Distinct double-strand RNA binding domains of Dicer-like1 are important in binding of primary microRNAs and protein-protein interactions.

Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are a class of small regulatory RNAs that are found in almost all of the eukaryotes. Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) miRNAs are processed from primary miRNAs (pri-miRNAs), mainly by the ribonuclease III-like enzyme DICER-LIKE1 (DCL1) and its specific partner, HYPONASTIC LEAVES1 (HYL1), a double-strand RNA-binding protein, both of which contain two double-strand RNA-binding domains (dsRBDs). These dsRBDs are essential for miRNA processing, but the functions of them are not clear. Here, we report that the two dsRBDs of DCL1 (DCL1-D1D2), and to some extent the second dsRBD (DCL1-D2), complement the hyl1 mutant, but not the first dsRBD of DCL1 (DCL1-D1). DCL1-D1 is diffusely distributed throughout the nucleoplasm, whereas DCL1-D2 and DCL1-D1D2 concentrate in nuclear dicing bodies in which DCL1 and HYL1 colocalize. We show further that protein-protein interaction is mainly mediated by DCL1-D2, while DCL1-D1 plays a major role in binding of pri-miRNAs. These results suggest parallel roles between C-terminal dsRBDs of DCL1 and N-terminal dsRBDs of HYL1 and support a model in which Arabidopsis pri-miRNAs are recruited to dicing bodies through functionally divergent dsRBDs of microprocessor for accurate processing of plant pri-miRNAs.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs; approximately 21–22 nucleotides) are a class of small, regulatory RNAs that are involved in multiple biological processes in almost all of the eukaryotes (Reinhart et al., 2000; Carrington and Ambros, 2003; Molnár et al., 2007). MiRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II into stem loop long primary transcripts (pri-miRNAs). In animals, the pri-miRNAs are first cropped in the nucleus by Drosha and its partner DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene8, a double-strand RNA (dsRNA)-binding protein (dsRBP), to generate the fold-back precursor miRNAs (Han et al., 2004a; Landthaler et al., 2004; Zeng et al., 2005). After exportin-5-mediated export to the cytoplasm (Yi et al., 2003; Lund et al., 2004), the precursor miRNAs are cut into the miRNA/miRNA* (passenger strand of miRNA) duplexes by Dicer and its partner TAR RNA-binding protein2, a dsRBP (Chendrimada et al., 2005). In plants, both of the cleavage steps occur in the nucleus through a single ribonuclease (RNase) III family protein, DICER-LIKE1 (DCL1), with the assistance of a specific dsRBP, HYPONASTIC LEAVES1 (HYL1), in the nucleus (Han et al., 2004b; Kurihara and Watanabe, 2004; Kurihara et al., 2006). Other proteins involved include SERRATE (Yang et al., 2006; Montgomery and Carrington, 2008), the nuclear cap-binding complex (Laubinger et al., 2008), RNA-binding proteins DAWDLE, TOUGH, and MODIFIER OF SNC1, 2 (Yu et al., 2008; Ren et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2013), a transcription factor Negative on TATA less2/VIRE2-INTERACTING PROTEIN2 (Wang et al., 2013), and C-TERMINAL DOMAIN PHOSPHATASE-LIKE1 (CPL1)/FIERY2, which dephosphorylates HYL1 for its optimal activities (Manavella et al., 2012). DCL1 and HYL1 colocalize and interact with each other in discrete nuclear bodies, known as nuclear dicing (d)-bodies, while SE and CPL1 partially localize in d-bodies (Fang and Spector, 2007; Song et al., 2007; Manavella et al., 2012).

In addition to DCL1, three other Dicer-like proteins (DCL2–DCL4) are encoded in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana) genome (Schauer et al., 2002). DCL4 acts with DRB4 to produce small interfering RNAs (Kurihara et al., 2006; Nakazawa et al., 2007; Curtin et al., 2008; Fukudome et al., 2011). The Dicer-like proteins contain C-terminal dsRNA-binding domains (dsRBDs). It was known that the two N-terminal dsRBDs of HYL1 are able to rescue the hyl1 mutant phenotype and sufficient for the functions of wild-type HYL1 protein (Wu et al., 2007). However, how the two dsRBDs in DCL1 and two dsRBDs in its corresponding partner HYL1 coordinately functioned in miRNA biogenesis is not clear (Hiraguri et al., 2005).

In this study, we found that the two dsRBDs of DCL1 (DCL1-D1D2), and, to some extent, the second dsRBD (DCL1-D2), complemented the hyl1 mutant, but not the first dsRBD of DCL1 (DCL1-D1). In addition, we revealed that the main function of DCL1-D1 is for binding pri-miRNAs, while DCL1-D2 is for protein-protein interaction. We proposed a model in which the Arabidopsis pri-miRNAs are recruited to d-bodies through functionally divergent dsRBDs of microprocessor proteins. Thus, our results provided molecular insights into the functioning of dsRBDs in the microprocessor DCL1/HYL1.

RESULTS

Complementation of hyl1 by C-Terminal dsRBDs of DCL1

DCL1 contains two N-terminal nuclear localization signals, a DEXD/H-box RNA helicase domain, a DUF283 domain, a PAZ domain, two RNaseIII domains (RNaseIIIa and RNaseIIIb), and two dsRBDs (Fig. 1A). Sequence alignment of dsRBDs from DCL1, HYL1, and human small RNA processing proteins shows similarity and divergence among these dsRBDs (Supplemental Fig. S1). To address the functions and relationships among these dsRBDs, we amplified the first (DCL1-D1), second (DCL1-D2), and both of the two C-terminal dsRBDs (DCL1-D1D2) of DCL1 and fused in frame with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP), respectively (Fig. 1A). These fusions were first transformed into the dcl1-9 mutant, which harbors a transfer DNA insertion in the second dsRBD of DCL1. T2 transgenic lines in background of homozygous dcl1-9/dcl1-9 were identified by PCR, and no phenotype recovery were observed in these plants (Supplemental Table S1), indicating that the C-terminal dsRBDs are integral parts for the DCL1 holoenzyme.

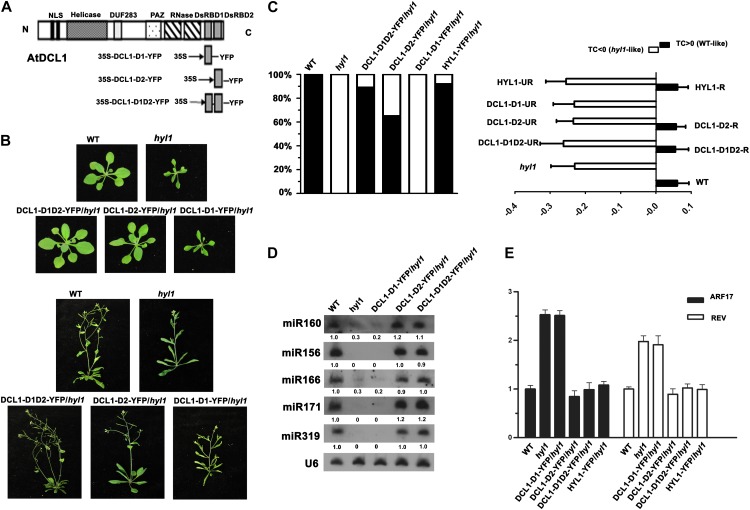

Figure 1.

