Abstract

Sustained lung inflations (SI) at birth may recruit functional residual capacity (FRC). Clinically, SI increase oxygenation and decrease need for intubation in preterm infants. We tested whether a SI to recruit FRC would decrease lung injury from subsequent ventilation of fetal, preterm lambs. The preterm fetus (128 ± 1 day gestation) was exteriorized from the uterus, a tracheostomy was performed, and fetal lung fluid was removed. While maintaining placental circulation, fetuses were randomized to one of four 15-min interventions: 1) positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) 8 cmH2O (n = 4), 2) 20 s SI to 50 cmH2O then PEEP 8 cmH2O (n = 10), 3) mechanical ventilation at tidal volume (VT) 7 ml/kg (n = 13), or 4) 20 s SI then ventilation at VT 7 ml/kg (n = 13). Lambs were ventilated with 95% N2/5% CO2 and PEEP 8 cmH2O. Volume recruitment was measured during SI, and fetal tissues were collected after an additional 30 min on placental support. SI achieved a mean FRC recruitment of 15 ml/kg (range 8–27). Fifty percent of final FRC was achieved by 2 s, 65% by 5 s, and 90% by 15 s, demonstrating prolonged SI times are needed to recruit FRC. SI alone released acute-phase proteins into the fetal lung fluid and increased mRNA expression of proinflammatory cytokines and acute-phase response genes in the lung. Mechanical ventilation further increased all markers of lung injury. SI before ventilation, regardless of the volume of FRC recruited, did not alter the acute-phase and proinflammatory responses to mechanical ventilation at birth.

Keywords: bronchopulmonary dysplasia, functional residual capacity, inflammation, resuscitation

the recruitment of a functional residual capacity (FRC) at birth is fundamental for the transition of the fetal lung to gas exchange. Normal newborns inflate their lungs at birth by generating large negative-pressure breaths, which pulls the lung fluid from the airways into the distal airspaces and parenchyma (15, 40). Unfortunately, the majority of very low birth weight (VLBW) infants need some form of assistance with breathing at birth (6, 19). The combination of surfactant-deficient lungs and a highly compliant chest wall makes development of FRC at birth difficult for many VLBW infants. Maintaining a prolonged inspiratory pressure to recruit FRC, commonly referred to as a sustained inflation (SI), helps overcome the long-time constant necessary to aerate the fluid-filled lung and creates more uniformed aeration of the preterm lung (15, 21). A SI at birth augmented the cardiorespiratory transition after delivery in preterm lambs and improved the heart rate response to resuscitation of asphyxiated near-term lambs (21, 36). In preterm infants, a SI at birth decreased need for mechanical ventilation (MV) at 72 h and may lead to a decrease in bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) (26, 39). Although not included in the 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for neonatal resuscitation, the European guidelines suggest five 2- to 3-s SI may be helpful in VLBW infants, and this has become the practice at many centers (19, 30). Little is known about the effects of SI on lung injury or lung inflammation in the preterm.

Ventilation at birth with a large tidal volume (VT) might be expected to injure the preterm lung (12). However, even ventilation at birth with a VT similar to spontaneous breathing lambs causes an inflammation in the lungs of preterm sheep (13). MV at birth leads to the release of stored acute-phase proteins in lung fluid and activation of mRNA for inflammatory mediators within the lung parenchyma (13, 14). The combination of surfactant deficiency and increased lung fluid in the airways leads to increased sheer force injury to the airways during the initiation of ventilation at birth in preterm lambs (10). Large VT ventilation at birth also causes systemic inflammation and brain injury (12, 33). These systemic effects are less pronounced with moderate VT (33). Lung inflammation is central to the development of BPD, and the lung injury caused by MV may be initiated with the first few breaths after birth (26).

Recruitment maneuvers to open the lung and facilitate ventilation have been used in both adults with acute respiratory distress syndrome and in neonates with respiratory distress syndrome (4, 7). Repetitive opening and closing of alveoli increases lung injury in animal models (5). However, the use of high-frequency oscillatory ventilation to stent open the alveoli has not decreased the rate of BPD compared with conventional ventilation in VLBW infants (3). The use of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) to maintain alveolar patency is beneficial for ventilation in the neonatal intensive care unit (28). PEEP is necessary for maintaining FRC in the surfactant-deficient rabbit (38), and we have demonstrated a benefit of PEEP for the initiation of ventilation on markers of lung injury in preterm lambs (14). A SI at birth should recruit FRC and facilitate the initiation of ventilation of an “open lung” (38). We have developed a lung resuscitation model with fetal sheep that allows us to separate the elements of the initiation of breathing while avoiding continued ventilation and oxygen exposure (10, 12, 14). We have used this fetal model to test the hypothesis that a 20-s SI would recruit FRC and decrease lung injury caused by ventilation of the surfactant-deficient preterm sheep lung.

METHODS

Fetal exposure for ventilation.

The Animal Ethics Committees of the University of Western Australia and Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center approved the studies. Date-mated Merino Ewes at 128 ± 1 days gestational age (term is 150 days gestational age) were premedicated with xylazine (0.5 mg/kg im), ketamine (5 mg/kg iv), and midazolam (0.25 mg/kg iv) before induction of maternal anesthesia with inhaled isofluorane. The fetal head and chest were exteriorized through a midline hysterotomy while maintaining placental blood flow (12). The fetus had a 4-Fr endotracheal tube secured tightly following a tracheostomy to avoid air leak. Free-flowing fetal lung fluid (FLF) was gently removed with an 8-Fr catheter, and an aliquot was snap-frozen.

