Abstract

Background

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) serves as a predominant Cl− transport conduit in airway epithelium and is inhibited by cigarette smoke in vitro and in vivo. Activation of secondary Cl− transport pathways through calcium-activated Cl− channels (CaCC) has been postulated as a mechanism to bypass defects in CFTR-mediated transport. Because it is not known whether CaCC’s are also inhibited by tobacco exposure, the current study was designed to investigate the effect of cigarette smoke condensate (CSC) on CaCC transport.

Study Design

In vitro study

Methods

Well-characterized primary murine nasal septal epithelial (MNSE) and human sinonasal epithelial (HSNE) cultures were exposed to CSC in Ussing chambers. We monitored CaCC short-circuit current through stimulation of P2Y purinergic receptors with UTP or ATP and selective inhibition of the CFTR dependent secretory pathway. Characterization of CaCC current was also accomplished in primary airway cells derived from transgenic CFTR−/− (knockout) murine models.

Results

Change in CaCC-mediated current (ΔISC - representing transepithelial Ca-mediated Cl− secretion in µA/cm2) was significantly decreased in CSC-exposed wild type MNSE when compared to controls{(32.8 +/− 4.6 vs. 47.5 +/− 2.3; respectively) p < 0.02}. A similar effect was demonstrated in CFTR−/− MNSE cultures(33.4 +/− 2.8 vs. 38.6 +/− 2.0; p<0.05}. HSNE cultures also had a significant reduction in ISC (16.1 +/− 0.6 vs. 22.7 +/− 0; p=0.008).

Conclusions

CSC affects multiple pathways fundamental to airway ion transport, including both cAMP and calcium activated Cl− transport. Inhibition of Cl− transport may contribute to common diseases of the airways, such as chronic rhinosinusitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Keywords: Transepithelial Ion Transport, cigarette smoke condensate, Calcium Activated Chloride Channel, CFTR, Chronic Sinusitis, Chloride Secretion, Murine Nasal Culture, Mucociliary Clearance

Introduction

Sinonasal respiratory epithelium is responsible for the clearance of inhaled pathogens from the nose and paranasal sinuses. The airway surface liquid (ASL) is one component of mucociliary clearance (MCC). ASL is a complex mixture of mucus and periciliary fluid, the composition of which is determined by vectorial transport of ions, such as Cl−1. Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) channels contribute the predominant Cl− transport conduit within respiratory epithelial cells2. In the inherited disease cystic fibrosis (CF), there is a mutation in the CFTR protein resulting in impaired exocrine function. In the nose and paranasal sinuses, this effect manifests through dehydration of ASL, and results in chronic stasis of inspissated mucus, bacterial infection, and widespread chronic sinus disease refractory to medical management3.

Cigarette smoke is a highly toxic substance that greatly affects MCC. Various chemicals in cigarette smoke are known to be toxic in respiratory epithelium4–6. Cigarette smokers have exhibit a higher rate of recurrent sinusitis and chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) when compared to non-smokers7. The effects of cigarette smoke are thought to be secondary to impairment of ciliary function and dehydration of the ASL8–10. Patients with chronic bronchitis induced by smoking have histopathological similarities to patients with CF. These similarities include mucus hypersecretion, goblet cell hyperplasia, neutrophilic infiltration of the airway lumen, and bacterial pathogens in the lower airways11. Cigarette smoke extract (CSE) has been shown to decrease epithelial Cl− secretion in canine trachea and human bronchial epithelial cells12,13. However, CSE lacks the water insoluble components of cigarette smoke. In a prior study by our group, cigarette smoke condensate (CSC), which contains the particulate and water insoluble components of tobacco combustion, was shown to substantially decrease transepithelial transport of Cl− and ciliary beat frequency14.

