Abstract

Two models are proposed to explain Notch function during helper T (Th) cell differentiation. One argues that Notch instructs one Th cell fate over the other, whereas the other posits that Notch function is dictated by cytokines. Here we provide a detailed mechanistic study investigating the role of Notch in orchestrating Th cell differentiation. Notch neither instructed Th cell differentiation nor did cytokines direct Notch activity, but instead, Notch simultaneously regulated the Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell genetic programs independently of cytokine signals. In addition to regulating these programs in both polarized and non-polarized Th cells, we identified Ifng as a direct Notch target. Notch bound the Ifng CNS-22 enhancer, where it synergized with Tbet at the promoter. Thus, Notch acts as an unbiased amplifier of Th cell differentiation. Our data provide a paradigm for Notch in hematopoiesis, with Notch simultaneously orchestrating multiple lineage programs, rather than restricting alternate outcomes.

Naïve CD4+ T cells are responsible for controlling both intracellular and extracellular infections. Although developmentally mature, naïve CD4+ T cells require activation in order to adopt one of several effector programs, including: the interferon-γ (IFN-γ) producing T helper 1 (Th1) cell, the interleukin-4 (IL-4) producing T helper 2 (Th2) cell, and the interleukin-17 (IL-17) producing T helper 17 (Th17) cell. These three Th subsets serve different functions. Th1 cells are necessary to combat intracellular pathogens and mediate autoimmune diseases, such as graft-versus-host disease (GVHD). Th2 cells are essential effectors during parasitic helminth infection and also mediate airway hypersensitivity and allergic inflammation. Th17 cells are critical for controlling extracellular bacterial and fungal infections and are also responsible for autoimmunity (Coghill et al., 2011).

The T helper cell program adopted by a naïve CD4+ T cell is instructed both by extracellular molecules, such as cytokines, and intracellular molecules, such as the Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell transcription factors, Tbet, Gata3, and Rorγt respectively. Notch has also been proposed to mediate Th cell differentiation, where it functions to relay intercellular signals from the membrane to the nucleus in order to instruct Th cell differentiation (Amsen et al., 2009).

Notch signaling initiates when a Notch ligand interacts with a Notch receptor leading to a series of proteolytic cleavages that release the Notch intracellular domain (ICN) from the cell membrane; whereupon it translocates to the nucleus and forms a transcriptional activation complex with the transcription factor RBPJ and a member of the Mastermind-like (MAML) family (Kopan and Ilagan, 2009). Compelling cases have been made for Notch involvement in both Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation. Manipulating Notch ligand mediated stimulation of CD4+ T cells preferentially instructed Th1 or Th2 cell programs, suggesting that individual Notch ligands have different instructive capacities (Amsen et al., 2004; Maekawa et al., 2003; Okamoto et al., 2009).

Loss of function studies also demonstrated that Notch instructed the Th1 cell program in vitro and promoted the CD4+ T cell IFNγ response in a murine GVHD model (Minter et al., 2005; Skokos and Nussenzweig, 2007; Zhang et al., 2011). In contrast, other reports showed that Notch was required to instruct the Th2 but not the Th1 cell program (Amsen et al., 2009; Amsen et al., 2004; Fang et al., 2007; Kubo, 2007; Tu et al., 2005). More recently, Notch was found to regulate the Th17 cell signature genes Il17a and Rorc, suggesting the bi-potential instructional model may not be sufficient to explain Notch function in Th cell differentiation (Keerthivasan et al., 2011; Mukherjee et al., 2009). While the instructional model posits that ligands direct Notch function during Th cell differentiation, an alternative model argues that Notch target gene selectivity is dictated by upstream cytokine signals (Ong et al., 2008). Despite the differences between these models, both contend that Notch has the capacity to discriminately activate different Th cell programs. Thus, the paradox remains: how can such a basic signaling module selectively drive the differentiation of multiple distinct lineages?

In order to address these controversies, we investigated the molecular mechanisms by which Notch orchestrates Th cell differentiation. We find that Notch neither initiates a single helper T cell program nor do cytokine signals dictate the outcome of Notch signaling. Instead, Notch simultaneously regulates the Th1, Th2, and Th17 genetic programs independently of cytokine signals. Even under strong polarizing conditions, Notch directly regulates critical effectors of Th1 Th2, and Th17 cell differentiation. In addition to Il4, Tbx21, Gata3-1a, Il17a, and Rorc, we identify Ifng as a direct Notch target. Notch regulates Ifng by binding to a highly conserved RBPJ motif in the Ifng CNS-22 and synergizes with Tbet activity at the Ifng promoter. These data support a model in which Notch integrates and amplifies cytokine-derived signals, instead of acting as a transcriptional driver or a downstream accessory of cytokines. Not only do our data unify the disparate data on Notch and Th cell differentiation but they also offer an alternative view of Notch function in the hematopoietic system, whereby Notch reinforces multiple fates rather than restricting alternate outcomes.

Results

Notch signaling is dispensable for Th2 cell initiation during Trichuris muris infection

We previously showed that CD4+ T cells expressing the pan-Notch inhibitor dominant negative mastermind (DNMAML), which binds the Notch:RBPJ dimer but fails to transactivate, do not mount an effective Th2 cell response against the intestinal helminth Trichuris muris and fail to clear infection with normal kinetics (Tu et al., 2005). The outcome of T. muris infection depends on the balance of Th1 cells, which are responsible for chronic infection, and Th2 cells, which are required for parasite expulsion and resistance to infection (Artis et al., 2002; Blackwell and Else, 2001; Cliffe and Grencis, 2004; Cliffe et al., 2005; Else et al., 1994). While Notch was necessary for optimal Th2 cell-dependent immunity in this infection model, it remained unclear whether Notch was essential to initiate Th2 cell differentiation or instead, was required to generate the optimal balance of Th1 and Th2 cells. To test this, Cd4-Cre (CC) and Cd4-Cre x DNMAMLFL/FL (CCD) mice were infected with T. muris and CCD mice were treated with neutralizing anti-IFNγ mAbs for the duration of infection. If Notch were required to initiate Th2 cell differentiation, anti-IFNγ treated CCD mice should remain susceptible to T. muris infection. Alternatively, if Notch played a greater role in generating an optimal Th2 cell response, then IFNγ blockade should be sufficient to relieve any inhibitory effects of a suboptimal Th1:Th2 ratio on infection-induced Th2 differentiation.

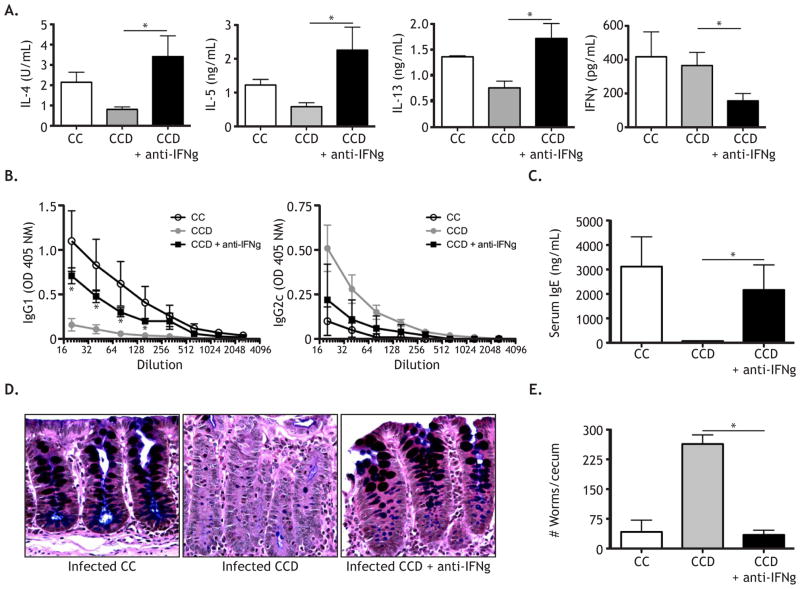

As expected, mesenteric lymph node cells from the control CC mice displayed robust IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 responses upon restimulation (Figure 1A). Consistent with our previous findings, CCD mice demonstrated impaired Th2 cell cytokine responses (Figure 1A). In contrast, CCD mice receiving anti-IFNγ mAb treatment restored IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 production and diminished IFNγ production, suggesting that Notch was not required to initiate Th2 responses (Figure 1A). In agreement with the cytokine data, CCD mice displayed an impaired protective T. muris specific IgG1 response and an elevated non-protective T. muris specific IgG2c response. In contrast, anti-IFNγ mAb treated CCD mice recovered parasite specific IgG1 and showed a trend towards decreased IgG2c (Figure 1B). Similarly, while CCD mice displayed decreased serum IgE, anti-IFNγ mAb treatment restored this response (Figure 1C). Furthermore, histologic analysis of intestinal sections revealed that anti-IFNγ mAb treatment rescued the goblet cell mucin response in CCD mice (Figure 1D). Finally, anti-IFNγ mAb treatment restored the ability of CCD mice to expel parasites with kinetics comparable to infected CC control mice by 21 days post infection (Figure 1E). Collectively, these data demonstrate that Notch is not essential to initiate Th2 cell responses in vivo, and instead suggest that Notch functions to optimize the response.

