Abstract

Hydatid disease is a parasitic infestation caused by the tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus. Echinococcosis occurs worldwide and can affect multiple organs. The liver (75%) and the lungs (15%) are the most common sites of occurrence followed by the spleen, kidney, bones and brain. Peritoneal hydatidosis commonly occurs secondary to a ruptured hydatid cyst of the liver or the spleen. Primary peritoneal hydatidosis is an extremely rare entity accounting for just 2% of all intra-abdominal hydatid disease. Most patients remain asymptomatic for years before presenting with vague abdominal symptoms such as non-specific pain, abdominal fullness, dyspepsia, anorexia and vomiting. We successfully treated a 55-year-old woman with primary peritoneal hydatidosis. The role of imaging and immunological tests in the diagnosis is highlighted. The patient was managed by a combination of preoperative and postoperative antihelminthic therapy along with laparotomy, cyst deroofing, toileting and omentoplasty. The patient is asymptomatic at 1-year follow-up.

Background

Hydatid disease is a zoonotic disease, which is endemic to most parts of the developing world and livestock rearing areas in the Mediterranean region, Australia, the Middle East, Turkey, Africa and South America.1 The increase in world travel and migration of people across continents has made it imperative for all clinicians to know about this disease. Human echinococcosis is caused by the larval form of the genus Echinococcus, predominantly by Echinococcus granulosus. The most commonly affected organs are the liver (75%) and lungs (15%)2 with spleen, kidney, bones and brain, kidney, etc usually being secondarily involved.

Peritoneal hydatid disease is normally secondary to liver or splenic involvement following spontaneous rupture1 or accidental spillage during surgery. Primary peritoneal hydatidosis is seen in less than 2% of cases with intra-abdominal hydatidosis.3 Most of these cases are asymptomatic until the cyst reaches a large size, giving rise to symptoms such as pain, fullness of the abdomen and obstructive symptoms. Imaging modalities, though helpful, can be non-specific and so are the serological tests. We report a rare case of disseminated primary peritoneal hydatidosis, which was diagnosed using radiological and serological modalities. The primary site of the disease was confirmed at surgery.

Case presentation

A 55-year-old woman presented to the surgical outpatient clinic with pain in the left upper abdomen since 1.5 months. The pain was dull, non-radiating, initially continuous but later on intermittent with no aggravating or relieving factors. She gave no history of fever or chills. At the time of presentation, she had experienced 2–3 episodes of loose stools and vomiting. Vomitus was watery, non-bilious, non-blood stained and non-projectile.

Per abdominal examination revealed a soft mass in the left hypochondrium and left lumbar region measuring 15×10 cm, which was non-tender, non-mobile and cystic in consistency.

Investigations

All blood investigations were normal except for mild eosinophilia.

On the ultrasonography of the abdomen and pelvis, there was evidence of a large multicystic space-occupying lesion in the left hypochondrium and left lumbar region, closely abutting the spleen measuring 19×9 cm. The cyst showed a central echogenic area and was suggestive of a hydatid cyst.