Physiological measurements.

A respiratory impedance band (Carefusion) was placed around the fetal chest before ventilation, secured tightly with an umbilical cord clamp, and attached to a Bicore-II (Cardinal Health) impedance monitor. The endotracheal tube was attached to a ventilator (Babylog 8000+; Dräger, Lübeck, Germany) and a Neopuff (Fisher & Paykel) via a three-way slip valve (Hans Rudolph) to avoid loss of FRC when moving from SI to MV. In line with the endotracheal tube, we placed the pneumotach for the Dräger ventilator and an additional Hans Rudolph 1.3-ml pneumotach, attached to a RSS HR100 system (Hans Rudolph). Data from both pneumotachs and respiratory impedance (RIP) band were simultaneously recorded on LabChart 7 Pro (ADInstruments). The BiCore II tracing (RIP) was calibrated with a three-step inflation to 30 ml after completion of ventilation.

Fetal interventions.

The fetal lambs were randomly assigned to four 15-min intervention groups: 1) a PEEP of 8 cmH2O (PEEP), 2) a 20-s SI at 50 cmH2O with a T-piece resuscitator (Neopuff) using a flow rate of 8 l/min, followed by PEEP of 8 cmH2O (SI), 3) mechanical ventilation from birth (MV), or 4) 20 s SI then mechanical ventilation (SI + MV). The fetal lambs randomized to MV, with or without SI, were ventilated at 40 breaths/min with an inspiratory time of 0.7 s. Pressures were adjusted to maintain a VT of 6–7 ml/kg using the Dräger infant ventilator, and the maximal peak inspiratory pressure (PIP) used was 50 cmH2O. All lambs received heated, humidified 95% nitrogen/5% CO2 to avoid oxygen exposure and a change in fetal Pco2. After the intervention, FLF was collected (FLF 15 min), and the endotracheal tube was occluded. The fetus was covered to maintain temperature and remained on placental support for an additional 30 min. The fetus was killed with pentobarbital (100 mg/kg), and cord blood gases and FLF were collected (FLF 45 min) at 45 min from the beginning of the recruitment procedure. The 45-min experimental period was used to optimize the detection of acute-phase inflammatory response (33).

Lung processing and bronchoalveolar lavage analysis.

At autopsy, an air deflation pressure-volume curve was measured from an inflation pressure of 40 cmH2O pressure (16). Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of the left lung was collected by repetitive saline lavage. FLF and BALF were used for measurement of total protein (27) and sandwich ELISA assays for heat shock protein (HSP) 70 and HSP60 (R&D Systems) (14). Saturated phosphatidylcholine (Sat PC) was recovered after alumina column chromatography and quantified by phosphorus assay (18). Tissues from the right lower lung were snap-frozen for RNA isolation. The right upper lobe was inflation fixed with 10% formalin at 30 cmH2O and then paraffin embedded (23).

Quantitative RT-PCR.

mRNA was extracted from lung tissue from the right middle lobe with TRIzol (Invitrogen). cDNA was produced from 1 mg mRNA using the Verso cDNA kit (Thermoscientific). We used custom Taqman gene primers (Applied Biosystems) for ovine sequences for IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1), early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1), nuclear receptor family 77 (Nur77), cysteine rich 61 (Cyr61), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) (13, 14). Quantitative RT-PCR was performed with 5 ng cDNA using Taqman Master mix in a 20-μl reaction on a 7300 RT-PCR machine and software (Applied Biosystems). 18S primers (Applied Biosystems) were used for the internal loading control. Tissues from age-matched unventilated controls (UVC) from previous experiments were used as additional controls (13, 32), and results are reported as fold increase over mean for the unventilated animals.

Immunohistochemistry/in situ hybridization.

Immunostaining protocols used paraffin sections (5 μm) of formalin-fixed tissues that were pretreated with 3% hydrogen peroxide to inactivate endogenous peroxidases (17, 22). The sections were incubated with anti-human Egr-1 1:250 dilution (Santa Cruz), Nur77 1:200 (Santa Cruz) in 4% normal goat serum overnight, followed by biotin-labeled secondary antibody. Immunostaining was visualized by a Vectastain ABC Peroxidase Elite kit to detect the antigen-antibody complexes (Vector Laboratories). The antigen detection was enhanced with nickel-DAB, followed by TRIS-cobalt, and the nuclei were counterstained with nuclear fast red or eosin (Egr-1) (22).

Data analysis and statistics.

Results are shown as means (SE). Statistics were analyzed using InStat (GraphPad) using Student's t-test, Mann-Whitney nonparametric, or ANOVA tests as appropriate. Significance was accepted as P < 0.05.

RESULTS

All lambs survived the exteriorization, 15-min ventilation period, and the subsequent 30-min period on placental support, and there were no differences between groups in the blood gas values at delivery or the ratio of male/female fetuses (Table 1). The volumes measured from RIP bands and the volumes recorded on the pneumotachs were similar for the lambs (Table 1). Volumes from the in-line pneumotach have been used for subsequent calculated values of milliliters per kilogram. A modest degree of variability was seen in the RIP band signal throughout the 15-min ventilation period.

Table 1.

