Abstract

Argonaute 1 (Ago1) is a member of the Argonaute/PIWI protein family involved in small RNA-mediated gene regulation. In Drosophila, Ago1 plays a specific role in microRNA (miRNA) biogenesis and function. Previous studies have demonstrated that Ago1 regulates the fate of germline stem cells. However, the function of Ago1 in other aspects of oogenesis is still elusive. Here we report the function of Ago1 in developing egg chambers. We find that Ago1 protein is enriched in the oocytes and also highly expressed in the cytoplasm of follicle cells. Clonal analysis of multiple ago1 mutant alleles shows that many mutant egg chambers contain only 8 nurse cells without an oocyte which is phenocopied in dicer-1, pasha and drosha mutants. Our results suggest that Ago1 and its miRNA biogenesis partners play a role in oocyte determination and germline cell division in Drosophila.

Introduction

Drosophila oogenesis is an excellent system for studying gene regulation during development. Each adult ovary contains about 14–20 ovarioles, each of which contains strings of developing egg chambers (Spradling, 1993). Germline cells are formed in the germarium, at the most anterior part of the ovariole, which contains on 2–3 germline stem cells (GSC). Each GSC divides into two daughter cells along the anterior-posterior axis. The anterior daughter cell remains as a stem cell, contacting cap cells in the niche, while the posterior daughter cell differentiates into a cystoblast (Xie and Spradling, 1998). Oocyte determination starts in the germarium when the cystoblast divides four times to produce 16 cyst cells. One cyst cell will become the oocyte, while the other 15 cyst cells become the nurse cells (Spradling, 1993).

The Drosophila Argonaute (Ago) family has five members: Ago1, Ago2, Ago3, Piwi and Aubergine (Aub). The Piwi subclade of Argonaute proteins, Piwi, Ago3 and Aub, are devoted to the production and function of piRNAs, a class of small RNAs involved in defending the genome from transposable elements (Girard et al., 2006), and are largely confined to the germline and surrounding somatic tissues (Brennecke et al, 2007). The two remaining members of the Argonaute family, Ago1 and Ago2, are predominantly involved in gene regulation mediated by miRNAs and siRNAs, respectively, although there is some degree of overlap bewteen these two pathways (Okamura et al, 2009, Czech et al, 2009). Ago1, which is conserved from fruit fly to human, binds to mature microRNAs (miRNAs) to form the RNA-induced silencing complex (RISC). Ago2 forms the RISC by binding to siRNAs instead (Okamura et al., 2004).

The predicted molecular weight of the Ago1 protein is approximately 106 kDa comprising 950 amino acids (Kataoka et al., 2001). There are 3 domains in the Ago1 protein: the PAZ domain of 110 amino acids, the well conserved PIWI domain consisting of 300 amino acids and the newly characterized MID domain (Djuranovic et al., 2010). The 3’ and 5’ ends of the miRNA bind to the PAZ domain and the MID domain respectively. The PIWI box contains the catalytic centre for cleavage. Yang et al., (2007) showed that Ago1 is required for Drosophila germline stem cell (GSC) maintenance. Overexpression of Ago1 leads to GSC over-proliferation while ago1 mutants lead to GSC loss.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs are ~22 nucleotide endogenous short RNAs that have a role in the regulation of gene expression in animals and plants by targeting complimentary mRNAs for degradation or translational repression (Ambros, 2004). RNA polymerase II transcribes the primary transcript (pri-miRNA) that contains hairpin loop domains, a 7-methyl-guanosine cap, and a poly-A tail (Bartel, 2009). The pri-miRNA is cut by the microprocessor complex, comprising the RNAse III enzyme Drosha and its RNA binding domain-containing partner Pasha (Denli et al., 2004; Gregory et al., 2004; Han et al., 2004), to become a 60–70 nucleotide-long precursor miRNA (pre-miRNA), which is then exported to the cytoplasm by Exportin5, a Ran-GTP-dependent cytoplasmic cargo transporter (Bohnsack et al., 2004; Lund et al., 2004; Yi et al., 2003). In the cytoplasm, Dicer-1, together with its partner, Loquacious, cleaves the hairpin loop of the pre-miRNA to form a miRNA-miRNA* duplex (Forstemann et al., 2005; Saito et al., 2005). This duplex unwinds and one strand is selected as the mature miRNA and preferentially loaded into Ago1 to form the RNA induced silencing complex (RISC) (Forstemann et al., 2007; Tomari et al., 2007). The strand that is not loaded into Ago1, referred to as the miRNA* strand, is presumably degraded most of the time, but in some cases is loaded into the Ago2-containing RISC where it can function as an siRNA (Czech et al., 2009; Okamura et al., 2009). Interactions between the miRNA-RISC (miRISC) and mRNA targets involve binding between the “seed” region of the miRNA (typically nucleotides 2–8) and the complementary target sequence on the mRNA (Bartel, 2009; Lai, 2002). This short recognition sequence means that a single miRNA can target numerous mRNAs and often operate in highly complex regulatory networks in combination with other miRNAs as most UTRs contain potential target sites for several miRNAs (Kim and Nam, 2006). Recent advances from genetic and genomic studies have indicated that miRNAs play important roles in many aspects of cell and animal development such as cell proliferation, differentiation, morphogenesis, and apoptosis (Carrington and Ambros, 2003; Flynt and Lai, 2008; Kim et al., 2006; Nakahara et al., 2005).

Here we investigate the role of Ago1 during oogenesis. We find that Ago1 protein is enriched in the oocyte. Clonal analysis of multiple ago1 mutant alleles shows that Ago1 is required for proper oocyte formation and germline cell division. We also observe that the germline cell division phenotype manifested in the germarium and the oocyte is determined but failed to be maintained in meiosis stage. Furthermore, mutations in dicer-1, pasha and drosha result in a high incidence of 8-cell cysts, similar to the phenotype observed in ago1 mutants. Together, our data provide evidence that Ago1 and its miRNA biogenesis pathway partners, Dicer-1, Pasha and Drosha, and by inference microRNAs, are have important roles during Drosophila oogenesis.

Materials and Methods

Fly Stocks

All stocks were raised at 25°C on standard cornmeal media. y w flies were used as a controls in all our experiments, if not stated otherwise. The ago1 hypomorphic mutant, ago1k08121 (Kataoka et al, 2001) and null mutants, ago114 and ago1EMS (Yang et al, 2007) have been described previously. Ago1::GFP protein trap flies were obtained from the Carnegie Protein Trap Collection (Buszczak et al., 2007). The dicer-1LL06357 (Berdnik et al., 2008), dicer-1Q1147X (Lee et al., 2004), pashaLL03360 (Berdnik et al., 2008), pashaKO (Martin et al., 2009) and drosha21K11 (Smibert et al., 2011) are mutant alleles that have been described previously. The inducible GAL4 driver stock hsFLP, UAS-GFPnls; tub-FRT-GAL80-FRT-GAL4 was used to generate mosaic over-expression (Zecca and Struhl, 2002). UAS-Ago1 T2.1 was used for the overexpression experiment (Dietzl et al., 2007).

Clonal Analysis

To generate Ago1 mitotic clones, hsFLP; FRTG13 Ubi-GFP/CyO flies were crossed to y w; FRTG13 ago1k08121/CyO, y w; FRTG13 ago114/CyO or y w; FRTG13 ago1EMS/CyO flies. y w; FRTG13 was used as positive control. To generate Pasha or Dicer-1 clones, hsFLP; FRT82B Ubi-GFP/TM3 Ser were crossed with y w; FRT82B dicer-1LL06357/TM3Ser, y w; FRT82B dicer-1Q1147X/TM3 Ser, w; FRT82B dicer-121B2/TM6B, w; FRT82B dicer-130D2/TM6B, w; FRT82B dicer-137A1/TM6B, w; FRT82B dicer-138E3/TM6B, w; FRT82B pashaLL03360/TM3 Ser, w ; FRT82B pashaKO/TM6B or w ; FRT82B pasha36B2/TM6B. y w; FRT82B was used as a positive control. To generate Drosha clones, hsFLP; FRT42D Ubi-GFP/CyO flies were crossed with w; FRT42D drosha21K11/CyO and y w; FRT42D was used as a positive control. Eggs were collected in vials for 24 hours and heat-shocked after 4 days (3rd instar larvae) in a 37 °C water bath for 1 hour, once per day for 3 days. The larvae were left to pupate and newly eclosed flies were collected. The flies were then aged in fresh vials with wet yeast and transferred to new vials every day or every two days. Mutant cells are marked by the absence of GFP.

