Abstract

In humans, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) activity in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and the nucleus accumbens (NAc) appears to reflect affective and motivational aspects of pain. The responses of this reward-aversion circuit to relief of pain, however, have not been investigated in detail. Moreover, it is not clear whether brain processing of the affective qualities of pain in animals parallels the mechanisms observed in humans. In the present study, we analyzed fMRI blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) activity separately in response to an onset (aversion) and offset (reward) of a noxious heat stimulus to a dorsal part of a limb in both humans and rats. We show that pain onset results in negative activity change in the NAc and pain offset produces positive activity change in the ACC and NAc. These changes were analogous in humans and rats, suggesting that translational studies of brain circuits modulated by pain are plausible and may offer an opportunity for mechanistic investigation of pain and pain relief.

Keywords: anterior cingulate cortex, nucleus accumbens, aversion and reward, pain, fMRI

substantial progress in our understanding of pain perception, processing, and modulation in the brain has been achieved using neuroimaging techniques in humans. Pain is multidimensional with sensory, affective, and motivational aspects that are processed in part by separate regions of the brain. Thus the thalamus, primary and secondary sensory cortex, and posterior insular cortex have consistently been implicated in sensory-discriminative processing (Bingel et al. 2004; Peyron et al. 1999), whereas the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), anterior insula, and prefrontal cortex are thought to be relevant to the cognitive-affective modulation of pain (Apkarian et al. 2005; Rainville et al. 1997). The mesolimbic reward circuit comprising projections from the midbrain ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens (NAc) plays an important role in motivational aspects of pain (Geha et al. 2008; Oluigbo et al. 2012; Scott et al. 2006). A functional link between the NAc and the ACC in reward processing has been reported (Albrechet-Souza et al. 2013; Parkinson et al. 2000; Wacker et al. 2009), supporting the possibility that activity in these brain regions could reflect affective and motivational aspects of pain.

In contrast to human studies, investigations of the affective-motivational dimension of pain in animals, for example, analyses of motivated behaviors and animal brain neuroimaging, have been scarce. Animal investigations may allow mechanistic studies that are not feasible in humans, including exploration of brain circuits relevant to pain as well as their modulation by analgesic treatments and drug side effects. Whether affective processing of pain in animals could be analogous to the complex and unique human pain experience is not known. Increased cortical complexity in higher species is obvious, and the limitations of animal models in studying affective components of pain must be acknowledged. Nevertheless, the basic homeostatic and reward brain circuits underlying motivated behavior are fundamental to survival and appear to be highly conserved between humans and rats (Craig 2003; Murray et al. 2011). Moreover, the imaging studies evaluating pain processing in rodents have produced remarkably consistent results and confirmed activation of the same brain regions commonly activated in human imaging of pain (Thompson and Bushnell 2012).

The ACC is engaged in ascending processing of nociceptive input as well as in regulation of the subjective feelings of pain unpleasantness. Positron emission tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies in humans have repeatedly demonstrated activation of the ACC by acute nociceptive stimuli (Peyron et al. 2000). The activity in the ACC correlated with the subject's ratings of pain unpleasantness (Rainville et al. 1997), supporting the role of the ACC in affective dimensions of pain. Consistent with this observation, lesioning the rostral ACC in rats prevents formalin-induced conditioned place aversion (CPA) (Johansen et al. 2001) and blocks conditioned place preference (CPP) resulting from relief of ongoing pain (Qu et al. 2011). Because the ACC receives direct nociceptive inputs from the ascending spinothalamocortical pathway, these findings are consistent with the notion that nociceptive input to the ACC increases the activity in the region and that this response in turn results in increased pain unpleasantness. The ACC receives connections from other cortical and subcortical regions, including the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and the NAc (Cauda et al. 2011), that may modulate its activity. Thereby the ACC can integrate cognitive, emotional, and motivational factors such as expectations, mood, and anxiety to regulate the subjective pain experience. Additionally, the ACC activity has been linked to the subjective experience of pleasure for a variety of stimuli including odors, tastes, and water in thirsty subjects (Wacker et al. 2009).

Relief of pain is rewarding in both humans (Grill and Coghill 2002; Leknes et al. 2011) and animals (Navratilova et al. 2012). We have previously shown that relief of ongoing postsurgical pain produces CPP in rats and activates mesolimbic reward circuit (Navratilova et al. 2012). In the present study we analyzed in parallel in both rat and human fMRI blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) signals following an acute thermal noxious stimulation. Because the ACC and NAc both respond to aversive as well as rewarding (pleasant) stimuli, we hypothesized that the onset (aversive event) and offset (rewarding event) of an acute noxious stimulus would produce differential fMRI activations in these brain structures. In a phasic experiment of noxious heat in humans, we have previously demonstrated a change of valence of the fMRI signal in the NAc (i.e., a negative BOLD response following the application of noxious heat and a positive BOLD response when the stimulation is terminated) (Becerra and Borsook 2008). Given the obvious differences in brains between humans and rodents, we have restricted this report to the ACC and NAc. Thus the objective of this study was 1) to investigate fMRI BOLD responses of the ACC and NAc to aversive and rewarding stimuli and 2) to determine if the underlying circuitry for reward (pain offset) and aversion (pain onset) are similar across species.

