Abstract

The discordance between fertility intentions and outcomes may be associated with mental health in the general population. This requires data directly linking individuals’ fertility intentions with their outcomes. This study brings together two streams of research on fertility and psychological distress to examine whether unintended childlessness and unplanned births are associated with psychological distress, compared with intended childlessness and planned births. We also examine whether unintended childlessness and unplanned births are differently associated with distress at two stages of the individuals’ life course: in early and late 30s. As women are more directly affected by the decline in fertility with age and the experience of motherhood is more central to women’s identity, we also examined gender differences in these associations. Thus, we examined the association between four possible fertility events (planned and unplanned births, intended and unintended childlessness) and psychological distress of men and women, at two different stages over the life course (early and late 30s). We used longitudinal data from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1979 (NLSY79, N = 2524) to link individuals’ fertility intentions and outcomes to evaluate the association of depressive symptoms (CES-D) with four possible fertility events occurring in two-year intervals, for men and women separately. Contrary to our first hypothesis, unintended childlessness and unplanned births were not associated with psychological distress for women. Among men, only unplanned births in their early 30s were associated with increases in psychological distress. We did not find support for our second hypothesis that unintended childlessness and unplanned births have a different association with psychological distress for men and women and as a function of the stage of life. These findings are discussed in the context of previous literature in this area.

Keywords: fertility, intentions, depressive symptoms, gender, life course, USA

Introduction

Given recent trends of delayed childbearing and increased childlessness, the relation of unintended infertility to couples’ mental health has been the focus of many psychological and epidemiological studies (Greil, 1997). In contrast, couples at the other end of the intentions-outcome discordance spectrum who exceed their fertility intentions have received much less attention in recent years, despite the fact that they represent up to a quarter of American men and women (Heaton, Jacobson, & Holland, 1999; Quesnel-Vallee & Morgan, 2003). Moreover, while unintended childlessness and unplanned births have both been independently associated with poor mental health, the distress associated with these fertility events has not been previously compared.

In this paper, we argue that these two processes should be studied in conjunction because their conceptual similarities can increase our understanding of the mechanisms by which they can affect mental health. Indeed, they are located in one of four quadrants formed by two intersecting continuums: the childlessness-birth continuum and the fertility intention continuum. The relationship of both unintended childlessness and unplanned births to mental health can also be interpreted through the stressful life events framework, according to which psychological distress is rooted in social causes and is a consequence of undesirable life events (Dohrenwend & Dohrenwend, 1981; Rabkin & Struening, 1976).

These two lines of research share more than conceptual underpinnings as they both have suffered from similar methodological limitations. Indeed, both have been limited to varying degrees by an over-reliance on convenience, clinic-based samples, or cross-sectional data, and a failure to take into account the life course nature of fertility events (Greil, 1997). This is problematic because the distress that results from fertility events may depend on life course dynamics (Beets, Liefbroer, & Gierveld, 1999; Pearlin & Skaff, 1996). We could expect, for instance, that unintended childlessness in later adulthood is associated with more distress than earlier in the life course. Furthermore, a life course perspective also highlights a potential for gender differences in the response to undesirable fertility events (unintended childlessness and unplanned births).

The association of psychological distress and discordance between fertility intentions and outcomes in the general population cannot be meaningfully assessed without prospectively linking individuals’ fertility intentions with later outcomes. With the use of longitudinal data from the National Longitudinal Study of Youth 1979 (NLSY79), we link individuals’ fertility intentions and outcomes to evaluate the association between depressive symptoms and four possible fertility events (planned and unplanned births, and intended and unintended childlessness) occurring in two-year intervals at two different stages of the life course (early and late 30s), for men and women separately. Because previous studies have shown that the level of distress is most pronounced among childless individuals unable to achieve parenthood (Benyamini, Gozlan, & Kokia, 2005; McQuillan, Greil, White, & Jacob, 2003), we chose to limit our analyses to nulliparous individuals in early and late 30s.1

Infertility and Unintended Childlessness

As a growing number of American adults delay their childbearing, they may be forced to revise their fertility intentions downwards, either voluntarily or involuntarily (Hagewen & Morgan, 2005). The proportion of US women aged 15–44 who reported some form of fecundity impairment rose from 8% in 1982 to 10% in 1995 (Chandra & Stephen, 1998) and the lifetime prevalence of infertility in industrialized nations is estimated at 17–26% (Schmidt, 2006). Overall, the levels of childlessness increased among cohorts born in the latter part of the 20th century and reached as high as 30% in some areas of the United States (Morgan, 1991). In light of these trends, researchers have attempted to understand the relationship of infertility to mental health.2

One of the mechanisms that has been shown to affect mental health in other contexts is a perception of a loss of control, which occurs when individuals with poor internal coping resources feel helpless and uncertain about the future, and not in control of their lives (Mirowsky & Ross, 1989, 2003; Pearlin, Menaghan, Lieberman, & Mullan, 1981). One proposed mechanism for psychological distress is through stress that ensues when individuals are unable to achieve or maintain a valued identity despite their efforts (McQuillan et al., 2003). Indeed, chronic stress measures include ‘inability to have the desired number of children’ as a scale item (Turner, Wheaton, & Lloyd, 1995). Moreover, the level of distress is said to depend on the magnitude or the severity of deviation from the desired outcome (Benyamini et al., 2005; McQuillan et al., 2003). Stress levels are found to differ substantially for infertile women who are childless compared to infertile women with one, and two or more children (i.e., subfertile women) (Benyamini et al., 2005; McQuillan et al., 2003). Therefore, infertile childless women who experienced unintended childlessness are at the greatest risk of psychological distress, compared with subfertile women who have children or those who are childless by choice (intended childlessness), suggesting that continued inability to achieve motherhood undermines a valued identity (Benyamini et al., 2005; McQuillan et al., 2003; Miall, 1986; Turner et al., 1995). While this may also be true for men, few studies have examined this possibility (but see White & McQuillan, 2006). Indeed, although the negative attitudes toward voluntary childlessness are changing (Park, 2005; Veevers, 1977) and the number of those who voluntarily choose to remain childless is also apparently growing (Heaton et al., 1999; Morgan, 1991), the social context that conditions the experience of childlessness for American women still includes the “motherhood mandate”, the socially constructed expectation that having children is central to a woman’s identity (Koropeckyj-Cox & Pendell, 2007; Russo, 1976).