Figure 1. Notch signaling is dispensable for Th2 initiation during Trichuris muris infection.

(A) At day 21, MLN from T. muris infected CC, CCD, and CCD + anti-IFNγ mice were stimulated with anti-CD3 for 72 hours and cytokine levels were measured by ELISA. (B) Serum T. muris specific IgG1 and IgG2c and (C) total IgE were measured by ELISA from infected mice, at day 21. (D) Goblet cells, dark staining, in gut sections were detected by mucin staining. (E) Cecal worm burdens at day 21 post-infection. *, P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM.

Persistent Notch signaling is required to maintain the Th1 and Th2 cell programs

To further test whether Notch is required to maintain an optimal Th2 cell response, we investigated the effect of inhibiting Notch subsequent to Th2 cell differentiation. For these studies, we developed an in vitro differentiation system in which Notch could be inhibited at different times by addition of a gamma secretase inhibitor (GSI) following activation of CD4+ T cells. This system also provided the opportunity to test the requirement for Notch in Th1 cell differentiation. Importantly, Notch inhibition by GSI did not affect T cell activation, proliferation, or cell numbers, even after prolonged exposure (Figure S1A–C), in contrast to a recent report (Helbig et al., 2012). To look at Notch specific effects and exclude autocrine cytokine effects, cells were cultured in the presence of neutralizing IL-4 and IFNγ antibodies.

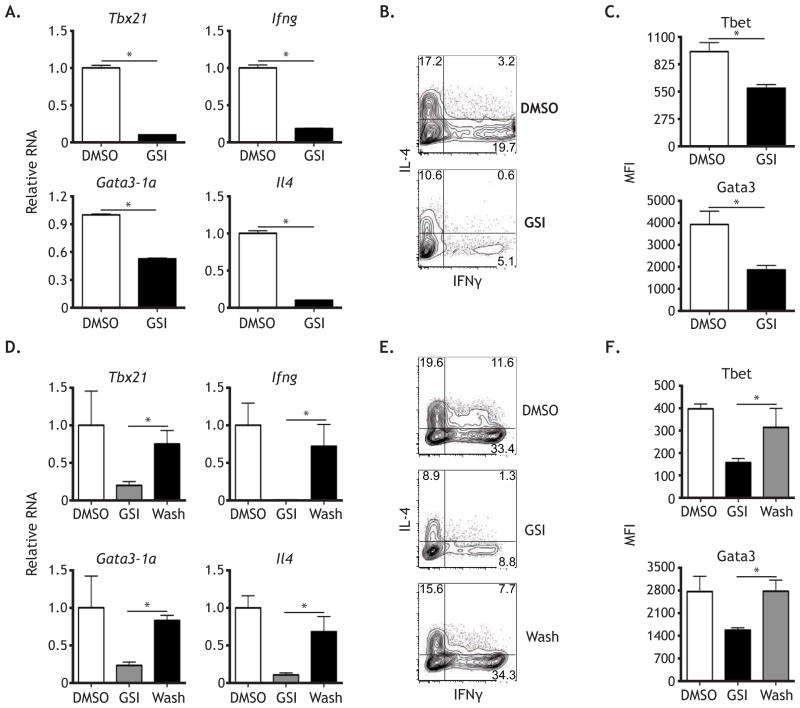

To test whether Notch was required post-initiation to maintain both the Th1 and Th2 cell programs, naïve CD4+ T cells were activated in the presence of irradiated splenocytes. After 5 days, cells were restimulated and treated with either DMSO or GSI and left in culture for an additional 2 days (day 7) before harvest. When looking at Th1 cell signature genes, both mRNA and protein for Tbet and IFNγ were significantly lower after 2 days of GSI treatment (Figure 2A–C). Similarly, GSI decreased mRNA and protein expression of the Th2 signature genes, Gata3 and Il4 (Figure 2A–C).

Figure 2. Persistent Notch signaling is required to maintain the Th1 and Th2 programs.

WT naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated with irradiated splenocytes, anti-CD3ε, and anti-CD28, and cultured under neutral conditions. After 5 days, cells were restimulated as above and replated in media containing either DMSO or 1 μM GSI. After 2 days (day 7 post-activation), (A) RNA was then harvested and analyzed by qPCR. Cells were analyzed for (B) cytokine production and (C) transcription factor expression by intracellular FACS. WT naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated and cultured as above for 5 days in media containing either DMSO or GSI. Cells were then washed and restimulated under the same conditions, with cells previously cultured in DMSO being replated in media containing DMSO and cells previously treated with GSI being replated in either DMSO or 1 μM GSI. After 2 days of restimulation, (D) RNA was then harvested and analyzed by qPCR. Cells were analyzed for (E) cytokine production and (F) transcription factor expression by intracellular FACS. *, P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. See also Figure S1.

While our data show that persistent Notch signaling is required to maintain the Th1 and Th2 cell programs post-initiation, it remained unclear whether the activity of Notch on Th1 and Th2 cell targets was restricted to early patterning events or if Notch was capable of re-activating target genes late after T cell stimulation. To address this, naïve CD4+ T cells were activated in the presence of either DMSO or GSI, under neutralizing conditions. After 5 days, cells were washed, restimulated, and returned to either DMSO or GSI to test whether cells previously treated with GSI could recover cytokine and transcription factor expression. While cells treated with GSI for all 7 days of culture showed impaired Tbet and IFNγ induction, cells treated with GSI only for the first round of stimulation recovered Tbet and IFNγ responses (Figure 2D–F). Similarly, IL-4 and GATA3 expression decreased when cells were treated with GSI for all 7 days and recovered when GSI was removed (Figure 2D–F). Our findings indicate that Notch is capable of promoting Th1 and Th2 signature gene expression both at early and late time points following stimulation and that inhibiting Notch at either the beginning of T cell stimulation or at later time points represses both Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation. Furthermore, we repeatedly observed that expression of both Th1 and Th2 cell program genes and proteins were suppressed in the same population upon Notch inhibition, suggesting that Notch concurrently regulates both programs. Collectively, these data show that Notch functions in Th cell differentiation do not require upstream signals from polarizing cytokines and demonstrate that the activity of Notch on its targets is not kinetically restricted.

Notch concurrently regulates both the Th1 and Th2 programs

Although both Th1 and Th2 cell signature genes were sensitive to GSI, it was important to show that the effects were Notch-specific as GSI has Notch-independent effects. Furthermore, Notch-independent, Presenilin-dependent effects on cytokine production were reported for both Th1 and Th2 cell types (Ong et al., 2008). To test whether the changes we observed were Notch-specific, we utilized mice containing two floxed alleles of dominant negative mastermind (DNMAMLFL/FL), a potent and specific GFP-tagged pan-Notch inhibitor.

