Abstract

Objectives

Family members and friends can be an important source of self-management support for older adults with chronic diseases. We characterized the U.S. population of potential and current “disease management supporters” for people with chronic illness who are ADL-independent, the help that supporters could provide, and barriers to increasing support.

Methods

Nationally-representative survey of U.S. adults (N=1,722).

Results

44% of respondents (representing 100 million US adults) help a family member or friend with chronic disease management; another 9% (representing 21 million US adults) are willing to start. Most are willing to assist with key tasks such as medication use and communicating with providers, although they feel constrained by privacy concerns and a lack of patient health information.

Discussion

The majority of U.S. adults already help or would be willing to help one of their family members or friends with chronic illness care. Supporters' specific concerns could be addressed through innovative programs.

Keywords: family relations, social support, chronic illness, self-management, caregiving

Introduction

Older adults with illnesses such as diabetes, heart disease, and chronic lung disease need to maintain daily self-management routines and manage complex interactions with the health care system in order to control symptoms and avoid complications. Many of these chronically ill adults also have cognitive impairment (Biessels, Staekenborg, Brunner, Brayne, & Scheltens, 2006; Vogels, Scheltens, Schroeder-Tanka, & Weinstein, 2007) or low health literacy (Paasche-Orlow, Parker, Gazmararian, Nielsen-Bohlman, & Rudd, 2005), making disease management even more of a challenge. Providing care for chronically-ill adults strains healthcare resources, and fragmented clinical systems are ill-equipped to offer patients the level of self-management assistance recommended by treatment guidelines (Bayliss et al., 2007).

Family members and friends are an important but often overlooked source of support for chronically ill adults. More than half of adults with diabetes or heart failure regularly involve family members in day-to-day disease management tasks, such as taking medications and tracking indicators of their health status (i.e. glucose levels or daily weights) (Rosland, Heisler, Choi, Silveira, & Piette, 2010; Silliman, Bhatti, Khan, Dukes, & Sullivan, 1996). Half of all chronically ill patients regularly bring family members into the exam room for their medical visits, and these visit companions often provide key support for patient-provider communication (Rosland, Piette, Choi, & Heisler, 2011; Wolff & Roter, 2011). Chronically-ill adults who have higher levels of family support have better self-management regimen adherence, better control of their chronic conditions, lower hospitalization rates, and greater satisfaction with their medical care (DiMatteo, 2004; Gallant, 2003; Lett et al., 2005; Luttik, Jaarsma, Moser, Sanderman, & van Veldhuisen, 2005; Zhang, Norris, Gregg, & Beckles, 2007; Strom & Egede, 2012).

In contrast to caregivers for people with substantial physical or cognitive limitations, who usually focus their assistance on activities of daily living (ADLs; e.g., bathing or dressing), family members and friends helping less functionally impaired adults manage chronic illnesses such as diabetes or arthritis often serve as “disease management supporters.” While these supporters may do some disease-management tasks “for” the person with chronic illness, they most typically assist the person with day-to-day decisions about medication and symptom management, help to coordinate health care among multiple providers, and facilitate behavior changes such as improvements in diet or health status monitoring (Rosland, 2009). Many disease management support tasks can be accomplished by a family member or friend who lives at a distance and, in fact, adults with chronic illnesses increasingly live apart from people in their social network who could support their chronic disease care (Piette, Rosland, Silveira, Kabeto, & Langa, 2010).

Prior studies estimate over nine million informal caregivers help other adults with basic activities of daily living (ADLs) in the United States (Alecxih, Zeruld, & Olearczyl, 2001), but the number of Americans supporting disease management for less functionally impaired adults with common chronic conditions, such as heart disease or diabetes, is unknown (Giovennetti & Wolff, 2010). Programs under development have the potential to mobilize disease management supporters and help them effectively support home self-management and patient-provider communication (Rosland & Piette, 2010; Wolff, 2012). In order to know whether these programs for disease management supporters have the potential to address the growing gap between what chronically-ill adults need and what health systems can provide, we need information about how prevalent disease management supporters are on a national scale, the characteristics of supporters that affect the focus and feasibility of programs, and supporters' interest in shifting or expanding support roles.

We conducted a nationally-representative survey to estimate the number of U.S. adults who are in contact with functionally-independent adult relatives and friends who have common chronic medical conditions that require significant day-to-day management. We describe the number of U.S. adults who currently support someone's chronic illness care, the number who are willing but not currently providing chronic illness support, and the characteristics of supporters that might affect program reach and design. We also describe the specific disease management tasks that current and potential supporters are willing to engage in and the barriers they see to increasing their support for their chronically ill family and friends. Finally, we examine differences between supporters who live with their support recipient versus those who live in separate households.

