Abstract

Palliative care psychiatry is an emerging subspecialty field at the intersection of Palliative Medicine and Psychiatry. The discipline brings expertise in understanding the psychosocial dimensions of human experience to the care of dying patients and support of their families. The goals of this review are (1) to briefly define palliative care and summarize the evidence for its benefits, (2) to describe the roles for psychiatry within palliative care, (3) to review recent advances in the research and practice of palliative care psychiatry, and (4) to delineate some steps ahead as this sub-field continues to develop, in terms of research, education, and systems-based practice.

Keywords: Palliative care, Hospice, Palliative care psychiatry, Patients, Caregivers, Families, Advance illness, Quality of life, Total pain, Psychotherapy, Dignity therapy, Depression, Delirium, Anxiety, Geriatric disorders

Introduction

From the earliest stages of the modern hospice movement, there was an acknowledgement of the depth of psychological distress that many dying patients experience. The British physician Cicely Saunders, widely credited with establishing modern standards of hospice care, echoed Tolstoy's reference to “mental sufferings” in a 1963 address to the Royal Society of Medicine. Describing the management of pain in patients with terminal cancer, Saunders observed that “mental distress may be perhaps the most intractable pain of all” [1]. In her later writings, Saunders articulated the concept of “Total Pain,” now embodied in the interdisciplinary approach to patient care that characterizes modern-day palliative medicine. Within “Total Pain,” Saunders placed emotional distress alongside physical pain and social and spiritual problems, arguing that effective care of dying patients required attention to the relief of suffering in each of these domains [2].

During the early years of its development, however, palliative care seldom involved psychiatrists. The reasons for this have not been empirically examined, but several barriers to psychiatric involvement in palliative care have been proposed: personal factors, for example, disinterest or uncertainty among psychiatrists about their ability to be of value at the end of life, or palliative care providers' beliefs that they themselves can adequately address psychological distress. Systems-level factors may have also contributed, including funding structures that are unfamiliar or inadequate to compensate psychiatry providers. Practice patterns within the field of psychiatry might also have been at play, as the emergence of palliative care coincided with a movement toward increasingly exclusive reliance on psychopharmacology, and away from psychotherapeutic modes of care [3, 4].

Nevertheless, more recently, significant progress has been made in expanding the interface between psychiatry and palliative medicine. While palliative care has matured as a field – with, for example, the consolidation of content expertise, formalization of an accredited medical subspecialty, and expansion of services in both hospice care and palliative care consultation – the past decade has also seen significant growth in the development of palliative care psychiatry as a sub-field bridging these two disciplines. Increasingly, psychiatrists have found ways to bring their expert skills and knowledge to the care of seriously ill patients. For example, a small number of academic medical centers have included psychiatrists in their palliative care teams, often in leadership roles [3]. Similarly, one major community hospice has established an in-house psychiatry program to provide access to specialist-level expertise in addressing the emotional distress of hospice patients and their caregivers [5]. Much of the content of palliative care psychiatry has been distilled in a text, the Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine [6], and this body of knowledge has been enlarged and refined by new data from clinical research in several different domains. Taken together, these developments embody a subspecialty field at the intersection of Palliative Medicine and Psychiatry, an emerging discipline that brings expertise in understanding the psychosocial dimensions of human experience to the care of seriously-ill patients and the support of their families.

The present review seeks to capture some of the most recent developments in Palliative Care Psychiatry, and to cast an eye toward the road ahead for this emerging sub-field. The goals of the review are (1) to briefly define palliative care and summarize the evidence for its benefits, (2) to describe the roles for psychiatry within palliative care, (3) to review recent advances in the research and practice of palliative care psychiatry, and (4) to delineate some steps ahead as this sub-field continues to develop, in terms of research, education, and systems-based practice.

What Is Palliative Care?

For readers not familiar with hospice and palliative care, a brief review will help to contextualize the role that psychiatrists may play within this broader field of medicine. Misconceptions abound concerning what palliative care is. In recent public opinion polling, for example, some 70% of adults describe themselves as “not at all knowledgeable” about palliative care [7]. Even among physicians, low levels of knowledge and misinformed attitudes have sometimes shaped perceptions of palliative care, though survey data on this question shows wide heterogeneity [8 – 10].

