Abstract

Purpose

Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors are useful in the treatment of numerous inflammatory and immunologic disorders. Since many of these conditions occur in women of childbearing age, safety during pregnancy and breastfeeding is of considerable importance.

Methods

This paper is a review of the literature on the safety of TNF inhibitors during pregnancy and breastfeeding published between 2001 and 2011.

Conclusions

TNF inhibitors do not appear to be associated with a high risk of teratogenicity or intrauterine death. However, a small magnitude increase in risk cannot be ruled out given the paucity of data on the subject. Although TNF inhibitor use may be associated with a higher rate of preterm delivery, this may in fact be due to an active, underlying disease. Therefore, the decision to use these medications should be made on a case-by-case basis. If the disease cannot be managed with first line agents, TNF inhibitors may be helpful in reducing the number of disease exacerbations. Nevertheless, when using TNF inhibitors, it is prudent to discontinue treatment around the third trimester when transfer across the placenta is greatest and to restart postpartum.

Keywords: tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, uveitis, pregnancy, breastfeeding

Introduction

Commercially available tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors (e.g., adalimumab, certolizumab, etanercept, golimumab, and infliximab) have been found to be useful in the treatment of noninfectious inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),1 rheumatoid arthritis (RA),2,3 and psoriatic arthritis (PsA).4 Their use is especially valuable in refractory disease, when first line agents have failed or caused intolerable side effects. In these cases, TNF inhibitors may be highly effective in reducing the number of disease exacerbations.1–4 For a few indications, including the management of moderate to severe RA, anti-TNF agents are also Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved as initial therapy. Given the increasing use of these drugs in managing immunologic disorders, many of which occur in women of childbearing age, safety during pregnancy is of concern. This is a review of the literature on the subject of safety of TNF inhibitors during pregnancy and breastfeeding published within the last 10 years. Particular attention is paid to adalimumab, infliximab, and etanercept, as these drugs have been the subject of the majority of published research in this area to date.

Methods

Literature Review

To accomplish as current a review of the literature as possible, we limited our search to articles published in peer-reviewed journals within the last 10 years (2001–2011). Articles were identified between September 1, 2011, and October 1, 2011, by performing a series of PubMed searches using the following Boolean search terms: “TNF inhibitors AND pregnancy,” “adalimumab AND pregnancy,” “certolizumab AND pregnancy,” “etanercept AND pregnancy,” “golimumab AND pregnancy,” “infliximab AND pregnancy” “TNF inhibitors AND breastfeeding” and “TNF inhibitors AND placental transfer.” Original studies and case presentations, which reported the use of one or more TNF inhibitors in pregnancy or during breastfeeding, including outcomes, were included in our review.

Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha and Lymphotoxin

TNF-α is an inflammatory cytokine released by many cell types, including macrophages, in the setting of an immune response. As an endogenous pyrogen, TNF-α has multiple activities that contribute to the initiation and perpetuation of inflammation. Although its role in gestation has yet to be completely elucidated, TNF-α may serve two apparently competing roles.5 On one hand, it mediates a stress response within the embryo, triggering inflammatory loss of pregnancy if the embryo sustains structural damage. On the other hand, TNF-α is also believed to play a role in protecting the embryo against toxins during development.6,7 By disrupting the protective effects of TNF-α, TNF blockers could be associated with an increased risk of congenital anomalies.

Lymphotoxin, previously known as TNF-β, exerts a similar downstream effect by binding the same receptors as TNF-α. Lymphotoxin activates neutrophils and macrophages and alters expression of vascular endothelial adhesion molecules to help mobilize inflammatory cells. Although not a principal target of TNF blockers, lymphotoxin is targeted by etanercept, a soluble form of the TNF receptor that binds and inactivates both TNF-α and TNF-β.8

