Abstract

A screening method was developed for the systematic identification of glycosylated flavonoids and other phenolic compounds in plant food materials based on an initial, standard analytical method. This approach applies the same analytical scheme (aqueous methanol extraction, reverse phase liquid chromatographic separation, and diode array and mass spectrometric detection) to every sample and standard. This standard approach allows the cross-comparison of compounds in samples, standards, and plant materials previously identified in the published literature. Thus, every analysis contributes to a growing library of data for retention times and UV/vis and mass spectra. Without authentic standards, this method provides provisional identification of the phenolic compounds: identification of flavonoid backbones, phenolic acids, saccharides, and acyls but not the positions of the linkages between these subclasses. With standards, this method provides positive identification of the full compound: identification of subclasses and linkages. The utility of the screening method is demonstrated in this study by the identification of 78 phenolic compounds in cranberry, elder flower, Fuji apple peel, navel orange peel, and soybean seed

Keywords: Screening method, LC-DAD-ESI-MS, glycosylated flavonoids, phenolic compounds

INTRODUCTION

Phenolic compounds (phenolic acids, flavonoids, and flavonoid polymers) are secondary metabolites, ubiquitous in the plant kingdom, that have been shown to impact human health (1–3). The U.S. public consumes as much as 250 mg of flavonoids per person per day (3) in a wide variety of forms (fruits, vegetables, nuts, drinks, spices, herbal and botanical supplements, and vitamin and mineral supplements). Accurate assessment of the relationship between ingestion of phenolic compounds and human health requires a food composition database to support clinical and epidemiological studies (4, 5). The large number of phenolic compounds, their structural diversity, the numerous dietary sources, the large variation in concentration, and the diversity of analytical methods present a considerable challenge to developing a comprehensive database. Consequently, a systematic analytical approach is needed for the identification and quantification of flavonoids and other phenolic compounds in the U.S. food supply. Use of a standard screening method for phenolic identification will allow each analysis to contribute to a growing database rather than being just another isolated experiment.

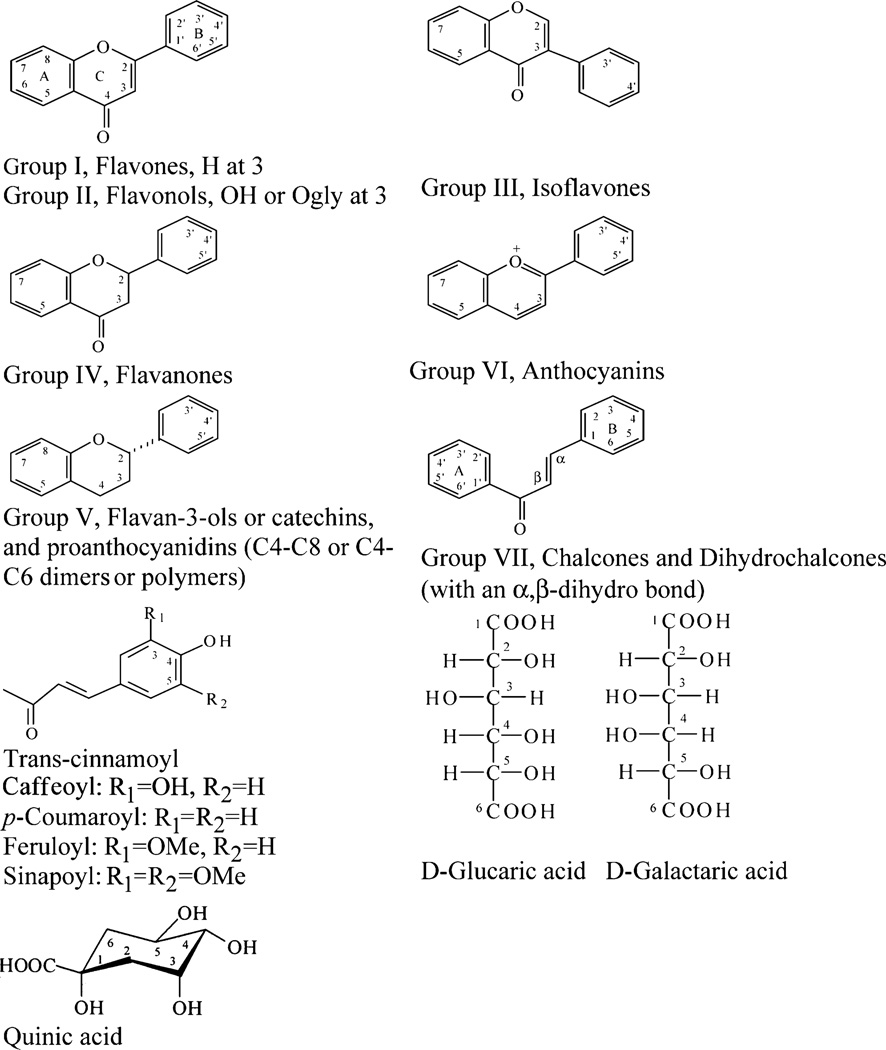

Identification of the thousands of phenolic compounds in plants is a complex undertaking. There are at least eight major subclasses of flavonoids formed from variations in the structural arrangement and positions of the functional groups (Figure 1 and Table 1) (6–8). These eight subclasses, combined with glycosylation at multiple sites with a variety of different saccharides and further acylation of the saccharides, produce more than 5000 chemically distinguishable compounds (8). The flavonoid subclasses and patterns of glycosylation are strongly correlated with plant taxonomy and give rise to a wide range of chemical properties. The range of solubilities is particularly problematic when extracting flavonoids from plants but is very useful when separating them chromatographically (8). Within a subclass, the UV/vis and mass spectra may be quite similar, but appropriate chromatographic columns, solvents, and solvent gradients can usually be selected that will separate small groups of targeted compounds. The challenge is to achieve separation and identification on a larger scale applicable to all flavonoid subclasses and phenolic compounds in general.

Figure 1.

Structures of phenolic compounds analyzed.

Table 1.

Flavonoids Analyzed with Position and Type of Functional Groupsa

| carbon position (see Figure 1) |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 2′ | 3′ | 4′ | 5′ | 6′ | mass | |

| flavones | |||||||||||

| apigenin | OH | OH | OH | 270 | |||||||

| luteolin | OH | OH | OH | OH | 286 | ||||||

| diosmetin | OH | OH | OH | OCH3 | 300 | ||||||

| tricin | OH | OH | OCH3 | OH | OCH3 | 330 | |||||

| sinensetin | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | 372 | |||||

| tangeretin | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | 372 | |||||

| nobiletin | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | OCH3 | 402 | ||||

| flavonols | |||||||||||

| fisetin | OH | OH | OH | OH | 286 | ||||||

| kaempferol | OH | OH | OH | OH | 286 | ||||||

| morin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 302 | |||||

| herbacetin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 302 | |||||

| quercetin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 302 | |||||

| robinetin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 302 | |||||

| isorhamnetin | OH | OH | OH | OCH3 | OH | 316 | |||||

| myricetin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 318 | ||||

| gossypetin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 318 | ||||

| flavanones | |||||||||||

| naringenin | OH | OH | OH | 272 | |||||||

| isosakuranetin | OH | OH | OCH3 | 286 | |||||||

| eriodictyol | OH | OH | OH | OH | 288 | ||||||

| hesperitin | OH | OH | OH | OCH3 | 302 | ||||||

| flavan-3-ols | |||||||||||

| catechin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 290 | |||||

| epicatechin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 290 | |||||

| gallocatechin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 306 | ||||

| epicgallocatechin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 306 | ||||

| anthocyanidins | |||||||||||

| pelargonidin | OH | OH | OH | OH | 270 | ||||||

| cyanidin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 286 | |||||

| peonidin | OH | OH | OH | OCH3 | OH | 300 | |||||

| delphinidin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 302 | ||||

| petunidin | OH | OH | OH | OCH3 | OH | OH | 316 | ||||

| malvidin | OH | OH | OH | OCH3 | OH | OCH3 | 330 | ||||

| isoflavones | |||||||||||

| daidzein | OH | OH | 254 | ||||||||

| genistein | OH | OH | OH | 270 | |||||||

| glycitin | 284 | ||||||||||

| 2′ | 3′ | 4′ | 5′ | 6 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | ||

| chalcones | |||||||||||

| butein | OH | OH | OH | OH | 272 | ||||||

| licochalcone | OCH3 | OH | OH | OH | 272 | ||||||

| okanin | OH | OH | OH | OH | OH | 286 | |||||

| chalconaringenin | OH | OH | OH | OH | 288 | ||||||

| dihydrochalcon | |||||||||||

| phloretin | OH | OH | OH | OH | 274 | ||||||

See Figure 1.

A large number of methods papers and reviews (6–15) have been published on the qualitative and quantitative analysis of flavonoids. Liquid chromatography (LC) with diode array (DAD) and/or mass spectrometric (MS) detection is most frequently used. UV/vis absorption (DAD) is used primarily for quantification but can be used for identification of flavonoid subclasses. MS, tandem MS (MS2), and ion trap MS (MSn), with electrospray (ESI) or atmospheric pressure chemical ionization, are usually used for identification and structural characterization. Recent reviews (14, 15) have shown the value of the use of fractionation patterns to elucidate flavonoid structure. In addition, the capability of new instruments to obtain positive and negative mass spectra at varying fragmentation energies further enhances their usefulness for qualitative analysis.

The majority of the published methods for flavonoids (8–13) have focused on a specific plant material (e.g., oranges) or family of materials (e.g., citrus) and, consequently, on flavonoids from only a few subclasses. This is due to the fact that, despite the large number of glycosylated flavonoids, there are usually less than a dozen (representing only two or three subclasses) in a particular plant material. Consequently, most methods are optimized for separation of only two or three flavonoid subclasses. Because the focus is limited, the potential application of these methods to other flavonoid subclasses and other phenolics has not been explored.

