Abstract

Zinc and copper are trace elements essential for proper folding, stabilization and catalytic activity of many metalloenzymes in living organisms. However, disturbed zinc and copper homeostasis is reported in many types of cancer. We have previously demonstrated that copper complexes induced proteasome inhibition and apoptosis in cultured human cancer cells. In the current study we hypothesized that zinc complexes could also inhibit the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity responsible for subsequent apoptosis induction. We first showed that zinc(II) chloride was able to inhibit the chymotrypsin-like activity of a purified 20S proteasome with an IC50 value of 13.8 μM, which was less potent than copper(II) chloride (IC50 5.3 μM). We then compared the potencies of a pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PyDT)-zinc(II) complex and a PyDT-copper(II) complex to inhibit cellular proteasomal activity, suppress proliferation and induce apoptosis in various human breast and prostate cancer cell lines. Consistently, zinc complex was less potent than copper complex in inhibiting the proteasome and inducing apoptosis. Additionally, zinc and copper complexes appear to use somewhat different mechanisms to kill tumor cells. Zinc complexes were able to activate calpain-, but not caspase-3-dependent pathway, while copper complexes were able to induce activation of both proteases. Furthermore, the potencies of these PyDT-metal complexes depend on the nature of metals and also on the ratio of PyDT to the metal ion within the complex, which probably affects their stability and availability for interacting with and inhibiting the proteasome in tumor cells.

Keywords: Zinc, Copper, Proteasome inhibitor, Apoptosis, Calpain, Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate

Introduction

Almost one century ago, zinc and copper were recognized as trace elements with important roles in various metabolic processes in living organisms (Labbe and Thiele, 1999; Andreini et al., 2006). Zinc is the second most abundant transitional metal ion in human body, essential for the proper function of different enzymes and for a tight control of gene expression (Maverakis et al., 2007). Moreover, the catalytic domain of all known matrix metalloproteinases contains a zinc-binding motif and an additional structural zinc ion required for the stability and the expression of the enzymatic activities (Marchenko et al., 2002; Malemud 2006).

Copper plays a central role in conserved processes, such as respiration, and in highly specialized processes, such as protein modifications. Additionally, angiogenesis, a process critical for tumor growth, requires copper as an essential cofactor that stimulates cytokine production, extracellular matrix degradation, and endothelial cell migration mediated by integrins (Eatock et al., 2000; Fox et al., 2001; Brewer, 2001). Having these important physiologic functions, it is not surprising that the concentrations of both zinc and copper are tightly regulated in an organism (Maverakis et al., 2007; Labbe and Thiele, 1999). Interestingly, disturbed zinc homeostasis and the elevated copper level have been reported in many types of cancer, including breast, prostate, lung, and brain (Geraki et al., 2002; Nayak et al., 2003; Diez et al., 1989; Yoshida et al., 1993).

Dithiocarbamates are a class of metal-chelating, antioxidant compounds with various applications in medicine for the treatment of bacterial and fungal infections, and possible treatment of AIDS (Schreck et al., 1992; Malaguarnera et al., 2003). One of the dithiocarbamates, pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PyDT), is a synthetic analog that has been reported to inhibit nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) activation (Parodi et al., 2005; Schreck et al., 1992). However, when combined with either zinc(II) or copper(II) chloride, PyDT was shown to inhibit the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Kim et al., 2004; Daniel et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2005a). We have previously shown that PyDT-copper inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in cultured breast and prostate cancer cells by inhibiting proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity (Daniel et al., 2005; Chen et al., 2005a). Based on that and similar location of zinc and copper in the periodic table, we hypothesized that the PyDT-zinc complex could have similar effect on the proteasome.

The ubiquitin–proteasome pathway is essential for many fundamental cellular processes, including the cell cycle, apoptosis, angiogenesis and differentiation (Orlowski and Dees, 2003; Landis-Piwowar et al., 2006). The proteasome contributes to the pathological state of several human diseases including cancer, in which some regulatory proteins are either stabilized due to decreased degradation or lost due to accelerated degradation (Ciechanover, 1998). 20S proteasome, the proteolytic core of 26S proteasome complex, contains multiple peptidase activities (including the chymotrypsin-like, trypsin-like and peptidylglutamyl peptide hydrolyzing-like/PGPH) (Seemuller et al., 1995). It has been shown that inhibition of chymotrypsin-like but not trypsin-like proteasomal activity is a strong stimulus that induces apoptosis (An et al.,1998; Lopes et al.,1997). The possibility of therapeutically targeting the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway was met with great skepticism at the very beginning, since this pathway plays an important role in normal cellular homeostasis as well. However, after the demonstration that actively proliferating cancer cells are more sensitive to apoptosis-inducing stimuli, including proteasome inhibition, proteasome inhibitors became even more attractive (Dou and Li, 1999; Almond and Cohen, 2002; Orlowski and Dees, 2003; Adams, 2003).

To identify the component of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway affected by PyDT-zinc, we first tested the ability of zinc(II) chloride to inhibit the chymotrypsin-like activity of the purified 20S proteasome, using copper(II) chloride as a comparison. We then compared the abilities of PyDT mixtures with zinc or copper to inhibit the cellular proteasome and induce apoptosis in various breast and prostate cancer cell lines. We found that PyDT-zinc(II) and PyDT-copper(II) mixtures and synthetic complexes exert their toxic effects against the cancer cells, associated with inhibition of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity. We also found that both complexes induced apoptosis with different potencies, kinetics and molecular mechanisms. The potencies of PyDT-metal complexes depend not only on the nature of metals but also on the ratio of PyDT to the metal ion within the complex, which probably determines their stability and availability to interact with the tumor cellular proteasome.

Materials and methods

Materials

Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate (PyDT), CuCl2, ZnCl2, 3-[4,5-dimethyltiazol-2-yl]-2.5-diphenyl-tetrazolium bromide (MTT), epidermal growth factor, insulin, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), 1,4-dithio-DL-threitol (DTT), N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), cremophor and other chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). RPMI 1640, DMEM/F12 (1:1), fetal bovine serum, penicillin, and streptomycin were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) and MEME from ATCC (Manassas, VA). Purified rabbit 20S proteasome, and fluorogenic peptide substrates Suc-LLVY-AMC and Ac-DEVD-AMC (for the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like and caspase-3 activity, respectively) were from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Mouse monoclonal antibody against human poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) was purchased from BIOMOL International LP (Plymouth Meeting, PA). Mouse monoclonal antibodies against Bax (B-9), p27 (F-8), ubiquitin (P4D1), goat polyclonal antibody against actin (C-11), rabbit polyclonal antibody against IκB-α (C-15), and secondary antibodies were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc. (Santa Cruz, CA). Mouse monoclonal antibody against small subunit of μ-or m-calpains (calpain 1 and 2, respectively) (30 kDa) was purchased from Chemicon (Billerica, MA). Calpastatin was from Calbiochem and TUNEL assay kit from BD Biosciences Pharmingen, APO-DIRECT™ (San Diego, CA).

