Abstract

Background

Vitamin nutritional status may influence some xenobiotic metabolism or vice versa.

Methods

This analysis examines the relationship between B-vitamin concentrations and 1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl)ethylene (DDT) isomers and metabolites in healthy women. Serum pp′DDT, pp′DDE, pp′DDD, op′DDT, op′DDE, and serum folate, cysteine, and vitamins B6 and B12 were measured in 296 nonsmoking female textile workers (21–34 yr) in Anhui, China. Mean (SD) age and body mass index of this cohort were 24.9 (1.5) y and 19.7 (2.0) kg/m2, respectively.

Results

Median pp′DDT, pp′DDE, pp′DDD, op′DDT, and op′DDE were 1.5, 29.2, 0.22, 0.17, and 0.09 ng/g, respectively. Median folate and cysteine were 9.2 and 200.0 nmol/L, respectively. Folate was significantly inversely associated with pp′DDT and pp′DDE: β (95% confidence interval [CI]) = −0.23 (−0.39, −0.07) and −0.20 (−0.36, −0.05), respectively, and it was marginally associated with pp′DDD. Cysteine was significantly inversely associated with pp′DDT, β (95% CI) = −0.69 (−1.00, −0.37); pp′DDE, β (95% CI) = −0.32 (−0.62, −0.02); pp′DDD, β (95% CI) = −0.31 (−0.59, −0.03); and op′DDT, β (95% CI) = −0.35 (−0.68, −0.02).

Conclusions

Folate and cysteine are independently inversely associated with DDT isomers, adjusting for vitamins B6 and B12, age, and body mass index. These nutrients may play a role in DDT metabolism; however, it is also possible that DDT may exert a negative impact on folate and cysteine levels. Longitudinal studies are needed to ascertain the direction of this association.

Keywords: DDT isomers/metabolites, folate, cysteine, vitamin B6, vitamin B12

Introduction

The biotransformation of xenobiotics from lipophilic chemicals to polar entities generally occurs in two metabolic phases. Phase I involves hydrolysis, reduction, and oxidation reactions that expose or include a functional group (-OH, -NH2, -SH, -COOH), usually resulting in a small increase in hydrophilicity. Phase II biotransformations reactions include glucuoronidation, sulfation, acetylation, methylation, conjugation with glutathione, and conjugation with amino acids such as glycine, taurine, and glutamic acid. Most phase II reactions result in greatly increased hydrophilicity, which promotes excretion of the xenobiotic [1,2].

The metabolism of 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl) ethane (DDT), 1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl)ethylene (DDE), and 1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl)ethane (DDD) has been studied in humans and a variety of other mammalian species, and is nicely summarized in the toxicological profile report written by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [3]. Briefly, one phase I model proposed that the major urinary metabolite of DDT, 2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl) acetic acid (DDA), is produced by a sequence involving reductive dechlorination, dehydrochlorination, reduction, hydroxylation, and oxidation of the aliphatic portion of the molecule. In this proposed pathway, DDT is initially metabolized in the liver to 2 intermediary metabolites: DDE and DDD. In humans, ingested DDT undergoes reductive dechlorination to DDD, which is further degraded and readily excreted as DDA. DDT is also converted by dehydrodechlorination to DDE, but this occurs with considerable latency and was shown to convert less than 20% over the course of the 3-year study. Also, DDE metabolism is slow, and, consequently, DDE is retained in adipose tissue. After phase I metabolism, many of the DDT metabolites ultimately are excreted in the conjugated form, bound to glycine, bile acid, serine, aspartic acid, and glucuronic acid.

DDT and its primary metabolite, DDE, are suspected human reproductive toxicants [4] and probable human carcinogens [5]. Use of DDT in the United States was banned by the Environmental Protection Agency in 1972, except in cases of public health emergencies [6]. By the 1980s, its use was banned in most developed countries, although DDT is still used today in many countries in which malaria is a public health problem [7–10]. China banned agricultural use of DDT in 1984 but continues to use it for malaria control in some regions [11,12]. Consequently, in much of the developing world, DDT and DDE remain widespread contaminants in food and persist in human adipose tissue and breast milk [13].

