Abstract

Three experiments investigated how font emphasis influences reading and remembering discourse. Although past work suggests that contrastive pitch contours benefit memory by promoting encoding of salient alternatives, it is unclear both whether this effect generalizes to other forms of linguistic prominence and how the set of alternatives is constrained. Participants read discourses in which some true propositions had salient alternatives (e.g., British scientists found the endangered monkey when the discourse also mentioned French scientists) and completed a recognition memory test. In Experiments 1 and 2, font emphasis in the initial presentation increased participants’ ability to later reject false statements about salient alternatives but not about unmentioned items (e.g., Portuguese scientists). In Experiment 3, font emphasis helped reject false statements about plausible alternatives, but not about less plausible alternatives that were nevertheless established in the discourse. These results suggest readers encode a narrow set of only those alternatives plausible in the particular discourse. They also indicate that multiple manipulations of linguistic prominence, not just prosody, can lead to consideration of alternatives.

Keywords: discourse, recognition memory, reading, alternative sets, fonts

Understanding and remembering a discourse may involve representing not only what is true but also salient alternative propositions that are not true. For instance, Fraundorf, Watson, and Benjamin (2010) reported evidence that certain prosodic contours in spoken discourse, described in detail below, led listeners to encode information about a salient alternative in the discourse, such as The Scottish knight won as an alternative to The English knight won in (1b). This information helped listeners remember the events of the discourse. In particular, remembering that the Scottish knight lost the tournament helped listeners later reject Scottish as the winner. But, it did not affect their ability to reject an unmentioned item like Welsh, which was never part of a salient alternative in the discourse.

-

(1a)

The English and the Scottish knights held a jousting tournament.

-

(1b)

The ENGLISH knight won.

But while there is general evidence that important alternatives may be encoded as part of a discourse representation, it is unclear exactly how that set of alternatives is defined. Comprehenders might consider a relatively broad set of alternatives, such as alternative propositions related to any discourse entities in the same semantic category. Alternately, they might consider only those alternative propositions that are made particularly salient or plausible in the discourse.

It is similarly unclear what cues lead comprehenders to encode these alternative sets. Fraundorf et al. (2010) manipulated a feature that might be particularly apt to influence whether comprehenders consider a salient alternative: the type of prosodic pitch accent. The ToBI system for prosodic transcription (Beckman & Elam, 1997; Silverman et al., 1992) distinguishes multiple types of prosodic pitch accents that are argued to have different meanings. For instance, H* pitch accents consist of a single high pitch target (H) on the stressed syllable of the word (*) and are broadly associated with new information. L+H* pitch accents consist of a low pitch target (L) followed by a rise to a high pitch target on the stressed syllable, are acoustically more prominent (Selkirk, 2002), and have been argued to have a contrastive reading (Pierrehumbert & Hirschberg, 1990; see also Gussenhoven, 1983, for similar arguments in a somewhat different system of prosodic transcription).

Representation of salient alternatives in memory might be expected to occur only when listeners hear particular prosodic cues such as the L+H* accent—and not, for instance, in written text. However, readers may generate implicit prosody even when reading silently (Fodor, 1998; Breen & Clifton, 2010). Moreover, other theoretical accounts (Calhoun, 2009) have proposed that when linguistic material is made more prominent than expected in any way, it brings to mind relevant alternatives. Under both these accounts, the representation of salient alternatives in memory could be observed even in written discourse as a function of cues other than overt prosody.

In three experiments, we investigated whether salient alternative propositions are represented in memory when reading written discourse, and tested how the set of alternatives is constrained by readers. Experiments 1 and 2 tested whether the specific memory benefits previously observed for L+H* pitch accents could also be obtained in written discourse as a function of a different manipulation: italicization or capitalization, which we refer to collectively as font emphasis1. Experiment 3 tested whether the alternatives represented included any possible alternative proposition that could be formed from the discourse or only those that, given the scenario in the discourse, were particularly likely alternatives. Experiments 2 and 3 also collected measures of reading time to determine whether the benefits of font emphasis were contingent on how readers initially read the emphasized words.

Representing Alternatives in a Discourse

Success in discourse comprehension may involve representing not only particular referents and propositions, but also calculating and representing a set of one or more salient alternatives (e.g., Blok & Eberle, 1999; Calhoun, 2009; Pierrehumbert & Hirschberg, 1990 Rooth, 1992; Selkirk, 1995; Steedman, 2000). For instance, Rooth (1992) has argued that placing a linguistic constituent in focus introduces a focus semantic value, which expands the semantic interpretation of a sentence by introducing a set of one or more alternative propositions2. The alternative set has been formalized as a set of propositions that could have been formed had the focused element been replaced by something else, but that, given the actual proposition, cannot be true (e.g., Rooth, 1992; Steedman, 2000; Van Deemter, 1999).

For example, (2) expresses the proposition that elaborative rehearsal should be used to maximize cognition. (Capitalization indicates an L+H* pitch accent.) According to accounts of contrastive prosody (e.g., Pierrehumbert & Hirschberg, 1990), the contrastive L+H* accent on elaborative conveys that it is indeed elaborative rehearsal rather than some other form of rehearsal that should be used to maximize cognition. That is, it relates the true proposition to a set of alternative propositions, such as If you want to maximize cognition, use maintenance rehearsal, that could have been formed by replacing elaborative with other potential modifiers for rehearsal. Speakers and writers may introduce alternatives in this manner for multiple reasons, commonly including the desire to call attention to the contrast between two outcomes (Gundel, 1999; Rooth, 1992).

-

(2)

If you want to maximize cognition, use ELABORATIVE rehearsal.

Some evidence suggests consideration of alternatives can benefit how a discourse is represented and remembered over the long term. Fraundorf et al. (2010) presented participants with spoken discourses in which the first part of the discourse, which we term the context passage, established two pairs of items. For example, (3a) below mentioned British and French as one pair and Malaysia and Indonesia as a second pair. (Fraundorf et al. included two pairs per discourse to test whether improving memory for one pair would come at a cost to memory for the other, but no such effects were observed.) A second part of the discourse, which we term the continuation, mentioned one member of each pair. For instance, (3b) mentions British from the first pair and Malaysia from the second pair.

-

(3a)

Both the British and the French biologists had been searching Malaysia and Indonesia for the endangered monkeys.

-

(3b)

Finally, the British spotted one of the monkeys in Malaysia and planted a radio tag on it.

Each pair was created so that a proposition in the continuation would have a salient alternative. For example, the pairing of British and French in (3a) makes it plausible that the French, rather than the British, could have spotted the monkey in (3b). In the accounts proposed by Rooth (1992), Steedman (2000), and others, the salient alternative The French spotted one of the monkeys should thus be considered if British is made prominent in (4b).

Fraundorf et al. (2010) tested whether listeners encoded the salient alternative by manipulating whether the key word in the continuation received the L+H* pitch accent described above, which is argued to contrast one item with an alternative or alternatives, or received the H* pitch accent, which is more broadly associated with new information (Pierrehumbert & Hirschberg, 1990). The contrastive L+H* pitch accent indeed appeared to lead participants in the Fraundorf et al. (2010) study to actively encode and remember a salient alternative to the truth. A day after listening to the stories, participants took a recognition memory test that included three types of probes: correct statements, such as (4a), alternative probes that referred to items that were part of the original pairing in the discourse, such as (4b), and unmentioned probes that referred to items never present in the original discourse, such as (4c).

-

(4a)

The British scientists found the endangered monkey.

-

(4b)

The French scientists found the endangered monkey.

-

(4c)

The Portuguese scientists found the endangered monkey.

Both the alternative and unmentioned probes were false statements that were to be rejected, but they differed in whether or not they expressed a proposition that was likely to be in the alternative set. Alternative probes referred to the salient alternative in the original discourse and should be part of any set of alternatives to the true proposition, whereas the unmentioned probes referred to a brand new item and should not. Hearing the contrastive L+H* accent, rather than an H* accent, in the original continuation improved participants’ ability to reject the alternative probes. Crucially, however, it did not improve rejections of the unmentioned probes. This suggests that the memory benefit of the contrastive L+H* accent over the H* accent was not simply due to improved encoding of the target item, which could allow it be more easily discriminated from any false probe. Rather, the difference between the L+H* and H* likely involved listeners representing something about the salient alternative, such as remembering that it was not the French scientists who found the monkey. Such a representation would allow the salient alternative to be more easily rejected, but knowing that the French scientists did not find the monkey would not help reject a proposition relating to an unmentioned item (the Portuguese scientists found the monkey).

