Abstract

The three proteasome subunits with proteolytic activity are encoded by standard or immunoproteasome genes. Many proteasomes expressed by normal cells and cells exposed to cytokines are “mixed”, that is, contain both standard and immunoproteasome subunits. Using a panel of 38 defined influenza A virus–derived epitopes recognized by C57BL/6 mouse CD8+ T cells, we used mice with targeted disruption of β1i, β2i, or β5i/β2i genes to examine the contribution of mixed proteasomes to the immunodominance hierarchy of antiviral CD8+ T cells. We show that each immunoproteasome subunit has large effects on the primary and recall immunodominance hierarchies due to modulating both the available T cell repertoire and generation of individual epitopes as determined both biochemically and kinetically in Ag presentation assays. These findings indicate that mixed proteasomes function to enhance the diversity of peptides and support a broad CD8+ T cell response.

Immunodominance (ID) is a central feature of T cell responses. T cell responses to multiple pathogen-derived peptides and other complex Ags form a hierarchy based on the number of responding cells. This hierarchy tends to be highly reproducible in individuals expressing the same restricting MHC allomorphs. The CD8+ T cell (TCD8+) response to influenza A virus (IAV) in C57BL/6 mice is the most extensively studied mouse ID model with nearly 40 immunodominant (IDD) and subdominant determinants (SDD) reported derived from 10 of the 11 known open reading frames translated in IAV-infected cells (1-3) (Immune Epitope Database, http://www.iedb.org/).

Given that an IAV-encoded peptide binds class I with sufficient affinity, the most important factors in governing its position in the ID hierarchy are the numbers of naive TCD8+ and the amount of peptide generated by APCs. Both of these factors are influenced by proteasome composition (4, 5). Proteasomes have three active subunits, β1, β2, and β5, that can be replaced by the immune versions, β1i, β2i, and β5i, to create immunoproteasomes. Immunoproteasomes are constitutively expressed by dendritic cells (DCs) and many other bone marrow–derived cells, and are induced in other cells by exposure to IFNs and other cytokines. Although immunoproteasomes are known to influence the generation of individual peptides and alter the TCD8+ repertoire to certain viral peptides, the systematic impact of the immunoproteasome on ID hierarchies remains an important question.

Expanding on prior work with mice lacking one or two immunoproteasome subunits, Kincaid et al. (6) studied TCD8+ responses to nine defined foreign determinants after knocking out all three immunoproteasome subunits. TCD8+ responses are more broadly impaired in the absence of all immunoproteasome subunits than in individual subunit-deficient strains, and the self immunopeptidome is clearly greatly altered, as determined by mass spectrometry. It is also important, however, to understand the effects of missing one or two subunits, because “mixed” proteasomes with both standard and immunoproteasome subunits are commonly expressed at high levels constitutively (up to 50% of proteasomes) in human monocytes, immature and mature DCs, and liver, intestine, and kidney cells, and also following cytokine induction of immunoproteasome subunits in other cells (7).

Multiple studies have reported that recall responses to IAV amplify and even reshuffle the primary ID hierarchy (8-10). During primary TCD8+ responses, the small numbers of naive TCD8+ appear to have ample access to infected or cross-priming DCs. Upon recall, however, memory TCD8+ must compete for APCs (8, 11-13), and they are at a disadvantage when their cognate peptides are generated with slower kinetics than other peptides (13). Given that immunoproteasome subunits can greatly influence epitope presentation, it is possible that they play a major role in shaping secondary ID hierarchies (14, 15).

To explore the role of mixed proteasomes on antiviral TCD8+ responses, we examine the effect of knocking out β1i, β2i, and β5i/β2i on the generation of primary and recall immune response to 38 IAV peptides.

Materials and Methods

Mice

Wild-type (wt) C57BL/6 (B6) mice were purchased from Walter Eliza Hall Institute of Medical Research (Kew, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). LMP2−/− mice were a gift from Dr. L.Van Kaer (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN). LMP7/MECL-1−/− and MECL-1−/− mice were a gift from Dr. John Monaco (Department of Molecular Genetics, Biochemistry, and Microbiology, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, OH). Mice were housed in specific pathogen-free isolators. Experiments were performed with animals aged at 6–12 wk and were conducted under the auspices of the Austin Health Animal Ethics Committee and conformed to the National Health and Medical Research Council Australian code of practice for the care and use of animals for scientific purposes.

Peptides and Abs

IAV peptides were synthesized by Mimotopes (Clayton, VIC, Australia) with purity >95%. A complete list of peptide sequences, elution times, and MHC class I restriction can be found in Table I. PE-labeled anti–IFN-γ and APC-labeled anti-CD8α were purchased from eBioscience (San Diego, CA). For flow cytometry, Abs were used at 1:300 dilution in PBS supplemented with 10% FCS. IL-2 was purchased from Roche (Pleasanton, CA) and Proleukin (San Diego, CA).

Table I.

