Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in the United States. Women are more likely than men to present with advanced disease and experience higher CVD-related morbidity and mortality. Metabolic syndrome is a constellation of risk factors for Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and CVD. Abdominal adiposity, a component of metabolic syndrome, is associated with insulin resistance and promotes an atherogenic inflammatory milieu. Cardiometabolic risk (CMR) encompasses metabolic syndrome and incorporates other risk factors such as lifestyle choices, gender, and genetics as risk factors for CVD yet still does not include more recently recognized physiological risk factors such as vitamin D deficiency or psychosocial risk factors such as perceived stress and lack of social support. Because a more comprehensive view of CVD risk factors may facilitate earlier identification and risk reduction, we undertook this exploratory pilot study to answer the question, How do healthy women with and without abdominal adiposity differ physiologically and psychosocially?. We recruited a total of 41 women for a single study visit and assessed a battery of baseline physiological and psychological measures. While the women in this study were free of any diagnoses associated with increased CMR, women with increased waist circumference (WC) exhibited significantly altered levels of several measures associated with impending CMR including insulin sensitivity, lipids, and adiponectin as well as lower social support. These findings suggest that a more comprehensive conceptualization of and refinement of measures for CMR may be useful for identifying and reducing CMR and ultimately CVD in women.

Keywords: cardiovascular disease, women’s health, cardiometabolic risk

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death in adults in the United States and a major cause of disability, with annual health care and lost productivity costs exceeding $500 billion (American Heart Association, 2010). In women, CVD incidence increases with age, rising rapidly after menopause, with an average lifetime risk of one in two (Mosca et al., 2007). Historically, CVD has been underdiagnosed and inadequately treated in women for reasons related to issues of gender bias, lack of public and medical awareness of its prevalence, and its unique presenting symptomatology in women (Bedinghaus, Leshan, & Diehr, 2001). Despite increasing awareness, as well as better diagnostics and treatment, women are still more likely than men to present with advanced disease and to experience higher CVD-related morbidity and mortality (American Heart Association, 2010).

Metabolic syndrome is a constellation of risk factors for the development of Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and CVD, primarily through mechanisms of insulin resistance and systemic inflammation (Haffner, 2006). Abdominal adiposity, a component of metabolic syndrome, is associated with insulin resistance and promotes an atherogenic inflammatory milieu. Cardiometabolic risk (CMR) is a relatively new term that encompasses and expands upon metabolic syndrome. It is comprised of a set of risk factors that, when viewed together, are indicators of overall risk for developing CVD. These risk factors include those associated with metabolic syndrome, namely hypertension (HTN), obesity, high levels of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), high levels of blood triglycerides, and low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), but CMR also incorporates lifestyle choices such as smoking and physical inactivity as well as genetic predisposition (Alberti et al., 2009; Haffner, 2007). While CMR provides a more comprehensive view of factors associated with CVD risk, it does not include more recently recognized physiological risk factors such as vitamin D deficiency or thyroid dysfunction (Holick, 2005; Roos, Baker, Links, Gans, & Wolffenbuttel, 2007) or psychosocial risk factors such as perception of excess stress and lack of social support. For example, in the Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study, psychosocial stress and health behaviors were important predictors of inflammation and CVD (McDade, Hawkley, & Cacioppo, 2006). Using a psychoneuroimmunology (PNI)-based model focused on CVD, we undertook the present study to explore a more comprehensive model of risk factors associated with CMR in women to facilitate earlier identification and risk reduction. To this end, given the association between abdominal adiposity, CMR, and CVD risk, we posed the research question, How do healthy women with and without abdominal adiposity differ physiologically and psychosocially?

Background

Cardiometabolic Risk

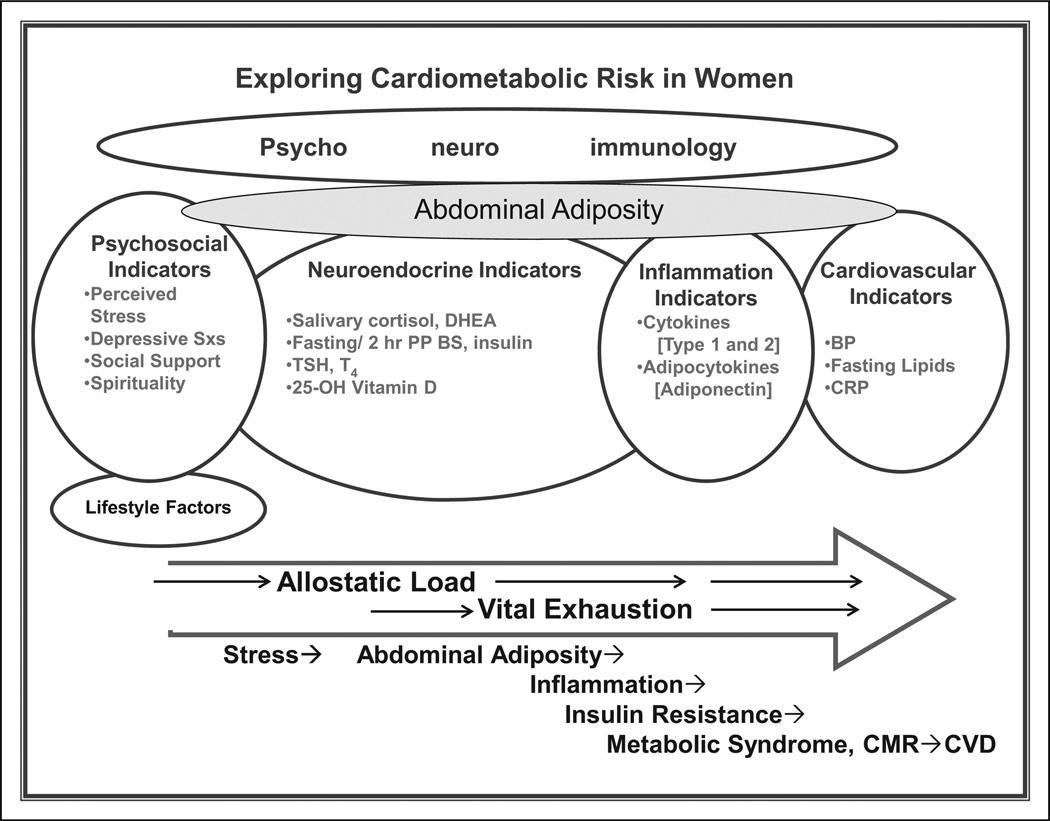

While CMR is currently defined and assessed using physiological indicators, mounting research indicates that psychosocial factors, particularly stress, are likely to contribute to its development and progression (McDade et al., 2006). Additionally, investigators have found evidence that perceived low social support and depressive symptoms contribute to the eventual development of CVD (Krantz & McCeney, 2002). In an overview of evidence linking acute and chronic stress to cardiac disease, Holmes, Krantz, Rogers, Gottdiener, and Contrada (2006) called for integration of psychosocial knowledge and variables in cardiology research and practice. Prevention of CVD in women may best be achieved by early identification and management of psychosocial issues and evolving physiological changes as opposed to waiting until risk factors fully manifest as disease. PNI and allostatic load provide a framework for integrating physiological and psychological variables to more comprehensively address CMR. We developed the comprehensive model presented in Figure 1 based on a broad review of the PNI and allostatic load literature related to the development of CVD in women.

