Abstract

Vitamin A (VA) plays an important role in postnatal lung development and maturation. Previously, we have reported that a supplemental dose of VA combined with 10% of all-trans-retinoic acid (VARA), synergistically increases retinol uptake and retinyl ester (RE) storage in neonatal rat lung, while up-regulating several retinoid homeostatic genes including lecithin:retinol acyltransferase (LRAT), and the retinol-binding protein receptor, STRA6. However, whether inflammation impacts the expression of these genes and thus compromises the ability to VARA to increase lung RE content is not clear. Neonatal rats, 7–8-days old, were treated with VARA either concurrently with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (experiment 1), or 12 h after LPS administration (experiment 2); in both studies, lung tissue was collected 6 h after VARA treatment, when RE formation is maximal. Inflammation was confirmed by increased IL-6 and CCL2 gene expression in lung at 6 h and C-reactive protein in plasma at 18 h. In both studies, LPS-induced inflammation only slightly reduced but did not prevent the VARA-induced increase in lung RE. Quantitative RT-PCR showed that co-administration of LPS with VARA slightly attenuated the VARA-induced increase of LRAT mRNA, but not of STRA6 or CYP26B1, the predominant RA hydroxylase in lung. By 18 h post-LPS, expression had subsided and none of these genes differed from the level in the control group. Overall, our results suggest that retinoid homeostatic gene expression is reduced modestly if at all by acute LPS-induced inflammation and that VARA is still effective in increasing lung RE under conditions of moderate inflammation.

Keywords: vitamin A supplementation, neonate, lung, inflammation, homeostasis

Introduction

Vitamin A (VA) is required for normal lung development in the pre- and postnatal periods, yet VA storage is low in the human lung at birth. Premature delivery is one of the major factors that contributes to severe VA deficiency and puts very-low birth weight preterm infants at high risk for developing pulmonary diseases, such as respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD)(1–3). Supplementing VA directly to newborns improves the infant’s VA status, and has also produced promising results in animal models for reducing lung injury and dysfunction(3–6). Other studies have indicated that the administration of all-trans-RA, a biologically active metabolite of VA, to neonatal animals is capable of inducing alveolar formation and the repair of epithelial lesions, and increasing surfactant synthesis in lung(7–10). Retinyl ester (RE), the storage form of vitamin A, is recognized as constituting an essential endogenous pool of retinoid for the formation of bioactive compounds, including RA, which are critical for normal differentiation(11).

RA is believed to exert much of its influence on development and cell differentiation through regulation of gene transcription(12; 13). Several important genes that are involved in retinoid homeostasis are also regulated by RA. In a previous study, we have shown that STRA6, a retinol-binding protein receptor which mediates cellular retinol uptake(14), lecithin:retinol acyltransferase (LRAT), an enzyme that converts retinol to its storage form, RE, as well as CYP26B1, a cytochrome P450 which catalyzes the oxidation of RA(15), are tightly regulated by RA in the neonatal lung(16). Interruption of the expression of these genes might alter the balance of retinol metabolism in the lung tissue.

It was suggested in the same study that VA storage in the neonatal lung is increased efficiently by administering VA orally in combination with all-trans-RA (VARA)(17; 18). When VA and RA were mixed together in a molar ratio of 10:1 and delivered orally, VARA was shown to produce a synergistic increase in lung RE formation, about 4 to 5-fold above the increase due to an identical amount of VA given without RA(17). A metabolic tracer study showed that the administration of RA redirects part of the flow of the supplemental [3H]-retinol into the lungs in VARA-treated neonates(16). Investigation of the molecular mechanism of the VARA synergy revealed that RA acts as a regulator of VA homeostasis by rapidly upregulating several retinoid regulatory genes, including STRA6, LRAT, and STRA6 and CYP26B1 in the neonatal lung(16), thus promoting RE formation more efficiently. Simultaneously, the VA component of VARA provides the retinol substrate for this process.

Inflammation is very often observed in preterm infants or infants with a weakened immune system(2; 4; 19). During of the inflammatory response, proinflammatory cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor-α, IL-1β and IL-8 are secreted by alveolar macrophages, fibroblasts, type II pneumocytes, and endothelial cells in the early inflammatory response upon the stimulation of inflammatory agents(20). These cytokines recruit circulating neutrophils and macrophages to the local sites of injury or infection and subsequently release higher amount of cytokines and chemokines to initiate a sequence of injurious events(21). As an organ with a large surface area exposed to the outside, the lung is vulnerable to exogenous pathogens, allergens or chemicals. Increased levels of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines have been detected in the airways of preterm infants at various stages of developing BPD(22; 23). Risk factors contributing to the inflammatory responses in the lung include inappropriate resuscitation, oxygen toxicity, mechanical ventilation, pulmonary and/or systemic infection(24), which are most common causes of respiratory inflammation in newborn or premature infants. Inflammation is also known to alter the expression of many genes including genes in the CYP family(25). An in vivo study in rat liver suggested that inflammation induced by administration of LPS or poly-IC significantly opposes the induction of CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 expression by RA(26). It is unknown whether inflammation in the lungs attenuates, or may have no effect on the VARA-induced synergy in RE formation.