The complementation of hyl1 phenotype by C-terminal dsRBDs of DCL1. A, Schematic representation of DCL1 featured domains and constructs. The locations of the protein domains are indicated by the labeled boxes. The constructs of 35S::DCL1-D1-YFP, 35S::DCL1-D2-YFP, and 35S::DCL1-D1D2-YFP are shown below. B, Visual phenotypes of the wild type (WT), hyl1, DCL1-D1D2-YFP/hyl1, DCL1-D2-YFP/hyl1, and DCL1-D1-YFP/hyl1 grown for 21 d (top two rows) and 40 d (bottom two rows). C, Proportion of complemented transgenic plants within T1 population (left) and the TC indices of the fourth leaves of wild-type, hyl1, and transgenic lines (right). The TC index is defined as TC = (lm–pw)/pw or TC = (pw–lm)/pw, where lm is the distance between the lateral margins of incurved leaves and pw is the pressed leaf width, according to upward or downward leaf incurvature. The proportion of recovery of the hyl1 mutant is calculated by TC index (left). The HYL1-YFP/hyl1, DCL1-D1D2-YFP/ hyl1, and DCL1-D2-YFP/ hyl1 transgenic lines are grouped into two classes, recovered (R) and unrecovered (UR), according to the TC values. The TC indices of wild-type (n = 22), hyl1 (n = 23), HYL1-YFP/hyl1 recovered plants (HYL1-R, n = 22), HYL1-YFP/hyl1 unrecovered plants (HYL1-UR, n = 2), DCL1-D1D2-YFP/hyl1 recovered plants (DCL1-D1D2-R, n = 17), DCL1-D1D2-YFP/hyl1 unrecovered plants (DCL1-D1D2-UR, n = 2), DCL1-D2-YFP/hyl1 recovered plants (DCL1-D2-R, n = 13), DCL1-D2-YFP/hyl1 unrecovered plants (DCL1-D2-UR, n = 7), and DCL1-D1-YFP/hyl1 (n = 25) plants are shown. D, Northern blotting of miR156, miR160, miR166, miR171, and miR319 in wild-type, hyl1, DCL1-D1-YFP/hyl1, and DCL1-D2-YFP/hyl1 and DCL1-D1D2-YFP/hyl1 recovered plants. U6 was used as a loading control. E, Real-time PCR analysis of miRNA target genes ARF17 and REV in wild-type, hyl1, DCL1-D1-YFP/hyl1, and DCL1-D2-YFP/hyl1, DCL1-D1D2-YFP/hyl1, and HYL1-YFP/hyl1 recovered plants. ACTIN2 was used for data normalization.

Next, we transformed DCL1-D1-YFP, DCL1-D2-YFP, and DCL1-D1D2-YFP into hyl1-2 mutant plants. Hyl-1-2 is a null allele harboring a transfer DNA insertion in the first dsRBD and exhibits multiple phenotypes, including hyponastic rosette leaves, small stature, abnormal sensitivities to hormones, and low levels of miRNAs (Lu and Fedoroff, 2000; Han et al., 2004b; Vazquez et al., 2004). Within T1 transgenic plant population, similar to transgenic plants expressing HYL1-YFP in hyl1 background in which 91.7% (22/24) plants showed recovery of the hyl1 phenotype, in DCL1-D1D2-YFP/hyl1 plants, 89.5% (17/19) of them complemented the hyl1 phenotype, as shown in visual phenotypes at different growth stages (Fig. 1B) and transverse curvature (TC) index of the fourth rosette leaf (Fig. 1C), which was previously used to quantify the rescue of the phenotype of the hyl1 mutant (Wu et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2010). To a lesser extent, 65% (13/20) of plants expressing DCL1-D2-YFP in hyl1 background complemented hyl1 phenotypes. By contrast, no phenotype recovery was observed for DCL1-D1-YFP/hyl1 plants (0/25; Fig. 1, B and C; Supplemental Table S1).

We then tested the accumulation of mature miRNAs in these transgenic plants. Northern-blot analysis showed that five miRNAs evaluated (miR156, miR160, miR166, miR171, and miR319) were almost restored to the same levels as that of the wild type in DCL1-D2-YFP/hyl1 and DCL1-D1D2-YFP/hyl1 recovered lines but not in DCL1-D1-YFP/hyl1 lines (Fig. 1D). The levels of miRNAs in DCL1-D2-YFP/hyl1 unrecovered transgenic lines were similar to those in the hyl1 mutant (Supplemental Fig. S2). We also tested the mRNA levels of a miRNA165/166-targeted gene, REVOLUTA (REV), and a miRNA160-targeted gene, AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR17 (ARF17). The increased mRNA levels of REV and ARF17 in the hyl1 mutant were down-regulated by introducing DCL1-D2-YFP and DCL1-D1D2-YFP to hyl1 mutant plants, but not DCL1-D1-YFP (Fig. 1E). In addition, we carried out in vitro pri-miRNA processing assays and found that immunoprecipitated protein complexes containing DCL1-D1D2 or DCL1-D2, but not DCL1-D1, were able to process an in vitro transcribed pri-miRNA (pri-miRNA171a) into 21-nucleotide mature miRNA171a (Supplemental Fig. S3).

The Subnuclear Localization of dsRBDs of DCL1

We then observed the subcellular localization of DCL1-D1-YFP, DCL1-D2-YFP, and DCL1-D1D2-YFP. In transgenic plants expressing DCL1-D1-YFP, DCL1-D2-YFP, or DCL1-D1D2-YFP in the hyl1 mutant background, DCL1-D1-YFP distributed diffusely throughout nucleoplasm. By contrast, DCL1-D2-YFP and DCL1-D1D2-YFP were enriched in round nuclear bodies in addition to diffuse signals in nucleoplasm (Fig. 2A). Similar localization patterns were observed in tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) leaf cells when these fusions were transiently expressed (Supplemental Fig. S4). These nuclear bodies remind us of d-bodies in which DCL1 and HYL1 are concentrated (Fang and Spector, 2007).

