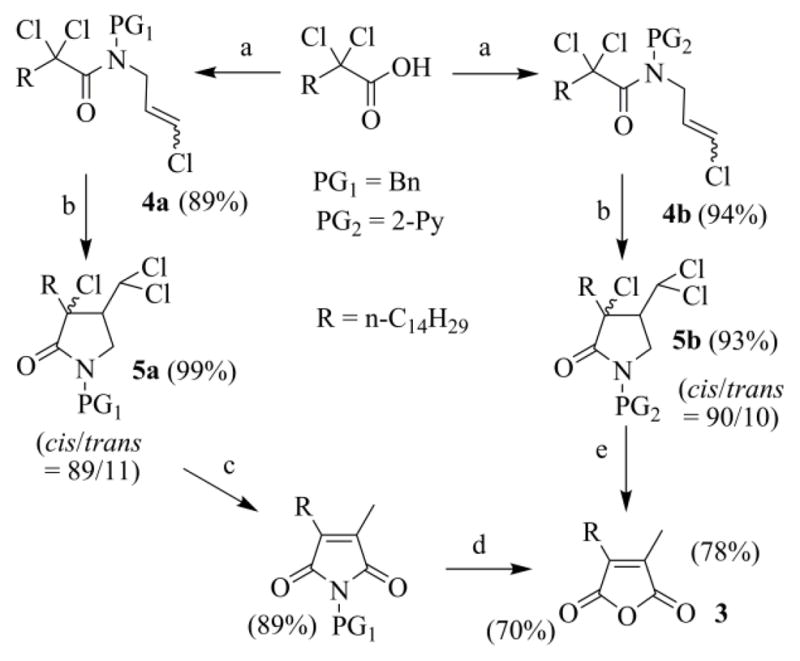

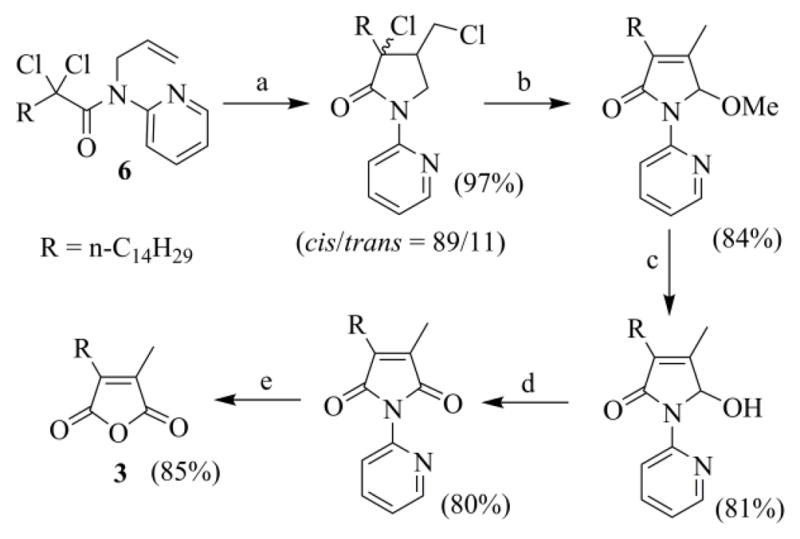

We tried to overpass these disadvantages and a few years ago devised an interesting way to prepare 3, where the anhydride moiety was constructed through the atom-transfer radical cyclization (ATRC) of N-(benzyl)- or better N-(2-pyridyl)-N-(3-chloro-2-propenylamino)-2,2-dichlorohexadecanamides 4, followed by the functional rearrangement (FR) of the intermediate trichloro γ-lactams 5 (Scheme 2).21a,b The same strategy was then applied to N-(2-pyridyl)-N-allyl-2,2-dichlorohexadecanamide 6 (Scheme 3), the preparation of which uses a more accessible secondary allylamine. The lack of the Cl atom in the allyl moiety, in this case, called for the introduction of an oxidative extra step in the synthetic route.21c

Scheme 2.

(a) 1) (COCl)2, CH2Cl2, DMF, 23 °C, 2 h; 2) N-benzyl-3-Cl-2-propenylamine (PG1 = Bn) or 2-(3-chloro-2-propenylamino)pyridine (PG2 = 2-Py), Py, 23 °C, 1 h. (b) CuCl-TMEDA, CH3CN, argon, 60 °C, 20 h. (c) 1) Na0, CH3OH/diethyl ether, 25 °C, 20 h; 2) H+/H2O. (d) 1) KOH, CH3OH/THF, reflux, 2 h; 2) H+/H2O. (e) 1) Na0, CH3OH/diethyl ether, 25 °C, 20 h; 2) H2SO4 4 N, 110 °C, 2 h.

Scheme 3.

(a) CuCl-TMEDA, toluene, argon, 60 °C, 24 h. (b) Na0, toluene/MeOH, 25 °C, 24 h. (c) H2SO4/H2O, 110 °C, 3 h. (d) One-pot procedure: 1) Na0, toluene/MeOH, 25 °C, 24 h; 2) H2SO4/H2O, 110 °C, 3 h. (e) MnO2, CH2Cl2, 25 °C, 20 h. (f) H2SO4/H2O, 110 °C, 4 h.

Both of these procedures have the same two important drawbacks. The former is the use of α-perchlorocarboxylic acids (these starting materials are not very easy to prepare), while the latter is the lack of a perfect control of the ATRC stereoselectivity. This is a critical event for the economy of the process since the FR reaction is viable only in the case of cis-lactams,21b,22 and the cis/trans ratio of the γ-lactams, delivered by the ATRC step, is acceptable only when these lactams carry a bulky substituent at C-3 and a chloro- or a dichloro-methyl group at C-4. In fact, when we tested the viability of the complementary strategy, in which the methyl substituent is introduced through the acid reagent while the long aliphatic chain is added through the allylamino moiety, the stereoselectivity of the ATRC lactam was disappointing (the dichloro-γ-lactam from the cyclization of N-benzyl-N-[(E)-2-hexenyl)]-2,2-dichloropropanamide was recovered as a 66/34 cis/trans mixture of four diastereomers).21c Since a practical route to functionalized 2,2-dichloro acids appeared impracticable, the ATRC-FR approach to chaetomellic acid A analogues lost any appeal.

Now as part of a project about the acute kidney injury (AKI) from ischaemia-reperfusion in rat, we were asked to develop a versatile way to chaetomellic acid A (1), and analogues, for the prevention of the ischemic damage, through the inhibition of the pathway Ras/ERK1/2. Here we describe the new synthetic method and the serendipitous discovery of an ACA analogue having a higher affinity for the FTase than the natural product.

2. Results and discussion

2.1. Synthesis of ACA

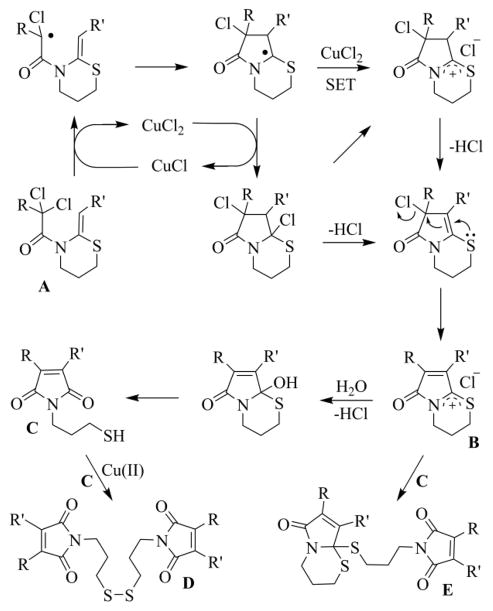

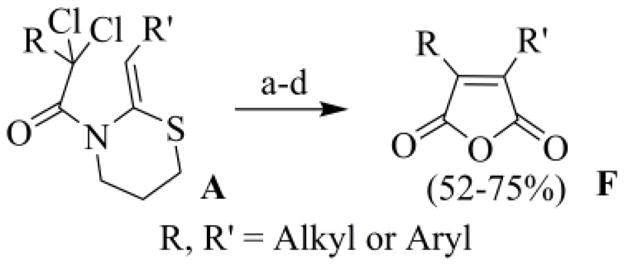

To solve the intrinsic problems of the ATRC-FR paths to maleic anhydrides, we have recently studied the copper catalyzed radical cyclization (RC) of N-α-perchloroacyl cyclic ketene-N,X(X = O, NR, S)-acetals. The RC of N-α-perchloroacyl-2-(Z)-alkyliden-1,3-thiazinane A was shown to be, by far, the most efficient and selective reaction (Scheme 4).23 Invariably the catalytic cycle begins with the formation of a carbamoyl methyl radical, which leads to a cascade of reactions, including a radical polar crossover step, culminating in the formation of the maleimide nucleus (D and E), or of a direct precursor of it (E) (Scheme 4). The typical large prevalence of E over D likely means that the quenching of the acyliminium cation B by C is kinetically favoured in comparison with the oxidative homocoupling of C.

Scheme 4.

Possible mechanism for the RC of N-α-perchloroacyl six membered cyclic ketene-N, S-acetals A.

The disulfide D and thioacetal E, without being isolated, were subjected to an oxidative treatment to reveal the C=O group, masked as an S,S-acetal in E. The crude products from this step were then hydrolyzed according to Argade's method,19c affording the expected anhydrides F in a more than acceptable overall yield from the starting enamides A (Scheme 5).23b

Scheme 5.

Preparation of the 3,4-disubstituted-2,5-furandiones: (a) CuCl (5 mol%), TMEDA (10 mol%), CH3CN, Na2CO3, argon, 17 h, 30 °C; (b) silica-sulfuric acid, NaNO3, SiO2/H2O 3:2, CH2Cl2, 45 °C, 40 h; (c) KOH, CH3OH-THF, reflux 2 h; (d) HCl (10 %), r.t..

