Abstract

Protein kinases are essential enzymes for cellular signalling, and are often regulated by participation in protein complexes. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) p38 is involved in multiple pathways, and its regulation depends on its interactions with other signalling proteins. However, the identification of p38 interacting proteins is challenging. For this reason, we have developed label transfer reagents (LTRs) which allow labelling of p38 signalling complexes. These LTRs leverage the potency and selectivity of known p38 inhibitors to place a photo-crosslinker and tag in the vicinity of p38 and its binding partners. Upon UV irradiation, proteins that are in close proximity to p38 are covalently crosslinked, and labelled proteins are detected and/or purified through an orthogonal chemical handle. Here we demonstrate that p38-selective LTRs selectively label a diversity of p38 binding partners, including substrates, activators, and inactivators. Furthermore, these LTRs can be used in immunoprecipitations to provide low-resolution structural information on p38-containing complexes.

Keywords: protein-protein interactions, signal transduction, p38 MAPK, crosslinking, chemical biology

Introduction

Protein phosphorylation is a post-translational modification that is essential for intracellular signaling in all eukaryotic organisms. Indeed, the human genome encodes over 500 different protein kinases.[1] Consequently, the regulation of these kinases is both important and complex. One key way that kinases are regulated is by their sequestration in signaling complexes. These complexes can bring together activators or substrates of kinases, permitting rapid and complex-specific transmission of a cellular signal.[2, 3]

p38α (hereafter referred to as p38) is a MAPK involved in cellular responses to inflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and stresses such as osmotic shock and DNA damage.[4] These signals trigger the activation of MKK6 and/or MKK3, which activate p38 by dual activation loop phosphorylation. In addition, p38 can be activated by MAPKK-independent pathways, such as TAB1-induced autophosphorylation of p38 in response to some extracellular signals.[5, 6] The substrates of p38 are varied, including downstream kinases, enzymes, and transcription factors. Importantly, while diverse stimuli activate p38, the substrates that are phosphorylated by p38 vary with the specific stimulus.[6, 7] Thus, there exists a means of correlating the activation of p38 with the substrates it phosphorylates. This specificity may be accomplished, in part, by the activity of other signaling molecules triggered by that stimulus. It is also likely that a significant component of this regulation is through sequestering p38 into stimulus-specific complexes. Therefore, the complement of proteins bound to p38 will vary by subcellular localization and by cellular conditions. Surprisingly, few p38 complexes have been described.[8] It is likely that this lack of knowledge is due to the weak and transient nature of these complexes.

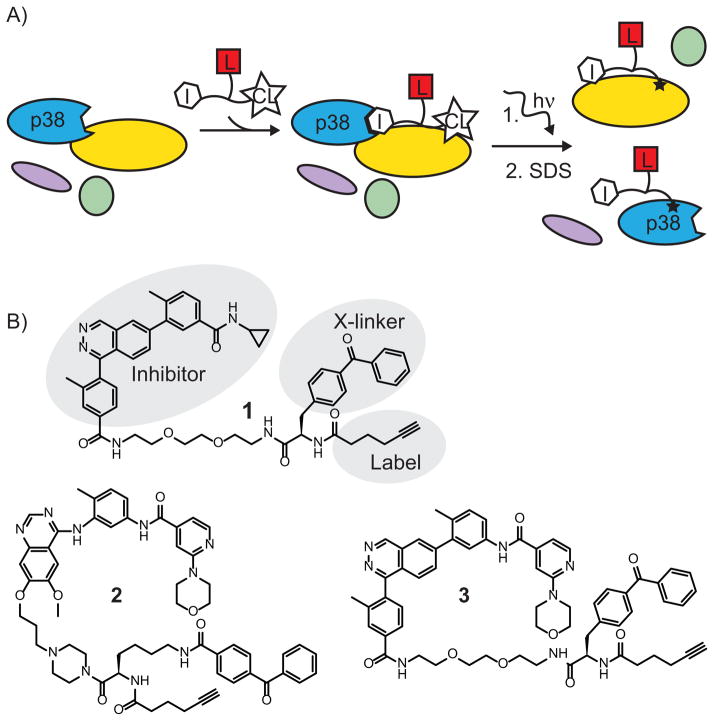

Here, we describe a new method to study protein kinase signaling complexes that enables us to detect p38-interacting proteins. This method relies on the use of highly selective ATP-competitive inhibitors to position a photo-crosslinker and tag in the vicinity of protein complexes that contain p38 (Figure 1). These label transfer reagents (LTRs) contain three modular components (Figure 1A): (1) an ATP-competitive kinase inhibitor that targets the labeling reagent to a kinase target of interest; (2) a photo-crosslinker, which allows covalent labeling of any proteins that are in proximity to the LTR; and (3) an orthogonal chemical alkyne tag for visualization and/or purification of proteins that have been labeled. When the LTR is introduced into a sample containing p38, the ATP-competitive inhibitor will direct the photo-crosslinker to the vicinity of p38 and the proteins with which it is complexed. Upon ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, the LTR covalently labels proteins in a p38 complex. The use of a selective p38 inhibitor allows LTRs to be used in complex protein mixtures, and the covalent nature of the labeling reaction enables detection of weak and transient interactions.

Figure 1.

Label transfer reagents (LTRs) for the identification of the interacting partners of protein kinases. A) Overview of the LTR strategy. An ATP-competitive p38 inhibitor (I) directs the LTR to the active site of p38, placing a photo-crosslinker (CL) in the vicinity of p38 and proteins that interact with p38. UV irradiation covalently labels proteins in p38 signaling complexes with a label (L) that can be used for detection and/or purification. B) Structures of LTRs 1–3 that were generated and used in this study.

Results and Discussion

LTR Design

Three different LTRs were designed for labeling p38 complexes (1–3, Figure 1B). All three LTRs contain a benzophenone photo-crosslinker and an alkyne tag that are connected to an ATP-competitive inhibitor through a flexible linker. Upon ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, the benzophenone crosslinker is able to label proteins that are in close proximity to the bound inhibitor.[9] The alkyne tag allows conjugation of labeled proteins to a reporter group for visualization (fluorophore) or affinity enrichment (biotin) through a “click” chemistry reaction.[10] Three different inhibitors that are highly potent and selective for p38 were used as the directing groups for the LTRs (Figure 1B). All three inhibitors occupy the ATP-binding site of p38 and make key hydrogen bonds with the hinge region of this kinase.