Isolation of new mutant alleles

New mutants of pasha and dcr-1 described in this study were identified as part of an on-going genetic screen against a miRNA reporter that affects eye pigmentation (Smibert et al., 2011). New mutations in dicer-1: w; FRT82B dicer-121B2/TM6B, w; FRT82B dicer-130D2/TM6B, w; FRT82B dicer-137A1/TM6B, w; FRT82B dicer-138E3/TM6B and pasha: w; FRT82B pasha36B2/TM6B are described in this study.

Immunochemistry and confocal microscopy

Drosophila ovaries were dissected in Grace’s insect medium (Invitrogen Cat. #11605045) and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes, washed with PBT (PBS + 0.4% Triton X-100), blocked with 5% horse serum for 1 hour and incubated in primary antibody: mouse anti-Ago1 (1B8) (1:1000, gift from Haruhiko Siomi), rabbit anti-Ago1 (1:500, Abcam ab5070) goat anti-GFP (1:3000, Abcam ab6673), Rhodamine-conjugated Phalloidin (1:500, Invitrogen Cat#R415), mouse anti-Orb (6H4) (1:500, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa) mouse anti-HTS (1:20, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank, University of Iowa), rabbit anti-Oskar (1:3000), rabbit anti-cyclin-E (1:500, Santa Cruz Biotech, Inc sc-33748), rabbit anti-cleaved-Caspase 3 (1:100, Cell Signaling, Cat # 9661S), rabbit anti-Vasa (1:50, Santa Cruz Biotech, Inc sc-30210) and rabbit anti-Cup (1:1000, gift from A. Nakamura, Riken Center for Developmental Biology, Kobe, Hyogo, Japan) (Nakamura et al., 2004) at room temperature overnight. Samples were washed with PBT and then incubated overnight with the DNA dye Hoechst 33342 and secondary antibodies. Secondary antibodies used in this study were anti-mouse, rabbit, goat, or guinea pig antibodies that were labelled with Alexa Flour® 488, 546 or 633 dyes (Molecular probes), or with Cy5 or Dylight 649 (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc). All samples were examined and captured using a laser-scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss LSM 510 META, Oberkochen, Germany).

Results

Ago1 protein is expressed in egg chambers and enriched in oocytes

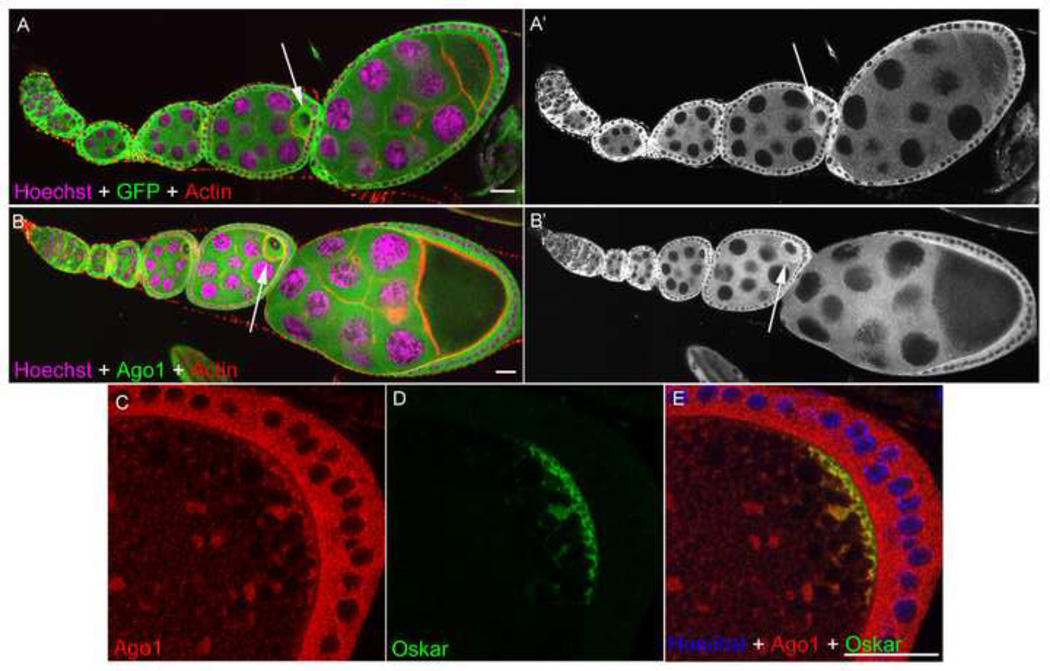

In order to characterize the expression of Ago1 in the Drosophila ovary, we analyzed a protein trap line, CA06914, in which a P-element was inserted in an intron of the ago1 gene so that a fusion protein (Ago1::GFP) was produced and expressed under the endogenous promoter (Buszczak et al., 2007). In CA06914 flies, Ago1::GFP was expressed in the cytoplasm of nurse cells, oocytes and follicle cells. Follicle cells showed much higher expression of GFP than nurse cells. In addition, GFP expression was found to be highly enriched in oocytes at all developmental stages (Figs. 1A and A’). The enriched GFP signals were more or less evenly distributed in the ooplasm at the early- and middle-stages but preferentially localized to the posterior cortex of oocytes at stage 9 and 10.

Fig. 1. Ago1 distribution in Drosophila egg chambers.

(A & A’) Ago1::GFP protein trap line and (B & B’) Ago1 antibody staining in the Drosophila egg chambers showing the distribution of Ago1 protein. Ago1 is distributed in the cytoplasm but it is enriched in the developing oocyte (arrow) and clearly seen in egg chamber stage 7. GFP / Ago1 are shown in green, DNA in magenta and F-actin in red (C–E) Ago1 colocalizes with Oskar at the posterior cortex of a stage-10 oocyte. Ago1 is shown red, Oskar in green, and DNA in blue Scale bars, 20 µm.

