Abstract

Xanthohumol (XN), a prenylated chalcone present in hops exhibits anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anticancer activity. In the present study we show that XN inhibits the proliferation of mouse lymphoma cells and IL-2 induced proliferation and cell cycle progression in mouse splenic T cells. The suppression of T cell proliferation by XN was due to the inhibition of IL-2 induced Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (Jak/STAT) and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1 and 2 (Erk1/2) signaling pathways. XN also inhibited proliferation-related cellular proteins such as c-Myc, c-Fos and NF-κB and cyclin D1. Thus, understanding of IL-2 induced cell signaling pathways in normal T cells, which are constitutively turned on in T cell lymphomas may facilitate development of XN for the treatment of hematologic cancers.

Keywords: Xanthohumol, IL-2, Jak/STAT, Erk1/2, proliferation

INTRODUCTION

Diet plays an important role in prevention of human diseases (1). Long-term consumption of plant derived foods (e.g., vegetables, fruits, beans, and nuts etc.) has been linked to low incidence of cancer, coronary heart disease and inflammatory diseases (2,3). The disease-preventing effects of these foods are partly attributed to the presence of bioflavonoids, a group of naturally occurring polyphenolic compounds with strong antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and their ability to modulate a range of cell signaling pathways involved in cellular proliferation, differentiation, survival and apoptosis (4).

Hops of the plant Humulus lupus L., are widely used in beer brewing to add bitterness and flavor to beer. Hop extract contains polyphenolic acids, prenylated chalcones, flavonoids, catechins and proanthocyanidins (5,6). Xanthohumol (3-[3,3-dimethyl allyl]-2,4,4-tri-hydroxychalcone) is the principal prenylated flavonoid found in hop resin (lupulin). Recently, potential health benefits of xanthohumol (XN) have been evaluated in several studies. XN was shown to increase the activity of phase 2 enzymes that detoxify carcinogens (7–9). XN inhibited the growth of a wide variety of human cancer cell lines including breast, colon, prostate, ovarian and leukemia by inhibiting proliferation and inducing apoptosis (10–12). In other studies, XN was shown to inhibit tumor cell invasion and angiogenesis (13,14) and the activity of topoisomerase, and aromatase (15,16).

In contrast to the significant anticancer activity of XN, little is known of the effects of XN on cells of the immune system. In one study, XN was shown to inhibit the expression of proinflammatory iNOS, IL-1β and TNF-α in activated RAW264.7 cells by either inhibiting NF-κB or STAT-1α and IRF-1 activation (17). In an earlier study, we showed that XN inhibited the mitogen/antigen-induced T cell proliferation, cell-mediated cytotoxicity and production of Th1 cytokines by inhibiting NF-κB (18). In the present study, we investigated the effect of XN on IL-2 induced signaling pathways involved in T activation and proliferation, which are also constitutively active in many hematologic cancers. The results showed that the inhibition of IL-2 induced T cell proliferation by XN was associated with the suppression of Jak/STAT and Erk1/2-mediated signal transduction pathways and proliferation-related cellular proteins such as c-Myc, c-Fos and NF-κB and cyclin D1.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Agents

Xanthohumol was purchased from Alexis Biochemicals (San Diego, CA). Human interleukin-2 (hIL-2) (2.5 ×108 U/mg) was purchased from PeproTech. Anti-Jak1, p-Jak1, STAT3, p-STAT3, p-STAT5, c-Fos and cyclin D1 antibodies were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Danvers, MA) and anti-c-Myc, NF-κB (p65), Erk1/2, p-Erk1/2 and β-actin antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). A 100 mM stock solution of XN was prepared in DMSO and all test concentrations were prepared by diluting the appropriate amount of stock solution in tissue culture medium.

Mice

Eight to 10-wk-old male C57 BL/6J (H-2b) mice were purchased from Charles River, NCI (Frederickberg, MD). Mice consumed Breeder Diet (W) 8626 (protein, 20.0%; fat, 10.0%; and fiber, 3.0%) and water ad libitum. Mice were housed for at least one week before experimental use. All animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Preparation of spleen cells

Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation and spleens were removed aseptically. Spleens were placed in cold phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and teased apart with a pair of forceps and a needle. Single-cell suspension from the teased tissue was obtained by passing it through a 22 G needle. Cells were washed two times in cold PBS and finally resuspended in complete RPMI-1640 medium.