TNF Inhibitors

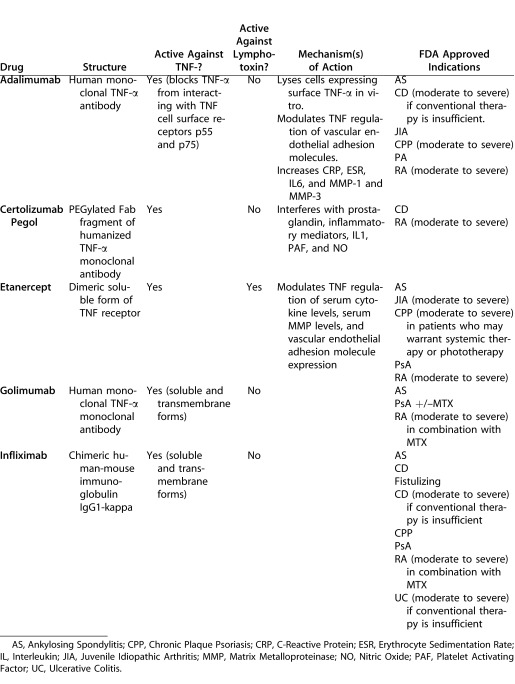

As a whole, TNF inhibitors are classified as Pregnancy Category B drugs by the FDA. According to this classification system, Category B comprises those drugs that reproductive studies in animals have failed to demonstrate risk to the fetus and that no well-controlled studies exist in pregnant women, or that reproductive studies in animals have demonstrated risk to the fetus, but that well-controlled studies in pregnant women have failed to substantiate this risk. Of note, infliximab has not been studied in animal reproductive models because this chimeric murine-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) 1 monoclonal antibody cross-reacts only with TNF-α in humans and chimpanzees. However, no embryotoxicity, teratogenicity, or maternal toxicity was detected in developmental toxicology studies performed in mice using a functionally similar antibody directed at mouse TNF-α.9 Table 1 provides a summary of the various TNF inhibitors as adapted from Micromedex Healthcare Series.8

Table 1. .

Summary of TNF Inhibitors as Adapted from Micromedex Healthcare Series (Internet Database), (Updated Periodically)

Given the obvious ethical limits to conducting a double-blind, controlled study to accurately assess the risks of the TNF blockers in pregnancy, there is a paucity of data on the safety of these drugs during pregnancy and breastfeeding. Since much of the data we have comes from case reports and case series with small sample sizes, the findings cannot be easily extrapolated. Some recent publications have presented data collected by voluntary reporting about adverse events associated with TNF inhibitors by patients and health care providers. Such methodology is confounded by recall and reporting bias, and often provides incomplete details about disease severity, comorbidities and/or concomitant medication use.

Transfer of TNF Inhibitors across the Placenta and into Breast Milk

The TNF inhibitors vary considerably in the degree that they cross the placental barrier from mother to fetus and enter breast milk during lactation. Infliximab, the most extensively studied TNF inhibitor in this regard, is a chimeric murine-human IgG1 monoclonal antibody against TNF-α. In studies designed to measure the degree of placental transfer of infliximab, drug levels in cord blood were between 2- and 3-fold higher than in maternal serum in three out of four infants from an IBD-complicated pregnancy.10

However, findings pertaining to postpartum levels of infliximab were less clear. One case report showed that infliximab levels are low, but detectable, up to 6 months postpartum in the blood of infants exposed to infliximab during pregnancy.11 Yet, in apparent conflict with these findings, another case series reported undetectable levels of infliximab in infants born to mothers treated with the drug prior to conception through approximately 30 weeks gestation.12

The detection of infliximab in neonates and the observation that placental transfer of IgG is greatest during the third trimester have led to the general recommendation that treatment with infliximab should be concluded prior to the third trimester.13 On the other hand, studies consistently show no passage of infliximab to the infant during breastfeeding as evidenced by stable serum levels in the breastfeeding infant and undetectable levels of infliximab in breast milk.11,12,14

Like infliximab, adalimumab is a monoclonal IgG1 antibody against TNF-α. However, unlike infliximab, it is a fully humanized antibody. Because of similarities in their structure, adalimumab is presumed to have a comparable degree of transfer across the placental barrier as infliximab.15 However, at this time, serum levels of adalimumab cannot be measured commercially, so data on adalimumab levels in maternal and infant serum are lacking.16 According to an assessment of the safety and efficacy of various biologic therapies used in pregnant women with Crohn's disease (CD) by the World Congress of Gastroenterology, use of adalimumab in pregnancy is challenging due to its frequent dosing schedule. Discontinuing treatment with adalimumab early in the third trimester before immunoglobulin transfer across the placenta is at its greatest is also particularly difficult without potentiating a flare. For that reason, it was recommended that adalimumab be stopped approximately 8 to 10 weeks prior to the delivery date. No safety information is available on the subject of adalimumab and lactation.16