Synthesis of bis(1-pyrrolidinecarbodithioato-kS,kS′)copper(II) [(PyDT)2Cu] and bis(1-pyr-rolidinecarbodithioato-kS,kS′)zinc(II) [(PyDT)2Zn]

(PyDT)2Cu and (PyDT)2Zn were synthesized following the literature (Shinobu et al., 1984; Orvig and Abrams, 1999). The powder of CuCl2 or ZnCl2 was added to a water solution of PyDT ammonium salt under vigorous stirring, in a metal-to-ligand molar ratio 1:2. This led to the immediate formation of a solid precipitant that was filtered, washed with water, and dried in a dessicator with P4O10, giving a final yield of 90–95%. Chemical composition of both final products was confirmed by the elemental analysis.

Cell culture and cell extract preparation

Human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells and prostate cancer PC-3 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U/mL of penicillin, and 100 μg/mL of streptomycin, at 37 °C in a humidified incubator with an atmosphere of 5% CO2. Human breast cancer MCF10dcis.com (DCIS) and MCF-7 cell lines were grown as previously described (Daniel et al., 2004; Milacic et al., 2006). A whole cell extract was prepared as previously described (An et al., 1998).

In vitro proteasomal activity assay

Purified rabbit 20S proteasome (35 ng) was incubated with 20 μM of the fluorogenic peptide substrate Suc-LLVY-AMC in 100 μL assay buffer [20 mmol/L Tris–HCl (pH 7.5)] in the presence of ZnCl2, CuCl2, PyDT-ZnCl2 mixture, PyDT-CuCl2 mixture, (PyDT)2Zn, (PyDT)2Cu, or PyDT at various concentrations or equivalent volume of solvent DMSO as control. After 2 h incubation at 37 °C, inhibition of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity was measured (Chen et al., 2005b).

Proteasome activity assay using breast and prostate cancer cells

MDA-MB-231, DCIS and MCF-7 breast cancer cells and PC-3 prostate cancer cells were grown to 70–80% confluency, treated under various conditions, harvested, and used for whole cell extract preparation. Ten (10) micrograms of cell extract was then used to determine the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity, as described above.

Cell proliferation assay

The MTT assay was used to determine the effects of various compounds on breast or prostate cancer cell proliferation. Cells were plated in a 96-well plate and grown to 70–80% confluency, followed by addition of each compound at the indicated concentrations. After 24 h incubation at 37 °C, inhibition of cell proliferation was measured as previously described (Milacic et al., 2006).

Cellular morphology analysis

A Zeiss (Thornwood, NY) Axiovert 25 microscope with phase contrast was used for cellular morphology imaging, as previously described (Daniel et al., 2005).

Caspase-3 activity assay

MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were treated with different concentrations of (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu for different time points, as indicated in the legends. The prepared whole cell extracts (30 μg per sample) were then incubated with 40 μM of Ac-DEVD-AMC in 100 μL assay buffer at 37 °C for at least 2 h. The release of the AMC groups was measured as previously described (Chen et al., 2005b).

Western blot analysis

Various breast and prostate cancer cell lines were treated as indicated in the figure legend. Cell lysates (50 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, followed by visualization using the enhanced chemiluminescence kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ), as previously described (Chen et al., 2005b).

TUNEL assay and cell cycle analysis

Terminal deoxynecleotydyl transferase-mediated dUPT-biotin nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay and cell cycle analysis were performed using the BD Biosciences Pharmingen, APO-DIRECT™ kit (San Diego, CA). Cells were treated with 20 μM of (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu for 16 h, harvested, fixed and stained according to the protocol.

Results

In vitro inhibition of the chymotrypsin-like activity of purified 20S proteasome by zinc(II) chloride and a PyDT-zinc(II) mixture

We have previously shown that copper dithiocarbamates could inhibit proteasomal activity in highly metastatic MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (Daniel et al., 2005). Zinc was also found to be involved in inhibition of the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway (Kim et al., 2004), but the detailed mechanism has not been completely understood.

We hypothesized that zinc is an inhibitor of the protesomal chymotrypsin-like activity. To test this hypothesis, we first incubated a purified rabbit 20S proteasome with zinc(II) chloride or copper(II) chloride (as a control) at various concentrations, followed by measurement of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity. We found that zinc(II) chloride was able to inhibit the chymotrypsin-like activity of the purified 20S proteasome with an IC50 value of 13.8 μmol/L. Similar to previously reported (Daniel et al., 2004), the IC50 value of copper(II) chloride against the purified proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity was determined as 5.3 μmol/L. Therefore, zinc(II) chloride also inhibits proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity but with lower potency than copper(II) chloride.

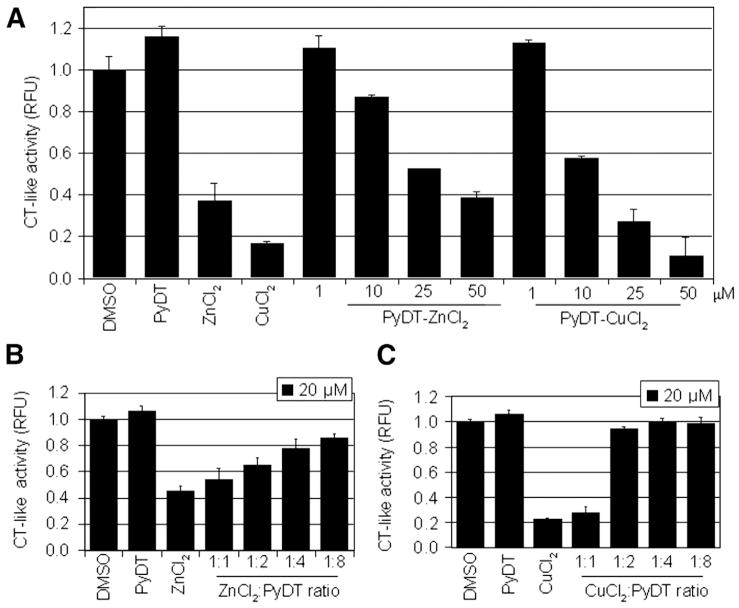

To assess the proteasome-inhibitory effect of PyDT-zinc mixture, we mixed equal volumes of zinc(II) chloride or copper(II) chloride (as a comparison) with PyDT (Fig. 1A) and tested their proteasome-inhibitory potencies against the purified 20S proteasome. We found that 50 μmol/L PyDT mixture with copper(II) chloride inhibited ~90%, while the same concentration of PyDT mixture with zinc(II) chloride inhibited ~60% of the proteasomal activity (Fig. 1A). As a control, 50 μmol/L of PyDT alone induced a slight increase in the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity, while 50 μmol/L of zinc(II) chloride or copper(II) chloride caused a significant inhibition (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Inhibition of the purified 20S proteasome by zinc and copper and their mixtures with PyDT. A, Purified rabbit 20S proteasome (35 ng per reaction) was incubated with a peptide substrate for the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity in the presence of 50 μM PyDT, ZnCl2, CuCl2, or PyDT mixture with zinc (PyDT-ZnCl2) or copper (PyDT-CuCl2) at indicated concentrations. DMSO was used as a control. B and C, Inhibition of the chymotrypsin-like activity of the purified rabbit 20S proteasome by PyDT-ZnCl2 (B) or PyDT-CuCl2 (C) mixtures at indicated molar ratios. Columns, mean of representative independent triplicate experiments; bars, SD.

