Abstract

Emerging evidence supports a potential therapeutic role of relaxin in fibrotic diseases, including chronic kidney disease. Relaxin is a pleiotropic hormone, best characterized for its role in the reproductive system; however, recent studies have demonstrated a role of relaxin in the cardiorenal system. Both relaxin and its receptor, RXFP1, are expressed in the kidney, and relaxin has been shown to play a role in renal vasodilation, in sodium excretion, and as an antifibrotic agent. Together, these findings suggest that the kidney is a target organ of relaxin. Therefore, the purpose of this review is to describe the functional and structural impacts of relaxin treatment on the kidney and to discuss evidence that relaxin prevents disease progression in several experimental models of kidney disease. In addition, this review will present potential mechanisms that are involved in the therapeutic actions of relaxin.

Keywords: glomerular sclerosis, tubulointersitital fibrosis, renal function, nitric oxide, matrix metalloproteinases, transforming growth factor-β, oxidative stress

relaxin is a 6-kda peptide in the insulin-relaxin hormone superfamily that was discovered in the 1920s by Hisaw and colleagues. These investigators found that there was a substance in the serum of pregnant guinea pigs and rabbits that induced relaxation of the pubic ligament and remodeling of connective tissue when injected into virgin guinea pigs. This substance was subsequently extracted from porcine corpora lutea and rabbit placenta and named “relaxin” (28, 38). In the decades following the discovery of relaxin, the peptide was found to have several effects on the reproductive tract in estrogen-primed mammals, including elongation of the mouse interpubic ligament (33), inhibition of spontaneous uterine contractions in guinea pigs (46), and cervical softening in cattle (31). More recent technological advances (including improved isolation/purification of proteins, recombinant protein technologies, and genome sequencing) have greatly increased our understanding of the relaxin system and identified new targets for the actions of relaxin throughout the body (78).

In humans, the relaxin peptide family consists of relaxin-1 (H1), relaxin-2 (H2), relaxin-3 (H3), and the insulin-like peptides INSL3, INSL4, INSL5, and INSL6 (5, 39, 89). H2 relaxin, the major circulating relaxin in humans (which corresponds to relaxin-1 in nonprimates) (68), is the focus of this review and will be referred to simply as “relaxin” throughout. Relaxin is produced and secreted by the corpus luteum during pregnancy in pigs, rats, mice, and humans (77), but relaxin is also produced in the male reproductive tract and in the heart, brain, arteries, and kidneys of both males and females. Although relaxin is produced locally in various tissues in both males and females, there is no conclusive evidence that relaxin is a circulating hormone in males, and circulating relaxin is derived only from the corpus luteum in females during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle and during pregnancy.

There are four relaxin peptide family receptors (RXFPs): RXFP1 (also called LGR7), RXFP2 (also called LGR8), RXFP3 (also called GPCR135), and RXFP4 (also called GPCR142) (5, 6). These G protein-coupled receptors predominantly bind relaxin, INSL3, relaxin-3, and INSL-5, respectively. Relaxin can bind to both RXFP1 and RXFP2, but RXFP1 is the predominant receptor for relaxin (7). While it has been demonstrated that the RXFP1 receptor has widespread distribution throughout the body, including the brain, kidney, heart, arteries, and male and female reproductive systems (1, 5, 6, 21, 59, 64), further study is needed to identify the cell types within tissues that express RXFP1 and the factors that regulate the relaxin receptors (5).

Localization: More Than Just a Pregnancy Hormone

The highest production of relaxin is from the corpus luteum and placenta during pregnancy, consistent with its role in preparing for parturition (78), and relaxin is also produced by the male reproductive tract (2). However, this review will focus on the effects of relaxin outside of the reproductive tract. It has been shown that relaxin is expressed in the human heart (23) and kidney (67, 74); in the mouse brain, lung, liver, skin, thymus, spleen, heart, and kidney (25, 71, 74); and the rat heart, brain, pancreas, liver, and kidney (32, 61). Relaxin expression has also been demonstrated in arteries (renal, mesenteric, and aortae) from mice, rats, and wallabies (59).

Identification and characterization of the relaxin family of receptors were not possible until genome sequencing identified a family of leucine-rich repeats containing guanidine nucleotide binding (G protein)-coupled receptors (LGRs). The relaxin receptor, originally discovered as LGR-7 (41) and now known as RXFP1, is widely distributed in both reproductive and nonreproductive tissues. In humans, RXFP1 expression has been detected in the brain, kidney, testis, placenta, uterus, ovary, adrenal, prostate, skin, liver, lung, and heart (41). In rodents, RXFP1 expression has been identified in the kidney (40), heart (40, 44, 45, 48, 60, 76 81), arteries (59), brain (40, 44, 45, 47, 48, 60, 76, 81), pituitary (45), skin (40, 76), lung (62, 76), intestine (40, 76), colon (40), and adrenal glands (40).

With regard to kidney-specific localization of relaxin and its receptors, Samuel et al. (74) identified relaxin mRNA by RT-PCR in the mouse kidney cortex and medulla, and immunostaining confirmed local renal expression of relaxin (67). Furthermore, RXFP1 mRNA has been identified in kidneys from both humans and rodents (8, 10, 41, 70), and both relaxin and RXFP1 are also expressed in small renal arteries of both male and female mice, rats, and tammar wallabies (59). Immunohistochemical analyses have further localized the expression of this receptor in the proximal tubules, inner medullary collecting ducts, and mesangial cells (10, 27). However, these localization studies must be interpreted with caution as many of the commercial antibodies used to detect the relaxin receptors have not been fully validated. Therefore, further studies are needed to specifically define the cell types within the kidney that express the RXFP1 receptor.