In the present study, we investigated whether LPS-induced inflammation may prevent or attenuate the VARA-mediated increase in RE formation and regulation of LRAT and STRA6 in neonatal rat lungs. We also investigated CYP26B1 since its regulation could contribute to alterations in the rate of clearance of retinoids from the lung.

Experimental Methods

Materials and dose preparation

Vitamin A (all-trans-retinyl palmitate), and all-trans-RA were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). As described previously(18), these two agents were mixed in a molar ratio of 10:1 at final concentrations of 0.05 M and 0.005 M in canola oil, respectively, in the oral dose. A solution of LPS from Pseudomonas aeruginosa (List Biological Laboratory, Campbell, CA), was prepared in a concentration of 10 µg/ml in sterile saline (Sal). Canola oil and saline were used as placebos for VARA and LPS, respectively.

Animals and experimental designs

Animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Use and Care Committee of The Pennsylvania State University. Two experiments were according to the time of LPS administration relative to the time of VARA supplementation in neonatal rats. In experiment 1, LPS and VARA were co-administered 6 h before the collection of lung tissue. In experiment 2, LPS was administered 12 h before VARA to induce inflammation at the time of VARA supplementation; in both experiments tissue was collected 6 h after VARA treatment, when lung RE formation is essentially complete(18). In each experiment, 7–8 day-old Sprague-Dawley rat pups that had been delivered and were nursed by VA adequate dams were assigned randomly to 4 groups, which received canola oil (control), LPS alone, VARA, or both LPS and VARA (n=4–5 pups/group).

At the beginning of each experiment the pups were weighed and the dose of VARA was determined by weight, 0.4 µl of the dose described above per gram of body weight, or approximately 6 mg retinol and 0.6 mg RA per kg. The dose was delivered directly to the rat pup’s mouth by micropipette. Pseudomonas aeruginosa-LPS was injected i.p. as a single dose, equal to 200 µg of LPS/kg. In both studies, the neonates were individually euthanized by isoflurane inhalation 6 h after treatment with VARA. Lung tissue was dissected, frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for later analysis.

Plasma anti-CRP antibody enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Plasma anti-C reactive protein (CRP) was quantified by a rat CRP ELISA test kit (Life Diagnostic, Inc., West Chester, PA), following the manufacturer’s instructions. A standard of serially diluted control serum was included, and titers of antibody were calculated based on this standard curve. One titer unit was defined as the dilution fold that produced 50% of the maximal optical density for the standard sample.

Retinoid analysis

Lung VA concentration was quantified as described previously as total retinol (RE + retinol), which has been shown to be >90% RE and <10% retinol(18). Weighed portions of lung tissue were extracted in chloroform:methanol, 2:1 v:v, overnight and then processed by the washing procedure of Folch et al.(27). A portion of each lipid extract was subjected to saponification, after which a known amount of trimethylmethoxyphenyl-retinol was added to each sample as an internal standard. Following reverse-phase HPLC separation with UV detection, the areas of the peaks were quantified by Millenium-32 (Waters, Millford, MA) software.

Gene mRNA level determination

Total RNA from the lung tissue of individual pups was extracted using a guanidine extraction method and reverse transcribed into its complementary DNA (cDNA). The diluted reaction product was used for quantitative real-time PCR (rt-PCR) analysis. Primers designed to detect mRNA for rat LRAT (NM_022280.2), rat CYP26B1 (NM_181087), and rat STRA6 (NM_0010029924.1) were as described previously (16). For IL-6 (NM_012589.1) the primers were: 5’-TGT GCA ATG GCA ATT CTG AT-3’ (forward) and 5’-TGG TCT TGG TCC TTA GCC AC-3’; and for rat CCL2 (NM_031530.1) the primers were 5’-AGG TGT CCC AAA GAA GCT GT-3’ (forward) and 5’-TGC TTG AGG TGG TTG TGG AA-3’ (reverse). The mRNA expression level for each sample was corrected by calculating the mRNA-to-ribosomal 18S RNA ratio. Data were normalized to the average value for the control group, set at 1.00, prior to statistical analysis.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as group means ± SEM. Differences were tested by one-factor ANOVA followed by Fisher’s protected least significant difference test using GraphPad Prism software (San Diego, CA). For comparisons, we normalized the mean mRNA value of the control group to 1.00, and the mean values of the other groups were converted accordingly. When variance terms were unequal, values were log10-transformed prior to statistical analysis. Differences with P<0.05 were considered significant.