We also determined how the ratio of PyDT ligand to zinc or copper ion affected their proteasome-inhibitory activities. We mixed zinc(II) chloride or copper(II) chloride with PyDT in different ratios, from 1:1 to 1:8, and then tested the potencies of formed mixtures to inhibit the purified 20S proteasome. We found that by increasing the concentration of PyDT molecules that reacted with the fixed concentration of zinc(II) or copper(II) chloride molecules, the potency of these mixtures to inhibit the proteasome activity significantly decreased (Figs. 1B and C). In the subsequent experiments, we therefore used the mixtures containing 1:1 ratio of zinc(II) chloride or copper(II) chloride to PyDT.

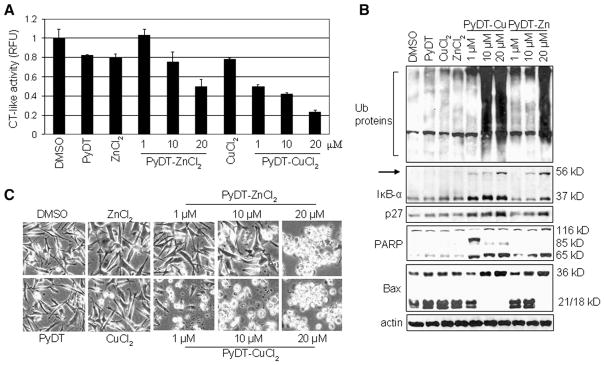

PyDT-zinc complex is a proteasome inhibitor and an apoptosis inducer in intact MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells

After we showed that zinc(II) chloride and PyDT-zinc mixture could inhibit the purified 20S proteasome (Fig. 1), we wanted to test if zinc salt and its PyDTmixture would inhibit the proteasome in intact cancer cells. For that reason, MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells were treated for 18 h with various concentrations of zinc(II) chloride, PyDT-Zn mixture, or PyDT alone, and with copper(II) chloride or PyDT-copper mixture as a comparison. We found that both PyDT-zinc and PyDT-copper mixtures were able to inhibit the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2A). PyDT-zinc mixture at 10 and 20 μmol/L induced 25% and 50% inhibition of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity, respectively (Fig. 2A). Treatment with 1 μmol/L PyDT-copper mixture induced about 50% of the proteasomal inhibition, while 20 μmol/L PyDT-copper mixture inhibited almost 80% of the proteasomal activity (Fig. 2A). However, zinc(II) chloride, copper (II) chloride and PyDT, all at 20 μmol/L concentration, inhibited only ~20% of the proteasomal activity (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

PyDT mixtures with zinc and copper inhibit the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity and induce apoptosis in intact MDA-MB-231 cells. A, MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 20 μmol/L PyDT, ZnCl2, or CuCl2, or with PyDT mixtures with zinc (PyDT-ZnCl2) or copper (PyDT-CuCl2) at indicated concentrations for 18 h. Columns, mean of representative independent triplicate experiments; bars, SD. B, Western blot analysis for accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins, proteasome target proteins (IκB-α and p27), PARP cleavage and p36/Bax in the cell extract prepared after 18 hour treatment. C, Apoptotic morphological changes in the MDA-MB-231 cells treated for 18 h as indicated, visualized by phase-contrast imaging.

Accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins was found in the cells treated with 20 μmol/L PyDT-zinc and with 10 and 20 μmol/L PyDT-copper mixture, together with the accumulation of proteasomal target proteins IκB-α and p27 (Fig. 2B). The main role of IκB-α is to bind transcription factor NF-κB (nuclear factor kB) in the cytoplasm and prevent its translocation to the nucleus, where it induces gene expression of proteins critical for cellular proliferation. Phosphorylation of IκB-α results in its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the 26S proteasome complex. Inhibition of the proteasomal activity leads to the accumulation of IκB-α, resulting in NF-κB inactivation. We have previously reported an ubiquitinated form of IκB-α protein with molecular weight of ~56 kDa (Chen et al., 2005a). A similar p56 band appeared after the treatment with 10 and 20 μmol/L PyDT-zinc and 1,10 and 20 μmol/L PyDT-copper mixture (Fig. 2B). Accumulation of this band, together with the accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins confirmed that IκB-α was ubiquitinated and targeted to the proteasome but could not be degraded due to the proteasomal inhibition induced by PyDT mixtures.

It has been shown that inhibition of proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity generates a strong stimulus that induces apoptosis in cancer cells. Therefore, we measured apoptosis in the same experiment, by morphological changes (Fig. 2C) and PARP cleavage (Fig. 2B) and found apoptosis induction by 10–20 μmol/L PyDT-zinc and by 1–20 μmol/L PyDT-copper mixture. In the cells treated with PyDT-zinc, a concentration-dependent production of a single cleaved PARP fragment of 65 kD (p65) was detected, while in the cells treated with the PyDT-copper mixture, two PARP cleaved fragments, p65 and p85, were found (Fig. 2B). It has been shown that production of p85 PARP fragment is associated with caspase-3/-7 activity (Lazebnik, 1994), while the p65 PARP fragment is a result of calpain cleavage (Pink et al., 2000). The calpain involvement is further supported by the accumulation of p36/Bax, a homodimer of p18/Bax (a calpain cleaved product of p21/Bax; Gao and Dou, 2000; Wood and Newcomb, 2000) and complete disappearance of p21/Bax and p18/Bax, which was found in the cells treated with 20 μmol/L PyDT-zinc mixture and 10–20 μmol/L PyDT-copper mixture (Fig. 2B). We and others have shown that associated with the apoptotic commitment, Bax protein (p21/Bax) could be cleaved by calpain, producing a p18/Bax fragment, which then forms a homodimer p36/Bax (Gao and Dou, 2000; Wood and Newcomb, 2000). Therefore, our results demonstrate that although PyDT mixed with either zinc or copper was able to inhibit the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity, activate calpain and induce apoptosis in human breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells, only PyDT-copper complex could activate caspase-3/-7 pathway.

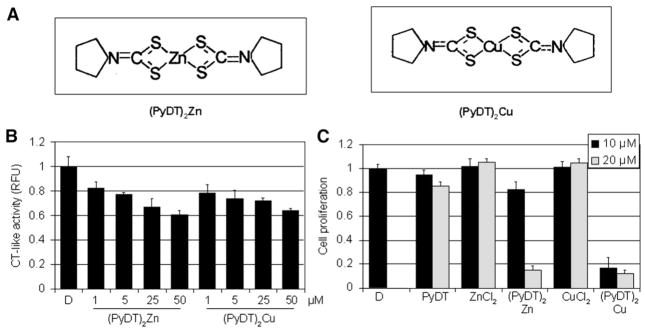

Synthetic PyDT complexes with zinc and copper induce a time-dependent proteasome inhibition and apoptosis in intact MDA-MB-231 cells

To further confirm the results generated with PyDT-metal mixtures, we synthesized PyDT-zinc (ratio 2:1) and PyDT-copper (ratio 2:1) complexes [(PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu, respectively in Fig. 3A]. Due to some technical reasons, we were unable to synthesize these metal complexes in 1:1 ratio. Because an increased ratio of PyDT to zinc or copper ion led to decreased proteasome-inhibitory potency (Figs. 1B and C), we hypothesized that the proteasome inhibition induced by these synthetic compounds should be weaker compared to corresponding 1:1 ratio mixtures. Indeed, when tested against the purified 20S proteasome, both (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu at 50 μmol/L inhibited only 40% of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity (Fig. 3B). The similar potency of both synthetic zinc and copper complexes against the purified 20S proteasomal activity (Fig. 3B) is quite different from the different effects of their inorganic salts (Fig. 1A; Daniel et al., 2004).

