Abstract

Object

Critical reductions in oxygen delivery (DO2) underlie the development of delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI) after subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH). If DO2 is not promptly restored then irreversible injury (i.e. cerebral infarction) may result. Hemodynamic therapies for DCI (i.e. induced hypertension and hypervolemia) aim to improve DO2 by raising cerebral blood flow (CBF). Red blood cell (RBC) transfusion may be an alternate strategy that augments DO2 by improving arterial oxygen content. We compared the relative ability of these three interventions to improve cerebral oxygen delivery, specifically their ability to restore DO2 to regions where it is impaired.

Methods

Comparison of three prospective physiologic studies utilizing PET imaging to measure global and regional CBF and DO2 before and after: 1) fluid bolus of 15 ml/kg normal saline (n=9); 2) raising mean arterial pressure 25% (n=12); 3) transfusing one unit of RBCs (n=17) in patients with aneurysmal SAH at risk for DCI. Response between groups in regions with low DO2 (< 4.5 ml/100g/min) was compared using repeated measures ANOVA.

Results

Groups were similar except that the fluid bolus cohort had more patients with symptoms of DCI and lower baseline CBF. Global CBF or DO2 did not rise significantly after any of the interventions, except after transfusion in patients with hemoglobin below 9g/dl. All three treatments improved CBF and DO2 to regions with impaired baseline DO2, with a greater improvement after transfusion (+23%) than hypertension (+14%) or volume loading (+10%); p<0.001. Transfusion also resulted in a non-significantly greater (47%) reduction in number of brain regions with low DO2 vs. fluid bolus (7%) and hypertension (12%), p=0.33.

Conclusions

Induced hypertension, fluid bolus, and blood transfusion all improve oxygen delivery to vulnerable brain regions at risk of ischemia after SAH. Transfusion appeared to provide at least comparable physiologic benefit to induced hypertension, especially amongst patients with anemia, but is associated with risks. The clinical significance of these findings remains to be established in controlled clinical trials.

Keywords: Subarachnoid Hemorrhage, Vasospasm, Intracranial, Brain Ischemia, Blood Transfusion, Cerebrovascular Circulation, Triple-H Therapy

INTRODUCTION

The major threat to neurological recovery for survivors of aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH) is the development of delayed cerebral ischemia (DCI). In association with arterial vasospasm, cerebral blood flow (CBF) falls below critical ischemic thresholds such that brain regions receive inadequate oxygen delivery (DO2) relative to metabolic demands.13;29 This may induce the development of ischemic neurological deficits, and if the impairment in DO2 is not promptly reversed, cerebral infarction with permanent disability may ensue.28 For this reason, the principal focus of managing DCI centers on improving CBF and DO2, especially to vulnerable regions where DO2 is already impaired.

The primary medical strategy to manage DCI has involved “Triple-H” (or hemodynamic) therapy, incorporating elements of hypervolemia, hypertension, and hemodilution.1 The goal of these interventions is to increase CBF and thereby restore DO2 to regions at risk for ischemia.27 While significant anecdotal evidence exists to support the ability of hemodynamic augmentation to reverse ischemic deficits,18;23 how each component impacts on CBF and DO2 has not been as well established.10;24 Induced hypertension (IH) appears to raise CBF most consistently in previous studies,5 but giving a fluid bolus has also been shown to improve CBF (and thereby DO2) to regions with low baseline flow.17

Hemodilution is no longer broadly utilized for DCI, as although it may improve CBF to a small extent related to reduced blood viscosity at lower hematocrit, the associated fall in arterial oxygen content (CaO2) actually threatens to impair not improve DO2. 11 This paradox of improved CBF but lower net DO2 exemplifies why DO2 and not CBF must be the outcome of interest in physiologic studies evaluating the benefits of interventions for DCI (especially those that manipulate hemoglobin levels). Interest has recently been raised in red blood cell (RBC) transfusion as a therapeutic modality that may increase cerebral DO2 in the presence of anemia;7;32 reductions in hemoglobin are common after SAH and have been consistently associated with worse outcome and more cerebral infarction.20;25;26

No studies have assessed the relative ability of transfusion to improve DO2 compared to the more traditional aspects of hemodynamic augmentation (i.e. hypertension and hypervolemia). We have employed a standardized brain imaging protocol to measure CBF and DO2 before and after therapeutic interventions (including IH, volume loading, and RBC transfusion) in patients with SAH.7;17 We sought to compare the effect of each of these interventions on DO2 as a physiologic surrogate of their ability to reduce the risk of cerebral ischemia. Specifically, we wanted to determine whether transfusion could augment DO2 to a comparable degree as IH (the clinical “gold standard”) and greater than a fluid bolus alone, particularly to vulnerable brain regions where DO2 was impaired at baseline.

METHODS

Patient and Study Selection

We collectively analyzed and compared patients enrolled in three separate but technically similar prospective clinical studies. Each utilized 15-oxygen positron emission tomography (15O-PET) imaging to measure CBF (and in the IH and transfusion studies also oxygen extraction fraction, OEF, and cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen, CMRO2) before and after the specified intervention. The trials are compared in Table 1. All enrolled patients with aneurysmal SAH from amongst the approximately 120 admitted to the neurosurgery service at our institution each year. Subjects were studied during the period of highest risk for vasospasm and DCI, between 4 and 14 days after SAH, and were enrolled once they met inclusion criteria for a specific study; allocation was not randomized.

Table 1.