Reported IAV H-2b –restricted epitopes

| Peptide | Sequence | Restriction | Elution Time (min) |

|---|---|---|---|

| HA243-250 | MNYYWTLL | Kb | 28.205 |

| HA290–297 | ECNTKCQT | Likely Kb | 24.308 |

| HA304–311 | SSLPYQNI | Db Kb | 21.623 |

| HA332–340 | TGLRNTPSI | Db | 19.597 |

| HA402–409 | MNIQFTAV | Kb | 23.873 |

| HA468–476 | SQLKNNAKEI | Db | 17.824 |

| HA475–482 | KEIGNGCFEF | Db | 27.652 |

| Mll28–135 | MGLIYNRM | Kb | 23.540 |

| NA46–54 | TGICNQNII | Db | 23.042 |

| NA54–62 | ITYKNSTWV | Db | 21.078 |

| NA181–189 | SGPDNGAVAV | Db | 18.559 |

| NA335–343 | YRYGNGVWI | Db | 25.140 |

| NA425–432 | SSISFCGV | Kb | 27.350 |

| NA430–438 | FCGVNSDTV | Db | 20.160 |

| NP17–25 | GERQNATEI | Db | 16.601 |

| NP35–42 | IGRFYIQM | Kb | 25.570 |

| NP55–63 | RLIQNSLTI | Db | 22.889 |

| NP97–105 | YRRVNGKWM | Db | 19.709 |

| NP217–225 | IAYERMCNI | Kb | 22.384 |

| NP366–374 | ASNENMETM | Db | 17.998 |

| NS1133–140 | FSVIFDRL | Kb | 27.377 |

| NS2114–121 | RTFSFQLI | Kb | 27.377 |

| PA224–233 | SSLENFRAYV | Db | 24.706 |

| PA238–245 | NGYIEGKL | Kb | 21.279 |

| PA300–307 | GIPLYDAI | Kb | 26.044 |

| PA463–470 | VYINTALL | Kb | 24.576 |

| PA648–655 | SLYASPQL | Kb | 21.502 |

| PB1141–149 | TALANTIEV | Db | 22.788 |

| PB1214–221 | RSYLIRAL | Kb | 23.737 |

| PB1465–472 | RFYRTCKL | Kb | 20.183 |

| PB1653–660 | KNMEYDAV | Kb | 18.350 |

| PB1703–711 | SSYRRPVGI | Kb | 19.914 |

| PB1F262–70 | LSLRNPILV | Db | 25.933 |

| PB2196–206 | CKISPLMVAYM | Kb | 26.260 |

| PB2198–206 | ISPLMVAYM | Likely Db | 26.420 |

| PB2227–234 | VYIEVLHL | Kb | 26.173 |

| PB2358–365 | GYEEFTMV | Kb | 24.443 |

| PB2689–696 | VLRGFLIL | Kb | 29.134 |

Peptide sequences, reported MHC class I restriction, and RP-HPLC elution time on an Agilent 1100 instrument are shown. To determine the exact time that each naturally processed and presented IAV peptide elutes from the HPLC, the elution times of the 38 IAV-derived synthetic peptides were first determined (the elution times are indicated in Fig. 3 and Supplemental Fig. 2 as vertical lines). The data indicate distinct elution time points over a range of ~13 min under the selected running program and solvent gradient. Several peptides were observed to elute at similar time points, such as HA332–340 and NP97–105.

Viruses and mouse immunization

Mice were infected i.p. with 107 PFU IAVs, including Puerto Rico/8/34 H1N1 (PR8) and its reassortant strain X-31 (H3N2).

Cell line culture

RMA-s and EL4 cells were cultured in RF-10: RPMI 1640 containing 10% FCS, 50 μM 2-ME, 2 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin (all from Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). Cells were passaged when reaching 80% confluent and used during the exponential growth phase.

Bone marrow–derived DCs, TCD8+ cultures, and brefeldin A kinetics

The detailed methods were previously described (16, 17). Briefly, bone marrow cells were flushed from femurs and RBCs were lysed and cultured in RF-10 in the presence of GM-CSF for 8 d. For generating polyspecificity TCD8+ cultures, bone marrow–derived DCs (BMDCs) were infected with PR8 at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 10 in FCS-free, acidified RPMI 1640 for 1 h at 37°C. RF-10 (10 ml) was then added and further incubated for 5 h. The infected cells were then washed, irradiated (10,000 rad), and used as APCs to stimulate PR8-specific memory splenic cells. For generating peptide-specific TCD8+ cultures, 1 million memory splenic cells were pulsed with 1 nM peptide of interest for 60 min and then cocultured with 9 million unpulsed memory splenic cells in RF-10 containing 10 U IL-2/ml (T cell media). Beading of CD4+ and B220+ cells was performed if required from day 5 onward after removal of dead cells by Ficoll-Paque gradient. For BFA kinetics assay, BMDCs or EL-4 cells were infected with 10 MOI of PR8 for 1 h at 37°C, washed, and then added to monospecificity TCD8+ cultures, with BFA added at various time points. Following 4 h exposure to BFA, cells were transferred onto ice and stained by intracellular cytokine staining (ICS) for IFN-γ (17).

B220/CD4 beading

CD4- and B220-expressing cells were removed from TCD8+ cultures via magnetic separation. Briefly, Dynal beads (Invitrogen) coated with purified rat anti-mouse CD4 and B220 Abs (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ) were incubated with cultured cells for 10 min at room temperature. Particle-bound cells were depleted via magnetic separation, with cells left in supernatant resuspended in T cell media (18).

In vitro activation of ex vivo Ag-specific TCD8+ and enumeration by ICS

Peritoneal exudates and spleens were collected in RF-10. The Ag-specific TCD8+ were enumerated using ICS for the production of IFN-γ after being stimulated with 1 μM antigenic peptide unless otherwise stated (19). Briefly, samples were stained with anti-CD8 for 20 min, washed and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, and then stained with anti-IFN-γ Ab in the presence of 0.4% saponin. Samples were then washed, acquired on a FACSCanto II (BD Biosciences), and analyzed by FlowJo software (Tree Star, Ashland, OR).

Peptide extraction, reverse-phase HPLC fractionation, and assessment by TCD8+

The method was reported previously (19). Briefly, 8-d-cultured BMDCs were infected at 10 MOI with PR8 for 5 h and pellets were snap-frozen on dry ice. Pellets were resuspended in trifluoroacetic acid/H2O, disrupted by douncing with a glass homogenizer, further sonicated for 30 s using a microtip, and then gently mixed for 30 min at 4°C on a rotating wheel before being pelleted at 2000 rpm. The peptide-containing supernatant was further cleared of large molecules with ultracentrifugation at 27,000 rpm for 45min. Supernatants were then passed through a 3 kDa cut-off filter and dehydrated to, <400 μl in a SpeedVac. Extracted peptides were then fractionated with reverse-phase HPLC (RP-HPLC; Agilent 1100) and fractions between 10.0 and 38.8 min were collected at 6-s intervals. Elution times of synthetic peptides were determined by passing 1 μl 1 mM synthetic peptide through a RP-HPLC machine under the same running condition. To detect naturally presented peptides in the HPLC fractions, RMA-s cells were low temperature induced overnight at 26°C and pulsed (105) with either synthetic peptide at log fold dilutions or fractions for 1 h at 26°C in RPMI 1640. TCD8+ (105) were added to the pulsed RMA-s cells in RF-10 containing 10 μg/ml BFA for a further 5 h and Ag-specific TCD8+ were enumerated by ICS.

Statistical analysis

All error bars are SEM using a sample size of more than three per group.

Results

Ex vivo IAV immune response in immunoproteasome subunit-deficient mice

To better understand the contribution of immunoproteasome subunits to antiviral immunity, we studied B6 wt and knockout strains lacking one or two immunoproteasome subunits (β1i−/−, β5i/β2i−/−, and β2i−/−). Immunoproteasome subunit–deficient mice possess professional APCs expressing mixed proteasomes as shown by Western blots (data not shown), presumably very similar if not nearly identical to intermediate proteasomes (7, 20, 21). At day 7, the peak of the TCD8+ response, we analyzed local and systemic TCD8+ responses to 38 characterized H-2b–restricted peptides following i.p. PR8 infection.