Activation of secondary Cl− transport pathways through calcium activated chloride channels (CaCC) has been postulated as a potential mechanism to bypass defects in CFTR-mediated Cl− transport15,16. Although CaCC activity is known to contribute to ASL, MCC, and pathogenesis in diseases, such as CF, no studies to date have evaluated effects of CSC on CaCC. The present study was designed to investigate the effects of CSC on CaCC function in murine nasal septal epithelia (MNSE), human sinonasal epithelia (HSNE), and transgenic CFTR−/− MNSE knockout cultures. The findings indicate that CSC inhibits transepithelial Cl− secretion mediated by CaCC’s, and have important implications regarding both mechanism and recently emerging experimental therapeutics for diseases, such as CF, CRS and COPD.

Materials and Methods

Institutional review board and institutional animal care and use committee approval were obtained prior to the initiation of the study.

Tissue Culture

The culture technique for propagation of MNSE and HSNE at an air-liquid interface has been described in our prior studies17–21. Human sinus epithelium was derived from tissue removed during skull base surgery from individuals without inflammatory disease. Briefly, tissue was harvested and grown on Costar 6.5-mm-diameter permeable filter supports (Corning Life Sciences, Lowell, MA) submerged in culture medium. The media was removed from the surface of the monolayers on day 4 after reaching confluence and the cells fed via the basal chamber. MNSE cultures were genetically identical and derived from the C57 strain and from transgenic CFTR−/− knockout mice. Differentiation and ciliogenesis occurred in all cultures within 10 days to 14 days.

A total of 80 filters were used for completion of these studies. Dose-response relationships and establishment of protocols for the most informative order and application of pharmacologic agents were performed prior to initiation of the study (data not shown). MNSE wild type (wt) and CFTR−/− knockout filters were derived from otherwise genetically identical (congenic) mice. Ussing Chamber analysis was performed only when cell monolayers were fully differentiated with widespread ciliogenesis and transepithelial resistances (RT) >500 Ω cm2. There was no significant difference between the RT and ISC of control and CSC-exposed filters when the two groups were compared before the addition of CSC, DMSO, or pharmacologic agents.

Electrophysiology

Solutions and Chemicals

The bath solution contained (mM): 120 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 3.3 KH2PO4, 0.8 K2PO4, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 Glucose. The pH of this solution is 7.3–7.4 when gassed with a mixture of 95% O2-5% CO2 at 37°C. Chemicals were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Each solution was produced as 1,000× stock and used at 1x in the Ussing Chamber. All experiments were performed with low Cl− (6mM) in the mucosal bath. Pharmacologic preparations were as follows: amiloride (100 µM); INH-172 (10 µM); CSC (200 µg/ml); adenosine deaminase (ADA, 5µg/ml); ATP (200 µM); Niflumic Acid (100 µM), Forskolin (20 µM); UTP (150 µM). Amiloride blocks Na+ channels, ensuring that changes observed in short-circuit current (Δ ISC) from various manipulations are attributable to effects on Cl− transport. ATP activates both P2Y receptors, which activate CaCC secretion, and A2B receptors via the breakdown product adenosine, which stimulates CFTR Cl− secretion through cAMP-mediated mechanisms22. To ensure that an observed ISC was due to CaCC, ADA was added to degrade the adenosine byproduct of ATP metabolism. INH-172 is a selective blocker of CFTR-mediated pathways and also inhibits CFTR stimulation, and was used in confirmatory assays to indicate selective ISC activity due to CaCC. UTP activates CaCC ISC via P2Y receptors and was utilized for monitoring CaCC Cl− secretion in wild type and CFTR−/− MNSE cultures. Niflumic acid is a commonly used inhibitor of CaCC ISC, although it also blocks other ion transport pathways, such as CFTR, non-selective cation channels and voltage-gated potassium channels23–25. Forskolin is an activator of cAMP and the CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion pathway and was administered following activation of CaCCs in transgenic CFTR knockout MNSE cultures to confirm absence of CFTR.

CSC was purchased from Murty Pharmaceuticals (Lexington, KY) and is comprised of the particulate matter of cigarette smoke, including thousands of toxic chemicals (e.g. nicotine, nitrosamines, heavy metals, cadmium, phenol, anthracyclic hydrocarbons, and chemical carcinogens) dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). In order to ensure changes in short-circuit current measurements were not secondary to DMSO, all control experiments were performed with the corresponding amount of this solvent. The optimum concentration of CSC for Ussing chamber analysis was determined in a previous study to be 200 µg/ml14.