Comparison of the three included studies

| Fluid Bolus (Hypervolemia) | Induced Hypertension | RBC Transfusion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shared inclusion criteria | Spontaneous SAH with ruptured cerebral aneurysm secured | ||

| Intervention | Normal saline 15 ml/kg Over 1 hour | Phenylephrine to raise MAP by 20–30% | 1 unit of Packed RBCs Over 1 hour |

| Physiologic Goal | Increase plasma volume by 10% | Increase mean arterial pressure at least 20% | Increase hemoglobin by at least 1 g/dl (approx 10%) |

| Specific inclusion criteria | New ischemic neurological deficits | Randomized to statin or placebo for 21 days | Anemia (Hb < 11 g/dl) |

| Specific exclusion criteria | Already on hemodynamic therapy for DCI | Other untreated aneurysms Pre-morbid statin therapy | Low-risk for DCI |

| Angiography | Performed within 12 hours of PET | PET planned on day 7 around time of routine angiogram | Optional (on day 7 and/or if symptoms) |

DCI = delayed cerebral ischemia; Hb = hemoglobin; MAP = mean arterial pressure; PET = positron emission tomography; RBCs = red blood cells

Studies shared much of the same patient selection criteria but varied in specific ways, as outlined in Table 1. In the first study, subjects were given a 15 ml/kg bolus of isotonic crystalloid to induce hypervolemia. The second study induced hypertension by raising mean arterial pressure (MAP) 20–30% above baseline (measured at the time of initial PET) with phenylephrine. The third transfused 1 unit of RBCs to raise hemoglobin and CaO2. Patients were excluded if CBF data could not be obtained from the PET studies for technical reasons (4 of 42 total subjects enrolled). The Human Research Protection Office and the Radioactive Drug Research Committee of Washington University approved each of these studies individually. Informed consent was obtained from each patient or their legally authorized surrogate. Results for a subset of the fluid bolus (n=7) and transfusion subjects (n=8) have been previously published separately 7;17 but additional patients (23 in total, including the entire IH cohort) and completely new analyses have been included in this comparison.

Intensive Care Unit Care and Data Collection

All patients with SAH were cared for in the Neurology/Neurosurgery Intensive Care Unit (NNICU) at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. Ruptured aneurysms were treated within 24 hours of admission in all cases. Patients were intubated for respiratory failure or if they were unable to maintain an adequate airway. All received enteral nimodipine. They were maintained in a euvolemic state by daily adjustments of intravenous fluids to keep ins and outs balanced, but prophylactic hypervolemia or hypertensive therapy was not employed. Anemia was generally tolerated (and transfusion generally reserved) until hemoglobin fell below 7 g/dl in the absence of significant angiographic or symptomatic vasospasm. New or worsening neurological deficits were promptly evaluated, and if no alternative cause was identified, patients underwent cerebral angiography and hemodynamic augmentation (primarily involving induced hypertension). They could also receive endovascular interventions for proximal angiographic vasospasm. In the absence of intervening symptoms, patients underwent screening cerebral angiography on or around day 7 after SAH.

Data collected on each subject included demographics and neurological status at the time of admission and study. 33 Admission CT was graded for amount of subarachnoid and intraventricular blood.4 The cerebral angiogram performed closest to each PET study was reviewed for the presence of arterial vasospasm, graded as mild, moderate, or severe in each vascular territory, based on interpretation of the attending neuroradiologist. If a given patient had at least one vessel with moderate-severe vasospasm, they were classified as having significant angiographic vasospasm. DCI was defined as the presence of new or worsened neurological deficits presumed to be ischemic after exclusion of other confounding etiologies, generally confirmed by the presence of vasospasm on cerebral angiography

Experimental Protocol

All PET studies were performed on either the Siemens/CTI ECAT EXACT HR 47 or HR+ scanners located in the NNICU.2;34 The NNICU PET Research Facility is equipped with the same life support and monitoring equipment available at each patient bed in the NNICU (i.e. continuous electrocardiography, MAP and O2 saturation monitoring, as well as intracranial pressure monitoring if required). An attending neurointensive care physician was present throughout each study. If a subject was already receiving hemodynamic augmentation (i.e. vasopressors, fluids) for vasospasm and/or ischemic deficits, this was continued throughout the study, both before and after the added intervention, with care taken to maintain a stable physiologic milieu. However, in the fluid bolus study, patients were taken to the PET scanner at the onset of suspected ischemic deficits (prior to angiography and institution of therapy). That is, the fluid bolus was given prior to induction of hypertensive therapy. No sedatives infusions were used in any patient and only opioids (not benzodiazepines or propofol) were given to maintain patient comfort during the duration of the study, on an as needed basis. RBCs administered in the transfusion group were provided by the hospital blood bank.

Image acquisition was performed as detailed previously to measure CBF, OEF, and CMRO2 (only CBF in the fluid bolus study).9 A transmission scan was also obtained and used for subsequent attenuation correction of emission scan data. After the first series of scans, the particular intervention (fluid bolus, hypertension, or transfusion) was administered (over one hour for transfusion and fluid bolus, phenylephrine was titrated over 15–30 minutes for IH) and scans were repeated immediately after. At the time of each scan, physiologic data were recorded including central venous pressure, when available (not measured in the IH study). Arterial blood was analyzed for hemoglobin level and CaO2 with each study.

PET Processing

All PET scans for each patient were co-registered and aligned to the initial baseline CBF study using Automated Image Registration software (AIR, Roger Woods, University of California, Los Angeles, CA).35 They were calibrated for conversion of PET counts to quantitative radiotracer concentrations, as previously described.30 Radioactivity in arterial blood was measured using an automated blood sampler. The arterial time-radioactivity curve recorded by the sampler was corrected for delay and dispersion using previously determined parameters.

Images were all then co-registered to a reference brain image and resliced so that data could be localized in Talairach atlas space. Global values for CBF, OEF, and CMRO2 were obtained using a standard image mask covering the brain from below the superior sagittal sinus down to the level of the pineal gland. Spherical regions of 10-mm diameter were placed in 36 predefined locations distributed across the major vascular territories bilaterally, as previously outlined.17;36 All images were reviewed and any regions corresponding to hematoma, visibly infarcted tissue, or ventricular system were excluded. Regional values were then calculated within each of the remaining spheres.