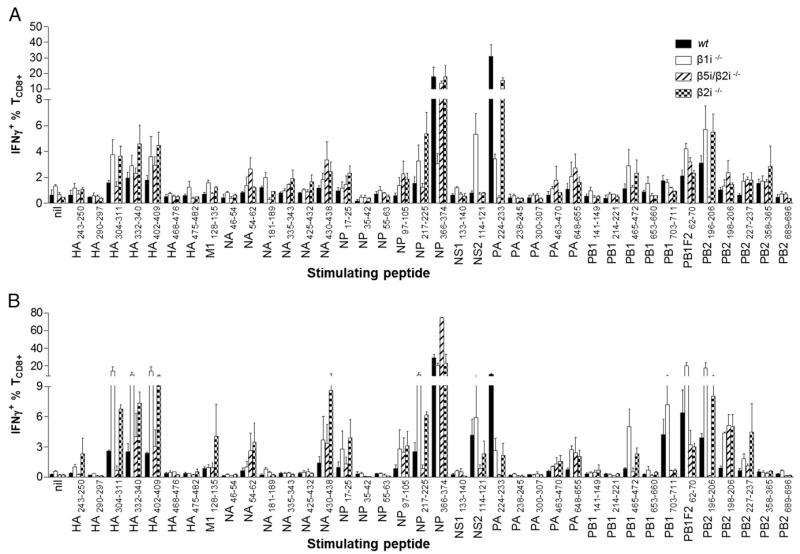

As reported, the local peritoneal response in wt mice focuses on two codominant epitopes, nucleoprotein (NP)366–374 and acidic polymerase (PA)224–233, atop reasonably robust subdominant responses to basic polymerase 1 (PB1)F262–70, Pβ1703–711, and a newly identified epitope basic polymerase 2 (PB2)196–206 (Fig. 1A and D. Zanker, J. Waithman, R. Lata, R. Murphy, and W. Chen, manuscript in preparation). Responses to other epitopes (Fig. 1A) are slightly but reproducibly above detection limits. β1i−/− mice demonstrate diminished responses, with clear alterations in the ID hierarchy. Codominant responses to PB2196-206 and nonstructural protein 2 (NS2)114–121 led subdominant responses to Pβ1F262–70, NP217–225, hemagglutinin (HA)304–311, HA402–409, along with the clearly demoted NP366–374 and PA224–233 epitopes (5, 16). β5i/β2i−/− mice exhibit NP366–374 dominance, with PA224–233 completely absent. β2i−/− mice exhibit less difference than other knockout (KO) mice, with a slightly reduced PA224–233 response (Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Loss of immunoproteasome subunits results in change of IAV ID hierarchy. β1i−/−, β5i/β2i−/−, β2i−/−, and wt mice were infected with IAV and assessed for (A) primary or (B) secondary immune responses 7 d after infection. Intraperitoneal exudates (local site of infection) were taken and TCD8+ responses measured using synthetic peptides to known IAV epitopes in an ICS assay for IFN-γ. Six mice per strain were collected individually. Data are pooled from two independent experiments.

Ranking responses to each epitope as a percentage of the total response to all epitopes tested (Supplemental Table I) reveals clear shuffling related to immunoproteasome composition. Highly similar patterns are apparent in the spleen despite a lower overall response (Supplemental Fig. 1A).

Ex vivo IAV recall response in immunoproteasome subunit–deficient mice

The ID hierarchy in recall B6 anti-IAV responses can vary significantly from primary responses (5, 22). To examine the influence of immunoproteasome subunits on recall responses, we challenged mice (>30 d after PR8 infection) with X31, a reassortant IAV with PR8 internal genes and genes encoding H3N2 glycoproteins, to avoid neutralization by anti-PR8 glycoprotein Abs (13). As above, TCD8+ in peritoneal exudates and spleen were assessed at the peak of the secondary response (day 7).

NP366–374 dominates recall responses in wt, β5i/β2i−/−, and β2i−/− strains. In β1i−/− mice, decreased responses to NP366-374 and PA224–233 occur due to decreased naive TCD8+ precursor frequencies and Ag presentation, respectively (5, 16). Concomitantly, SD responses to Pβ1F262–70 and PB2196–206 rise to codominant status, although at lower levels than NP366–374-specific response in other strains. Barely detectable responses in wt mice to HA304–311, HA332–340, HA402–409, and NP217–225 ascend to substantial SD status in β1i−/− recall responses (Fig. 1B). Conversely, among β5i/β2i−/− peritoneal responses, NP366–374-specific TCD8+ account for 75% of total anti-IAV TCD8+ (Fig. 1B; note the scale break), that is, >200% of the wt response. Curiously, this trend was reversed in splenic wt and β5i/β2i−/− TCD8+, clearly demonstrating the potential for organ and condition-specific differences in ID (Supplemental Fig. 1B). Accompanying enhanced NP366–374 responses in β5i/β2i−/− mice, responses to SDDs (HA304–311, NP217–225, NS2114–121, Pβ1703–711, and Pβ1F262–70) were reduced in absolute terms relative to responses in wt mice. This is likely due to immunodomination, the active suppression of TCD8+ specific to SDDs by those specific to IDDs (23, 24). Immunodomination was much less marked in other circumstances (Supplemental Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1B further shows the enhancement of various subdominant responses in a secondary infection in the β2i−/− strain, for example, responses to matrix protein 1 (M1)128–135, neuraminidase (NA)430–438, and PB2227–237, which were diminished to absent in other strains. These results indicate that enhanced TCD8+ responses are likely due to enhanced local Ag processing and presentation in the peritoneum for those epitopes in the absence of β2i.

Interestingly, responses to some peptides are completely absent in certain strains, such as the missing PA224–233 and PB2196–206 response in β5i/β2i−/− mice. The response to PA224–233 was not efficiently recalled in wt mice, as previously reported (13), but even less efficiently recalled in all subunit-deficient mice tested (Fig. 1B, Supplemental Fig. 1B). Similar to the primary splenic response shown in Supplemental Fig. 1A, the secondary splenic response (Supplemental Fig. 1B) is largely paralleled by the peritoneal response, in this case with less dramatic differences.

To illustrate the ID hierarchy change, the ID hierarchies of the secondary responses to IAV in the four mouse strains are displayed in Supplemental Table I and ranked according to the magnitude, as well as the relative change, in ranking between primary and secondary immune responses in the various strains.

These data clearly show that the absence of immunoproteasome subunits diversely affects the specificity and magnitude of antiviral TCD8+, often in disparate ways in local versus systemic TCD8+ populations.