Only a few methods have been reported that were designed for a wide variety of plant foods and, hence, all of the subclasses of flavonoids. In each case, the flavonoids were extracted with aqueous methanol, separated by reverse phase LC, and detected using DAD. Sakakibara et al. (16) identified all of the polyphenols in vegetables and teas in the extract. Quantification was based on comparison of the hydrolyzed extract to aglycone standards. In many cases, identification of specific flavonoids, saccharides, sites of the glycosylation, and acylation was not possible. Arrabi et al. (17) analyzed flavonoids in Brazilian vegetables, and Mattila et al. (18) analyzed flavonoids in fruits and teas using DAD (the latter also used electrochemical detection). Both analyzed the aqueous-methanol extract with no chemical modification. Only a limited number of compounds in each subclass were quantified based on the lack of standards. Harnly et al. (19) analyzed flavonols, flavones, flavanones, flavan-3-ols, and anthocyanidins in fresh fruits, vegetables, and nuts for the U.S. Department of Agriculture National Nutrient Database of Standard Reference (20) using the methods of Merken and Beecher (21, 22). Franke et al. (23) reported the flavonoid levels of Hawaiian fruits and vegetables after hydrolysis.

The technology for on-line screening of phenolic compounds exists (8, 12, 13), and analytical schemes for qualitative analysis have been described (24). However, application of this technology is not routine and the importance of qualitative analysis is generally overlooked. Given the high variability of phenolic compounds in foods (19), even semiquantitative analysis may represent too much effort. Positive identification may be sufficient to meet increased demands for knowledge about the content of U.S. foods.

This study was designed to develop a standard screening method for the systematic identification of glycosylated flavonoids and other phenolic compounds in food materials based on on-line DAD and MS detection. The method was initially designed for glycosylated flavonoids but, with modification, has also proven useful for the identification of flavonoid aglycones, phenolic acids, and polymeric flavonoids. This study demonstrates the usefulness of the screening method by applying it to the identification of phenolic compounds in five plant materials selected for their range of phenolic compounds. Positive identification was achieved for 50 flavonoids and seven hydroxycinnamates and provisional identification for nine fla-vonoids and 12 hydroxycinnamates.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant Materials

Dried soybean seeds (Glycine max L. Merr.) (Leguminosae), elder flowers (Sambucus canadensis L.) (Caprifoliaceae), fresh Fuji apple (Malus domestica Borkh. cv. Fuji) (Rosaceae), cranberry (Vaccinium macrocarpon Aiton) (Ericaceae), and navel orange [Citrus sinensis (L.) Osbeck (navel group) or C. sinensis (L.) Osbech cv. Washington] (Rutaceae) were purchased from local food stores. Honey suckle flowers (Lonicera japonica L.) were bought from Asia Natural Product Inc. (San Francisco, CA). Fresh apple peel, orange peel, and cranberry fruit were cut into small pieces and dried at room temperature, and all of the plant materials were finely powdered and passed through a 20 mesh sieve prior to extraction.

Flavonoid Standards

Apigenin, apigenin 6-C-glucoside (isovitexin), quercetin, rutin (quercetin 3-O-rutinoside), myricetin, kaempferol, hesperetin, hesperidin (hesperetin 7-O-rutinoside), (+)-catechin, (−)- epicatechin, phloretin, phloridzin (phloretin 6′-O-glucoside), and chlorogenic acid were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Luteolin, luteolin 7-O-glucoside, diosmetin, diosmetin 7-O-rutinoside, diosmetin 7-O-hesperinoside, sinegetin, tangeretin, nobiletin, kaempferol 3-O-glucoside, kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside, quercetin 3-O-glucoside, quercetin 3-O-galactoside, quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside, isorhamnetin, isorhamnetin 3-O-glucoside, isorhamnetin 3-O-rutinoside, daidzein, daidzin (daidzein 7-O-glucoside), genistein, genistin (genistein 7-O-glucoside), naringenin, naringenin 7-O-rutinoside, isosakuranetin, and didymin (isosakuranetin 7-O-rutinoside) were purchased from Extrasynthese (Genay, Cedex, France). Glycetein, glycetin, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside, and peonidin 3-O-galactoside were purchased from Indofine Chemical Co. (Somerville, NJ).

3- and 4-Caffeoylquinic acids were prepared by the isomerization of chlorogenic acid (300 mg) as previously described (25) and separated by C18 column chromatography. 3,5-, 3,4-, and 4,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acids were extracted from honey suckle flower (1 lb) and separated by the same C18 column chromatography in this laboratory. The isolated standards were identified by their 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) data (26, 27).

Other Chemicals

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) grade methanol, acetonitrile, acetone, ethanol, formic acid, acetic acid, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), sodium hydroxide, and Bakerbond octadecyl (C18, 40 µm prep LC packing) were purchased from VWR International, Inc. (Clarksburg, MD). Sodium hydroxide, ammonium formate, ammonium acetate, and trifluoroacetic acid were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. HPLC water was prepared from distilled water using a Milli-Q system (Millipore Lab., Bedford, MA).

Screening Method Overview

All samples and standards were subjected to the same analytical procedures described in detail below. First, the flavonoids were extracted from the dried, powdered plant matrix. The extract was injected directly, after hydrolysis, and after heating onto a reverse phase column, and peaks were detected using DAD and MS. Standards were solubilized or extracted and then analyzed using the same separation and detection scheme. Characterized samples, which had positively identified compounds that had been reported in the literature, were extracted using the same extraction scheme and then analyzed directly and after hydrolysis using the same separation and detection scheme. When necessary, ambiguity in the elution order was clarified by duplicating the published separation procedure. The collected data (retention time and UV/vis and mass spectra) were used to identify the flavonoid, phenolic acid, or flavonoid polymer and compared to data for standards and characterized samples.

Extraction Method

Dried ground material (100 mg of the dried plant materials) was extracted with methanol-water (60:40, v/v) using sonication with a FS30 Ultrasonic sonicator (40 kHz, 100 W) (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) for 60 min at room temperature (<35 °C at the end). The extract was filtered through a 0.45 µm Nylon Acrodisk 13 filter (Gelman, Ann Arbor, MI). A 10 (elder flower extract) or 50 µL (all other plant extracts) amount of the extract was injected onto the analytical column for the analysis. In order to avoid error from unexpected degradation of the phenolics, the LC determinations were completed in less than 24 h after the extracts were prepared.

Acid Hydrolysis of Extracts

The filtered extract solution (0.5 mL) was mixed with concentrated HCl (37%, 0.1 mL) and heated in a capped tube at 85 °C for 2 h. Then, 0.4 mL of methanol was added to the mixture and sonicated for 10 min. The solution was refiltered prior to HPLC injection.

Alkaline Hydrolysis of Extracts

A 0.30 mL amount of 4 N NaOH solution was added to a dried concentrated residue (from 1 mL of the extract) of navel orange peel extract and kept at room temperature under N2 atmosphere for 18 h. A 0.15 mL amount of HCl (37%) was added to the reaction mixture to bring the pH to 1, then 0.55 mL of MeOH was added, and the mixture was filtered for LC injection.

Heated Extracts

The filtered extract (~1 mL) was heated in a capped glass tube at 80–85 °C for 16 h to remove the malonyl (or acetyl) group from the glycosides. After it was cooled at room temperature for 30 min, the solution was filtered as above before LC injection.

LC-DAD-ESI/MS Analysis

The LC-DAD-ESI/MS consisted of an Agilent 1100 HPLC (Agilent, Palo Alto, CA) coupled with DAD and mass analyzer (MSD, model SL). A 250 mm × 4.6 mm i.d., 5 µm, Symmetry C18 column (Waters Corp., Milford, MA) with a 20 × 3.9 i.d., 5 µm, Symmetry Sentry guard column was used at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min. The column oven temperature was set at 25 °C. The mobile phase consisted of a combination of A (0.1% formic acid in water) and B (0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile). The gradient was varied linearly from 10 to 26% B (v/v) in 40 min, to 65% B at 70 min, and finally to 100% B at 71 min and held at 100% B to 75 min. The DAD was set at 270, 310, 350, and 520 nm to monitor the UV/vis absorption. UV/vis spectra were recorded from 190 to 650 nm. Mass spectra were acquired using electrospray ionization in the positive and negative ionization (PI and NI) modes at low (100 V) and high (250 V) fragmentation voltages (labeled as PI100, PI250, NI100, and NI250 in the text) and recorded for the range of m/z 100–2000. A drying gas flow of 13 L/min, a drying gas temperature of 350 °C, a nebulizer pressure of 50 psi, and capillary voltages of 4000 V for PI and 3500 V for NI were used. The LC system was directly coupled to the MSD without stream splitting.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Selection of Screening Conditions

The high and low fragmentation voltages for the MS were selected to provide strong mass signals for the aglycone and parent ion, respectively, of rutin in a mobile phase of acetonitrile-water containing 0.1% formic acid. The parent and aglycone ions of rutin were also used for optimization of the drying gas flow, the drying gas temperature, the nebulizer pressure, the capillary voltages, and the flow rate of mobile phase.

Extraction conditions were initially evaluated using the 23 flavonoids (flavones, flavonols, and dihydrochalcones) in Mexican Oregano as a test material. A variety of aqueous solvents (methanol, ethanol, acetone, acetonitrile, and dimethyl sulfoxide), water-solvent ratios, and techniques for physical solvent-sample interaction (sonication, microwave-assisted extraction, high pressure temperature extraction, stirring, and shaking) that have been described in the literature (8–12) were investigated. It was determined that methanol-water (60:40, v/v) and sonication at room temperature for 1 h provided high extraction efficiency for the glycosylated flavonoids with the greatest simplicity and least cost (unpublished results).