METHODS

The study followed National Institutes of Health guidelines for the use of animals in research and was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. The human study was approved by the Institutional Review Board. Although it is not possible to match pain intensity experiences across species, we selected a temperature that seems to produce a moderate to strong pain stimulus: in humans we have ample experience that 46°C produces a pain intensity of 7/10, moderate to high pain. In rats, Baliki et al. (2005) have demonstrated on hot-plate experiments that at temperatures above 48°C, rats indicate a significant pain response. Furthermore, to allow for more direct comparison between animal and human studies, the rat fMRI was performed in acclimated, trained, awake animals.

Humans

Ten male, right-handed healthy controls were recruited for this study (age = 40.5 ± 10.2 yr, mean ± SD). Subjects were screened for mental health state and to be MRI safe.

Heat stimulation.

Humans underwent a painful fMRI scan using a TSA-2000 pain device (Medoc, Haifa, Israel). Three stimuli at 46°C were delivered for 25 s with 30 s of neutral (32°C) temperature to the dorsum of the left hand with a 3 × 3-cm2 Peltier thermode. Three stimuli were used for each subject (see Fig. 1).

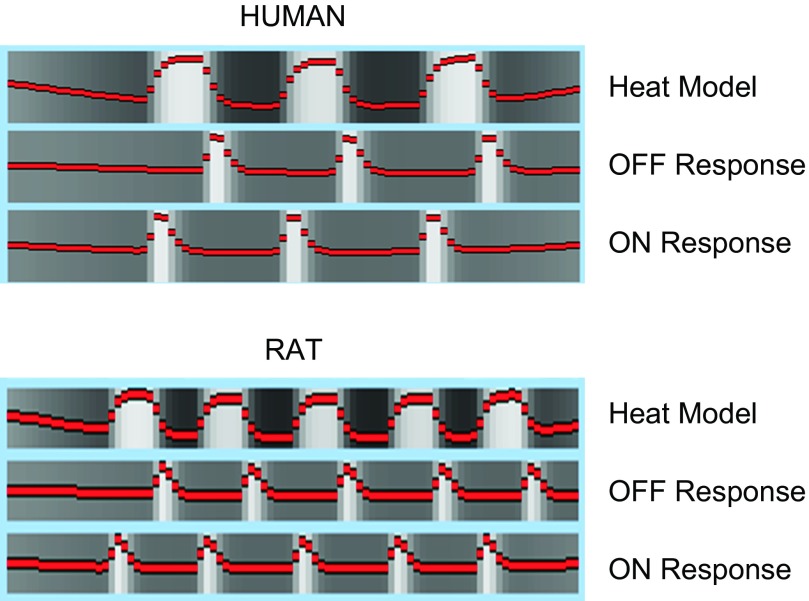

Fig. 1.

Analysis model. The model of the thermal stimulus is depicted, as well as the explanatory variable for the onset and offset of pain.

Imaging.

Human imaging was acquired in a 3-T Siemens Trio scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). An MPRAGE (magnetization-prepared rapid acquisition gradient echo) sequence was used to acquire structural images [TR/TE/flip = 25 ms/5 ms/35°; field of view (FOV) = 20 cm; slice thickness = 1.2 mm; in-plane resolution = 1.2 mm; matrix = 256 × 256]. Functional scans were performed using a gradient echo EPI (echo-planar imaging) sequence (TR/TE = 2.5 s/30 ms; slice thickness = 3 mm; in-plane resolution = 3.125 × 3.125 mm), performed on a 41-slice oblique (perpendicular to the anterior-posterior commissure line) prescription.

Animals

Twelve male Sprague-Dawley rats were used for this study with weight in the range 300–350 g. Rats were acclimated to the animal facilities for 24–48 h after arrival. They were briefly anesthetized with 2% isoflurane, loaded into cradles similar to the one used for imaging, and placed in a box with speakers playing recorded scanner noises for 1 h; rats were awake during the whole procedure. This procedure was repeated for 3 consecutive days. On the fourth day, the animals were scanned. For the imaging session, rats were briefly anesthetized with 2% isoflurane and secured on head-and-body holders. They were left to wake up for 30 min before the imaging session begun.

Heat stimulation.