How are Alternative Sets Constrained?

Although there is general evidence that alternatives in a discourse are represented and remembered, one unresolved issue is which alternatives comprise the alternative set. In most cases, it seems unlikely that comprehenders would consider every possible alternative proposition. For example, (5b) is an alternative to (5a) below in that it is formed by replacing the constituent British and constitutes a proposition that cannot be true if (5a) is true. However, it seems implausible that comprehenders would actually consider and encode (5b) as an alternative in online language comprehension. (Indeed, the results of Fraundorf et al. 2010 support this claim, as the contrastive L+H* accent did not benefit rejections of entirely unmentioned items.) Thus, most theoretical accounts (e.g., Rooth, 1992; Steedman, 2000; Van Deemter, 1999) have assumed that the alternative set must be constrained by context.

-

(5a)

The British scientists found the endangered monkey.

-

(5b)

The Martian scientists found the endangered monkey.

How the context constrains the alternative set, however, is unclear. One hypothesis is that context only loosely restricts the alternative set. Comprehenders might consider as alternatives any proposition that could be created by replacing the prominent item with some other item of the same semantic or syntactic category. This possibility is consistent with models in which the selection of an alternative set is strongly influenced by hierarchical taxonomies of concepts (e.g., Blok & Eberle, 1999): any discourse element that is part of the same superordinate category may be a relevant alternative. It is also consistent with effects in other linguistic domains that have been attributed to givenness or presence in the discourse (e.g., Bock & Mazzella, 1983; Halliday, 1967; Haviland & Clark, 1974).

A different hypothesis is that the set of alternatives is constrained not just by generic knowledge but by a situation model of the particular state of affairs described by an individual discourse (Zwaan & Radvansky, 1998). Some experiments suggest that the situation to which a discourse refers can narrowly restrict sets of relevant alternatives. For instance, referring expressions that are in principle ambiguous (e.g., the green block when multiple green blocks are present) can be unambiguously interpreted as referring to a single referent if the alternatives are task-irrelevant or physically distant, preventing them from being considered (Brown-Schmidt & Tanenhaus, 2008). The discourse can provide such constraints even when it does not concern physically co-present objects: electrophysiological evidence suggests that if one of two characters in a story is described as leaving the room, an otherwise ambiguous referring expression is treated as unambiguous (Nieuwland, Otten, & Van Berkum, 2007). Although these experiments have focused on how the correct referent of a referring expression is identified, they also suggest that the set of alternatives considered is relatively small and is constrained by the particular scenario described by the discourse. Further evidence that the situation model, and not merely generic knowledge, can define alternative sets comes from evidence that context can introduce new members into an alternative set from outside the same taxonomic category (Byram Washburn, Kaiser, & Zubizarreta, 2011).

The original experiments by Fraundorf et al. (2010) could not tease apart these two hypotheses about how alternative sets are constrained. In their recognition memory test, correct rejections of a highly salient alternative were compared to correct rejections of a completely unmentioned referent. As noted above, the contrastive L+H* accent benefited the former type of correct rejection but not the latter, suggesting its effect lay in encoding of the salient alternative. However, this benefit would have obtained regardless of whether the alternative set was fixed narrowly to include only the most plausible propositions given situation model or fixed more broadly to include propositions referring to any discourse element of the same semantic category. Both of these sets would have excluded the completely unmentioned item.

In other situations, how an alternative set is constrained would have consequences for how a discourse is remembered: Some propositions may refer to items that are mentioned in the discourse but that may be less likely alternatives given the situation model. For example, consider the context passage (6a) and the continuation (6b) below. Both Saturn and Neptune are mentioned in the context passage, but differ in their relationship to the true proposition regarding Jupiter in (6b). Saturn is mentioned in the context passage as part of the same pair as Jupiter and is likely part of a salient alternative proposition (i.e., the photos taken of Saturn could have been lost instead). However, the discourse establishes that Neptune is a less likely alternative for Jupiter in (6b) because the mission to Neptune had not yet occurred.

-

(6a)

Originally, the space probe Cosmo III was designed to fly past Jupiter and Saturn and send photos and measurements back to NASA from both planets. NASA needed this information to guide the videos they were going to take of Neptune on a future mission.

-

(6b)

However, due to a glitch in the programming of the Cosmo III, it lost the photos taken of Jupiter and put the future mission in trouble.

Discourses like this provide an avenue for testing what constrains the set of encoded alternatives. If the alternative set comprises only the alternative or alternatives that are particularly plausible given the situation model, then encoding an alternative set should benefit later rejections of a false prposition involving the plausible alternative (e.g., Saturn in the above example), but not one involving a mentioned but implausible alternative (Neptune). However, if the alternative set is defined to encompass all given referents of the same semantic category, then both types of correct rejections should benefit from encoding the alternative set.

Emphasis in Written Text

A second unresolved issue is what cues lead comprehenders to encode an alternative set, and whether these effects are unique to spoken prosody. Although the memory effects observed by Fraundorf et al. (2010) were obtained using contrastive L+H* pitch accents, a generalization to other manipulations, including those in written text, would be predicted by multiple accounts of prosody. One account of the memory effects observed by Fraundorf et al. (2010) is that the meaning of specific pitch contours such as the L+H* to introduce or call to mind salient alternatives (Gussenhoven, 1983; Pierrehumbert & Hirschberg, 1990). Although the L+H* accent is not explicitly presented in a written discourse, readers appear to generate implicit prosody when reading silently (Breen & Clifton, 2010; Fodor, 1998) and linguistic devices in written discourse could plausibly lead readers to implicitly generate a L+H* pitch contour. A contrastive effect in written text would also be predicted by an account (e.g., Calhoun, 2009) in which contrastive interpretations are not the inherent meaning of particular linguistic categories but occur probabilistically. The greater the linguistic prominence of a word relative to expectations, the more likely it is to bring to mind a set of salient alternatives (Calhoun, 2009), where prominence3 is broadly defined to include prosodic, syntactic, discursive, and other variables that indicate the importance of linguistic elements to a reader or listener (Birch & Rayner, 2010). Such a theory also predicts that manipulations in written text that increase the perceived prominence or importance of particular elements of the text would lead to the representation of salient alternatives.

Thus, it is plausible that readers could encode and remember salient alternatives in reading text. However, many prior studies on the processing of salient alternatives in text have focused on online processing or on metalinguistic judgments, and it is unclear if the influence on long-term memory for a discourse requires the explicit presentation of contrastive L+H* pitch accents. In the present study, we investigated whether font emphasis would lead to the representation of salient alternatives in memory.

Some existing evidence does suggest that font emphasis can indicate contrast. McAteer (1992) asked participants to freely describe the “meaning” of capitalized text and of italicized text and found that the most commonly used word in describing italicization (but not capitalization) was “contrast”. To date, however, findings have been mixed as to whether this apparent contrastive interpretation actually benefits comprehension. Emphasizing text using font changes has sometimes been observed to improve memory for a variety of materials, including short discourses (Sanford, Sanford, Molle, & Emmott, 2006), confusable drug names (Filik, Purdy, Gale, & Gerrett, 2006) and science texts (Golding & Fowler, 1992; Lorch, Lorch, & Klusewitz, 1995). But in other cases, no benefit of font emphasis has been observed (Harp & Mayer, 1998). The hypothesis that font emphasis leads readers to encode an alternative set provides one explanation for these inconsistencies: remembering salient alternatives would benefit performance on some memory tests—those that required ruling out those alternatives—but not others.

It should be noted that prior studies of font emphasis have also frequently differed in the specific font changes used, and particular font manipulations may differ in their effectiveness or in their interpretation. For example, Filik et al. (2006) found that capital letters benefited memory more than did colored text. McAteer (1992) found that participants frequently used the word “contrast” to describe the meaning of italicization but rarely used this word to describe capitalization, although this metalinguistic task does not necessarily reflect differences in online interpretation. To assess the generality of any effects in the present experiments across font manipulations, we separately tested two different manipulations: capital letters and italicization.