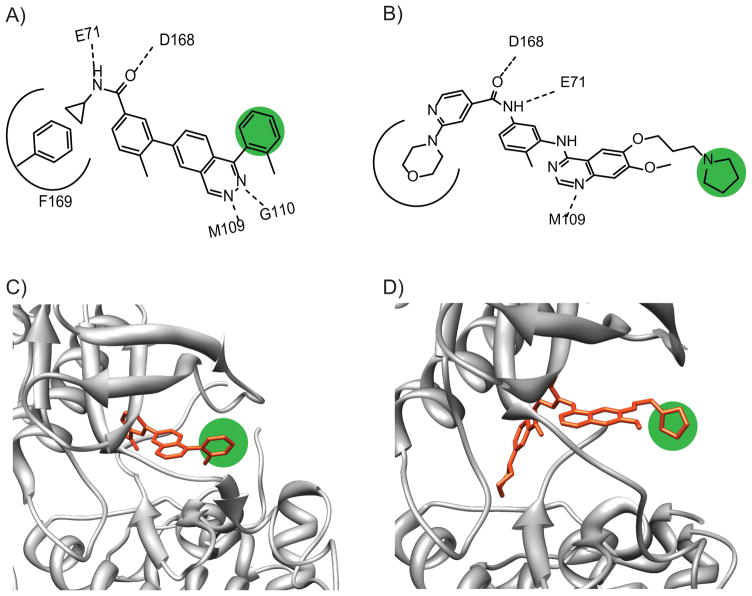

The inhibitor scaffolds of 1 and 2 have been structurally characterized with p38 (Figure 2).[11, 12] LTR 1 is based on a phthalizine inhibitor with a cyclopropyl group that stacks against the activation loop of p38, stabilizing this kinase in an active conformation.[11] LTR 2 is based on a quinazoline inhibitor that contains an extended morphilino-pyridine moiety, which occupies a pocket formed by movement of the activation loop.[12] Combined with a hydrogen bond donor–acceptor pair, this ligand stabilizes an inactive conformation of p38 known as “DFG-out.” We synthesized a third scaffold, 3, which retains the core phthalazine scaffold of 1, but substitutes the morpholino-pyridine moiety of 2 for the cyclopropyl group. We expect that this hybrid molecule will be a highly selective and potent inhibitor that binds analogously to 1, but stabilizes the DFG-out conformation. These three scaffolds have different interactions with p38, and thus their selectivity profiles are expected to differ from one another.[13] Consequently, LTRs with complementary scaffolds can be used to demonstrate that the results obtained are due to interaction with p38, and not an off-target kinase.

Figure 2.

Structures and binding modes of p38-specific ATP-competitive inhibitors. A) A selective p38 inhibitor based on a phthalazine scaffold and its crystal structure contacts. The phthalazine scaffold occupies the purine-binding site of ATP, making key hydrogen bonds with the backbone of the hinge region residues (M109 and G110), as well as hydrogen bonds to the backbone of D168 and the side chain of E71. The cyclopropyl group of the inhibitor packs against F169 of the “DFG” motif. B) A selective p38 inhibitor based on a quinazoline scaffold and its crystal structure contacts. The quinazoline has similar contacts to the phthalazine scaffold, though it lacks one hinge region hydrogen bond. Importantly, the morpholine moiety displaces F169, leading to a “DFG-out” conformation, which is catalytically inactive. C) A crystal structure of the phthalazine scaffold bound to p38 (PDB ID: 2DS6), showing the site chosen for modification (highlighted in green). D) Crystal structure of the quinazoline scaffold bound to p38 (PDB ID: 2BAK), showing the site chosen for modification (highlighted in green).

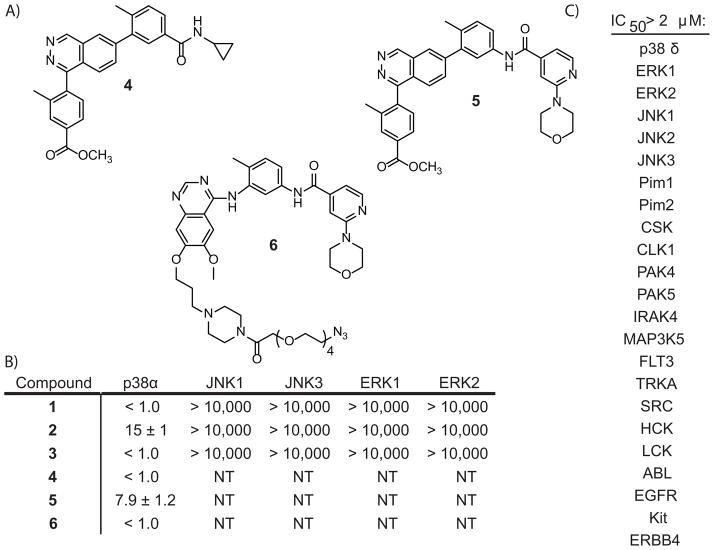

To attach the benzophenone crosslinker and alkyne tag, each inhibitor scaffold was modified at a site that has been shown to be solvent-exposed. Importantly, this site of derivitization should project the photo-crosslinker in the direction of the docking and substrate-binding sites of p38 (Figure 2C,D). To ensure that the LTRs maintain their potency and selectivity for p38, they were tested in an in vitro activity assay against this kinase and several other MAPKs (JNK1, JNK3, ERK1, and ERK2). We were gratified to see that LTRs 1–3 have low to sub-nanomolar IC50s for p38 and show no detectable inhibition of the other MAPKs tested (Figure 3A). This level of potency and selectivity is similar to the parent inhibitors from which these LTRs were derived (Figure 3B).[11, 12] In addition, LTRs 1 and 3 were tested for their inhibition of a large and diverse panel of kinases at a concentration of 2 μM. Even at this relatively high concentration, no other kinases tested were inhibited by more than 50% in the presence of these LTRs.

