Abstract

Vaccine-induced T-helper 17 (Th17) cells are necessary and sufficient to protect against fungal infection. Although live fungal vaccines are efficient in driving protective Th17 responses and immunity, attenuated fungi may not be safe for human use. Heat-inactivated formulations and subunit vaccines are safer but less potent and require adjuvant to increase their efficacy. Here, we show that interleukin 1 (IL-1) enhances the capacity of weak vaccines to induce protection against lethal Blastomyces dermatitidis infection in mice and is far more effective than lipopolysaccharide. While IL-1 enhanced expansion and differentiation of fungus-specific T cells by direct action on those cells, cooperation with non-T cells expressing IL-1R1 was necessary to maximize protection. Mechanistically, IL-17 receptor signaling was required for the enhanced protection induced by IL-1. Thus, IL-1 enhances the efficacy of safe but inefficient vaccines against systemic fungal infection in part by increasing the expansion of CD4+ T cells, allowing their entry into the lungs, and inducing their differentiation to protective Th17 cells.

Keywords: IL-1, adjuvant, T-cell priming, vaccine immunity, fungi

Despite the emerging threat of systemic fungal infections worldwide, no commercial antifungal vaccines are now available [1, 2]. This growing medical need has spawned interest in developing such vaccines. Virulence-attenuated mutants induce maximal protection and sterilizing immunity, as demonstrated by the efficacy of experimental vaccines against blastomycosis, histoplasmosis, and coccidiomycosis [3–5]. Vaccine resistance induced by attenuated mutants is chiefly mediated by CD4+ T cells [6–8]; however, even in the absence of CD4+ T-cell help, protective memory CD8+ T cells can be induced and maintained for a long period [9].

Experimental vaccines against candidiasis [10], aspergillosis [11], and the endemic mycoses owe their protection chiefly to induction of T-helper 17 (Th17) and T-helper 1 (Th1) cells [6–8, 12]. Although we have gained valuable knowledge about rational vaccine design from experimental animal models, live attenuated vaccine strains are not likely to be safe in immunocompromised patients. Whereas subunit or heat-inactivated vaccines are safe, they induce minimal or reduced T-cell responses and protection in the absence of adjuvants.

Infections and vaccination with live fungi induce inflammation and the production of proinflammatory cytokines that promote T-cell expansion and differentiation. We asked here whether interleukin 1β (IL-1β), a proinflammatory cytokine known to increase the expansion and differentiation of antigen-specific CD4+ [13] and CD8+ [14] T cells, can augment antifungal resistance conferred by suboptimal but safe vaccine formulations.

IL-1 administered with ovalbumin has been shown to increase the in vivo expansion of antigen-specific T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic (Tg) CD4+ T cells that produce interleukin 17 (IL-17), interleukin 4 (IL-4), or, to a lesser degree, interferon γ (IFN-γ), by direct action on the responding T cells. In addition, already primed Th1, T-helper 2 (Th2), and Th17 cells expanded better in the presence of IL-1 during secondary stimulation. Memory T cells that were primed in the presence of IL-1 retained their differentiated state during a secondary encounter with antigen, compared with T cells primed by antigen alone. Similarly, CD8+ T cells primed in the presence of IL-1 showed augmented expansion and enhanced expression of granzyme B and IFN-γ and greater cytotoxic activity; these cells retained their expanded numbers and differentiated state when rechallenged 2 months after priming, even if IL-1 was not readministered [14]. Interestingly, trafficking to or retention of primed T cells in the periphery (lung and liver), as well as their increased expression of granzyme B and IFN-γ, required IL-1R1 expression in cells other than antigen-specific T cells.

IL-1 administered with heat-killed Listeria monocytogenes resulted in enhanced resistance to subsequent challenge with live L. monocytogenes [14]. To our knowledge, IL-1 has not been tested as an adjuvant for vaccine-induced resistance to fungal infection, a condition for which no commercial vaccines are available and the immunogenicity of existing formulations is generally suboptimal. Moreover, the capacity of IL-1 to preferentially enhance differentiation to Th17 cells suggests it could have particular value in inducing resistance to fungal infection.

Here, we asked several questions: Does IL-1 augment resistance against B. dermatitidis infection conferred by an inefficient heat-inactivated vaccine or its crude cell wall/membrane extract? If so, how does IL-1 mediate its adjuvant effect: directly on T cells, by innate cells, or both? What roles are played by fungus-specific Th17 cells and IL-17 receptor signaling during the adjuvant effect of IL-1? We report that IL-1 adjuvant significantly enhances the resistance mediated by weak vaccines against fungi and does so in a manner that promotes the development of Th17 cells and requires signaling via IL-17R and the contribution of non-T cells that express IL-1R1 for maximal protection.

METHODS

Mouse Strains

Inbred strains of C57BL/6 mice (sex, female; age, 7–8 weeks at the time of experiments) were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Blastomyces-specific TCR Tg 1807 mice were generated in our laboratory and backcrossed to congenic Thy1.1+ mice as described elsewhere [15, 16]. TCR Tg OT-II/RAG1−/− C57BL/6 mice and TCR Tg OT-II/RAG1−/− IL-1R1−/− C57BL/6 mice were obtained from Taconic farms. Breeder pairs for IL-17RA−/− mice [17] were provided by Amgen. Mice were housed and cared for according to guidelines of the University of Wisconsin Animal Care Committee, which approved all aspects of this work.