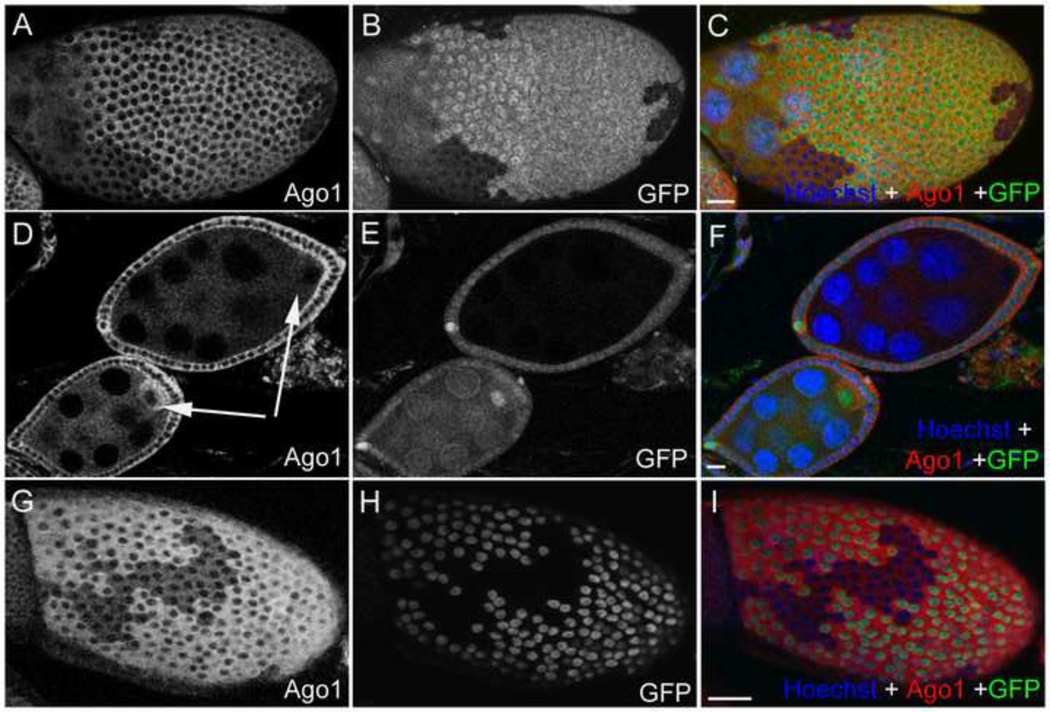

To confirm that Ago1::GFP expression in CA06914 is indicative of Ago1 localization, we stained endogenous Ago1 protein using multiple antibodies against Drosophila Ago1. The expression pattern of Ago1 labelled by two Ago1 antibodies in wild-type ovaries resembled the Ago1::GFP pattern observed in CA06914 flies (Figs. 1A, B, S1). Double-staining of Ago1 and Oskar revealed that they colocalized at the posterior cortex in stage 10 oocytes (Figs. 1C–E). The expression pattern of Ago1 protein was further confirmed by clonal analysis of ago1 mutants. The Ago1 antibodies was markedly reduced in ago1 mutant follicle cells and germline cells (Figs. 2A–F). Within the germline, the reduction in Ago1 is most obvious in the oocyte, where the relative enrichment of Ago1 protein compared to the nurse cells (Figure 1B) was abolished or greatly decreased (Fig. 2D). We made similar observations when analyzing clones of all three ago1 mutant alleles; ago1k08121, ago114, and ago1EMS (Figs . 2, S2).

Fig. 2. Ago1 staining is reduced in ago1 mutants and increases upon overexpression.

(A–F) Mutant clones (GFP −ve) show lower expression of Ago1 compared to wild-type (GFP +ve) cells. (A–C) Ago1 expression in follicle cell clones of the ago1k08121 mutant. (D–F) Ago1 expression in germline clones. Ago1 enrichment in the oocyte was also dramatically reduced in the ago1k08121 mutant clones compared to positive control (arrow). (G–I) Overexpression using an inducible GAL4 driving UAS-Ago1 shows overexpressing clones (GFP +ve) have brighter Ago1 staining compared to wild-type (GFP −ve) cells. Scale bars, 20 µm.

Finally, we used an inducible GAL4 driver to overexpress Ago1 in “flip out” clones, where the co-expression of a UAS-GFP transgene marks the cells that are overexpressing Ago1 (Zecca and Struhl, 2002). Staining of follicle cells for Ago1 revealed that Ago1 expression in GFP positive cells was clearly higher than that in GFP negative cells (Figs. 2G–I). Together, these data demonstrate that the expression pattern detected by the Ago1 protein trap is representative of endogenous Ago1 and that the antibodies we used are specific to Ago1.

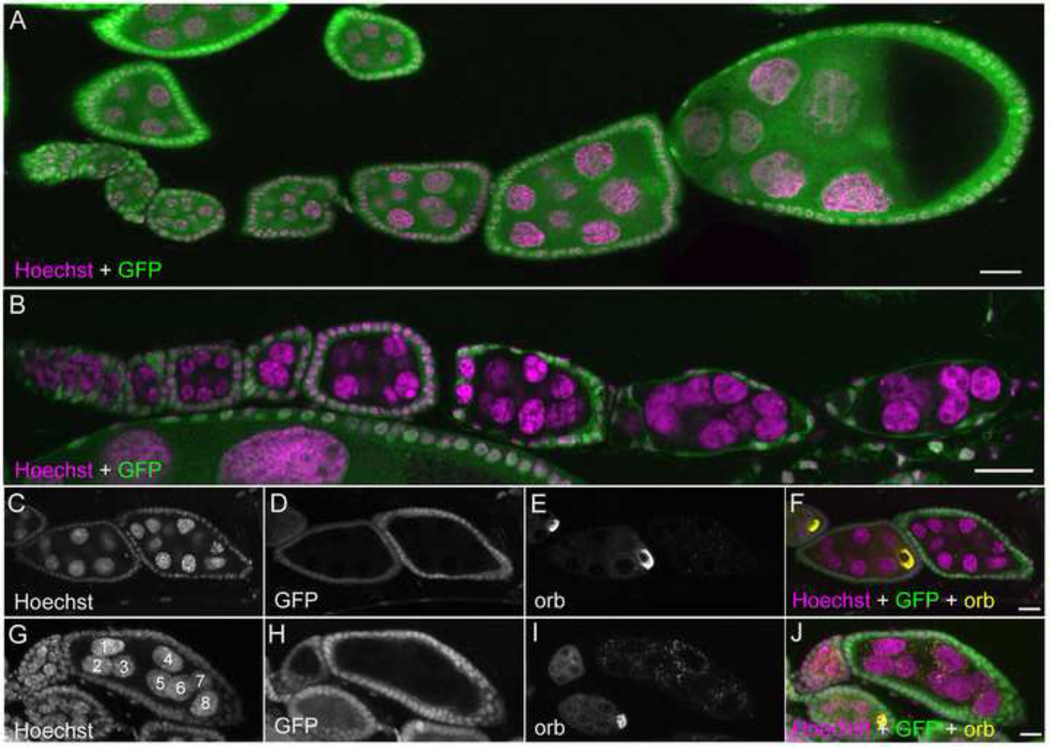

Ago1 mutations affect germline cell division and oocyte formation

To further investigate the role of Ago1 in the egg chambers, we analyzed ago1k08121 mutant germline clones. These clones have a variable phenotype of oocyte loss (Table 1). The 1/3 of egg chambers in which the oocyte failed to form still survived and continued to grow in size (Fig.3A and B). In wild-type egg chambers, follicle cells begin migrating to the posterior side (where the oocyte resides) at stage 9. However, in those egg chambers without an oocyte, follicle cells did not migrate but degenerate at stage 9, resulting in nurse cell-only egg chambers (Fig. 3B) Using an antibody against the oocyte marker Orb, we observed that some egg chambers failed to develop an oocyte (Fig. 3C–J and Table 1). This suggests that oocyte determination might be affected in the absence of Ago1. Despite approximately 2/3 of egg chambers producing oocytes, and in some cases embryos that were successfully laid, in no cases did the ago1 mutant embryos survive embryogenesis (data not shown). Nurse cells in the egg chambers devoid of oocytes continued to grow.

Table 1.

Clonal analysis of ago1 egg chambers

| 7 DAE | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total ovaries counted |

Ovaries with clones |

Clones | Clones per total ovaries |

Normal clones |

Clones with no oocyte |

||||||

| 2 NCs | 4 NCs | 8 NCs | 16 NCs | 32 NCs | Total clones |

||||||

| Control | 58 | 48 | 532 | 9.17 | 532 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| ago1k08121 | 47 | 29 | 142 | 3.02 | 135 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.4%) | 4 (2.8%) | 1 (0.7%) | 7 |

| ago114 | 52 | 39 | 160 | 3.08 | 158 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 |

| ago1EMS | 68 | 14 | 50 | 0.74 | 17 | 1 (2%) | 5 (10%) | 16 (32%) | 11 (22%) | 0 (0%) | 33 |

| 14 DAE | |||||||||||

| Total ovaries counted |

Ovaries with clones |

Clones | Clones per total ovaries |

Normal clones |

Clones with no oocyte |

||||||

| 2 NCs | 4 NCs | 8 NCs | 16 NCs | 32 NCs | Total clones |

||||||

| Control | 81 | 63 | 758 | 9.36 | 758 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| ago1k08121 | 84 | 43 | 172 | 2.05 | 106 | 2 (3%) | 0 (0%) | 55 (32%) | 8 (4.6%) | 1 (0.6%) | 66 |

| ago114 | 94 | 56 | 261 | 2.78 | 191 | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 65 (25%) | 3 (1.1%) | 1 (0.4%) | 70 |

| ago1EMS | 106 | 31 | 117 | 1.10 | 69 | 3 (2.6%) | 3 (2.6%) | 35 (30%) | 7 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 48 |

Fig. 3. Loss of Ago1 disrupts oocyte formation and germline cell division.