Visualizing IAV-specific TCD8+ repertoire and immunoproteasome-processed IAV epitopes

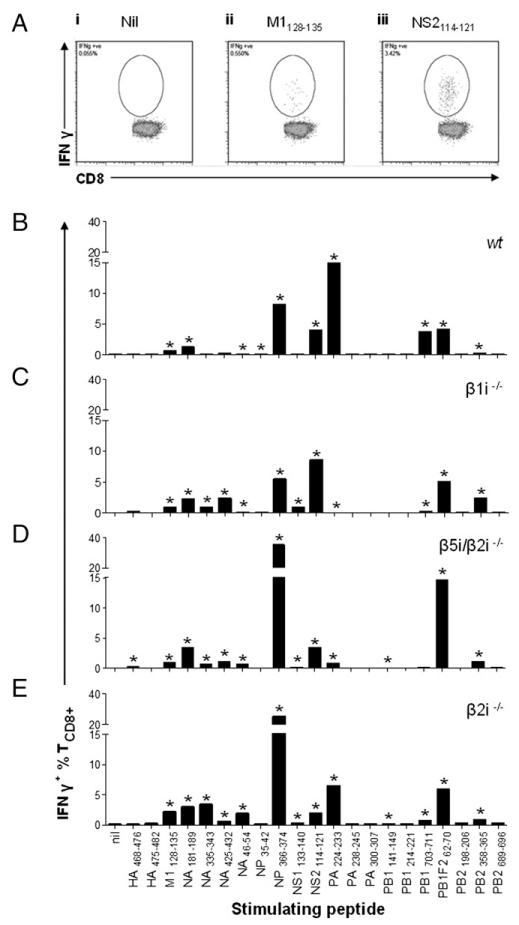

The capacity of proteasomes to generate immunogenic peptides is a major factor in ID (19). Surprisingly little is known about the influence of immunoproteasome subunits on the generation of the viral peptide repertoire in APCs or in vivo. To measure generation of a wide variety of IAV peptides we generated polyspecific T cell cultures from splenic T cells derived from wt and KO mice, taking care to stimulate TCD8+ with saturating numbers of autologous IAV-infected BMDCs to minimize immunodomination. This generated highly polyspecific cultures that matched in vivo ID hierarchies in an immunoproteasome subunit KO–specific manner, as determined with peptides corresponding to 21 IAV epitopes to quantitate TCD8+ specificities (Fig. 2). Fig. 2A shows representative clear patterns of ICS for SDD responses in the wt culture. The relatively lower total Ag-specific T cell percentage in the β1i−/− culture is partially due to the hidden PB2196–206 response (D. Zanker et al., manuscript in preparation).

FIGURE 2.

Diverse IAV responses from in vitro–expanded polyspecific IAV TCD8+ cultures derived from wt and immunoproteasome-deficient mice. (A) Representative FACS plots of subdominant TCD8+ responses from in vitro–propagated TCD8+ cultures used in Fig. 2, showing (Ai) Nil peptide, (Aii) M1128-135 peptide (baseline level subdominant response), and (Aiii)) NS2114-121 (subdominant response). (B) Wild-type, (C) β1i−/−, (D) β5i/β2i−/−, and (E) β2i−/− mice were immunized with 107 PFU PR8 i.p. Thirty days later, spleens were isolated and TCD8+ restimulated using host-strain BMDCs infected with PR8 at 10 MOI. Following 10 d culture, responses were measured using synthetic peptides to known IAV epitopes in an ICS assay measuring the production of IFN-γ. Asterisks denote when definitive TCD8+ responses were observed for the defined epitope.

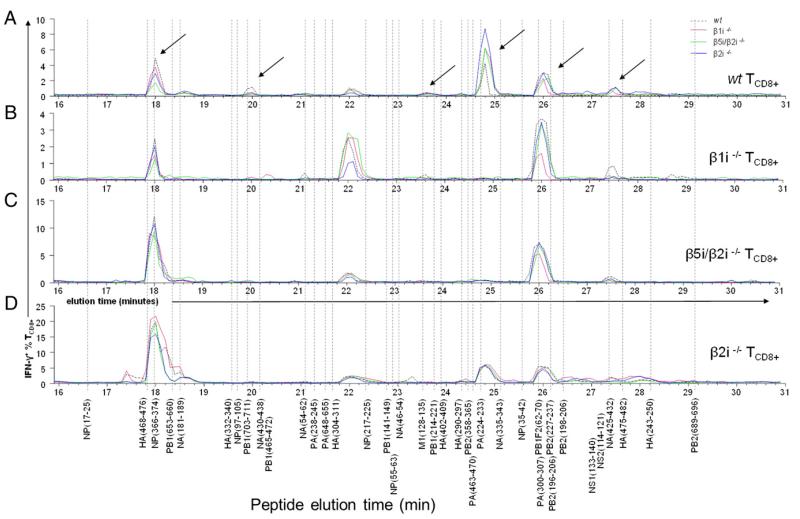

We used these polyspecific TCD8+ cultures from wt and KO mice to assess antigenic peptides present in fractions eluted from IAV-infected, immunoproteasome-competent, or subunit-deficient BMDCs and thus reveal immunoproteasome subunit–specific changes in generation of antigenic peptides and/or individual TCD8+ specificities. Plotting the data from this analysis as an “activity landscape” of percentage of IFN-γ–producing TCD8+ versus fraction number reveals clear differences associated with each KO tested (Fig. 3). Note that the height of the peaks represents mainly the abundance of TCD8+ of that specificity in the polyspecific TCD8+ culture, although it may also serve as a direct indication of peptide abundance when the peaks from different infected BMDCs vary clearly, such as those in Fig. 3A at 18 min. However, the peptide abundance is further addressed in the HPLC fraction titration experiments readout by monospecific TCD8+ cultures in Fig. 4. Also, note that there is little nonspecific TCD8+ activation for data shown in Fig. 3 judging by FACS plots of the control fractions (not shown).

FIGURE 3.

IAV-specific TCD8+ demonstrate altered IAV epitope processing by BMDCs expressing mixed proteasome. Polyspecific IAV-specific TCD8+ cultures raised from (A) wt, (B) β1i−/−, (C) β5i/β2i−/−, and (D) β2i−/− mice were restimulated using eluted HPLC fractions derived from IAV-infected BMDCs from wt (black dash), β1i−/− (pink), β5i/β2i−/− (green), or β2i−/− (dark blue) mice and assessed for the production of IFN-γ in an ICS assay. Elution time points of known synthetic IAV peptides are shown by a dotted line and the peptides are indicated below. Arrows indicate areas of interest for further investigation using monospecific IAV TCD8+ cultures.

