Abstract

Detection of diaphragmatic hernia in the acute setting is problematic and diagnosing diaphragmatic hernia as hydropneumothorax is not an uncommon mistake. We present a series of four such cases diagnosed over a 7-year period, from December 2004 to January 2011 and analyse them for how this mistake can be avoided. In case of all the patients reported by us the initial radiographs were technically compromised because the patient could not be positioned properly. Also they were examined by non-radiologists. We feel that treating surgeons in emergency department tend to overdiagnose pneumothorax as it is a life-threatening condition. We feel that in the appropriate setting suspicion of diaphragmatic hernia should be raised in patients having fractured ribs associated with homogenous opacity, which cannot be differentiated from the diaphragm. Evidence of loculation of hydropneumothorax in the appropriate setting should also raise the possibility of diaphragmatic hernia.

Background

The incidence of diaphragmatic rupture varies from 0.8% to 8% following major blunt trauma.1 Their detection in the acute setting is problematic because specific clinical signs are usually not evident and there is high frequency of associated injuries. Late recognition of this injury has been reported in 14–15% of cases and the delay in diagnosis from 20 days to 28 years.2

Diagnosing a diaphragmatic hernia as hydropneumothorax on radiographs is not an uncommon mistake and is well identified in the literature as occurring in the acute and chronic setting.3 4 We report four such cases which were diagnosed as pneumothorax initially and treated with chest tube drainage but were later found to have diaphragmatic rupture on CT scan.