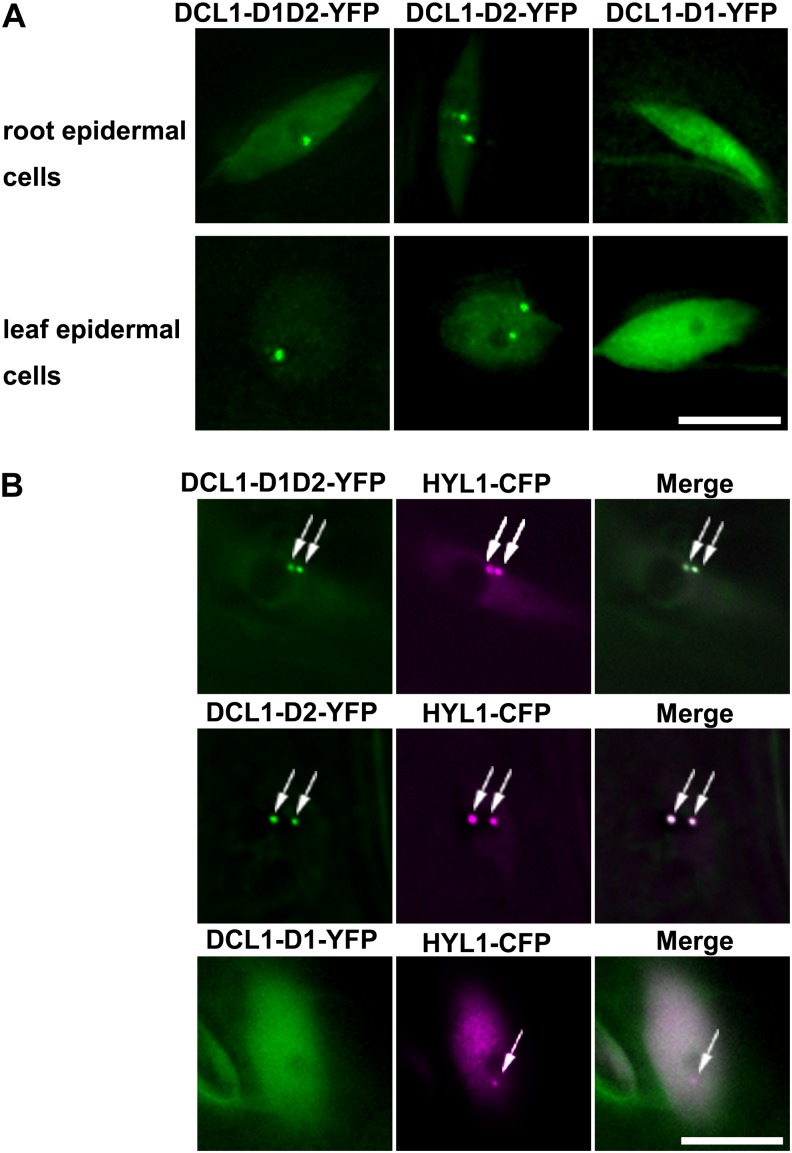

Figure 2.

The localization of different dsRBDs of DCL1 in living plant cells. A, Subcellular localization of DCL1-D1D2-YFP, DCL1-D2-YFP, and DCL1-D1-YFP. DCL1-D1D2-YFP and DCL1-D2-YFP localize in discrete nuclear foci, while DCL1-D1 shows diffused signals throughout the nucleoplasm. The root epidermal cells (top) and leaf epidermal cells (bottom) are shown. B, In transgenic plants coexpressing DCL1-D1-YFP/HYL1-CFP, DCL1-D2-YFP/HYL1-CFP, and DCL1-D1D2-YFP/HYL1-CFP, the nuclear bodies of DCL1-D1D2-YFP and DCL1-D2-YFP (green) fully colocalize with HYL1-CFP-containing d-bodies (magenta), while DCL1-D1-YFP shows no colocalization. Bars = 10 μm.

To clarify whether the nuclear bodies of DCL1-D2-YFP and DCL1-D1D2-YFP are d-bodies or not, we generated the transgenic plants coexpressing DCL1-D1D2-YFP/HYL1-cyan fluorescent protein (CFP), DCL1-D2-YFP/HYL1-CFP, and DCL1-D1-YFP/HYL1-CFP. As shown in Figure 2B, DCL1-D2-YFP- and DCL1-D1D2-YFP-containing bodies fully colocalized with HYL1-containing d-bodies, while DCL1-D1-YFP showed no overlap with d-bodies. Similar subnuclear patterns were observed in tobacco leaves transiently expressing DCL1-D1-YFP/HYL1-CFP, DCL1-D2-YFP/HYL1-CFP, and DCL1-D1D2-YFP/HYL1-CFP (Supplemental Fig. S4). In transgenic plants coexpressing DCL1-CFP/DCL1-D1-YFP, DCL1-CFP/DCL1-D2-YFP, or DCL1-CFP/DCL1-D1D2-YFP in the hyl1 mutant, DCL1-D2-YFP and DCL1-D1D2-YFP fully colocalized with DCL1-containing nuclear bodies, while DCL1-D1-YFP showed no overlap with d-bodies (Supplemental Fig. S5). These results indicated that dsRBDs of DCL1 contain a cryptic nuclear localization signal, and the second dsRBD of DCL1 is critical and sufficient for d-bodies targeting of DCL1 protein or the dsRBD. Similarly, we found that the first dsRBD of HYL1 or the two dsRBDs of HYL1 were enriched in d-bodies, while the second dsRBD showed a diffused signal in nucleus (Supplemental Fig. S6).

Differential Functions of dsRBDs of DCL1

The different efficiencies of hyl1 complementation and subnuclear localization patterns of DCL1-D1-YFP and DCL1-D2-YFP encouraged us to compare the functions between the first and second dsRBDs of DCL1. In addition to dsRNA binding, dsRBDs were found to have other functions, such as nuclear import and export, protein dimerization, and protein-protein interactions (Doyle and Jantsch, 2002; Tian et al., 2004). First, we tested the dsRNA-binding abilities of different dsRBDs of DCL1 by RNA electrophoresis mobility shift assay (R-EMSA). Purified glutathione S-transferase (GST)-tagged DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, and DCL1-D1D2 domains and in vitro transcribed biotin-labeled pri-miRNA167b were incubated and then PAGE electrophoresed. After being transferred to membranes, the binding signals were detected with anti-biotin antibody. As shown in Figure 3A, the shift bands indicated that pri-miRNA167b transcripts were bound by DCL1-D1 and DCL1-D1D2. By contrast, no binding was detected for DCL1-D2 at the sensitivity of R-EMSA.

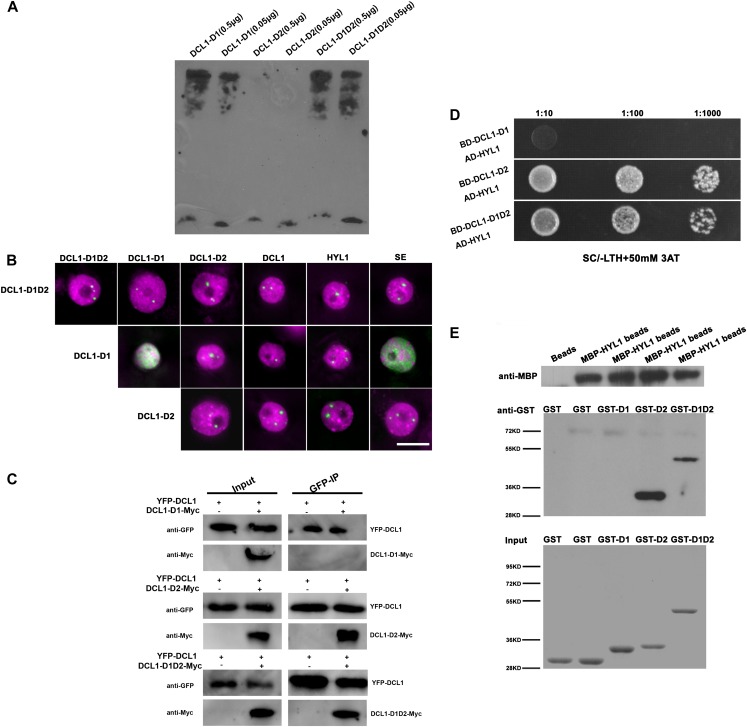

Figure 3.

