Abstract

Cerium oxide nanoparticles or nanoceria are emerging as a new and promising class of nanoparticle technology for biomedical applications. The safe implementation of these particles in clinical applications requires evaluation of their redox properties and reactivity that might cause neurotoxic effects by interacting with redox components of the physiological environment. We report in vitro and in vivo studies to evaluate the impact of nanoceria exposure on serotonin (5-HT), an important neurotransmitter that plays a critical role in various physiological processes including motility and secretion in the digestive system. In vitro studies of 5-HT in the presence of nanoceria using spectroscopic, electrochemical and surface characterization methods demonstrate that nanoceria interacts with 5-HT and forms a surface adsorbed 5-HT-nanoceria complex. Further in vivo studies in live zebrafish embryos indicate depletion of the 5-HT level in the intestine for exposure periods longer than three days. Intestinal 5-HT was assessed quantitatively in live embryos using implantable carbon fiber microelectrodes and the results were compared to immunohistochemistry of the dissected intestine. 20 and 50 ppm nanoparticle exposure decreased the 5-HT level to 20.5 (±1.3) and 5.3 (±1.5) nM respectively as compared to 30.8 (±3.4) nM for unexposed control embryos. The results suggest that internalized nanoceria particles can concentrate 5-HT at the nanoparticle accumulation site depleting it from the surrounding tissue. This finding might have long term implications in the neurophysiology and functional development of organisms exposed to these particles through intended or unintended exposure.

Keywords: nanoceria, serotonin, neurotoxicity, nanotoxicity, zebrafish embryos, intestine, implantable microelectrodes

1. Introduction

Progress in nanomaterial research over the last decade offers exciting opportunities for many beneficial uses of engineered nanoparticles and nanostructures in sensing, diagnosis and therapeutic applications 1, 2. With the increased use of these materials in the biomedical field there are raising safety concerns associated with their potential to induce cytotoxicity and alter biological functions in living systems 3, 4. While numerous studies have been conducted to evaluate nanoparticle toxicity through assessment of viability and developmental malformations5 little is known about their effects on components of the neurological system6–9. How nanoparticles interact with chemical neurotransmitter compounds and their potential to induce neurotoxic effects in biological systems has not been adequately investigated.

Cerium oxide nanoparticles (CeO2) or nanoceria have found many interesting applications in biomedicine as potential therapeutic agents in the treatment of oxidative stress related diseases10, 11. Small sized nanoceria particles have been shown to cross the blood brain barier and inactivate free radicals12. Rat neuron cells treated with nanoceria have showed increased lifespan and protection against cell injury induced by hydrogen peroxide or UV light 13. In another study, nanoceria has been shown to protect primary cells from the detrimental effects of radiation therapy14. Similarly, nanoceria has prevented retinal degeneration induced by intracellular peroxidase15 and provided neuroprotection to spinal cord neurons16. Such useful properties are a consequence of the redox activity and dual oxidation state of Ce3+/Ce4+ onto the nanoparticle surface17 that enables them to promote catalytic processes and act as enzyme mimetics18, 19. Given the surface oxidation state there is potential for these particles to participate in redox reactions with other redox species that are commonly present in living systems. However, with the exception of hydrogen peroxide, very little is known about the interaction of ceria nanoparticles with redox components of the physiological environment. Among compounds that are susceptible to oxidation by nanoceria are monoamine neurotransmitters such as dopamine, serotonin and noradrenaline. Interaction of these particles with neurotransmitters might change the oxidation metabolism of monoamines20, decrease their physiological levels or generate toxic metabolites with neurotoxic potential which could result in damage to the neural system function and induce neurological disorders.

Here we assess the effect of nanoceria on serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT) by first studying chemical reactivity of these particles in the presence of 5-HT in vitro, and then in vivo, by measuring intestinal 5-HT levels after nanoceria exposure to whole zebrafish embryos. Zebrafish offers unique advantages, including rapid embryonic development (120 hrs), generation of large number of embryos and optical transparency allowing for easy visual examination of organs. They share similar genetic information to humans and have a full complement of organ systems that are similar in structure and physiology to other vertebrate systems21–23. Zebrafish is an excellent vertebrate model system to identify nanoparticles with toxic effects and the route of exposure. As with other nanoparticles, nanoceria will first interact with surfaces exposed to the external environment including the skin, gills, and intestine in aquatic vertebrates. Of these organs, nanoparticles are likely to accumulate at higher concentrations within the digestive system due to ingestion and retention within the lumen. 5-HT is secreted at high concentrations within the digestive system (95% of the total 5-HT content in the body) by enterochromaffin cells (EC)24–26. Accumulation of nanoceria within the intestinal lumen may result in alteration of 5HT concentration, which in turn may affect the normal functioning of the digestive system. For example, a decrease in mucosal 5-HT 27 and an increase in enterochromaffin cells 28, 29 are associated with celiac disease. Irritable bowel syndrome leads to change in 5-HT level and decreases serotonin transporter expression affecting transit time and secretion within the intestine 30, 31.

Our in vitro results demonstrate strong interaction between nanoceria and 5-HT with formation of a 5-HT-nanoceria complex, indicating possible effects of nanoceria on oxidative pathways of the 5-HT neurotransmission. The in vivo results show depleted intestinal 5-HT levels after exposure of the embryonic zebrafish to these particles. 5-HT was determined using implantable microelectrodes which allow quantitative measurements with high sensitivity and selectivity21, 22. The results of this study have important implications in understanding and predicting the neurotoxic effect of nanoparticles on the neurophysiology of living organisms.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Reagents

CeO2 (99.9%, 10–30 nm) nanoparticles were purchased from SkySpring Nanomaterials Inc. (Houston, TX). Serotonin hydrochloride (99%) was obtained from Acros Organics. Potassium phosphate (monobasic), chitosan (from shrimp shells; practical grade) and 2-propanol (99.5% ACS grade) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium phosphate (dibasic), sodium chloride, potassium chloride, magnesium sulfate, and calcium chloride dihydrate were obtained from Fisher Scientific. Acetic acid (glacial) was purchased from J.T. Baker. Methanol (100%) was from LabChem Inc (Pittsburgh, PA).

2.2. CeO2 nanoparticle dispersions in E3 (egg water)

CeO2 nanoparticles in powder form were dispersed in E3 medium. E3 solution (pH 6.9 – 7.2) contains 5 mM NaCl, 0.17 mM KCl, 0.33 mM MgSO4 and 0.33 mM CaCl2 in distilled, deionized water (Millipore, Direct-Q System) with a resistivity of 18.2 Ω cm. Stock nanoparticle dispersion of 100 ppm was prepared by sonication of nanoceria particles. Stock solutions were diluted with E3 to obtain 20, 50, 100 ppm concentration dispersion. The mixtures were sonicated for 10 min before exposure.

2.3. In vitro study of the interaction of nanoceria with 5-HT

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed using a JEOL JSM-2010 instrument. TEM samples were prepared by placing an aliquot of nanoceria dispersion (prepared in E3 medium) on a copper grid and dried under vacuum. UV-VIS spectrophotometric measurements to monitor changes in the spectral properties of nanoceria upon exposure to 5-HT were performed with a Schimadzu P2041 spectrophotometer equipped with a 1-cm path length cell. Particle size distribution (PSD) was investigated using a Zeta PALS from Brookhaven Instrument. Electrochemical measurements to monitor surface reactivity were obtained on an electrochemical analyzer (CH Instrument 1030 B, Houston, TX, USA). Screen-printed carbon electrodes (DRP 110) from DropSens (Spain) were used as transduction support. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out on the same mixture using a Seiko Exstar TG/DTA 6200 thermogravimetric analyser.

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra were performed using a Mattson Galaxy 2020 spectrometer using 100 scans at 4 cm−1 resolution. The samples for FTIR were prepared as pellets using KBr (Sigma Aldrich). To assess the binding of serotonin on nanoceria, the ceria nanoparticles were dispersed in E3 medium and sonicated for 10 minutes. After addition of 5-HT, the suspension was magnetically stirred for 72 h, and filtered under vacuum using filter paper (Watman) with 0.100 µm pore size diameter. This powder was successively washed with DI until the entire amount of weakly adsorbed 5-HT was removed as confirmed by the absence of 5-HT in the washing solution monitored by UV-VIS. After washing, the powder was dried for 48 h under vacuum at room temperature and further analyzed by FTIR.