Previous reviews of infertility and mental health (Greil, 1997; Wright, Allard, Lecours, & Sabourin, 1989) provide convincing evidence that patients in fertility clinics have higher levels of psychological distress than control groups. However, these studies are based predominantly on clinical populations. Two recent studies have overcome this limitation by assessing the relationship of subfecundity and infertility to mental health in representative population samples (King, 2003; McQuillan et al., 2003). However, they faced the challenge of prospectively measuring explicit fertility intentions. McQuillan and colleagues (2003) relied on an implicit measure of fertility intentions and King (2003) tested the moderating effect of the ‘desire for a child’. None of the previous studies focusing on the relations of unintended childlessness or infertility with mental health prospectively linked fertility intentions with later outcomes because of their reliance on retrospective and cross-sectional data. Thus, clinical and general population samples have so far been unable to disentangle whether individuals’ psychological distress is due to the experience of infertility or fertility treatments themselves, or whether stated intentions (and mental health) are in fact the consequence of subfecundity (Greil, 1997; King, 2003). The cross-sectional nature of the data also meant that life course variations could not be assessed (Greil, 1997). Finally, there has been no replication using population samples of the clinical finding that women are at a higher risk of distress than men (Greil, 1997; Jordan & Revenson, 1999; Wright, Bissonnette, Duchesne, Benoit, Sabourin, & Girard, 1991). If this gender difference is due to the fertility treatment itself that women undergo (more so than men), it may not be evident in the general population.

Unwanted Pregnancies and Unplanned Births

In contrast to the voluminous literature on the relationship of infertility and unintended childlessness to mental health, few studies have considered the association of unplanned or mistimed births with distress for both men and women. Existing studies considered either psychological distress following induced abortion (Adler, David, Major, Roth, Russo, & Wyatt, 1990; Thorp, Hartmann, & Shadigian, 2003) or postpartum depression (Beck, 2001; Najman, Morrison, Williams, Andersen, & Keeping, 1991).

Comparisons of psychological and psychiatric consequences of induced abortions with those of term pregnancies yielded inconsistent results (Coleman, Reardon, Rue, & Cougle, 2002; Fergusson, John Horwood, & Ridder, 2006; Reardon, Cougle, Rue, Shuping, Coleman, & Ney, 2003). Recent studies attempted to explain this inconsistency by restricting their analyses to first pregnancies and explicitly measuring pregnancy intentions (Russo & Zierk, 1992; Schmiege & Russo, 2005). While it is safe to assume that abortions result from unintended pregnancies (Adler et al., 1990; Thorp et al., 2003), such assumptions cannot be made about pregnancies that are carried to term, which could have been either intended or unintended. Accurate measurement of pregnancy intentions is critical to drawing valid conclusions about the consequences of pregnancy intentions (should they result in births or not) on maternal health. However, the difficulties in measurement of pregnancy intentions have been previously highlighted (Santelli, Rochat, Hatfield-Timajchy, Gilbert, Curtis, Cabral et al., 2003). Schmiege and Russo (2005) linked women’s responses regarding pregnancy intentions at each interview with pregnancy outcomes since last interview (every two years) and found no evidence of elevated depression among women who aborted their first pregnancy. The prospective linking of intentions and outcomes is also important in order to avoid the bias associated with abortion concealment, particularly when reporting induced abortions of unintended pregnancies (Cougle, Reardon, & Coleman, 2003; Major & Gramzow, 1999). Similarly, research on unplanned births has been hampered by sampling issues and a lack of nationally representative samples, short follow-up periods and the inability to control for the history of psychological distress prior to experiencing fertility events (Cougle et al., 2003).

More recently, much interest has been directed to postpartum depression (PPD) that affects 10% to 20% of American women within six months of the birth of a child (Miller, 2002). While a recent meta-analysis (Beck, 2001) showed that pregnancy intentions (unplanned/unwanted pregnancy) are significant predictors of PPD, it also highlighted the fact that majority of the studies reviewed (78 out of 84) failed to consider fertility intentions in their analyses. Among the studies that considered intentions, Najman et al. (1991) found elevated rates of anxiety and depression among mothers of an unwanted child before, immediately following, and six months after birth (Najman et al., 1991). This association persisted with controls for age, income, marital status and parity, but appeared to dissipate over the six months of observation. This dissipating nature is characteristic of PPD itself, regardless of pregnancy intentions (Najman, Andersen, Bor, O’Callaghan, & Williams, 2000).

Hypotheses

The first hypothesis was that unintended childlessness and unplanned births would be associated with psychological distress, compared with intended childlessness and planned births.

The second hypothesis was that unintended childlessness and unplanned births would be differently associated with psychological distress at two stages of the life course, namely late and early 30s. Moreover, we expected to see gender differences in these associations.

Methods

Data were drawn from the publicly available files of the NLSY79, an ongoing longitudinal panel survey that since 1979 has been following a national probability sample of American civilian and military youth aged 14 to 21 years in 1978 (Zagorsky & White, 1999).

Measures

Depressive symptoms

Self-reports of depressive symptoms were measured by the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression scale (CES-D) (Radloff, 1977). In the NLSY79, the CES-D was assessed in 1992, 1994, and either in 1998, 2000, or 2002 (whenever the respondents reached 40 years of age). In addition, the 1992 wave used the full CES-D scale of 20 items, however the remaining waves used previously validated 7-item subscale (Mirowsky & Ross, 1989). For comparability, we used only the items from the 7-item subscale that are common to all data collection waves. These items were summed to create a scale ranging from 0 to 21, with higher values indicating more depressive symptoms. The internal consistency of the scale was acceptable (Cronbach’s alphas ranged between 0.77 and 0.84). We considered depressive symptoms in 1994 for early 30s and in 1998/2000/2002 for late 30s.

Fertility events

The NLSY79 asked men and women about their fertility intentions with the following question: “How many (more) children do you expect to have?” These questions were fielded in 1979, annually from 1982 to 1986, and biennially from 1986 until 2002, for a total of 14 time points covering 23 years of respondents’ life course. The number of children ever born (i.e., parity) at the time of data collection was assessed at every survey wave.