Reading Time and Depth of Processing

An additional benefit of assessing comprehension using written discourses is that participants’ reading time provides a measure of their initial, online processing of the discourse. The representation of alternative sets in memory may be contingent on the online processing of the emphasized material. For instance, Rooth (1992) has argued that fixing a focus semantic value, which includes the set of alternatives, is an optional process and not always performed. One plausible reason why readers might not always calculate an alternative set is that this, and other aspects of language processing, may be time-consuming. The need to interpret a sentence in time for the interpretation to be useful for the task at hand may prevent readers from spending the time to construct the most detailed linguistic representation possible (Ferreira & Patson, 2007; Sanford & Sturt, 2002). Indeed, research on human memory has established that, under time constraints, learners may not attempt to fully master all material (Son & Metcalfe, 2000; Thiede & Dunlosky, 1999). An important determinant of later memory is whether particular items preferentially receive additional study time (Dunlosky & Connor, 1997; Tullis & Benjamin, 2010). It is possible that the degree to which readers invest time in determining the alternative set when initially reading the discourse might partially explain variation in the accuracy of their later memory.

To date, however, findings are mixed as to whether the depth of discourse representations is indeed mediated by online processing. In some cases, longer reading times predict a greater probability of successful comprehension (Caplan, DeDe, Waters, Michaud, & Tripodis, 2011; Daneman, Lennertz, & Hannon, 2007). In other cases, no such relations are observed (Christianson & Luke, 2011; Reder & Kusbit, 1991; Ward & Sturt, 2007), which has led to the suggestion that deeper encoding does not necessarily require more online processing time (Ward & Sturt, 2007). Thus, it is unclear whether the representation of salient alternatives in memory would be predicted by readers’ online processing of the original discourse.

Present Work

In three experiments, we tested both whether font emphasis would lead readers to remember a set of one or more salient alternative propositions and how this set of alternatives is constrained.

In Experiment 1, we first tested whether font emphasis could improve rejections of a plausible alternative proposition about a discourse, as reported by Fraundorf et al. (2010) for contrastive (L+H*) pitch accents. To preview, both italics and capitals benefited memory in the same way that the L+H* accents did in the Fraundorf et al. study: they improved correct rejections of the salient alternative but not of a proposition about an unmentioned item. This pattern suggests that readers had encoded that particular alternative. Experiment 2 replicated this effect and also assessed whether or not representing the salient alternative in memory required additional online reading time.

Finally, in Experiment 3, we tested whether the set of alternatives is constrained only by prior mention in the discourse or also by plausibility in the situation model. We compared the benefits of font emphasis in rejecting two types of false statements: a false statement about an plausible alternative in the discourse and a false statement about referent that was mentioned in the discourse but that formed a less plausible alternative for the true proposition.

Experiment 1

We first tested whether font emphasis would benefit memory for discourse and whether those benefits would lie specifically in rejecting a salient alternative proposition, as reported by Fraundorf et al. (2010) for contrastive (L+H*) pitch accents. Recall that in those experiments, the key comparison was how a contrastive accent in discourses such as (3), reproduced below, affected later responses to three types of memory probes, reproduced below as (4).

-

(3a)

Both the British and the French biologists had been searching Malaysia and Indonesia for the endangered monkeys.

-

(3b)

Finally, the BRITISH spotted one of the monkeys in Malaysia and planted a radio tag on it.

-

(4a)

The British scientists found the endangered monkey.

-

(4b)

The French scientists found the endangered monkey.

-

(4c)

The Portuguese scientists found the endangered monkey.

The crucial distinction in this design is between probes that expressed a salient alternative proposition from the original discourse, such as French in (4b), and probes that referred to an unmentioned item, such as Portuguese in (4c). Of course, it is likely that these two types of probes differ in their baseline attractiveness as lures: for instance, the unmentioned items are not seen during the study phase and are new to the discourse. The critical test of whether readers are encoding a salient alternative proposition, however, is whether correct rejections of each of the two types of false probes differ in how they are affected by prominence in the original discourse. We detail this logic below.

One hypothesis is that the primary effect of the font emphasis is to enhance encoding of the correct proposition (i.e., the British found the endangered monkey). Enhancing memory for the correct proposition might also help readers reject the lures by process of elimination (the phenomenon of recollection rejection; Brainerd, Reyna, & Estrada, 2006; Matzen, Taylor, & Benjamin, 2011), but it should not do so exclusively for particular types of probes. That is, superior memory for the true proposition should help reject both the alternative lure (French) and the unmentioned lure (Portuguese).

However, on the basis of results from prosody (Fraundorf et al., 2010), we hypothesized that the effect of font emphasis is rather to promote encoding of a set of one or more salient alternative propositions that did not come true (i.e., encoding that the French did not find the monkey). Remembering the French did not find the monkey should help readers reject the false alternative probe (French). This benefit could potentially come about both through helping readers reject the alternative probe itself and through affirming the correct probe by process of elimination (because the alternative can be ruled out). Crucially, however, knowing that the French did not find the monkey does not help determine whether it was the British or the Portuguese who found the monkey. Thus, the hypothesis that font emphasis leads readers to encode an alternative set predicts that emphasis will benefit correct rejections of alternative probes (French) but not correct rejections of unmentioned probes (Portuguese).

In Experiment 1, we tested whether this pattern, previously observed with contrastive (L+H*) pitch accents in spoken discourse (Fraundorf et al., 2010), could also be observed as a function of two types of font emphasis in written discourse: capital letters and italics.

Method

Participants

Twenty-four individuals participated in partial fulfillment of a course requirement. In this and all other experiments, participants were native English speakers at the University of Illinois.

Materials

Participants read 36 discourses, taken from Experiment 3 of Fraundorf et al. (2010). Each discourse began with a context passage such as (3a), repeated below, that established two pairs of alternatives, such as the pair British versus French and the pair Malaysia versus Indonesia. A subsequent continuation passage mentioned one item from each pair of alternatives, such as British and Indonesia in (7). Across the set of discourses, an equal number of continuations referred to the member of the pair that the context passage had mentioned first (e.g., British was mentioned before French in the context passage) as referred to the member of the pair that the contrast passage had mentioned second.

During participants’ initial reading of the discourse, some of the critical words in the continuation were displayed with font emphasis. Font emphasis was independently manipulated on each of the two critical words, so that, within a given passage, font emphasis could be on the first, the second, both, or neither of the critical words, resulting in the four conditions presented in (7) below. (We included the separate manipulation of two pairs per discourse for consistency with Fraundorf et al., 2010, but, as in their experiments, the properties of one pair of alternatives never had any effect on memory for the other pair of alternatives.)

(3a) Both the British and the French biologists had been searching Malaysia and Indonesia for the endangered monkeys.

-

(7a)

Finally, the British spotted one of the monkeys in Malaysia and planted a radio tag on it.

-

(7b)

Finally, the BRITISH spotted one of the monkeys in Malaysia and planted a radio tag on it.

-

(7c)

Finally, the British spotted one of the monkeys in MALAYSIA and planted a radio tag on it.

-

(7d)

Finally, the BRITISH spotted one of the monkeys in MALAYSIA and planted a radio tag on it.

The type of font emphasis used was manipulated between participants. For half of the participants, emphasized words were displayed in capital letters, and for the other half, emphasized words were in italics.

In the recognition memory test, each critical word was tested with a probe statement about what happened in the continuation passage. Three probes were constructed for each item by varying a single word in the probe statement. A correct probe, such as (4a) above, referred to the correct item and should be affirmed. An alternative probe, such as (4b), referred to the other member of the pair in the original discourse and should be rejected. An unmentioned probe, such as (4c), referred to an item from the same semantic category but that was never mentioned in the original discourse; these probes should also be rejected. Each participant saw only one of these three probes for each item.

Each probe referred to only one of the two pairs of alternatives from a particular discourse. For example, the probes in (4) query which scientists found the monkey but not where the monkey was found. This allowed each pair to be separately tested, resulting in a total of 72 test items. No font emphasis was ever used in the test probes.

The assignment of items to the probe type and to the emphasis conditions was counterbalanced across participants using a Latin Square design. This resulted in a 3 x 2 x 2 design: probe type (correct, contrast, or unmentioned) x presence of emphasis x emphasis type (capitals or italics), with the first two variables manipulated within participants and the lattermost manipulated between participants. An advantage of this design is that each critical word always appeared in the same syntactic and discourse context, regardless of font emphasis or the probe type with which it would eventually be tested. This eliminates any possibility that the effects of font emphasis are due to confounds with syntactic position or with the content of the rest of the discourse.

Lists of the discourses and probe questions used in Experiment 1 are available in the Appendices of Fraundorf et al. (2010).

