Abstract

Alveolar epithelial type II (ATII) cells are essential for maintaining normal lung homeostasis because they produce surfactant, express innate immune proteins, and can function as progenitors for alveolar epithelial type I (ATI) cells. Although autocrine production of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 has been shown to promote the transdifferentiation of primary rat ATII to ATI cells in vitro, mechanisms controlling this process still remain poorly defined. Here, evidence is provided that Tgf-β1, -2, -3 mRNA and phosphorylated SMAD2 and SMAD3 significantly increase as primary cultures of mouse ATII cells transdifferentiate to ATI cells. Concomitantly, bone morphogenetic protein (Bmp)-2 and -4 mRNA, and phosphorylated SMAD1/5/8 expression decrease. Exogenously supplied recombinant human TGF-β1 inhibited BMP signaling and enhanced transdifferentiation by promoting the loss of ATII cell-specific gene expression and weakly stimulating ATI cell-specific gene expression. On the other hand, exogenously supplied recombinant human BMP-4 inhibited TGF-β signaling and delayed transdifferentiation by inhibiting the gain in ATI cell-specific gene expression and weakly delaying the loss of ATII cell-specific gene expression. In mouse lung epithelial (MLE15) cells, small-interfering RNA (siRNA) knockdown of TGF-β receptor type-1 enhanced basal expression of ATII genes while siRNA RNA knockdown of BMP receptors type-1a and -1b enhanced basal expression of ATI genes. Together, these results suggest that the rate of ATII cell transdifferentiation is controlled by the opposing actions of BMP and TGF-β signaling that switch during the process of transdifferentiation.

Keywords: bone morphogenetic protein, epithelium, transforming growth factor-β

alveoli of the mammalian lung contain two populations of epithelial cells that must work coordinately to provide constant and efficient gas exchange. Alveolar epithelial type I (ATI) cells are large squamous cells that cover 95–99% of the alveolar surface (41). They exchange oxygen and carbon dioxide between the airspace and the underlying microcapillaries and express transport proteins that maintain fluid homeostasis (12). Alveolar epithelial type II (ATII) cells are cuboidal cells that produce pulmonary surfactant and molecules involved in host defense (19). Tritiated thymidine studies in animals injured by oxidant gases have shown how they can also self-renew and transdifferentiate into ATI cells (1, 18, 44). Transdifferentiation also occurs when freshly isolated cultures of ATII cells assume an ATI-like phenotype, defined by the appearance of a flattened polygonal morphology, transport properties, and expression of ATI-specific genes such as T1α and aquaporin 5 (Aqp5) (5, 6, 15). Growth factors and matrix components affect this process. Autocrine production of transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 promotes transdifferentiation while keratinocyte growth factor (KGF) preserves rat ATII phenotype (3, 7). Treatment of human fetal lung epithelial cells with glucocorticoid and cAMP analogs promotes ATII phenotype (47). Culturing on floating collagen gels, matrigel, or at an air-liquid interface maintains rat or human ATII cell phenotype while culturing on laminin 5 can enhance the transport properties seen in mouse ATI cells (13, 15, 16, 39). ATI-like cells can revert to ATII phenotype when cultured with KGF, by detaching the collagen gel or by returning to an air-liquid interface (7, 13, 38). Moreover, primary cultures of rat ATI cells can proliferate and express ATII or airway epithelial cell genes when cultured on matrigel (22). While the reversibility of ATI to ATII cells still needs to be confirmed in vivo, these and other studies suggest there is remarkable plasticity between these two populations of alveolar epithelial cells.

Transdifferentiation of ATII to ATI cells may represent a default or primary pathway because it occurs spontaneously in primary culture. Since this process is driven in part by the autocrine production of TGF-β1 (3), other intrinsic signaling molecules may exist to maintain ATII cell phenotype, perhaps by impeding TGF-β signaling. Such inhibitory signals are predicted to be lost during the process of transdifferentiation. TGF-β1 is one of three members (TGF-β1, TGF-β2, TGF-β3) of a larger family of extracellular proteins that includes the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP), the growth and differentiation factor, and the activin/nodal/anti-mullerian hormone family (for review, see Ref. 32). All family members bind to distinct type 2 receptors, which dimerize with two or more specific type 1 receptors, thereby creating an active receptor that stimulates intracellular signaling pathways through serine/threonine phosphorylation. The receptor-dependent phosphorylation of SMAD proteins represents the primary pathway activated by these ligands. The TGF-βs stimulate phosphorylation of SMADs 2 and 3 while the BMPs phosphorylate SMADs 1, 5, and 8. Consequentially two different signaling effects are generated when these receptor-regulated (R)-SMADs are escorted by SMAD4, a partner SMAD, into the nucleus to function as transcription factors, activating or inhibiting distinct sets of genes. Activated TGF-β/BMP signaling can inhibit their own signaling and that of each other. For example, TGF-β can inhibit its own pathway through the activation of inhibitory SMAD6 and SMAD7, which block interactions between the R-SMADs and type 1 receptor, respectively (40). On the other hand, BMP signaling can inhibit TGF-β signaling, such as when BMP-7 antagonizes the profibrogenic activity of TGF-β in mouse pulmonary myofibroblastic cells (25). Conversely, mutations in BMP receptor type 2 (BMPR2) gene lead to exaggerated TGF-β signaling in pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells and increase the susceptibility to pulmonary hypertension (33). Thus, there is extensive cross talk between members of the TGF-β/BMP superfamily that control cell function.

A recent study found that cultured mouse ATII cells actively absorb sodium ions but, in contrast to rat and human ATII cells, required laminin 5 to achieve sufficient barrier function (15). This suggests observations made in one species may not always extrapolate to others and therefore emphasizes the importance of evaluating signaling systems in more than one species. Most studies have used rat and human ATII cells because they are easier to isolate and culture than mouse ATII cells. Fortunately, a reliable method for isolating mouse ATII cells has been established (11), which provided the opportunity to determine whether TGF-β signaling shown to promote transdifferentiation of rat ATII cells also occurs in mice. Here, we provide evidence that opposing TGF-β/BMP signaling controls the transdifferentiation rate of mouse ATII cells in vitro.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Wild-type C57BL/6 mice used in this study were 8 to 10 wk old. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Rochester Medical Center approved all experiments described in this study.

Materials.

Dispase, biotin anti-mouse CD45, and biotin anti-mouse CD16/CD32 were purchased from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). BioMag streptavidin was obtained from QIAGEN (Germantown, MD). Anti-SMAD1, anti-SMAD2, anti-SMAD3, anti-SMAD5, anti-phospho-SMAD1/5/8, anti-phospho-SMAD2, and anti-phospho-SMAD3 antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA). Anti-proSFTPC antibody was purchased from Millipore (Billerica, MA). Anti-T1α antibody was obtained from Iowa Hybridoma Bank. Anti-β-actin antibody was purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). FITC-donkey-anti-rabbit secondary and Texas Red-goat-anti-hamster secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories (West Grove, PA). Vectorshield mounting medium for fluorescence was purchased from Vector Laboratories (Burlingame, CA). Recombinant human TGF-β1 and BMP-4 were obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN).

Isolation and culture of mouse primary ATII cells and MLE15 cells.