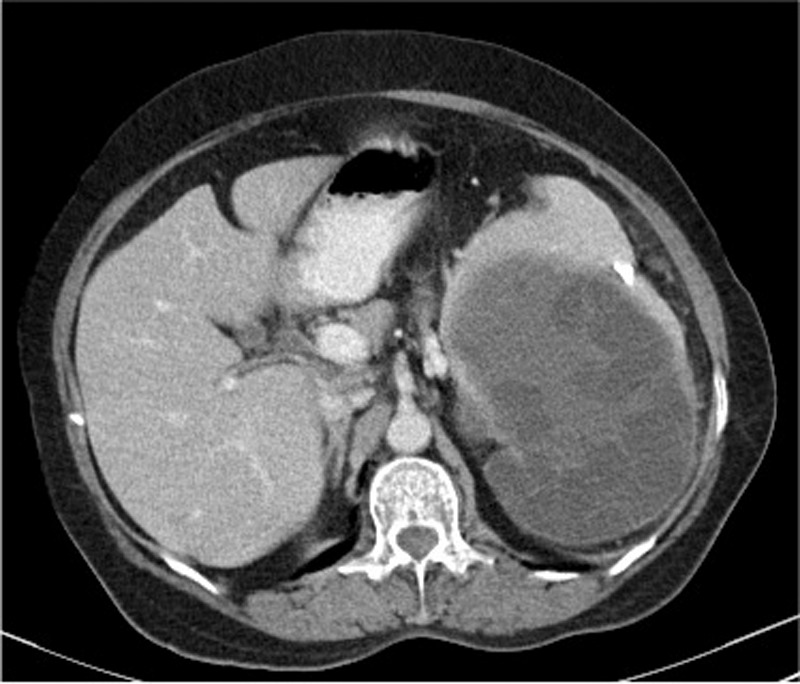

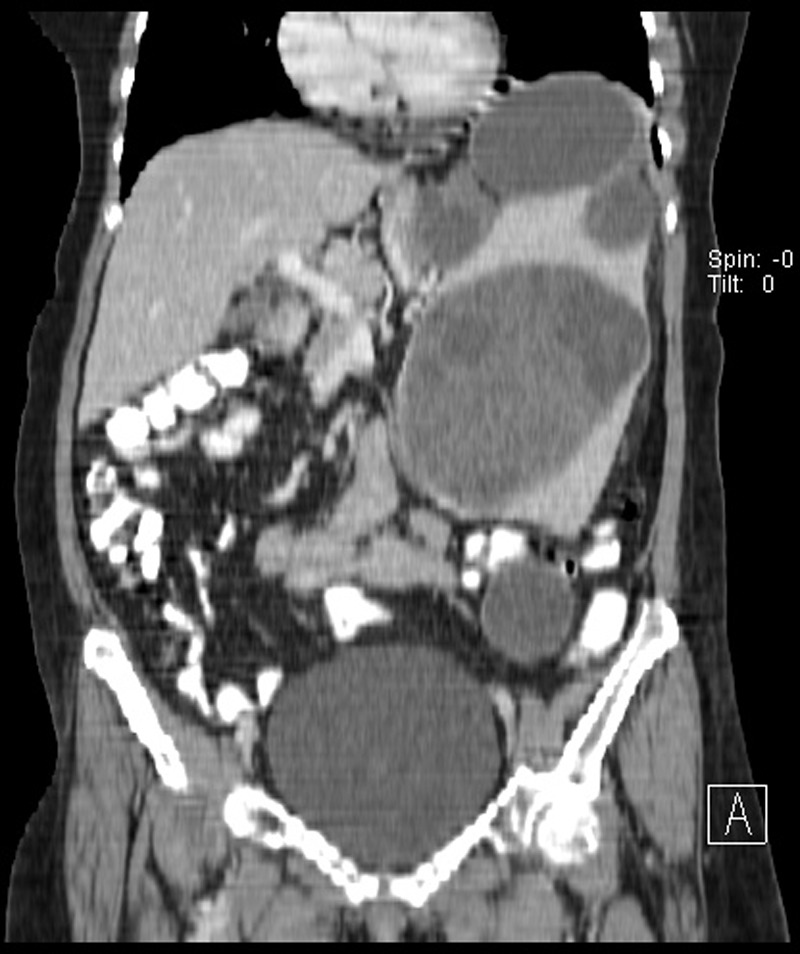

The contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis (figures 1 and 2) showed a large lobulated cystic lesion in the left hypochondrium, measuring 18×12×15 cm. The lesion had multiple rounded hypodense areas within suggestive of daughter cysts. The spleen was compressed by the lesion, with the fat planes of the lesion not separately identified from those of the spleen. Two areas of thin curvilinear calcifications were seen within the wall of the cyst. An area of large calcification was seen in the lateral aspect of the lesion. Another cystic lesion was seen in the left iliac fossa, lateral to the descending colon measuring 7.7×7 cm. A multicystic lesion was seen in the Pouch of Douglas as well, measuring 5×2.5 cm.

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT abdomen and pelvis (axial view) showing a large hydatid cyst with multiple daughter cysts adherent to and compressing the spleen.

Figure 2.

Contrast-enhanced CT abdomen and pelvis (coronal view) showing two intraperitoneal hydatid cysts, the larger cyst being adherent to the spleen and the smaller cyst in the left iliac fossa as described.

A diagnosis of disseminated intraperitoneal hydatid disease was hence made.

Her chest X-ray showed an elevated left hemidiaphragm.

IgG antibody test for echinococcosis by ELISA showed positive reading of 2.395 OD (positive absorbance reading >=0.3 OD)

Differential diagnosis

Considering the age of the patient and the presence of a large intra-abdominal cystic mass, clinically, an ovarian tumour and a cystic tumour arising from the spleen were considered in differential diagnosis. However, imaging and serological modalities confirmed the diagnosis of hydatid cyst.

Treatment

The patient was preoperatively prescribed albendazole 400 mg twice a day for 3 weeks, followed by surgery. A laparotomy was done. A large intra-abdominal cyst, containing multiple daughter cysts, extending to the pelvic cavity was noted pushing the spleen and left kidney upwards and laterally. The splenic artery and vein were adherent to the cyst wall. The cysts were deroofed, toileting was performed using 3% saline as the scolicidal agent, followed by omentoplasty. Care was taken to prevent any spillage and the bowel and other viscera were isolated using towels soaked in 3% saline.