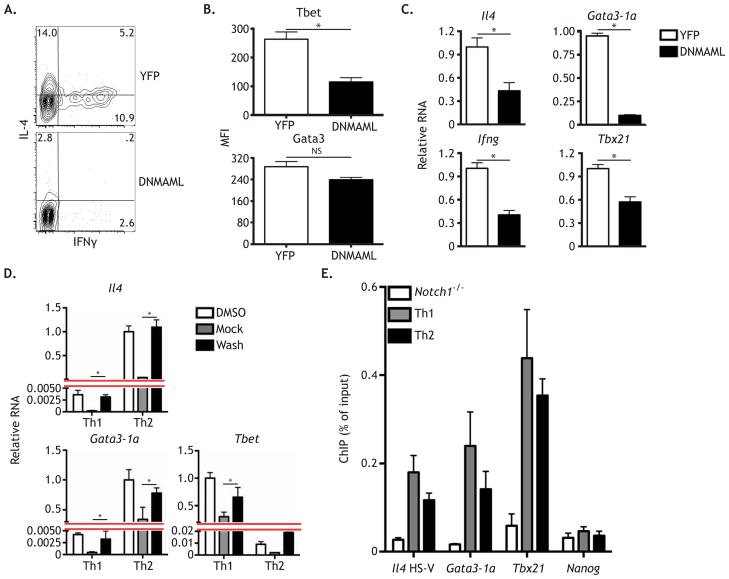

Tat-Cre treated YFPFL/FL and DNMAMLFL/FL naïve CD4+ T cells were stimulated under neutralizing conditions. Use of the Tat-Cre peptide to acutely induce DNMAML expression minimized potential compensation for Notch signaling by other pathways. As expected, YFP+ T cells produced IL-4 and IFNγ (Figure 3A). Consistent with observations using GSI treatment, DNMAML expressing T cells displayed a marked reduction in the fraction of cells that produced IL-4 and IFNγ confirming that Notch regulates both IL-4 and IFNγ production in the same cell population (Figure 3A). In contrast to the GSI data, analysis of Tbet and GATA3 protein in DNMAML expressing cells revealed reduced expression of Tbet, but not GATA3 (Figure 3B). Notch had been shown to regulate Tbx21 in a GSI-dependent manner and directly regulate Il4 via a 3′ enhancer; however, the GATA3 result was unexpected as Notch directly regulates Gata3 transcription by binding to the Gata3-1a promoter in primary CD4+ T cells (Amsen et al., 2007; Amsen et al., 2004; Fang et al., 2007; Minter et al., 2005). When transcripts for both Th1 and Th2 signature genes were analyzed by qPCR, all four (Il4, Gata3-1a, Ifng and Tbx21) were expressed at lower levels in DNMAML expressing cells (Figure 3C). The observed differences in GATA3 protein expression between GSI and DNMAML treatment were likely due to the finding that GSI suppressed transcripts from both Gata3-1a and Gata3-1b, whereas DNMAML only suppressed the Gata3-1a transcript, which accounts for a minor fraction of total Gata3 transcripts (Yu et al., 2009) (Figure S2A–B). These data indicate that Notch likely exerts its primary effect on the Th2 program through its regulation of Il4. It is important to note that while DNMAML expression had no impact on cell proliferation (Figure S2C), we did observe a minor increase in apoptosis as measured by Annexin-V (Figure S2D). While this subtle increase cannot account for the marked reduction in cytokine transcript and protein observed in DNMAML expressing cells, it suggests that a role for Notch signaling in cell survival may also contribute to these defects.

Figure 3. Notch concurrently regulates both the Th1 and Th2 programs.

YFPFL/FL or DNMAMLFL/FL CD4+ T cells were Tat-cre treated and rested for 24 hours in media containing 100 ng/mL IL-7. Naive CD4+ T cells were then FACS sorted and stimulated with irradiated splenocytes, anti-CD3ε, and anti-CD28, and cultured under neutral conditions. After 5 days, (A) cytokine production was measured by intracellular FACS, (B) Tbet and Gata3 protein was measured by intracellular FACS, and (C) RNA was analyzed by qPCR. WT CD4+ T cells were stimulated as above and cultured under either Th1 or Th2 culture conditions. After 24 hours, cells were treated with either DMSO or GSI for 20 hours. Subsequently, T cells were CD4+ MACS purified and cells cultured in DMSO were replated in DMSO and cells cultured in GSI were either replated in GSI (Mock) or in DMSO (Washout) for 4 hours; all cells were placed in media containing CHX. (D) RNA was then harvested and analyzed by qPCR. (E) WT CD4+ T cells were stimulated as above. After 2 days, cells were fixed and ChIP was performed using anti-Notch1 antibody, with Nanog serving as an internal negative control. As a negative control for the assay and antibody, anti-Notch1 ChIP was performed on CD4-Cre x Notch1FL/FL CD4+ T cells. *, P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. See also Figure S2, Table S1, and Table S2.

Our observation that both Th1 and Th2 cell signature genes were sensitive to Notch inhibition in the same population suggested that Notch does not instruct one program over the other, but instead acts as a global regulator. This raised the possibility that Notch could influence both Th1 and Th2 cell signature genes, even in strongly polarizing conditions. In order to assay direct Notch effects, we utilized the GSI-washout assay (Weng et al., 2006). Notch targets are identified as transcripts that demonstrate GSI sensitivity under mock wash conditions and recover upon washout in the presence of cycloheximide.

Naïve CD4+ T cells were activated as described and cultured under strong Th1 or Th2 cell polarizing conditions. As published, both Il4 and Gata3-1a behaved as direct Notch targets under Th2 cell polarizing conditions (Amsen et al., 2009; Amsen et al., 2004; Fang et al., 2007) (Figure 3D). Unexpectedly, both of these genes behaved as direct Notch targets under Th1 cell polarizing conditions, although the magnitude of their expression was greatly reduced, likely due to suppression by Th1 cell culture conditions (Figure 3D). Consistent with others (Minter et al., 2005), we identified Tbx21 as a direct Notch target in Th1 cell conditioned cells, but surprisingly also observed that Tbx21 behaved as a direct Notch target even under Th2 cell polarizing conditions (Figure 3D). To confirm the unbiased behavior of Notch under polarizing conditions, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays were performed. Consistent with GSI-washout results, Notch1 bound the previously reported Il4 HS-V, Gata3-1a, and Tbx21 Notch1 binding sites (Figure 3E). The magnitude of Notch binding was similar in both Th1 and Th2 cell polarizing conditions suggesting that the polarizing conditions do not bias Notch binding to these critical Th1 and Th2 cell targets. This is also show endogenous Notch1 binds Tbx21 in primary cells, confirming previous studies (Minter et al., 2005). Together with GSI-washout data, our ChIP findings confirm that Notch concurrently regulates both Th1 and Th2 programs, independent of cytokine signals.

Notch simultaneously orchestrates multiple Th cell programs by sensitizing cells to exogenous cytokine

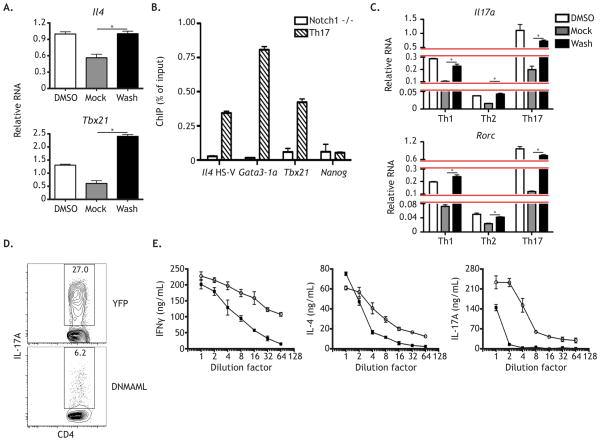

Having observed that Notch regulates both Th1 and Th2 cell programs, we hypothesized that Notch could regulate these targets in other Th cell populations, such as Th17 cells. To test this, naïve CD4+ T cells were activated as described, cultured under strong Th17 cell differentiating conditions, and subjected to the GSI-washout assay. Consistent with Th1 and Th2 cell observations, Il4 and Tbx21 both behaved as direct Notch targets in Th17 polarized cells (Figure 4A); Gata3-1a transcript was undetectable under these conditions (data not shown). To test if Notch1 binding was conserved between Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells, ChIP analysis was performed. In keeping with our GSI washout observations, Notch1 bound to the Il4, Gata3-1a, and Tbx21 loci in Th17 polarized cells, demonstrating that even though Gata3-1a was expressed at levels below the limit of detection, Notch still occupied this region. These data illustrate that the concurrent regulation of Th cell programs by Notch is not a unique feature of Th1 and Th2 cells, but rather a conserved function of Notch signaling in mature, activated CD4+ T cells.

Figure 4. Notch simultaneously orchestrates multiple Th cell programs.