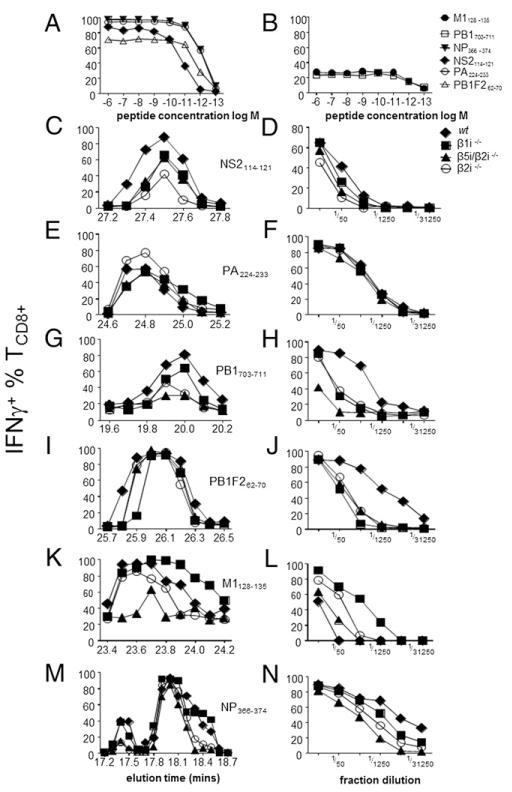

FIGURE 4.

Individual immunoproteasome subunits are critical for generation of IAV TCD8+ epitopes. (A and B) Monospecific TCD8+ cultures raised against known IAV-derived epitopes. Ten-day TCD8+ cultures were measured for purity using a titration of synthetic peptide in an ICS assay for IFN-γ. (C) NS2114–121, (E) PA224–233, (G) PB1703–711, (I) Pβ1F262–70, (K) M1128–135, and (M) NP366–374 cultures were assessed for IFN-γ production following incubation with RP-HPLC fractions of IAV-infected BMDCs from wt (◆), β1i−/− (■), β5i/β2i−/− (▲), or β2i−/− (○) mice. Peak fractions for (D) NS2114–121, (F) PA224–233, (H) Pβ1703–711, (J) Pβ1F262–70, (L) M1128–135, and (N) NP366–374 were further diluted to estimate relative peptide abundance.

Only wt and β2i−/− TCD8+ cultures contained TCD8+ activated by peptides eluting in the 24.8-min fraction, corresponding to the PA224–233 elution time (Fig. 3A, 3D; also refer to Table I for synthetic peptide elution times). Correspondingly, β5i/β2i−/− and β1i−/− polyspecific TCD8+ cultures lack detectable PA224–233-specific TCD8+. Importantly, this is not due to the inability of β5i/β2i−/− and β1i−/− cells to generate PA224–233, which is actually enhanced in all subunit-deficient relative to wt cells (Fig. 3A at 24.8 min), but instead points to immunoproteasome subunits shaping the TCD8+ repertoire.

More subtle, but still clear, β1i−/− TCD8+ exclusively detect a peak at 20.3 min (Pβ1465–472) (Fig. 3B, Supplemental Fig. 2) exclusively present in the β1i−/− fractions. Less absolutely, wt TCD8+ selectively detect activity at 19.9 min (PB1703–711) that is diminished in all fractions from all of the KO DCs. In these cases, the immunoproteasome subunits are required for peptide generation, regardless of their possible effects on the TCD8+ repertoire.

All major responses observed in the four TCD8+ activity landscapes can be attributed to previously described TCD8+ specificities with a lone exception: a major activity is detected at 22.0 min, where no known immunogenic peptide elutes (Fig. 3, Supplemental Fig. 2). This peptide is generated by all DCs, although at lower levels by β2i−/− DCs (Fig. 3B at 22.0 min, blue line); remarkably, all mice mount a similarly vigorous response (note that y-axis scales vary). Owing to the lower overall responses in β1i−/− mice, this peptide scores as an IDD.

Immunoproteasome subunits control peptide generation: biochemistry

The magnitude of each peptide-specific TCD8+ component in polyspecific TCD8+ cultures from wt versus KO mice varies dramatically. To firmly establish the basis for these observations, we directly compared the amounts of defined peptide present in each fraction by the ability of dilutions to activate TCD8+ raised to individual peptides by in vitro culture.

We focused on the six most interesting peptides identified by the TCD8+ activity landscape analysis corresponding to elution times 18.0 (NP366–374), 19.9 (PB1703–711), 23.6 (M1128–135), 24.8 (PA224–233), 26.0 (PB1F262–70) and 27.4 min (NS2114–121). All TCD8+ populations tested exhibited high sensitivities, with half-maximal responses between 10−11 and 10−12 M (Fig. 4A, 4B). None of the monospecific cultures exhibited reactivity with non-cognate major immunodominant epitopes (including NP366–374 and PA224–233; data not shown), consistent with monospecificity for their nominal peptides. We first used the monospecific cultures to show that naturally presented peptides match the elution times of the synthetic peptide (Fig. 4), providing the initial evidence that NS2114–121, PA224–233, PB1703–711, and M1128–135 are naturally generated epitopes (PB1F262–70 and NP366–374 were demonstrated in Refs. 1 and 25, respectively, to be naturally presented).

Peptide titrations of the HPLC fractions (Fig. 4, right panels) reveal clear differences bestowed by immunoproteasome subunits on Ag processing efficiency. For example, PB1703–711 (Fig. 4H) is generated 25-fold less efficiently in BMDCs lacking β1i or β2i, and nearly 125-fold less efficiently in BMDCs deficient for β5i/β2i. Loss of immunoproteasome subunits also impairs presentation of NP366–374 and Pβ1F262–70. In contrast, the absence of immunoproteasome subunits uniformly enhances M1128–135 activity (Fig. 4L).