A homemade small hollow copper block was positioned below the rat dorsum of the left hind paw. The block's temperature was controlled by a circulating thermal bath. The temperature can be regulated from 0 to 50°C (Becerra et al. 2011a). For these experiments, 5 stimuli 21 s long with variable interstimulus times (14–24 s) were used. A temperature of 48°C was applied with resting temperatures of 32°C (see Fig. 1).

Imaging.

Imaging data were acquired on a 4.7-T Brucker Scanner (Bruker Biospin, Billerica, MA). A multiconcentric dual-coil small animal restrainer (Insight NeuroImaging Systems) was used to perform the imaging studies. Imaging consisted of acquisition of anatomic scans and sensory functional scans. High-resolution anatomic scans were acquired using a RARE (rapid acquisition with relaxation enhancement) sequence with a FOV of 3 cm, 1-mm-thick slices, and 256 × 256-pixel in-plane resolution. Functional MRI data were acquired using an EPI sequence [TR/TE = 3 s/12 ms; FOV = 3.0 cm, matrix = 64 × 64 (0.46875-mm in-plane resolution); 15 1.5-mm axial slices] with 90 time points.

fMRI Analysis

Details of fMRI data analysis have been published elsewhere (Becerra et al. 2011a; Upadhyay et al. 2010). Briefly, FSL tools (http://www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl) were utilized for preprocessing [brain extraction, motion correction, spike identification, and spatial (humans, 5 mm; rats, 0.6 mm) and temporal (100 s) filtering]. Statistical analysis was carried out using a general linear model approach. The interest of this study was to detect changes associated with the onset and offset of the noxious stimulus. Accordingly, explanatory variables (EV) were created based on the temporal profile of the noxious stimuli. A rapid response to onset and a separate response to offset were modeled in addition to the heat response (Fig. 1). These EVs were convoluted with the standard hemodynamic response (Becerra et al. 2011a; Upadhyay et al. 2010). To account for residual motion effects as well as potential spikes in the data, motion parameters and spikes were added as confounding EVs. Functional data were coregistered to an atlas [human atlas provided by FSL analysis tools package; rat MRI atlas developed in house and based on a histological atlas (Becerra et al. 2011b)]. For registration, the FSL linear image registration tool (FLIRT) was used with 12 degrees of freedom and trilinear interpolation (Jenkinson et al. 2002). Human functional data was interpolated to 2 mm3 voxels and rat data to 1-mm slices with 0.1171875-mm in-plane resolution (Becerra et al. 2011b).

Statistical results were grouped using a fixed-effects approach. For statistical inference, statistical maps for onset and offset were thresholded with the use of a mixture-modeling approach (implemented in our laboratory) that accounts for multiple comparisons as well as potential statistical model violations (Pendse et al. 2009). Briefly, mixture-modeling determines a series of Gaussians that model the null component and identifies non-null ones that can be ascribed to activation and deactivation components; each voxel is classified and receives a probability that it belongs to a particular class (deactivation, null, activation). Voxels probabilities are thresholded at 0.5 to determine the class to which they belong. Classification maps are then used to determine statistically significant activity. Group statistical maps were overlaid over a standard MRI brain that has been coregistered to a histological atlas (Becerra et al. 2011b) for NAc and ACC identification. The present report concentrates on activation in nucleus accumbens and cingulate cortex, and all other brain activities have not been examined and/or their data are not presented.

RESULTS

No human scans were eliminated due to excessive motion artifacts. Two of the 12 rats were excluded as a result of movements during the scan (>0.5 mm).