Isolation of T lymphocytes

Spleen cells were enriched for T cells by filtering through nylon-wool column. Briefly, 2–3 × 108 spleen cells were loaded on a column made by packing 3 g acid-washed nylon wool in a 50 ml syringe. Columns were incubated at 37°C for 45 minutes. After incubation, nonadherent cells were eluted with warm complete RPMI-1640 tissue culture medium. Flow cytometric analysis showed >95% of these nylon wool nonadherent cells to be Thy 1.2 positive, a cell surface marker for mouse T lymphocytes.

Tissue culture

EL-4 lymphoma cells were obtained from obtained from the American Type Tissue Collection (Rockville, MD) and were maintained in RPMI-1640 medium (Grand Island Biological Company, Grand Island, NY), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (Hyclone, Logan, UT), 1% penicillin/streptomycin, 25 mmol/L HEPES buffer, and 5 ×10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol.

T lymphocyte were also cultured in fully supplemented RPMI-1640 medium as described above

3H-thymidine incorporation assay

To determine the effect of XN on proliferation, 2 ×103 EL-4 cells or 2 × 105 T cells were cultured in 0.2 ml of RPMI-1640 in each well of a 96-well microtiter tissue culture plate without (EL-4) or with hIL-2 (T cells, 150 ng/ml). XN was added to the cultures in concentrations as described in individual experiments at the initiation of cultures (EL-4 and T cells) or 48 h after stimulation of T cells with IL-2 in some experiments. After incubation for 3 days at 37°C, 95% humidity, and 5% CO2, 0.25 μCi of 3H-thymidine in 20 μl of PBS was added to each well and plates were incubated for additional 18 h. Cultures were harvested with an automatic cell harvester using distilled water. The amount of radioactivity incorporated into DNA was determined by β scintillation.

Western blot analysis

Cell lysates for Western blot analysis of cellular proteins were prepared by detergent lysis (1% Triton-X 100 (v/v), 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 5 mM EDTA, 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 2 mM sodium vanadate, 5 μg/mL leupeptin, 1 μg/mL aprotinin, 1 μg/mL pep-statinin, and 10 μg/mL 4-2-aminoethyl-benzenesulfinyl fluoride). Lysates were clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Protein concentration in extracts was measured by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, Richmond, CA). Samples (20 μg) were boiled in an equal volume of sample buffer (20% glycerol, 4% SDS, 0.2% Bromophenol Blue, 125 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), and 640 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) and separated on pre-casted Tris-glycine polyacrylamide gels (6–10%) using the XCell Surelock™ Mini-Cell, in Tris-Glycine SDS running buffer, all from Novex (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Proteins resolved on the gels were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were blocked with 5% milk in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl with 0.05% Tween 20 (TPBS) and probed with protein specific antibody or anti-β-actin antibody (loading control) followed by HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. Immune complexes were visualized with enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± SD. The difference between control and treatment groups was determined using Dunnett multiple comparison test. Differences with p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

XN inhibits proliferation of EL-4 lymphoma cells and IL-2 induced proliferation of splenic T cells