Figure 1.

Exploring cardiometabolic risk in women.

PNI and Allostatic Load

PNI involves the investigation of the mechanisms of multidimensional psychobehavioral-neuroendocrine-immune system interactions, including the influence of behavioral factors on immunologically moderated and mediated diseases (Zachariae, 2009). Stress responses, while initially protective, are harmful when they become chronic and repetitive. Chronic stress and the associated psychological distress activate the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical (HPA) and sympathetic-adrenomedullary systems, generally inducing immunosuppression. Over time, these systems become fatigued and then exhausted, further contributing to dysregulation and disease development (McEwen, 1998; Zachariae, 2009). In addition to immunosuppression, various stressors and subsequent biological processes, notably alterations in cytokine production patterns, mediate sustained inflammation. Mechanisms underlying metabolic changes, weight gain, and insulin resistance involve altered cellular signaling related to a multitude of psychological and physical stress factors along with genetic predisposition, resulting in metabolic events that alter cellular function (Jones, Bland, & Quinn, 2005). For example, stress results in reduced energy production through altered insulin signaling. This illegitimate signal may be adaptive, in that it leads to energy conservation and weight gain for protection and survival under adverse conditions (Howard et al., 2004; Sanchez-Munoz, Garcia-Macedo, Alcon-Aguilar, & Cruz, 2005). However, atherosclerosis may develop because of chronic stress signals that overstimulate the sympathetic nervous system, causing regional fat accumulation in arterial adventitia (Yun, Lee, & Doux, 2006). Chronic stress contributes to depressed mood, immune dysfunction, and ultimately, T2DM and coronary heart disease (Lundberg & Frankenhaeuser, 1999; Vanitallie, 2002).

The aforementioned PNI example is one trajectory of disease development based on an initially adaptive response becoming maladaptive over time and is consistent with the concept of allostatic load (McEwen, 1998). Allostatic load is a general term used to explain the effects of cumulative stress; the particular mediators and outcomes are highly variable depending on the defining attributes of a particular allostatic model of disease. Combining the frameworks of PNI and allostatic load provides a starting point for incorporating and exploring the roles of both physiological and psychological stress factors in the trajectory of disease development.

Physiological Risk Factors for CVD

Abdominal adiposity

Central, or abdominal, obesity, reflecting the presence of visceral adipose tissue as evidenced by increased waist circumference (WC), has been shown to be a significant predictor of CVD (Hu et al., 2001; Rana, Li, Manson, & Hu, 2007). Abdominal adipose tissue acts as a pro-inflammatory endocrine organ, attracting monocytes and elaborating adipocytokines such as adiponectin, resistin, and leptin, as well as the cytokines tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interleukin (IL)-6, leading to chronic systemic inflammation. This inflammatory response may be the hallmark of CMR (Pi-Sunyer, 2006; Ritchie & Connell, 2006). Additionally, chronic stress can dysregulate the metabolic balance between cortisol and insulin. Excess cortisol causes insulin resistance in the liver and skeletal muscle through multiple mechanisms, including inhibition of pancreatic insulin secretion and dysregulation of glucose transport mechanisms (Adam & Epel, 2007; Tilg & Moschen, 2008). Insulin resistance is associated with a state of chronic low-grade inflammation involving increased pro-inflammatory cytokines and decreased adiponectin levels (Bastard et al., 2006; Tilg & Moschen, 2008). Investigators have found circulating adiponectin levels to be decreased in obesity-related insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, T2DM, and CVD (Bastard et al., 2006; Okamoto, Kihara, Funahashi, Matsuzawa, & Libby, 2006).

Neuroendocrine risk factors HPA axis function is of interest in the present study because of the relationships among perception of excess biopsychosocial stress, elevated cortisol, and immune system dysregulation. Chronic HPA axis stimulation initially creates hypercortisolemia, followed by hypocortisolemia, which contributes to systemic low-grade inflammation. Normal HPA axis activity, typically associated with more robust dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) levels, is associated with decreased avoidance and negative mood states in women with posttraumatic stress disorder (Rasmusson et al., 2004). While interest in the role and significance of HPA axis function in disease states is increasing, research focused on the relationships among HPA axis function, cortisol, DHEA, and cardiovascular health and disease is lacking. In one older study, Appels and Mulder (1988) found HPA axis overstimulation, termed vital exhaustion and defined as fatigue, irritability, and demoralized feelings, to be associated with the development of CVD as well as the incidence of CVD events in both persons with CVD and healthy individuals.

Insulin resistance, and ultimately metabolic syndrome and T2DM, are significant risk factors for CVD (Diamantopoulos et al., 2006). Research indicates that the greatest risk for the development of glucose-related atherosclerosis is “glycemic excursion,” or greater overall fluctuation in glucose levels (Behre, Fagerberg, Hulten, & Hulthe, 2005; Heine et al., 2004). Significant fluctuations associated with increased atherosclerotic risk include postprandial and postchallenge hyperglycemia (Alexandraki et al., 2006; Olszanecka-Glinianowicz, Zahorska-Markiewicz, & Janowska, 2006).

Hypothyroidism is related to CVD risk factors, including obesity, depression, and hyperlipidemia. Total thyroxine (T4) is a direct measure of the capacity of the thyroid gland to produce thyroid hormone. Research indicates that a broader model is needed to evaluate thyroid function. In one study of 2,073 clinically euthyroid adults, Roos and colleagues (2007) found low-normal thyroxine levels were significantly associated with abdominal obesity, low HDL-C, as well as high levels of LDL-C, total cholesterol, and triglycerides. The findings of another study indicated that at least 10–12% of the population may have borderline or subclinical hypothyroidism (Canaris, Manowitz, Mayor, & Ridgway, 2000). Subclinical hypothyroidism, defined by a serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of ≥6.0 mIU/ml and the absence of overt hypothyroid symptoms, is associated with depression, insulin resistance, and diabetes. Autoimmune thyroiditis is the most common cause of clinical and subclinical hypothyroidism in the United States. It occurs more commonly in women and is a risk factor for the development of CVD (Massoudi et al., 1995).

Vitamin D deficiency

Vitamin D deficiency has been implicated as a risk factor for the development of osteoporosis, metabolic syndrome (Martini & Wood, 2006), HTN, and CVD (Holick, 2005). Interestingly, CVD and cardiovascular mortality are associated with reduced bone mineral density (Baldini, Mastropasqua, Francucci, D’Erasmo, 2005), but the mechanisms linking these prevalent diseases are unclear. Inflammation may be part of the answer, given the inflammatory nature of CVD and the potent anti-inflammatory effects of vitamin D (Schleithoff et al., 2006; Vieth & Kimball, 2006). Additionally, the vitamin D receptor mediates the biological activities of the active form of vitamin D, 1α, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. These activities include calcium homeostasis, cellular differentiation, and immune functions, among others (Adachi et al., 2005).