Humans

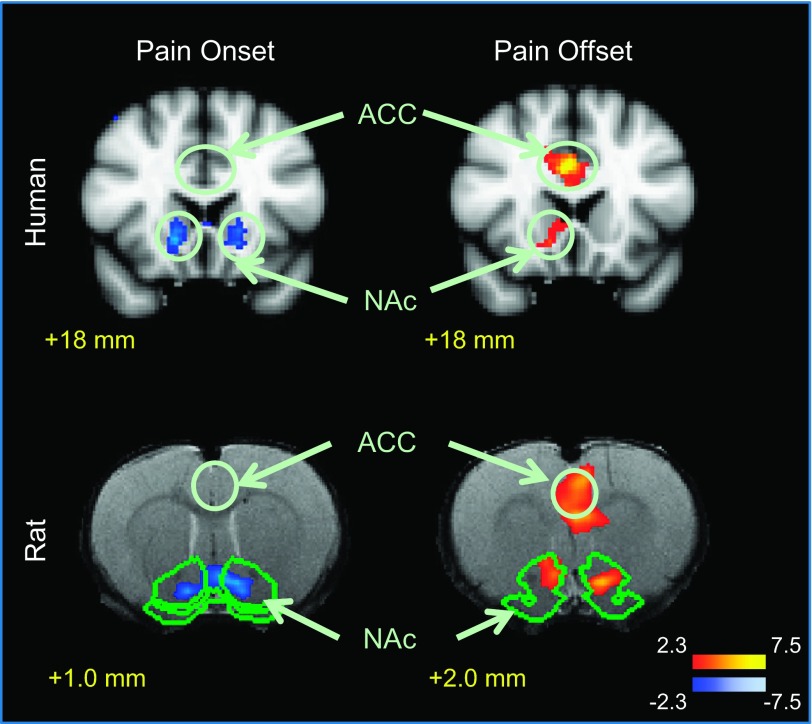

Group results for onset/offset activations in the ACC in humans revealed no significant changes at the onset of the painful stimulus, whereas significant activation was observed at the pain offset (pain relief) (Fig. 2 and Table 1). In the NAc, the onset of the painful stimulus resulted in significant deactivation (negative change) of the fMRI signal, whereas significant activation was observed in response to the offset of pain (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Human and rat responses to the onset and offset of pain. Activation in response to the offset of pain was detected in the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) in humans and rats as well as in the nucleus accumbens (NAc). The onset of pain induced a deactivation response in the brain that was detected in the NAc.

Table 1.

NAc and ACC activations

| Rat Brain Structure | Laterality | Zstat | X, mm | Y, mm | Z, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | |||||

| NAc | R | −4.14 | 1.17 | 1.64 | 1.00 |

| L | −4.28 | −1.29 | 1.99 | 1.00 | |

| Offset | |||||

| NAc | R | 2.83 | 0.70 | 2.46 | 2.00 |

| L | 3.49 | −1.52 | 2.23 | 2.00 | |

| ACC | R | 3.21 | −0.47 | 6.80 | 3.00 |

| Human Brain Structure | Laterality | Zstat | X, mm | Y, mm | Z, mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Onset | |||||

| NAc | R | −3.32 | 14 | 18 | −6 |

| L | −2.75 | −16 | 18 | −8 | |

| Offset | |||||

| NAc | R | 2.56 | 12 | 18 | −8 |

| ACC | R | 4.4 | 4 | 18 | 28 |

Data are coordinates of maximum activation/deactivation in the nucleus accumbens (NAc) and anterior cingulate cortex (ACC). Laterality to right (R) or left (L) side is indicated. Zstat is the thresholded Z statistic. Coordinates in humans refer to the standard Montreal Neurological Institute atlas. Coordinates in rats correspond to the rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson 2004).

Rats

We have reported brain activations in response to noxious heat in rats in a separate study (Becerra et al. 2011b). We observed activity in sensory-discriminative, affective-emotional, descending, and autonomic pathways. In the present study, similar to our results in humans, we did not observe any significant change in the activity of the ACC in rats at stimulus onset, whereas the offset of a noxious thermal stimulus increased activation in the anterior cingulate/motor area. In the NAc, the onset of the noxious stimulus resulted in a decrease in fMRI signal response, which was most prominent in the core of the structure (Fig. 2 and Table 1). Deactivation was also observed in cortical (sensory) and subcortical areas (caudate/putamen) with the onset of painful stimulus. Functional MRI response associated with noxious stimulus offset resulted in positive activation in an area of the NAc that corresponds to the core region (Fig. 2 and Table 1).

DISCUSSION

In the current BOLD fMRI study we observed analogous brain activity changes in response to aversive (pain onset) and rewarding (pain offset) thermal stimuli in rats and humans. Specifically, we detected increased activation of the ACC at stimulus offset in both species. In the NAc we observed deactivation following the onset of noxious heat and activation upon cessation of the painful stimulus. We have previously demonstrated change of valence of the fMRI response in the NAc between pain onset and offset in humans (Becerra and Borsook 2008). This finding is confirmed here in a new cohort of experimental subjects and is additionally replicated in rats.

Parallel Activation of the Anterior Cingulate Cortex in Rats and Humans

The exact correspondence of brain structures across species is not always clear (Vogt and Paxinos 2012). The approach to identify similar structures has been based on function and cytoarchitecture (Vogt and Paxinos 2012). Accordingly, the rat cingulate is divided into anterior (ACC), middle (MCC), and posterior or retrosplenial (RPL) cortices. The correspondence for the three divisions of the cingulate in rodents and humans has been established by Vogt and Paxinos. Our results indicate that activity in the cingulate corresponds to the anterior part for both species.