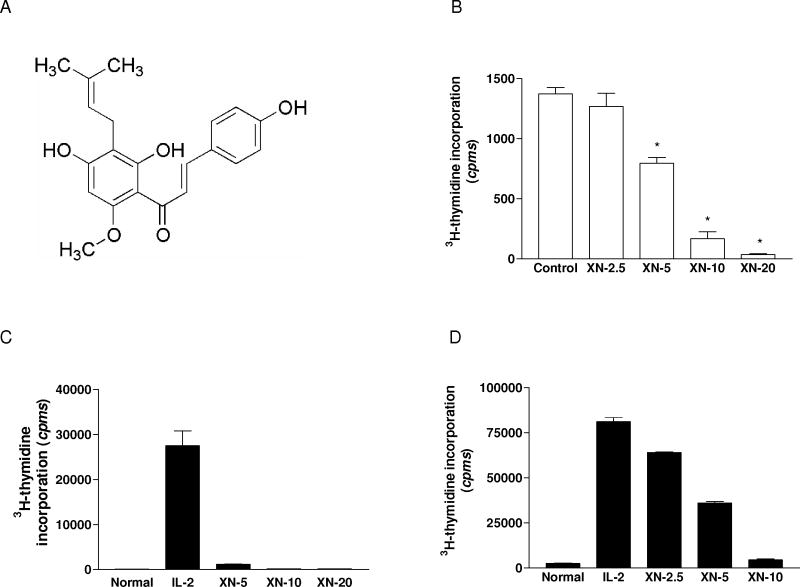

The effect of XN on proliferation of cells was measured by 3H-thymidine incorporation. EL-4 cells were treated with XN (2.5–10 μM) for 3 days and as shown in Figure 1B, XN significantly to completely inhibited the proliferation of EL-4 cells at concentrations of 5 to 10 μM. In the case of normal T cells, in first set of experiments, XN was added at the initiation of cultures. As shown in Figure 1C , XN drastically inhibited T cell proliferation at the lowest concentration of 5 μM (p<0.01) and the response was completely suppressed at 10 and 20 μM XN. Next, the effect of adding XN to cultures late after initiation of T cell activation with IL-2 was evaluated. For this purpose, XN (2.5–10 μM) was added to cultures 48 h after stimulation of T cells with IL-2. The result showed that even adding XN late after stimulation with IL-2 suppressed T cell proliferation in a dose related manner (Figure 1D). The antiproliferative effect was most pronounced at 5 and 10 μM XN (53% and 92% inhibition, respectively, p<0.01)). The inhibitory effect of XN on T cell proliferation was not due to DMSO used for dissolving XN, since equivalent concentrations of DMSO alone had no effect on the proliferation of EL-4 cells or T cells (not shown).

Figure 1.

Effect of XN on proliferation of lymphoma and normal T lymphocytes. A. Chemical structure of xanthohumol. B. 2×103 EL-4 cells/well were treated with XN (2.5–20 μM) in triplicates. C and D. 2×105 cells/well splenic T cells were stimulated with IL-2 (150 ng/mL) for 72 h. XN was added to cultures at concentrations as shown at the initiation of culture (C) or 48 h after initiation of cultures (D). After incubation for 72 h, cultures (B, C, D) were pulsed with 3H-thymidine (0.25 μCi/well) for 18 h and 3H-thymidine incorporation was determined by beta liquid scintillation spectrometry. Data are presented as mean (cpms) ± S.D. of 3 experiments.

Effect of XN on cell cycle progression and apoptosis

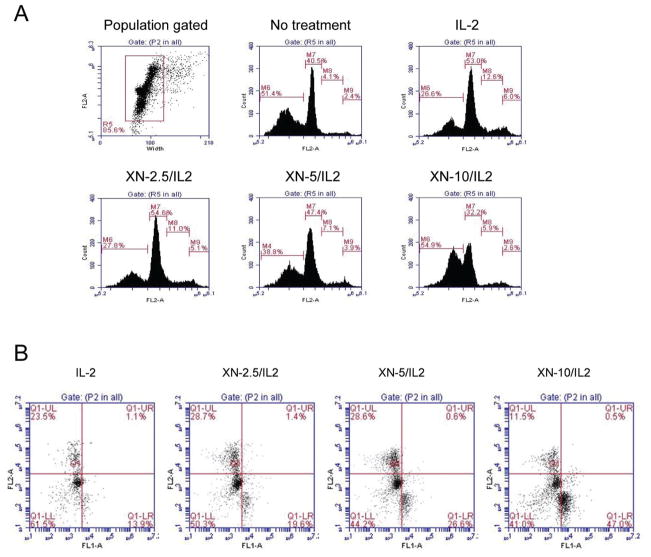

The effect of XN on IL-2 induced T cell cycle progression and apoptosis was determined by analyzing the nuclear DNA content and annexin V-FITC binding, respectively by flow cytometry. T cells were stimulated with IL-2 for 48 at which time cultures were exposed to XN at 2.5–10 μM for 24 h. Cells were fixed, stained with PI and DNA content analyzed by flow cytometer for cell cycle distribution and cells with less than 2 N DNA content. Figure 2A shows distribution of cells in sub G0 (apoptotic) G1, S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle. Compared to control cells cultured in medium alone cells stimulated with IL-2 showed reduction in the number of cells in sub G0 and an increase in the percentage of cells in G1 and S phases [IL-2 stimulated: 31%, 53%, 13% and 6%; control: 54%, 40%, 4% and 3% in sub G0, G1, S and G2/M phases of the cell cycle, respectively). On the other hand, compared to cells treated with IL-2, treatment with XN at 5 and 10 μM for 24 h increased the percentage of cells in sub G0 (45% and 64% vs 31%) and decreased the percentage of those in G1 and S phase (G1, 46% and 30% vs 53%; S, 7% and 6% vs 13%). XN also reduced the IL-2 induced increase in percentage of cells in G2/M phase.