(A) A heterozygous GFP +ve ovariole. (B) Ovariole comprised of germline cell clones of ago1k08121. Follicle cells in late stage egg chambers seem to be degrading. (C–F) Two neighbouring ago1 mutant egg chambers, one with an oocyte and one without (orb staining marks the oocyte). (G–J) ago1k08121 clone with only 8 nurse cells and no oocyte formation. Scale bars, 20 µm.

We analyzed the effects of three ago1 alleles during Drosophila oogenesis by clonal analysis and extended our investigations from 7 days to 14 days after eclosion (DAE) so that transient clones (non-stem cell derived clones), even growing slower, would in theory, not be present in the ovaries (Table 1). Fewer clones were present for all three ago1 alleles than in control groups. Both ago1k08121 and ago114 had similar phenotypes with approximately 3 clones per ovary at 7 DAE, while ago1EMS had a more severe phenotype with only 0.74 clones per ovary. All alleles had fewer clones than the control groups, which had an average of 9.17 clones per ovary. At 7 DAE, ago1k08121 and ago114 clones had a low rate of oocyte-less egg chambers (5% and 1.25%, respectively). The frequency of oocyte-less egg chambers increased dramatically at 14 DAE (38% in ago1k08121 and 27% in ago114, Table 1). The most commonly observed developmental arrest amongst the oocyte-less egg chambers was at 8 nurse cells. In the most severe allele, ago1EMS, 66% (33/50) of egg chambers exhibited an oocyte-less phenotype, even at 7 DAE. Among the oocyte-less egg chambers, half of them (16/33) contained 8 nurse cells, and about 20% have only 2 or 4 nurse cells. This indicates that Ago1 is involved in controlling germline cell division.

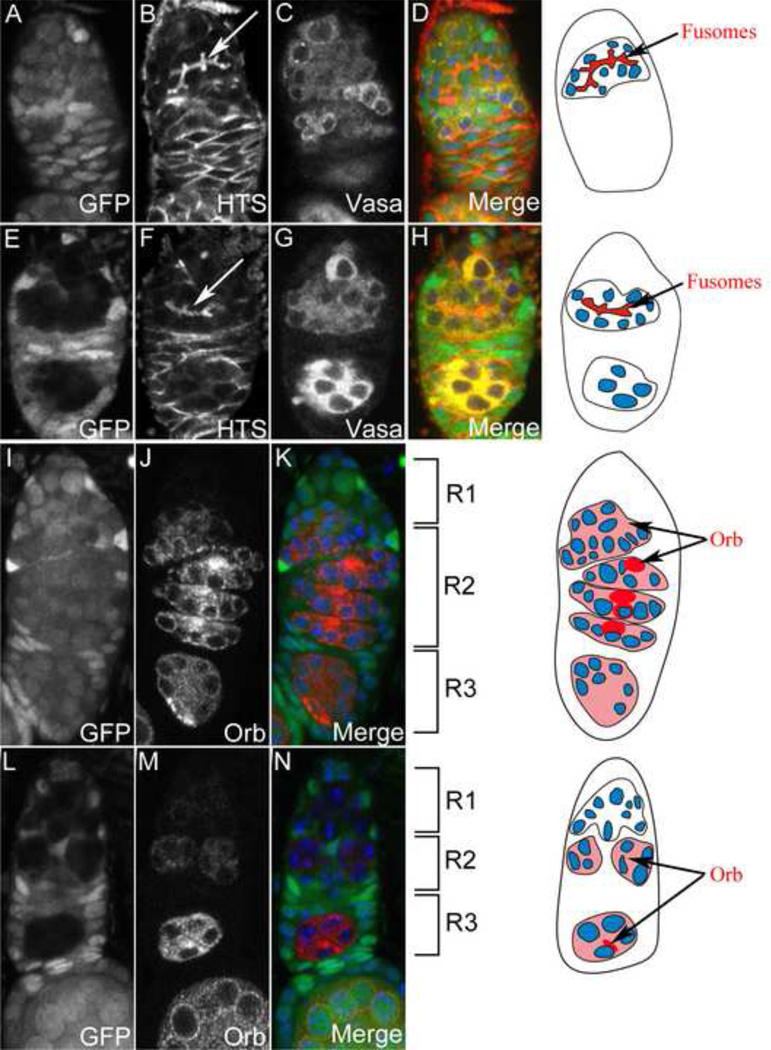

The Ago1 phenotype manifests in the germarium

To assess these phenotypes further, we examined the germarium of ago1k08121 clones at 14 DAE. First we double stained the germarium against Vasa and Hu-li Tai Shao (HTS), the Drosophila homologue of Adducin which labels the fusomes (Figure 4A–H). Fusomes are an important feature in Drosophila cyst division because its large structure which also contain α- and β-spectrin connects the cyst cells through the ring canals (de Cuevas et al., 1996; Lin et al., 1994). In wild-type germarium (Figure 4A–D), the cystoblasts divide 4 times to produce 16-cell cysts by the time they reach region 2A. However, in ago1 mutant germarium, we observed that only 8-cell cysts with smaller and less branched fusomes were presented in region 2 (Figs. 4E–H). Furthermore, ago1 mutant germarium are also smaller, with a noticeably smaller region 2 as shown with an antibody against Orb (Figure 4L–M, compare to wild-type, Figs. 4I–K). However, the ago1 mutant clones did not show appreciably different cleaved-caspase 3 staining with no staining detected on ago1k08121 (n=26), ago114 (n=47), ago1EMS (n=38) and FRT control (n=67) germarium clones. Therefore they do not appear to be undergoing apoptosis (Figs. S3A–I). To determine if the phenotype is due to the misregulation of cell division, we stained the clone cysts againts Cyclin E. Cyclin E staining was detected in 58% (14/24) of ago1k08121, 48% (11/23) of ago114 and 60% (12/20) of ago1EMS region 1 clone cyts in the germarium compared to 70% (19/27) in the FRT control, demonstrating that Cyclin E is not misregulated in the mutant cells (Figs. S3J–L).

Fig. 4. ago1 phenotype manifests in the germarium.

(A–H) Germarium with GFP +ve wild-type clones (A–D) showing normal branching of the fusomes (arrow) compared to GFP −ve ago1 mutant clones (E–H) showing less brancing of the fusomes (arrow). In merge pictures, GFP - green, HTS - red and Vasa - yellow. (I–N) Germarium with GFP +ve wild type clones (I–K) showing normal size germarium compared to the smaller GFP −ve ago1 mutant clones (L–N) germarium. In merge pictures, GFP – green and Orb – red. R1, R2 and R3 denotes to region 1, region 2 and region 3 in the germarium.