Animal description and physiology

| Recruitment Volume, ml/kg |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | n | Birth Wt, kg | Male/Female | PT | RIP | VT at 15 min, ml/kg | Compliance at 15 min, ml · kg−1 · cmH2O−1 | Sat PC, μmol/kg |

| PEEP | 4 | 3.3±0.2 | 2/2 | 0.5±0.2 | ||||

| SI | 9 | 3.5±0.2 | 8/2 | 14.7±1.1 | 15.1±1.5 | 0.6±0.2 | ||

| MV | 13 | 3.7±0.1 | 5/8 | 6.9±0.3 | 0.15±0.01 | 0.9±0.2 | ||

| MV + SI | 13 | 3.6±0.1 | 5/8 | 15.1±2.0 | 16.7±2.1 | 7.4±0.4 | 0.16±0.01 | 1.6±0.7 |

Values are means ± SE; n, no. of experiments. PT, pneumotach; RIP, respiratory impedance plethysmography; VT, tidal volume; Sat PC, saturated phosphatidylcholine; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure; SI, sustained inflation; MV, mechanical ventilation.

Physiology.

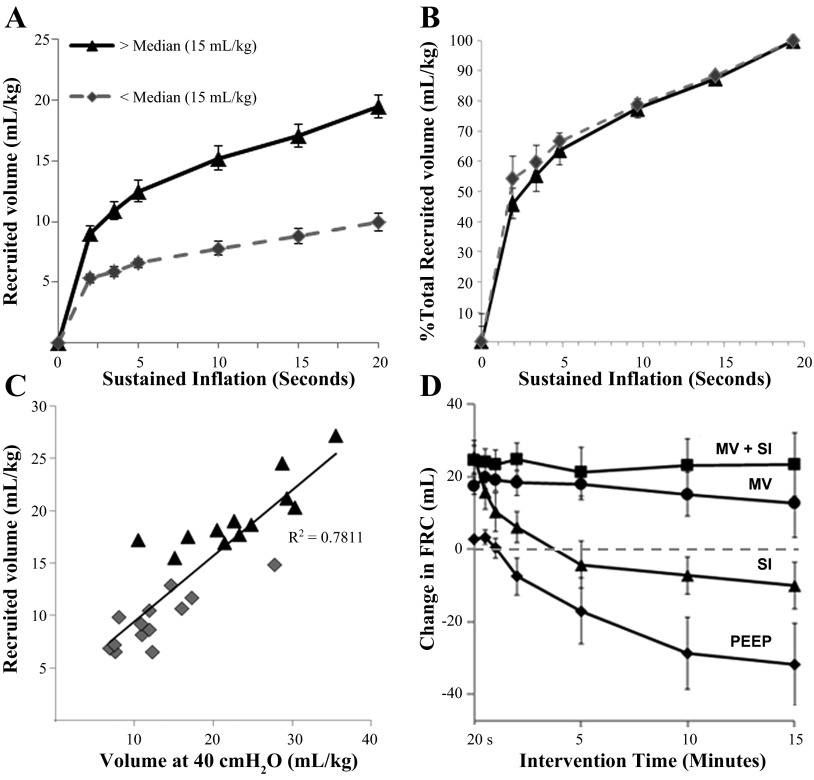

Although we recruited an average volume of 14.9 ± 1.5 ml/kg with the 20-s SI, the fetuses empirically stratified into two distinct groups above and below a median of 15 ml/kg (Fig. 1A). Independent on whether a lamb was recruited to a higher volume (19.5 ± 1.0 ml/kg) or a low volume (9.5 ± 0.7 ml/kg), the rate of inflation as a portion of the maximally recruited volume was not different between the two subgroups (Fig. 1B). We found 50% of total volume recruited by the 20-s SI occurs within the first 2 s, 65% occurred by 5 s, and 90% of total recruitment by 15 s. There were more males in the group with lower FRC recruitment (10/13 animals) vs. the higher-volume recruitment (5/12 animals). The static volume at 40 cmH2O on postmortem (V40) correlated well with total volume of recruitment in animals receiving SI (r2 = 0.78; Fig. 1C). The lambs overall were very surfactant deficient, mean 0.79 ± 0.18 μmol/kg Sat PC, but individual values ranged from 0.05 to 9.1 μmol/kg (Table 1). There was a trend for more surfactant (P = 0.11) between average Sat PC in high-volume recruitment (1.7 ± 0.7 μmol/kg) and low-volume recruitment (0.5 ± 0.1 μmol/kg) groups. There was no overall correlation between the Sat PC levels and recruitment (r2 = 0.26) for either the rate of lung recruitment or total volume recruited. Within the high- and low-SI volume cohorts, there were surfactant effects seen in the high recruitment group (linear regression slope 2.5×, r2 = 0.25) and low recruitment volume (linear regression slope 3.8×, r2 = 0.48). Therefore, although surfactant levels may play a role in volume recruited, it was not the determining factor for whether the fetus was a high- or low-volume recruiter with SI. During the ventilation period, the fetal lungs required high pressures (48 ± 1 cmH2O) to generate 7.0 ± 0.3 ml/kg. Dynamic compliance was not different between the two ventilated groups (Table 1). Dynamic compliance also correlated moderately well with V40 (data not shown, r2 = 0.64) but did not correlate with Sat PC levels, relative size of lungs (lung wt/birth wt), or gender.

Fig. 1.

Volumes recruited by sustained inflation (SI). A: SI recruited a median volume of 15 ml/kg. The lambs were stratified into two distinct groups above and below the median, with average recruitment volume (ml/kg) plotted over time. B: the percent of the maximal lung volume recruited was similar between groups over the 20-s inflation. C: the total volume recruited during SI correlated with the lung gas volume measured at 40 cmH2O (r2 = 0.78). D: respiratory impedance (RIP) tracing for 15-min period following 20 s inflation. Fetal lambs receiving positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP, 8 cmH2O) or SI had a negative functional residual capacity (FRC) on RIP tracing, suggesting reaccumulation of lung fluid. Lambs ventilated, with (VT + SI) or without SI (VT), maintain much of the FRC recruited. MV, mechanical ventilation.