In contrast to infliximab and adalimumab, certolizumab is a PEGylated Fab fragment of the anti–TNF-α antibody. As a result of this structural difference, certolizumab crosses the placenta slowly, through the process of diffusion rather than by active transport across a membrane receptor as occurs with whole antibodies.17 In a study performed in rats, levels of anti-TNF agent in breast milk and pup serum were lower if mothers received the Fab antibody fragment rather than whole antibody.18 These findings were supported by a report of a 22-year-old woman with IBD initiated on subcutaneous certolizumab in the second trimester, in whom maternal serum levels of certolizumab far exceeded the concentration in cord blood, suggesting minimal in utero transfer of certolizumab.19

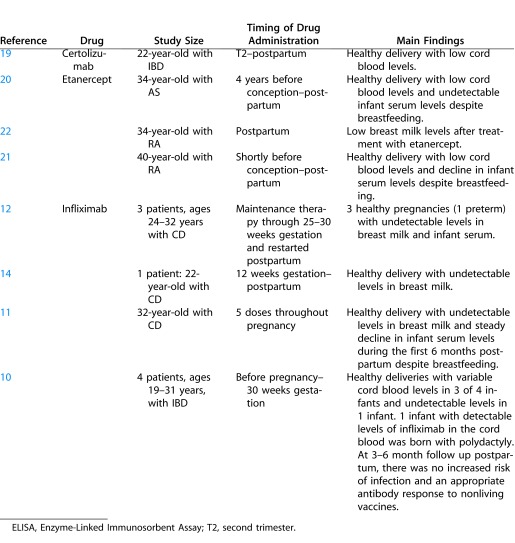

Similarly, cord blood levels of etanercept have been shown to be lower than maternal serum levels in women exposed to the drug during pregnancy.20 Although etanercept may be detected in breast milk at a low concentration, serum levels in the nursing infant were reported to decline rapidly (i.e., undetectable at 12 weeks) despite regular breastfeeding in the case of a 40-year-old woman with RA treated with etanercept, indicating that little, if any, drug passes to the infant during lactation.21 Slightly higher, but still minimal, levels of etanercept were noted in breast milk in another patient after pulsed treatment with the drug postpartum.22 See Table 2 for a summary of original papers describing the use of TNF inhibitors during breastfeeding.

Table 2. .

Original Articles on TNF Inhibitors and Breastfeeding and Transfer across the Placenta

