How does the visual system construct clear motion percepts from ambiguous signals? We evaluated the role of attention by tracking the position of spatial selection with an electrophysiological correlate. We generated a six-frame animation sequence (Fig. 1, left column), which could be perceived either as the yellow traffic light moving left and right or as two traffic lights moving up and down separately on the left and right sides while changing their colors. These two potential apparent motion percepts competed for visual awareness, and we hypothesized that shifts of spatial selection would mediate this perceptual competition.

Fig. 1.

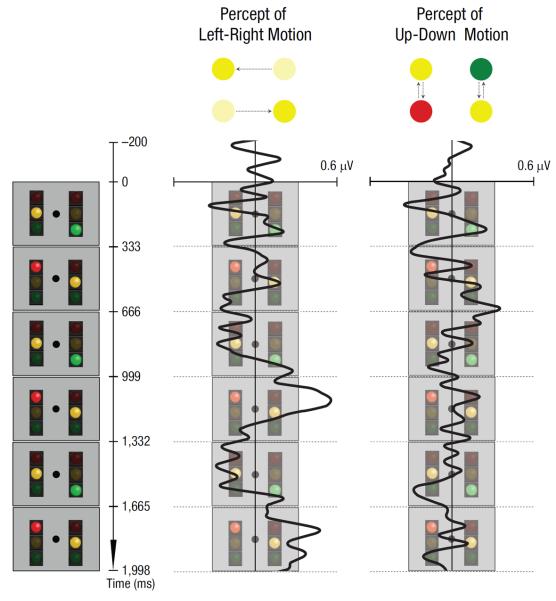

The six-frame animation sequence and event-related potential results. The animation (left column) could be perceived either as the yellow traffic light moving back and forth from one hemifield to the other (left-right motion) or as two traffic lights—one in each hemifield—changing colors (up-down motion). The next two columns show difference waveforms (the ipsilateral signal subtracted from the contralateral signal, plotted such that deflection consistent with the location of the yellow light indicates a shift of attention toward the yellow light). The middle column plots the difference waveform when participants experienced the left-right motion, whereas the right column plots the same waveform when participants experienced the up-down motion.

Tracking spatial selection was possible because the left-right-motion percept crossed the visual hemifield boundary. A bias of selection toward one hemifield is reflected in event-related potentials (ERPs) as a relative negativity at posterior electrodes contralateral to the selected hemifield (e.g., the N2pc and the contralateral delay activity/sustained parietal contralateral negativity, or CDA/SPCN; Luck & Kappenman, 2011). We monitored this contralateral negativity at high temporal resolution in 18 participants (18–35 years old) while they perceived either left-right or up-down motion (central fixation was enforced with an eye tracker; see the Supplemental Material for methodological details). We hypothesized that the perception of left-right motion would be uniquely associated with shifts in spatial selection between the left and right hemifields in synchrony with the left-right shifts in the position of the yellow light.

To evaluate this hypothesis, we analyzed the contralateral negativity in reference to the position of the yellow light (i.e., responses contralateral to the yellow light minus responses ipsilateral to the yellow light from P3/4, PO3/4, P7/8, O1/2, and PO7/8; Luck & Kappenman, 2011). In Figure 1, the difference waves are shown such that they deflect toward the icon of the yellow light if the contralateral negativity was consistent with spatial selection of that light. When participants reliably experienced left-right motion of the yellow light in Frames 3 through 6, we obtained clear lateral shifts in the difference wave (Fig. 1, middle column); thus, when participants saw the yellow light move between the left and right positions, the electrophysiological correlate of spatial selection shifted in tandem with their perception. Participants reported instability in motion perception during the first two apparent motion frames (partly because the left-right motion unpredictably began from the left or the right side), and the consistent left-right shifting of the contralateral negativity was correspondingly absent for these initial frames. When participants experienced separate up-down motions on the left and right sides, the left-right shifting of the contralateral negativity was also absent, as expected (Fig. 1, right column).