More convincing evidence for the presence of a local relaxin-RXFP1 system within the kidney has been derived from the study of functional effects of relaxin within the kidney. Previous studies in rats have demonstrated that relaxin causes an increase in renal plasma flow and glomerular filtration rate, a decrease in myogenic reactivity in small renal arteries, and an increase in sodium excretion (10, 11, 17). In addition, a study in a small group of human volunteers demonstrated that intravenous relaxin infusion over 5 h resulted in an increase (∼47%) in renal blood flow, although no change in glomerular filtration rate was observed (79). Furthermore, this acute administration of relaxin resulted in increased urinary sodium excretion and increased clearance and fractional excretion of sodium, with no significant changes in potassium excretion. It should be noted that in this study, each volunteer was his or her own control, and no time control was performed. Together, these findings suggest that the kidney may be a source of localized relaxin production and/or a target organ for relaxin activity.

Evidence of a Renoprotective Action of Relaxin

While a major focus of relaxin research has been examining the effects of relaxin during pregnancy (15, 16, 78), there are many studies that suggest that the relaxin system is important in nonreproductive functions as well. Recent evidence implicates a protective role for relaxin in cardiorenal disease due to its vasodilatory, antifibrotic, and angiogenic properties (55, 78); therefore, relaxin is an attractive agent for the treatment of chronic kidney disease. Furthermore, there is evidence that acute (20) or long-term (18) administration of relaxin can attenuate the renal vasoconstrictor response to ANG II.

Strong evidence for a potential antifibrotic role of relaxin in the kidney is provided by studies in knockout mouse models. Male Rln1 −/− mice and Rxfp1 −/− mice undergo an age-related progression of fibrosis in several reproductive and nonreproductive organs, including the kidney (1, 72). Interestingly, renal fibrosis was only observed in the male, but not female, Rln1 −/− mice, indicating that other sex hormones may play a role in mediating or protecting against the renal fibrotic response. Indeed, a recent study demonstrated that castration protected relaxin-deficient mice from age-related renal and cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis, and testosterone replacement exacerbated the injury (37). The age-related fibrosis in male Rln1 −/− mice was associated with renal hypertrophy, an increase in total collagen content, interstitial fibrosis, glomerular sclerosis, and a decline in renal function (as measured by creatinine clearance). One of the most fascinating and promising findings from this study was that administration of recombinant H2 relaxin for only 2 wk resulted in significant reversal of this established renal fibrosis. More recently, the role of endogenous relaxin was further investigated in these relaxin knockout mice challenged with unilateral ureteric obstruction (UUO). In the Rln1−/− mice, there was greater collagen and interstitial myofibroblast accumulation 3 days post-UUO compared with the wild-type mice, but after 10 days, this protective effect was lost, and there was no difference in the degree of fibrosis (36). This suggests that relaxin plays a role in the early development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis, and more recent work demonstrated that the effects of relaxin are due to its ability to suppress cell (fibroblast) proliferation, myofibroblast differentiation, and collagen production (34, 35), in the absence of any effects on apoptosis.

Many studies in rats have also demonstrated renoprotective effects of relaxin administration, and these effects have been shown in both hypertensive and normotensive models of kidney injury. Using the bromoethylamine model of renal papillary necrosis characterized by interstitial fibrosis, mononuclear cell infiltrate, and tubular cell atrophy, Garber et al. (29) demonstrated that administration of exogenous relaxin increased creatinine clearance and decreased albuminuria, interstitial fibrosis, macrophage infiltration, and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) staining (29). Shortly thereafter, the same group examined the effects of relaxin on two models of renal mass reduction: 1) surgical excision of the poles of one kidney and removal of the contralateral kidney, and 2) infarction of the poles of one kidney and removal of the contralateral kidney (30). While both models exhibit renal dysfunction and glomerular injury, the injury is more severe in the infarction model, which also develops hypertension. While the protective effects of relaxin treatment in the infarction model may be secondary to the antihypertensive effects of relaxin treatment, findings from the normotensive excision model demonstrated that relaxin reduces glomerular sclerosis and improves renal function in a blood pressure-independent manner as well. Relaxin also prevented the development of glomerular sclerosis and interstitial fibrosis and improved renal function in a rat model of antiglomerular basement membrane disease (56). Furthermore, only 10 days of treatment with relaxin reversed the decline in renal function and the structural damage that progressed over 12 mo in the Munich-Wistar rat, a rat model of progressive kidney disease during aging (19), suggesting that relaxin may not only delay progression of renal disease but that agents targeting the renal relaxin system may be useful in the reversal of established renal injury. Finally, our results have shown that relaxin reduces blood pressure, renal structural injury, and albuminuria in ANG II-induced hypertension (75).