Fig. 3.

Synthetic compounds, (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu, inhibit the activity of purified 20S proteasome and proliferation of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. A, Chemical structures of synthetic compounds (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu. B, Inhibition of the chymotrypsin-like activity of a purified rabbit 20S proteasome by synthetic compounds (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu. Purified 20S proteasome (35 ng) was incubated with the peptide substrate for the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity in the presence of (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu at indicated concentrations, and measured as described in Materials and methods. C, Antiproliferative effects of synthetic compounds (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated for 24 h with PyDT, ZnCl2, CuCl2, or synthetic compounds, (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu, at indicated concentrations. After 24 h, medium was removed and cells treated with MTT solution. DMSO was used as a control. Columns, mean of representative independent triplicate experiments; bars, SD.

We then investigated the effect of these synthetic complexes on growth of MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. By using an MTT assay, we found that 10 μmol/L synthetic (PyDT)2Zn inhibited about 20% of MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation, while (PyDT)2Cu at the same concentration caused more than 80% inhibition (Fig. 3C). However, when used at 20 μmol/L concentration, both complexes were almost equally potent by inhibiting growth of MDA-MB-231 cells by about 90% (Fig. 3C).

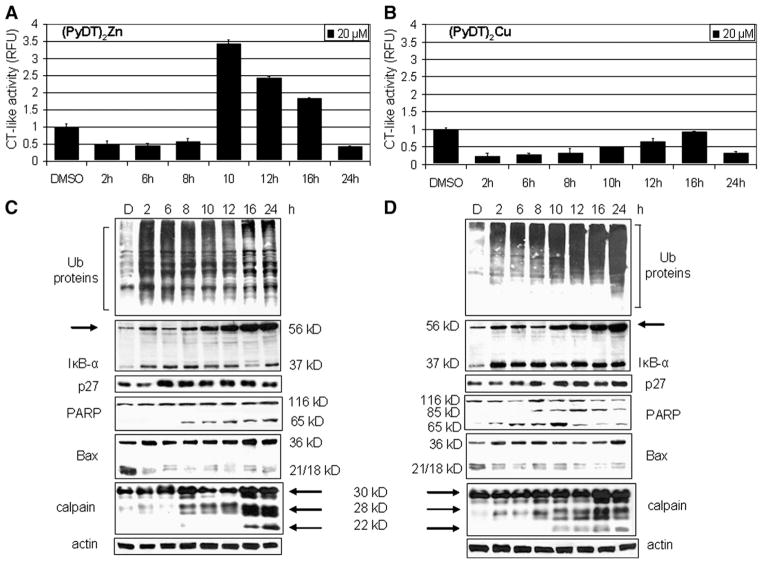

We then treated MDA-MB-231 cells with 20 μmol/L of either (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu for 2 to 24 h, followed by the measurement of the proteasomal inhibition (Fig. 4). We found that the proteasome activity was inhibited at early time points (i.e., 2 h) in the cells treated with either complex (Figs. 4A and B). However, (PyDT)2Zn inhibited ~50% of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity while (PyDT)2Cu caused almost 80% inhibition (Fig. 4A vs. B). We also observed that after 10 to 16 h of treatment, proteasomal activity recovered, but decreased again after 24 h; the involved mechanism is currently unknown. Western blot analysis showed accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins at as early as 2 h after the beginning of treatment with either compound (Figs. 4C and D). Interestingly, in (PyDT)2Zn-treated cells, the level of ubiquitinated proteins reached the peak in the first 8 h (Fig. 4C), while in (PyDT)2Cu-treated cells, the level of ubiquitinated proteins was increasing up to the last time point (24 h; Fig. 4D). Additionally, the levels of the proteasome target proteins, IκB-α and p27, as well as the ubiquitinated form of IκB-α (p56) were increasing in the cells treated with each compound, but with somewhat different kinetics (Figs. 4C and D). Therefore, both zinc and copper complexes were able to inhibit cellular proteasome activity.

Fig. 4.

Kinetic studies on the proteasome inhibition and apoptosis induction by (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu in MDA-MB-231 cells. MDA-MB-231 cells were exposed to 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu for the indicated times, followed by measurement of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity (A and B), and Western blot analysis using specific antibodies to ubiquitin, IκB-α, p27, PARP, Bax, calpain, and β-actin (C and D). Actin was used as a loading control. Columns, mean of representative independent triplicate experiments; bars, SD.

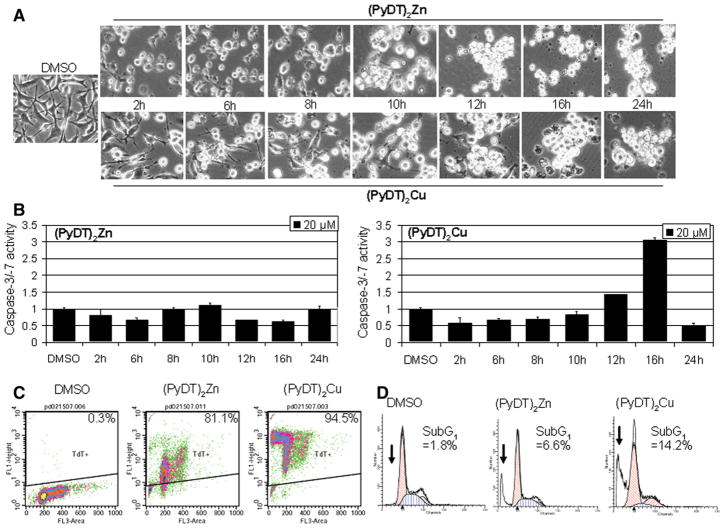

In the same kinetic experiment, apoptotic morphological changes (shrunken cells and characteristic apoptotic blebbing) were detected after 2 h of treatment with either compound, which was greatly increased after 24 h of treatment (Fig. 5A). (PyDT)2Zn treatment induced the appearance of the cleaved PARP fragment p65 after 8 h (Fig. 4C), while in the cells treated with (PyDT)2Cu, p65 was detected after first 2 h of treatment (Fig. 4D). Decreased levels of p21/Bax and p18/Bax and increased levels of p36/Bax were detected at 2 h after each treatment (Figs. 4C and D), supporting the idea of calpain activation by zinc and copper complexes. Calpain involvement was further confirmed by Western blot analysis that showed autolysis of small calpain subunit (30 kDa) into at least two cleaved fragments (~28 kDa and ~22 kDa) (Figs. 4C and D). The kinetics of the cleaved calpain 28 kDa fragment generation correlated very well with appearance of p65/PARP (Figs. 4C and D).

Fig. 5.

Kinetic studies on apoptosis induction by (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu in MDA-MB-231 cells. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu for the indicated times, followed by measurement of apoptotic morphological changes (A) and caspase-3/-7 activity (B). Columns, mean of representative independent triplicate experiments; bars, SD. For TUNEL assay (C) and sub-G1 analysis (D), MDA-MB-231 cells were treated for 16 h with 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu. The TUNEL assay was performed by using an APO-DIRECT kit and the sub-G1 populations are indicated by arrows.