Pain-induced aversiveness is integrated, in part, within the rACC (Tracey and Mantyh 2007). The ACC is also involved in endogenous pain control and descending pain modulation (Petrovic et al. 2002; Wager et al. 2004; Zubieta et al. 2005). Additionally, ACC activity is observed in response to positive stimuli (Wacker et al. 2009), suggesting a potential role in pleasantness of pain relief. Given the complexity of the ACC functions in pain processing, the overall response of the ACC during acute nociceptive stimulus may reflect 1) the initial aversive value of the stimulus, 2) the role of this structure in the behavioral, cognitive, and emotional regulation of pain (Rainville 2002), or 3) the pleasant effects of pain relief. Most imaging studies have not evaluated pain onset and offset separately, and the total response in acute evoked pain studies usually shows increased activation in the ACC to noxious stimuli (Apkarian et al. 2005; Peyron et al. 2000).

Our paradigm evaluated events related to immediate onset and immediate offset of pain. The temporal correlation of the predominant ACC response with the termination of the noxious stimulus supports the role of the ACC in pain relief and/or pain modulation. In our studies any putative activity change at the pain onset was below the threshold, but this does not exclude a possible involvement of the ACC in the initial aversive response. Increased activation during evoked pain may also reflect that the ACC is integrated into a neural network that evaluates pain in the context of potentially threatening or ongoing stimuli (Lorenz and Casey 2005) and interoceptive processing (Taylor et al. 2009). Using analogous noxious stimulation to the dorsal part of a limb, we observed similar changes in the rACC activity in rats and humans at these two times, supporting the notion that brain processing of the affective and motivational aspects of pain is conserved across mammalian species.

The NAc is the primary target of midbrain dopaminergic neurons (Ikemoto 2007) and plays a prominent role in reward-aversive behaviors (Carlezon and Thomas 2009; Deadwyler et al. 2004). Activation of dopaminergic neurotransmission in the NAc in response to primary food and liquid rewards and rewarding drugs has been well documented in both humans and animals (Becerra et al. 2006; Di Chiara et al. 2004; Roitman et al. 2008). In the past few years, research has implicated the region in pain-related behaviors (Altier and Stewart 1999; Gear and Levine 2011; Magnusson and Martin 2002), and it has been shown that dopaminergic inputs from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to NAc can signal rewarding as well as aversive events (McCutcheon et al. 2012; Ungless et al. 2004).

Studies in rodents and humans of the ACC have implicated the structure in a number of processes involved in pain and analgesia. In preclinical studies, pharmacological manipulations such as microinjection of morphine into the ACC result in a naloxone-reversible reduction in pain affect (LaGraize et al. 2006) or enhancement of pain facilitation when the region is stimulated (Calejesan et al. 2000). Studies have contributed to our understanding of the ACC in pain and emotional processing (Johansen et al. 2001). Mechanisms of activation and deactivation in the ACC in response to pain offset may involve activation of specific receptor inhibition or excitation (viz., glutamate and GABA receptors) populations (Ji and Neugebauer 2011). Lesions of the ACC reverse chronic pain in animal models (Qu et al. 2011) and humans (Yen et al. 2009). In human studies functional imaging has shown activation in the structure across most studies of experimental and clinical pain (Apkarian et al. 2005; Peyron et al. 2000). It should be noted that the structure is part of important neural networks (e.g., salience network) (Borsook et al. 2013) that interact with numerous other brain regions, the most prominent of which are the insula and orbitofrontal cortex. The area is also involved in more generalized responses including aversive processing (Ortega et al. 2011), including CPA (Minami 2009), pain relief (Navratilova et al. 2013), and placebo responses (Geuter et al. 2013). Differences in ACC in rats and humans include the presence of von Economo neurons in the human brain and other higher species (apes, whales) but not in rodents (Allman et al. 2011; Butti et al. 2009). Because of these specialized neuronal populations, potential differences in interpretation of awareness may be salient. Complex behaviors such as learning, context, or interoceptive responses to aversive stimuli (Freeman et al. 1996; Seymour et al. 2005) that include discrimination of unpleasantness (Kulkarni et al. 2005) or context inhibition (Talk et al. 2005) might not be present across species.

Parallel Activation of the NAc in Rats and Humans

Regions of the ACC connect with limbic structures, including the NAc (Baleydier and Mauguiere 1980; Powell and Leman 1976; Roberts et al. 2007). In rats, the anatomic location and segregation of the NAc into the core and shell is well defined (Paxinos 2004), but the structure is less well demarcated in humans (Cauda et al. 2011). In humans, the NAc is located at the conjunction between the head of the caudate and the anterior portion of the putamen, laterally to the septum pellucidum (Groenewegen et al. 1999; Heimer et al. 1991). Together with the olfactory tubercle, the NAc forms the ventral striatum. In a prior evaluation of noxious heat activation in the NAc, based on the anatomic and potential functional differences in the core and shell, we suggested that these two subregions might differentially participate in aversion and reward (Aharon et al. 2006). In the present study we observed activation changes in response to the onset and offset of an aversive heat stimulus in the NAc core of the rat. Parallel activation in the human is located within what we may thus assume to be the core on the basis of these functional results. Importantly, we observed analogous valence change in the NAc in response to the aversive (pain onset) and rewarding (pain offset) stimulus in both humans and rats. Thus NAc activity in response to aversion and reward is conserved between species.