WT CD4+ T cells were stimulated as described under Th17 culture conditions. (A) After 24 hours, cells were treated with either DMSO or GSI for 20 hours and then subjected to a GSI washout assay. Cells cultured in DMSO were replated in DMSO and cells cultured in GSI were either replated in GSI (Mock) or in DMSO (Washout) for 4 hrs. RNA was then harvested and analyzed by qPCR. (B) After 2 days, cells were fixed and ChIP was performed using anti-Notch1 antibody, with Nanog serving as an internal negative control. Anti-Notch1 ChIP was performed on CD4-Cre x Notch1FL/FL CD4+ T cells as an experimental and antibody negative control. (C) A GSI washout assay was performed as above on activated CD4+ T cells cultured under either Th1, Th2, or Th17 polarizing conditions. At the end of the assay (48 hrs), RNA was harvested and analyzed by qPCR. (D) Naive CD4+ T cells were FACS sorted from Tat-Cre treated YFPFL/FL or DNMAMLFL/FL CD4+ T cells. Cells were then stimulated as above, and cultured under Th17 conditions. After 3 days, cytokine production was measured by intracellular FACS. (E) WT CD4+ T cells were stimulated as described and then cultured in a titration series of two-fold serially diluted Th1 (left panel), Th2 (middle panel), or Th17 (right panel) conditioned media, in the presence of either DMSO or GSI. After 5 days, cells were restimulated and supernatants were analyzed by ELISA two days later. *, P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. See also Table S1 and Table S2.

To further demonstrate that Notch functions to regulate multiple cell programs from a common progenitor, we assayed whether the Th17 cell signature genes Il17a and Rorc behaved as direct Notch targets, regardless of the cytokine environment. Naïve CD4+ T cells were activated as described, cultured under Th1, Th2, or Th17 cell conditions, and subjected to the GSI washout assay. Although the expression varied by condition, Il17a and Rorc both behaved as direct Notch targets in all three Th cell types (Figure 4C).

To confirm that the observed effects on Th17 celll signature gene transcription were biologically significant, we expressed DNMAML in naïve CD4+ T cells using Tat-Cre, as described, and activated them under Th17 differentiating conditions. We observed at day 3 that DNMAML expression resulted in a marked reduction in the frequency of IL-17A producing cells (Figure 4D).

In light of reports showing that exogenous cytokine has the capacity to rescue cytokine production in Notch loss of function models (Amsen et al., 2004; Tu et al., 2005), we hypothesized that an important function of Notch was to sensitize CD4+ T cells to polarizing factors, especially when these factors may be limiting. To test this, CD4+ T cells were activated in the presence of serially diluted Th1, Th2, or Th17 polarizing cytokines, with media containing either DMSO or GSI. If Notch played a role in sensitizing cells to exogenous cytokine, we would predict that Notch inhibition would minimally affect differentiation at high levels of differentiating factors, but exert a negative effect on differentiation when exogenous cytokines were diluted. When cells were cultured in the presence of DMSO, secretion of IFNγ, IL-4, and IL-17A displayed an expected dose dependent response to polarizing cytokine, with maximal cytokine secretion observed in undiluted differentiating media (Figure 4E). Consistent with our hypothesis, when cells were cultured with GSI, cells displayed similar levels of cytokine secretion to DMSO control cells when differentiating cytokine was undiluted, but a much more rapid and marked decay in cytokine secretion when differentiating factors became limiting (Figure 4E). Altogether, these findings demonstrate that Notch simultaneously orchestrates multiple Th cell programs by sensitizing cells to exogenous differentiating factors.

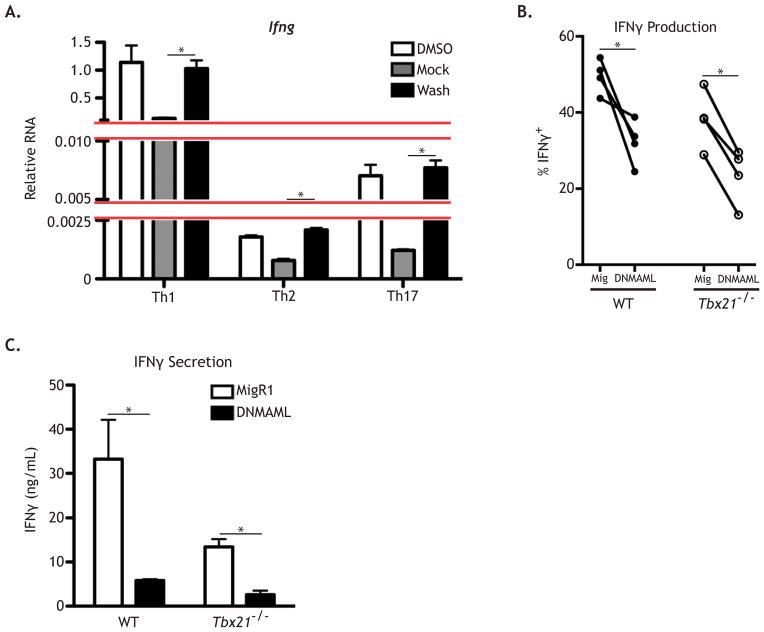

Notch directly regulates IFNγ expression, independently of Tbet

As Notch regulates a Gata3:Il4 axis in Th2 cells and an Il17a:Rorc axis in Th17 cells, we hypothesized that Notch might similarly regulate a Tbx21:Ifng axis in Th1 cells. To confirm that Ifng is a direct Notch target, we performed a GSI washout assay on cells cultured under strong Th1, Th2, and Th17 polarizing conditions. Similar to Gata3-1a, Il4, and Tbx21, Ifng behaved like a direct Notch target under all three culture conditions (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Notch directly regulates Ifng expression.

(A) WT CD4+ T cells were stimulated as described under either Th1, Th2, or Th17 culture conditions. 24 hours later, cells were treated with either DMSO or GSI for 20 hours and then subjected to a GSI washout assay. Cells cultured in DMSO were replated in DMSO and cells cultured in GSI were either replated in GSI (Mock) or in DMSO (Washout) for 4 hours. RNA was then harvested and analyzed by qPCR. WT and Tbet KO naive CD4+ T cells were stimulated as above and cultured with IL-12 (5 ng/mL), anti-IL-4 (20 μg/mL), and anti-IFNγ (20 μg/mL). After 24 hours, cells were retrovirally transduced with either vector control (Mig) or DNMAML. (B) Cytokine production was measured by intracellular FACS and (C) cytokine secretion by ELISA, 48 hours post-transduction. *, P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM.

To exclude the possibility that effects of Notch on Ifng resulted from indirect effects on Tbx21, we inhibited Notch signaling in Tbx21−/− cells. Naïve CD4+ T cells from WT and Tbx21−/− mice were activated and retrovirally transduced with vector control (MigR1) or DNMAML. To obtain sufficient IFNγ expression in Tbet deficient cells, cells were cultured in the presence of IL-12 and neutralizing anti-IFNγ and anti-IL-4 antibodies, conditions that allow Tbet-independent IFNγ production (Schulz et al., 2009; Usui et al., 2006) and exclude confounding paracrine effects between transduced and untransduced cells. Transduction of either WT or Tbx21−/− cells with DNMAML decreased the fraction of cells producing IFNγ as well as the total amount of IFNγ secreted (Figure 5B–C). Collectively, these data suggest that Notch directly regulates Ifng expression, independently of its role in regulating Tbx21, and identify Ifng as a Notch target.

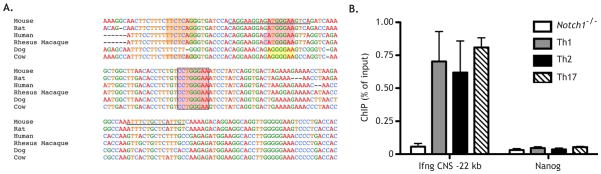

Notch1 binds to the Ifng CNS-22

To determine the mechanism by which Notch directly regulates Ifng, we searched for RBPJ binding sites in regions known to be critical for Ifng transcription (Hatton et al., 2006). Three RBPJ elements were identified in the Ifng CNS-22, a conserved enhancer that is required for Ifng expression in T and NK cells (Figure 6A) (Hatton et al., 2006). Primers were designed for ChIP that flanked the strongest and most conserved RBPJ binding site in the region. Two days after stimulation, CD4+ T cells exhibited Notch1 binding at the Ifng CNS-22 (Figure 6B). Similar to Il4, Gata3-1a, and Tbx21 (Figure 3F), Notch1 bound the Ifng CNS-22 site in Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Notch binds to the Ifng CNS-22.