Mouse ATII cells were isolated from adult C57BL/6 mice using dispase with agarose instillation, filtration, and then immunodepletion of CD16/CD32 and CD45 (11). Cells were then cultured on tissue culture plastic for 6 h to deplete mesenchymal cells. The nonadherent ATII cells were harvested as day 0 samples or stimulated to undergo transdifferentiation by plating on tissue culture plastic in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). For some experiments, cells were cultured in the absence or presence of human (h) TGF-β1 (4 ng/ml) or hBMP-4 (200 ng/ml) purchased from R & D Systems.

MLE15 cells were derived from transgenic mice expressing simian large and small t antigen under control of the human surfactant protein C (Sftpc) gene (49). The cells were incubated at 37°C in 5% CO2 in Dulbecco's Modified Eagles and F-12 medium with 10% FBS. Cells were transfected with 50 nM small-interfering RNA (siRNA) oligonucleotides targeting TGF-βR1 (GAAGUUAAGGCCAAAUAUU), BMPR1A (CAGCUAUACACUUACAUCA), and BMPR1B (CCAAGAUCCUACGUUGUAA) purchased from Sigma. BMPR1A and BMPR1B siRNAs were transfected together at the concentration of 25 nM each. AllStars Negative Control siRNA (Qiagen) was used at the concentration of 50 nM as nontargeting control. Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) was used for siRNA transfection according to the manufacturer's instruction. Two days after transfection, cells were harvested for quantitative real-time PCR and Western blotting.

Immunofluorescence.

Freshly isolated ATII cells were centrifuged on slides as day 0. ATII cells cultured in a 1:1 mixture of DMEM and Ham's F-12 Nutrient Mixture on chamber slides for 1 day were considered as day 1 cells. ATII cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS on chamber slides for other time points. Slides were washed with 1× PBS after removal of the culture medium and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min followed by washes of 1× PBS. The slides were then stored in 1× PBS at 4°C until the day of staining. Slides were treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 min, blocked with serum at room temperature for 1 h, and then incubated with primary antibodies at 4°C overnight. Immune complexes were captured with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies before slides were counterstained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole. Stained slides were visualized with a fluorescence microscope (model E800; Nikon Instruments), and images were captured with a digital camera (SPOT-RT; Diagnostic Instruments, Sterling Heights, MI).

RNA isolation and quantitative real-time PCR.

Total RNA was prepared using the RNeasy Mini Kit (QIAGEN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. cDNAs were synthesized using the iSCRIPT cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Quantitative Real-Time PCR amplifications were performed in a CFX96 Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) using iQ SYBR Green supermix (Bio-Rad). 18s rRNA was used as an internal control. Each sample was prepared in triplicate, and samples prepared from at least three times of different experiments were detected. Representative data are presented as means ± SD of the triplicates. The sequences of primer sets used are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used in the quantitative real-time PCR

| Genes | Sequences of Primers | GenBank Accession No. | Product Sizes, bp |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sftpa | F: 5′ TTCCAGGGTTTCCAGCTTACCT 3′ | NM_023134.4 | 156 |

| R: 5′ AGTTGACTGACTGCCCATTGGT 3′ | |||

| Sftpb | F: 5′ TGGAACACCAGTGAACAGGCTA 3′ | NM_147779.1 | 103 |

| R: 5′ GCATGTGCTGTTCCACAAACTG 3′ | |||

| Sftpc | F: 5′ TGATGGAGAGTCCACCGGATTA 3′ | NM_011359.2 | 130 |

| R: 5′ CCTACAATCACCACGACAACGA 3′ | |||

| T1α | F: 5′ AGCAAAGCCAAGACAGTATCGC 3′ | NM_010329.2 | 179 |

| R: 5′ TTAGGACTGGGCTGGAATGTGT 3′ | |||

| Aqp5 | F: 5′ AGATCTCCATAGCCTTTGGCCT 3′ | NM_009701.4 | 124 |

| R: 5′ AGCAGAGAGATCTGGTTGCCTA 3′ | |||

| Tgf-β1 | F: 5′ TACGTCAGACATTCGGGAAGCA 3′ | NM_011577.1 | 138 |

| R: 5′ AGGTAACGCCAGGAATTGTTGC 3′ | |||

| Tgf-β2 | F: 5′ GCCTTCGCCCTCTTTACATTGA 3′ | NM_009367.3 | 174 |

| R: 5′ CGGAAGCTTCGGGATTTATGGT 3′ | |||

| Tgf-β3 | F: 5′ CCTGGCCCTGCTGAACTTG 3′ | NM_009368.3 | 75 |

| R: 5′ TTGATGTGGCCGAAGTCCAAC 3′ | |||

| BMP-2 | F: 5′ CACACAGGGACACACCAACC 3′ | NM_007553.2 | 99 |

| R: 5′ CAAAGACCTGCTAATCCTCAC 3′ | |||

| BMP-4 | F: 5′ CGTCATTCCGGATTACATGAGGGA 3′ | NM_007554.2 | 165 |

| R: 5′ CCTGGGATGTTCTCCAGATGTTCT 3′ | |||

| Smad1 | F: 5′ ACCCCTACCACTATAAGCGAG 3′ | NM_008539.3 | 166 |

| R: 5′ TGCTGGAAAGAGTCTGGGAAC 3′ | |||

| Smad2 | F: 5′ ATGTCGTCCATCTTGCCATTC 3′ | NM_010754.4 | 173 |

| R: 5′ AACCGTCCTGTTTTCTTTAGCTT 3′ | |||

| Smad3 | F: 5′ CACAGCCACCATGAATTACGG 3′ | NM_016769.4 | 108 |

| R: 5′ TGGCGTCTCTACTCTCTGATAGT 3′ | |||

| Smad5 | F: 5′ TTGTTCAGAGTAGGAACTGCAAC 3′ | NM_001164042.1 | 114 |

| R: 5′ GAAGCTGAGCAAACTCCTGAT 3′ | NM_001164041.1; NM_008541.3 | ||

| Tgfbr1 | F: 5′ AAAACAGGGGCAGTTACTACAAC 3′ | NM_009370.2 | 188 |

| R: 5 ′ TGGCAGATATAGACCATCAGCA 3′ | |||

| Tgfbr2 | F: 5′ AACATGGAAGAGTGCAACGAT 3′ | NM_029575.3; NM_009371.3 | 90 |

| R: 5′ CGTCACTTGGATAATGACCAACA 3′ | |||

| Bmpr1a | F: 5′ GGCCATTGCTTTGCCATTATAG 3′ | NM_009758.4 | 109 |

| R: 5 ′ CTTTCGGTGAATCCTTGCATTG 3′ | |||

| Bmpr1b | F: 5′ CCCTCGGCCCAAGATCCTA 3′ | NM_007560.3 | 128 |

| R: 5′ CAACAGGCATTCCAGAGTCATC 3′ | |||

| 18s | F: 5′ CGGCTACCACATCCAAGGAA 3′ | NR_003278.1 | 187 |

| R: 5′ GCTGGAATTACCGCGGCT 3′ |

Sftp, surfactant protein; Aqp5, aquaporin 5; Tgf, transforming growth factor; BMP, bone morphogenetic protein; Tgfbr, TGF-β receptor; Bmpr, BMP receptor; F, forward primer; R, reverse primer.

Western blotting.

Whole cell lysates for Western blotting were extracted with lysis buffer containing 50 mM Tris (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, and 0.5% Nonidet P-40 and protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma). Total protein was measured using the BCA protein assay reagent kit (Pierce, Rockford, IL). Protein samples were resolved by 15% (for proSFTPC) or 10% SDS-PAGE and transferred to the polyvinylidene difluoride membranes, which were incubated with individual antibodies according to the manufacturer's instructions and then incubated with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (SouthernBiotech, Birmingham, AL). The blots were visualized by an enhanced chemiluminesence system (ECL kit; GE Lifesciences, Piscataway, NJ) according to the manufacturer's protocol.