Furthermore, up to 3-fold increase in caspase-3/-7 activity (Fig. 5B) and the cleaved PARP fragment p85 (Fig. 4D vs. C) were detected only in the cells treated with (PyDT)2Cu, but not (PyDT)2Zn, supporting the conclusion that only copper, but not zinc complex activated caspase-3/-7. TUNEL assay confirmed that the cell death induced by both zinc and copper complexes is apoptosis. The TUNEL results showed 81% and 95% of apoptotic cells after the 16 hour treatment with 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu, respectively (Fig. 5C). Appearance of sub-G1 population was also observed in the cells treated with either compound (Fig. 5D). These results are very similar to those generated with the PyDT-zinc and PyDT-copper mixtures (Figs. 4, 5 vs. 2). Taken together, we conclude that both zinc and copper complexes are able to inhibit the proteasome, activate calpain and induce apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, although only copper complexes could also activate caspase pathway.

Concentration-dependent proteasome inhibition and apoptosis induction by synthetic PyDT complexes with zinc and copper

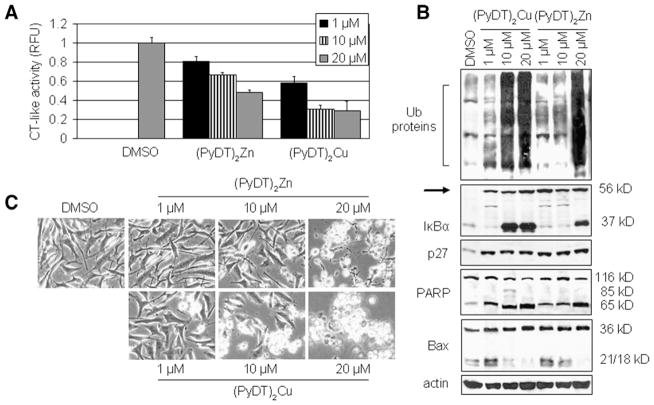

Since we showed, by using an MTT assay, that 10 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn inhibited less than 20% and 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn inhibited more than 80% of MDA-MB-231 cell proliferation (Fig. 3C), we wanted to investigate the effect of different concentrations of synthetic zinc complexes on the proteasomal activity in intact MDA-MB-231 cells. Therefore, we treated MDA-MB-231 cells for 8 h with 1,10 or 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu, followed by measurement of the proteasomal inhibition by multiple assays. Proteasomal activity was inhibited by (PyDT)2Zn in a dose-dependent manner: 20%, 30% and 50% inhibition by 1, 10 and 20 μmol/L, respectively (Fig. 6A). Consistently, (PyDT)2Cu inhibited about 40% of the proteasomal activity when used at 1 μmol/L, and caused 70% inhibition at 10 or 20 μmol/L (Fig. 6A).

Fig. 6.

Dose effects of synthetic compounds (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu on MDA-MB-231 cells. MDA-MB-231 cells were treated with either solvent alone (DMSO) or with different concentrations of (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu for 8 h, followed by the measurement of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity (A), accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and proteasome target proteins (IκB-α, p27), p36/Bax, and PARP cleavage (B), and morphological changes (C). Columns, mean of representative independent triplicate experiments; bars, SD.

Western blot analysis showed accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in the cells treated with 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn and with 10 and 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Cu (Fig. 6B). Under the same treatment conditions, accumulation of the proteasome target protein IκB-α was found (Fig. 6B). However, an increase in p27 protein level and appearance of ubiquitinated IκB-α, p56, were detected in the cells treated with all three concentrations of (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu (Fig. 6B). Although the proteasome was found to be inhibited to some extent with all three concentrations of both compounds, apoptosis was detected mainly in MDA-MB-231 cells with >50% proteasomal inhibition (Figs. 6B and C). Characteristic apoptotic morphological changes and increased p65 PARP cleavage fragment were detected in the cells treated with 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn and with 10 and 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Cu (Fig. 6C). Decreased level of p21/Bax and accumulation of p36/Bax protein under the same conditions suggested calpain activation (Fig. 6B).

Synthetic PyDT complexes with zinc and copper inhibit the proteasome and induce apoptosis in other human breast cancer and prostate cancer cell lines

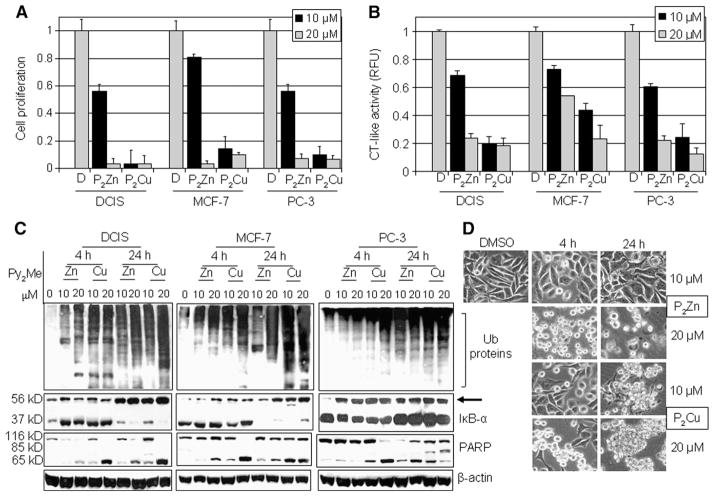

To investigate whether the observed effects of synthetic PyDT complexes with zinc and copper are restricted to MDA-MB-231 cells only, we tested their effects against two estrogen receptor α-positive breast cancer cell lines, MCF10dcis.com (DCIS) and MCF-7, and the androgen receptor-independent human prostate cancer PC-3 cells. By using an MTT assay, we first tested the growth-inhibitory effect of these compounds and found that growth of all three tested cancer cell lines was affected with both complexes (Fig. 7A). Consistent with our findings with MDA-MB-231 cells, (PyDT)2Zn was again less effective than (PyDT)2Cu when tested in these three cell lines. For example, 10 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn inhibited proliferation of DCIS, MCF-7 and PC-3 cells by 45%, 19% and 47%, respectively (Fig. 7A), while 10 μmol/L (PyDT)2Cu induced 95%, 85% and 90% growth inhibition, respectively, in these three cell lines (Fig. 7A). Both compounds at 20 μmol/L concentration induced more than 90% growth inhibition in all the three cell lines (Fig. 7A).

Fig. 7.

Effects of synthetic (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu compounds on DCIS, MCF-7 and PC-3 cell lines. A, Antiproliferative effect of synthetic compounds (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu. DCIS, MCF-7 and PC-3 cells were treated for 24 h with 10 and 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn (P2Zn) and (PyDT)2Cu (P2Cu). After treatment, medium was removed and the cells were treated with MTT solution, as described in Materials and methods. DMSO was used as a control. B, DCIS, MCF-7 and PC-3 cells were treated with either solvent alone (DMSO) or with different concentrations of (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu for 4 and 24 h (not shown), followed by the measurement of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity. Columns, mean of representative independent triplicate experiments; bars, SD. C, Western blot analysis using antibodies to ubiquitin, IκB-α and PARP. Actin was used as a loading control. D, Apoptotic morphological changes in PC-3 cells treated for 4 and 24 h with (PyDT)2Zn (P2Zn) or (PyDT)2Cu (P2Cu), as indicated.