Figure 3.

A) Structures of the selective p38 inhibitors that were used as competitors in these studies. B) In vitro activities (in nM) of LTRs 1–3 and competitors 4–6 against the MAPKs p38, JNK1, JNK3, ERK1, and ERK2. Values shown are the average of at least three assays ± SEM. C) LTRs 1 and 3 were tested at a 2 μM concentration against a large panel of kinases, and did not inhibit any of the kinases’ activities by 50% or more, except p38α.

Testing with purified proteins

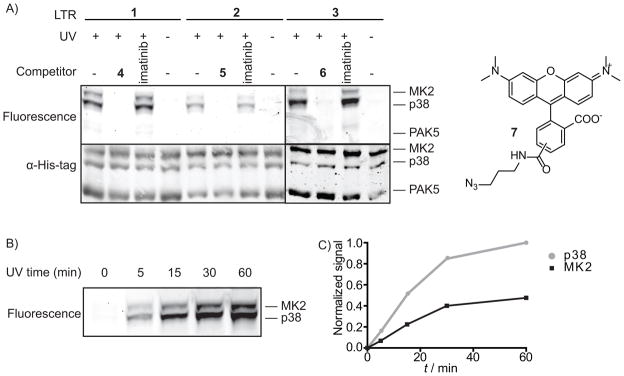

To test the ability of our LTRs to label proteins that interact with p38, we performed crosslinking experiments with p38 and MK2 (a p38 substrate, also known as MAPKAPK-2) in the presence of a control kinase, PAK5, which does not interact with p38, MK2, or the LTRs (Figure 4A). p38, MK2, and PAK5 were incubated with an LTR (1–3), irradiated with UV light, and coupled to rhodamine-azide 7. LTRs 1–3 all successfully labeled both p38 and MK2, with probes 1 and 3 demonstrating more robust labeling than probe 2 (lanes 1, 5 and 9, Figure 4A). However, PAK5 kinase is not labeled, confirming that it does not bind to p38 and does not interact with any of the LTRs. Importantly, the presence of an ATP-competitive p38 inhibitor that does not contain a photo-crosslinking moiety blocks labeling of both p38 and MK2 (lanes 2, 6, and 10, Figure 4A). In contrast, the ABL-selective kinase inhibitor imatinib, which has no significant affinity for p38, was unable to prevent photo-crosslinking. For all three LTRs, labeling was found to be UV dependent, with no signal observed in the absence of UV light (lanes 4, 8, and 12, Figure 4A). Furthermore, labeling with probe 2 increases with UV irradiation time, achieving a plateau after 30 minutes (Figure 4B,C). At all time points, the ratio of p38 to MK2 labeling remains constant (about 3:1 p38 to MK2).

Figure 4.

LTR labeling of p38 and its substrate MK2. Each protein mixture was irradiated with UV light for 30 minutes, and then conjugated to rhodamine-azide 7, followed by SDS-PAGE analysis and in-gel fluorescence scanning. Total protein loading for each sample was determined with an anti-His6 antibody. A) Characterization of LTRs 1–3. Each LTR (500 nM) was incubated with p38 (400 nM), MK2 (400 nM), and PAK5 (400 nM) in the absence or presence of a competitor (4–6 or imatinib at 10 μM) B) UV irradiation time-dependence of LTR labeling with probe 2: fluorescence labeling of p38 and MK2 shows an increase over time. C) Quantitation of bands in B) shows that the labeling ratio of p38 and MK2 remains constant, and begins to plateau at 30 min.

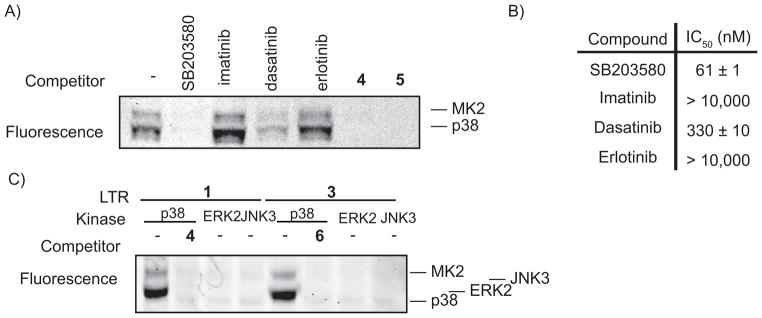

The use of highly selective p38 inhibitors as competitors in photo-crosslinking experiments allows further confirmation that protein labeling is due to association with p38 complexes. To demonstrate this, photo-crosslinking experiments were performed in the presence of ATP-competitive inhibitors that have a range of affinities for p38 (Figure 5A,B). As expected, the EGFR- and ABL-selective inhibitors erlotinib and imatinib (p38(IC50) >10,000 nM), do not block labeling of p38 or MK2. The presence of the ABL and SRC inhibitor dasatinib, which is a moderately potent inhibitor of p38 (p38(IC50) = 330 nM), does not completely block labeling. Conversely, potent and selective p38 inhibitors such as SB203580 (p38(IC50) = 61 nM), 4, and 5 completely prevent labeling at 10 μM.

Figure 5.

Labeling by LTRs is specific. A) Selective p38 inhibitors block p38 and MK2 labeling. LTR 2 (500 nM) was incubated with p38 (400 nM), MK2 (400 nM), and an ATP-competitive inhibitor (10 μM). B) Known kinase inhibitors were tested for their ability to inhibit the activity of p38α. Numbers represent the IC50 values in nM concentration. C) Labeling is dependent on the presence of p38 MAPK. LTRs 1 and 3 (250 nm) were incubated with MK2 (200 nM) and p38 (200 nM), ERK2 (200 nM), or JNK3 (200 nM).