One reason for low levels of understanding about palliative care is that different definitions exist. The following definition, which helps to clarify some common misunderstandings, has been recently put forward by the Center to Advance Palliative Care:

“Palliative care is specialized medical care for people with serious illnesses. This care is focused on providing patients with relief from the symptoms, pain, and stress of a serious illness – whatever the diagnosis. The goal is to improve quality of life for both the patient and the family. Palliative care is provided by a team of doctors, nurses, and other specialists who work with a patient's other doctors to provide an extra layer of support. Palliative care can be appropriate at any age and at any stage in a serious illness, and can be provided together with curative treatment” [7].

The most important – and frequently misunderstood – elements of this definition include the focus on preserving quality of life, attention to suffering in both the patient and caregivers, care that is provided by a team with interdisciplinary expertise, and support that can complement disease-oriented treatments throughout the entire course of an illness for persons of any age.

What Is Hospice?

When a cure is no longer possible, or when disease-modifying treatment is no longer desired, palliative care may become the sole focus of care. Hospice delivers enhanced palliative care, wherever patients live, when prognosis is short and the goals of therapy are to optimize quality of life and function in the final phase of life. Uniquely, hospice services also include bereavement care for family members up to and after a patient's death [11]. In the United States, hospice care is available to patients with a prognosis of 6 months or less, and the services provided are largely governed by the guidelines of the federal healthcare benefit.

Who Practices Palliative Care?

A further distinction is warranted, concerning the nature of palliative care: is it an approach to care, a medical subspecialty, or something else? All physicians, regardless of specialty, should be competent in providing basic or “primary” palliative care: attending to whole-person and family concerns, rooting treatment in an understanding of the illness experience, clarifying basic goals of therapy, and giving due weight to symptom relief and quality of life. A subset of physicians, with further experience or formal training in this set of skills and knowledge, will practice specialized or “secondary” palliative care, often in the role of palliative care consultants and part of a multidisciplinary team. Finally, “tertiary” palliative care is needed for the most challenging cases; it is provided by experts who are also involved in research and education of new trainees in the subspecialty [12].

Lastly, Hospice and Palliative Medicine is a subspecialty medical field, formally recognized in 2006 by the American Board of Medical Specialties and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Ten medical boards, including the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, sponsor the Hospice and Palliative Medicine subspecialty certification. As of 2012, qualification for the Hospice and Palliative Medicine subspecialty board required completion of an ACGME-accredited 1-year postgraduate fellowship [13, 14]. As mentioned, palliative care is provided by interdisciplinary speciality teams, and specialist-level training experiences and/or competencies also exist for palliative care nursing [15], social work [16, 17], and chaplaincy [18].

Benefits of Palliative Care

An exhaustive discussion of the benefits of palliative care is beyond the scope of this review, and several excellent summaries can be found elsewhere [12, 19]. The following focused review captures the most important clinical and economic benefits that have been seen with palliative care.

Quality of Care

A number of studies have looked at clinical outcomes in different palliative care settings. These include observational and quasi-experimental designs, and, more recently, randomized trials. In general, many of these show improvements in symptom relief, and most show improvements in quality of life. For example, in a retrospective study of over 400 cancer patients, an outpatient palliative care intervention was associated with significant reductions in pain, fatigue, dyspnea, insomnia, depression and anxiety, as well as significant improvements in overall quality of life [20].

In addition, surveys have consistently reported high levels of satisfaction among family and caregivers. In a nationally representative sample of family members of deceased patients, for example, those who used home-based hospice services (as compared to home health, nursing home, or hospital) reported improved relief of pain, higher levels of emotional support for both patient and family, increased treatment with respect, and higher overall quality of care [21].

Costs and Resource Allocation

In another line of research, several studies have have examined the relationships between palliative care and medical costs or resource allocation. For example, in a small prospective pre/post performance improvement study, inpatient palliative care consultation was associated with significantly reduced length-of-stay in the ICU, from 16 days with standard care to 9 days with palliative care [22]. Also, in a large study of Medicaid beneficiaries at four acute-care hospitals in New York state, palliative care consultation was associated with substantial reductions in average total costs per admission – with savings of just over $4,000 per patient [23]. Lastly, looking at palliative care in the very final stages of life, a recent study examined data from a longitudinal survey of a nationally-representative cohort of older adults. Substantial reductions in cost were found for hospice enrollees relative to non-hospice matched controls, largely independent of the duration of hospice enrollment [24].