Short circuit (ISC) measurements

Transwell inserts (Costar, Corning Life Sciences) were mounted in a modified, vertical Ussing Chamber to investigate pharmacologic manipulation of ion transport. Monolayers were continuously short-circuited after fluid resistance compensation using automatic VCC 600 voltage clamps (Physiologic Instruments, San Diego, CA). Transwell filters were mounted in bath solution warmed to 37°C, and the solution continuously gas-lifted with a 95%O2/5%CO2 mixture. The ISC was monitored at 1 measurement per second. By convention, a positive deflection in ISC was defined as the net movement of anion in the serosal to mucosal direction.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using two-tailed paired t-test, unpaired t-test, and analysis of variance, as appropriate.

Results

Initial stimulation with CaCC-stimulated currents (ΔISC) in MNSE cultures were significantly decreased when exposed to CSC (32.83 ± 4.6 µA/cm2) in comparison to DMSO controls (47.53 ± 2.25 µA/cm2; p = 0.02). (Figure 1&2) To isolate apical CaCC-mediated current, CFTR−/− knockout mice were utilized. CFTR−/− knockout cultures also had significant inhibition of ΔISC when compared to controls (33.4 ± 2.78 µA/cm2 vs.38.56 ± 1.96 µA/cm2, respectively; p = 0.03) confirming inhibition of CaCC Cl− current. (Figure 1&3) The absence of response following the combination of forskolin and purinergic (P2Y) stimulation confirmed a lack of CFTR-mediated pathways in the transgenic CFTR knockout cultures. In trials with HNSE cultures, there was also a significant reduction in ΔISC with CSC exposure (CSC, 16.06 ± 0.6 µA/cm2 vs. control, 22.7 ± 0 µA/cm2; p = 0.008). (Figure 1)

Figure 1.

The change in CaCC-stimulated current (ΔISC) in wild type MNSE, CFTR knockout MNSE, and HSNE cultures was significantly decreased when exposed to CSC in comparison to DMSO controls.