Design and Methods

Survey of U.S. Adults

We surveyed 1,722 U.S. adults age 18 years old and older from a nationally-representative Internet panel. Caucasians, African Americans and Latinos were sampled so that they would represent 50%, 25%, and 25% of respondents respectively. Participants were recruited through Knowledge Networks (KN), a research firm that maintains a large, representative survey panel of American adults by providing Internet access and computing equipment to panel members at no cost. KN's panel is very similar to the U.S. population with respect to race/ethnicity, age, gender, educational attainment, and income (Chang & Krosnick, 2009; Knowledge Networks Inc, 2010). The American Association for Public Opinion Research validated KN's probability-based and address-based sampling as the best approach to obtaining population based estimates (Baker et al., 2010). Several academic and government organizations, including the U.S. Centers for Disease Control, use the KN Panel for population-based research (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2010). KN members are able to choose from among several surveys offered each month. KN continues to invite new panel members to respond to a particular survey until the target number and type of respondents is reached. This sampling method can lead to lower overall response rates than more traditional sampling methods, but takes advantage of the ease of Internet sampling to reach sample size and socio-demographic targets. The survey “completion rate” (Callegaro & DiSogra, 2008) is a particularly appropriate measure of survey response when using this method.

Following tenets of social support theory, specifically that social support is a function of a person's social network infrastructure, the survey was designed to first generate a comprehensive list of the respondents' social network, then ask about the support functions given to that network (Ell, 1984). Survey respondents were asked to identify all community-dwelling social network members with whom they have contact at least once per month. Contacts who needed assistance with basic activities of daily living (ADLs; such as eating, dressing, bowel/bladder management) were removed from the social network list. We then asked respondents to indicate which of the remaining contacts were known to have been “diagnosed by a health care provider” with one or more of the following chronic illnesses: diabetes, heart disease, chronic lung disease, arthritis, or depression. Detailed questions were asked about the respondent's involvement in the health care of one chronically ill contact who lived with the respondent and one who lived apart from the respondent. When the respondent reported more than one contact in each group, the contact for whom the respondent said they were most willing to provide support was chosen as the subject of these detailed questions. (See Supplemental Material for details on survey flow and question wording.) Items chosen for specific support tasks and barriers to support were based on social cognitive theory constructs that knowledge, skills, outcome expectancies and competing demands posed by the person's environment are key determinants of health management behaviors (Bandura, 2004).

Definitions

All respondents reporting regular contact with one or more activities of daily living (ADL)-independent chronically-ill adults were considered potential disease management supporters (Table 1). Willing disease management supporters were defined as the subset of potential supporters who reported they would be likely to provide a basic level of support for health management to at least one of their chronically ill contacts (specifically, talking to the chronically ill contact about their health for 15 minutes once a week), whether or not they were currently doing so. Current disease management supporters were defined as the subset of willing supporters who already help at least one of their contacts with health-related tasks such as managing medications, tracking test results, or regularly attending the contact's medical appointments. The subset of willing supporters who did not help any of their contacts with disease management were considered non-involved. In-household supporters are the subset of current supporters who support at least one chronically ill person who lives in their household (they may also support others who do not live with them). Out-of-household supporters are the subset of current supporters who reported supporting only chronically ill adults who do not live in their household (thus this category is mutually exclusive with in-household supporters).

Table 1. Definitions Used in Study.

| Potential Disease Management Supporter: A US adult who has at least monthly contact with a community-dwelling adult family member or friend that: (a) has diabetes, heart disease, chronic lung disease, arthritis, or depression; and (b) does not need help with activities of daily living. |

| Chronically Ill Contact: A community-dwelling adult friend or relative of the respondent, who has at least monthly contact with the respondent, has one of five chronic illnesses (above), and who does not need help with activities of daily living. |

| Willing Disease Management Supporter: The subset of Potential Disease Management Supporters who are willing to provide a basic level of health care support to at least one of their chronically ill contacts. |

| Specifically, “willing” is indicated by a rating of 6 or higher to this question: “Imagine you could help this person better manage their health problems by talking with them about their health for 15 minutes* once a week. On a scale from 1-10, where 1 is not likely at all and 10 is extremely likely: how likely would you be to help them in this way?” |

| Current Disease Management Supporter: The subset of Willing Disease Management Supporters who regularly help a chronically ill contact with health related tasks. |

| Specifically, respondents who |

| (a) identify themselves as “the main person who helps the contact with health related tasks like managing medicines, cooking healthy food, and keeping track of doctor's appointments“ |

| or |

| (b) help their contact with health related tasks “like filling prescriptions and managing medicines, arranging medical appointments, filling out medical forms, or making decisions about health care” at least one day in the last 3 months |

| or |

| (c) regularly discuss their contact's health with their contact |

| or |

| (d) regularly go with their contact into the exam room for medical appointments |

| or |

| (e) talk to their contact's health care provider once per year or more |

Survey Analysis

All analyses describing respondent characteristics used statistical weights to adjust estimates to reflect the U.S. adult population with respect to gender, age, race/ethnicity, geographic location, education, and Internet access. To determine the number of American adults who provide various levels of disease management support, weighted percents were applied to U.S. Census Bureau 2009 population estimates. Analyses describing chronically ill contacts are adjusted for clustering by respondent.