Immune system risk factors

Persistent activation of the immune system with associated chronic low-grade inflammation is involved in the pathogenesis of insulin resistance. Furthermore, patterns of cytokine production are becoming increasingly popular as indicators of inflammation. As more data accumulate, the clinical applicability of these chemical messengers increases. Elevations in IL-6 followed by IL-1β and TNF-α stimulate hepatocyte production of C-reactive protein (CRP). Also, TNF-α is independently and inversely associated with insulin resistance (Pickup, 2004). Interferon (INF)-γ and IL-12 have not been specifically studied in CVD but are important inflammatory cytokines. The traditional anti-inflammatory proteins that have been evaluated in CVD research include IL-10, IL-1 receptor agonist, and IL-18 binding protein.

The classic pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 impact the levels of the adipocytokines adiponectin, resistin, and leptin and have been implicated in the development of insulin resistance and T2DM (Guest, Yan, O’Connor, & Freund, 2007). IL-6 is produced by adipocytes and has been shown to predict and contribute to the development of obesity-related insulin resistance (Beltowski, 2003). Matsuzawa, Funahashi, Kihara, and Shimomura (2004) showed that moderate weight loss decreases serum levels of IL-6 and improves insulin sensitivity.

Adiponectin is a protein produced by adipocytes and macrophages (Chen, Montagnani, Funahashi, Shimomura, & Quon, 2003). It is the most abundant adipose-specific cytokine, and low levels are associated with atherosclerotic CVD, T2DM, HTN, and hyperlipidemia (Okamoto et al., 2006). Thus, it is antidia-betic, antiatherosclerotic, and anti-inflammatory (Empana, 2008). Adiponectin promotes fatty acid oxidation, lowers triglyceride levels, increases insulin sensitivity, and inhibits inflammation by suppressing migration of monocytes/macrophages as well as their transformation into foam cells (Tomizawa, Hattori, Kasai, & Nakano, 2008). Its mechanism of action is not entirely clear but is at least in part related to its ability to directly stimulate production of nitric oxide, a potent vasodilator (Pajvani et al., 2004).

Cardiovascular risk factors

HTN is a known contributor to CMR and subsequent CVD. According to the seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure (2004), individuals with blood pressure (BP) in the range of 120/80–139/89 are considered prehypertensive with increased risk for future development of HTN and CVD.

Atherogenic dyslipidemia encompasses elevated triglycerides, increased LDL-C, and decreased HDL-C (Rasouli & Kiasari, 2006). Clinicians routinely perform lipid analysis to assess CMR. Wilson and colleagues (2008) have proposed that total levels of LDL-C and HDL-C are correlated with incident and recurrent CVD events regardless of gender.

CRP is an antimicrobial acute-phase reactant molecule indicative of systemic inflammation. It plays a direct role in promoting the inflammatory aspect of CVD, with levels (measured by high-sensitivity [hs]-CRP) <1, 1–3, and >3 mg/L distinguishing between low, moderate, and high cardiovascular risk, respectively (Pickup, 2004). Elevations in hs-CRP have been associated with hyperglycemia, hypertriglyceridemia, elevated apolipoprotein (apo)B and apoB/apoAI ratio, leukocytosis, and lowered HDL-C in stable coronary disease, indicating that hs-CRP interacts “multiplicatively with apoB and other variables of metabolic syndrome” (Rasouli & Kiasari, 2006, p. 971).

Psychosocial Risk Factors for CVD

Psychosocial factors believed to be associated with increased CMR and eventual CVD include perceived stress, depression, and social support.

Perceived stress

The combination of acute and chronic perceived stress over time increases the development and progression of CVD, although the mechanisms are complex and incompletely understood. It has long been known that stress creates hemodynamic, endocrine, and immune changes that increase susceptibility to CVD (Krantz & Manuck, 1984). Historically, the connection between stress and CVD was characterized by the idea of the “Type A personality.” This concept has since been recognized as an inaccurate, or at best incomplete, explanation. However, research has begun to provide valuable new insights. For example, one early study indicated that perceived stress is associated with increased abdominal adiposity in women with depression (Moyer et al., 1994). Working women, especially those with children, have been shown to exhibit higher perceived stress and norepinephrine levels than men (Lundberg & Frankenhaeuser, 1999). Additionally, increased perceived stress has been implicated as an important predictor of inflammatory activity in African Americans and females (McDade et al., 2006).

Depression

Depression negatively impacts quality of life and is an independent risk factor for the development and progression of metabolic syndrome and CVD (Frasure-Smith & Lesperance, 2006; Lowe, Hochlehnert, & Nikendei, 2006; Van der Kooy et al., 2007). Further, Anda and colleagues (1993) found that depressive symptoms were sufficient to increase CVD risk in the absence of a major depressive disorder. The incidence of depression is rising, carrying with it a 1.5–2.5-fold increase in CVD risk (Lowe et al., 2006). Despite increasing evidence of the strong etiologic and prognostic influence of depression on CVD, mechanisms remain unclear, especially in women. Potential mechanisms include depression-related fatigue and lack of interest, predisposing individuals to more sedentary lifestyles, decreased adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors and medical regimens as well as a concomitant decrease in heart rate variability, all of which increase the risk for cardiovascular events (Krantz & McCeney, 2002). Noteworthy for a comprehensive model of CMR, recent research supports the existence of immunological associations with depression, particularly elevated levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Dantzer, O’Connor, Freund, Johnson, & Kelley, 2008).

Social support

Social support (SS) has been associated with positive health outcomes after controlling for CVD risk factors and health risk behaviors such as nonadherence, while lack of SS has been shown to negatively impact cardiovascular health (Bland, Krogh, Winkelstein, & Trevisan, 1991; Trigo et al., 2005). SS may mediate stress responses that, over time, increase CVD risk, perhaps by facilitating coping through cognitive reappraisal, thereby attenuating neuroendocrine activation (Lepore, 1998). Seeman and McEwen (1996) found that positive, supportive relationships were associated with decreased cardiovascular and neurohormonal reactivity. In a prospective study by Vogt, Mullooly, Ernst, Pope, and Hollis (1992), after researchers controlled for obesity and HTN, individuals with higher perceived SS were less likely to experience a myocardial infarction. Heitman (2006) found that perceived SS fostered sustained changes in health behaviors in individuals with CVD risk, with research indicating there may be gender and race differences. In one study of 89 females and 60 males at high risk for or having CVD, investigators found that low SS was significantly associated with less life satisfaction, free time, and perceived health control, with females reporting higher negative mood state and lower perceived health control than males (Rueda & Perez-Garcia, 2006). As with perceived chronic stress, McDade and colleagues (2006) found low SS to be associated with elevated CRP levels in females and African Americans.