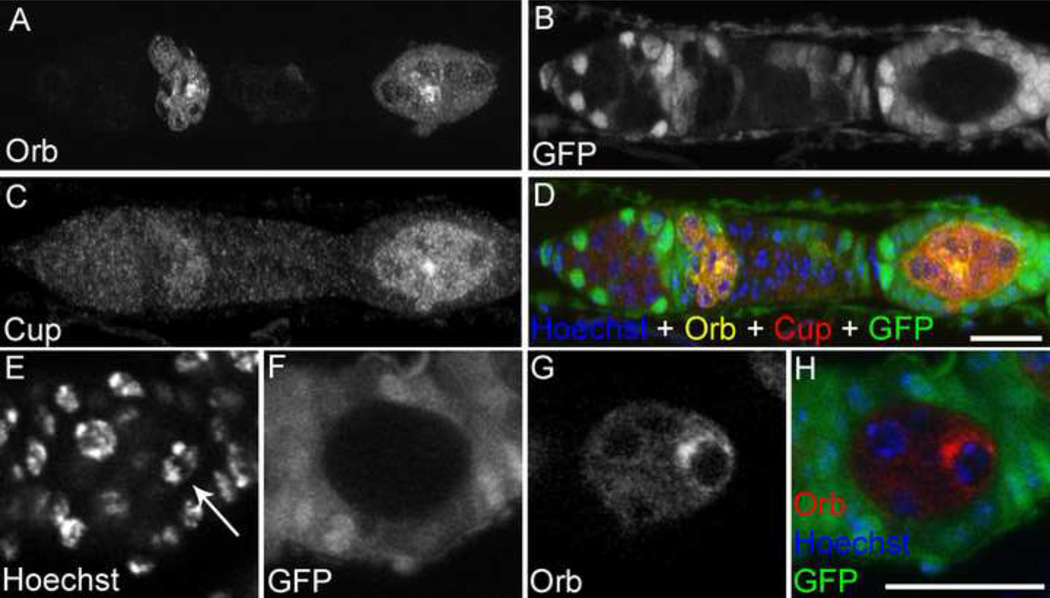

Next, we examined Orb and Cup expressions in the germarium to further study the oocyte determination defect. Orb is very dynamicly expressed in the germarium and its expression starts in region 2A (Figure 4J) in a relatively ubiquitous pattern (Christerson and Mckearin, 1994; Lantz et al., 1994). As it reaches region 2B, the Orb protein starts to localizes to the pro-oocytes and finally to the determined oocyte. Cup protein however, starts accumulating in the oocyte of region 2B (Piccioni et al., 2005; Zappavigna et al., 2004). Intriguingly, both Orb and Cup seemed to be expressed in the egg chambers with 8 nurse cells even though the oocyte is not properly formed (Figs. 5A–D). Orb protein accumulated in region 2A but Cup was not detected until stage 1 egg chamber (Figs. 5A–D). Furthermore, analysis of stage 1 egg chamber mutant clones showing the 8 nurse cell phenotype indicated that although the egg chamber failed to form a proper oocyte, it produced a pseudo-oocyte without a condensed karyosome. However, the accumulation of Orb protein in the pseudo-oocyte seemed to be unaffected (Figs. 5E–H).

Fig. 5. Orb and Cup staining in the pseudo-oocyte.

(A–D) Germarium with GFP −ve ago1 mutant clones stained with anti-Orb and anti-Cup. Orb protein is present in region 2B while Cup can only be seen in stage 1 egg chamber. (E–H) Stage 1 egg chamber with 8 nurse cells stained with anti-Orb showing the Orb protein accumulates at the pseudo-oocyte. Scale bars, 20 µm.