Data Analysis

The change in cerebral oxygen delivery (DO2, the product of CBF and CaO2), was our primary outcome measure both globally and regionally. We defined vulnerable regions as those with baseline DO2 < 4.5 ml O2/100g/min (equivalent to a CBF of 25 ml/100g/min at low-normal CaO2 of 18 ml/dL).7 We evaluated the response to each intervention (i.e. change in DO2) within all such regions. For patients in whom OEF was measured, we also determined which regions had OEF greater than or equal to 0.5 (as evidence of increased extraction compensating for insufficient DO2). Regions were then classified as oligemic if both DO2 was low and OEF was elevated. The thresholds used are conservative estimates guided by data from normal control subjects,14;16 and previous PET studies of patients with SAH both with and without vasospasm.3;12

We performed paired t-tests to evaluate the response to each intervention (on CBF, DO2, OEF, and CMRO2) within each individual study group, both globally and in vulnerable regions (i.e. low DO2 or oligemia). We then used a repeated measures ANOVA model to compare the effect of each intervention on global and regional DO2. A differential effect of the interventions on change in DO2 was considered present if the interaction statistic had a p value < 0.05. If a significant effect was found we then performed post-hoc testing to evaluate which intervention had greater impact on DO2. We controlled for potential imbalances between (non-randomized) groups by adjusting for covariates in the generalized linear model, including hemoglobin level and presence of angiographic vasospasm and/or DCI.

We specifically analyzed the response in the subgroup of patients with hemoglobin below 9 g/dl prior to transfusion (a threshold derived from a prior analysis of this cohort).8 This allowed us to evaluate the efficacy of transfusion in the subgroup with most severe anemia where it might most often be employed in clinical practice,19 without diluting any physiologic effect by including those at higher hemoglobin, whose benefit may be more marginal. We also analyzed and compared the subgroups of study patients with angiographic vasospasm, DCI, and low global DO2 (< 4.5 ml/100g/min) in each arm to provide an equivalent fair comparison, minimizing the imbalances that might have existed between groups as a whole.

Finally, we calculated the number of regions with low DO2 and oligemia in each patient, before and then after the intervention (to estimate any reduction in the volume or “burden” of under-oxygenated and oligemic brain tissue at highest risk for ischemia). We compared the proportion of these vulnerable regions before and after intervention using Wilcoxon signed rank testing and compared this response between the three groups using repeated measures ANOVA.

RESULTS

A total of 38 patients with aneurysmal SAH were studied, 9 received fluid bolus, 12 induced hypertension, and 17 blood transfusion. The demographics and clinical characteristics of the patients are outlined in Table 2. Subjects were similar between groups except all patients (by selection) in the fluid bolus study had neurological deficits presumed to be ischemic (of which only 2 did not have moderate-severe vasospasm on subsequent angiography). Patients in this group were younger and studied on average 2 days earlier in their course. A minority of patients in the IH and transfusion studies were already on hemodynamic therapy with vasopressors at the time of study compared to none (by design) in the fluid bolus cohort. However, a significant proportion in all three groups (33–78%) had significant vasospasm on angiography. Blood transfused had median storage duration of 31 days.

Table 2.

Comparison of subjects in three studies

| Fluid Bolus | Induced Hypertension | Transfusion | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 9 | 12 | 17 |

| Age, years (mean±SD) | 49.7 ± 7.2 | 63.8 ± 11.1 | 60.2 ± 12.1 |

| Sex, female (n/%) | 5 (56%) | 9 (75%) | 15 (88%) |

| Race, white (n/%) | 6 (67%) | 11 (92%) | 11 (65%) |

| GCS (admit) median, range | 14 (5–15) | 13 (3–15) | 13 (4–15) |

| Poor Grade (WFNS IV–V) | 2 (22%) | 5 (42%) | 6 (35%) |

| Modified Fisher 3 or 4 | 9 (100%) | 9 (75%) | 14 (82%) |

| Clip / Coil | 7 / 2 | 6 / 6 | 9 / 8 |

| Hydrocephalus | 3 (33%) | 11 (92%) | 13 (76%) |

| PET study on day# | 5.9 ± 2.0 | 7.6 ± 1.4 | 8.2 ± 3.4 |

| Angiographic vasospasm | 7 (78%) | 4 (33%) | 7 (41%) |

| Ischemic neuro deficits | 9 (100%) | 2 (17%) | 6 (35%) |

| On Pressors before PET | 0 (0%) | 2 (17%) | 6 (35%) |

| Length of Stay (days) | 20.7 ± 5.3 | 22.5 ± 10.3 | 26.4 ± 8.7 |

| DC Disposition (Home/Rehab/LTC) | 2 / 7 / 0 | 2 / 8 / 1 | 0 / 12 / 4 |

| Mortality | 0 | 1 (8%) | 1 (6%) |

GCS = Glasgow Coma Scale; LTC = long-term care; PET = positron emission tomography; WFNS = World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies’ Scale;

Physiologic data are compared between groups in Table 3. There was a small rise in MAP after fluid bolus and blood transfusion, but a much larger intentional 25% rise in the IH group related to titration of vasopressors. CVP was not available in the IH group but only a small rise was seen after both fluid bolus and transfusion; neither the baseline CVP nor rise in CVP after each intervention was significantly different between groups. Hemoglobin was stable pre- and post-intervention in the fluid bolus and IH groups but rose 13% after transfusion, while CaO2 rose 14%. Temperature, heart rate, and PaCO2 all remained stable. No patients had a rise in intracranial pressure during the study. Only one transient febrile response to transfusion was seen but no other transfusion reactions or complications associated with fluid bolus or IH (i.e. no cases of pulmonary edema, arrhythmias) were encountered.