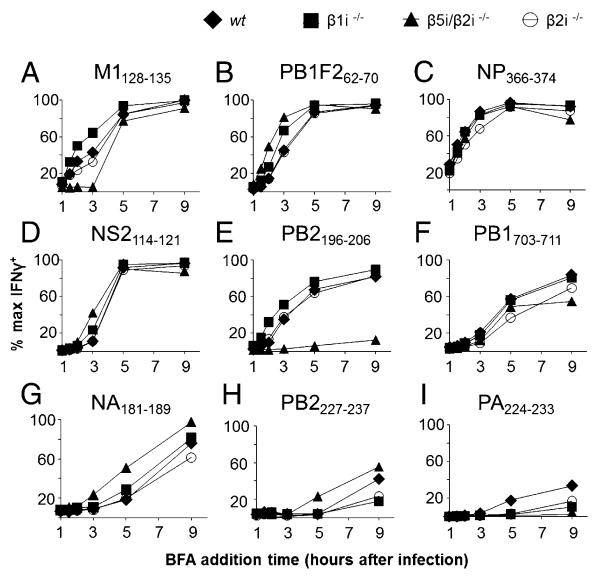

Immunoproteasome subunits control peptide generation: presentation kinetics

Although peptide recovery from cells typically requires the peptide to be protected by MHC class I molecules (26), there are exceptions to this rule (27). To more firmly establish the role of immunoproteasome subunits in directly altering the presented IAV peptide repertoire, we examined the kinetics of peptide presentation. We infected DCs from wt and KO mice with IAV and examined their capacity to activate nine single specificity TCD8+ cultures (characterized in Supplemental Fig. 3) at various times after infection by adding BFA to block delivery of peptide class I complexes to the cell surface (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 5.

The Ag presentation of specific epitopes is altered by APCs with different protein degradation machinery. BMDCs from β1i−/− (■), β5i/β2i−/− (▲), β2i−/− (○), and wt (◆) mice were infected with IAV at an MOI of 10. Following 60 min infection (indicated as 1 h in the figures), cells were washed and incubated with monospecific TCD8+ cultures specific to defined IAV epitopes, (A) M1128–135, (B) PB1F262–70, (C) NP366-374, (D) NS2114–121, (E) PB2196–206, (F) PB1703–711, (G) NA181–189, (H) PB2227–237, and (I) PA224–233. BFA was added for a total of 4 h at the indicated time points and recognition of naturally presented peptide was measured using ICS assay for IFN-γ.

In all APCs tested, the NP366–374 epitope is presented most efficiently and is detectably presented at the cell surface even 1 h after infection. The M1128–135 peptide is also presented rapidly, with a slight enhancement in BMDCs lacking the β1i subunit (Fig. 5A, Supplemental Fig. 3D). The PB1F262–70 peptide shows enhanced presentation in BMDCs lacking the β5i or β1i subunit compared with β2i−/− and wt BMDCs (Fig. 5B). The NS2114–121, PB2196–206, and PB1703–711 epitopes are presented with medium kinetics (Fig. 5D-F). In the absence of both the β5i and β2i subunits, PB2196–206 presentation is nearly absent (Fig. 5E). Conversely, PB2196–206 presentation is enhanced in the absence of β1i. The NA181–189, PB2227–237, and PA224–233 epitopes are presented with overall slower kinetics (Fig. 5G-I). The NA181–189 and PB2227–237 presentation kinetics are slightly enhanced in the absence of the β5i and β2i subunits.

Finally, and most remarkably, PA224–233 presentation is the slowest and requires a complete immunoproteasome for most efficient presentation (Fig. 5I). The slow presentation is in stark contrast to the clear abundance of the peptide in cell lysates, and, as discussed below, extends the findings of Lev et al. (27) made with minigene products to physiological Ag processing.

Taken together, these findings demonstrate that knocking out individual proteasome subunits greatly influences ID to IAV by modulating the repertoire of responding TCD8+ and by modulating the specificity of peptide generation. These findings strongly imply that mixed proteasomes function to diversify the antiviral repertoire.

Discussion

In this study, we provide the most comprehensive study to date of ID in an animal model system: we characterize the primary and recall B6 TCD8+ responses to 38 defined IAV determinants (Immune Epitope Database, http://www.iedb.org/). Most of these determinants were predicted through computer algorithms based on class I binding and proteasome cleavage motifs and were assessed by class I binding and T cell activation (2, 28, 29). For four of these peptides we provide the initial evidence that they are naturally processed by IAV-infected cells, as determined by the coelution of synthetic peptides. For five of these peptides, we further show that T cells raised to the peptides recognize infected cells. This falls just short of the ultimate confirmation of epitope immunogenicity, which entails correlating lost peptide reactivity of antiviral T cells following infection with virus mutated to eliminate peptide binding to the restricting class I molecules (30).

To our knowledge, this study provides the first comprehensive analysis of the ability of mixed proteasomes to generate a large panel of viral peptides. We use polyspecific anti-IAV TCD8+ cultures from immunoproteasome subunit KO mice to assess the peptides generated by IAV-infected BMDCs from these strains. This revealed subunit-specific shuffling of ID hierarchies including the enormous secondary response to PB2196–206 in the β1i−/− strain, as well as enhanced responses to PB2196–206, M1128–135, and Pβ1465–472 in mice lacking immunoproteasome subunits. Some of the effects can be attributed to differences in repertoire, whereas others are clearly related to differences in peptide generation as shown both biochemically by peptide isolation and functionally by measuring presentation kinetics of infected cells. These findings point to a major contribution of mixed proteasomes to ID, and they raise the important issue of reconciling our findings with recently described triple immunoproteasome KO mice, which are incapable of generating mixed proteasomes (6).

The difference in activated naive and memory TCD8+ effector function likely contributes to the changes in primary versus recall ID hierarchies. Naive TCD8+ take days to kill following activation whereas memory TCD8+ kill within hours (31) and could kill APCs quickly (11, 32). Rapid APC depletion could increase TCD8+ competition for APCs, favoring proliferation of TCD8+-targeting epitopes with faster presentation kinetics. Competition in recall immune responses has been demonstrated previously, although only with comparison of a limited number of epitopes (10). Our results indicate that ID hierarchy to nine epitopes in a recall response largely correlates to the particular presentation kinetics, arguing strongly for this being an important factor in establishing recall ID hierarchies.

The strength of our biochemical approach is illustrated by several findings. First, we detect a major response in all strains examined to an undefined IAV peptide eluting at 22.0 min in HPLC analysis. It should be possible in future studies to identify the peptide either directly by mass spectrometry or by traditional genetic mapping, starting with individual IAV gene products and truncating genes until the peptide can be pinpointed, aided by algorithms.

Second, we show a remarkable disconnect between the amounts of peptides recovered from infected cells and their kinetics of presentation. The influence of immunoproteasome subunits on peptide presentation and recovery is summarized in Table II, in which APC data from KO mice are shown as the percentage of data from wt APCs. Calculating the ratio of peptide recovery percentage to BFA kinetics percentage revealed a number of striking discrepancies. Setting a 10-fold difference as clearly significant, the HPLC assay underestimates the kinetics of presentation of PB1703–711 in all KO APCs and PB1F262–70 and NP366–374 in β5i/β2i KO APCs. Conversely, M1128–135 is recovered at higher levels in β1i and β2i KO APCs than predicted by kinetics.