Figure 2.

Effect of XN on cell cycle progression and apoptosis. A. 1×107 splenic T cells were cultured in 2.5 mL of complete RPMI-1640 culture medium were stimulated with IL-2 (150 ng/mL) for 48 h followed by treatment with XN (2.5–10 μM) for 24 h. Cells were fixed in cold 70% alcohol over night, treated with RNAse (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for 1 h at 37°C and stained with propidium iodide (PI). The DNA content of cells was analyzed by flow cytometry using Accuri C6 flow cytometer (Accuri Cytometers Inc. Ann Arbor, MI). B. T cells were cultured with IL-2 in the presence or absence of XN as described above and then reacted with 5 μl of annexin V-FITC reagent plus 5 μl of propidium iodide (PI) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. Stained cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. Data are presented as flow cytographs from a representative of three experiments (A and B).

To more directly measure apoptosis cells were stained with PI plus annexin V-FITC and analyzed by flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 2B, treatment with XN increased the percentage of apoptotic cells in cultures in a dose-related manner compared IL-2 stimulated cells (IL-2 = 13.9 vs XN 2.5 = 19.6%, XN 5 = 26.6%, and XN 10 = 47%). These results indicated that IL-2 protects T cells from apoptosis by promoting cell cycle progression which is inhibited by XN.

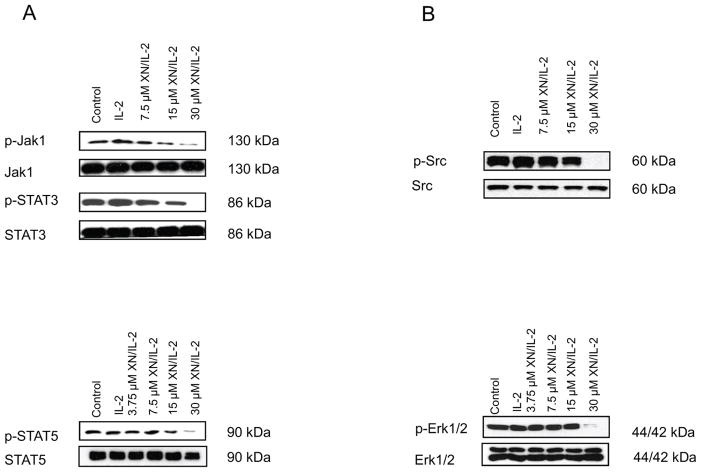

XN inhibits Jak/STAT signaling in T cells

Janus kinases 1 and 3 (Jak1 and Jak3) play critical role in transducing activation signal by IL-2 in T cells through phosphorylation and activation of STAT3 and STAT5 transcription factors which regulate genes involved in cell proliferation, differentiation and immune responsiveness (19–22). Whether inhibition of IL-2 induced T cell proliferation resulted from the suppression of Jak1/STAT signaling was examined. T cells were pretreated with XN (3.75 to 30 μM) for 30 min before stimulation with IL-2 for 15 min. Total cell lysates were analyzed for p-Jak1, p-STAT3 and p-STAT5 by immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 3, there was some increase in the levels p-Jak1, p-STAT3 and p-STAT5 following stimulation with IL-2. (lane 2 vs lane 1). On the other hand, pretreatment with XN inhibited the phosphorylation of these proteins by IL-2 in a dose-dependent manner at concentration range of 7.5 to 30 μM with complete inhibition of phosphorylation of each of these proteins occurring at 30 μM XN. In contrast, XN did not affect levels of non-phosphorylated Jaks or STATs.

Figure 3.

Inhibition of IL-2 induced T cell activation signaling pathways by XN. A. Splenic T cells were pre-treated or not with XN at concentrations as shown for 30 minutes and then stimulated with IL-2 (150 ng/mL) for 15 minutes. Cellular lysates were analyzed by Western blotting for effect of XN on p-Jak1, p-STAT5 and p-STAT3. B. Splenic T cells were pre-treated or not with XN for 30 minutes and then stimulated with IL-2 (150 ng/mL) for 30 minutes and cellular lysates analyzed for p-Src and p-Erk1/2 MAPK by Western blotting. Each experiment was repeated three times.