Specific roles of different C-terminal dsRBDs in DCL1. A, R-EMSA. Purified GST-tagged DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, and DCL1-D1D2 proteins and in vitro transcribed biotin-labeled pri-miRNA167b were incubated. GST-tagged DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, and DCL1-D1D2 proteins (0.5 μg each) were added in the experiment with 2 nm biotin-labeled pri-miR167b. The signal bands indicated the RNA-protein complex. B, Pairwise BiFC experiments between different dsRBDs of DCL1, HYL1, SE, and DCL1 in d-bodies. BiFC signals between DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, DCL1-D1D2, HYL1, and SE were observed in d-bodies. DCL1-D2 and DCL1-D1D2 also interact with themselves in d-bodies. However, BiFC signals were observed in nucleoplasm or nuclear speckles for DCL1-D1/DCL1-D1 and DCL1-D1/SE pairs (green). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI in magenta. Bar = 10 μm. C, Coimmunoprecipitation assays indicated the interactions between DCL1-D2 and DCL1 and DCL1-D1D2 and DCL1 but not DCL1-D1 and DCL1. YFP-DCL1 and Myc-tagged DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, or DCL1-D1D2 were transiently coexpressed in tobacco (inputs), and then tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated using anti-GFP-agarose (GFP-IP). YFP-DCL1 was detected by anti-GFP antibody, and Myc-tagged proteins were detected by anti-Myc antibody. YFP-DCL1 without Myc-tagged proteins was expressed in tobacco and used as a negative control. D, Yeast two-hybrid assays indicated the interactions between DCL1-D2 and HYL1, DCL1-D1D2, and HYL1 but not DCL1-D1 and HYL1. Bait domains were fused with DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, and DCL1-D1D2, respectively, while activation domain was fused with HYL1. When cotransformed into yeast cells, the positive clones were selected from Synthetic Complete Medium/leucine and tryptophan dropped out plates, diluted by 1:10, 1:100, and 1:1,000, and dropped onto Synthetic Complete Medium/leucine, tryptophan and histidine dropped out + 50 mm 3-Aminotriazole plates. E, MBP pull-down assays indicated the interactions between DCL1-D2 and HYL1, DCL1-D1D2, and HYL1, but not DCL1-D1 and HYL1. After incubation of GST-tagged proteins with MBP-HYL1 beads, MBP-HYL1 was detected by anti-MBP antibody (top), and then GST-tagged proteins were detected by anti-GST antibody (middle). GST-tagged inputs were shown by Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining (bottom). MBP beads were incubated with GST protein as a negative control.

We then tested whether dsRBDs of DCL1 are involved in protein-protein interaction. First, we assayed bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) between DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, DCL1-D1D2, DCL1, HYL1, and SE. Protein pairs were fused to N-terminal or C-terminal fragments of YFP (YFPN or YFPC), respectively, and transiently expressed in tobacco leaves. BiFC signals between DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, DCL1-D1D2, DCL1, HYL1, and SE were observed in d-bodies. Both DCL1-D2 and DCL1-D1D2 also interacted with themselves in d-bodies. However, BiFC signals were observed throughout the nucleoplasm or nuclear speckles for DCL1-D1/DCL1-D1 and DCL1-D1/SE pairs (Fig. 3B).

To further verify these protein-protein interactions, we carried out coimmunoprecipitation experiments to test the interactions between full-length DCL1 and its dsRBDs. YFP-tagged DCL1 and Myc-tagged DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, or DCL1-D1D2 were coexpressed transiently, and then tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated using epitope-specific antibodies. DCL1 protein was detected to interact with DCL1-D2 and DCL1-D1D2 but not DCL1-D1, indicating that DCL1-D2 but not DCL1-D1 interacts with DCL1 and mediates the protein-protein interaction (Fig. 3C).

We then performed yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) two-hybrid assays to investigate the interactions between HYL1 and dsRBDs of DCL1. Yeast cells cotransformed by DCL1-D2 or DCL1-D1D2 baits and HYL1 prey fusion were able to grow on media with 3-amino-1,2,4-triazole at a high concentration (50 mm) and without His (Fig. 3D), but not DCL1-D1 bait and HYL1 prey fusion, suggesting that DCL1-D2 and DCL1-D1D2 mediate their interactions with HYL1, but not the DCL1-D1. Next, we carried out the maltose binding protein (MBP) pull-down assay to confirm the observed protein-protein interactions. The recombinant HYL1 protein fused with maltose-binding protein epitope at its N terminus (MBP-HYL1) was expressed in Escherichia coli and conjugated to amylase resin. Then the N-terminally GST-tagged DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, and DCL1-D1D2 were expressed in E. coli and purified. Following the incubation of these GST-tagged proteins with MBP-HYL1 beads, GST-DCL1-D2 and GST-DCL1-D1D2 were pulled down by MBP-HYL1 and detected by an anti-GST antibody, while GST-DCL1-D1 was not pulled down (Fig. 3E). These results indicated that the interaction between DCL1 and HYL1 is mainly mediated by DCL1-D2.

DISCUSSION

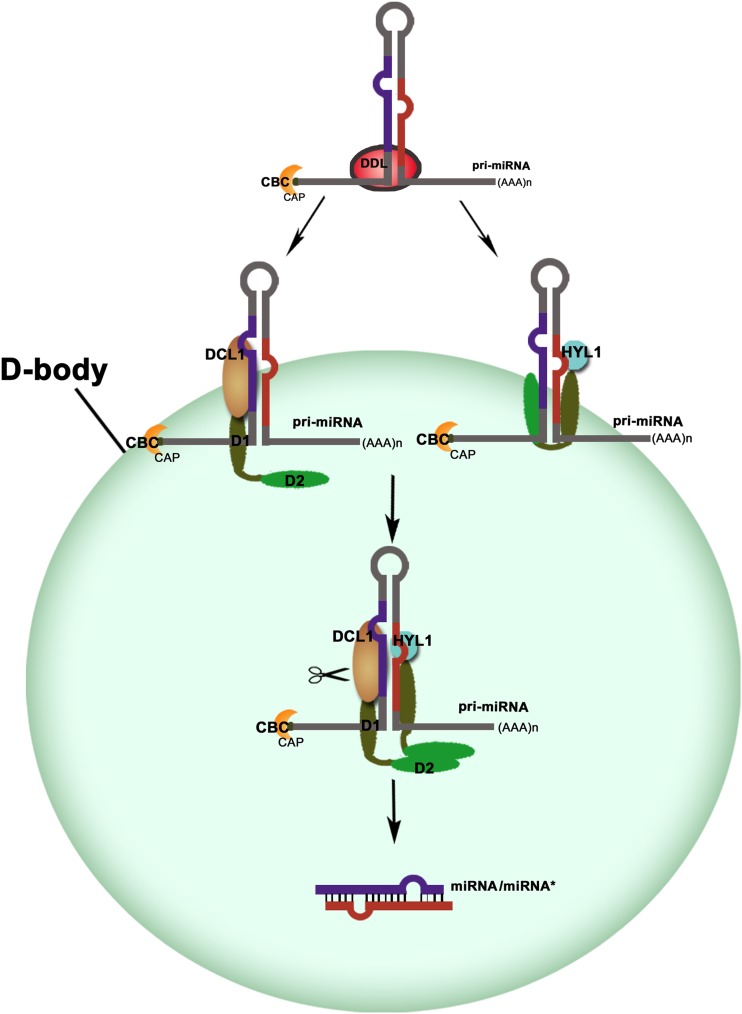

DCL1, an RNaseIII-like nuclease, plays a central role in plant pri-miRNA cleavages. Biochemical analysis revealed that the purified DCL1 was able to process pri-miRNAs into miRNAs in vitro (Kurihara and Watanabe, 2004; Dong et al., 2008). Both the efficiency and accuracy of processing are enhanced by adding the proteins of HYL1 and SE (Dong et al., 2008). HYL1 interacts with DCL1 and enhances the precision of miRNA processing in vivo (Han et al., 2004b; Kurihara et al., 2006). Both dsRBDs of HYL1 could bind the pri-miRNAs, whereas the second dsRBD mediated the interaction with the dsRBDs of DCL1 (Supplemental Fig. S6), consistent with pervious reports (Hiraguri et al., 2005; Rasia et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2010). We have found that the two dsRBDs of DCL1 can complement phenotypes of hyl1, and the dsRNA binding of DCL1 is mainly mediated by DCL1-D1, which cannot complement the hyl1 phenotype, while protein-protein interaction is mediated by DCL1-D2, which partially complements hyl1. Previously, a pri-miRNA was found to enter into d-bodies in vivo (Fang and Spector, 2007). Taken together, we propose a model in which Arabidopsis pri-miRNAs are recruited to d-bodies by functionally divergent dsRBDs of DCL1 for accurate processing. As shown in Figure 4, the RNA-binding protein DAWDLE presumably stabilizes pri-miRNAs and facilitates DCL1 to access or recognize pri-miRNAs (Yu et al., 2008). DCL1-D1 functions in dsRNA binding, while DCL1-D2 guides DCL1 and its associated pri-miRNA to d-bodies through protein-protein interaction. HYL1 also binds the pri-miRNAs and is targeted to d-bodies through interaction with DCL1. When HYL1 interacts with DCL1, the pri-miRNA molecule was anchored in place for precise dicing mediated by DCL1, ensuring the accuracy of miRNA biogenesis.