Despite concerns about the health effects of DDT/DDE, few studies have focused on the relationship between nutritional factors and DDT/DDE. Some animal studies have shown that lipophilic substances, such as sucrose polyester [14], may be effective in reducing body burdens of DDT and other pesticides. In addition, indole-3-carbinol, a component of cruciferous vegetables, alters DDT metabolism and reduces its estrogenic effects by favoring metabolism through the 2-hydroxyoestone pathway, a more benign pathway with regard to breast cancer risk compared to the 16-alpha-hydroxyoestrone pathway [15]. Langen et al. [16] showed that a mixture of hemin and excess cysteine was able to degrade DDT partially, where the degradation reaction catalyzed by the hemin-cysteine model was 8 × 104 times faster than the uncatalyzed reaction and produced 3 water-soluble, nontoxic, cysteine-containing conjugates. Other animal studies suggest that nutrient levels may be influenced by xenobiotics. For instance, a study in rats showed that polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) and DDT increase the biosynthesis of ascorbic acid and concomitantly accelerate the turnover of ascorbic acid in the body [17]. Other evidence suggests that PCBs, through a variety of mechanisms, may cause a vitamin A deficiency [18,19].

What led the present authors to consider the relationship between folate and DDT isomers and metabolites in the present population of healthy Chinese women were statistical considerations regarding the colinearity of DDT and vitamin B6 in relation to pregnancy loss. Previously, it was found that both DDT and vitamin B6 concentrations were associated with early pregnancy losses—DDT was positively associated, while vitamin B6 was negatively associated [20,21]. The fact that both are linked to adverse pregnancy outcomes makes this examination important.

Methods

Study Population

This is part of a prospective study of reproductive health conducted from 1996–1998 in textile mills in Anhui, China. Children's Memorial Hospital, and collaborating Chinese institutions have approved our study protocols. Written informed consent was obtained from each woman and her husband.

A detailed description of the study population and data collection methods was reported previously [22]. Briefly, women were eligible to participate if they: (1) were employed full time, (2) were aged 20 to 34 years, (3) were newly married, and (4) had obtained permission to have a child. All the women were nulliparous. Women were excluded if they (1) were already pregnant before enrollment, (2) had tried unsuccessfully to get pregnant for 1 year or more at any time in the past, or (3) planned to quit/change jobs or move out of the city during the 1-year course of follow-up.

Of 1006 newly married women who were screened (more than 90% of newly married women were employed at the mill), 961 met eligibility requirements and agreed to enroll. Three hundred eighty-six enrolled women were excluded from analysis because they did not collect urine samples daily (n = 121), did not begin collecting urine soon after stopping contraception (n = 53), never stopped using contraception (n = 95), became pregnant because of contraceptive failure (n = 78), were lost to follow-up (n = 8), withdrew shortly after enrollment (n = 27), or had inadequate diary data on menstruation and bleeding (n = 4). The 386 women excluded for the previous reasons were similar to the remaining enrolled women [22]. Of the remaining 575 women, 270 were excluded because they did not have baseline nutritional biomarker or serum DDT data, 6 because they reported current smoking or occupational toxicant exposure, and 3 because they had miscoded data. The present report therefore includes 296 women, and, compared to the 270 women excluded from this analysis, they were similar in terms of age, height, weight, and body mass index (BMI) but were less educated (30% ≥ high school versus 45%).

Exposure Assessment

At the time of the initial interview, nonfasting blood samples were collected via venipuncture. The blood was centrifuged, serum was obtained, and fractions were frozen at −20°C until extraction. Serum was shipped on dry ice to the Harvard School of Public Health, where it was stored at −70°C until analyzed by the Harvard School of Public Health Organic Chemistry Laboratory (Boston, MA) for pp′ and op′ isomers of DDT, DDE, and DDD. Quantification was based on the response factor of each analyte relative to an external standard. Details of the laboratory analytical methods and quality control procedures are reported elsewhere [23]. Final concentrations of analytes were reported in nanograms per gram of serum after subtracting the amount of analyte measured in the procedural blank. The lipid content of the serum was not measured because serum volume was insufficient.

The nutritional analyses employed here are detailed elsewhere [24]. Briefly, frozen serum samples being stored at the Harvard School of Public Health were transported on dry ice to the Jean Mayer USDA Human Nutrition Research Center on Aging at Tufts University, Boston, MA, where concentrations of cysteine, folate, and vitamins B6 and B12 were measured. Cysteine concentration was determined by high-performance liquid chromatography [25], and folate and vitamin B12 were measured by radioimmunoassay using a commercially available kit from BioRad Diagnostics Group (Hercules, CA). Vitamin B6 (as pyridoxal 5′-phosphate) was measured by the tyrosine decarboxylase apoenzyme method [26].