Survival

Concerns are sometimes raised that the cost savings associated with palliative care stem from poorer survival among patients receiving these services; i.e. “palliative care saves money by shortening life.” To the contrary, recent data from well-designed trials indicates that, in some conditions, palliative care interventions may confer a survival benefit. In a 2010 study of adults with metastatic lung cancer at the time of diagnosis, participants were randomized in two treatment arms: standard cancer care alone, or standard cancer care plus palliative care. Patients in the palliative care arm experienced higher scores on measures of quality of life, reductions in depressive symptoms, reduced exposure to “aggressive” care, and improved survival – living on average more than two and a half months longer than their counterparts [25].

In summary, palliative care achieves better clinical outcomes than standard care alone. Patients feel better, they report improved quality of life, and caregivers report higher levels of satisfaction. When delivered by a specialist consultation team in a hospital, or in the hospice setting at the end of life, palliative care appears to be less costly than standard care alone, when matched by diagnosis and severity of illness. And finally, emerging data from at least one well-designed study suggests that under some circumstances there may be improvements in survival as well.

The Need for Psychiatry in Palliative Care

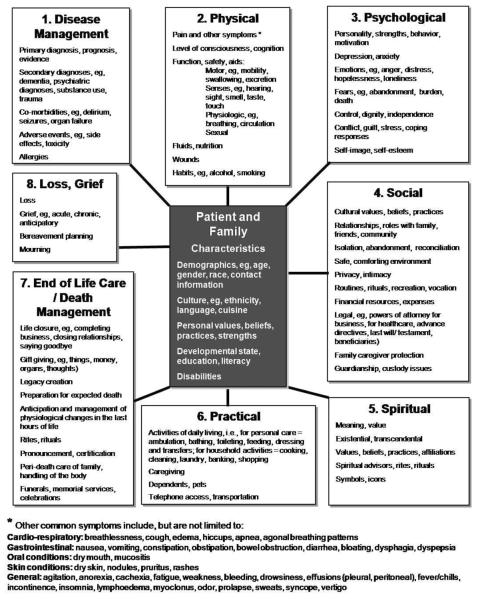

Where do psychiatrists fit in to palliative care? As noted, careful attention to addressing “Total Pain” has been one of the central tenets of modern palliative care. With this holistic and all-encompassing view of pain, Saunders advocated for a more person-centered and comprehensive approach to the care of the dying – one that sought to address not just the nociceptive components of a patient's pain, but – just as important – the emotional, spiritual, social, and experiential dimensions of their suffering as well. Saunders' conception of “Total Pain” has been operationalized by others, and, from the standpoint of identifying the opportunities for psychiatrists to be involved in palliative care, the model advanced by Ferris et al [11] is particularly useful (Figure 1). Ferris' (2002) model delineates eight dimensions of distress commonly experienced by seriously-ill patients and their families. Even setting aside the Psychological dimension, each of the other domains includes a number important issues for which a psychiatrist may have unique expertise in palliation: issues of meaning and life closure, intimacy in relationships, and concerns about bereavement, among other issues. In addition, good management of psychosocial and psychiatric issues often enables improved management and outcomes of the primary illness.

Figure 1.

Dimensions of distress in advanced, serious illness.

From Ferris et al. [11, 48]. Reprinted with permission from Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association and Frank D. Ferris.

More specifically, psychiatric syndromes, such as depression, anxiety, and delirium, are common in palliative care settings and frequently under-recognized or underappreciated, though they contribute to a substantial burden of suffering for patients and families. In hospice patients, for example, roughly 50% will experience symptoms of depression, approximately 70% will experience clinically significant anxiety, and nearly all patients will experience delirium as death nears. Psychiatric conditions are often difficult to differentiate in the setting of serious illness, due to symptom overlap with medical conditions. In addition, palliative care physicians are often uncomfortable with off-label use of psychotropic medications, and they lack expertise in psychotherapeutic interventions. Taken together, these data point to the value of close engagement of psychiatrists with palliative care teams [26].