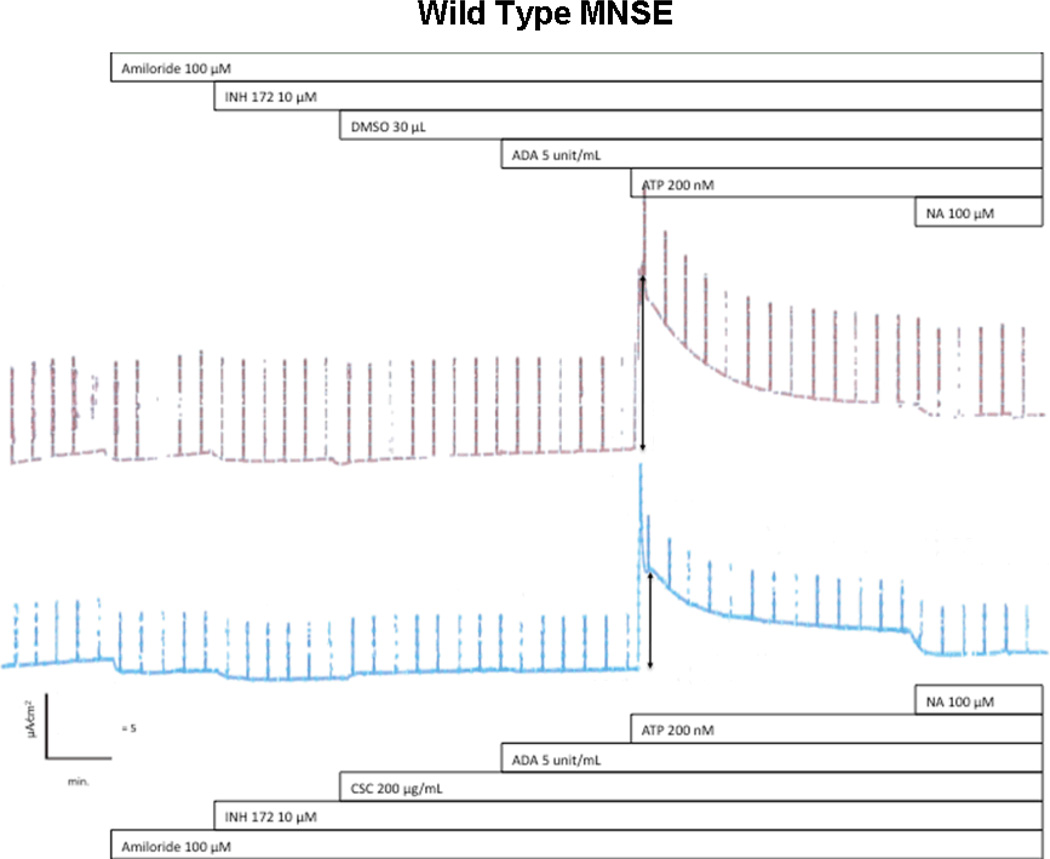

Figure 2.

Representative ISC tracing of wild type MNSE cultures. Wild type MNSE cells grown on transwell permeable supports were mounted in modified Ussing chambers under short-circuit conditions and sequentially exposed to amiloride, INH-172, CSC or DMSO control, ADA, ATP, and niflumic acid. Note no changes in Cl− dependent ISC (after amiloride) until the application of ATP. Either DMSO control (upper tracing) or 200 µg/ml of CSC was added to the apical surface at the start of the experiment. Decreased ATP-stimulated CaCC ISC was observed in the upper tracing (arrows). Niflumic acid (NA) inhibition was considered unreliable due to non-specificity and variable results.

Figure 3.

Representative ISC tracing of CFTR−/− MNSE cultures. Cultures were sequentially exposed to amiloride, CSC or DMSO control, UTP, niflumic acid, and forskolin. Decreased ATP-stimulated CaCC ISC was observed in the upper tracing (arrows). The addition of forskolin confirms lack of CFTR in these transgenic mice.

Discussion

The studies presented here examined the effects of CSC on CaCC-mediated Cl− secretion. Prior reports have demonstrated tobacco smoke byproduct inhibition of CFTR-mediated Cl− secretion in models of lower airway cell epithelium. In a recent study by our group, inhibition of CFTR-mediated Cl− transport by CSC was demonstrated in MNSE and HSNE cultures14. While much is known regarding CFTR structure and function, the Cl− channel TMEM16A was only recently identified as the major candidate channel responsive to calcium-dependent activation26. Because secondary Cl− transport pathways through CaCC’s represent a unique target for therapy of CF and other diseases of MCC, TMEM16A could represent a potential therapeutic avenue for treatment in the setting of cigarette smoke related mucociliary dysfunction15,16. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the effects of CSC specifically on CaCC-mediated transepithelial Cl− secretion.

In the present experiments, CaCC-mediated Cl− transport was inhibited in both murine and human culture models of upper airway epithelium. Through pharmacologic manipulation of CFTR-mediated current and Na+ channel blockade, we focused on apical CaCC ΔISC and examined the effects of CSC in these in vitro culture models. Transgenic CFTR−/− MNSE cultures provided an excellent validation of CFTR-independence of the pathways investigated here. There is some evidence to suggest that CaCC’s play a more prominent role in murine (versus human) airway epithelium, based on earlier findings that CF transgenic mice do not develop significant sinopulmonary disease27. Thus, confirmation of these effects in a human culture model was required. Notably, studies of HSNE cultures also exhibited significantly decreased CaCC-mediated ISC when exposed to CSC, corroborating this effect across species.

The mechanisms by which CSC inhibits transepithelial CaCC-mediated Cl− secretion are currently unknown. Our previous studies have demonstrated inhibition of CFTR-mediated Cl− transport, which could be secondary to a decrease in cAMP-mediated cell signaling in response to forskolin14. Others have shown decreased expression of CFTR mRNA, protein, and function in response to cigarette smoke extract in vitro12. As CaCC’s have a distinct mechanism of action through intracellular Ca2+ second messenger signaling, this pathway may represent a distinct target of CSC and will be a focus of future investigations. Alternatively, a general stimulation of the cellular Cl− secretory gradient (e.g. via effects on basolateral transport mechanisms) may also contribute to the findings shown here. The present experiments therefore provide a foundation for molecular analysis (RT-PCR, protein expression) of CSC effects on other epithelial transport mechanisms in the future28.

