Abstract

Background

The efficacy of genetic testing for diabetes risk to motivate behavior change for diabetes prevention is currently unknown.

Purpose

This paper presents key issues in the design and implementation of one of the first randomized trials (the Genetic Counseling/Lifestyle Change for Diabetes Prevention Study) to test whether knowledge of diabetes genetic risk can motivate patients to adopt healthier behaviors.

Methods

Because individuals may react differently to receiving ‘higher’ vs ‘lower’ genetic risk results, we designed a 3-arm parallel group study to separately test the hypotheses that: (1) patients receiving ‘higher’ diabetes genetic risk results will increase healthy behaviors compared to untested controls, and (2) patients receiving ‘lower’ diabetes genetic risk results will decrease healthy behaviors compared to untested controls. In this paper we describe several challenges to implementing this study, including: (1) the application of a novel diabetes risk score derived from genetic epidemiology studies to a clinical population, (2) the use of the principle of Mendelian randomization to efficiently exclude ‘average’ diabetes genetic risk patients from the intervention, and (3) the development of a diabetes genetic risk counseling intervention that maintained the ethical need to motivate behavior change in both ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ diabetes genetic risk result recipients.

Results

Diabetes genetic risk scores were developed by aggregating the results of 36 diabetes-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms. Relative risk for type 2 diabetes was calculated using Framingham Offspring Study outcomes, grouped by quartiles into ‘higher’, ‘average (middle two quartiles)’ and ‘lower’ genetic risk. From these relative risks, revised absolute risks were estimated using the overall absolute risk for the study group. For study efficiency, we excluded all patients receiving ’average’ diabetes risk results from the subsequent intervention. This post randomization allocation strategy was justified because genotype represents a random allocation of parental alleles (‘Mendelian randomization’). Finally, because it would be unethical to discourage participants to participate in diabetes prevention behaviors, we designed our two diabetes genetic risk counseling interventions (for ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ result recipients) so that both groups would be motivated despite receiving opposing results.

Limitations

For this initial assessment of the clinical implementation of genetic risk testing we assessed intermediate outcomes of attendance at a 12-week diabetes prevention course and changes in self-reported motivation. If effective, longer term studies with larger sample sizes will be needed to assess whether knowledge of diabetes genetic risk can help patients prevent diabetes.

Conclusions

We designed a randomized clinical trial designed to explore the motivational impact of disclosing both higher than average and lower than average genetic risk for type 2 diabetes. This design allowed exploration of both increased risk and false reassurance, and has implications for future studies in translational genomics.

Introduction

The contribution of heritable factors to the development of type 2 diabetes (T2D) has been estimated to be as high as 40% [1]. With continuing advances in ‘next-generation’ genetic sequencing technologies, increased ability to identify rare risk loci, and the identification of alternative heritable factors (such as copy number variation, epigenetic marks),we are now poised on the threshold of applying personalized genetic risk information to the clinical management of diabetes [2,3]. Given the increased costs, uncertain efficacy, and potential for adverse impact of such testing, randomized clinical trials are needed for rigorous evaluation of the impact of applied genetic testing on patient behavior and on clinical management [4–6].

One potential role for diabetes genetic testing may be to motivate patients to adopt healthy behaviors to prevent T2D [7]. Lifestyle modification (such as increased exercise and sustained dietary changes to achieve >7% weight loss) has been conclusively demonstrated in several studies to significantly reduce T2D incidence among patients at increased phenotypic risk [8–10]. However, translation of these results into clinical practice has been limited by difficulty in motivating patients to adopt and sustain the behavioral changes necessary to prevent diabetes [11,12].

Recent advances in genetic epidemiology have now identified over three dozen loci associated with increased T2D risk [13]. It is not known whether communicating personal diabetes genetic risk information can be used in clinical practice to increase and sustain patient motivation effectively. Conversely, genetic risk assessment of phenotypically at-risk patients raises the paradox that testing often identifies individuals at relatively low genetic risk [14]. Such ‘lower’ genetic risk information could inappropriately reassure individuals who would clearly benefit from lifestyle changes based on phenotype.

We designed a randomized clinical trial—The Genetic Counseling/Lifestyle Change for Diabetes Prevention (GC/LC) Study—to evaluate the impact of T2D genetic counseling on behavior change among patients who are aware that they are at increased phenotypic risk for diabetes. Funded by the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), our study is specifically designed to test two separate hypotheses in comparison to individuals randomized to no genetic testing: (1) individuals with ‘higher’ diabetes genetic risk would be more motivated to sustain lifestyle changes; and (2) individuals with ’lower’ diabetes genetic risk would be less motivated to sustain lifestyle changes.