Spirituality

While the concepts of religiosity and spirituality are often used interchangeably or collectively in the literature, they are not the same. Religiosity is considered one possible aspect of spirituality. Religiosity and spirituality may, however, share similar mechanisms of action. Religiosity has been associated with improved health outcomes, particularly in CVD (Powell, Shahabi, & Thoresen, 2003). According to Folkman (1997), spirituality and religiosity enhance positive psychological states through facilitation of positive reappraisals of difficult situations. Although spirituality is thought to be an important mediator in disease, there is a paucity of research exploring the influence of spirituality on healthy individuals and in the primary prevention of disease.

Method

Participants

Following study approval by the Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) institutional review board, we prescreened potential participants for enrollment. Using flyers, pamphlets, and e-mail distributed through the VCU Health System and Richmond area, we recruited a total of 60 women, 41 of whom were eligible for enrollment. Eligible participants were healthy, premenopausal, non- or mildly-obese (maximum body mass index of 33, calculated using self-report of height and weight as acquired during medical appointment within 1 year prior to entering study) women aged 35–50 years with or without abdominal adiposity. Consistent with current guidelines, we defined abdominal adiposity as a WC greater than 35 inches (Alberti et al., 2009). Participating women were able to read and speak English, had self-reported histories of CVD in first-or second-degree relatives, and could designate a healthcare provider with whom to share their clinically applicable study results. We excluded individuals from participation if they had previously diagnosed CVD, Type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus, HTN, hyperlipidemia, polycystic ovarian syndrome, hyperthyroidism or hypothyroidism, morbid obesity, sleep apnea, or clinical depression. We also excluded those who had taken corticosteroids within 90 days of data collection.

Data Collection

Following informed consent and enrollment, we scheduled participants for a single study visit. We distributed written instructions for collecting salivary samples that included times for the four samples and directed participants to avoid eating around collection times (Neu, Goldstein, Gao, & Laudenslager, 2007). Participants collected four salivary samples for cortisol and DHEA measures the day before their study visit and presented fasting for data collection. Following the initial venipuncture at a healthcare office laboratory, they ate a plain bagel with one ounce of cream cheese. This provided a similar but more palatable carbohydrate load than traditional glucose tolerance testing (56 and 75 grams of carbohydrates, respectively; http://www.guttenplan.com; Stumvoll et al., 2000). Additionally, while not diagnostic of insulin resistance, it provided a lower carbohydrate load using a commonly consumed food, potentially allowing for an earlier indication of evolving insulin resistance. Participants completed a demographic data form and psychosocial instruments followed by a blood draw for 2-hr postprandial glucose and insulin levels. We averaged two BP measures taken during the data collection session.

Physiological Measures

Neuroendocrine

The neuroendocrine measures included salivary cortisol and DHEA, TSH and total T4, fasting and 2-hr postprandial glucose and insulin, and 25-hydroxy vitamin D. In keeping with the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), we calculated a surrogate measure of in vivo insulin sensitivity using fasting glucose and insulin levels ([Insulin0 × Glucose0] / 22.5).

Immune

The immune measures included the 17-plex results derived from a multiplex bead array system (Bio-Plex®) and high-molecular weight adiponectin (HMW).

Cardiovascular

Cardiovascular indicators included BP, fasting lipids (total cholesterol, LDL, HDL, cholesterol/ HDL ratio, triglycerides), and hs-CRP. While we excluded individuals with known HTN from the study, we measured BP to assess for pre-HTN.

Assays

The VCU School of Nursing Center for Biobeha-vioral Clinical Research laboratory processed salivary cortisol and DHEA as well as cytokine and adiponectin levels. Salivary cortisol reflects the biologically active, free fraction of cortisol. While there are measurement challenges, including sample contamination and inadequate sample volume among others, salivary cortisol is comparable to serum cortisol (Duplessis, Rascona, Cullum, & Yeung, 2010). In this study, it was preferable to serum cortisol because of ease of repeated measurements over a 24-hr period (Gozansky, Lynn, Laudenslager, & Kohrt, 2005). Additionally, we had participants collect a total of four saliva samples over 24 hr (30 min after arising, midday, afternoon, and evening) to assess diurnal cortisol patterns. We based our assay procedures on those of Laudenslager and colleagues (Neu et al., 2007). We determined levels of cytokines in cryopreserved plasma using a Bio-Plex suspension array system (Bio-Rad, Inc.) with a Bio-Rad 17-plex cytokine detection kit. We assayed adiponectin using the Bio-Plex system with the Bio-Rad human diabetes assay panel. The VCU Clinical Pathology Laboratory processed all other laboratory specimens using well-established and clinically approved assay procedures.

Psychosocial Measures

Perceived stress

We measured perceived stress using the 10-item Perceived Stress Scale (PSS), a self-report measure of the degree to which an individual perceived events in her life over the previous month to be stressful (Cohen, Karmarck, & Mermelstein, 1983). The range of scores on the PSS is 0–56, with higher scores indicating higher levels of perceived stress. Items assess how unpredictable, uncontrollable, and overloaded individuals find their lives. All items begin with the phrase, “In the past month, how often have you felt … ?” The PSS yields valid and reliable results across diverse populations (Cronbach’s α and test–retest reliability = .85).

Depression

We measured depressive symptoms using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale (CES-D; Radloff, 1977). The CES-D is a 20-item self-report instrument comprised of four factors assessing cognitive and affective components of depression. The CES-D has been widely used in urban and rural populations and cross-cultural studies of depressive symptoms. This instrument has very good construct validity, internal consistency, and test–retest reliability (Cronbach’s α = .91; Zumbo, Gelin, & Hubley, 2001). The CES-D has a range of scores of 0–60, with higher scores indicative of a higher number of depressive symptoms’ a total score above 16 may indicate a depressive disorder.

Social support

We measured SS using the revised Social Provisions Scale (SPS), a 24-item Likert-type scale measuring the perceived degree to which social relationships provide support across six dimensions of social support (Reed, 1986, 1987). Half of the items describe the presence of a type of support while the others describe the absence of support. The SPS has a range of 24–96, with a higher score indicating a greater degree of social support. Reliability (Cronbach’s α = .83–.94) as well as convergent and discriminant validity are strong in adult samples.

Spirituality

We assessed spirituality as a potential modifier of stress and CMR using the revised Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale (SIBS-R; Hatch, Burg, Naberhaus, & Hellmich, 1998). The original SIBS had high internal consistency, strong test–retest reliability, and good construct validity. Based on further instrument development (reliability, construct validity, and factor analysis), the instrument was revised to consist of 22 items and demonstrated high reliability (Cronbach’s α = .92), strong construct validity, and high test–retest reliability (r = .92). The range of scores is 22–154, with higher scores reflecting a higher degree of spiritual beliefs and actions. The SIBS is widely applicable and includes items such as “I set aside time for meditation and/or self-reflection” and “I have joy in my life because of my spirituality.” Its advantages over other spirituality instruments for the purpose of this study included a broader scope of the concept of spirituality, avoidance of terms of cultural and religious bias, and assessment of both beliefs and actions.

