Abstract

We report a highly probable case of transmission of a Yersinia enterocolitica from a pet puppy dog, adopted from a Spanish asylum, to a 1-year-old girl. After several weeks of diarrhoea, a PCR detecting enteropathogenic bacteria was performed on the faeces, revealing Y enterocolitica. Following cultures yielded a Y enterocolitica biotype 4, serotype O:3 in the faeces of the girl as well as puppy dog. Despite antibiotic treatment, symptoms and shedding of the organism in the faeces endured during a 2 month period.

Background

The genus of Yersinia consists of 11 species, of which three species are known to cause human disease, Yersinia enterocolitica, Yersina pseudotuberculosis and Yersinia pestis.1 Y enterocolitica is a small facultative anaerobic Gram-negative rod, member of the family of enterobacteriacae; it primarily causes infections of the gastrointestinal tract in humans. Serotypes belonging to O:1, 2, 3; O:2, 3; O:3; O:8; O:9; O:4,32; O:5,27; O:13a,13 have been described as strains causing disease in humans.2 Y enterocolitica is a zoonotic agent, widely dispersed in nature and can be isolated from fresh water samples, food and a wide range of animals, including domestic animals.3 4 Transmission to humans occurs through contaminated food or water. Undercooked or raw pork consumption is the major route of transmission and serotypes that can cause infection in humans can be isolated from the tonsils and alimentary tract of pigs.5 6 Yersinia's ability to grow at temperatures as low as 4°C makes it capable to grow in refrigerators, making refrigerated meat a well-known source of infection. The incidence of Yersinia gastroenteritis in the Netherlands is estimated between 1000 and 10 000 cases annually, with only 200–400 cases being confirmed in the laboratory.7

Here, we report a case of a 1-year-old girl with Y enterocolitica gastroenteritis of which the source was a puppy dog adopted from Spain.

Case presentation

A 1-year-old girl and her mother presented to the emergency ward with a history of 14 days of watery diarrhoea, untill 15 times daily. She had developed a spiking fever up to 39.4°C and abdominal pain. No nausea or vomiting was present at that time. The last 3 days the mother noted blood as well as slime in the girls stool and she was becoming lethargical and somnolent at times. Her appetite had decreased and she weighed 8.2 kg at presentation in contrast to 8.9 kg 2 months ago (weight reduction of 8%). Her medical history reported no previous hospitalisations and no allergies were known. She was born at full-term without any complications. Diarrhoea had started a 3 days after arrival of an adopted puppy dog from Spain which was flown into the Netherlands by an intermediary agency. Child and dog were very close together. The family had not travelled abroad recently. On arrival, this puppy dog had diarrhoea and the girl's mother noted that the smell of the faeces of the dog resembled the smell from the watery feces of her daughter.

Physical examination revealed an alert, heavily crying 1-year-old. She had sunken eyes with a normal turgor of the skin. Examination of the abdomen revealed a non-tender abdomen to palpation. Sporadic peristaltic bowel sounds were heard by auscultation. Further physical examination was unremarkable.

Laboratory testing revealed a haemoglobin level of 7.8 mmol/L (6.3 mmol/L–8.1 mmol/L), white cell count of 11.4×109/L (6×109/L–17.5×109/L), platelet count of 753×109/L (150×109/L–350×109/L) and a normal C reactive protein of 8 mg/L (<10 mg/L). Sodium, potassium, glucose and renal function parameters, creatine and urea were all within normal range.

Differential diagnosis included viral, bacterial and parasitic causes for gastroenteritis. Faecal samples were obtained and a PCR for rotavirus and adenovirus was performed in combination with a PCR for parasitic pathogens (Cryptosporidium parvum, Giardia lambia, Dientamoebe fragilis, Blastocystis hominis). Both results came back negative the next day. At presentation no bacterial culture or PCR for bacterial pathogens causing gastroenteritis was performed. A soy-based diet was advised before sending the girl home and she and her mother were asked to come back for evaluation to the outpatient paediatrics clinic in 1 week.

One week later clinical symptoms endured and diarrhoea was still present in a lower frequency of 4–6 times daily. A PCR for the detection of enteropathogenic bacteria (Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia and Campylobacter) was performed, which became positive for Y enterocolitia. A bacterial culture of the girl’s stool on Cefsulodin–Irgasan–Novobiocin (CIN) selective agar at 30°C for 48 h was performed. Small colourless colonies, without the typical deep red centre or bulls-eye appearance, were cultured on the CIN-agar after 18 h. Vitek-2 bacterial identification and susceptibility testing confirmed the positive result of the PCR with the identification of Y enterocolitica. The subsequently performed agglutination assay showed a serotype O:3.

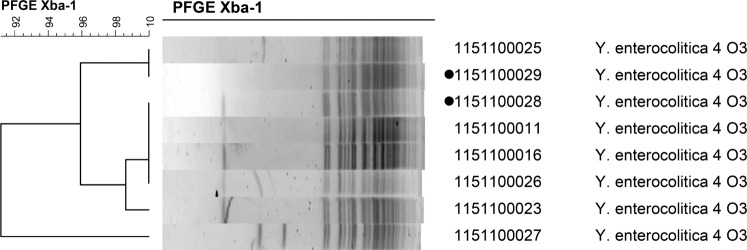

Considering these results and the fact that diarrhoea had started in the girl 3 days after the introduction of a puppy in the household which also had diarrhoea with the same smell as the girl's, we requested a faecal sample of the puppy. A PCR for Y enterocolitica was performed on the feces of the dog which became positive for Y enterocolitica. Culturing the faeces on CIN agar showed identical colourless colonies as in the girl's faeces. The isolated strains of the child and puppy were sent to the reference laboratory in the Netherlands and typed using pulsed field gel electrophoresis (PFGE). The strains were 95% similar by PFGE (figure 1). Y enterocolitica biotype 4, serotype O3 strains from other sources showed limited variation (figure 1). However, both strains were unable to hydrolise cellobiose, a feature 90% of the Y enterocolitica biotype 4 are capable of. This information, combined with the identical biotype and serotype, made the strains highly likely to be related.