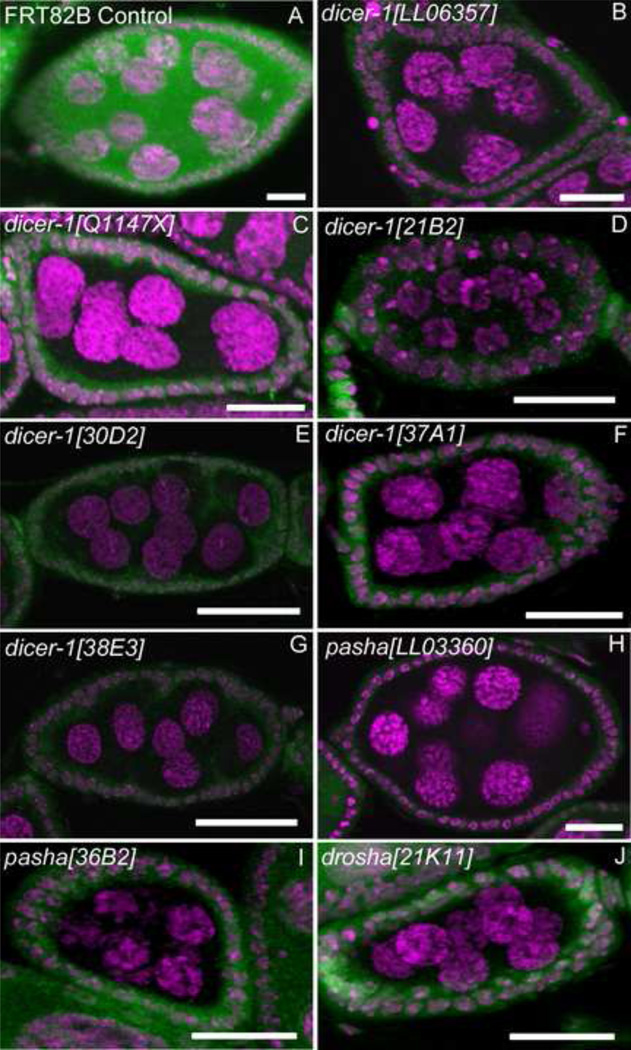

dicer-1, pasha and drosha exhibit similar effects on oogenesis as ago1

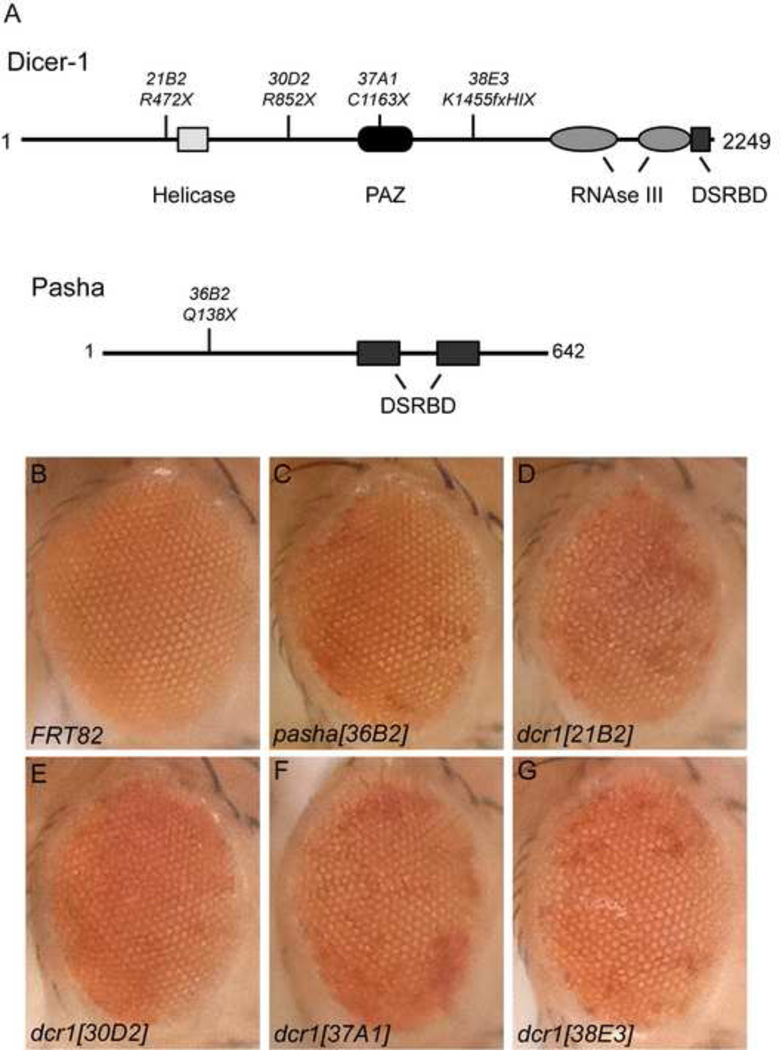

Since Ago1 is a critical effector of miRNA function, we set out to investigate if mutation of genes that are involved in miRNA biogenesis have similar developmental defects as Ago1. We obtained previously characterized alleles of genes involved in miRNA biogenesis including dicer-1Q1147X, dicer-1LL06357, pashaLL03360 and drosha21K11 stocks (Berdnik et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2004; Smibert et al., 2011). Additionally, to rule out the effects of genetic background in our assay, we also analyzed newly generated alleles of dicer-1 and pasha (Fig 6), which we isolated from an on-going genetic screen (Smibert et al, 2011). These mutants, dicer-121B2, dicer-130D2, dicer-137A1, dicer-138E3 and pasha36B2 all contain premature stop codons and are expected to be null for protein function (Fig 6). All dicer-1 alleles examined exhibit the same phenotype of egg chambers with 8 nurse cells and lacking an oocyte with 30–53% penetrance, phenocopying ago1EMS mutant at 7 DAE (Fig. 7 and Table 2). One pasha mutant allele, pashaLL03360, behaved like wild-type in this assay (n=128, Fig. 7H). However, the newly generated pasha mutant, pasha36B2 phenocopied ago1EMS and all dicer-1 mutant alleles with 50% penetrance (Fig. 7I and Table 2). The drosha21K11 mutant also shows similar penetrance of 48% (Fig. J and Table 2). Together, these results suggest a role for the miRNA pathway in oogenesis.

Fig. 6. Identification and characterization of new dicer-1 and pasha alleles.

(A) Schematic representations of of Dicer-1 and Pasha proteins showing important domains and locations of the mutations. (B–G) Adult eyes with eyFLP-generated clones of the indicated mutation in the background of GMR-w-miR. Loss of miRNA activity results in more white gene product and patches of darker pigmentation.

Fig. 7. dicer-1, pasha and drosha null mutants exhibit the same phenotype as Ago-1 mutants.

(A) Positive control (GFP +ve) showing a normal egg chamber. (B–G) Selected examples demonstrating the ~30–60% of germline clones for the indicated genotypes that exhibit the oocyte-less 8 nurse cell egg chamber phenotype. Six independent dicer-1 mutant alleles showing selected egg chamber exhibiting the same germline cell division and oocyte formation defect as in an ago1 mutant. (H–I) Germline clones of two independent pasha alleles. pashaLL03360 does not show the same germline cell division or oocyte formation defects as in ago1, while pasha36B2 phenocopies the ago1 and dicer-1 mutant phenotype. (J) drosha mutant showing the 8 nurse cells phenotype. DNA is shown in margenta. Scale bars, 20 µm.

Table 2.

Clonal analysis of dicer-1, pasha and drosha egg chambers

| 7 DAE | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clones | Normal clones |

Clones with no oocyte |

||||||

| 2 NCs | 4 NCs | 8 NCs | 16 NCs | 32 NCs | Total clones |

|||

| Control FRT82B | 187 | 187 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| dicer-1LL06357 | 104 | 70 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 31 (30%) | 3 (0.03%) | 0 (0%) | 34 |

| dicer-1Q1147X | 70 | 41 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 26 (37%) | 3 (0.04%) | 0 (0%) | 29 |

| dicer-121B2 | 42 | 19 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 19 (45%) | 4 (0.1%) | 0 (0%) | 23 |

| dicer-130D2 | 55 | 31 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 23 (42%) | 1 (0.02%) | 0 (0%) | 24 |

| dicer-137A1 | 43 | 18 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 25 (58%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 25 |

| dicer-138E3 | 56 | 20 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 35 (63%) | 1 (0.02%) | 0 (0%) | 36 |

| pashaLL03360 | 128 | 128 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 |

| pasha36B2 | 121 | 54 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 59 (49%) | 8 (0.07%) | 0 (0%) | 67 |

| drosha21K11 | 159 | 72 | 1 (0.01%) | 3 (0.02%) | 77 (48%) | 6 (0.04%) | 0 (0%) | 87 |

Discussion

Ago1 in oogenesis

Drosophila Ago1 forms a complex with mature miRNAs and acts to repress mRNAs. However, the spatial distribution of Ago1 during development has not been well characterized. The protein trap lines from Carnegie Protein Trap library provide a powerful way to characterize the spatial and temporal distribution of a particular gene (Buszczak et al., 2007). The distribution of Ago1 in the cytoplasm has been described and shown to be localized in small puncta in the egg chamber (Reich et al., 2009). Our findings using two independent assays for Ago1 localization have shown that Ago1 is enriched in the oocyte and mutant analysis has revealed a role in oocyte formation and germline cell division.

Nurse cells supply nutrition for oocyte growth. The germline cell division defect described here has been previously observed in a cyclin-E mutant where 30% of the egg chambers have 8 cells, but the egg chamber still manages to develop an oocyte (Lilly and Spradling, 1996). Mata et al., (2000) have also described 8 cell egg chambers when String is over expressed as well as in a tribbles mutant. Both String overexpression and the tribbles mutant have 8 cells per egg chamber, but only a proportion fail to develop an oocyte. This defect occurs in the germarium while the cyst cells are undergoing mitosis. In the wild-type situation, the cystoblast divides four times to produce 16 cyst-cells. In the absence of ago1, some of the cystoblasts undergoes only three divisions, producing 8-cell cysts. However, the ago1 mutant ovarioles with this phenotype still express Cyclin E, suggesting that mitosis is still occurring although perhaps at a slower rate. Combined with the oocyte formation defect, the resulting egg chambers only have 8 nurse cells and lack an oocyte. The cyst cell division in the germarium is not well understood. One potential explanation for the observed phenotype is that when Ago1, and presumably miRNA mediated gene regulation, are lost, the signal to stop dividing occurs early. Another possibility is because the egg chamber grows more slowly, the oocyte reaches region 2A before it manages to divide 4 times, thus receiving a premature signal to stop dividing, or being prematurely enclosed by the migrating follicle cells. The smaller germarium of ago1 mutant might also be an effect of cyst-cells dividing slower. The defective egg chamber however still manages to grow. Furthermore, the observation of Orb protein in region 2 and the stage 1 egg chamber could mean that the oocyte is trying to enter meiosis (Senger et al., 2011), or have entered meiosis but unable to maintain the meiotic state because the Orb accumulation is lost in later stage egg chambers and no oocyte is formed. The oocyte differentiation and maintainance in the meiotic cycle are reliant to the microtubule based transport of mRNAs and proteins from the nurse cells to the oocyte (Huynh and St Johnston, 2004). Orb, the germline specific RNA-binding protein starts accumulating in the oocyte at region 2a in a microtubule-dependent manner. orb mutant causes the egg chamber to produce 8 nurse cells and no oocyte (Huynh and St Johnston, 2000), similar to the ago1, dicer-1, drosha and pasha mutant phenotype seen in this study. However, since Orb is still expressed, we could rule out that the phenotype is cause by loss of orb function. The inability to maintain the accumulation of Orb in the oocyte in later stages of oogenesis could relate to defect on maintaining the meiotic cycle (Cox et al., 2001; Hong et al., 2003; Huynh and St Johnston, 2004).

Ago1 and senescence

Our results have shown that a greater proportion of older ago1 flies exhibit the 8-nurse cell phenotype than younger mutant flies. This could be due to the level of Ago1 in older flies decreasing to a certain threshold level to show an obvious phenotype. There is also the possibility that the remaining or leaky (due to hypomorphic allele) Ago1 is diluted through GSC division and maintainance such that GSCs from flies at 14 DAE have less Ago1 than GSCs from flies at 7 DAE. Previous studies suggest that GSC loss in ago1 mutants are age-dependent (Yang et al., 2007). This could potentially explain the age-dependent 8-nurse cell phenotype that we observed in ago1 mutants. Self-renewed GSC in the absence of Ago1 could be defective, so cystoblasts produced by defective GSC might not be able to divide normally. Although ago1k08121 and ago114 showed a more severe phenotype in older flies, ago1EMS, as the strongest allele, showed very severe phenotype even in young flies. This is consistent with a previous study (Yang et al., 2007).