Results

Markers of inflammation indicate induction of inflammation

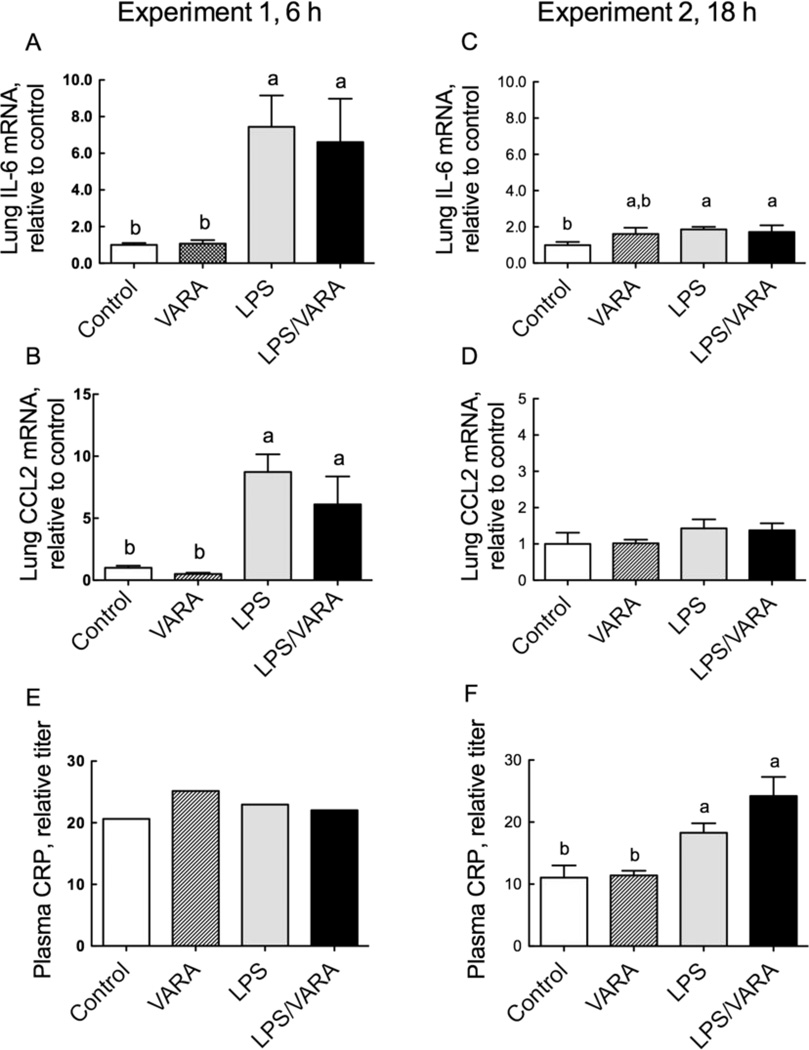

To confirm that inflammation was induced in our neonatal rats, we determined the expression of certain inflammation markers in the lung by rt-PCR and the level of CRP in the serum by ELISA. Interleukin-6 and CCL2 are inflammatory mediators in the early inflammatory response and in the evolution of inflammatory events. In the neonatal lung, the expression of these two genes was increased by LPS at 6 h (Fig. 1a, 1b). However, 18 h after administration of LPS, the levels had returned to the control level (Fig. 1c, 1d). On the other hand, plasma CRP, an acute phase protein produced mainly by the liver, was not increased at 6 h but was significantly increased at 18 h (Fig. 1e, 1f). These results demonstrated that neonatal rats that received LPS were experiencing a state of inflammation by 6 h after LPS treatment, manifested by increased cytokine and chemokine gene expression in the lungs, and a systemic response which developed between 6 and 18 h and was manifested as an elevation in plasma acute phrase protein.

Fig. 1.

Expression of lung IL-6 (a,c) and CCL2 (b,d), and plasma CRP (e,f) determined 6 h and 18 h after administration of LPS in VARA-supplemented neonatal rats. Lung tissues were collected 6 h after VARA treatment and processed for total RNA isolation and subjected to q-PCR analysis. In experiment 1, LPS and VARA were administered simultaneously, while in experiment 2, LPS was administered 12 h before VARA supplementation. Data for IL-6 and CCL2 mRNA were normalized to 18S rRNA and the average value for the control group was set to 1.0 for each experiment. Data for CRP were log10-transformed prior to ANOVA. Data are presented as group means ± SEM except for panel e which represents a single pool for each treatment. Groups marked with different letters differed significantly, P<0.05.