Procedure

The experiment was performed on a computer running MATLAB and the Psychophysics Toolbox (Brainard, 1997; Pelli, 1997). Participants were instructed that they would read some stories for a subsequent memory test. The format of the memory test was not described in advance.

Participants first completed a study phase in which each story was presented one at a time in a random order. Stories were displayed on a computer monitor in white Arial text against a black background. In Experiment 1, the entire discourse was displayed on the screen at the same time. The context passage and continuation passage were viewed as a single paragraph. Participants took as long as needed to read the discourse, and then pressed the space bar to advance to the next discourse. There was a 1000 ms delay between stories. When participants had read 18 of the 36 stories, a message informed them that they were halfway done and invited them to take a break before continuing.

After reading the last story, participants proceeded immediately to the test phase. In the test phase, probe statements appeared on the screen one at a time in a re-randomized order. Participants indicated whether they thought each statement was true or false by pressing one of two keys on the keyboard. Participants were told that they should reject a statement if they thought that any part of it was false.

Results

Analytic strategy

Memory performance has sometimes been assessed using the proportion of accurate responses, sometimes with the goal of comparing accuracy between true statements to be affirmed and false statements to be rejected. However, neither affirmations of true probes or rejections of false probes provide a pure measure of a single behavioral process, as both reflect a combination of (a) discrimination in memory between true and false information and (b) an overall preference to respond true or false elicited by particular participants, items, or conditions (Donaldson, 1996; Freeman, Heathcote, Chalmers, & Hockley, 2010; Wright, Horry, & Skagerberg, 2008). That is, accuracy might vary between true and false probes simply due to participants’ overall preference to respond true or false or the tendency of particular discourses to elicit true or false statements, rather than participants’ ability to discriminate one probe type from another. To separate participants’ response bias from their actual sensitivity to which probes were true and which probes were false probes, we applied the theory of signal detection (Freeman et al., 2010; Green & Swets, 1996; Macmillan & Creelman, 2005; Wright et al., 2008), in which data are parameterized as the proportion of true responses. This framework allows a theoretical and empirical dissociation between response bias (the overall baseline rate of responding true) and sensitivity (an increased probability of responding true when the probe statement is actually true, also known as discrimination). Although our primary interest was in participants’ sensitivity to whether particular probes were true or false, we report results for both sensitivity and response bias to present a complete description of the data. (To preview, font emphasis affected sensitivity and not response bias.)

We then analyzed the data using mixed effect logit models (Baayen, Davidson, & Bates, 2008; Jaeger, 2008; see also Wright et al., 2008, for applications to recognition memory). In these models, the log odds (or logit) of responding true are modeled on a trial-by-trial basis. We adopted these models rather than ANOVAs for three reasons. The primary motivation is that one of the goals of Experiments 2 and 3 was to investigate whether participants’ online reading time predicted their later memory. Evaluating this hypothesis required an approach in which variation in reading time could be related to memory at the level of individual trials rather than an aggregation of all trials within a condition. Although it would be possible to divide reading time into a categorical variable for use in an ANOVA (e.g., with a median split), such dichotomization greatly reduces statistical power by discarding the variation within each category (Cohen, 1983). Mixed effect logit models provide an effective way to relate reading time to later memory because they model performance on individual items and can easily incorporate continuously varying predictors such as reading time. Although reading time was not measured in Experiment 1, we apply the same methodology to Experiment 1 for consistency and ease of comparison across experiments.

A secondary motivation for using mixed effects logit models is that in some conditions, the proportion of true responses was low. Treating such proportions as the dependent variable in an ANOVA would be inappropriate: proportions far from .5 are not normally distributed in that their mean and variance are related (Agresti, 2007, p. 9; Jaeger, 2008). By comparison, the logit has variance unrelated to its mean across the range of possible proportions (Jaeger, 2008).

Finally, as in many psycholinguistic studies, variability across both the sampled participants and sampled items was of interest (Clark, 1973), and mixed effect models allow both of these sources of variability to be incorporated into a single model (Baayen et al., 2008).

Model fitting and results

Mixed effect models can include both fixed effects, representing variables for which the particular levels are of interest, and random effects, variables with levels randomly sampled from a larger population. The random effects included the items (propositions being tested) and participants. The fixed effects tested in Experiment 1 were the probe type, presence of font emphasis in the original story, and emphasis type, as well as their interactions. The three probe types were analyzed using two planned comparisons implemented using a sum-coding system. The first planned comparison tested sensitivity in rejecting the unmentioned probes relative to the baseline (mean) rate of rejections; this comparison tests what confers a benefit in rejecting items that were never part of the discourse. The second comparison tested sensitivity in rejecting the alternative probes relative to the baseline rate of rejections; this comparison tests what confers a benefit in rejecting salient contrast items. As our primary theoretical interest was in how emphasis would benefit participants’ later ability to reject the different types of false statements, both of these planned comparisons were coded so that a positive value indicated more correct rejections (i.e., fewer erroneous true responses). The other predictors were simply mean-centered; doing so provides parameters corresponding to the main effects in an ANOVA analysis (i.e., collapsing across the levels of the other variables). All models were fit in the R Project for Statistical Computing using the lmer function of the lme4 package (Bates, Maechler, & Bolker, 2011).

In each discourse, there were two propositions tested, each of which could be independently analyzed. It was possible that memory regarding one proposition (e.g., whether the British or French scientists found the monkey) could be influenced by whether the key word related to the other proposition (whether the monkey was found in Malaysia or Indonesia) was emphasized. However, a preliminary analysis indicated that this variable had no effect, consistent with past data from young adults on font emphasis (e.g., Lorch et al., 1996) and on pitch accents (Fraundorf et al., 2010; but see Fraundorf, Watson, & Benjamin, 2012, for differing results in other populations, including older adults). Consequently, we collapsed across this variable for all subsequent analyses.

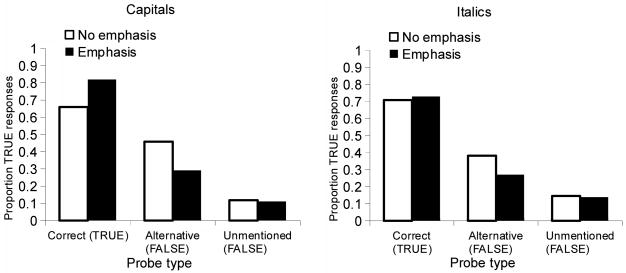

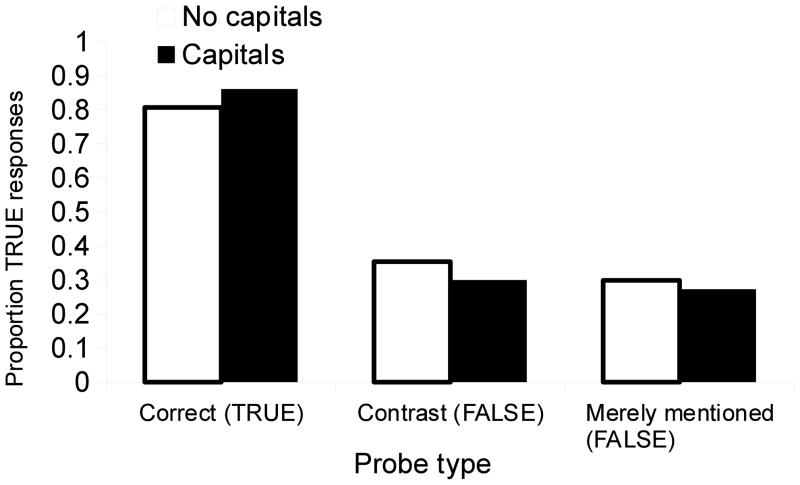

Proportion of true responses in each condition is displayed in Figure 1 as a function of probe type, presence of font emphasis in the original discourse, and emphasis type.

Figure 1.

Mean rate of true responses in Experiment 1 as a function of font emphasis and probe type, for participants who saw capitalization (top panel) and for participants who saw italicization (bottom panel). Responding true is a hit to a correct probe and a false alarm to an alternative or unmentioned probe.