To determine the statistical reliability of this pattern of results, we averaged the difference wave within each apparent motion frame (333 ms). When participants saw the left-right motion, the mean for Frames 3 and 5 (when the yellow light was perceived to have moved to one side) was significantly different from the mean for Frames 4 and 6 (when the yellow light was perceived to have moved to the opposite side), t(17) = 2.37, p = .03. In contrast, when participants saw the up-down motion, the corresponding difference was not significant, t(17) = 0.52, p = .61. The interaction between time frame (3 and 5 vs. 4 and 6) and perceived motion (left-right vs. up-down) was significant, F(1, 17) = 6.29, p = .02.

In summary, we found that when participants perceived left-right motion in an ambiguous dynamic display, spatial selection synchronously tracked the object that switched its position between the left and right locations. This is the first neurophysiological evidence of a close temporal link between an observer's percept of object correspondence and a well-documented neural correlate of attentional selection and tracking. This link is consistent with suggestions that the correspondence problem in apparent motion perception might be resolved by positional shifting of the attentional spotlight (Cavanagh, 1992; Lu & Sperling, 1995; Verstraten, Cavanagh, & Labianca, 2000). The vector of the attention shift itself may contribute to the percept of motion, either through motion detectors that use a representation of selected locations as input (Lu & Sperling, 1995) or via an efference copy of the command used to shift attention (Verstraten et al., 2000). Because the ERP correlate of attention used here required that the measured percept cross the hemifield boundary, future work should rule out explanations related to hemispheric communication by confirming the link between apparent motion and attentional selection within a single hemifield.

Although these results alone cannot demonstrate that changing selection causes motion percepts, they provide insights into the type of attention mechanisms that might mediate motion perception. Previous psychophysical studies have suggested a close association between apparent motion perception and attention by demonstrating a type of motion perception that does not need to be driven by low-level luminance contrast energy, is capacity limited, and is flexibly driven by an attended feature (Ashida, Seiffert, & Osaka, 2001; Cavanagh, 1992; Lu & Sperling, 1995). The present results show that the type of attention that mediates this flexible motion mechanism may be related to other complex abilities that rely on coordinating one or more spotlights of attentional selection (Cavanagh, 2004), such as object tracking (Drew, Horowitz, Wolfe, & Vogel, 2011) and visual structure representation (Xu & Franconeri, 2012), which are associated with similar shifts in contralateral negativity.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Heeyoung Choo, Brian Levinthal, Ed Vogel, and Jeremy Wolfe for helpful comments.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 EY021184, Grant BCS-1056730 from the National Science Foundation and by Grant SBE-0541957 from the Spatial Intelligence and Learning Center at the National Science Foundation.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest with respect to their authorship or the publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Additional supporting information may be found at http://pss.sagepub.com/content/by/supplemental-data

References

- Ashida H, Seiffert A, Osaka N. Inefficient visual search for second-order motion. Journal of the Optical Society of America A. 2001;18:2255–2266. doi: 10.1364/josaa.18.002255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh P. Attention-based motion perception. Science. 1992;257:1563–1565. doi: 10.1126/science.1523411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavanagh P. Attention routines and the architecture of selection. In: Posner M, editor. Cognitive neuroscience of attention. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2004. pp. 13–28. [Google Scholar]

- Drew T, Horowitz TS, Wolfe JM, Vogel EK. Delineating the neural signatures of tracking spatial position and working memory during attentive tracking. Journal of Neuroscience. 2011;31:659–668. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1339-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z-L, Sperling G. Attention-generated apparent motion. Nature. 1995;377:237–239. doi: 10.1038/377237a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luck SJ, Kappenman ES. Oxford handbook of event-related potential components. Oxford University Press; New York, NY: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Verstraten FAJ, Cavanagh P, Labianca A. Limits of attentive tracking reveal temporal properties of attention. Vision Research. 2000;40:3651–3664. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00213-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu YQ, Franconeri SL. The head of the table: Marking the “front” of an object is tightly linked with selection. Journal of Neuroscience. 2012;32:1408–1412. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4185-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.