MK2 should be labeled by our LTRs in the presence of p38 and not other MAPKs. To demonstrate this, labeling experiments were performed with MK2 in the presence of the MAPKs p38, ERK2, or JNK3. Significantly, MK2 is not labeled by LTRs 1 and 3 in the presence of ERK2 or JNK3 (Figure 5C). This further establishes that association with p38 mediates protein labeling. Furthermore, JNK3 and ERK2 are also not labeled, which is consistent with the low affinity of these LTRs for ERK2 and JNK3.

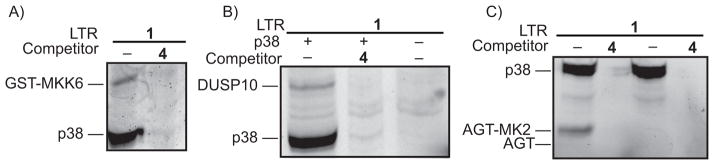

Next, we wished to determine whether our LTRs are able to label a protein that is not a substrate of p38. To do this, the labeling of MKK6 in the presence of p38 was investigated. MKK6 is an upstream activator of p38, with a relatively weak binding affinity.[14] Indeed, GST-MKK6 was labeled with LTR 1 when incubated in the presence of p38 (Figure 6B). Labeling of GST-MKK6 and p38 was prevented in the presence of a selective p38 inhibitor. Thus an activator of p38 – and a weak binding partner – can be labeled with our LTRs.

Figure 6.

LTRs label a diversity of p38 binding partners. Each protein mixture was irradiated with UV light for 30 minutes, conjugated to rhodamine-azide, followed by SDS-PAGE analysis and in-gel fluorescence scanning. A) Labeling of p38 activator GST-MKK6. LTR 1 (500 nM) was incubated with p38 (400 nM) and GST-MKK6 (1 μM) in the absence or presence of competitor 4 (10 μM). B) Labeling of p38 phosphatase DUSP10. LTR 1 (500 nM) was incubated with p38 (400 nM) and DUSP10 (400 nM) in 0.2 mg/mL HEK293 lysate in the presence or absence of competitor 4 (10 μM). C) Labeling of a construct, AGT-MK2, which only interacts with the common docking domain of p38. LTR 1 (500 nM) was incubated with p38 (400 nM) and AGT-MK2 (800 nM) or AGT (800 nM) in the presence or absence of competitor 4 (10 μM).

The dual-specificity phosphatase DUSP10 is known to dephosphorylate p38 and binds to both phosphorylated and dephosphorylated p38 with a low-micromolar affinity.[15–17] Because the association of unphosphorylated p38 with DUSP10 involves no addition of substrates to either molecule, this represents an association that can only be analyzed by protein-protein interaction techniques. We investigated whether our LTR would be effective in labeling DSUP10 (Figure 6B). DUSP10 was labeled in the presence of p38, but not in the absence of p38 or when a competitor was added. This confirms the LTR can label proteins that are neither activators nor substrates.

Finally, we wished to determine the minimal motif required for labeling with our LTR. MK2 is a substrate for p38 that interacts with both the substrate binding cleft and the common docking domain. However, many p38 interacting proteins may only interact with one site of this kinase. To determine whether proteins that only interact with the common docking domain of p38 can be identified, a fusion construct that contains the 30 C-terminal residues of MK2 (AGT-MK2) was generated. These 30 C-terminal residues bind to the common docking domain of p38 and do not interact with the substrate-binding site.[18] As expected, the AGT-MK2 fusion protein was labeled by LTR 1 (lane 1, Figure 6A), while an AGT construct that lacks the MK2 peptide was not (lane 3, Figure 6A). Together, these data demonstrate that a broad diversity of p38-interacting partners can be identified with p38-selective LTRs.

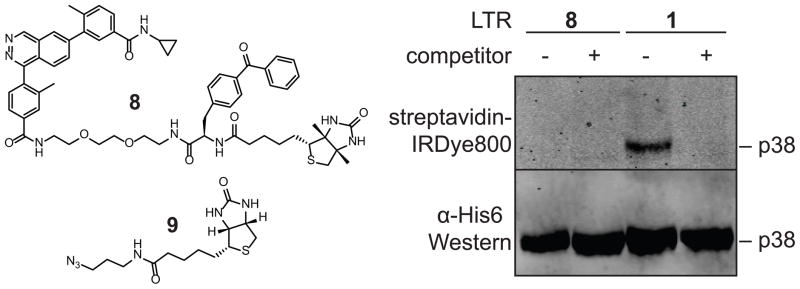

We were curious whether an alkyne moiety is the most efficient handle for proteomic analysis with probes 1–3. To test this, LTR 8, which contains biotin directly conjugated to the probe, was generated. Surprisingly, biotinylation of proteins with LTR 8 could not be detected, whereas LTR 1 efficiently biotinylated proteins after click chemistry with biotin-azide 9 (Figure 7). This suggests that the alkyne is the most efficient handle for visualization and purification of labeled proteins.

Figure 7.

Biotin-conjugated LTR 8 fails to biotinylate proteins of interest. LTR 1 or 8 (500 μM) were incubated with p38 (400 nM) in the presence or absence of competitor 4 and irradiated with UV light (365 nm) for 30 min. Samples with LTR 1 were subjected to click chemistry with biotin-azide 9. All samples were then precipitated and resuspended in loading buffer before being run on a gel and subjected to Western blot analysis with an anti-His6 antibody or fluorophore-conjugated streptavidin.

Using LTRs with proteins from mammalian cells

Mapping the components of cell-signaling complexes is an important goal in biochemistry, and co-immunoprecipitations (co-IPs) have been a key tool in defining many protein-protein interactions. Yet, a fundamental challenge with data from co-IPs is that they cannot determine whether two proteins interact directly, or if their interaction is mediated by another protein that is also pulled down. Furthermore, they often require extensive washes to eliminate non-specifically binding proteins, which often means the loss of information from weak binding partners.