The new process bypasses the stereoselectivity problem of the ATRC step in the ATRC-FR method. Moreover its versatility is no longer reliant on the somewhat exotic functionalized 2,2-dichloroacyl chlorides, but can rely on the more accessible functionalized carboxylic acids. In addition we have recently developed an easy, cheap and efficient preparation of short-chain α-perchloroacyl chlorides, from α-perhalogenation of the corresponding unfunctionalized acyl halides with Cl2, using tetraalkylammonium chloride as a catalyst.24

However, the new method is still unpractical and unsuited for large-scale preparation. The starting enamides A are secured through acylation of 2-alkyl-5,6-dihydro-4H-1,3-thiazines, substrates that can be obtained following a literature procedure,25 involving thionation of N-(3-hydroxypropyl)-carboxyamides with the Lawesson's reagent (LR). In our hands the preparation of 5,6-dihydro-4H-1,3-thiazines was too expensive and characterized by a susceptible and too lengthy work-up; furthermore LR has also a repulsive high equivalent weight. In addition, the deprotection of the thioacetal group in E (following the method of Hajipour)26 was exceedingly long (around 2 d) and used a large amount of solid reagents (Scheme 5, step c).23

After a search of literature, looking for a more appropriate method for thionation of amides, our attention was attracted to the use of cheap Berzelius reagent (P4S10). This reagent is characterized by an attractive low equivalent weight,27 which, when combined with hexamethyldisiloxane (HMDO), issues better - or comparable - results than LR.27,28 The combination of P4S10-HMDO is known as the Curphey reagent (CR). HMDO has the function to scavenge the reactive electrophilic polythiophosphates (thionation by-products), before they cause any side reaction.

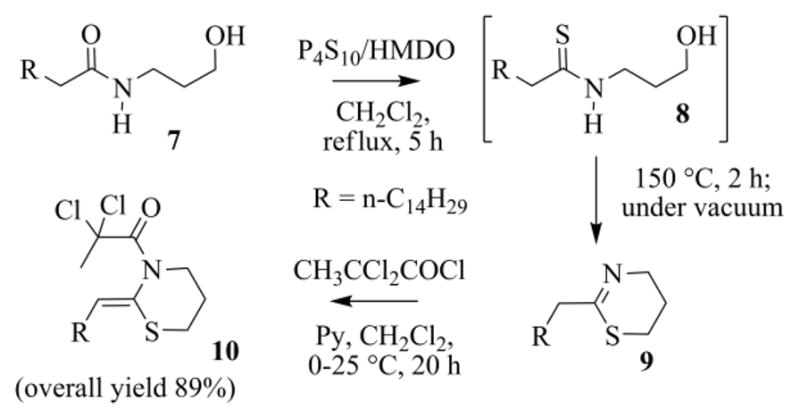

Thionation of 7 was carried out with the CR in CH2Cl2 at reflux (Scheme 6). For an effective transformation, however, the amount of water present in the reaction mixture must be kept low. As 7 is recovered by filtration from water suspensions, it is the major source of humidity. Thus it is recommended to use a dry starting hydroxyamide (e.g. re-crystallized material from diethyl ether). Otherwise the H2S, which comes from hydrolytic processes, causes the [N,O]-migration of the thioacyl or acyl moieties.29 The problems associated with the presence of H2O can be also downsized by working in open vessels, since the volatile H2S has the chance to escape from the reaction mixture through the condenser.

Scheme 6.

Preparation of the N-2,2-dichloropropanoyl ketene-N,S-acetal 10.

Astonishingly the MS-spectra of the unique peak, observed during the GC-MS analysis of the final reaction mixture, was peculiar of the cyclic thioimidate 9 and not of the expected hydroxythioamide 8. Soon we realized that this was indeed an instrumental fake. We speculated that the thermal stress, to which 8 was subjected in the injection chamber, resulted in cyclization to 9.30 In fact on heating at 150 °C (2–3 h), under vacuum and a slight flow of argon, the crude reaction mixture from the thionation step, after evaporation of the volatiles, gave 9, also free of the silylated side-products. The intermediate thioimidate is, however, somewhat sensitive to hydrolysis, and cannot be chromatographed on silica-gel. But it was indeed quite clean and was acylated, as such, using 2,2-dichloropropanoyl chloride, affording the N-acyl-ketene-N,S-acetal 10 (a relatively robust molecule, that was purified by chromatography) in high yield (80–90%) (Scheme 6). Because analogues of N-acyl-ketene-N,S-acetals typically have a Z configured C=C bond,23b the same geometry was assigned to 10, and to the other enamides we prepared in this work.

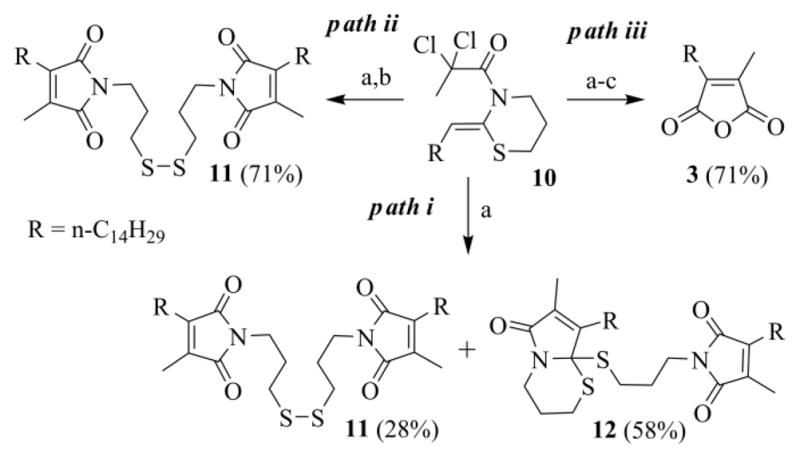

Using a reasonably pure sample of 10 (a condition that has to be maintained also with the other enamides we prepared), the radical cyclization proceeded smoothly giving, as expected, the disulfide 11 and the thioacetal 12 (Scheme 7, path i).

Scheme 7.

Reactions of the N-2,2-dichloropropanoyl ketene-N,S-acetal 10: (a) CuCl (10 mol%), TMEDA (20 mol%), CH3CN/toluene (3/2), Na2CO3, argon, 30 °C, 19–24 h; (b) KI, H2O, r.t., 24 h; (c) NaOH, THF/H2O, r. t., 12h, acidic work-up.

The delatentization of the C=O function, hidden as an S,S-acetal can be generally achieved by heavy metals coordination (such as Hg2+ or Cu2+), by alkylation or by oxidative methods.31 While we were studying a more appropriate protocol than that of Hajipour, we incidentally observed that a crude extract from the RC of 10, left on the laboratory bench for 3 weeks, contained only the symmetric dimer 11. Evidently, residual copper and air promoted the oxidative deprotection of 12 and its transformation into 11. We were unable to repeat this excellent result, but a large conversion of 12 into 11 was always experienced.

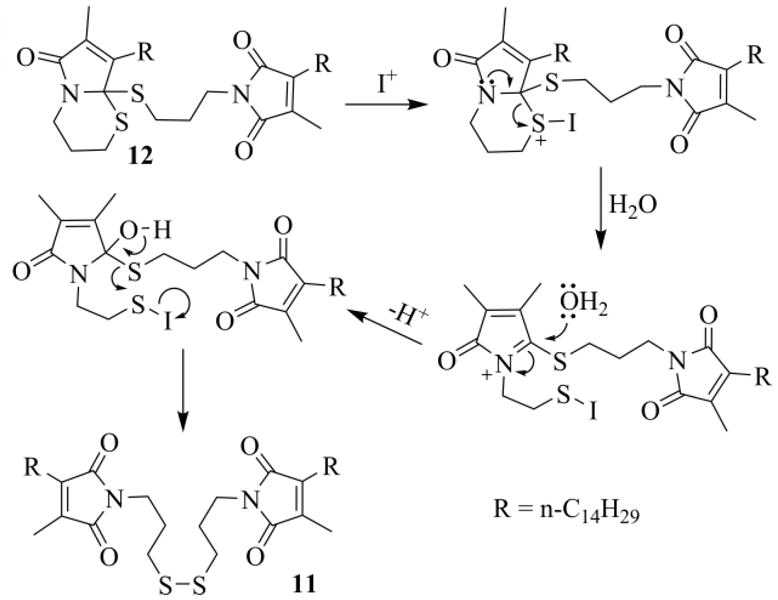

To make the deprotection of 12 reproducible and achievable in reasonable times, we considered that an oxidative method based on I2, a reagent effectively employed for the regeneration of the carbonyl group from S,S-acetals,32 could be helpful. Particularly attractive is the possibility to generate iodine (or I+ reagents) in situ, through the oxidation of the iodide anion.33 After a number of tests, we found it convenient to add KI (100 mg/5 mmol of 10) and a few drops of water (5-10/5 mmol of 10) to the open Schlenk tube, once the RC reaction was completed (Scheme 7, path ii). A possible mechanism for the conversion of 12 into 11 is outlined in Scheme 8. The process is intramolecular, as shown in the scheme, when the “endo” sulfur is attacked, otherwise it could be intermolecular.

Scheme 8.

Possible mechanism for deprotection of the thioacetal moiety in 12.

Finally, the hydrolysis of chromatographed 11, adapting Argade's protocol, gave the targeted 3a in good yield (94%).19c More appropriately, it was possible to carry out the hydrolytic step directly on the crude extract of 11 (Scheme 7, path iii). In this way, since a purification step is spared, the process gives a higher global yield (71% against 66%).

2.2. A route for the synthesis of tailor made ACA analogues

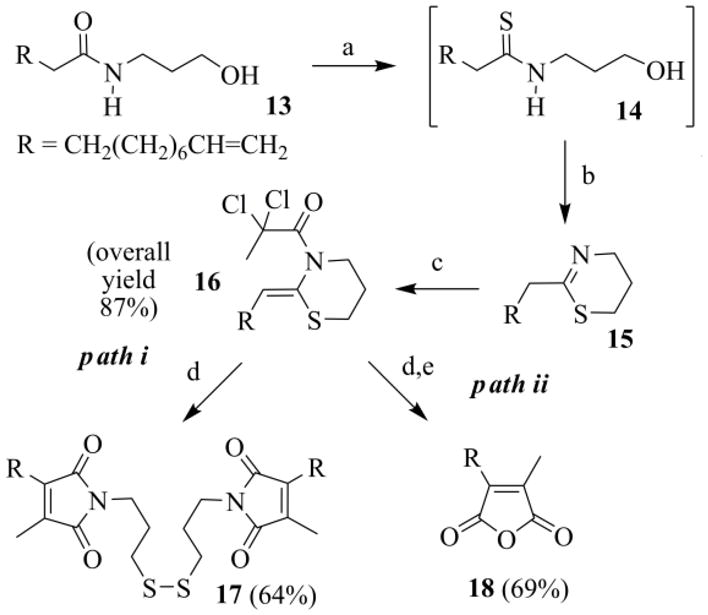

Aiming to develop an intrinsically versatile process, capable of delivering tailor-made ACA analogues, we targeted the construction of 18 (Scheme 9), a chaetomellic anhydride with a vinyl group at the end of a shorter aliphatic chain. An intermediate of this type is particularly valuable, since on the terminal CH=CH2 one can add thiols through a radical addition. This reaction, also known as thiol-ene coupling, is a useful “click” methodology.34

Scheme 9.