Statistical analyses.

Data are presented as means ± SD, and all experiments were performed at least three times with similar results. Statistical analyses were performed with Stat view statistical software (SAS, Cary, NC). Differences between the two groups were compared using unpaired Student's t-test, whereas more than two groups were compared using one-way ANOVA, followed by a Bonferroni/Dunnett's test. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

RESULTS

Mouse ATII cells spontaneously transdifferentiate to ATI cells in primary culture.

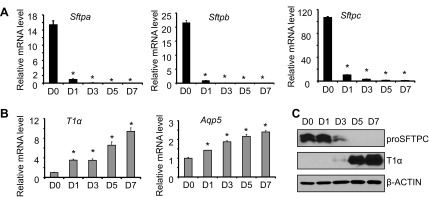

Mouse ATII cells were isolated and stimulated to undergo transdifferentiation by culturing for 7 days on tissue culture plastic. The mRNA loss of surfactant-associated protein (Sftp) expressed by ATII cells (Sftpa, Sftpb, and Sftpc) and gain of mRNAs expressed by ATI cells (T1α and Aqp5) were used to follow transdifferentiation. The purity of freshly isolated ATII cells, defined by immunostaining for proSFTPC, was typically >95% with a yield of 3–4 × 106 cells/mouse, and viability was >98% based upon Trypan blue dye exclusion (data not shown). Sftpa, Sftpb, and Sftpc mRNAs were readily detected on the day of isolation (day 0), reduced by day 1 of culture, and barely detectable by day 3 or beyond (Fig. 1A). Expression of T1α and Aqp5 mRNA was low on day 0, elevated by day 1, and progressively increased through day 7 (Fig. 1B). The loss of ATII and gain in ATI-specific genes were confirmed by blotting cell lysates with antibody against proSFTPC or T1α. ProSFTPC protein of ∼21 kDa was detected on day 0 and day 1, decreased on day 3, and was not detected on days 5 or 7 (Fig. 1C). In contrast, T1α of 36 kDa was not detected on days 0 and 1. It was weakly detected on day 3 and readily detected by days 5 and 7. Although changes in protein expression lagged behind changes in the respective mRNA, the collective data suggest the switch in cell phenotype occurs around day 3.

Fig. 1.

Alveolar epithelial type II (ATII) cells spontaneously undergo transdifferentiation to alveolar epithelial type I (ATI) cells during culture. Freshly isolated mouse primary ATII cells were analyzed immediately (D0) or cultured on tissue culture plastic for one (D1), three (D3), five (D5), or seven (D7) days. A: the mRNA expression levels of ATII markers surfactant protein (Sftp) a, Sftpb, and Sftpc were measured by quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) and graphed; n = 3 experiments; *P < 0.05 compared with D0. B: the mRNA expression levels of ATI markers T1α and aquaporin 5 (Aqp5) were measured by qRT-PCR and graphed; n = 3; *P < 0.05 compared with D0. C: cell lysates were harvested at the stated times and immunoblotted for proSFTPC and T1α, with β-actin used as a loading control. Images are representative of 3 experiments with similar findings.

Transdifferentiation is associated with a switch in TGF-β and BMP signaling.

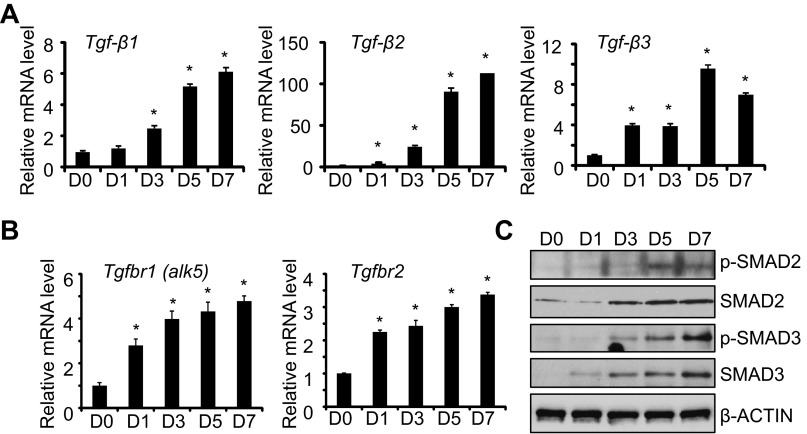

Because autocrine production of TGF-β1 stimulates transdifferentiation of rat ATII cells (3), we investigated whether it also affected transdifferentiation of mouse ATII cells. Levels of Tgf-β1, Tgf-β2, and Tgf-β3 mRNAs were low in freshly isolated ATII cells and increased significantly during culture (Fig. 2A). By day 7 of culture, the levels of Tgf-β2 mRNA had increased more dramatically (∼100-fold) compared with Tgf-β1 or Tgf-β3 (∼6- to 8-fold). During this time, expression of Tgf-β receptor type 1 (Tgfbr1, also called Alk5) and the Tgf-β receptor type 2 (Tgfbr2) mRNA increased (Fig. 2B). To determine if these changes were associated with increased TGF-β signaling, the expression of total and phosphorylated SMAD2 and SMAD3 protein was investigated. Increased expression and phosphorylation of SMAD2 and SMAD3 were observed between days 3 and 7 of culture (Fig. 2C). Increased phospho-SMAD expression was also associated with a modest two- to threefold increase in Smad3 but not Smad2 mRNA (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

The transforming growth factor (TGF)-β pathway is activated during culture of mouse ATII cells. ATII cells were freshly isolated (D0) or cultured for 7 days on tissue culture plastic. The mRNA expression levels of Tgf-β1, Tgf-β2, and Tgf-β3 (A) or Tgfbr1 (alk5) and Tgfbr2 (B) were determined by qRT-PCR and graphed relative to values obtained on D0; n = 3; *P < 0.05 compared with D0. C: cell lysates were harvested at the stated times and immunoblotted for phosphor (p)-SMAD2, total SMAD2, phospho-SMAD3, and total SMAD3, with β-actin used as loading control. Blots are representative of 3 experiments with similar results.