Results

A total of 1722 respondents completed the survey (completion rate 53%). Forty seven percent of respondents were men, and the average respondent was 48 years old (standard deviation 17 years). Thirty percent of respondents had at most a high school degree, and 58% had attended at least some college or technical school. (See Supplemental Tables 2 and Table3 for detailed respondent and non-respondent characteristics.)

U.S. Adults with Chronically Ill Contacts

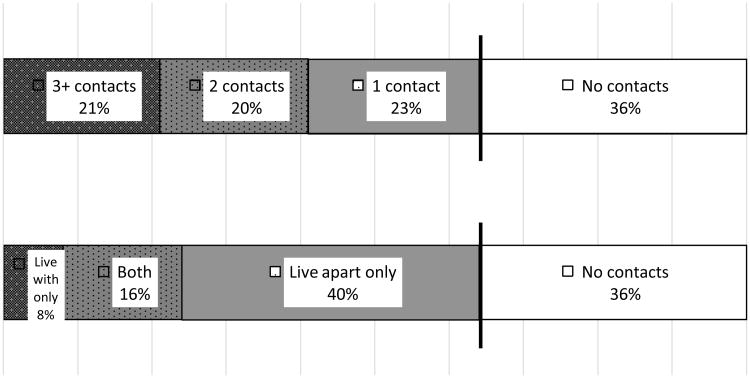

The majority of respondents (64%, representing 149 million US adults) were potential disease management supporters for one or more chronically ill adults, i.e. they had at least monthly contact with one or more activities of daily living (ADL)-independent adults with a chronic illness (Figure 1). Sixty-four percent of potential disease management supporters had contact with two or more family or friends with chronic diseases and 88% had one or more chronically ill contacts living outside of their household. As shown in Table 2, women were more likely to be potential supporters than men (70% of women were potential supporters vs. men 59%, p<0.01), as were respondents over 50 years old (68% vs. under 50 years old 61%, p<0.01), and respondents living in rural areas (70% vs. those in metro areas 63%, p=0.04).

Figure 1. Percent of U.S. Adults Who Have at Least Monthly Contact with a Functionally Independent Adult with a Common Chronic Illness.

Percent of respondents, weighted. Both = have chronically ill contacts both within and outside of the respondent's household.

Table 2. Proportion of Respondents Who Are Potential and Willing Disease Management Supporters, By Respondent Characteristic (weighted).

| % of Respondents Who are Potential Supporters | P value* | % of Potential Supporters Who are Willing Supporters | P value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Respondents | 64% | n/a | 82% | n/a |

| Gender | ||||

| Women | 70% | 82% | ||

| Men | 59% | <0.01 | 82% | 0.93 |

| Age | ||||

| >=50 years old | 61% | 84% | ||

| <50 years old | 68% | <0.01 | 81% | 0.16 |

| Education | ||||

| <High School Degree | 63% | 81% | ||

| High School Degree | 61% | 81% | ||

| Attended some college | 64% | 83% | ||

| >=Bachelor's Degree | 69% | 0.09 | 84% | 0.83 |

| Yearly Income | ||||

| < $25,000 | 64% | 82% | ||

| $25,000-50,000 | 61% | 79% | ||

| $50,000-85,000 | 64% | 84% | ||

| >$85,000 | 69% | 0.09 | 84% | 0.29 |

| Employment Status‡ | ||||

| Currently Employed | 63% | 83% | ||

| Not Employed | 58% | 90% | ||

| Retired or Disabled | 70% | <0.01 | 78% | <0.01 |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White | 67% | 81% | ||

| African-American | 61% | 84% | ||

| Latino | 61% | 0.06 | 83% | 0.51 |

| MSA Category | ||||

| Rural/Nonmetro | 70% | 87% | ||

| Metro | 63% | 0.04 | 81% | 0.053 |

| Self-Rated Health Status | ||||

| VG/Excellent | 84% | |||

| Good/Fair/Poor | N/A | 80% | 0.12 | |

| Physical Limitations | ||||

| A Little or None | 82% | |||

| Sometimes or More | N/A | 82% | 0.83 |

All data weighted to US adult population characteristics. All percents are row percents.

P value for Pearson's chi-square test of differences in % Potential Supporters between the listed subcategories of respondents.

P value for Pearson's chi-square test of differences in % Willing Supporters between the listed subcategories of Potential Supporters.

Currently employed includes full-time employee, part-time employee, and self-employed. Not employed includes those laid-off and those looking for work.