The selected extraction conditions were then further evaluated by examining the extraction efficiency of the major glycosylated flavonoids, flavonoid aglycones, and hydroxycinnamates from the five plant materials (cranberry, elder flower, Fuji apple peel, navel orange peel, and soybean seeds) analyzed in this study. In this study, 100 mg of dried sample was extracted with 5.0 mL of solvent. The reference mass for 100% efficiency was based on the mass obtained from either three extraction cycles with methanol-water (60:40, v/v) or from two extraction cycles with dimethyl sulfoxide-water (60:40, v/v). With the exception of three glycosylated flavanones in orange peel, the efficiencies for a single extraction cycle for 24 glycosylated flavonoids, nine flavonoid aglycones, and 11 hydroxycinnamates in the five plant materials exceeded 95%. The extraction efficiencies for the glycosylated flavanones in orange peel were <80%. Thus, this sample preparation scheme is suitable for qualitative determination of the phenolic components of plant materials.

The most frequently used mobile phases reported in the literature (8–12) have been aqueous acetonitrile, aqueous methanol, or a mixture of the two with formic (0.1 or 0.5%), acetic (0.25 and 0.5%) or trifluoroacetic acid (0.05%), ammonium acetate (10 mM), and formate (10 mM). For the screening method, we chose an acetonitrile-water mobile phase with 0.1% formic acid. This selection was based on careful examination of the peak counts from total ion count (TIC) and selected ion monitoring (SIM) chromatograms obtained for a mixture of five glycosylated flavonoids (rutin, quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside, luteolin 7-O-glucoside, genestin, and hesperidin) and one hydroxycinnamate (chlorogenic acid) in each of the mobile phases listed above. In general, 0.1% formic acid offered the highest peak intensity for most of the tested phenolics. Furthermore, aqueous acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid offered the best separation (15). The gradient was chosen to allow the most and least polar compounds to be eluted with reasonable resolution.

Numerous reverse phase C18 and C8 columns have been described in the literature for the separation of phenolic compounds in food plants (8–12), and two comparative studies have been reported (28, 29). In this study, seven reverse phase C18 columns (Symmetry, SymmetryShield, Xterra phenyl, YMC, Luna, Synergi, and Zorbax) were tested using the same, or similar gradients, of acetonitrile-water with 0.1% formic acid to separate the isomers of ten groups of flavonoids. In general, the Symmetry and Zorbax XSD-C18 columns were found to offer the best separations, followed closely by the SymmetryShield and Luna columns. None of the columns, however, was optimum for all regions of the chromatograms. For the best results over the entire range of polarities of the extracted compounds, two or more columns should be used to provide the best separation (unpublished results). For the screening method, we chose the Symmetry column.

The detection limits for rutin, quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside, luteolin 7-O-glucoside, genestin, hesperidin, and chlorogenic acid, based on absorption at 350 nm (270 nm for hesperidin) or TIC, were approximately 4–6 ng (or ~0.01 nmol). Using the SIM mode, the detection limitation was 0.4–0.6 ng (or ~0.001 nmol). This is comparable to other reported values (15).

Identification of Phenolic Compounds in Plant Materials

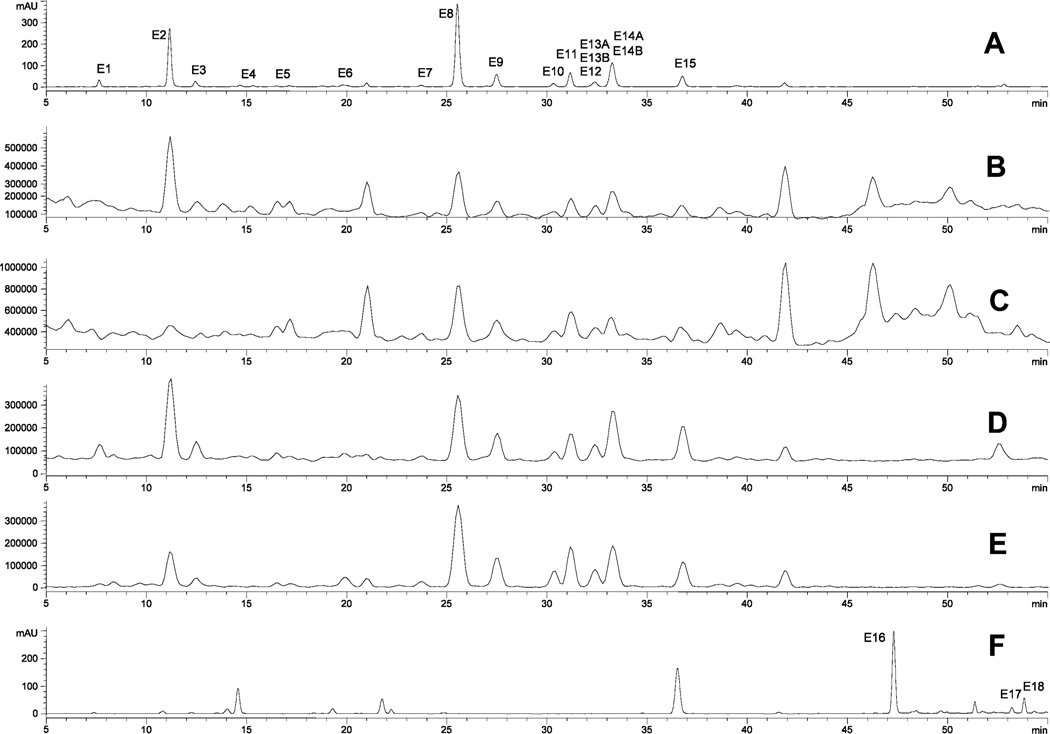

The screening method provides a set of simultaneous UV/vis absorption (one wavelength) and TIC chromatograms, as shown for elder flower in Figure 2. At any time, the full UV/vis spectra (190–650 nm) or mass spectra (m/z 100–2000) of a peak can be viewed, as shown in Figure 3 and Figures 5–7, respectively. From this data, the retention time (tr), maximum absorption wavelengths (λmax), and parent, aglycone, and fragment ion masses can be determined as shown in Tables 2–Table 6. The peak numbers in the tables correspond to the peak labels in the figures. This study analyzed the phenolic contents of five plant materials (cranberry, elder flower, Fuji apple peel, navel orange peel, and soybean seed) (Figures 3 and 5) to illustrate the comprehensiveness of the standard analytical approach. In all, seven glycosylated flavones, 20 glycosylated flavonols, two flavonol aglycones, six polymethoxyflavones, five glycosylated flavanones, two dihydrochalcones, two flavan-3-ols, four proanthocyanins, four glycosylated anthocyanins, seven glycosylated isoflavones, seven hydroxycinnamoylquinic acids, and 12 hydroxycinnamates were identified. Of these, 10 have not been previously identified in these materials. Positive identification was achieved by comparison of the sample data with data acquired from more than 170 standards or with data acquired for materials with compounds previously identified in the published literature. At this time, more than 200 foods have been analyzed in this laboratory using the standard analytical method (unpublished results).

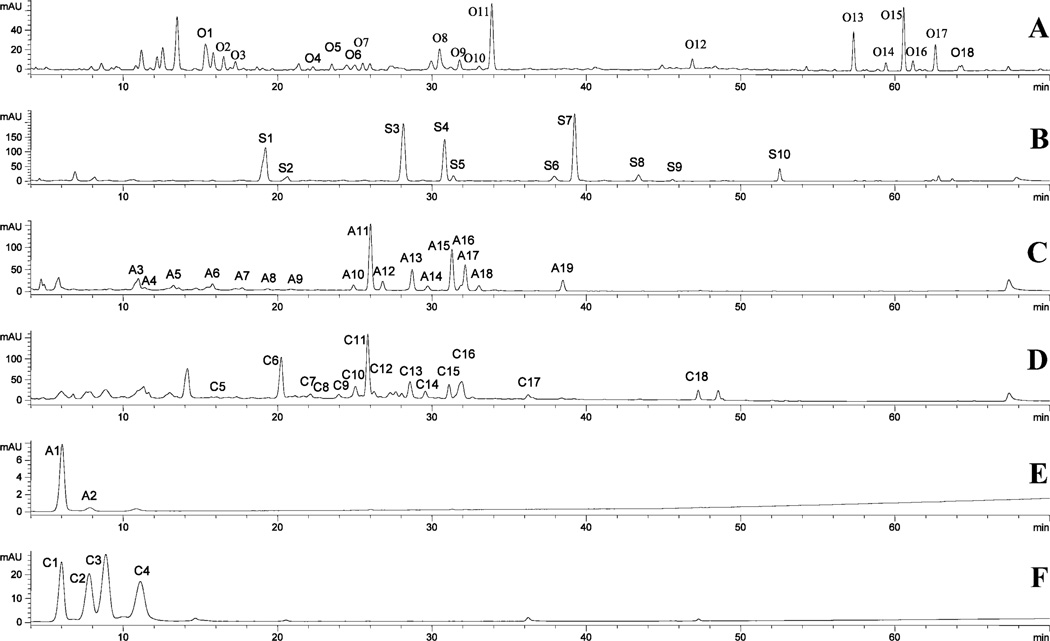

Figure 2.

LC chromatograms of elder flower extract: (A) UV absorption at 350 nm, (B) TIC for PI100, (C) TIC for PI250, (D) TIC for NI100, (E) TIC for NI250, and (F) UV absorption at 350 nm of acid-hydrolyzed elder flower extract.