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analysis included median values for age, BMI, folate, cysteine, and vitamins B6 and B12 across tertiles of total DDT in the blood serum—the sum of all the DDT isomers and metabolites. A test for trend was performed by regressing each variable onto a 0–2 ordinal scale of the tertiles of total DDT. Next, penalized splines were generated from generalized additive models [27] to determine the appropriateness of linear terms for each covariate in the regression model; generalized linear models were then used to estimate the strength of the linear association between the various nutrients and covariates with DDT isomers and metabolites. Because of issues of normality and scale, all outcomes and covariates were logarithmically transformed. Penalized splines were generated using the software package R [28], and linear regression models were estimated using Proc Mixed in SAS 8.2 [29].

Results

Table 1 shows the median total serum DDT isomers/metabolites, age, BMI, and serum folate concentrations across increasing tertiles of total DDT isomers/metabolites. The median total serum DDT values (ng/g) at low, medium, and high tertiles were 17.5, 31.5, and 55.1, respectively. Age was significantly higher across tertiles, from 24.6 years to 25.2 years (p trend = 0.004), and BMI was generally lower as tertiles increased (p trend = 0.04). Median serum folate values (nmol/L) at the low and medium tertiles were similar and were significantly lower at the high tertile (p trend = 0.02). Median cysteine (nmol/L) was consistently and significantly lower with increasing total DDT (p trend = 0.009). There was no significant trend for either vitamin B6 or B12.

Table 1. Characteristics of 296 Nonsmoking Female Textile Workers in Anhui, China, 1996–1998.

| Total Serum DDT Isomers/Metabolites Tertiles* | p Trend† | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Medium | High | ||

| N | 98 | 99 | 99 | |

| Median | ||||

| Total serum DDT isomers/metabolites (ng/g) | 18.5 | 30.8 | 51.2 | |

| Age (yr) | 24.4 | 24.8 | 24.9 | 0.004 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 19.5 | 19.9 | 19.2 | 0.043 |

| Serum folate concentration (nmol/L) | 9.2 | 9.5 | 8.5 | 0.019 |

| Serum cysteine concentration (nmol/L) | 214.2 | 200.8 | 187.2 | 0.011 |

| Serum vitamin B6 (nmol/L) | 38.0 | 39.6 | 34.7 | 0.177 |

| Serum vitamin B12 (pmol/L) | 330.2 | 339.2 | 363.3 | 0.975 |

Sum of pp′-DDT, pp′-DDE, pp′-DDD, op′-DDT, and op′-DDE.

Trend test performed on the log transforms of age, BMI, serum folate, serum cysteine, and serum B6 and B12.

Table 2 provides more detail about the distribution of the DDT isomers and metabolites measured in this study. pp′DDE had the highest concentration, and, on average, accounted for 92% of the mass of the DDT isomers measured in serum (range, 81%–98%). pp′DDT had the second highest concentration, accounting for 6% of the total DDT (range, 2%–15%). All correlations between the isomers were highly significant (p < 0.0001) and ranged from r = 0.28 between pp′DDD and op′DDE to r = 0.77 between op′DDT and op′DDE.

Table 2. Distribution and Correlation of Serum Concentrations of DDT Isomers and Metabolites in 296 Nonsmoking Female Textile Workers in Anhui, China, 1996–1998.

| Minimum | Tertile 1 | Median | Tertile 3 | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| p,p′-DDT (ng/g) | 0.4 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 2.4 | 13.1 |

| p,p′-DDE (ng/g) | 5.8 | 20.0 | 29.2 | 41.5 | 97.5 |

| p,p′-DDD (ng/g) | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.0 |

| o,p′-DDT (ng/g) | < 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.3 | 1.5 |

| o,p′-DDE (ng/g) | < 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.1 |

| Spearman correlation coefficients* | |||||

| p,p′-DDE | p,p′-DDD | o,p′-DDT | o,p′-DDE | ||

| p,p′-DDT | 0.66 | 0.76 | 0.64 | 0.38 | |

| p,p′-DDE | 0.50 | 0.53 | 0.42 | ||

| p,p′-DDD | 0.49 | 0.28 | |||

| o,p′-DDT | 0.77 |

DDT = 1,1,1-trichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl)ethane; DDE = 1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis(p-cholorphenyl) ethylene; DDD = 1,1-dichloro-2,2-bis(p-chlorophenyl)ethane.

p < 0.0001 for all Spearman correlation coefficients.