Most potential disease management supporters (82%, representing 121 million U.S. adults) were willing to provide regular support to at least one of their chronically ill family members or friends; 77% of these willing supporters are willing to support a contact who is 50 years old or older (Table 2).Among potential supporters, men and women were equally willing to provide disease management support. Similarly, willingness did not vary by educational attainment, income, racial/ethnic group, or health status. However, more (90%) of those who were not working (laid-off or looking for work) and less (78%) of those who were retired or disabled were willing to provide support (p<0.01).

Current Disease Management Supporters

Eighty-three percent of people willing to provide disease management support (representing 43% of U.S. adults or 100 million people) reported already helping one or more of their friends or family members manage chronic illness. Current disease management supporters who lived with at least one of their support recipients (in-household supporters) were similar to disease management supporters who lived apart from all of their support recipients (out-of-household supporters) in terms of age, socioeconomic status, racial/ethnic group, and health status (Table 3). In-household supporters were evenly split between men and women. Out-of-household supporters were more often women (65%) than men and were less likely than in-household supporters to be living in rural areas (15% vs. 29%).

Table 3. Characteristics of Willing Disease Management Supporters (weighted).

| Current Supporters (N=738) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Total Willing Supporters (N=892) | Willing Non-Involved (N=154)1 | In-Household Supporters (N=293)2 | Out-of-Household Supporters (N=445)3 | P value4 | |

| Female | 55% | 52% | 65% | 33% | <0.01 |

| Age | |||||

| <50 years old | 57% | 54% | 52% | 77% | |

| 50-64 years old | 30% | 31% | 34% | 19% | |

| >65 years old | 13% | 15% | 14% | 4% | <0.01 |

| Education | |||||

| No college | 41% | 50% | 39% | 32% | |

| Attended some college | 29% | 27% | 28% | 37% | |

| Bachelor's Degree or higher | 30% | 24% | 34% | 30% | 0.14 |

| Yearly Income | |||||

| < $25,000 | 23% | 24% | 25% | 14% | |

| $25,000-50,000 | 24% | 27% | 23% | 25% | |

| $50,000-85,000 | 26% | 26% | 27% | 25% | |

| >$85,000 | 26% | 23% | 25% | 36% | 0.34 |

| Employment Status5 | |||||

| Currently Employed | 59% | 55% | 56% | 72% | |

| Not Employed | 18% | 19% | 16% | 19% | |

| Retired or Disabled | 24% | 26% | 27% | 9% | <0.01 |

| Race/Ethnicity | |||||

| White | 56% | 54% | 58% | 57% | |

| African-American | 22% | 24% | 21% | 15% | 0.51 |

| Latino | 22% | 22% | 21% | 28% | |

| Rural | 19% | 29% | 15% | 11% | <0.01 |

| Self-Rated Health Status | |||||

| VG/Excellent | 46% | 44% | 43% | 60% | |

| Good/Fair/Poor | 54% | 56% | 57% | 40% | 0.04 |

| Physical Limitations | |||||

| A Little or None | 75% | 77% | 70% | 86% | |

| Sometimes or More | 25% | 23% | 30% | 14% | 0.02 |

All data weighted to US adult population characteristics. All cell entries are column percents.

Represents 40 million US adults.

Represents 60 million US adults.

Represents 21 million US adults.

P value for Pearson's chi-square test of differences between the three subcategories of Willing Disease Management Supporters.

Currently employed includes full-time employee, part-time employee, and self-employed. Not employed includes those laid-off and those looking for work.

Willing disease management supporters answered detailed questions about 1,102 chronically ill contacts, 29% of whom were receiving assistance from the respondent within the same household, and 55% of whom were receiving assistance but living in a separate household (Table 4). In-household support recipients were most often spouses (66%), while out-of -household support recipients were most often parents (34%) and siblings (32%). Sixty-two percent of disease management support recipients living outside of the respondent's home had one or more additional supporters assisting with their disease management.

Table 4. Characteristics of Chronically Ill Contacts of Willing Disease Management Supporters.

| Total Contacts of Willing Supporters (N=1102)1 | Receiving Support and Living in the Respondent's Household (N=315) | Receiving Support and Living in a Separate Household (N=605) | Not Receiving Support from Willing Supporter (N=182) | P value2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship to respondent3 | |||||

| Spouse/partner | 21% | 66% | 1% | 6% | |

| Parent or Parent-In-Law | 29% | 16% | 34% | 32% | <0.01 |

| Sibling or Sibling-In-Law | 25% | 5% | 32% | 34% | |

| Other Relatives/Friends | 26% | 12% | 33% | 28% | |

| Married | 61% | 71% | 57% | 58% | <0.01 |

| Living with respondent | 32% | 100% | 0% | 21% | <0.01 |

| Another disease management supporter identified | 45% | 11% | 62% | 49% | <0.01 |