Figure 4.

A model for the recruitment of pri-miRNAs to d-bodies through functionally divergent dsRBDs of DCL1. MiRNA genes are transcribed by RNA polymerase II to generate pri-miRNAs. DCL1-D1 plays a role in pri-miRNA binding. In contrast, DCL1-D2 is involved in protein-protein interaction, thus guides DCL1 and its bound pri-miRNA to the d-bodies. The two N-terminal dsRBDs of HYL1 play similar roles to dsRBDs of DCL1. When the four DsRBDs bind together, they anchor the pri-miRNA molecule in place, and thus guarantee the accuracy of the dicing reaction of DCL1.

DCL1-D1D2 has both the dsRNA binding and protein-protein interacting activities, thus fully substitute the functions of HYL1. However, DCL1-D1 can only bind pri-miRNAs, but cannot enter into d-bodies through protein-protein interaction, and thus fails to complement hyl1 phenotypes. By contrast, DCL1-D2 is not a canonical dsRBD, which may leave nucleic acid binding as a vestigial feature during evolution (Burdisso et al., 2012). DCL1-D2 may bind weakly with pri-miRNAs at a sensitivity below R-EMSA (Fig. 3A) but might enter into d-bodies through dimerization as DCL1-D2 interacts with itself (Fig. 3B), resulting in partial complementation of hyl1.

The variant proteins of DCL1 affecting either the helicase or the RNaseIII domains of DCL1 could enhance efficiency for pri-miRNA processing, but the precision of miRNA processing defects are retained (Liu et al., 2012), implicating that the domains of DCL1 apart from dsRBDs are important for the dicing activity, while dsRBDs are critical for the accuracy of dicing. In the hyl1 mutant, the dsRBDs in full-length DCL1 protein might not interact with each other effectively because of the protein folding and compromises by the other domains. Consequently, only a minority of T1 plants overexpressing DCL1 was observed to complement the hyl1 phenotypes (Liu et al., 2012). We reasoned that the recovery of the hyl1 mutant by full-length DCL1 mainly relies on the overexpressed dsRBDs of DCL1, which are compromised by other domains in this big protein. By contrast, a mutation in ATPase/DExH-box RNA helicase domain of DCL1 (DCL1-13) probably promotes the binding of DCL1-D1 to pri-miRNAs or the interaction between two DCL1 molecules through their DCL1-D2 domains and thus increases the accuracy of DCL1-mediated cleavage of these pri-miRNAs in absence of its partner protein HYL1, resulting in the suppression of the hyl1 mutant phenotype (Tagami et al., 2009).

To test whether other dsRBDs could complement the hyl1-2 phenotypes, we transformed the two dsRBDs of DCL3 (DCL3-D1D2) and DCL4 (DCL4-D1D2) into the hyl1 mutant but didn’t find any recovery (Supplemental Fig. S7), indicating that complementation of hyl1 by dsRBDs of DCL1 is specific. This might be due to the fact that DCL1 and HYL1 participated in the miRNA processing, while DCL3 and DCL4 are involved in small interfering RNA biogenesis (Bouché et al., 2006; Kurihara et al., 2006; Kotakis et al., 2011). Interestingly, the observed complementation of the hyl1 phenotype correlates with the localization of introduced dsRBDs to d-bodies. DCL1-D1D2-YFP localizes in d-bodies and complements hyl1. In DCL1-D2-YFP/hyl1 plants, we compared the localization patterns of DCL1-D2-YFP between recovered DCL1-D2-YFP/hyl1 and unrecovered DCL1-D2-YFP/hyl1 plants and found that DCL1-D2-YFP in recovered lines localized in d-bodies, while DCL1-D2-YFP in all unrecovered lines fail to localize to d-bodies (Supplemental Fig. S2). Similarly, we found that the two N-terminal dsRBDs of HYL1 also localize in d-bodies (Supplemental Fig. S6B), while DCL3-D1D2-YFP and DCL4-D1D2-YFP diffusely distributed in the nucleoplasm in addition to their localizations in cytoplasm (Supplemental Fig. S7A). These results further revealed the important role of d-bodies in miRNA processing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials, Growth Conditions, and Phenotype Evaluation

Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana ecotype Columbia [Col-0]), dcl1-9 (Jacobsen et al., 1999), and hyl1 (hyl1-2, Salk_064863) mutants were used. Arabidopsis was grown under 16-h-light/8-h-dark conditions at 23°C in a growth chamber. For quantifying the differences of phenotypes among the wild type, hyl1, and transgenic lines, the TC index was measured as described (Wu et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2010).

Constructs and Plant Transformation

Complementary DNA (cDNA) fragments of DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, and DCL1-D1D2 were amplified from plasmid pC131-35S-YFP-DCL1 (primer pairs: 5′-NNNGGATCCATGCATCCGGTGCGAGAGCTA-3′ and 5′-NNNGTCGACTATTTCTTTCTCTTTCAAAG-3′; 5′-NNNGGATCCCCGTTTACGAGACAAACG-3′ and 5′-NNNACTAGTAGAAAAAGTTTTATTTAAAAG-3′; and 5′-NNNGGATCCATGCATCCGGTGCGAGAGCTA-3′ and 5′-NNNACTAGTAGAAAAAGTTTTATTTAAAAG-3′), digested by BamHI/SpeI, and subcloned into BamHI/SpeI-treated vector pC131-35S-N1-YFP, pC131-35S-N1-CFP, pC131-35S-N1-YFPN, or pC131-35S-N1-YFPC. The cDNA fragments of HYL1-D1, HYL1-D2, and HYL1-D1D2 were amplified by PCR from Col-0 cDNA (primers: 5′-CAAGAATTCATGACCTCCACTGATGTTTC-3′ and 5′-AAGTCGACGGATTTTGCTAATTCCCGGA-3′; 5′-CAAGAATTCATGGAAACGGGATTATGCAAG-3′ and 5′-AAGTCGACGTCTGACTGGATCGCTAAAG-3′; and 5′-CAAGAATTCATGACCTCCACTGATGTTTC-3′ and 5′-AAGTCGACGTCTGACTGGATCGCTAAAG-3′) and subcloned into EcoRI/SalI-treated vector pC131-35S-N1-YFP. The cDNA fragments of DCL3-D1D2 and DCL4-D1D2 were amplified from pC131-35S-YFP-DCL3 and pC131-35S-YFP-DCL4, respectively (primers for DCL3-D1D2: 5′-NNNGGATCCATGCTTCCTCCATACCGGGAGCT-3′ and 5′-NNNACTAGTGATCTTGCGGCGCTCGAG-3′ and primers for DCL4-D1D2: 5′-NNNGAATTCATGATTAGTCCTATAAAAGAACTGATTG-3′ and 5′-NNNGTCGACTCCAGAATGCTTGAGGCACCAT-3′), and subcloned into pC131-35S-N1-YFP. All the fusion vectors were confirmed by sequencing. pC131-pHYL1-HYL1-CFP, pC131-35S-CFP-DCL1, pC131-35S-YFP-DCL3, pC131-35S-YFP-DCL4, pC131-pHYL1-HYL1-YFPN, pC131-pHYL1-HYL1-YFPC, pC131-35S-DCL1-YFPN, pC131-35S-DCL1-YFPC, pC131-35S-YFPN-SE, and pC131-35S-YFPC-SE vectors existed in our laboratory(Fang and Spector, 2007).The constructs described above were introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101 by electroporation.