Adverse Effects of TNF Inhibitors during Pregnancy

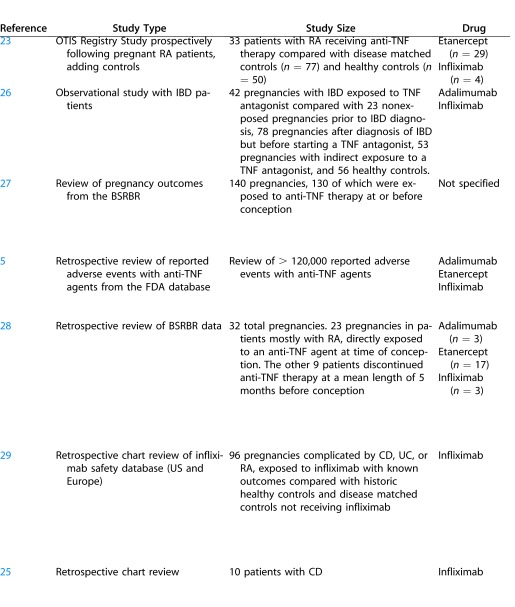

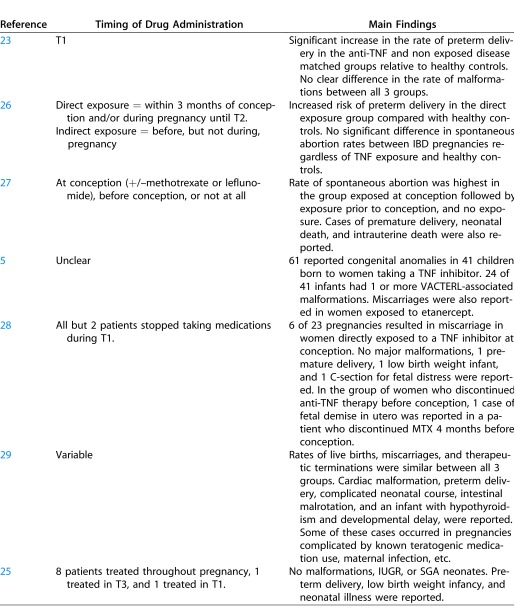

A number of studies have suggested that the use of TNF inhibitors during pregnancy is not associated with teratogenic effects. A registry study reported on pregnancy outcomes of 33 women with RA who were treated with TNF antagonists and followed prospectively during pregnancy in comparison to non exposed disease matched women and otherwise healthy women, and found no clear difference in the rate of major malformations between the three groups.23 However, neonates born to mothers in the group exposed to TNF antagonists and in the disease matched control group were significantly more likely to be born preterm. These findings have been recapitulated by an ongoing registry study by the same group, which prospectively followed pregnant women with RA treated with adalimumab adding comparison groups.24

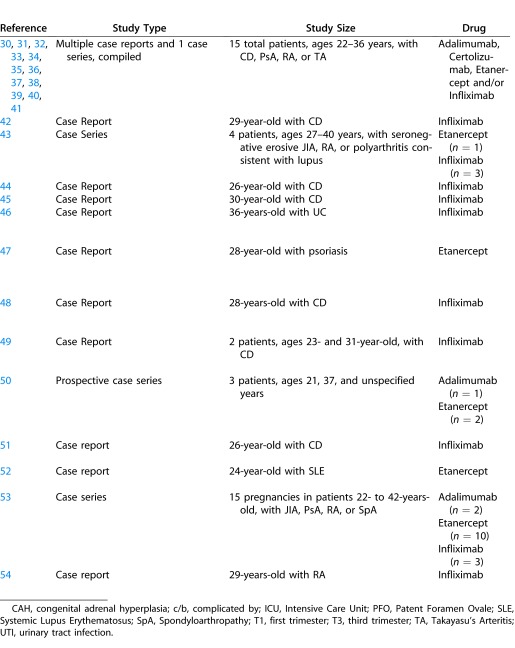

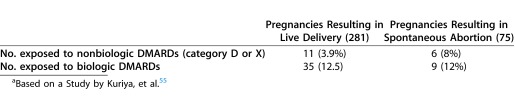

In a second study of pregnancy outcomes in 10 women treated with infliximab, all pregnancies resulted in live births without congenital malformations, intrauterine growth retardation (IUGR), or infants small for gestational age (SGA).25 While there were three preterm deliveries and two cases of neonatal illness, no association with infliximab use could be made due to concomitant use of other biologic agents in several of the women. Numerous case reports and other small case series have documented the use of anti-TNF agents during pregnancy without complication (Table 3).

Table 3. .

Original Articles and Case Presentations on the Safety of TNF Inhibitors during Pregnancy

Table 3. .

Extended

Table 3. .

Continued Extended

Table 3. .

Continued Extended

With regard to the potential abortifacient effects of TNF inhibitors, two studies suggest no significant difference in the rates of miscarriage between infliximab-exposed and infliximab-naïve women.28,29 Additionally, a recent observational study including 212 subjects implied that overall abortion rates in women treated for IBD did not differ significantly regardless of exposure history to TNF inhibitors.26 Furthermore, regardless of whether the women received anti-TNF therapy, abortion rates did not differ from rates amongst healthy controls. There was, however, an increased risk of preterm delivery in women treated with anti-TNF agents compared with healthy controls due either to the underlying disease, the use of TNF blockers, or a combination thereof.

In contrast to these reports, a recent study following outcomes of 130 pregnancies in 118 women with RA concluded that the rate of spontaneous abortion was higher in women exposed to anti-TNF therapy at conception than those exposed before conception or not at all.27 It is unclear if these findings were statistically significant.