| Age >50 years | 71% | 66% | 77% | 63% | <0.01 |

| Contact's chronic illness4 | |||||

| Diabetes | 36% | 32% | 36% | 41% | 0.13 |

| Heart Disease | 19% | 17% | 22% | 13% | 0.02 |

| Lung Disease | 14% | 18% | 12% | 12% | 0.04 |

| Arthritis | 38% | 43% | 39% | 27% | <0.01 |

| Depression | 25% | 29% | 24% | 23% | 0.24 |

| Emergency Department visit or hospitalized/last year | 38% | 35% | 43% | 23% | <0.01 |

| Get help with instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) from respondent5 | 46% | 74% | 38% | 20% | <0.01 |

| Distance from respondent6 | |||||

| <5 miles | 25% | 25% | 26% | ||

| 5-20 miles | 25% | 25% | 29% | ||

| 21-100 miles | 15% | 15% | 13% | ||

| >100 miles | 35% | N/A | 36% | 33% | 0.37 |

| Frequency of visits with the respondent7 | |||||

| Once per week or more | 28% | 29% | 24% | 0.24 | |

| Once per month or more | 56% | N/A | 56% | 56% | 0.96 |

| Frequency of telephone contact with the respondent7 | |||||

| Once per week or more | 62% | 67% | 42% | <0.01 | |

| Once per month or more | 92% | N/A | 95% | 81% | <0.01 |

| Frequency of email/web contact with the respondent** | |||||

| Once per week or more | 37% | 23% | 17% | 0.11 | |

| Once per month or more | 22% | N/A | 38% | 34% | 0.36 |

All percents are column percents

In the main survey a total of 2118 contacts of willing supporters were identified. This total represents the 1102 contacts that detailed questions were asked about. These 1102 contacts are divided into the 3 subgroups in the remaining columns.

P values from Pearson's chi-square test of differences between the three chronically ill contact categories, adjusted for clustering by respondent.

Among the 2118 total chronically ill contacts of willing supporters identified, 11% were spouses/partners, 27% were parents/parents-in-law, 20% were siblings/siblings-in-law, and 42% were other relatives/friends.

Contact can have more than one chronic illness.

IADLs are Independent Activities of Daily Living, and were defined in this survey as housework, shopping, managing bills/finances, or transportation.

Contacts not receiving support and living within 5 miles of the respondent include those living in the respondent's household.

Only asked of out of home contacts; once per month or more includes those once per week or more

Out-of-household support recipients were more likely to have heart disease and to have visited the emergency department or hospital in the last year than in-household support recipients. Most (74%) of in-household support recipients and 38% of out-of-household support recipients were receiving help from the respondent with instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as shopping, managing finances, or housework, in addition to help with chronic illness management.

Half of out-of-household support recipients lived within 20 miles from their disease management supporter, while 36% lived more than 100 miles away. Two-thirds of out-of-household support recipients talked to their supporter by phone at least once a week, and 23% were in contact by email or website at least once a week.

Willing Disease Management Supporters Not Currently Involved in Disease Management

Seventeen percent of willing disease management supporters, representing 21 million Americans, reported that they were not currently supporting the care of their chronically-ill contacts. Compared to active disease management supporters, these willing but non-involved supporters were more often male, younger, living in urban areas, employed, and in better health (Table 3). Willing but non-involved supporters were similar in educational attainment and income to current disease management supporters.

Among chronically-ill contacts not receiving disease management support from willing respondents, 21% lived in the respondent's household, and 63% were 50 years old or more (Table 4). According to respondents, more than half (51%) of contacts not receiving assistance did not have anyone else assisting with their health care. Contacts of willing non-involved supporters were less likely than contacts of current supporters to have a known emergency department or hospital stay in the last year. Over half of the contacts who were not receiving support and lived outside of the respondent's household lived within 20 miles of their potential supporter, while 33% lived more than 100 miles away. Contacts who were not receiving assistance were in touch with their willing supporter in-person and by email just as frequently as out-of-household contacts receiving assistance, and 42% of contacts not receiving support talked with the respondent by phone at least once a week.