2.4. In vivo studies to assess intestinal 5-HT in embryonic zebrafish

2.4.1. Fish stock and exposure to nanoceria

Adult AB wild type zebrafish embryos were maintained at 28.5°C on a 14 h light/10 h dark cycle in an Aquatic Habitat recirculating system. Purification of water was conducted through reverse osmosis and pH was adjusted to 7.0 with conductivity of 350 µs. Zebrafish eggs were collected in E3 medium and sorted out by 50 eggs per petri dish. At twenty-four hour post-fertilization (hpf), embryos were manually taken out of their chorion. Prior to nanoparticle exposure, zebrafish embryos were examined under a stereomicroscope for development state. Only healthy embryos were used for further experiments. Selected embryos were divided into 10 per well in 6-well plates and exposed to 3 ml nanoparticle dispersions of specific concentrations (20, 50 and 100 ppm) prepared in E3 medium. At 5 day post-fertilization (dpf), embryos were examined to evaluate the impact of nanoparticles on physiological serotonin levels.

Hatching inhibition tests were conducted on healthy embryos. For each concentration, 10 embryos were used and five replicate sets were analyzed for the statistical accuracy. The number of hatched out embryos were counted every 24 hour for three consecutive days. For malformation and mortality assessment, nanoparticle exposures were carried out in the same experimental conditions as mentioned above. In order to obtain statistically significant data, five replicate set of experiments were done for each concentration, using 10 embryos. The observations were recorded every 24 hours for five days.

2.4.2. Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry analysis of 5-HT levels was performed after fixing the zebrafish embryos in paraformaldehyde (4%) for 2 hours at room temperature. Fixed embryos were washed with PBST and methanol, and kept for 1 h at −20°C. Then, embryos were digested with Proteinase K in PBST for 20 min. at room temperature, and incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibody (rabbit anti-serotonin antibody, 1:500 dilution, Sigma). After the first incubation, embryos were washed with PBST for 45 min and then incubated with secondary anti-rabbit antibody (1:500 dilution in 5% Goat serum, Molecular Probes-Invitrogen) for 2 h. Embryos were washed in PBST for 45 min. Prior to fluorescence microscopy, intestines of embryos were dissected and kept in Vectashield (Vector Lab.). Intestines were analyzed on a Nikon Eclipse TE2000 inverted microscope. Images were displayed using Hamamatsu Orca camera in IP lab software.

2.5. Electrochemical quantification of intestinal 5-HT with the implanted microelectrode

Microelectrodes were fabricated from carbon fibers from WPI (World Precision Instruments Inc.). A single carbon fiber with a diameter of ~ 5 µm was attached to a stretched copper wire through a conductive epoxy obtained from MG Chemicals. The epoxy was cured for 10 min at 100°C. Then, the wire was aspirated into a capillary tube. The top opening of the capillary tube was sealed with a non-conductive epoxy resin cured for 10 min at 100°C. A Narishige PP-83 was used to pull the glass capillary. The pulled end of the capillary tube was sealed with non-conductive epoxy and cured under aforementioned conditions. The length of the carbon fiber protruding from the tip of the electrode was fixed to ~ 0.5 mm from the glass using a scalpel. Electrodes were then treated with isopropanol for 10 min to clean the carbon fiber surface and air-dried. Before further modification of the active surface, microelectrodes were electrochemically cleaned in 0.1 M PBS (phosphate buffer solution, pH 7.0) by repetitive oxidation between −0.4 and 1.4 V at 500 V/s. Microelectrodes were coated with chitosan by dipping into a 1% chitosan solution for 15 s and air-dried for at least 30 min as we described previously 21. The chitosan coated carbon fiber microelectrodes were placed in a sealed box until use. Each microelectrode was tested prior to use. Electrodes that gave readings outside of the standard deviation range were discarded.

All experiments to quantify intestinal 5-HT were performed on live embryos. Pigmented 5 dpf zebrafish larvas were used for electrochemical measurements. Differential pulse voltammetry (DPV) was used for all measurements in a potential range of 0 – 0.8 V. Experiments were carried out using the chitosan modified microelectrode as the working electrode, a Ag/AgCl/3 M NaCl (BAS MF-2052, RE-5B) as reference electrode and a platinum wire as counter electrode following the procedure described previously 21. The scan increment, pulse amplitude, width and period were 4.0 mV, 50 mV, 50 ms and 200 ms respectively. Background voltammograms were recorded in E3 in absence of serotonin and used to obtain the background current. To perform measurements embryos were immobilized on agarose gel. Chitosan coated microelectrodes were inserted into the middle segment of the intestine with a micromanipulator and a DPV voltammogram was recorded. All voltammograms are shown after background subtraction. Each carbon fiber microelectrode was used for single in vivo experiments. All values are reported as the mean ± standard deviation for at least three replicate measurements with at least three embryos.

3. Results

3.1. Physicochemical characterization of nanoceria

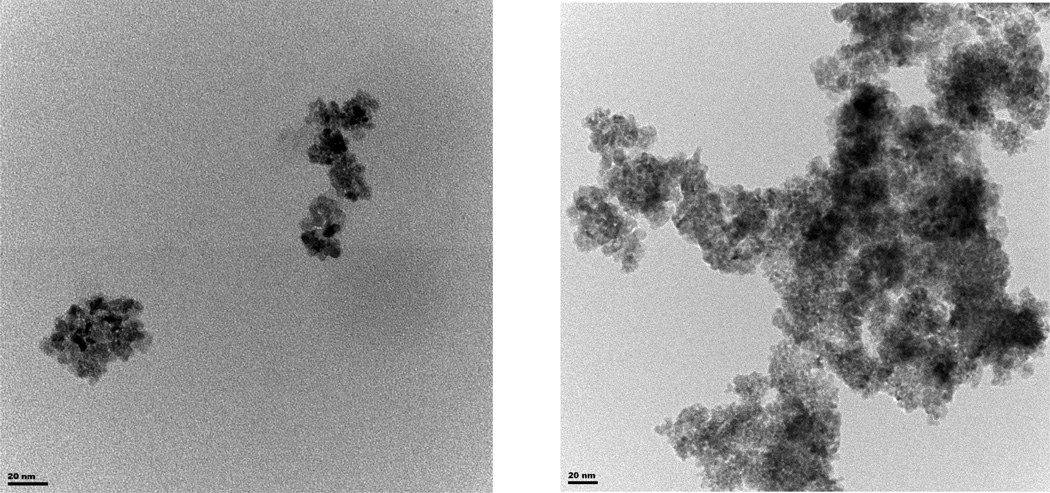

To define the potential neurotoxic effects of nanoceria on 5-HT, we first characterized the physicochemical properties and aggregation profile of these particles in aqueous suspensions and in the zebrafish embryo medium (egg water, E3). Figure 1 illustrates the TEM analysis of nanoceria (Figure 1A) and 5HT-nanoceria complex (Figure 1B). Particles appear as clusters composed of small 2–5 nm nanocrystalline grains with an average size of ~ 20–40 nm (Figure 1A). Incubation with 5-HT resulted in enhanced agglomeration of nanoparticles (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

TEM micrograph of (A) nanoceria and (B) 5HT-nanoceria. Nanoceria dispersion was prepared in E3 medium.