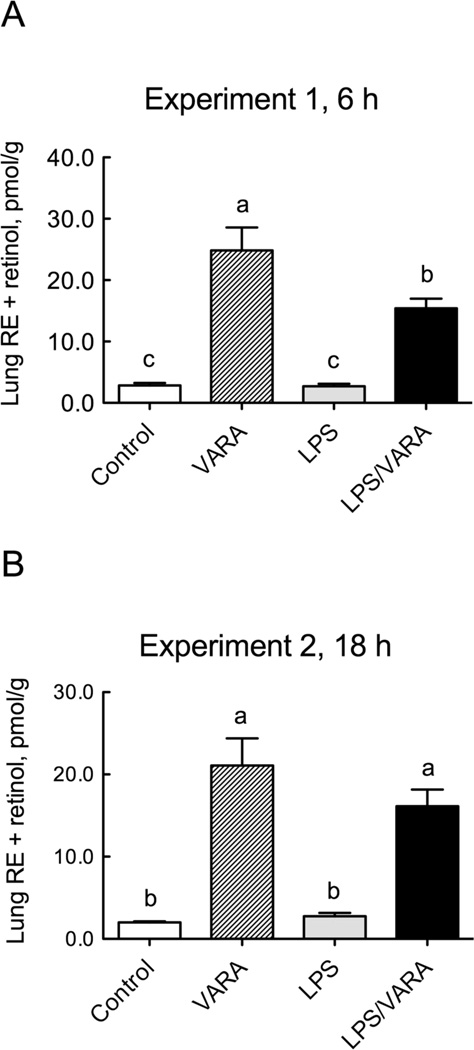

LPS-induced inflammation only slightly reduced the VARA-mediated increase in lung total retinol

In experiment 1, LPS and VARA were administered concurrently to 7–8 d old neonatal rats, while in experiment 2, LPS was administered 12 h prior VARA treatment to establish inflammation before treatment with VARA. In both experiements, VARA significantly increased lung RE formation 6 h after its administration (Fig. 2a,b). Treatment with LPS alone did not significantly alter the basal level of lung RE. In the 6-h study, LPS attenuated the increase in RE by VARA by ~38% (Fig. 2a). In the 18-h study, LPS also slightly but nonsignificantly reduced the increase in lung RE due to VARA (Fig. 2b). In experiment 2, we also conducted a metabolic study by adding a tracer of [3H]-retinol to the VARA or placebo dose to investigate the uptake of newly absorbed retinol into lung tissue. The percentage of newly absorbed 3H in the lungs of VARA-treated neonatal rats did not differ between the control group and those with inflammation (data not shown). These results suggest that an acute inflammation induced by LPS does not prevent the increase in lung RE formation that is promoted by treatment with VARA.

Fig. 2.

Lung total RE plus retinol concentration 6 h (a) and 18 h (b) after administration of LPS in VARA-supplemented neonatal rats. Experimental conditions were as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Lung total retinol contents (>90% RE) were determined by HPLC. Data are presented as group means ± SEM. Data were log10- transformed prior to ANOVA. Groups marked with different letters differed significantly, P<0.05.