(A) Multiple species alignment of the Ifng CNS-22 region, using NCBI DCODE.org. Highly conserved strong (red), moderate (orange), and weak (yellow) RBPJ binding sites are highlighted. Primer sequences used for ChIP are underlined. (B) WT CD4+ T cells were stimulated as described and cultured under Th1, Th2, or Th17 conditions. After 2 days cells were fixed and ChIP was performed using anti-Notch1 antibody, with Nanog serving as an internal negative control. Anti-Notch1 ChIP on CD4-Cre x Notch1FL/FL CD4+ T cells served as a negative control for the antibody and assay. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM.

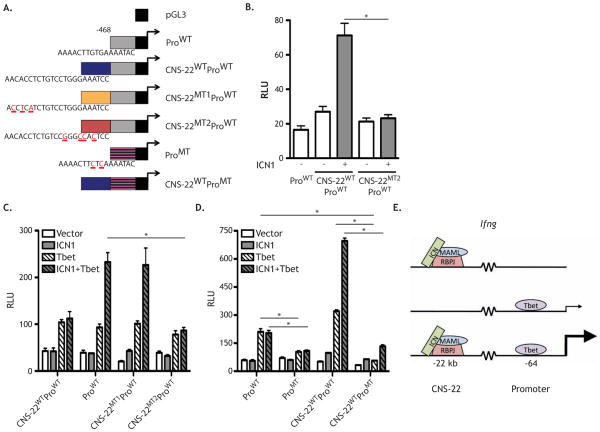

Notch1 and Tbet synergize to drive transcription from the Ifng CNS-22

The observation that Notch1 binds the Ifng CNS-22 suggested that Notch directly regulates Ifng expression through this element. To test this, we utilized reporter constructs for the Ifng CNS-22 region (Hatton et al., 2006). These constructs contain either the minimal 468 bp Ifng promoter (ProWT) or this promoter with the Ifng CNS-22 placed upstream (CNSWTProWT). Two putative T-box half-sites were identified in the Ifng CNS-22 fragment and mutant constructs were generated to both the upstream (CNSMT1ProWT) and downstream (CNSMT2ProWT) T-box half-sites (Figure 7A) (Hatton et al., 2006). Although the CNSMT2ProWT construct was originally described as a Tbet binding site mutant, this same mutation also ablates the most highly conserved RBPJ binding site in Ifng CNS-22. To test if Notch was capable of driving transcription through the Ifng CNS-22 at this site in cells capable of endogenous IFNγ production, activated Jurkat cells were transfected with vector control (pcDNA) or the constitutively active Notch1 intracellular domain ICN1 (Aster et al., 2000), as well as a reporter containing pGL3, ProWT, CNSWTProWT, or CNSMT2ProWT (Figure 7B). Addition of CNSWTProWT resulted in slightly increased reporter activity that was markedly enhanced upon the addition of ICN1, suggesting that Notch has the capacity to act on this enhancer element. When CNSMT2ProWT was used, the increased activity observed from the CNSWTProWT was lost and the addition of ICN1 failed to enhance reporter activity (Figure 7B). These data suggest that Notch1 is capable of enhancing transcription through the Ifng CNS-22.

Figure 7. Notch1 and Tbet synergize to drive transcription from the Ifng CNS-22.

(A) Schematic of the luciferase constructs used, as detailed in the methods. (B) 2 X 105 Jurkat cells were transfected with renilla control (pRLTK), either the ProWT, ProWTCNSWT, or ProWTCNSMT2 luciferase reporter constructs, and either a vector control or ICN1, using DMRIE-C liposomes. After 20 hours, cells were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin for 4 hours. Cells were then washed and luciferase activity was measured. (C) 2 X 104 U2OS cells were transfected with pRLTK, either the promoter ProWT, ProWTCNSWT, ProWTCNSMT1, or ProWTCNSMT2 reporter constructs, ICN1 or vector control, and Tbet or vector control. After 48 hours, luciferase activity was measured. (D) 2 X 104 U2OS cells were transfected with pRLTK, either the ProWT, ProMT, ProWTCNSWT, or ProMTCNSWT reporter constructs, ICN1 or vector control, and Tbet or vector control. After 48 hrs, luciferase activity was measured. (E) Proposed model of Ifng loci regulation by Notch1 and Tbet. All values are normalized to the pGL3 control construct. Relative luciferase units were calculated by normalizing firefly activity to renilla activity and setting all values relative to the pGL3 control construct. *, P < 0.05. Data are represented as mean +/− SEM.

Although the Jurkat cell data established that Notch1 can drive transcription from the Ifng CNS-22 in a mature T cell line, it remained possible that Notch1 indirectly enhanced luciferase activity by promoting Tbx21 transcription. In addition, the loss of luciferase activity observed when CNSMT2ProWT was expressed may have resulted from a loss of Tbet binding, rather than the loss of RBPJ binding at the same site. To test these alternate hypotheses, we utilized U2OS cells, which do not express endogenous Tbx21 and express very low amounts of Notch1 (data not shown). U2OS cells were transfected with the reporter constructs described above as well as CNSMT1ProWT, which ablates the upstream T-box half-site without disrupting the RBPJ binding site. Tbet overexpression in U2OS cells increased luciferase activity in all constructs (Figure 7C). This effect appeared primarily due to Tbet activity on the Ifng minimal promoter, as the addition of the Ifng CNS-22 and mutation of either T-box half-site had no additional effect on reporter activity (Figure 7C).

In contrast to Jurkat cells, ICN1 did not increase luciferase activity in U2OS cells, suggesting that other factors endogenous to Jurkat cells, such as Tbet, may be required to cooperate with Notch1 activity. Accordingly, co-expression of Tbet and ICN1 synergistically increased, luciferase activity from CNSWTProWT. Moreover, the enhanced luciferase activity was specific to CNSWTProWT and was not observed with ProWT, suggesting that the synergy between Notch1 and Tbet resulted from Notch1 activity at the Ifng CNS-22 (Figure 7C).

To directly address this possibility, we utilized the construct in which the upstream T-box half-site was mutated (CNSMT1ProWT). In cells expressing this reporter, luciferase activity was similar to the CNSWTProWT under all conditions, suggesting that the primary effect of Tbet was through its activity on the promoter. In contrast, when the conserved RBPJ binding site was mutated (CNSMT2ProWT), luciferase activity was comparable to the ProWT construct (Figure 7C). Collectively, these data suggest that ICN1 acts at the Ifng CNS-22 enhancer and Tbet acts at the Ifng promoter.

To directly assay the site of Tbet activity, we mutated the T-box site in the Ifng promoter leaving the putative Tbox sites in the CNS-22 intact (Tong et al., 2005) (Figure 7A). When U2OS cells were transfected with ProMT, neither Tbet alone nor Tbet plus ICN increased reporter activity to that observed in ProWT (Figure 7D). Moreover, mutation of the promoter in the context of CNS-22 (CNSWTProMT) ablated the ability of either Tbet alone or Tbet plus ICN1 to increase reporter activity (Fig 7D). Overall, these data demonstrate that binding of Notch at the Ifng CNS-22 is insufficient to activate transcription by itself and that Tbet binding at the promoter leads to weak activation; however, the combination of Notch binding to the CNS-22 and Tbet binding to the Ifng promoter leads to a synergistic increase in Ifng transcription (Figure 7E).

Discussion

Within the lymphoid compartment, Notch is understood to selectively promote one lineage outcome at the expense of alternate fates (Radtke et al., 2010). This instructive paradigm was proposed to explain Th cell differentiation, however, the emerging data are difficult to reconcile with this model as Notch promotes mutually exclusive cell fates from a multipotential cell (Amsen et al., 2004; Keerthivasan et al., 2011; Maekawa et al., 2003; Minter et al., 2005; Mukherjee et al., 2009; Tu et al., 2005). Here, we present data demonstrating that Notch acts as an unbiased amplifier of the Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell programs by sensitizing cells to environmental signals.

