Abstract

Legumes contain a variety of phytochemicals derived from the phenylpropanoid pathway that have important effects on human health as well as seed coat color, plant disease resistance and nodulation. However, the information about the genes involved in this important pathway is fragmentary in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). The objectives of this research were to isolate genes that function in and control the phenylpropanoid pathway in common bean, determine their genomic locations in silico in common bean and soybean, and analyze sequences of the 4CL gene family in two common bean genotypes. Sequences of phenylpropanoid pathway genes available for common bean or other plant species were aligned, and the conserved regions were used to design sequence-specific primers. The PCR products were cloned and sequenced and the gene sequences along with common bean gene-based (g) markers were BLASTed against the Glycine max v.1.0 genome and the P. vulgaris v.1.0 (Andean) early release genome. In addition, gene sequences were BLASTed against the OAC Rex (Mesoamerican) genome sequence assembly. In total, fragments of 46 structural and regulatory phenylpropanoid pathway genes were characterized in this way and placed in silico on common bean and soybean sequence maps. The maps contain over 250 common bean g and SSR (simple sequence repeat) markers and identify the positions of more than 60 additional phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences, plus the putative locations of seed coat color genes. The majority of cloned phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences were mapped to one location in the common bean genome but had two positions in soybean. The comparison of the genomic maps confirmed previous studies, which show that common bean and soybean share genomic regions, including those containing phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences, with conserved synteny. Indels identified in the comparison of Andean and Mesoamerican common bean 4CL gene sequences might be used to develop inter-pool phenylpropanoid pathway gene-based markers. We anticipate that the information obtained by this study will simplify and accelerate selections of common bean with specific phenylpropanoid pathway alleles to increase the contents of beneficial phenylpropanoids in common bean and other legumes.

Keywords: common bean, soybean, phenylpropanoid pathway, genome sequence, in silico map, comparative mapping

Introduction

Common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and soybean (Glycine max L. Merr) belong to the Papilionoid subfamily of legumes. Both species are grown for their seeds and the protein, oil and starch they contain. The soybean, which is rich in protein (40 g kg−1) and oil (20 g kg−1) is the most economically valuable legume, worth over $100B/y (http://www.soystats.com/2012/Default-frames.htm). However, the common bean is the most important legume for direct human consumption (Broughton et al., 2003), due to it's high protein, complex carbohydrate and dietary fiber content. Beans also contain significant amounts of micronutrients and vitamins, including folate. Both species contain phenylpropanoid pathway-derived bioactive secondary metabolites such as flavonoids, lignans and isoflavones with potential medicinal properties (Mazur and Adlercreutz, 1998; Sirtori, 2001). Compared to soybean, the levels of isoflavones are far lower in common bean, but the levels of various compounds from the phenylpropanoid pathway that act as antioxidants are high. Thus, there is the potential to develop consumer awareness of common bean as a preferred source of these compounds in the diet, and with additional knowledge there is the possibility to increase the levels of these compounds in the common bean through conventional or marker-assisted selection (MAS).

Phenylpropanoids play vital roles in plants' interactions with their environments and have varied and important functions in processes such as: UV protection, disease resistance, nodulation (N2 fixation) and seed coat color determination. In contrast to the good understanding of genetics and biochemistry of seed and flower pigmentation in petunia, Arabidopsis or maize (Lepiniec et al., 2006), the roles of phenylpropanoids and the genes that code for the enzymes in the phenylpropanoid pathway are still poorly understood in the common bean.

Seed, flower and pubescence colors have utility in soybean breeding programs as hybridity markers. Commercial soybean has yellow seed, although natural variation in seed pigmentation exists. Seed coat color in soybean is determined by three independent loci (I, T and R) distinct from flower color-controlling loci (Owen, 1928; Palmer et al., 2004), some of which are associated with genes coding for enzymes of anthocyanin biosynthesis. For example, the I (inhibitor) locus (light, dark or saddled hilum color) was associated with six inverted chalcone synthase (CHS) repeats on chromosome Gm08 (Todd and Vodkin, 1996) and the T locus (tawny brown or gray pubescence color) co-localized with flavonoid 3′ hydroxylase (F3′H) on chromosome Gm06 (Toda et al., 2002; Zabala and Vodkin, 2003). However, the R locus (black, brown or striped seed coat color) mapped on chromosome Gm09 could not be linked with known anthocyanidin synthase (ANS), dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR), or UDP-flavonoid glucosyltransferase genes. Findings by Gillman et al. (2011) suggest that loss of function mutation in an R2R3 MYB transcription factor results in brown hilum and brown seed coat.

Large genetic diversity exists between and within the Mesoamerican (Mesoamerica, Durango and Jalisco) and Andean (Nueva Granada, Chile, and Peru) gene pools of the common bean. They are distinguishable not only by geographic origin but also by seed size, growth habit, environmental adaptation, fertility barriers, resistance to diseases, phaseolin types, isozyme, and molecular marker diversities (Kwak and Gepts, 2009). In common bean, a number of genes control the colors (P, R, J, D, G, B, V, and Rk) and patterns (T, Z, L, J, Bip, and Ana) of seed coats (Prakken, 1970, 1972). Interactions among these genes are important in defining each of the major common bean market classes such as white, black, pinto or cranberry (McClean et al., 2002). Although none of the biochemical functions of the genes have been defined (Hosfield, 2001), it is believed that flavonoids are the pigments responsible for seed coat color in common bean (Beninger et al., 1998). Markers based on the genes that control seed coat color would greatly facilitate germplasm utilization in common bean breeding programs. RAPD (random amplified polymorphic DNA) and STS (sequence-tagged sites) markers associated with seed coat color genes have been identified and mapped on several linkage groups (Brady et al., 1998; Erdmann et al., 2002; McClean et al., 2002). Also, gene-based markers for several enzymes of the flavonoid/anthocyanin pathway (F3H, DFR, and ANS) have been developed (McClean et al., 2002), but their connection with color genes has not been established.

Phenylpropanoids consist of a large group of natural products containing a phenyl ring attached to a 3-C propane side chain (C6-C3). They are synthesized by the enzymes in the phenylpropanoid pathway (Holton and Maizeish, 1995; Dixon and Steele, 1999), which is unique to plants and probably is one of the most studied biochemical pathways. It starts from the aromatic amino acid phenylalanine and leads to the synthesis of a wide variety of phytochemicals including: simple phenylpropanoids, like phenylpropenes, and complex phenolics, such as lignins, lignans, coumarins, isoflavonoids, flavonoids, anthocyanidins, and proanthocyanidins (condensed tannins). The general (central) phenylpropanoid pathway involves three steps: deamination of phenylalanine into trans-cinnamic acid [catalyzed by phenylalanine ammonia-lyase (PAL)], hydroxylation of cinnamate into p-coumaric acid (4-coumaric acid) [catalyzed by cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (C4H)] and ATP-dependent formation of the CoA thioester 4-coumaroyl CoA (p-coumaroyl CoA) [catalyzed by 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL)]. This compound is the substrate for several branches of the pathway leading to biosynthesis of lignin/lignans, flavonoid/anthocyanins and isoflavonoids (Winkel-Shirley, 2001; Dixon, 2005; Dixon et al., 2005; Vogt, 2010). Four structurally and functionally different isoforms of 4CL were detected in soybean (Lindermayr et al., 2002).

Most of the enzymes catalyzing individual steps of the pathway are identified and the genes coding for them are cloned for a number of plant species, including: Arabidopsis thaliana (Meyer et al., 1996; Aguade, 2001), Petunia hybrida (Holton et al., 1993), and maize (Andersen et al., 2008). The regulation of expression of the structural genes encoding the phenylpropanoid pathway enzymes is complex and is thought to occur primarily at the transcription level (Vom Endt et al., 2002; Grotewold, 2005; Hichri et al., 2011; Falcone-Ferreyra et al., 2012). In Arabidopsis, early biosynthetic genes (CHS, CHI, F3H, and FLS) are activated before the late biosynthetic genes (DFR, ANR) by the basic-Helix-Loop-Helix (bHLH) and R2R3-type MYB families of transcription factors (Pelletier et al., 1997). Similar activation patterns are observed in other dicotyledonous plants. A number of transcription factors regulating mostly the flavonoid/anthocyanin or lignin branches have been detected in many plant species, including legumes (Davies and Schwinn, 2003; Zhang et al., 2003; Yoshida et al., 2010; Zhao and Dixon, 2011).

The phenylproanoid pathway, especially the isoflavonoid branch is well characterized in soybean (Graham et al., 2008). However, the information about this important pathway in common bean is fragmentary and needs to be expanded to facilitate selection of lines with increased levels of these beneficial compounds. We initiated isolation and mapping genes coding for structural and regulatory proteins of this pathway. Only few genes (PAL1, CHS, CHI, CAD, and several PER) were characterized and their map positions identified before the initiation of this study.

Whole genome sequences are available for both soybean and common bean. The recent release of the complete draft of the soybean (cultivar Williams 82) genome sequence (v.1.0 in 2010) gives new insights into genome organization of this ancient paleopolyploid (Schmutz et al., 2010). The size of the genome is approximately 975 Mb, with over 46,000 genes captured in 20 chromosomes. As result of at least two rounds of polyploidization [~13 million years ago (MYA) and ~59 MYA] the soybean genome contains redundancy and gene duplications (Schmutz et al., 2010). The majority of low copy sequences are present in more than two copies [including numerous genes coding for enzymes of phenylpropanoid pathway (>100 PER, 54 LAC, 84 OMT, 214 UGT)] and a significant portion of the genome contains repetitive sequences. The early release of the common bean (Andean landrace G19833) genome sequence was in August 2012. The size of the common bean genome is approximately half of the size of the soybean genome (521.1 Mb), organized into 11 chromosomes with 27,197 loci containing 31,638 protein-coding transcripts (Phytozome, 13 Nov 2012). The availability of the genome sequences allows the organization of the individual genomes to be studied, as well as allowing for comparison of the two genomes at the nucleotide level. In general, for any gene/sequence in common bean, two corresponding homologous genes/sequences could potentially be found in soybean.

Moreover, Galeano et al. (2009) and McClean et al. (2010) showed that the two genomes, which were compared before the release of the common bean genome sequence (August 2012), share significant synteny. In general, regions homologous to regions in two soybean chromosomes were found for all 11 common bean chromosomes, with a minor marker rearrangement and/or sequence orientation. For example, three regions on the common bean chromosome Pv1 are syntenic to the regions of six soybean chromosomes: top (region between markers g1795 and g822) with soybean chromosomes Gm14 and Gm17, middle (region between markers g2490 and g1404) with soybean chromosomes Gm03 and Gm19, and bottom (region between markers g1224 and g2132) with soybean chromosomes Gm11 and Gm18 (McClean et al., 2010).

The objectives of the present work were to isolate genes coding for enzymes of phenylpropanoid pathway in common bean, determine in silico their genomic locations in common bean and soybean and analyze sequences of the 4CL gene family in two common bean genomes. Using genomic information from the other plant species, we were able to increase the information about the structural and regulatory genes that control the synthesis of beneficial phenylpropanoid compounds in common bean. In addition, the work describes the development of in silico maps, and compares genomic regions containing genes coding for enzymes of the phenylpropanoid pathway in common bean and soybean so that the selection and/or molecular manipulation can be done in the future to increase their levels in these crops.