IL-2 can also activate Erk1/2 MAP kinases that regulate cell proliferation and cell differentiation (23,24). Therefore, we examined the effect of XN on p-Src and Erk1/2 components of the Src/Ras/MEK/ERK signaling pathway in T cells stimulated with IL-2. As shown in Figure 3, stimulation with IL-2 increased the levels of p-Src and p-Erk1/2 (lane 2 vs lane 1), which was unaffected by XN at concentrations of 3.75 to 15 μM. But at 30 μM XN, p-Src and p-Erk1/2 were completely abrogated.

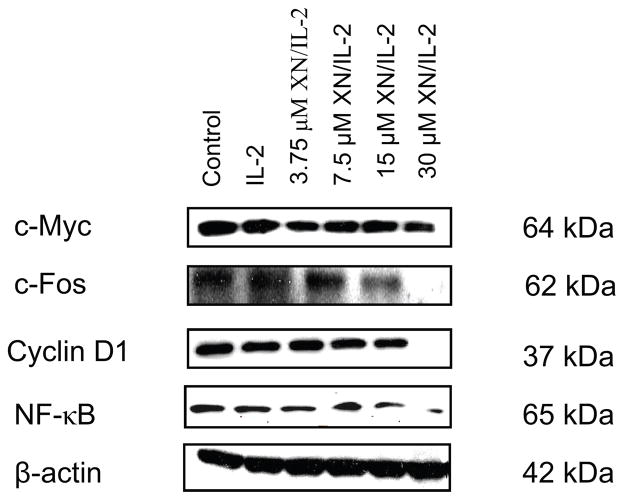

Effect of XN on cellular proteins associated with T cell proliferation

Because activation of Jak1/STAT5 and Erk1/2 signaling pathways lead to the expression of cellular proteins that control cell proliferation, we examined the effect of XN on the levels of cell proliferation associated c-Myc, c-Fos, NF-κB and cyclin D1 in T cells stimulated with IL-2. Thus, splenic T cells were treated or not with XN for 30 min before stimulation with IL-2 for 8 h and total cellular lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting. As shown in Figure 4, there was little change in the levels of c-Myc, c-Fos, NF-κB or cyclin D1 following treatment with IL-2. Treatment with XN up to a concentration of 15 μM did not significantly change the levels of these proteins. Only at 30 μM, XN significantly (c-Myc) to completely (c-Fos, NF-κB and cyclin D1) inhibited these proteins.

Figure 4.

Effect of XN on proliferation related cellular proteins. Splenic T cells were pretreated or not with XN for 30 min and then stimulated with IL-2 for 8 h. Cell lysates were analyzed for c-Myc, c-Fos, NF-κB and cyclin D1 by Western blotting. Similar results were obtained in two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Hop cones are used as sedatives, antispasmodic, bitter stomachic and microbicidal in folk medicine. Laboratory studies have shown that flavonones and chalcones with prenyl and geranyl groups present in hops have numerous biological effects, including chemopreventive, antiproliferative, antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities (6,8,12,25). However, the effects of the active principals of hops on cells of the immune system have only been meagerly studied. In an earlier study we showed that xanthohumol is a potent inhibitor of T cell proliferation, cytokine production and T cell-mediated cytotoxicity through the inhibition of NF-κB transcription factor (18). The present study extended these findings by evaluating the effect of XN on mouse lymphoma cells and IL-2-induced signaling pathways involved in T cell proliferation and activation. XN potently inhibited the proliferation of EL-4 lymphoma cells and IL-2 induced proliferation of mouse splenic T cells both when added at the initiation of cultures and late after stimulation of T cells with IL-2. These findings corroborate our earlier results showing strong inhibitory effect of XN on mitogen and antigen induced T cell proliferation and by others showing antiproliferative activity of XN on cancer cells (9,10,18). Analysis of DNA profile in IL-2 stimulated T cells treated with XN showed that XN inhibited cell cycle progression and induced apoptosis. Ribonucleotide reductase and DNA polymerase are two key enzymes involved in DNA synthesis as well as processes that are essential to allow cells to progress through the S phase of the cell cycle. In MDA-MB-435 breast cancer cell, XN suppressed DNA synthesis by inhibiting DNA polymerase α and arrested cells in the S phase (6). It remains to be established whether XN inhibits T cell proliferation and cell cycle progression through the inhibition of ribonucleotide reductase or DNA polymerase.