By acutely inhibiting Notch signaling under neutralizing conditions, we reveal a role for Notch in simultaneously orchestrating both Th1 and Th2 programs. GSI treatment and acute DNMAML expression synchronously reduced IL-4, IFNγ, and Tbet protein and mRNA for Il4, Ifng, Tbx21, and Gata3-1a, demonstrating that Notch lacks selectivity in regulating critical Th cell program targets. We further observed that Notch regulates Th17 target genes even when their expression is suppressed under Th1 and Th2 conditions and vice versa. Although the polarizing conditions influence the magnitude of gene expression, the ability of Notch to bind these key loci was unchanged, illustrating that the cytokine environment does not impact the ability of Notch to regulate its targets. Accordingly, our work suggests that Notch plays a critical role in reinforcing Th cell differentiation at physiologic levels of cytokine signaling, which would be important early during immune responses when differentiating cytokine cues are limiting. In addition, these findings help reconcile conflicting reports in the literature that emphasized the ability of Notch to preferentially regulate specific Th programs.

In related work, Ong et al. contended that Notch signaling itself had minimal impact on Th differentiation, but rather upstream cytokine signals directed Notch to selectivity enhance individual Th responses (Ong et al., 2008). Consistent with our findings, these studies argued that Notch lacks instructive capacity. Our T. muris studies provide the first in vivo loss-of-function data confirming that Notch is not required for instruction, however our GSI-washout and ChIP data provide a distinct mechanistic view of Notch function during Th differentiation. Rather than requiring cytokine signals to condition Notch selectivity, we find that Notch binds and regulates target loci without regard to cytokine signals. Moreover, we further show that Notch concurrently regulates Th cell programs even under neutralizing conditions. Thus, our work suggests that the activity of Notch is not dictated by cytokine signaling, but rather that Notch simultaneously facilitates transcription of multiple programs regardless of polarizing cues.

In addition to providing a unifying model for Notch in Th cell differentiation, we present definitive genetic loss-of-function and molecular data evincing a role for Notch in the Th1 program. Not only do our data demonstrate for the first time that endogenous Notch1 binds Tbx21 and that Tbx21 is a direct Notch target in primary CD4+ T cells, but we also show that Ifng is a novel, direct Notch target, independent of Notch’s role in regulating Tbx21. While the Notch effects on Ifng are independent of its activity on Tbx21, Notch does not appear capable of driving Ifng transcription by itself, consistent with a model in which Notch lacks the capacity to instruct Th differentiation. Both factors are needed for optimal Ifng expression, where they bind different regulatory elements. Moreover, the Tbx21−/− studies suggest that Notch is capable of collaborating with factors other than Tbet, as DNMAML suppressed Ifng expression in its absence. The original report using these luciferase constructs found that Tbet overexpression was capable of enhancing luciferase activity of the WT CNS-22 construct when cells were stimulated with PMA and ionomycin (Hatton et al., 2006), which also induces NFκB binding to the Ifng CNS-22 (Balasubramani et al., 2010). As the Ifng CNS-22 contains multiple regulatory motifs, these data suggest that Tbet activity at the Ifng promoter synergizes with multiple factors regulating the Ifng CNS-22, including Notch and NFκB. Altogether, these data illustrate the dynamism of the Ifng promoter and CNS-22 and demonstrate how these elements have the potential to integrate inputs from multiple pathways.

The results of our reporter assays are reminiscent of the synergy between Gata3 and Notch1 at the Il4 locus and suggest that Notch and cytokine signaling collaborate in both Th1 and Th2 differentiation (Fang et al., 2007). Furthermore, Notch appears to participate in a feed-forward loop, promoting Tbx21 transcription and in turn synergizing with Tbet protein to enhance Ifng transcription. Work by Flavell and colleagues suggests that this Th1 feed-forward loop must be stabilized by other factors (Amsen et al., 2007). In their study, constitutive Notch signaling was insufficient to enforce Th1 differentiation in the presence of endogenous Gata3, demonstrating that low levels of Gata3 act as a failsafe against runaway Th1 differentiation in response to Notch activation. In addition to transcriptional regulation, Notch can regulate IFNγ secretion in an RBPJ-independent manner, suggesting that Notch regulates the CD4+ T cell IFNγ response at multiple, mechanistically distinct levels (Auderset et al., 2012). Additionally, a recent human T cell study implicated a role for Notch in Th1 differentiation (Le Friec et al., 2012). Together, these data firmly establish Notch as a key regulator of the Th1 program.

As well as revealing a definitive role for Notch in promoting Th1 differentiation, our data further clarify the mechanism by which Notch regulates Th2 differentiation. The findings from anti-IFNγ mAb treated T muris infected CCD mice indicate that the role of Notch during in vivo Th2 inflammation is similar to what has been reported for NFκB2, IL-25, and TSLP (Artis et al., 2002; Owyang et al., 2006; Taylor et al., 2009). Like Notch, mice deficient for each of these factors displayed susceptibility to helminth infection and impaired Th2 immune responses, however blockade of Th1 responses in these mouse models resulted in restoration of the Th2 response and worm expulsion. Moreover, unlike the role for Notch in regulating Th1 differentiation, we observe a major role for Notch in promoting IL-4 production but minimal impact on total Gata3, suggesting that additional factors, such the Notch target Tcf1, may be required to fully engage the Th2 program (Yu et al., 2009). These studies collectively illustrate a clear distinction between Th2 initiating factors, such as NFκB1 (Artis et al., 2002), and the multiple inputs that maintain an optimal Th2 response in vivo, but are dispensable for Th2 program initiation, such as Notch.

In addition to regulating Notch-dependent IL-4 production in Th2 cells, recent work demonstrated that the IL-4 HS-V region is critical for T follicular helper cell (Tfh) production of IL-4 (Harada et al., 2012; Vijayanand et al., 2012). These findings raise the possibility that Notch inhibition in the T. muris studies may impact both Th2 and Tfh subsets during infection and the combined effects on these two populations contribute to the phenotype observed. Importantly, anti-IFNγ treatment restored productive immunity against helminth infection; and therefore, the role that Notch signaling plays in Tfh biology is either redundant with its function in Th2 cells or not essential for Tfh differentiation, similar to what we observe for Th1, Th2, and Th17 subsets.

With the recent recognition of Th cell plasticity, particularly at early time points, our data suggest that Notch functions to ensure that activated CD4+ T cells overcome a Th cell commitment threshold (Murphy and Stockinger). In this manner, Notch tunes the responsiveness of an activated CD4+ T cell to a specific Th cell program by sensitizing cells to limiting environmental differentiation cues. Thus, depending on the inflammatory environment for a given immune response, the requirement for Notch will vary depending on whether the strength of the differentiating signals a T cell receives are sufficient to achieve a signaling threshold for Th cell commitment. For example, during T. muris infection, our model argues that Notch sensitizes T cells to limiting Th2 differentiating cues, while residual IFNγ signals destabilize the Th2 circuitry when Notch signaling is abrogated. This model would also explain why Th1 differentiation occurs independently of Notch during Leishmania infection, as we would predict that the environmental differentiating signals are sufficient to overcome a commitment threshold (Amsen et al., 2004; Tu et al., 2005). Alternatively, in the context of GvHD, which is characterized by a mixed Th cell response, Notch is required to sensitize cells to subthreshold signals and achieve optimal IFNγ production (Zhang et al., 2011). While our data favor a model in which Notch regulates Th differentiation by sensitizing cells to their environment, Notch likely plays additional roles in other aspects of Th biology, such as survival and metabolism, that warrant future study.

Overall, these findings offer a paradigm for Notch in the immune system. In addition to its roles as an arbiter of alternate fate decisions and a key regulator of cell survival, proliferation, and metabolism, we reveal that Notch also acts to potentiate multiple fates from a single progenitor. Not only does this paradigm reconcile previously conflicting studies, but it also suggests that manipulating the amounts of Notch signaling in Th cell mediated pathologies may have therapeutic benefit.

Experimental Procedures

Mice

ROSA26-DNMAML mice were previously described (Tu et al., 2005). C57Bl/6 mice were obtained from the National Cancer Institute (Frederick, MD). YFP mice were obtained from Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, ME). Tbx21−/− mice were provided by John Wherry. All mice were housed in specific pathogen-free facilities at the University of Pennsylvania. Experiments were performed according to the guidelines from the National Institutes of Health with approved protocols from the University of Pennsylvania Animal Care and Use Committee.