Fungi and Growth Conditions

Strains used were American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) 26199, a wild-type virulent strain, and the isogenic, attenuated mutant lacking BAD1, designated strain 55 [18]. Isolates of B. dermatitidis were maintained as yeast on Middlebrook 7H10 agar with oleic acid-albumin complex (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) at 39°C.

Vaccinations With Blastomyces Cell-Wall Membrane (CW/M) Extract and Heat-Killed Yeast

Unless otherwise stated, C57BL/6 mice were vaccinated subcutaneously twice 2 weeks apart at 2 sites, dorsally and at the base of the tail, as follows. BAD1-null attenuated yeast cells [18] were injected as live or heat-killed cells, using a dose range of 104 to 106 yeast per mouse. Soluble cell-wall membrane (CW/M) extract (100 µg/mouse) was emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant. In some experiments, 25 µg of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from Escherichia coli 0111:B4 (InvivoGen) was injected subcutaneously together with vaccine yeast. IL-1β that was prepared as described elsewhere [19] was injected subcutaneously daily (2 µg/injection) for 5 consecutive days, starting with the day of immunization; this regimen was repeated 2 weeks later (booster).

Adoptive Transfer of Transgenic 1807 T Cells and Surface Staining

Single-cell suspensions (106 cells) from 1807 TCR Tg Thy 1.1+ mice were injected intravenously into wild-type Thy 1.2+ C57BL/6 male recipients. Single-cell suspensions from draining inguinal and brachial lymph nodes and lung cells of recipient mice were stained with monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) directed against surface markers: CD4, CD8, Thy1.1, CD44, CD62L, and B220 (as a dump marker). mAbs were obtained from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA) and eBioscience (San Diego, CA), and cytometry data were gathered with a LSRII (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA). Data were analyzed by using FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR). The number of 1807 CD4+ T cells per lung was calculated by multiplying the percentage of Thy 1.1+ CD4+ cells by the number of viable cells as determined by trypan blue dye exclusion.

Intracellular Cytokine Staining

Lung and draining lymph node cells were obtained as described elsewhere [4]. An aliquot of isolated cells was stained for surface CD4 and Thy 1.1 to determine the percentage of transferred 1807 cells. The number of 1807 cells in the lung and lymph node were derived by multiplying the percentage of cells by the total number of cells per organ isolated. The remaining cells were stimulated with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 mAbs. After 4–6 hours, cells were stained for surface markers, fixed, permeabilized in Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Pharmingen), and stained with anti-cytokine antibodies as described elsewhere [20, 21].

Experimental Infection

Mice were infected intratracheally with 2 × 103 wild-type yeast of strain ATCC 26199 as described elsewhere [3]. On day 4 after infection, coinciding with the peak of T-cell influx [4, 6], the mice were euthanized, and lung T cells were analyzed by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Differences in the number and percentage of activated, proliferating, or cytokine-producing T cells and in the number of lung colony-forming units (CFU), were analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank test, for nonparametric data [22], or the t test, when data were normally distributed. A P value of < .05 is considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Recombinant IL-1 Augments Vaccine Resistance to B. dermatitidis Infection

We tested whether IL-1 enhances vaccine resistance against fungi by using an experimental model of lethal infection with the systemic dimorphic fungus B. dermatitidis. We engineered a live attenuated vaccine that induces sterilizing immunity in response to challenge with virulent, wild-type yeast [3]. To explore the IL-1 adjuvant effect, we used heat-killed yeast as a vaccine and compared the results to those obtained with the live attenuated yeast.