Case presentation

Case 1

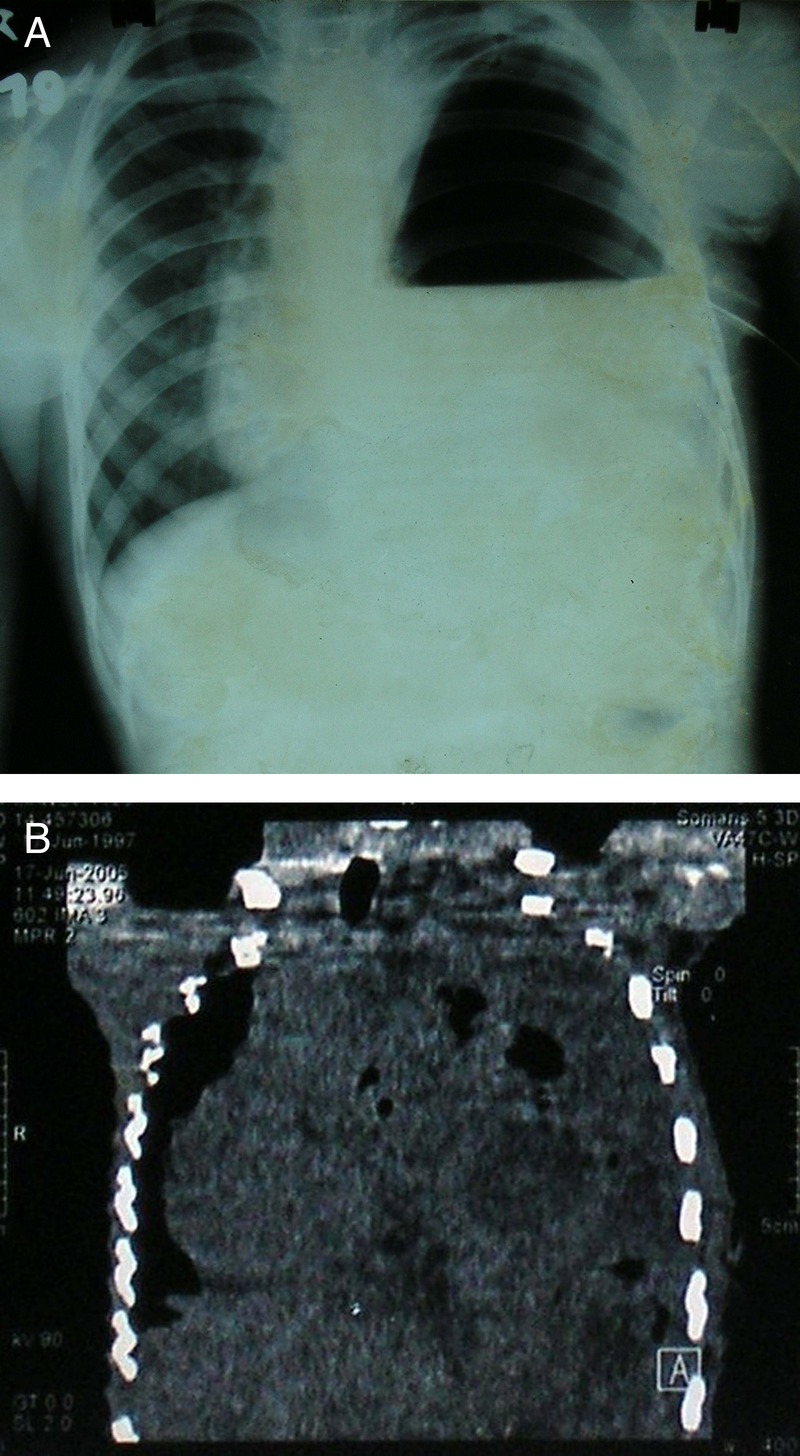

An 8-year-old child presented with a history of pain in the left side of chest of 1 day duration. On examination the child appeared to be in mild respiratory distress with reduced breath sounds on the left side. Respiratory rate was 28/min. On chest radiography there was hydropneumothorax with collapse of the underlying lung (figure 1A). Ultrasound examination also revealed features of hydropneumothorax. A preliminary treatment with chest tube insertion was made. However, the patient gave a history of passing food through it. A non-contrast CT scan revealed hydropneumothorax with fluid-filled cystic structures in the left hemithorax with some pockets of air within it (figure 1B). The patient was operated and stomach, colon and part of spleen were found herniating through a rent in the posterolateral part of the left hemidiaphragm. On probing the child gave a history of diving in a pool 2 days before admission.

Figure 1.

(A) Radiograph of the chest posteroanterior view reveals a large air-fluid level in the left hemithorax with collapsed lung lying in the region of the left upper zone. There is mild mediastinal shift. (B) Coronal reformation of non-contrast CT scan reveals an ill-defined solid cystic mass lesion with loculated pockets of air within. A diaphragmatic hernia was suspected and a Barium meal confirmed the diagnosis.