Arabidopsis plants were transformed by the floral dip method (Clough and Bent, 1998). Heterozygous dcl1-9 seeds were germinated in Murashige and Skoog medium containing 50 mg L–1 kanamycin, transferred to soil, and transformed by GV3101(35S::DCL1-D1-YFP, 35S::DCL1-D2-YFP, and 35S::DCL1-D1D2-YFP). Homozygous HYL1 mutant plants were also transformed with GV3101 (35S::DCL1-D1-YFP, 35S::DCL1-D2-YFP, and 35S::DCL1-D1D2-YFP). Independent T1 transgenic lines were selected on Murashige and Skoog medium containing 50 mg L–1 hygromycin and 50 mg L–1 kanamycin. Transgenic plants in dcl1-9 or hyl1 homozygous background were identified based on YFP signals under microscopy and the absence of amplification of the DCL1 gene (primers: 5′-CCTTCCTCCTGGTCGGTTA-3′ and 5′-ACAACCACTATGGTTTTAAGGT-3′) or the HYL1 gene (primers: 5′-ATGACCTCCACTGATGTTTC-3′ and 5′-GTCTGACTGGATCGCTAAAG-3′). For cotransformation, agrobacteria suspensions were mixed equally before dipping. Transformants were selected by relevant antibiotic markers and confirmed under fluorescent microscopy.

Transient Expression and BiFC

Transient expression was carried out according to the protocol (Fang and Spector, 2010). For BiFC experiments, coinfiltration was performed by agrobacteria harboring vectors (YFPN and YFPC; Fang and Spector, 2007). For labeling nuclei, agrobacteria-infiltrated areas of tobacco (Nicotiana benthamiana) were stained with 4′,6-diamino-phenylindole (DAPI) at 1.0 μg mL–1 (in water) for 10 min after fixation by 4% (w/v) paraformaldehyde.

Small RNA Northern Blot

Total RNA was extracted using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) from seedlings of 2-week-old wild-type plants, hyl1 mutants, and transgenic plants. The total RNA (approximately 20 µg) was separated by denaturing 19% (w/v) PAGE and transferred to a nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia). The 3′ biotin-labeled oligonucleotides (21 bp) complementary to miR156, miR160, miR166, miR171, and miR319 were synthesized as probes. Hybridization was performed using hybridization buffer (Ambion), and the signals were detected by chemiluminescent nucleic acid detection module (Thermo Scientific). U6 was used as a loading control. The probes used were listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR

Total RNA for reverse transcription-PCR analysis was prepared using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’s instructions from seedlings of 2-week-old wild-type, hyl1, and transgenic plants. Quantification of RNA was performed using a NanoDrop 2000c spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Total RNA was treated with RNase-Free DNaseI (Takara) to remove DNA, and the reverse transcription reaction was carried out by M-MLV First Strand Kit (Invitrogen). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed with Bio-Rad CFX Real-Time System. ACTIN2 mRNA was detected in parallel and used for data normalization. The data obtained were analyzed through a Bio-Rad iCycler iQ Real-Time Detection System. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

Coimmunoprecipitation Assay

Tobacco leaves were coinfiltrated with A. tumefaciens (GV3101) cells harboring DCL1-YFP and DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, or DCL1-D1D2 with Myc tags. Forty-eight hours after agroinfiltration, leaves were ground in liquid nitrogen and total proteins were extracted with three volumes of extraction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 10% [v/v] glycerol, 0.1% [v/v] Nonidet P-40, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing one protease inhibitor cocktail tablet per 50 mL (Roche). Anti-GFP-agarose (MBL) was used for capturing protein complexes associated with DCL1-YFP. The protein samples were resolved by SDS/PAGE and detected by anti-GFP (Sigma) and anti-Myc (Abgent) polyclonal antibodies, respectively.

Yeast Two Hybrid

The cDNA encoding the DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, DCL1-D1D2, HYL1-D1, HYL1-D2, HYL1-D1D2, and the entire HYL1 were amplified and cloned into pENTR/SD/D-TOPO plasmid using the Gateway system (Invitrogen). The fragments in pENTR/SD/D-TOPO vectors were recombined into two-hybrid bait vector pDEST32 or prey vector pDEST22, respectively. Yeast two-hybrid assays were performed using the ProQuest Two-Hybrid System (Invitrogen). The primers are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

MBP Pull-Down Assay

GST-DCL1-D1, GST-DCL1-D2, GST-DCL1-D1D2, or GST alone were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). Cells were harvested, resuspended in buffer phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.3), and lysed by sonication. The GST-tagged recombinant proteins were purified by Glutathione Sepharose (GE Healthcare). MBP-HYL1 or MBP alone were expressed in BL21 (DE3). Lysate was incubated with amylase resin for conjunction (New England Biolabs). The MBP-HYL1 resin or MBP resin (30 uL) was preincubated in 1 mL blocking buffer (5% [w/v] bovine serum albumin and 0.5% [v/v] Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 h at 4°C and resuspended in 1 mL binding buffer (0.5% [w/v] bovine serum albumin and 0.05% [v/v] Triton-X100 in PBS). Equal amount (approximately 2 µg) of GST, GST-DCL1-D1, GST-DCL1-D2, or GST-DCL1-D1D2 was added, and mixture was incubated at 4°C overnight. The precipitates were washed five times with PBS and resolved by 10% (w/v) SDS/PAGE. Anti-GST (GenScript) and anti-MBP (New England Biolabs) polyclonal antibodies were used to detect GST-tagged proteins and MBP-HYL1, respectively. GST, GST-DCL1-D1, GST-DCL1-D2, and GST-DCL1-D1D2 proteins (approximately 2 µg) were loaded on a 10% (w/v) SDS/PAGE gel and stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue for inputs.

Using the same method described above, GST-HYL1-D1, GST-HYL1-D2, GST-HYL1-D1D2, or GST was purified and incubated with MBP-DCL1-D1D2 beads. Anti-MBP (New England Biolabs) polyclonal antibodies were used to detect the existence of MBP-DCL1-D1D2 protein, while anti-GST (GenScript) was used to detect whether GST-tagged proteins were pulled down. GST, GST-HYL1-D1, GST-HYL1-D2, and GST-HYL1-D1D2 proteins (approximately 2 µg) were loaded on a 10% (w/v) SDS/PAGE gel and stained by Coomassie Brilliant Blue for inputs. The primers used are listed in Supplemental Table S2.