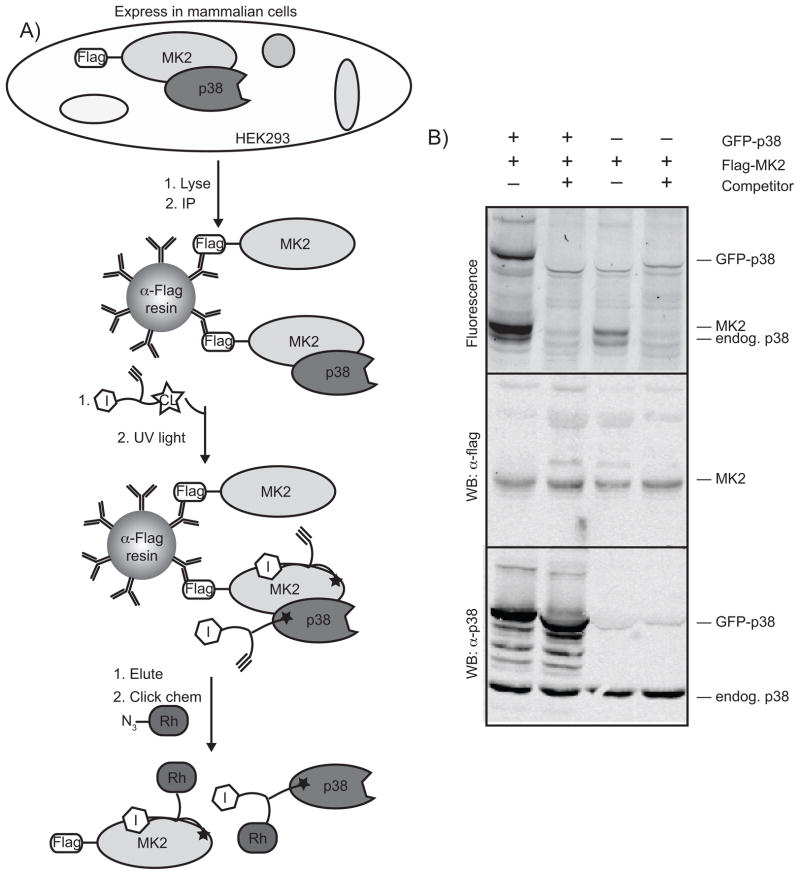

To address these issues, we have included LTRs in the co-IP process to define spatial relationships (Figure 8A). In our procedure, a regular co-IP is first performed with an antibody after cell lysis. Because LTRs impart selectivity, extensive washes are unnecessary after initial protein capture. The LTR is then introduced while the complex is still on the beads, and crosslinking transfers the label to only those proteins in the vicinity of p38. Thus, any protein labeled in this combined co-IP/LTR experiment can be confidently asserted to bind in the vicinity of the p38 active site.

Figure 8.

Crosslinking experiments with immunoprecipitated p38 complexes. HEK293 cells were transfected with flag-tagged MK2 and with no exogenous p38, or with GFP-p38, as indicated. Cells were lysed, and the lysate subjected to an α-flag immunoprecipitation. Beads were transferred to a 96-well plate and were subjected to the crosslinking conditions described in Figure 4. Proteins were eluted with flag peptide and were subjected to click chemistry with rhodamine-azide 7. After precipitation, proteins were run on an SDS-PAGE gel which was scanned for fluorescence before being transferred to nitrocellulose and probed with α-flag or α-p38 antibodies.

To test this, Flag-MK2 was expressed alone or in conjunction with GFP-tagged p38. After an overnight incubation with the lysate, anti-flag beads were washed just once with PBS before being exposed to the LTR and being subjected to UV irradiation. After elution with flag peptide, the samples were subjected to click chemistry with rhodamine-azide 7 to fluorescently tag all LTR-labeled proteins. Labeled proteins are then visualized following SDS-PAGE with in-gel fluorescence. When co-expressed with MK2, both p38 and MK2 are labeled in the presence of p38, and this labeling is selectively competed away with a p38 inhibitor (Figure 8B). MK2 efficiently co-immunoprecipitates p38, to the point that even endogenous levels of p38 are sufficient to provide labeling of MK2. However, the decrease in MK2 labeling with reduced amounts of p38 shows that labeling of MK2 is p38-dependent.

A clear advantage of label transfer reagents based on enzyme inhibitors is that they should be functional in live cells with endogenous proteins, as long as they are cell permeable. Given that our LTRs are substantially larger than the inhibitors they are derived from, we desired to determine whether our LTRs would actually be able to penetrate live cells.

To do so, we took advantage of the property of LTR 1 and its cognate inhibitor 4 of preventing phosphorylation of p38 by its upstream activators. This has previously been reported only for inhibitors which induce the “DFG-out” inactive conformation of the kinase.[12] While a very close analog of 4 has been crystallized with p38 in the active conformation of the kinase, it is also true that this phthalazine inhibitor shares some features with classic DFG-out inhibitors: the presence of an amide donor/acceptor pair, as well as interactions near the DFG motif. Therefore, it is not entirely surprising that this inhibitor is able to block phosphorylation by the upstream MAP kinase kinase.

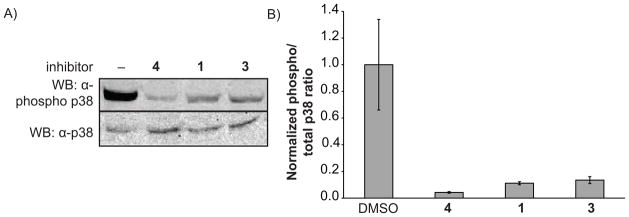

The cell permeability of these inhibitors can be analyzed by preincubation of cells with the LTR, followed by stimulation of the p38 pathway and western blot to determine the extent to which phosphorylation of p38 is inhibited by the LTR (Figure 9A,B). We found that p38 phosphorylation was almost entirely blocked by 2 μM of the parent inhibitor 4, demonstrating that this molecule it at least sufficiently cell permeable to occupy most or all of the p38 binding sites in the cell. We were gratified to see that LTRs 1 and 3 were similarly able to block phosphorylation. This proves that the LTRs are cell permeable, and provides hope that they may be effective at labeling p38 binding partners in cells.

Figure 9.