RIP band analysis suggested reaccumulation of fluid within the lungs (Fig. 1D). Animals given 8 cmH2O as PEEP only had a negative change in FRC, from the RIP tracing, suggesting the average of 28 ml FLF removed before the procedure reaccumulated in the airspace during the 15-min procedure (Fig. 1D). Although the SI inflation recruited an FRC, lambs receiving SI followed only by PEEP had decreased FRC as measured by RIP over time, again suggesting a reaccumulation of fluid. Lambs receiving continued ventilation after an initial 15 min maintained FRC. FLF was easily recovered after the 15-min procedure in the PEEP and SI only groups with less fluid available in ventilated lambs. No nitrogen remained in lungs upon visual inspection at the time of autopsy in any animal, and there were no pneumothoracies.

Analysis of FLF.

SI alone increased HSP70 in FLF at 15 min (Table 2). Ventilation at birth caused the release of HSP70, HSP60, and total protein into the FLF and in BALF. Ventilation increased levels of heat shock proteins and total protein at all evaluation times, but the addition of SI had no effects on these changes. There was no correlation between the recruitment volume and HSP70, HSP60, or total protein release in the FLF or BALF.

Table 2.

Proteins released in fetal lung fluid and bronchoalveolar lavage fluids

| HSP70 |

Total Protein |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group | FLF 15 min, ng/ml | FLF 45 min, ng/ml | BALF ng/kg | HSP60 BALF, ng/kg | FLF 15 min, ng/ml | FLF 45 min, ng/ml | BALF ng/kg |

| PEEP | 5±0.4 | 33±4 | 105±5 | 21±7 | 2±0.4 | 8±3 | 42±4 |

| SI | 36±3* | 45±6 | 105±7 | 33±5 | 8±1 | 15±2 | 46±8 |

| MV | 42±2* | 50±3* | 150±10† | 316±42† | 12±1† | 26±1† | 94±7† |

| MV + SI | 48±3† | 51±3* | 156±8† | 304±50† | 13±1† | 26±1† | 100±11† |

Values are means ± SE. HSP, heat shock protein; FLF, fetal lung fluid; BALF, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid.

P < 0.05 vs. PEEP.

P < 0.05 vs. PEEP and SI groups.

Lung tissue.

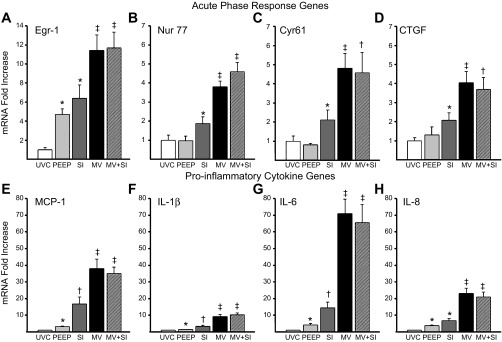

Because the control group that received PEEP only could have baseline changes, we also compared these lambs with age-matched UVC lambs (n = 10). mRNA increased for the acute-phase response genes Egr-1, Nur77, Cyr61, and CTGF (Fig. 2, A–D) with SI alone. Ventilation further increased mRNA for these acute-phase genes, with no difference between lambs receiving SI followed by ventilation and those receiving ventilation alone (Fig. 2, A–D). Proinflammatory cytokine mRNA increased with any intervention (Fig. 2, E–H) over UVC. The SI further increased MCP-1, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8 mRNA relative to UVC. A larger response was seen with continued ventilation, with no differences when SI was used before ventilation.

Fig. 2.

Acute-phase and proinflammatory cytokine mRNA responses to ventilation. A: early growth response protein 1 (Egr-1) mRNA increased with PEEP exposure and SI compared with unventilated controls (UVC), with a further increase with continued ventilation. B–D: the acute-phase genes nuclear receptor family 77 (Nur77, B), cysteine rich 61 (Cyr61, C), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF, D) all increased with SI and increased additionally with continued ventilation. E–H: similar patterns are seen with the proinflammatory cytokines monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1, E), IL-1β (F), IL-6 (G), and IL-8 (H) between groups. PEEP increased cytokines compared with controls. SI alone increased mRNA with continued ventilation, causing large increases in all cytokines. There were no differences with the addition of SI to ventilation in any acute-phase or proinflammatory cytokine mRNA. *P < 0.05 vs. UVC; †P < 0.05 vs. UVC and PEEP; ‡P < 0.05 vs. UVC, PEEP, and SI.

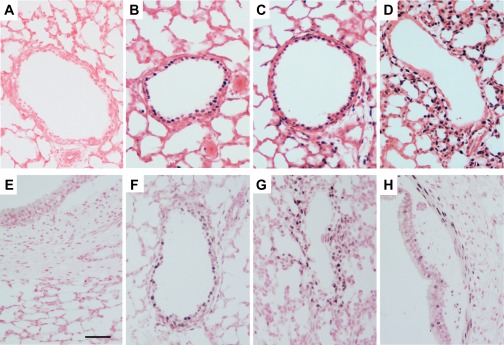

Of interest, PEEP of 8 cmH2O alone increased Egr-1 mRNA fourfold (Fig. 2A). Egr-1 was increased in the epithelial cells surrounding the moderate-sized airways in PEEP animals (Fig. 3B) compared with UVC (Fig. 3A), with increased signal in lung parenchyma with SI (Fig. 3C). Similar and more extensive activation was apparent in both ventilated groups (Fig. 3D). Nur77 protein was inconsistently increased in the epithelium of lambs receiving PEEP (Fig. 3F) and in all lambs receiving SI (Fig. 3G), but increased signal in the airway smooth muscle was only found in ventilated lambs (Fig. 3H).