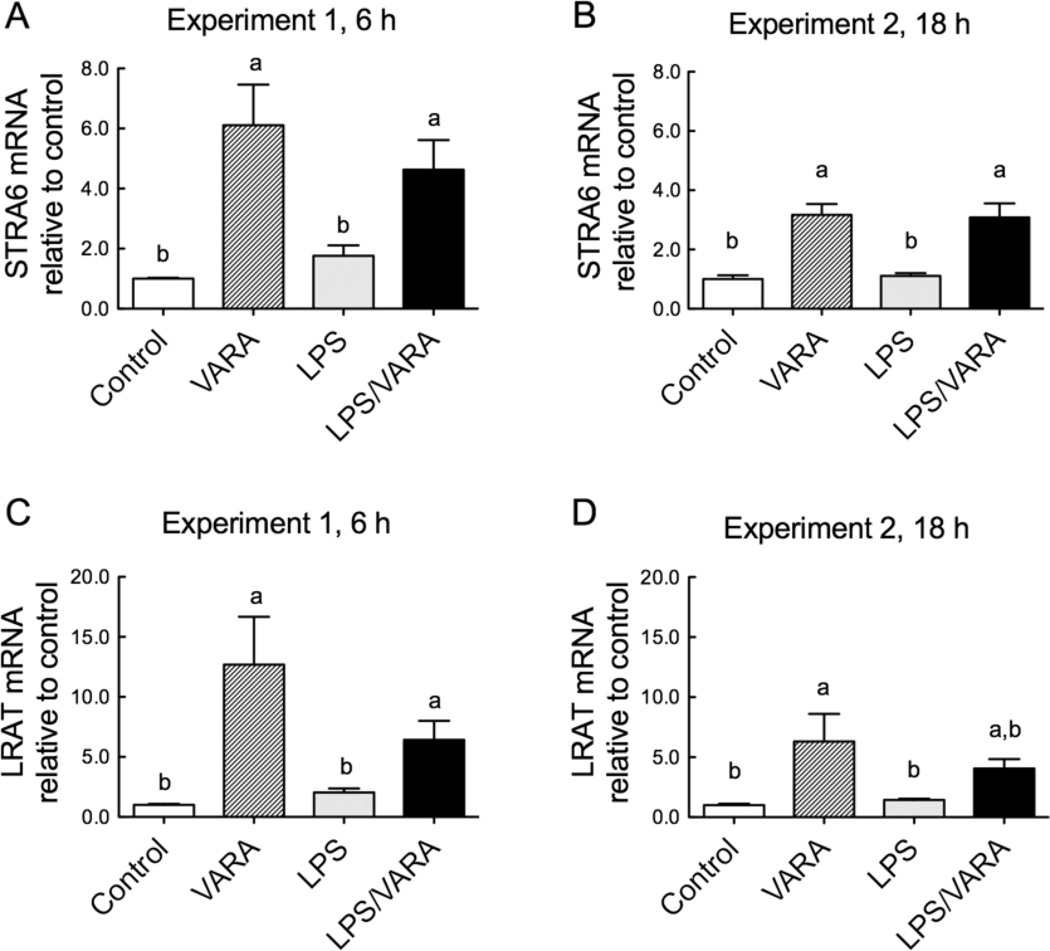

LPS-induced inflammation did not interrupt the induction of STRA6, LRAT and CYP26B1 by VARA supplementation

STRA6 and LRAT are likely to function in concert (28) to regulate the uptake and esterification of retinol. RA was shown previously to up-regulate the expression of these genes and to enhance retinol uptake and RE storage in the neonatal lung (16). In the present studies, LPS alone has no effect on the level of STRA6 mRNA, and VARA was as effective in increasing STRA6 mRNA regardless of treatment with LPS and the time of LPS administration prior to VARA supplementation (Fig. 3a, 3b). Similarly, VARA significantly induced LRAT mRNA in both the 6-h and 18-h studies (Fig Fig. 3c, 3d). Only in the 6-h study, LPS slightly reduced the induction of LRAT by VARA which corresponds with the slight reduction of RE formation observed in the LPS/VARA treated group.

Fig. 3.

STRA6 (a,b) and LRAT (c,d) mRNA expression 6 h and 18 h after administration of LPS in VARA-supplemented neonatal rats. Experimental conditions were as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Data were normalized to 18S rRNA and the average value for the control group was set to 1.0 for each experiment. Data are presented as group means ± SEM. Data were log10-transformed by log10 prior to ANOVA. Groups with different letters differed significantly, P<0.05.

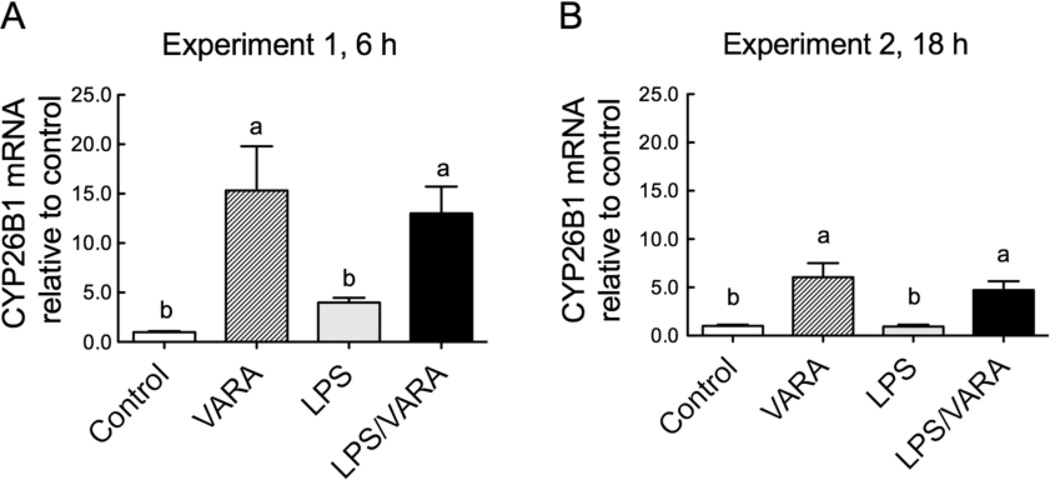

The expression of CYP26B1, the principal retinoid metabolizing CYP26 form in the lung, which was shown previously to be increased by RA and to remain elevated longer than STRA6 or LRAT after RA or VARA treatment (16), was also examined in LPS-treated neonates. CYP26B1 mRNA levels were not reduced significantly after treatment with LPS (Fig. 4a, 4b). Thus, in both experiments, the expression of these three principal retinoid homeostatic genes was significantly and rapidly increased above the control level 6 h after VARA supplementation. These results suggested that LPS-initiated inflammation does not prevent the normal response to VARA, either regarding retinol uptake and esterification (Fig. 3), or retinoid oxidation (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

CYP26B1 mRNA expression 6 h (a) and 18 h (b) after administration of LPS in VARA-supplemented neonatal rats. Experimental conditions were as described in Fig. 1. Data were normalized to 18S rRNA and the average value for the control group was set to 1.0 for each experiment. Data are presented as group means ± SEM. Data were log10-transformed by log10 prior to ANOVA. Groups with different letters differed significantly, P<0.05.