Case 2

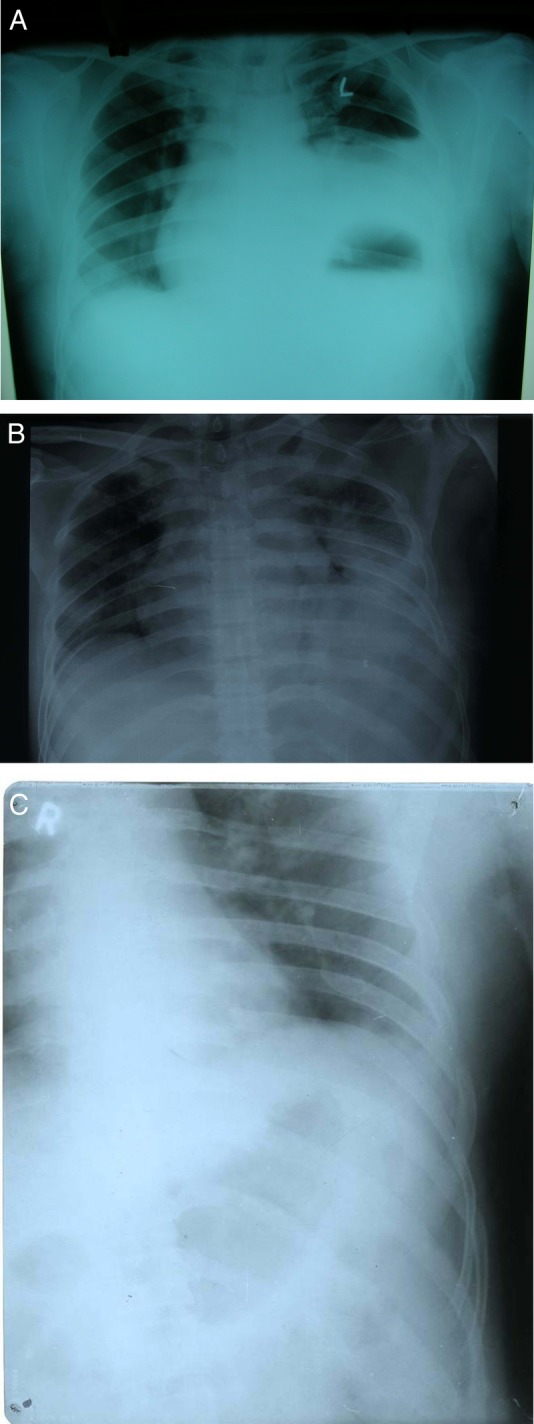

A 45-year-old man presented 7 days following a road accident. On presentation he reported difficulty in breathing with reduced breath sounds on the left side. General physical examination was otherwise normal. A chest radiograph revealed air-fluid level on the left side with collapse of underlying lung. Gastric air bubble was at a higher level and there was mediastinal shift to the right side. There was also fracture of the fifth and sixth rib on the left side (figure 2A). A diagnosis of hydropneumothorax was made and chest tube drainage was performed. However, there was no expulsion of air. A repeat radiograph revealed a homogenous opacity in the left lower lobe and minimal pleural effusion (figure 2B). Left diaphragm was not seen separate from this opacity raising the suspicion of diaphragmatic hernia. A CT scan was performed and it revealed herniation of stomach and omentum on the left side. The chest tube was lodged in the omentum. The radiograph performed immediately after the accident had revealed only mild left-sided pleural effusion (figure 2C).

Figure 2.

(A) Radiograph of the chest posteroanterior view reveals raised left hemidiaphragm with a large air-fluid level in the region of the left lower field. There was a mild mediastinal shift to the right side. (B) Follow-up radiograph of the same patient reveals a soft tissue mass lesion in the region of left lower lobe. It reveals homogeneous density with and the left hemidiaphragm is not seen separately from the lesion. Underlying lung field is collapsed and is seen lying superior to the lesion. (C) Radiograph of the chest posteroanterior view taken immediately following accident reveals minimal left-sided pleural effusion.