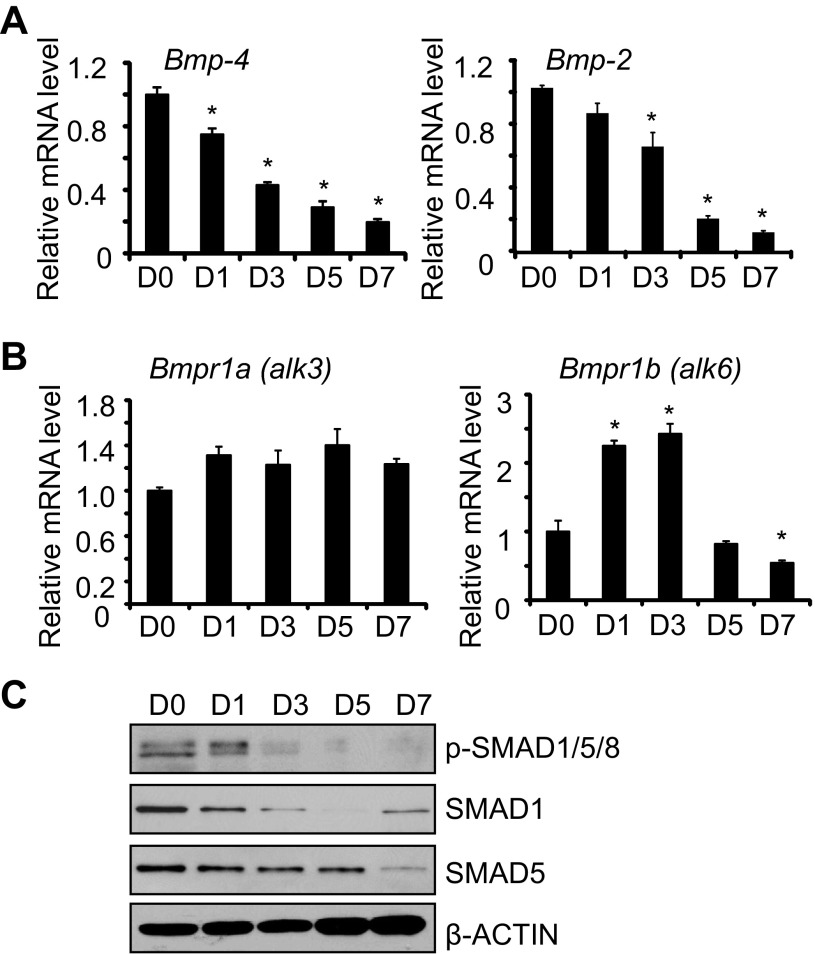

The activation of TGF-β signaling as ATII cells underwent transdifferentiation prompted us to evaluate whether BMP signaling also changed. In contrast to Tgf-β mRNA, levels of Bmp-4 and Bmp-2 mRNA were detected in freshly isolated ATII cells and progressively declined during culture (Fig. 3A). Although mRNA expression of BMP receptor type 1A (Bmpr1a, also called alk3) did not change during this time, expression of the BMP receptor type 1B (Bmpr1b, also called alk6) modestly increased on days 1 and day 3 before declining by day 7 (Fig. 3B). Phosphorylated SMAD1/5/8 and total SMAD1/5 expression also decreased with time (Fig. 3C). Reduced SMAD signaling was associated with reduced expression of SMAD1 and SMAD5 mRNA (data not shown).

Fig. 3.

The bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway is reduced during culture of mouse ATII cells. ATII cells were freshly isolated (D0) or cultured for 7 days on tissue culture plastic. The mRNA expression levels of Bmp-4 and Bmp-2 (A) or Bmpr1a (alk3) and Bmpr1b (alk6) (B) were determined by qRT-PCR and graphed relative to values obtained on D0; n = 3; *P < 0.05 compared with D0. C: cell lysates were harvested at the stated times and immunoblotted for phospho-SMAD1/5/8, SMAD1, and SMAD5, with β-actin used as a loading control. Blots are representative of 3 experiments with similar results.

Tgf-β and Bmp modulate the rate of transdifferentiation.

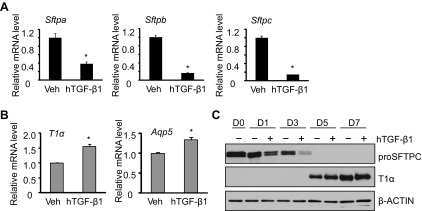

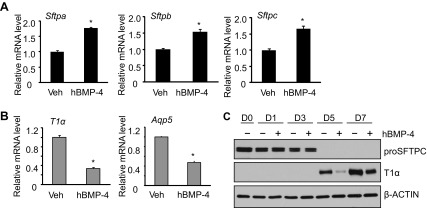

To determine whether this switch in TGF-β/BMP signaling affects transdifferentiation, ATII cells were cultured in the absence or presence of recombinant human TGF-β1 or BMP4. Cells were then harvested on the third day to study the loss of ATII-specific genes or on the fifth day to study the gain of ATI-specific genes.

Exogenously supplied hTGF-β1 dramatically inhibited the mRNA expression of Sftpa, Sftpb, and Sftpc (Fig. 4A). In contrast, it weakly but significantly stimulated the mRNA expression of T1α and Aqp5 (Fig. 4B). To validate the effects of hTGF-β1, the expression of proSFTPC and T1α proteins was evaluated by Western blot analysis. Expression of proSFTPC protein progressively declined on days 1 and 3, and TGF-β1 enhanced this loss (Fig. 4C). In contrast, T1α was not detected until days 5 and 7 of culture, and treatment with TGF-β1 minimally affected its expression. In contrast to the effects of TGF-β1, exogenously supplied BMP4 weakly stimulated mRNA expression of Sftpa, Sftpb, and Sftpc (Fig. 5A). Instead, it robustly reduced the mRNA expression of T1α and Aqp5 (Fig. 5B). The effects of BMP4 on ATII cell transdifferentiation were confirmed by blotting cell lysate with antibody against proSFTPC and T1α. ProSFTPC protein was detected on days 0, 1, and 3 but not on days 5 and 7. Treatment with BMP4 did not markedly affect the expression or loss of proSFTPC protein (Fig. 5C). T1α was not detected until days 5 and 7, and this induction was delayed in cells treated with BMP4.

Fig. 4.

TGF-β1 treatment promotes ATII transdifferentiation mainly by promoting loss of ATII phenotype. ATII cells were cultured in the absence or presence of human (h) TGF-β1 (4 ng/ml) through 7 days. A: the mRNA expression of Sftpa, Sftpb, and Sftpc at day 3 was determined by qRT-PCR and graphed relative to values obtained from cells treated with vehicle; n = 3; *P < 0.05. B: the mRNA expression of T1α and Aqp5 at day 5 was determined by qRT-PCR and graphed relative to values obtained from cells treated with vehicle; n = 3; *P < 0.05. C: cell lysates were harvested at the stated times and immunoblotted for proSFTPC and T1α, with β-actin used as a loading control. Blots are representative of 4 experiments with similar results.

Fig. 5.

BMP-4 treatment inhibits ATII transdifferentiation mainly by inhibiting gain of ATI phenotype. ATII cells were cultured in the absence or presence of hBMP-4 (200 ng/ml) through 7 days. A: the mRNA expression of Sftpa, Sftpb, and Sftpc at day 3 was determined by qRT-PCR and graphed relative to values obtained from cells treated with vehicle; n = 3; *P < 0.05. B: the mRNA expression of T1α and Aqp5 at day 5 was determined by qRT-PCR and graphed relative to values obtained from cells treated with vehicle; n = 3; *P < 0.05. C: cell lysates were harvested at the stated times and immunoblotted for proSFTPC and T1α, with β-actin used as a loading control. Blots are representative of 4 experiments with similar results.