In this report, we describe important study design decisions related to: (1) implementing an individualized diabetes genetic risk score, (2) creating an allocation scheme based on the novel application of ‘Mendelian randomization’ to exclude the majority of individuals who fall into a relatively narrow ‘average’ diabetes genetic risk range, and (3) designing an ethical genetic counseling intervention to motivate participants regardless of their genetic risk score.

Methods

Patient eligibility and recruitment

We enrolled patients at high risk for T2D based on phenotypic criteria by identifying individuals in our clinical network with the metabolic syndrome (MetS; defined as meeting at least three of five of the following clinical criteria: fasting glucose ! 100 mg/dl, waist circumference>35 in (women) or>40 in (men), HDL cholesterol <50 mg/dl (women) or<40 mg/dl (men), triglycerides !150 mg/dl, and blood pressure ! 130/85 mmHg or prescribed antihypertensive medication) [15]. Patients in this source population were predominantly white (79%), with mean age 56.5 (”14) years, and evenly divided between men and women. National data indicate that patients with MetS have a 3- to almost 30-fold increased diabetes incidence compared to similar patients without MetS [16,17]. MetS has similar sensitivity (but lower specificity) than the more burdensome oral glucose tolerance test [18] for identifying individuals at risk for T2D and has the distinct advantages of using readily available clinical measures and of identifying a larger at-risk patient population (47 million in the US with MetS [19]), making this approach more readily applicable to the ‘real world’ setting.

Potentially eligible study participants were identified initially through automated medical record review using a previously validated algorithm that had 73% sensitivity and 91% specificity for identifying patients with MetS [20]. Eligibility of potential participants was then verified using a manual medical record review and, with permission from the patient's primary care provider, confirmed via a brief telephone screen.

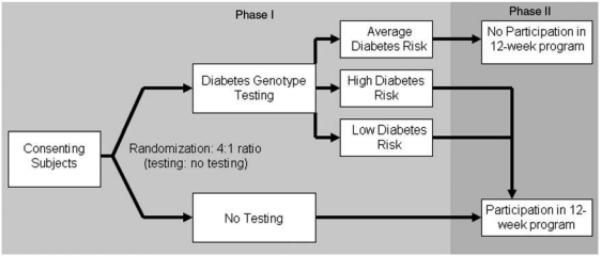

Study schema—Phase 1

Our protocol was implemented in two phases (Figure 1). In Phase 1, we enrolled and consented eligible participants to the GC/LC Study. At this first visit, all participants completed baseline surveys to assess baseline diabetes risk perception and current motivation to change diabetes-related health behaviors. After survey completion, participants were randomized in a 4:1 ratio to diabetes genetic risk testing vs no testing. The larger proportion of participants allocated to genetic testing was necessary in order to identify sufficient numbers of patients in the top and bottom risk quartiles (‘higher’ and ‘lower’ diabetes genetic risk) for the more resource-intensive Phase 2. Participants found to have ‘average’ diabetes genetic risk results after genotyping were excluded from Phase 2. These individuals received their diabetes genetic test results directly from the principal investigator and were advised to follow up with their primary care physicians to address modifiable risk factors.

Figure 1.

Study schema: Phase 1 (2-stage randomization) and Phase 2 (12-week diabetes prevention curriculum)

Study schema—Phase 2

Participants allocated to Phase 2 included the ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ diabetes genetic risk result recipients (intervention patients) and the untested controls. These patients returned for a second research visit once genotyping was completed (3–4 weeks after first research visit). At this visit, intervention patients received their diabetes genetic risk results and underwent a 15-min individual diabetes genetic risk counseling session. After the counseling session, intervention patients completed the repeat survey and were scheduled for the 12-week diabetes prevention course. Control patients attending the second research visit completed the repeat survey and were scheduled for the 12-week prevention course. In the weeks following completion of the curriculum, participants returned for their third and final research visit and completed the third survey. Thus, apart from the diabetes genetic risk counseling session, intervention and control patients in Phase 2 received identical exposure to diabetes risk education and to study staff over the approximately 4 months of their study participation.

Creating a diabetes genetic risk score

For the GC/LC Study we used 36 validated SNPs independently associated with T2D [13]. At each locus, an individual can have 0, 1, or 2 risk-associated alleles. We created a single diabetes genotype risk score by summing up the total number of risk alleles (range 0–72). Prior research has shown that for risk ranking simple summing provides substantially similar results as various approaches that weight individual alleles according to effect size [21].