Table 3.

Physiologic data before and after intervention

| Fluid Bolus | Induced Hypertension | Transfusion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| MAP (mm Hg) | 111.6±17 | 119.7±23 | 109.1±11 | 136.2±14a | 106.5±20 | 108.8±21b |

| CVP (mm Hg) | 7.9±5 | 8.9±5 | n/a | n/a | 10.3±3 | 12.7±3b |

| Hemoglobin (g/dl) | 10.9±2 | 10.7±2 | 9.9±2 | 9.8±2 | 9.1±1.2 | 10.3±1.1a |

| CaO2 (ml/dl) | 14.4±3 | 14.3±3 | 13.1±3 | 13.1±3 | 12.4±1.6 | 14.1±1.5a |

| PaCO2 (mm Hg) | 36.3±3 | 36.0±4 | 34.9±5 | 35.5±5 | 36.2±5 | 36.0±5 |

p < 0.001,

p < 0.05

CaO2 = arterial oxygen content; CVP = central venous pressure; MAP = mean arterial pressure; PaCO2 = arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide

Global PET measurements

Global CBF and DO2 were not significantly changed with any of the interventions (Table 4). There was a trend towards lower CBF after transfusion (p=0.10) and a lower OEF after IH (p=0.11). Cerebral metabolism (CMRO2) was unchanged. Evaluating only patients with angiographic vasospasm (7 in fluid bolus, 4 in IH, 7 in transfusion) there was still no change in global CBF or DO2 with any of the interventions and no differential response between treatments. Among patients with ischemic deficits (n=9, n=2, and n=6) only IH led to a small but significant rise in CBF (37.1±11 to 41.2±11, p=0.01) and DO2 (4.7±0.4 to 5.2±0.4, p=0.06) but ANOVA did not confirm superiority of this response over the other two interventions (likely due to small numbers). There were too few patients (n=5 overall) with low global CBF (below 25 ml/100g/min) to permit analysis of this subgroup. There were 12 patients with low global DO2 at baseline divided between the three cohorts. In this subgroup, transfusion resulted in a significantly larger rise in global DO2 than either IH or fluid bolus (+21% vs. +7% for IH and −7% for fluid bolus, p=0.02 by ANOVA).

Table 4.

Global PET measurements before and after intervention

| Fluid Bolus | Induced Hypertension | Transfusion | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| CBF | 34.4±10.6 | 34.8±12.6 | 43.7±16.4 | 45.2±15.7 | 46.6±12.7 | 42.9±10.1 |

| DO2 | 4.9±1.5 | 4.9±1.8 | 5.5±1.8 | 5.7±2.0 | 5.8±1.8 | 6.0±1.5 |

| OEF | n/a | n/a | 0.34±.0.11 | 0.29±0.06 | 0.39±0.14 | 0.36±0.10 |

| CMRO2 | n/a | n/a | 1.94±0.47 | 1.79±0.49 | 2.13±0.45 | 2.11±0.34 |

CBF, DO2, and CMRO2 are expressed in ml/100g/min

NB: OEF and CMRO2 were available for only 6 patients in the induced hypertension cohort and 12 patients in the transfusion cohort

CBF = cerebral blood flow, CMRO2 = cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen; DO2 = oxygen delivery, OEF = oxygen extraction fraction

Amongst the nine anemic patients with Hb<9 g/dl in the transfusion study, blood transfusion resulted in a significant rise in global DO2 (4.7±0.9 to 5.4±0.8, p=0.002) with no fall in CBF. Comparing the response to transfusion in these anemic patients to the response to fluid bolus and IH in all patients receiving those interventions, the 17% rise in global DO2 after transfusion was significantly better than the lack of improvement seen in the other two groups (p=0.015).

Regional PET Data

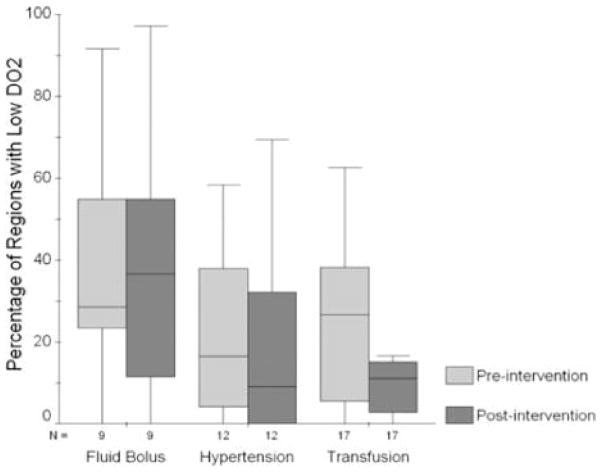

A total of 111 regions were excluded (62 for being in the ventricular system, 35 were within infarcts or edema, and 14 in regions of hematoma) leaving 1257 regions across 36 patients available for regional analysis. Low DO2 was present in 351 (28%), including 123 in fluid bolus group (41%), 99 in IH group (25%), and 129 in the transfusion cohort (23%). Low CBF was present in 117 regions (9%) including 62 of the fluid bolus, 44 in IH, and 11 in the transfusion group. Oligemia was present in 74 (11% of available regions), with 14 such regions in the IH group and 60 in the transfusion cohort. Figure 1 shows the proportion of brain regions with low DO2 per patient before and after each intervention. Transfusion was the only intervention able to significantly reduce (by 47%) the number of regions per patient with low DO2 (p=0.02 by Wilcoxon signed rank testing). However, this fall in vulnerable regions was not significantly greater than the 12% reduction with IH and 7% reduction after fluid bolus (p=0.33 for interaction).

Figure 1.