Materials and methods

Isolation of phenylpropanoid pathway genes

Cloning phenylpropanoid pathway gene fragments

Plant material. Mature seeds of white (cultivar OAC Rex) or colored common beans were surface-sterilized by sodium hypochlorite (2.5% commercial bleach) with a drop of Tween 20 and grown on basal Murashige and Skoog (MS) media in Magenta tissue culture containers under low light. Seven day-old seedlings were washed, frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80°C until they were used.

Sequence selection and design of gene-based primers. Databases were searched for phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences from the common bean or other plant species. The sequences were aligned in ClustalW at EBI (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/) and PCR primers were designed to amplify conserved regions using the Primer3 program (Rozen and Skaletsky, 2000), which were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, ON, Canada). The majority of the primers were: 18–24 base pairs long, selected to have a GC content of 40–60% with fewer than four contiguous identical bases and melting temperatures between 55 and 65°C. The gene-based primers were used with total common bean cDNA or genomic DNA in PCRs to amplify fragments of a number of genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway in common bean.

Extraction and amplification of nucleic acids. Total RNA was extracted from the 7-day-old common bean seedlings using the Trizol™ Reagent (Invitrogen Inc., Burlington, ON, Canada). The RT-PCR was performed with the RETROscript® first strand synthesis kit (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA) according to manufacturer's instruction. PCR amplification was performed in a total volume of 20 μl containing 1x PCR buffer (supplied with enzyme), 3 mM MgCl2 (supplied with enzyme), 0.5 mM each of dNTPs (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences Corp., Piscataway, NJ, USA), 1.6 U Taq DNA Polymerase (Invitrogen), 5 μM each forward and reverse primers, and 0.5 μl of common bean RT reaction. The reaction mixture was amplified with a Techne Touchgene Gradient Thermal Cycler (Kracheler Scientific, Albany, NY, USA). The amplification program consisted of an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at gradient range 55–65°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min and finished by final extension at 72°C for 7 min.

Genomic DNA was isolated from the first trifoliate leaf from the white (or colored) common bean in 2% (w/v) CTAB buffer (Doyle and Doyle, 1990). The STS PCR was as for RT-PCR except that 25 ng of common bean genomic DNA was used as template. The reaction mixture was amplified with a PTC-100™ Programmable Thermal Controller (MJ Research Inc., Watertown, MA, USA). The amplification program consisted of an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 30 s, annealing at 55–60°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min and finished by final extension at 72°C for 7 min.

The RT-PCR and STS PCR products were run on a 1% (w/v) agarose gel in 1x modified TAE buffer (Millipore Corporation, Billerica, MA, USA) for 3 h at 80 V, stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under UV light. The fragments were excised from the gel, purified with Montage DNA Gel extraction kit (Millipore) and cloned using a TOPO™ TA cloning kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Plasmid DNA was extracted with QIAprep® Miniprep kit (Qiagen, Mississuaga, ON, Canada) and used as template for cycle sequencing using the CEQ™ 2000XL DNA Analysis System (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA, USA). Sequences were compared to the existing sequences from common bean or other plant species to ensure that the target genes were cloned using BLAST default parameters with a cut off value of 1E−10 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). Sequences were verified and submitted to GenBank under accession numbers CW652092 to CW652106 (EST) and CV670734 to CV670763 (GSS).

Cloning TT2 transcription factor fragments

RNA was extracted from 1–1.5 cm whole, immature siliques of cranberry-like Witrood common bean using the Qiagen RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) as per manufacturer's instructions with the following two modifications. Ambion RNA Isolation Aid (Applied Biosystems, Streetsville, Canada) was included in the Qiashredder step in order to increase RNA yield and the use of Ambion DNA-free Turbo DNase (Applied Biosystems) optimized the removal of contaminating DNA. The absence of contaminating DNA (less than 10 copies per sample) was confirmed by real-time PCR analysis of the RNA samples with primers for the actin gene. Synthesis of cDNA from the RNA samples was carried out according to manufacture's instructions for Ambion's RETROscript Reverse Transcription for RT-PCR (Applied Biosystems). Successful reverse transcription reactions were confirmed for all samples by post-transcription real-time PCR analysis of the cDNA for the actin gene sequence. Standard PCR was done using cDNA as template. Annealing temp was 54.7°C with forward primer 5′-TCTTCTCACATCAACACAAAC-3′ and reverse primer 5′-CATACTAGAAGAATTGGAATG-3′. PCR fragments were excised from the agarose gel, cloned into TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced (Genomics Facility-Advanced Analysis Centre, University of Guelph, Guelph, ON, Canada).

Isolation of selected set of phenylproanoid pathway genes

The common bean BAC library (constructed from HindIII digested and size selected landrace G19833 genomic DNA), obtained from the Clemson University Genomics Institute (CUGI, http://www.genome.clemson.edu/) was screened with DIG-labeled probes of six phenylproanoid pathway genes (CHS-A-Z, CHS-B-Z, DFR-Z, Myb15-Z, PAL2-Z, and PAL3-Z) amplified from cloned genomic DNA. The hybridization probes were synthesized using a digoxygenin (DIG) PCR Labeling kit (Roche Diagnostics Canada, Laval, QC, Canada) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Membranes [prepared by CUGI (containing 55,296 BAC clones of common bean landrace G19833 genomic DNA)] were screened by Southern hybridization with the DIG labelled probes. The identities of the BAC clones to which the probes strongly hybridized were identified on the bases of the membrane positions and patterns of the hybridization spots seen in the images. BAC clones strongly hybridized with the probes were obtained from the CUGI and plasmid DNA was extracted using plasmid extraction kit (Qiagen). The presence of probe sequences was verified by PCR amplification using gene-specific primers and the PCRs were compared to the original genomic PCR bands. One clone per gene with the appropriate size was selected for sequencing. Escherichia coli cells carrying individual BAC clones were grown on LB plates supplemented with 12.5 μg/ml of chloramphenicol at 37°C. For each BAC clone, one colony was picked and cultured in 2 ml LB supplemented with 12.5 μg/ml chloramphenicol. Approximately 10–15 μg of DNA from each clone was used for 454 next generation sequencing at the National Research Centre Council (Saskatoon, SK, Canada). Sequence reads were trimmed for contamination [bacterial (E. coli) genomic DNA, BAC clone backbone (pBeloBAC11) and vectors] in Univec database using CLC Genomics Workbench (http://www.clcbio.com) and assembled using the CLC Genomics Workbench reference assembly algorithm and genome sequence of common bean (http://www.Phytozome.org) as a reference. The consensus sequence was analyzed for the presence of coding regions with GENSCAN (http://genes.mit.edu/GENSCAN.html) and FGENESH (http://www.softberry.com/) using Medicago truncatula and Arabidopsis, respectively as the model organisms. Their putative functions were determined by comparing the coding regions to known genes at the GenBank.

Isolation of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) paralogs

Growing plants and sample collection. Seeds from common bean cultivar OAC Rex were grown in the greenhouse at 25/22°C for 16 h photoperiod with a light intensity of 150 μol m−2 s−2. The immature seeds (1–3 mm) were collected from green pods and immediately flash frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80°C until extraction of total RNA.

Cloning DFR2 and DFR3. Sequence information for DFR-Z gene obtained from the G19855 BAC clone PV-GBa 0072I22 (CUGI) was used to isolate two DFR paralogous cDNAs. Total RNA was extracted from immature seeds using RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) and treated with DNase (Ambion). The cDNA was amplified with 1 μg of DNase treated RNA with qScript ™ cDNA supermix (Quanta Biosciences, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) and used as a template in all PCR reactions. Initial PCR was performed with degenerate primers (forward- 5′-ATCGGRTCRTGGCTTGTYATG-3′ and reverse- 5′-GCTYCWGTRWACATRTCYTCYAAGSTGTAYTTRAA-3′) de-signed from the highly conserved sequences of DFR proteins from several closely related plant species. The PCR program was set up with an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 2 min followed by 34 cycles of 95°C (45 s)/58°C (45 s)/72°C (1 min) and a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. The cDNA fragments were cloned into TOPO vector (Invitrogen) and sequenced. The preliminary analysis revealed two similar sequences representing two different common bean DFR paralogous genes (named DFR2 and DFR3). The 5′ and 3′ sequences were obtained by 5′ and 3′ Rapid Amplification of cDNA (RACE; Clontech, Mountain View, CA, USA). For the first round amplification of DFR2 and DFR3 upstream and downstream sequences, PCR was performed with DFR2 reverse primer, 5′-ACCAGGCAGCTCCACCAAATGCTTCACCTT-3′ and forward primer 5′-ACCTCTTGTTGTTGGTCCCTTTCTCATGCCAACAATGCC-3′, DFR3 reverse primer, 5′-TGCACCTGGAAGTTCCACCAAATGCTTCACCTTCTTCAT-3′ and DFR3 forward primer 5′-ACCTCTTGTTGTTGGTCCCTTTCTCATGCCTACAATGCCA-3′ with an initial denaturation step of 95°C for 1 min followed by 32 cycles of 95°C (30 s)/68°C (1 min) followed by a cycle of 68°C (1 min)/70°C (10 min) and a final extension step of 72°C for 10 min. The second round nested PCR was performed with DFR2 reverse primer, 5′-TCGAACGGTGTAGCCACGCTCGAGGA-3′ and forward primer 5′-CCTAATCACTGCCCTTTCGCCCATCACAGGAAATGAGG 3′, DFR3 reverse primer, 5′ TCGAACGGTGTAGCCACGCTCCATTAGCC-3′ and DFR3 forward primer 5′- CACTGCTCTTTCACTCATCACAGGAAATGAAGGGCATTACC-3′ with an initial denaturation temperature of 95°C for 2 min followed by 32 cycles of 95°C (45 s)/64°C (45 s)/72°C (45 s) followed by a final extension step at 72°C for 10 min. The amplified fragments were cloned into TOPO vector and sequenced. Finally, the coding sequences of DFR2 and DFR3 were amplified with DFR2 forward primer, 5′-ATGGGTTCAGTGTCTGAAACTG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-TAGTTCTGAATGATGCCATTCATG-3′; DFR3 forward primer, 5′-ATGGGTTCAACTTCCGAATCC-3′ and reverse primer, 5′-CTATTTGTGCATGGTGCCATTAAC-3′.

Development and comparison of common bean and soybean sequence maps

Sequence collection used to compare common bean and soybean genomes

Sequences used to develop and compare common bean and soybean in silico maps are listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Phenylpropanoid pathway gene and marker sequences used in BLAST analyses.

| Sequence | Number | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Phenylpropanoid pathway genes | 200 | GenBank |

| Cloned common bean phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences—published | 35 | GenBank |

| Cloned common bean phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences—not published | 11 | University of Guelph |

| Common bean seed coat color gene-based markers | 10 | McClean et al., 2002/LISa |

| Soybean seed coat color gene-based markers | 12 | Yang et al., 2010/GenBank |

| Common bean “g” markers | 300 | LIS |

| Common bean SSRs | 60 | LIS/PhaseolusGenes |

| Soybean SSRs | 10 | SoyBase |

| Total | 638 |

Legume information system (http://www.comparative-legumes.org/).

Phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences. Literature and databases were searched for phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences from common bean, soybean or other plant species. The EC numbers of all known phenylpropanoid biosynthesis enzymes in soybean were recovered from the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, http://www.genome.jp/kegg/) pathway database, the MetaCyc database (MetaCyc.org) of metabolic pathways and enzymes and the BioCyc (biocyc.org) collection of pathway/genome databases.

Molecular marker sequences. Two types of molecular markers were used: common bean gene-specific [g (whole genome gene-based; McConnell et al., 2010)] and random RAPD, STS and simple sequence repeats (SSRs). Marker sequences were retrieved from the Legume Information System (LIS, http://www.comparative-legumes.org/) and/or PhaseolusGenes database (http://phaseolusgenes.bioinformatics.ucdavis.edu/) using the default settings.

Common bean g markers. The list of the g markers (matrix) shared between common bean and soybean was obtained at the LIS with the maps and comparison point where common bean PvMcCleanNDSU2007 map containing g markers was compared with soybean Gm JGI 8X Sequence Assembly at LIS (http://cmap.comparative-legumes.org/). In this work 300 g marker sequences were used. In some instances, only primer sequences were available.

Markers associated with seed coat color gene. Sequences of common bean markers associated with the seed color genes (Erdmann et al., 2002; McClean et al., 2002) were retrieved from the LIS. Sequences of soybean seed coat color gene-based markers were from Yang et al. (2010).

SSR markers. Common bean SSRs were used to fill gaps in positioning markers associated with the seed color genes on sequence maps. Only those shared by both, soybean and common bean were mapped in silico. Initially, the positions of the common bean SSR markers in the soybean genome were extracted from the LIS (McClean et al., 2010) and then updated with the soybean v.1.0 release. In soybean, sequences of SSRs flanking the markers associated with the seed coat color genes (Yang et al., 2010) were retrieved from the SoyBase/GenBank. Soybean SSRs flanking seed coat color genes reported by Yang et al. (2010) were also used in in silico mapping.

Development and comparison of phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequence-based maps in common bean and soybean

Common bean and soybean phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequence-based maps. Available nucleotide sequences (genes and markers) were BLASTed against soybean (v.1.0) and common bean (early release v.1.0) genomes at Phytozome (soybean at http://www.phytozome.net/soybean.php and common bean at http://www.phytozome.net/commonbean_er.php) using default parameters. The significance threshold E-value was set at E−30 and 150 bp minimum sequence length alignments with query sequences. In soybean, the top two hits on two different chromosomes were selected and labeled as 1 (copy 1 for the top hit) and 2 (copy 2 for the second hit). Where the top hit was a cluster of genes (CHS), several sequences were selected and the first was labeled as 1-a, second as 1-b, etc. The name of phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences consisted of enzyme/gene abbreviation and accession number. Sequence positions on chromosomes were indicated by the first nucleotide (nt) on the physical map (Phytozome).

Common bean-soybean sequence-based comparative map. The current map was developed in silico based on the McClean et al. (2010) common bean-soybean comparative map. All sequences shared by common bean and soybean are indicated. Synteny blocks were defined by the presence of three or more sequence features shared by the common bean and soybean genomes. The orientation of a marker/gene sequence on a chromosome was indicated by an up (↑, reverse)/down (↓, forward) arrow.

Use of common bean and soybean whole genome sequences

Sequence-based analysis of a gene family coding for 4-coumarate:CoA-ligase (4CL) enzyme of general phenylpropanoid pathway in common bean and soybean

Using soybean 4CL4 gene (Accession X69955) as a query, Phytozome was searched for homologous proteins from common bean and soybean. Genomic and protein sequences were retrieved for both species. Translations of genomic sequences into amino acids were checked using FGENESH with the Medicago gene model and/or ExPASy (http://web.expasy.org/translate/) at the Swiss Institute of Bioinformatics (SIB). Amino acids and DNA sequence alignments and constructions of phylogenetic trees were done in CLC Genomics Workbench 3 using a Neighbor Joining (NJ) algorithm. The accuracy of alignments was confirmed with ClustalW at EBI and edited manually. Twenty-one common bean and soybean 4CL sequences selected based on the similarity to four published soybean 4CLs were re-analyzed. Conserved domains of the selected 4CL proteins were analyzed at the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/bwrpsb/bwrpsb.cgi) (Marchler-Bauer et al., 2011).

Sequence polymorphism in common bean 4CL genes

Eight common bean 4CL genes were selected for polymorphism analysis and marker development. Reference common bean (Andean landrace G19833) 4CL sequences were BLASTed against OAC Rex (Mesoamerican) genome assembly in CLC Genomics Workbench. OAC Rex scaffold and contig segments containing 4CL genes were then compared with the corresponding G19833 sequences in ClustalW at EBI. The alignments were adjusted manually and searched for sequence polymorphism (SNPs and indels). OAC Rex 4CL genes that were verified were submitted to the GenBank under accession numbers KF303286 (4CL-1) to KF303293 (4CL-8).

Sequencing of Mesoamerican common bean cultivar OAC Rex is one of the major objectives of an ongoing multi institutional (University of Guelph, University of Windsor, University of Western Ontario and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada) Phaseolus genomics project (www.beangenomics.ca). Two mate pair libraries were prepared (50 bp read length) and sequenced using the Illumina HiSeq platform at the Center for Applied Genomics (Toronto, ON, Canada)]. Scaffolding and contig assembly were performed using SOAP2 de novo and ABYSS (Perry et al., 2013; DiNatale et al., unpublished). Currently, the OAC Rex genome is assembled into megabase contigs; pseudo-chromosome builds have been initiated and public release is expected to be in 2014.

Results

Isolation of phenylpropanoid pathway genes in common bean

Cloning phenylpropanoid pathway gene fragments

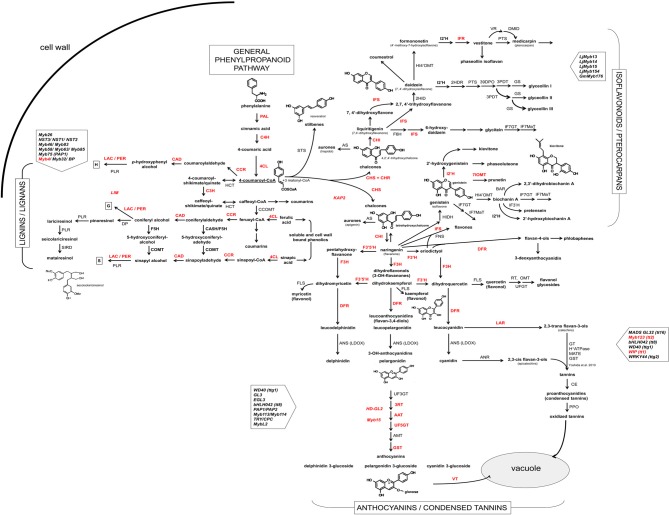

In this study, we amplified and sequenced fragments of 46 genes coding for structural and/or regulatory proteins of phenylpropanoid pathway in common bean (designated with red lettering in Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Scheme of the phenylpropanoid pathway in common bean and soybean. Enzymes and transcription factors of the phenylpropanoid pathway [based on biochemical and genetic studies of several plant species and (KEGG Pathway database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/pathway.html)] are presented in uppercase letters: PAL, phenylalanine ammonia lyase (EC:4.3.1.24); C4H, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase (EC:1.14.13.11); 4CL, 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (EC:6.2.1.12); C3H, 4-coumarate 3-hydroxylase (EC:1.14.13.-); COMT, caffeate O-methyltransferase (EC:2.1.1.68); F5H, ferulic acid 5-hydroxylase (EC:1.14.-.-); CCoOMT, caffeoyl CoA O-methyltransferase (EC:2.1.1.104); CCR, cinnamoyl CoA-reductase (EC:1.2.1.44); HCT, hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA: shikimate/guinate hydroxycinnamoyltransferase (EC:2.3.1.133); CAD, cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (EC:1.1.1.195); LAC, laccase (EC:1.10.3.2); PER, lignin peroxydase (EC:1.11.1.7); PLR, pinoresinol/lariciresinol reductase; DP, dirigent protein; STS, stilbene synthase; CHS, chalcone synthase (EC:2.3.1.74); CHI, chalcone isomerase (EC:5.5.1.6); FNS, flavone synthase (EC:1.14.11.22); F3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase (EC:1.14.11.9); F3′H, flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (EC:1.14.13.21); F3′5′H, flavonoid 3′5′-hydroxylase (EC:1.14.13.88); FLS, flavonol synthase (EC:1.14.11.23); DFR, dihydroflavanol 4-reductase (EC:1.1.1.219); ANS (LDOX), anthocyanidin synthase (EC:1.14.11.19); UF3GT, UDP glucose flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase (EC:2.4.1.115); 3RT, anthocyanidin-3-glucoside rhamnosyl transferase (EC:2.4.1.-); AAT, anthocyanin 5-aromatic acyltransferase (EC:2.3.1.153); AMT, anthocyanin methyltransferase; GST, glutathione S-transferase (EC:2.5.1.18); VT, vacuolar transporter; LAR, leucoanthocyanidin reductase (EC:1.17.1.3); ANR, anthocyanidin 4-reductase (1.3.1.77); GT, glucosyltransferase; MATE, multidrug and toxic compound extrusion; CE, condensed enzymes; PPO, polyphenol oxidase (EC:1.10.3.1); CHR, chalcone reductase (EC:1.1.1.-); IFS, 2-hydroxyisoflavanone synthase (EC:1.14.13.86); HIDH, 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase (EC:4.2.1.105); 7IOMT, isoflavone 7-O-methyltransferase (EC:2.1.1.150); I2'H, isoflavone 2′-hydroxylase (EC:1.14.13.89); IFR, isoflavanone reductase (EC:1.3.1.45); F6H, flavonoid 6-hydroxylase (EC:1.14.13.-); HI4′OMT, isoflavone 4-O-methyltransferase (EC:2.1.1.46); IF7MaT, isoflavone 7-O-methyltransferase (EC:2.3.1.115); VR, vestitone reductase (EC:1.1.1.-); DMID, dihydroxy-methoxy-isoflavanol dehydratase; G4DT, pterocarpan 4-dimethylallyltransferase; PTS, pterocarpan synthase (EC:1.1.1.246); KAP2, H-box-binding TF (CHS); Myb4, R2R3-type Myb TF (PAL); LIM1, TF LIM1 domain protein (lignin); HD-GL2, TF homeodomain protein GL2 like 1/ANL2; Myb15, R2R3-type Myb TF; WIP, TF zinc finger WIP (TT1); TGA1, basic domain/leucine zipper TF. Common bean genes cloned in this study are shown in bold red.

Structural gene fragments.

General phenylpropanoid pathway. Six cDNA fragments for structural genes coding for enzymes of the general phenylpropanoid pathway (PAL, C4H, and 4CL) were cloned and sequenced in common bean (Table 2). In all cases significant BLAST scores (≥E−10) were detected. The PCR fragments ranged in sizes from 300 bp (PAL2) to 550 bp (4CL1). Gene fragments for two 4-coumarate CoA ligase (4CL1 and 4CL2) were cloned in this study using G. max 4CL1 (Accession AF279267) and 4CL2 (Accession AF002259), respectively (Lindermayr et al., 2002) as source sequences (Table 2). Additional copies of 4CL gene need to be isolated in the future. In addition, complete PAL2 (PAL2-Z) and PAL3 (PAL3-Z) gene sequences were determined (Table 3).