Data Analysis

We used two-sample t-tests to compare the study variables between two WC groups, checking the normality and homosce-dasticity assumptions for the t-test for each variable. We used log transformations to normalize fasting insulin and HOMA-IR values. Pearson’s correlation determined relationships between WC and study variables. Because of the relatively small sample in this pilot study, we minimized the Type II error rate by ignoring the multiplicity (i.e., no adjustment for multiple testing) and by setting the α at.10. All tests were two-sided; we have labeled p-values between .10 and .05 “marginally significant” and p-values of .05 and less “significant.” We used SAS v9.2 and JMP v8.0 for data analyses.

Results

Demographic Data and Lifestyle Factors

The study sample included 27 urban dwelling women without increased WC (≤35 inches; Group 1) and 14 with increased WC (>35 inches; Group 2). A total of 85.7% of the sample were White (n = 35) and 14.3% were African American (n = 6), with three African Americans in each group. The mean age was 43.55 (SD = 4.35) years in Group 1 and 44.73 (SD = 4.22) in Group 2. The average WC was 31.14 (SD = 2.51) inches in Group 1 and 37.24 (SD = 1.98) in Group 2. Mean BMI was 23.92 (SD = 2.47) kg/m2 in Group 1 and 29.64 (SD = 2.32) in Group 2. A total of 76.9% (n = 30 of 39) of the participants were employed at least part time, with 78% (n = 32) reporting an annual income of at least $40,000. In Group 1 60.9% (n = 25) had completed at least a college education compared with 26.8% in Group 2.

In Group 1, 34% (n = 14) of participants reported vitamin use compared with 14.6% (n = 6) in Group 2. Likewise, 31.7% (n = 13) of Group 1 reported prescription medication use compared to 19.5% (n = 8) of Group 2. Medications included oral contraceptives, antihistamines, proton-pump inhibitors, antibiotics, a β–blocker, and sumatriptan for migraine prevention, and antidepressants for mild menstrual mood disorders. The average number of daily servings of fruits and vegetables was four in both groups. Group 1 reported exercising an average of 2.9 days per week compared to 3.4 days in Group 2.

Group Comparisons

In our sample of premenopausal women with a family history of CVD, those with higher WC (Group 2) perceived significantly lower levels of social support, had significantly higher levels of postprandial blood glucose, triglycerides, TC to HDL ratio, and cytokines IL-5, IL-8, and granulocyte colony stimulating factor (G-CSF), and significantly lower levels of HDL-C and HMW adiponectin than those with lower WC (Group 1; Table 1). While their levels were still in the normal range, Group 2 exhibited significantly higher measures of both systolic and diastolic BP. Additionally, the average HOMA-IR indicated the presence of insulin resistance in Group 2 but not in Group 1. Group 2 had marginally significantly higher fasting blood glucose, LDL-C, and hs-CRP and marginally significantly lower levels of vitamin D. While Group 1 had higher levels of vitamin D, both groups exhibited vitamin D deficiency (normal range 32–100 ng/ml). There were no significant differences in levels of total cholesterol, salivary cortisol, salivary DHEA, thyroid function, perceived stress, depressive symptoms, or spirituality.

Table 1.

Cardiometabolic Risk (CMR) Indicators by Waist Circumference (WC) Group: Means ± Standard Error

| Variable | Group 1 (Normal WC) (n = 27) | Group 2 (High WC) (n = 15) | p Valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood glucose | |||

| Fasting | 86.26 ± 1.32 | 90.86 ± 2.01 | .056 |

| 2 hr postprandial | 88.41 ± 3.86 | 99.14 ± 3.44 | .045 |

| Insulin | |||

| Fasting | 4.20 ± 0.88 | 11.65 ± 2.77 | .0007b |

| 2 hr postprandial | 16.96 ± 1.80 | 38.01 ± 8.60 | .032 |

| LDL-C | 111.44 ± 4.66 | 129.21 ± 8.80 | .056 |

| HDL-C | 56.74 ± 2.04 | 48.21 ± 2.14 | .012 |

| TC to HDL ratio | 3.43 ± 0.16 | 4.22 ± 0.20 | .005 |

| Triglycerides | 76.56 ± 8.82 | 107.36 ± 11.82 | .046 |

| Total cholesterol | 189.74 ± 5.28 | 202.64 ± 11.37 | .316 |

| hs-CRP | 1.49 ± 0.38 | 3.33 ± 1.28 | .089 |

| IL-5 | 0.86 ± 0.11 | 2.89 ± 1.36 | .045 |

| IL-8 | 2.80 ± 0.23 | 4.17 ± 0.82 | .045 |

| G-CSF | 55.55 ± 9.09 | 93.17 ± 11.99 | .019 |

| Adiponectin HMW | 2485.22 ± 241.91 | 1509.80 ± 202.15 | .010 |

| Systolic blood pressure | 106.63 ± 2.03 | 116.21 ± 3.04 | .015 |

| Diastolic blood pressure | 69.67 ± 1.17 | 76.14 ± 1.80 | .006 |

| Depression: CES-D score | 8.63 ± 1.75 | 12.93 ± 2.43 | .158 |

| Stress: PSS score | 23.48 ± 1.15 | 25.14 ± 2.02 | .482 |

| Spirituality: SIBS-R score | 138.89 ± 3.05 | 128.71 ± 7.46 | .223 |

| Social support: SPS score | 84.11 ± 1.80 | 76.21 ± 2.50 | .030 |

| TSH | 1.85 ± 0.14 | 2.40 ± 0.49 | .297 |

| Total thyroxine (T4) | 7.50 ± 0.23 | 7.89 ± 0.52 | .512 |

| Vitamin D: 25-OH | 24.14 ± 1.97 | 18.49 ± 2.03 | .054 |

| Salivary cortisol | |||

| AM | 0.3909 ± 0.0362 | 0.3469 ± 0.0470 | .465 |

| Midday | 0.1226 ± 0.0107 | 0.1111 ± 0.0142 | .520 |

| Afternoon | 0.1165 ± 0.0227 | 0.0787 ± 0.0088 | .132 |

| Evening | 0.0516 ± 0.0078 | 0.0564 ± 0.0093 | .698 |

| Salivary DHEA | 1032.73 ± 141.06 | 1224.45 ± 152.40 | .368 |

| HOMA-IR | 15.80 ± 15.57 | 48.60 ± 12.93 | .0006b |

Note:

AM = Morning (ante meridiem) CES-D = Center for Epidemiologic Studies-Depression scale; DHEA = dehydroepiandrosterone; G-CSF = granulocyte colony stimulating factor; HLD-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HMW = high molecular weight adiponectin; HOMA-IR = homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; hs-CRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL = interleukin; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; PSS = Perceived Stress Scale; SIBS-R = Revised Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale; SPS = Social Provisions Scale; TC = total cholesterol; TSH = thyroid-stimulating hormone; 25-OH vitamin D = 25-hydroxy vitamin D.

From two-sided, two-sample t-test.

T-test calculated on the log transformed data.