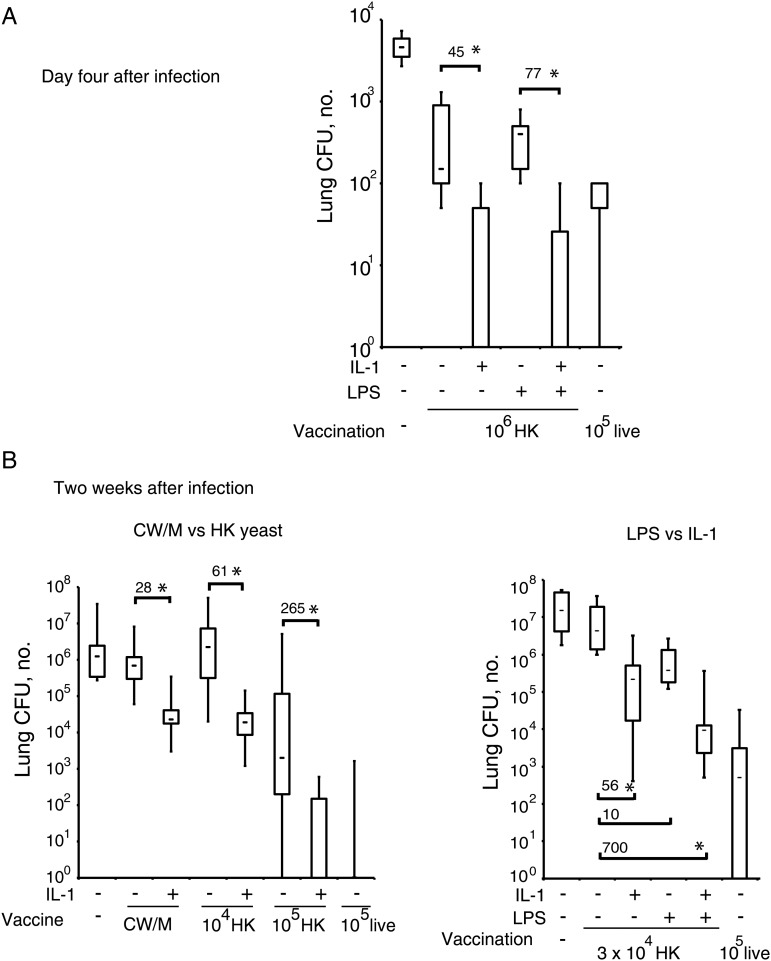

Mice were vaccinated with 104–106 heat-killed yeast with or without LPS (25 µg) or with 200 µg of a crude CW/M extract emulsified in complete Freund's adjuvant, as described elsewhere [3]. Some vaccinated mice received IL-1 for 5 days during immunization and boosting. IL-1 enhanced vaccine resistance induced by CW/M and by heat-killed yeast by up to 2–3 logs in several experiments, whereas LPS had a very limited effect in enhancing the protective value of either CW/M or heat-killed yeast (Figure 1A and 1B). Indeed, when examined 2 weeks after infection, 105 HK yeast plus IL-1 was almost as effective as the same dose of live attenuated yeast. Although LPS adjuvant had minimal benefit when administered alone, it often exerted an additive effect when combined with IL-1 (Figure 1A and 1B).

Figure 1.

Recombinant interleukin 1 (IL-1) treatment augments vaccine resistance against Blastomyces dermatitidis infection. Mice were vaccinated with Blastomyces cell-wall membrane (CW/M) antigen, heat-killed yeast, or live yeast (as a positive control) with our without exogenous, recombinant IL-1β and/or lipopolysaccharide. Two weeks after the booster, mice were challenged with virulent, wild-type yeast. The number of lung colony-forming units (CFU) was enumerated on day 4 after infection, when T–cell responses were analyzed (n = 4–6 mice/group; A), or after 14 days after infection, when mice were moribund (n = 8–12 mice/group; B). Data are mean ± standard error of the mean. Numbers depict fold-difference in CFU vs control; *P < .05.