Preparation of anhydride 18: (a) P4S10/HMDO, CH2Cl2, reflux, 5h; (b) 150 °C, 2 h, under vacuum; (c) CH3CCl2COCl, Py, CH2Cl2, 0–25°C, 20 h; (d) CuCl (10 mol%), TMEDA (20 mol%), CH3CN/toluene (3/2), Na2CO3, argon, 30 °C, 19–24 h; (e) i) KI, H2O, 24 h, ii) NaOH, THF/H2O, r. t., 12h, acidic work-up.

The starting N-(3-hydroxypropyl)undec-10-enamide 13 can be easily obtained by manipulation of undecylenic acid, an interesting renewable resource,35 industrially produced on heating ricinoleic acid, the main component of castor oil.36 Hydroxyamide 13, treated as usual, gave the enamide 16 in high yield (Scheme 9). Enamide 16 was next subjected to the RC, which, after the addition of KI during the work-up procedure, afforded the symmetric disulfide 17 or, once it was hydrolyzed, the targeted anhydride 18 (Scheme 9, path i and ii respectively).

With the anhydride 18 in our hand, we were ready to test the thio-click reaction. We focused on the preparation of 19, an isosteric ACA analogue. Thus, the radical addition of butanethiol to 18 had to be realized. Since anhydride 18 carried two olefinic functions a problem of chemoselectivity could raise. The two C=C bonds are, however, quite different: one is electron-poor and tetrasubstituted, whereas the other is electron rich and monosubstituted. As the thiyl radical is electrophilic37 and the rate of radical attack controlled by steric and polar factors,38 we anticipated that attack at the apical methylene carbon should be favored.34d

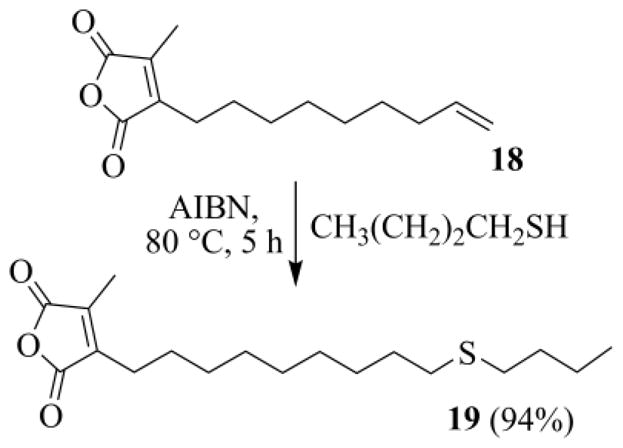

At the beginning we tried the initiation of the radical chain at room temperature, using organoboranes (such as triethylborane or 2-ethylbenzo[d][1,3,2]dioxaborole),39 but procedure and results were unappealing. We then resorted to AIBN, and gratifyingly an almost quantitative addition of butanethiol to the apical C=C was smoothly attained. No involvement of the maleic end, as foreseen, was noted (Scheme 10).

Scheme 10.

Radical addition of butanethiol to the terminal C=C group of 18.

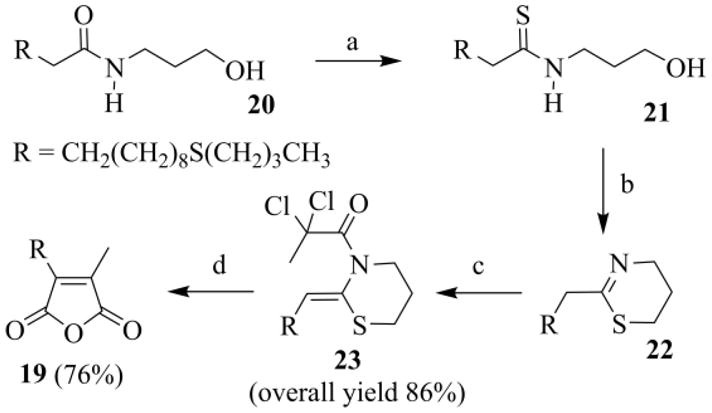

Alternatively 19 was also prepared, always in good yields, from the 11-(butylthio)-N-(3-hydroxypropyl)-undecanamide 20 (Scheme 11), by bringing forward the thiol-ene coupling on the starting hydroxyamide 13. It is noted that the thioether function in the aliphatic chain survived the oxidative deprotection of the thioacetal intermediate (not shown), and was not converted into a sulfoxide group.

Scheme 11.

Preparation of anhydride 19: (a) P4S10/HMDO, CH2Cl2, reflux, 5h; (b) 150 °C, 2 h, under vacuum; (c) CH3CCl2COCl, Py, CH2Cl2, 0–25°C, 20 h; (d) i) CuCl (10 mol%), TMEDA (20 mol%), CH3CN/toluene (3/2), Na2CO3, argon, 30 °C, 19–24 h, ii) KI, H2O, r.t., 24 h, iii) NaOH, THF/H2O, r. t., 12h, acidic work-up.

2.3. FTase assays

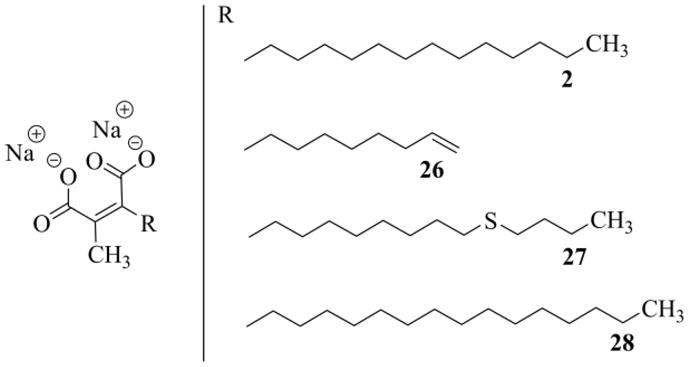

Taking in mind the previously pointed out pharmacological activity of ACA, we then examined the efficacy of the new chaetomellic analogue against the FTase, to see if the replacement of the tenth CH2 in the aliphatic tail with sulfur hadn't impaired the inhibition power. This required the preliminary conversion of the anhydride 19 into the corresponding disodium salt 27 (Figure 3). The conversion was efficiently achieved in four easy steps: i) reaction of the anhydride with a stoichiometric amount of NaOH in THF/H2O, ii) evaporation of the solution under vacuum, iii) re-dissolution of the remaining material in water, and finally iv) freeze-drying.19a Using this procedure we also prepared the sodium maleates 2 and 26, from the anhydrides 3 and 18 secured in this work, and 28, from 3-hexadecyl-4-methylfuran-2,5-dione21c that we had in stock (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Sodium maleates used in the FTase assays.

These substances were evaluated for inhibition against yeast and rat FTases, using the continuous fluorescence assay.40 In both assays we used the same dansylpeptide (dansyl-Gly-Cys-Val-Ile-Ala). As far as we know, there is no reported IC50 value with dansyl-GCVIA for inhibition of rat FTase. For example, peptidomimetic inhibitors were tested with dansyl-Gly-Cys-Val-Leu-Ser for inhibition of rat FTase, showing submicromolar activities.41 We believe that there is no major difference between dansyl-GCVIA and dansyl-GCVLS as a peptide substrate for inhibition of rat FTase. Since FTases are promiscuous with regard to the CAAX box, the exact sequence should not be a problem. Indeed Singh tried the same Ras-CVLS with both FTases, and he did not raise any doubt about the results of his tests.20c Interestingly Fierke, during his study on substrate recognition by wild FTase,42 observed that dansyl-GCVIA and dansyl-GCVLS were similarly recognized, respectively: kcat/KMpeptide 120 and 170 [mM−1 s−1], and kcat >0.2 and 0.4 [s−1]. In our IC50 measurements, the concentration of rat FTase was 10 times increased (15 nM against 1.5 nM) to compensate a possible lower affinity of dansyl-GCVIA for the enzyme and to increase the rate at which the bound substrate is converted to product. The IC50 values are summarized in Table 3.

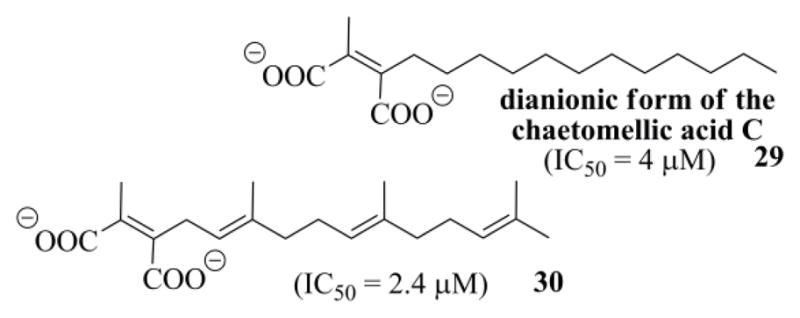

The value we determined for the sodium salt of chaetomellic acid A (2) against yeast FTase, compared very favorably to that previously measured (Table 1, n° 1).19a Astonishingly the thiaanalogue 27 was approximately 5 times more potent than ACA (Table 1 n° 1 and 3), showing an IC50 value (3.5 μM) near that of chaetomellic acid C 29 (4 μM) and of the farnesylated ACA analogue 30 (2.4 μM) (Figure 4).19a This result confirms that it is unnecessary to retain the hydrophobic farnesyl group for having potent FPP analogues inhibitors, contrary to what was previously claimed.43 Since FPP has more affinity for mammalian FTases,20c inhibition, as expected,20c was better against the rat Ftase (Table 1); above all, this second round of assays stressed the same order of activity between the four sodium maleates tested.

Table 1.