Recent Advances in Palliative Care Psychiatry

In order to capture recent advances in the science and practice of palliative care psychiatry, we conducted a series of semi-structured literature reviews using PubMed. Searches were limited to the following major content domains: psychotherapy, depression, anxiety, and delirium. An additional search focused on systems-based or educational developments in palliative care psychiatry. For each domain, MeSH Major Topic headings were searched (e.g. (“palliative care”[MeSH Major Topic]) AND “delirium/therapy”[MeSH Major Topic]), in the three-year range from January 1, 2010 through December 31, 2012. Based on a review of the title and abstract, we identified pertinent clinical trials and any other relevant new empirical research (for example, epidemiologic surveys, psychometric analyses of screening measures, etc.), as well as papers describing novel practice models, educational interventions, or new theoretical work at the interface of psychiatry and palliative care. Papers identified in the systematic review were complemented by any additional pertinent references known to the authors.

Psychotherapy

Several psychotherapies have been adapted to or developed for the setting of advanced, life-threatening illness. Of these, two of the most prominent – Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy and Dignity Therapy – have been recently tested in randomized controlled trials.

Dignity Therapy is a brief individual psychotherapy derived from an empirical model of dignity in terminally-ill patients [27], with promising data for effectiveness from a phase 1 trial [28]. In a recent multi-site randomized controlled trial, Dignity Therapy (relative to client-centered care or standard palliative care) was associated with greater levels of perceived helpfulness, improved quality of life, greater sense of dignity, and a higher degree of helpfulness to the family. Of note, there were no significant differences in global distress levels, the primary outcome [29].

Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy is a short-term intervention grounded in the writings and logotherapy of Viktor Frankl. The treatment seeks to bolster meaning and spiritual well-being in terminally-ill patients, through both individual and group applications [30]. In a small, randomized controlled trial of the group format, participants received either the meaning-centered intervention or supportive group psychotherapy. Subjects in the meaning-centered psychotherapy arm reported significantly greater improvements in their sense of meaning and spiritual well-being, as well as reductions in both anxiety and desire for death [31]. In a follow-up trial of similar design, the individual format of meaning-centered psychotherapy was also tested. Here, the comparator was therapeutic massage. Again, participants who received the meaning-centered intervention reported significant improvements in spiritual well-being and quality of life, relative to their counterparts in the massage arm. The effect was short-lived, however, as differences in the treatment arms were absent by the two-month assessment [32].

Depression

Standard antidepressant therapies (SSRIs, SNRIs, etc.) frequently fall short in palliative care populations, because the time-course to effectiveness can be protracted, among other reasons. In patients with very short prognoses, when drugs are to be used, clinicians often select psychostimulants, which have a much more rapid onset of action. Though there is mixed data supporting the use of stimulants for depression in palliative care [33, 34], in general, careful, time-limited trials are often warranted.

In establishing the effectiveness of psychostimulants as antidepressants, one methodological challenge has been to distinguish the drug's impact on mood from its impact on fatigue. One recent small placebo-controlled randomized trial examined the effect of methylphenidate on both fatigue and depression. In this study, methylphenidate was associated with dose-dependent reductions in fatigue, as well as significant, but less robust, improvements in depressive symptoms relative to placebo [35].

Ketamine has recently emerged as a promising agent for the rapid treatment of depression: in a series of well-designed, randomized trials, sub-anesthetic, intravenous administration of ketamine in medically healthy subjects with depression has consistently produced rapid antidepressant effects [36, 37]. Building on this data, a recent open-label pilot study has examined the use of ketamine in the treatment of depression in hospice patients. Subjects received a low dose of oral ketamine, nightly, for up to 28 days. Ketamine use was associated with reductions in symptoms of depression and anxiety: for depression, improvement from baseline was significant by Day 14 and remained so through the 28-day trial. For anxiety, improvement from baseline was significant by Day 3, and, again, the effect persisted through the 28-day trial. Also of note, there were unexpected reductions in somatic symptoms as well. This small, open-label pilot study has a number of important limitations, and further investigation, with randomized-controlled clinical trials, will be necessary to confirm these findings and clarify the role for this promising treatment in hospice and palliative care [38].