In a mixed effect model, variability in an effect across participants or items can be represented with a random slope of that effect by participants or items. Random slopes by subjects for the two within-subjects factors (probe type and presence of font emphasis) did not improve the fit of the model, χ2(20) = 8.41, p = .99. Random slopes by items for the effects of font emphasis and probe type did improve the model, χ2(20) = 209.45, p < .001, but no random slopes for emphasis type (capitalization versus italicization) further improved the model (all ps > .9). Thus, we report results from the model with only random slopes by items for probe type, presence of emphasis, and their interaction, the maximal random effects structure justified by the data. (Estimates of the random effects from all three experiments are presented separately in Appendix E, as our primary theoretical interest was in the fixed effects.)

Fixed effect parameter estimates for the final model are displayed in Table 1. Overall, the odds of responding true rather than false were 0.59 (95% CI: [0.50, 0.70]), which reliably differed from chance, Wald z = −5.93, p < .001. This tendency to respond false is appropriate given that there were more false probes than true probes. The first planned comparison indicated that the odds of rejecting an unmentioned probe were 41.25 times (95% CI: [23.04, 73.78]) greater than participants’ baseline tendency to response false, z = 12.54, p < .001, indicating that participants were sensitive to the fact that the statements about the unmentioned probes were false. Collapsing across the presence of font emphasis, the odds of rejecting an alternative probe were 1.88 times (95% CI: [0.96, 3.69]) than participants’ baseline rejection rate (the second planned comparison), z = 1.85, p = .06, indicating only marginal sensitivity in memory. (However, as will be seen below, such rejections were substantially enhanced when the critical word was emphasized.)

Table 1.

Fixed Effect Estimates for Multi-Level Logit Model of Memory Judgments in Experiment 1 (N = 1728, Log-Likelihood: −811).

| Fixed effect | β | SE | Wald z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline rate of true responses (response bias) | −0.53 | 0.09 | −5.93 | <.001 |

| Emphasized word (effect on response bias) | −0.07 | 0.14 | −0.44 | .55 |

| Rejections of unmentioned probe vs. baseline (sensitivity) | 3.72 | 0.30 | 12.54 | <.001 |

| Rejections of alternative probe vs. baseline (sensitivity) | 0.63 | 0.34 | 1.85 | .06 |

| Capitalization vs. italics (effect on response bias) | 0.08 | 0.14 | 0.60 | .55 |

| Emphasized word x capitalization (effect on response bias) | 0.26 | 0.27 | 0.96 | .34 |

| Emphasized word x rejection of unmentioned probe (effect on sensitivity) | 0.62 | 0.53 | 1.17 | .24 |

| Emphasized word x rejection of alternative probe (effect on sensitivity) | 1.31 | 0.46 | 2.86 | <.01 |

| Capitalization x rejection of unmentioned probes (effect on sensitivity) | 0.75 | 0.42 | 1.80 | .07 |

| Capitalization x rejection of alternatives (effect on sensitivity) | −0.44 | 0.36 | −1.23 | .22 |

| Emphasized word x capitalization x rejection of unmentioned probes (effect on discrimination) | 0.62 | 0.83 | 0.74 | .45 |

| Emphasized word x capitalization x rejection of alternative probes (effect on discrimination) | 1.22 | 0.72 | 1.70 | .09 |

Note. SE = standard error.

The crucial question was how responding would be affected by the font emphasis in the original discourse. Font emphasis did not induce an overall bias to respond true, z = −.53, p = .60. Rather, it facilitated rejection of the alternative probes; the odds ratio between rejections of an alternative probe and the overall rejection rate (contrast 2) were 3.70 times (95% CI: [1.51, 9.08]) greater when the critical word was originally emphasized, z = 2.85, p < .01. However, font emphasis did not reliably benefit rejections of the unmentioned probes, z = 1.17, p = .24.

Finally, there was a marginal 3-way interaction of probe type, presence of font emphasis, and emphasis type, indicating that the benefit of emphasis in rejecting the alternative probes was stronger for capital letters than italicization, with the effect being 3.39 times (95% CI: [0.83, 13.81]) greater for participants who saw capitals rather than italics, z = 1.70, p = .09.

Discussion

Experiment 1 demonstrated a mnemonic benefit of representing salient alternatives similar to that observed by Fraundorf et al. (2010). Placing font emphasis on one member of a pair of alternatives during the original presentation of a discourse improved participants’ ability to reject an alternative proposition to the emphasized item on a subsequent memory test. However, font emphasis conferred no benefit in rejecting propositions about items that were never part of the discourse. This pattern suggests that the font emphasis led participants to encode a particular alternative to the true proposition, which would help reject that alternative but not items that were never in the alternative set. This result demonstrates that memory for a discourse can involve remembering not only what happened, but also important alternatives that did not happen.

Experiment 1 extended these prior results by demonstrating the effect is not limited to cases where participants hear contrastive (L+H*) pitch accents in spoken discourse. A similar benefit can also be observed in a different modality—written text—and with a different manipulation—font emphasis rather than pitch accents. This result is consistent with proposals that implicit prosody is generated in the process of silent reading (Breen & Clifton, 2010; Fodor, 1998), as well as with accounts in which any sufficiently prominent material brings to mind relevant alternatives (e.g., Calhoun, 2009).

Importantly, the pattern across conditions indicates that these mnemonic benefits cannot be attributed only to the perceptual properties of font emphasis. If memory for the discourse was improved simply because the emphasized words were perceptually salient or easier to read, this should have applied to any probe that tested memory for the information. However, the effect was more specific: emphasized text did not benefit rejections of a probe that referred to an item never in the discourse, suggesting the memory benefit lay in the encoding of an alternative set. Nevertheless, it is likely that the perceptual salience of emphasized text plays a role in its effects, and we return to this point in the Discussion.

The findings of Experiment 1 are qualified by the somewhat high rate of rejections of the unmentioned probes even in the absence of font emphasis (M = 13% affirmed, thus 87% rejected), which may have masked any potential benefit of font emphasis in rejecting them. In Experiment 3, we provide stronger evidence for representation of the salient alternatives by introducing a new type of false probe. The new false probe elicits a substantially higher rate of false alarms, but it still does not mention the alternative and still shows no effect of font emphasis.

Both capital letters and italicization promoted encoding of an alternative set in memory; in fact, the effect was stronger for capitalization. This conflicts with the finding that italicization is more apt to be described as having have a contrastive interpretation when participants are simply asked to describe the “meaning” of different kinds of font emphasis (McAteer, 1992). However, those metalinguistic judgments may not tap the same processes as reading and memory. Other evidence in fact suggests that metalinguistic judgments do not always predict the actual benefits of font emphasis: for instance, colored text is rated as more salient than capitalization, but capitalization is actually more effective at increasing memory for drug names (Filik et al., 2006). And, more generally, learners often incorrectly appraise which study conditions will lead to superior memory (for review, see Benjamin, 2005, 2008; Kornell & Bjork, 2007).

Experiment 1 thus provided evidence that in reading, as in spoken discourse comprehension, prominence of one element of the discourse leads comprehenders to encode a salient alternative proposition, formed by substituting the prominent element for a different element of the discourse, and that this representation benefits later memory. However, Experiment 1 did not reveal anything about how participants’ initial, online processing of the discourse may have contributed to this memory benefit. In Experiment 2, we assessed participants’ online reading time and how it did or did not relate to participants’ later memory.

Experiment 2

Experiment 2 measured participants’ online reading time while they read discourses containing two-item pairs similar to those in Experiment 1. Of particular interest was whether the memory benefit from the font emphasis was contingent on how participants originally read the emphasized words. One hypothesis is that it may be time-consuming to calculate and encode the set of alternatives and that, as a result, readers do not always spend the time to do so (or do not do so to a degree that the alternatives can be remembered later). This hypothesis predicts that reading time on the emphasized word will be causally related to memory, with increased reading time predicting a greater likelihood of observing the memory benefit. By contrast, two other hypotheses do not predict a relationship between reading time and later memory. One such hypothesis is that fixing the set of alternatives requires no extra time. The other is that calculating the set of alternatives requires extra time, but that readers do so every time they encounter font emphasis. If readers always slow down to calculate the alternatives, reading time would not discriminate those trials on which the alternative set was encoded from those trials on which it was not. Thus, under either of these latter accounts, trial-by-trial variability in reading time would not predict later memory for the alternative. Experiment 2 pits these hypotheses against the hypothesis that readers only sometimes invest the time to calculate the alternative set.

Experiment 2 also provided a further test of the generality of the memory benefits by using different discourses than Experiment 1.

Method

Participants

Forty-eight individuals participated in partial fulfillment of a course requirement or for a cash honorarium. One of the original 48 participants did not complete the entire procedure within the 50 minutes allotted for the session and was replaced with an additional participant.