3.2. Interaction of nanoceria with 5-HT in vitro

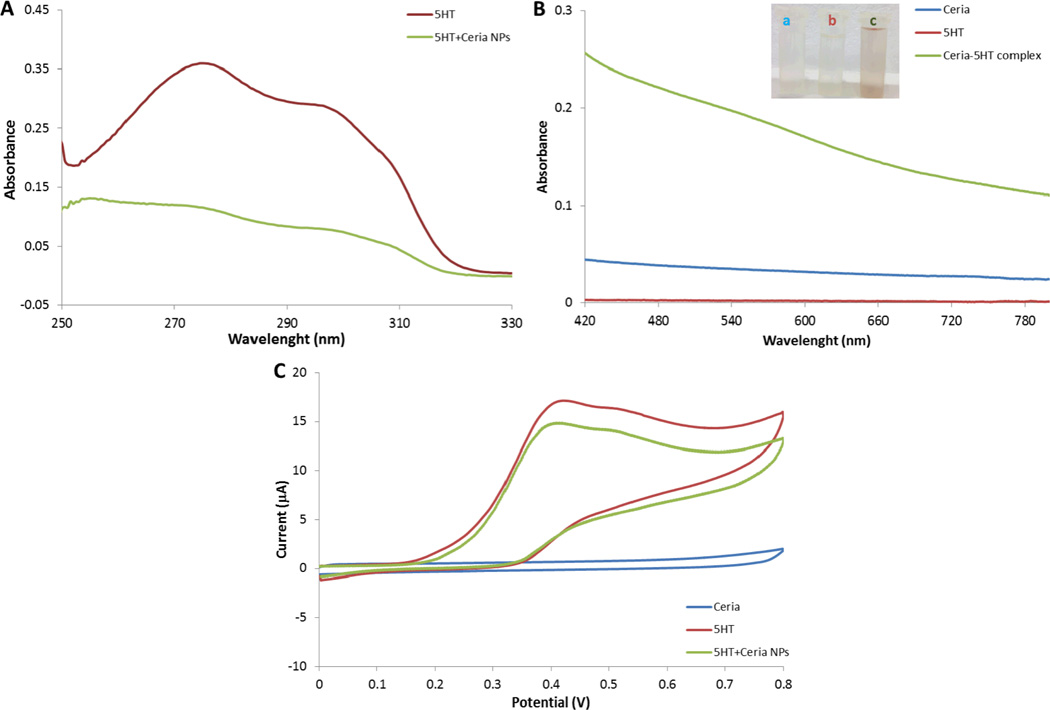

The effect of nanoceria on the 5-HT level was assessed by spectroscopic and electrochemical methods of 5-HT in the presence and absence of particles. Experiments were performed in E3 as this medium was further used in the neurotoxicity assessment studies in zebrafish. 5-HT has a broad characteristic absorption peak in the range of 250 to 310 nm in the UV region.32 Ceria nanoparticles have a characteristic absorption band with a maximum at ~300 nm corresponding to the band gap of CeO2 due to the charge transfer between O2p and Ce4f in O2− and Ce4+ 33 that overlaps to that of 5-HT. Figure S1 in the supplementary information shows the UV-VIS spectra of nanoceria and 5-HT in the range from 250 to 800 nm. Unfortunately, overlapping peaks of nanoceria and 5-HT in the 250 – 330 nm range makes analysis difficult in this region. Therefore, to study the effect of the nanoparticle on 5-HT degradation, we recorded the spectra of the supernatant after centrifugation and filtration. Figure 2A shows the absorption spectra of 5-HT before and after incubation with the nanoparticles. The intensity of the 5-HT absorption peak decreases after exposure to nanoceria which suggests a change of 5-HT concentration in solution, with simultaneous inactivation of the active nanoparticles surface. In the same time, there is an increase of the absorption band in the VIS range as shown in Figure 2B, which indicates formation of a new conjugated complex between nanoceria and 5-HT. The absorption spectra in the VIS range from 425 to 800 nm of 5-HT and the nanoparticles alone and after incubation are shown in Figure 2B. Neither 5-HT nor nanoceria alone show absorption peaks in this range. However incubation of 5-HT with the particles led to an intensity increase in the absorption spectra with a maximum absorbance peak at ~530 nm. The kinetic behavior of this reaction is slow, reaching a maximum after three days incubation. Such changes are not observed with 5-HT alone in the absence of nanoparticles. The observed spectral enhancement provides evidence that 5-HT interacts with nanoceria. A similar trend was observed when we used electrochemistry to study the redox behavior of 5-HT before and after exposure to nanoceria (Figure 2C). The oxidation potential of 5-HT determined by cyclic voltammetry of a 5-HT solution at a carbon-based screen printed electrode surface is 0.4 V vs Ag/AgCl reference electrode. A decrease in the electrochemical response was observed when nanoceria particles were added to the solution indicating reduction of the 5-HT concentration. No additional peak was observed in the oxidation potential window, suggesting that the newly formed 5-HT-nanoceria complex is adsorbed onto the particles surface.

Figure 2.

UV spectra of 5-HT in the presence and absence of nanoceria (A). VIS spectra of 5-HT (B), CeO2 nanoparticles, and 5-HT after incubation with nanoceria in E3 medium. Cyclic voltammograms of 5-HT in the presence and absence of nanoceria (C). All experiments were conducted with 3 mM 5-HT and 50 ppm nanoceria dispersion.

A possible mechanism involves oxidation of 5-HT by nanoceria with formation of dihydroxiderivatives or unstable quinone-indole-like derivatives, which have been reported previously as oxidation products of 5-HT 34. Further these oxidation products can chemisorb onto the OH-rich nanoparticles and form strongly bound charge transfer complexes or 5-HT-modified nanoceria with Ce-catecholate types adsorbates. These complexes are characterized by enhanced optical and charge separation properties, similar to what we have found previously with ceria and other types of phenolic compounds 35. This finding is in line with other works on metal oxide nanoparticles, mainly titanium dioxide, reporting surface adsorption of phenolic type compounds onto the particle surface36. Oxidation and chemisorption of 5-HT onto nanoceria raise interesting questions on whether internalized nanoceria particles can accumulate 5HT in vivo, potentially depleting the local 5-HT level in the surrounding tissue. This might affect the 5-HT level in living organisms that are exposed to these particles, inducing potential physiological alterations.

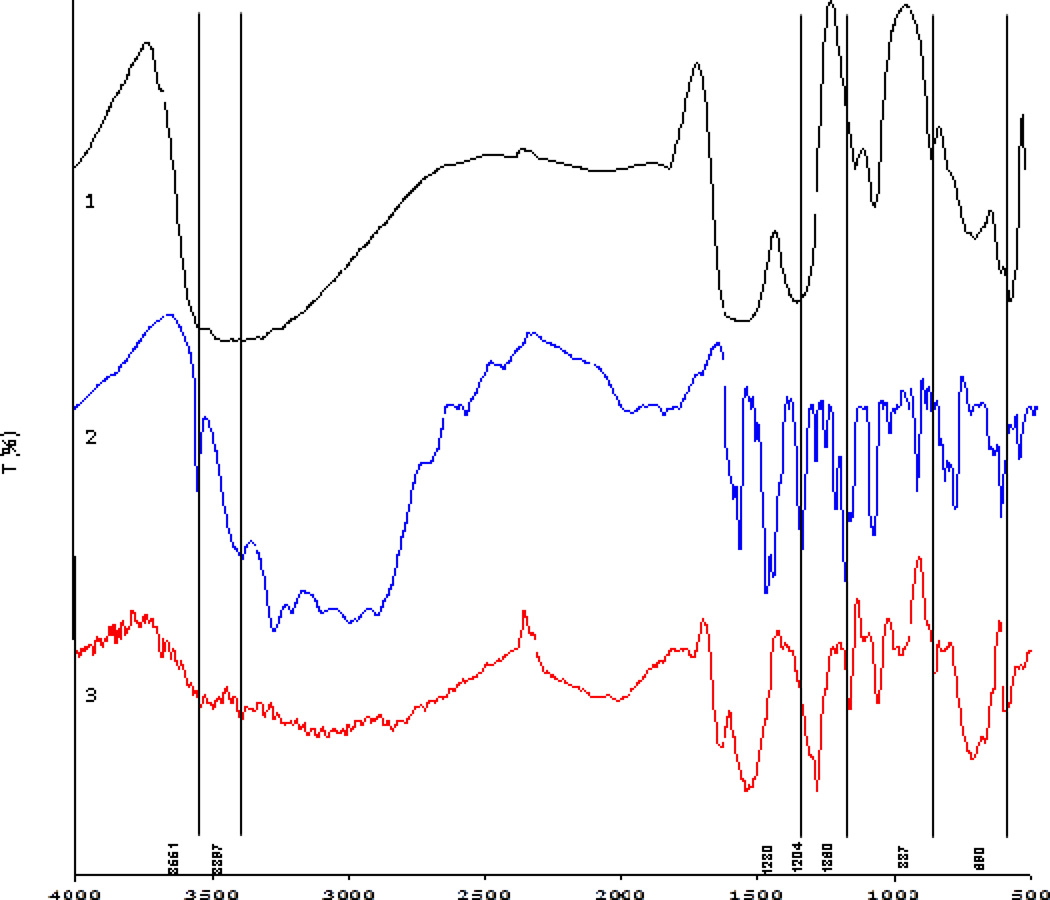

To further investigate whether 5-HT attaches to nanoceria we have used surface and compositional analysis methods to determine the type and effect of this interaction. First, the presence of 5-HT on the surface of the particles was assessed using FTIR by comparing the spectra of nanoceria, 5-HT and the 5-HT-nanoceria complex, after washing and drying. Figure 3 shows the FTIR spectra of ceria (1), 5-HT (2) and 5-HT modified ceria nanoparticles (3) between 400 and 4000 cm-1 (3). The characteristic bands of ceria have been seen at 400 and 700 cm-1 corresponding to the stretching vibrations of Ce-O in CeO2 molecules 37. The broad band between 3300 and 3600 cm-1 corresponds to the O-H stretching vibrations of the physical absorbed water molecules and the surface −OH groups. The bands at 1620 and 1540 cm-1 are due to the bending vibrations of the hydroxyl groups of water molecules 37. The 5-HT spectrum shows the characteristic vibrations of the indole ring, ethylamine chain and hydroxyl groups: the strong vibration at 3551 cm-1 is associated with the N-H stretch of the indole ring and the band at 3397 cm-1 corresponds to the asymmetric stretching vibrations of the −NH2 group in the ethylamine side chain. Other specific characteristics of primary amine groups are seen at 937 and 837 cm-1 corresponding to C-N stretching and NH2 symmetric stretching 38. The stretching vibrations of the aromatic ring ν(C-C)/ν(C=C) are seen at 1607, 1582, 1487 and 1462 cm-1. The stretching vibrations of the phenolic group ν(C-OH) are present at 1360, 1309 and 1270 cm-1, while the bending of the phenolic group δ(C-OH) is present at 1360 and 1234 cm-1. The C-O stretch is at 1204 cm-1. The spectrum of 5-HT-nanoceria mixture shows the characteristic bands of ceria as well as the bands of the indole and benzene ring and those associated with the ethylamine chains of 5-HT demonstrating the presence of 5-HT onto the particles. The stretching vibration band of the C-O group is seen at 1280 cm-1. The presence of the amino functional groups of the 5-HT in the 5-HT-ceria mixture indicates that this group is not involved in the surface binding. However, the bands associated with the -OH groups in the 1200 – 1400 cm-1 range are absent, indicating that the OH groups are involved. These findings provide structural evidence that 5-HT is attached to the nanoparticles surface through the hydroxyl groups.