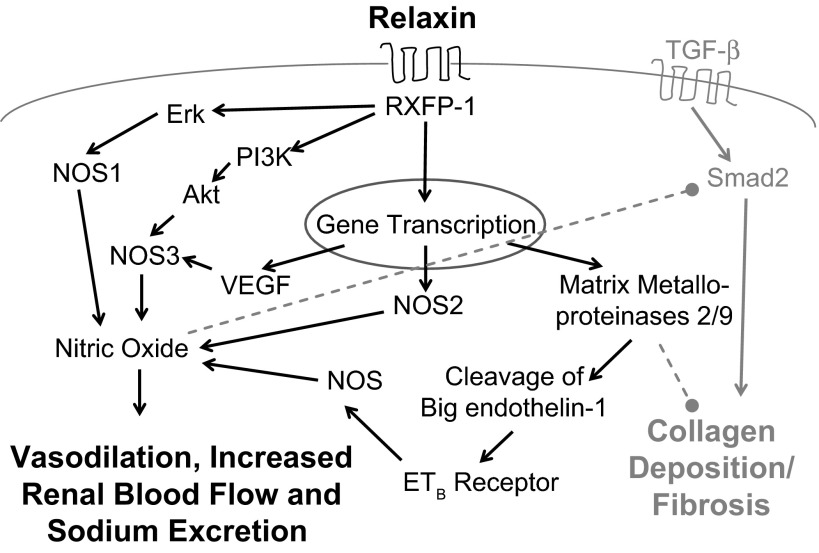

Genetic models of hypertension have also been used to demonstrate the cardiorenal protective effects of relaxin. In spontaneously hypertensive rats, relaxin reduced renal and cardiac fibrosis, even though the effect of relaxin on blood pressure is not consistent in this model (20, 49, 80, 91), and relaxin treatment in Dahl salt-sensitive rats reduced blood pressure and glomerular and tubulointerstitial injury when rats were given a high-salt diet (92). Together, these studies have demonstrated the potential of relaxin as an antifibrotic therapy, and they have provided some insights into the potential mechanisms of action of this peptide hormone (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Working model of renoprotective pathways activated by relaxin. Relaxin binds to its receptor, RXFP-1, to activate kinase-signaling pathways (Erk, PI3K, Akt) and gene transcription resulting in activation of the three nitric oxide synthase (NOS) isoforms and production of nitric oxide (NO). Increased NO bioavailability results in vasodilation, increased renal blood flow, increased sodium excretion, and inhibition of TGF-β-Smad2 signaling. Transcription of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and matrix metalloproteinases is also stimulated. VEGF further stimulates NO production, and matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) result in cleavage of 1) big-endothelin-1 to stimulate the endothelin type B receptor, further stimulating NO production via an as yet unspecified NOS isoform and 2) collagen. Overall, these pathways result in improved renal function and reduced renal fibrosis. Solid black arrows indicate stimulatory pathways, and dashed gray lines indicate inhibitory pathways.

Mechanisms Involved in the Protective Effects of Relaxin

Stimulation of nitric oxide production.

Nitric oxide (NO) is an important regulator of blood pressure and regional blood flow, vascular smooth muscle proliferation, platelet aggregation, and leukocyte adhesion (57), and NO plays an important role in the regulation of renal function and the maintenance of renal health. In the kidney, the beneficial effects of NO include renal vasodilation and inhibition of growth of contractile cells, extracellular matrix production, oxidative stress, and sodium reabsorption (9). NO deficiency is associated with endothelial dysfunction and the development of hypertension, and chronic kidney disease is often associated with NO deficiency (9). There is increasing evidence that some actions of relaxin are mediated through increased abundance or activity of the NO synthase (NOS) enzymes. Various studies have implicated all three of the NOS enzymes in the NO-dependent actions of relaxin, and these differences may depend upon the cell type studied (3). The NO stimulatory actions of relaxin in reproductive and nonreproductive organs were recently reviewed by Baccari and Bani (3), so this review will focus on the effects of relaxin and RXFP1 activation specifically on the renal NO system.

In the kidney, relaxin is a potent vasodilator, likely acting by increasing NO production (18); however, the molecular mechanism by which relaxin activates the NO system and the NOS isoform(s) involved are unknown. Both in vivo studies and work in cultures of renal myofibroblasts have demonstrated that relaxin activates NOS1 (neuronal NOS) and signals via the NO-cGMP pathway to inhibit TGF-β signaling, myofibroblast differentiation, and collagen synthesis (35, 58). Chow et al. (14) reported that relaxin stimulation of the RXFP1 receptor in rat renal myofibroblasts activated Gαs and GαB proteins, resulting in phosphorylation of ERK and increased expression of NOS1 but not NOS2 (inducible NOS) (14). Work by Conrad (15) has also implicated a role of NOS activation in the renal vasodilatory response to relaxin in a two-phase response: 1) binding of relaxin to the RXFP1 receptor rapidly induces phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt (PKB)-dependent phosphorylation and activation of NOS3 (endothelial NOS), and 2) stimulation of vascular gelatinases results in stimulation of endothelin B receptor-induced NO production for a sustained vasodilatory response (15), although the NOS isoform involved in this sustained response has not been identified. Recent studies from our laboratory have demonstrated that while relaxin is antihypertensive and renoprotective during ANG II-induced hypertension in rats, relaxin was ineffective in preventing hypertension or renal injury during l-NAME administration, suggesting that the antihypertensive and renoprotective effects of relaxin are dependent on a functional NOS system (75). In this study, we found that relaxin had no effect on the expression of NOS1 or NOS3 in the kidney cortex during ANG II-dependent hypertension; however, others have shown that relaxin increases expression of both NOS1 and NOS3 in Dahl salt-resistant and Dahl salt-sensitive rats (92). This study also revealed that pharmacological inhibition of NOS attenuated the antihypertensive effects of relaxin in Dahl salt-sensitive rats during high-salt intake, further supporting a critical role of NO in the protective effects of relaxin.