Conclusions

In this study we investigated fMRI BOLD responses in the mesocorticolimbic circuit in response to onset and offset of an acute noxious thermal stimuli in parallel in humans and rats. We have shown that the anterior cingulate cortex and the nucleus accumbens respond differently to the onset and offset of pain, suggesting a pivotal role of these brain regions in affective and motivational processing of the hedonic value of pain and pain relief. Changes observed in humans were replicated in rats. Thus the basic brain circuitry for processing pain aversiveness and pleasure of pain relief appear conserved in mammals, indicating that preclinical studies of affective aspect of pain and pain relief are likely translatable to humans and may provide new ways for drug discovery.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the Herlands Fund for Pain Research (to D. Borsook and L. Becerra) and National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke Grant R01 NS066958 (to F. Porreca).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.B. and D.B. conception and design of research; L.B. performed experiments; L.B. analyzed data; L.B., E.N., F.P., and D.B. interpreted results of experiments; L.B. and D.B. prepared figures; L.B., E.N., F.P., and D.B. drafted manuscript; L.B., E.N., F.P., and D.B. edited and revised manuscript; L.B., E.N., F.P., and D.B. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- Aharon I, Becerra L, Chabris CF, Borsook D. Noxious heat induces fMRI activation in two anatomically distinct clusters within the nucleus accumbens. Neurosci Lett 392: 159–164, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albrechet-Souza L, Carvalho MC, Brandao ML. D1-like receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell regulate the expression of contextual fear conditioning and activity of the anterior cingulate cortex in rats. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 16: 1045–1057, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allman JM, Tetreault NA, Hakeem AY, Park S. The von Economo neurons in apes and humans. Am J Hum Biol 23: 5–21, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altier N, Stewart J. The role of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens in analgesia. Life Sci 65: 2269–2287, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apkarian AV, Bushnell MC, Treede RD, Zubieta JK. Human brain mechanisms of pain perception and regulation in health and disease. Eur J Pain 9: 463–484, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baleydier C, Mauguiere F. The duality of the cingulate gyrus in monkey. Neuroanatomical study and functional hypothesis. Brain 103: 525–554, 1980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliki M, Calvo O, Chialvo DR, Apkarian AV. Spared nerve injury rats exhibit thermal hyperalgesia on an automated operant dynamic thermal escape task. Mol Pain 1: 18, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra L, Borsook D. Signal valence in the nucleus accumbens to pain onset and offset. Eur J Pain 12: 866–869, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra L, Chang PC, Bishop J, Borsook D. CNS activation maps in awake rats exposed to thermal stimuli to the dorsum of the hindpaw. Neuroimage 54: 1355–1366, 2011a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra L, Harter K, Gonzalez RG, Borsook D. Functional magnetic resonance imaging measures of the effects of morphine on central nervous system circuitry in opioid-naive healthy volunteers. Anesth Analg 103: 208–216, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra L, Pendse G, Chang PC, Bishop J, Borsook D. Robust reproducible resting state networks in the awake rodent brain. PLoS One 6: e25701, 2011b [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingel U, Lorenz J, Glauche V, Knab R, Glascher J, Weiller C, Buchel C. Somatotopic organization of human somatosensory cortices for pain: a single trial fMRI study. Neuroimage 23: 224–232, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsook D, Edwards R, Elman I, Becerra L, Levine J. Pain and analgesia: the value of salience circuits. Prog Neurobiol 104: 93–105, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butti C, Sherwood CC, Hakeem AY, Allman JM, Hof PR. Total number and volume of von Economo neurons in the cerebral cortex of cetaceans. J Comp Neurol 515: 243–259, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calejesan AA, Kim SJ, Zhuo M. Descending facilitatory modulation of a behavioral nociceptive response by stimulation in the adult rat anterior cingulate cortex. Eur J Pain 4: 83–96, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Thomas MJ. Biological substrates of reward and aversion: a nucleus accumbens activity hypothesis. Neuropharmacology 56, Suppl 1: 122–132, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cauda F, Cavanna AE, D'Agata F, Sacco K, Duca S, Geminiani GC. Functional connectivity and coactivation of the nucleus accumbens: a combined functional connectivity and structure-based meta-analysis. J Cogn Neurosci 23: 2864–2877, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AD. Interoception: the sense of the physiological condition of the body. Curr Opin Neurobiol 13: 500–505, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deadwyler SA, Hayashizaki S, Cheer J, Hampson RE. Reward, memory and substance abuse: functional neuronal circuits in the nucleus accumbens. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 27: 703–711, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Chiara G, Bassareo V, Fenu S, De Luca MA, Spina L, Cadoni C, Acquas E, Carboni E, Valentini V, Lecca D. Dopamine and drug addiction: the nucleus accumbens shell connection. Neuropharmacology 47, Suppl 1: 227–241, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman JH, Jr, Cuppernell C, Flannery K, Gabriel M. Context-specific multi-site cingulate cortical, limbic thalamic, and hippocampal neuronal activity during concurrent discriminative approach and avoidance training in rabbits. J Neurosci 16: 1538–1549, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gear RW, Levine JD. Nucleus accumbens facilitates nociception. Exp Neurol 229: 502–506, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geha PY, Baliki MN, Harden RN, Bauer WR, Parrish TB, Apkarian AV. The brain in chronic CRPS pain: abnormal gray-white matter interactions in emotional and autonomic regions. Neuron 60: 570–581, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geuter S, Eippert F, Hindi Attar C, Buchel C. Cortical and subcortical responses to high and low effective placebo treatments. Neuroimage 67: 227–236, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill JD, Coghill RC. Transient analgesia evoked by noxious stimulus offset. J Neurophysiol 87: 2205–2208, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewegen HJ, Wright CI, Beijer AV, Voorn P. Convergence and segregation of ventral striatal inputs and outputs. Ann NY Acad Sci 877: 49–63, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heimer L, Zahm DS, Churchill L, Kalivas PW, Wohltmann C. Specificity in the projection patterns of accumbal core and shell in the rat. Neuroscience 41: 89–125, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikemoto S. Dopamine reward circuitry: two projection systems from the ventral midbrain to the nucleus accumbens-olfactory tubercle complex. Brain Res Rev 56: 27–78, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage 17: 825–841, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji G, Neugebauer V. Pain-related deactivation of medial prefrontal cortical neurons involves mGluR1 and GABAA receptors. J Neurophysiol 106: 2642–2652, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johansen JP, Fields HL, Manning BH. The affective component of pain in rodents: direct evidence for a contribution of the anterior cingulate cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 8077–8082, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni B, Bentley DE, Elliott R, Youell P, Watson A, Derbyshire SW, Frackowiak RS, Friston KJ, Jones AK. Attention to pain localization and unpleasantness discriminates the functions of the medial and lateral pain systems. Eur J Neurosci 21: 3133–3142, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaGraize SC, Borzan J, Peng YB, Fuchs PN. Selective regulation of pain affect following activation of the opioid anterior cingulate cortex system. Exp Neurol 197: 22–30, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leknes S, Lee M, Berna C, Andersson J, Tracey I. Relief as a reward: hedonic and neural responses to safety from pain. PLoS One 6: e17870, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz J, Casey KL. Imaging of acute versus pathological pain in humans. Eur J Pain 9: 163–165, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnusson JE, Martin RV. Additional evidence for the involvement of the basal ganglia in formalin-induced nociception: the role of the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res 942: 128–132, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon JE, Ebner SR, Loriaux AL, Roitman MF. Encoding of aversion by dopamine and the nucleus accumbens. Front Neurosci 6: 137, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami M. Neuronal mechanisms for pain-induced aversion behavioral studies using a conditioned place aversion test. Int Rev Neurobiol 85: 135–144, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray EA, Wise SP, Rhodes SEV. What Can Different Brains Do with Reward? In: Neurobiology of Sensation and Reward, edited by Gottfried JA. Boca Raton, FL: CRC, 2011 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navratilova E, Xie JY, King T, Porreca F. Evaluation of reward from pain relief. Ann NY Acad Sci 1282: 1–11, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navratilova E, Xie JY, Okun A, Qu C, Eyde N, Ci S, Ossipov MH, King T, Fields HL, Porreca F. Pain relief produces negative reinforcement through activation of mesolimbic reward-valuation circuitry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109: 20709–20713, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oluigbo CO, Salma A, Rezai AR. Targeting the affective and cognitive aspects of chronic neuropathic pain using basal forebrain neuromodulation: rationale, review and proposal. J Clin Neurosci 19: 1216–1221, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega LA, Uhelski M, Fuchs PN, Papini MR. Impairment of recovery from incentive downshift after lesions of the anterior cingulate cortex: emotional or cognitive deficits? Behav Neurosci 125: 988–995, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson JA, Willoughby PJ, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Disconnection of the anterior cingulate