The IL-1 Adjuvant Effect Is Chiefly Mediated by T Cells

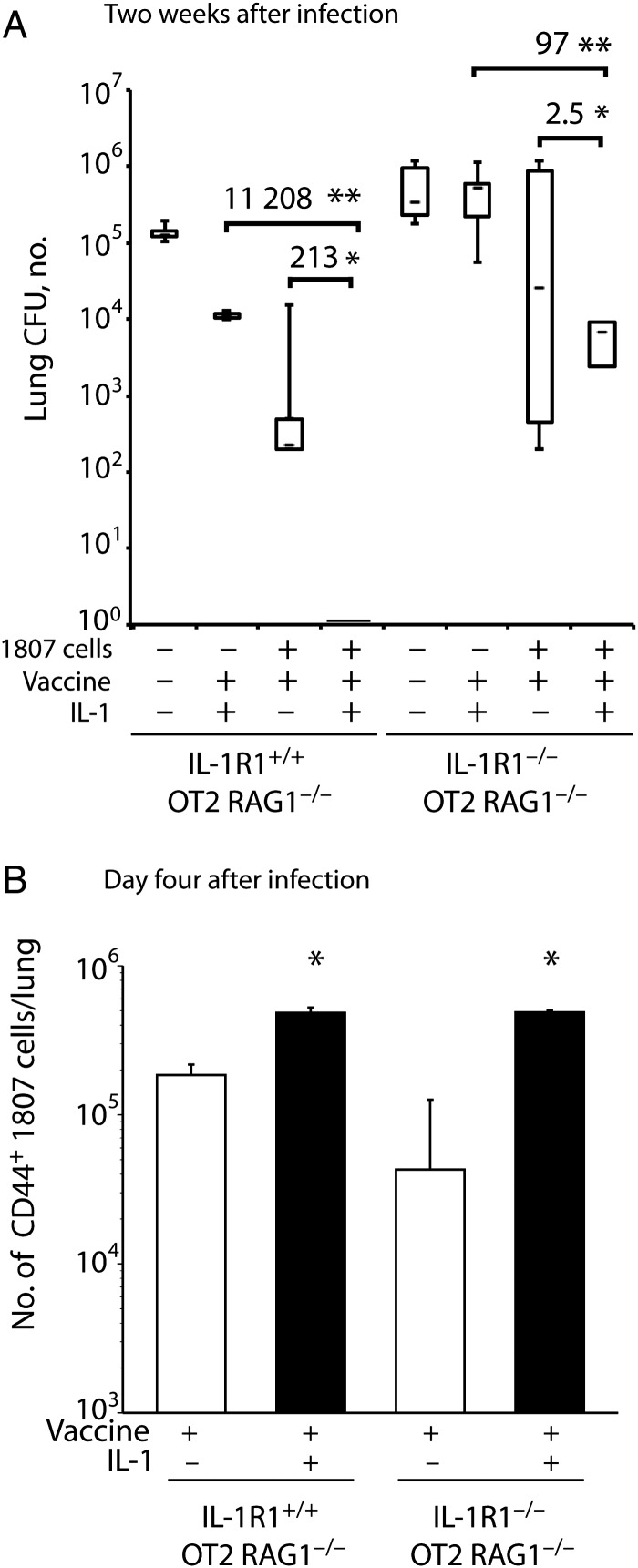

Since T cells are principally responsible for mediating vaccine-induced immunity to fungi [23], we asked whether T cells are the major target of IL-1. We transferred naive 1807 TCR Tg CD4+ T cells specific for B. dermatitidis into IL-1R1+/+ OT2 RAG1−/− and IL-1R1−/− OT2 RAG1−/− mice, which lack endogenous polyclonal T cells, and vaccinated the recipients with or without IL-1. Two weeks after infection, when the unvaccinated mice were moribund, the number of lung CFU was 11 208-fold lower in vaccinated, IL-1–treated IL-1R1+/+ mice, compared with IL-1–treated vaccinated controls that did not receive 1807 cells (Figure 2A), indicating the importance of antigen-specific T cells in vaccine-mediated protection. IL-1 treatment increased the number of activated, CD44+ 1807 cells recruited to the lungs of both IL-1R1+/+ and IL-1R1−/− strains of vaccinated mice (Figure 2B) and reduced the number of lung CFU by 213-fold in vaccinated IL-1R1+/+ mice, compared with vaccinated 1807 recipients that did not receive IL-1 (Figure 2A). Thus, adoptively transferred 1807 cells mediated vaccine immunity in this experimental system, and IL-1 significantly augmented the vaccine effect.

Figure 2.

The interleukin 1 (IL-1) adjuvant effect is principally mediated by T cells. A and B, IL-1 R1+/+ OT2 RAG1−/− and IL-1R1−/− OT2 RAG1−/− mice received 106 naive 1807 transgenic cells intravenously (or no cells as a control) and were vaccinated with 106 heat-killed yeast with or without exogenous, recombinant IL-1β. Two weeks after the boost, mice were challenged with virulent wild-type yeast. A, The number of lung colony-forming units (CFU) 2 weeks after infection. Data are the mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 4–7 mice/group). Numbers depict fold differences in CFU. *P < .05 vs no IL-1 treatment; **P < .05 vs no transfer of 1807 cells. B, The number of activated (CD44+) 1807 cells in the lung 4 days after infection. *P < .05 vs no IL-1 treatment.

The expansion and migration of 1807 cells to the lung did not require the expression of IL-1R1 on non-T cells, since IL-1 treatment led to similar numbers of 1807 cells in the lungs of vaccinated IL-1R1+/+ and IL-1R1−/− mice (Figure 2B). Without the addition of IL-1, 1807 cell numbers in the lung were fewer in the IL-1R-/- recipients than in wild-type recipients, implying that endogenous IL-1 acting on non-T cells played a role in the migration of these cells when specific T cell numbers were low.

IL-1R1 expression on non-T cells was required for optimal protection by 1807 cells primed in the presence of IL-1. IL-1–treated IL-1R1−/− recipients of 1807 cells showed only 2.5-fold fewer lung CFU, compared with untreated controls, whereas IL-1–treated IL-1R1+/+ recipients showed 213-fold less lung CFU, compared with untreated controls. Similarly, the transfer of 1807 cells reduced lung CFU less in IL-1R1−/− mice (by 97-fold) than in IL-1R1+/+ mice (by 11 208-fold) vaccinated with IL-1 adjuvant, implying that IL-1R1 expression on endogenous cells is important in protection afforded by vaccine. Thus, IL-1 acts directly on 1807 cells to increase their response to vaccine and their entry into the lung, but IL-1R1+ non-T cells are required to promote optimal adjuvant efficacy.