To calculate each participant's diabetes genetic risk status, we first determined relative diabetes genetic risks based on the Framingham Offspring Study. This longitudinal cohort with biennial research visits represents a well-phenotyped population similar to the patients in our clinical network [13,22]. After excluding patients with diabetes at baseline, there were 3471 genotyped individuals in the Framingham Offspring Study who were followed for a mean of 8.2 (” 1.0) years in whom 446 cases of diabetes were diagnosed [13]. Among patients with genotype risk scores>38 (‘higher’ risk), 17.9% developed diabetes (46% relative increase compared to ‘average’ risk, scores 34–38). Among patients with genotype risk scores<34 (“lower” risk), 9.9% developed diabetes (18% relative decrease compared to ‘average’ risk patients). The ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ groups each comprised approximately 25% of the genotyped population (Table 1). These results were unchanged when the analysis was restricted to participants meeting criteria for MetS (n ¼ 1263).

Table 1.

Relative risk for type 2 diabetes by diabetes genotype risk score derived from the Framingham Offspring Study

| Risk category | Risk score | Cohort total (N) | Distribution by risk category | Number with T2D | Percentage with T2D |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | < 34 | 905 | 0.26 | 90 | 9.9% |

| Average | 34-38 | 1804 | 0.52 | 220 | 12.2% |

| Higher | > 38 | 762 | 0.22 | 136 | 17.9% |

T2D, Type 2 diabetes mellitus.

For the GC/LC Study, we provided our study participants with an overall estimate of their risk for developing diabetes that combined their known phenotypic risk (based on MetS) with their measured genetic risk (derived from the Framingham Offspring Study data). Phenotypic risk for our study cohort was determined using data from our own hospital primary care practices [20]. Based on an analysis of 3-year diabetes incidence among patients with MetS, we estimated an 11% risk of developing diabetes over the next 3 years for our overall study population. Applying the relative risks determined using the Framingham Offspring Study data (46% relative increase for the ‘higher’ and 18% relative decrease for the ‘lower’ risk groups), we estimated that patients with ‘higher’ genetic risk results had a 3-year diabetes risk of 17% and patients with ‘lower’ genetic risk results had a 3-year diabetes risk of 9%.

Mendelian randomization and post-randomization allocation

Since roughly 50% of genotyped individuals fall within the relatively narrow numeric range of‘ average’ genetic risk, we chose a post-randomization allocation strategy that excluded ‘average’ genetic risk patients in order to substantially reduce the size and cost of Phase 2 (two further research visits and the 12-week diabetes prevention group sessions) without reducing the trial's power to test our two study hypotheses. The rationale for this post-randomization allocation was based on the concept of ‘Mendelian randomization.’

In classic clinical trial design, post-randomization allocation to study arm is forbidden because the criteria used for allocation may introduce confounding and thereby undermine the benefit of randomization. Mendelian randomization is a term coined to describe the concept that a given individual's genotype represents the random allocation of paternal and maternal alleles [23]. This concept has been used to support observational data analyses [24–26]. The GC/LC Study represents one of the first examples of this concept being used to increase the efficiency of a randomized trial. Since the genetic factors (in this case, alleles associated with diabetes) are not believed to be causally associated with the primary study outcomes (such as program attendance behavior), the diabetes genotype risk score acts as an instrumental variable that was assigned randomly at gametogenesis. In this context, post-randomization allocation to study arm does not undermine the random allocation of risk SNPs within study arms.

Design of genetic counseling intervention

The goals of the 15-min genetic counseling session were to explain the basic concept of genetic testing, present participants with their diabetes genotype score, and explain how their test results modified their phenotypically estimated risk. Participants received a one-page printed report that listed their results for each SNP tested and their total score. The score was also interpreted as conveying ‘higher’ or ‘lower’ diabetes genetic risk. This report was used as the basis for ‘personalized’ diabetes genetic risk counseling. To graphically represent risk to the intervention patients, we first presented a diagram to illustrate the combined influence of genetic (non-modifiable) and environmental (modifiable) factors. The added risk information generated from the genetic testing results was communicated to patients using the visual concept of a balance scale, in which the individual's 3-year absolute diabetes risk was either increased or decreased based on the additional information provided by their diabetes genetic risk assessment (for example, the scale tipped from 11% absolute 3-year risk to 17% absolute risk among patients with ‘higher’ genetic risk results). The initial development of the counseling session and visual materials was piloted using cognitive interviews with individuals who would have met eligibility criteria for the main study [27].