Table II.

Comparison of epitope presentation assessed by HPLC elution and BFA kinetics

| Epitope | β1i−/− |

β5i/β2i −/− |

β2i −/− |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC (%) | BFA (%) | Ratio | HPLC (%) | BFA (%) | Ratio | HPLC (%) | BFA (%) | Ratio | |

| NP366–374 | 40 | 67 | 4 | 67 | 0.06 | 8 | 50 | ||

| PA224–233 | 90 | 29 | 90 | 11 | 100 | 50 | |||

| PB1703–711 | 5 | 100 | 0.05 | 1 | 88 | 0.01 | 5 | 58 | 0.09 |

| PB1F262–70 | 4 | 15 | 8 | 225 | 0.04 | 12 | 100 | ||

| M1128–135 | 2500 | 225 | 12 | 300 | 69 | 1000 | 90 | 11 | |

| NS2114–121 | 75 | 120 | 50 | 133 | 25 | 120 | |||

Peptide production and presentation of six IAV Tcd8+ epitopes were measured from wt, (β1i−/−, (β5i/β2i−/−, and β2i−/− BMDCs and quantified relative to wt half maximal results (which were considered as 100%). Any difference >10-fold between the HPLC fraction titration and BFA kinetics assessment for the same epitope is shown in boldface italic type.

There are several potential explanations for these discrepancies. First, the BFA assay is much better suited for studying epitopes such as PB1703–711, PA224–233, and NA181–189 whose slow presentation is more likely to linearly reflect the generation of peptide class I complexes than for rapidly presented epitopes such as NP366–374 and PB1F262–70, which rapidly saturate T cell activation. Second, M1128–135 showed an unusually wide elution peak (Fig. 4K), consistent with structural heterogeneity of the epitope that T cells might not distinguish, whereas we only measured peptide in the peak fraction. Third, and most importantly, HPLC elution experiments might be biased by intracellular peptide pools that form independently of their cognate class I molecule and therefore do not truly represent presented molecules.

The pioneering work of Rammensee and colleagues (25) established that antigenic peptide recovery is dependent on the presence of MHC class I molecules, presumably owing to their rapid destruction by proteasomes and many other cytosolic and endoplasmic reticulum proteases. But how general is this rule? We previously reported that PA224–233 when expressed as a vaccinia virus-expressed minigene product forms a large intracellular pool independently of class I. Indeed, the pool was rather dependent on active heat shock protein (HSP)90, likely through binding to a HSP90-dependent client because we could not directly demonstrate association of PA224–233 with HSP90 (27).

In this study we provide the initial evidence that PA224–233 naturally generated from an IAV infection may form a large class I-independent pool, because its recovery from APCs is completely independent of its presentation kinetics. Class I–independent pools could also explain the clear discrepancy in PB1703–711 recovery from wt versus KO APCs if only complete immunoproteasomes can generate peptides that populate the class I–independent pool. Although this idea may seem far-fetched, peptide generation can be complex, with different rules, for example, applying to ostensibly identical proteins encoded by viral versus cell mRNA as well as defective ribosomal products versus retirees, and even within retiree subsets (33). The possibility must be entertained that even identical peptides generated by different sorts of proteasomes may have different fates.

Although our experiments do not differentiate direct priming versus cross-priming, an exciting implication of cytosolic pools of PA224–233 in IAV-infected cells is that its robust immunogenicity in primary responses might reflect the importance of cross-priming in activating naive anti-IAV TCD8+. Lev et al. (27) showed that unlike other peptides, owing to its cytosolic pool, PA224–233 was potently cross-presented and could prime TCD8+ responses. Could it be that PA224–233 dominates primary responses due to the importance of cross-priming in this process along with an advantage of PA224–233 in cross-priming due to its stable pool? Conversely, the loss of ID status in secondary responses implies that direct presentation may play a more important role in the recall response.

The discrepancies we observe between the generation of PA224–233 (and other peptides in an immunoproteasome subunit–dependent manner) and their presentation kinetics and ID provide a launching point for future studies on the exact contribution of direct versus cross-presentation in IAV and other infectious models, and despite intense research during the last three decades, remains a central issue for understanding ID and rational vaccine design.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Stephen Turner (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University of Melbourne) for reading the manuscript and for sharing reagents.

This work was supported in part by National Health and Medical Research Council Project Grants 433608 and 542508 (to W.C.) and by National Health and Medical Research Council Program Grant 567122. D.Z. was supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Biomedical Postgraduate Scholarship 487926. J.W. is a National Health and Medical Research Council Biomedical Training Fellow (Grant 603100), and W.C. is a National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellow (Grant 603104).