Anxiety

Anxiety is a common source of distress in patients in palliative care settings, particularly near the very end of life. As with depression, standard pharmacologic treatments have a number of drawbacks, including a delay in effectiveness (with SSRI's, for example) or burdensome side-effects (with benzodiazepines, for example). Further, a recent Cochrane review found insufficient evidence to guide pharmacologic treatment of anxiety in adult palliative care populations [39]. In this context, approaches to managing anxiety frequently emphasize non-pharmacologic interventions, and medication strategies, when used, often rely on off-label treatments.

In addition to the studies mentioned above which showed improvements in anxiety outcomes [31, 38], two other recent publications have examined non-pharmacologic interventions to address anxiety in the palliative care setting. Plaskota et al (2012) report on a small open-label trial examining the effectiveness of hypnotherapy in reducing symptoms of anxiety. The subjects, patients in an inpatient hospice unit, received four sessions of hypnotherapy, and anxiety symptoms were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Participants experienced significantly reduced symptoms of anxiety by the second hypnotherapy session, and reductions from baseline remained significant through the fourth treatment [40].

Galfin et al (2012) describe a randomized controlled trial of a brief guided self-help intervention to target symptoms of anxiety among adult hospice patients. The intervention, a brief form of “concreteness training,” is designed to reduce psychological distress by targeting the cognitions centered on worry and rumination. The treatment consists of an initial face-to-face consultation with the provider, followed by 10-minute daily practice for four weeks. Participants were randomized to the treatment arm or a four-week control group (which later received the intervention). Subjects in the treatment arm experienced significant reductions in anxiety symptoms, as measured by the Generalized Anxiety Disorder GAD-7. No improvements were seen in reduction of depression or amelioration of quality of life [41].

Delirium

No clinical trials focused on delirium in the palliative care setting were identified in the systematic review, despite the high prevalence of delirium and its significant contribution to distress in patients and family.

Models of Care, Education, and System-Level Developments

In addition to these advances in the clinical basis for palliative care psychiatry, several recent developments in other areas also warrant mention. One important route to growing the interface of psychiatry in palliative care is to develop educational opportunities for psychiatry trainees interested in this emerging dimension in psychiatric practice. Irwin et al (2011) present data from a survey of general psychiatry training directors and residents, indicating that, with respect to palliative care psychiatry, formal learning opportunities within general residency programs are lacking, despite a high degree of interest among trainees. Further, they showed that a clinical rotation in palliative care (including supervised clinical activities in a community-based hospice program, communication training, and didactic instruction in palliative care) was associated with significant gains in competence and knowledge, as well as significant decreases in concerns about practicing in the palliative care setting [42].

Another route to expanding the practice of palliative care psychiatry is to develop models of care that promote integration of psychiatric services into palliative care teams. (Note the important distinction between collaboration on the one hand – having access to a psychiatrist, via consultation – and integration on the other – wherein the psychiatrist is an integral part of the multidisciplinary palliative care team.) Two recent papers describe this kind of integration within cancer hospitals in Japan. Uniquely, in order to qualify for funding support through the federal insurance program, interdisciplinary palliative care teams at cancer hospitals in Japan are required to include a psychiatrist, in addition to other specialists. The requirement stems from Cicely Saunders' notion that addressing “Total Pain” demands a team of specialists practicing interprofessionally to provide comprehensive, whole-person care. Ogawa et al (2010) examined 2000 consecutive palliative care referrals in a single cancer hospital in Japan and determined that psychiatrists (as members of the palliative care team) were involved in the care of 80% of all referrals, with delirium, adjustment disorder, depression, and dementia among the most common issues of focus for the psychiatric specialists [43]. In a further study, the same authors surveyed consult-liaison psychiatrists at 375 government-designated cancer hospitals in Japan. Hospitals with palliative care teams that met the standards of the national medical insurance program (with respect to inclusion of psychiatrists), were more likely to provide access to a full-time psychiatrist and psychiatric outpatient services, relative to cancer centers with palliative care teams that did not include a psychiatrist [44]. Whether this model results in improved quality of care or other desired outcomes remains to be examined.