To distinguish four possible mutually exclusive fertility events that occurred over the two-year interval, we linked fertility intentions at time T among nulliparous individuals with parity two years later at time T + 2 (Table 1):

Table 1.

Fertility Events

| Intentions at T | Birth outcome at T+2 | Early 30s N | Late 30s N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intended childlessness | No | No | 535 | 433 |

| Unintended childlessness | Yes | No | 1068 | 174 |

| Planned birth | Yes | Yes | 258 | 27 |

| Unplanned birth | No | Yes | 22 | 5 |

Intended Childlessness: Childless individuals intending no child at time T and reporting zero parity at time T + 2.

Unintended Childlessness: Childless individuals intending a birth in the interval but reporting zero parity at time T + 2.

Planned births: Childless individuals intending to have a child at time T and reporting non-zero parity at time T + 2 (i.e., they experienced at least one birth in the interval).

Unplanned Births: Childless individuals intending no child at time T but reporting non-zero parity at time T + 2.

We constructed these four fertility events for two life course periods, namely when respondents were in their early and late 30s. For early 30s, we linked fertility intentions in 1992 (T) with parity in 1994 (T + 2). For late 30s, because CES-D data were collected only in 1998, 2000 or 2002 when individuals reached 40 years of age, we linked fertility intentions at time T (1996/1998/2000) with their respective parity and depression outcomes at T + 2 (1998/2000/2002). The four fertility events will be treated as a categorical variable in the regression analyses, with intended childlessness as a reference category.

Covariates

We controlled in all models for age at outcome (time T + 2), race (black, white (reference category)), marital status during the two-year intervals (never married during interval, married for the duration of the interval, other (reference category)). Respondents’ years of completed education were collected at each survey wave and ranged from 0 to 20 years. Three categories were created using years of completed education at time T (less than high school (reference category), high school, college or higher). Annual household income (in $’000s) collected over 23 years was first standardized to reflect the purchasing power in the year 2000 and then log-transformed to reflect the non-linear relationship between income and health. A household measure of annual income was preferred over individual income measures because household measures circumvent the fact that women may temporarily leave the labor force due to pregnancy and childbearing. In each model, we included income at time T − 1 (lagged income) and two variables to reflect a change in income during the intervals (between T − 1 and T + 2), which we dichotomized into two dummy variables to indicate an increase or a decrease in income over the period (respondents who reported the same income were the reference category).

To rule out mental health selection biases in these fertility events, we controlled for baseline depressive symptoms (CES-D) at time T (in 1992 for early 30s and in 1994 for late 30s), depression in early adulthood (yes/no; based on ICD-9 classification of a self-reported condition of depression between 1979 and 1981), and parental history of depression (yes/no; based on ICD-9 classification of a condition of depression, reported by respondents separately for mothers and fathers). Further, we included in our models measures of the number of previous intended and unintended childless spells occurring prior to time T to control for the extent to which baseline mental health status may be a function of the chronicity of unintended infertility (Benyamini et al., 2005).

Statistical Analyses

We conducted two gender-specific multivariate linear regression models using Stata 9.2: one for early 30s and another for late 30s. For early 30s, we regressed depressive symptoms in 1994 on the four fertility events occurring between 1992 and 1994, controlling for baseline depressive symptoms (CES-D in 1992) and all other covariates. For late 30s, we regressed depressive symptoms (either in 1996–1998–1998–2000, or 2000–2002, conditional on when the respondents turned 40 years old) on the four fertility events occurring in the preceding two year intervals, controlling for baseline depressive symptoms (CES-D in 1994) and all other covariates.

Missing values on all variables were deleted list-wise. Regression assumptions of homoscedasticity, normality of residuals, no multi-collinearity and no omitted variables (Ramsey RESET test) were verified and met. Results were weighted for attrition and sample selection using longitudinal weights produced by the NLSY79 and standard errors were corrected for intra-household correlation. Gender differences in the association of fertility events with depressive symptoms were assessed using Chow test, which examines whether the coefficients in the linear regression models are equal in separate subsamples of men and women using a chi-square statistic (Chow, 1960).

In other models (results not shown), we have also accounted for the presence of adopted and non-biological children, lifetime number of partners at outcome measurement, previous history of abortions and miscarriages (only among women), interactions with race, and pregnancy wantedness among individuals with recorded births at T + 2. We also limited the sample to (1) those with only one pregnancy between T and T + 2, (2) childless individuals who still intended to have children at T + 2, and (3) those individuals who reported intentions to have a child in the next two years. Finally, we tested within-individual fixed effects regression models for the first time period (early 30s) to control for time-invariant unobserved individual characteristics; the data did not allow us to estimate comparable fixed effects models for the late 30s due to the staggered cohort design and measurement of baseline depression in 1994. Because results remained stable across all these sensitivity analyses, we report results from the most parsimonious models only.

Results

Sample characteristics

There were 802 women and 1081 men in their early 30s and 274 women and 367 men in their late 30s. Respondents were on average 32 years old (± 2 years) and 40 years old (± 0.5 years), respectively (Table 2). The mean CES-D score among women was 3.7 and 3.5 in early and late 30s, and 2.7 among men in early and late 30s. The majority of these nulliparous individuals were white (about 60%), had a college degree (about 70% of women and 60% of men), and higher incomes ($50,000 to $54,000 for women and $44,000 to $45,000 for men). Similar proportions of respondents in early and late 30s were married during the two-year interval (39% and 38% of women, and 34% and 38% of men), while the proportion of respondents who were never married during the interval declined from early to late 30s (38% and 23% for women, and 46% and 29% for men). Compared to the NLSY respondents of the same ages with children, this sample of nulliparous individuals is, on average, more likely to be white, have a higher proportion of men and individuals who have never been married, be better educated, have higher incomes, and be more likely to experience an increase in income during the follow-up.

Table 2.

