Abstract

Purpose

This study aimed to highlight structural corneal changes in a model of type 2 diabetes, using in vivo corneal confocal microscopy (CCM). The abnormalities were also characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and second harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy in rat and human corneas.

Methods

Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rats were observed at age 12 weeks (n = 3) and 1 year (n = 6), and compared to age-matched controls. After in vivo CCM examination, TEM and SHG microscopy were used to characterize the ultrastructure and the three-dimensional organization of the abnormalities. Human corneas from diabetic (n = 3) and nondiabetic (n = 3) patients were also included in the study.

Results

In the basal epithelium of GK rats, CCM revealed focal hyper-reflective areas, and histology showed proliferative cells with irregular basement membrane. In the anterior stroma, extracellular matrix modifications were detected by CCM and confirmed in histology. In the Descemet's membrane periphery of all the diabetic corneas, hyper-reflective deposits were highlighted using CCM and characterized as long-spacing collagen fibrils by TEM. SHG microscopy revealed these deposits with high contrast, allowing specific detection in diabetic human and rat corneas without preparation and characterization of their three-dimensional organization.

Conclusion

Pathologic findings were observed early in the development of diabetes in GK rats. Similar abnormalities have been found in corneas from diabetic patients.

Translational Relevance

This multidisciplinary study highlights diabetes-induced corneal abnormalities in an animal model, but also in diabetic donors. This could constitute a potential early marker for diagnosis of hyperglycemia-induced tissue changes.

Keywords: diabetes, corneas, confocal microscopy, multiphoton microscopy, electron microscopy

Introduction

Chronic hyperglycemia resulting from poorly controlled diabetes leads to tissue modifications that are mainly induced by the reactive oxygen species-activated pathways.1 These molecular mechanisms precede, sometimes by years, clinically detectable complications of diabetes. Among these complications, diabetic retinopathy, which is a major cause of vision loss in the western population, is detected earliest by retinal microangiopathy. However, alterations of retinal functions have been shown to precede the first clinically detected signs of retinopathy.2 Obviously, any simple means of earlier diagnosis of hyperglycemia-induced tissue changes could help design new preventive treatments and protocols for eye care of diabetic patients, notably in order to define at-risk patients and to anticipate retinal deterioration. For this purpose, as diabetes is associated with a number of structural changes in the cornea, this transparent and easily accessible ocular tissue could provide a window to detect the earliest hyperglycemia-induced abnormalities.

For 20 years, as a result of the development of microscopic imaging systems such as transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and corneal confocal microscopy (CCM), and of the optimization of immunohistochemistry methods, hyperglycemia-induced modifications have been described in corneas of diabetic organisms, in both rat models and human beings. At the epithelium level, focal epithelial cell degeneration and morphologic alterations of the extracellular matrix,3–5 alteration of the epithelial barrier function,6,7 delay of corneal epithelial wound healing8,9 and non-enzymatic glycation of proteins by advanced glycation end-products (AGEs)10–14 have been reported. TEM observations have also highlighted the presence of unusual long-spacing collagen fibril aggregates among both stromal matrix and Descemet's membrane (DM) of corneas from diabetic patients5 and in the DM of diabetic rat models.15,16 Finally, diabetes may compromise the stromal hydration through a decrease in endothelial cell density17,18 and change in cell morphology.19,20 Taken all together these studies suggest that diabetes accelerates age-related molecular processes.

In this context, this study aimed to characterize corneal structural changes in a spontaneous rat model of type 2 diabetes and in human corneas from diabetic donors. For this purpose, three complementary imaging techniques were combined because they allowed imaging corneal structures with different contrast modes and scales. Observation of the abnormalities by in vivo CCM was complemented by histologic analysis, TEM, and second harmonic generation (SHG) microscopy. The last-mentioned technique is an emerging multiphoton method that reveals unstained collagen fibrils with unequalled contrast and specificity, so allows determining the spatial organization of fibrillar collagen structures with micrometric resolution.21–28 SHG microscopy was performed in intact ex vivo corneas. Histology and TEM were used in fixed, stained, and sliced tissues as gold standard methods with complementary resolutions in order to characterize the abnormal corneal ultrastructures.