R-EMSA

The in vitro RNA-binding activity was assayed by electrophoresis mobility shift assay experiments. Pri-miR167b fragments were amplified from Col-0 cDNAs (primers: 5′-ATTTCTCCACTTCTTGAGCTTCC-3′ and 5′-AGTCAACTGTGTGCGTTCGGGACT-3′) ligated to vector pGEM-T (Promega) containing a T7 promoter sequence. The plasmid DNA was linearized with SpeI digestion and used as templates for in vitro RNA transcription (Ambion). Then, the transcripts were purified and 3′ biotinylated (Thermo Scientific). The pri-miRNA transcripts were denatured at 95°C for 5 min and then slowly cooled to room temperature for renature. Using RNA EMSA Kit (Thermo Scientific), electrophoresis mobility shift assay experiments were performed in a 20-μL binding reaction system containing binding buffer, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 2 µg tRNA, 2 nm of labeled pri-miR67b transcripts, and purified GST-tagged DCL1-D1, DCL1-D2, and DCL1-D1D2 (for each, 0.05 and 0.5 µg proteins were used) according to instruction of the manufacturer. For the dsRBDs of HYL1, a 20-μL reaction mixture containing binding buffer, 5% (v/v) glycerol, 2 µg tRNA, and 2 nm of labeled pri-miR167b transcripts and purified recombinant HYL1-D1, HYL1-D2, and HYL1-D1D2 (0.5 µg) were used. In the competition experiments of HYL1-D1, HYL1-D2, and HYL1-D1D2, 100 folds of unlabeled pri-miRNA were also added in the reaction mixtures. The reaction mixtures were incubated for 30 min, electrophoresed on a 6.5% (w/v) native polyacrylamide gel in 0.5× Tris-borate/EDTA for about 40 min, and transferred to a nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia). The signal bands were detected by a chemiluminescent nucleic acid detection module (Thermo Scientific).

In Vitro miRNA Processing Assay

Plants were ground in liquid nitrogen and resolved in the extraction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl at pH 7.6, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 10% [v/v] glycerol, 0.1% [v/v] Nonidet P-40, 0.5 mm dithiothreitol, and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) containing one protease inhibitor cocktail tablet per 50 mL (Roche). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation for 30 min at 13,000 rpm at 4°C. Protein extracts were precleared by incubation with 20 μL of protein A/G-agarose at 4°C for 1 h and then immunoprecipitated by anti-GFP-agarose.

The pri-miR171a cDNA fragment was amplified, ligated to vector pGEM-T (Promega) containing a T7 promoter sequence, and used as a template for in vitro RNA transcription (Ambion). The pri-miRNA transcripts were purified, denatured at 95°C for 5 min, and then slowly cooled to room temperature for renature. Dicing process was carried out as described (Qi et al., 2005; Wu et al., 2007). Briefly, pri-miRNA (approximately 10 μg) transcripts were incubated in a 20-μL reaction buffer containing 10 μL immunoprecipitate and 4 μL 5× reaction buffer (0.5 m NaCl, 5 mm ATP, 1 mm GTP, 6 mm MgCl, 125 mm creatine phosphate, 150 μg mL–1 creatine kinase, and 2 units RNAsin RNase Inhibitor) at 25°C for 2 h. The RNAs were extracted, precipitated, and resolved on 15% (w/v) denaturing PAGE gels. Small RNA northern blot was performed using a 3′ biotin-labeled miR171 probe.

Microscopy

Image stacks of nuclei were acquired at room temperature with a DeltaVision Personal DV system (Applied Precision) consisting of an IX70 inverted microscope (Olympus) equipped with an UPLANAPO water immersion objective lens (60×/1.20 numerical aperture; Olympus) and a Photometrics CoolSnap ES2 camera (Roper Scientific) with Applied Precision customizations and drivers (Fang and Spector, 2010). Filters used for DAPI were exciter (360 nm/40 nm) and emitter (457 nm/50 nm); filters used for CFP were exciter (430 nm/24 nm) and emitter (470 nm/24 nm); filters used for YFP were exciter (492 nm/18 nm) and emitter (535 nm/30 nm); and filters used for mCherry were exciter (572 nm/35 nm), emitter (632 nm/60 nm), and a polychroic beam splitter (Chroma Technology). Data collection and processing were performed as previously described (Fang and Spector, 2007; Shi et al., 2011).

Supplemental Data

The following materials are available in the online version of this article.

Supplemental Figure S1. Domain structures of dsRBDs and alignment of dsRBDs in dsRBDs from humans and Arabidopsis.

Supplemental Figure S2. The localizations of DCL1-D2-YFP, phenotypes, and miRNA levels in DCL1-D2-YFP/hyl1 recovered and unrecovered lines.

Supplemental Figure S3. In vitro pri-miRNA processing by protein complexes containing HYL1-YFP, DCL1-D1D2-YFP, DCL1-D2-YFP, or DCL1-D1-YFP.

Supplemental Figure S4. Subcellular localization of DCL1-D1D2-YFP, DCL1-D2-YFP, and DCL1-D1-YFP coinfiltrated with HYL1-CFP in tobacco leaf epidermal cells.

Supplemental Figure S5. Subcellular localization of DCL1-D1D2-YFP, DCL1-D2-YFP, and DCL1-D1-YFP in transgenic plants coexpressing DCL1-D1D2-YFP/DCL1-CFP, DCL1-D2-YFP/DCL1-CFP, and DCL1-D1-YFP/DCL1-CFP.

Supplemental Figure S6. Subcellular localization patterns and functions of different dsRBDs of HYL1.

Supplemental Figure S7. Subcellular localization of DCL3-D1D2-YFP and DCL4-D1D2-YFP and visual phenotypes of DCL3-D1D2-YFP/hyl1 and DCL4-D1D2-YFP/hyl1 seedlings.

Supplemental Table S1. Phenotypic complementation ratio of hyl1-2 and dcl1-9 mutants by different dsRBDs of DCL1 in T1 generation plants.

Supplemental Table S2. Oligos used in this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of Yuda Fang’s lab for insightful discussions.