Means or percentage (SD or n, respectively) for respondents according to life course period (early 30s and late 30s) and gender

| Early 30s | Late 30s | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (N = 802) | Men (N = 1081) | Women (N = 274) | Men (N = 367) | |||||

| Mean/% | (SD)/(n) | Mean/% | (SD)/(n) | Mean/% | (SD)/(n) | Mean/% | (SD)/(n) | |

| Depressive Symptoms | ||||||||

| CES-D 1994 | 3.71 | (3.765) | 2.74 | (3.331) | --- | --- | --- | --- |

| CES-D 1998/2000/2002 | --- | --- | --- | --- | 3.51 | (4.298) | 2.74 | (3.639) |

| Fertility events | ||||||||

| Intended childlessness | 29.05 | (233) | 27.94 | (302) | 77.01 | (211) | 60.49 | (222) |

| Unintended childlessness | 56.48 | (453) | 56.89 | (615) | 18.98 | (52) | 33.24 | (122) |

| Planned birth | 13.47 | (108) | 13.88 | (150) | 3.28 | (9) | 4.90 | (18) |

| Unplanned birth | 1.00 | (8) | 1.30 | (14) | 0.00 | (0) | 1.36 | (5) |

| Covariates | ||||||||

| Age at outcome | 32.43 | (2.145) | 32.58 | (2.181) | 40.44 | (0.585) | 40.50 | (0.567) |

| Ethnicity: white | 62.84 | (504) | 65.31 | (706) | 58.03 | (159) | 61.85 | (227) |

| Ethnicity: black | 22.32 | (179) | 21.18 | (229) | 30.29 | (83) | 23.16 | (85) |

| Never married during spell | 37.91 | (304) | 46.44 | (502) | 23.36 | (64) | 28.88 | (106) |

| Married during spell | 38.78 | (311) | 33.86 | (366) | 37.59 | (103) | 37.87 | (139) |

| Education: < high school | 3.74 | (30) | 8.42 | (91) | 4.74 | (13) | 8.99 | (33) |

| Education: high school | 27.18 | (218) | 33.21 | (359) | 27.74 | (76) | 40.05 | (147) |

| Education: ≥ college | 69.08 | (554) | 58.37 | (631) | 67.52 | (185) | 50.95 | (187) |

| Household income at baseline (log) | 1.70 | (0.612) | 1.64 | (0.691) | 1.73 | (0.646) | 1.65 | (0.717) |

| Household income increase | 16.11 | (129) | 18.01 | (195) | 14.37 | (39) | 15.64 | (57) |

| Household income decrease | 12.09 | (97) | 13.76 | (149) | 14.13 | (39) | 16.08 | (59) |

| Baseline CES-D | 4.10 | (4.007) | 3.42 | (3.505) | 3.96 | (3.939) | 3.02 | (3.707) |

| Early depression | 0.37 | (3) | 0.19 | (2) | 0.73 | (2) | 0.82 | (3) |

| Mother’s depression | 1.37 | (11) | 0.56 | (6) | 2.19 | (6) | 1.63 | (6) |

| Father’s depression | 1.25 | (10) | 0.83 | (9) | 2.92 | (8) | 2.18 | (8) |

| No. previous intended childless spells | 1.21 | (1.913) | 1.03 | (1.761) | 3.62 | (3.020) | 3.23 | (3.015) |

| No. previous unintended childless spells | 6.46 | (2.093) | 6.52 | (2.045) | 7.19 | (3.172) | 7.36 | (3.187) |

In terms of the prevalence of fertility events, there were no differences between men and women in their early 30s. The most common fertility event was unintended childlessness, experienced by more than half of respondents (56–57%). Intended childlessness was experienced by a third (28–29%) of respondents. Finally, about 13–14% and 1% of respondents experienced births that were planned and unplanned, respectively. By late 30s, gender differences had emerged and intended childlessness had become the most common status, followed by unintended childlessness. Intended childlessness was experienced by 60% of men and 77% of women, while 33% of men and 19% of women experienced unintended childlessness. More men than women had births, both planned and unplanned. While no women had unplanned births, 1% of men did so.