cortex and nucleus accumbens core impairs Pavlovian approach behavior: further evidence for limbic cortical-ventral striatopallidal systems. Behav Neurosci 114: 42–63, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G. The Rat Nervous System. New York: Elsevier Academic, 2004, p. 1328 [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. New York: Elsevier, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendse G, Borsook D, Becerra L. Enhanced false discovery rate using Gaussian mixture models for thresholding fMRI statistical maps. Neuroimage 47: 231–261, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic P, Kalso E, Petersson KM, Ingvar M. Placebo and opioid analgesia– imaging a shared neuronal network. Science 295: 1737–1740, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron R, Garcia-Larrea L, Gregoire MC, Costes N, Convers P, Lavenne F, Mauguiere F, Michel D, Laurent B. Haemodynamic brain responses to acute pain in humans: sensory and attentional networks. Brain 122: 1765–1780, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peyron R, Laurent B, Garcia-Larrea L. Functional imaging of brain responses to pain. A review and meta-analysis (2000). Clin Neurophysiol 30: 263–288, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powell EW, Leman RB. Connections of the nucleus accumbens. Brain Res 105: 389–403, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu C, King T, Okun A, Lai J, Fields HL, Porreca F. Lesion of the rostral anterior cingulate cortex eliminates the aversiveness of spontaneous neuropathic pain following partial or complete axotomy. Pain 152: 1641–1648, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainville P. Brain mechanisms of pain affect and pain modulation. Curr Opin Neurobiol 12: 195–204, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainville P, Duncan GH, Price DD, Carrier B, Bushnell MC. Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science 277: 968–971, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts AC, Tomic DL, Parkinson CH, Roeling TA, Cutter DJ, Robbins TW, Everitt BJ. Forebrain connectivity of the prefrontal cortex in the marmoset monkey (Callithrix jacchus): an anterograde and retrograde tract-tracing study. J Comp Neurol 502: 86–112, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roitman MF, Wheeler RA, Wightman RM, Carelli RM. Real-time chemical responses in the nucleus accumbens differentiate rewarding and aversive stimuli. Nat Neurosci 11: 1376–1377, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott DJ, Heitzeg MM, Koeppe RA, Stohler CS, Zubieta JK. Variations in the human pain stress experience mediated by ventral and dorsal basal ganglia dopamine activity. J Neurosci 26: 10789–10795, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seymour B, O'Doherty JP, Koltzenburg M, Wiech K, Frackowiak R, Friston K, Dolan R. Opponent appetitive-aversive neural processes underlie predictive learning of pain relief. Nat Neurosci 8: 1234–1240, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talk A, Stoll E, Gabriel M. Cingulate cortical coding of context-dependent latent inhibition. Behav Neurosci 119: 1524–1532, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor KS, Seminowicz DA, Davis KD. Two systems of resting state connectivity between the insula and cingulate cortex. Hum Brain Mapp 30: 2731–2745, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson SJ, Bushnell MC. Rodent functional and anatomical imaging of pain. Neurosci Lett 520: 131–139, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracey I, Mantyh PW. The cerebral signature for pain perception and its modulation. Neuron 55: 377–391, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ungless MA, Magill PJ, Bolam JP. Uniform inhibition of dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area by aversive stimuli. Science 303: 2040–2042, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay J, Pendse G, Anderson J, Schwarz AJ, Baumgartner R, Coimbra A, Bishop J, Knudsen J, George E, Grachev I, Iyengar S, Bleakman D, Hargreaves R, Borsook D, Becerra L. Improved characterization of BOLD responses for evoked sensory stimuli. Neuroimage 49: 2275–2286, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt BA, Paxinos G. Cytoarchitecture of mouse and rat cingulate cortex with human homologies. Brain Struct Funct. In press [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wacker J, Dillon DG, Pizzagalli DA. The role of the nucleus accumbens and rostral anterior cingulate cortex in anhedonia: integration of resting EEG, fMRI, and volumetric techniques. Neuroimage 46: 327–337, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wager TD, Rilling JK, Smith EE, Sokolik A, Casey KL, Davidson RJ, Kosslyn SM, Rose RM, Cohen JD. Placebo-induced changes in FMRI in the anticipation and experience of pain. Science 303: 1162–1167, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yen CP, Kuan CY, Sheehan J, Kung SS, Wang CC, Liu CK, Kwan AL. Impact of bilateral anterior cingulotomy on neurocognitive function in patients with intractable pain. J Clin Neurosci 16: 214–219, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubieta JK, Bueller JA, Jackson LR, Scott DJ, Xu Y, Koeppe RA, Nichols TE, Stohler CS. Placebo effects mediated by endogenous opioid activity on mu-opioid receptors. J Neurosci 25: 7754–7762, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]