In this study, we first highlighted structural changes in all the layers of the Goto-Kakizaki (GK) rat corneas using CCM and histology, mainly, structural abnormalities at the epithelium-stroma interface, signs of endothelial cells stress, and deposits of long-spacing fibrillar collagen in the DM. We then focused on the abnormal deposits highlighted in the DM using all the complementary microscopic methods. SHG microscopy notably allowed their specific detection in the corneas from GK rats but also from human diabetic donors. These findings will be presented in the following, and discussed in relationship to pathologic processes during diabetes.

Materials and Methods

Animals

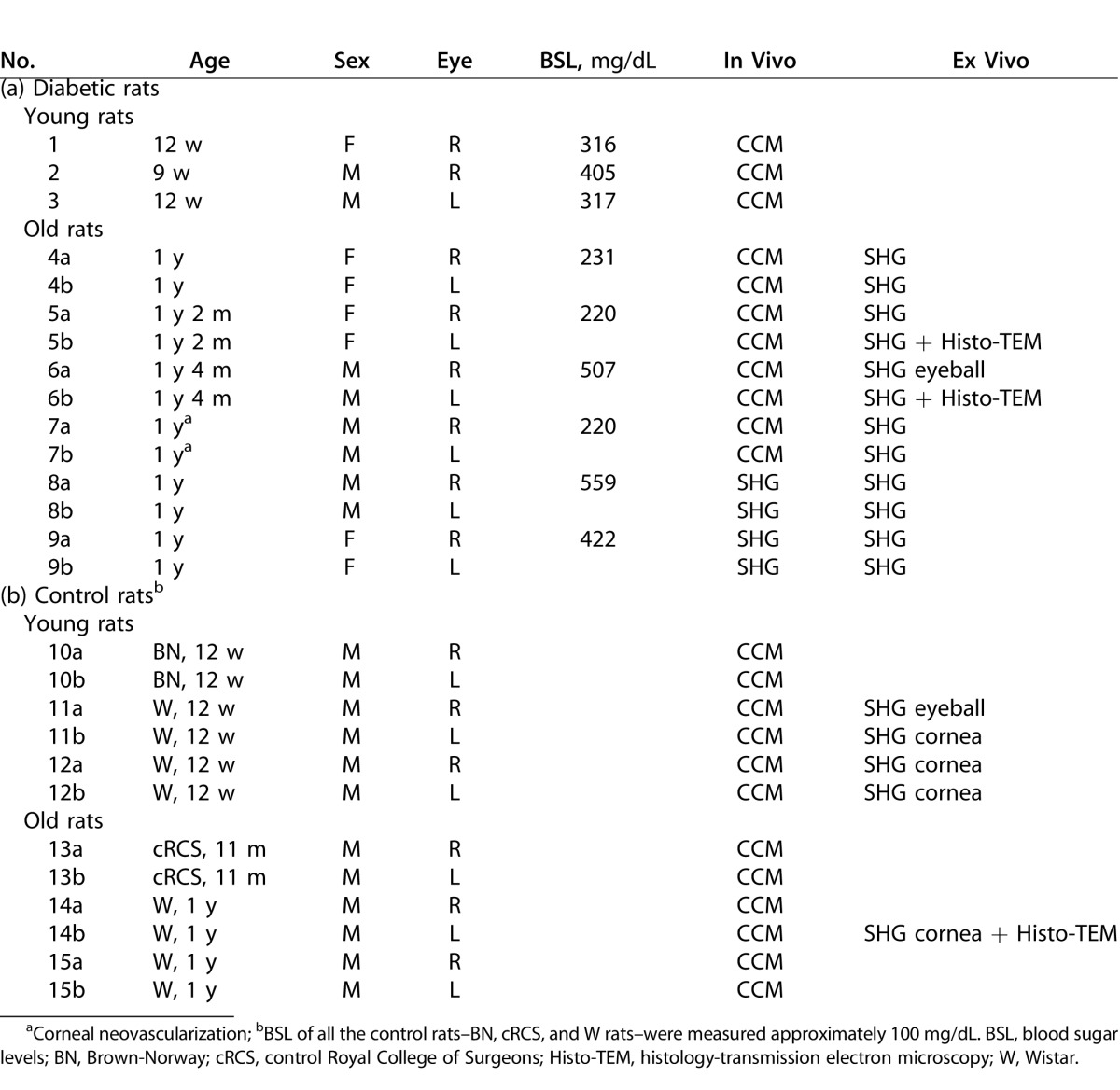

All animals were treated in accordance with the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Twelve-week-old (n = 3) and 1-year-old (n = 6) GK rats that spontaneously developed diabetes mellitus, from our facilities, were included and compared to age-matched nondiabetic rats from our facilities or purchased (Janvier; Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France) and roomed for 1 week before inclusion in the study. Rat data and performed analysis are given in Table 1.