IL-2 is a vital growth factor for T lymphocytes during a developing immune response, expanding the pool of antigen specific T cells by enhancing cell proliferation and cell cycle progression and protecting antigen-activated T cells from apoptotic cell death (26). Numerous studies have been carried out to delineate the signal transduction pathways responsible for IL-2 induced T cell proliferation and activation. IL-2 signaling is mediated through a tripartite IL-2 receptor complex consisting of α, β, and γ subunits in which the later two subunits, i.e. β and γ subunits participating in ligand binding and signal transduction (27). Although IL-2 can activate several different pathways that mediate the mitogenic and survival-promoting signaling, but JAK/STAT signaling pathway has emerged as a major transducer of IL-2 signaling in T cell activation and proliferation (26,27). These signaling pathways are also constitutively active in a number of cancer types and are relevant therapeutic targets. Jak1 and Jak3 associated with IL-2R beta chain and IL-2R gamma chain, respectively and STAT3 and STAT5 transcription factors are the main mediators of IL-2 induced proliferation in T cells (28,29). Following binding of IL-2 to IL-2R, Jak1 and Jak3 are activated which in turn phosphorylate STAT5 and in some cases STAT3. Phosphorylation of STATs induces dimerization and their nuclear translocation, where they promote transcription of genes involved in cell proliferation, differentiation and immune responsiveness (22,30). Jak1 is the primary Janus kinase which is activated in T cells by IL-2. Our data demonstrated that stimulation with IL-2 increased the levels of phosphorylated Jak1 in T cells and XN prevented the IL-2 induced phosphorylation of Jak1 in a dose-dependent manner over a concentration range of 7.5 to 30 μM. Activated Jak1 (p-Jak1) generally partners with STAT5 in transducing IL-2 induced signaling of T cells, whereas STAT3 participates in the signaling of preactivated T cell (31). T cells treated with IL-2 showed increased levels of phosphorylated STAT 3 and STAT5 and both were reduced in cells pre-treated with XN. Together these data suggest that the inhibition of IL-2 induced T cell proliferation and cell cycle progression by XN might be attributable to the inhibition of JAK/STAT signaling pathway.

Src/Ras/MEK/ERK is another signaling pathway involved in IL-2 induced T cell activation and proliferation (32,33). Src/Ras/MEK/ERK signaling can occur directly upon binding of IL-2 to IL-2R or indirectly via JAK/STAT pathway activation. Indeed, stimulation of T cells with IL-2 increased the levels of p-Src and p-Erk1/2 and both were inhibited by XN at high concentration, indicating that inhibition of Src/Ras/MEK/ERK signaling is also part of the mechanism by which XN inhibits IL-2 induced T cell proliferation. The inhibition of signaling proteins occurred at higher concentrations of XN compared to those needed for inhibition of proliferation. This may be related the longer period of exposure of T cells to XN in proliferation assay (72 h) compared to a short period of exposure in signaling protein activation assay (30 min). Overall, results show that XN targets multiple signaling pathways in inhibiting IL-2 induced activation and proliferation of T lymphocytes.

The activation Jak1 and Src/Ras/MEK/ERK signaling pathways by IL-2 in T cells would result in activation of STATs and other transcription factors that control gene products (e.g., c-Myc, c-Fos, NF-κB, cyclin D1 etc.) involved in cell proliferation and cell cycle progression (34,35). In addition to the inhibition of STAT3 and STAT5, XN reduced the expression of c-Myc, c-Fos, NF-κB and cyclin D1, albeit at high XN concentration, indicating that inhibition of IL-2 signal transduction pathways and consequently the inhibition of proliferation-related gene products are responsible for the inhibition of IL-2 induced T cell proliferation by xanthohumol.

CONCLUSIONS

Xanthohumol is a potent inhibitor of proliferation of lymphoma cells and IL-2 induced proliferation of normal T lymphocytes. XN also inhibited cell cycle progression and induced apoptosis in T cells. The antiproliferative effect was mediated through the inhibition of IL-2 induced activation of Jak1/STAT5 and Erk1/2 signaling pathways. It also inhibited the proliferation related STAT3, STAT5, c-Myc, c-Fos, NF-κB and cyclin D1. Thus, the antiproliferative effects of XN are mediated through the inhibition of Jak1/STAT and Src/Ras/MEK/ERK signaling pathways and cell-proliferation-related gene products.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant CA130948-01 to S.C.G.