Case 3

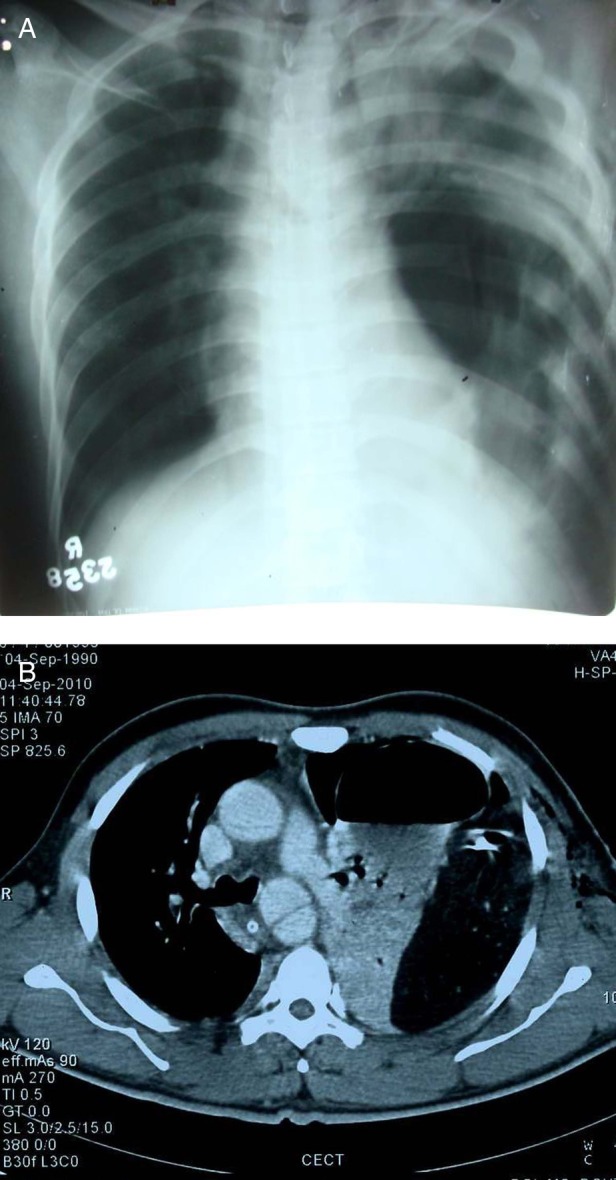

A 20-year-old man presented with a pain in the chest and abdomen and respiratory distress following road accident. There was no history of loss of consciousness, vomiting or seizures. On examination respiratory rate was 30/min, blood pressure was 170/100 mm Hg. On auscultation breath sounds were reduced bilaterally. He had also sustained head injury and a non-contrast CT scan revealed non-haemorrhagic contusion in the left frontoparietal region. Radiograph of the chest revealed hydropneumothorax on the left side, raised left hemidiaphragm and collapse of the left lower lobe (figure 3A). There was mediastinal shift to right side. Chest tube drainage was performed on the left side and there was a gush of air. A nasogastric tube was then inserted; however, on feeding the patient gave a history of passing food through the site of chest tube drainage. A CT scan revealed rupture of left hemidiaphragm with herniation of spleen, jejunum, ileum, splenic flexure and mesentery (figure 3B). In addition, there was also aortic dissection of the descending aorta superiorly along with pleural effusion with basal consolidation on the right side. The patient was operated and the findings were confirmed.

Figure 3.

(A) Radiograph of the chest posteroanterior view reveals loculated pneumothorax in the left hemithorax with mild mediastinal shift. Haziness is also seen on the left side which was misinterpreted as motion blur due to breathing. However, in retrospect it was possibly due to peristalsis. (B) Axial CT scan of the same patient at the level of aortic arch reveals herniation of stomach and mesentry into the left hemithorax and ‘dependent viscera’ sign.