Lastly, the number of psychiatrists formally certified as subspecialists in Hospice and Palliative Medicine is another indicator of psychiatric involvement in subspecialty-level palliative care. The certification exam has been given three times, and the number of passing examinees sponsored by the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, in each year, was as follows: 15 in 2008, 12 in 2010, and 34 in 2012 (Vollmer J, American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology, Inc. Personal communication). Of note, the 2012 exam represented the last opportunity for clinicians to qualify for the exam under the practice pathway. In the future, all examinees will have to have completed an accredited fellowship program in Hospice and Palliative Medicine. Because it is unusual for psychiatry residents to pursue fellowship training in Hospice and Palliative Medicine and most hospice and palliative medicine fellowships will not accept psychiatrist applicants, it is likely that in the future the number of psychiatry-trained subspecialists with the formal certification will be small.

Steps Ahead

What lies ahead for palliative care psychiatry? In terms of clinical developments, much work remains to be done to establish the basic epidemiologic parameters, robust detection, and effective treatment modalities for psychiatric illness in palliative care settings. This work would benefit from a deeper conceptual characterization regarding how to distinguish psychiatric syndromes from the sequelae of medical illness, as well as from normative psychological (i.e. non-pathological) experiences in the setting of a life-limiting illness. Finally, there is a clear need for more effective interventions for even the most common psychiatric conditions: rapid treatments to relieve depression, strategies to reduce anxiety, approaches to prevent delirium, and tools to minimize agitation in advanced dementia, for example.

New training opportunities and novel models of care will also need to be developed in order to take full advantage of the expertise that psychiatrists can bring to palliative care. As mentioned, trainees have indicated a strong interest in learning about how to apply their new skills in psychiatry to the care of seriously-ill patients [42], and the task of developing effective learning opportunities will fall to those psychiatrists and training programs that recognize the value that psychiatric expertise can add to palliative care. Hospice and Palliative Medicine fellowship programs will need to find a way to accept fellows from every discipline that sponsors this valuable subspecialty, including psychiatry and neurology. Further, sustainable practice models that emphasize interdisciplinary, whole-person care will need to include psychiatrists.

Lastly, at least two important areas of theoretical work remain to be explored. First, for the most part, psychiatric palliative care has focused on the emotional dimensions of suffering among patients with advanced medical illnesses, and, perhaps to a lesser degree, the management of comorbid psychiatric illness in this setting. In other words, the main thrust of psychiatric palliative care to date has been to bring psychiatric expertise to seriously-ill patients, many of whom had not previously experienced mental illness. Conversely, there has been little attention to developing models for the application of palliative care principles to the care of patients with chronic mental illness, with some important exceptions [43 – 45]. Secondly, palliative care practice entails a number of important ethical concerns, some of which bear uniquely on issues relevant to mental health. For example, in the context of making decisions about withdrawal of medical interventions, the presence of depression may raise questions about a patient's decisional capacity. Some work in psychiatric ethics have begun to explore questions like this [46, 47], but there remains a great need for normative and empirical research in bioethics at the interface of psychiatry and palliative care.

Conclusion

The “mental sufferings” of seriously ill and dying patients, described by Tolstoy in The Death of Ivan Ilych and echoed decades later in the seminal writings of Dame Cicely Saunders [2], warrant careful attention by palliative care teams. Quite often, the care of patients who experience serious psychological distress in the setting of a serious illness requires input from clinicians with expertise in psychiatric diagnosis and treatment. To this end, the past decade has seen significant strides in the development of a subspecialty field at the intersection of Palliative Medicine and Psychiatry. This emerging discipline brings expertise in understanding the psychosocial dimensions of human experience to the care of dying patients and support of their families. Still, there remain a number of important areas to develop, in areas of clinical care, practice models, and training opportunities.

Acknowledgment

This paper was supported by research funding from the National Institute of Mental Health (Scott A. Irwin).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Nathan Fairman and Scott A. Irwin declare that they have no conflict of interest.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as:

*Of importance

**Of major importance

- 1.Saunders C. The treatment of intractable pain in terminal cancer. Proc R Soc Med. 1963;56(3):195–197. doi: 10.1177/003591576305600322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clark D. `Total Pain,' disciplinary power and the body in the work of Cicely Saunders, 1958–67. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49:727–736. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00098-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meier DE, Beresford L. Growing the interface between Palliative Medicine and Psychiatry. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(7):803–806. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.9811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Billings JA, Block SD. Integrating psychiatry and palliative medicine: the challenges and opportunities. In: Chochinov HM, Breitbart W, editors. Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine. 2nd Edition Oxford University Press; Oxford: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 5.2009 APA Gold Award Integrating mental health services into hospice settings. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60(10):1395–1397. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.10.1395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Chochinov HM, Breitbart W, editors. Handbook of Psychiatry in Palliative Medicine. 2nd Ed Oxford University Press; CITY: 2009. [Google Scholar]; This text, edited by two central pioneers in the field, represents the first comprehensive attempt to capture the knowledge base for palliative care psychiatry

- 7. [Accessed March 2013];Center to Advance Palliative Care: Public Opinion Research on Palliative Care 2011. Available at http://www.capc.org/tools-for-palliative-care-programs/marketing/public-opinion-research/2011-public-opinion-research-on-palliative-care.pdf.

- 8.Hanratty B, Hibbert D, Mair F, et al. Doctors' understanding of palliative care. Palliat Med. 2006;20(5):493–497. doi: 10.1191/0269216306pm1162oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ogle KS, Mavis B, Wyatt GK. Physicians and hospice care: attitudes, knowledge, and referrals. J Palliat Med. 2002;5(1):85–92. doi: 10.1089/10966210252785042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brickner L, Scannell K, Marquet S, Ackerson L. Barriers to hospice care and referrals: survey of physicians' knowledge, attitudes, and perceptions in a health maintenance organization. J Palliat Med. 2004;7(3):411–418. doi: 10.1089/1096621041349518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ferris FD, Balfour HM, Bowen K, et al. A model to guide patient and family care: based on nationally accepted principles and norms of practice. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24(2):106–123. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00468-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12•.von Gunten CF. Evolution and effectiveness of palliative care. Am J Geriatr Psychiatr. 2012;20(4):291–297. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182436219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This short piece provides an exceptional overview of the evolution of palliative care in the U.S

- 13.von Gunten CF, Lupu D. Development of a medical subspecialty in palliative medicine: progress report. J Palliat Med. 2004;7:209–219. doi: 10.1089/109662104773709332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morrison LJ, Opatik Scott J, Block SD, et al. Developing initial competency-based outcomes for the hospice and palliative medicine subspecialist: phase I of the hospice and palliative medicine competencies project. J Palliat Med. 2007;10(2):313–330. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tice MA. Nurse specialists in home health nursing: the certified hospice and palliative care nurse. Home Healthc Nurse. 2006;24(3):145–147. doi: 10.1097/00004045-200603000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weisenfluh SM, Csikai EL. Professional and educational needs of hospice and palliative care social workers. J Sco Work End Life Palliat Care. 2013;9(1):58–73. doi: 10.1080/15524256.2012.758604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bosma H, Johnston M, Cadell S, et al. Creating social work copetencies for practice in hospice palliative care. Palliat Med. 2010;24(1):79–87. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cooper D, Aherne M, Pereira J, et al. The competencies required by professional hospice palliative care spiritual care providers. J Palliat Med. 2010;13(7):869–75. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19•.El-Jawahri A, Greer JA, Temel JS. Does palliative care improve outcomes for patients with incurable illness? A review of the evidence. J Support Oncol. 2011;9(3):87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This review, based on 22 randomized controlled trials, summarizes the quality of evidence related to improved outcomes from palliative care

- 20.Yennurajalingam S, Urbauer DL, Casper KLB, et al. Impact of a palliative care consultation team on cancer-related symptoms in advanced cancer patients referred to an outpatient supportive care clinic. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41(1):49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, et al. Family perspectives on end-of-life care at the last place of care. JAMA. 2004;291(1):88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, et al. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: effects on length or stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1530–1535. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morrison RS, Dietrich J, Ladwig S, et al. Palliative care consultation teams cut hospital costs for Medicaid beneficiaries. Health Aff. 2011;30(3):454–463. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelley AS, Deb P, Du Q, et al. Hospice enrollment saves money for medicare and improves care quality across a number of different lengths-of-stay. Health Aff. 2013;32(3):552–561. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25•.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(8):733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This is the first randomized controlled trial showing survival benefits to palliative care in metastatic lung cancer

- 26•.Irwin SA, Ferris FD. The opportunity for psychiatry in palliative care. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:713–724. doi: 10.1177/070674370805301103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This review describes the roles for psychiatry in the practice of palliative care