WC Correlates

WC was significantly correlated with multiple indicators of CMR (Table 2).The correlations ranged from .31 to .55 (in absolute value) and all were statistically significant except for the cytokines IL-5 and IL-8. Positive correlations indicated that an increasing WC was related to an increase in BP, LDL-C, blood glucose and insulin, G-CSF, hs-CRP, and HOMA-IR, while negative correlations indicated that it was related to a decrease in HDL-C, adiponectin, and perceived social support (SPS).

Table 2.

Waist Circumference Correlation with Select Psychoneur-oimmunological (PNI) Variables for Cardiometabolic Risk (CMR)

| PNI Variables | R | p |

|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure | ||

| Systolic | .53 | .0004 |

| Diastolic | .55 | .0002 |

| LDL-C | .39 | .0120 |

| HDL-C | −.37 | .0175 |

| TC:HDL-C | .54 | .0003 |

| Triglycerides | .45 | .0032 |

| Blood glucose | ||

| Fasting | .48 | .0016 |

| 2 hr postprandial | .34 | .0284 |

| Insulin | ||

| Fasting | .43 | .0005 |

| Log fasting | .50 | .0009 |

| 2 hr postprandial | .53 | .0005 |

| G-CSF | .32 | .0378 |

| IL-5 | .22 | .1639 |

| IL-8 | .19 | .2529 |

| HMW adiponectin | −.54 | .0126 |

| Social support | −.31 | .0457 |

| hs-CRP | .37 | .0171 |

| HOMA-IR | .48 | .0016 |

| Log HOMA-IR | .54 | .0004 |

Note: G-CSF = granulocyte colony stimulating factor; HLD-C = high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; HMW = high molecular weight adiponectin; HOMA-IR = homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; hs-CRP = high-sensitivity C-reactive protein; IL = interleukin; LDL-C = low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; TC = total cholesterol.

Discussion

Because it has a clinically important magnitude of relationship with CMR, WC was the variable we chose to differentiate the two groups in the present study. Several variables were significantly correlated with WC. Of the psychosocial variables, SS was negatively correlated with WC. Significantly, despite the absence of any clinical diagnoses associated with CMR, Group 2 exhibited significant differences from Group 1 in multiple physiological indicators of evolving CMR. Group 2 had higher diastolic and systolic BP as well as blood glucose and insulin levels. Group 2 also demonstrated less ability to process physiologic stress, as evidenced by significantly increased postprandial insulin levels, signifying greater glycemic excursion, a risk factor for the development of CVD. Additionally, HOMA-IR scores were dramatically higher in Group 2, a finding consistent with the presence of insulin resistance.

Some of the relationships and mechanisms among indicators in this study are clear while others are not. For example, despite substantial theoretical and scientific data supporting the impact of various psychosocial phenomena on disease risk, most psychosocial indicators in this study were not significantly different between the two groups. While increased levels of perceived stress have been shown to activate the HPA axis and chronic stress has been associated with disease development, participants in the present study did not demonstrate significant differences in perceived stress, a known contributor to CVD. Additionally, while spirituality has been proposed to mediate CMR, there were no differences among participants in this study. Perhaps small sample size contributed to the lack of significant relationships between these psychosocial variables and WC. Additionally, while theoretically and psychometrically sound, the R-SIBS is a new measure with limited use in clinical studies. Further psychometric evaluations are needed with populations with CMR and related clinical issues.

In terms of the physiological variables, increased WC was correlated with insulin resistance and increased triglyceride levels as well as lower adiponectin levels. Additionally, increased WC was correlated with elevated systolic and diastolic BP. Inflammation was correlated with increased WC as well, as evidenced by decreased adiponectin and elevated hs-CRP levels. The cytokine G-CSF was positively correlated with increased WC, but it is anti-inflammatory by traditional classification, while we found no significant correlations in the nominal pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-5 and IL-8. These findings are not entirely consistent with previous findings related to anti- and pro-inflammatory cytokines, a difference that is, perhaps, in part attributable to small sample size as well as the limitations of the current classification of cytokines by these overly simplified typologies for inflammatory activity.

Hypothyroidism has been associated with indicators of CMR, yet in the present study thyroid function was not associated with increased WC. Although TSH is now performed by an ultrasensitive assay and most often used to evaluate and diagnose thyroid disease, it does not reflect hormone levels or peripheral conversion of T4 to triiodothyronine (T3). While total T4 is a direct measure of the capacity of the thyroid gland to produce thyroid hormone, free hormone levels represent bioactive thyroid hormone in the blood. T4 is converted to T3, the hormone capable of cell receptor binding, as well as reverse T3, which appears to be inactive. According to recent recommendations, free T4 and T3 may yield more information about actual thyroid function and its potential impact on CMR, but comparative studies are sparse to date (Roos et al., 2007).

Interestingly, the demographic and descriptive data in the present study indicate that the two groups of participating women were quite similar except for the presence of abdominal adiposity. This finding along with the lack of research examining underlying mechanisms associated with CVD risk suggest there may be genetic factors regulating allostatic load. Future work should include examination of the role of genetic factors.

The most significant limitations of this study include most notably a small sample size and lack of racial diversity making it less representative of the population of women at risk for CVD. Additionally, future work will include objective measurement of height and weight versus self-report as used in this pilot study. Future research with larger, more diverse samples including genetic factors is needed to further illuminate the role of more recent physiological as well as psychosocial factors in the development of CVD.

Conclusions

The data from the present study support what is currently known about abdominal adiposity, CMR, and CVD risk in terms of physiological variables. Additionally, this study provides a theoretical and research-driven PNI model and support for considering psychosocial variables, particularly social support, when assessing CMR and CVD risk in women. The model, particularly the inclusion of allostatic load, provides a sound framework for considering the effects of cumulative stress while allowing inclusion of the idea of early identification versus assessing and managing CMR after significant medical diagnoses exist. Measurement models combining both psychosocial and physiological variables need to be tested in order to further specify risk factors, particularly those that may be early, modifiable markers.

This study may provide the necessary impetus to educate women and health care providers about earlier assessment and management of CMR in women with increasedWC. More generally, the findings suggest that more comprehensive conceptualization and refinement of measures of CMR may be useful for identifying and reducing CMR and ultimately CVD in women.

Based on a PNI framework, we have reconceptualized assessment of CMR in women to contain both physiological and psychosocial stress factors. Allostatic load provides a model for appreciating the cumulative effects of stress factors on the development of abdominal adiposity and systemic inflammation. This expanded view may facilitate earlier identification and modification of CMR. Depressive Sxs = depressive symptoms; DHEA = dehydroepiandrosterone; Fasting and 2 hr PP BS and insulin = fasting and 2-hour postprandial blood sugar and insulin; TSH = thyroid stimulating hormone; T4 = thyroxine; 25-OH vitamin D = 25-hydroxy vitamin D; BP = blood pressure; CRP = C-reactive protein; CMR = cardiometabolic risk; CVD = cardiovascular disease.

Acknowledgment

Our deepest gratitude to each participant and colleague who contributed to this work.