Figure 3.

FTIR spectra of CeO2 nanoparticles (1), 5-HT (2) and CeO2 nanoparticles incubated with 5-HT (3). All experiments were conducted with 3 mM 5-HT and 50 ppm nanoceria dispersion.

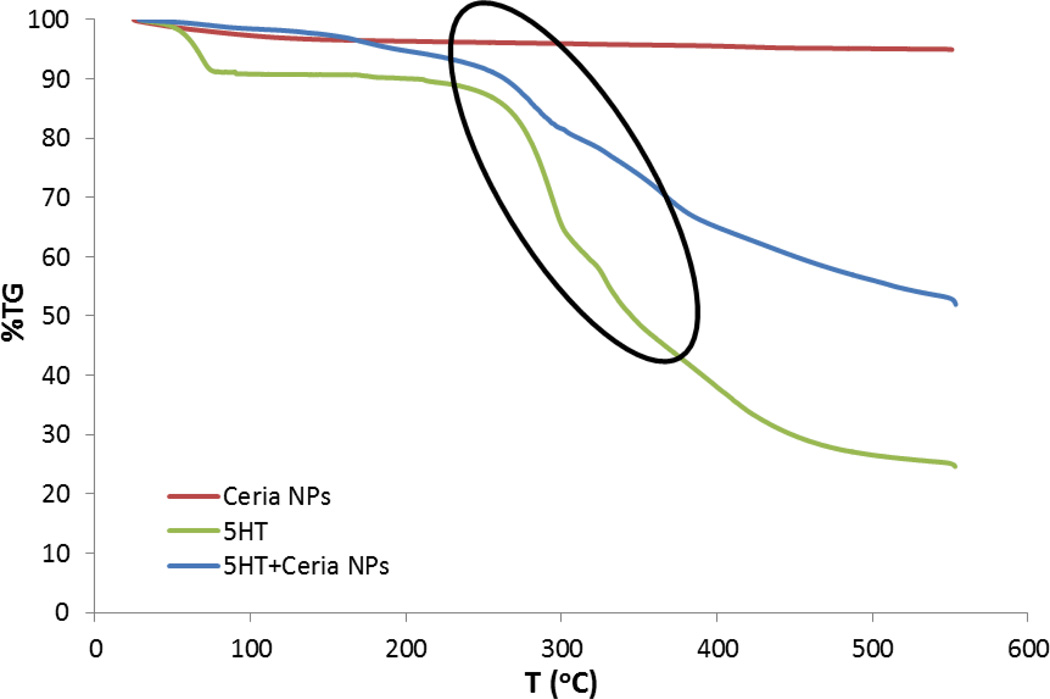

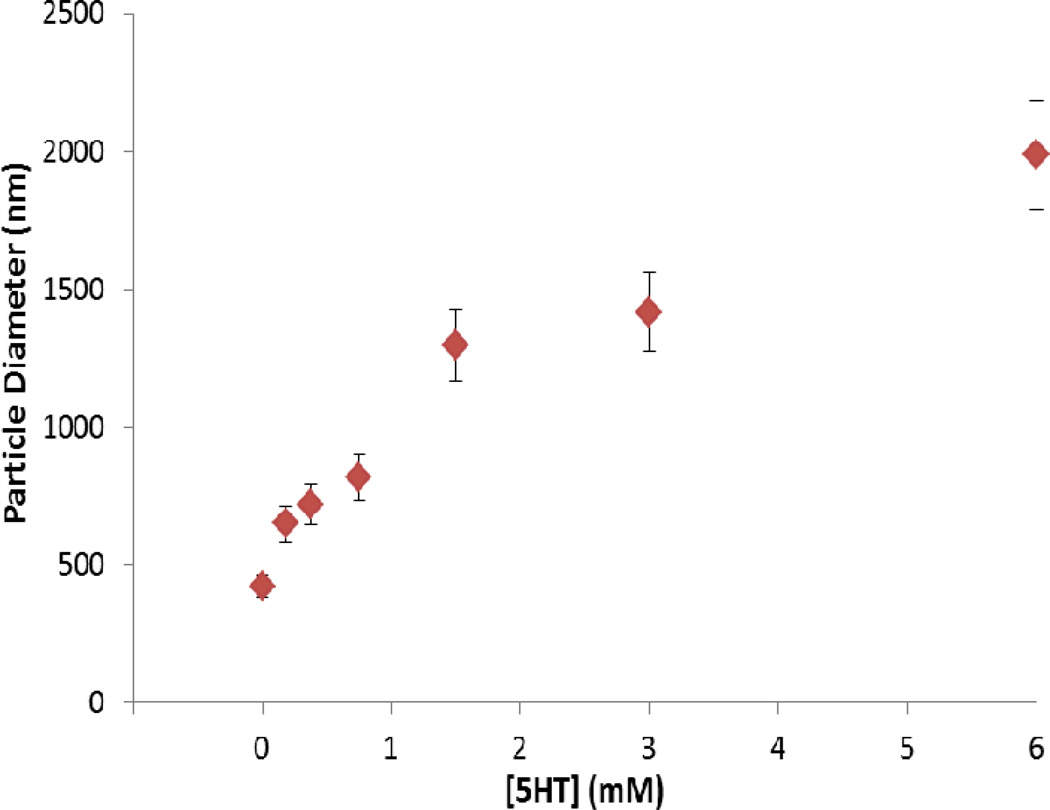

The 5-HT exposed nanoparticles were further characterized by TGA to study the surface coverage and further confirm attachment of 5-HT. The TGA curves obtained for standard 5-HT powder, nanoceria and nanoceria incubated with 5-HT (after washing and drying) are shown in Figure 4. A gradual weight loss at 290 C° was observed for standard 5-HT powder. The negligible weight loss observed in the standard TGA spectra of particles corresponds to the loss of surface adsorbed water. The TGA spectra of the 5-HT-nanoceria complex shows a significant weight loss at 290 C° which clearly demonstrates the presence of 5-HT on the surface of the particles. This finding is in good agreement with the FTIR spectrum of 5-HT modified ceria (Figures 3). Since the sample has been washed several times to eliminate weakly adsorbed 5-HT, this result indicates a strong interaction between 5-HT and nanoceria. 5-HT binding capacity of nanoceria, estimated from the TGA data, indicate a surface coverage of ~ 70 µmol 5-HT/m2 nanoceria. We further studied whether 5-HT affects the hydrodynamic size of the nanoceria and the aggregation behavior. Particle size distribution of the nanoparticles dispersed in E3 exhibited an average size of 420.5 nm. Addition of increasing concentrations of 5-HT to the ceria dispersion generates an increase in the particle size with formation of large aggregates at high 5-HT concentrations (Figure 5). The increase in particle size with increasing concentrations of 5-HT indicates formation of a 5-HT layer onto the nanoparticle surface.

Figure 4.

Thermogravimetric analysis of CeO2 nanoparticles, 5-HT and CeO2 nanoparticles incubated with 5-HT.

Figure 5.

Particle size distribution of CeO2 nanoparticles with increasing concentration of 5-HT.

Since the NH2 functional groups in 5-HT are intact, a possible attachment is through the OH group in the 5-HT structure (or the dihydroxiderivatives or quinone imine derivatives of its oxidation product by nanoceria) that can form strong coordinate bounds with the OH rich ceria surface. Thus, 5-HT can attach to the nanoceria surface forming a 5-HT corona with 5-HT assembled around the particle. Formation of ceria-quinone-imine type ligands is also possible through initial oxidation of 5-HT by ceria, by virtue of their redox reactivity. These compounds are highly reactive and the oxidation process can also involve highly reactive radical species. At excess 5-HT concentrations, they can interact with each other and form dimers or larger aggregates, inducing particle agglomeration, as we have seen by the particle size analysis in Figure 5.

Taken together, these results provide evidence that a conjugated complex is formed between 5-HT and nanoceria. The appearance of a new absorbance peak in the VIS region correlated with the increase of the hydrodynamic diameter as well as the FTIR and TGA data of the 5-HT presence onto nanoceria indicate strong attachment of 5-HT to the nanoparticle surface. These findings suggest that nanoceria may affect the metabolism of 5-HT by oxidation and binding to the particle with a first possible effect resulting in a decrease of 5-HT levels in biological systems. To further study the effect of these particles in realistic exposure conditions and assess biological effects we have selected zebrafish embryo as a model organism that has increased 5-HT level in the intestine. Further experiments were performed on nanoceria-exposed embryos to assess the effect of internalized particles on intestinal 5-HT level.