It is also possible that relaxin decreases oxidative stress to indirectly increase NO bioavailability. In experimental ischemia/reperfusion studies, relaxin decreased lipid peroxidation and 8-hydroxy-2′-deoxyguanosine levels and increased expression of manganese superoxide dismutase in ileal tissue from animals subjected to splanchnic artery occlusion (53) and decreased lipid peroxidation in myocardial tissue after ischemia reperfusion injury (52). We also observed that relaxin treatment resulted in a reduction in systemic oxidative stress markers, urinary excretion of hydrogen peroxide, and thiobarbituric acid reactive substances, and renal cortex nitrotyrosine content in ANG II-dependent hypertension (75). Because the observed reduction in oxidative stress following relaxin treatment may be the result of either a decrease in the production of reactive oxygen species or an increase in the ability to neutralize reactive oxygen species, future studies should more thoroughly examine the mechanisms responsible for the potential antioxidant mechanisms of relaxin.

Increased NO may also play an important role in the regulation of inflammatory pathways in cardiorenal diseases. Bani et al. (4) demonstrated that relaxin-induced NO production resulted in decreased MCP-1 production in the rat heart. Brecht et al. (13) recently confirmed these findings by demonstrating dose-dependent decreases in TNF-α-stimulated MCP1 and VCAM expression following relaxin treatment in human umbilical vein endothelial cells and aortic smooth muscle cells. Furthermore, in vitro relaxin treatment restored NOS3 expression and activity, stimulated NOS3 phosphorylation at the activating sites Ser-1177 and Ser-633, and attenuated phosphorylation of the inhibitory Thr-495 site on NOS3 in rat aortic rings treated with TNF-α (22). These changes were also accompanied by reductions in TNF-α-induced oxidative stress and improved vascular reactivity to ACh. Future studies should further investigate the role of relaxin in inhibiting inflammatory pathways in the vasculature, as well as in other target organs.

Antifibrotic Actions of Relaxin

Inhibition of TGF-β.

One of the predominant factors that contributes to progressive renal fibrosis is the proinflammatory and fibrogenic cytokine TGF-β (12). TGF-β is a central player in damage to the glomeruli, tubules, and interstitium of the kidney, and inhibition of TGF-β in experimental animal models has been shown to attenuate renal injury (51). Therefore, an important mechanism of action of relaxin lies in its ability to inhibit TGF-β signaling. Relaxin decreased TGF-β expression and activity in renal cells both in vivo and in vitro (29, 34, 35, 58). This inhibition of TGF-β signaling was shown to result from decreased Smad-2 phosphorylation (34, 58) and resulted in the inhibition of myofibroblast differentiation and collagen production in renal (54) and cardiac (70) fibroblasts. McDonald et al. (56) also demonstrated that relaxin decreased TGF-β-induced fibronectin levels and promoted fibronectin degradation in cultured renal fibroblasts. These effects of relaxin may be dependent on NO production, as recent studies have demonstrated that the inhibition of TGF-β signaling by relaxin is dependent upon NO derived from NOS1 (neuronal NOS) and NO-cGMP signaling in renal myofibroblasts (58).

Stimulation of matrix metalloproteinases.

Renal fibrosis not only results from the overproduction of extracellular matrix proteins but also from impaired degradation of matrix proteins. The latter results from a downregulation of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) or upregulation of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases (TIMPs) (26). The antifibrotic effects of relaxin also include stimulation of MMPs and inhibition of TIMP activity to promote matrix degradation (66). Relaxin has been shown to stimulate the secretion and activity of several MMPs, including MMP-1, MMP-2, MMP-9, and MMP-13 (42, 43, 50, 54, 63, 70, 86, 87, 90). In cultured fibroblasts, relaxin stimulated MMP-2 (70), and relaxin activated MMP2 in experimental models of cardiac, renal, and airway fibrosis (49, 65) in vivo. Recent findings suggest that the stimulation of MMP expression and activity may be dependent upon activation of NOS1 and NOS2, NO-cGMP signaling, and inhibition of TGF-β signaling (14). In addition, relaxin has been shown to inhibit TIMP-1 activity both in vitro (86) and in an experimental model of diabetic cardiomyopathy (69).

In addition to the role of relaxin-stimulated MMP activity in the regulation of renal fibrosis, this pathway is also important in the vasodilatory actions of relaxin. Stimulation of vascular MMP-2 and MMP-9 by relaxin is critical for the sustained vasodilatory response to relaxin in the renal vasculature (15). These vascular gelatinases cleave endothelin-1 precursor, Big-Endothelin, to ET1–32, which then activates the endothelial endothelin B receptor, promoting vasodilation. Danielson et al. (19) demonstrated the importance of gelatinases in the acute vasodilation and hyperfiltration following relaxin administration in the aging Munich-Wistar rat. Gelatinase inhibition attenuated improvement in renal function following 24–72 h treatment with relaxin; however, the improvements in renal function following chronic (20 day) relaxin treatment were not inhibited by short-term gelatinase inhibition, indicating that the long-term effects of relaxin treatment are due to structural changes within the kidney.