We then treated all three cell lines with 10 and 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu for 4 and 24 h, followed by measurement of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity. Consistent with our previous findings, proteasomal activity was inhibited after both 4 h (Fig. 7B) and 24 h (data not shown) in a dose-dependent manner. Again, (PyDT)2Zn was found to be less potent then (PyDT)2Cu and MCF-7 cells were found to be less sensitive to the treatment compared to other tested cell lines (Fig. 7B). Proteasomal inhibition was confirmed with Western blot analysis that showed accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and proteasome target protein IκB-α and its ubiquitinated form (Fig. 7C). Proteasomal inhibition was followed by the apoptosis induction in these cells, as shown by PARP cleavage (Fig. 7C) and apoptotic morphological changes (Fig. 7D and data not shown).

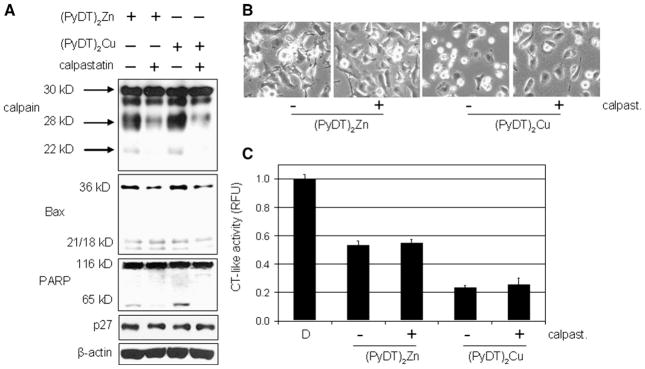

Pretreatment with the specific calpain inhibitor calpastatin partially inhibits cell death induced by synthetic (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu complexes

To confirm the role of calpain in apoptosis induced by synthetic PyDT complexes with zinc and copper, we pretreated MDA-MB-231 cells for 4 h with the specific calpain inhibitor calpastatin, followed by the addition of (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu. As expected, the pre- and co-treatment with calpastatin significantly inhibited autolysis of calpain small subunit, as evident by decreased levels of the cleaved calpain fragments, 28 kDa and 22 kDa (Fig. 8A), confirming the inhibition of the calpain activity. Consistently, calpastatin pre- and co-treatment partially inhibited the calpain-mediated p36/Bax accumulation and PARP cleavage induced by these two synthetic PyDT compounds (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, calpastatin pre- and co-treatment was able to, at least partially, prevent morphological changes caused by (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu treatment (Fig. 8B), demonstrating the functional effect. As an important control, the calpain inhibitor calpastatin did not affect the proteasomal inhibition induced by either compound, as shown by the unchanged levels of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity (Fig. 8C) and the proteasome target protein p27 (Fig. 8A). Taken together, these data suggest that calpain plays an important role in the apoptotic cell death process induced by synthetic (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT)2Cu.

Fig. 8.

Protective effect of calpastatin on MDA-MB-231 cells treated with (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu. MDA-MB-231 cells were pretreated with 10 μmol/L calpastatin for 4 h, followed by a co-treatment with either 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Zn for ~8.5 h or 20 μmol/L (PyDT)2Cu for ~2.5 h. This was then followed by Western blotting (A), morphological analysis (B), and measurement of the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity (C).

Discussion

It has been shown that ubiquitin–proteasome system plays a critical role in cancer cells and that its inhibition could prevent tumor progression and overcome drug resistance (Spataro et al., 1998; Orlowski and Dees, 2003; Landis-Piwowar et al., 2006). It has also been reported that proteasome inhibitors are potent apoptosis inducers and that cancer cells are more sensitive to the proteasome inhibition compared to normal cells (Adams, 2003; Dou and Li, 1999; Almond and Cohen, 2002; An et al., 1998). Bortezomib is the first proteasome inhibitor that received regulatory approval from the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of multiple myeloma (Adams, 2003; Dou and Li, 1999; Orlowski and Dees, 2003; Landis-Piwowar et al., 2006). However, the problem with bortezomib is its toxicity that often causes an early cessation of the treatment. In search for new, less toxic proteasome inhibitors, we have previously found that several organic copper complexes could selectively inhibit the proteasome and induce apoptosis in cultured tumor but not in normal cells (Daniel et al., 2004).

In this study, we first demonstrated that zinc ion has the ability to inhibit the proteasomal activity. When compared to copper ion, zinc ion is less potent inhibitor of purified 20S proteasome (Fig. 1A), and PyDT mixture with zinc is also less potent in inhibiting the cellular 26S proteasome and inducing apoptosis, compared to the PyDT-copper mixture (Fig. 2). We have then shown that potential of PyDT-metal mixture to inhibit the proteasome depends not only on the nature of the metal salt, but also on the ratio in which PyDT ligand and that specific metal salt were mixed together (Figs. 1B and C). By increasing the concentration of PyDT molecules available for the reaction with the same concentration of zinc(II) or copper(II) chloride molecules, the potency of formed complexes to inhibit the proteasome significantly decreased (Figs. 1B and C). Therefore, the lower potency of synthetic copper and zinc complexes against the purified 20S proteasome could be due to the fact that they contain PyDT ligand:metal ratio 2:1 (Fig. 3A).

Interestingly, after the intact breast and prostate cancer cells were treated with either complex, much higher proteasomal inhibition was found, and (PyDT)2Zn was again shown to be less potent than (PyDT)2Cu (Figs. 4 and 7). Proteasomal inhibition induced by both compounds seems to be fluctuating during the course of treatment with different kinetics (Figs. 4A and B). After 10 h of (PyDT)2Zn treatment, proteasomal activity was found to be higher compared to the control and was gradually decreasing since then, until it reached ~50% of activity at the end of the treatment (Fig. 4A). The exact mechanism by which (PyDT)2Zn increases the proteasomal chymotrypsin-like activity within the cell is not understood and needs to be further investigated. It has also been reported that human deubiquitinating isopeptidase T has three sets of zinc-binding sites and that zinc binding to high affinity sites is required for its activity (Gabriel et al., 2002). However, by binding to the set of low affinity sites, zinc ions completely abolish isopeptidase T enzymatic activity. Therefore, it is possible that the proteasome contains more than one metal-binding site, and that the number of sites occupied by zinc will determine the proteasomal activity. However, these possibilities remain to be further investigated.

In the current study we also showed that the level of accumulated ubiquitinated proteins in the cells treated with (PyDT)2Zn was somewhat decreasing after 10 h (Fig. 4C), together with the increased proteasomal activity (Fig. 4A). Since zinc is required for the catalytic activity of the human deubiquitinating isopeptidase T (Gabriel et al., 2002), it is possible that isopeptidase activity located on 19S regulatory subunit of the 26S proteasome could also be activated by (PyDT)2Zn or zinc ions released from the complex during the possible intracellular degradation. The fact that the high level of ubiquitinated proteins still remained until the end of treatment could be explained by the proteasomal inhibition observed again at the end of the treatment and by the formation of aggresomes. Aggresomes are cytoplasmic bodies formed in the cells with exceeded capacity of the proteasome degradation pathway, caused by either an increase in substrate expression or a decrease in the proteasome activity (Johnston et al., 1998). They were shown to be very stable structures that can persist for hours after washout of the proteasome inhibitors (Johnston et al., 1998). Therefore, although the proteasomal activity still remained higher than in control cells (Fig. 4C).