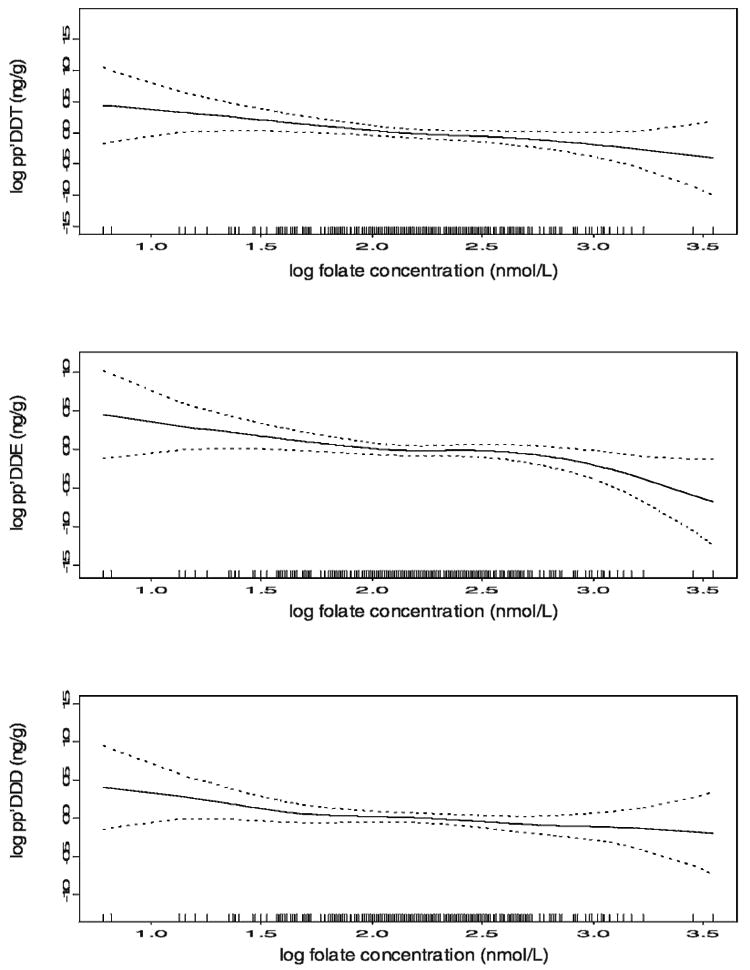

Fig. 1 shows the penalized splines from generalized additive models of log serum folate concentrations and log pp′DDT, log pp′DDE, and log pp′DDD adjusted for log transforms of cysteine, age, BMI, and vitamins B6 and B12. Because the plots of log op′DDT and log op′DDT regressed onto log serum folate were flat, they are not presented here. Log pp′DDT, log pp′DDE, and log pp′DDD all decreased as the log serum folate increased, and in a linear fashion, even after adjusting for cysteine, age, BMI, and vitamins B6 and B12.

Fig. 1.

Penalized splines (with 95% confidence limits) from generalized additive models of log folate concentration and log pp′DDT, pp′DDE, and pp′DDD adjusted for log transforms of cysteine, age, BMI, and vitamins B6 and B12.

Table 3 shows the crude and adjusted linear associations between the log DDT isomers/metabolites and log serum folate and cysteine. In the crude model, log serum folate was significantly inversely associated with log pp′DDT, log pp′DDE, and log pp′DDD: β (95% CI) = −0.26 (−0.41, −0.10); −0.22 (−0.36, −0.07); and −0.16 (−0.29, −0.02), respectively. The log serum cysteine was significantly inversely associated with log pp′DDT, log pp′DDE, log pp′DDD, and log op′DDT: β (95% CI) = −0.70 (−1.00, −0.41); −0.44 (−0.72, −0.16); −0.32 (−0.58, −0.07); and −0.32 (−0.62, −0.02), respectively. In the adjusted models, which included log transforms of folate, cysteine, age, BMI, and vitamins B6 and B12, log serum folate was significantly inversely associated with log pp′DDT and log pp′DDE—β (95% CI) = −0.23 (−0.39, −0.07) and −0.20 (−0.36, −0.05), respectively—and marginally associated with pp′DDD: β (95% CI) = −0.14 (−0.29, 0.001). Cysteine was also significantly inversely associated with pp′DDT: β (95% CI) = −0.69 (−1.00, −0.37); pp′DDE: β (95% CI) = −0.32 (−0.62, −0.02); pp′DDD: β (95% CI) = −0.31 (−0.59, −0.03); and op′DDT: β (95% CI) = −0.35 (−0.68, −0.02) in the adjusted models.