Fig. 3.

Egr-1 and Nur77 protein increased around small airways with airway distention. A–D: Egr-1 protein expression in the airways. A: Egr-1 was not expressed in the epithelium of UVC. Egr-1 increases in the epithelial cells with PEEP of 8 cmH2O (B) with increased signal in peripheral lung with SI alone (C). Ventilation, with or without (D) SI, increases Egr-1 throughout the peripheral lung. E–H: Nur77 protein expression. E: Nur77 was absent in the lung of unventilated lambs. F: PEEP animals had occasional Nur77 + cells within the epithelial cells, although this was less consistent than Egr-1. G: SI alone caused an increase in Nur77 in the cells surrounding the peripheral airways. H: increased Nur77 was in the airway smooth muscle cells of only the ventilated animals.

Because no differences were seen in the lambs receiving MV, with or without SI (Table 2 and Fig. 2), we conducted a postrandomized analysis of ventilated groups (Table 3) based on V40 to determine if small differences or trends existed. V40 correlated well with SI volume (r2 = 0.78), so we stratified the mRNA measurements for the acute-phase genes and proinflammatory cytokines based on whether they were above (high V40) or below (low V40) the mean value for that group (Table 3). Animals in the SI only group with high V40 trended toward higher values for all mRNA levels. The opposite was seen with animals receiving ventilation, with or without SI. Animals with high V40 had nearly two times the V40 and approximately one-half the levels of mRNA for the acute-phase and proinflammatory genes (Table 3). When only the high-V40 or low-V40 animals were compared with each other, there remained no difference between the animals receiving SI before MV and those mechanically ventilated from birth.

Table 3.

mRNA values for ventilated animals above or below the mean volume at 40 cmH2O

| Group | M/F | V40 | Nur77 | Cyr61 | CTGF | Egr-1 | IL-1β | IL-6 | IL-8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MV low V40 | 4/3 | 10±1 | 4.8±0.6 | 6.1±1.1 | 5.2±0.4 | 13±2 | 11.4±1.4 | 86±10 | 27±3 |

| MV high V40 | 1/5 | 29±3 | 3.3±0.4 | 3.0±0.5† | 2.6±1.0 | 10±2† | 6.7±1.4 | 53±11 | 19±5 |

| MV + SI low V40 | 3/2 | 10±1 | 6.0±0.6 | 7.0±1.8 | 5.2±0.9 | 16±3 | 13.0±0.6 | 87±18 | 24±3 |

| MV + SI high V40 | 2/6 | 28±2 | 3.7±0.3‡ | 3.3±0.6‡ | 3.3±0.9 | 10±1‡ | 8.7±1.3‡ | 52±11 | 19±4 |

Values are means ± SE vs. unventilated control. M/F, male/female; V40, volume at 40 cmH2O; Nur77, nuclear receptor family 77; Cyr61, cysteine rich 61; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; Egr-1, early growth response protein 1.

P < 0.05 vs. MV low V40;

P < 0.05 vs. MV + SI low V40.

DISCUSSION

The initiation of ventilation at birth, even with VT similar to those achieved in spontaneously breathing sheep, is injurious, and this injury is likely due to shear force injury to the epithelium and from repetitive opening of distal airspaces in the fluid-filled, surfactant-deficient lung (10, 13). We used a preterm fetal sheep model to test the hypothesis that a SI to recruit FRC would decrease lung injury from subsequent ventilation at birth. The use of a SI to move the lung fluid into the distal airspaces and increase FRC was successful but did not alter indicators of injury from the ventilation that followed the SI. The range of volumes recruited by the SI stratified the lambs into groups with lower FRC recruitment volumes (9.5 ml/kg) and higher recruitment volumes (19.5 ml/kg). Stratifying ventilated lambs based on V40 demonstrated lambs with higher SI had decreased markers of injury but that SI did not alter the amplification of the injury with MV.

We used a prolonged, 20-s SI based on previous observations that an increased time constant is needed to overcome the resistance found in surfactant-deficient, fluid-filled lungs (37). A SI of 10 s or greater was needed to develop FRC in neonatal rabbits (41). Physiologically, a 30-s SI improved circulatory return in asphyxiated near-term lambs, whereas a series of five 3-s SI (as suggested by the European resuscitation guidelines) did not increase heart rate over ventilation alone (21, 30). Preterm infants have been given a SI of 10 or 15 s in clinical studies (26, 39). Using the 20-s SI, we found the lamb lungs achieved a range of FRC recruitment that stratified to either a lower recruitment volume (9.5 ml/kg) or higher recruitment volume (19.5 ml/kg). There was a higher percent of male lambs in the low recruitment groups but similar numbers in the subgroup analysis based on V40. The recruitment volume correlated well (r2 = 0.78) with the volume at 40 cmH2O, suggesting this was a maturational effect. Although the Sat PC (surfactant) amount did not determine the SI volume recruited, there were trends for increasing volume with increasing Sat PC levels. Overall, we recruited 50% of total lung recruitment by 2 s, 65% by 5 s, and 90% by 15 s. These percentages are similar to SI in preterm rabbits, which recruit 90% of FRC by 15 s (37). In these lambs, 11.8 ml/kg was recruited at 10 s, and 10.4 ml/kg was recruited in rabbits at this time point (37). Newborn lambs at 127 days gestational age took an average of 40 s to achieve a FRC of 20 ml/kg in a previous study (36). Because in our study 90% of the 20-s recruitment was achieved by 15 s, it is likely that more prolonged SI is not needed, even in the setting of severe surfactant deficiency. However, the short 3- to 5-s recruitment maneuvers that have been used clinically may be ineffective (21, 34, 37).