The apoptosis-inducing mechanisms triggered by (PyDT)2Zn and (PyDT) 2Cu seem to be different, since (PyDT)2Zn failed to activate caspase-3/-7, which was confirmed by the absence of p85 cleaved PARP fragment (Figs. 5B and 4C). On the other hand, in the cells treated with (PyDT)2Cu, 3-fold increase of caspase-3/-7 activity was detected (Fig. 5B) and the cleaved PARP fragment p85 was found (Fig. 4D), demonstrating the ability of copper complex to activate caspases (Lazebnik et al., 1994). Therefore, although both complexes induce apoptosis by inhibiting the proteasome, zinc complex works through different mechanism from copper complexes. It has been shown that calpain cleaves PARP into a p65 fragment (Pink et al., 2000). However, even though the caspase-3/-7 activity failed to be activated by zinc compound, apoptosis was still induced most probably through a calpain-dependent mechanism. The calpain involvement in the apoptotic death induced by both compounds is supported by the cleavage of small calpain subunit and accumulation of p65 PARP fragment and p36/Bax protein (Figs. 4C and D). By using a specific calpain inhibitor, calpastatin, we demonstrated that by preventing calpain autolysis and therefore its activation, accumulation of p36/Bax, cleavage of PARP and appearance of apoptotic morphological changes were partially inhibited in the cells exposed to the synthetic PyDT complexes with zinc and copper (Fig. 8). The fact that cell death was not completely abolished by calpastatin pre- and co-treatment could be explained by a partial inhibition of calpain-mediated events by calpastatin (Fig. 8A). Some level of calpain cleavage products (~28 kDa fragment, for example) and Bax/p36 was still detected by Western blotting. It is also important to emphasize that although our data suggest the involvement of calpain activation in apoptosis induced by (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu, calpain could be only one of several important players involved in this process. Therefore, by blocking only calpain activity, apoptosis could not be completely prevented, particularly in the cells treated with (PyDT)2-Cu that was shown to activate caspase-3/-7 as well (Fig. 5B).

We have also found that the proteasome inhibition and apoptosis induction caused by (PyDT)2Zn or (PyDT)2Cu could not be blocked by DTTor NAC (data not shown), suggesting that those compounds are not acting through producing reactive oxygen species (ROS). It has been published previously that zinc does not have a relevant oxidative strength, while copper caused some level of oxidation (Amici et al., 2002). However, the oxidation found by these authors was induced by milimolar concentrations of copper(II) sulfate pentahydrate, while micromolar range of copper(II) chloride was used in our studies. Moreover, when the intact cells were co-treated with either synthetic zinc or copper complex and NAC, apoptosis was not blocked (data not shown). We have shown that the proteasome inhibition induced by synthetic zinc or copper complexes in intact cells is much stronger compared to the proteasome inhibition induced under cell-free conditions (against purified proteasome), and is much closer to the inhibition induced by metal ions against the purified proteasome. Therefore, one possible explanation could be that synthetic compounds require metabolic activation within the cell, which results in releasing PyDT and metal ions. Released metal ions would then be available for binding and inhibiting the proteasome. Even if some level of ROS is induced by copper or zinc, PyDTas an antioxidant would block them, therefore excluding oxidation as a cause of the proteasomal inhibition. This is consistent with our hypothesis that direct binding of zinc or copper ion to the proteasome causes inhibition of the proteasomal activity. We have previously published that copper complex NCI-109268 was slightly less potent in inhibiting chymotrypsin-like activity of 26S proteasome in leukaemia Jurkat cell extract compared to a known proteasome inhibitor N-acetyl-leu-leunorleucinnal (LLnL) (Daniel et al., 2004). We have also shown that 8-OHQ-copper(II) mixture inhibited the proteasome and induced apoptosis selectively in intact Jurkat leukaemia and not in non-transformed, immortalized natural killer cells (YT). On the contrary, tripeptidyl proteasome inhibitor MG132 induced accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins and apoptosis in both cell lines, although YT cells were slightly more resistant compared to Jurkat T cells (Daniel et al., 2004).

It has been reported that treatment with 100 μmol/L PyDT alone can cause accumulation of the proteasome target proteins p53 and p21 and that 250 μmol/L zinc alone can inhibit the ubiquitin–proteasome activity in HeLa cells (Kim et al., 2004). In this study, we used much lower concentrations of PyDT, zinc(II) chloride, and copper(II) chloride (20 μmol/L) and showed that at this concentration, all of them induced only ~20% of proteasomal inhibition and were not toxic against MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells (Fig. 2). However, when the same concentration of PyDT combined with either zinc(II) or copper(II) was used, more than 50% of the proteasomal activity was inhibited and apoptosis was induced in all the tested cancer cell lines. Considering the hydrophilic nature of metal salts and low concentrations of both salts and PyDT used here, we propose that PyDT ligand is necessary to transport these metals into the cell (serves as a carrier), where the delivered zinc or copper could reach and inhibit their target — the proteasome. Our findings reveal that different mechanisms are involved in zinc and copper complexes-induced proteasomal inhibition and apoptosis, which should have a clinical significance.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Flow Cytometry Core at Karmanos Cancer Institute for the assistance with cell cycle analysis and TUNEL assay, Kristin R. Landis-Piwowar and Qiuzhi Cindy Cui for their assistance and Fred Miller for providing DCIS cell line.

Footnotes

Grant support: Karmanos Cancer Institute of Wayne State University (to Q. P. D.), Department of Defense Breast Cancer Research Program Awards (W81XWH-04-1-0688 and DAMD17-03-1-0175 to Q. P. D.), National Cancer Institute Grant (1R01CA120009 to Q. P. D.), and the NCI/NIH Cancer Center Support Grant (to Karmanos Cancer Institute).