- 27.Chochinov HM. Dignity-conserving care: a new model for palliative care. JAMA. 2002;287:2253–2260. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.17.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chochinov HM, Hack T, Hassard, et al. Dignity therapy: a novel psychotherapeutic intervention for patients nearing death. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:5520–5525. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.08.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29•.Chochinov HM, Kristjanson LJ, Breitbart W, et al. Effect of dignity therapy on distress and end-of-life experience in terminally-ill patients: a randomized controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2011;12(8):753–762. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70153-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Dignity Therapy is one of two prominent psychotherapies developed for use in end-of-life care; this paper reports on the first randomized controlled trial of Dignity Therapy

- 30.Breitbart W, Gibson C, Poppito S, Berg A. Psychotherapeutic interventions at the end of life: a focus on meaning and spirituality. Can J Psychiatry. 2004;49:366–372. doi: 10.1177/070674370404900605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31•.Breitbart W, Rosenfeld B, Gibson C, et al. Meaning-centered group psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Psycho-oncology. 2010;19:21–28. doi: 10.1002/pon.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy is one of two prominent psychotherapies developed for use in end-of-life care; this paper reports on the first randomized controlled trial of Meaning-Centered Psychotherapy

- 32.Breitbart W, Poppito S, Rosenfeld B, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of individual meaning-centered psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(12):1304–1309. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.36.2517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Candy M, Jones L, Williams R, et al. Psychostimulants for depression. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD006722. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006722.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hardy SE. Methylphenidate for the treatment of depressive symptoms, including fatigue and apathy, in medically-ill older adults and terminally ill adults. Am J Geriatri Pharmacother. 2009;7(1):34–59. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2009.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kerr CW, Drake J, Milch RA, et al. Effects of methylphenidate on fatigue and depression: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;43(1):68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zarate CA, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant Major Depression. Arch Gen Psychiatr. 2006;63:856–864. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.aan het Rot M, Zarate CA, Charney DS, Mathew SJ. Ketamine for depression: where do we go from here? Biol Psychiatry. 2012;72:537–547. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Irwin SA, et al. Daily oral ketamine for the treatment of depression and anxiety. J Palliat Med. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.9808. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Candy B, Jackson KC, Jones L, et al. Drug therapy for symptoms associated with anxiety in adult palliative care patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;10:CD004596. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004596.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Plaskota M, Lucas C, Pizzoferro K, et al. A hypnotherapy intervention for the treatment of anxiety in patients with cancer receiving palliative care. Int J Palliat Nurse. 2012;18(2):69–75. doi: 10.12968/ijpn.2012.18.2.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Galfin JM, Watkins ER, Harlow T. A brief guided self-help intervention for psychological distress in palliative care patients: a randomized controlled trial. Palliat Med. 2012;26(3):197–205. doi: 10.1177/0269216311414757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Irwin SA, Montross LP, Bhat RG, et al. Psychiatry resident education in palliative care: opportunities, desired training, and outcomes of a targeted educational intervention. Psychosomatics. 2011;52:530–536. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Woods A, Willison K, Klington C, Gavin A. Palliative care for people with severe persistent mental illness: a review of the literature. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53(11):725–736. doi: 10.1177/070674370805301104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berk M, Berk L, Udina M, et al. Palliative models of care for later stages of mental disorder: maximizing recovery, maintaining hope, and building morale. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2012;46(2):92–99. doi: 10.1177/0004867411432072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Peteet JR, Meyer F, de Lima Thomas J, Vitagliano HL. Psychiatric indications for admission to an inpatient palliative care unit. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(6):521–524. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2009.0015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kissane DW. The contribution of demoralization to end of life decision making. Hastings Cent Rep. 2004;34(4):21–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schuman-Olivier Z, Brendel DH, Forstein M, Price BH. The use of palliative sedation for existential distress: a psychiatric perspective. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2008;16(6):339–351. doi: 10.1080/10673220802576917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ferris FD, Balfour HM, Bowen K, Farley J, Hardwick M, Lamontagne C, Lundy M, Syme A, West P. A Model to Guide Hospice Palliative Care. Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association; Ottawa, ON: 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]