Footnotes

Reprints available directly from the publisher

References

- 1.Block G, Patterson B, Subar A. Fruit, vegetables, and cancer prevention: a review of the epidemiological evidence. Nutr Cancer. 1992;18:1–29. doi: 10.1080/01635589209514201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu FB, Stampfer MJ, Manson JE, Rimm E, Colditz GA, Rosner BA, Hennekens CH, Willett WC. Dietary fat intake and the risk of coronary heart disease in women. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1491–1499. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711203372102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Surh Y. Molecular mechanisms of chemopreventive effects of selected dietary and medicinal phenolic substances. Mutat Res. 1999;428:305–327. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(99)00057-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Stevens JF, Taylor AW, Deinzer ML. Quantitative analysis of xanthohumol and related prenylflavonoids in hops and beer by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 1999;832:97–107. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(98)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stevens JF, Page JE. Xanthohumol and related prenylflavonoids from hops and beer: to your good health! Phytochemistry. 2004;65:1317–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2004.04.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gerhauser C, Alt A, Heiss E, Gamal-Eldeen A, Klimo K, Knauft J, Neumann I, Scherf HR, Frank N, Bartsch H, Becker H. Cancer chemopreventive activity of Xanthohumol, a natural product derived from hop. Mol Cancer Ther. 2002;1:959–969. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miranda CL, Aponso GL, Stevens JF, Deinzer ML, Buhler DR. Prenylated chalones and flavanones as inducers of quinine reductase in mouse 1c7 cells. Cancer Lett. 2000;149:21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3835(99)00328-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietz BM, Kang YH, Liu G, Eggler AL, Yao P, Chadwick LR, Pauli GF, Farnsworth NR, Mesecar AD, van Breemen RB, Bolton JL. Xanthohumol isolated from Humulus lupulus inhibits menadione-induced DNA damage through induction of quinone reductase. Chem Res Toxicol. 2005;18:1296–1305. doi: 10.1021/tx050058x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miranda CL, Stevens JF, Helmrich A, Henderson MC, Rodriguez RJ, Yang YH, Deinzer ML, Barnes DW, Buhler DR. Antiproliferative and cytotoxic effects of prenylated flavonoids from hops (Humulus lupulus) in human cancer cell lines. Food Chem Toxicol. 1999;37:271–285. doi: 10.1016/s0278-6915(99)00019-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Delmulle L, Bellahcene A, Dhooge W, Comhaire F, Roelens F, Huvaere K, Heyerick A, Castronovo V, De Keukeleire D. Anti-proliferative properties of prenylated flavonoids from hops (Humulus lupulus L) in human prostate cancer cell lines. Phytomedicine. 2006;13:732–734. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colgate EC, Miranda CL, Stevens JF, Bray TM, Ho E. Xanthohumol, a prenylflavonoid derived from hops induces apoptosis and inhibits NF-kappaB activation in prostate epithelial cells. Cancer Lett. 2006;246:201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanhoecke B, Derycke L, Van Marck V, Depypere H, De Keukeleire D, Bracke M. Antiinvasive effect of xanthohumol a prenylated chalcone present in hops (Humulus lupulus L.) and beer. Int J Cancer. 2005;117:889–895. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Albini A, Dell’Eva R, Vene R, Ferrari N, Buhler DR, Noonan DM, Fassina G. Mechanisms of the antiangiogenic activity by the hop flavonoid xanthohumol: NFkappaB and Akt as targets. FASEB J. 2006;20:527–529. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5128fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee SH, Kim HJ, Lee JS, Lee IS, Kang BY. Inhibition of topoisomerase 1 activity and efflux drug transporter’s expression by xanthohumol from hops. Arch Pharm Res. 2007;30:1435–1439. doi: 10.1007/BF02977368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Monteiro R, Faria A, Azevedo I, Calhau C. Modulation of breast cancer cell survival by aromatase inhibiting hop (Humulus lupus L.) flavonoids. J Steroid Bioche Mol Biol. 2007;105:124–130. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2006.11.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhao F, Nozawa H, Daikonnya A, Kondo K, Kitanaka S. Inhibitors of nitric oxide production from hops (Humulus lupulus L) Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26:61–65. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cho YC, Kim HJ, Kim YJ, Lee KY, Choi HJ, Lee IS, Kang BY. Differential anti-inflammatory pathway by xanthohumol in IFN-gamma and LPS-activated macrophages. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008;8:567–73. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gao X, Deeb D, Liu Y, Gautam S, Dulchavsky SA, Gautam SC. Immunomodulatory activity of xanthohumol: inhibition of T cell proliferation cell-mediated cytotoxicity and Th1 cytokine production through suppression of NF-kB. Immunopharm Immunotox. 2009;31:477–484. doi: 10.1080/08923970902798132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyazaki T, Kawahara A, Fujii H, Nakagawa Y, Minami Y, Liu ZJ, Oishi I, Silvennoinen O, Witthuhn BA, Ihle JN, et al. Functional activation of Jak1 and Jak3 by selective association with IL-2 receptor subunits. Science. 1994;266:1045–1047. doi: 10.1126/science.7973659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin JX, Leonard WJ. The role of Stat5a and Stat5b in signaling by IL-2 family cytokines. Oncogene. 2000:2566–2576. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ihle JN, Witthuhn BA, Quelle FW, Yamamoto K, Thierfelder WE, Kreider B, Silvennoinen O. Signaling by the cytokine receptor superfamily: JAKs and STATs. Trends Biochem Sci. 1994;19:222–227. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(94)90026-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Darnell JE. Stats and gene regulation. Science. 1997;277:1630–1635. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5332.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miranda CL, Stevens JF, Ivanov V, McCall M, Frei B, Deinzer ML, Buhler DR. Antioxidant and prooxidant actions of prenylated and nonprenylated chalcones and flavanones in vitro. J Agric Food Chem. 2000;48:3876–3884. doi: 10.1021/jf0002995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smith KA. Interleukin 2. Annu Rev Immunol. 1984;2:319–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.02.040184.001535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malek TR, Castro I. Interleukin-2 receptor signaling: at the interface between tolerance and immunity. Immunity. 2010;33:153–165. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benczik M, Gaffen SL. The interleukin (IL)-2 family cytokines: survival and proliferation signaling pathways in T lymphocytes. Immunol Invest. 2004;33:109–142. doi: 10.1081/imm-120030732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Beadling C, Guschin D, Witthuhn BA, Ziemiecki A, Ihle JN, Kerr IM, Cantrell DA. Activation of JAK kinases and STAT proteins by interleukin-2 and interferon alpha, but not the T cell antigen receptor, in human T lymphocytes. EMBO J. 1994;13:5605–5615. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06898.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu KD, Gaffen SL, Goldsmith MA, Greene WC. Janus kinases in interleukin-2 –mediated signaling: Jak1 and Jak3 are differentially regulated by tyrosine phosphorylation. Curr Biol. 1997:817–826. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(06)00369-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu MH, Berry JA, Russell SM, Leonard WJ. Delineation of the regions of interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor beta chain important for association of Jak1 and Jak3. Jak1-independent functional recruitment of Jak3 to IL-2Rbeta. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10719–10725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lord JD, McIntosh BC, Greenberg PD, Nelson BH. The IL-2 receptor promotes lymphocyte proliferation and induction of the c-Myc, bcl-2, and bcl-x genes through the trans-activation domain of Stat5. J Immunol. 2000;164:2533–2541. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nielsen M, Svejgaard A, Skov S, Odum N. Interleukin-2 induces tyrosine phosphorylation and nuclear translocation of stat3 in human T lymphocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:3082–3086. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830241225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Motegi H, Shimo Y, Akiyama T, Inoue J. TRAF6 negatively regulates the Jak1-Erk pathway in interleukin-2 signaling. Genes Cells. 2011;16:179–189. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2010.01474.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ravichandran KS, Burakoff SJ. The adapter protein Shc interacts with the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor upon IL-2 stimulation. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:1599–1602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moriggl R, Topham DJ, Teglund S, Sexl V, McKay C, Wang D, Hoffmeyer A, van Deursen J, Sangster MY, Bunting KD, Grosveld GC, Ihle JN. Stat5 is required for IL-2-induced cell cycle progression of peripheral T cells. Immunity. 1999;10:249–259. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80025-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nosaka T, Kawashima T, Misawa K, Ikuta K, Mui AL, Kitamura T. STAT5 as a molecular regulator of proliferation, differentiation and apoptosis in hematopoietic cells. EMBO J. 1999;18:4754–4765. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]