IL-1 Augments the Recruitment of Antifungal Th17 Cells to the Lung Upon Recall

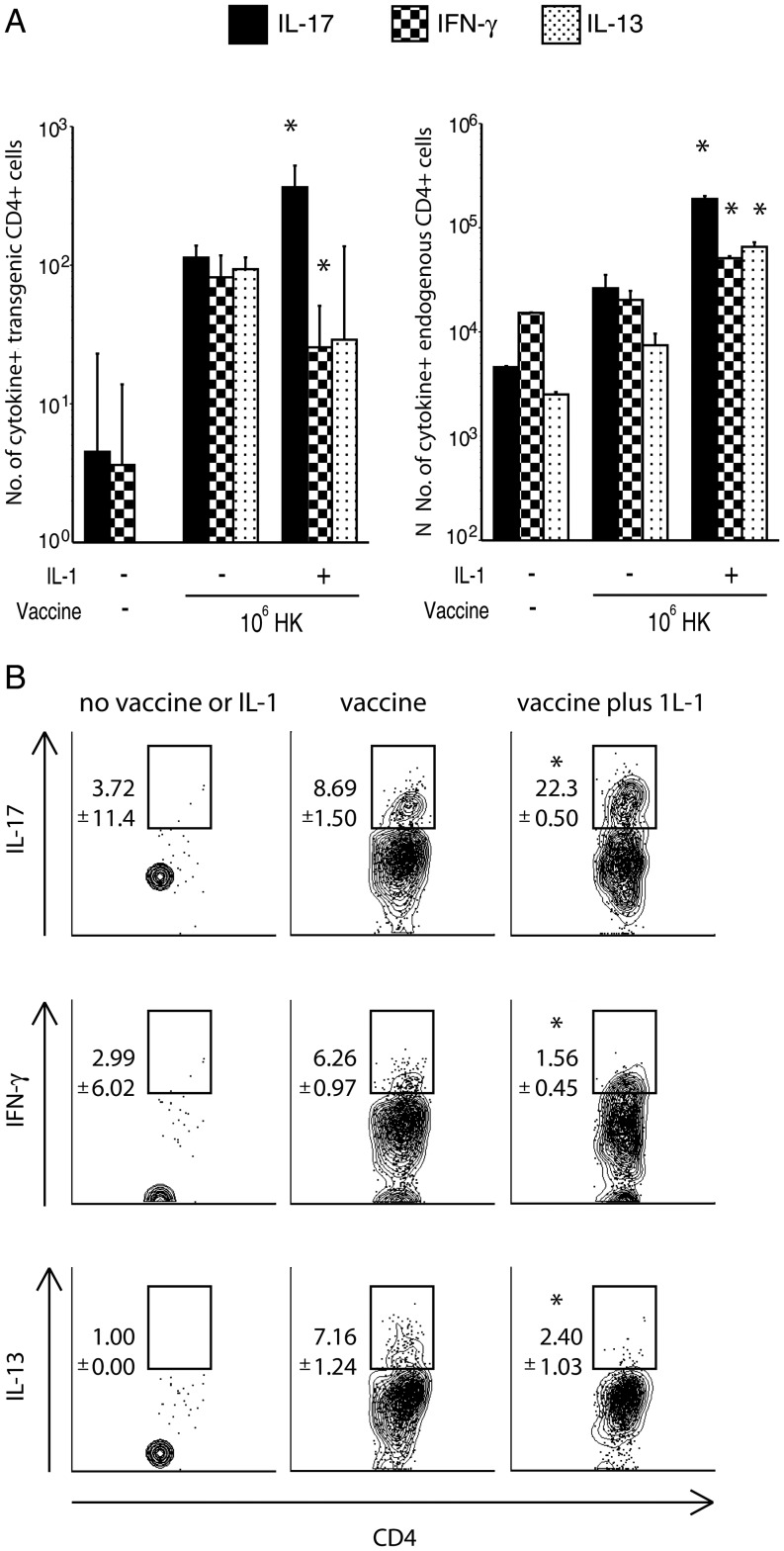

The development of vaccine-induced Th17 cells is necessary and sufficient to protect against systemic dimorphic fungi [12]. To see whether vaccination in the presence of IL-1 increases the frequency and number of IL-17–producing fungus-specific T cells, we enumerated cytokine-producing 1807 cells in the lung upon recall. IL-1 adjuvant increased the frequency and number of IL-17+ 1807 cells and reduced the frequency and number of both IFN-γ and interleukin 13 (IL-13)+ antigen-specific 1807 cells recruited to the lung (Figure 3A and 3B). IL-1 also increased the frequency of IL-17–producing endogenous CD4+ T cells; however, endogenous IFN-γ and IL-13 producers also increased in frequency when IL-1 was administered (Figure 3A and data not shown). IL-1 also increased the percentage and numbers of activated (CD44+) 1807 cells (data not shown). Thus, IL-1 increased the expansion of fungus-specific 1807 cells and enhanced the Th17 response.

Figure 3.

Interleukin 1 (IL-1) adjuvant increases the recruitment of antifungal T-helper 17 cells into the lung upon recall. A and B, The number (A) and percentage (B) of cytokine-producing 1807 transgenic and endogenous CD4+ T cells (A) that migrated to the lung at day 4 after infection are shown. Mice received 106 adoptively transferred naive 1807 cells intravenously and were vaccinated with 106 heat-killed yeast or 105 live yeast (as a positive control) with or without recombinant IL-1β. Two weeks after the boost, mice were challenged with virulent wild-type yeast, and the number of cytokine-producing T cells was enumerated by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 4–6 mice/group) and are representative of 2 experiments. *P < .05 vs all other groups. Abbreviations: IFN-γ, interferon γ; IL-13, interleukin 13; IL-17, interleukin 17.