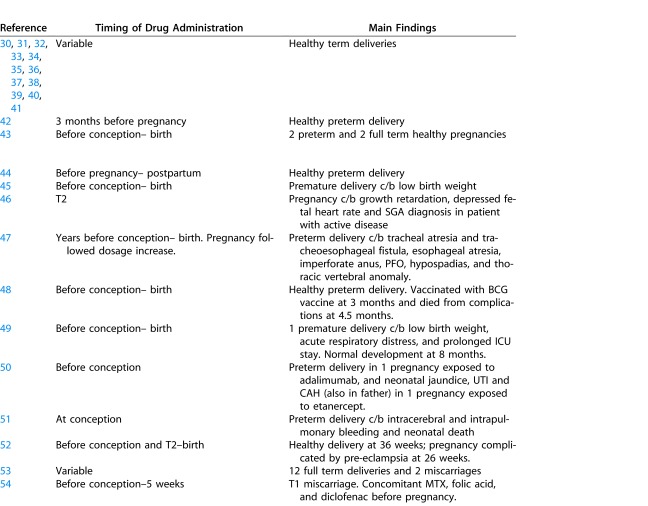

Finally, in a recent paper observing patterns of medication use in 393 pregnancies complicated with RA, 281 pregnancies ended in live births versus 75 that ended in spontaneous abortions.55 Of these 281 live births, 35 of 281 (12.5%) were exposed to biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) during pregnancy, and of the 75 spontaneous abortions, a similar proportion (9/75 [12%]) was exposed to biologic DMARDs. The disparity in exposure rate was considerably different with regard to the use of category D and X nonbiologic DMARDs in the group resulting in live delivery (3.9%) compared with the group resulting in spontaneous abortion (8%) (Table 4). Furthermore, the authors showed that use of biologic DMARDs tend to decrease over the course of the pregnancy because of a lack of data on the safety of TNF inhibitors.30

Table 4. .

Comparison of the Difference in Exposure Rate between Nonbiologic DMARDs (Category D or X) and Biologic DMARDs in Pregnancies Resulting in Live Delivery and Spontaneous Abortiona

One of the largest studies reviewed more than 120,000 adverse events reported to the US FDA between 1999 and 2005 in relation to the use of etanercept, infliximab, and adalimumab.5 Conducting a search of the database for adverse outcomes associated with pregnancy, the authors identified reports of 61 congenital anomalies in 41 children born to mothers taking a TNF inhibitor. The most common anomalies were referring to the non random grouping of congenital malformations including vertebral, anal, cardiac, tracheo-esophageal, renal, and limb defects (VACTERL). However, 41% of women were also taking concomitant medications, including methotrexate (MTX), a Pregnancy Category X drug with known teratogenic potential.

The authors acknowledged several limitations of their study. Foremost, since this database cataloged only adverse events in patients treated with a TNF blocker and was reliant on patient or provider reporting, it is unknown how many women were ultimately treated to generate this number of adverse events. Additionally, since the data relied on voluntary reporting, there was potential for reporting bias. The lack of information concerning the patients' other comorbidities was an additional limitation. Findings consistent with an increased rate of vertebral, anal, tracheo-esophageal, and renal anomalies (VATER) and VACTERL-associated defects in women treated with TNF blockers was previously reported by the same authors in a patient with psoriasis treated with etanercept.47

Complications have also been reported in the postnatal period following the use of TNF inhibitors during pregnancy. One case report describes a 28-year-old woman with IBD treated with infliximab whose infant was born without complication and, at 3 months of age, was immunized with the bacille Calmette-Guerin (BCG) vaccine. The infant died from clinically diagnosed disseminated BCG, a rare complication of the live, attenuated vaccine thought to relate to maternal use of infliximab during pregnancy, which has an unknown effect on immune system development and function in infants.48

Another publication reported on an infant born prematurely at 24 weeks gestation to a 26-year-old woman with IBD treated with infliximab, as well as azathioprine, metronidazole, and mesalamine, during pregnancy.33 The neonate developed intracerebral and intrapulmonary bleeding and died 3 days after birth. This case illustrates the difficulty in identifying potential drug side effects in the presence of concomitant medication use. Additional cases affirm the difficulty in identifying potential drug side effects when patients are taking multiple medications, some of which are known to have teratogenic effects54 or when pregnancy is complicated by an active underlying disease.46,49 Table 3 provides a summary of the key studies summarized in our review.