Table 3. Linear Associations of Serum Folate and Cysteine with Serum DDT Isomers and Metabolites in 296 Nonsmoking Female Textile Workers in Anhui, China, 1996–1998.

| Log Folate and Cysteine Concentrations (nmol/L) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude | Adjusted* | |||||||

| Folate | Cysteine | Folate | Cysteine | |||||

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | |

| log p,p′-DDT | −0.26 | 0.001 | −0.70 | < .0001 | −0.23 | 0.006 | −0.69 | < .0001 |

| log p,p′-DDE | −0.22 | 0.003 | −0.44 | 0.002 | −0.20 | 0.01 | −0.32 | 0.040 |

| log p,p′-DDD | −0.16 | 0.022 | −0.32 | 0.012 | −0.14 | 0.052 | −0.31 | 0.031 |

| log o,p′-DDT | −0.06 | 0.430 | −0.32 | 0.035 | −0.03 | 0.730 | −0.35 | 0.035 |

| log o,p′-DDE | −0.01 | 0.846 | −0.12 | 0.359 | 0.00004 | > 0.99 | −0.12 | 0.409 |

Models include log transforms of serum folate, cysteine, age, BMI, and vitamins B6 and B12.

Discussion

The present study found significant inverse associations between serum concentrations of folate and serum concentrations of pp′DDT and pp′DDE and significant inverse associations between serum concentrations of cysteine and pp′DDT, pp′DDE, pp′DDD, and op′DDT in this sample of 296 female textile workers. Linear declines in serum pp′DDT and pp′DDE across increasing levels of serum folate were independent of the linear declines in serum pp′DDT, pp′DDE, pp′DDD, and op′DDT across increasing levels of serum cysteine, while adjusting for serum concentrations of vitamins B6 and B12, age, and BMI.

It is well known that organochlorinated pesticides (OCPs) are absorbed through food. Studies in several countries have shown that DDT is present in various food substances, such as animal fat, butter, cheese, milk, oils, cereals, spices, fruit, and vegetables [30]. Larger quantities of DDT are stored in meat, such as beef and lamb, and fish [31]. A recent study of dietary intake and other lifestyle factors among 250 healthy women who participated as controls in the Shanghai Breast Cancer Study found that serum concentration of pp′DDE was positively correlated with intake of peanuts and negatively correlated with fresh beans (soy, pea, and green) and watermelon, while pp′DDT was negatively correlated with intake of rice and fresh beans and positively correlated with meat, poultry, animal fat, and soy oil [32].

Few studies have assessed the role of nutritional factors in OCP metabolism or how OCPs might affect nutrition. Considering the former, studies in rats did not find that vitamins A, D, or E decreased the body burden of DDT [33]. However, a review by Jaga and Duvvi [34] described how phytoestrogens, curcumin, and indol-3-carbinol might reduce the carcinogenic effects of DDT. For example, phytoestrogens, found in soybeans and whole grains, and curcumin (diferuloylmethane), a major component of the turmeric that is widely used in Indian dishes, inhibit the proliferation of cultured human breast cancer cells (MCF-7) induced by DDT by competing for estrogen receptor sites. Folate, which is naturally present in foods such as liver, fruits, vegetables, and soy products, participates in numerous reactions involving the transfer of methyl units. For instance, in arsenic detoxification, arsenic is enzymatically converted first to monomethylarsonic acid (MMA) and then to dimethylarsinic acid (DMA) in a series of folate-dependent methylation reactions that increase urinary arsenic excretion [35]. In a clinical trial, Gamble et al. [36] showed that in urine, the percentage of the less toxic DMA was positively associated with serum folate and the more toxic MMA was negatively associated with serum folate, suggesting that folate status influences arsenic methylation and in vivo toxicity. By analogy, it is possible that folate status could influence DDT and DDE metabolism in a similar fashion by affecting methylation reactions that may be folate-dependent [6]. Methylsulfonyl metabolites of DDT have been identified in human and several animal species. These compounds are thought to be produced through a series of reactions in which DDE-glutathione conjugates are degraded and excreted into bile. In the large intestine, these compounds are subsequently cleaved by a microbial lyase, and the resulting thiols are methylated and reabsorbed into the bloodstream [3]. Although folate participates in numerous methylation reactions, its role in DDT metabolism has not been established.