References

- Adams J. Potential for proteasome inhibition in the treatment of cancer. Drug Discov Today. 2003;8:307–315. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02647-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Almond JB, Cohen GM. The proteasome: a novel target for cancer chemotherapy. Leukemia. 2002;16:433–443. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amici M, Forti K, Nobili C, Lupidi G, Angeletti M, Fioretti E, Eleuteri AM. Effect of neurotoxic metal ions on the proteolytic activities of the 20S proteasome from bovine brain. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2002;7 (7–8):750–756. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0352-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- An B, Goldfarb RH, Siman R, Dou QP. Novel dipeptidyl proteasome inhibitors overcome Bcl-2 protective function and selectively accumulate the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27 and induce apoptosis in transformed, but not normal, human fibroblasts. Cell Death Differ. 1998;5:1062–1075. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreini C, Banci L, Bertini I, Rosato A. Zinc through the three domains of life. J Proteome Res. 2006;5:3173–3178. doi: 10.1021/pr0603699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brewer GJ. Copper control as an antiangiogenic anticancer therapy: lessons from treating Wilson’s disease. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2001;226:665–673. doi: 10.1177/153537020222600712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Peng F, Cui QC, Daniel KG, Orlu S, Liu J, Dou QP. Inhibition of prostate cancer cellular proteasome activity by a pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate-copper complex is associated with suppression of proliferation and induction of apoptosis. Front Biosci. 2005a;10:2932–2939. doi: 10.2741/1749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D, Daniel KG, Chen MS, Kuhn DJ, Landis-Piwowar KR, Dou QP. Dietary flavonoids as proteasome inhibitors and apoptosis inducers in human leukemia cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2005b;69:1421–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2005.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin–proteasome pathway: on protein death and cell life. EMBO J. 1998;17:7151–7160. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.24.7151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel KG, Gupta P, Harbach RH, Guida WC, Dou QP. Organic copper complexes as a new class of proteasome inhibitors and apoptosis inducers in human cancer cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2004;67:1139–1151. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2003.10.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel KG, Chen D, Orlu S, Cui QC, Miller FR, Dou QP. Clioquinol and pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate complex with copper to form proteasome inhibitors and apoptosis inducers in human breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2005;7 (6):R897–R908. doi: 10.1186/bcr1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez M, Arroyo M, Cerdan FJ, Munoz M, Martin MA, Balibrea JL. Serum and tissue trace metal levels in lung cancer. Oncology. 1989;46 (4):230–234. doi: 10.1159/000226722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou QP, Li B. Proteasome inhibitors as potential novel anticancer agents. Drug Resist Updates. 1999;2 (4):215–223. doi: 10.1054/drup.1999.0095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eatock MM, Schatzlein A, Kaye SB. Tumour vasculature as a target for anticancer therapy. Cancer Treat Rev. 2000;26:191–204. doi: 10.1053/ctrv.1999.0158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox SB, Gasparini G, Harris AL. Angiogenesis: pathological, prognostic, and growth-factor pathways and their link to trial design and anticancer drugs. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:278–289. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00323-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao G, Dou QP. N-terminal cleavage of Bax by calpain generates a potent proapoptotic 18-kDa fragment that promotes Bcl-2-independent cytochrome C release and apoptotic cell death. J Cell Biochem. 2000;80:53–72. doi: 10.1002/1097-4644(20010101)80:1<53::aid-jcb60>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel JM, Lacombe T, Carobbio S, Paquet N, Bisig R, Cox JA, Jaton JC. Zinc is required for the catalytic activity of the human deubiquitinating isopeptidase T. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13755–13766. doi: 10.1021/bi026096m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geraki K, Farguharson MJ, Bradley DA. Concentrations of Fe, Cu and Zn in breast tissue: a synchrotron XRF study. Phys Med Biol. 2002;47 (13):2327–2339. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/47/13/310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JA, Ward CL, Kopito RR. Aggresomes: a cellular response to misfolded proteins. J Cell Biol. 1998;143 (7):1883–1898. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim I, Kim CH, Kim JH, Lee J, Choi JJ, Chen ZA, Lee MG, Chung KC, Hsu CY, Ahn YS. Pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate and zinc inhibit proteasome-dependent proteolysis. Exp Cell Res. 2004;298 (1):229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labbe S, Thiele DJ. Pipes and wiring: the regulation of copper uptake and distribution in yeast. Trends Microbiol. 1999;7 (12):500–505. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(99)01638-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis-Piwowar KR, Milacic V, Chen D, Yang H, Zhao Y, Chan TH, Yan B, Dou QP. The proteasome as a potential target for novel anticancer drugs and chemosensitizers. Drug Resist Updates. 2006;9 (6):263–273. doi: 10.1016/j.drup.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazebnik YA, Kaufmann SH, Desnoyers S, Poirier GG, Earnshaw WC. Cleavage of poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase by a proteinase with properties like ICE. Nature. 1994;371:346–347. doi: 10.1038/371346a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes UG, Erhardt P, Yao R, Cooper GM. p53-dependent induction of apoptosis by proteasome inhibitors. J Biol Chem. 1997;272 (20):12893–12896. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.12893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malaguarnera L, Pilastro MR, DiMarco R, Scifo C, Renis M, Mazzarino MC, Messina A. Cell death in human acute myelogenous leukemic cells induced by pyrrolidinedithiocarbamate. Apoptosis. 2003;8 (5):539–545. doi: 10.1023/a:1025550726803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malemud CJ. Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) in health and disease: an overview. Front Biosci. 2006;11:1696–1701. doi: 10.2741/1915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchenko ND, Marchenko GN, Strongin AY. Unconventional activation mechanisms of MMP-26, a human matrix metalloproteinase with a unique PHCGXXD cysteine-switch motif. J Biol Chem. 2002;277 (21):18967–18972. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maverakis E, Fung MA, Lynch PJ, Draznin M, Michael DJ, Ruben B, Fazel N. Acrodermatitis enteropathica and an overview of zinc metabolism. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;56 (1):116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milacic V, Chen D, Ronconi L, Landis-Piwowar KR, Fregona D, Dou QP. A novel anticancer gold(III) dithiocarbamate compound inhibits the activity of a purified 20S proteasome and 26S proteasome in human breast cancer cell cultures and xenografts. Cancer Res. 2006;66 (21):10478–10486. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayak SB, Bhat VR, Upadhyay D, Udupa SL. Copper and ceruloplasmin status in serum of prostate and colon cancer patients. Indian J Physiol Pharmacol. 2003;47 (1):108–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlowski RZ, Dees EC. Applying drugs that affect the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway to the therapy of breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:1–7. doi: 10.1186/bcr460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvig C, Abrams MJ. Medicinal inorganic chemistry: introduction. Chem Rev. 1999;99 (9):2201–2204. doi: 10.1021/cr980419w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parodi FE, Mao D, Ennis TL, Bartoli MA, Thompson RW. Suppression of experimental abdominal aortic aneurysms in mice by treatment with pyrrolidine dithiocarbamate, an antioxidant inhibitor of nuclear factor-kappaB. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41 (3):479–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pink JJ, Wuerzberger-Davis S, Tagliarino C, Planchon SM, Yang X, Froelich CJ, Boothman DA. Activation of a cysteine protease in MCF-7 and T47D breast cancer cells during β-lapachone-mediated apoptosis. Exp Cell Res. 2000;255:144–155. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreck R, Meier B, Mannel DN, Droge W, Baeuerle PA. Dithiocarbamates as potent inhibitors of nuclear factor kappa B activation in intact cells. J Exp Med. 1992;175 (5):1181–1194. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.5.1181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seemuller E, Lupas A, Stock D, Lowe J, Huber R, Baumeister W. Proteasome from Thermoplasma acidophilum: a threonine protease. Science. 1995;268:579–582. doi: 10.1126/science.7725107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinobu LA, Jones SG, Jones MM. Sodium N-methyl-D-glucamine dithiocarbamate and cadmium intoxication. Acta Pharmacol Toxicol. 1984;54:189–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1984.tb01916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spataro V, Norbury C, Harris AL. The ubiquitin–proteasome pathway in cancer. Br J Cancer. 1998;77 (3):448–455. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida D, Ikeda Y, Nakazawa S. Quantitative analysis of copper, zinc and copper/zinc ratio in selected human brain tumors. J Neuro-Oncol. 1993;16 (2):109–115. doi: 10.1007/BF01324697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood DE, Newcomb EW. Cleavage of Bax enhances its cell death function. Exp Cell Res. 2000;256 (2):375–382. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]