LTRs are cell permeable. A) Western blots show phosphorylation of p38 is blocked by inhibitors. COS-7 cells in 12-well plates were preincubated with listed small molecules (or DMSO), then stimulated with NaCl. After 30 min, cells were harvested and subjected to western blot analysis for both total p38 and phopho-p38. B) Quantitation of results in part a, conducted in triplicate.

Conclusion

We have developed a set of label transfer reagents that facilitate the identification of proteins that are involved in p38 MAPK signaling complexes. These LTRs use a potent and selective ATP-competitive inhibitor to target a photo-crosslinker and tag to the active site of p38. Upon UV irradiation, proteins that are in close proximity to p38 are covalently crosslinked to an LTR, and an orthogonal chemical handle allows visualization and purification of labeled proteins. We have shown that these LTRs are highly selective for p38 and its binding partners, with no observed cross-reactivity, even with proteins that are at high concentrations. Moreover, the use of competitors with different selectivity profiles should provide even greater confidence that labelled proteins are associated with p38. Besides identifying substrates of p38, p38-directed LTRs also label activators, repressors, and other binding partners. The LTRs are therefore expected to be effective with any p38 binding partner. We cannot exclude the possibility that some binding partners of p38 may interact with sites distant from the active site, or have extremely weak binding affinities for p38, and these may not be labelled by our LTRs. However, we have convincingly shown that labelling of a protein by the LTR provides confidence that it interacts with p38. While the present study has focused on the kinase p38, we expect the use of inhibitor-directed LTRs to be generally applicable to other kinases – or indeed any enzyme – for which potent and selective inhibitors have been designed.

The addition of an LTR to a traditional co-IP experiment greatly expands the useful scope of LTRs. This can provide information on protein-protein interactions with p38 binding partners that can only be expressed in mammalian cells, providing structural details of signalling complexes that cannot be obtained by traditional co-IPs. When a co-IP is combined with an LTR, extensive washes can be eliminated, as we rely on labelling by the LTR to establish connectivity, and blocking with competitor to prove selectivity. Additionally, a co-IP alone can demonstrate that two proteins are associated, but one or more proteins may mediate that interaction. LTRs, on the other hand, will only label proteins in close proximity to the kinase active site, effectively providing structural information about the complex. Thus, we believe these LTRs have the potential to expose the structural arrangement of p38-containing complexes, providing a significant advance on currently available methods.

We have also shown that LTRs are cell permeable. This should permit labelling of endogenous proteins in their native cell environments without the need for any tags or overexpression. LTRs, therefore, have the potential to provide highly precise information about native signalling complexes.

Experimental Section

A. E. Coli Protein expression and purification

All proteins were expressed as fusions with GST (MKK6) or 6 × His (all others) tags. Expression was carried out overnight at 18° C in LB medium, inducing with 0.1–1.0 mM IPTG. Purification was carried out with Ni-NTA or glutathione-agarose resin per standard protocols.

B. Activation of MAP Kinases

p38α was activated by MKK6 according to a previously published protocol.[23]

ERK1 was activated by incubating the following mixture at rt for 1 hour: 50 mM MOPS pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.001% Tween-20, 1 mM DTT, 0.10 mg/mL BSA, 1.3 mM ATP, 2 μM ERK1, 1 μL MKK2 (activating enzyme was of insufficient purity and concentration for accurate protein concentration determination).

ERK2 was activated by incubating the following mixture at rt for 1 hour: 50 mM MOPS pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.001% Tween-20, 1 mM DTT, 0.10 mg/mL BSA, 1.3 mM ATP, 2 μM ERK2, 1 μL MKK2 (activating enzyme was of insufficient purity and concentration for accurate protein concentration determination).

JNK1α2 was activated by incubating the following mixture at rt for 1 hour: 50 mM MOPS pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.001% Tween-20, 1 mM DTT, 0.10 mg/mL BSA, 1.3 mM ATP, 2 μM JNK1α2, 1 μL MKK4, 1 μL MKK7, and 2 μL MAP3K1 (all activating enzymes were of insufficient purity and concentration for accurate protein concentration determination).

JNK3α1 was activated by incubating the following mixture at rt for 1 hour: 50 mM MOPS pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.001% Tween-20, 1 mM DTT, 0.10 mg/mL BSA, 1.3 mM ATP, 2 μM JNK3α1, 1 μL MKK4, 1 μL MKK7, and 2 μL MAP3K1 (all activating enzymes were of insufficient purity and concentration for accurate protein concentration determination).

C. Activity assays with kinases

p38 assay

Inhibitors (initial concentration: 10 μM, 3-fold dilutions: 9 dilutions) were assayed in triplicate or quadruplicate against recombinant full-length activated p38α (final concentration = 1 nM) in an assay also containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 20 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.1% Triton x-100, 0.2 mg/mL BSA, 0.2 mg/mL myelin basic protein, and 0.5 μCi of γ-32P-ATP ([ATP] ≪ Km (ATP)) in a final volume of 30 μL. The reactions were incubated for 2 hours at rt and terminated by transferring 4.6 μL of the reaction mixture to a phosphocellulose membrane. The membranes were washed with 0.5% phosphoric acid (4×) and acetone (1×) and quantitated by phosphorimaging. The scanned membranes were quantified with ImageQuant and converted to percent inhibition. Data was analyzed using Prism Graphpad software and IC50 values were determined using non-linear regression analysis.

ERK1, ERK2, JNK1, JNK2

Inhibitors (initial concentration: 10 μM, 3-fold dilutions: 9 dilutions) were assayed in triplicate against recombinant full-length activated MAPK (ERK1, ERK2 final concentration = 1 nM, JNK1 final concentration = 5 nM, JNK2 final concentration = 20 nM) in an assay also containing 30 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 0.6 mM EGTA, 1 mM Na3VO4, 0.05 mg/mL BSA, 0.2 mg/mL myelin basic protein, and 0.5 μCi of γ-32P-ATP ([ATP] ≪ Km (ATP)) in a final volume of 30 μL. The reactions were incubated for 1 hour at rt and terminated by transferring 4.6 μL of the reaction mixture to a phosphocellulose membrane. The membranes were washed with 0.5% phosphoric acid (4×) and acetone (1×) and quantitated by phosphorimaging. The scanned membranes were quantified with ImageQuant and converted to percent inhibition. Data was analyzed using Prism Graphpad software and IC50 values were determined using non-linear regression analysis.