Table 2.

Cloned phenylpropanoid pathway gene fragments in common bean.

| Enzyme | Gene | PCR primers | Common bean clone | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Source | Position (bp) | Sequence (5′-3′) | Size (bp) | BLASTn E-value | GenBank accession | ||

| GENERAL PHENYLPROPANOID PATHWAY | |||||||

| Phenylalanine ammonia lyase | PAL1 | P. vulgaris | 1060–1628 | GGATCTGCTGAAAGTGGTTGACA | 486 | 0.0 | CV670758 |

| M11939 | TCCGGCTTTCCATGTAGATTTG | 506 | CV670759 | ||||

| PAL2 | P. vulgaris | 1612–3729 | CCCACCGCCGTACCAAACAA | 399 | 5E-24 | CV670734 | |

| P19142 | GCAACTCAAAGAACTCAGAACCAA | ||||||

| PAL3 | P. vulgaris | 630–1373 | GTGCAAACTCCAACAGGCAAA | 298 | 1E-49 | CV670735 | |

| P19143 | GCAGCAATGTAGGACAGAGGAA | ||||||

| Cinnamate 4-hydroxylase | C4H | P. vulgaris | 716–1074 | GTTCATTCAGGCCACGAGGTT | 359 | 0.0 | CV670736 |

| Y09447 | CCAACTCAGCTATTGCCCATT | ||||||

| 4-coumarate: CoA ligase | 4CL1 | G. max | 903–1447 | GCGTTGGTTAAGAGCGGAGAGA | 545 | 0.0 | CV670737 |

| AF279267 | CCTACAACGGCAGCATCAGAAA | ||||||

| 4CL2 | G. max | 870–1271 | CTCCTTGCTTGCTCTCATTCA | 402 | 5E-64 | CV670738 | |

| AF002259 | CCTTTCATAATCTGGTCGCCTCT | ||||||

| LIGNIN/LIGNAN BRANCH | |||||||

| Cinnamoyl CoA reductase | CCR | G. max | 129–575 | CTGGTGGCTTCATCGCCTCT | 338 | E-130 | CV670739 |

| BI426824 | CAGCCTTCCCATAGCAATACCAA | ||||||

| Cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase | CAD1 | M. sativa | 855–1160 | GACACAATATCTGCTGCTCATT | 306 | 1E-54 | CV670740 |

| L46856 | GGCCACATCAATCACAAACCGAT | ||||||

| 4-coumarate-3 hydroxylase | C3H | S. indicum | 325–871 | GACTTGATTTGGTCCGATTATGG | 386 | 2E-97 | CV670754 |

| AY065995 | CGATAACGGTGTCATCACTGAG | 468 | E-147 | CV670755 | |||

| Caffeate O-methyltransferase | COMT | M. sativa | 388–779 | GATGGTGTATCCATTTCTGCTCTT | 401 | 6E-98 | CV670741 |

| M63853 | CCACCAACATGCTCAACTCCT | ||||||

| Ferulate 5-hydroxylase | F5H | G. max | 67–534 | AGCGGGTCCAACAAGAGCTG | 468 | E-135 | CV670742 |

| BM527849 | CGAACACGTCACCCATGTCC | ||||||

| Laccase | LAC | G. max | 2937–3980 | CCACTCCCTGCTTACAACGACA | 489 | E-142 | CV670743 |

| AF527604 | CCCGAAACCCTCTGCAACAA | ||||||

| Lignin peroxidase (PER) | FBP1 | P. vulgaris | 224–982 | CGATAGTGAGCGAGCAAGAAG | 513 | 9E-63 | CW652094 |

| AF149277 | CCAAAGTAGCCAATCCAGCAGA | ||||||

| FBP4 | P. vulgaris | 133–827 | TGACGGTTCTGTTCTCATTTCC | 496 | 0.0 | CW652095 | |

| AF149279 | TGCCCATCTTCACCATAGCATTT | 495 | 0.0 | CW652096 | |||

| FLAVONOID/ANTHOCYANIN BRANCH | |||||||

| Chalcone synthase | CHS | P. vulgaris | 194–971 | GTGAGCACATGACCGACCTCA | 585 | 0.0 | CV670744 |

| X06411 | CCAGGGTGTGCAATCCAGAA | ||||||

| Chalcone isomerase | CHI | P. vulgaris | 950–1826 | CGTCACTCGCCACCAAGTGGAA | 215 | E-176 | CV670745 |

| Z15046 | GCCTTTGGCTTCAGCATCACCAT | ||||||

| Chalcone reductase | CHR | G. max | 52–489 | TGCCTTTGAGGTTGGCTACAGA | 579 | 6E-55 | CW652099 |

| BU578179 | ACAGCAGGAGGGATGGTTGC | 465 | 2E-78 | CW652100 | |||

| Rhamnosyl transferase | 3RT | P. coccineus | 53–303 | TGGGTGTTGAGGGTTCATCG | 251 | 2E-79 | CV670748 |

| CA914524 | CACTCGCGCATTTATCCCTTG | ||||||

| Flavanone 3-hydroxylase | F3H | M. sativa | 2119–2856 | GCAAGAAGATTGTGGAGGCTT | 590 | E-119 | CW652103 |

| X78994 | CCTGGATCTGTGTGGCGTTT | ||||||

| Flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase | F3′H | G. max | 242–1082 | GGCTTCGTCGATGTCGTGGT | 486 | E-128 | CV670760 |

| AB061212 | GGTGGGCCAAGTCCTCTTCTTT | 508 | E-139 | CV670761 | |||

| Anthocyanin 5-O-glucosyltransferase | UF5GT | P. coccineus | 6–340 | CCAAGGCGTAATCCAAGTCCA | 221 | E-103 | CV670749 |

| CA914529 | GGGTTTCAGGCTCTCCATGA | ||||||

| Anthocyanidin reductase | ANR | M. truncatula | 369–778 | GTGTTGAAAGCATGTGTAAGAGCA | 576 | 5E-80 | CW652104 |

| AY184243 | GCCCGACAAATATCCTCGACAT | 590 | 6E-80 | CW652105 | |||

| Anthocyanin 5-acyltransferase | AAT | P. coccineus | 166–572 | GGGTGTCTCTTCACCACTCCA | 407 | 0.0 | CV670746 |

| CA900148 | GAAATGGCGGCGAAAGTGTT | ||||||

| Glutathione S-transferase | GST1 | P. acutifolius | 202–802 | GCTTCTCAAATACAACCCAGTTCA | 487 | 2E-85 | CW652097 |

| GAAACGCAATGGTAACTAACAGCA | 502 | 0.0 | CW652098 | ||||

| GST2 | AY220095 | 509 | E-179 | CV670756 | |||

| 498 | 0.0 | CV670757 | |||||

| Vacuolar transporter | VT | P. coccineus | 3–455 | TGGAAGTGGATGGCAAGCAG | 451 | 0.0 | CV670747 |

| CA907034 | TCACATACTTGTGCTGACAGTGAA | ||||||

| ISOFLAVONOID BRANCH | |||||||

| 2-hydroxyisoflavanone synthase | IFS | G. max | 573–1325 | GGCGAGGCTGAGGAGATCAGA | 507 | E-139 | CV670762 |

| AF195818 | CTGGGAGTGGTGGGTGCATT | 506 | E-154 | CV670763 | |||

| Isoflavanone reductase | IFR | M. sativa | 906–1581 | GGAAGACACATAGTTTGGGCAAGT | 268 | E-139 | CV670750 |

| U17436 | CGGTAAAGGCGTGGCAACAA | ||||||

| 7-O-methyltransferase | IOMT | M. sativa | 234–637 | GGTAACGTGCGGCGTCTCAT | 456 | 0.0 | CV670751 |

| AF000975 | GCAGTTGTTCCAGTTCCACCA | ||||||

| REGULATORY GENES | |||||||

| KAP-2 (CHS) | KAP2 | P. vulgaris | 504–1007 | GAAGGCACAAAGGAAGAGCAA | 504 | 0.0 | CV670752 |

| AF293344 | CCAGTGAGAAGTGGATAAGGGAA | ||||||

| Myb AtMyb4 (PAL) | Myb4 | P. coccineus | 92–406 | AAGATGGGAAGAGCTCCTTGTT | 544 | 4E-64 | CW652106 |

| CA902489 | ATCTCATTATCTGTTCGTCCTGGT | ||||||

| Homeodomain protein GL2 like1/ANL2 | HD | P. coccineus | 3–326 | GTCGGTGGAGACCGTGAACA | 324 | 8E-95 | CV670753 |

| CA902455 | CGAACCACCACCCTTGCCTA | ||||||

| ZINC finger WIP (TT1) | WIP | P. coccineus | 2–496 | GGGCCTCATTCACATGCAA | 534 | 4E-70 | CW652101 |

| CA902512 | CGTGGGTGGTCGATGTTGTT | ||||||

| LIM domain protein WLIM1 (lignin) | LIM | G. max | 27–569 | GGCATTTGCAGGAACAACTCAG | 458 | 0.0 | CW652092 |

| BU764417 | GCACTCTTCTCATGGTCACCTTC | 489 | 0.0 | CW652093 | |||

| Myb AtMYB15 | Myb15 | P. coccineus | 39–452 | GAGTGATGGCGTGCGGAGTA | 519 | E-162 | CW652102 |

| CA902486 | CCCAGCGTCTCATGCAGCTT | ||||||

Table 3.

G19833 BAC clones containing common bean phenylpropanoid pathway genes.

| BAC clone | Pv v.1.0 assembly (in silico chromosome position, nt) | Gene | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| PV-GBa 0005G03a | Chr2:3,691,740..3,830,946 | CHS-B-Zb | 1265 |

| PV-GBa 0083H05 | Chr1:14,526,848..14,805,105 | CHS-A-Z | 1700 |

| PV-GBa 0072I22 | Chr7:48,408,886..48,606,955 | DFR-Z | 2793 |

| PV-GBa 0043K12 | Chr7:13,377,553..13,576,830 | Myb15-Z | 1781 |

| PV-GBa 0079P22 | Chr7:36,990,886..37,135,402 | PAL2-Z | 3830 |

| PV-GBa 0061D18 | Chr8:59,298,741..59,462,821 | PAL3-Z | 2573 |

Clemson University Genomics Institute (CUGI, http://www.genome.clemson.edu/).

Copy number = 8.

Lignin/lignan branch. PCR fragments were amplified from common bean cDNA or genomic DNA with PCR primers designed on the basis of sequence information from related legume species (such as Medicago sativa) or very different plant species (including Sesamum indicum or Forsythia intermedia) for all of the major enzymes in this branch, including: cinnamoyl CoA reductase (CCR), cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase (CAD), 4-coumarate-3 hydroxylase (C3H), caffeate O-methyltransferase (COMT), ferulate 5-hydroxylase (F5H), laccase (LAC) and two peroxidases (PER). Significant BLAST scores with the expected gene sequences were detected for most of the cloned common bean sequences (Table 2). However, the sequences of the fragments amplified with the caffeic acid CoA 3-O-methyltransferase (CCOMT) and pinoresinol/lariciresinol reductase (PLR) primers did not have significant similarity with the authentic sequences according to their BLAST scores (data not shown). These genes will need to be isolated in future studies.