Willingness to Help With Specific Chronic Disease Management Tasks

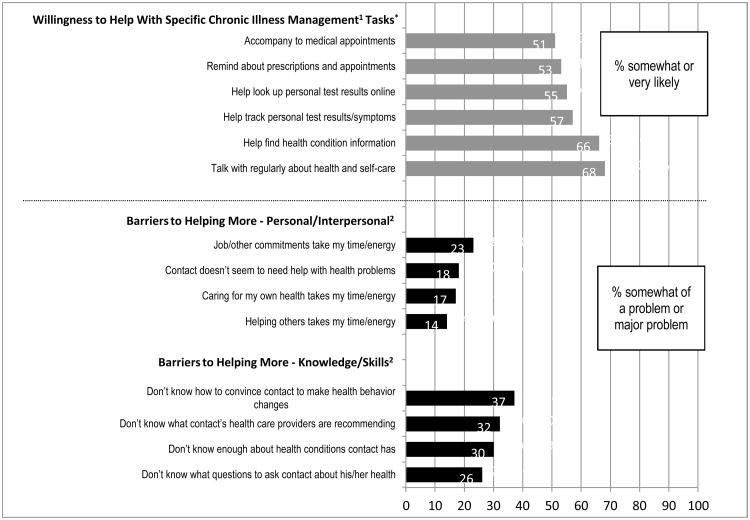

Willing disease management supporters (including those who were and were not currently providing assistance) indicated that they were open to helping their contacts with a variety of health care needs (Figure 2). About half of willing supporters were willing to accompany their chronically ill family member or friend to medical appointments (51%) or remind the person about medication-taking and clinical appointments (53%). Over half (57%) were willing to help their contact track test results and symptoms. About two-thirds were willing to help with finding health information (66%) or by talking regularly with the person about their health and self-care (69%).

Figure 2. Disease Management Supporter Willingness to Help with Specific Chronic Illness Management Tasks and Barriers to Helping More with Chronic Illness Care.

1Willingness Data represents 1066 chronically ill contacts of 860 respondents

2Barriers Data represents 1052 chronically ill contacts of 850 respondents

Barriers to Increasing Help with Chronic Disease Management

When barriers were noted, willing supporters most often felt they lacked information about the contact's health conditions and self-care goals (Figure 2). For example, not knowing the recommendations of the contact's health care providers was noted by 32% of willing supporters (and specifically 18% of active in-home supporters, 36% of active out-of-home supporters, and 39% of willing but not involved supporters). Lacking information about the contact's health condition or “what questions to ask” was noted by over a quarter of willing supporters (26% and 30% of all respondents, respectively). Thirty-seven percent reported concerns about knowing how to help their chronically-ill contact make behavior changes. Less than 25% of willing supporters reported personal or interpersonal barriers to providing disease management support, such as competing demands on their time.

Discussion

The majority (64%) of U.S. adults have regular contact with one or more chronically ill friends or family members (73% of whom are over 50 years old) and are willing to help them care for their chronic conditions. Both currently-active disease management supporters and those willing to start supporting chronically ill family and friends represent an important resource that could help support day-to-day care for adults with chronic conditions.

While we found that many people are already involved at some level in disease management support, they may be more effective if the health care system facilities their success in current support roles and their participation in new roles. Disease management supporter programs could help these supporters assist chronically ill individuals with medication adherence, home health testing, symptom management, and healthy behavior changes. Past research trials suggest that simply including a support person in patient education sessions is insufficient to improve outcomes (Hogan, Linden, & Najarian, 2002). However, programs that help family members optimize specific supporter roles may be more effective in improving patient outcomes. For example, such programs help family members set specific goals for supporting chronically ill loved ones or teach supporters techniques to help support recipients cope with chronic symptoms (Rosland, et al., 2010). Such strategies and tools could also address barriers to disease management support reported by participants in the current study. For example, respondents reported that they lacked knowledge about contacts' chronic conditions and disease management regimen. Programs could provide supporters with lay person-focused assessment tools for identifying key changes in the contact's health status and up-to-date information about support recipients' test results, prescriptions and care plans. Respondents in this study also reported they lacked the skills needed to help chronically ill family and friends make health behavior changes. Programs could train supporters to help recipients set concrete behavior goals, provide autonomy-supportive encouragement (Williams, Deci, & Ryan, 1998), and monitor their progress towards achieving their goals. Finally, new programs could develop methods to address supporter concerns about patient privacy – for example, by assisting patients and supporters in defining the boundaries of use for patient health care information, and by documenting patient permission to share personal health information in their medical record.

Notably, 51% of willing supporters reported a willingness to accompany chronically-ill contacts to medical appointments. A recent review found that when patients are accompanied into outpatient visits they have better information recall and are more satisfied with their medical encounter (Wolff & Roter, 2011). Chronic illness programs could encourage patients to bring supporters to medical appointments, give supporters tools to help them assist the patient in preparing for visits and recording visit information, and train physicians in techniques to more effectively communicate with supporters during visits (McDaniel, Campbell, Hepwroth, & Lorenz, 2005).

This study suggests that large numbers of supporters live outside of the chronically ill person's household, but still play key roles in disease management. Potentially valuable strategies for supporting these relationships include the use of mobile health technologies or the Internet for sharing support recipient-specific information and facilitating communication among the recipient, distant supporter, and the clinical team. Importantly, our findings indicate that out-of-household disease management supporters often share support activities with another family member or friend. Programs could help these networks coordinate support by delineating each supporter's role and by facilitating communication among the supporters and formal caregivers involved in the recipient's disease management.