All other kinase activity assays were carried out with 2 μM of the listed kinase, under conditions previously reported.[19]

D. In vitro labeling of proteins

Figure 4a: MK2 (400 nM), PAK5 (400 nM), and p38 (400 nM) were combined in PBS to a total volume of 50 μL. Competitor (4–6) (10μM) was added (or an equal volume of DMSO) and samples were incubated at rt for 10 min. LTR (1–3) (500 nM) was added and samples were incubated another 10 min at rt. Samples were placed under a handheld UV light at 365 nm, while on ice, for 30 min, followed by general click chemistry conditions (see below). After the gels were scanned, they were transferred to nitrocellulose and were subjected to Western blotting with α-His6 antibody (Cell Signaling).

Figure 4c: MK2 (400 nM) and p38 (400 nM) were combined in PBS to a total volume of 50 μL. LTR 1 (500 nM) was added and samples were incubated another 10 min at rt. Samples were placed under a handheld UV light at 365 nm, while on ice, for up to 30 min, followed by general click chemistry conditions (see below).

Figure 5a: MK2 (400 nM) and p38 (400 nM) were combined in PBS to a total volume of 50 μL. Competitor (SB203580, Imatinib, Dasatinib, Erlotinib, 4, or 5) (10μM) was added (or an equal volume of DMSO) and samples were incubated at rt for 10 min. LTR 2 (500 nM) was added and samples were incubated another 10 min at rt. Samples were placed under a handheld UV light at 365 nm, while on ice, for 30 min, followed by general click chemistry conditions (see below).

Figure 5c: MK2 (200 nM), HeLa lysate (0.5 mg/mL), and a MAP kinase (p38, ERK2, or JNK3) (200 nM) were combined in PBS to a total volume of 50 μL. Competitor (4 or 6) (10μM) was added (or an equal volume of DMSO) and samples were incubated at rt for 10 min. LTR (1 or 3) (250 nM) was added and samples were incubated another 10 min at rt. Samples were placed under a handheld UV light at 365 nm, while on ice, for 30 min, followed by general click chemistry conditions (see below).

Figure 6a: MKK6 (2 μM), p38 (400 nM), and HeLa lysate (0.5 mg/mL) were combined in PBS to a total volume of 50 μL. Competitor (4 or 6) (10μM) was added (or an equal volume of DMSO) and samples were incubated at rt for 10 min. LTR (1 or 3) (500 nM) was added and samples were incubated another 10 min at rt. Samples were placed under a handheld UV light at 365 nm, while on ice, for 30 min, followed by general click chemistry conditions (see below).

Figure 6b: DUSP10 (400 nM), p38 (400 nM), and HEK293 lysate (0.1 mg/mL) were combined in PBS to a total volume of 50 μL. Competitor 4 (10μM) was added (or an equal volume of DMSO) and samples were incubated at rt for 5 min. LTR 1 (500 nM) was added and samples were incubated another 5 min at rt. Samples were placed under a handheld UV light at 365 nm, while on ice, for 30 min, followed by general click chemistry conditions, though without precipitation.

Figure 6c: AGT (800 nM), AGT-MK2 (800 nM), and p38 (200 nM) were combined in PBS to a total volume of 50 μL. Competitor 4 (10μM) was added (or an equal volume of DMSO) and samples were incubated at rt for 10 min. LTR 1 (250 nM) was added and samples were incubated another 10 min at rt. Samples were placed under a handheld UV light at 365 nm, while on ice, for 30 min, followed by general click chemistry conditions (see below).

Figure 7: p38 (400 nM) and HEK293 lysate (0.2 mg/mL) were combined in PBS to a total volume of 50 μL. Competitor 4 (10μM) was added (or an equal volume of DMSO) and samples were incubated at rt for 5 min. LTR 1 or 8 (500 nM) was added and samples were incubated another 5 min at rt. Samples were placed under a handheld UV light at 365 nm, while on ice, for 30 min, followed by general click chemistry conditions, though without precipitation. After the gels were scanned, they were transferred to nitrocellulose and were subjected to Western blotting with α-His6 antibody (Cell Signaling).

E. General Click Chemistry Conditions

2.5 mM rhodamine-azide (1.1 μL), fresh 50 mM TCEP in H2O (1.1 μL), 1.7 mM TBTA in 1:4 DMSO:tBuOH (3.3 μL), and fresh 50 mM CuSO4 in H2O (1.1 μL) were added to each 50 μL reaction after irradiation. The reactions were incubated for 1 hour at rt, then precipitated to remove excess click chemistry reagents: 50 μg BSA was added to each reaction (if no HeLa lysate had been used), along with 600 μL MeOH, 150 μL CHCl3, and 400 μL H2O. The mixtures were vortexed briefly and spun down for 4 min at 16.1K × g. The upper layer was removed, and the remainder was vortexed with 450 μL MeOH and spun down again. The liquid was removed and the pellet was washed with another 450 μL MeOH. The pellet was left to dry for > 5 min. 1× SDS loading buffer (30 μL) was added to each sample. The samples were vortexed briefly, then boiled for 5 min. Each sample (25 μL) was loaded on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. After electrophoresis, the gel was scanned on a Typhoon fluorescent scanner.