3.3. Effect of nanoceria exposure on 5-HT level in live embryonic zebrafish

3.3.1. Intake and localization of nanoceria in the intestinal lumen

To confirm the internalization of ceria nanoparticles, healthy embryos at 5 dpf were selected and incubated in a fresh 50 ppm nanoceria dispersion prepared in egg water for 5 hour period at 28.5°C. Following nanoparticle exposure, zebrafish embryos were washed and fixed for the cross-section imaging. Intestinal cross-sections reveal the presence of particles within the lumen, demonstrating that nanoparticles were taken up and internalized by the embryos (Figure 6). This indicates that even though particles form aggregates upon dispersion in the E3 medium, they are still ingested during development. To further confirm presence and identity of internalized nanoceria, exposed embryos were digested by nitric acid and the amount of cerium ions was estimated using direct potential amperometry to confirm both the amount and the identity of dissolved species (dissolved cerium ions have a characteristic reduction potential of −1.45 V vs a Ag/AgCl reference electrode). Digestion of 150 embryos exposed to 100 ppm nanoceria resulted in a concentration of internalized cerium of 4.65 (± 0.05) ppm upon 4 days exposure.

Figure 6.

Cross-section of the intestine of exposed embryos showing internalization of particles within the intestinal lumen (accumulated particles shown by the arrows).

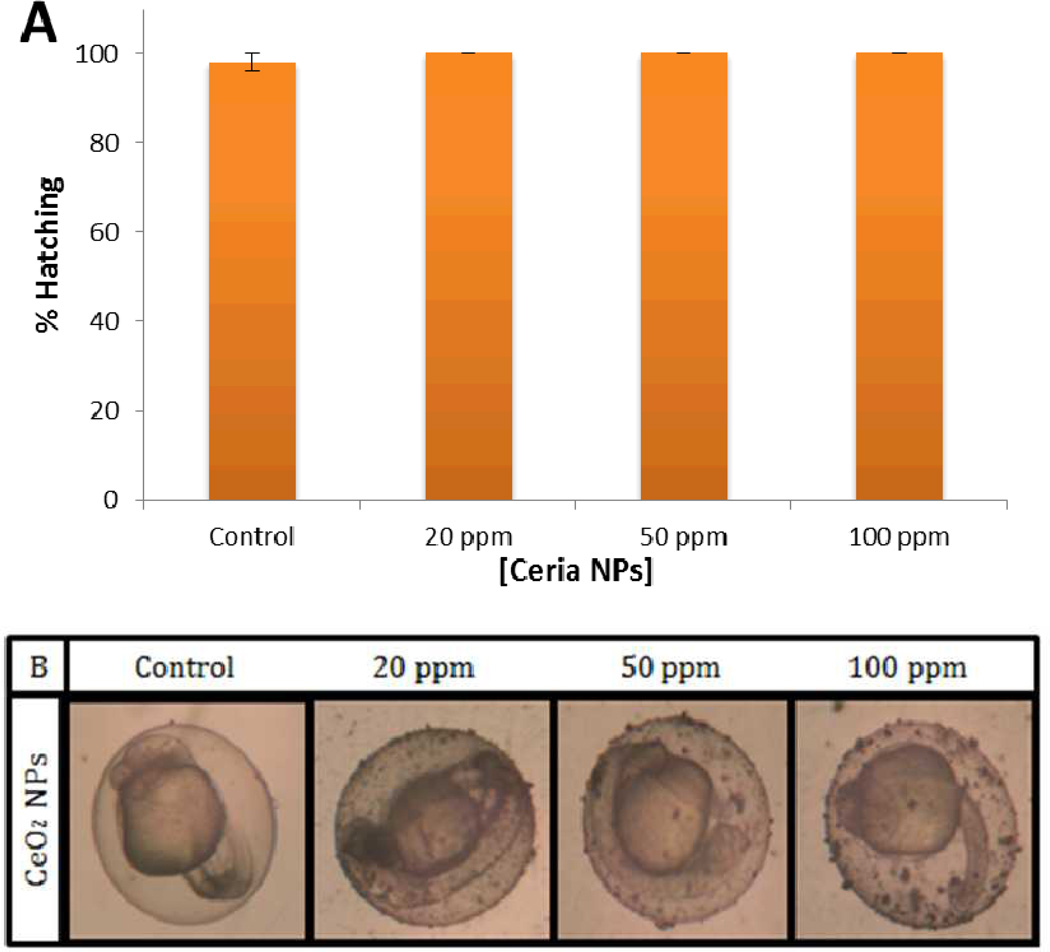

3.3.2. Effect of nanoceria on hatching and viability rate

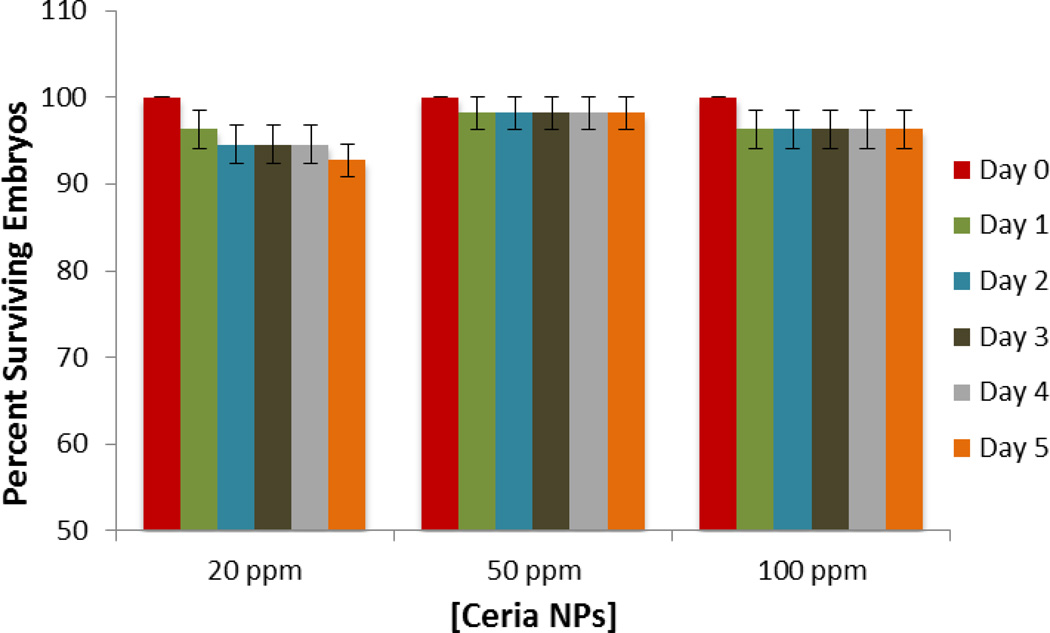

Initial in vivo studies were designed to assess the effect of nanoceria exposure on the physiology of the embryos and determine whether these particles induce developmental defects and cytotoxicity. Hatching and viability rates were used as an indicator of the overall health condition of the developing embryo. Hatching from the chorion is a developmentally timed event. Embryos remain in the chorion on average up to 72 hpf 39. As the embryo develops, enzymes are produced by the hatching gland, which digests the inner layer of the chorion, allowing the embryo to escape as a result of increasing movements 40, 41. We exposed embryos to increasing nanoparticle concentrations ranging from 20 to 100 ppm. No significant changes in hatching rates were observed after exposure for any of the tested concentrations, as compared to control unexposed embryos (Figure 7A). Negligible changes in hatching rates suggest that there is little to no developmental toxicity induced by exposure to nanoceria. Microscopic images in Figure 7B show accumulation of nanoceria on the chorion, with agglomeration increasing with increased doses of nanoparticles. To further assess toxicity, embryos were examined for developmental defects and viability upon exposure to various nanoceria concentrations exposure during five day period. Dose and time-dependent exposure to doses ranging from 20 to 100 ppm displayed similar trends as the hatching rate analysis (Figure 8). There were no significant changes in viability; however 20 ppm nanoceria exposure resulted in a slight reduction in survival rate (< 8%) which could be due to a higher intake of nanoceria (lower nanoparticle concentration showed reduced aggregation in E3 medium). No developmental malformations were observed indicating that embryos maintain normal physical development in these exposure conditions. We stress however that while developmental defects were not observed, these indicators are not sensitive enough to identify physiological changes.

Figure 7.