Inhibition of yeast and rat FTases by ACA and analogues.a

| n° | inhibitor | Yeast FTase IC50 (μM±SD) | Rat FTase IC50 (μM±SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 16.7 ± 0.9 (17 ± 3)18a | 0.91 ± 0.08 |

| 2 | 26 | 13.4 ± 1.1 | 0.49 ± 0.05 |

| 3 | 27 | 3.5 ± 0.3 | 0.19 ± 0.01 |

| 4 | 28 | 65.6 ± 16.7 | 2.6 ± 0.3 |

For conditions see “FTase assays” in the Experimental part.

Figure 4.

Structure of the ACA analogues 29 and 30, and their IC50 values against yeast FTase.19a

The size of the tail appears critical,20c in fact with chains ≥ 16 the inhibition power collapses (Table 1, n° 4). Unexpectedly the intermediate 26, notwithstanding it shorter C-9 chain (which, however, implement a terminal vinyl group), gave an IC50 at least analogous to that of the natural inhibitor 2.

2.4. Molecular Modelling

A posteriori computational analysis has been carried out on the interaction of thia-analogue 27 with FTase in order to get insights into its moderate increased inhibition potency with respect to the parent compound 2.

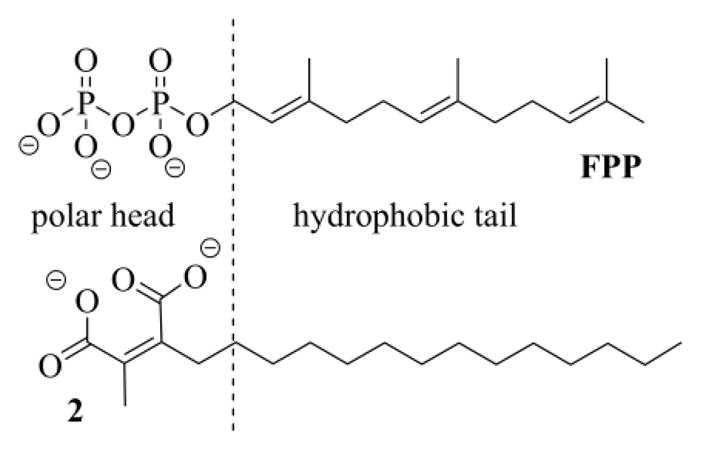

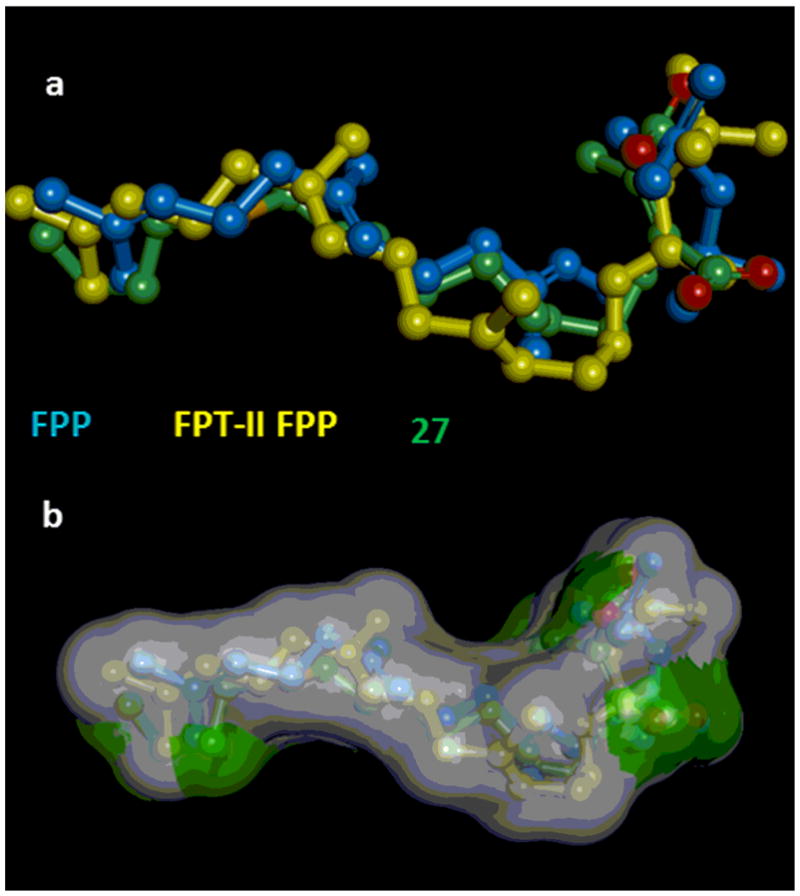

After an extensive analysis of the X-ray structures of FTase available in the PDB data bank, the X-ray structure of rat FTase complexed with farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP) (pdb ref code 1FT2)44 and of the ternary complex in which the rat FTase interacts with the FPT-II FPP analog and the substrate peptide CVLS (pdb ref code 1TN8)45 were selected. Superposition of the two 3D structures by alignment of all enzyme Cα atoms shows that the structures of the enzyme in these complexes are essentially identical, and the location and conformation of the isoprenoid and nonreactive isoprenoid analogs are very similar.

In fact, only a few minor side chain rearrangements are observed in the proximity of the anionic head binding sites of the isoprenoid analogs, and of the C-terminal carboxylate residues of the CVLS peptide.

The choice of the conformation of the thia-analogue 27 (among the many low-energy quasi-extended conformations it can assume) to be considered for docking experiments was based on: a) the best alignment with the isoprenoid analogs, taken as references; (Figure 5a and b) the best fit of the molecular volume of 27 and the volume of the supermolecule formed by FPP and FPT-II FPP, which can be considered to reflect the overall shape and the conformational flexibility of the enzyme binding site (Figure 5b).

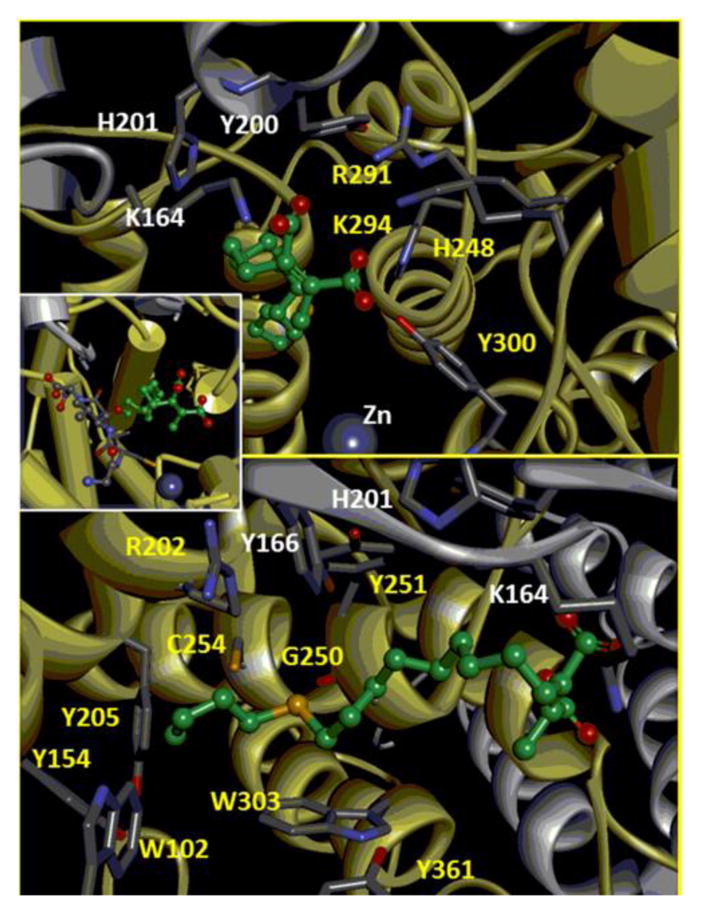

Figure 5.

a) Alignment of FPP, in the conformation assumed in the 1FT2 pdb structure (blue), FPT-II FPP, in the conformation assumed in the 1TN8 pdb structure (yellow), and of the thia-analogue 27 in the quasi-extended conformation chosen (atom colors: carbon atoms are in green, oxygen atoms in red, and sulfur atom in orange). b) Superposition of the molecular volume of 27 (green) and the volume of the supermolecule (white) formed by FPP and FPT-II FPP. In the figure the hydrogen atoms are omitted for clarity.

The structural motif of hydrophilic head group of 27 is well accommodated into the highly positively charged pocket, located near the subunit interface and adjacent to the catalytic zinc ion, which constitutes the site of the diphosphate moiety of farnesyl diphosphate (FPP) in the crystal structures of the binary and ternary complexes.7c,44,46 This pocket is formed by amino acid residues K164, Y200, and H201 from the α-subunit of the enzyme and Y300, K294, R291, H248 from the β-subunit (Figure 6, top).

Figure 6.

The interaction of inhibitor 27 and the FTase binding site. The enzyme α-subunit is represented in grey, the β-subunit is represented in yellow. Aminoacid residues involved in the interations are colored by element type (grey: carbon, blue: nitrogen, red: oxygen). Compound 27 is represented according to the color code of Figure 5. The hydrogen atoms are not displayed for clarity. Top: focus on the interactions of the anionic head of 27 with the FTase binding site; bottom: focus on the interactions established by the hydrophobic tail of compound 27; inset: an overall view of the ternary complex FTase-27-peptide (CVLS).

The hydrophobic tail of inhibitor 27 perfectly fits the length (14 Å) of the hydrophobic funnel-shaped groove of the enzyme, extended along one side of the cavity and it interacts with a number of conserved aromatic residues (Figure 6, bottom and inset). These are: Y154, W102, and Y205 of the β-subunit; they are located at the bottom of the hydrophobic cavity and are considered to constitute the discriminants for the maximum length of the ligands,44 C254, G250, Y251, W303, Y361 and the aliphatic portion of the side-chain of R202 of the β-subunit; Y166, H201, and aliphatic portion of the side-chain of K164 of the α-subunit.

The CVLS peptide sandwiches compound 27 against the wall of the hydrophobic cavity, sequestering the 20% of the solvent accessible surface, still available after the establishment of the binary complex, from the solvent permeating the cavity (Figure 6). A direct van der Waals contact between the Leu residue of the CVLS peptide and the aliphatic tail of 27 is observed. It is worth noting that the same interaction is achieved by Ile, upon mutation of the CAAX peptide used in the docking experiments into the one used in the experimental measurements (CVIA).