Change in intentions

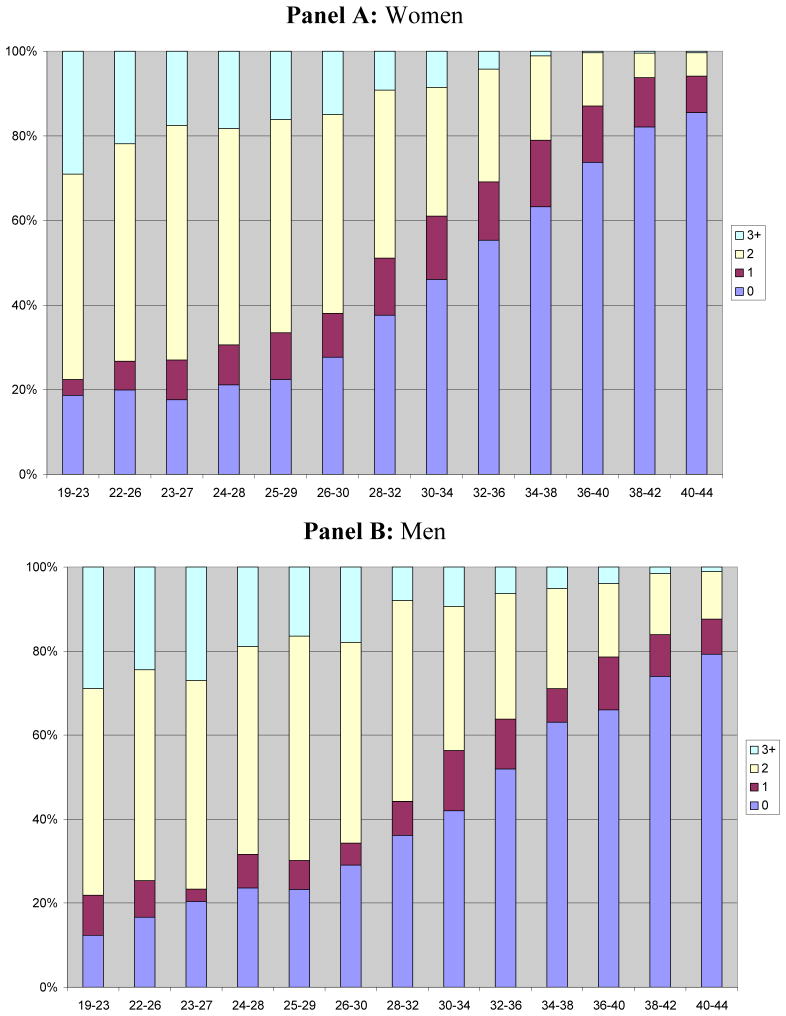

We tracked the evolution of the fertility intentions over an individual’s life course for a subsample of NLSY79 men (N=1067) and women (N=1347) who were childless in 2002 and hence throughout the observation period (Figure 1). The NLSY79 respondents who remained childless throughout their life course progressively revised their intentions downwards. Less than a quarter of men and women intended to have no children when they were in their 20s. By late 30s and early 40s, individuals revised their fertility intentions such that more than three-quarters of men and women intended to have no children. The number of previous intended childless spells among nulliparous respondents also increased from early to late 30s for both men and women from 1% to 3% (Table 2).

Figure 1.

Evolution of fertility intentions for childless individuals by age, for women and men

Depressive symptoms in early 30s

Having an unplanned birth in early 30s was significantly associated with depressive symptoms for men (Table 3), with men who had an unplanned birth scoring 2.5 points higher on depressive symptoms than men who were intentionally childless. However, this association was not replicated for women and tests of structural change indicated that the difference in the magnitude of the association between men and women was significant (complete model: χ2 = 15.11; p = 0.0001, Table 4). There was no association between depressive symptoms and unintended childlessness (relative to intended childlessness) among either men or women. There were no other significant associations of fertility events with respondents’ depressive symptoms.

Table 3.

Beta estimates (standard error) for fertility events and covariates on depressive symptoms by life course period (early 30s and late 30s) and gender

| Early 30s | Late 30s | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Fertility events | ||||

| Unintended childlessness | 0.44 (0.389) | −0.01 (0.313) | −0.06 (0.675) | −0.14 (0.423) |

| Planned birth | 0.23 (0.487) | 0.01 (0.334) | 0.68 (1.268) | 0.50 (1.019) |

| Unplanned birth | −0.11 (0.714) | 2.51* (1.059) | 1.61 (1.257) | |

|

| ||||

| Covariates | ||||

| Age at outcome | 0.01 (0.072) | 0.05 (0.044) | 0.04 (0.406) | 0.20 (0.305) |

| Ethnicity: black | −0.58 (0.301) | 0.04 (0.281) | −0.68 (0.678) | 0.00 (0.585) |

| Never married during spell | −0.01 (0.414) | 0.42 (0.267) | 0.36 (0.844) | 0.28 (0.533) |

| Married during spell | 0.22 (0.428) | 0.22 (0.280) | 0.23 (0.593) | 0.16 (0.404) |

| Education: high school | −0.63 (0.596) | 0.11 (0.537) | 1.28 (1.207) | −1.86 (1.005) |

| Education: = college | −1.12 (0.580) | 0.07 (0.551) | 0.05 (1.144) | −2.16* (0.976) |

| Household income at baseline (log) | −0.63* (0.300) | −0.75** (0.225) | −0.48 (0.508) | −0.78* (0.362) |

| Household income increase | −0.41 (0.589) | −0.86** (0.291) | −1.65 (1.122) | −0.32 (0.567) |

| Household income decrease | −0.50 (0.554) | 0.82 (0.483) | −1.01 (0.607) | −0.13 (0.342) |

| Baseline CES-D | 0.39** (0.038) | 0.35** (0.038) | 0.38** (0.086) | 0.30** (0.072) |

| Early depression | −0.45 (0.558) | 2.06** (0.659) | 4.82 (3.257) | −0.01 (3.169) |

| Mother’s depression | 1.49 (1.416) | 3.28 (2.668) | 1.35 (1.577) | 2.03 (2.064) |

| Father’s depression | −0.53 (0.939) | −0.17 (1.122) | 0.33 (1.375) | −0.53 (0.996) |

| No. previous intended childless spells | −0.15 (0.161) | 0.02 (0.130) | 0.16 (0.202) | 0.06 (0.175) |

| No. previous unintended childless spells | −0.23 (0.137) | 0.02 (0.112) | 0.07 (0.210) | 0.05 (0.164) |

|

| ||||

| Constant | 2.432 | 2.142 | 2.650 | 2.180 |

| Observations | 802 | 1081 | 274 | 367 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.23 | 0.21 |

significant at 5%

significant at 1%

Robust standard errors in parentheses.

Table 4.

Gender differences in the association of fertility events and covariates with depressive symptoms.

| Early 30s | Late 30s | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | p | χ2 | df | p | |

| Fertility events | ||||||

| Unintended childlessness | 0.81 | 1 | 0.37 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.92 |

| Planned birth | 0.14 | 1 | 0.71 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.91 |

| Unplanned birth | 4.22* | 1 | 0.04 | --- | 1 | --- |

|

| ||||||

| Covariates | ||||||

| Age at outcome | 0.21 | 1 | 0.65 | 0.11 | 1 | 0.74 |

| Ethnicity: black | 2.26 | 1 | 0.13 | 0.57 | 1 | 0.45 |

| Never married during spell | 0.74 | 1 | 0.39 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.94 |

| Married during spell | 0.00 | 1 | 0.99 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.93 |

| Education: high school | 0.86 | 1 | 0.35 | 3.87 | 1 | 0.04 |

| Education: ≥ college | 2.19 | 1 | 0.14 | 2.10 | 1 | 0.15 |

| Household income at baseline (log) | 0.11 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.23 | 1 | 0.63 |