The present study also found that cysteine concentration was inversely associated with DDT isomers and metabolites. Cysteine is a component of most proteins and is synthesized in the body from methionine (and homocysteine) in a series of vitamin B6–dependent transsulfuration reactions. In addition to its role in proteins, cysteine is also a reducing agent and a component of the tripeptide glutathione, which serves as a cellular antioxidant and as the substrate for enzymes that form glutathione conjugates with various xenobiotic compounds, including DDE [3,37]. Strong inverse associations were observed between cysteine and pp′DDT, pp′DDE, pp′DDD, and op′DDT. Consistent with the present findings, Langen et al. [16] showed in vitro that a mixture of hemin and excess cysteine was able to partially degrade DDT. Although the concentration of cysteine in tissues is much lower than the concentration used in this in vitro system, this finding suggests that cysteine, along with other amino acids, could influence the metabolism and excretion of DDT in vivo.

Conversely, DDT might exert a negative effect on nutritional factors. Although no studies have reported this with regard to folate or cysteine levels, some studies have investigated the effect of OCPs on other nutrients. For instance, the long-term administration of PCB and DDT can result in a deficiency of the B vitamin thiamine [38], which can lead to beriberi and a number of other symptoms with varying degrees of severity. The present findings suggest that DDT decreases folate or cysteine, and deficiencies in folate can lead to megaloblastic anemia, neurological disorders, birth defects, occlusive vascular disease, and an increased risk of colonic polyposis [39]. Deficiencies in cysteine can lead to an increased risk of Alzheimer's and Parkinson's diseases, heart attack, stroke, diabetes, and infected states such as HIV [40]. Further investigations are needed to clarify the specific mechanisms through which folate and cysteine status may influence DDT metabolism, or vice versa. This could prove to be a fruitful area for research.

The main strengths of the present study are the robust sample size and serum measures of environmental DDT isomers and metabolites and the various nutritional factors examined. Additionally, this study population was young, healthy, nonsmoking, and relatively homogenous with respect to social and demographic characteristics.

An important limitation of this study is that it did not focus on nutrition or DDT exposure, and participants did not fast prior to the blood draw. Although the body-burden of DDT and its metabolites should be more closely associated with long-term rather than recent exposure, blood lipid, folate and cysteine would all be closely associated with the content and timing of the previous meal. It is possible that a recent intake of folate misclassified some women as normal or high in folate, so if the present findings are biased away from the null, this means that individuals in this study with low DDT tended to have a more recent meal prior to blood draw, and adjustment for time of dietary intake prior to blood draw would likely weaken the association. However, if the timing of dietary intake was similar across all individuals, then adjustment for timing of dietary intake prior to blood draw would strengthen the negative association found herein. Although information regarding the meal prior to the blood draw was not collected, cuisine in this part of China ordinarily includes both meats and vegetables in the same meal. All women in this study worked in the same textile mills and so were of similar socioeconomic status and ate in the same employer cafeterias. Another limitation of this analysis was that there was not sufficient serum available to measure lipids. Because DDT and its metabolites are lipophilic and partition between lipid compartments found in blood and other tissues, and the amount of DDT detected in blood on a wet-weight basis (not adjusted for lipids) increases when blood lipid concentration increases, the findings of negative associations between DDT and its metabolites with both folate and cysteine might have been confounded by unmeasured blood lipid. If individuals who had higher blood lipids because of a recent meal also tended to have higher folate and cysteine, then the associations would have been biased toward the null, and the negative associations observed might have actually been of greater magnitude. However, if individuals who had higher blood lipids tended to have lower folate and cysteine, the observed associations might have been biased away from the null, and the negative associations observed here might have actually been of lesser magnitude or nonexistent. As such, confounding bias toward the null is more expected; however, this is not certain. Another possible source of confounding bias away from the null would have occurred if either folate or cysteine increased metabolism of lipids; however, there is no evidence that this is true. In fact, folate supplementation (0.8 mg/d) had no effect on lipid concentrations in randomized, placebo-controlled studies of healthy humans [41–43].

It is well known that both folate deficiency and high DDT exposure each lead to poor health outcomes, particularly reproductive health outcomes, but it is not well studied how these might relate to each other. The present cross-sectional results cannot provide causal evidence, but they suggest two hypotheses: (1) folate and cysteine may increase metabolism and excretion of DDT and its metabolites, and (2) DDT decreases the levels of folate and cysteine in the body. Although DDT has been banned in most countries, it is still used in some for malarial vector control [7–10], and its persistence in the environment leads to continued human exposure even after its use has stopped [5]. Furthermore, because DDT has a long half-life in humans, the body burden of its residues remains long after exposure [13]. A nationwide folic acid and B-vitamin deficiency intervention program in China is ongoing [44], which could also be an opportunity to further examine the link between DDT and folic acid. Further research is warranted because of the public health implications of this finding.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by grant R01ES11682 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and grants R01HD32505 and R01HD41702 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