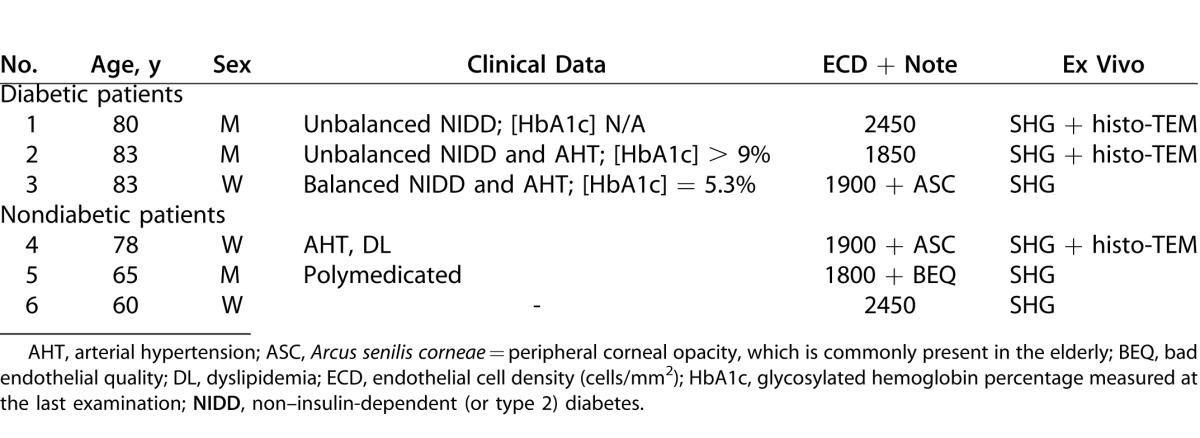

Table 1. .

Diabetic (a) and Control (b) Rats Data, Including Corneal In Vivo and Ex Vivo Analysis Performed

Human Corneas

We obtained six human corneas assigned to scientific use,29 from an eye bank association (Banque Française des Yeux; Paris, France). Human corneas were used under informed consent of the relatives, according to French bioethics laws. The study was conducted according to the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki for biomedical research involving human corneas. Mean donor age was 75 years (3 women, 3 men; age range, 60–83 years). As described in Table 2, three nondiabetic patients and three patients with type 2 diabetes were included. Corneas were excised with 16- to 18-mm-diameter trephination, and immediately stored in 100 mL organ culture medium (CorneaMax; Eurobio, Courtabœuf, France) at 31°C in a dry incubator until the experiment, at least 2 weeks later. Due to this storage, all corneas from both diabetic and nondiabetic donors were slightly edematous as demonstrated by their increased thickness (typically 700 to 900 μm) compared to physiologic corneal thickness (approximately 500 μm).