| Household income increase | 0.48 | 1 | 0.49 | 1.09 | 1 | 0.30 |

| Household income decrease | 3.20 | 1 | 0.074 | 1.60 | 1 | 0.21 |

| Baseline CES-D | 0.61 | 1 | 0.43 | 0.64 | 1 | 0.42 |

| Early depression | 8.49 | 1 | 0.003 | 1.13 | 1 | 0.29 |

| Mother’s depression | 0.35 | 1 | 0.55 | 0.07 | 1 | 0.80 |

| Father’s depression | 0.06 | 1 | 0.81 | 0.25 | 1 | 0.61 |

| No. previous intended childless spells | 0.66 | 1 | 0.42 | 0.16 | 1 | 0.69 |

| No. previous unintended childless spells | 1.93 | 1 | 0.16 | 0.01 | 1 | 0.93 |

|

| ||||||

| Complete Model | 51.11 | 19 | 0.0001 | 15.21 | 19 | 0.6472 |

Depressive symptoms in late 30s

Although having an unplanned birth later in life increased depressive symptoms for men by 1.6 points relative to men who remained intentionally childless throughout the interval (and up until that point in their life course), this association was no longer significant (Table 3). Tests of structural change could not be estimated for these coefficients because there were no women in the category of unplanned births in late 30s, likely because declining female fecundity substantially decreases the odds of experiencing a birth, whether planned or not (Table 4). There was no significant relation between unintended childlessness and depressive symptoms for either men or women. No other fertility events showed a significant relationship with depressive symptoms during that period and no significant gender differences were evident (complete model: χ2 = 15.21; p = 0.6472, Table 4).

Discussion

Overall, results of this study showed little support for our first hypothesis that unintended childlessness and unplanned births could be detrimental to mental health. However, having an unplanned birth was associated with increased depressive symptoms for men in their early 30s, indicating that the experience of having an unintended (first) child increases psychological distress for younger men. This finding is consistent with a previous study based on small clinical samples of cohabiting couples that found CES-D scores four months after an unplanned first birth were (marginally) elevated among men in their early 30s (average age 31.5 years old) (Leathers & Kelley, 2000). On the other hand, depressive symptoms among women increased only if their male partner perceived the pregnancy to be unintended, suggesting that the association of unwanted or mistimed pregnancies with depressive symptoms may occur through different relationship processes for men and women (Thomson, 1997).

Both unintended childlessness and unplanned births can be considered undesirable life events. Unintended childlessness, a mismatch between intentions and fertility outcomes, may lead to psychological distress by preventing people from achieving a valued identity (McQuillan et al., 2003) and involving a sense of loss of control (Mirowsky & Ross, 1989, 2003). While unplanned births also involve loss of control by giving up a potentially valued identity of being childless (Park, 2005), they create an unexpected change in material circumstances (Turner et al., 1995). Thus, while the mechanisms by which unintended childlessness and unplanned births affect mental health are unclear, unplanned births may enhance risks to mental health if they involve both loss of control and an unexpected change in material circumstances.

In terms of the lack of association of unplanned births for women, it is possible that this is not a true finding, but could rather be attributed to unmeasured factors. For instance, women who intended and remained childless over the two-year observation period (reference group) could be in fact at risk of elevated depressive symptoms if they had an induced abortion in the interim, which would attenuate the association. Women also have more control over pregnancy outcomes than men. Indeed, the proportion of women who terminate unwanted pregnancy appears to increase substantially with age as nearly 60% to 70% of women terminate unwanted pregnancies (though these are not necessarily first pregnancies) in their late 30s and early 40s, respectively (Menken, 1985). Moreover, the abortion concealment rate has been argued to be high in the NLSY79 (Cougle et al., 2003). However, the most recent research on this topic shows that there are no associations between abortions and negative outcomes in this sample (Schmiege & Russo, 2005). In our sensitivity analyses, we also estimated within-individual fixed effects models for early 30s, controlling for previous miscarriages, abortions or a tendency toward concealment, and found the same results.

Although Beck (2001) showed in a meta-analysis that unplanned or unwanted pregnancies are a risk factor for post-partum depression (PPD) among women (Beck, 2001), these studies generally indicate that the relationship of PPD with unwanted pregnancy dissipates over six months of observation (Najman et al., 2000). Since our period of observation spans two years, our study design is not well positioned to capture such an association. Moreover, couple’s intentions are crucial to understanding fertility patterns (Thomson, 1997) since women suffer greater depression from unplanned births only if their partners were un prepared for the birth (Leathers & Kelley, 2000). However, we could not capture couple’s intentions in these analyses.

Overall, there was no variation in the relationship of unintended childlessness with depressive symptoms either by period of the life course or by gender. This lack of association in early 30s is not surprising as individuals are in their prime reproductive years and may still be holding out the possibility of having a child. However, unintended childlessness was not detrimental to psychological distress later in life when individuals are nearing the end of their reproductive life span and may have been exposed to life stressors such as miscarriage and fertility treatment. Previous studies have shown that individuals’ fertility intentions are not static, rather they are revised over the life course (Matthews & Matthews, 1986; McAllister & Clarke, 1998; Miall, 1986). We demonstrated this phenomenon with the NLSY data, showing that nulliparous individuals revised their fertility intentions as they progressed through their lives and these changes in intentions were pervasive. The gender differences in the extent to which they did so were also congruent with declining fecundity patterns over the life course. Therefore, individuals who were involuntarily childless earlier in life had likely revised their intentions to being voluntarily childless, thus adapting their fertility goals to their life circumstances.

Involuntary childlessness was also found to be more prevalent at younger ages among Norwegian nulliparous individuals, while voluntary childlessness increased with advancing age (Rostad, Schei, & Sundby, 2006). Using two different subsamples from the U.S. National Survey of Families and Households (NSFH), two studies showed that 13% of 19–39 year old childless individuals switched from intending to have children at one survey to no longer intending by the next wave six years later (Heaton et al., 1999) and 15% of respondents at all parity stages went through the same change in their intentions (White & McQuillan, 2006). Both studies used panels of the NSFH that were six years apart, thus increasing the likelihood that a greater number of individuals would experience the change in intentions. Moreover, White and McQuillan (2006) found that among individuals with a serious intent to have children, those who relinquished these intentions had elevated distress. It is possible that the group of individuals who were unintentionally childless in our analyses encompasses those who relinquished such intentions in the interim and those who still intended to have a child, thus diluting the distressful outcome of unintended childlessness. However, because revising fertility intentions is a gradual process, it is unlikely to affect a large proportion of respondents over a two-year period used in our study. Future studies should address the issue of change in intentions and mental health in greater detail. Lastly, we did not detect any significant associations between planned births and psychological distress, although previous studies reported that parenthood, including desired parenthood, has negative consequences on adults’ psychological well-being (McLanahan & Adams, 1987).