Mean percentage of brain regions with impaired oxygen delivery per patient before and after intervention in each study group.

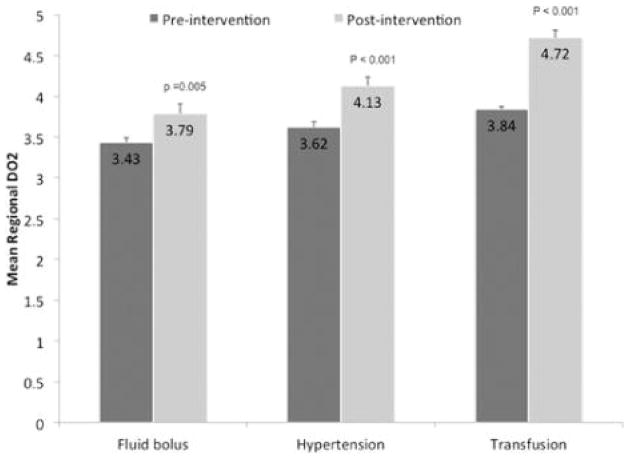

Vulnerable Regions

There was a significant rise in mean regional DO2 after each of the three interventions in regions classified as vulnerable based on low baseline DO2 (Figure 2). Transfusion resulted in a greater rise (+23%) in DO2 than both fluid bolus (+10%) and IH (+14%) with interaction p < 0.001 and p <0.001 for transfusion vs. both fluid bolus and hypertension by Tukey post-hoc testing. CBF also rose with all three interventions although, as expected, the rise was greater with fluid bolus and IH than with transfusion. Regional OEF fell from 0.45±0.11 to 033±0.10 with IH and from 0.55±0.16 to 0.46±.16 with transfusion (both p<0.001). The interaction between fall in OEF and group (IH vs. transfusion) was not significant. OEF was not measured in the fluid bolus study.

Figure 2.

Oxygen delivery to regions with low delivery at baseline before and after each intervention.

Most of the regions with CBF below 25 ml/100g/min were in the fluid bolus study (n=62 vs. n=44 IH, n=11 transfusion). Although CBF rose with each intervention, it was most marked after a fluid bolus (+28%) vs. 12% with IH and 8% with transfusion (not significant in post-hoc testing). There was also rise in DO2 to such regions after all three interventions (26% fluid bolus vs. 8% IH vs. 23% transfusion, interaction p=0.047).

Oligemia was present in only 14 regions in the hypertension study (6%) and 60 in the transfusion study (14%). There was a significant rise in DO2 within such regions after IH (34%) and transfusion (26%) with no difference between treatments. OEF also fell (by 0.19 with IH and by 0.13 with transfusion, p=0.26). This response resulted in resolution of oligemia in all cases in the IH cohort and 44 of 60 oligemic regions after transfusion.

DISCUSSION

Effect of Triple-H Therapy on CBF

For this exploratory analysis we combined data from three distinct but similarly designed prospective physiologic studies that utilized PET imaging to evaluate the effects of important hemodynamic interventions on cerebral oxygen delivery and utilization in patients with SAH. This allowed us to broadly compare the efficacy of induced hypertension (raising MAP by 25%) and volume loading (with an isotonic crystalloid bolus of 15 ml/kg), to transfusion of one unit of RBCs. The first two interventions form the core of triple-H therapy, used as the central medical management strategy to treat ischemic deficits related to vasospasm. It is presumed that they act to reverse or prevent progression of ischemia primarily through their ability to raise CBF, reversing critical reductions in DO2 to brain regions at risk for metabolic failure. Despite their widespread clinical use only a limited number of studies have investigated their effect on CBF to confirm this fundamental assumption. A recent systematic review of this evidence found that their effect on global or focal CBF was inconsistent.5 Few controlled studies have compared them with each other or evaluated their benefits relative to placebo.21 One small study used a regional CBF monitor to evaluate the response to hypertension and hypervolemia, as well as triple-H in combination.24 This found a 10–20% rise in focal CBF with IH (in response to a 50% increase in MAP) compared to no significant rise after hypervolemia (induced by 1–3L fluid boluses). The hemodilution resulting from fluid boluses actually may have reduced oxygen delivery, as estimated by a fall in brain tissue oxygen tension. Triple-H in combination did not lead to a greater rise in CBF than IH alone. None of these studies examined multiple regions, evaluating an effect of treatment in those brain areas at highest risk, as we have performed here.

Oxygen Delivery as a Physiologic Surrogate

We selected DO2 and not CBF as our primary outcome for two important reasons. Firstly, it would be impossible to fairly compare the physiologic benefits of hypertension and fluid bolus to that expected from transfusion using CBF alone. Blood transfusion increases hemoglobin and CaO2, and primarily in this manner augments tissue oxygen delivery (the product of flow and CaO2). Transfusion is not expected to improve CBF (except perhaps through an increase in blood volume and/or blood pressure), and may even reduce flow at higher hemoglobin levels, a trend we observed in this study that may relate to effects of increased blood viscosity.15

More importantly, it is DO2 and not CBF that is directly relevant to the development of tissue ischemia. Flow is only important in so far as it provides blood rich in substrates such as oxygen (carried on hemoglobin). Ischemia occurs not when CBF falls below a set threshold but when CBF is insufficient to provide adequate oxygen delivery to brain tissues, such that oxidative metabolism becomes impaired.31 We set our DO2 threshold at a level which corresponds to CBF of 25 ml/100g/min (the ischemic threshold has variably been measured between 17 and 25 ml/100g/min), at a low-normal CaO2.6 While this may not represent the threshold for cell death, it serves as a practical cut-off to define regions at risk for imminent ischemia. The use of elevated OEF as an additional marker of hemodynamic compromise (i.e. oligemia) may further refine our ability to define vulnerable regions, but this data was not available in the fluid bolus study, and so not the primary focus of this analysis. While we believe that DO2 is the primary physiologic surrogate for tissue viability in ischemia, we recognize that improvement in DO2 (as measured here) has not been validated as a marker of response to hemodynamic manipulation correlated with clinical outcomes.