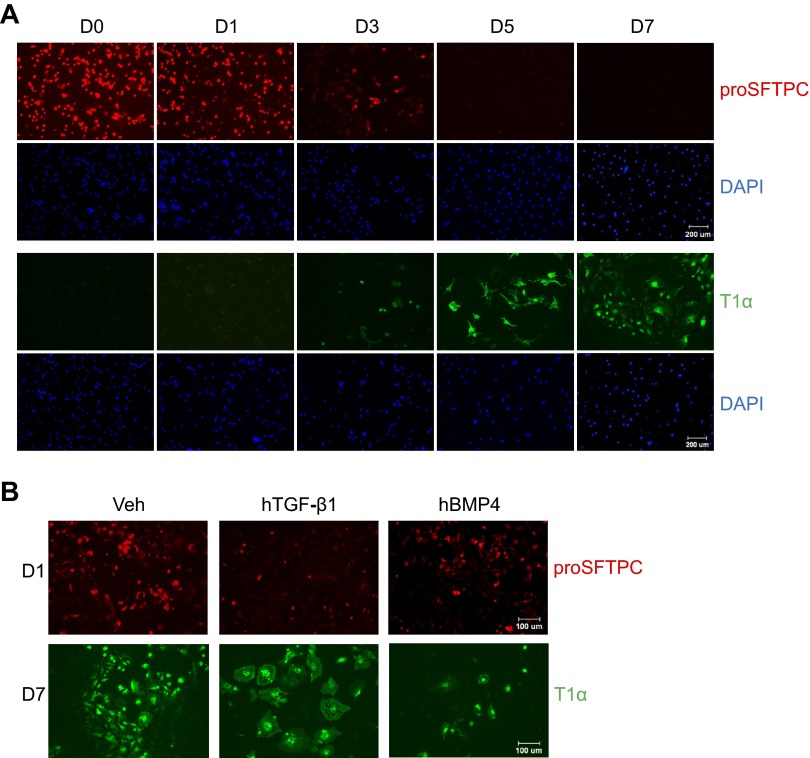

The loss of proSFTPC and gain in T1α as ATII cells underwent transdifferentiation were confirmed by immunofluorescence staining of the cells (Fig. 6A). ATII cells expressing proSFTPC were predominantly cuboidal and readily detected on days 0, 1, and 3. The differentiated cells expressing T1α displayed elongated spindle-shaped processes consistent with the more squamous features of ATI cells and were detected on days 3, 5, and 7. Consistent with TGF-β stimulating the loss of ATII-specific genes with minimal stimulation of ATI-specific genes, TGF-β reduced proSFTP-C staining but did not obviously affect T1α staining (Fig. 6B). The T1α-positive cells treated with TGF-β appeared larger and more filamentous, suggesting that they might be undergoing epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). However, none of these cells stained positive for α-smooth muscle actin (data not shown). In contrast, BMP inhibited ATI-specific gene as defined by reduced T1α staining, but it did not significantly affect proSFTPC staining. BMP4 did not appear to affect morphology of the cells.

Fig. 6.

TGF-β and BMP-4 affect gene expression and morphology. A: ATII cells isolated from mice or cultured on chamber slides through day 7 were immunostained with antibodies against proSFTPC (red) or T1α (green) followed by counterstaining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, blue). Images are representative of 3 experiments with similar results. B: ATII cells treated with hTGF-β1 (4 ng/ml) or hBMP-4 (200 ng/ml) for 1 day were fixed and stained for proSFTPC (red). ATII cells treated with hTGF-β1 (4 ng/ml) or hBMP-4 (200 ng/ml) for 7 days were fixed and stained for T1α (green). Images are representative of 3 experiments with similar results. Scale bar in A = 200 μm and in B = 100 μm.

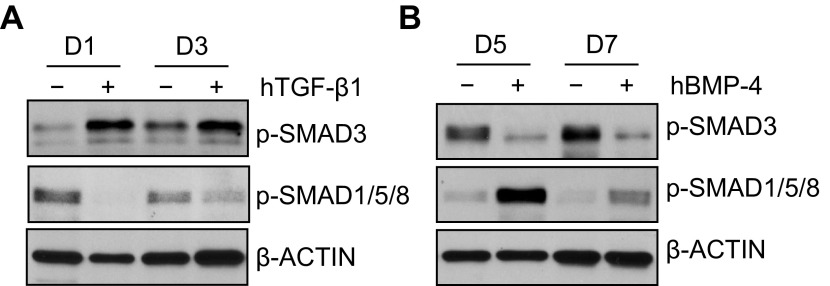

TGF-β and BMP signaling antagonize each other during culture.

The switch in TGF-β and BMP signaling, and the unique effects each had on the transdifferentiation of ATII cells, suggested that they might antagonize each other. To investigate this hypothesis, ATII cells were cultured in the absence or presence of hTGF-β1 for 1 or 3 days. As predicted, treatment with TGF-β1 stimulated TGF-β-dependent phosphorylated SMAD3 and inhibited the BMP-dependent phosphorylated SMAD1/5/8 (Fig. 7A). In contrast, treatment with hBMP-4 for 5 or 7 days stimulated BMP-dependent phosphorylated SMAD1/5/8 and suppressed the TGF-β-dependent phosphorylated SMAD3 (Fig. 7B). Together, these findings suggest TGF-β and BMP signaling antagonizes each other during culture.

Fig. 7.

TGF-β and BMP signaling antagonizes each other during culture. Primary ATII cells were treated with hTGF-β1 (4 ng/ml) (A) or hBMP-4 (200 ng/ml) (B). Cells treated with TGF-β1 were harvested on days 1 and 3, whereas cells treated with BMP-4 were harvested on days 5 and 7. Cell lysates were immunoblotted for phosphorylated SMAD3 or phosphorylated SMAD1/5/8, with β-actin used as a loading control. Blots are representative of 3 experiments with similar results.

TGF-β/BMP signaling regulates epithelial gene expression in MLE15 cells.

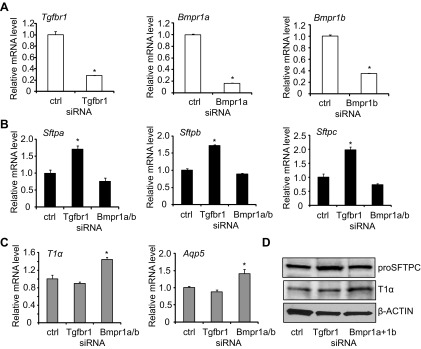

MLE15 cells were used to confirm TGF-β and BMP signaling regulates alveolar epithelial cell-specific gene expression. Although these immortalized cells exhibit ATII morphology and express surfactant proteins, they also express T1α and Aqp5. To inhibit TGF-β and BMP signaling, MLE15 cells were transfected with siRNA targeting TGF-βR1, BMPR1a, and BMPR1b. This approach reduced expression of the respective target mRNAs by 20–40% (Fig. 8A). Because targeting of BMPR1b was the least effective, siRNAs targeting both BMPR1a and BMPR1b were used to inhibit BMP signaling. Interestingly and somewhat consistent with the primary mouse ATII cells, siRNA depletion of TGF-βR1 enhanced expression of Sftpa, Sftpb, and Sftpc, but not T1α or Aqp5 (Fig. 8B). On the other hand, siRNA depletion of BMP receptors enhanced expression of T1α and Aqp5, but not Sftpa, Sftpb, or Sftpc (Fig. 8C). Western blot analysis confirmed that these modest but significant changes in Sftpc and T1α mRNA expression correlated with changes in protein abundance (Fig. 8D).

Fig. 8.

TGF-β and BMP signaling affects basal expression of ATII and ATI genes in MLE15 cells. MLE15 cells were transfected with small-interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting TGF-βR1, BMPR1a, and BMPR1b mRNAs or a nontargeting control. A: the mRNA expression of TGF-βR1, BMPR1a, BMPR1b was determined by qRT-PCR and graphed relative to values obtained with cells transfected with nontargeting oligonucleotides; n = 3; *P < 0.05. B: the mRNA expression of Sftpa, Sftpb, and Sftpc was determined by qRT-PCR and graphed relative to values obtained with cells transfected with nontargeting oligonucleotides; n = 3; *P < 0.05. C: the mRNA expression of T1α and Aqp5 was determined by qRT-PCR and graphed relative to values obtained with cells transfected with nontargeting oligonucleotides; n = 3; *P < 0.05. D: cell lysates were harvested and immunoblotted for proSFTPC and T1α, with β-actin used as a loading control.