Perspectives and Significance: Toward Relaxin-Based Therapeutics in Cardiorenal Diseases

While relaxin was originally discovered as a reproductive hormone, and later, both porcine derived and recombinant human relaxin were (unsuccessfully) tested as a therapeutic for progressive systemic sclerosis (for review, see Ref. 78), current trials of recombinant human relaxin are focused on cardiovascular pathologies. A randomized phase II clinical trial showed that relaxin is safe and shows trends of clinical improvement in patients with acute heart failure and mild-to-moderate renal insufficiency, including improvement on symptoms, such as dyspnea, blood vessel congestion, and peripheral edema. (82). Recently released findings from the phase III RELAX-AHF demonstrated that treatment with serelaxin (synthetic recombinant human relaxin, Novartis) for up to 48 h improves heart failure symptoms and 180-day survival compared with placebo in patients with acute heart failure (83). In addition, a small pilot study evaluated the safety and tolerability of recombinant human relaxin in patients with stable congestive heart failure. It was found that relaxin is vasodilatory in heart failure patients at doses ranging from 10 to 960 μg·kg−1·day−1, as indicated by increases in cardiac index and decreases in pulmonary wedge pressure and circulating N-terminal prohormone of brain natriuretic peptide (NT-BNP). At the lower doses of relaxin, the study revealed improvement in renal function (reduced creatinine, uric acid, and blood urea nitrogen levels) in these patients (24, 84). Recombinant human relaxin is also being tested as a potential therapy in women with preeclampsia, a condition of new-onset hypertension and proteinuria during pregnancy. Because relaxin is a naturally occurring peptide in pregnancy that causes both systemic and renal vasodilation, phase I safety studies are planned to determine the effects of relaxin treatment on uteroplacental blood flow, maternal blood pressure, and renal function in patients with preeclampsia (88).

As clinical studies on relaxin move forward, a better understanding of its mechanisms of action is required, especially in regard to the hormone's effects on renal function. Indeed, one of the most consistent findings from multiple trials using recombinant H2 relaxin has been its ability to improve creatinine clearance. In healthy human volunteers, acutely administered relaxin (5 h) increased renal plasma flow by ∼50%, with no concomitant fall in blood pressure (79). These findings highlight the potential of relaxin-based therapies in patients with impaired renal function. Treatments for chronic kidney disease, including the current standard of care treatment with agents that block the renin-angiotensin system, are limited in that they can slow the progression to end-stage renal disease but cannot prevent progression or reverse established disease (85). As relaxin has been shown to 1) not only slow but also reverse injury and improve function in experimental models of kidney disease and 2) reduce the systemic sequelae of kidney disease (including hypertension and cardiac and vascular remodeling), further investigation into the renoprotective effects of this hormone alone and in combination with current therapies in models of fibrotic kidney disease, including hypertensive and diabetic nephropathies, is needed.