Effect of CeO2 nanoparticle exposure on hatching rate and embryonic development. Evaluation of the hatching percentage of zebrafish embryos at 72 hpf exposure to increasing doses of nanoceria (A). Microscope pictures showing nanoparticle accumulation on zebrafish eggs as a result of exposure as compared to unexposed control embryos (B). The average percentage values were calculated from 5 replicate trials, consisting of 10 embryos per each concentration. Error bars represents ± mean standard deviation.

Figure 8.

Viability of zebrafish embryos exposed to various concentrations of CeO2 nanoparticles. The average percentage values were calculated from 5 replicate trials of 10 embryos per each dose. Error bars represents ± mean standard deviation.

3.3.3. Effect of nanoceria exposure on intestinal 5-HT

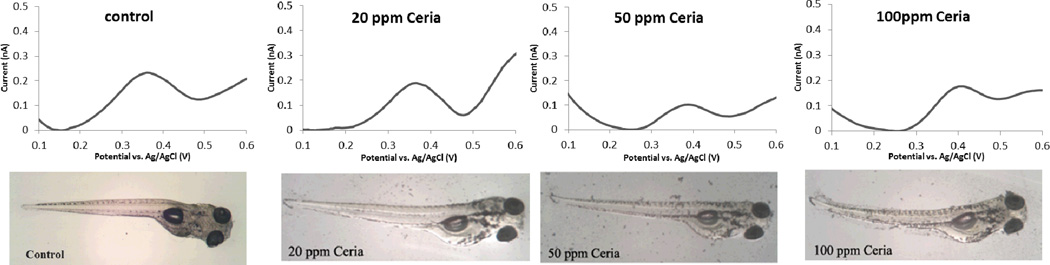

To quantitatively assess 5-HT concentrations within the zebrafish intestine and determine whether 5-HT levels are affected by nanoceria exposure, we used electrochemical microsensors, locally inserted in the intestine. Previously, we have demonstrated the use of chitosan coated carbon fiber microelectrodes to quantitatively determine 5-HT concentrations in the intestine of 5 days post-fertilization (dpf) zebrafish embryos with high sensitivity and selectivity42, 43. In the intestine, 5-HT is produced by enteric neurons and enterochromaffin cells (EC), which are responsible for the production, storage and release of 5-HT from the intestinal epithelium. As shown by our in vitro results, exposure of nanoparticle could potentially change the basal 5-HT levels by forming 5-HT-nanoceria complexes. We therefore inserted a single microelectrode in the mid-intestine to assess changes in 5-HT concentration in zebrafish embryos exposed to nanoceria. We used DPV as a signal transduction method and performed electrochemical measurements as we described previously 42, 43. Embryos were treated with nanoparticle dispersions prepared in E3 after manual removal of the chorion at 24 hour post-fertilization (hpf). Nanoparticle concentrations tested ranged from 20 to 100 ppm. Embryos were incubated with nanoceria dispersions until 5 dpf. At 5 dpf, individual embryos were removed from the exposure medium, placed in an agar plate containing E3 and analyzed for the intestinal 5-HT concentration by performing DPV measurements of the 5-HT oxidation using a chitosan modified single CFME implanted in the mid-intestine. At least 3–5 embryos from each exposure group were analyzed to obtain statistically representative readings. Changes in the basal 5-HT levels of exposed embryos were compared with control embryos in the absence of particles.

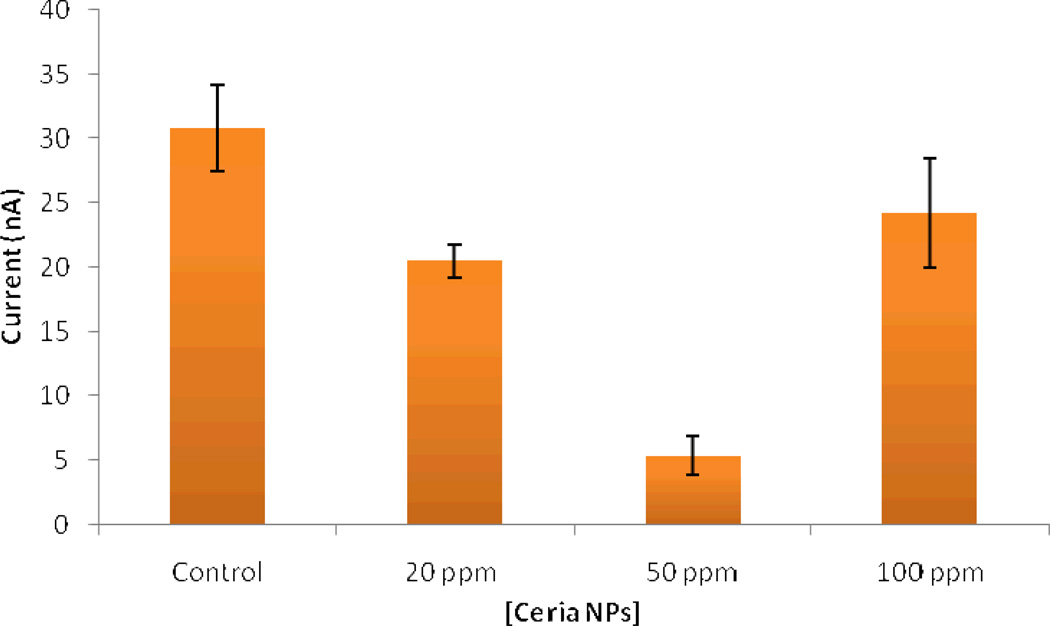

Figure 9 shows DPV measurements of 5-HT in control and nanoparticle exposed embryos. The peak at 0.39 V corresponds to the oxidation potential of 5-HT at the CFME surface. The intensity of the current at that potential was used to determine quantitatively the 5-HT by correlation to a calibration curve, as described previously 42. The concentration of 5-HT in unexposed zebrafish embryos quantified by voltammetry is 30.8 (±3.4) nM. Embryos exposed to 20 and 50 ppm concentrations of CeO2 nanoparticles exhibited significantly lower levels of 5-HT (Figure 10) that could be attributed to surface adsorption of 5-HT, as demonstrated in the in vitro study. The concentration of 5-HT determined after the exposures to 20 and 50 ppm dispersions are 20.5 (±1.3) and 5.3 (±1.5) nM respectively. With 100 ppm exposure, nanoparticles began to create visible agglomerations in E3. A concentration of 24.2 (±4.2) nM 5-HT was measured in this case. This relative increase in the 5-HT level as compared to those observed for 20 and 50 ppm could be due to the increased aggregation of particles in the E3 medium, which decreases the uptake by the embryos.

Figure 9.

Differential pulse voltammograms (top panel) and microscope images (lower panel) of unexposed control embryos and embryos treated with 20, 50 and 100 ppm nanoceria dispersion. Microelectrodes were implanted to mid-intestine of live embryos. The supporting electrolyte was E3 medium.

Figure 10.

Intestinal 5-HT concentration of embryos exposed to CeO2 nanoparticle dispersions with concentration ranging from 20 to 100 ppm, as determined from the differential pulse voltammetric responses obtained in vivo at 5 dpf with the implanted microelectrodes. The error bars represent standard deviation for n = 3–5 replicate measurements.

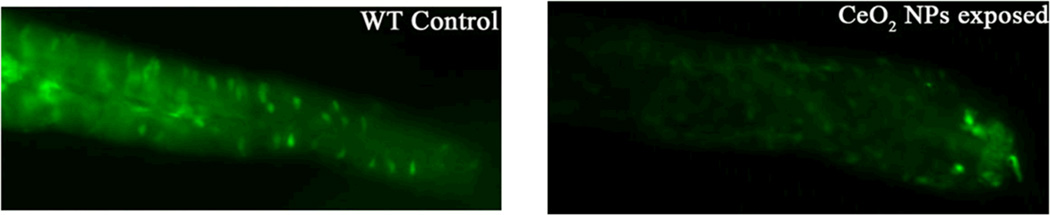

To further confirm the decrease in the intestinal 5-HT level and validate the observed electrochemical signals, 5-HT immunohistochemistry was performed on 5 dpf embryos (Figure 11). Exposure of 50 ppm nanoparticles to 5 dpf embryos decreased the fluorescence intensity when compared to unexposed embryos. This provides further evidence that exposure to nanoceria reduce the 5-HT level in the intestinal lumen of zebrafish embryos.

Figure 11.

Anti-5-HT immnunohistochemistry of embryos treated with 50 ppm nanoceria compared to unexposed control embryos. 5-HT level of exposed embryos reduces drastically throughout the intestine. All micrographs show dissected embryonic intestines and are in the same scale. Intestine is shown from anterior to posterior (from left to right).