Effect of Interventions on Oxygen Delivery

We found that none of the interventions had a significant impact on global DO2 in this small cohort of patients (apart from IH in patients with ischemic deficits, which increased global CBF and DO2, by 10%, and transfusion in those with hemoglobin below 9 g/dl, which increased global DO2 by 17%). This does not, however, negate their utility in treating DCI, as we would not require or expect interventions to increase flow or delivery averaged across all regions of the brain. It is most likely their ability to reverse regional reductions in DO2 (i.e. to vulnerable regions with low DO2 and oligemia) not their global impact that contributes to their clinical efficacy in reversing neurological deficits and preventing tissue progressing to infarction. It was reassuring, therefore, that we found a significant rise in both CBF and DO2 within such vulnerable regions with all three interventions (as shown in Figure 2). We also demonstrated that these interventions can reverse the state of low delivery and oligemia found at baseline. This may most meaningfully translate into protection against regional ischemia. One explanation for the variable and often negative results of previous trials examining CBF after induced hypertension and hypervolemia is that those studies often only measured global CBF (or in a single region), ignoring the possibility, demonstrated here, that interventions may be neutral globally but still have a positive impact in vulnerable regions.

Furthermore, we found that transfusion was more effective in improving regional DO2 than a fluid bolus and even more than raising blood pressure, with a trend to a greater reduction in vulnerable brain regions. A major contributing factor is that CBF did not fall within regions with low DO2 even as transfusion increased hematocrit; the long-standing concern has been that as viscosity rises at higher hematocrit levels, transfusion may impair flow. If this was the case, any benefit from raising CaO2 may be negated by the concomitant fall in CBF. If CBF remains stable (as seen here), transfusion will consistently raise DO2 10–20% per unit of blood (i.e. the amount that CaO2 rises). Conversely, induced hypertension (raising MAP by an average of 25%) did not result in an equivalent rise in CBF, either globally or even in vulnerable regions (where CBF/DO2 rose only 14% in response to a larger rise in cerebral perfusion pressure, CPP). This suggests that there is neither global nor even complete regional failure of autoregulatory responses, a vascular phenomenon upon which the physiologic benefit of IH rests (i.e. that a rise in CPP will improve CBF). While IH undoubtedly displays clinical efficacy in reversing deficits associated with cerebral vasospasm, our ability to explain this effect through an improvement in DO2 appears marginal. IH was able to lower OEF and reverse oligemia, and it may be that these highest-risk regions benefit preferentially due to focal loss of autoregulation and this improvement results in resolution of clinical deficits.

Utility of Fluid Bolus vs. Transfusion in Delayed Cerebral Ischemia

We have previously demonstrated the efficacy of a fluid bolus in reversing regional reductions in CBF despite no change in global CBF.17 This study extends those results with a larger cohort and now compares the observed response to that seen with other interventions for DCI. It may be reasonable to use a fluid bolus of 15 ml/kg (i.e. volume loading / transient hypervolemia) in patients with suspected ischemic deficits while other more durable interventions are being planned, including angiography (with angioplasty if possible for proximal vasospasm) and induced hypertension. Given the rapid redistribution of crystalloids out of the plasma compartment, it is unlikely that most of the immediate benefit we observed with a fluid bolus would last more than a few hours. We cannot comment on the delayed efficacy of fluid vs. IH vs. transfusion as this protocol did not include a PET scan at a later time point. The argument against repeated fluid boluses might be that although we saw an immediate rise in regional CBF, the improvement in DO2 was smaller. This is likely explained by the progressive hemodilution (with lowering of CaO2) that occurs with volume loading.24 Hemodilution attenuates the benefit of increased fluid administration for patients with SAH and ischemia. Blood transfusion provides both volume replacement that remains in the vascular compartment and improves CaO2, resulting in a larger and more durable effect on DO2. However, especially given the significant risks known to be associated with transfusion,22 we cannot suggest giving blood to patients with hemoglobin above 9–10 g/dl until further studies are performed to evaluate the optimal threshold and safety of transfusion in this population.

Limitations

There are a few significant limitations to this type of exploratory analysis. Our comparison of the three interventions was not based on randomization of a single cohort of SAH patients but on an uncontrolled retrospective review of distinct studies each with only a limited number of patients. This means that the patients studied in each trial were not entirely equivalent. However, we feel that the broad population each study was drawn from (i.e. aneurysmal SAH, risk of DCI) was fundamentally similar and management in the NNICU was standardized across all groups. Differences in inclusion criteria meant that the fluid bolus study included only symptomatic patients and the transfusion patents were all anemic introducing some heterogenity. However, even after controlling for these variables or examining patients of a certain type (e.g. only those with ischemic deficits or vasospasm), our results remain largely unchanged. Furthermore, by selecting regions with low DO2 across all patients and cohorts, we formed our primary analysis around a similar at-risk population (of brain regions) in each study. Nonetheless, without a properly controlled study comparing induced hypertension, fluid bolus, and RBC transfusion, firm comments on relative efficacy cannot be made.

Another potential confounder in comparing these interventions is that the “dose” of each might not be similar and so their exact response might similarly be different and hard to compare. It is impossible to meaningfully equalize the amount of fluid or blood that is equivalent to a given rise in blood pressure. However, we believe the size of the intervention in each study was clinically meaningful (i.e. similar to what would be used in clinical practice to manage DCI) and of comparable potency. In fact, we would argue that raise MAP by 25% should have at least equivalent potency than a single unit of RBCs (which only raise CaO2 by 15%) or a single fluid bolus (which might raise plasma volume by 10%). The finding that induced hypertension was no better than the other two modalities, even despite this uncertainty, provides some pause when considering which intervention best minimizes the risk of ischemia and infarction. Even if quantitative comparisons are inexact, the qualitative differences we have highlighted are hard to entirely discount.