Case 4

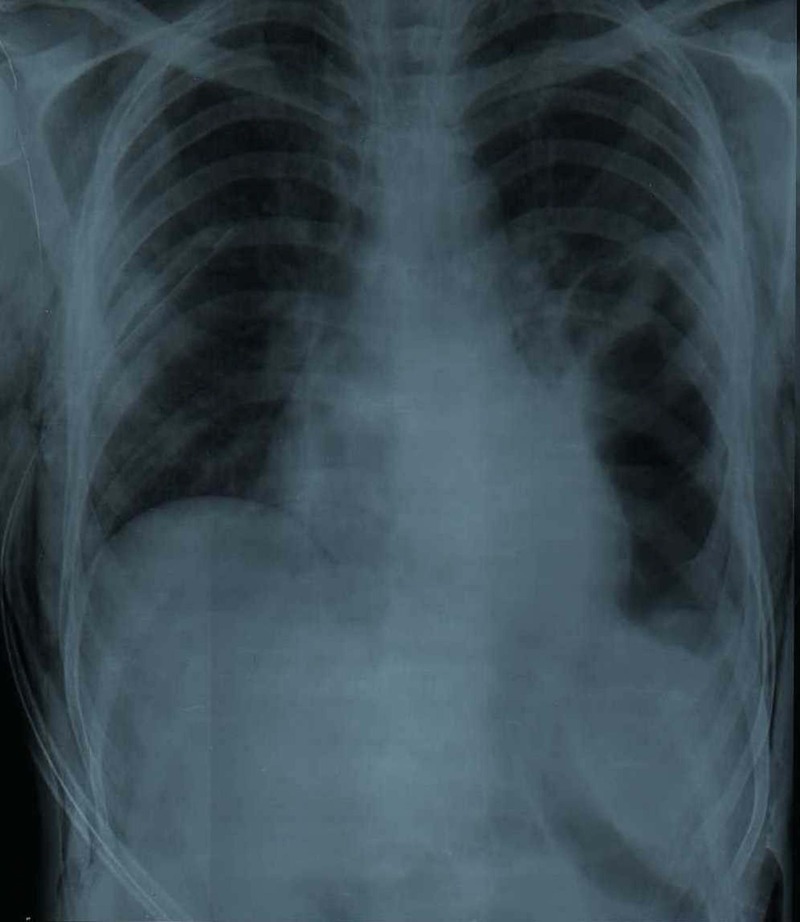

A 19-year-old boy presented with alleged history of assault on the previous day. On examination, he was semiconscious and his Glasgow Coma Score was 8/15 and breath sounds were not heard in the left lower lobe. CT of the brain revealed depressed fracture of the left frontal bone and pneumocranium. Radiograph of the chest revealed right-sided pneumothorax and collapsed right lung field. There was in addition loculated hydropneumothorax on the left side (figure 4). Chest tube drainage was attempted on both the sides. He got relief on the right side, however, on the left side there was herniation of omentum from the site of chest tube drainage. A diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia was made and a CT scan was performed which revealed a diaphragmatic hernia on the left side with a rent of size 4 cm approximately. There was herniation of stomach and splenic flexure into the chest cavity through the rent with ‘collar sign’ and ‘dependent viscera sign’. There was also minimal pleural effusion on the left side.

Figure 4.

Radiograph of the chest posteroanterior view with loculated pneumothorax in the left lower zone and possibly inversion of the diaphragm. Chest tube is seen on the right side. Motion blur is seen because the patient was unable to hold his breath.

Discussion

Chaudhary et al missed the diagnosis in their patient of traumatic rupture of diaphragm due to blunt trauma, because the patient presented with flail chest and subcutaneous emphysema which masked the associated signs. Also the herniated abdominal viscera escaped any iatrogenic injury during chest tube insertion.5

Harte et al reported a case of delayed diaphragmatic hernia after laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication which appeared to have occurred after a bout of strenuous physical activity. It was mistaken as left-sided pneumothorax for which chest tube thoracostomy was performed. However, the drain did not produce any fluid. A nasogastric tube was then passed and it was found curled up in the stomach on the chest X-ray and a diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture was made.6

Diagnosis of diaphragmatic rupture requires a high index of clinical suspicion and careful scrutiny of the chest radiograph which will raise the suspicion of diaphragmatic rupture in an estimated 40% of cases.7 Radiological features that suggest the possibility of diaphragmatic rupture include: elevated hemidiaphragm, irregular diaphragmatic outline, gas bubble in the chest, nasogastric tube in the chest and compression atelectasis of the lower lobe.8

Chaudhary et al6 found that the findings strongly suggestive of diaphragmatic rupture include an abnormal, usually high diaphragmatic contour with an arch-like shadow that simulates the diaphragm, gas bubbles or air-fluid levels in the chest above the expected levels of the diaphragm, intrathoracic abdominal viscera, with or without a site of focal constriction (collar sign) and clear demonstration of the nasogastric tube tip above the left hemidiaphragm.

Nchimi et al9 described 11 signs of blunt diaphragmatic rupture on CT scan including diaphragm discontinuity, segmental non-recognition of diaphragm, intrathoracic herniation of abdominal contents, collar sign, elevated abdominal organs, thickened diaphragm, thoracic fluid abutting intra-abdominal viscera, ‘dependent viscera’ sign, haemothorax and haemoperitoneum, contrast medium extravasation at level of diaphragm, presumed laceration of diaphragm by a fractured rib. CT scan was 100% accurate for the diagnosis of diaphragmatic hernia in the presence of herniated intra-abdominal viscera.7 Desser et al have described ‘Dangling diaphragm’ sign, in which the free edge of the torn hemidiaphragm curls inward from its normal course parallel to the body wall. According to them it is a conspicuous sign of diaphragmatic injury, and awareness of it may increase detection of diaphragmatic injury on CT studies.10

Approximately 1% of diaphragmatic ruptures are attributed to various minor precipitating factors, including coughing instead of any major trauma and are reported as being ‘spontaneous’.11 This is especially the case with inherent diaphragmatic weakness from preceeding blunt trauma or surgery. This was observed and reported by Amila et al2 and can cause confusion in the mind of the examiner.