3.3.4. Changes of the intestinal 5-HT levels depend on nanoceria exposure time

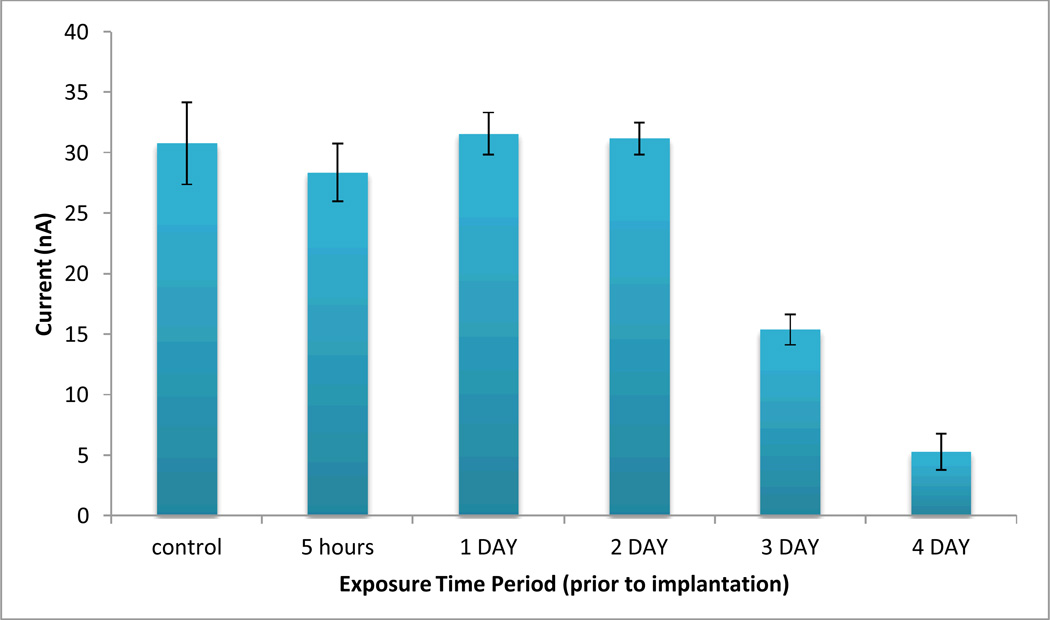

With the previous experiments, embryos were exposed to nanoparticles throughout embryogenesis. In the experiments in this section we exposed embryos to nanoparticle at either growth or differentiation phase before determining the 5-HT concentration at 5 dpf. We choose a concentration of 50 ppm which demonstrated a more dramatic affect on 5-HT. Initial experiments were performed with embryos exposed to nanoparticles for periods of 5, 24 and 48 hours prior to detection at 5 dpf. 5-HT levels of embryos exposed for these exposure times did not show significantly different levels as compared to the control (Figure 8). 5-HT concentrations observed was within the control embryo’s range (29.7 (+ 6.7) nM) We next exposed embryos to 50 ppm nanoceria dispersion for periods of 3 and 4 days prior detection 5-HT. The results summarized in Figure 12 indicate that longer exposure times result in decreased 5-HT levels in the intestinal lumen. This finding is consistent with our in vitro results that demonstrated slow kinetic of the interaction of 5-HT with nanoceria as evidenced by the spectral changes after 3 days incubation. Since the binding is time-dependent, longer retention time of nanoceria within the intestinal lumen decreases drastically physiological 5-HT levels.

Figure 12.

Effect of exposure time of the embryos to nanoceria on intestinal 5-HT levels. Dechorionated embryos were exposed to 50 ppm concentration dispersion. Each bar illustrates the average voltammetric signal recorded by the implanted microelectrode at 5 dpf. The error bars represent standard deviation for n = 3–5 replicate measurements in individual embryos exposed to identical conditions. The supporting electrolyte was E3 medium.

4. Discussion

With widespread interest in using nanoceria in biology and medicine, understanding the physiological effects is critical. These nanoparticles are currently being considered for biomedical applications to treat oxidative stress related diseases by inactivating free radicals 44, 45. Successful implementation in clinical applications requires investigation of the effect and cytotoxicity of these particles. However, despite the great promises shown by these particles by virtue of their antioxidant properties, there is still debate on their toxicological impact in living organisms. Depending on the physicochemical properties (size and surface coating) and biological model used both beneficial 44 and adverse toxic 46 effects have been reported.

Due to their dual oxidation state and redox reactivity, these particles can participate in redox reactions with cellular and tissue components, many of which are redox active including ascorbic acid, melatonin, dopamine, adrenaline and serotonin. Thus, there is possibility for nanoceria to interact with these compounds and induce secondary effects on the redox metabolism of biological systems upon nanoparticle uptake. Nanoceria can act as an oxidizing agent 47 and therefore can change physiological levels of oxidizable species in living organisms. Moreover, in physiological conditions these particles have rich surface OH functionalities that can interact with other OH-rich compounds and form surface complexes. Other metal oxides are also known to bind catecholamines, e.g. titania and iron oxide nanoparticles have been shown to bind dopamine 48, 49. Very little is known about the uptake of nanoceria particles and their effects on the physiology and neural function of living organisms.

This study investigated the impact of nanoceria on 5-HT, a redox active neurotransmitter widely distributed in living organisms. Changes in 5HT concentration play an important role in intestinal motility and luminal secretion, as well as in a variety of other neurological and motor functions in the body. In vitro tests were performed to establish the reactivity of nanoceria with 5-HT prior to in vivo exposure experiments. Our results have provided several lines of evidence suggesting that a complex is formed upon addition of 5-HT to nanoceria, and formation of this complex might lead to a decreased 5-HT level by chemisorption onto the surface of the particles. Responsible for this behavior is oxidation of 5-HT by nanoceria followed by attachment of 5-HT and its oxidation products to the nanoparticle surface. Observed changes in the UV-VIS spectra and the electrochemical oxidation current of 5-HT incubated with nanoceria indicated a general decrease in the 5-HT concentration with formation of a new conjugated complex of 5-HT with ceria, revealed by appearance of a new peak in the VIS range. Further analysis of this complex by DLS, FTIR and TGA methods demonstrated presence of the 5-HT structural characteristics on the exposed particles, and an enlargement in the particle size that increases with increasing 5-HT concentration. These demonstrate strong attachment of 5-HT or its oxidation products onto the nanoparticle surface, which is responsible for the observed decrease in 5-HT concentration. Depletion in 5-HT levels can have profound consequences on the neurophysiology of living organisms.

Questions about the potential neurotoxic effects of engineered nanoparticles are beginning to be raised50. The results described here provide evidence of the potential neurotoxic effect of these particles and suggest that nanoceria can reduce 5-HT levels through oxidation and surface adsorption. Oxidation products of 5-HT are known to be neurotoxic 51 and can generate radical intermediates in the process and form dimers that by themselves can induce toxic effects. These include a complex array of derivatives of which dihydroxiderivatives and reactive quinone imine are the most prominent34. In the presence of redox active nanoceria, the oxidation products and intermediary reactive species bind to the particle surface, which makes identification of these species challenging. The fate and toxicity of surface adsorbed 5-HT and its oxidation products onto metal oxide nanoparticles are not known and require further study. Our data suggest that particles internalized in biological tissues could act as an accumulation site for 5-HT, depleting the 5-HT level in the surrounding environment.

To demonstrate whether such effects are observed in vivo, we utilized zebrafish embryos to investigate alterations of intestinal 5-HT levels arising from exposure and internalization of nanoceria within the intestinal lumen. Embryos were exposed to different concentrations of nanoceria particles over various time periods. We demonstrate ingestion of nanoparticles within the intestinal lumen, visualized by histological cross-section. Using electrochemical measurements with implanted carbon fiber microelectrodes we showed alterations of intestinal 5-HT of embryos exposed to nanoceria. A decrease in the 5-HT level was observed for 20 and 50 ppm nanoparticle exposure. While there was also a slight 5-HT decrease with the 100 ppm exposure, this was not as low as with 20 and 50 ppm. This may be due to a higher nanoparticle agglomeration behavior. The same trend was confirmed with immunohistrochemistry, which showed a similar decrease in the fluorescent intensity of intestinal 5-HT upon exposure of embryos to same nanoparticle concentrations. We also found differences in the 5-HT level due to different exposure times. Generally, 5-HT depletion was observed for exposure times ranging from 3 to 4 days. No significant changes were observed for short incubation times. While obvious developmental malformations and defects were not observed in this study with the exposure levels studied, higher internalization of nanoceria and longer exposure times could potentially result in further 5-HT depletion and might affect body length, locomotor behavior and serotonin message related expression 52.

The results of the in vitro and in vivo studies described here have demonstrated that nanoceria have potential neurotoxic effects upon interaction with 5-HT and alterations in 5-HT concentration. Similar effects may also be observed with other redox neurotransmitters and other organ systems. These findings indicate the need to further evaluate the effect of nanoceria on other monoamine neurotransmitters and their impact on physiology before these particles can be widely used in pharmacology and biomedicine.