References

- 1.Ioannides C. Enzyme Systems that Metabolize Drugs and Other Xenobiotics. Chichester, UK: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klaassen C, Watkins J., III . Casarett & Doull's Essentials of Toxicology. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry (ATSDR) Toxicological Profile for DDT, DDE, DDD. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Longnecker MP, Rogan WJ, Lucier G. The human health effects of DDT (dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane) and PCBS (polychlorinated biphenyls) and an overview of organochlorines in public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1997;18:211–244. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.18.1.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.IARC . Occupational Exposures in Insecticide Application, and Some Pesticides. Lyon, France: IARC; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry . Toxicological Profile for DDT, DDE, and DDD. Atlanta: Department of Health and Human Services; 2002. pp. 2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salazar-Garcia F, Gallardo-Diaz E, Ceron-Mireles P, Loomis D, Borja-Aburto VH. Reproductive effects of occupational DDT exposure among male malaria control workers. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112:542–547. doi: 10.1289/ehp.112-1241918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalvie MA, Myers JE. The relationship between reproductive outcome measures in DDT exposed malaria vector control workers: a cross-sectional study. J Occup Med Toxicol. 2006;1:21. doi: 10.1186/1745-6673-1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamau L, Vulule JM. Status of insecticide susceptibility in Anopheles arabiensis from Mwea rice irrigation scheme, Central Kenya. Malar J. 2006;5:46. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vatandoost H, Mashayekhi M, Abaie MR, Aflatoonian MR, Hanafi-Bojd AA, Sharifi I. Monitoring of insecticides resistance in main malaria vectors in a malarious area of Kahnooj district, Kerman province, southeastern Iran. J Vector Borne Dis. 2005;42:100–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cook BK, Stringer A. Distribution and breakdown of DDT in orchard soil. Pesticides Sci. 1982;13:545–551. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang Y, Yang DJ, Fang CR, Wei KK. Monitoring of organochlorine pesticide residues—the GEMS/Food Program in China. Biomed Environ Sci Am. 1997;10:102–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colborn T, vom Saal FS, Soto AM. Developmental effects of endocrinedisrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Environ Health Perspect. 1993;101:378–384. doi: 10.1289/ehp.93101378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mutter LC, Blanke RV, Jandacek RJ, Guzelian PS. Reduction in the body content of DDE in the Mongolian gerbil treated with sucrose polyester and caloric restriction. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1988;92:428–435. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(88)90182-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davis DL, Bradlow HL. Can environmental estrogens cause breast cancer. Sci Am. 1995;273:167–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Langen H, Epprecht T, Linden M, Hehlgans T, Gutte B, Buser HR. Rapid partial degradation of DDT by a cytochrome P-450 model system. Eur J Biochem. 1989;182:727–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb14885.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Horio F, Kimura M, Yoshida A. Effect of several xenobiotics on the activities of enzymes affecting ascorbic acid synthesis in rats. J Nutr Sci Vitaminol (Tokyo) 1983;29:233–247. doi: 10.3177/jnsv.29.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nilsson CB, Hoegberg P, Trossvik C, Azaïs-Braesco V, Blaner WS, Fex G, Harrison EH, Nau H, Schmidt CK, van Bennekum AM, Håkansson H. 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin increases serum and kidney retinoic acid levels and kidney retinol esterification in the rat. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2000;169:121–131. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brouwer A, Reijnders PJH, Koeman JH. Polychlorinated biphenyl (PCB)-contaminated fish induces vitamin A and thyroid hormone deficiency in the common seal Phoca vitulina. Aquat Toxicol. 1989;15:99–106. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ronnenberg AG, Venners SA, Xu X, Chen C, Wang L, Guang W, Huang A, Wang X. Preconception B-vitamin and homocysteine status, conception, and early pregnancy loss. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;166:304–312. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Venners SA, Korrick S, Xu X, Chen C, Guang W, Huang A, Altshul L, Perry M, Fu L, Wang X. Preconception serum DDT and pregnancy loss: a prospective study using a biomarker of pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2005;162:709–716. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwi275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang X, Chen C, Wang L, Chen D, Guang W, French J. Conception, early pregnancy loss, and time to clinical pregnancy: a population-based prospective study. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:577–584. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korrick SA, Altshul LM, Tolbert PE, Burse VW, Needham LL, Monson RR. Measurement of PCBs, DDE, and hexachlorobenzene in cord blood from infants born in towns adjacent to a PCB-contaminated waste site. J Expo Anal Environ Epidemiol. 2000;10:743–754. doi: 10.1038/sj.jea.7500120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ronnenberg AG, Goldman MB, Chen D, Aitken IW, Willett WC, Selhub J, Xu X. Preconception homocysteine and B vitamin status and birth outcomes in Chinese women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:1385–1391. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Araki A, Sako Y. Determination of free and total homocysteine in human plasma by high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. J Chromatogr. 1987;422:43–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-4347(87)80438-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin YS, Rasshofer R, Friedrich B, Endres W. Pyridoxal-5′-phosphate determination by a sensitive micromethod in human blood, urine and tissues; its relation to cystathioninuria in neuroblastoma and biliary atresia. Clin Chim Acta. 1983;127:77–85. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(83)90077-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wand MP. Smoothing and mixed models. Comput Stat. 2003;18:223–249. [Google Scholar]