Finally, our study lacks clinical outcome measures and so we cannot comment on the clinical efficacy of any of the interventions utilized. Regional DO2 is only a surrogate for the risk of ischemia, albeit one we feel is valid and important. While it seems intuitive that reversing critical reductions in DO2 would serve to minimize DCI and eventual infarction, this has not been clearly demonstrated. Nonetheless, we feel that one must first understand the physiologic effects of our interventions before testing them in clinical trials. We also only measured response (change in DO2) immediately after the intervention. Our findings therefore reflect only the immediate effects of each intervention. We cannot comment on how sustained or transient any benefit from a fluid bolus compared to induced hypertension or blood transfusion would be. It may be that raising MAP can be best sustained over the time period required to treat DCI, while the acute CBF-raising effects of a fluid bolus are rapidly dissipated. Whether the benefits of transfusion on DO2 are sustained is also unknown and forms the basis of an ongoing study.

CONCLUSIONS

We were able to broadly compare the efficacy of transfusion to a fluid bolus and induced hypertension for augmenting cerebral oxygen delivery to vulnerable brain regions in patients with SAH. We demonstrated that the transfusion of RBCs may be an equally or even more potent intervention than the traditional measures of treating DCI, such as raising blood pressure or giving volume, especially in more anemic patients or to vulnerable brain region at highest risk for ischemia. Any potential benefits must be weighed against the known risks of excessive or unnecessary blood transfusion. Direct comparative studies including those with clinical outcomes are required to define this relative efficacy and risk-benefit ratio. However, for the first time we have provided data that suggests transfusion may be a meaningful alternative or adjunct to hemodynamic augmentation.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: This work was supported by grants from the NIH/NINDS (5P50NS35966-10 to Dr. Diringer and P50NS55977 to Dr. Derdeyn), the AHA (10SDG3440008 to Dr. Dhar) and the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation (00956-0807-01 to Drs. Diringer and Dhar). Mr. Scalfani received support from grant UL1 RR024992 from the NIH-National Center for Research Resources (NCRR).

We thank Lennis Lich, Angela Shackelford, John Hood, and the cyclotron and intensive care unit staff for their invaluable assistance in performing this research and caring for these complex patients.

Footnotes

The authors have no other relevant financial disclosures.

Portions of this work were presented in poster form at the Society of Critical Care Medicine’s 40th Critical Care Congress on January 16, 2011.

DISCLOSURES:

The authors report no conflicts of interest concerning the materials or methods used in this study or the findings specified in this paper.