Materials

The Experiment 1 materials were substantially rewritten for Experiment 2 in order to add additional controls. First, readers are known to slow down at the ends of punctuation-marked sentences and clauses (for review, see Reichle, Warren, & McConnell, 2009), and this slowdown could overwhelm the effects of interest. To avoid this, the critical words in the continuation passage never appeared immediately before or after a punctuation mark between clauses.

Second, reading times increase at the start of a line and decrease at the end (for review, see Rayner, 1998). To ensure this effect did not vary across items, the discourses were written so that when the discourses were naturally spaced on the computer screen, the critical words never appeared first or last in a line.

Third, the two words in each pair (e.g., Jupiter and Neptune) were matched in number of characters. Readers are known to acquire information about the length of upcoming words before fixating them (for review, Rayner, 1998); matching the length of the two words in the pair prevented readers from obtaining information about the outcome of the discourse before actually reading the critical word itself. Because the unmentioned probe was not read in the original discourse, it was not necessary to control its length, but where possible, the unmentioned probe was also matched in character length to the other two probes as well.

Finally, in four discourses in Experiment 1, the referent that would be expected to be included in the alternative proposition was never mentioned explicitly and had to be pragmatically inferred. For example, in one discourse, boys was implicitly contrasted with girls without girls being mentioned in the context passage. Although some lexical items may inherently evoke relevant contrasts (Clifton, Bock, & Radó, 2000) that could become part of the alternative set (Pierrehumbert & Hirschberg, 1990; Rooth, 1992; Steedman, 2000), determining these alternatives may be more time-consuming for readers than when the alternative was explicitly introduced (Sedivy, 2002). Thus, variability in whether a salient alternative was explicitly introduced would likely introduce additional variability in reading time between items. In Experiment 2, the salient alternative item was always explicitly mentioned in the context passage, using the same lexical item that would appear in the continuation.

In all other respects, the items used in Experiment 2 had the same structure as those in Experiment 1. Probe type, presence of font emphasis, and emphasis type were manipulated using the same design as in Experiment 1.

A list of the Experiment 2 discourses appears in Appendix A and the test probes in Appendix B.

Procedure

In the study phase of Experiment 2, discourses were presented using the self-paced moving window paradigm (Just, Carpenter, & Woolley, 1982). The discourse was initially displayed on the screen with only the first word visible; the other words were replaced by lines. Participants pressed the space bar to advance through the discourses; after each press, the next word was displayed and the previous word replaced by a line. As in Experiment 1, the context passage and continuation passage were combined into a single paragraph.

In the moving window paradigm, text is most commonly presented in fixed-width faces such as Courier, in which every character occupies the same width on the screen. However, pilot testing suggested that participants found it difficult to detect italicization of the Courier face. We instead presented text in Arial, a face in which letters vary in their width. Words outside the moving window were replaced with lines exactly matched in length to the width on the screen that the words would occupy when presented in Arial.

To demonstrate that words in the experiment could be emphasized with font manipulations, one word in the initial instructions to participants was emphasized using the type of font emphasis (capitalization or italicization) that participants would later see in the experiment.

The recognition test procedure was unchanged between experiments.

Results

Due to an error in stimulus construction, for one memory probe the words used in the three probe conditions did not match the referents named in the original discourse. We report results with data from this item omitted, but the inclusion or omission of this item did not affect any of the patterns described below.

Initial reading time

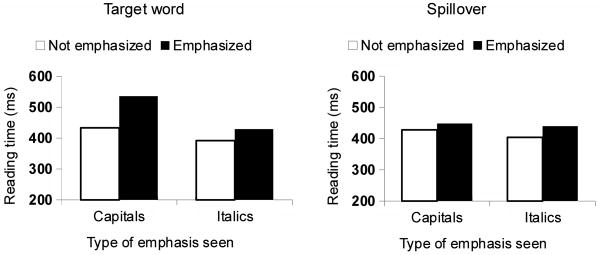

The characteristics of word n can also affect reading time to the following word n+1 (Henderson & Ferreira, 1990; Rayner, 1998), so we examined reading times both on each critical word and on the spillover word that immediately followed. Mean reading times for each region and condition during the original presentation of the discourse are displayed in Figure 2. Because the reading times were positively skewed (skewness = 7.09) and thus non-normal, we used the natural log of the reading times (skewness = 0.92) as the dependent variable in our models.

Figure 2.

Mean reading time in Experiment 2 on target words (left panel) and spillover words (right panel) as a function of font emphasis and emphasis type.

The model of reading time included random effects of participants and of items (words), as well as three fixed effects: region (critical word or spillover), presence of font emphasis (present or absent), and emphasis type (capitalization or italics), resulting in a 2 x 2 x 2 design. Region and presence of font emphasis were coded using dummy coding. This coding system first tests the simple main effects of font emphasis within just the reference level (the critical word). Then, the interaction of other effects with the region variable tests whether those effects differed on the spillover word as compared to the critical word. Emphasis type (capitalization or italics) was mean-centered so that the main effects of region and font emphasis represent the mean of those effects across emphasis types. An interaction with emphasis type represents a stronger or weaker effect for one emphasis type relative to the other.

Random slopes for the two within-participants factors significantly improved the fit of the model, χ2(9) = 63.86, p < .001, indicating some variability across participants in how much their reading times were affected by font emphasis. Random slopes by items for those same two factors further improved the fit of the model, χ2(9) = 32.24, p < .001. The addition of random slopes by items of emphasis type (capitals or italics) and its interactions with the other factors did not improve the fit of the model any further, χ2(26) = 29.19, p = .30.

Fixed effect parameter estimates from the final model are displayed in Table 2. First, consider the initial four parameters. These parameters test the simple main effects of font emphasis within the critical word itself4. The model revealed that, overall, emphasized words (M = 462 ms) were read more slowly than words without font emphasis (M = 414 ms), t = 5.52, p < .001. There was also an interaction with emphasis type: font emphasis increased reading times more for participants who saw capital letters rather than italics5, t = 2.51, p < .05.

Table 2.

Fixed Effect Estimates for Multi-Level Model of Log Reading Time in Experiment 2 (N = 6816, Log-Likelihood: −2710).

| Fixed effect | β | SE | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-emphasized critical word (baseline) | 5.90 | 0.04 | 138.37 | <.001 |

| Emphasized word | 0.10 | 0.02 | 5.52 | <.001 |

| Emphasis type is capitalization (vs. italics) | 0.06 | 0.08 | 0.66 | .51 |

| Emphasized word x emphasis type is capitalization | 0.09 | 0.04 | 2.54 | < .05 |

| Spillover region | 0.02 | 0.01 | 1.41 | .16 |

| Spillover region x emphasized word | −0.03 | 0.02 | −1.48 | .14 |

| Spillover region x emphasis type is capitalization | > −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.25 | .80 |

| Spillover region x emphasized word x capitalization | −0.10 | 0.04 | −2.44 | <.05 |

Note. SE = standard error.

The remaining parameters test whether the effects in the spillover region differ significantly from those in the critical region itself. There was a reliable three-way interaction of region type, font emphasis, and emphasis type, with the difference between capitalization and italicization disappearing by the spillover region, t = −2.48, p < .05.

Memory

One goal of Experiment 2 was to assess whether the benefit of font emphasis on discriminating the true proposition from the salient alternative proposition varied as a function of participants’ online reading time. That is, was a combination of both font emphasis and increased reading time needed to obtain a mnemonic benefit? To test this hypothesis, we analyzed participants’ memory performance using the same approach as in Experiment 1, but we added parameters for participants’ initial reading time and its interactions with the other variables of interest.

One concern with using raw reading time as a predictor is that it confounds slowdown on the emphasized words with participant-level variation in reading speed. For instance, participants who were more motivated to remember the discourses may have both read more slowly and been more apt to calculate an alternative set. This could lead to an association of reading time with memory performance even if there were no causal relation between increased reading time and calculation of the focus semantic value.

A solution is to examine only within-subject differences in reading time. We calculated residual reading time (Ferreira & Clifton, 1986) by regressing, separately for each participant, reading time on (a) an intercept representing baseline reading speed and (b) the length6 of each word. Residual reading time is the reading time left unexplained by these more basic factors. To obtain the most precise estimate of participants’ reading speed, the regression models for calculating residual reading time included all words in the materials, not just the critical regions. Although residual reading time has typically been calculated from untransformed reading times, reading times, as noted above, are positively skewed, so we instead modeled log-transformed reading time.