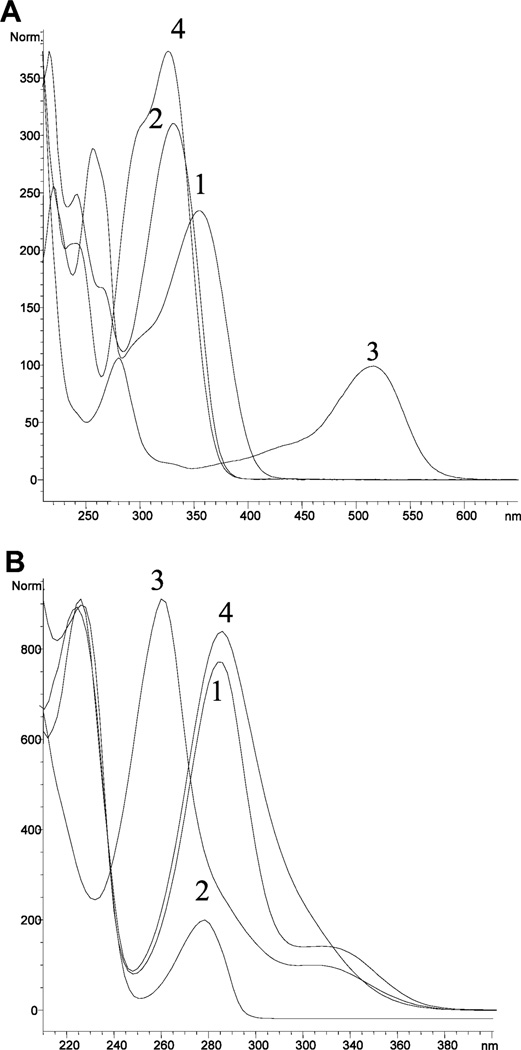

Figure 3.

UV/vis absorption spectra: (A) 1, quercetin 3-O-galactoside (flavonol); 2, sinengetin (flavone); 3, cyanidin 3-O-galactoside (anthocyanin); and 4, chlorogenic acid. (B) 1, hesperidin (flavanone); 2, epicatechin (flavanol); 3, genistin (isoflavone); and 4, phloridzin (dihydrochalcone).

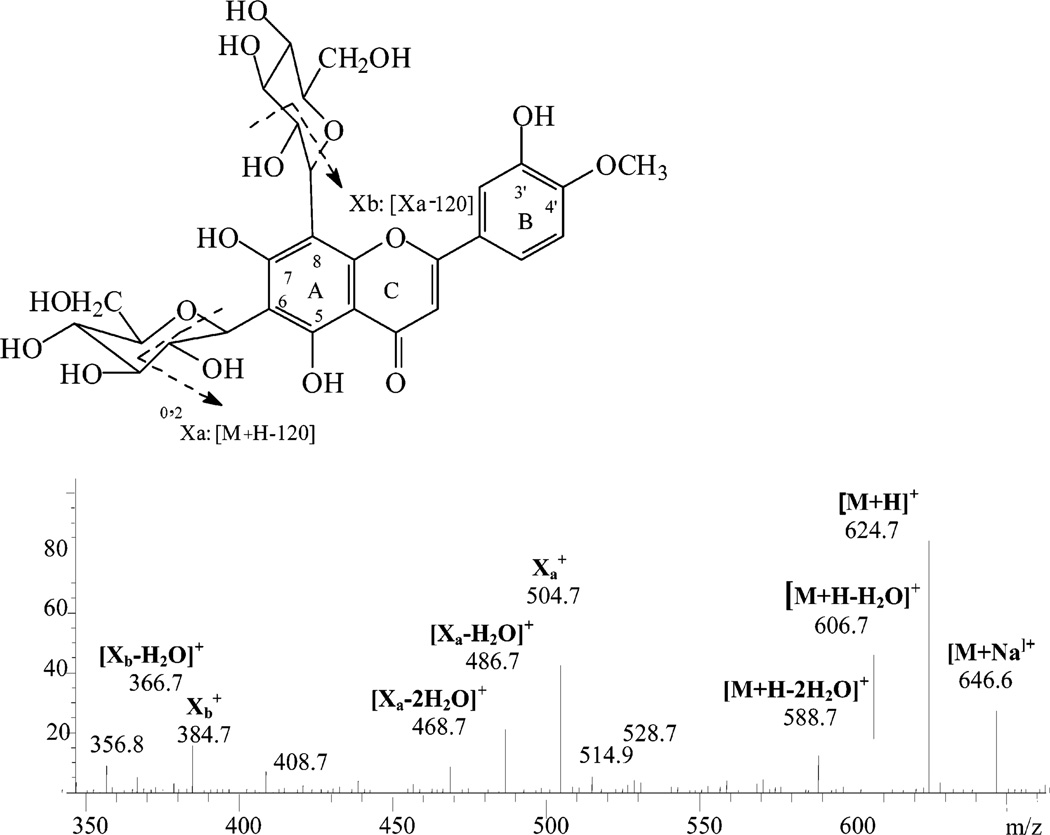

Figure 5.

PI250 mass spectrum of peak O2, diosmetin 6,8-di-C-glucoside, and the related fragmentation scheme.

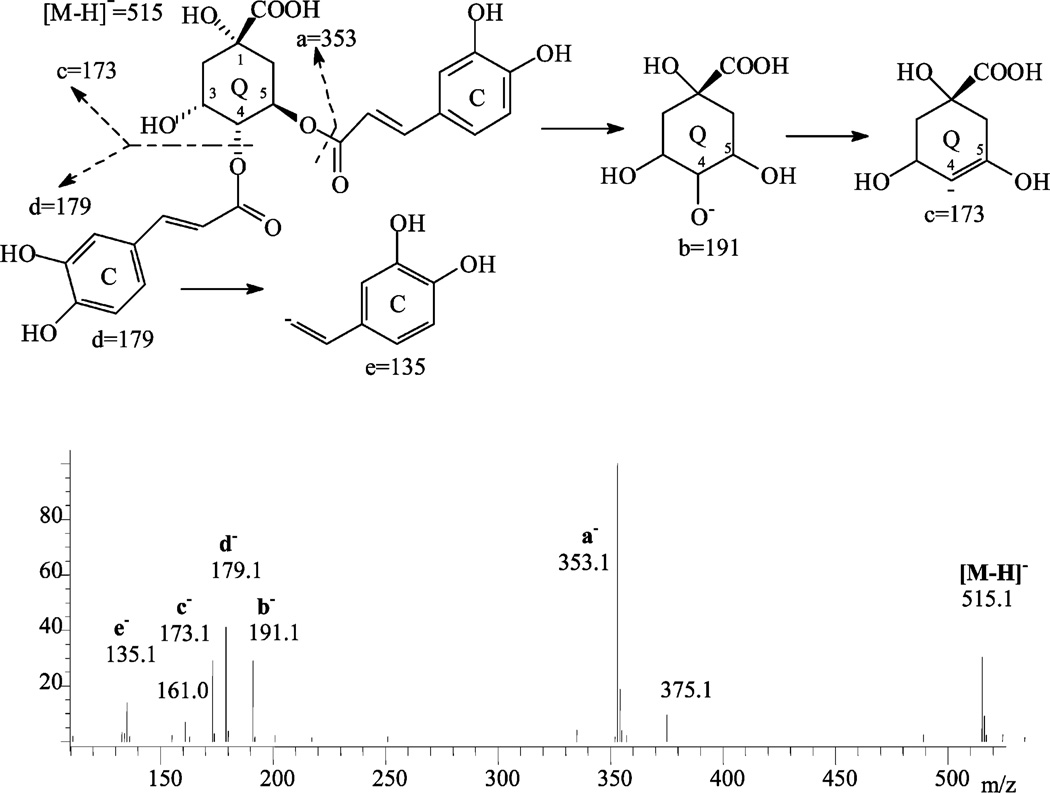

Figure 7.

NI250 mass spectra of peak E15, 4,5-dicaffeyolquinic acid, and the related fragmentation scheme.

Table 2.

Phenolic Compounds in Elder Flower

| peak |

tR (min) |

[M + H]+/ [M - H]− (m/z) |

[A + H]+/[A - H]))− and other NI ions (m/z) |

UV/vis Abs λmax (nm) |

identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hydroxycinnamoylquinic acids, hydroxycinnamoyl-hexoside | |||||

| E1 | 7.62 | −/353 | −/191, 179, 173, 135 | 240, 298sh, 326 | 3-caffeyolquinic acida |

| E2 | 11.10 | −/353 | −/191, 179, 173, 135 | 240, 298sh, 326 | chlorogenic acida |

| E3 | 12.43 | −/353 | −/191, 179, 173, 135 | 240, 298sh, 326 | 4-caffeoylqunic acida |

| E4 | 14.72 | −/341 | −/179 | 240, 298sh, 326 | caffeoyl-hexose |

| E5 | 16.58 | −/337 | −/191, 173, 163 | 230, 312 | p-coumaroylquinic acid |

| E13B | 30.50 | −/515 | −/353, 191, 179, 173, 135 | b | 3,4-dicaffeoylquinic acida |

| E14B | 33.26 | −/515 | −/353, 191, 179, 173, 135 | 240, 298sh, 326 | 3,5-dicaffeoylquinic acida |

| E15 | 36.74 | −/515 | −/353, 191, 179, 173, 135 | 240, 298sh, 326 | 4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acida |

| glycosylated flavonols (group II) | |||||

| E6 | 19.82 | 757/755 | 465, 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin-3-O-triglycoside |

| E7 | 23.68 | 641/639 | 479, 317/315 | 254, 266 sh, 354 | isorhamnetin-3-O-dihexoside |

| E8 | 25.50 | 611/609 | 465, 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | rutina |

| E9 | 27.40 | 465/463 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-glucosidea |

| E10 | 30.36 | 595/593 | 449, 287/285 | 266, 348 | kaempferol 3-O-rutinosidea |

| E11 | 31.12 | 625/623 | 479, 317/315 | 254, 266 sh, 354 | isorhamnetin 3-O-rutinosidea |

| E12 | 30.31 | 551/549 | 303/301 | b | quercetin 3-O-6″-malonylglucoside |

| E13A | 30.41 | 449/447 | 287/284 | b | kaempferol 3-O-glucosidea |

| E14A | 33.17 | 479/477 | 317/315 | b | isorhamnetin 3-O-glucosidea |

| flavonol aglicones detected in the acidic hydrolyzed extract | |||||

| E16 | 47.32 | 303/301 | 256, 372 | quercetina | |

| E17 | 53.21 | 287/285 | 264, 370 | kaempferola | |

| E18 | 53.83 | 317/315 | 256, 372 | isorhamnetina | |

Identification with standard.