Discussion

The lung is a major extrahepatic organ that requires VA activity for normal development and function, and has the potential to store VA after VA administration(29; 30). We have shown previously that when RA is supplemented simultaneously with VA as VARA, the combination produces a significant synergy, increasing lung RE to a greater extent than an equal amount of VA alone. Moreover, this increase is tissue selective because the synergistic response is not observed in the liver, in which VARA and the same amount of VA alone increased RE content to the same extent(17; 18). Therefore these results have shown that VA uptake and RE storage can be elevated in a tissue-specific manner. However, little is known about retinoid homeostasis in the lung under conditions of inflammation.

It is well known that the condition of hyperoxia usually induces reactive O2 species (ROS), which in turn damage lipids, proteins, and nucleic acid in the lung tissue. It has been reported that inflammatory cells in the lungs and depletion of antioxidants, such as acsorbate, occurs time dependently during exposure to hyperoxia (31). Although the roles of VA as an antioxidant and anti-inflammatory factor have been explored, it is still controversial as to whether, or under what conditions, VA exerts pro- or anti-inflammatory effects. Pasquali et. al. (32) have reported that, when VA supplementation was introduced to pregnant rats, even in a safe dosage, the lungs of the offspring of these rats contained increased levels of lipo- and protein oxidation products and exhibited induction of antioxidant defensive enzymes. These changes in the lung tissue revealed a potential for harmful effects of vitamin A supplementation in neonates. However, James et al.,(33) recently showed that treatment with VARA of neonatal mice reared by their dams under hyperoxic conditions resulted in a reduction in lung injury due to hyperoxia, and attenuated the hyperoxia-induced increased in macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2 mRNA and protein in the lungs. Additionally, VARA prevented the hyperoxia-induced increases in gene expression of several pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) and hyperoxia-induced reduction of IL-10. Under hyperoxic conditions, VARA promoted a >5-fold increase in lung RE concentration compared to control neonatal mice, although the increase was not greater than by VA alone under hyperoxic conditions. These studies highlight that additional research is needed under conditions relevant to neonatal lung health, such as oxygen therapy and direct VA supplementation, to fully understand the interactions of VA, its metabolite RA, and ROS and other indicators of oxidative metabolism in the lungs.

In the present study, we initially hypothesized that LPS treatment would interfere with retinoid homeostasis in the lungs, as suggested by previous studies in which LPS-induced inflammation caused a strong attenuation of the RA-induced increase in CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 gene expression in adult rat liver(26). In our present studies in neonatal rats, the increase in the lung in the expression of IL-6 and CCL2 (indicators of early inflammatory responses) and the increase in plasma in CRP protein (marker of acute inflammation) confirmed that a state of inflammation existed in the neonates. However, the influence of LPS-induced inflammation on VA homeostasis was very mild. LPS-induced inflammation reduced the increase in RE by ~38% when LPS and VARA were administered concomitantly, and only by ~24%, a non-statistically significant difference, when LPS was administered 12 h before VARA supplementation. The dose of LPS that we used, 200 µg/kg of body weight, was lower compared to the dose of 500 µg/kg used previously in adult rats(34; 35), because we found that neonates did not survive treatment with the adult dose. Overall, we believe that the conditions in our study were representative of LPS-induced inflammation in this age group. Our qPCR data for STRA6, LRAT and CYP26B1 also indicated that the inflammation state had little influence on retinoid homeostasis, either with or without VARA supplementation. In clinical situations in which exposure to LPS is principally due to infection with Gram-negative bacteria, additional factors related to infection and/or the host response to bacterial infection could modulate retinoid homeostasis in ways not observed in the present study. Additional studies are also needed in other models. However, the current study suggests that the lung’s ability to esterify retinol derived from newly absorbed VA, and to store the resulting RE may not be compromised during a state of moderate inflammation.

Our data on lung RE content and retinoid homeostatic gene expression for the groups of neonates that were treated with LPS only is also of interest. These results suggests that the concentration of endogenous VA, derived by transfer from the mother, and levels of expression of retinoid homeostatic genes, in the lungs in the absence of VARA supplementation is not greatly altered by acute lung inflammation. Overall, the results of our study suggest that, even in a state of moderate inflammation, VARA could still be an effective therapeutic strategy for improving VA status in the neonatal lung.