Glossary

Abbreviations used in this article

- B6

C57BL/6

- BFA

brefeldin A

- BMDC

bone marrow–derived dendritic cell

- DC

dendritic cell

- HA

hemagglutinin

- IAV

influenza A virus

- ICS

intracellular cytokine staining

- ID

immunodominance

- IDD

immunodominant determinant

- KO

knockout

- M1

matrix protein 1

- MOI

multiplicity of infection

- NA

neuraminidase

- NP

nucleoprotein

- NS2

nonstructural protein 2

- PA

acidic polymerase

- PB1

basic polymerase 1

- PB2

basic polymerase 2

- RP-HPLC

reverse-phase HPLC

- SDD

subdominant determinant

- TCD8+

CD8+ T cell

- wt

wild-type.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Chen W, Calvo PA, Malide D, Gibbs J, Schubert U, Bacik I, Basta S, O’Neill R, Schickli J, Palese P, et al. A novel influenza A virus mitochondrial protein that induces cell death. Nat. Med. 2001;7:1306–1312. doi: 10.1038/nm1201-1306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhong W, Reche PA, Lai CC, Reinhold B, Reinherz EL. Genome-wide characterization of a viral cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope repertoire. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:45135–45144. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Treanor JJ, Campbell JD, Zangwill KM, Rowe T, Wolff M. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated subvirion influenza A (H5N1) vaccine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;354:1343–1351. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Groettrup M, Soza A, Kuckelkorn U, Kloetzel PM. Peptide antigen production by the proteasome: complexity provides efficiency. Immunol. 1996;17:429–435. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(96)10051-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen W, Norbury CC, Cho Y, Yewdell JW, Bennink JR. Immunoproteasomes shape immunodominance hierarchies of antiviral CD8+ T cells at the levels of T cell repertoire and presentation of viral antigens. J. Exp. Med. 2001;193:1319–1326. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kincaid EZ, Che JW, York I, Escobar H, Reyes-Vargas E, Delgado JC, Welsh RM, Karow ML, Murphy AJ, Valenzuela DM, et al. Mice completely lacking immunoproteasomes show major changes in antigen presentation. Nat. Immunol. 2012;13:129–135. doi: 10.1038/ni.2203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guillaume B, Chapiro J, Stroobant V, Colau D, Van Holle B, Parvizi G, Bousquet-Dubouch MP, Théate I, Parmentier N, Van den Eynde BJ. Two abundant proteasome subtypes that uniquely process some antigens presented by HLA class I molecules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2010;107:18599–18604. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009778107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crowe SR, Turner SJ, Miller SC, Roberts AD, Rappolo RA, Doherty PC, Ely KH, Woodland DL. Differential antigen presentation regulates the changing patterns of CD8+ T cell immunodominance in primary and secondary influenza virus infections. J. Exp. Med. 2003;198:399–410. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen W, Masterman KA, Basta S, Haeryfar SM, Dimopoulos N, Knowles B, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Cross-priming of CD8+ T cells by viral and tumor antigens is a robust phenomenon. Eur. J. Immunol. 2004;34:194–199. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.La Gruta NL, Kedzierska K, Pang K, Webby R, Davenport M, Chen W, Turner SJ, Doherty PC. A virus-specific CD8+ T cell immunodominance hierarchy determined by antigen dose and precursor frequencies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2006;103:994–999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0510429103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kedl RM, Rees WA, Hildeman DA, Schaefer B, Mitchell T, Kappler J, Marrack P. T cells compete for access to antigen-bearing antigen-presenting cells. J. Exp. Med. 2000;192:1105–1113. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.8.1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kedl RM, Schaefer BC, Kappler JW, Marrack P. T cells down-modulate peptide-MHC complexes on APCs in vivo. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:27–32. doi: 10.1038/ni742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen W, Pang K, Masterman KA, Kennedy G, Basta S, Dimopoulos N, Hornung F, Smyth M, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Reversal in the immunodominance hierarchy in secondary CD8+ T cell responses to influenza A virus: roles for cross-presentation and lysis-independent immunodomination. J. Immunol. 2004;173:5021–5027. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.5021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robek MD, Garcia ML, Boyd BS, Chisari FV. Role of immunoproteasome catalytic subunits in the immune response to hepatitis B virus. J. Virol. 2007;81:483–491. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01779-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deol P, Zaiss DM, Monaco JJ, Sijts AJ. Rates of processing determine the immunogenicity of immunoproteasome-generated epitopes. J. Immunol. 2007;178:7557–7562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pang KC, Sanders MT, Monaco JJ, Doherty PC, Turner SJ, Chen W. Immunoproteasome subunit deficiencies impact differentially on two immunodominant influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses. J. Immunol. 2006;177:7680–7688. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pang KC, Wei JQ, Chen W. Dynamic quantification of MHC class I-peptide presentation to CD8+ T cells via intracellular cytokine staining. J. Immunol. Methods. 2006;311:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zanker D, Xiao K, Oveissi S, Guillaume P, Luescher IF, Chen W. An optimized method for establishing high purity murine CD8+ T cell cultures. J. Immunol. Methods. 2013;387:173–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2012.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen W, Antón LC, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. Dissecting the multifactorial causes of immunodominance in class I-restricted T cell responses to viruses. Immunity. 2000;12:83–93. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De M, Jayarapu K, Elenich L, Monaco JJ, Colbert RA, Griffin TA. β2 subunit propeptides influence cooperative proteasome assembly. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:6153–6159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209292200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hensley SE, Zanker D, Dolan BP, David A, Hickman HD, Embry AC, Skon CN, Grebe KM, Griffin TA, Chen W, et al. Unexpected role for the immunoproteasome subunit LMP2 in antiviral humoral and innate immune responses. J. Immunol. 2010;184:4115–4122. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomas PG, Brown SA, Keating R, Yue W, Morris MY, So J, Webby RJ, Doherty PC. Hidden epitopes emerge in secondary influenza virus-specific CD8+ T cell responses. J. Immunol. 2007;178:3091–3098. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.5.3091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yewdell JW, J R. Bennink. Immunodominance in major histo-compatibility complex class I-restricted T lymphocyte responses. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1999;17:51–88. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.17.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen W, McCluskey J. Immunodominance and immunodomination: critical factors in developing effective CD8+ T-cell-based cancer vaccines. Adv. Cancer Res. 2006;95:203–247. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(06)95006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rötzschke O, Falk K, Deres K, Schild H, Norda M, Metzger J, Jung G, Rammensee HG. Isolation and analysis of naturally processed viral peptides as recognized by cytotoxic T cells. Nature. 1990;348:252–254. doi: 10.1038/348252a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen W, Yewdell JW, Levine RL, Bennink JR. Modification of cysteine residues in vitro and in vivo affects the immunogenicity and antigenicity of major histocompatibility complex class I-restricted viral determinants. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:1757–1764. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lev A, Takeda K, Zanker D, Maynard JC, Dimberu P, Waffarn E, Gibbs J, Netzer N, Princiotta MF, Neckers L, et al. The exception that reinforces the rule: crosspriming by cytosolic peptides that escape degradation. Immunity. 2008;28:787–798. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vitiello A, Yuan L, Chesnut RW, Sidney J, Southwood S, Farness P, Jackson MR, Peterson PA, Sette A. Immunodominance analysis of CTL responses to influenza PR8 virus reveals two new dominant and subdominant Kb-restricted epitopes. J. Immunol. 1996;157:5555–5562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sigal LJ, Goebel P, Wylie DE. Db-binding peptides from influenza virus: effect of non-anchor residues on stability and immunodominance. Mol. Immunol. 1995;32:623–632. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(95)00031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yewdell JW. The seven dirty little secrets of major histocompatibility complex class I antigen processing. Immunol. Rev. 2005;207:8–18. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lalvani A, Brookes R, Hambleton S, Britton WJ, Hill AV, McMichael AJ. Rapid effector function in CD8+ memory T cells. J. Exp. Med. 1997;186:859–865. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.6.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Belz GT, Zhang L, Lay MD, Kupresanin F, Davenport MP. Killer T cells regulate antigen presentation for early expansion of memory, but not naive, CD8+ T cell. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:6341–6346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609990104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dolan BP, Sharma AA, Gibbs JS, Cunningham TJ, Bennink JR, Yewdell JW. MHC class I antigen processing distinguishes endogenous antigens based on their translation from cellular vs. viral mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:7025–7030. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1112387109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.