F. IP/crosslinking

Two 10-cm plates of HEK293 cells were grown to 95% confluency and transfected with two plasmids, 5 μg of each, using standard FuGENE-HD protocol. Plate 1 received MK2-pDEST26-flag and eGFP-p38; plate 2 received MK2-pDEST26-flag and LifeAct-eGFP. Cells were grown for 24 hrs after transfection, then pushed off the plate and spun down. Cells were resuspended in 1 mL mammalian cell lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM sodium glycerophosphate, 1 mM PMSF, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche)) and lysed by sonication. Lysate was cleared by centrifugation (10 min at max speed at 4 °C) and then added to anti-flag resin slurry (40 μL, Sigma Aldrich) before being placed on an orbital shaker overnight at 4 °C. Beads were then washed once with PBS (500 μL), and beads were transferred to a round-bottom 96-well plate. The beads from each lysate were split into two identical wells after addition of PBS, such that the total volume (including beads) in each well was 50 μL. To one well, 1 mM inhibitor 4 (0.5 μL) was added to a final concentration of 10 μM, and an equal volume of DMSO was added to the other well. After 5 min, 100 μM LTR 1 (1 μL) was added to all wells and incubated at rt 15 min. The plate with samples was placed on ice, and a UV lamp (365 nm) was rested directly on it for 30 min, with plate agitations every 5 min to keep the beads in suspension. Beads were transferred to microcentrifuge tubes, received 0.2 mg/mL flag peptide in PBS (50 μL), and were twirled for 5 min at rt. Supernatant was removed, and beads were eluted with an additional 2 aliquots of 0.1 mg/mL flag peptide in PBS (50 μL each). The eluate then received 20% SDS (to final concentration 1.8%), rhodamine-azide 7 (to final concentration 50 μM), TCEP (to final concentration 1 mM), TBTA (to final concentration 0.1 mM), and CuSO4 (to final concentration 1 mM), and then was incubated at room temperature for 1 hr. Click chemistry reactions then received 50 μg of BSA each and were subjected to precipitation as described in General Click Chemistry Conditions (see above, with volumes appropriately adjusted). Dried protein pellets were resuspended by boiling in 60 μL SDS loading buffer for 5 min. Samples were run on SDS-PAGE gels, scanned for fluorescence, transferred to nitrocellulose, and subjected to anti-flag or anti-GFP Western analysis.

G. Synthesis

The synthesis and characterization of all compounds is described in the Supplementary Information.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Institute of General Medical Science (R01GM086858 to D.J.M.), a Molecular Biophysics Training Grant (NIH 5 T32 GM008268 to S.S.A.), and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation. We thank Sanjay Hari and Carrie Gower for supplying JNKs, ERKs, DUSP10, MAP3K5, MKK2, MKK4, and MKK7.

References

- 1.Manning G, Whyte DB, Martinez R, Hunter T, Sudarsanam S. Science. 2002;298:1912. doi: 10.1126/science.1075762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Whitmarsh AJ. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:828. doi: 10.1042/BST0340828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Skroblin P, Grossmann S, Schafer G, Rosenthal W, Klussmann E. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2010;283:235. doi: 10.1016/S1937-6448(10)83005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cuadrado A, Nebreda AR. Biochem J. 2010;429:403. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ge B, Gram H, Di Padova F, Huang B, New L, Ulevitch RJ, Luo Y, Han J. Science. 2002;295:1291. doi: 10.1126/science.1067289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu G, Kang YJ, Han J, Herschman HR, Stefani E, Wang Y. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:6087. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507610200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferreiro I, Joaquin M, Islam A, Gomez-Lopez G, Barragan M, Lombardia L, Dominguez O, Pisano DG, Lopez-Bigas N, Nebreda AR, Posas F. BMC Genomics. 2010;11:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu R, Kausar H, Johnson P, Montoya-Durango DE, Merchant M, Rane MJ. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21598. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorman G, Prestwich GD. Biochemistry. 1994;33:5661. doi: 10.1021/bi00185a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rostovtsev VV, Green LG, Fokin VV, Sharpless KB. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2002;41:2596. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20020715)41:14<2596::AID-ANIE2596>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herberich B, Cao GQ, Chakrabarti PP, Falsey JR, Pettus L, Rzasa RM, Reed AB, Reichelt A, Sham K, Thaman M, Wurz RP, Xu S, Zhang D, Hsieh F, Lee MR, Syed R, Li V, Grosfeld D, Plant MH, Henkle B, Sherman L, Middleton S, Wong LM, Tasker AS. J Med Chem. 2008;51:6271. doi: 10.1021/jm8005417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sullivan JE, Holdgate GA, Campbell D, Timms D, Gerhardt S, Breed J, Breeze AL, Bermingham A, Pauptit RA, Norman RA, Embrey KJ, Read J, VanScyoc WS, Ward WH. Biochemistry. 2005;44:16475. doi: 10.1021/bi051714v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karaman MW, Herrgard S, Treiber DK, Gallant P, Atteridge CE, Campbell BT, Chan KW, Ciceri P, Davis MI, Edeen PT, Faraoni R, Floyd M, Hunt JP, Lockhart DJ, Milanov ZV, Morrison MJ, Pallares G, Patel HK, Pritchard S, Wodicka LM, Zarrinkar PP. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:127. doi: 10.1038/nbt1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bardwell AJ, Frankson E, Bardwell L. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13165. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900080200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Theodosiou A, Smith A, Gillieron C, Arkinstall S, Ashworth A. Oncogene. 1999;18:6981. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang YY, Wu JW, Wang ZX. Sci Signal. 2011;4:ra88. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2002241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanoue T, Moriguchi T, Nishida E. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:19949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.28.19949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.ter Haar E, Prabhakar P, Liu X, Lepre C. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611165200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hill ZB, Perera BG, Andrews SS, Maly DJ. ACS Chem Biol. 2012;7:487. doi: 10.1021/cb200387g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tasker AZ, Dawei, Pettus Liping H, Rzasa Robert M, Sham Kelvin KC, Xu Shimin, Chakrabarti Partha Pratim. Vol. WO 2008030466 A1 20080313. 2008

- 21.Perera BG, Maly DJ. Mol BioSyst. 2008;4:542. doi: 10.1039/b720014e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hsu TL, Hanson SR, Kishikawa K, Wang SK, Sawa M, Wong CH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:2614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611307104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hintersteiner M, Kimmerlin T, Garavel G, Schindler T, Bauer R, Meisner NC, Seifert JM, Uhl V, Auer M. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:994. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.