Interestingly, the sulfur atom in the aliphatic chain is found surrounded by three aromatic residues (W303, Y251, and Y156), R202, C254, and in direct contact with the oxygen atom of the backbone chain of G250. Thus, the high versatility of the divalent sulfur atom towards both electron-rich and electron-poor atoms is perfectly satisfied in this environment.47 In particular, the clear orientation preference for sulfur relative to oxygen atom of G250 could be a reason of the improved inhibitory power observed with respect to the parent ligand (compound 2) and it is worth of further investigations.

3. Conclusion

In this article we have described a new route to chaetomellic acid A (1). The process implements our recent method for the preparation of maleic anhydrides, which is based on the copper catalyzed radical cyclization of N-α-perchloroacyl-2-(Z)-alkyliden-1,3-tiazinanes. To make the process more appealing two critical adjustments had to be introduced: i) the preparation of the intermediate enamide was realized with a practical, cheap and efficient one-pot procedure, thanks to the use of the Curphey reagent in the thionation step, and ii) the required deprotection of the intermediate thioacetal was easily achieved through the addition of KI, during the work-up procedure of the radical cyclization reaction. Remarkably, conversion of the starting N-(3-hydroxypropyl)palmitamide into ACA (1) entailed only one intermediate chromatographic purification step.

Exploiting the fact that the process uses carboxylic acid as starting materials, this allowed for a versatile approach to the preparation of ACA analogues, through the synthesis of an intermediate maleic anhydride with a vinylic group at the end of the aliphatic tail, a function that can be transformed through a thiol-ene coupling. Alternatively, the same thia-analogue can be also efficiently secured, by bringing forward the thio-click reaction on the starting N-(3-hydroxypropyl)-unsaturated amide. This more rigid alternative well matches with the large-scale preparation of ACA analogues, as it avoids the use of a valuable maleic anhydride intermediate.

Finally, we serendipitously observed that the sodium salt 27, prepared from the representative sulfurated anhydride 19, was a more competent FTase inhibitor than ACA (1). On the ground of a molecular modeling study we attributed the improved inhibitory power of 27 to the direct contact of the sulfur atom with the oxygen atom of the backbone chain of G250. This result and the capability to assemble tailor made thia-analogues of ACA favorably meet and will be further investigated to identify competent molecules for the prevention of the ischemic damage.

4. Experimental part

4.1. General

Reagents and solvents were standard grade commercial products, purchased from Aldrich or Acros, and generally used without further purification. CH2Cl2 was dried over 3 Å sieves (5% w/v). Hexamethyldisiloxane was commercial or obtained following a literature procedure.48 2,2-Dicloropropanoyl chloride was prepared by chlorination with Cl2 of propionyl chloride in the presence of tetrabutylammonium chloride.24 The starting N-(3-hydroxypropyl)palmitamide49 7 and N-(3-hydroxypropyl)undec-10-enamide50 13 were secured in high yields (on the scale of 100–200 g) from the corresponding acids, after methylation and ensuing amino-de-methoxylation with 3-aminopropanol. The substitution is helped by the addition of K2CO3 10 mol% and of THF to solubilize the mixture of reagents (heating at reflux was required with methyl palmitate).29,51 The 11-(butylthio)-N-(3-hydroxypropyl)undecan-amide 20 was prepared in quantitative yield by standard radical addition of butanethiol to 13, using AIBN as initiator.34d,52 The silica gels used for flash chromatography was Silica Gel 60 Merck 0.040–0.063 mm. TLC were performed on silica coated plates Merck 60 F254, using UV light (254 nm) or cerium molybdate solutions to visualize the spots.

1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on ‘Varian 500 MHz’ or Jeol GSX 400. 13C NMR were obtained with full proton decoupling. 1H NMR and 13C NMR signals attribution was based on Gradient-Enhanced 1H,1H-DQF-COSY, 1H,13C-Edited-HSQC, and 1H,13C-HMBC experiments, run with standard pulses programmes. IR spectra were recorded on a ‘FT-IR Perkin Elmer 1600 Series’ while MS spectra on a ‘HP G1800C GCD System Series II’. High resolution mass spectra (HRMS) were obtained on an ‘Agilent 6520 Accurate-Mass Q-TOF LC/MS’ and ESI-MS were run on a Bruker Esquire 4000 instrument.

Recombinant yeast FTase was produced in Escherichia coli and purified over HisTrap affinity column (HisTrap™ HP, GE Healthcare) as previously described.53 Rat FTase was purchased from Jena Bioscience (Germany). n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside was purchased from ACROS (Geel, Belgium) and dansyl-Gly-Cys-Val-Ile-Ala was synthesized from HSC Core Research Facilities at University of Utah. Fluorescent signals for yeast FTase assays were recorded on a SpexFluoroMax spectrofluorimeter (Jobin Yuan Spex, Edison, NJ).

4.2. Preparation of ACA and analogues

4.2.1. Preparation of (Z)-3-(2,2-dichloropropanoyl)-2-pentadecylidene-1,3-thiazinane (10)

In a one necked 100 mL round bottom flask, fitted with a condenser, dry N-(3-hydroxypropyl)palmitamide 7 (20.0 mmol, 6.27 g) and P4S10 (3.68 mmol, 1.63 g) were weighed. Then dry CH2Cl2 (20 mL) and hexamethyldisiloxane (33.4 mmol, 7.16 mL) were added. The mixture, under stirring, was than heated at reflux (5 h). Afterwards the solvent was evaporated, and the remaining oil was stirred at 150 °C (2–3 h) under vacuum (8–9 mmHg), while argon, delivered through a capillary, bubbled inside the liquid (this helps the removal of silylphosphate, issued as side-product). Next the crude 2-pentadecyl-5,6-dihydro-4H-1,3-thiazine 9 was dissolved in dry CH2Cl2 (15 mL) and pyridine (50 mmol, 4.03 mL) added. The stirred solution was then cooled at 0 °C (ice bath) and 2,2-dichloropropanoyl chloride (30 mmol, 4,84 g), diluted in CH2Cl2 (5 mL), was slowly dropped (10 min), through a dropping funnel. Subsequently the ice-bath was removed. The mixture was thermostatted at 25 °C (20 h), afterwards it was diluted with water (40 mL). When all the solid, which developed during the acylation, was dissolved in the added water, the mixture was poured in a separation funnel, further diluted with other water (60 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (4 × 20 mL) (the separation of the phases is rather slow). The organic extracts were collected and evaporated. The crude mixture was purified by flash-chromatography on silica gel, eluting with a petroleum ether (PE, b.p. 40–70 °C)/diethyl ether (Et2O) gradient (from 100/0 to 90/10). The enamide 10 was recovered as a yellow oil (7.77 g, yield 89%); [HRMS found 436.2198. C22H40Cl2NOS (M+H)+ requires 436.2202]; Rf (95% PE/Et2O) 0.55; νmax (neat) 2924, 2853, 1663 cm−1; δH (500 MHz, CDCl3) 0.89 (t, J 7.1 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2), 1.27 (br s, 20H, (CH2)10), 1.35 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.44 (m, 2H, CH2CH2CH=C), 2.11 (br, 2H, SCH2CH2CH2N), 2.29 (m, 2H, CH2CH=C), 2.34 (s, 3H, CH3C), 2.87 (br s, 2H, CH2S), 4.17 (br, 2H, CH2N), 6.10 (br, 1H, CH=C); δC (125 MHz, CDCl3) 14.1, 22.6, 26.3 (broad), 28.6 (broad), 28.9, 29.3, 29.35, 29.4, 29.6, 29.65 (4 overlapped CH2), 29.7, 31.9, 36.9, 50.1, 80.2, 131.6 (broad and weak, C=), 136.2 (broad and weak, CH=), 163.4; ESI-MS: 436.6 [M+H]+.

4.2.2. Radical cyclization of (Z)-3-(2,2-dichloropropanoyl)-2-pentadecylidene-1,3-thiazinane (10)

CuCl (0.42 mmol, 0.042 g), Na2CO3 (4.6 mmol, 0.488 g) and the substrate 10 (4.2 mmol, 1.84 g) were weighed into an oven dried Schlenk tube, then CH3CN/toluene 1:1 (6.3 mL) and TMEDA (0.2 mmol, 126 μL) were added under argon. The mixture was stirred at 30 °C and after 24 h diluted with water (30 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers were concentrated under vacuum. Flash chromatography of the recovered material on silica gel, eluting with a PE/Et2O gradient (from 100/0 to 20/80) gave the disulfide 11 (0.45 g, 28%) as a white wax, [HRMS found 761.5324. C44H77N2O4S2 (M+H)+ requires 761,5319], Rf (60% PE/Et2O) 0.42, and the thioacetal 12 (0.92 g, 58%) as a white solid [HRMS found 745.5380. C44H77N2O3S2 (M+H)+ requires 745,5370], Rf (60% PE/Et2O) 0.20, mp 63–64 °C.

4.2.2.1. 1,1′-[3,3′-Disulfanediylbis(propane-3,1-diyl)]bis(3-methyl-4-tetradecyl-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione) (11)

νmax(Nujol) 1768 and 1708 cm−1; δH (500 MHz, CDCl3): 0.88 (t, J 7.0 Hz, 6H, CH3CH2), 1.26 (brs, 36H, 2 × (CH2)9), 1.29 (8H, (CH2)4), 1.52 (bm, 4H, 2 × CH2CH2C=C), 1.96 (s, 6H, 2 × CH3), 1.97 (quint, J 6.9 Hz, 4 H, 2 × SCH2CH2CH2N), 2.36 (t, J 7.3 Hz, 4H, 2 × CH2-C=C,), 2.68 (t, J 6.9 Hz, 4H, 2 × CH2S), 3.57 (t, J 6.9 Hz, 4H, 2 × CH2N); δC (125 MHz, CDCl3): 8.5, 13.9, 22.5, 23.5, 28.0, 28.1, 29.1, 29.2, 29.35, 29.40, 29.5, 31.8, 35.4, 36.5, 136.9, 141.2, 171.9, 172.2; ESI-MS: 783.8 [M+Na]+..