TAT-Cre

Expression of TAT-cre was induced with IPTG in bacteria during log phase of growth at 37 ºC in the presence of chloramphenicol and carbenicillin. The Children’s Hospital of Pennsylvania Protein Core carried out purification of TAT-Cre protein. 107 CD4+ T cells from DNMAMLFL/FL or YFPFL/FL mice were MACS purified by positive selection with CD4 Microbeads (Miltenyi). Subsequently, cells were washed, resuspended in 1 ml serum-free OPTI-MEM (Life Technologies), and incubated with 1 ml of 100 mg/ml of TAT-Cre in OPTI-MEM for 12 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed and cultured in IMDM (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 50 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, and 100ng/mL IL-7. Twenty-four hours later, naïve YFP+ or GFP+ CD4+ T cells were FACS sorted

Quantitative PCR

RNA was extracted using the QIAGEN RNeasy Mini Kit. cDNA was synthesized from RNA with the Superscript II kit (Invitrogen). Transcripts were amplified with Sybr Green PCR Master Mix (ABI) and quantitative PCR was performed on an ABI ViiA 7 Real-Time PCR System. (Primers, Table S1)

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assays

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was performed as described previously (Yashiro-Ohtani et al., 2009). Briefly, chromatin samples were prepared from fixed 6 million cells and immunoprecipitated with rabbit immunoglobulin G (#sc-3888; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) or anti-Notch1 antibodies (Aster et al., 2000). Purified DNA was subjected to real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with primers flanking RBPJ binding sites at Gata3-1a, Il4 HS-V, IFNg CNS-22, or Tbx21 promoter (primers, Table S2). CD4+ T cells from Notch1 null mice were used for an immunoprecipitation negative control. Nanog was used as an internal negative control. The DNA quantity recovered from each ChIP sample is shown as the relative value to the DNA input sample. Supplementary Table 1 lists primer sequences.

Luciferase assay

Ifng luciferase constructs are described (Hatton et al., 2006). Constructs included a reporter control (pGL3), the reporter plus a 468 bp Ifng minimal promoter (ProWT), the minimal promoter construct containing a mutated T-box binding site (ProMT), the minimal promoter construct with a WT Ifng CSN-22 upstream (ProWTCNSWT), the WT CNS-22 construct containing a mutated T-box binding site in the promoter region (ProMTCNSWT), the Ifng CNS-22 construct with the upstream CNS-22 T-box half-site mutated (ProWTCNSMT1), and the Ifng CNS-22 construct with the downstream CNS-22 T-box half-site mutated (ProWTCNSMT1). Point mutations to T-box binding sites in the Ifng promoter were made using the Promega QuikChange Site Directed Mutagenesis Kit. Constructs were sequenced to prove authenticity. 2 X 105 Jurkat cells were plated in triplicate and transfected with 50 ng of the indicated promoter/reporter constructs, 25 ng pRL-TK, and 100 ng pcDNA-ICN1 or vector control using DMRIE-C (Invitrogen). Transfected cells were cultured overnight and then stimulated for 4 hours with 20 ng/mL PMA and 200 ng/mL ionomycin. 2 × 104 U2OS cells were plated in triplicate and transfected with 50 ng of the indicated promoter/reporter constructs, 10 ng pRL-TK, 10 ng pcDNA-ICN1 or vector control, and 25 ng Mig-Tbet or vector control using FuGENE 6 (Promega). After stimulation, firefly substrate activity was measured using Britelite Plus (PerkinElmer) and renilla substrate activity measured using Stop & Glo (Promega). Firefly values were normalized to Renilla and then all normalized values set relative to the pGL3 control vector. All measurements were performed using a GloMax-96 Microplate Luminometer (Promega).

In vitro T cell culture

Lymph nodes from WT mice were CD4+ MACS purified and then naïve CD4+ T cells were FACS sorted. Naïve CD4+ T cells were co-cultured with irradiated, Thy1.2 depleted splenocytes at a 1:5 ratio and stimulated using anti-CD3e (1 μg/mL), and anti-CD28 (1 μg/mL) mAb. Cells were cultured under either neutral (5 ng/mL IL-2, 20 μg/mL anti-IL-4, and 20 μg/mL anti-IFNγ), Th1 (5 ng/mL IL-2, 5 ng/mL IL-12, and 20 μg/mL anti-IL-4), Th2 (20 ng/mL IL-4, 20 μg/mL anti-IFNg, and 20 μg/mL anti-IL-12), or Th17 (20 ng/mL IL-6 and 5ng/mL TGF-β) culture conditions. For GSI experiments, cells were treated with either DMSO or 1 μM GSI.

Measurement of cytokines

For intracellular cytokine staining, cells were restimulated, fixed, and stained as described (Tu et al., 2005). Cells were stained with anti-CD4 (RM4-5, Biolegend), anti-IFNγ (XMG1.2, BD), anti-IL4 (11B11, eBioscience), anti-IL17A (ebio17B7, eBioscience), anti-Tbet (eBio4B10, eBioscience), and anti-GATA3 (L50-823, BD). Cells were acquired on a LSRII (Becton Dickenson) and data was analyzed with FlowJo (TreeStar). ELISA was performed as described (Tu et al., 2005).

GSI-washout assay

WT CD4+ T cells were stimulated as above and 24 hours post-stimulation cells were treated with either DMSO or GSI (1 μM) for 20 hours. Subsequently, T cells were CD4+ MACS purified and cells cultured in media containing cycloheximide (20 μg/mL) and cells previously cultured DMSO were replated in DMSO and cells cultured in GSI were either replated in 1 μM GSI or in DMSO for 4 hours. RNA was then harvested and analyzed by qPCR.

T muris infection and antigen

T. muris eggs were prepared as described (Tu et al., 2005). Mice were infected on day 0 with 150–200 embryonated eggs, and parasite burdens were assessed on day 21 after infection. Mesenteric LN (MLN) cell suspensions were prepared and resuspended in IMDM supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FBS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 g/ml streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, and 50 M 2-mercaptoethanol. Cells were plated at 4 X 106 cells/well and cultured in the presence of anti-CD3e and anti-CD28 for 72 hours. Levels of IL-4, -5, and -13 were assayed by sandwich ELISA. For histology, segments of mid-cecum were removed, washed in sterile PBS, and fixed for 24 hours in paraformaldehyde. Tissues were processed and paraffin embedded using standard histological techniques. For detection of intestinal goblet cells, 5 μm sections were cut and stained with hematoxylin and eosin or Alcian blue periodic acid Schiff. Analysis of parasite- specific IgG1 and IgG2c production was performed by antigen capture

Statistical Analysis

Significance was determined using a Student’s T-test. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Notch concurrently regulates Th1, Th2, and Th17 cell differentiation