Our findings indicate that approximately 21 million U.S. adults are willing but not yet providing disease management support for ADL-independent friends and family members who have chronic illnesses. Engaging these potential supporters could be an important and cost-effective approach to improving the quantity and quality of disease management care. Unlike the traditional informal caregiver, willing non-involved supporters are more often young, male, urban residents who have better health status and less physical limitations than current supporters. Evidence suggests male and female caregivers provide different types of help, with men more likely to help coordinating appointments and health insurance, and women more likely to provide more direct personal care assistance (Metlife Mature Market Institute, 2003; National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP, 2004).Therefore, men may be particularly amenable to performing the types of tasks that are more common in supporting functionally-independent people with chronic diseases. Most of these willing supporters are employed, and may find mobile or Internet-based tools to facilitate support particularly useful. In general, the current study suggests that chronically-ill contacts who are not currently receiving assistance are less ill -- for example they have fewer hospitalizations and a lower prevalence of heart disease and arthritis. However, adults with chronic illness of all severities, and those with diabetes in particular (who make up 41% of the contacts of these willing but not involved supporters) could benefit from increased social support (Gallant, 2003; van Dam et al., 2005).

Our estimate of the number of active chronic disease management supporters (100 million U.S. adults) is higher than estimates of the number of informal caregivers providing daily personal care (up to 52 million U.S. adults) (US Department of Health and Human Services, 1998). It is possible that disease management support is “early caregiving”, in that the same people providing disease management support earlier in a family member's life might later assist the same family member with basic activities of daily living. If true, the health care system could have an important opportunity to engage these future caregivers early, in order to help them become more skilled at chronic illness management, and then respond to the changing roles they play in patients' care.

Several factors should be taken into account when interpreting these national estimates. Our definition of “supporter” was intentionally broad, and included regularly discussing the chronically ill adult's health care with that person or the person's health care provider, in addition to direct help with disease management tasks. Respondents were sampled only from the three most common U.S. racial/ethnic groups, and the proportion of those of other race/ethnicities who are engaged in self-management support may be different than what is reported here. Also, this study focused on five common chronic illnesses associated with a significant level of daily disease management activity – social network members without these conditions but with other chronic illnesses such as hypertension or hyperlipidemia were not included. To minimize respondent burden, detailed questions about disease management support were asked for only one in-home chronically-ill contact and one out-of home contact. Therefore, if some contacts not asked about were receiving support from the respondent, we have underestimated the number of current supporters. If all contacts not asked about were receiving support from the respondent (the maximum change possible), our estimated number of current U.S. disease management supporters would increase from 100 million to 111 million. Finally, information on the characteristics of chronically-ill contacts was reported by the respondent, so accuracy is limited by the respondent's familiarity with that person, and answers to some questions (such as willingness to provide support) could be affected by social-desirability bias.

In summary, our findings indicate that the majority of U.S. adults are in regular contact with someone with chronic illness, and most are already helping adult family and friends with disease management. Many additional adults would be willing to provide such support, but have concerns about their ability to be effective that could be addressed through new programs and new technological support. Given that support from family and friends is linked to better chronic illness self-management and outcomes, innovative programs designed to facilitate disease management support should be a top priority for health care policy, practice, and outreach.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH National Center for Research Resources [Award Number UL1RR024986]. Ann-Marie Rosland is a VA Health Services Research and Development (HSRD&D) Career Development Awardee. John Piette is a VA HSR&D Senior Research Career Scientist.

We thank Wyndy Wiitala and Shannon Hunter for assistance with data management and analysis.

References

- Alecxih LMB, Zeruld S, Olearczyl B. Characteristics of caregivers based on the survey of income and program participation: The Lewin Group 2001 [Google Scholar]

- Baker R, Blumberg SJ, Brick JM, Couper MP, Courtright M, Dennis JM, Dillman D, Frankel MR, Garland P, Grovers RM, Kennedy C, Krosnick J, Lavrakas PJ. Research Synthesis: AAPOR Report on Online Panels. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2010;74(4):711–781. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior. 2004;31(2):143–164. doi: 10.1177/1090198104263660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayliss EA, Bosworth HB, Noel PH, Wolff JL, Damush TM, McIver L. Supporting self-management for patients with complex medical needs: recommendations of a working group. Chronic Illness. 2007;3(2):167–175. doi: 10.1177/1742395307081501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biessels GJ, Staekenborg S, Brunner E, Brayne C, Scheltens P. Risk of dementia in diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5(1):64–74. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70284-2. doi: S1474-4422(05)70284-2 [pii] 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70284-2 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callegaro M, DiSogra C. Computing response metrics for online panels. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2008;72(5):1008–1032. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Interim results: influenza A (H1N1) 2009 monovalent and seasonal influenza vaccination coverage among health-care personnel - United States, August 2009-January 2010. MMWR. 2010;59(12):357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Krosnick JA. National Surveys via RDD Telephone Interviewing Versus the Internet Comparing Sample Representativeness and Response Quality. Public Opinion Quarterly. 2009;73:641–678. [Google Scholar]