We then analyzed the log odds of true responses as a function of probe type, presence of font emphasis, and emphasis type, as well as residual reading time. Residual reading time was summed over the critical and spillover words. One percent of the observations contained residual reading times more than three standard deviations from a participant’s mean in that condition. These outlying observations might reflect extraneous influences irrelevant to the task, such as sound from outside the experiment or a participant sneezing. Mixed effects models are robust against missing data (Quené & van den Bergh, 2004), so rather than make potentially erroneous assumptions about what outlying reading times should be replaced with, we simply eliminated these observations, affecting 1% of the data. The predictor variables were again coded using mean centering to obtain estimates of the main effects. Reading time was also mean-centered; consequently, the main effects of other variables represent effects of those variables at an average residual reading time for the critical region.

Fixed effect parameter estimates from the model are displayed in Table 3. A preliminary analysis indicated that, once reading time during the study phase was accounted for, emphasis type (capitals or italics) made no further contribution to the model, χ2(12) = 10.30, p = .59, so we dropped this variable to simplify the model. However, the model was improved by the inclusion of random slopes for probe type by participants, χ2(5) = 23.76, p < .001, and by items, χ2(5) = 424.25, p < .001. No other random slopes approached significance (all ps > .25).

Table 3.

Fixed Effect Estimates for Multi-Level Logit Model of Memory Judgments in Experiment 2 (N = 3368, Log-likelihood = −1687).

| Fixed effect | β | SE | Wald z | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline rate of true responses (response bias) | −0.33 | 0.11 | −2.92 | <.01 |

| Rejections of unmentioned probe vs. baseline (sensitivity) | 3.32 | 0.25 | 13.20 | <.001 |

| Rejections of alternative vs. baseline (sensitivity) | −0.11 | 0.31 | −0.37 | .71 |

| Emphasized word (effect on response bias) | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.32 | .75 |

| Reading time (effect on response bias) | 0.19 | 0.09 | 2.09 | .04 |

| Emphasized word x reading time (effect on response bias) | 0.04 | 0.18 | 0.22 | .83 |

| Emphasized x rejections of unmentioned probe (effect on sensitivity) | −0.14 | 0.27 | −0.53 | .60 |

| Emphasized x rejections of alternative probe (effect on sensitivity) | 0.49 | 0.25 | 1.97 | <.05 |

| Reading time x rejections of unmentioned probe (effect on sensitivity) | −0.27 | 0.27 | −0.99 | .32 |

| Reading time x rejections of alternative probe (effect on sensitivity) | −0.12 | 0.24 | −0.48 | .63 |

| Emphasized x reading time x rejections of unmentioned probe (effect on sensitivity) | −0.27 | 0.54 | −0.49 | .62 |

| Emphasized x reading time x rejections of. alternative probe (effect on sensitivity) | 0.99 | 0.48 | 2.05 | <.05 |

Note. SE = standard error.

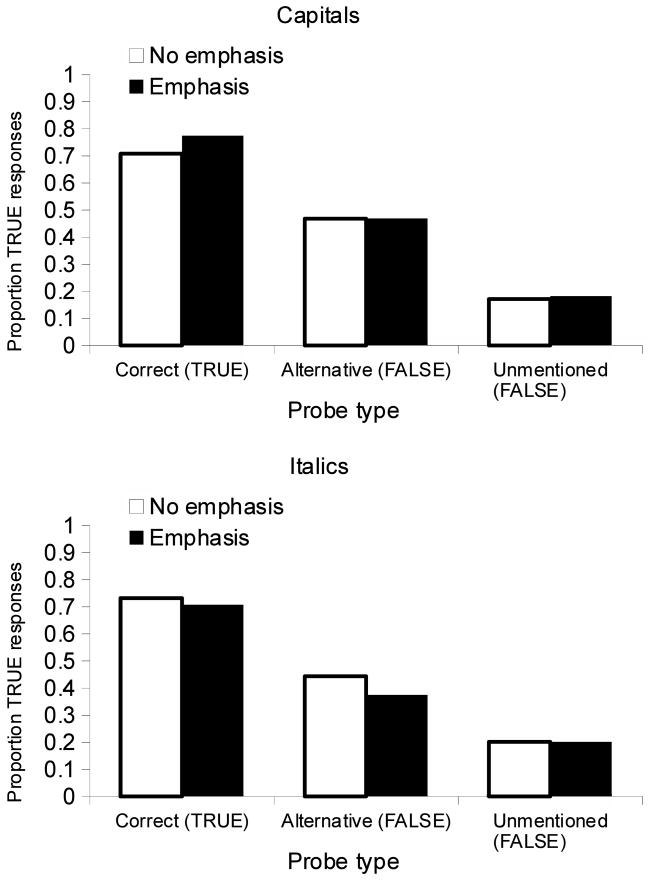

Mean rates of true responses in each condition are displayed in Figure 3. The memory effects observed in Experiment 1 were replicated. At a mean level of residual reading time, font emphasis improved readers’ rejection of the alternative probes: the presence of font emphasis increased the odds ratio of rejections of the alternative probes over the baseline response bias (the second planned comparison) by 1.63 times (95% CI: [1.01, 2.64]), z = 1.97, p < .05. By comparison, font emphasis did not benefit rejections of the unmentioned probes (the first planned comparison), z = −0.53, p = .60. In fact, the effect was numerically in the opposite direction, with font emphasis decreasing the odds of this rejection by 0.87 times (95% CI: [0.49, 1.63]).

Figure 3.

Mean rate of true responses in Experiment 2 as a function of font emphasis and probe type, for participants who saw capitalization (top panel) and for participants who saw italicization (bottom panel). Responding true is a hit to a correct probe and a false alarm to an alternative or unmentioned probe.

Additionally, Experiment 2 found that the benefit of font emphasis in rejecting the alternative probes was amplified by increased reading time. The model revealed a three-way interaction between font emphasis, probe type, and reading time. An increase of 1 log millisecond7 of reading time on emphasized material corresponded to a 2.69 times increase in the odds ratio between rejections of alternative probes and the baseline rejection rate (95% CI: [1.04, 6.91]), z = 2.05, p < .05. That is, the more that readers slowed down on the emphasized words, the more likely font emphasis was to improve rejections of the alternative probes.

Again, this effect was limited to rejecting the salient alternative proposition, not all false statements. A 1-unit increase in residual reading time on emphasized material actually resulted in a numerical decrease in the odds of rejecting the unmentioned probe by 0.77 times (95% CI: [0.27, 2.20]), although this effect was not statistically reliable, z = −0.49, p = .62. The two-way interaction between reading time and rejecting the alternative probe, collapsing across the presence of emphasis, was also not significant, z = −0.48, p = .63. That is, increased reading time was not generally predictive of improved rejection of alternative probes. (In fact, the relation was numerically in the opposite direction.) Increased reading time only improved memory when it was spent on emphasized words.

There was one effect on response bias: the odds of a true response were 1.21 times greater (95% CI: [0.98, 1.38]) for every 1-unit increase in residual reading time, regardless of whether a particular probe was true or false, z = 2.09, p < .05. It is not clear what would account for this effect and it was not replicated in Experiment 3.

Discussion

Experiment 2 replicated the effects of font emphasis on memory observed in Experiment 1. Emphasizing one member of a pair using a font change enhanced participants’ later ability to reject a proposition referring to the other, alternative member of the pair. But, it did not help reject propositions about items that were unmentioned, which were unlikely to be part of the alternative set. Experiment 2 generalized this pattern to new discourses different from the ones used in the original Fraundorf et al. (2010) study.

Experiment 2 extended the first experiment by collecting a measure of online reading time. Words emphasized with capital letters or italics were read more slowly than non-emphasized words. Moreover, the degree to which reading was slowed predicted the extent to which font emphasis helped reject the alternative probes on the later memory test. This relationship was observed even in a measure of residual reading time that removes any confound with participant-level differences in baseline reading speed. Moreover, the words and syntactic structures used in each discourse were invariant. Thus, the relation of reading time to later memory cannot be attributed to differences in lexical or syntactic variables that might affect reading time, such as word frequency, imageability, or syntactic position. Rather, this pattern might suggest that it is time-consuming to calculate an alternative set in response to emphasized words: the degree to which readers spent extra time on the emphasized words predicted the extent to later memory showed a benefit of encoding the alternative set.