The role of miRNAs in oogenesis

Ago1, Dicer-1, Loquacious and PIWI have roles in small RNA biogenesis and all of them have been shown to be important for germline stem cell maintenance (Forstemann et al., 2005; Hatfield et al., 2005; Jin and Xie, 2007; Megosh et al., 2006; Yang et al., 2007). The role of miRNAs regulating GSC division was first reported by Hatfield et al., (2005) by studying null mutants of dicer-1. A similar study looking at ago1 mutants revealed that Ago1 also regulates the fate of the GSC (Yang et al., 2007). Both of these studies showed a similar phenotypic defect in the germline. Furthermore, there are some cases where mutations in individual miRNA genes show phenotypes in the germline cells. The miRNA bantam has been previously found to be important for GSC maintenance (Shcherbata et al., 2007). Both miR-278 and miR-7 have been shown to regulate GSC division (Yu et al., 2009). Also, miR-184 controls GSC differentiation, dorsoventral patterning of the egg shell and anteroposterior patterning (Iovino et al., 2009). Although the effect in the GSC is quite reproducible from previous studies, it is not uncommon to see that knockouts of miRNA biogenesis factors. Bejarno et al.,(2010) showed this quite well in the developing wing primordium where clones lacking mir-9a upregulate dLMO and induce wing notching. This phenotype is however not fully reproducible in dicer-1 and pasha mutant clones. The effect of removing all miRNA could cancel the effect of a single miRNA mutation.

Our study shows that the dicer-1, pasha and drosha mutants phenocopy the ago1 mutant during oogenesis. However, one Pasha mutant allele, pashaLL03360, did not phenocopy ago1 and dicer-1. This mutant is a piggyBac insertion into the 5’UTR of pasha and despite showing a convincing loss of pasha protein in adult neurons (Berdnik et al., 2008) it is possible that the allele may only be hypomorphic in the ovary. Pasha has not been studied in the Drosophila germline but it has been shown to play a role in olfactory neuron morphogenesis in the Drosophila adult brain (Berdnik et al., 2008). In that study, they found that Pasha and Dicer-1 are required for arborization of projection neurons but not Ago1. This argues for Ago1-independent roles of Dicer-1 and Pasha. Alternatively, the a go1 mutant used in that study and this study, ago1k08121 may not be completely null or the protein from the parental cell could be compensating for the loss of Ago1. Recent studies have suggested that neural processes are exquisitely sensitive to miRNA pathway activity (Smibert et al., 2011; Stark et al., 2008) so perhaps a more complete loss of Pasha function is required to produce phenotypic consequences in the ovary compared to neurons. Indeed, the relative phenotypic strength of ago1k08121 versus ago1EMS1 and the null mutants of miRNA biogenesis enzymes argues for the hypomorphic nature of ago1k08121. Mirtrons are another class of small RNAs which bypass Pasha/Drosha processing by utilizing the splicing machinery, but are still processed by Dicer-1 and loaded into Ago1 (Okamura et al., 2008; Ruby et al., 2007). However, drosha21K11 and the newly generated pasha36B2 mutant show the same phenotype, qualitatively and quantitatively, as ago1 and dicer-1 mutants. This argues that the majority of the phenotype we observed is due to loss of canonical miRNAs and that miRtrons have a comparably insignificant role (if any) in the phenotypes analysed. Altogether, our study reaffirms that loss of miRNA function at various stages of biogenesis or effector function has important phenotypic consequences for oogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Drs. Allan Spardling, Haruhiko Siomi, Richard Carthew, Liqun Luo, Barry Dickson and Peng Jin, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for providing fly stocks and antibodies. We also thank Zillah Deussen and Mayte Siswick for technical support; Andy Bassett, Siân Davies and Ömür Tastan for reading this manuscript. This work was supported by the UK Medical Research Council (to J.L.L.), Malaysia Ministry of Higher Education (to G.A.). Work in E.C.L.'s group was supported by the Starr Cancer Consortium (I3-A139) and the National Institutes of Health (R01-GM083300)