Not determined.

Table 6.

Isoflavones in Soybean Seed

| peak |

tR (min) |

[M + H]+/ [M - H]− (m/z) |

[A + H]+/ [A - H]− and other PI ions (m/z) |

UV/vis Abs λmax (nm) |

identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| glycosylated isoflavones and isoflavones (group III) | |||||

| S1 | 19.21 | 417/415 | 255/253 | 252, 300 sh | daidzina |

| S2 | 20.63 | 447/445 | 285/283 | 260, 302 sh | glycitina |

| S3 | 28.15 | 433/441 | 271/269 | 260, 330 sh | genistina |

| S4 | 30.82 | 503/501 | 255/253 | 252, 302 sh | 6″-malonyldaidzin |

| S5 | 31.40 | 533/531 | 285/283 | 260, 302 sh | 6″-malonylgelycitin |

| S6 | 37.93 | 519/517 | 271/269 | 260, 330 sh | malonylgenistin |

| S7 | 39.25 | 519/517 | 271/269 | 260, 330 sh | 6″-malonylgenistin |

| S8 | 43.39 | 255/253 | 252, 304 | daidzeina | |

| S9 | 45.38 | 285/283 | 258, 300 | gelyciteina | |

| S10 | 52.54 | 271/269 | 262, 330 sh | genisteina | |

Identification with standard.

Flavonols and Flavones

As expected, the flavonols and flavones (Tables 2–5) were the most abundant phenolic compounds. Glycosylated flavonols were found in cranberry, elder flower, and apple peel (six in more than one material), and flavonol aglycones were detected in cranberry. Glycosylated flavones and polymethoxy flavones were detected in orange peel.

Table 5.

Phenolic Compounds in Cranberry

| peak |

tR min) |

[M + H]+/ [M - H]− (m/z) |

[A + H]+/[A - H]− and other PI ions (m/z) |

UV/vis Abs λmax (nm) |

identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| anthocyanins (group VI) | |||||

| C1 | 6.01 | 449/447 | 287/285 | 280, 516 | cyanidin 3-O-galactosidea |

| C2 | 7.99 | 419/417 | 287/285 | 280, 516 | cyanidin 3-O-arabinoside |

| C3 | 9.26 | 463/461 | 301/299 | 278, 516 | peonidin 3-O-galactosidea |

| C4 | 11.54 | 433/431 | 301/299 | 278, 516 | peonidin 3-O-arabinoside |

| catechin (group V) | |||||

| C5 | 15.79 | 291/289 | 280 | epicatechina | |

| glycosylated flavonols (group II) | |||||

| C6 | 20.23 | 481/479 | 319/317 | 264, 358 | myricetin 3-O-galctoside |

| C7 | 22.18 | 451/449 | 319/317 | 264, 358 | myricetin 3-O-xylopyranoside |

| C8 | 22.80 | 451/449 | 319/317 | b | myricetin 3-O-arabinopyranoside |

| C9 | 23.23 | 451/449 | 319/317 | 264, 358 | myricetin 3-O-arabinofuranoside |

| C10 | 25.04 | 465/449 | 319/317 | 264, 358 | myricetin 3-O-rhamnosidea |

| C11 | 26.02 | 465/463 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-galactosidea |

| C12 | 27.40 | 465/463 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-glucoside a |

| C13 | 28.71 | 435/433 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-xyloside |

| C14 | 29.73 | 435/433 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-arabinopyranoside |

| C15 | 31.29 | 435/433 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-arabinofuranoside |

| C16 | 30.15 | 449/447 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-rhamnosidea |

| flavonols (group II) | |||||

| C17 | 36.23 | 319/317 | 254, 372 | myricetina | |

| C18 | 48.01 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 370 | quercetina | |

Identification with standard.

Not determined.

Tables 2–5 show that, in general, the parent and aglycone ions for all of the O-glycosylated flavonoids were clearly seen. On the basis of mass differences between the glycosides and the aglycones, it is possible to establish the type of sugar, e.g., a difference of 132 amu for pentose, 146 amu for deoxyhexose, 162 amu for hexose, 248 amu for malonylhexose, and 308 amu for deoxyhexosylhexose (15). The aglycone ions, in conjunction with the UV/vis spectra, permit provisional identification of most flavonols and flavones. A repeat analysis of the sample following hydrolysis permitted positive identification of the common flavones and flavonols by comparison of the sample data with data for the aglycone standards. The remaining questions to be answered to establish positive identification of the molecules are the linkage position(s) for the attached sugar(s) and the exact identity of the sugar(s). This information is achieved, ideally, by direct comparison with standards or with positively identified compounds in other plant materials. Lacking these reference compounds, one must refer to the literature or perform further experiments with MS2, MSn, and NMR.

The identification of the glycosylated flavonols of elder flower can be used to illustrate the operation of the screening method. On the basis of the facts that quercetin (peak E16), kaempferol (E17), and isorhamnetin (E18), in Figure 2F, were the only detected pentahydroxy-, tetrahydroxy-, and tetrahydroxymonomethoxy-flavonols in the hydrolyzed elder flower extract and that the mass differences between the elder flower glycosylated flavonols and the aglycones were 162 or 308 amu, peaks E8-E11, E13A, and E14A should be hexosides and deoxyhexosylhexosides of kaempferol, quercetin, and isorhamnetin. Because 3-O-glycosylated flavones and flavonols show a 12–17 nm shift of UV absorption band I to a shorter wavelength (30), all of the glycosides of elder flower might have the sugars at the 3-position. A comparison of the retention times and UV/vis and mass spectra of these six sample peaks with data compiled for known standards confirmed their identification as rutin (E8), quercetin 3-O-glucoside (E9), kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside (E10), isorhamnetin 3-O-rutinoside (E11), kaempferol 3-O-glucoside (E13A), and isorhamnetin 3-O-glucoside (E14B) (Table 2), respectively. Peak E12 was identified as quercetin 3-O-6″-malonylglucoside since its conversion to quercetin 3-O-glucoside upon heating (a loss of 86 amu) was diagnostic (13). Peak E6 showed ions at m/z 757, 465, and 303, in the PI mode, suggesting that this peak was a quercetin 3-O-triglycoside, which contains two rhamnose and one hexose residue. This is the first identification of some of these glycosylated flavonols in elder flowers, an herb frequently used in the United States (31).

Using similar logic, cranberry peak C6 was identified as myricetin-hexoside, peaks C7–C9 were myricetin pentosides, peak C10 was myricetin 3-O-rhamnoside, peaks C11 and C12 were quercetin hexosides, and peaks C13 and C14 were quercetin pentosides (Figure 4D). Peaks C10–C12 and C16 were identified as myricetin 3-O-rhamnoside, quercetin 3-O-galactoside, quercetin 3-O-glucoside, and quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside, respectively, by direct comparison with standards (Table 5). There were no standards for the remaining six peaks. These peaks, however, could be positively identified by comparison to data published by Vvedenskaya et al. (32). They identified these cranberry peaks based on published literature, direct comparison with standards, and NMR analysis after isolation and purification. The two sets of peaks were compared using the Symmetry column (screening method) and the Zorbax-XSD (C18 column used by Vvedenskaya et al. (32).

Figure 4.

LC chromatograms with UV absorption: (A) navel orange peel (350 nm), (B) soybean seeds (270 nm), (C) Fuji apple peel (270 nm), (D) cranberry (270 nm), (E) Fuji apple peel (520 nm), and (F) cranberry (520 nm).

The eight quercetin O-glycosides (A10–A17) in Fuji apple peel extract (Figure 4C) were tentatively identified as a deoxyhexosylhexoside, two hexosides, four pentosides, and one deoxyhexoside of quercetin. Peaks A10–A12 and A17 were further identified as rutin (quercetin 3-O-rutinoside), quercetin 3-O-galactoside, quercetin 3-O-glucoside, and quercetin 3-O-rhamnoside by direct comparison to standards. Three of the four remaining quercetin 3-O-pentosides were identified by comparison to the positively identified cranberry peaks reported in the literature (32). Fuji apple peel and cranberry extracts were run on both Zorbax-XSD-C18 (chromatogram not shown) and Symmetry C18 columns and produced similar retention times and UV/vis and mass spectra for the peaks of interest. On the basis of this data, peaks A13–A15 were identified as quercetin 3-O-xylopyranoside (A13 equal to C13), quercetin 3-O-arabinopyranoside (A14 equal to C14), and quercetin 3-O-arabinofuranoside (A15 equal to C15). Peak A16 remained an unidentified quercetin 3-O-pentoside (Table 4).