4.2.2.2. 3-Methyl-1-{3-(8-methyl-6-oxo-7-tetradecyl-3,4,6,8a-tetrahydro-2H-pyrrolo[2,1-b][1,3]thiazin-8a-ylthio)propyl}-4-tetradecyl-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione (12)

νmax (neat) 1706, 1681 cm−1; δH (500 MHz, CDCl3) 0.89 (2t, J 7.0 Hz each, 6H, 2 × CH3CH2), 1.26 (br, 43H), 1.38 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.51 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.60 (m, 2H, CHaxH + CH), 1.65 (quint, J 7.0 Hz, 2H, CH2CH2CH2), 1.83 (t, J 7.0 Hz, 2H, CH2S), 1.91 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.96 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.99 (bdt, 1H, CHeqH), 2.37 (m, 3H, CH2-C=C + CHH-C=C), 2.49 (m, 1H, CHH-C=C), 2.67 (dt, J 13.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H, CHeqHS), 3.08 (dt, J 13.2, 3.0 Hz, 1H, CHaxHN,), 3.34 (dt, J 13.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H, CHaxHS), 3.45 (m, 2H, CH2N), 4.30 (br dt, J 13.2, 1.3 Hz, 1H, CHeqHN); δC (125 MHz, CDCl3) 8.66, 8.98, 14.10, 22.67, 23.69, 25.75, 25.88, 26.80, 27.80, 27.82, 28.20, 28.83, 29.26, 29.33, 29.34, 29.35, 29.50, 29.54, 29.56, 29.62, 29.63, 29.65, 29.67, 29.68, 30.14, 31.90, 31.91, 35.71, 37.04, 74.37, 129.69, 136.93, 141.20, 154.38, 168.12, 171.81, 172.10; ESI-MS: 767.8 [M+Na]+.

4.2.3. Preparation of 1,1′-[3,3′-disulfanediylbis(propane-3,1-diyl)]bis(3-methyl-4-tetradecyl-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione)(11)

CuCl (0.50 mmol, 0.050 g), Na2CO3 (5.5 mmol, 0.590 g) and the substrate 10 (5.0 mmol, 2.19 g) were weighed into an oven dried Schlenk tube, then CH3CN/toluene 3:2 (5 mL) and TMEDA (0.2 mmol, 151 μL) were added under argon. The mixture was stirred at 30 °C and after 19 h the tube was open and KI (100 mg) and a few drops of water were added. The mixture was vigorously stirred in the open air for 24 h, after which it was diluted with water (30 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers were concentrated under vacuum. Flash chromatography of the recovered material on silica gel, eluting with a PE/Et2O gradient (from 100/0 to 40/60) gave the disulfide 11 (1.35 g, 71%).

4.2.4. Hydrolysis of 1,1′-(3,3′-disulfanediylbis(propane-3,1-diyl))bis(3-methyl-4-tetradecyl-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione) (11)

In a one-necked 25 mL Erlenmeyer flask 11 (2.5 mmol, 1.903 g), THF (2.5 mL) and a solution of NaOH 5 M (2.5 mL) were added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h, after which it was treated with HCl 36% (2 mL), diluted with brine/water 1/1 and extracted with CH2Cl2 Flash chromatography of the recovered material on silica gel, eluting with a PE/Et2O gradient (from 100/0 to 20/80) gave the chaetomellic anhydride A 3 (1.45 g, 94%); spectroscopic data are in agreement with those reported in the literature.21b

4.2.5. Preparation of chaetomellic anhydride A (3)

CuCl (2.00 mmol, 0.200 g), Na2CO3 (22.0 mmol, 2.332 g) and the substrate 10 (20.0 mmol, 8.73 g) were weighed into an oven dried Schlenk tube, then CH3CN/toluene 3:2 (20 mL) and TMEDA (4.0 mmol, 604 μL) were added under argon. The mixture was stirred at 30 °C and after 19 h the tube was open and KI (400 mg) and a few drops of water were added. The mixture was vigorously stirred in the open air for 24 h, after which it was diluted with water (50 mL) and extracted with CH2Cl2 (3 × 15 mL). The combined organic layers were concentrated under vacuum. The recovered material was diluted with THF (10 mL). Next a solution of NaOH 5 M (10 mL) was added. The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h, after which it was treated with HCl 36% (8 mL), diluted with brine/water 1/1 and extracted with CH2Cl2. Flash chromatography of the recovered material on silica gel, eluting with a PE/Et2O gradient (from 100/0 to 20/80) gave the chaetomellic anhydride A 3 (4.40 g, 71%).

4.2.6. Preparation of (Z)-3-(2,2-dichloropropanoyl)-2-(dec-9-enylidene)-1,3-thiazinane (16)

Following the same procedure used to prepare 10, N-(3-hydroxypropyl)undec-10-enamide 13 (40 mmol, 9.66 g) gave 16 as a yellow oil (12.69 g, yield 87%); [HRMS found 364.1240. C17H28Cl2NOS (M+H)+ requires 364.1263]; Rf (95% PE/Et2O) 0.50; νmax (neat) 3075, 2925,2854 and 1664 cm−1; δH (500 MHz, CDCl3) 1.32, 1.38, 1.44 (overlapped multiplets, 10H, (CH2)5), 2.05 (dq, 2H, J 7.1, 1.2 Hz, CH2CH=CH2), 2.11 (br s, 2H, SCH2CH2CH2N), 2.29 (q, 2H, J 7.5 Hz, CH2CH=CNS), 2.34 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.87 (br s, 2H, CH2S), 4.17 (br s, 2H, CH2N), 4.94 (part A of an AMXY2 system, Jcis 10.2, 2.1, 1.2 Hz, 1H, CHH=), 5.00 (part M of an AMXY2 system, Jtrans 16.9, Jgem 2.1, 1,4J 1.2 Hz, 1H, CHH =), 5.82 (part X of an AMXY2, Jtrans 16.9, Jcis 10.2, 3J 6.8 Hz, 1H, CH=CH2), 6.21 (broad, 1H, CH=CNS); δC (125 MHz, CDCl3) 26.1, 28.3, 28.7, 28.8 (2 overlapped CH2), 28.9, 29.0, 29.6, 33.5, 36.7, 50.0, 80.1, 114.1, 131.6 (broad and weak, C=) 135.0 (s, broad and weak, CH=C), 139.1, 163.5; ESI-MS: 364.5 [M+H]+, 386.4 [M+Na]+.

4.2.7. Preparation of 1,1′-(3,3′-disulfanediylbis(propane-3,1-diyl))bis(3-methyl-4-(non-8-enyl)-1H-pyrrole-2,5-dione)(17)

Following the same procedure used to prepare 11, (Z)-3-(2,2-dichloropropanoyl)-2-(dec-9-enylidene)-1,3-thiazinane 16 (5.0 mmol, 1.83 g) gave 17 as a pale yellow oil (0.99 g, 64%); [HRMS found 617.3450. C34H53N2O4S2 (M+H)+ requires 617.3441]; Rf (70% PE/Et2O) 0.52; νmax (neat) 3455, 3074, 1768, 1703, 1640 cm-1; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 1.28 (brs, 12H, 2 × (CH2)3), 1.35 (4H), 1.50 (bm, 4H, 2 × CH2CH2C=C), 1.94 (s, 6H, 2 × CH3), 1.94 (m, overlapped, 4H, 2 × SCH2CH2CH2N), 2.02 (br q, J 7.9 Hz, 4H, 2 × CH2CH=C), 2.35 (t, J 7.7, 4H, 2 × CH2C=C,), 2.62 (t, J 7.3 Hz, 4H, 2 × CH2S), 3.55 (t, J 7.3 Hz, 4H, 2 × CH2N), 4.91 (part A of an AMXY2 system, Jcis 10.2, Jgem 2.1, 1.4J 1.2 Hz, 2H, CHH=), 4.97 (ddq, part M of an AMXY2 system, Jtrans 16.9, Jgem 2.1, 1,4J 1.2 Hz, 2H, 2 × CHH=), 5.78 (part X of an AMXY2, Jtrans 16.9, Jcis 10.3, JXY 6.8 Hz, 2H, 2 × CH=C); δC (100.1 MHz, CDCl3) 8.7, 23.6, 28.1, 28.2, 28.8, 28.9, 29.1, 29.4, 33.7, 36.0, 36.6, 114.2, 136.9, 139.0, 141.1, 171.9, 172.2; ESI-MS: 639.1 [M + Na]+.

4.2.8. Preparation of 3-methyl-4-(non-8-enyl)furan-2,5-dione (18)

Following the same procedure used to prepare 3, (Z)-3-(2,2-dichloropropanoyl)-2-(dec-9-enylidene)-1,3-thiazinane 16 (20 mmol, 7.29 g) gave 18, as a pale yellow oil (3.26 g, overall yield 69%); [HRMS found 237.1465. C14H21O3 (M+H)+ requires 237.1485]; Rf (90% PE/Et2O) 0.30. νmax (neat). 3076, 1853, 1821 (w), 1767 (str), 1673 (w) cm−1; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 1.28 (br s, 6H, (CH2)3), 1.35 (2H, CH2), 1.56 (bm, 2H, CH2), 2.01 (m, 2H, CH2CH=C), 2.05 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.43 (t, J 7.9, 2H, CH2C=C,), 4.91 (part A of an AMXY2 system, Jcis 10.2, Jgem 2.1, 1,4J 1.2 Hz, 1H, CH2=), 4.97 (ddq, part M of an AMXY2 system, Jtrans 17.8, Jgem 2.1, 1,4J 1.2 Hz, 1H, CH2=), 5.78 (part X of an AMXY2, Jtrans 17.8, Jcis 10.3, JXY 6.8 Hz, 1H, CH=C); δC (100.1 MHz, CDCl3) 9.5, 24.4, 27.5, 28.7, 28.8, 29.0, 29.3, 33.6, 114.2, 138.9, 140.4, 144.7, 165.8, 166.2; m/z (EI, 70 eV) 236 (2, M+), 191 (100), 163 (21), 126 (97%).