GRANTS

J. M. Sasser is supported by Grant 11SDG6910000 from the American Heart Association and Grant K01-DK-095018 from the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.M.S. conception and design of research; J.M.S. interpreted results of experiments; J.M.S. prepared figures; J.M.S. drafted manuscript; J.M.S. edited and revised manuscript; J.M.S. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agoulnik AI. Relaxin and Related Peptides. Springer Series: Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (612). New York: Landes Bioscience/Springer Science + Business Media, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agoulnik AI. Relaxin and related peptides in male reproduction. Adv Exp Med Biol 612: 49–64, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baccari MC, Bani D. Relaxin and nitric oxide signaling. Curr Protein Pept Sci 9: 638–645, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bani D, Masini E, Bello MG, Bigazzi M, Sacchi TB. Relaxin protects against myocardial injury caused by ischemia and reperfusion in rat heart. Am J Pathol 152: 1367–1376, 1998 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bathgate RA, Ivell R, Sanborn BM, Sherwood OD, Summers RJ. International Union of Pharmacology LVII: recommendations for the nomenclature of receptors for relaxin family peptides. Pharmacol Rev 58: 7–31, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bathgate RA, Ivell R, Sanborn BM, Sherwood OD, Summers RJ. Receptors for relaxin family peptides. Ann NY Acad Sci 1041: 61–76, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bathgate RA, Halls ML, van der Westhuizen ET, Callander GE, Kocan M, Summers RJ. Relaxin family peptides and their receptors. Physiol Rev 9: 405–80, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bathgate RA, Samuel CS, Burazin TC, Layfield S, Claasz AA, Reytomas IG, Dawson NF, Zhao C, Bond C, Summers RJ, Parry LJ, Wade JD, Tregear GW. Human relaxin gene 3 (H3) and the equivalent mouse relaxin (M3) gene. Novel members of the relaxin peptide family. J Biol Chem 277: 1148–1157, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baylis C. Nitric oxide deficiency in chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 294: F1–F9, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bogzil AH, Ashton N. Relaxin-induced changes in renal function and RXFP1 receptor expression in the female rat. Ann NY Acad Sci 1160: 313–316, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bogzil AH, Eardley R, Ashton N. Relaxin-induced changes in renal sodium excretion in the anesthetized male rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R322–R328, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Border WA, Noble NA. TGF-β in kidney fibrosis: a target for gene therapy. Kidney Int 51: 1388–1396, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brecht A, Bartsch C, Baumann G, Stangl K, Dschietzig T. Relaxin inhibits early steps in vascular inflammation. Regul Pept 166: 76–82, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chow BS, Chew EG, Zhao C, Bathgate RA, Hewitson TD, Samuel CS. Relaxin signals through a RXFP1-pERK-nNOS-NO-cGMP-dependent pathway to up-regulate matrix metalloproteinases: the additional involvement of iNOS. PLos One 7: e42714, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Conrad KP. Unveiling the vasodilatory actions and mechanisms of relaxin. Hypertension 56: 2–9, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conrad KP. Maternal vasodilation in pregnancy: the emerging role of relaxin. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R267–R275, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Conrad KP, Novak J. Emerging role of relaxin in renal and cardiovascular function. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 287: R250–R261, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Danielson LA, Sherwood OD, Conrad KP. Relaxin is a potent renal vasodilator in conscious rats. J Clin Invest 103: 525–533, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Danielson LA, Welford A, Harris A. Relaxin improves renal function, and histology in aging Munich-Wistar rats. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 1325–1333, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Debrah DO, Conrad KP, Jeyabalan A, Danielson LA, Shroff SG. Relaxin increases cardiac output and reduces systemic arterial load in hypertensive rats. Hypertension 46: 745–750, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dschietzig T, Bartsch C, Baumann G, Stangl K. Relaxin-a pleiotropic hormone and its emerging role for experimental and clinical therapeutics. Pharmacol Ther 112: 38–56, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dschietzig T, Brecht A, Bartsch C, Baumann G, Stangl K, Alexiou K. Relaxin improves TNF-α-induced endothelial dysfunction: the role of glucocorticoid receptor and phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase signaling. Cardiovasc Res 95: 97–107, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dschietzig TC, Richter C, Bartsch C, Laule M, Armbruster FP, Baumann G, Stangl K. The pregnancy hormone relaxin is a player in human heart failure. FASEB J 15: 2187–2195, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dschietzig T, Teichman S, Unemori E, Wood S, Boehmer J, Richter C, Baumann G, Stangl K. Intravenous recombinant human relaxin in compensated heart failure: a safety, tolerability, and pharmacodynamic trial. J Card Fail 15: 182–190, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Du XJ, Samuel CS, Gao XM, Zhao L, Parry LJ, Tregear GW. Increased myocardial collagen and ventricular diastolic dysfunction in relaxin deficient mice: a gender-specific phenotype. Cardiovasc Res 57: 395–404, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eddy AA. Molecular basis of renal fibrosis. Pediatr Nephrol 15: 290–301, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ferreira VM, Gomes TS, Reis LA, Ferreira AT, Razvickas CV, Schor N, Boim MA. Receptor-induced dilatation in the systemic and intrarenal adaptation to pregnancy in rats. PLos One 4: e4845, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fevold HL, Hisaw FL, Meyer RK. The relaxative hormone of the corpus luteum: its purification and concentration. J Am Chem Soc 52: 3340–3348, 1930 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garber SL, Mirochnik Y, Brecklin CS, Unemori EN, Singh AK, Slobodskoy L, Grove BH, Arruda JA, Dunea G. Relaxin decreases renal interstitial fibrosis and slows progression of renal disease. Kidney Int 59: 876–882, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garber SL, Mirochnik Y, Brecklin C, Slobodskoy L, Arruda JA, Dunea G. Effect of relaxin in two models of renal mass reduction. Am J Nephrol 23: 8–12, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Graham EF, Dracy AE. The effect of relaxin and mechanical dilatation of the bovine cervix. J Dairy Sci 36: 772–777, 1953 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gunnersen JM, Crawford RJ, Tregear GW. Expression of the relaxin gene in rat tissues. Mol Cell Endocrinol 110: 55–64, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hall K. The effects of pregnancy and relaxin on the histology of the pubic symphysis of the mouse. J Endocrinol 5: 174–185, 1947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Heeg MH, Koziolek MJ, Vasko R, Schaefer L, Sharma