Table 4.

Phenolic Compounds in Fuji Apple Peel

| peak |

tR (min) |

[M + H]+/ [M - H]− (m/z) |

[A + H]+/[A - H]− and other NI ions (m/z) |

UV/vis Abs λmax (nm) |

identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| anthocyanins (group VI) | |||||

| A1 | 6.01 | 449/447 | 287/285 | 280, 516 | cyanidin 3-O-galactosidea |

| A2 | 7.99 | 419/417 | 287/285 | udb | cyanidin 3-O-arabinoside |

| caffoeylquinc acid | |||||

| A3 | 11.10 | −/353 | −/191, 179, 173, 135 | 240, 298 sh, 326 | chlorogenic acida |

| flavan-3-ols (group V) | |||||

| A4 | 11.12 | 291/289 | 280 | catechina | |

| A6 | 15.79 | 291/289 | 280 | epicatechina | |

| proanthocyanidins (group V) | |||||

| A5 | 13.25 | 579/577 | 289/− | 280 | procyanidin dimer |

| A7 | 17.70 | 867/865 | 579, 289/− | 280 | procyanidin trimer |

| A8 | 19.30 | 1155/1153 | 867, 579, 289/− | 280 | procyanidin tetramer |

| A9 | 21.10 | 1443/1441 | 1155, 867, 579, 289/− | 280 ) | procyanidin pentamer |

| glycosylatedflavonols (group II | |||||

| A10 | 25.50 | 611/609 | 465, 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | rutina |

| A11 | 26.02 | 465/463 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-galactosidea |

| A12 | 27.40 | 465/463 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-glucoside a |

| A13 | 28.71 | 435/433 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-xyloside |

| A14 | 29.73 | 435/433 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-arabinopyranoside |

| A15 | 31.29 | 435/433 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-arabinofuranoside |

| A16 | 31.29 | 435/433 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-pentanosideb |

| A17 | 30.15 | 449/447 | 303/301 | 256, 266 sh, 352 | quercetin 3-O-rhamnosidea |

| glycosylated dihydrochalocnes (group VII) | |||||

| A18 | 33.04 | 569/567 | 275/273 | 220, 284 | phloretin pentosyhexoside |

| A19 | 38.48 | 437/435 | 275/273 | 220, 284 | phloridzina |

Identification with standard.

Not determined.

Peaks O7–O9 from the navel orange peel chromatogram (Figure 4A) were identified as a luteolin 7-O-hexoside and two diosmetin 7-O-deoxyhexosylhexosides, respectively. These identifications were based on the mass differences between the glycosides and the aglycones, the fact that luteolin and diosmetin were the only tetrahydroxy- and trihydroxymonomethoxy-flavones detected in the hydrolyzed orange extract, and the fact that the glycosides showed UV/vis absorbance spectra similar to their aglycones as expected for sugars at the 7-position (30). These peaks were further identified as luteolin 7-O-rutinoside, diosmetin 7-O-rutinoside, and diosmetin 7-O-hesperinoside by the direct comparison with standards (Table 3). The literature also shows that these glycosides were previously reported in oranges (33).

Table 3.

Phenolic Compounds in Navel Orange Peel

| peak |

tR (m i n) |

[M + H]+/ [M - H]− (m/z) |

[A + H]+/[A - H]− and other NI ions (m/z) |

UV/vis Abs λmax (nm) |

identification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| hydroxycinnamatesb | |||||

| P1 | 7.17 | −/355 | −/209, 191, 163 | 230, 312 | p-coumarate |

| P2 | 7.94 | −/355 | −/209, 191, 163 | 230, 314 | p-coumarate |

| P3 | 8.58 | −/385 | −/209, 191, 163 | 238, 298 sh, 326 | ferulate |

| P4 | 9.25 | −/355 | −/209, 191, 163 | 230, 314 | p-coumarate |

| P5 | 9.54 | −/355 | −/209, 191, 163 | 230, 314 | p-coumarate |

| P6 | 10.82 | −/355 | −/209, 191, 163 | 230, 314 | p-coumarate |

| P7 | 11.18 | −/385 | −/209, 193, 191 | 238, 298 sh, 326 | ferulate |

| P8 | 11.73 | −/385 | −/209, 193, 191 | 238, 298 sh, 328 | ferulate |

| P9 | 12.56 | −/385 | −/209, 193, 191 | 238, 298 sh, 328 | ferulate |

| P10 | 15.22 | −/355, 385 | −/209, 193, 191, 163 | 238, 298 sh, 330 | p-coumarate + ferulate |

| P11 | 15.38 | −/385 | −/209, 193, 191 | 240, 298 h, 328 | ferulate |

| hydroxycinnamic acids detected in the alkaline hydrolyzed extract | |||||

| P12 | 22.30 | −/163 | 224, 310 | p-coumaric acida | |

| P13 | 24.82 | −/223 | 236,324 | sinapic acida | |

| P14 | 25.22 | −/193 | 236 sh, 324 | ferulic acida,c | |

| glycosylated flavones (group I) | |||||

| O1 | 15.30 | 595/– | 475, 355/– | 272, 334 | apigenin 6,8-di-C-glucoside |

| O2 | 16.50 | 625/– | 505, 385/– | 256, 272, 348 | diosmetin 6,8-di-C-glucoside |

| O5 | 23.51 | 433/– | 313/– | 270, 338 | apigenin 6-C-glucosidea |

| O6 | 25.00 | 463/– | 343/– | 270, 338 | diosmetin 6-C-glucoside |

| O7 | 25.51 | 595/593 | 287/285 | 256, 268, 350 | luteolin 7-O-glucoside |

| O9 | 31.78 | 609/607 | 463, 301/299 | 252, 268, 348 | diosmetin 7-O-rutinosidea |

| O10 | 30.68 | 609/607 | 463, 301/299 | 252, 268, 348 | diosmetin 7-O-neohesperidosidea |

| glycosylated flavanones (group IV) | |||||

| O3 | 17.26 | 743/741 | 581, 419, 273/271 | 286, 336 sh | naringenin triglycoside |

| O4 | 22.28 | 773/771 | 611, 449, 303/301 | 286, 336 sh | hesperitin triglycoside |

| O8 | 30.50 | 581/579 | 419, 273/271 | 284, 336 sh | naringenin 7-O-rutinosidea |

| O11 | 33.87 | 611/609 | 449, 303/301 | 284, 336 sh | hesperidina |

| O12 | 46.87 | 595/593 | 433, 287/285 | 284, 336 sh | didymina |

| polymethoxyflavones (group 1) | |||||

| O13 | 57.30 | 373/– | 268 sh, 330 | sinengetina | |

| O14 | 59.41 | 403/– | 224, 334 | nobiletina | |

| O15 | 60.56 | 403/– | 268, 302 | quercetigenin hexamethyl ether | |

| O16 | 61.16 | 343/– | 272, 302 | tetramethylscutellarein | |

| O17 | 62.62 | 433/– | 268 sh, 342 | heptamethoxyflavone | |

| O18 | 64.33 | 373/– | 226, 330 | tangeretina | |

Identification with standard.

Over half of the hydroxycinnamates were first detected in this plant.

At the same LC condition, the retention time of isoferulic acid is 27.42 min.

Four C-glycosylated flavones were detected in navel orange peel extract. These compounds differed from O-glycosylated flavones in that the acid-resistant C-C linkage was very difficult to cleave. The major fragmentation patterns were cross-ring cleavages of the saccharide residues, with the loss of water between the 2″-hydroxyl of the sugar at C6 or C8 and the 5- or 7-hydroxyl of the aglycone to form a C–O–C linkage (15). For example, the mass spectrum (Figure 5) of peak O2 showed a protonated molecular ion [M + H]+ at m/z 625 and [M + Na]+ at m/z 647 and fragments [M + H – H2O]+ at m/z 607, [M + H – 2H2O]+ at m/z 589, the C-glycoside diagnostic fragment Xa+ (loss of 120) at m/z 505, [Xa – H2O]+ at m/z 487, [Xa – 2H2O]+ at m/z 469, Xb+(loss of 120 × 2) at m/z 385, and [Xb – H2O]+ at m/z 367. These masses are predicted by the scheme of Cuyckens and Claeys (15) shown in Figure 5 and suggest that this compound is glucosylated at C6 and C8 and has hydroxyl groups at the 5- and 7-position of the aglycone. Thus, this flavonoid was identified as diosmetin 6,8-di-C-glucoside. Peak O1 showed a similar mass pattern, except that the analogous ions were 30 amu less than those of diosmetin-6,8-di-C-glucoside. This supported the identification of this compound as apigenin-6,8-di-C-glucoside. Similarly, peak O5 had an X ion peak at m/z 313 indicating the existence of apigenin with only one C-glucosylation. This peak was identified as apigenin 6-C-glucoside (isovitexin) and confirmed by direct comparison with a pure standard. Peak O6 had an X ion peak at m/z 343 for singly C-glucosylated diosmetin. This peak was identified as diosmetin 6-C-glucoside and agreed with previously reported information (33).

The identification of flavonol and flavone aglycones was much simpler than the identification of their glycosides. On the basis of retention times, UV/vis and mass spectra, and comparison with standards, the two flavonols of cranberry were identified as myricetin and quercetin (32). Similarly, five polymethoxyflavones of navel orange peel were assigned to penta-, hexa-, and heptamethoxyflavones, respectively. These compounds were further identified as listed in Table 3 by the comparison with standards and published information (33–35).