PEEP is important for FRC recruitment and maintenance of FRC (38, 41). After the SI, the lambs given a PEEP of 8 cmH2O for 15 min had loss of the majority of the recruitment volume as measured by RIP tracing, and the PEEP only animals had negative FRC volumes by the end of the 15 min. Assessment of ribcage perimeter (and therefore volume) is susceptible to motion artifact, but this is unlikely to explain our present findings. The loss of FRC in the PEEP only group was matched by the volume of the fluid removed before the recruitment maneuvers. Epithelial sodium channels (EnaC) normally facilitate the removal of FLF from the peripheral lung at birth (35). In this preterm fetal model, the lambs were not exposed to corticosteroids or excess maternal stress, and the ENaC channels should be minimally expressed at this gestational age (31). Even with the entire chest externalized, there may have been some pressure from the abdomen. We may not have used enough PEEP relative to the low compliance of the immature sheep lungs, since very immature rabbits given 5 cmH2O of PEEP do not develop FRC (41).

A SI alone caused a modest increase in acute-phase and proinflammatory cytokines but did not alter the increases caused by continued ventilation. We previously demonstrated that initiation of ventilation at 7 ml/kg VT was sufficient to activate acute-phase (Egr-1, Nur77, Cyr61, CTGF) responses and proinflammatory cytokine responses at birth (13). The relative increases in markers on injury we now report were similar to those achieved in fetal lambs and those ventilated after birth (13, 14, 32). The release of HSP70 into the FLF, activation of Egr-1 around smaller airways, and localization of Nur77 to the smooth muscle around larger airways are similar to other experiments and demonstrate a response to airway stretching during SI and MV (7, 11, 13, 14). We previously reported a decrease in injury response with small increases in endogenous surfactant pool sizes (9), but the average Sat PC in bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL, 0.8 μmol/kg) in these animals was considerably lower than levels that effect injury responses. The strong correlation between V40 and SI volume (r2 = 0.78) allowed us to further stratify lambs into subgroups. Although a postrandomization construct, this grouping demonstrated no differences with SI in either group (high or low V40), thus minimizing concerns that true differences were hidden among the variable lung injury responses. It should be noted for clinicians concerned about large VT during SI (2) that the animals that achieved the largest VT with the SI had decreased markers of injury. We previously had not noted the small effect of PEEP on induction of proinflammatory and acute-phase response genes but have not used a PEEP of 8 cmH2O previously. Egr-1 activation was not noted around previous experiments with fetal models using 2 or 5 cmH2O (13, 14). These findings merit further examination, since previous experiments demonstrated an increase in total protein and neutrophils in BAL of lambs ventilated with PEEP of 7 cmH2O vs. lambs ventilated with 4 cmH2O (29).

The effects of SI on lung injury responses are important because clinicians have begun to use SI in VLBW infants. The European resuscitation guidelines suggest that five 2- to 3-s SI be given in infants with poor respiratory effort (41). These recommendations are based on a few small human studies showing benefits in VLBW infants (24). Although their earlier retrospective study showed a difference with SI, Lindner et al. did not find a difference in 61 infants randomized to SI or control on intubation rate at 48 h using a SI of 15 s (24, 25). Lista et al. found a decrease in duration of MV and need for surfactant in 89 infants receiving a 15-s SI compared with historical controls (26). te Pas and Walther randomized 207 infants (gestational age 25 to 33 wk) to 10 s SI at 20 cmH2O then continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) vs. CPAP alone and found fewer were intubated at 72 h of life and a shorter duration of MV (39). When following the European guidelines in 27 VLBW, Schilleman et al. found in infants with a minimal mask leak, an average SI volume of 8.7 ml/kg was achieved, which is similar to our volumes at 2.5- to 3.5-s values (34). Because of large mask leaks, excessively high VT were not given, even when SI occurred during a spontaneous breath (34). Most studies have used a T-piece resuscitator because of its ability to more consistently deliver the pressure for a prolonged SI than other devices (20). Our data would support the continued study of prolonged (>10 s) SI in VLBW infants, although proportionally less recruitment will be seen after 15 s.

One of the limitations of the study is the high pressure (50 cmH2O) needed for the SI in very preterm lungs. As we previously reported, ventilation of preterm fetal lambs requires higher pressures to achieve the target VT than are needed in slightly more mature lambs ventilated after birth (4, 12). Similar high pressures were used in preterm rabbits during SI, with animals weighing 36 g requiring 35 cmH2O to aerate the lungs (37). Because volutrauma may be more injurious to the lung than pressure (8), we continuously monitored the VT and adjusted the PIP to maintain 6–7 ml/kg. Even though the placental blood flow and fetal circulation remained intact, ventilation of the fetal lung increases pulmonary blood flow and aids with the cardiovascular transition in the newborn lamb (1). Any differences caused by this altered physiology should have similar effects in all intervention groups.