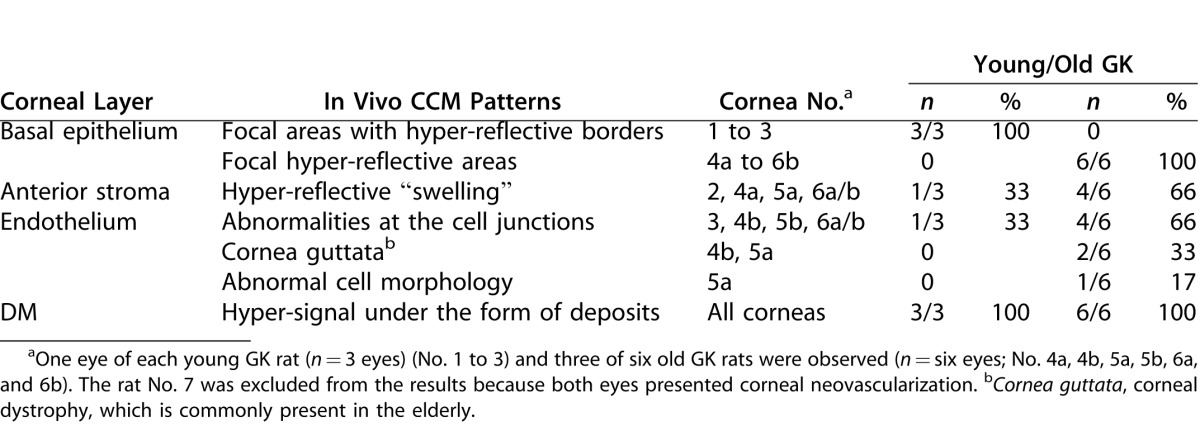

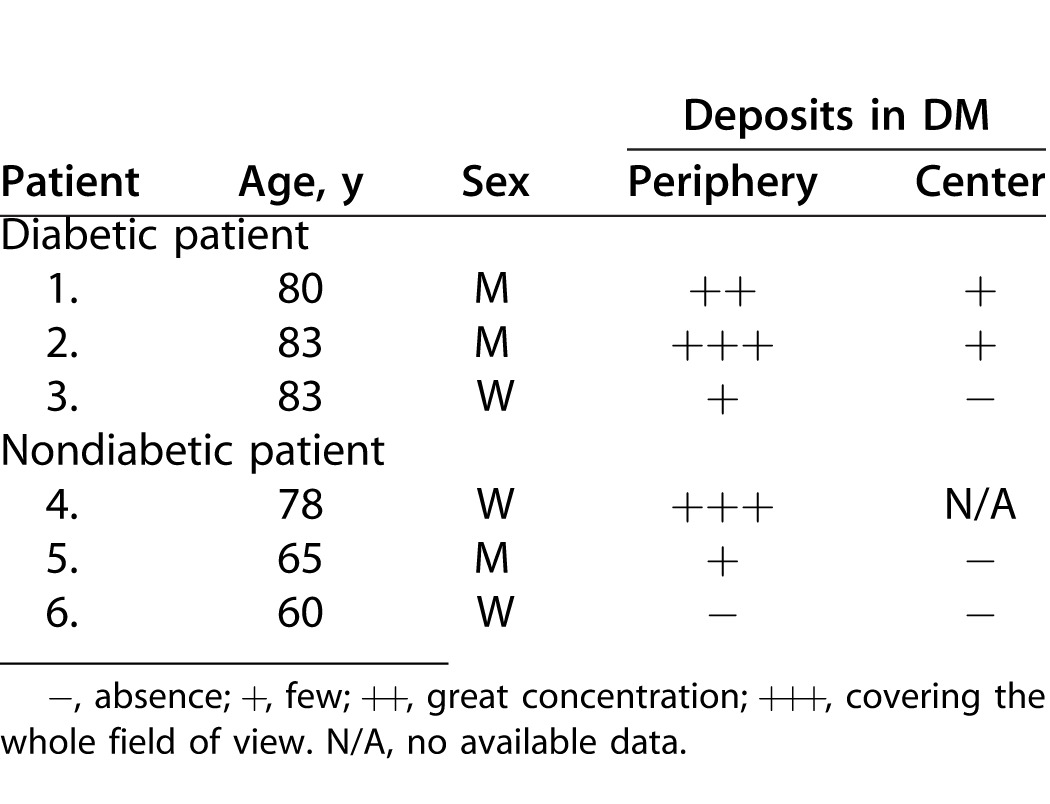

Table 2. .