Remaining Flavonoids

The screening data for five glycosylated flavanones from navel orange peel (Figure 4A), seven glycosylated isoflavones from soybean seed (Figure 4B), two glycosylated dihydrochalcones, two catechins and four proanthocyanidins from Fuji apple peel (Figure 4C), and four anthocyanins from cranberry and Fuji apple peel (Figures 4E and 5F) are listed in Tables 4 and 5. Mass data provide an initial, provisional identification for each peak of the plant extracts. Positive identification (Tables 3–Table 6) was obtained by direct comparison with standards or with information in the literature (32, 33, 36–38).

The most significant differences between the flavonoids in this section and the flavonols and flavones in the preceding section are in their UV/vis spectra (Figure 3A,B) due to the lack of a conjugated system in the three rings (A, B, and C). Thus, flavanones have a peak maximum between 270 and 295 nm (UV band II) with a weak peak or shoulder between 300 and 360 nm (band I) , as seen for hesperidin in Figure 3B (8, 30). Isoflavones have a strong absorption peak between 250 and 270 nm (band II) with a weak peak between 300 and 340 nm (band I) as seen for genistin in Figure 3B (8, 30). Dihydrochalcones have a strong absorption peak around 284 nm (see phlordzin in Figure 3B). Flavan-3-ols (epicatechin in Figure 3B) and proanthocyanidins have a strong absorption peaks around 280 nm (band II). Anthocyanins have very characteristic spectra with a peak between 240 and 280 nm (band II) and a strong visible peak between 450 and 560 nm (cyanidin 3-O-galactoside in Figure 3A) (8). This latter band makes the anthocyanins easy to distinguish from the other flavonoids.

Equally distinguishing for the proanthocyanidins are their high molecular weights of 290 + 288 (n – 1), where n is the polymer number. The mass spectrometric fragments formed by loss of monomeric residues with 290 and 288 amu, as shown in Table 4 (36). For the screening method, pentamers were the highest polymer observable.

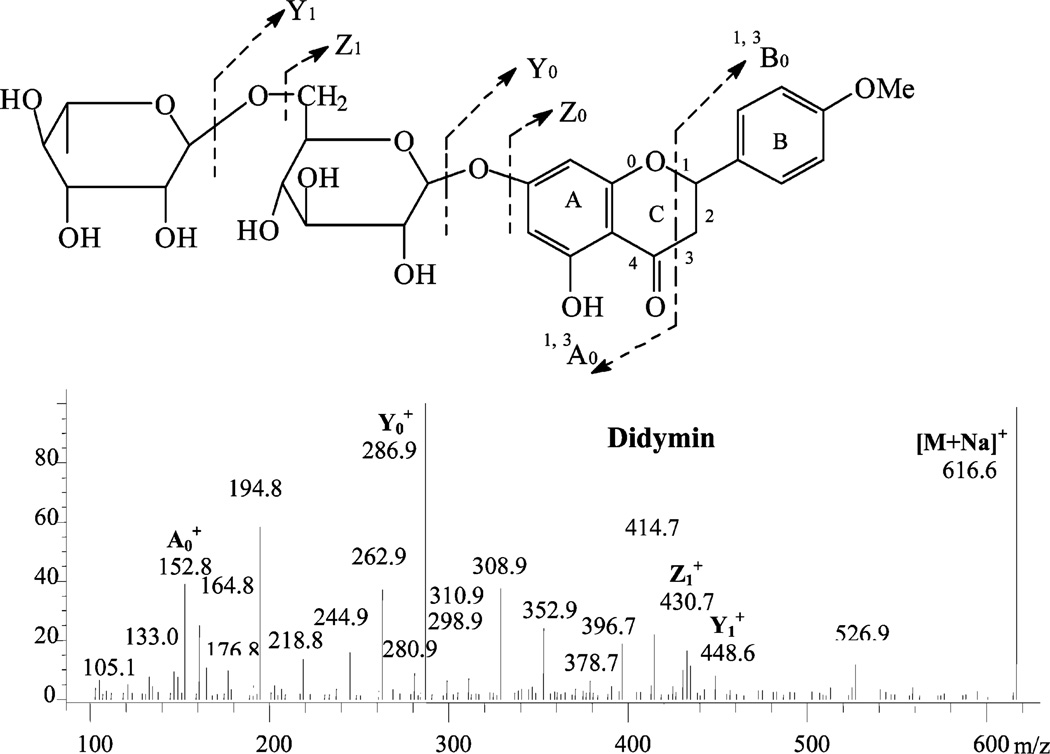

The less stable molecules, such as the glycosylated flavanones and dihydrochalcones, provide parent and aglycone ions as well as important fragments from the cleavage of the aglycone at high fragmentation voltages in both the positive and the negative ion mode, which facilitates identification. For example, the PI250 V voltage mass spectrum (Figure 6) of O12, didymin, showed ions of [M + Na]+ at (m/z 617), Y1 (loss of rhamnosyl), Z1 (loss of rhamnose) at m/z 449, 433, Y0 (loss of rutinosyl to give the aglycone) at m/z 287, and “a” ion (from the cleavage of the aglycone) at m/z 153, as shown by the scheme in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

PI250 mass spectrum of peak O12, didymin, and the related fragmentation scheme.

Hydroxycinnamic Acids and Their Derivatives

The typical UV/vis absorption spectra of hydroxycinnamic acid and their derivatives (consisting of quinic acid or other polyhydroxyaliphatic acids) have a peak between 305 and 330 nm (band I) and a shoulder between 290 and 300 nm (band II) as seen for chlorogenic acid in Figure 3A. The mass spectra show that negative ionization offers much stronger ion peaks and many more fragments than positive ionization. For example, the NI250 spectrum (Figure 7) of peak E15 (4,5-dicaffeoylquinic acid) showed a deprotonated molecular ion at m/z 515 and diagnostic fragments at m/z 353 (a−, due to the loss of one caffeoyl acid residue), m/z 191 (b− for quinic acid), m/z 179 (d− for caffeic acid), m/z 173 (ion c−), m/z 161 (for caffeoyl), and m/z 135 (ion e−). These fragments suggested that this compound has two caffeoyl substitutions and one quinic acid unit (39). This is consistent with the scheme shown in Figure 7. The PI100 and PI250 spectra showed weak protonated molecules [M + H]+ at m/z 517, with strong fragments of [M + H – H2O]+ at m/z 499 (the spectra not shown). These UV/vis and mass spectrometric data suggested that this compound was a dicaffeoylquinic acid. Peaks E13B and E14B showed the same spectrometric data as peak E15 and were also tentatively identified as dicaffeoylquinic acids. Peaks E1–E3 had deprotonated molecules at m/z 353 and were identified as monocaffeoylquinc acids. By direct comparison of the retention time with standards, the six isomers were finally identified as listed in Table 2. In the same manner, peaks E4 and E5 were identified as caffeoyl-hexose and p-coumaroylquinic acid. Most of the hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives were first detected in this plant material (31).

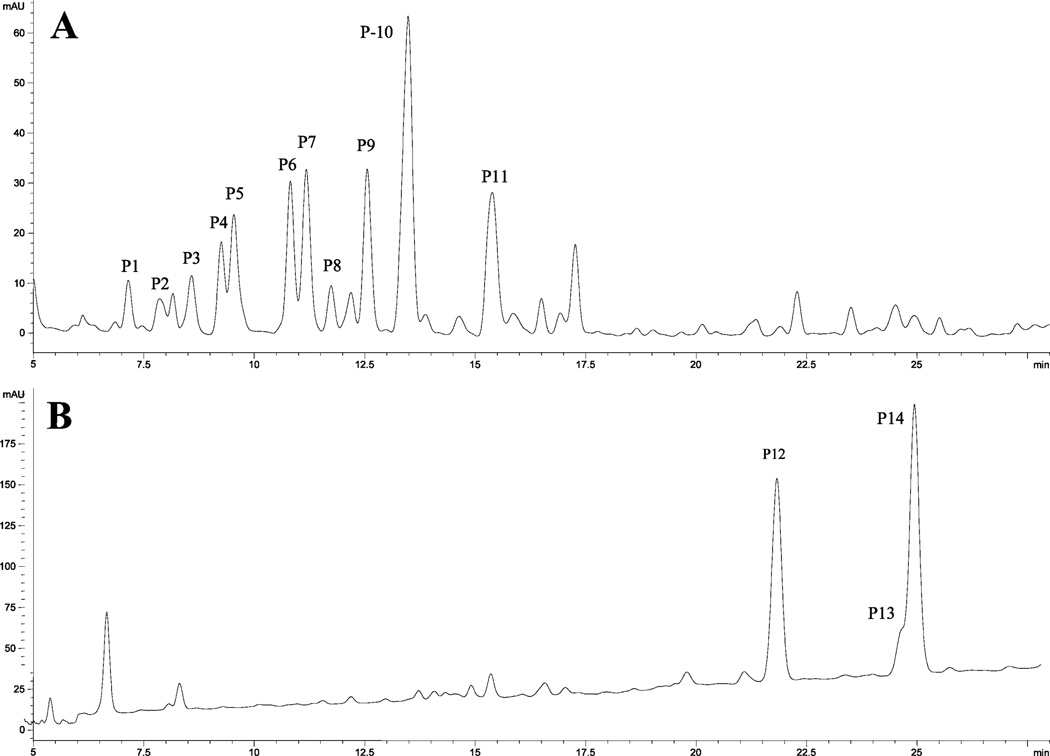

There are 11 detectable hydrolyzable hydroxycinnamates (P1–P11) in navel orange peel (Figure 8A and Table 3), and they produce ferulic acid (P14), p-coumaric acid (P12), and sinapic acid (P13) upon alkaline hydrolysis (Figure 8B and Table 3). Among them, peaks P1, P2, and P4–P6 have deprotonated molecules [M – H]− at m/z 355 and their UV/vis absorption maxima at 312–314 and 230 nm, suggesting that they are p-coumaroylglucaric acids and/or p-coumaroylgalactaric acids (MW═ 356). The remaining peaks have deprotonated ions [M – H]− at m/z 385 and UV/vis absorption maxima at 326–330 and 236–246 nm, suggesting that they are feruloyl-galactaric or glucaric acids (MW═ 386). These peaks had deprotonated ions [M – H]− at m/z 415, which indicated the existence of the same derivatives for sinapic acid. This identification is based on the fact that these compounds have been isolated from orange peel and previously identified by NMR (34, 40, 41). It is noteworthy that six of the peaks were also found in the navy bean and other common beans (Phaseolus Vulgaris L. and its cultivars/varieties) (unpublished results). The four hydroxyl functions of each acid allow a number of positional and/or stereoisomers with the hydroxycinnamic acids. Thus, the structures of these isomeric hydrolyzable hydroxycinnamates cannot be completely determined using LC-MS or LC-MSn techniques at this stage.