A key ethical consideration in our intervention development was that the diabetes genetic risk counseling session should be designed to avoid discouraging phenotypically and genetically highrisk patients from participating in a diabetes prevention program. Thus, the genetic counseling intervention had to be structured so that both ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ diabetes genetic risk result recipients would be motivated to make behavior changes. Accordingly, ‘higher’ diabetes risk result disclosure focused on the need to adopt lifestyle changes to counterbalance the increased diabetes genetic risk, whereas ‘lower’ diabetes risk result disclosure emphasized the greater relative contribution of modifiable, non-genetic risk factors to the individual's overall risk for diabetes. The goal was to avoid discouraging ‘higher’ diabetes risk recipients who might feel a sense of genetic fatalism while avoiding in ‘lower’ diabetes genetic risk recipients the sense of being protected from developing diabetes [28].

Choice of study outcomes

For rigorous assessment of the efficacy of the genetic testing and counseling, all participants in Phase 2 were enrolled into a 12-week Group Lifestyle Balance diabetes prevention curriculum modeled after the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP). This format was developed by Seidel et al. and first implemented in patients with MetS [29]. The curriculum provided educational content (such as identifying healthy eating habits, planning an exercise program) and also used motivational tools (dietary logs, weekly weigh-ins) to initiate behavior changes associated with diabetes prevention. Each 12-week program was conducted by clinical staff who were unaware of participants’ genetic risk test results. Although we could not blind patients to their randomization status—genetic testing or no testing—we instructed the group session educators to request that participants did not disclose their results to the group. To assess the adequacy of masking, we asked the group leaders to predict allocation status for all group participants after completion of the 12-week curriculum.

Our primary study outcomes were the number of 12-week program sessions attended (behavior) and changes in self-reported readiness to adopt the behavioral changes recommended by the diabetes prevention program (motivation). Secondary outcomes included objective measures of weight change before and after the 12-week session and number of weekly exercise and dietary log books turned in during the 12-week session.

Surveys administered at the baseline and follow-up research visits included: Diabetes Risk Perception [30], Stage of Change for a Low Fat Diet [31], Stage of Change for Exercise [32], and Stage of Change for Weight Loss [33]. The three Stage of Change instruments are each validated measures designed to assess motivation by classifying respondents into one of five stages (precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, or maintenance) for each of the three behavioral domains (following a low-fat diet, exercising, and losing weight) related to diabetes prevention. For example, the Stage of Change for Exercise instrument asks: ‘Please describe your current exercise behavior,’ with five choices [Currently, I do not exercise and I do not intend to start exercising in the next 6 months; Currently, I do not exercise but I am thinking about starting to exercise in the next 6 months; Currently, I exercise some but not regularly; Currently, I exercise regularly but I have only begun doing so within the last 6 months; and Currently, I exercise regularly and have done so for longer than 6 months] corresponding to the five stages of change.

Sample size and power calculation

A sample size of 90 participants (30 ‘higher’, 30 ‘lower’ diabetes genetic risk and 30 controls) was planned to allow sufficient power to demonstrate clinically meaningful results across both behavioral and self-reported outcomes of interest. Based on the prior experience of our diabetes center in delivering 12-week diabetes prevention courses, we also accounted for a 10% loss-to-follow-up rate when calculating power. Assuming the mean number of visits among controls was 8.5 based on prior experience at our center (unpublished data) and the standard deviation was 2, the study was of sufficient sample size to detect a 20% difference (1.7 difference in number of visits between comparison groups) with 97% power with two-sided probability of 0.05 or less. The change in motivation for each patient was categorized as increased, no change, and decreased, based on responses to each of the three Stages of Change instruments (low fat diet, exercise, weight loss). The study had 90% power to show a difference between 55% positive change vs 90% positive change in motivation between arms and 80% power to show a difference between 60% positive change vs 90% positive change in motivation.

Given the relatively small study size, our analysis plan included provision to control for any differences in baseline characteristics using multivariate modeling when examining outcomes by allocation status.

Discussion

We had to address both ethical and logistic design considerations when implementing a randomized trial of diabetes genetic risk testing and counseling among patients at increased phenotypic risk for type 2 diabetes.