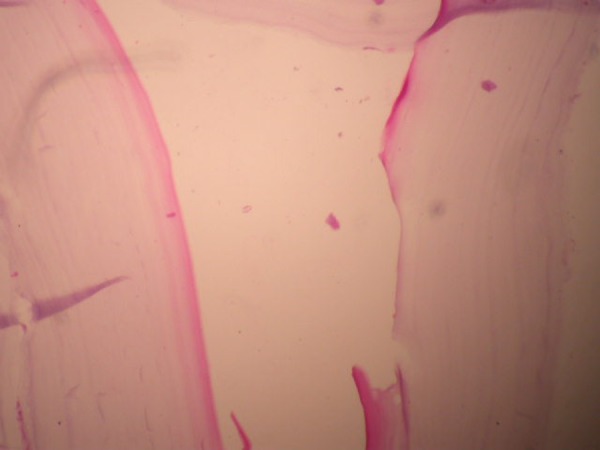

Histopathological examination of the specimen was consistent with a hydatid cyst wall and consisted grossly of multiple grey-white cystic masses, the largest cyst measuring 5×3.5 cm with multiple scolices seen. Microscopically, the sections showed membranous eosinophilic lamellated material. Daughter cysts were not seen (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Microscopy (×10, H&E staining) showing membranous eosinophilic lamellated structures consistent with a hydatid cyst wall.

Postoperatively the patient was prescribed albendazole tablets, 400 mg, twice a day for 3 months to prevent recurrence. After every month of postoperative albendazole therapy, a 2-week interval was given during which the patient's liver enzymes and blood counts were monitored.

Outcome and follow-up

The postoperative period was uneventful and the patient was discharged on the 10th postoperative day. Serial ultrasound abdomen and pelvis scans and clinical examinations were performed to follow-up the patient for 1 year. She has remained asymptomatic during this period.

Discussion

Echinococcosis is a parasitic disease caused by the larval form of the cestode echinococcus. Four species of this genus are known to cause infection in humans: E granulosus (cystic echinococcosis), Echinococcus multilocularis (alveoloar echinococcosis), Echinococcus vogeli and Echinococcus oligarthus (which cause polycystic hydatid disease).4 Dogs and other canids such as wolves and foxes are the definitive hosts while sheep, pigs, cattle and goats are intermediate hosts. Humans become accidental intermediate hosts through the faeco-oral route on consumption of vegetables contaminated with the eggs of E granulosus or due to close contact with pets carrying the parasite.5 Peritoneal hydatidosis comprises 10–16% of intra-abdominal hydatid disease.6 It mainly occurs secondary to rupture of a hepatic or splenic cyst either spontaneously or accidentally during surgery.7 Primary peritoneal hydatidosis accounts for less than 2% of intra-abdominal hydatidosis.4 The most common sites are the liver and lungs followed by the spleen, kidney, bones and brain. Dissemination occurs either by lymphatics6 or systemic circulation.8 Patients are usually asymptomatic for years. In pelvic hydatidosis, symptoms arise late and are generally due to the pressure effects of the cyst on adjacent organs such as the rectum and urinary bladder.9 They can rarely cause obstructed labour, obstructive uropathy and renal failure apart from symptoms due to allergic reactions and secondary infections. The diagnosis of hydatid cyst must be considered especially in endemic regions with a history of rearing livestock or owning pets, whenever a cystic mass is felt in the abdominal cavity. The differential diagnosis of such cystic intra-abdominal masses includes pancreatic cyst, mesenteric cyst, gastrointestinal duplication cyst, ovarian cyst, lymphangioma, intra-abdominal abscess, loculated ascites, haematoma, etc.10

In primary peritoneal hydatidosis, the haemogram may show evidence of eosinophilia. Liver and renal function tests are usually normal.

Ultrasonography and contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen are diagnostic for hydatid cysts. Ultrasonography of the abdomen is the most common first-line radiological investigation performed to determine the organ of origin and to characterise the hydatid cyst.10 It has a sensitivity of approximately 90–95%. Most often, a solitary unilocular lesion or multiple anechoic, well-defined cystic lesions with or without daughter cysts can be seen. The latter are made out by characteristic internal septations. Hydatid sand may be visible when shifting the patient's position during imaging and predominantly consists of hooklets and scolices. When the fluid pressure in the cyst rises, it may lead to detachment of the inner membrane or endocyst. The detached undulating membrane is pathognomonic and is known as Snake/Serpent sign.11 Collapse of the endocyst into the fluid in the dependent part of the cyst gives the appearance of debris floating on a layer of fluid within the cyst. This is called the Water Lily sign. In accordance with the WHO Informal Working Group Classification on Echinococcosis (WHO-IWGE)12 which is a more recent and standardised classification based on ultrasound images (compared with the older Gharbi classification13), our patient displayed type CE 2 hydatid cysts.