DISCUSSION

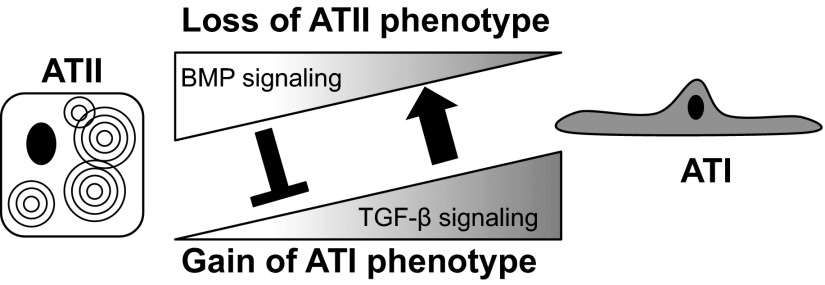

ATII cells can be considered bipotential epithelial stem cells of lung alveoli because they can self-renew and transdifferentiate into ATI cells. The spontaneous loss of surfactant-associated proteins and gain of T1α and Aqp5 in freshly isolated ATII cells suggest that transdifferentiation is a default pathway, perhaps triggered by cell injury created during the isolation procedure and/or change in factors that control transdifferentiation. This study demonstrates for the first time that, concomitant with changes in ATII and ATI markers, significant alterations in TGF-β and BMP signaling were also observed. TGF-β signaling increased over time and promoted ATII cell transdifferentiation by stimulating the loss of ATII cell phenotype (Fig. 9). In contrast, BMP signaling inhibited the gain of ATI phenotype but was lost as the cells underwent transdifferentiation. Interestingly, TGF-β weakly promoted the gain of ATI phenotype, and BMP weakly inhibited the loss of ATII cell phenotype. Opposing TGF-β/BMP signaling may therefore be responsible for these weaker activities. Hence, the opposing actions of TGF-β and BMP signaling that switch during in vitro culture provide a model to explain why primary ATII cells spontaneously undergo transdifferentiation to ATI cells. This spontaneous and rapid transdifferentiation of culture ATII cells often hinders our ability to study plasticity of these cells. The knowledge that opposing TGF-β/BMP signaling controls the rate of transdifferentiation provides new opportunities for investigating how the phenotype of ATII and ATI cells is controlled.

Fig. 9.

Hypothetical model for how TGF-β and BMP pathways affect the transdifferentiation of ATII cells. Cuboidal ATII cells spontaneously undergo transdifferentiation to ATI cells when cultured ex vivo. BMP signaling in ATII cells inhibits transdifferentiation mainly by blocking the gain of ATI-specific genes (black T bar). TGF-β signaling increases as ATII cells obtain ATI-like properties and promotes the loss of ATII cell phenotype mainly by stimulating the loss of ATII-specific genes (black arrow). Because TGF-β and BMP signaling antagonizes each other, the relative levels of these two opposing signaling systems determine the rate of transdifferentiation.

Our results suggest the rate of transdifferentiation is controlled by antagonism between TGF-β and BMP signaling pathways. Expression of TGF-β and BMP is inversely correlated during ATII cell transdifferentiation, and exogenous TGF-β can decrease the endogenous BMP signaling and vice versa. Exogenous TGF-β dramatically inhibits ATII marker genes expression both at mRNA and protein levels, indicating direct effects of TGF-β on loss of ATII cell phenotype. Similar effects were seen in MLE15 cells. Our findings confirm previous work showing how TGF-β1, -β2, and -β3 inhibit expression of Sftpa in human lung adenocarcinoma H441 and H820 cells (48). Exogenous BMP dramatically inhibits ATI marker genes expression, indicating the direct inhibition of BMP on gain of ATI cell phenotype. However, only moderate effects of exogenous TGF-β on ATI genes and those of BMP on ATII genes were detected. Again, similar findings were seen in MLE15 cells. Hypothetically, weak TGF-β signaling on ATI genes and weak BMP signaling on ATII genes are caused indirectly by an antagonism of the opposing pathway. Therefore, TGF-β and BMP signaling may directly affect transdifferentiation of ATII to ATI cells, and they may also antagonize each other in a minor manner to achieve finer tuning. Intriguingly, MAPPER software (www.mapper.chip.org) suggests the promoters for the surfactant proteins, T1α, and Aqp5 contain many canonical binding sites for SMAD proteins (data not shown). Assuming the binding of SMAD proteins is relatively constant, regulation of gene expression would then be controlled by the relative balance of specific heterodimeric SMAD proteins created by the intensity of TGF-β and BMP signaling within the cell.

It is important to appreciate that transdifferentiation of ATII to ATI cells is a spontaneous process that is initiated by an unknown mechanism. The current findings suggest gain in TGF-β signaling may be more prominent in initiating this process than loss of BMP signaling. As shown in Figs. 2 and 3, expression of TGF-βR1 and TGF-βR2 increases within the first 24 h of culture, whereas the expression of BMPR1a and -1b did not change or increased. The mRNA levels of TGF-β ligands, and in particular TGF-β2, increased more dramatically than BMP ligands decreased. Together, these findings suggest ATII cells express more TGF-β and become more responsive to TGF-β as they differentiate to ATI cells. Indeed, TGF-β positively regulates its own expression or that of its receptors in a variety of cells, thereby amplifying its own signaling (27, 34). It also, as shown in the current study, inhibits BMP signaling. For instance, competing TGF-β and BMP signaling controls hair follicle stem cell activation, and embryonic stem cells derived from humans with Marfan syndrome support this concept (35, 36). In more specialized cell types such as pulmonary myofibroblastic cells and pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells, it has been also observed that perturbation of BMP signaling leads to alteration of TGF-β signaling in an opposite direction (25, 33). Thus, opposing TGF-β and BMP signaling plays an important role in regulating the plasticity of progenitor cells, including ATII cells in lung alveoli. Theoretically, the upregulation of TGF-β signaling, perhaps initiated by the release of bioactive TGF-β as the cells were isolated, would enhance expression of TGF-β ligand and receptors, and inhibit BMP signaling that collectively drives the process of transdifferentiation. In such a model, the activation of latent TGF-β when the alveolar epithelium is injured may therefore play an important role in promoting epithelial repair.