Conclusion

The present investigation expanded on a prior study by our group demonstrating inhibition of transepithelial Cl− current by CSC. We found that CSC specifically confers inhibition of CaCC-mediated Cl− current in MNSE cultures, confirmed our findings in transgenic CFTR−/− airway epithelial monolayers, and also validated the role of CaCC’s in a human culture model of sinonasal epithelium. The findings from this study lend support to the hypothesis that sinonasal mucus is inefficiently cleared in response to cigarette smoke secondary to a decrease in Cl− secretion, which causes a reduction in the periciliary fluid layer volume. The results point to a more profound effect of cigarette smoke on MCC than previously appreciated. The Cl− secretory pathways inhibitied by CSC include CFTR, CaCC, and possibly other ion transport mechanisms in the airways. Pharmacologic stimulation of Cl− transport represents a potential therapeutic target for individuals with CRS and other diseases of mucociliary dysfunction that are contributed by frequent tobacco smoke exposures.

Acknowledgments

Research Support: This research was funded by the American Rhinologic Society New Investigator Award (2009) and Flight Attendant’s Medical Research Institute Young Clinical Scientist Award (072218) to B.A.W. and a NIH/NIDDK 5P30DK072482-03 to E.J.S.

Footnotes

Presented at the Triologic Society’s Southern Section meeting, Orlando, Fla., February 4–7, 2010

Conflict of Interest: Dr. Sorscher serves as a consultant for a Birmingham start up company (PNP Therapeutics, Inc) but is not employed by the company and draws no salary from the company. His consulting includes a role as Director/Officer. He acts as a consultant with the approval of UAB and the UAB CIRB. He is compensated for consulting with stock. This company has no relationship to the current manuscript. Dr. Sorscher and Dr. Woodworth are inventors on a patent submitted regarding the possible activity of chloride secretagogues for therapy of sinus disease (Provisional Patent Application Under 35 U.S.C. §111(b) and 37 C.F.R. § 1.53(c) in the United States Patent and Trademark Office). Dr. Woodworth is a consultant for Gyrus ENT, ArthroCare ENT, and is on the GlaxcoSmithKline speaker’s bureau.