CT of the hydatid cysts has a high sensitivity of around 95–100%.14 Contrast-enhanced CT show these cysts to be well circumscribed, rounded lesions with low attenuation and no contrast enhancement.12 Subtle calcification of the cyst wall is best seen on unenhanced CT.

On plain X-ray of the abdomen, the hydatid cyst may show egg-shell calcification. In our patient, the chest X-ray revealed an elevated left hemidiaphragm, because of the mass effect of the cyst.

In conjunction with the above, serological tests such as ELISA, Indirect Hemagglutination and Immunoelectrophoresis are fairly reliable initial screening tools. Immunoelectrophoresis is a more sensitive test for antihydatid antibodies, but ELISA is more specific.15 ELISA can also be used postoperatively to monitor the patient for recurrences.

Even though hydatidosis is widespread in incidence and the treatment is well known, unless managed properly, patients can have complications such as compression of structures, infections, rupture of cysts and ensuing anaphylaxis, secondary dissemination, fistulisation into the colon, sclerosing cholangitis and portal hypertension.

Medical management with albendazole/praziquantel either alone or as an adjuvant to surgery is used depending on the size, location and dissemination of cysts. Surgery remains the treatment of choice especially in larger cysts and hydatidosis. The type of surgical intervention used has to be individualised for every patient. While complete cyst excision with no spillage or cyst rupture is ideal, it is not always feasible. In such cases, partial excision (if the cyst is in proximity to vital structures), with deroofing and omentoplasty is performed. The latter was performed in our patient because the splenic artery and vein were found to be adherent to the cyst wall. Newer modalities, such as puncture, aspiration, injection, reaspiration (PAIR), are increasingly showing good success rates as well.

However, these patients need to be followed up in the long term to rule out recurrence. Nearly a year after her surgery for intraperitoneal hydatidosis, our patient showed no signs of recurrence clinically and on monitoring with serial abdominal ultrasonography.

Learning points.

Primary peritoneal hydatidosis is a rare occurrence of a common disease.

Maintenance of a high degree of clinical suspicion for abdominal cystic masses particularly in endemic regions is essential, as clinical signs and symptoms can be non-specific for a prolonged period of time.

Diagnosis is made based on clinical suspicion, imaging and immunological tests.

Total surgical excision is the treatment of choice. Adequate preoperative and postoperative medical management prevents recurrence.

Long-term follow-up is required to detect and treat any recurrence.

Footnotes

Contributors: BH worked up, diagnosed and operated the patient. NH took the radiological and histopathological photographs, collected the case data and performed the literature review. BH and NH compiled the case report.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Pedrosa I, Saiz A, Arrazola J, et al. Hydatid disease: radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics 2000;2013:795–817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsaroucha AK, Polychonidis AC, Lyrantzopoulos N, et al. Hydatid disease of the abdomen and other locations. World J Surg 2005;2013:1161–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh RK. A case of disseminated abdominal hydatidosis. J Assoc Physicians India 2008;2013:55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Khuroo MS. Hydatid disease: current status and recent advances. Ann Saudi Med 2002;2013:56–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chatterjee KD. Parasitology, protozoology and helminthology. 13th edn. New Delhi, India: CBS, 2009;159–65 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iuliano L, Gurgo A, Polettini E, et al. Musculoskeletal and adipose tissue hydatidosis based on the iatrogenic spreading of cystic fluid during surgery: report of a case. Surg Today 2000;2013:947–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuksel M, Demirpolat G, Sever A, et al. Hydatid disease involving some rare locations in the body: a pictorial essay. Korean J Radiol 2007;2013:531–40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Astarcioglu H, Kocdor MA, Topalak O, et al. Isolated mesosigmoidal hydatid cyst as an unusual cause of colonic obstruction: report of a case. Surg Today 2001;2013:920–2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parray FQ, Wani SN, Bazaz S, et al. Primary pelvic hydatid cyst: a case report. Case Rep Surg 2011;2013:809387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sable S, Mehta J, Yadav S, et al. “Primary omental hydatid cyst”: a rare entity. Case Rep Surg 2012;2013:654282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rasheed K, Zarger SA, Ajaz Ahmed Telwani AA. Hydatid cyst of spleen: a diagnostic challenge. N Am J Med Sci 2013;2013:10–20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO Informal Working Group International classification of ultrasound images in cystic echinococcosis for application in clinical and field epidemiological settings. Acta Trop 2003;2013:253–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gharbi HA, Hassine W, Brauner MW, et al. Ultrasound examination of the hydatic liver. Radiology 1981;2013:459–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalovidouris A, Pissiotis C, Pontifex G, et al. CT characterization of multivesicular hydatid cysts. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1984;2013:839–45 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sadjjadi SM, Abidi H, Sarkari B, et al. Evaluation of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, utilizing native antigen B for serodiagnosis of human hydatidosis. Iran J Immunol 2007;2013:167–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]