Funding

Funding provided by National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of Health (P20 NR008988).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interests with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adachi R, Honma Y, Masuno H, Kawana K, Shimomura I, Yamada S, Makishima M. Selective activation of vitamin D receptor by lithocholic acid acetate, a bile acid derivative. Journal of Lipid Research. 2005;46:46–57. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400294-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adam T, Epel E. Stress, eating and the reward system. Physiology and Behavior. 2007;91:449–458. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti KG, Eckel RH, Grundy SM, Zimmet PZ, Cleeman JI, Donato,Smith SC. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation. 2009;120:1640–1645. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandraki K, Piperi C, Kalofoutis C, Singh J, Alaveras A, Kalofoutis A. Inflammatory process in type 2 diabetes: The role of cytokines. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2006;1084:89–117. doi: 10.1196/annals.1372.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Heart Association. Women and cardiovascular disease—statistics. 2010 Retrieved May 7, 2010, from http://www.americanheart.org/presenter.jhtml.

- Anda R, Williamson D, Jones D, Macera C, Eaker E, Glassman A, Marks J. Depressed affect, hopelessness, and the risk of ischemic heart disease in a cohort of U.S. adults. Epidemiology. 1993;4:285–294. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Appels A, Mulder P. Excess fatigue as a precursor to myocardial infarction. European Heart Journal. 1988;9:758–764. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/9.7.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldini V, Mastropasqua M, Francucci CM, D’Erasmo E. Cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis. Journal of Endo-crinological Investigation. 2005;28:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastard J, Maachi M, Lagathu C, Kim M, Caron M, Vidal H, … Feve B. Recent advances in the relationship between obesity, inflammation, and insulin resistance. European Cytokine Network. 2006;17:4–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedinghaus J, Leshan L, Diehr S. Coronary artery disease prevention: What’s different for women? American Family Physician. 2001;63:1393–1396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behre CJ, Fagerberg B, Hulten LM, Hulthe J. The reciprocal association of adipocytokines with insulin resistance and C-reactive protein in clinically healthy men. Metabolism. 2005;54:439–444. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beltowski J. Adiponectin and resistin—new hormones of white adipose tissue. Medical Science Monitor. 2003;9:RA55–RA61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bland SH, Krogh V, Winkelstein W, Trevisan M. Social network and blood pressure: A population study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1991;53:598–607. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199111000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canaris GJ, Manowitz NR, Mayor G, Ridgway EC. The Colorado Thyroid Disease Prevalence Study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2000;160:526–534. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H, Montagnani M, Funahashi T, Shimomura I, Quon MJ. Adiponectin stimulates production of nitric oxide in vascular endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278:45021–45026. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307878200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Karmarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24:385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dantzer R, O’Connor JC, Freund GG, Johnson RW, Kelley KW. From inflammation to sickness and depression: When the immune system subjugates the brain. Nature Reviews: Neuroscience. 2008;9:46–57. doi: 10.1038/nrn2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamantopoulos EJ, Andreadis EA, Tsourous GI, Katsanou PM, Georgiopoulos DX, Dimitriadis GD, Raptis SA. Intermediate post-challenge hyperglycemia in overweight and obese subjects: A new marker of impaired glucose regulation? Angiology. 2006;57:709–716. doi: 10.1177/0003319706295479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duplessis C, Rascona D, Cullum M, Yeung E. Salivary and free serum cortisol evaluation. Military Medicine. 2010;175:340–346. doi: 10.7205/milmed-d-09-00166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Empana J. Adiponectin isoforms and cardiovascular disease: The epidemiological evidence has just begun. European Heart Journal. 2008;29:1307–1315. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45:1207–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00040-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasure-Smith N, Lesperance F. Recent evidence linking coronary heart disease and depression. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;51:730–737. doi: 10.1177/070674370605101202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozansky WS, Lynn JS, Laudenslager ML, Kohrt WM. Salivary cortisol determined by enzyme immunoassay is preferable to serum total cortisol for assessment of dynamic hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal activity. Clinical Endocrinology. 2005;63:336–341. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2005.02349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guest CB, Yan G, O’Connor J, Freund GG. Obesity and immunity. In: Ader R, editor. Psychoneuroimmunology. 4th ed. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2007. pp. 993–1011. [Google Scholar]

- Haffner SM. Relationship of metabolic risk factors and development of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. Obesity. 2006;14:121S–127S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffner SM. Managing cardiometabolic risk: Do we have all the answers? Canadian Journal of Medicine. 2007;120:S10–S16. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatch RL, Burg MA, Naberhaus DS, Hellmich LK. The Spiritual Involvement and Beliefs Scale: Development and testing of a new instrument. Journal of Family Practice. 1998;46:476–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heine RJ, Balkau B, Ceriello A, Del PS, Horton ES, Taskinen MR. What does postprandial hyperglycaemia mean? Diabetic Medicine. 2004;21:208–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitman LK. The influence of social support on cardiovascular health in families. Family and Community Health. 2006;29:131–142. doi: 10.1097/00003727-200604000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holick MF. Vitamin D: Important for prevention of osteoporosis, cardiovascular heart disease, type 1 diabetes, autoimmune diseases, and some cancers. Southern Medical Journal. 2005;98:1024–1027. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000140865.32054.DB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes SD, Krantz DS, Rogers H, Gottdiener J, Contrada RJ. Mental stress and coronary artery disease: A multidisciplinary guide. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases. 2006;49:106–122. doi: 10.1016/j.pcad.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard BV, Campbell L, Allen C, Black H, Passaro M, Rodabough RJ, Wagenknecht LE. Insulin resistance and weight gain in postmenopausal women of diverse ethnic groups. International Journal of Obesity Related Metabolic Disorders. 2004;28:1039–1047. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu F, Manson J, Stampfer M, Colditz G, Liu S, Solomon C, Willett W. Diet, lifestyle, and the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus in women. New England Journal of Medicine. 2001;345:790–797. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa010492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. 2004 (NIH Publication No. 04-5230). Retrieved from the National Heart, Blood, and Lung Institute, National Institutes of Health website: http://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/guidelines/hypertension/jnc7full.htm.

- Jones DS, Bland JS, Quinn S. What is functional medicine? In: Jones D, editor. Textbook of functional medicine. Gig Harbor, WA: Institute for Functional Medicine; 2005. pp. 5–14. [Google Scholar]