5. Conclusions

The safe implementation of nanoceria in clinical applications requires evaluation of the properties of these particles that might cause cytotoxic reactions in organisms. We have performed both in vitro and in vivo exposure studies to investigate the physiological effect of redox active nanoceria on 5-HT, an important neurotransmitter widely distributed throughout the body. The in vitro work indicates that nanoceria interacts with 5-HT and forms surface adsorbed 5-HT-nanoceria complexes. The in vivo results indicate depletion of 5-HT level in the intestinal lumen of zebrafish embryos after 3–5 days exposure. No significant impact on the 5HT level was observed for short time exposure. These studies suggest that internalized nanoceria particles can slowly accumulate 5-HT at the nanoparticle accumulation site depleting it from the surrounding tissue. Long term exposure could result in alteration of the neurological system.

In conclusion, interaction of redox active nanoparticles with 5-HT and potentially with other redox components commonly present in biological systems should be studied and taken into account when using these particles for biomedical applications in living systems. Further studies are warranted to better understand their physiological effects following longer term exposure in living organisms.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants NSF-0954919 to SA and NIH 1R15DK089474-01 to KW. The authors also acknowledge a seed grant from the Institute for a Sustainable Environment at Clarkson University. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation or the National Institute of Health.

References

- 1.Yamada T, Iwasaki Y, Tada H, Iwabuki H, Chuah MKL, VandenDriessche T, Fukuda H, Kondo A, Ueda M, Seno M, Tanizawa K, Kuroda S. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:885–890. doi: 10.1038/nbt843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee KJ, Nallathamby PD, Browning LM, Osgood CJ, Xu XHN. Acs Nano. 2007;1:133–143. doi: 10.1021/nn700048y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nel A, Xia T, Madler L, Li N. Science. 2006;311:622–627. doi: 10.1126/science.1114397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy M, Luciani N, Alloyeau D, Elgrabli D, Deveaux V, Pechoux C, Chat S, Wang G, Vats N, Gendron F, Factor C, Lotersztajn S, Luciani A, Wilhelm C, Gazeau F. Biomaterials. 2011;32:3988–3999. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horie M, Kato H, Fujita K, Endoh S, Iwahashi H. Chem Res Toxicol. 2012;25:605–619. doi: 10.1021/tx200470e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rivera Gil P, Oberdorster G, Elder A, Puntes V, Parak WJ. Acs Nano. 2010;4:5527–5531. doi: 10.1021/nn1025687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu J, Wang C, Sun J, Xue Y. Acs Nano. 2011;5:4476–4489. doi: 10.1021/nn103530b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Win-Shwe TT, Fujimaki H. Int J Mol Sci. 2011;12:6267–6280. doi: 10.3390/ijms12096267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hu YL, Gao JQ. Int J Pharmaceut. 2010;394:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patil S, Sandberg A, Heckert E, Self W, Seal S. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4600–4607. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Erica S, Daniel A, Silvana A. Oxidative Stress: Diagnostics, Prevention, and Therapy. vol. 1083. American Chemical Society; 2011. pp. 235–253. ch. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Estevez AY, Pritchard S, Harper K, Aston JW, Lynch A, Lucky JJ, Ludington JS, Chatani P, Mosenthal WP, Leiter JC, Andreescu S, Erlichman JS. Free radical biology & medicine. 2011;51:1155–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rzigalinski BA, Bailey D, Chow L, Kuiry SC, Patil S, Merchant S, Seal S. Faseb J. 2003;17:A606–A606. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tarnuzzer RW, Colon J, Patil S, Seal S. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2573–2577. doi: 10.1021/nl052024f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen JP, Patil S, Seal S, McGinnis JF. Nat Nanotechnol. 2006;1:142–150. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2006.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Das M, Patil S, Bhargava N, Kang JF, Riedel LM, Seal S, Hickman JJ. Biomaterials. 2007;28:1918–1925. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.11.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tarnuzzer RW, Colon J, Patil S, Seal S. Nano Lett. 2005;5:2573–2577. doi: 10.1021/nl052024f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pirmohamed T, Dowding JM, Singh S, Wasserman B, Heckert E, Karakoti AS, King JE, Seal S, Self WT. Chem Commun (Camb) 46:2736–2738. doi: 10.1039/b922024k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korsvik C, Patil S, Seal S, Self WT. Chemical Communications. 2007:1056–1058. doi: 10.1039/b615134e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smythies J, Galzigna L. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 1998;1380:159–162. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(97)00131-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.den Hertog J. Bioscience Rep. 2005;25:289–297. doi: 10.1007/s10540-005-2891-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill AJ, Teraoka H, Heideman W, Peterson RE. Toxicol Sci. 2005;86:6–19. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfi110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Delvecchio C, Tiefenbach J, Krause HM. Assay Drug Dev Techn. 2011;9:354–361. doi: 10.1089/adt.2010.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gershon MD. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2003;3:600–607. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa M, Furness JB, Cuello AC, Verhofstad AAJ, Steinbusch HWJ, Elde RP. Neuroscience. 1982;7:351–363. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(82)90272-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gershon MD, Tamir H. Neuroscience. 1981;6:2277–2286. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(81)90017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Coleman NS, Foley S, Dunlop SP, Wheatcroft J, Blackshaw E, Perkins AC, Singh G, Marsden CA, Holmes GK, Spiller RC. Clin Gastroenterol H. 2006;4:874–881. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moyana TN, Shukoor S. Modern pathology an official journal of the United States Canadian Academy of Pathology Inc. 1991;4:419–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wheeler EE, Challacombe DN. Archives of disease in childhood. 1984;59:523–527. doi: 10.1136/adc.59.6.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coates MD, Mahoney CR, Linden DR, Sampson JE, Chen J, Blaszyk H, Crowell MD, Sharkey KA, Gershon MD, Mawe GM, Moses PL. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:1657–1664. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miwa J, Echizen H, Matsueda K, Umeda N. Digestion. 2001;63:188–194. doi: 10.1159/000051888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roberts RD, Fibuch EE, Elisabeth Heal M, Seidler NW. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2007;363:77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.08.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tsunekawa S, Fukuda T, Kasuya A. J Appl Phys. 2000;87:1318–1321. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wrona MZ, Lemordant D, Lin L, Blank CL, Dryhurst G. Journal of medicinal chemistry. 1986;29:499–505. doi: 10.1021/jm00154a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sharpe E, Frasco T, Andreescu D, Andreescu S. The Analyst. 2013;138:249–262. doi: 10.1039/c2an36205h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jankovic IA, Saponjic ZV, Dzunuzovic ES, Nedeljkovic JM. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2010;5:81–88. doi: 10.1007/s11671-009-9447-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riccardi CS, Lima RC, dos Santos ML, Bueno PR, Varela JA, Longo E. Solid State Ionics. 2009;180:288–291. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bayari S, Saglam S, Ustundag HF. J Mol Struc-Theochem. 2005;726:225–232. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Dev Dynam. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kawaguchi M, Yasumasu S, Shimizu A, Sano K, Iuchi I, Nishida M. Febs J. 2010;277:4973–4987. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Inohaya K, Yasumasu S, Yasumasu I, Iuchi I, Yamagami K. Dev Growth Differ. 1999;41:557–566. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1999.00456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ozel RE, Wallace KN, Andreescu S. Anal Chim Acta. 2011;695:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2011.03.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Njagi J, Erlichman JS, Aston JW, Leiter JC, Andreescu S. Sensor Actuat B-Chem. 2010;143:673–680. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Estevez AY, Pritchard S, Harper K, Aston JW, Lynch A, Lucky JJ, Ludington JS, Chatani P, Mosenthal WP, Leiter JC, Andreescu S, Erlichman JS. Free Radical Bio Med. 2011;51:1155–1163. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim CK, Kim T, Choi IY, Soh M, Kim D, Kim YJ, Jang H, Yang HS, Kim JY, Park HK, Park SP, Park S, Yu T, Yoon BW, Lee SH, Hyeon T. Angew Chem Int Edit. 2012;51:11039–11043. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hardas SS, Sultana R, Warrier G, Dan M, Florence RL, Wu P, Grulke EA, Tseng MT, Unrine JM, Graham UM, Yokel RA, Butterfield DA. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33:1147–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peng Y, Chen X, Yi G, Gao Z. Chem Commun (Camb) 2011;47:2916–2918. doi: 10.1039/c0cc04679e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shultz MD, Reveles JU, Khanna SN, Carpenter EE. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:2482–2487. doi: 10.1021/ja0651963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.de la Garza L, Saponjic ZV, Dimitrijevic NM, Thurnauer MC, Rajh T. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:680–686. doi: 10.1021/jp054128k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Boyes WK, Chen R, Chen C, Yokel RA. Neurotoxicology. 2012;33:902–910. doi: 10.1016/j.neuro.2011.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eriksen N, Martin GM, Benditt EP. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1960;235:1662–1667. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Airhart MJ, Lee DH, Wilson TD, Miller BE, Miller MN, Skalko RG, Monaco PJ. Neurotoxicology and teratology. 2012;34:152–160. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.