Because our data demonstrate that TGF-β and BMP signaling plays crucial roles in ATII cell differentiation, one may wonder whether some well-known factors or conditions affecting ATII cell differentiation have innate associations with these two signaling pathways. For example, culturing on matrigel maintains ATII cell phenotype and even induces primary rat ATI cells to express ATII or airway epithelial cell genes (22). Matrigel is a mixture of extracellular matrix secreted by Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma cells and reportedly contains ∼1,800 proteins (24), which makes it a daunting task to identify what is exactly responsible for maintaining ATII cell phenotypes. Predominantly consisting of laminin, collagen IV, and enactin, matrigel can also be confirmed through immunoassays to contain a variety of growth factors, including basic fibroblast growth factor, epidermal growth factor, and TGF-β. Interestingly, matrigel inhibits gene expression of TGF-β2 in cultured human corneal epithelial cells (28), suggesting that it might maintain ATII cell phenotype by blocking the marked upregulation of TGF-β2 observed in the current study. Matrigel can also bind TGF-β and therefore affect TGF-β-dependent signaling such as occurring as ATII cells undergo transdifferentiation to ATI cells (46). Because TGF-β can affect how KGF interacts with laminin 5, a principal component of matrigel, and laminin 5 helps promote ATI cell phenotype, the induction of TGF-β may drive transdifferentiation through laminin 5 interactions (14). Alveolar epithelial cell stretch is important for proper lung development with static stretch stimulating ATI phenotype through Rho-dependent kinase and cyclic stretch enhancing ATII phenotype (20). TGF-β and BMP signaling may therefore influence transdifferentiation through their ability to regulate expression of matrix proteins. Together, our results suggest that involvement of TGF-β and BMP signaling needs to be taken into account when ATII cells maintain their phenotypes or differentiate into ATI cells upon exogenous stimuli.

Postnatal alveolar development requires balanced TGF-β and BMP signaling. Alveolar simplification occurs when TGF-β1 is overexpressed (21, 31, 45) or when TGF-β1 signaling is disrupted via the loss of Smad3 (4, 8, 30, 42). Likewise, conditional loss of the high-affinity receptor TGF-βR2 results in a simplified lung with fewer ATI cells, as defined by less expression of T1α (9, 30). This implies TGF-β stimulates differentiation of ATII to ATI cells (3). Hence, it is not surprising to think TGF-β contributes to neonatal lung disease, especially when elevated levels are seen in human infants with bronchopulmonary dysplasia or BPD (2, 29). In experimental mouse models of BPD, TGF-β signaling is enhanced and BMP signaling is impaired evidenced by altered expressions of TGF-β and BMP receptors and downstream responsive genes (37). Reduced expression of BMP-4 has also been reported in rat ATII cells exposed to hyperoxia (10). In addition, deficiency of BMP type 1 receptor Alk3 in lung epithelia results in dysplastic lung formation and neonatal respiratory distress (17, 42). TGF-β also plays an important role in wound repair and, in particular, the promotion of fibrotic lung disease. For example, Smad3 null mice are resistant to bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis (4, 51). Conditional loss of Tgf-βRII in the respiratory epithelium or in fibroblasts also attenuates bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis (23, 30). TGF-β has also been implicated in promoting EMT of ATII cells, but those conclusions are controversial (26, 37, 43, 50). Thus, TGF-β and BMP signaling is essential for proper alveolar epithelial cell development and has been implicated in lung disease. The observations in the current study suggest some of these effects may be on their ability to control the proper differentiation state of ATI and ATII cells.

In summary, we found that opposing TGF-β and BMP signaling is an important regulator of alveolar epithelial cell plasticity. Because TGF-β and BMP signaling reverses as ATII cells transdifferentiate into ATI cells, understanding how they are regulated could provide new therapeutic targets for treating lung diseases involving dysregulated alveolar epithelial cell repair.

GRANTS

This work was supported, in part, by March of Dimes Grant 06-FY-08-264 and National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grants HL-091968 and HL-097141 to M. A. O'Reilly.