- 28.The R Development Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS Software . Version 8.2. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaphalia BS, Takroo R, Mehrotra S, Nigam U, Seth TD. Organochlorine pesticide residues in different Indian cereals, pulses, spices, vegetables, fruits, milk, butter, Deshi ghee, and edible oils. J Assoc Off Anal Chem. 1990;73:509–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.DeVoto E, Kohlmeier L, Heeschen W. Some dietary predictors of plasma organochlorine concentrations in an elderly German population. Arch Environ Health. 1998;53:147–155. doi: 10.1080/00039896.1998.10545976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee S, Dai Q, Zheng W, Gao YT, Blair A, Tessari JD, Tian Ji B, Shu XO. Association of serum concentration of organochlorine pesticides with dietary intake and other lifestyle factors among urban Chinese women. Environ Int. 2007;33:157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2006.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phillips WE, Hatina GV, Villeneuve DC, Grant DL. Effect of dietary supplements of vitamins A, D, and E on body burdens of DDT in the rat. J Agric Food Chem. 1971;9:780–784. doi: 10.1021/jf60176a037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jaga K, Duvvi H. Risk reduction for DDT toxicity and carcinogenesis through dietary modification. J R Soc Health. 2001;121:107–113. doi: 10.1177/146642400112100212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kile ML, Ronnenberg AG. Can folate intake reduce arsenic toxicity. Nutr Rev. 2008;66:349–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2008.00043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gamble MV, Liu X, Ahsan H, Pilsner JR, Ilievski V, Slavkovich V, Parvez F, Chen Y, Levy D, Factor-Litvak P, Graziano JH. Folate and arsenic metabolism: a double-blind, placebo-controlled folic acid-supplementation trial in Bangladesh. Am J Clin Nutr. 2006;84:1093–1101. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/84.5.1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stipanuk MH, Watford M. Amino acid metabolism. In: Stipanuk MH, editor. Biochemical, Physiological, and Molecular Aspects of Human Nutrition. 2nd. St Louis: Saunders-Elsevier; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yagi N, Kamohara K, Itokawa Y. Thiamine deficiency induced by polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) and dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane (DDT) administration to rats. J Environ Pathol Toxicol. 1979;2:1119–1125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Haslam N, Probert CS. An audit of the investigation and treatment of folic acid deficiency. J R Soc Med. 1998;91:72–73. doi: 10.1177/014107689809100205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu G, Fang YZ, Yang S, Lupton JR, Turner ND. Glutathione metabolism and its implications for health. J Nutr. 2004;134:489–492. doi: 10.1093/jn/134.3.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olthof MR, van Vliet T, Verhoef P, Zock PL, Katan MB. Effect of homocysteine-lowering nutrients on blood lipids: results from four randomised, placebo-controlled studies in healthy humans. PLoS Med. 2005;2:E135. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Title LM, Ur E, Giddens K, McQueen MJ, Nassar BA. Folic acid improves endothelial dysfunction in type 2 diabetes—an effect independent of homocysteine-lowering. Vasc Med. 2006;11:101–109. doi: 10.1191/1358863x06vm664oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wasilewska A, Narkiewicz M, Rutkowski B, Lysiak-Szydlowska W. Is there any relationship between lipids and vitamin B levels in persons with elevated risk of atherosclerosis. Med Sci Monit. 2003;9:CR147–CR151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cordero JF, Do A, Berry RJ. Review of interventions for the prevention and control of folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies. Food Nutr Bull. 2008;29(2 suppl):S188–S195. doi: 10.1177/15648265080292S122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]