- Krantz DS, Manuck SB. Acute psychophysiologic reactivity and risk of cardiovascular disease: A review and methodologic critique. Psychological Bulletin. 1984;96:435–464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krantz DS, McCeney MK. Effects of psychological and social factors on organic disease: A critical assessment of research on coronary heart disease. Annual Review of Psychology. 2002;53:341–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ. Problems and prospects for the social support-reactivity hypothesis. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 1998;20:257–269. doi: 10.1007/BF02886375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe B, Hochlehnert A, Nikendei C. Metabolic syndrome and depression. Therapeutische Umschau. 2006;63:521–527. doi: 10.1024/0040-5930.63.8.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundberg U, Frankenhaeuser M. Stress and workload of men and women in high-ranking positions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 1999;4:142–151. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.4.2.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martini LA, Wood RJ. Vitamin D status and the metabolic syndrome. Nutrition Reviews. 2006;64:479–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2006.tb00180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massoudi MS, Meilahn EN, Orchard TJ, Foley TP, Jr., Kuller LH, Costantino JP, Buhari AM. Prevalence of thyroid antibodies among healthy middle-aged women. Findings from the thyroid study in healthy women. Annals of Epidemiology. 1995;5:229–233. doi: 10.1016/1047-2797(94)00110-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuzawa Y, Funahashi T, Kihara S, Shimomura I. Adiponectin and metabolic syndrome. Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology. 2004;24:29–33. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000099786.99623.EF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDade TW, Hawkley LC, Cacioppo JT. Psychosocial and behavioral predictors of inflammation in middle-aged and older adults: The Chicago Health, Aging, and Social Relations Study. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2006;68:376–381. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000221371.43607.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS. Protective and damaging effects of stress mediators. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1998;840:33–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb09546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosca L, Banka CL, Benjamin EJ, Berra K, Bushnell C, Dolor RJ, Wenger NK. Evidence-based guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women: 2007 update. Circulation. 2007;115:1481–1501. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.181546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer AE, Rodin J, Grilo CM, Cummings N, Larson LM, Rebuffe-Scrive M. Stress induced cortisol response and fat distribution in women. Obesity Research. 1994;2:255–262. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1994.tb00055.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neu M, Goldstein M, Gao D, Laudenslager ML. Salivary cortisol in preterm infants: Validation of a simple method for collecting saliva for cortisol determination. Early Human Development. 2007;83:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto Y, Kihara S, Funahashi T, Matsuzawa Y, Libby P. Adiponectin: A key adipocytokine in metabolic syndrome. Clinical Science. 2006;110:267–278. doi: 10.1042/CS20050182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olszanecka-Glinianowicz M, Zahorska-Markiewicz B, Janowska J. The effect of weight loss on serum concentrations of nitric oxide, TNF-alpha and soluble TNF-alpha receptors. Endokrynologia Polska. 2006;57:487–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pajvani UB, Hawkins M, Combs TP, Rajala MW, Doebber T, Berger JP, Scherer PE. Complex distribution, not absolute amount of adiponectin, correlates with thiazolidinedione-mediated improvement in insulin sensitivity. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:12152–12162. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickup JC. Inflammation and activated innate immunity in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:813–823. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.3.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pi-Sunyer FX. The relation of adipose tissue to cardiometa-bolic risk. Clinical Cornerstone. 2006;8:S14–S23. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(06)80040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell LH, Shahabi L, Thoresen CE. Religion and spirituality: Linkages to physical health. American Psychologist. 2003;58:36–52. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.58.1.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measures. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rana T, Li Y, Manson JE, Hu FB. Adiposity compared with physical inactivity and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:53–58. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmusson AM, Vasek J, Lipschitz DS, Vojvoda D, Mustone ME, Shi Q, Charney DS. An increased capacity for adrenal DHEA release is associated with decreased avoidance and negative mood symptoms in women with PTSD. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1546–1557. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasouli M, Kiasari AM. Interactions of serum hsCRP with apoB, apoB/AI ratio and some components of metabolic syndrome amplify the predictive values for coronary artery disease. Clinical Biochemistry. 2006;39:971–977. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2006.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed PG. Religiousness among terminally ill and healthy adults. Research in Nursing and Health. 1986;9:35–42. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770090107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed PG. Spirituality and well-being in terminally ill hospitalized adults. Research in Nursing and Health. 1987;10:335–344. doi: 10.1002/nur.4770100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie SA, Connell JM. The link between abdominal obesity, metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular disease. Nutrition, Metabolism, and Cardiovascular Disease. 2006;17:319–326. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2006.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos A, Baker S, Links T, Gans R, Wolffenbuttel B. Thyroid function is associated with components of the metabolic syndrome in euthyroid subjects. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;92:491–496. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rueda B, Perez-Garcia AM. Gender and social support in the context of cardiovascular disease. Women & Health. 2006;43:59–73. doi: 10.1300/J013v43n01_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Munoz F, Garcia-Macedo R, Alcon-Aguilar F, Cruz M. Adipocytokines, adipose tissue and its relationship with immune system cells. Gaceta médica de Mexico. 2005;141:505–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schleithoff SS, Zittermann A, Tenderich G, Berthold HK, Stehle P, Koerfer R. Vitamin D supplementation improves cytokine profiles in patients with congestive heart failure: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;83:754–759. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeman TE, McEwen BS. Impact of social environment characteristics on neuroendocrine regulation. Psychosomatic Medicine. 1996;58:459–471. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199609000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stumvoll M, Mitrakou A, Pimenta W, Jenssen T, Yki-Jarvinen H, VanHaeften T, Gerich J. Use of oral glucose tolerance test to assess insulin release and insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 2000;23:295–301. doi: 10.2337/diacare.23.3.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilg H, Moschen AR. Role of adiponectin and PBEF/vis-fatin as regulators of inflammation: Involvement in obesity-associated diseases. Clinical Science. 2008;114:275–288. doi: 10.1042/CS20070196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa A, Hattori Y, Kasai K, Nakano Y. Adiponectin induces NF-kappaB activation that leads to suppression of cytokine-induced NF-kappaB activation in vascular endothelial cells: Globular adiponectin vs. high molecular weight adiponectin. Diabetes and Vascular Disease Research. 2008;5:123–127. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2008.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trigo M, Silva D, Rocha E. Psychosocial risk factors in coronary heart disease: Beyond type A behavior. Revista Portu-guesa de Cardiologia. 2005;24:261–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van der Kooy K, van Hout H, Marwijk H, Marten H, Stehouwer C, Beekman A. Depression and the risk for cardiovascular diseases: Systematic review and metaanalysis. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2007;22:613–626. doi: 10.1002/gps.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanitallie TB. Stress: A risk factor for serious illness. Metabolism. 2002;6:40–45. doi: 10.1053/meta.2002.33191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieth R, Kimball S. Vitamin D in congestive heart failure. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2006;83:731–732. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/83.4.731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt TM, Mullooly JP, Ernst D, Pope CR, Hollis JF. Social networks as predictors of ischemic heart disease, cancer, stroke and hypertension: Incidence, survival and mortality. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 1992;45:659–666. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90138-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson P, Pencina M, Jacques P, Selhub J, D’Agostino R, O’Donnell C. C reactive protein and reclassification of cardiovascular risk in the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes. 2008;1:92–97. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.108.831198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun AJ, Lee PY, Doux JD. Are we eating more than we think? Illegitimate signaling and xenohormesis as participants in the pathogenesis of obesity. Medical Hypotheses. 2006;76:36–40. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachariae R. Psychoneuroimmunology: A bio-psycho-social approach to health and disease. Scandanavian Journal of Psychology. 2009;50:645–651. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zumbo BD, Gelin MN, Hubley AM. Psychometric study of the CES-D: Factor analysis and DIF; Paper session presented at the International Neuropsychological Society’s 29th Annual Meeting; Chicago, IL. Feb, 2001. [Google Scholar]