Although there are no published clinical trials of diabetes genetic risk testing, several prior studies have examined whether family history can motivate lifestyle change. These small studies focused on intermediate or surrogate endpoints and have shown mixed results [6,34,35]. Because individuals perceive ‘personal’ genetic risk differently to their family history [27], it was important to assess the impact of such testing using a rigorous controlled study design. Moreover, unlike family history, where the response is either ‘yes’ (with varying degrees of increased risk) or ‘no’ (perceived as ‘no increased risk’), diabetes genetic risk testing can return not only ‘increased’ but also ‘decreased’ risk results. For this reason, we determined that it was necessary to assess both the potential benefit (improved motivation) and potential risk (false reassurance or genetic fatalism) from such testing.

In designing our study, we made the following important decisions with the goal of maximizing the validity and generalizability of our results:

We randomized to genetic testing vs no genetic testing to capture the most relevant clinical question, which is: ‘Among patients willing to be tested, will testing have a clinical impact?’

We separately evaluated the impact of ‘higher’ and ‘lower’ diabetes genetic risk results relative to the untested controls to disentangle the potentially counteracting impact of these different results on the overall impact of testing.

We used post-randomization allocation justified by the concept of Mendelian randomization to efficiently exclude nearly 50% of tested patients with ‘average’ results from the resource-intensive Phase 2.

We created a clinically implementable diabetes relative risk score based on the most up-to-date set of genetic variants associated with type 2 diabetes as of July 2010. This was achieved by combining relative genetic risk calculated from a finely phenotyped research cohort (Framingham) with a phenotypic risk estimation calculated from the clinical population from which research patients were recruited.

We created a genetic counseling intervention that in its relative brevity and explicit communication goals is responsive to the time demands and limited resources that would be expected in the real world setting.

We tailored our genetic counseling intervention so as not to undermine motivation in patients at high phenotypic risk for diabetes.

Randomized clinical trials have convincingly shown that increased physical activity and dietary modifications leading to sustained weight loss significantly reduce diabetes risk among patients with pre-diabetes or MetS. However, successful clinical implementation of these lifestyle changes has been limited. Given the ongoing diabetes epidemic, interventions to increase adoption of healthy lifestyle changes among high risk patients are urgently needed. In this ‘dawn of the genomic era’ [36,37], it is imperative to establish the evidence base to guide the clinical application of genetic testing for common chronic diseases such as type 2 diabetes [38] given the rise of direct-to-consumer advertising by commercial companies [39], the eagerness with which many clinicians embrace new technology, and the increased cost of additional testing. The GC/LC study was designed to begin establishing this evidence base for future practice.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was funded by NIDDK R21 DK84527-01. Dr Meigs received support from NIDDK K24 DK080140. ClinicalTrials. gov identifier: NCT01034319.

Grant Funding: NIDDK R21 DK84527-01; NIDDK K24 DK080140

References

- 1.Kaprio J, Tuomilehto J, Koskenvuo M, et al. Concordance for type 1 (insulin-dependent) and type 2 6 RW Grant et al. Clinical Trials. 2011;00:1–7. [Google Scholar]; diabetes mellitus in a population-based cohort of twins in Finland. Diabetologia. 1992;35:1060–7. doi: 10.1007/BF02221682. http://ctj.sagepub.com(non-insulin-dependent) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sudmant PH, Kitzman JO, Antonacci F, et al. Science. 2010;330:641–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1197005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durbin RM, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DL, et al. 1000 Genomes Project C. Nature. 2010;467:1061–73. [Google Scholar]