Conclusion

In conclusion, TNF inhibitors are risk category B drugs in pregnancy that, based on our evaluation of the available literature, do not pose high risk of teratogenicity or intrauterine death. A small magnitude increase in risk cannot be ruled out given the paucity of data on the subject. Although TNF inhibitor use may be associated with a higher rate of preterm delivery, this may in fact be due to the active underlying disease. The decision to use these drugs should, therefore, be made on a case-by-case basis, taking into account severity of disease and the potential benefits and harms of using immunomodulators versus contending with the inherent risks to the pregnancy caused by the inflammatory disease. Questions regarding activity of the disease, the potential for organ- or life-threatening complications, and available alternative medications must be addressed when a patient desires to become pregnant or has become pregnant while taking a TNF inhibitor. If the disease is quiescent or can be managed with low dose prednisone and a medication such as azathioprine or sulfasalazine, the treating physician may recommend against continuation of the anti-TNF agent. On the other hand, if the disease is active and an anti-TNF agent is the best therapeutic alternative for the patient, continuing the medication may be the best option. If TNF inhibitors are used during pregnancy, discontinuing use at the beginning of the third trimester is prudent, as transplacental transfer of IgG is greatest after this time. If treatment with TNF inhibitors must be continued in the long term, it appears safe to do so after delivery. It is important to emphasize that an assessment of the risks and benefits of these medications during pregnancy should be carefully discussed with the patient

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Douglas Jabs, Department of Ophthalmology, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, and Russell Van Gelder, Department of Ophthalmology, University of Washington, for their insights during the preparation of this manuscript.

Supported in part by an unrestricted fund from Research to Prevent Blindness (NY).

Disclosure: H. Raja, None; E.L. Matteson, None; C.J. Michet, None; J.R. Smith, None; J.S. Pulido, None