Flavonoid/anthocyanin branch. EST sequences from Phaseolus coccineus and P. acutifolius as well as sequences from other legumes were used to design primers for amplifying PCR fragments from common bean cDNA or genomic DNA templates of a number of enzymes in this important branch, including: chalcone synthase (CHS), chalcone isomerase (CHI), chalcone reductase (CHR), flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H), flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase (F3′H), anthocyanidin 4-reductase (ANR), anthocyanin 5-aromatic acyltransferase (AAT), anthocyanin rhamnosyl transferase (3RT), UDP-g1ucose:flavonoid 5-O-glucosyltransferase (UF5GT), glutathione S-transferase (GST), and vacuolar transporter (VT) (Table 2). In addition, the complete gene sequences were obtained for two common bean CHS (CHS-A-Z and CHS-B-Z) and DFR (DFR-Z) (Table 3). Three DFR paralogous genes were cloned and sequenced (white common bean cultivar OAC Rex). The predicted common bean DFR1 (DFR1-M) protein was similar to soybean DFR3 (61%), common bean DFR2 (DFR2-M) protein was similar to soybean DFR1 (87%) and common bean DFR3 (DFR3-M) protein was similar to soybean DFR2 (86%). Although a good coverage of this segment of the phenylpropanoid pathway in common bean was obtained in the current work, gene fragments for several enzymes including flavonol synthase (FLS), flavone synthase (FNS), flavonoid 3′5′-hydroxylase (F3′5′H), anthocyanidin synthase (ANS) and leucoanthocyanidin reductase (LAR) need to be isolated in the future. Attempts to amplify fragments of these genes with cDNA or genomic DNA templates failed (data not shown).

Isoflavonoid branch. Prior to this study, there was no sequence information in common bean for the genes coding for the enzymes of this branch of the phenylpropanoid pathway, except a P. coccineus EST corresponding to isoflavone reductase-like (IFR-l). Using this information and sequence information from the other legumes, fragments for three structural genes coding for 2-hydroxyisoflavanone synthase (IFS), isoflavanone reductase (IFR), and 7-O-methyltransferase (7IOMT) were isolated (Table 2). There is still a need to obtain sequences for genes coding for the remaining enzymes [including isoflavone 2′-hydroxylase (I2′H), vestitone reductase (VR) and dihydroxy-methoxy-isoflavanol dehydratase (DMID)] of this branch of the phenylpronaoid pathway in common bean.

Regulatory gene fragments. At the beginning of this study only two P. vulgaris gene sequences for regulatory genes of the phenylpropanoid pathway, KAP2 (Lindsay et al., 2002) and bZIP TGA1 (Tucker et al., 2002), were available. By utilizing P. coccineus ESTs and sequence information from a variety of plant species it was possible to design primers to amplify fragments of additional transcription factors from common bean cDNA and genomic DNA templates. Initially, 18 different transcription factor sequences were targeted. However, BLAST searches with the sequences of the fragments that were amplified indicated that only six genes encoding common bean transcription factors (Myb4, LIM, KAP-2, HD, WIP, and Myb15) were identified as putative (or possible) regulatory genes of this pathway (Table 2). In addition, the whole gene sequence was isolated for Myb15 (Table 3) and two gene fragments for TT2 transcription factor (similar to LjTT2 a, b, and c) were amplified and sequenced (data not shown).

Sequence-based comparative mapping of phenylpropanoid pathway genes in common bean and soybean

Common bean and soybean phenylpropanoid pathway gene-based sequence maps

We developed in silico phenylproanoid pathway gene sequence-based maps by mapping phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences to common bean and soybean chromosomes (Tables S1, S2). Over 600 gene and marker sequences were used in development of in silico maps. As expected, the majority of gene/marker sequences mapped to one chromosome in common bean but two chromosomes in soybean. This resulted in mapping approximately two times as many sequence features in soybean genome (1011) compared to common bean (507). The current in silico maps contain sequences of phenylpropanoid pathway genes (260 in common bean and 459 in soybean) and common bean and soybean marker sequences (seed coat color gene-based markers, g markers and SSRs).

Common bean sequence map. The common bean in silico sequence map contains 507 features on 11 chromosomes (Tables 4, S1), ranging from 25 (chromosomes Pv4, Pv10, and Pv11) to 83 (chromosome Pv2).

Table 4.

Characteristics of common bean phenylpropanoid pathway gene-based sequence map.

| Chromosome | Total features | Position (nucleotide number) | Coverage (bp) | Size (bp)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | ||||

| Pv1 | 56 | 1,071,371 | 52,150,964 | 51,079,593 | 52,205,531 |

| Pv2 | 83 | 238,724 | 48,041,224 | 47,802,500 | 49,040,938 |

| Pv3 | 54 | 950,004 | 51,791,104 | 50,841,100 | 52,284,309 |

| Pv4 | 25 | 1,428,273 | 45,736,396 | 44,308,123 | 45,960,019 |

| Pv5 | 26 | 2,347,029 | 40,478,924 | 38,131,895 | 40,819,286 |

| Pv6 | 51 | 9,243,136 | 31,761,604 | 22,518,468 | 31,977,256 |

| Pv7 | 51 | 599,228 | 50,145,180 | 49,545,952 | 51,758,522 |

| Pv8 | 69 | 155,567 | 59,310,664 | 59,155,097 | 59,662,532 |

| Pv9 | 40 | 5,750,860 | 36,534,776 | 30,783,916 | 37,469,608 |

| Pv10 | 25 | 2,032,367 | 43,002,236 | 40,969,867 | 43,275,151 |

| Pv11 | 25 | 169,275 | 49,713,356 | 49,544,081 | 50,367,376 |

| Total | 507 | 514,820,528 | |||

Phytozome (www.phytozome.net/commonbean.php)—Accessed: February 13, 2013.

Soybean sequence map. The soybean in silico sequence map contains 1011 features on 20 chromosomes (Tables 5, S2), ranging from 31 (chromosomes Gm16) to 100 (chromosome Gm08).

Table 5.

Characteristics of soybean phenylpropanoid pathway gene-based sequence map.

| Chromosome | Total features | Position (nucleotide number) | Coverage (bp) | Size (bp)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Start | End | ||||

| Gm01 | 33 | 992,725 | 55,451,076 | 54,458,351 | 55,915,595 |

| Gm02 | 59 | 19,669 | 51,366,328 | 51,346,659 | 51,656,713 |

| Gm03 | 33 | 1,606,119 | 46,881,240 | 45,275,121 | 47,781,076 |

| Gm04 | 35 | 189,069 | 48,284,344 | 48,095,275 | 49,243,852 |

| Gm05 | 46 | 242,329 | 41,919,824 | 41,677,495 | 41,936,504 |

| Gm06 | 52 | 229,125 | 50,276,300 | 50,047,175 | 50,722,821 |

| Gm07 | 54 | 305,682 | 42,294,768 | 41,989,086 | 44,683,157 |

| Gm08 | 100 | 329,749 | 46,669,032 | 46,339,283 | 46,995,532 |

| Gm09 | 65 | 349,423 | 45,986,536 | 45,637,113 | 46,843,750 |

| Gm10 | 47 | 648,359 | 50,652,976 | 50,004,617 | 50,969,635 |

| Gm11 | 52 | 305,133 | 39,002,116 | 38,696,983 | 39,172,790 |

| Gm12 | 34 | 136,883 | 39,748,568 | 39,611,685 | 40,113,140 |

| Gm13 | 74 | 798,836 | 44,256,628 | 43,457,792 | 44,408,971 |

| Gm14 | 48 | 402,041 | 48,273,860 | 47,871,819 | 49,711,204 |

| Gm15 | 55 | 190,218 | 50,089,752 | 49,899,534 | 50,939,160 |

| Gm16 | 31 | 493,954 | 37,180,576 | 36,686,622 | 37,397,385 |

| Gm17 | 44 | 542,091 | 40,950,824 | 40,408,733 | 41,906,774 |

| Gm18 | 71 | 31,200 | 62,243,640 | 62,212,440 | 62,308,140 |

| Gm19 | 41 | 740,074 | 50,265,556 | 49,525,482 | 50,589,441 |

| Gm20 | 37 | 1,123,688 | 46,134,760 | 45,011,072 | 46,773,167 |

| Total | 1,011 | 950,068,807 | |||

Phytozome (www.phytozome.net/soybean.php)—Accessed: February, 2013.

Sequence-based comparative mapping of phenylpropanoid pathway genes in common bean and soybean

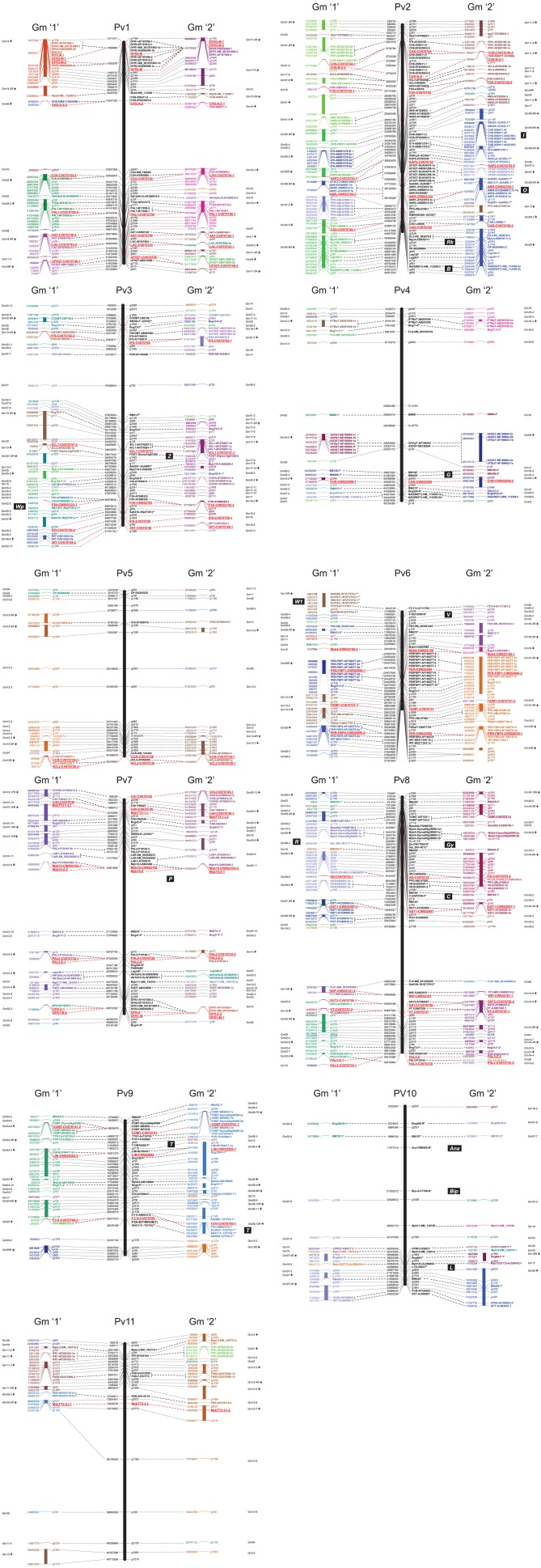

The comparative map (Figure 2) was developed in silico by aligning sections of related soybean chromosomes to common bean chromosomes, based on the sequence positions of common bean g markers and phenylpropanoid pathway genes that were shared by the two species. The correspondence between common bean and soybean chromosomes agrees to a large extent with previously reported patterns of shared synteny between the two species (McClean et al., 2010; Galeano et al., 2011). Additional sequence features/regions shared between the two genomes were also identified. In particular, we focussed on identifying the positions of many of the phenylpropanoid pathway genes in common bean and their syntenic regions on corresponding soybean chromosome blocks. The positions of dihydroflavonol 4-reductase (DFR) on common bean chromosome Pv1 between markers g1795 and g1645 and chalcone isomerse (CHI_INT3) between markers g503 and g2298 were reported previously (McClean et al., 2010) but their corresponding locations in soybean genome were not identified. In addition, we in silico mapped the sequences of several common bean and/or soybean markers associated with seed coat color in both species (Figure 2). Also, several common bean seed coat color and pattern genes were in silico positioned on the common bean-soybean sequence-based comparative map according to their positions on the common bean genetic maps (McClean et al., 2002) and syntenic locations in the soybean genome (summarized in Table 6).