4.2.9. Addition of butane-1-thiol to 3-methyl-4-(non-8-enyl)furan-2,5-dione (18)

AIBN (0.2 mmol, 0.033 g) and anhydride 18 (10.0 mmol, 2.36 g) were weighed into an oven dried Schlenk tube, then 1-butanethiol (20.0 mmol, 2.1 mL) were added under argon. The mixture was stirred at 80 °C (5 h). Next the unreacted thiol was evaporated under vacuum. Flash chromatography of the recovered material on silica gel, eluting with a PE/Et2O gradient (from 100/0 to 20/80) gave 19, as a pale yellow oil (3.07 g, 94%); [HRMS found 327.1980. C18H31O3S (M+H)+ requires 327.1989]; Rf (90% PE/Et2O) 0.26); νmax (neat). 1855, 1821, 1766 (str), 1673 cm−1; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 0.89 (t, J 7.5 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2), 1.28 (bm, 8H, CH2), 1.37 (m, 4H, 2 × CH2) 1.54 (m, 6H, 3 × CH2), 2.04 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.34 (t, J 7.8 Hz, 2H, CH2C=), 2.47 (t, J 7.4 Hz, 2H, CH2S), 2.48 (t, J 7.6 Hz, 2H, CH2S); δC (100.1 MHz, CDCl3) 9.5, 13.7, 220, 24.4, 27.5, 28.8, 29.1, 29.12, 29.2, 29.4, 29.6, 31.8, 31.82, 32.1, 140.4, 144.7, 165.8, 166.2; m/z (EI, 70 eV) 326 (33, M+), 283 (8), 269 (52), 201 (74), 191 (32), 126 (38), 61 (100%).

4.2.10. Preparation of (Z)-3-(2,2-dichloropropanoyl)-2-[10-(butylthio)decylidene] -1,3-thiazinane (23)

Following the same procedure used to prepare 10, 11-(butylthio)-N-(3-hydroxypropyl)undecanamide 20 (20 mmol, 6.64 g) gave 23 as a pale yellow oil (7.83 g, overall yield 86%); [HRMS found 454.1780. C21H38Cl2NOS2 (M+H)+ requires 454.1766]; Rf (90% PE/Et2O) 0.85; νmax (neat) 2926, 2850, 1700, 1667 cm−1; δH (400 MHz, CDCl3) 0.89 (t, J 7.1 Hz, 3H, CH3CH2), 1.26 (broad, 12H), 1.39 (m, 2H, CH2CH3), 1.55 (m, 4H), 2.09 (broad, 2H, SCH2CH2CH2N), 2.26 (m, 2H, CH2CH=C), 2.31 (s, 3H, CH3), 2.48 (t, J 7.9 Hz, 2H, CH2S), 2.49 (t, J 7.9 Hz, 2H, CH2S), 2.84 (broad, 2H, CH2S), 4.21 (broad, 2H, CH2N), 6.23 (broad, 1H, CH=C); δC (100.1 MHz, CDCl3) 13.7, 22.0, 26.2 (broad), 28.6 (broad), 28.9, 29.2, 29.22, 29.3, 29.4, 29.7, 31.8, 31.9, 32.2, 36.8, 50.2 (broad); 80.2 (CCl2), 131.5 (broad and weak, C=), 136.4 (broad and weak, CH=), 163.4 (CO); ESI-MS: 454.6 [M+H]+.

4.2.11. Preparation of 3-(9-(butylthio)nonyl)-4-methylfuran-2,5-dione (19) from 23

Following the same procedure used to prepare 3, (Z)-3-(2,2-dichloropropanoyl)-2-[10-(butylthio)decylidene]-1,3-thiazinane 23 (10 mmol, 4.55 g) gave 19, as a pale yellow oil (2.49 g, overall yield 76%).

4.3. FTase assays

4.3.1. Preparation of the sodium salts from the chaetomellic anhydrides: general procedure

In a one-necked 25 mL Erlenmeyer flask chaetomellic anhydride A or analogues (50–70 mg), THF/H2O 1/1 (2 mL/50 mg of anhydride) and a solution of NaOH 1 M (2 equiv) were added. After overnight stirring at room temperature (16 h), the solvent was removed, the remaining material was dissolved in H2O (3–4 mL). Freeze-drying of this solution [−13 °C (48 h) and then 25 °C (24 h) at 0.4–0.5 mmHg] gave the sodium salts as a white solid.

4.3.2. Yeast and Rat Farnesyl Transferase assays40

Assays were conducted in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.0, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 μM ZnCl2, 5 mM DTT, 0.04% (w/v) n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside and 2.4 μM dansyl-Gly-Cys-Val-Ile-Ala (dansyl-GCVIA). Reactions mixtures were preincubated at 30 °C for 5 min before farnesylation was initiated by addition of recombinant yeast FTase (1.5 nM) or rat FTase (15 nM). The fluorescence λ emission at 486 nm (slit width = 5.1 nm) was measured at λ excitation = 340 nm (slit width = 5.1 nm) for dansyl-GCVIA, using 3 mm square quartz cuvettes. The fluorescence intensity was measured for 300 sec. All measurements were made in triplicate.

4.4. Molecular Modelling Methods

The inhibitor 27 was constructed using 3D sketcher module of the Discovery Studio software from Acclerys (Accelrys Inc., San Diego, CA. (http://accelrys.com/products/) and was subjected to conformational analysis and energy minimization by means of the AM1 molecular orbital hamiltonian.

The X-ray structures of rat FTase complexed with farnesyl pyrophosphate (FPP)44 and of the ternary complex in which the rat FTase interacts with the FPT-II FPP analog and the substrate peptide CVLS45 were retrieved from the the Protein Data Bank (PDB: their pdb ref code are 1FT2 and 1TN8, respectively).54

The binary FTase-27, and ternary FTase-27-peptide (CVLS) complexes were built by docking into the enzyme the conformation of compound 27 which satisfies contemporaneously the two following requirements: 1) minimum the molecular volume exceeding the volume of the supermolecule formed by the alignment of FPP and FPT-II FPP, and 2) maximum difference of the energy of the conformation chosen with respect the energy of the molecule in its extended conformation (assumed to be the global minimum) of 2 kcal/mol.

The complexes were minimized by 10000 steps of steepest descent followed by conjugate gradient until the system energy converged to 1e-05 kJ/mol using the CHARMM force-field.55 Standard protonation states, corresponding to pH 7, were assigned to the amino acid residues.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca (MIUR, PRIN 20085E2LXC-004, 20085E2LXC-003), the National Institute of Health (NIH Grant GM 21328) and the EU (under the ERASMUS scheme) for financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary data, containing 1H-NMR spectra of compounds 10, 11, 12, 16, 17, 18, 19 and 23, can be found in the online version.

References and notes

- 1.(a) Leonard DM. J Med Chem. 1997;40:2971–2990. doi: 10.1021/jm970226l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Beck LA, Hosick TJ, Sinensky M. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1307–1316. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.4.1307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Wolda SL, Glomset JA. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:5997–6000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Lane KT, Beese LS. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:681–699. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R600002-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Winter-Vann AM, Casey PJ. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:405–412. doi: 10.1038/nrc1612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Anderegg RJ, Betz R, Carr SA, Crabb JW, Duntze W. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:18236–18240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Farnsworth CC, Wolda CL, Gelb MH, Glomset JA. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:20422–20429. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Casey PJ, Solski PA, Der CJ, Buss JE. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:8323–8327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.21.8323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Maltese WA, Robishaw JD. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:18071–18074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Fukada Y, Takao T, Ohguru H, Yoshizawa T, Akino T, Shimonishi Y. Nature (London) 1990;346:658–660. doi: 10.1038/346658a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (f) Lai RK, Perez-Sala D, Canada FJ, Rando RR. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7673–7677. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Moores SL, Schaber MD, Mosser SD, Rands E, O'Hara MB, Garsky VM, Marshall MS, Pompliano DL, Gibbs JB. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:14603–14610. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow M, Der CJ, Buss JE. Curr Opinion Cell Biol. 1992;4:629–636. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(92)90082-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schafer WR, Rine J. Annu Rev Genet. 1992;26:209–237. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.26.120192.001233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Hancock JF, Magee AI, Chilad JE, Marshall CJ. Cell. 1989;57:1167–1177. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90054-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Schafer WR, Kim R, Sterne R, Thorner J, Kim SH, Rine J. Science. 1989;245:379–385. doi: 10.1126/science.2569235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Gibbs JB, Oliff A, Kohl NE. Cell. 1994;77:175–178. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90308-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Bell IM. J Med Chem. 2004;47:1869–1878. doi: 10.1021/jm0305467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Santagada V, Caliendo G, Severino B, Lavecchia A, Perissutti E, Fiorino F, Zampella A, Sepe V, Califano D, Santelli G, Novellino E. J Med Chem. 2006;49:1882–1890. doi: 10.1021/jm0506165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Sousa SF, Fernandes PA, Ramos M. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:8681–8691. doi: 10.1021/jp711214j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dunten P, Kammlott U, Crowther R, Weber D, Palermo R, Birktoft J. Biochemistry. 1998;37:7907–7912. doi: 10.1021/bi980531o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Pompliano DL, Schaber MD, Mosser SD, Omer CA, Shafer JA, Gibbs JB. Biochemistry. 1993;32:8348–8359. doi: 10.1021/bi00083a038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scholten JD, Zimmerman K, Oxender M, Sebolt-Leopold J, Gowan R, Leonard D, Hupe D. J Bioorg Med Chem. 1996;4:1537–1543. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vilella D, Sánchez M, Platas G, Salazar O, Genilloud O, Royo I, Cascales C, Martin I, Diez T, Silverman KC, Lingham RB, Singh SB, Jayasuriya H, Peláez F. J Ind Microbiol Biotech. 2000;25:315–327. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.7000085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Singh SB, Zink DL, Liesch JM, Goetz MA, Jenkins RG, Nallin-Omstead M, Silverman KC, Bills GF, Mosley RT, Gibbs JB, Albers-Schonberg G, Lingham RB. Tetrahedron. 1993;49:5917–5926. [Google Scholar]; (b) Lingham RB, Silvermann KC, Bills GF, Cascales C, Sanchez M, Jenkins RG, Gartner SE, Martin I, Diez MT, Peláez F, Mochales S, Kong YL, Burg RW, Meinz MS, Huang L, Nallin-Omstead M, Mosser SD, Schaber MD, Omer CA, Pompliano DL, Gibbs JB, Singh SB. Appl Microbiol, Biotechnol. 1993;40:370–374. doi: 10.1007/BF00170395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbs JB, Pompliano DL, Mosser SD, Rands E, Lingham RB, Singh SB, Scolnick EM, Kohl NE, Oliff A. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:7617–7620. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scholte AA, Eubanks LM, Poulter CD, Vederas JC. Biorg Med Chem. 2004;12:763–770. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2003.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andréa H, Fischt I, Bach TJ. Physiol, Plant. 2000;110:342–349. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mau CJD, Garneau S, Scholte AA, Van Fleet JE, Vederas JC, Cornish K. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:3939–3945. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garneau S, Qiao L, Chen L, Walker S, Vederas JC. Biorg Med Chem. 2004;12:6473–6494. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Sabattini M, Santillo M, Pisani A, Paternò R, Uccello F, Serù R, Matrone G, Spagnuolo G, Andreucci M, Serio V, Esposito P, Cianciaruso B, Fiano G, Avvedimento EV. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F1408–F1415. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00304.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sabattini M, Uccello F, Serio V, Troncone G, Varone V, Andreucci M, Faga T, Pisani A. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F1408–F1415. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00304.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ruocco A, Santillo M, Cicale M, Serù R, Cuda G, Anrather J, Iadecola C, Postiglione A, Avvedimento EV, Paternò R. Eur J Neurosci. 2007;26:3261. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.(a) Singh SB, Bills GF, Lingham RB, Silverman KG, Zink DL. Chem Abstr. 1993;119:225753. EP 547671, 1992. [Google Scholar]; (b) Caskey CT, Nishimura S, Yonemoto M. Chem Abstr. 1997;126:171903. WO 9701275, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.(a) Ratemi ES, Dolence JM, Poulter CD, Vederas JC. J Org Chem. 1996;61:6296–6301. doi: 10.1021/jo960699k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Poigny S, Guyot M, Samadi M. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1997;1:2175–2177. [Google Scholar]; (c) Desai SB, Argade NP. J Org Chem. 1997;62:4862–4863. [Google Scholar]; (d) Deshpande AM, Natu AA, Argade NP. J Org Chem. 1998;63:9557–9558. [Google Scholar]; (e) Slade RM, Branchaud BP. J Org Chem. 1998;63:3544–3549. [Google Scholar]; (f) Kar A, Argade NP. J Org Chem. 2002;67:7131–7134. doi: 10.1021/jo020195o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (g) Haval KP, Argade NP. J Org Chem. 2008;73:6936–6938. doi: 10.1021/jo801284r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (h) Kshirsagar UA, Argade NP. Synthesis. 2011:1804–1808. [Google Scholar]