Notch activity is unbiased and is not affected by the cytokine environment

Notch regulates Ifng at the Ifng CNS-22 and synergizes with Tbet at the promoter

Notch can simultaneously orchestrate multiple lineage programs

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Avinash Bhandoola and John Wherry for providing advice and/or reagents. The following cores at the University of Pennsylvania contributed to this study: mouse husbandry (ULAR), the Abramson Cancer Center Flow Cytometry Core (P30-CA016520), the AFCRI Cores, the Matthew J. Ryan Veterinary Hospital Pathology Lab, and the NIH/NIDDK P30 Center for Molecular Studies in Digestive and Liver Diseases (P30-DK050306). This work was supported by T32HD007516 and 1F31CA165813 predoctoral fellowships to W.B., a predoctoral fellowship from the Cancer Research Institute to T.C.F, and grants from the National Institutes of Health to WSP (R01AI047833) and R.D.H. and C.T.W. (R01AI077574). D.A. is a Burroughs Wellcome Fund Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Disease.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Amsen D, Antov A, Flavell RA. The different faces of Notch in T-helper-cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:116–124. doi: 10.1038/nri2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsen D, Antov A, Jankovic D, Sher A, Radtke F, Souabni A, Busslinger M, McCright B, Gridley T, Flavell RA. Direct regulation of Gata3 expression determines the T helper differentiation potential of Notch. Immunity. 2007;27:89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amsen D, Blander JM, Lee GR, Tanigaki K, Honjo T, Flavell RA. Instruction of distinct CD4 T helper cell fates by different notch ligands on antigen-presenting cells. Cell. 2004;117:515–526. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00451-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artis D, Shapira S, Mason N, Speirs KM, Goldschmidt M, Caamano J, Liou HC, Hunter CA, Scott P. Differential requirement for NF-kappa B family members in control of helminth infection and intestinal inflammation. J Immunol. 2002;169:4481–4487. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.8.4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aster JC, Xu L, Karnell FG, Patriub V, Pui JC, Pear WS. Essential roles for ankyrin repeat and transactivation domains in induction of T-cell leukemia by notch1. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:7505–7515. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.20.7505-7515.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auderset F, Schuster S, Coutaz M, Koch U, Desgranges F, Merck E, MacDonald HR, Radtke F, Tacchini-Cottier F. Redundant Notch1 and Notch2 signaling is necessary for IFNgamma secretion by T helper 1 cells during infection with Leishmania major. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002560. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balasubramani A, Shibata Y, Crawford GE, Baldwin AS, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. Modular utilization of distal cis-regulatory elements controls Ifng gene expression in T cells activated by distinct stimuli. Immunity. 2010;33:35–47. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackwell NM, Else KJ. B cells and antibodies are required for resistance to the parasitic gastrointestinal nematode Trichuris muris. Infect Immun. 2001;69:3860–3868. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.6.3860-3868.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannons JL, Lu KT, Schwartzberg PL. T follicular helper cell diversity and plasticity. Trends Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.it.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliffe LJ, Grencis RK. The Trichuris muris system: a paradigm of resistance and susceptibility to intestinal nematode infection. Adv Parasitol. 2004;57:255–307. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(04)57004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cliffe LJ, Humphreys NE, Lane TE, Potten CS, Booth C, Grencis RK. Accelerated intestinal epithelial cell turnover: a new mechanism of parasite expulsion. Science. 2005;308:1463–1465. doi: 10.1126/science.1108661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coghill JM, Sarantopoulos S, Moran TP, Murphy WJ, Blazar BR, Serody JS. Effector CD4+ T cells, the cytokines they generate, and GVHD: something old and something new. Blood. 2011;117:3268–3276. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-12-290403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Else KJ, Finkelman FD, Maliszewski CR, Grencis RK. Cytokine-mediated regulation of chronic intestinal helminth infection. J Exp Med. 1994;179:347–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang TC, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Del Bianco C, Knoblock DM, Blacklow SC, Pear WS. Notch directly regulates Gata3 expression during T helper 2 cell differentiation. Immunity. 2007;27:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harada Y, Tanaka S, Motomura Y, Ohno S, Yanagi Y, Inoue H, Kubo M. The 3′ enhancer CNS2 is a critical regulator of interleukin-4-mediated humoral immunity in follicular helper T cells. Immunity. 2012;36:188–200. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatton RD, Harrington LE, Luther RJ, Wakefield T, Janowski KM, Oliver JR, Lallone RL, Murphy KM, Weaver CT. A distal conserved sequence element controls Ifng gene expression by T cells and NK cells. Immunity. 2006;25:717–729. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helbig C, Gentek R, Backer RA, de Souza Y, Derks IA, Eldering E, Wagner K, Jankovic D, Gridley T, Moerland PD, et al. Notch controls the magnitude of T helper cell responses by promoting cellular longevity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9041–9046. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206044109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keerthivasan S, Suleiman R, Lawlor R, Roderick J, Bates T, Minter L, Anguita J, Juncadella I, Nickoloff BJ, Le Poole IC, et al. Notch signaling regulates mouse and human Th17 differentiation. J Immunol. 2011;187:692–701. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopan R, Ilagan MX. The canonical Notch signaling pathway: unfolding the activation mechanism. Cell. 2009;137:216–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubo M. Notch: filling a hole in T helper 2 cell differentiation. Immunity. 2007;27:3–5. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Friec G, Sheppard D, Whiteman P, Karsten CM, Shamoun SA, Laing A, Bugeon L, Dallman MJ, Melchionna T, Chillakuri C, et al. The CD46-Jagged1 interaction is critical for human T(H)1 immunity. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:1213–1221. doi: 10.1038/ni.2454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maekawa Y, Tsukumo S, Chiba S, Hirai H, Hayashi Y, Okada H, Kishihara K, Yasutomo K. Delta1-Notch3 interactions bias the functional differentiation of activated CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 2003;19:549–559. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00270-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minter LM, Turley DM, Das P, Shin HM, Joshi I, Lawlor RG, Cho OH, Palaga T, Gottipati S, Telfer JC, et al. Inhibitors of gamma-secretase block in vivo and in vitro T helper type 1 polarization by preventing Notch upregulation of Tbx21. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:680–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Schaller MA, Neupane R, Kunkel SL, Lukacs NW. Regulation of T cell activation by Notch ligand, DLL4, promotes IL-17 production and Rorc activation. J Immunol. 2009;182:7381–7388. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy KM, Stockinger B. Effector T cell plasticity: flexibility in the face of changing circumstances. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:674–680. doi: 10.1038/ni.1899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto M, Matsuda H, Joetham A, Lucas JJ, Domenico J, Yasutomo K, Takeda K, Gelfand EW. Jagged1 on dendritic cells and Notch on CD4+ T cells initiate lung allergic responsiveness by inducing IL-4 production. J Immunol. 2009;183:2995–3003. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong CT, Sedy JR, Murphy KM, Kopan R. Notch and presenilin regulate cellular expansion and cytokine secretion but cannot instruct Th1/Th2 fate acquisition. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2823. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owyang AM, Zaph C, Wilson EH, Guild KJ, McClanahan T, Miller HR, Cua DJ, Goldschmidt M, Hunter CA, Kastelein RA, Artis D. Interleukin 25 regulates type 2 cytokine-dependent immunity and limits chronic inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. J Exp Med. 2006;203:843–849. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radtke F, Fasnacht N, Macdonald HR. Notch signaling in the immune system. Immunity. 2010;32:14–27. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz EG, Mariani L, Radbruch A, Hofer T. Sequential polarization and imprinting of type 1 T helper lymphocytes by interferon-gamma and interleukin-12. Immunity. 2009;30:673–683. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skokos D, Nussenzweig MC. CD8- DCs induce IL-12-independent Th1 differentiation through Delta 4 Notch-like ligand in response to bacterial LPS. J Exp Med. 2007;204:1525–1531. doi: 10.1084/jem.20062305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor BC, Zaph C, Troy AE, Du Y, Guild KJ, Comeau MR, Artis D. TSLP regulates intestinal immunity and inflammation in mouse models of helminth infection and colitis. J Exp Med. 2009;206:655–667. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y, Aune T, Boothby M. T-bet antagonizes mSin3a recruitment and transactivates a fully methylated IFN-gamma promoter via a conserved T-box half-site. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2034–2039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409510102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu L, Fang TC, Artis D, Shestova O, Pross SE, Maillard I, Pear WS. Notch signaling is an important regulator of type 2 immunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202:1037–1042. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Usui T, Preiss JC, Kanno Y, Yao ZJ, Bream JH, O’Shea JJ, Strober W. T-bet regulates Th1 responses through essential effects on GATA-3 function rather than on IFNG gene acetylation and transcription. J Exp Med. 2006;203:755–766. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vijayanand P, Seumois G, Simpson LJ, Abdul-Wajid S, Baumjohann D, Panduro M, Huang X, Interlandi J, Djuretic IM, Brown DR, et al. Interleukin-4 production by follicular helper T cells requires the conserved Il4 enhancer hypersensitivity site V. Immunity. 2012;36:175–187. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng AP, Millholland JM, Yashiro-Ohtani Y, Arcangeli ML, Lau A, Wai C, Del Bianco C, Rodriguez CG, Sai H, Tobias J, et al. c-Myc is an important direct target of Notch1 in T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia/lymphoma. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2096–2109. doi: 10.1101/gad.1450406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yashiro-Ohtani Y, He Y, Ohtani T, Jones ME, Shestova O, Xu L, Fang TC, Chiang MY, Intlekofer AM, Blacklow SC, et al. Pre-TCR signaling inactivates Notch1 transcription by antagonizing E2A. Genes Dev. 2009;23:1665–1676. doi: 10.1101/gad.1793709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Q, Sharma A, Oh SY, Moon HG, Hossain MZ, Salay TM, Leeds KE, Du H, Wu B, Waterman ML, et al. T cell factor 1 initiates the T helper type 2 fate by inducing the transcription factor GATA-3 and repressing interferon-gamma. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:992–999. doi: 10.1038/ni.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Sandy AR, Wang J, Radojcic V, Shan GT, Tran IT, Friedman A, Kato K, He S, Cui S, et al. Notch signaling is a critical regulator of allogeneic CD4+ T-cell responses mediating graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2011;117:299–308. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-271940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.