- 4.McBride CM, Koehly LM, Sanderson SC, Kaphingst KA. The behavioral response to personalized genetic information: Will genetic risk profiles motivate individuals and families to choose more healthful behaviors? Annu Rev Public Health. 2010;31:89–103. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McBride CM, Bowen D, Brody LC, et al. Future health applications of genomics: Priorities for communication,behavioral, and social sciences research. Am J Prev Med. 2010;38:556–65. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pijl M, Timmermans DR, Claassen L, et al. Impact of communicating familial risk of diabetes on illness perceptions and self-reported behavioral outcomes: A randomized controlled trial. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:597–9. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant RW, Hivert M, Pandiscio JC, et al. The clinical application of genetic testing in type 2 diabetes: A patient and physician survey. Diabetologia. 2009;52:2299–305. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1512-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1343–50. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200105033441801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, et al. Effects of diet and exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. The Da Qing IGT and Diabetes Study. Diabetes Care. 1997;20:537–44. doi: 10.2337/diacare.20.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ackermann RT, Finch EA, Brizendine E, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into the community. The DEPLOY Pilot Study. Am J Prev Med. 2008;35:357–63. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year followup. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1755–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.de Miguel Yanes J, Shrader P, Pencina M, et al. Genetic risk reclassification for type 2 diabetes by age below or above 50 years using 40 type 2 diabetes risk single nucleotide polymorphisms. Diabetes Care. 2010 doi: 10.2337/dc10-1265. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Evans JP, Meslin EM, Marteau TM, Caulfield T. Genomics. Deflating the genomic bubble. Science. 2011;331:861–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1198039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grundy SM, Cleeman JI, Daniels SR, et al. American Heart Association. National Heart, Lung,and Blood Institute. Diagnosis and management of the metabolic syndrome: An American Heart Association/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Scientific Statement. Circulation. 2005;112:2735–52. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.169404. (see comment) (erratum appears in Circulation 2005; 112: e297) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ford ES, Li C, Sattar N. Metabolic syndrome and incident diabetes: Current state of the evidence. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1898–904. doi: 10.2337/dc08-0423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lorenzo C, Okoloise M, Williams K, et al. (San Antonio Heart Study). The metabolic syndrome as predictor of type 2 diabetes: The San Antonio heart study. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3153–9. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.11.3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meigs JB, Williams K, Sullivan LM, et al. Using metabolic syndrome traits for efficient detection of impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care. 2004;27:1417–26. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.6.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford ES, Giles WH, Dietz WH. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome among US adults: Findings from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. JAMA. 2002;287:356–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hivert MF, Grant RW, Shrader P, Meigs JB. Identifying primary care patients at risk for future diabetes and cardiovascular disease using electronic health records. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:170. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meigs JB, Shrader P, Sullivan LM, et al. Genotype score in addition to common risk factors for prediction of type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:220–19. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, et al. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110:281–90. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a112813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brennan P, Hung R. Mendelian randomization. In: Hirvonen A, editor. State of the art of genotype vs. phenotype studies. Nofer Institute of Occupational Medicine; 2008. pp. 91–4. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davey Smith G, Ebrahim S. ’Mendelian randomization’: Can genetic epidemiology contribute to understanding environmental determinants of disease? Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:1–22. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sheehan NA, Didelez V, Burton PR, Tobin MD. Mendelian randomisation and causal inference in observational epidemiology. PLoS Med. 2008;5:e177. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thanassoulis G, O'Donnell CJ. Mendelian randomization: Nature's randomized trial in the post-genome era. JAMA. 2009;301:2386–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Markowitz SM, Park ER, Delahanty LM, et al. Perceived impact of diabetes genetic risk testing among patients at high phenotypic risk for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1960. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hivert MF, Warner AS, Shrader P, et al. Diabetes Risk Perception and Intention to Adopt Healthy Lifestyles Among Primary Care Patients. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1820–2. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seidel MC, Powell RO, Zgibor JC, et al. Translating the Diabetes Prevention Program into an urban medically underserved community: A nonrandomized prospective intervention study. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:684–9. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walker EA, Wylie-Rosett J. Evaluating Risk Perception of Developing Diabetes as a Multi-dimensional Construct. Diabetes. 1998;47(1S Suppl):5A. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Greene GW, Rossi SR, Reed GR, et al. Stages of change for reducing dietary fat to 30% of energy or less. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94:1105–10. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)91127-4. (quiz 1111-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcus BH, Selby VC, Niaura RS, Rossi JS. Self-efficacy and the stages of exercise behavior change. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1992;63:60–6. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1992.10607557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Connell D, Velicer WF. A decisional balance measure and the stages of change model for weight loss. Int J Addict. 1988;23:729–50. doi: 10.3109/10826088809058836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Acheson LS, Wang C, Zyzanski SJ, et al. Genet Med. 2010;12:212–18. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Claassen L, Henneman L, Janssens AC, et al. Using family history information to promote healthy lifestyles and prevent diseases; A discussion of the evidence. BMC Public Health. 2010;10:248. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scheuner MT, Sieverding P, Shekelle PG. Delivery of genomic medicine for common chronic adult diseases: A systematic review. JAMA. 2008;299:1320–34. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Burke W, Psaty BM. Personalized medicine in the era of genomics. JAMA. 2007;298:1682–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.14.1682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Khoury MJ, Gwinn M, Yoon PW, et al. The continuum of translation research in genomic medicine: How can we accelerate the appropriate integration of human genome discoveries into health care and disease prevention?. Genet Med. 2007;9:665–74. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e31815699d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonetta L. Getting up close and personal with your genome. Cell. 2008;133:753–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]