Figure 2.

Phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequence-based common bean-soybean comparative map. Marker and phenylpropanoid pathway gene names (abbreviated plus accession number) are shown on right of each chromosome. Feature position [bp, start nt shown (Phytozome)] is indicated on left of each chromosome. Syntenic fragments of soybean chromosomes (each in different color) are shown on left (copy “1”) and right (copy “2”) of common bean chromosome (black). Phenylpropanoid pathway gene fragments cloned in this study are shown in red, bold, and underlined. Tentative positions of seed coat color genes are shown in black blocks. Enzyme abbreviations: PAL, phenylalanine ammonia lyase; C4H, cinnamate 4-hydroxylase; 4CL, 4-coumarate:CoA ligase; C3H, 4-coumarate 3-hydroxylase; COMT, caffeate O-methyltransferase; F5H, ferulic acid 5-hydroxylase; CCoOMT, caffeoyl CoA O-methyltransferase; CCR, cinnamoyl CoA-reductase; HCT, hydroxycinnamoyl-CoA: shikimate/guinate hydroxycinnamoyltransferase; CAD, cinnamyl alcohol dehydrogenase; LAC, laccase; PER, lignin peroxydase; PLR, pinoresinol/lariciresinol reductase; DP, dirigent protein; STS, stilbene synthase; CHS, chalcone synthase; CHI, chalcone isomerase; FNS, flavone synthase; F3H, flavanone 3-hydroxylase; F3′H, flavonoid 3′-hydroxylase; F3′5′H, flavonoid 3′5′-hydroxylase; FLS, flavonol synthase; DFR, dihydroflavanol 4-reductase; ANS (LDOX), anthocyanidin synthase; UF3GT, UDP glucose flavonoid 3-O-glucosyltransferase; 3RT, anthocyanidin-3-glucoside rhamnosyl transferase; AAT, anthocyanin 5-aromatic acyltransferase; AMT, anthocyanin methyltransferase; GST, glutathione S-transferase; VT, vacuolar transporter; LAR, leucoanthocyanidin reductase; ANR, anthocyanidin 4-reductase; PPO, polyphenol oxidase; CHR, chalcone reductase; IFS, 2-hydroxyisoflavanone synthase; HIDH, 2-hydroxyisoflavanone dehydratase; 7IOMT, isoflavone 7-O-methyltransferase; I2′H, isoflavone 2′-hydroxylase; IFR, isoflavanone reductase; F6H, flavonoid 6-hydroxylase; HI4′OMT, isoflavone 4-O-methyltransferase; IF7MaT, isoflavone 7-O-methyltransferase; VR, vestitone reductase; DMID, dihydroxy-methoxy-isoflavanol dehydratase; G4DT, pterocarpan 4-dimethylallyltransferase; PTS, pterocarpan synthase.

Table 6.

Genome location of common bean seed coat color and pattern genes.

| Common bean | Soybean synteny | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Phenotype | Genome location | |||||

| Chromosome | Closest marker(s) | Nearest phenylpropanoid pathway gene(s) | |||||

| Color | P | Ground factor | Pv7 | g487-BM210 | Myb15-CW652102/PAL2-P19142-1 | Gm20/Gm13 | Gm10 |

| C | Complete color | Pv8 | C-OAP2700-Fa | HD-CV670753; VR-EU925557/GST1-AY220095 | Gm18 | Gm07 | |

| J (=L) | Mature color development | NA | NAb | NA | NA | NA | |

| G | Yellow brown | Pv4 | BM140-g2595 | A3OGT-BE190894/CHR-CW652099 | Gm09 | Gm16 | |

| B | Gray brown | Pv2 | g364-g656 | NAD(REF1)-NM_113359-2/- | Gm08 | Gm05 | |

| V | Violet | Pv6 | V-OD12800-Ra | F3′5′-AY117551/F6H-XM_003551443 | Gm18 | Gm13 W1-F3′5′H | |

| Rk | No color expression | Pv2 | g2540-g1194 | CAD-CV670740/MycA-EW678711/DP-BE806864 | Gm08 I—CHS, O—ANR | Gm05 | |

| Pattern | T | Totally colored | Pv9 | T-OM19400-Fa | COMT-CV670741; PTR-TC433083/LIM-BU764417 | Gm06 T-F3′H | Gm04 |

| Z (=D) | Zonal | Pv3 | g125-g1925 | 4CL1-AF279267-1; FOGT-Glyma13g01220/Myb176-FJ550209 | Gm17 Gm02-Wp-F3H | Gm13/Gm05 | |

| Bip | Bipunctata | Pv10 | Bip-OJ17700-Ra | Myb11-NM_116126/- | Gm03/Gm19 | Gm07 | |

| Ana | Anasazi | Pv10 | Ana-OM9200-Ra | – | Gm07 | Gm03 | |

| Gy | Greenish-yellow | Pv8 | Gy-OW17600-Ra | MybA-Glyma09g36990-1b/HD-CA902455 | Gm18 | Gm9 R | |

Markers associated with the seed coat color/pattern genes (McClean et al., 2002).

not available.

Pv1. We confirmed three large syntenic blocks identified previously (McClean et al., 2010; Galeano et al., 2011) between common bean chromosome Pv1 and six soybean chromosomes, including with: Gm14 (17 features)/Gm17 (12 features), Gm03 (17 features)/Gm19 (18 features), and Gm18 (12 features)/Gm11 (8 features). In addition, one to four sequences were shared between Pv1 and several (nine) soybean chromosomes (Figure 2). Eleven phenylpropanoid gene sequences mapped to the common bean chromosome Pv1, including eight cloned in this study (DFR2-M, DFR3-M, CHS-A-Z, C3H-CV670754, PAL1-CV670758, AAT-CV670746, LAC-CV670743, and UF5GT-CV670749, shown in red in Figure 2). DFR2 (sequence start 1,086,866 nt) and DFR3 (sequence start 1,093,579 nt), located in the first block, are syntenic to soybean DFR genes on chromosomes Gm14 and Gm17, respectively. C3H (33,062,004 nt) and PAL1 (44,150,744 nt) found on the second block were syntenic to soybean genes on chromosomes Gm03 and Gm19, respectively. The third syntenic block contains sequences of AAT (50,073,684 nt), LAC (50,563,496), and UF5GT (51,855,780). The first copy of these genes was found on syntenic soybean chromosome Gm18 (in reverse order) but the second copy of these genes was located on three separate chromosomes [syntenic Gm11 and two other chromosomes (Gm02 and Gm05, respectively)].

Pv2. This study confirmed the existence of two major syntenic blocks between common bean chromosome Pv2 and soybean chromosomes Gm01 (22 features)/Gm11 (22 features) and Gm05 (27 features)/Gm08 (43 features), that were identified previously (McClean et al., 2010; Galeano et al., 2011). In addition, one to 12 sequences were shared between Pv2 and eight soybean chromosomes (Figure 2). Twenty phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences were found on chromosome Pv2, six of them cloned in this study (CHS-CV670744, CHS-B-Z, F5H-CV670742, KAP2-CV670752, ANR-CW652104, and CAD-CV670740). A cluster containing four CHS genes was found on the common bean chromosome Pv2 (at 3,726,784 nt; 3,733,338 nt; 3,765,494 nt; 3,775,079 nt). The first gene was syntenic to soybean CHS7 on chromosome Gm01 and CHS8 on chromosome Gm11. The fifth common bean CHS gene was found on position 33,749,564 nt (sequence start) and was syntenic to a single soybean CHS on chromosome Gm05 (CHS2) but corresponds to a cluster of six CHS genes on chromosome Gm08. The locations of the seed coat color genes Rk and B that were mapped previously to the end of chromosome Pv2, are indicated (McClean et al., 2002). Interestingly, soybean seed coat color genes I [factor which inhibits pigment formation in the seed coat, associated with six CHS repeats (Tuteja et al., 2004)] and O [factor for dull brown seed coat color, may be associated with anthocyanin reductase (ANR, Yang et al., 2010)] were located on chromosome Gm08, which are syntenic to the regions of Pv2 chromosome containing common bean CHS and ANR, respectively.

Pv3. Blocks of soybean chromosomes Gm02 (16 sequence features) and Gm05 (eight features)/Gm17 (21 features) and Gm02/Gm16 (six features) were syntenic to common bean chromosome Pv3 (McClean et al., 2010; Galeano et al., 2011). In addition, one to 11 sequences were shared between Pv3 and many (11) soybean chromosomes (Figure 2). Eleven phenylpropanoid pathway genes were identified on chromosome Pv3, including five cloned in this study (IFS-CV670762, 4CL1-CV670737, F3H-CW652103, IFR-CV670750, and 3RT-CV670748). Two copies of the 4CL1 gene were found 13,788 bp apart on the common bean chromosome Pv3 (4CL1-2 at the start position 34,628,464 nt and 4CL1-1 at the start position 34,642,252 nt, respectively). Soybean seed coat color gene Wp, (purple flower and hypocotyl color and the production of black pigment in the seed coat) associated previously with flavanone 3-hydroxylase (F3H) on chromosome Gm02 (Zabala and Vodkin, 2005), was mapped to the expected region that was syntenic to common bean F3H. Previously, RAPD marker OAM10 was associated with common bean seed coat pattern gene Z (zonal) and was positioned between markers Bng12 and Bng165 on chromosome Pv3 (McClean et al., 2002). However, in the current study there were no significant BLAST hits with sequence of this marker and the Z gene was tentatively positioned in the region between the closest SSRs, Bng75 and Bng165.

Pv4. Blocks of soybean chromosomes Gm13 (five features)/Gm19 (eight features) were syntenic with common bean chromosome Pv4, as detected previously (McClean et al., 2010). A new syntenic block was identified with soybean chromosomes Gm16 (12 features) and Gm09 (13 sequence features). In addition, one to four sequences were shared between Pv4 and several (seven) additional soybean chromosomes (Figure 2). Six phenylpropanoid pathway genes were identified on common bean chromosome Pv4, including chalcone reductase (CHR-CW652099) cloned in this study. There were no significant BLAST hits with markers OU14, OAP3, and OAP14 (McClean et al., 2002) associated with the common bean seed coat gene G (yellow seed coat, from Gelbe in German) and the gene was tentatively positioned in the region between the closest SSRs, BM68, and Bng224.