References

- Ambros V. The functions of animal microRNAs. Nature. 2004;431:350–355. doi: 10.1038/nature02871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bejarano F, Smibert P, Lai EC. miR-9a prevents apoptosis during wing development by repressing Drosophila LIM-only. Dev Biol. 2010;338:63–73. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.11.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berdnik D, Fan AP, Potter CJ, Luo L. MicroRNA processing pathway regulates olfactory neuron morphogenesis. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1754–1759. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohnsack MT, Czaplinski K, Gorlich D. Exportin 5 is a RanGTP-dependent dsRNA-binding protein that mediates nuclear export of pre-miRNAs. Rna. 2004;10:185–191. doi: 10.1261/rna.5167604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buszczak M, Paterno S, Lighthouse D, Bachman J, Planck J, Owen S, Skora AD, Nystul TG, Ohlstein B, Allen A, Wilhelm JE, Murphy TD, Levis RW, Matunis E, Srivali N, Hoskins RA, Spradling AC. The carnegie protein trap library: a versatile tool for Drosophila developmental studies. Genetics. 2007;175:1505–1531. doi: 10.1534/genetics.106.065961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrington JC, Ambros V. Role of microRNAs in plant and animal development. Science. 2003;301:336–338. doi: 10.1126/science.1085242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christerson LB, Mckearin DM. Orb Is Required for Anteroposterior and Dorsoventral Patterning during Drosophila Oogenesis. Genes & Development. 1994;8:614–628. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.5.614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DN, Lu B, Sun TQ, Williams LT, Jan YN. Drosophila par-1 is required for oocyte differentiation and microtubule organization. Curr Biol. 2001;11:75–87. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00027-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czech B, Zhou R, Erlich Y, Brennecke J, Binari R, Villalta C, Gordon A, Perrimon N, Hannon GJ. Hierarchical rules for Argonaute loading in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 2009;36:445–456. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Cuevas M, Lee JK, Spradling AC. alpha-spectrin is required for germline cell division and differentiation in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 1996;122:3959–3968. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.12.3959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denli AM, Tops BB, Plasterk RH, Ketting RF, Hannon GJ. Processing of primary microRNAs by the Microprocessor complex. Nature. 2004;432:231–235. doi: 10.1038/nature03049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dietzl G, Chen D, Schnorrer F, Su KC, Barinova Y, Fellner M, Gasser B, Kinsey K, Oppel S, Scheiblauer S, Couto A, Marra V, Keleman K, Dickson BJ. A genome-wide transgenic RNAi library for conditional gene inactivation in Drosophila. Nature. 2007;448:151–156. doi: 10.1038/nature05954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djuranovic S, Zinchenko MK, Hur JK, Nahvi A, Brunelle JL, Rogers EJ, Green R. Allosteric regulation of Argonaute proteins by miRNAs. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:144–150. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynt AS, Lai EC. Biological principles of microRNA-mediated regulation: shared themes amid diversity. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:831–842. doi: 10.1038/nrg2455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstemann K, Horwich MD, Wee L, Tomari Y, Zamore PD. Drosophila microRNAs are sorted into functionally distinct argonaute complexes after production by dicer-1. Cell. 2007;130:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstemann K, Tomari Y, Du T, Vagin VV, Denli AM, Bratu DP, Klattenhoff C, Theurkauf WE, Zamore PD. Normal microRNA maturation and germ-line stem cell maintenance requires Loquacious, a double-stranded RNA-binding domain protein. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e236. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard A, Sachidanandam R, Hannon GJ, Carmell MA. A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins. Nature. 2006;442:199–202. doi: 10.1038/nature04917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregory RI, Yan KP, Amuthan G, Chendrimada T, Doratotaj B, Cooch N, Shiekhattar R. The Microprocessor complex mediates the genesis of microRNAs. Nature. 2004;432:235–240. doi: 10.1038/nature03120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J, Lee Y, Yeom KH, Kim YK, Jin H, Kim VN. The Drosha-DGCR8 complex in primary microRNA processing. Genes Dev. 2004;18:3016–3027. doi: 10.1101/gad.1262504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatfield SD, Shcherbata HR, Fischer KA, Nakahara K, Carthew RW, Ruohola-Baker H. Stem cell division is regulated by the microRNA pathway. Nature. 2005;435:974–978. doi: 10.1038/nature03816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong A, Lee-Kong S, Iida T, Sugimura I, Lilly MA. The p27cip/kip ortholog dacapo maintains the Drosophila oocyte in prophase of meiosis I. Development. 2003;130:1235–1242. doi: 10.1242/dev.00352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh JR, St Johnston D. The role of BicD, Egl, Orb and the microtubules in the restriction of meiosis to the Drosophila oocyte. Development. 2000;127:2785–2794. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.13.2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huynh JR, St Johnston D. The origin of asymmetry: early polarisation of the Drosophila germline cyst and oocyte. Curr Biol. 2004;14:R438–R449. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.05.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iovino N, Pane A, Gaul U. miR-184 has multiple roles in Drosophila female germline development. Dev Cell. 2009;17:123–133. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z, Xie T. Dcr-1 maintains Drosophila ovarian stem cells. Curr Biol. 2007;17:539–544. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka Y, Takeichi M, Uemura T. Developmental roles and molecular characterization of a Drosophila homologue of Arabidopsis Argonaute1, the founder of a novel gene superfamily. Genes Cells. 2001;6:313–325. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2001.00427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim K, Lee YS, Harris D, Nakahara K, Carthew RW. The RNAi pathway initiated by Dicer-2 in Drosophila. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 2006;71:39–44. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2006.71.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim VN, Nam JW. Genomics of microRNA. Trends Genet. 2006;22:165–173. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai EC. Micro RNAs are complementary to 3' UTR sequence motifs that mediate negative post-transcriptional regulation. Nat Genet. 2002;30:363–364. doi: 10.1038/ng865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lantz V, Chang JS, Horabin JI, Bopp D, Schedl P. The Drosophila orb RNA-binding protein is required for the formation of the egg chamber and establishment of polarity. Genes Dev. 1994;8:598–613. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.5.598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YS, Nakahara K, Pham JW, Kim K, He Z, Sontheimer EJ, Carthew RW. Distinct roles for Drosophila Dicer-1 and Dicer-2 in the siRNA/miRNA silencing pathways. Cell. 2004;117:69–81. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00261-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly MA, Spradling AC. The Drosophila endocycle is controlled by Cyclin E and lacks a checkpoint ensuring S-phase completion. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2514–2526. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H, Yue L, Spradling AC. The Drosophila fusome, a germline-specific organelle, contains membrane skeletal proteins and functions in cyst formation. Development. 1994;120:947–956. doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund E, Guttinger S, Calado A, Dahlberg JE, Kutay U. Nuclear export of microRNA precursors. Science. 2004;303:95–98. doi: 10.1126/science.1090599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin R, Smibert P, Yalcin A, Tyler DM, Schafer U, Tuschl T, Lai EC. A Drosophila pasha mutant distinguishes the canonical microRNA and mirtron pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 2009;29:861–870. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01524-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata J, Curado S, Ephrussi A, Rorth P. Tribbles coordinates mitosis and morphogenesis in Drosophila by regulating string/CDC25 proteolysis. Cell. 2000;101:511–522. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80861-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megosh HB, Cox DN, Campbell C, Lin H. The role of PIWI and the miRNA machinery in Drosophila germline determination. Curr Biol. 2006;16:1884–1894. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.08.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakahara K, Kim K, Sciulli C, Dowd SR, Minden JS, Carthew RW. Targets of microRNA regulation in the Drosophila oocyte proteome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:12023–1208. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500053102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura A, Sato K, Hanyu-Nakamura K. Drosophila cup is an eIF4E binding protein that associates with Bruno and regulates oskar mRNA translation in oogenesis. Dev Cell. 2004;6:69–78. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Chung WJ, Ruby JG, Guo H, Bartel DP, Lai EC. The Drosophila hairpin RNA pathway generates endogenous short interfering RNAs. Nature. 2008;453:803–806. doi: 10.1038/nature07015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Ishizuka A, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Distinct roles for Argonaute proteins in small RNA-directed RNA cleavage pathways. Genes Dev. 2004;18:1655–1666. doi: 10.1101/gad.1210204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamura K, Liu N, Lai EC. Distinct mechanisms for microRNA strand selection by Drosophila Argonautes. Mol Cell. 2009;36:431–444. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccioni F, Zappavigna V, Verrotti AC. A cup full of functions. RNA Biol. 2005;2:125–128. doi: 10.4161/rna.2.4.2416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich J, Snee MJ, Macdonald PM. miRNA-dependent translational repression in the Drosophila ovary. PLoS One. 2009;4:e4669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruby JG, Jan CH, Bartel DP. Intronic microRNA precursors that bypass Drosha processing. Nature. 2007;448:83–86. doi: 10.1038/nature05983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saito K, Ishizuka A, Siomi H, Siomi MC. Processing of pre-microRNAs by the Dicer-1-Loquacious complex in Drosophila cells. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senger S, Csokmay J, Akbar T, Jones TI, Sengupta P, Lilly MA. The nucleoporin Seh1 forms a complex with Mio and serves an essential tissue-specific function in Drosophila oogenesis. Development. 2011;138:2133–2142. doi: 10.1242/dev.057372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbata HR, Ward EJ, Fischer KA, Yu JY, Reynolds SH, Chen CH, Xu P, Hay BA, Ruohola-Baker H. Stage-specific differences in the requirements for germline stem cell maintenance in the Drosophila ovary. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:698–709. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert P, Bejarano F, Wang D, Garaulet DL, Yang JS, Martin R, Bortolamiol-Becet D, Robine N, Hiesinger PR, Lai EC. A Drosophila genetic screen yields allelic series of core microRNA biogenesis factors and reveals post-developmental roles for microRNAs. RNA. 2011 doi: 10.1261/rna.2983511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling AC. Developmental genetics of oogenesis. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. 1993;1:1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Stark A, Bushati N, Jan CH, Kheradpour P, Hodges E, Brennecke J, Bartel DP, Cohen SM, Kellis M. A single Hox locus in Drosophila produces functional microRNAs from opposite DNA strands. Genes Dev. 2008;22:8–13. doi: 10.1101/gad.1613108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomari Y, Du T, Zamore PD. Sorting of Drosophila small silencing RNAs. Cell. 2007;130:299–308. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie T, Spradling AC. decapentaplegic is essential for the maintenance and division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Cell. 1998;94:251–260. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81424-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Chen D, Duan R, Xia L, Wang J, Qurashi A, Jin P, Chen D. Argonaute 1 regulates the fate of germline stem cells in Drosophila. Development. 2007;134:4265–4272. doi: 10.1242/dev.009159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Qin Y, Macara IG, Cullen BR. Exportin-5 mediates the nuclear export of pre-microRNAs and short hairpin RNAs. Genes Dev. 2003;17:3011–3016. doi: 10.1101/gad.1158803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu JY, Reynolds SH, Hatfield SD, Shcherbata HR, Fischer KA, Ward EJ, Long D, Ding Y, Ruohola-Baker H. Dicer-1-dependent Dacapo suppression acts downstream of Insulin receptor in regulating cell division of Drosophila germline stem cells. Development. 2009;136:1497–1507. doi: 10.1242/dev.025999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zappavigna V, Piccioni F, Villaescusa JC, Verrotti AC. Cup is a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein that interacts with the eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E to modulate Drosophila ovary development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:14800–14805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406451101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecca M, Struhl G. Subdivision of the Drosophila wing imaginal disc by EGFR-mediated signaling. Development. 2002;129:1357–1368. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.6.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.