Experiment 2 also clarified the difference between the two types of font emphasis tested in the present study: capitalization and italics. In Experiment 1, capital letters were observed to have a stronger mnemonic benefit than italics. In Experiment 2, capitalization also led to greater increases in online reading time; however, once these differences in initial reading time were controlled for, the two types of font emphasis did not differ in their effects on memory. That is, the difference between capitalization and italicization in their effects on memory appears to stem from how strongly they affected initial reading time.

The experiments thus far provide evidence that font emphasis can prompt readers to encode an alternative set, helping them to later reject certain salient alternative propositions. However, it is unclear exactly which alternative propositions are encoded in this set. One hypothesis is that the set of alternatives includes propositions about any item in the discourse of the same semantic or syntactic category—as might be expected if its contents are strongly influenced by generic or taxonomic knowledge. Another hypothesis is that the situation model tightly circumscribes the alternative set, as it does the set of items considered in resolving a referring noun phrase (e.g., Brown-Schmidt & Tanenhaus, 2008; Nieuwland et al., 2007). Under this latter hypothesis, comprehenders encode as alternatives only those propositions that are plausible or likely given the scenario described in the discourse. Either of these hypotheses could explain the results of Experiments 1 and 2: the alternative probes were both mentioned and good alternatives for the true proposition whereas the unmentioned probes involved items that were neither salient alternatives nor mentioned in the discourse at all. We conducted Experiment 3 to tease apart these hypotheses.

Experiment 3

In Experiment 3, we tested whether font emphasis would help reject propositions about items that were mentioned in the discourse but that were unlikely alternatives in a situation model. For example, consider context passage (6a), reproduced below8. Both Saturn and Neptune are mentioned exactly once in the discourse. But, they differ in their relationship to Jupiter in the continuation (6b). As in prior experiments, Saturn is mentioned as part of the same pair as Jupiter and is a plausible alternative for Jupiter in the continuation. (That is, the photos of Saturn could have been lost instead.) However, Neptune is a poor alternative for Jupiter in the situation model in (6b) because the discourse establishes that the mission to Neptune has not yet occurred.

-

(6a)

Originally, the space probe Cosmo III was designed to fly past Jupiter and Saturn and send photos and measurements back to NASA from both planets. NASA needed this information to guide the videos they were going to take of Neptune on a future mission.

-

(6b)

However, due to a glitch in the programming of the Cosmo III, it lost the photos taken of Jupiter and put the future mission in trouble.

Consequently, memory probes (8a) and (8b), although both false and both mentioning prior discourse entities, could be differentially affected by font emphasis. Probe (8a) represents the alternative probe condition, the same as in prior experiments, whereas probe (8b) involves an item that, while mentioned in the discourse, is a poor alternative in the situation model for the true proposition. We term this new probe condition the merely mentioned probe. If prominence leads comprehenders to encode only those alternative propositions that are plausible in a situation model, then font emphasis should help discriminate the correct probe only from the alternative probe and not from the merely mentioned probe. However, if the alternative set includes propositions involving any referent in the discourse of the same semantic category, then font emphasis should help discriminate the truth from both probe types.

-

(8a)

NASA lost some of the data from Saturn due to a glitch in the space probe.

-

(8b)

NASA lost some of the data from Neptune due to a glitch in the space probe.

Experiment 3 also eliminated the confound between probe conditions and lexical properties. In Experiments 1 and 2, the alternative and unmentioned probe conditions contained different lexical items. For example, for one discourse, the unmentioned probe was always Portuguese, while the alternative was British or French. It is possible that the sets of lexical items used in alternative probes versus unmentioned probes coincidentally differed in some property, such as lexical frequency, imageability, or general semantic plausibility, and that the differences between probe types were actually driven by these lexical differences rather than their relevance as an alternative to the true proposition. In Experiment 3, the same lexical items were rotated through the alternative and merely mentioned probe conditions across lists, thus controlling for any lexical properties that might have influenced the effect of prominence.

As in Experiment 2, we collected measures of reading time in Experiment 3 to further test whether variability in the influence of font emphasis on memory was related to whether readers invested additional time in processing the emphasized words.

Method

Participants

Forty-eight new participants completed Experiment 3.

Materials

Thirty-six discourses were constructed for Experiment 3. The discourses took the same general format as those used in previous experiments. In Experiment 3, however, each context passage introduced not only two pairs of items, but also one additional item related to each pair. This third item was from the same semantic domain, but the discourse established that it was not participating in an event, had occurred or would occur at a different time, or had already been ruled out by a decision-maker, thus making it an unlikely alternative in the situation model for the item mention in the continuation passage. The alternative and the merely mentioned item were each mentioned exactly once in the discourse. For example, in example (6) above, the context passage establishes the pair Jupiter and Saturn; Neptune is also mentioned, but in a context that establishes it is not part of the mission described in the discourse. The same applies for the pair photos and measurements versus the merely mentioned item video.

As in Experiment 2, the target words in the continuation never appeared at the beginning or end of a line of text on the screen and never at the beginning or end of a punctuation-marked clause. Also as in prior experiments, an equal number of continuations referred to the member of the pair that the context passage had mentioned first as had been mentioned second.

The correct probe and the alternative probes for the recognition memory test were constructed as in previous experiments. The unmentioned probes were replaced by the merely mentioned probes, which referred to the item that the discourse had established as an unlikely alternative to the true proposition (e.g., Neptune in the above example).

In Experiment 3, the lexical items used for the alternative and merely mentioned probes were rotated across lists. That is, one participant would see the pair Jupiter and Saturn with Neptune as the merely mentioned item, while another participant would see Jupiter and Neptune with Saturn as the merely mentioned item. As our primary interest was in the two types of false probes from which the correct information needed to be discriminated, the true proposition itself was consistent across lists.

The rotation of lexical items across lists introduced additional counterbalancing variables. To avoid a proliferation of experimental lists, we did not manipulate the type of font emphasis used in Experiment 3. For all participants, emphasized words were emphasized with capital letters. Prior experiments had observed qualitatively similar patterns across emphasis types, especially when initial reading time was taken into account.

The Experiment 3 discourses appear in Appendix C and the test probes in Appendix D.

Procedure

Aside from the change in materials, the procedure of Experiment 3 was identical to that of Experiment 2.

Results

Initial reading time

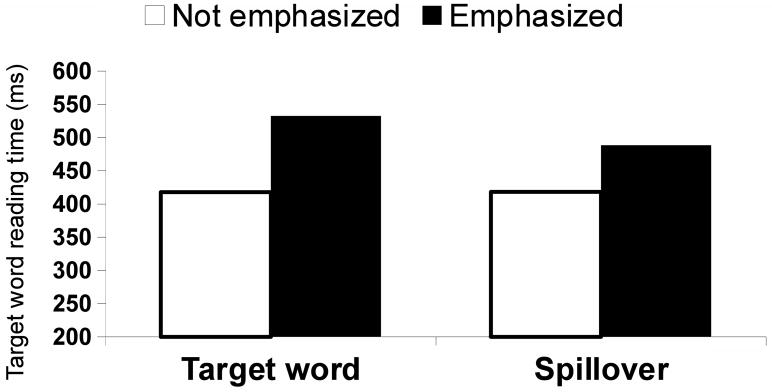

Reading times during the initial presentation of the discourse in Experiment 3 are displayed in Figure 4 as a function of region and presence of font emphasis. We analyzed the reading times on the critical word and spillover region as in Experiment 2; as before, reading times were highly skewed (skewness = 11.16), so we used the natural log of the reading times (skewness = 0.93).

Figure 4.

Mean reading time in Experiment 3 on target words and spillover words as a function of font emphasis.

Random slopes by subjects for the two factors significantly improved the fit of the model, χ2(9) = 239.02, p < .001, as did the same slopes by items, χ2(9) = 83.67, p < .001. Fixed effect parameter estimates from the full model are displayed in Table 4. Again, words with font emphasis (M = 510 ms) were read more slowly than the same words without emphasis (M = 417 ms), t = 5.47, p < .001. Reading times did not significantly differ between the critical and spillover words, nor did the effect of font emphasis reliably vary across these regions.

Table 4.

Fixed Effect Estimates for Multi-Level Model of Log Reading Time in Experiment 3 (N = 6912, Log-Likelihood: −3281).

| Fixed effect | β | SE | t | p |