The IL-1 Adjuvant Effect Requires IL-17 Signaling

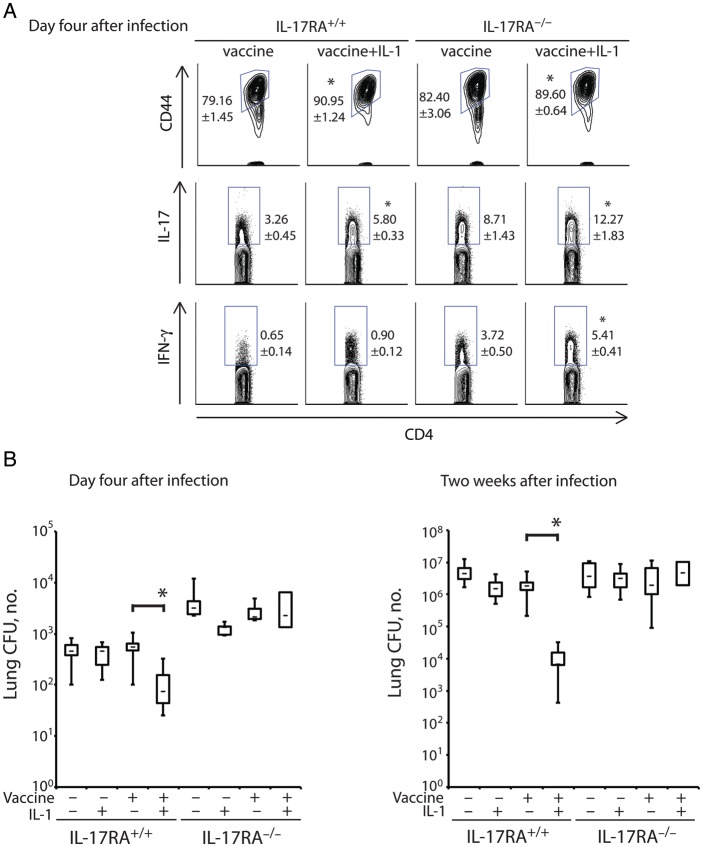

Since IL-1 increased the number of Th17 cells present in the lung upon challenge (Figure 3), we investigated whether the production of IL-17 is required for the vaccine-enhancing effect of IL-1. To do so, we vaccinated IL-17RA−/− mice, in which IL-17 cannot signal via its receptor to mediate its effector functions [12]. We previously reported that Th17 and Th1 cell development and migration to the lung are not impaired in the absence of IL-17R signaling [12]. Here, we first analyzed how IL-1 affected the Th17 and Th1 phenotypes of lung CD4+ T lymphocytes in IL-17RA−/− mice. Four days after infection, the proportion of activated (CD44+) and IL-17+ endogenous CD4+ T cells recalled to the lung were similarly increased in vaccinated IL-17RA−/− and wild-type mice that received IL-1 (Figure 4A). The frequencies of IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells increased significantly in IL-1–treated, vaccinated IL-17RA−/− mice but not in wild-type control mice. Thus, IL-1 increased the development and recruitment of Th17 and Th1 cells to the lungs of vaccinated IL-17RA−/− mice.

Figure 4.

The interleukin 1 (IL-1) adjuvant effect on antifungal vaccination requires interleukin 17 (IL-17) receptor signaling. Wild-type and IL-17RA−/− mice were vaccinated with 3 × 104 heat-killed yeast with or without recombinant IL-1β. Two weeks after the boost, mice were challenged with virulent wild-type yeast. A, On day 4 after infection, the frequency of CD44+ and cytokine-producing endogenous CD4+ cells was determined by fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis. *P < .05 vs no IL-1 treatment of the corresponding vaccinated group. B and C, On day 4 (B) or 2 weeks (C) after infection, the number of lung colony-forming units (CFU) was analyzed. Data are mean ± standard error of the mean (n = 8–12 mice/group). *P < .05 vs no IL-1 treatment of the corresponding vaccinated group. Abbreviation: IFN-γ, interferon γ.

To see whether IL-1 mediates its adjuvant effect in a manner that requires IL-17 receptor signaling, we gave IL-17RA−/− and wild-type mice a low vaccine dose (3 × 104 heat-killed yeast) that itself engenders little or no resistance, to leave “room” to observe an adjuvant effect. Both 4 days and 2 weeks after infection, IL-1 treatment reduced the numbers of lung CFU significantly in vaccinated wild-type mice but not in IL-17RA−/− mice (Figure 4B and 4C). Thus, IL-1 requires IL-17 receptor signaling to exert its action in enhancing vaccine immunity against B. dermatitidis infection.

DISCUSSION

Here, we report that IL-1 augmented the protective efficacy of weak antifungal vaccines. We observed that IL-1 given together with a heat-inactivated, whole-yeast vaccine or with a cell-wall membrane extract made from the yeast reduced the number of lung CFU by 1–2 log10, compared with values for vaccinated controls that did not receive IL-1. The adjuvant effect of LPS was smaller than that of IL-1, but together the effects were often additive. In previous work, it was shown that the addition of IL-1 to a heat-killed L. monocytogenes vaccine yielded a 2-log10 reduction in the number of liver CFU upon challenge with live L. monocytogenes, compared with vaccination with heat-killed L. monocytogenes alone [14]. Similarly, IL-1 given with a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) peptide vaccine increased protection to a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the HIV peptide by 1 log10, compared with the peptide alone, and enhanced the efficacy of a peptide vaccine against a tumor expressing that peptide [14].

In the experimental bacterial and viral systems noted above, the mechanism through which IL-1 mediated its adjuvant effect was not determined, whereas the antifungal resistance observed here rested chiefly on CD4+ T cells. This conclusion is supported by our use of adoptively transferred 1807 TCR Tg T cells. IL-1R1+/+ OT2 RAG1−/− recipients of 1807 cells that were vaccinated in the presence of IL-1 had >4-log10 fewer lung CFU than did comparable controls that had not received 1807 cells. However, optimal protection mediated by 1807 cells and IL-1 also required the expression of IL-1R1 on cells other than responding TCR transgenic T cells. For example, while IL-1 augmented vaccine protection by 213-fold in IL-1R1+/+ mice (compared with nontreated controls), the number of lung CFU was only reduced 2.5-fold by IL-1 in IL-1R1−/− recipients.

The number of activated (CD44+) 1807 cells detected in the lungs after challenge was increased similarly in vaccinated IL-1R1+/+ and IL-1R1−/− mice treated with IL-1. These results imply that IL-1 enhanced the activation and expansion of 1807 cells and their migration to the lungs comparably in vaccinated IL-1R1+/+ and IL-1R1−/− mice. Thus, IL-1R1 expression on non-T cells was not required to recruit primed 1807 cells to the lung, and failed recruitment thus does not explain reduced resistance in IL-1R1−/− recipients. The lack of a trafficking deficit by 1807 cells contrasts with CD8+ OT-I cells that failed to accumulate in the liver and lung after priming with subcutaneously delivered ovalbumin and LPS in IL-1R1−/− mice [14]. This difference may be due the greater amounts of inflammation in mice given the intratracheal challenge with live yeast, compared with that in mice immunized with ovalbumin subcutaneously, or may reflect differences in trafficking behavior of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells.