References

- 1.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the Accent I Randomised Trial. Lancet. 2002;359((9317)):1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruiz Garcia V, Jobanputra P, Burls A, et al. Certolizumab pegol (Cdp870) for rheumatoid arthritis in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(2):6. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007649.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, Singh G. Golimumab for rheumatoid arthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):6. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woolacott NF, Khadjesari ZC, Bruce IN, Riemsma RP. Etanercept and infliximab for the treatment of psoriatic arthritis: a systematic review. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006;24((5)):587–593. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carter JD, Ladhani A, Ricca LR, Valeriano J, Vasey FBA. Safety assessment of tumor necrosis factor antagonists during pregnancy: a review of the Food and Drug Administration database. J Rheumatol. 2009;36((3)):635–641. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Toder V, Fein A, Carp H, Torchinsky A. TNF-alpha in pregnancy loss and embryo maldevelopment: a mediator of detrimental stimuli or a protector of the fetoplacental unit? J Assist Reprod Genet. 2003;20((2)):73–81. doi: 10.1023/A:1021740108284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Torchinsky A, Shepshelovich J, Orenstein H, et al. TNF-alpha protects embryos exposed to developmental toxicants. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2003;49((3)):159–168. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0897.2003.01174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomson Reuters (Healthcare) Inc. Micromedex Healthcare Series. Internet Database. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomson Healthcare; Updated periodically. Accessed November 1, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centocor Ortho Biotech Inc; FDA. Malvern, PA, USA: 2011. Remicade Lyophilized Concentrate for Intravenous Injection, Infliximab Lyophilized Concentrate for Intravenous Injection. In. ed. Available at: http://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2011/103772s5281lbl.pdf; http://google2.fda.gov/search?q=infliximab+prescribing+information&client=FDAgov&site=FDAgov&lr=&proxystylesheet=FDAgov&output=xml_no_dtd&getfields; http://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/archives/fdaDrugInfo.cfm?archiveid=19410. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zelinkova Z, de Haar C, de Ridder L, et al. High intra-uterine exposure to infliximab following maternal anti-TNF treatment during pregnancy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33((9)):1053–1058. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2011.04617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vasiliauskas EA, Church JA, Silverman N, et al. Case report: evidence for transplacental transfer of maternally administered infliximab to the newborn. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4((10)):1255–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kane S, Ford J, Cohen R, Wagner C. Absence of infliximab in infants and breast milk from nursing mothers receiving therapy for Crohn's disease before and after delivery. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43((7)):613–616. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31817f9367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Donnell S, O'Morain C. Review article: use of antitumour necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease during pregnancy and conception. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2008;27((10)):885–894. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2008.03648.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stengel JZ, Arnold HL. Is infliximab safe to use while breastfeeding? World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14((19)):3085–3087. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Successful use of infliximab for perianal Crohn's disease in pregnancy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17((3)):868–869. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahadevan U, Cucchiara S, Hyams JS, et al. The London Position Statement of the World Congress of Gastroenterology on Biological Therapy for IBD with the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation: pregnancy and pediatrics. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;2((106)):214–223. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.464. quiz 224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Transplacental transfer of immunosuppressants and biologics used for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Curr Pharm Biotechnol. 2011;12((5)):765–773. doi: 10.2174/138920111795470903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stephens P, Nesbitt A, Foulkes R. Placental transfer of the anti-TNF antibody TN3 in rats: comparison of immunoglobulin G1 and pegylated Fab versions. Gut. 2006;5(Suppl):A8. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahadevan U, Abreu MT. 960 certolizumab use in pregnancy: low levels detected in cord blood. Gastroenterology. 2009;5((136)):A–146. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berthelsen BG, Fjeldsoe-Nielsen H, Nielsen CT, Hellmuth E. Etanercept concentrations in maternal serum, umbilical cord serum, breast milk and child serum during breastfeeding. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49((11)):2225–2227. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Murashima A, Watanabe N, Ozawa N, Saito H, Yamaguchi K. Etanercept during pregnancy and lactation in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis: drug levels in maternal serum, cord blood, breast milk and the infant's serum. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68((11)):1793–1794. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.105924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Keeling S, Wolbink GJ. Measuring multiple etanercept levels in the breast milk of a nursing mother with rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 2010;37((7)):1551. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.100077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chambers CD, Johnson D, Jones KL. Safety of anti–TNF-α medications in pregnancy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;(3);(52):P196. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson DL, Jones KL, Chambers C. Pregnancy Outcomes in Women Exposed to Adalimumab: Otis Autoimmune Diseases in Pregnancy Project [Abstract] Arthritis Rheum. 2008;(58):S682. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mahadevan U, Kane S, Sandborn WJ, et al. Intentional infliximab use during pregnancy for induction or maintenance of remission in Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21((6)):733–738. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, et al. Outcome of pregnancy in women with inflammatory bowel disease treated with antitumor necrosis factor therapy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17((9)):1846–1854. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Verstappen SM, King Y, Watson KD, Symmons DP, Hyrich KL. Anti-TNF therapies and pregnancy: outcome of 130 pregnancies in the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register. Ann Rheum Dis. 2011;70((5)):823–826. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.140822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hyrich KL, Symmons DP, Watson KD, Silman AJ. Pregnancy outcome in women who were exposed to anti-tumor necrosis factor agents: results from a national population register. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54((8)):2701–2702. doi: 10.1002/art.22028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Katz JA, Antoni C, Keenan GF, et al. Outcome of pregnancy in women receiving infliximab for the treatment of Crohn's disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99((12)):2385–2392. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Angelucci E, Cocco A, Viscido A, Caprilli R. Safe use of infliximab for the treatment of fistulizing Crohn's disease during pregnancy within 3 months of conception. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008;14((3)):435–436. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coburn LA, Wise PE, Schwartz DA. The successful use of adalimumab to treat active Crohn's disease of an ileoanal pouch during pregnancy. Dig Dis Sci. 2006;51((11)):2045–2047. doi: 10.1007/s10620-006-9452-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dessinioti C, Stefanaki I, Stratigos AJ, et al. Pregnancy during adalimumab use for Psoriasis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25((6)):738–739. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03756.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jurgens M, Brand S, Filik L, et al. Safety of adalimumab in Crohn's disease during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16((10)):1634–1636. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kraemer B, Abele H, Hahn M, et al. A successful pregnancy in a patient with Takayasu's arteritis. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2008;27((3)):247–252. doi: 10.1080/10641950801955741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mishkin DS, Van Deinse W, Becker JM, Farraye FA. Successful use of adalimumab (Humira) for Crohn's disease in pregnancy. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2006;12((8)):827–828. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200608000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oussalah A, Bigard MA, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Certolizumab use in pregnancy. Gut. 2009;(4);(58):608. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.166884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Puig L, Barco D, Alomar A. Treatment of psoriasis with anti-Tnf drugs during pregnancy: case report and review of the literature. Dermatology. 2010;220((1)):71–76. doi: 10.1159/000262284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scioscia C, Scioscia M, Anelli MG, et al. Intentional etanercept use during pregnancy for maintenance of remission in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2011;29((1)):93–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sinha A, Patient C. Rheumatoid arthritis in pregnancy: successful outcome with anti-TNF agent (Etanercept) J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;26((7)):689–691. doi: 10.1080/01443610600930647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Umeda N, Ito S, Hayashi T, et al. A patient with rheumatoid arthritis who had a normal delivery under etanercept treatment. Intern Med. 2010;49((2)):187–189. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Vesga L, Terdiman JP, Mahadevan U. Adalimumab use in pregnancy. Gut. 2005;(6);(54):890. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.065417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Burt MJ, Frizelle FA, Barbezat GO. Pregnancy and exposure to infliximab (anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha monoclonal antibody) J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;18((4)):465–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2003.02983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosner I, Haddad A, Boulman N, et al. Pregnancy in rheumatology patients exposed to anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;(9);(46):1508. 1508–1509. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kem068. ; author reply. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tursi A. Effect of intentional infliximab use throughout pregnancy in inducing and maintaining remission in Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2006;38((6)):439–440. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2006.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Angelucci E, Cesarini M, Vernia P. Inadvertent conception curing concomitant treatment with infliximab and methotrexate in a patient with Crohn's disease: is the game worth the candle? Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16((10)):1641–1642. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aratari A, Margagnoni G, Koch M, Papi C. Intentional infliximab use during pregnancy for severe steroid-refractory ulcerative colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2011;(3);(5):262. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carter JD, Valeriano J, Vasey FB. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibition and VATER association: a causal relationship. J Rheumatol. 2006;33((5)):1014–1017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cheent K, Nolan J, Shariq S, et al. Case report: fatal fase of fisseminated BCG infection in an infant born to a mother taking infliximab for Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4((5)):603–605. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Correia LM, Bonilha DQ, Ramos JD, Ambrogini O, Miszputen SJ. Inflammatory bowel disease and pregnancy: report of two cases treated with infliximab and a review of the literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;22((10)):1260–1264. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328329543a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Roux CH, Brocq O, Breuil V, Albert C, Euller-Ziegler L. Pregnancy in rheumatology patients exposed to anti-tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha therapy. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2007;46((4)):695–698. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kel400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Srinivasan R. Infliximab treatment and pregnancy outcome in active Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96((7)):2274–2275. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Micheloud D, Nuno L, Rodriguez-Mahou M, et al. Efficacy and safety of Etanercept, high-dose intravenous gammaglobulin and plasmapheresis combined therapy for lupus diffuse proliferative nephritis complicating pregnancy. Lupus. 2006;15((12)):881–885. doi: 10.1177/0961203306070970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Berthelot JM, De Bandt M, Goupille P, et al. Exposition to anti-TNF drugs during pregnancy: outcome of 15 cases and review of the literature. Joint Bone Spine. 2009;76((1)):28–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2008.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kinder AJ, Edwards J, Samanta A, Nichol F. Pregnancy in a rheumatoid arthritis patient on infliximab and methotrexate. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43((9)):1195–1196. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keh264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuriya B, Hernandez-Diaz S, Liu J, et al. Patterns of medication use during pregnancy in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63((5)):721–728. doi: 10.1002/acr.20422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]