Pv5. Blocks of soybean chromosomes Gm15 (13 features)/Gm13 (16 sequence features) and Gm12 (seven features)/GmGm13 were syntenic with common bean chromosome Pv5, as identified previously (McClean et al., 2010). In addition, one to two sequences were shared between Pv5 and several (seven) soybean chromosomes, including Gm08 (two features) previously identified as a syntenic block (Gm08/Gm 12, McClean et al., 2010) (Figure 2). Four phenylpropanoid pathway genes were identified on common bean chromosome Pv5, two cloned in this study (CCR-CV670739 at the start position 40,358,576 nt and 4CL2-CV670738 at the position 40,478,924 nt). CCR and 4CL2 genes were also identified on syntenic soybean chromosomes Gm15 and Gm13, respectively positioned in the reverse orientation at the chromosome ends.

Pv6. Blocks of soybean chromosomes Gm08 (15 sequence features)/Gm18 (nine features), Gm13 (10 features)/Gm15, Gm08/Gm15, Gm15/Gm09 (11 features), and Gm19 (three features) and Gm12 (five features) were syntenic with common bean chromosome Pv6, as identified previously (McClean et al., 2010). In addition, one to two sequences were shared between Pv6 and six additional soybean chromosomes (Figure 2). Nine phenylpropanoid pathway genes were found on the common bean chromosome Pv6, including four cloned in this study (Myb4-CW652106, PER-FBP1-CW652094, 7IOMT-CV670751, and PER-FBP4-CW652095). Two copies of the common bean transcription factor gene Myb4 (23,032,616 nt) were identified on soybean chromosomes Gm19 and Gm16, respectively. A cluster of 10 PERs (FBP1-AF149277) found at the positions 24,384,794 nt to 24,475,020 nt was syntenic to six PERs on the soybean chromosome Gm15 and six genes on Gm09, both clusters in reverse order. Another example is a single PER gene (FBP4-AF149279) on the common bean chromosome Pv6 (30,963,524 nt) associated with two clusters of four soybean peroxidases on the chromosomes Gm15 and three genes on the chromosome Gm08. The sequence of the marker OD12 that was associated with the common bean seed coat color V (violet factor, changing white or pale lilac flowers into violet and causing violet to black seed coat colors) gene (McClean et al., 2002) mapped between F3′5′H-AY17551 and F6H-XM_003551443 at the top of the chromosome Pv6. In soybean, the seed coat color gene W1 is associated with F3′5′H (Zabala and Vodkin, 2007). Several F3′5′H gene-based markers (Yang et al., 2010) mapped to the location of F3′5′H on the soybean chromosome Gm13. This map position was syntenic to the region of common bean F3′5′H gene located at the top of the chromosome Pv6.

Pv7. Blocks of soybean chromosome Gm10 (39 sequence features)/Gm20 (25 features) and Gm10/Gm13 (six features) were syntenic with common bean chromosome Pv7, as identified previously (McClean et al., 2010). In addition, one to six sequences were shared between Pv7 and five soybean chromosomes (Figure 2). Thirteen phenylpropanoid pathway genes were identified on the common bean chromosome Pv7, including six cloned in this study (CHI-CV670745, C4H-CV670736, TT2-1-L, Myb15-CW652102/Myb15-Z, PAL2-CV670734/PAL2-Z, and DFR-Z/DFR1-M). Cinnamate 4-hydroxylase gene (C4H-J09447) on the common bean chromosome Pv7 was associated with one copy on soybean chromosome Gm20 and second on the chromosome Gm10. A BLAST search with the RAPD marker sequence OU3, which is tightly linked with the common bean seed coat color P gene (pigment ground factor) on chromosome Pv7 (Erdmann et al., 2002), had no significant hits in our search. The P gene was tentatively placed between two closest SSR markers, Bng42, and BM210.

Pv8. Two large syntenic blocks were found between common bean chromosome Pv8 and soybean chromosome blocks from Gm18 (34 sequence features)/[Gm02 (18 features), Gm8 (10 features), Gm09 (17 features), Gm07 (6 features)], and Gm14 (19 features)/Gm02, as identified previously (McClean et al., 2010). In addition, one to six sequences were shared between Pv8 and eight other soybean chromosomes (Figure 2). Fifteen phenylpropanoid pathway genes were identified on the common bean chromosome Pv8, including six cloned in the current study (HD-CV670753, GST1-CW652097, WIP-CW652101, GST2-CV670756, VT-CV670747, and PAL3-CV670735/PAL3-Z). Most of these sequences were associated with two copies on two soybean chromosomes. The only exceptions were polyphenol oxidase (PPO-ABL67928) with a single sequence and isoflavonoid glucosyltransferase (IFGT-EV280635) with two sequences on chromosome Gm18. The sequence of RAPD marker OW17, which was associated with the common bean seed coat color gene Gy (greenish-yellow factor; McClean et al., 2002) was mapped at the top portion of the chromosome Pv8 close to a cluster of Myb transcription factors. Soybean SSR marker Sat_293, associated with the seed coat color R gene (Yang et al., 2010), was also mapped to this region of the chromosome Pv8 and to the syntenic region on the soybean chromosome Gm09. A second marker (OAP2; McClean et al., 2002) sequence, linked to seed coat color gene C (required for complete seed coat color) mapped between SSR markers BM165 and BM153, close to the glutathione S-transferase (GST-AY220095) sequence on the chromosome Pv8.

Pv9. Common bean chromosome Pv9 was syntenic to sequence blocks of soybean chromosomes Gm04 (28 shared sequence features)/Gm06 (33 features), as identified previously (McClean et al., 2010). The region at the lower arm of common bean chromosome Pv9 containing six g markers was syntenic to regions in soybean chromosomes Gm09 and Gm15. In addition, one to two sequences were shared between Pv9 and four other soybean chromosomes (Figure 2). Eight phenylpropanoid pathway genes were identified on the common bean chromosome Pv9, including three cloned in this study (COMT-CV670741, LIM-CW652092, and F3′H-CV707760). Common bean chalcone isomerase (CHI-AY595417) positioned at 20,929,174 nt was associated with a single copy on the soybean chromosome Gm06 but was missing from duplicated region on the chromosome Gm04. The RAPD marker sequence OM19, linked to seed coat pattern T gene (McClean et al., 2002), mapped on the common bean chromosome Pv9 between pterocarpan reductase (PTR-TC433083) and LIM transcription factor (LIM-BU764417). Several soybean seed coat color T gene-based markers [associated with F3′H (Yang et al., 2010)] were mapped to the F3′H location on chromosome Gm06 and to the syntenic region on common bean chromosome Pv9.

Pv10. Common bean chromosome Pv10 was syntenic to soybean chromosome blocks of Gm07 (16 shared sequence features)/Gm08 (nine features) and Gm16 (four features), as identified previously (McClean et al., 2010). In addition, one to four sequences were shared between chromosome Pv10 and seven soybean chromosomes (Figure 2). Six phenylpropanoid pathway gene sequences mapped to the common bean chromosome Pv10, none of which were cloned in the current study. Several transcription factors were found on the common bean chromosome Pv10. Interestingly, for common bean transcription factor Myb11-NM_116126 (29,502,170 nt) only one copy was found on the soybean chromosome Gm19. Sequences of RAPD markers associated with three seed coat pattern genes (McClean et al., 2002) were mapped on the chromosome Pv10. The markers OM9, linked with the gene Ana, and OJ17 linked with the Bip gene, mapped to the top arm of chromosome Pv10, between markers BM157 and g1029. Marker OL4, linked to the seed coat pattern L gene, mapped to the bottom arm of chromosome Pv10 close to the Myb123 transcription factor (Myb123-AJ2994452).

Pv11. Common bean chromosome Pv11 was syntenic to sequence blocks of soybean chromosomes Gm11 (16 features)/Gm12 (20 features), as identified previously (McClean et al., 2010), and Gm06 (seven features)/Gm12. In addition, one to four sequences were shared between chromosome Pv11 and seven other soybean chromosomes (Figure 2). Five phenylpropanoid pathway genes were found on the common bean chromosome Pv11 including MybTT2 transcription factor (TT2-2-L) that was cloned in this study. Isoflavonoid reductase (IFR-AF20184) mapped on the common bean chromosome Pv11 (3,852,808 nt) was also associated with the clusters of three genes on the soybean chromosome Gm11 and four genes on the soybean chromosome Gm01.

Potential uses of whole genome sequences: common bean and soybean examples

The availability of common bean and soybean whole genome sequences could have significant impact on genetics and breeding of these important legume crops. The phenylpropanoid pathway is associated with many agriculturally-important traits, including disease resistance, nodulation or seed coat color. The whole genome sequences could be used to develop gene-specific markers, study gene structure or identify genes underlying important QTL.

4-coumarate:CoA-ligase (4CL): an enzyme associated with many traits

To illustrate potential application of common bean and soybean whole genome sequences, we selected 4-coumarate:CoA ligase (4CL), a key enzyme of general phenylpropanoid pathway, positioned at the branching point leading to biosynthesis of lignin/lignans, flavonoids/anthocyanins, isoflavonoids or stilbenes for a detailed analysis. Two common bean 4CL gene fragments homologous to soybean genes 4CL1 and 4CL2, respectively, were isolated in this study (Table 2) and in silico mapped in both common bean and soybean (Figure 2).

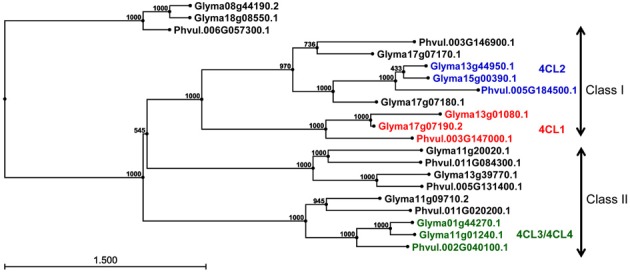

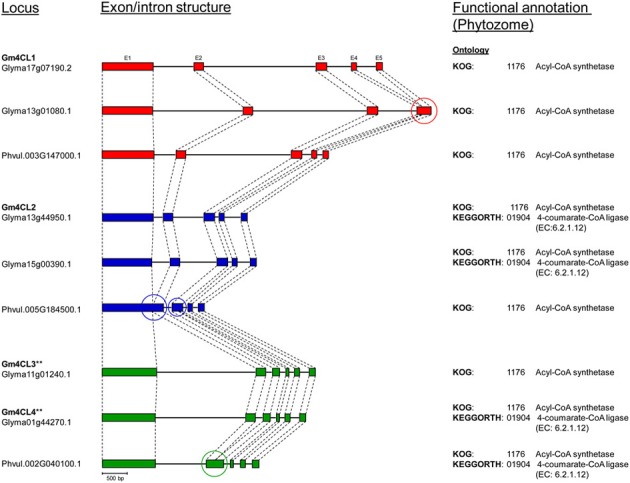

Genome organization of 4CL genes in common bean and soybean. Using soybean 4CL4 (X69955) cDNA sequence as a query, 128 common bean and soybean 4CL homologous protein sequences were retrieved from the Phytozome. The alignment of 98 primary transcripts (CLC Genomics Workbench, data not shown) and Neighbour Joining analysis produced a phylogenetic tree revealing complex relationships among 33 common bean and 65 soybean sequences (Figure S1A). Based on the similarity with the four published soybean 4CLs [Accessions AF279267 (4CL1), AF002259 (4CL2), AF002258 (4CL3), and X69955 (4CL4)], 21 sequences were selected and re-analyzed. All of the proteins belonged to the AFD_class_I superfamily (cl17068, adenylate forming domain, class I) of acyl- and aryl-CoA ligases. Proteins similar to soybean 4CL1 (Glyma17g07190.2) and 4CL2 (Glyma13g44950.1) formed two separate clusters, while soybean 4CL3 (Glyma11g01230.1) and 4CL4 (Glyma01g44270.1) grouped together (Figure S1B).