This paper makes several important contributions to the existing literature. The key contribution of our study is the prospective linkage of fertility intentions with subsequent fertility outcomes in order to assess more accurately the desirability of fertility outcomes. We considered four possible fertility events, planned and unplanned births, and intended and unintended childlessness. We examined together the previously separate fertility outcomes, namely infertility and unintended childlessness as well as unwanted pregnancies and unplanned births. We also adopted a life course perspective to consider the impact of discordance between fertility intentions and outcomes at two points in the lives of men and women. Differential biological constraints on fertility and the socially gendered meaning of parenthood call for a gender-specific analysis of life course variations in these processes. Lastly, we also controlled for the history of depressive symptoms (CES-D scale) prior to experiencing fertility events.

Results of this study are limited to nulliparous men and women and may not hold for individuals with children who experience discordance between their fertility intentions and outcomes. We reported earlier that the respondents in our sample of nulliparous individuals are a select group who are more likely to be single and have higher education and income levels, the attributes that may alleviate a mismatch between their intentions and outcomes. The lack of association between unintended childlessness and psychological distress among individuals in late 30s may also be due to social desirability bias in reporting a negative association of childlessness, however no research studies have investigated this possibility.

Moreover, the wording of the question on fertility intentions in the NLSY questionnaire we used to construct the four fertility events (“How many (more) children do you expect to have?”) may not fully capture people’s intentions. Since the question places no time dimension on the expectation to have children, it may not capture fertility intentions of people who expect to have children at some point in the future, but are not trying to have them in the next two years, leading to a misclassification of people in the intended and unintended childlessness categories. In our sensitivity analyses, we limited our sample to those individuals who reported intentions to have a child in the next two years (i.e., time-constrained intentions) and found the same results. Moreover, since the meaning of the word “expect” is not the same as “hope” or “want”, this question may not capture intentions of people with known fertility problems, who may not “expect” to have any children but may still want or hope to have them. The meaning of the word “expect” may also be interpreted differently by different people (Barrett & Wellings, 2002).

Similarly, the strength of fertility intentions was not assessed in this study, which may explain a lack of association of unintended childlessness for either men or women. Further, we could not assess in this study the relationship of partners’ agreement in intentions, which has been shown to be most relevant for women with an unintended first birth (Leathers & Kelley, 2000). Individual’s satisfaction with their relationship has also been shown to ameliorate the psychological distress from unmet fertility intentions (Peterson, Newton, & Rosen, 2003), however we could not assess this in our study because a measure of respondent’s degree of happiness with their relationship or marriage was only included for women in NLSY, and not for men. Finally, given that the CES-D scale excels as a general symptomatology instrument, it is possible that it is not suited to capture specific symptoms associated with pregnancy- and childbearing-related outcomes, and therefore, may have understated women’s negative experiences related to unplanned births.

In conclusion, results of this study suggest that among nulliparous individuals in their early and late 30s, having or not having a child (whether expected or not) is not associated with psychological distress. However, we found that men with unplanned births in their early 30s may be at a higher risk of depressive symptoms. Since this group of individuals has been all but absent from studies of fertility intentions and mental health, future studies should include men of this age to assess the causes of their distress and sources of resilience.

Footnotes

Our measure of childlessness can not be equated with infertility, which is a medical term that refers to an inability to conceive after 12 months of unprotected intercourse, and does not depend on the individual’s desire to have children. Although both “infertility” and “childlessness” have been used to define the absence of motherhood, the term “childless” refers to individuals with a range of intentions and desires for a child, including those who remain childless by choice (Gillespie, 2003).

Although evidence exists that psychological distress may be a significant factor in the etiology of infertility (Wasser, Sewall, & Soules, 1993), the idea that psychological distress may cause infertility has lost popularity as studies conducted in the last two decades showed that stress is more likely to be the result than the cause of infertility and the debate in the current literature has centered on the so-called “psychological consequences hypothesis” (Greil, 1997).

Contributor Information

Amélie Quesnel-Vallée, Department of Sociology, Department of Epidemiology, Biostatistics, and Occupational Health, McGill University.

Katerina Maximova, Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McGill University, Montreal, Canada.

References

- Adler NE, David HP, Major BN, Roth SH, Russo NF, Wyatt GE. Psychological Responses After Abortion. Science. 1990;248(4951):41–44. doi: 10.1126/science.2181664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett G, Wellings K. What is a ‘planned’ pregnancy? Empirical data from a British study. Social Science & Medicine. 2002;55(4):545–557. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(01)00187-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck CT. Predictors of postpartum depression - An update. Nursing Research. 2001;50(5):275–285. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200109000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beets GCN, Liefbroer AC, Gierveld J. Changes in fertility values and behaviour: A life course perspective. In: Lee R, editor. Dynamics of values in fertility change. Oxford, England: Oxford Press; 1999. pp. 100–120. [Google Scholar]

- Benyamini Y, Gozlan M, Kokia E. Variability in the difficulties experienced by women undergoing infertility treatments. Fertility and Sterility. 2005;83(2):275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra A, Stephen EH. Impaired fecundity in the United States: 1982–1995. Family Planning Perspectives. 1998;30(1):34–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chow GC. Tests of Equality Between Sets of Coefficients in 2 Linear Regressions. Econometrica. 1960;28(3):591–605. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PK, Reardon DC, Rue VM, Cougle J. State-funded abortions versus deliveries: A comparison of outpatient mental health claims over 4 years. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2002;72(1):141–152. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.72.1.1410155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cougle JR, Reardon DC, Coleman PK. Depression associated with abortion and childbirth: a long-term analysis of the NLSY cohort. Medical Science Monitor. 2003;9(4):CR157–CR164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend BS, Dohrenwend BP. Stressful Life Events and Their Context. New York: Prodist; 1981. Life Stress and Illness: Formulation of the Issues. [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, John Horwood L, Ridder EM. Abortion in young women and subsequent mental health. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(1):16–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie R. Childfree and feminine - Understanding the gender identity of voluntarily childless women. Gender & Society. 2003;17(1):122–136. [Google Scholar]