Figure 8.

LC chromatograms (350 nm) for (A) the hydroxycinnamates of navel orange peel and (B) the alkaline-hydrolyzed extract of navel orange peel.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Office of Dietary Supplements at the National Institutes of Health under an Interagency Agreement.

LIERATURE CITED

- 1.Hertog MGL, Kromhout D, Aravanis C, Blackburn H, Buzina R, Fidanza F, Giampaoli S, Jansen A, Menotti A, Nedeljkovic S, Pekkarinen M, Simic BS, Toshima H, Feskins EJM, Holman PCH, Katan MB. Flavonid intake and long-term risk of coronary heart disease and cancer in the seven countries study. Arch. Intern. Med. 1995;155:381–386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinmetz KA, Potter JD. Vegetables, fruit, and cancer prevention: A review. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1996;96:1027–1039. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(96)00273-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Manach C, Scalbert A, Morand C, Remesy C, Jimenez C. Bioavailability and bioefficacy of polyphenols in humans. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2004;79:727–747. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pennington JAT. Food composition databases for bioactive components. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2002;15:419–434. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beecher GR. Overview of dietary flavonoids: Nomenclature, occurrence and intake. J. Nutr. 2003;133(Suppl.):3048S–3054S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.10.3248S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Escarpa A, Gonzales MC. An overview of analytical chemistry of phenolic compounds in foods. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2001;31:57–139. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anderson OM, Markham KR, editors. Flavonoids, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Applications. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Robards K. Strategies for the determination of bioactive phenols in plants, fruits and vegetables. J. Chromatogr. A. 2003;1000:657–691. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(03)00058-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merken HM, Beecher GR. Measurement of food flavonoids by high-performance liquid chromatography: A review. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:578–599. doi: 10.1021/jf990872o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naczk M, Shahidi F. Extraction and analysis of phenolics in food. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;1054:95–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Molnár-Perl I, Fu¨zfai Zs. Chromatographic, capillary electrophoretic and capillary electromatographic techniques in the analysis of flavonoids. J. Chromatogr. A. 2005;1073:201–227. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2004.10.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Rijke E, Out P, Niessen WMA, Ariese F, Gooijer C, Brinkman UATh. Analytical separation and detection methods for flavonoids. J. Chromatogr. A. 2006;1112:31–63. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He X-G. On-line identification of phytochemical constituents in botanical extracts by combined high-performance liquid chromatographic-diode array detection-mass spectrometric techniques. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;880:203–230. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stobiecki M. Application of mass spectrometry for identification and structural studies of flavonoid glycosides. Phytochemistry. 2000;54:237–256. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9422(00)00091-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cuyckens F, Claeys M. Mass spectrometry in the structural analysis of flavonoids. J. Mass Spectrom. 2004;39:1–15. doi: 10.1002/jms.585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sakakibara H, Honda Y, Nakagawa S, Ashida H, Kanazawa K. Simultaneous determination of all poylphenols in vegetables, fruits, and teas. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2003;51:571–581. doi: 10.1021/jf020926l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Arabbi PR, Genovese MI, Lajola FM. Flavonoids in vegetable foods commonly consumed in Brazil and estimated ingestion by the Brazilian population. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:1124–1131. doi: 10.1021/jf0499525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mattila P, Astola J, Kumpulainen J. Determination of flavonoids in plant material by HPLC with diode array and electroarray detections. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:5834–5841. doi: 10.1021/jf000661f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harnly JM, Doherty RF, Beecher GR, Holden JM, Haytowitz DB, Bhagwat S, Gebhardt S. Flavonoid content of U.S. fruits, vegetables, and nuts. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:9966–9977. doi: 10.1021/jf061478a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.U.S. Department of Agriculture, National Nutrient Database. Release #2, database for the flavonoid content of selected foods. www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp.

- 21.Merken HM, Beecher GR. Liquid chromatographic method for the separation and quantification of prominent flavonoid aglycones. J. Chromatogr. A. 2000;897:177–184. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9673(00)00826-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Merken HM, Merken CD, Beecher GR. Kinetics method for the quantitation of anthocyanidins, flavonols, and flavones in foods. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2001;49:2727–2730. doi: 10.1021/jf001266s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franke AA, Custer LJ, Arakaki C, Murphy SP. Vitamin C and flavonoid levels of fruits and vegetables consumed in Hawaii. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2004;17:1–35. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nyiredy S. Separation strategies of plant constituents-current status. J. Chromatogr. B. 2004;812:35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.08.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagels L, Herrmann K, Brucker JD, Potter HD. High-performance liquid chromatographyic separation of naturally occurrence esters of phenolic acids. J. Chromatogr. A. 1980;187:181–187. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nakatani N, Kayano S-I, Kikuzaki H, Sumino K, Katagiri K, Mitani T. Identification, quantitative determination, and anti-oxidative activities of chlorogenic acid isomers in prune (Prunus domestica L) . J. Agric. Food Chem. 2000;48:5512–5516. doi: 10.1021/jf000422s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Islam MS, Yoshimoto M, Yahara S, Okuno S, Ishiguro K, Yamakawa S. Identification and characterization of foliar polyphenolic compound in sweetpotapo (Ipomoea batatas L.) enotypes. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:3718–3722. doi: 10.1021/jf020120l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuyckens F, Claeys M. Optimization of a liquid chromatography method based on simultaneous electrospray ionization mass spectrometric and ultraviolet photodiode array detection for analysis of flavonoid glycosides. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2002;16:2341–2348. doi: 10.1002/rcm.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Crozier A, Jensen E, Lean MEJ, Mcnald MS. Quantitative analysis of flavonoids by reversed-phase highperformance liquid chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 1997;761:315–301. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mabry TJ, Markham KRMB, Thomas MB. The ultraviolet spectra of flavones and flavonols. The ultraviolet spectra of isoflavones, flavanones and flavanols. Chapters V and VI, pp 41–45 and 165–166. In: Mabry TJ, Markham KR, Thomas MB, editors. The Systematic Identification of Flavonoids. New York: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung AY, Foster S. Elder flowers (American and European) In: Leung AY, Foster S, editors. Encyclopedia of Common Natural Ingredients used in Food, Drugs and Cosmetics. 2nd ed. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 1996. pp. 220–222. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vvedenskaya IO, Rosen RT, Guido JE, Russell DJ, Mills KA, Vorsa N. Characterization of flavonols in cranberry (Vaccium macrocarpon) powder. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:188–195. doi: 10.1021/jf034970s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dugo P, Presti ML, Ohman M, Fazio A, Dugo G, Mondello L. Determination of flavonoids in Citrus juices by micro-HPLC-ESI/MS. J. Sep. Sci. 2006;28:1149–1156. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200500053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Manthey JA. Fractionation of orange peel phenols in ultrafiltered molasses and mass balance studies of their antioxidant levels. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:7586–7592. doi: 10.1021/jf049083j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weber B, Hartmann B, Stockigt D, Schreiber K, Roloff M, Bertram H-J, Schmidt CO. Liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry and liquid chromatography/nuclear magnetic resonance as complementary analytical techniques for unambiguous identification of polymethoxylated flavones in residues from Molecular distillation of orange peel oils (Citrus sinensis) . J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006;54:274–278. doi: 10.1021/jf051606f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alonso-Salces RM, Ndjoko K, Queiroz EF, Ioset JR, Hostettmann K, Berrueta LA, Gallo B, Vicente F. On-line characterization of apple polyphenols by liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry and ultraviolet absorbance detection. J. Chromatogr. A. 2004;1045:89–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seeram NP, Adams LS, Hardy ML, Heber D. Total cranberry extract versus its phytochemical constituents: Antiproliferative and synergistic effects against human tumor cell lines. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2004;52:2512–2517. doi: 10.1021/jf0352778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kudou S, Fleury Y, Welti D, Magnolato D, Uchida T, Kitamura K, Okubo K. Malonyl isoflavone glycosides in soybean seeds (Glycine max Merrill) Agric. Biol. Chem. 1991;55:2227–2233. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fang N, Yu S, Prior RL. LC/MS/MS characterization of phenolic constituents in dried plums. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002;50:3579–3585. doi: 10.1021/jf0201327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Risch B, Hermann K, Wray V, Grotjahn L. 2¢-(E)-O-p-coumaroylgalactaric acid and of 2′-(E)-O-feruloylgalactaric acid in citrus. Phytochemistry. 1987;10:3307–3309. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Risch B, Hermann K, Wray V. (E)-O-p-coumaroyl-derivatives of glucaric acid in citrus. PHYTOCHEMISTRY. 1988;10:3307–3309. [Google Scholar]