Glossary

- miRNA

microRNA

- pri-miRNA

primary microRNA

- dsRBD

double-strand RNA-binding domain

- dsRNA

double-strand RNA

- dsRBP

double-strand RNA-binding protein

- d

dicing

- TC

transverse curvature

- R-EMSA

RNA electrophoresis mobility shift assay

- BiFC

bimolecular fluorescence complementation

- Col-0

ecotype Columbia

- cDNA

complementary DNA

- DAPI

4,6-diamino-phenylindole

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

References

- Bouché N, Lauressergues D, Gasciolli V, Vaucheret H. (2006) An antagonistic function for Arabidopsis DCL2 in development and a new function for DCL4 in generating viral siRNAs. EMBO J 25: 3347–3356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burdisso P, Suarez IP, Bologna NG, Palatnik JF, Bersch B, Rasia RM. (2012) Second double-stranded RNA binding domain of dicer-like ribonuclease 1: structural and biochemical characterization. Biochemistry 51: 10159–10166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington JC, Ambros V. (2003) Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science 301: 336–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chendrimada TP, Gregory RI, Kumaraswamy E, Norman J, Cooch N, Nishikura K, Shiekhattar R. (2005) TRBP recruits the Dicer complex to Ago2 for microRNA processing and gene silencing. Nature 436: 740–744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. (1998) Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J 16: 735–743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curtin SJ, Watson JM, Smith NA, Eamens AL, Blanchard CL, Waterhouse PM. (2008) The roles of plant dsRNA-binding proteins in RNAi-like pathways. FEBS Lett 582: 2753–2760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Han MH, Fedoroff N. (2008) The RNA-binding proteins HYL1 and SE promote accurate in vitro processing of pri-miRNA by DCL1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 9970–9975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle M, Jantsch MF. (2002) New and old roles of the double-stranded RNA-binding domain. J Struct Biol 140: 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Spector DL. (2007) Identification of nuclear dicing bodies containing proteins for microRNA biogenesis in living Arabidopsis plants. Curr Biol 17: 818–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Y, Spector DL (2010) Live cell imaging of plants. Cold Spring Harb Protoc 2:pdb top68. 10.1101/pdb.top68 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fukudome A, Kanaya A, Egami M, Nakazawa Y, Hiraguri A, Moriyama H, Fukuhara T. (2011) Specific requirement of DRB4, a dsRNA-binding protein, for the in vitro dsRNA-cleaving activity of Arabidopsis Dicer-like 4. RNA 17: 750–760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN. (2004a) The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev 18: 3016–3027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MH, Goud S, Song L, Fedoroff N. (2004b) The Arabidopsis double-stranded RNA-binding protein HYL1 plays a role in microRNA-mediated gene regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 1093–1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiraguri A, Itoh R, Kondo N, Nomura Y, Aizawa D, Murai Y, Koiwa H, Seki M, Shinozaki K, Fukuhara T. (2005) Specific interactions between Dicer-like proteins and HYL1/DRB-family dsRNA-binding proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol Biol 57: 173–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen SE, Running MP, Meyerowitz EM. (1999) Disruption of an RNA helicase/RNAse III gene in Arabidopsis causes unregulated cell division in floral meristems. Development 126: 5231–5243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotakis C, Vrettos N, Daskalaki MG, Kotzabasis K, Kalantidis K. (2011) DCL3 and DCL4 are likely involved in the light intensity-RNA silencing cross talk in Nicotiana benthamiana. Plant Signal Behav 6: 1180–1182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara Y, Takashi Y, Watanabe Y. (2006) The interaction between DCL1 and HYL1 is important for efficient and precise processing of pri-miRNA in plant microRNA biogenesis. RNA 12: 206–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurihara Y, Watanabe Y. (2004) Arabidopsis micro-RNA biogenesis through Dicer-like 1 protein functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 12753–12758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landthaler M, Yalcin A, Tuschl T. (2004) The human DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 and its D. melanogaster homolog are required for miRNA biogenesis. Curr Biol 14: 2162–2167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laubinger S, Sachsenberg T, Zeller G, Busch W, Lohmann JU, Rätsch G, Weigel D. (2008) Dual roles of the nuclear cap-binding complex and SERRATE in pre-mRNA splicing and microRNA processing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 8795–8800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C, Axtell MJ, Fedoroff NV. (2012) The helicase and RNaseIIIa domains of Arabidopsis Dicer-Like1 modulate catalytic parameters during microRNA biogenesis. Plant Physiol 159: 748–758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Jia L, Mao Y, He Y. (2010) Classification and quantification of leaf curvature. J Exp Bot 61: 2757–2767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu C, Fedoroff N. (2000) A mutation in the Arabidopsis HYL1 gene encoding a dsRNA binding protein affects responses to abscisic acid, auxin, and cytokinin. Plant Cell 12: 2351–2366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E, Güttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE, Kutay U. (2004) Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science 303: 95–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manavella PA, Hagmann J, Ott F, Laubinger S, Franz M, Macek B, Weigel D. (2012) Fast-forward genetics identifies plant CPL phosphatases as regulators of miRNA processing factor HYL1. Cell 151: 859–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molnár A, Schwach F, Studholme DJ, Thuenemann EC, Baulcombe DC. (2007) miRNAs control gene expression in the single-cell alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Nature 447: 1126–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montgomery TA, Carrington JC. (2008) Splicing and dicing with a SERRATEd edge. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 8489–8490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakazawa Y, Hiraguri A, Moriyama H, Fukuhara T. (2007) The dsRNA-binding protein DRB4 interacts with the Dicer-like protein DCL4 in vivo and functions in the trans-acting siRNA pathway. Plant Mol Biol 63: 777–785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y, Denli AM, Hannon GJ. (2005) Biochemical specialization within Arabidopsis RNA silencing pathways. Mol Cell 19: 421–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasia RM, Mateos J, Bologna NG, Burdisso P, Imbert L, Palatnik JF, Boisbouvier J. (2010) Structure and RNA interactions of the plant microRNA processing-associated protein HYL1. Biochemistry 49: 8237–8239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart BJ, Slack FJ, Basson M, Pasquinelli AE, Bettinger JC, Rougvie AE, Horvitz HR, Ruvkun G. (2000) The 21-nucleotide let-7 RNA regulates developmental timing in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature 403: 901–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren G, Xie M, Dou Y, Zhang S, Zhang C, Yu B. (2012) Regulation of miRNA abundance by RNA binding protein TOUGH in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 12817–12821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauer SE, Jacobsen SE, Meinke DW, Ray A. (2002) DICER-LIKE1: blind men and elephants in Arabidopsis development. Trends Plant Sci 7: 487–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L, Wang J, Hong F, Spector DL, Fang Y. (2011) Four amino acids guide the assembly or disassembly of Arabidopsis histone H3.3-containing nucleosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 10574–10578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song L, Han MH, Lesicka J, Fedoroff N. (2007) Arabidopsis primary microRNA processing proteins HYL1 and DCL1 define a nuclear body distinct from the Cajal body. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104: 5437–5442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagami Y, Motose H, Watanabe Y. (2009) A dominant mutation in DCL1 suppresses the hyl1 mutant phenotype by promoting the processing of miRNA. RNA 15: 450–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian B, Bevilacqua PC, Diegelman-Parente A, Mathews MB. (2004) The double-stranded-RNA-binding motif: interference and much more. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 1013–1023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vazquez F, Gasciolli V, Crété P, Vaucheret H. (2004) The nuclear dsRNA binding protein HYL1 is required for microRNA accumulation and plant development, but not posttranscriptional transgene silencing. Curr Biol 14: 346–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Song X, Gu L, Li X, Cao S, Chu C, Cui X, Chen X, Cao X. (2013) NOT2 proteins promote polymerase II-dependent transcription and interact with multiple MicroRNA biogenesis factors in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 25: 715–727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Yu L, Cao W, Mao Y, Liu Z, He Y. (2007) The N-terminal double-stranded RNA binding domains of Arabidopsis HYPONASTIC LEAVES1 are sufficient for pre-microRNA processing. Plant Cell 19: 914–925 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Shi Y, Li J, Xu L, Fang Y, Li X, Qi Y. (2013) A role for the RNA-binding protein MOS2 in microRNA maturation in Arabidopsis. Cell Res 23: 645–657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Liu Z, Lu F, Dong A, Huang H. (2006) SERRATE is a novel nuclear regulator in primary microRNA processing in Arabidopsis. Plant J 47: 841–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SW, Chen HY, Yang J, Machida S, Chua NH, Yuan YA. (2010) Structure of Arabidopsis HYPONASTIC LEAVES1 and its molecular implications for miRNA processing. Structure 18: 594–605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. (2003) Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev 17: 3011–3016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B, Bi L, Zheng B, Ji L, Chevalier D, Agarwal M, Ramachandran V, Li W, Lagrange T, Walker JC, et al. (2008) The FHA domain proteins DAWDLE in Arabidopsis and SNIP1 in humans act in small RNA biogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 10073–10078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Y, Yi R, Cullen BR. (2005) Recognition and cleavage of primary microRNA precursors by the nuclear processing enzyme Drosha. EMBO J 24: 138–148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]