In conclusion, in preterm fetal sheep, SI recruited a variable FRC (mean 15 ml/kg), but this required a longer inflationary time than used in clinical practice. Although a SI activated a mild proinflammatory response, it did not alter the acute-phase responses to subsequent ventilation in any of the subgroup analysis. Contrary to our hypothesis, a SI to recruit FRC did not decrease injury from MV at birth.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-HD-072842 (A. H. Jobe) and K08-HL-097085 (N. H. Hillman) and NHMRC Career development grant 1045824 (P. B. Noble).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: N.H.H., M.W.K., P.B.N., S.G.K., and A.H.J. conception and design of research; N.H.H., M.W.K., and A.H.J. performed experiments; N.H.H., P.B.N., and A.H.J. analyzed data; N.H.H., P.B.N., S.G.K., and A.H.J. interpreted results of experiments; N.H.H. prepared figures; N.H.H. and A.H.J. drafted manuscript; N.H.H., M.W.K., P.B.N., S.G.K., and A.H.J. edited and revised manuscript; N.H.H., M.W.K., P.B.N., S.G.K., and A.H.J. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bhatt S, Alison BJ, Wallace EM, Crossley KJ, Gill AW, Kluckow M, Te Pas AB, Morley CJ, Polglase GR, Hooper SB. Delaying cord clamping until ventilation onset improves cardiovascular function at birth in preterm lambs. J Physiol 591: 2113–2126, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjorklund LJ, Ingimarsson J, Curstedt T, Larsson A, Robertson B, Werner O. Lung recruitment at birth does not improve lung function in immature lambs receiving surfactant. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 45: 986–993, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cools F, Askie LM, Offringa M, Asselin JM, Calvert SA, Courtney SE, Dani C, Durand DJ, Gerstmann DR, Henderson-Smart DJ, Marlow N, Peacock JL, Pillow JJ, Soll RF, Thome UH, Truffert P, Schreiber MD, Van Reempts P, Vendettuoli V, Vento G. Elective high-frequency oscillatory vs. conventional ventilation in preterm infants: a systematic review and meta-analysis of individual patients' data. Lancet 375: 2082–2091, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dargaville PA, Tingay DG. Lung protective ventilation in extremely preterm infants. J Paediatr Child Health 48: 740–746, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreyfuss D, Saumon G. Ventilator-induced lung injury: lessons from experimental studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 157: 294–323, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fanaroff AA, Stoll BJ, Wright LL, Carlo WA, Ehrenkranz RA, Stark AR, Bauer CR, Donovan EF, Korones SB, Laptook AR, Lemons JA, Oh W, Papile LA, Shankaran S, Stevenson DK, Tyson JE, Poole WK. Trends in neonatal morbidity and mortality for very low birthweight infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 196: 147 e141–e148, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foti G, Cereda M, Sparacino ME, De Marchi L, Villa F, Pesenti A. Effects of periodic lung recruitment maneuvers on gas exchange and respiratory mechanics in mechanically ventilated acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) patients. Intensive Care Med 26: 501–507, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hernandez LA, Peevy KJ, Moise AA, Parker JC. Chest wall restriction limits high airway pressure-induced lung injury in young rabbits. J Appl Physiol 66: 2364–2368, 1989 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hillman N, Kallapur SG, Pillow JJ, Polglase GR, Nitsos I, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. Inhibitors of inflammation and endogenous surfactant pool size as modulators of lung injury with initiation of ventilation in preterm sheep. Resp Res 11: 1–8, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hillman NH, Kallapur SG, Pillow JJ, Moss TJ, Polglase GR, Nitsos I, Jobe AH. Airway injury from initiating ventilation in preterm sheep. Pediatr Res 67: 60–65, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillman NH, Kallapur SG, Pillow JJ, Nitsos I, Polglase GR, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. Inhibitors of inflammation and endogenous surfactant pool size as modulators of lung injury with initiation of ventilation in preterm sheep (Abstract). Respir Res 11: 151, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hillman NH, Moss TJ, Kallapur SG, Bachurski C, Pillow JJ, Polglase GR, Nitsos I, Kramer BW, Jobe AH. Brief, large tidal volume ventilation initiates lung injury and a systemic response in fetal sheep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 176: 575–581, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hillman NH, Moss TJ, Nitsos I, Jobe AH. Moderate tidal volumes and oxygen exposure during initiation of ventilation in preterm fetal sheep. Pediatr Res 72: 593–599, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillman NH, Nitsos I, Berry C, Pillow JJ, Kallapur SG, Jobe AH. Positive end-expiratory pressure and surfactant decrease lung injury during initiation of ventilation in fetal sheep. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 301: L712–L720, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hooper SB, Kitchen MJ, Wallace MJ, Yagi N, Uesugi K, Morgan MJ, Hall C, Siu KK, Williams IM, Siew M, Irvine SC, Pavlov K, Lewis RA. Imaging lung aeration and lung liquid clearance at birth. FASEB J 21: 3329–3337, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jobe AH, Newnham JP, Willet KE, Moss TJ, Ervin MG, Padbury JF, Sly PD, Ikegami M. Endotoxin induced lung maturation in preterm lambs is not mediated by cortisol. Am J Respirt Crit Care Med 162: 1656–1661, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kallapur SG, Nitsos I, Moss TJ, Polglase GR, Pillow JJ, Cheah FC, Kramer BW, Newnham JP, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. IL-1 mediates pulmonary and systemic inflammatory responses to chorioamnionitis induced by LPS. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 179: 955–961, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kallapur SG, Willet KE, Jobe AH, Ikegami M, Bachurski C. Intra-amniotic endotoxin: Chorioamnionitis precedes lung maturation in preterm lambs. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 280: L527–L536, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kattwinkel J, Perlman JM, Aziz K, Colby C, Fairchild K, Gallagher J, Hazinski MF, Halamek LP, Kumar P, Little G, McGowan JE, Nightengale B, Ramirez MM, Ringer S, Simon WM, Weiner GM, Wyckoff M, Zaichkin J. Neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Pediatrics 126: e1400–e1413, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klingenberg C, Dawson JA, Gerber A, Kamlin CO, Davis PG, Morley CJ. Sustained inflations: comparing three neonatal resuscitation devices. Neonatology 100: 78–84, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klingenberg C, Sobotka KS, Ong T, Allison BJ, Schmolzer GM, Moss TJ, Polglase GR, Dawson JA, Davis PG, Hooper SB. Effect of sustained inflation duration; resuscitation of near-term asphyxiated lambs. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 98: F222–F227, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramer BW, Ikegami M, Moss TJ, Nitsos I, Newnham JP, Jobe AH. Endotoxin-induced chorioamnionitis modulates innate immunity of monocytes in preterm sheep. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 171: 73–77, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kramer BW, Moss TJ, Willet KE, Newnham JP, Sly PD, Kallapur SG, Ikegami M, Jobe AH. Dose and time response after intraamniotic endotoxin in preterm lambs. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 982–988, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lindner W, Hogel J, Pohlandt F. Sustained pressure-controlled inflation or intermittent mandatory ventilation in preterm infants in the delivery room? A randomized, controlled trial on initial respiratory support via nasopharyngeal tube. Acta Paediatr 94: 303–309, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindner W, Vossbeck S, Hummler H, Pohlandt F. Delivery room management of extremely low birth weight infants: spontaneous breathing or intubation? Pediatrics 103: 961–967, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lista G, Fontana P, Castoldi F, Cavigioli F, Dani C. Does sustained lung inflation at birth improve outcome of preterm infants at risk for respiratory distress syndrome? Neonatology 99: 45–50, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lowry OH, Rosebrough NJ, Farr AL, Randall RJ. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem 193: 265–275, 1951 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monkman S, Kirpalani H. PEEP–a “cheap” and effective lung protection. Paediatr Respir Rev 4: 15–20, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Naik AS, Kallapur SG, Bachurski CJ, Jobe AH, Michna J, Kramer BW, Ikegami M. Effects of ventilation with different positive end-expiratory pressures on cytokine expression in the preterm lamb lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164: 494–498, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nolan JP, Soar J, Zideman DA, Biarent D, Bossaert LL, Deakin C, Koster RW, Wyllie J, Bottiger B, Group ERCGW. European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2010 Section 1. Executive summary. Resuscitation 81: 1219–1276, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olver RE, Walters DV, SMW Developmental regulation of lung liquid transport. Annu Rev Physiol 66: 77–101, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polglase GR, Hillman NH, Pillow JJ, Nitsos I, Newnham JP, Knox CL, Kallapur SG, Jobe AH. Ventilation mediated injury following preterm delivery of Ureaplasma parvum colonized fetal lambs. Pediatr Res 67: 630–635, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Polglase GR, Miller SL, Barton SK, Baburamani AA, Wong FY, Aridas JD, Gill AW, Moss TJ, Tolcos M, Kluckow M, Hooper SB. Initiation of resuscitation with high tidal volumes causes cerebral hemodynamic disturbance, brain inflammation and injury in preterm lambs. PLoS One 7: e39535, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schilleman K, van der Pot CJ, Hooper SB, Lopriore E, Walther FJ. Evaluating manual inflations and breathing during mask ventilation in preterm infants at birth. J Pediatr 162: 457–463, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siew ML, Wallace MJ, Allison BJ, Kitchen MJ, te Pas AB, Islam MS, Lewis RA, Fouras A, Yagi N, Uesugi K, Hooper SB. The role of lung inflation and sodium transport in airway liquid clearance during lung aeration in newborn rabbits. Pediatr Res 73: 443–449, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sobotka KS, Hooper SB, Allison BJ, Te Pas AB, Davis PG, Morley CJ, Moss TJ. An initial sustained inflation improves the respiratory and cardiovascular transition at birth in preterm lambs. Pediatr Res 70: 56–60, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.te Pas AB, Siew M, Wallace MJ, Kitchen MJ, Fouras A, Lewis RA, Yagi N, Uesugi K, Donath S, Davis PG, Morley CJ, Hooper SB. Effect of sustained inflation length on establishing functional residual capacity at birth in ventilated premature rabbits. Pediatr Res 66: 295–300, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.te Pas AB, Siew M, Wallace MJ, Kitchen MJ, Fouras A, Lewis RA, Yagi N, Uesugi K, Donath S, Davis PG, Morley CJ, Hooper SB. Establishing functional residual capacity at birth: the effect of sustained inflation and positive end-expiratory pressure in a preterm rabbit model. Pediatr Res 65: 537–541, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.te Pas AB, Walther FJ. A randomized, controlled trial of delivery-room respiratory management in very preterm infants. Pediatrics 120: 322–329, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vyas H, Milner AD, Hopkins IE. Intrathoracic pressure and volume changes during the spontaneous onset of respiration in babies born by cesarean section and by vaginal delivery. J Pediatr 99: 787–791, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wheeler K, Wallace M, Kitchen M, Te Pas A, Fouras A, Islam M, Siew M, Lewis R, Morley C, Davis P, Hooper S. Establishing lung gas volumes at birth: interaction between positive end-expiratory pressures and tidal volumes in preterm rabbits. Pediatr Res 73: 734–741, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]