References

- 1.Trout L, King M, Feng W, Inglis SK, Ballard ST. Inhibition of airway liquid secretion and its effect on the physical properties of airway mucus. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:L258–L263. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1998.274.2.L258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anderson MP, Gregory RJ, Thompson S, et al. Demonstration that CFTR is a chloride channel by alteration of its anion selectivity. Science. 1991;253:202–205. doi: 10.1126/science.1712984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moller W, Haussinger K, Ziegler-Heitbrock L, Heyder J. Mucociliary and long-term particle clearance in airways of patients with immotile cilia. Respir Res. 2006;7:10. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agius AM, Smallman LA, Pahor AL. Age, smoking and nasal ciliary beat frequency. Clin Otolaryngol. 1998;23:227–230. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2273.1998.00141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalhamn T, Rylander R. Ciliotoxicity of cigar and cigarette smoke. Arch Environ Health. 1970;20:252–253. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1970.10665581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dalhamn T, Rylander R, Spears AW. Differences in ciliotoxicity of cigarette smoke. Comparison of two exposure methods. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1967;96:1078–1079. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1967.96.5.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramadan HH, Hinerman RA. Smoke exposure and outcome of endoscopic sinus surgery in children. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;127:546–548. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2002.129816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moodie FM, Marwick JA, Anderson CS, et al. Oxidative stress and cigarette smoke alter chromatin remodeling but differentially regulate NF-kappaB activation and proinflammatory cytokine release in alveolar epithelial cells. Faseb J. 2004;18:1897–1899. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1506fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Verra F, Escudier E, Lebargy F, Bernaudin JF, De Cremoux H, Bignon J. Ciliary abnormalities in bronchial epithelium of smokers, ex-smokers, and nonsmokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:630–634. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/151.3_Pt_1.630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wanner A, Salathe M, O'Riordan TG. Mucociliary clearance in the airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:1868–1902. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.6.8970383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sethi S. Bacterial infection and the pathogenesis of COPD. Chest. 2000;117:286S–291S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_1.286s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kreindler JL, Jackson AD, Kemp PA, Bridges RJ, Danahay H. Inhibition of chloride secretion in human bronchial epithelial cells by cigarette smoke extract. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;288:L894–L902. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00376.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Welsh MJ. Cigarette smoke inhibition of ion transport in canine tracheal epithelium. J Clin Invest. 1983;71:1614–1623. doi: 10.1172/JCI110917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cohen NA, Zhang S, Sharp DB, et al. Cigarette smoke condensate inhibits transepithelial chloride transport and ciliary beat frequency. Laryngoscope. 2009 doi: 10.1002/lary.20223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zsembery A, Hargitai D. Role of Ca(2+)-activated ion transport in the treatment of cystic fibrosis. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2008;158:562–564. doi: 10.1007/s10354-008-0596-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zsembery A, Strazzabosco M, Graf J. Ca2+-activated Cl− channels can substitute for CFTR in stimulation of pancreatic duct bicarbonate secretion. FASEB J. 2000;14:2345–2356. doi: 10.1096/fj.99-0509com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodworth BA, Antunes MB, Bhargave G, et al. Murine nasal septa for respiratory epithelial air-liquid interface cultures. Biotechniques. 2007;43:195–204. doi: 10.2144/000112531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhargave G, Woodworth BA, Xiong G, Wolfe SG, Antunes MB, Cohen NA. Transient receptor potential vanilloid type 4 channel expression in chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:7–12. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Woodworth BA, Tamashiro E, Bhargave G, Cohen NA, Palmer JN. An in vitro model of Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms on viable airway epithelial cell monolayers. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:234–238. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woodworth BA, Antunes MB, Bhargave G, Palmer JN, Cohen NA. Murine tracheal and nasal septal epithelium for air-liquid interface cultures: A comparative study. Am J Rhinol. 2007;21(5):533–537. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2007.21.3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang S, Fortenberry JA, Cohen NA, Sorscher EJ, Woodworth BA. Comparison of vectorial ion transport in murine airway and human sinonasal air-liquid interface cultures, models for cystic fibrosis and other airway diseases. Am J Rhinol. 2009;2 doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kukulski F, Levesque SA, Lavoie EG, et al. Comparative hydrolysis of P2 receptor agonists by NTPDases 1, 2, 3 and 8. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-6217-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee YT, Wang Q. Inhibition of hKv2.1, a major human neuronal voltage-gated K+ channel, by meclofenamic acid. Eur J Pharmacol. 1999;378:349–356. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(99)00485-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCarty NA, McDonough S, Cohen BN, Riordan JR, Davidson N, Lester HA. Voltage-dependent block of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator Cl− channel by two closely related arylaminobenzoates. J Gen Physiol. 1993;102:1–23. doi: 10.1085/jgp.102.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gogelein H, Dahlem D, Englert HC, Lang HJ. Flufenamic acid, mefenamic acid and niflumic acid inhibit single nonselective cation channels in the rat exocrine pancreas. FEBS Lett. 1990;268:79–82. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80977-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caputo A, Caci E, Ferrera L, et al. TMEM16A, a membrane protein associated with calcium-dependent chloride channel activity. Science. 2008;322:590–594. doi: 10.1126/science.1163518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rock JR, O'Neal WK, Gabriel SE, et al. Transmembrane protein 16A (TMEM16A) is a Ca2+-regulated Cl− secretory channel in mouse airways. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:14875–14880. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C109.000869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flagella M, Clarke LL, Miller ML, et al. Mice lacking the basolateral Na-K-2Cl cotransporter have impaired epithelial chloride secretion and are profoundly deaf. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26946–26955. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.38.26946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]