In wild-type recipient mice, priming of 1807 cells in the presence of IL-1 markedly altered their T-helper phenotype. Fungal pathogen-associated molecular patterns such as β-glucan [24] and mannans [25] can promote differentiation of naive T cells into Th17 cells. However, the frequency and number of cells capable of producing IL-17 upon in vivo challenge increased with IL-1, whereas the frequency of cells capable of producing IFN-γ or IL-4 decreased. Unfortunately, we had too few IL-1R1−/− OTII RAG1−/− mice available to assess the T-helper phenotype of transferred 1807 cells in these recipients. It is conceivable that IL-1R1 expression of endogenous cells other than T cells is necessary to generate Th17 cells, although that is unlikely because IL-1 can directly act on ovalbumin-specific CD4+ T cells to enhance the frequency of IL-17–producing cells. On the other hand, differentiation of CD8+ T cells to become high-level IFN-γ–producers and express large amounts of granzyme B requires expression of IL-1R1 on cells other than the responding T cells. For example, CD8+ OT-I cells required the expression of IL-1R1 on non-T cells to induce granzyme B expression, antigen-specific cytotoxic T-cell activity, and production of IFN-γ [14]. Logical target cells for IL-1 in this model are dendritic cells [26, 27].

In a nasal vaccination model of Bacillus anthracis, IL-1 activated stromal cells to produce IL-6 [27]. Thus, it is possible that IL-1 adjuvant could have enhanced differentiation during the priming of naive 1807 cells into Th17 cells in IL-1R1+/+ mice but not in IL-1R1−/− recipients. On the other hand, the capacity of IL-1 to enhance the expansion of antigen-specific CD4+ T cells does not depend on IL-6 since it can be achieved in IL-6–deficient recipients [13].

Highly differentiated T cells that have been primed in the presence of IL-1 retain the capacity to produce elevated levels of cytokine and granzyme B upon rechallenge >4 weeks after priming without readministration of IL-1 [14]. While our study does not pinpoint the timing and mechanism by which IL-1R1–expressing non-T cells contribute to the optimal IL-1 adjuvant effect, it reveals that the protective value of IL-1 (but not its capacity to cause expansion of responding cells) requires action on non-T cells, as well as the responding CD4+ T cells.

Our study establishes that the generation of vaccine-induced Th17 cells is crucial for the IL-1 adjuvant effect for protection against challenge with Blastomyces organisms. Vaccinated IL-17RA−/− mice did not acquire resistance in response to IL-1 treatment, while vaccinated IL-17RA+/+ mice reduced the number of lung CFU by 1–2 log10, compared with the value in controls vaccinated without IL-1. This study reinforces the beneficial role that Th17 cells can exert during vaccine immunity despite debate about the possible tissue-damaging influence of inflammation mediated by Th17 cells [28].

In summary, our proof of principle study demonstrates that IL-1 has the capacity to enhance vaccine resistance against fungi, here studied in a model of lethal infection with the systemic fungal pathogen B. dermatitidis. IL-1 promotes the differentiation of fungus-specific Th17 cells that are essential for the adjuvant and vaccine effects while also reducing the generation of antigen-specific Th1 and Th2 cells. Untoward, potent proinflammatory effects will need to be studied to mitigate IL-1 toxicity in the clinical setting. Since fungal glycans have the inherent capacity to induce generation of Th17 cells, perhaps less IL-1 may be sufficient to confer vaccine-induced protection when used together with Th17 cell–promoting fungal ligands or even small amounts of alum as an approved adjuvant, because it also induces IL-1 [13, 29]. In addition, the pyrogenic activity of IL-1 and local inflammation could be reduced in humans by using nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, which do not affect the immunological properties of IL-1 [30].

Notes

Acknowledgments. We thank Drs Jens Eickhoff and Chong Zhang (Department of Biostatistics and Medical Informatics, University of Wisconsin–Madison), for performing the statistical analysis, and Robert Gordon, for graphical support.

Financial support. This work was supported by that National Institutes of Health (NIH; grants R01 AI093553 [to M. W.] and R01 AI40996 [to B. K.]) and the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH (to W. E. P.).

Potential conflicts of interest. All authors: No reported conflicts.

All authors have submitted the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest. Conflicts that the editors consider relevant to the content of the manuscript have been disclosed.