Figure 1.

The two isolates with the dots are from the 1-year-old child and puppy dog.

Outcome and follow-up

After 4 weeks of persisting diarrhoea and increasing weight loss, antibiotic treatment with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, to which the isolated Y enterocolitica was susceptible, was started for 5 days. During the antibiotic treatment the girl's overall condition improved within a few days and she regained some weight. Diarrhoea, however, persisted and the course of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole treatment was repeated after which the symptoms gradually improved. PCR and culture performed 7 weeks after presentation at the emergency room remained positive and Y enterocolitica could be isolated from the stool. Finally, after 4 months the PCR and culture became negative. The puppy dog was treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole by a veterinarian and it recovered shortly after. The dog eventually grew too big for the family and was adopted by their neighbours, where it lives untill this day.

Discussion

Here we report a highly probable case of transmission of Y enterocolitica from a pet dog to a 1-year-old girl. We consider transmission highly likely because: (1) the child was healthy prior to the introduction of the pet dog with diarrhoea and diarrhoea in the child developed after introduction of dog, (2) Y enterocolitica isolated from the feces of the puppy and child had the same atypical growth on CIN agar (3) genotyping by PFGE and serotyping revealed identical strains from the pet dog and the child. However, even though transmission between the dog and the girl seems highly probable, the possibility of the dog acquiring Y enterocolitica from the girl cannot be entirely excluded.

Transmission of Y enterocolitica from pet animals has been suggested before.8 In that particular case it was unknown if transmission occurred from the dog to the child or if the child and dog shared the same common source of infection. Furthermore, domestic dogs have been associated with carriership of pathogenic Y enterocolitica strains in China. Y enterocolitica isolated from domestic dogs in China are identical to the Y enterocolitica strains that cause disease in humans suggesting a relation between dogs and transmission of Yersinia in humans.9

The benefit of antibiotic therapy in the treatment of Y enterocolitica gastroenteritis remains unclear. One randomised controlled trial has been performed, evaluating the efficacy of antibiotic treatment of Yersinia gastroenteritis, with no effect on clinical symptoms.10 The majority of cases of gastroenteritis caused by Y enterocolitica are generally mild and self-limiting. Here, the girl was treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, to which the isolate was susceptible. Although clinical symptoms improved, Y enterocolitica persisted in the stool. Persisting shedding of Y enterocolitica with the stool is a known feature of a Yersinia gastroenteritis.11

In conclusion, we report highly probable transmission of Y enterocolitica from a pet dog to a 1-year-old child. The child developed severe diarrhoea which lasted for 2 months after the introduction of a puppy dog from Spain. Antibiotic therapy with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole was not unequivocally successful.

Learning points.

Yersinia enterocolitica is a zoonotic pathogen and a causative agent of gastroenteritis.

Dogs are a potential source of transmission for Y enterocolitica.

Most cases of Yersinia gastroenteritis are self-limiting and the value of antibiotic treatment remains unclear.

Footnotes

Contributors: All authors have contributed significantly to the conception and design, acquisition of data or analysis and interpretation of data drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content. Final approval of the version published.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Bottone EJ. Yersinia enterocolitica: the charisma continues. Clin Microbiol Rev 1997;2013:257–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drummond N, Murphy BP, Ringwood T, et al. Yersinia enterocolitica: a brief review of the issues relating to the zoonotic pathogen, public health challenges, and the pork production chain. Foodborne Pathog Dis 2012;2013:179–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy BP, Drummond N, Ringwood T, et al. First report: Yersinia enterocolitica recovered from canine tonsils. Vet Microbiol 2010;2013:336–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.2005. [FDA] U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Department of Health and Human Services. Foodborne pathogenic microorganisms and natural toxins handbook, Yersinia enterocolitica. http://www.cfsan.fda.gov (accessed 12 Apr 2011)

- 5.Nesbakken T, Eckner K, Hoidal HK, et al. Occurrence of Yersinia enterocolitica and Campylobacter spp. in slaughter pigs and consequences for meat inspection, slaughtering, and dressing procedures. Int J Food Microbiol 2003;2013:231–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Damme I, Habib I, De ZL. Yersinia enterocolitica in slaughter pig tonsils: enumeration and detection by enrichment versus direct plating culture. Food Microbiol 2010;2013:158–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gezondheidsraad Voedselinfecties. The Hague: Dutch Health Council, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilson HD, McCormick JB, Feeley JC. Yersinia enterocolitica infection in a 4-month-old infant associated with infection in household dogs. J Pediatr 1976;2013:767–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Cui Z, Wang H, et al. Pathogenic strains of Yersinia enterocolitica isolated from domestic dogs (Canis familiaris) belonging to farmers are of the same subtype as pathogenic Y. enterocolitica strains isolated from humans and may be a source of human infection in Jiangsu Province, China. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 2013:1604–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pai CH, Gillis F, Tuomanen E, et al. Placebo-controlled double-blind evaluation of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole treatment of Yersinia enterocolitica gastroenteritis. J Pediatr 1984;2013:308–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ostroff SM, Kapperud G, Lassen J, et al. Clinical features of sporadic Yersinia enterocolitica infections in Norway. J Infect Dis 1992;2013:812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]