- Greil AL. Infertility and psychological distress: A critical review of the literature. Social Science & Medicine. 1997;45(11):1679–1704. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00102-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagewen KJ, Morgan SP. Intended and ideal family size in the United States, 1970–2002. Population and Development Review. 2005;31(3):507. doi: 10.1111/j.1728-4457.2005.00081.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaton TB, Jacobson CK, Holland K. Persistence and change in decisions to remain childless. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1999;61(2):531–539. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan C, Revenson TA. Gender differences in coping with infertility: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1999;22(4):341–358. doi: 10.1023/a:1018774019232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King RB. Subfecundity and anxiety in a nationally representative sample. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;56(4):739–51. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koropeckyj-Cox T, Pendell G. The gender gap in attitudes about childlessness in the United States. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2007;69(4):899–915. [Google Scholar]

- Leathers SJ, Kelley MA. Unintended pregnancy and depressive symptoms among first-time mothers and fathers. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(4):523–531. doi: 10.1037/h0087671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Major B, Gramzow RH. Abortion as stigma: Cognitive and emotional implications of concealment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1999;77(4):735–745. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.4.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews R, Matthews AM. Infertility and Involuntary Childlessness - the Transition to Nonparenthood. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1986;48(3):641–649. [Google Scholar]

- McAllister F, Clarke L. Choosing Childlessness. Family & Parenthood, Policy & Practice. London: Family Policy Studies Centre; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- McLanahan S, Adams J. Parenthood and Psychological Well-Being. Annual Review of Sociology. 1987;13:237–257. [Google Scholar]

- McQuillan J, Greil AL, White L, Jacob MC. Frustrated fertility: Infertility and psychological distress among women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2003;65(4):1007–1018. [Google Scholar]

- Menken J. Age and Fertility - How Late Can You Wait. Demography. 1985;22(4):469–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miall CE. The Stigma of Involuntary Childlessness. Social Problems. 1986;33(4):268–282. [Google Scholar]

- Miller LJ. Postpartum depression. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287(6):762–765. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.6.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Social Causes of Psychological Distress. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mirowsky J, Ross CE. Education, Social Status, and Health. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan SP. Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century childlessness. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97(3):779–807. doi: 10.1086/229820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Andersen MJ, Bor W, O’Callaghan MJ, Williams GM. Postnatal depression - myth and reality: maternal depression before and after the birth of a child. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2000;35(1):19–27. doi: 10.1007/s001270050004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najman JM, Morrison J, Williams G, Andersen M, Keeping JD. The Mental-Health of Women 6 Months After They Give Birth to An Unwanted Baby - A Longitudinal-Study. Social Science & Medicine. 1991;32(3):241–247. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90100-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park K. Choosing childlessness: Weber’s typology of action and motives of the voluntarily childless. Sociological Inquiry. 2005;75(3):372–402. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Menaghan EG, Lieberman MA, Mullan JT. The Stress Process. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1981;22(4):337–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin LI, Skaff MM. Stress and the life course: A paradigmatic alliance. Gerontologist. 1996;36(2):239–247. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BD, Newton CR, Rosen KH. Examining congruence between partners’ perceived infertility-related stress and its relationship to marital adjustment and depression in infertile couples. Family Process. 2003;42(1):59–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2003.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quesnel-Vallee A, Morgan SP. Missing the target? Correspondence of fertility intentions and behavior in the US. Population Research and Policy Review. 2003;22(5–6):497–525. [Google Scholar]

- Rabkin JG, Struening EL. Life Events, Stress, and Illness. Science. 1976;194(4269):1013–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.790570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1(3):385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon DC, Cougle JR, Rue VM, Shuping MW, Coleman PK, Ney PG. Psychiatric admissions of low-income women following abortion and childbirth. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2003;168(10):1253–1256. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostad B, Schei B, Sundby J. Fertility in Norwegian women: Results from a population-based health survey. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health. 2006;34(1):5–10. doi: 10.1080/14034940510032383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo NF. Motherhood Mandate. Journal of Social Issues. 1976;32(3):143–153. [Google Scholar]

- Russo NF, Zierk KL. Abortion, Childbearing, and Womens Well-Being. Professional Psychology-Research and Practice. 1992;23(4):269–280. [Google Scholar]

- Santelli J, Rochat R, Hatfield-Timajchy K, Gilbert BC, Curtis K, Cabral R, et al. The measurement and meaning of unintended pregnancy. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2003;35(2):94–101. doi: 10.1363/3509403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt L. Psychosocial burden of infertility and assisted reproduction. Lancet. 2006;367(9508):379–380. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmiege S, Russo NF. Depression and unwanted first pregnancy: longitudinal cohort study. British Medical Journal. 2005;331(7528):1303–1306A. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38623.532384.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson E. Couple childbearing desires, intentions, and births. Demography. 1997;34(3):343–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorp JM, Hartmann KE, Shadigian E. Long-term physical and psychological health consequences of induced abortion: Review of the evidence. Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey. 2003;58(1):67–79. doi: 10.1097/00006254-200301000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ, Wheaton B, Lloyd DA. The Epidemiology of Social Stress. American Sociological Review. 1995;60(1):104–125. [Google Scholar]

- Veevers JE. Voluntary childlessness and social policy: an alternative view. Family Planning Resume. 1977;1(1):254–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasser SK, Sewall G, Soules MR. Psychosocial Stress As A Cause of Infertility. Fertility and Sterility. 1993;59(3):685–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L, McQuillan J. No longer intending: The relationship between relinquished fertility intentions and distress. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2006;68(2):478–490. [Google Scholar]

- Wright J, Allard M, Lecours A, Sabourin S. Psychosocial Distress and Infertility - A Review of Controlled Research. International Journal of Fertility. 1989;34(2):126–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright J, Bissonnette F, Duchesne C, Benoit J, Sabourin S, Girard Y. Psychosocial Distress and Infertility - Men and Women Respond Differently. Fertility and Sterility. 1991;55(1):100–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zagorsky JL, White L. NLSY79 User’s Guide: A guide to the 1979–1998 national longitudinal survey of youth data. Washington, DC: US Department of Labor; 1999. [Google Scholar]