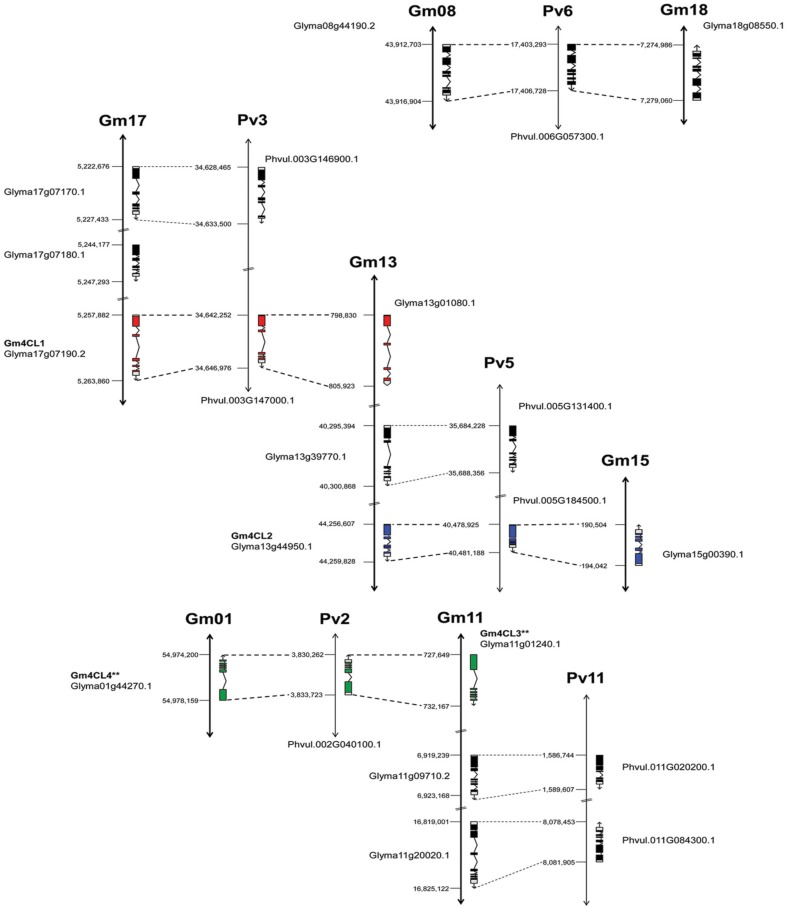

The genomic sequences were separated into two groups (Figure 3). The larger group consisted of 18 sequences and was divided into three clusters. The first cluster was further divided into two subclusters and contained class I 4CLs. Soybean 4CL1 (AF279267) sequence was in the second group. This sequence, mapped to chromosomes Gm17 (Glyma17g07190 at position 5,257,882 nt) and grouped with a soybean gene on chromosome Gm13 (Glyma13g01080 at position 798,830 nt) and a common bean gene on the chromosome Pv3 (Phvul003G147000 at position 34,642,252 nt). A subgroup containing soybean 4CL2 (AF002259) was further separated into two groups. The 4CL2 gene (Glyma13g44950) mapped on chromosome Gm13 (at position 44,256,607 nt) grouped with the soybean gene on chromosome Gm15 [Glyma15g00390 at position 194,042 nt; both soybean genes are annotated as 4CLs (KEGGORTH, Phytozome)] and a common bean gene on the chromosome Pv5 (Phvul.005G184500 at position 40,478,925 nt). Soybean gene Glyma17g07180 (position at Gm17:5,244,177 nt) was joined to this cluster while the second soybean sequence (Glyma17g07170 at position Gm17:5,222,676 nt) and common bean gene (Phvul.003G146900 at position Pv3:34,628,465 nt) made a separate branch. All three genes are annotated as 4CLs (KEGGORTH, Phytozome). Soybean genes 4CL3 (AF002258) on chromosome Gm11 (Glyma11g01240 at position 732,167 nt) and 4CL4 (X69955) on the chromosome Gm01 [Glyma01g44270 at position 54,978,159 nt, annotated as 4CL (KEGGORTH, Phytozome)] grouped together with a common bean gene on the chromosome Pv2 (Phvul.002G040100 at position 3,833,723 nt, annotated as 4CL (KEGGORTH, Phytozome)]. These genes belong to class II of 4CL enzymes. Two additional genes (soybean Glyma11g09710 at position Gm11:6,919,239 nt and common bean Phvul.011G020200 at position Pv:1,586,744 nt) made a separate branch of this group. The middle cluster was separated into two subclusters each consisting of one soybean and one common bean gene, all annotated as 4CLs (KEGGORTH, Phytozome). In addition, a group of two soybean (Glyma08g44190 and Glyma18g08550) and one common bean (Phvul.006G057300) 4CL gene sequences [annotated as 4CLs (KEGGORTH, Phytozome)] formed an independent cluster (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic analysis of 4CL genes in common bean and soybean. Phylogenetic tree was constructed from 4CL genomic sequences using Neigbor Joining (NJ) algorithm and 1000 bootstrap replications in CLC Genomics Workbench 3. Scale represents genetic distance and node numbers indicate bootstrap support values.

The genome distribution of these genes is illustrated in Figure 4. Out of the 13 soybean 4CLs identified, nine are located on three chromosomes (Gm17, Gm13, and Gm11) and six out of eight common bean genes were also found on three chromosomes (Pv3, Pv5, and Pv11). For example, soybean chromosome Gm17 contains a cluster of three genes, including 4CL1 (Glyma17g07190) on the third position. A second copy of this gene is found on the top arm of chromosome Gm13 and the common bean 4CL1 gene (Phvul.003G146900) on the chromosome Pv3. The soybean 4CL2 gene (Glyma13g44950) was found on the lower arm of chromosome Gm13, and a second copy (Glyma15g00390) on chromosome Gm15 but in the reverse orientation. The common bean 4CL2 gene (Phvul.005G184500) was mapped to chromosome Pv5. The soybean 4CL4 gene (Glyma01g44270) was positioned on the chromosome Gm01 and the 4CL3 gene (Glyma11g01240) was mapped on the top arm of chromosome Gm11 but in the reverse orientation. Common bean 4CL3/4 gene (Phvul.002G040100) was mapped on the chromosome Pv2.

Figure 4.

Genome organization of 4CL genes in soybean and common bean. Black bars represent chromosomes. Exon/intron structure of 4CL genes (Phytozome) is indicated. Exons are represented as filled boxes and introns are shown as lines between the exons. Sequence orientation on the chromosome is indicated with an arrow. **Exon/intron structure of Glyma01g44270 and Glyma11g01240 loci was corrected based on the Phytozome/GenBank/cDNA sequence alignments.

The annotated genes do differ in size and structure, and we examined exon/intron structure of six soybean and three common bean 4CL genes (Table S3). They have coding regions of similar size [shortest (1617 bp) in 4CL2-2 (Glyma15g00390) and largest (1713 bp) in 4CL3 (Glyma11g01240)] arranged in four to six exons. All nine genes are characterized by the presence of a large exon 1 [978 bp in Glyma15g00390 (4CL2-2) to 1201 bp in common bean Phvul.005G185500 (4CL2)]. The sizes of introns were more variable, and the total size of introns ranged from 332 bp in common bean Phvul.005G184500 (4CL2) to 4758 bp in soybean Glyma13g01080 (4CL1-2). All three common bean 4CL sequences had smaller total intron sizes when compared to their soybean homologs within the same group. Comparison of these nine genes at the exon/intron level confirmed very close relationships between soybean 4CL3 and 4CL4 genes (Figure 5). Similarly, two soybean 4CL2 genes are closely related, as are soybean 4CL1 and common bean 4CL1.

Figure 5.

Comparison of 4CL genes exon/intron structure between soybean (Williams 82, Phytozome) and common bean (G19833, Phytozome). Exons (E) are represented as filled boxes and introns are shown as lines between the exons. **Exon/intron structure (exon 1 and intron 1) of Glyma01g44270 and Glyma11g01240 loci was corrected based on the Phytozome/GenBank/cDNA sequence alignments. Circles indicate loss/gain of exon.

Sequence polymorphisms of 4CL genes in common bean. Because of the central position in the phenylpropanoid pathway, development of gene-based markers for 4-coumarate:CoA ligase could have significant impacts on breeding common bean for various phenylpropanoids and different traits. Searches for potential inter-pool SNPs/indels were done by comparing the genomic sequences of eight 4CL genes in the Mesoamerican cultivar OAC Rex (University of Guelph, GenBank accessions KF303286 to KF303293) with those in the reference, Andean landrace G19833 (Phytozome) (Table 7).

Table 7.

Eight 4CL loci in common bean cultivars G19833 and OAC Rex.

| G19833—Phytozomea | OAC Rex—GenBank | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4CL locus | Size (bp) | Accession | Gene | Size (bp) |

| Phvul.002G040100 | 3462 | KF303286 | 4CL-1 | 3540 |

| Phvul.003G146900 | 5036 | KF303287 | 4CL-2 | 9800 |

| Phvul.003G147000 | 4716 | KF303288 | 4CL-3 | 4880 |

| Phvul.005G131400 | 4129 | KF303289 | 4CL-4 | 4160 |

| Phvul.005G184500 | 2264 | KF303290 | 4CL-5 | 2320 |

| Phvul.006G057300 | 3436 | KF303291 | 4CL-6 | 3696 |

| Phvul.011G020200 | 2864 | KF303292 | 4CL-7 | 2960 |

| Phvul.011G084300 | 3453 | KF303293 | 4CL-8 | 3477 |

Accessed 5 June 2013.

Sequence differences were detected for all 4CL genes, with the exception of the Phvul.011G020200 (Table 8). The alignment between the two genotypes for this gene was perfect (Figure S2). For the other 4CL genes, differences in aligned sequences ranged from 17 bp in OAC Rex accession KF303290 (Phvul.005G184500 gene) to 4785 bp in the accession KF303287 (Phvul.003G146900 gene) and were found in both, coding and non-coding regions. For example, Phvul.006G057300 gene comparison revealed 18 single nucleotide substitutions and two deletions (eight nucleotides in intron 1 and a single nucleotide in intron 4) in OAC Rex sequence.

Table 8.

Polymorphism of 4CL gene sequences in Mesoamerican common bean cultivar OAC Rex compared to the reference, Andean landrace G19833.

| OAC Rex accession G19833 locus | Polymorphism | 5′UTR | E1 | I1 | E2 | I2 | E3 | I3 | E4 | I4 | E5 | I5 | E6 | 3′UTR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|