Although VA and RA were admixed in the VARA preparation, there is reasonable evidence that they are absorbed independently, with the VA component being absorbed as RE in chylomicrons, and the RA component (and any RA produced from the newly absorbed VA in the intestine) being absorbed into the portal vein(36). Chylomicron RE are rapidly removed, mostly into liver but with some uptake by extrahepatic tissues, including the lungs as shown in [3H]-retinol tracer studies(18). RA in plasma is rapidly cleared, with a half-life of a few minutes(37; 38). It therefore appears that the greatest effect of VARA occurs in the immediate absorptive period after dosing. This is further supported by a maximal increase in lung RE within ~6 h after oral administration of VARA. Our previous studies suggest that the regulation of retinoid homeostatic genes is attributable to the RA component of VARA, or surrogate acidic retinoids with RA-like activity(16), but the strong accumulation of RE in the neonatal lungs necessarily requires adminisration of retinol, delivered as the VA component of the VARA dose(16; 18). Thus both components of the VARA dose are effective together, through their different mechanisms, even in a state of moderate inflammation. In terms of their relative turnover rates, RA is rapidly catabolized, while retinol has an intermediate turnover rate and RE is a very stable form of VA that can be stored in tissues for long periods, as well as mobilized to form retinol again. Treatment with VARA results in the lung “seeing” a short-term pulse of RA, resulting in changes in gene expression, as well as a more persistent uptake of retinol from holo-RBP, or possibly RE from chylomicrons, that can be stored in the tissues as RE. RE stored in the tissue can be hydrolyzed to provide substrate for the production of RA, and, hence, maintenance of steady-state levels of retinoids over time. Given the promising results, noted earlier, for RA therapy in promotion of alveolarization and tissue repair in neonatal and adult models of lung disease(7–10), VARA supplementation could potentially facilitate similar effects through its rapid provision of RA and longer-term provision of retinol for esterification and storage. However, not all studies using RA have been effective and new strategies are needed. Because RA cannot be reduced in vivo to generate retinol or its esters, the VARA combination which provides both RA and retinol could be advantageous as a more stable and longer-acting treatment for inducing lung differentiation and promoting the repair of damaged tissue.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of our laboratory for assistance with animal experiments. This work was supported by NIH grants CA-090214, and HD-066982 (to A.C.R.). The authors have no disclosures. Both authors have read and approved the final version. L.W. designed and conducted the research and prepared the draft manuscript; A.C.R. planned and designed the research and prepared the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- BPD

bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- CCL2

chemokine (C-C motif) ligand 2

- CRP

C-reactive protein

- CYP26B1

cytochrome P450 26B1

- IL-6

interleukin

- LRAT

lecithin:retinol acyltransferase

- LPS

lipopolysaccharide

- RDS

respiratory distress syndrome

- RE

retinyl ester

- Sal

saline

- STRA6

Stimulated by Retinoic Acid 6

- VA

vitamin A

- VARA

supplemental VA combined with 10% of all-trans-retinoic acid

Footnotes

The authors have no potential financial conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Zachman RD, Grummer MA. Retinoids and lung development. In: Zachman RD, Grummer MA, editors. Contemporary Endocrinology: Endocrinology of the lung: Development and surfactant synthesis. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press, Inc; 2000. pp. 161–179. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mactier H, Weaver LT. Vitamin A and preterm infants: what we know, what we don't know, and what we need to know. Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2005;90:F103–F108. doi: 10.1136/adc.2004.057547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guimarães H, Guedes MB, Rocha G, et al. Vitamin A in Prevention of Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia. Curr Pharm Des. 2012 E-pub ahead of print Feb 27 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shenai JP, Kennedy KA, Chytil F, et al. Clinical trial of vitamin A supplementation in infants susceptible to bronchopulmonary dysplasia. J Pediatr. 1987;111:269–277. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(87)80086-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tyson JE, Wright LL, Oh W, et al. Vitamin A supplementation for extremely-low-birth-weight infants. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1962–1968. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906243402505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambalavanan N, Tyson JE, Kennedy KA, et al. Vitamin A supplementation for extremely low birth weight infants: outcome at 18 to 22 months. Pediatrics. 2005;115:e249–e254. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraslon C, Bourbon JR. Retinoids control surfactant phospholipid biosynthesis in fetal rat lung. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 1994;266:L705–L712. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1994.266.6.L705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maden M, Hind M. Retinoic acid in alveolar development, maintenance and regeneration. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2004;359:799–808. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2004.1470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Belloni PN, Garvin L, Mao CP, et al. Effects of all-trans-retinoic acid in promoting alveolar repair. Chest. 2000;117(Suppl. 1):235S–241S. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.5_suppl_1.235s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGowan SE. Contributions of retinoids to the generation and repair of the pulmonary alveolus. Chest. 2002;121(5 Suppl):206S–208S. doi: 10.1378/chest.121.5_suppl.206s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tang XH, Gudas LJ. Retinoids, retinoic acid receptors, and cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:345–364. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duong V, Rochette-Egly C. The molecular physiology of nuclear retinoic acid receptors. From health to disease. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1812:1023–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fields AL, Soprano DR, Soprano KJ. Retinoids in biological control and cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2007;102:886–898. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawaguchi R, Yu J, Honda J, et al. A membrane receptor for retinol binding protein mediates cellular uptake of vitamin A. Science. 2007;315:820–825. doi: 10.1126/science.1136244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ross AC, Zolfaghari R. Cytochrome P450s in the regulation of cellular retinoic acid metabolism. Annu Rev Nutr. 2011;31:65–87. doi: 10.1146/annurev-nutr-072610-145127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu L, Ross AC. Acidic retinoids synergize with vitamin A to enhance retinol uptake and STRA6, LRAT, and CYP26B1 expression in neonatal lung. J Lipid Res. 2010;51:378–387. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M001222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ross AC, Li NQ, Wu L. The components of VARA, a nutrient-metabolite combination of vitamin A and retinoic acid, act efficiently together and separately to increase retinyl esters in the lungs of neonatal rats. J Nutr. 2006;136:2803–2807. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.11.2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ross AC, Ambalavanan N, Zolfaghari R, et al. Vitamin A combined with retinoic acid increases retinol uptake and lung retinyl ester formation in a synergistic manner in neonatal rats. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:1844–1851. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M600061-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darlow BA, Graham PJ. Vitamin A supplementation for preventing morbidity and mortality in very low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002:CD000501. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Speer CP. Inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a continuing story. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;11:354–362. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Speer CP. Inflammation and bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Neonatol. 2003;8:29–38. doi: 10.1016/s1084-2756(02)00190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Groneck P, Gotze-Speer B, Oppermann M, et al. Association of pulmonary inflammation and increased microvascular permeability during the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia: a sequential analysis of inflammatory mediators in respiratory fluids of high-risk preterm neonates. Pediatrics. 1994;93:712–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Groneck P, Schmale J, Soditt V, et al. Bronchoalveolar inflammation following airway infection in preterm infants with chronic lung disease. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2001;31:331–338. doi: 10.1002/ppul.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jobe AH, Ikegami M. Mechanisms initiating lung injury in the preterm. Early Hum Dev. 1998;53:81–94. doi: 10.1016/s0378-3782(98)00045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgan ET, Li-Masters T, Cheng PY. Mechanisms of cytochrome P450 regulation by inflammatory mediators. Toxicology. 2002;181–182:207–210. doi: 10.1016/s0300-483x(02)00283-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zolfaghari R, Cifelli CJ, Lieu SO, et al. Lipopolysaccharide opposes the induction of CYP26A1 and CYP26B1 gene expression by retinoic acid in the rat liver in vivo. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;292:G1029–G1036. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00494.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Folch J, Lees M, Sloane Stanley GH. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J Biol Chem. 1957;226:497–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kawaguchi R, Yu J, Ter-Stepanian M, et al. Receptor-mediated cellular uptake mechanism that couples to intracellular storage. ACS Chem Biol. 2011;6:1041–1051. doi: 10.1021/cb200178w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nagy NE, Holven KB, Roos N, et al. Storage of vitamin A in extrahepatic stellate cells in normal rats. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:645–658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shenai JP, Chytil F. Vitamin A storage in lungs during perinatal development in the rat. Biol. Neonate. 1990;57:126–132. doi: 10.1159/000243172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pace PW, Yao LJ, Wilson JX, et al. The effects of hyperoxia exposure on lung function and pulmonary surfactant in a rat model of acute lung injury. Exp Lung Res. 2009;35:380–398. doi: 10.1080/01902140902745166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pasquali MA, Schnorr CE, Feistauer LB, et al. Vitamin A supplementation to pregnant and breastfeeding female rats induces oxidative stress in the neonatal lung. Reprod Toxicol. 2010;30:452–456. doi: 10.1016/j.reprotox.2010.05.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.James ML, Ross AC, Bulger A, et al. Vitamin A and retinoic acid act synergistically to increase lung retinyl esters during normoxia and reduce hyperoxic lung injury in newborn mice. Pediatr Res. 2010;67:591–597. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181dbac3d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rosales FJ, Ritter SJ, Zolfaghari R, et al. Effects of acute inflammation on plasma retinol, retinol-binding protein, and its mRNA in the liver and kidneys of vitamin A-sufficient rats. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:962–971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rosales FJ, Ross AC. Acute inflammation induces hyporetinemia and modifies the plasma and tissue response to vitamin A supplementation in marginally vitamin A-deficient rats. J Nutr. 1998;128:960–966. doi: 10.1093/jn/128.6.960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross AC, Harrison EH. Vitamin A: Nutritional Aspects of Retinoids and Carotenoids. In: Zempleni J, Rucker RB, McCormick DB, et al., editors. Handbook of Vitamins. Boca Raton: Taylor & Francis Group; 2007. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurlandsky SB, Gamble MV, Ramakrishnan R, et al. Plasma delivery of retinoic acid to tissues in the rat. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:17850–17857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.30.17850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cifelli CJ, Ross AC. All-trans-retinoic acid distribution and metabolism in vitamin A-marginal rats. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2006;291:G195–G202. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00011.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]