- DiMatteo MR. Social support and patient adherence to medical treatment: a meta-analysis. Health Psychol. 2004;23(2):207–218. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.2.207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ell K. Social Networks, Social Support, and Health Status: A Review. Social Service Review. 1984;58(1):133–149. [Google Scholar]

- Gallant M. The influence of social support on chronic illness self-management: a review and directions for research. Health Education & Behavior. 2003;30(2):170–195. doi: 10.1177/1090198102251030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannetti ER, Wolff JL. Cross-Survey Differences in National Estimates of Numbers of Caregivers to Disabled Older Adults. Milbank Quarterly. 2010;88(3):310–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2010.00602.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan BE, Linden W, Najarian B. Social support interventions: Do they work? Clinical Psychology Review. 2002;22(3):381–440. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(01)00102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowledge Networks Inc. KnowledgePanel: Processes & Procedures Contributing to Sample Representativeness & Tests to Self-Selection Bias,March 2010. 2010 from http://www.knowledgenetworks.com/ganp/docs/KnowledgePanelR-Statistical-Methods-Note.pdf.

- Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Strauman TJ, Robins C, Sherwood A. Social support and coronary heart disease: epidemiologic evidence and implications for treatment. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2005;67(6):869–878. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188393.73571.0a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luttik ML, Jaarsma T, Moser D, Sanderman R, van Veldhuisen DJ. The importance and impact of social support on outcomes in patients with heart failure: an overview of the literature. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2005;20(3):162–169. doi: 10.1097/00005082-200505000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel S, Campbell T, Hepwroth J, Lorenz A. Family Oriented Primary Care. 2nd. New York: Springer; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Metlife Mature Market Institute. The Metlife Study of Sons at Work Balancing Employment and Eldercare. New York: Metropolitan Life Insurance Company; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP. Caregiving in the US. Bethesda, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Paasche-Orlow MK, Parker RM, Gazmararian JA, Nielsen-Bohlman LT, Rudd RR. The prevalence of limited health literacy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(2):175–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40245.x. doi: JGI40245 [pii] 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.40245.x . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piette JD, Rosland AM, Silveira M, Kabeto M, Langa KM. The case for involving adult children outside of the household in the self-management support of older adults with chronic illnesses. Chronic Illn. 2010;6(1):34–45. doi: 10.1177/1742395309347804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosland AM. Sharing the Care:The Role of Family in Chronic Illness Retrieved 08-16-2009. 2009 from http://www.chcf.org/documents/chronicdisease/FamilyInvolvement_Final.pdf.

- Rosland AM, Heisler M, Choi H, Silveira M, Piette JD. Family influences on self management among functionally independent adults with diabetes or heart failure: Do family members hinder as much as they help? Chronic Illness. 2010;6(1):22–33. doi: 10.1177/1742395309354608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosland AM, Piette JD. Emerging models for mobilizing family support for chronic disease management: A structured review. Chronic Illness. 2010;6:7–21. doi: 10.1177/1742395309352254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosland AM, Piette JD, Choi H, Heisler M. Family and Friend Participation in Primary Care Visits of Patients with Diabetes or Heart Failure: Patient and Physician Determinants and Experiences. Medical Care. 2011;49(1):37–45. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181f37d28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silliman RA, Bhatti S, Khan A, Dukes KA, Sullivan LM. The care of older persons with diabetes mellitus: families and primary care physicians. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(11):1314–1321. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strom J, Egede L. The Impact of Social Support on Outcomes in Adult Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: A Systematic Review. Current Diabetes Reports. 2012;12(6):769–81. doi: 10.1007/s11892-012-0317-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Health and Human Services. Informal Caregiving: Compassion in Action. Washington DC; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- van Dam HA, van der Horst FG, Knoops L, Ryckman RM, Crebolder HF, van den Borne BH. Social support in diabetes: a systematic review of controlled intervention studies. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59(1):1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogels RL, Scheltens P, Schroeder-Tanka JM, Weinstein HC. Cognitive impairment in heart failure: a systematic review of the literature. Eur J Heart Fail. 2007;9(5):440–449. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.11.001. doi: S1388-9842(06)00384-9 [pii] 10.1016/j.ejheart.2006.11.001 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams GC, Deci EL, Ryan RM. Building health-care partnerships by supporting autonomy: Promoting maintained behavior change and positive health outcomes. In: Suchman A, Hinton-Walker P, Botelho RJ, editors. Partnerships in healthcare: Transforming relational process. Rochester: University of Rochester Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL, Roter DL. Family presence in routine medical visits: A meta-analytical review. Soc Sci Med. 2011;72(6):823–831. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff JL. Family Matters in Health Care Delivery. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1529–30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X, Norris SL, Gregg EW, Beckles G. Social support and mortality among older persons with diabetes. Diabetes Educator. 2007;33(2):273–281. doi: 10.1177/0145721707299265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.