K, Muller GA, Strutz F. The antifibrotic effects of relaxin in human renal fibroblasts are mediated in part by inhibition of the Smad2 pathway. Kidney Int 68: 96–109, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hewitson TD, Ho WY, Samuel CS. Antifibrotic properties of relaxin: in vivo mechanism of action in experimental renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Endocrinology 151: 4938–4948, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hewitson TD, Mookerjee I, Masterson R, Zhao C, Tregear GW, Becker GJ, Samuel CS. Endogenous relaxin is a naturally occurring modulator of experimental renal tubulointerstitial fibrosis. Endocrinology 148: 660–669, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hewitson TD, Zhao C, Wigg B, Lee SW, Simpson ER, Boon WC, Samuel CS. Relaxin and castration in male mice protect from, but testosterone exacerbates, age-related cardiac and renal fibrosis, whereas estrogens are an independent determinant of organ size. Endocrinology 153: 188–199, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hisaw F. Experimental relaxation of the pubic ligament of the guinea pig. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 23: 661–663, 1926 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsu SY. New insights into the evolution of the relaxin-LGR signaling system. Trends Endocrinol Metab 14: 303–309, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hsu SY, Kudo M, Chen T, Nakabayashi K, Bhalla A, van der Spek PJ, van Duin M, Hsueh AJ. The three subfamilies of leucine rich repeat-containing G protein-coupled receptors (LGR): identification of LGR6 and LGR7 and the signaling mechanism for LGR7. Mol Endocrinol 14: 1257–1271, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hsu SY, Nakabayashi K, Nishi S, Kumagai J, Kudo M, Sherwood OD, Hsueh AJ. Activation of orphan receptors by the hormone relaxin. Science 295: 671–674, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeyabalan A, Novak J, Danielson LA, Kerchner LJ, Opett SL, Conrad KP. Essential role for vascular matrix metalloproteinases-2 in relaxin-induced renal vasodilation, hyperfiltration, and reduced myogenic reactivity of small arteries. Circ Res 93: 1249–1257, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kapila S, Wang W, Uston K. Matrix metalloproteinase induction by relaxin causes cartilage matrix degradation in target synovial joints. Ann NY Acad Sci 1160: 322–328, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kompa AR, Samuel CS, Summers RJ. Inotropic responses to human gene 2 (B29) relaxin in a rat model of myocardial infarction (MI): effect of pertussis toxin. Br J Pharmacol 137: 710–718, 2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krajnc-Franken MA, van Disseldorp AJ, Koenders JE, Mosselman S, van Duin M, Gossen JA. Impaired nipple development and parturition in LGR7 knockout mice. Mol Cell Biol 24: 687–696, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Krantz JC, Jr, Bryant HH, Carr CJ. The action of aqueous corpus luteum extract upon uterine activity. Surg Gynecol Obstet 90: 372–375, 1950 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kubota Y, Temelcos C, Bathgate RA, Smith KJ, Scott D, Zhao C, Hutson JM. The role of insulin 3, testosterone, Mullerian inhibiting substance and relaxin in rat gubernacular growth. Mol Hum Reprod 8: 900–905, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kumagai JS, Hsu SY, Matsumi H, Roh JS, Fu P, Wade JD, Bathgate RA, Hsueh AJ. INSL3/Leydig insulin-like peptide activates the LGR8 receptor important in testis descent. J Biol Chem 277: 31283–31286, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lekgabe ED, Kiriazis H, Zhao C, Xu Q, Moore XL, Su Y, Bathgate RA, Du XJ, Samuel CS. Relaxin reverses cardiac and renal fibrosis in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 46: 412–418, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lenhart JA, Ryan PL, Ohleth KM, Palmer SS, Bagnell CA. Relaxin increases secretion of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 during uterine and cervical growth and remodeling in the pig. Endocrinology 142: 3941–3949, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.López-Hernández FJ, López-Novoa JM. Role of TGF-β in chronic kidney disease: an integration of tubular, glomerular and vascular effects. Cell Tissue Res 347: 141–154, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Masini E, Bani D, Bello MG, Bigazzi M, Mannaioni PF, Sacchi TB. Relaxin counteracts myocardial damage induced by ischemia-reperfusion in isolated guinea pig hearts: evidence for an involvement of nitric oxide. Endocrinology 138: 4713–4720, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Masini E, Cuzzocrea S, Mazzon E, Muia C, Vannacci A, Fabrizi F, Bani D. Protective effects of relaxin in ischemia/reperfusion-induced intestinal injury due to splanchnic artery occlusion. Br J Pharmacol 148: 1124–1132, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Masterson R, Hewitson TD, Kelynack K, Martic M, Parry L, Bathgate R, Darby I, Becker G. Relaxin down-regulates renal fibroblast function and promotes matrix remodelling in vitro. Nephrol Dial Transplant 19: 544–552, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.McGuane JT, Parry LJ. Relaxin and the extracellular matrix: molecular mechanisms of action and implications for cardiovascular disease. Expert Rev Mol Med 7: 1–18, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McDonald GA, Sarkar P, Rennke H, Unemori E, Kalluri R, Sukhatme VP. Relaxin increases ubiquitin-dependent degradation of fibronectin in vitro and ameliorates renal fibrosis in vivo. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 285: F59–F67, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moncada S, Higgs EA. Nitric oxide and the vascular endothelium. Hand Exp Pharmacol 176: 213–254, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mookerjee I, Hewitson TD, Halls ML, Summers RJ, Mathai ML, Bathgate RA, Tregear GW, Samuel CS. Relaxin inhibits renal myofibroblast differentiation via RXFP1, the nitric oxide pathway, and Smad2. FASEB J 23: 1219–1229, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Novak J, Parry LJ, Matthews JE, Kerchner LJ, Indovina K, Hanley-Yanez K, Doty KD, Debrah DO, Shroff SG, Conrad KP. Evidence for local relaxin ligand-receptor expression and function in arteries. FASEB J 20: 2352–2362, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Osheroff PL, Cronin MJ, Lofgren JA. Relaxin binding in the rat heart atrium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 89: 2384–2388, 1992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Osheroff PL, Ho WH. Expression of relaxin mRNA and relaxin receptors in postnatal and adult rat brains and hearts. Localization and developmental patterns. J Biol Chem 268: 15193–15199, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Osheroff PL, Ling VT, Vandlen RL, Cronin MJ, Lofgren JA. Preparation of biologically active 32P-labeled human relaxin. Displaceable binding to rat uterus, cervix, and brain. J Biol Chem 265: 9396–9401, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Palejwala S, Weiss G, Goldsmith LT. Relaxin stimulates expression of matrix metalloproteinase 2 by human lower uterine segment fibroblasts. J Soc Gynecol Invest 7: 124A, 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park JI, Chang CL, Hsu SY. New insights into biological roles of relaxin and relaxin-related peptides. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 6: 291–296, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Royce SG, Miao YR, Lee M, Samuel CS, Tregear GW, Tang ML. Relaxin reverses airway remodeling and airway dysfunction in allergic airways disease. Endocrinology 150: 2692–2699, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Samuel CS. Relaxin: antifibrotic properties and effects in models of disease. Clin Med Res 3: 241–249, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Samuel CS, Hewitson TD. Relaxin in cardiovascular and renal disease. Kidney Int 69: 1498–1502, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Samuel CS, Hewitson TD, Unemori EN, Tang ML. Drugs of the future: the hormone relaxin. Cell Mol Life Sci 64: 1539–1557, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Samuel CS, Hewitson TD, Zhang Y, Kelly DJ. Relaxin ameliorates fibrosis in experimental diabetic cardiomyopathy. Endocrinology 149: 3286–3293, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Samuel CS, Unemori EN, Mookerjee I, Bathgate RA, Layfield SL, Mak J, Tregear GW, Du XJ. Relaxin modulates cardiac fibroblast proliferation, differentiation, and collagen production and reverses cardiac fibrosis in vivo. Endocrinology 145: 4125–4133, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Samuel CS, Zhao C, Bathgate RA, Bond CP, Burton MD, Parry LJ, Summers RJ, Tang ML, Amento EP, Tregear GW. Relaxin deficiency in mice is associated with an age-related progression of pulmonary fibrosis. FASEB J 17: 121–123, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Samuel CS, Zhao C, Bathgate RA, DU XJ, Summers RJ, Amento EP, Walker LL, McBurnie M, Zhao L, Tregear GW. The relaxin gene-knockout mouse: A model of progressive fibrosis. Ann NY Acad Sci 1041: 173–181, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Samuel CS, Zhao C, Bond CP, Hewitson TD, Amento EP, Scott RJ, Layfield S, Riesewijk A, Morita H, Tregear GW, Bathgate RA. Identification and characterization of the mouse and rat relaxin receptors as the novel orthologues of human leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 7. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 31: 828–832, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Samuel CS, Zhao C, Bond CP, Hewitson TD, Amento EP, Summers RJ. Relaxin-1-deficient mice develop an age-related progression of renal fibrosis. Kidney Int 65: 2054–2064, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sasser JM, Molnar M, Baylis C. Relaxin ameliorates hypertension and increases nitric oxide metabolite excretion in angiotensin II but not N(ω)-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester hypertensive rats. Hypertension 58: 197–204, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Scott DJ, Layfield S, Riesewijk A, Morita H, Tregear GW, Bathgate RA. Identification and characterization of the mouse and rat relaxin receptors as the novel orthologues of human leucine-rich repeat-containing G-protein-coupled receptor 7. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 31: 828–832, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sherwood OD. Relaxin. In: The Physiology of Reproduction, edited by Knobil E, Neill JC. New York: Raven Press, New York, 1994, p. 1861–1009 [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sherwood OD. Relaxin's physiological roles and other diverse actions. Endocr Rev 25: 205–234, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Smith MC, Danielson LA, Conrad KP, Davison JM. Influence of recombinant human relaxin on renal hemodynamics in healthy volunteers. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 3192–3197, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.St-Louis J, Massicotte G. Chronic decrease of blood pressure by rat relaxin in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Life Sci 37: 1351–1357, 1985 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tan YY, Wade JD, Tregear GW, Summers RJ. Quantitative autoradiographic studies of relaxin binding in rat atria, uterus and cerebral cortex: characterization and effects of oestrogen treatment. Br J Pharmacol 127: 91–98, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Teerlink JR, Metra M, Felker GM, Ponikowski P, Voors AA, Weatherley BD, Marmor A, Katz A, Grzybowski J, Unemori E, Teichman SL, Cotter G. Relaxin for the treatment of patients with acute heart failure (Pre-RELAX-AHF): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, dose-finding phase IIb study. Lancet 373: 1429–1439, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Teerlink JR, Cotter G, Davison BA, Felker GM, Filippatos G, Greenberg BH, Ponikowski P, Unemori E, Voors AA, Adams KF, Jr, Dorobantu MI, Grinfeld LR, Jondeau G, Marmor A, Masip J, Pang PS, Werdan K, Teichman SL, Trapani A, Bush CA, Saini R, Schumacher C, Severin TM, Metra M. RELAXin in Acute Heart Failure (RELAX-AHF) Investigators. Serelaxin, recombinant human relaxin-2, for treatment of acute heart failure (RELAX-AHF): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 81: 29–39, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Teichman SL, Unemori E, Dschietzig T, Conrad K, Voors AA, Teerlink JR, Felker GM, Metra M, Cotter G. Relaxin, a pleiotropic vasodilator for the treatment of heart failure. Heart Fail Rev 14: 321–329, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Turner JM, Bauer C, Abramowitz MK, Melamed ML, Hostetter TH. Treatment of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int 81: 351–62, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Unemori EN, Amento EP. Relaxin modulates synthesis and secretion of procollagenase and collagen by human dermal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 265: 10681–10685, 1990 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Unemori EN, Pickford LB, Salles AL, Piercy CE, Grove BH, Erikson ME, Amento EP. Relaxin induces an extracellular matrix-degrading phenotype in human lung fibroblasts in vitro and inhibits lung fibrosis in a murine model in vivo. J Clin Invest 98: 2739–2745, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Unemori E, Sibai B, Teichman SL. Scientific rationale and design of a phase I safety study of relaxin in women with severe preeclampsia. Ann NY Acad Sci 1160: 381–384, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wilkinson TN, Speed TP, Tregear GW, Bathgate RA. Evolution of the relaxin-like peptide family. BMC Evol Biol 5: 14, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Williams EJ, Benyon RC, Trim N, Hadwin R, Grove BH, Arthur MJ, Unemori EN, Iredale JP. Relaxin inhibits effective collagen deposition by cultured hepatic stellate cells and decreases rat liver fibrosis in vivo. Gut 49: 577–583, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xu Q, Chakravorty A, Bathgate RA, Dart AM, Du XJ. Relaxin therapy reverses large artery remodeling and improves arterial compliance in senescent spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 55: 1260–1266, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoshida T, Kumagai H, Suzuki A, Kobayashi N, Ohkawa S, Odamaki M, Kohsaka T, Yamamoto T, Ikegaya N. Relaxin ameliorates salt-sensitive hypertension and renal fibrosis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 2190–2197, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]