- 20.(a) Argade NP, Naik RH. Biorg Med Chem. 1996;4:881–883. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00076-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Kates MJ, Schauble JH. J Org Chem. 1996;61:4164–4167. doi: 10.1021/jo9601977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Singh SB, Jayasuriya H, Silverman KC, Bonfiglio CA, Williamson JM, Lingham RB. Biorg Med Chem. 2000;8:571–580. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(99)00312-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Takimoto M, Kawamura M, Mori M, Sato Y. Synlett. 2005:2019–2022. [Google Scholar]; (e) Yoshimitsu T, Arano Y, Kaji T, Ino T, Nagaoka H, Tanaka T. Heterocycles. 2009;77:179–186. [Google Scholar]

- 21.(a) De Buyck L, Cagnoli R, Ghelfi F, Merighi G, Mucci A, Pagnoni UM, Parsons AF. Synthesis. 2004:1680–1686. [Google Scholar]; (b) Bellesia F, Danieli C, De Buyck L, Galeazzi R, Ghelfi F, Mucci A, Orena M, Pagnoni UM, Parsons AF, Roncaglia F. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:746–757. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ghelfi F, Pattarozzi M, Roncaglia F, Giangiordano V, Parsons AF. Synth Commun. 2010;40:1040–1051. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghelfi F, Pattarozzi M, Roncaglia F, Parsons AF, Felluga F, Pagnoni UM, Valentin E, Mucci A, Bellesia F. Synthesis. 2008:3131–3141. [Google Scholar]

- 23.(a) Pattarozzi M, Ghelfi F, Roncaglia F, Pagnoni UM, Parsons AF. Synlett. 2009:2172–2175. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cornia A, Felluga F, Frenna V, Ghelfi F, Parsons AF, Pattarozzi M, Roncaglia F, Spinelli D. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:5863–5881. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bellesia F, D'Anna F, Felluga F, Frenna V, Ghelfi F, Parsons AF, Spinelli D. Synthesis. 2012:605–609. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fuganti C, Gatti FG, Serra S. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:4762–4767. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hajipour AR, Zarei A, Khazdooz L, Ruoho AE. Synthesis. 2006:1480–1484. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ozturk T, Ertas E, Mert O. Chem Rev. 2010;110:3419–3478. doi: 10.1021/cr900243d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Curphey TJ. J Org Chem. 2002;67:6461–6473. doi: 10.1021/jo0256742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Forti L, Ghelfi F, Grandi R, Libertini E, Pagnoni UM. Synthetic Commun. 1996;26:3517–3526. [Google Scholar]

- 30.(a) Kim JK, Souma Y, Beutow N, Ibbeson C, Caserio MC. J Org Chem. 1989;54:1714–1720. [Google Scholar]; (b) Thewalt von K, Renchhoff G. Fette Seifen Anstrichmittel. 1968;70:648–658. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wuts PGM, Greene TW. Greene's Protective Groups in Organic Synthesis. 4. Wiley-Interscience; New York: 2007. pp. 477–500. [Google Scholar]

- 32.(a) Kim H, Hong J. Org Lett. 2010;12:2880–2883. doi: 10.1021/ol101022z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Ganguly NC, Barik SK. Synthesis. 2009:1393–1399. [Google Scholar]; (c) Dai WM, Feng G, Wu J, Sun L. Synlett. 2008:1013–1016. [Google Scholar]; (d) Kirihara M, Harano A, Tsukiji H, Takizawa R, Uchiyama T, Hatano A. Tetrahedron Lett. 2005;46:6377–6380. [Google Scholar]

- 33.De Brauwere A, Baeyens W, De Ridder F, Elskens M. Talanta. 2009;80:1034–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.talanta.2009.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.(a) Franc G, Kakkar AK. Chem Soc Rev. 2010;39:1536–1544. doi: 10.1039/b913281n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Lowe AB. Polym Chem. 2010;1:17–36. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hoyle CE, Bowman CN. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2010;49:1540–1573. doi: 10.1002/anie.200903924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Griesbaum K. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1970;9:273–287. [Google Scholar]

- 35.(a) Van der Steen M, Stevens CV. ChemSusChem. 2009;2:692–713. doi: 10.1002/cssc.200900075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Dalavoy VS, Nayak UR. J Sci Ind Res. 1981;40:520–528. [Google Scholar]

- 36.(a) Mutlu H, Meier MAR. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol. 2010;112:10–30. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ogunniyi DS. Biores Technol. 2006;97:1086–1091. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.(a) Ito O, Fleming MDCM. J Chem Soc, Perkin Trans. 1989;II:689–693. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ito O, Matsuda M. J Am Chem Soc. 1979;101:5732–5735. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Giese B. Angew Chem Int Ed. 1983;22:753–764. [Google Scholar]

- 39.(a) Schaffner AP, Renaud P. Eur J Org Chem. 2004:2291–2298. [Google Scholar]; (b) Ollivier C, Renaud P. Chem, Rev. 2001;101:3415–3434. doi: 10.1021/cr010001p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.(a) Pompliano DL, Gomez RP, Anthony NJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:7945–7946. [Google Scholar]; (b) Cassidy PB, Dolence JM, Poulter CD. Methods Enzymol. 1995;250:30–43. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)50060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bolchi C, Pallavicini M, Bernini SK, Chiodini S, Corsini A, Ferri N, Fumagalli L, Straniero V, Valoti E. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2011;21:5408–5412. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Houghland JL, Lamphear CL, Scott SA, Gibbs RA, Fierke CA. Biochemistry. 2009;48:1691–1701. doi: 10.1021/bi801710g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel DV, Schmidt RJ, Biller SA, Gordon EM, Robinson SS, Manne V. J Med Chem. 1995;38:2906–2921. doi: 10.1021/jm00015a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Long SB, Casey PJ, Beese LS. Biochemistry. 1998;37:9612–9618. doi: 10.1021/bi980708e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reid TS, Terry KL, Casey PJ, Beese LS. J Mol Biol. 2004;343:417–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Strickland CL, Windsor WT, Syto R, Wang L, Bond R, Wu Z, Schwartz J, Le HV, Beese LS, Weber PC. Biochemistry. 1998;37:16601–16611. doi: 10.1021/bi981197z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brameld KF, Kuhn B, Reuter DC, Stahl M. J Chem Inf Model. 2008;48:1–24. doi: 10.1021/ci7002494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Drabowicz J, Bujnicki B, Mikolajczyk M. J Lab Cmpds Radiopharm. 2003;46:1001–1005. [Google Scholar]

- 49.(a) Guan LP, Sui X, Deng XQ, Zhao DH, Qu YL, Quan ZS. Med Chem Res. 2011;20:601–606. [Google Scholar]; (b) Shen G, Fang H, Song Y, Bielska AA, Wang Z, Taylor JSA. Bioconjugate Chem. 2009;20:1729–1736. doi: 10.1021/bc900048y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Fraunhoffer KJ, Prabagaran N, Sirois LE, White C. J Am Chem Soc. 2006;128:9032–9033. doi: 10.1021/ja063096r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dodd JH, Guan J, Schwender CF. Synthetic Commun. 1993;23:1003–1008. [Google Scholar]

- 52.(a) Yasuda H, Uenoyama Y, Nobuta O, Kobayashi S, Ryu I. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:367–370. [Google Scholar]; (b) Broxterman QB, Kaptein B, Kamphuis J, Schoemaker HE. J Org Chem. 1992;57:6286–6294. [Google Scholar]; (c) Kharasch MS, Read J, Mayo FR. Chem Ind. 1938;57:752–756. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mayer MP, Prestwich GD, Dolence JM, Bond PD, Wu HW, Poulter CD. Gene. 1993;132:41–47. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(93)90512-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Berman HM, Westbrook J, Feng Z, Gilliland G, Bhat TN, Weissig H, Shindyalov IN, Bourne PE. The Protein Data Bank, Nucl Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. J Comp Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.