DISCLOSURES

The authors do not have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: L.Z. and M.A.O. conception and design of research; L.Z. and M.Y. performed experiments; L.Z., M.Y., and M.A.O. analyzed data; L.Z., M.Y., and M.A.O. interpreted results of experiments; L.Z. prepared figures; L.Z. and M.A.O. drafted manuscript; L.Z., M.Y., and M.A.O. edited and revised manuscript; L.Z., M.Y., and M.A.O. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adamson IY, Bowden DH. The type 2 cell as progenitor of alveolar epithelial regeneration. A cytodynamic study in mice after exposure to oxygen. Lab Invest 30: 35–42, 1974 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alejandre-Alcazar MA, Kwapiszewska G, Reiss I, Amarie OV, Marsh LM, Sevilla-Perez J, Wygrecka M, Eul B, Kobrich S, Hesse M, Schermuly RT, Seeger W, Eickelberg O, Morty RE. Hyperoxia modulates TGF-beta/BMP signaling in a mouse model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 292: L537–L549, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhaskaran M, Kolliputi N, Wang Y, Gou D, Chintagari NR, Liu L. Trans-differentiation of alveolar epithelial type II cells to type I cells involves autocrine signaling by transforming growth factor beta 1 through the Smad pathway. J Biol Chem 282: 3968–3976, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonniaud P, Kolb M, Galt T, Robertson J, Robbins C, Stampfli M, Lavery C, Margetts PJ, Roberts AB, Gauldie J. Smad3 null mice develop airspace enlargement and are resistant to TGF-beta-mediated pulmonary fibrosis. J Immunol 173: 2099–2108, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Borok Z, Danto SI, Lubman RL, Cao Y, Williams MC, Crandall ED. Modulation of t1alpha expression with alveolar epithelial cell phenotype in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 275: L155–L164, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borok Z, Danto SI, Zabski SM, Crandall ED. Defined medium for primary culture de novo of adult rat alveolar epithelial cells. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 30A: 99–104, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Borok Z, Lubman RL, Danto SI, Zhang XL, Zabski SM, King LS, Lee DM, Agre P, Crandall ED. Keratinocyte growth factor modulates alveolar epithelial cell phenotype in vitro: expression of aquaporin 5. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 18: 554–561, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen H, Sun J, Buckley S, Chen C, Warburton D, Wang XF, Shi W. Abnormal mouse lung alveolarization caused by Smad3 deficiency is a developmental antecedent of centrilobular emphysema. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 288: L683–L691, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen H, Zhuang F, Liu YH, Xu B, Del Moral P, Deng W, Chai Y, Kolb M, Gauldie J, Warburton D, Moses HL, Shi W. TGF-beta receptor II in epithelia versus mesenchyme plays distinct roles in the developing lung. Eur Respir J 32: 285–295, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen Z, Chintagari NR, Guo Y, Bhaskaran M, Chen J, Gao L, Jin N, Weng T, Liu L. Gene expression of rat alveolar type II cells during hyperoxia exposure and early recovery. Free Radic Biol Med 43: 628–642, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Corti M, Brody AR, Harrison JH. Isolation and primary culture of murine alveolar type II cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 14: 309–315, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahlin K, Mager EM, Allen L, Tigue Z, Goodglick L, Wadehra M, Dobbs L. Identification of genes differentially expressed in rat alveolar type I cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 31: 309–316, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Danto SI, Shannon JM, Borok Z, Zabski SM, Crandall ED. Reversible transdifferentiation of alveolar epithelial cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 12: 497–502, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Decline F, Rousselle P. Keratinocyte migration requires alpha2beta1 integrin-mediated interaction with the laminin 5 gamma2 chain. J Cell Sci 114: 811–823, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Demaio L, Tseng W, Balverde Z, Alvarez JR, Kim KJ, Kelley DG, Senior RM, Crandall ED, Borok Z. Characterization of mouse alveolar epithelial cell monolayers. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 296: L1051–L1058, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dobbs LG, Pian MS, Maglio M, Dumars S, Allen L. Maintenance of the differentiated type II cell phenotype by culture with an apical air surface. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 273: L347–L354, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eblaghie MC, Reedy M, Oliver T, Mishina Y, Hogan BL. Evidence that autocrine signaling through Bmpr1a regulates the proliferation, survival and morphogenetic behavior of distal lung epithelial cells. Dev Biol 291: 67–82, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Evans MJ, Cabral LJ, Stephens RJ, Freeman G. Transformation of alveolar type 2 cells to type 1 cells following exposure to NO2. Exp Mol Pathol 22: 142–150, 1975 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fehrenbach H. Alveolar epithelial type II cell: defender of the alveolus revisited. Respir Res 2: 33–46, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Foster CD, Varghese LS, Gonzales LW, Margulies SS, Guttentag SH. The Rho pathway mediates transition to an alveolar type I cell phenotype during static stretch of alveolar type II cells. Pediatr Res 67: 585–590, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gauldie J, Galt T, Bonniaud P, Robbins C, Kelly M, Warburton D. Transfer of the active form of transforming growth factor-beta 1 gene to newborn rat lung induces changes consistent with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Pathol 163: 2575–2584, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gonzalez RF, Allen L, Dobbs LG. Rat alveolar type I cells proliferate, express OCT-4, and exhibit phenotypic plasticity in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L1045–L1055, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoyles RK, Derrett-Smith EC, Khan K, Shiwen X, Howat SL, Wells AU, Abraham DJ, Denton CP. An essential role for resident fibroblasts in experimental lung fibrosis is defined by lineage-specific deletion of high-affinity type II transforming growth factor beta receptor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 183: 249–261, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hughes CS, Postovit LM, Lajoie GA. Matrigel: a complex protein mixture required for optimal growth of cell culture. Proteomics 10: 1886–1890, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Izumi N, Mizuguchi S, Inagaki Y, Saika S, Kawada N, Nakajima Y, Inoue K, Suehiro S, Friedman SL, Ikeda K. BMP-7 opposes TGF-beta1-mediated collagen induction in mouse pulmonary myofibroblasts through Id2. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L120–L126, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kim KK, Kugler MC, Wolters PJ, Robillard L, Galvez MG, Brumwell AN, Sheppard D, Chapman HA. Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 13180–13185, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kleeff J, Korc M. Up-regulation of transforming growth factor (TGF)-beta receptors by TGF-beta1 in COLO-357 cells. J Biol Chem 273: 7495–7500, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.LaGier AJ, Yoo SH, Alfonso EC, Meiners S, Fini ME. Inhibition of human corneal epithelial production of fibrotic mediator TGF-beta2 by basement membrane-like extracellular matrix. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48: 1061–1071, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lecart C, Cayabyab R, Buckley S, Morrison J, Kwong KY, Warburton D, Ramanathan R, Jones CA, Minoo P. Bioactive transforming growth factor-beta in the lungs of extremely low birthweight neonates predicts the need for home oxygen supplementation. Biol Neonate 77: 217–223, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li M, Krishnaveni MS, Li C, Zhou B, Xing Y, Banfalvi A, Li A, Lombardi V, Akbari O, Borok Z, Minoo P. Epithelium-specific deletion of TGF-beta receptor type II protects mice from bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. J Clin Invest 121: 277–287, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Maeda Y, Dave V, Whitsett JA. Transcriptional control of lung morphogenesis. Physiol Rev 87: 219–244, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Massague J. The transforming growth factor-beta family. Annu Rev Cell Biol 6: 597–641, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morrell NW. Pulmonary hypertension due to BMPR2 mutation: a new paradigm for tissue remodeling? Proc Am Thorac Soc 3: 680–686, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Reilly MA, Danielpour D, Roberts AB, Sporn MB. Regulation of expression of transforming growth factor-beta 2 by transforming growth factor-beta isoforms is dependent upon cell type. Growth Factors 6: 193–201, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oshimori N, Fuchs E. Paracrine TGF-beta signaling counterbalances BMP-mediated repression in hair follicle stem cell activation. Cell Stem Cell 10: 63–75, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Quarto N, Li S, Renda A, Longaker MT. Exogenous activation of BMP-2 signaling overcomes TGFbeta-mediated inhibition of osteogenesis in Marfan embryonic stem cells and Marfan patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cells 30: 2709–2719, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rock JR, Barkauskas CE, Cronce MJ, Xue Y, Harris JR, Liang J, Noble PW, Hogan BL. Multiple stromal populations contribute to pulmonary fibrosis without evidence for epithelial to mesenchymal transition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: E1475–E1483, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shannon JM, Jennings SD, Nielsen LD. Modulation of alveolar type II cell differentiated function in vitro. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 262: L427–L436, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shannon JM, Mason RJ, Jennings SD. Functional differentiation of alveolar type II epithelial cells in vitro: effects of cell shape, cell-matrix interactions and cell-cell interactions. Biochim Biophys Acta 931: 143–156, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shi Y, Massague J. Mechanisms of TGF-beta signaling from cell membrane to the nucleus. Cell 113: 685–700, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stone KC, Mercer RR, Freeman BA, Chang LY, Crapo JD. Distribution of lung cell numbers and volumes between alveolar and nonalveolar tissue. Am Rev Respir Dis 146: 454–456, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sun J, Chen H, Chen C, Whitsett JA, Mishina Y, Bringas P, Jr, Ma JC, Warburton D, Shi W. Prenatal lung epithelial cell-specific abrogation of Alk3-bone morphogenetic protein signaling causes neonatal respiratory distress by disrupting distal airway formation. Am J Pathol 172: 571–582, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tanjore H, Xu XC, Polosukhin VV, Degryse AL, Li B, Han W, Sherrill TP, Plieth D, Neilson EG, Blackwell TS, Lawson WE. Contribution of epithelial-derived fibroblasts to bleomycin-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 180: 657–665, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tryka AF, Witschi H, Gosslee DG, McArthur AH, Clapp NK. Patterns of cell proliferation during recovery from oxygen injury. Species differences. Am Rev Respir Dis 133: 1055–1059, 1986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vicencio AG, Lee CG, Cho SJ, Eickelberg O, Chuu Y, Haddad GG, Elias JA. Conditional overexpression of bioactive transforming growth factor-beta1 in neonatal mouse lung: a new model for bronchopulmonary dysplasia? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 31: 650–656, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vukicevic S, Kleinman HK, Luyten FP, Roberts AB, Roche NS, Reddi AH. Identification of multiple active growth factors in basement membrane Matrigel suggests caution in interpretation of cellular activity related to extracellular matrix components. Exp Cell Res 202: 1–8, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wade KC, Guttentag SH, Gonzales LW, Maschhoff KL, Gonzales J, Kolla V, Singhal S, Ballard PL. Gene induction during differentiation of human pulmonary type II cells in vitro. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 34: 727–737, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Whitsett JA, Budden A, Hull WM, Clark JC, O'Reilly MA. Transforming growth factor-beta inhibits surfactant protein A expression in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta 1123: 257–262, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wikenheiser KA, Vorbroker DK, Rice WR, Clark JC, Bachurski CJ, Oie HK, Whitsett JA. Production of immortalized distal respiratory epithelial cell lines from surfactant protein C/simian virus 40 large tumor antigen transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90: 11029–11033, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Willis BC, Liebler JM, Luby-Phelps K, Nicholson AG, Crandall ED, du Bois RM, Borok Z. Induction of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in alveolar epithelial cells by transforming growth factor-beta1: potential role in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Pathol 166: 1321–1332, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhao J, Shi W, Wang YL, Chen H, Bringas P, Jr, Datto MB, Frederick JP, Wang XF, Warburton D. Smad3 deficiency attenuates bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 282: L585–L593, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]