It is important to ask for a detailed history including that of any previous radiographs taken in the recent past. This is demonstrated by the case described by Howe et al wherein clinical suspicion, a recent pre-employment radiograph and a history of blunt trauma sustained while ‘wrestling’ for the last chair in a friendly game of ‘Musical chairs’ at a Christmas party 18 days prior to admission saved the patient from an inadvertent bowel injury. They also recommended insertion of nasogastric tube, followed by a repeat physical examination and chest radiograph in suspicious cases. This can be confirmatory as well as therapeutic (decompression). Layering of gastric or intestinal contents may also be demonstrated by an additional decubitus view.12

Initial radiographs of trauma patient are technically compromised because the patient could not be positioned properly. Also they are examined by non-radiologists. In the appropriate setting lower lobe collapse in association with fractured ribs and fluid levels in the chest should alert them for the possibility of diaphragmatic hernia.

Learning points.

Detailed history is very important including that of any previous chest radiographs to correctly diagnose diaphragmatic hernia.

High index of suspicion must be entertained while diagnosing a pneumothorax in the setting of trauma.

In suspicious cases and whenever possible a nasogastric tube should be inserted before chest tube and check radiographs should be taken to note the position of the tip.

Emergency CT scan should be performed whenever possible.

Lower lobe collapse in association with fractured ribs and fluid levels in the chest in appropriate setting should raise the possibility of diaphragmatic hernia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Shaveta, Assistant Professor, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology for reviewing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: SM and SA diagnosed and wrote the manuscript. NJ performed the CT scans and reviewed the manuscript. ND treated the patient postadmittance and collected the data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Rivas LA, Fishman JE, Múnera F, et al. Multislice CT in thoracic trauma. Radiol Clin N Am 2003;2013:599–616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amila CA, Punyadasa CY, Tee A. Psuedopneumothorax—Hold that chest tube!. Int J Emerg Med 2008;2013:59–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zieren J, Enzweiler C, Muller JM. Tube thoracostomy complicates unrecognized diaphragmatic rupture. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1999;2013:199–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yahya AI, Przbylski J. Non-iatrogenic perforation of the stomach by a chest tube in a patient with traumatic diaphragmatic hernia. Royal Coll Surg Edin 1998;2013:62–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chaudhary D, Kadian YS, Fotedar S, et al. Traumatic rupture of diaphragm with flail chest mimicking tension hydropneumothorax. Indian J Chest Dis Allied Sci 2009;2013:173–5 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harte S, Casey RG, Mannion Des, et al. When is a pneumothorax not a pneumothorax? J Pediatr Surg 2005;2013:586–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCann B, O'Gara A. Tension viscerothorax: an important differential for tension pneumothorax. Emerg Med J 2005;2013:220–1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shapiro MJ, Heiberg E, Durham RM, et al. The unreliability of CT scans and initial chest radiographs in evaluating blunt trauma induced diaphragmatic rupture. Clin Radiol 1996;2013:27–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nchimi A, Szapiro D, Ghaye B. Helical CT of blunt diaphragmatic rupture. Am J Roetgenol 2005;2013:24–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desser TS, Edwards B, Hunt S, et al. The dangling diaphragm sign: sensitivity and comparison with existing CT signs of blunt traumatic diaphragmatic rupture. Emerg Radiol 2010;2013:37–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kobayashi I. Expiratory activity of the inspiratory muscles during cough. Jpn J Physiol 1992;2013:905–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.How C, Tee A, Quah J. Delayed presentation of gastrothorax masquerading as pneumothorax. Prim Care Respir J 2007;2013:54–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]