References

- 1.Deepe GS., Jr Preventative and therapeutic vaccines for fungal infections: from concept to implementation. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2004;3:701–9. doi: 10.1586/14760584.3.6.701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cutler JE, Deepe GS, Jr, Klein BS. Advances in combating fungal diseases: vaccines on the threshold. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:13–28. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wüthrich M, Filutowicz HI, Klein BS. Mutation of the WI-1 gene yields an attenuated Blastomyces dermatitidis strain that induces host resistance. J Clin Invest. 2000;106:1381–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI11037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wüthrich M, Filutowicz HI, Warner T, Deepe GS, Jr, Klein BS. Vaccine immunity to pathogenic fungi overcomes the requirement for CD4 help in exogenous antigen presentation to CD8+ T cells: implications for vaccine development in immune-deficient hosts. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1405–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xue J, Chen X, Selby D, Hung CY, Yu JJ, Cole GT. A genetically engineered live attenuated vaccine of Coccidioides posadasii protects BALB/c mice against coccidioidomycosis. Infect Immun. 2009;77:3196–208. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00459-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wüthrich M, Filutowicz HI, Warner T, Klein BS. Requisite elements in vaccine immunity to Blastomyces dermatitidis: plasticity uncovers vaccine potential in immune-deficient hosts. J Immunol. 2002;169:6969–76. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.12.6969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allendorfer R, Brunner GD, Deepe GS., Jr Complex requirements for nascent and memory immunity in pulmonary histoplasmosis. J Immunol. 1999;162:7389–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hung CY, Gonzalez A, Wüthrich M, Klein BS, Cole GT. Vaccine immunity to coccidioidomycosis occurs by early activation of three signal pathways of T helper cell response (Th1, Th2, and Th17) Infect Immun. 2011;79:4511–22. doi: 10.1128/IAI.05726-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nanjappa SG, Heninger E, Wüthrich M, Sullivan T, Klein B. Protective antifungal memory CD8+ T cells are maintained in the absence of CD4+ T cell help and cognate antigen in mice. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:987–99. doi: 10.1172/JCI58762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin L, Ibrahim AS, Xu X, et al. Th1-Th17 cells mediate protective adaptive immunity against Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans infection in mice. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000703. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Diaz-Arevalo D, Bagramyan K, Hong TB, Ito JI, Kalkum M. CD4+ T cells mediate the protective effect of the recombinant Asp f3-based anti-aspergillosis vaccine. Infect Immun. 2011;79:2257–66. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01311-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wüthrich M, Gern B, Hung CY, et al. Vaccine-induced protection against 3 systemic mycoses endemic to North America requires Th17 cells in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:554–68. doi: 10.1172/JCI43984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ben-Sasson SZ, Hu-Li J, Quiel J, et al. IL-1 acts directly on CD4 T cells to enhance their antigen-driven expansion and differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:7119–24. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902745106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ben-Sasson SZ, Hogg A, Hu-Li J, et al. IL-1 enhances expansion, effector function, tissue localization and memory response of antigen-specfic CD8 T cells. J Exp Med. 2013;210:491–502. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wüthrich M, Ersland K, Sullivan T, Galles K, Klein BS. Fungi subvert vaccine T cell priming at the respiratory mucosa by preventing chemokine-induced influx of inflammatory monocytes. Immunity. 2012;36:680–92. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wüthrich M, Hung CY, Gern BH, et al. A TCR transgenic mouse reactive with multiple systemic dimorphic fungi. J Immunol. 2011;187:1421–31. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye P, Rodriguez FH, Kanaly S, et al. Requirement of interleukin 17 receptor signaling for lung CXC chemokine and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor expression, neutrophil recruitment, and host defense. J Exp Med. 2001;194:519–27. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Brandhorst TT, Wüthrich M, Warner T, Klein B. Targeted gene disruption reveals an adhesin indispensable for pathogenicity of Blastomyces dermatitidis. J Exp Med. 1999;189:1207–16. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.8.1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wingfield P, Payton M, Graber P, et al. Purification and characterization of human interleukin-1 alpha produced in Escherichia coli. Eur J Biochem. 1987;165:537–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1987.tb11472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wüthrich M, Fisette PL, Filutowicz HI, Klein BS. Differential requirements of T Cell subsets for CD40 costimulation in immunity to Blastomyces dermatitidis. J Immunol. 2006;176:5538–47. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.9.5538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wüthrich M, Warner T, Klein BS. IL-12 is required for induction but not maintenance of protective, memory responses to Blastomyces dermatitidis: implications for vaccine development in immune-deficient hosts. J Immunol. 2005;175:5288–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher LD, van Belle G. Biostatistics: a methodology for the health sciences. New York: John Wiley; 1993. pp. 611–3. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wüthrich M, Deepe GS, Jr, Klein B. Adaptive immunity to fungi. Annu Rev Immunol. 2012;30:115–48. doi: 10.1146/annurev-immunol-020711-074958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LeibundGut-Landmann S, Gross O, Robinson MJ, et al. Syk- and CARD9-dependent coupling of innate immunity to the induction of T helper cells that produce interleukin 17. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:630–8. doi: 10.1038/ni1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saijo S, Ikeda S, Yamabe K, et al. Dectin-2 recognition of alpha-mannans and induction of Th17 cell differentiation is essential for host defense against Candida albicans. Immunity. 2010;32:681–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wesa A, Galy A. Increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and enhanced T cell responses after activation of human dendritic cells with IL-1 and CD40 ligand. BMC Immunol. 2002;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2172-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson AL, Johnson BT, Sempowski GD, et al. Maximal adjuvant activity of nasally delivered IL-1alpha requires adjuvant-responsive CD11c(+) cells and does not correlate with adjuvant-induced in vivo cytokine production. J Immunol. 2012;188:2834–46. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zelante T, De Luca A, Bonifazi P, et al. IL-23 and the Th17 pathway promote inflammation and impair antifungal immune resistance. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2695–706. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eisenbarth SC, Colegio OR, O'Connor W, Sutterwala FS, Flavell RA. Crucial role for the Nalp3 inflammasome in the immunostimulatory properties of aluminium adjuvants. Nature. 2008;453:1122–6. doi: 10.1038/nature06939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dinarello CA. Biologic basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87:2095–147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]