Reference List

- 1.Awad IA, Carter LP, Spetzler RF, Medina M, Williams FC., Jr Clinical vasospasm after subarachnoid hemorrhage: response to hypervolemic hemodilution and arterial hypertension. Stroke. 1987;18:365–372. doi: 10.1161/01.str.18.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brix G, Zaers J, Adam LE, Bellemann ME, Ostertag H, Trojan H, et al. Performance evaluation of a whole-body PET scanner using the NEMA protocol. National Electrical Manufacturers Association. J Nucl Med. 1997;38:1614–1623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carpenter DA, Grubb RL, Jr, Tempel LW, Powers WJ. Cerebral oxygen metabolism after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1991;11:837–844. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1991.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Claassen J, Bernadini GL, Kreiter K, Bates J, Du YE, Copeland D, et al. Effect of cisternal and ventricular blood on risk of delayed cerebral ischemia after subarachnoid hemorrhage: the Fisher scale revisited. Stroke. 2001;32:2012–2020. doi: 10.1161/hs0901.095677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dankbaar JW, Slooter AJ, Rinkel GJ, Schaaf IC. Effect of different components of triple-H therapy on cerebral perfusion in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2010;14:R23. doi: 10.1186/cc8886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Darby JM, Yonas H, Marks EC, Durham S, Snyder RW, Nemoto EM. Acute cerebral blood flow response to dopamine-induced hypertension after subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:857–864. doi: 10.3171/jns.1994.80.5.0857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dhar R, Zazulia AR, Videen TO, Zipfel GJ, Derdeyn CP, Diringer MN. Red blood cell transfusion increases cerebral oxygen delivery in anemic patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2009;40:3039–3044. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.556159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dhar R, Zazulia AR, Videen TO, et al. Transfusion may be more effective at improving cerebral oxygen delivery after subarachnoid hemorrhage at lower hemoglobin levels. Neurocrit Care. 2010;13:S12. (Abstract) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diringer MN, Aiyagari V, Zazulia AR, Videen TO, Powers WJ. Effect of hyperoxia on cerebral metabolic rate for oxygen measured using positron emission tomography in patients with acute severe head injury. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:526–529. doi: 10.3171/jns.2007.106.4.526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Egge A, Waterloo K, Sjoholm H, Solberg T, Ingebrigtsen T, Romner B. Prophylactic hyperdynamic postoperative fluid therapy after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage: a clinical, prospective, randomized, controlled study. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:593–605. doi: 10.1097/00006123-200109000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ekelund A, Reinstrup P, Ryding E, Andersson AM, Molund T, Kristiansson KA, et al. Effects of iso- and hypervolemic hemodilution on regional cerebral blood flow and oxygen delivery for patients with vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 2002;144:703–712. doi: 10.1007/s00701-002-0959-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frykholm P, Andersson JL, Langstrom B, Persson L, Enblad P. Haemodynamic and metabolic disturbances in the acute stage of subarachnoid haemorrhage demonstrated by PET. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;109:25–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0404.2003.00174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grubb RL, Jr, Raichle ME, Eichling JO, Gado MH. Effects of subarachnoid hemorrhage on cerebral blood volume, blood flow, and oxygen utilization in humans. J Neurosurg. 1977;46:446–453. doi: 10.3171/jns.1977.46.4.0446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hatazawa J, Fujita H, Kanno I, Satoh T, Iida H, Miura S, et al. Regional cerebral blood flow, blood volume, oxygen extraction fraction, and oxygen utilization rate in normal volunteers measured by the autoradiographic technique and the single breath inhalation method. Ann Nucl Med. 1995;9:15–21. doi: 10.1007/BF03165003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hudak ML, Koehler RC, Rosenberg AA, Traystman RJ, Jones MD., Jr Effect of hematocrit on cerebral blood flow. Am J Physiol. 1986;251:H63–H70. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.1.H63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito H, Kanno I, Fukuda H. Human cerebral circulation: positron emission tomography studies. Ann Nucl Med. 2005;19:65–74. doi: 10.1007/BF03027383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jost SC, Diringer MN, Zazulia AR, Videen TO, Aiyagari V, Grubb RL, et al. Effect of normal saline bolus on cerebral blood flow in regions with low baseline flow in patients with vasospasm following subarachnoid hemorrhage. J Neurosurg. 2005;103:25–30. doi: 10.3171/jns.2005.103.1.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kassell NF, Peerless SJ, Durward QJ, Beck DW, Drake CG, Adams HP. Treatment of ischemic deficits from vasospasm with intravascular volume expansion and induced arterial hypertension. Neurosurgery. 1982;11:337–343. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198209000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kramer AH, Diringer MN, Suarez JI, Naidech AM, Macdonald RL, Leroux P. Red blood cell transfusion in patients with subarachnoid hemorrhage: a multidisciplinary North American survey. Crit Care. 2011;15:R30. doi: 10.1186/cc9977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kramer AH, Zygun DA, Bleck TP, Dumont AS, Kassell NF, Nathan B. Relationship Between Hemoglobin Concentrations and Outcomes Across Subgroups of Patients with Aneurysmal Subarachnoid Hemorrhage. Neurocrit Care. 2008 doi: 10.1007/s12028-008-9171-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lennihan L, Mayer SA, Fink ME, Beckford A, Paik MC, Zhang H, et al. Effect of hypervolemic therapy on cerebral blood flow after subarachnoid hemorrhage : a randomized controlled trial. Stroke. 2000;31:383–391. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.2.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marik PE, Corwin HL. Efficacy of red blood cell transfusion in the critically ill: a systematic review of the literature. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:2667–2674. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181844677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller JA, Dacey RG, Jr, Diringer MN. Safety of hypertensive hypervolemic therapy with phenylephrine in the treatment of delayed ischemic deficits after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 1995;26:2260–2266. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.12.2260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Muench E, Horn P, Bauhuf C, Roth H, Philipps M, Hermann P, et al. Effects of hypervolemia and hypertension on regional cerebral blood flow, intracranial pressure, and brain tissue oxygenation after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1844–1851. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000275392.08410.DD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naidech AM, Drescher J, Ault ML, Shaibani A, Batjer HH, Alberts MJ. Higher hemoglobin is associated with less cerebral infarction, poor outcome, and death after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:775–779. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000232662.86771.A9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Naidech AM, Jovanovic B, Wartenberg KE, Parra A, Ostapkovich N, Connolly ES, et al. Higher hemoglobin is associated with improved outcome after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:2383–2389. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000284516.17580.2C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Origitano TC, Wascher TM, Reichman OH, Anderson DE. Sustained increased cerebral blood flow with prophylactic hypertensive hypervolemic hemodilution (“triple-H” therapy) after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:729–739. doi: 10.1097/00006123-199011000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Powers WJ, Grubb RL, Jr, Baker RP, Mintun MA, Raichle ME. Regional cerebral blood flow and metabolism in reversible ischemia due to vasospasm. Determination by positron emission tomography. J Neurosurg. 1985;62:539–546. doi: 10.3171/jns.1985.62.4.0539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Powers WJ, Grubb RL, Darriet D, Raichle ME. Cerebral blood flow and cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen requirements for cerebral function and viability in humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1985;5:600–608. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1985.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Raichle ME, Martin WR, Herscovitch P, Mintun MA, Markham J. Brain blood flow measured with intravenous H2(15)O. II: Implementation and validation. J Nucl Med. 1983;24:790–798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siesjo BK. Pathophysiology and treatment of focal cerebral ischemia. Part I: Pathophysiology. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:169–184. doi: 10.3171/jns.1992.77.2.0169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith MJ, Stiefel MF, Magge S, Frangos S, Bloom S, Gracias V, et al. Packed red blood cell transfusion increases local cerebral oxygenation. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1104–1108. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000162685.60609.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Teasdale GM, Drake CG, Hunt W, Kassell N, Sano K, Pertuiset B, et al. A universal subarachnoid hemorrhage scale: report of a committee of the World Federation of Neurosurgical Societies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1988;51:1457. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.51.11.1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wienhard K, Dahlbom M, Eriksson L, Michel C, Bruckbauer T, Pietrzyk U, et al. The ECAT EXACT HR: performance of a new high resolution positron scanner. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1994;18:110–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Woods RP, Cherry SR, Mazziotta JC. Rapid automated algorithm for aligning and reslicing PET images. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16:620–633. doi: 10.1097/00004728-199207000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yundt KD, Grubb RL, Jr, Diringer MN, Powers WJ. Autoregulatory vasodilation of parenchymal vessels is impaired during cerebral vasospasm. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1998;18:419–424. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199804000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]