Clinical Data Concerning Human Donors, Including the Corneal Ex Vivo Analysis Performed

In Vivo Corneal Confocal Microscopy

A confocal laser scanning system (Heidelberg Retina Tomograph II with Rostock Cornea Module [HRT II]; Heidelberg Engineering GmbH, Heidelberg, Germany) was used to examine the rat corneas as previously described.30 Before in vivo CCM examination, rats were anesthetized with a mixture of 50 mg/kg ketamine chlorhydrate (Kétamine 1000, Virbac; Carros, France) and 5 mg/kg xylasine (Rompun 2%, Bayer HealthCare AG; Puteaux, France), positioned on a special stage and immobilized to align the central cornea parallel to the objective front lens. A drop of gel tear substitute (Lacrigel, carbomer 0.2%; Europhta, Monaco, Principauté de Monaco) was placed on the objective front lens to maintain immersion contact between the objective and the cornea and to avoid corneal drying. To allow examination, the HRT II camera (Heidelberg Engineering GmbH) was disconnected from the headrest and maintained vertically. The laser source consisted of a 670 nm laser diode. The objective was an objective at x60 magnification and 0.90 numerical aperture (NA), covered by a polymethyl methacrylate cap. Images consisted of 384 × 384 pixels covering an area of 400 × 400 μm, which approximately corresponds to 1 μm/pixel with a pixel acquisition time of 0.024 seconds. Images were acquired using an automatic-gain mode. The x-y position and the depth of the optical section were controlled manually; the focus position in depth was automatically calculated by the microscope software.

Ex Vivo SHG Microscopy

The corneas of the oldest rats included in the study were examined using a custom-built laser scanning multiphoton microscope, as previously described,27,28 with detection of SHG signals. Excitation was performed using a titanium-sapphire laser (Tsunami; Spectra Physics, Newport Corporation, Irvine, CA). The setup incorporated detection channels in forward and backward directions with photon-counting modules (P25PC photomultiplier tubes; ET Enterprises Ltd, Uxbridge, UK).

For ex vivo imaging, the rat corneas were placed in Hanks medium immediately after their removal. All the corneas were flat mounted as follows: the buttons were gently transferred onto a first coverslip, three small incisions were cut at the periphery under operating binocular microscope in order to flatten the cornea curvature, and a drop of Hanks medium was added before putting the second coverslip. The coverslips were maintained in a custom-built sample holder adapted to the microscope stage. SHG imaging was performed at 860-nm excitation with circular incident polarization. Forward and backward SHG signals from collagen fibrils were detected at one-half the incident excitation wavelength with well-suited filters (FF01-427/10 interferential filter and 680SP rejection filters; Semrock, Lake Forest, IL). Large-scale images were generated using a water-immersion 20x, 0.95 NA objective (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) with typically 2 μm axial × 0.4 μm lateral resolutions. High-resolution images were recorded using a water-immersion 60x,1.2 NA objective (Olympus) with 1 μm axial × 0.3 μm lateral resolutions. Image stacks were recorded with 0.5 to 1 μm lateral pixel size, and 0.5 to 2 μm axial steps. Laser power at the objective focus was typically 20 to 85 mW. Acquisition time was 3 to 5 μs per pixel (i.e., typically approximately 1 second for a 512 × 512 pixel image).

Ex vivo imaging of intact rat eyeballs was also performed using SHG. Just after enucleation, the examined eye was mounted in a molded agarose gel. Optical contact between the cornea and the immersion objective was maintained with a gel tear substitute (Lacrigel) and only backward SHG signals could be detected as in in vivo configuration.

Histology and Transmission Electron Microscopy

The corneas were fixed with 2.5% glutaraldehyde in cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and with 1% osmium tetroxyde in cacodylate buffer (0.2 M), and then subjected to successive dehydration in graduated ethanol solution (50, 70, 95, and 100%) and in propylene oxide. Each area of interest was separately included in epoxy resin and oriented. Semi-thin sections (1 μm) were obtained with an ultra microtome (OmU2; Reichert, Austria) and stained with toluidine blue. Ultra-thin sections (100 nm) were contrasted by uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and analyzed with a transmission electron microscope (TEM CM10, Philips; Eindhoven, The Netherlands) coupled with a CCD camera (ES1000W Erlangshen; Gatan, Évry, France).

Results

In Vivo Corneal Confocal Microscopy in Nondiabetic Rats

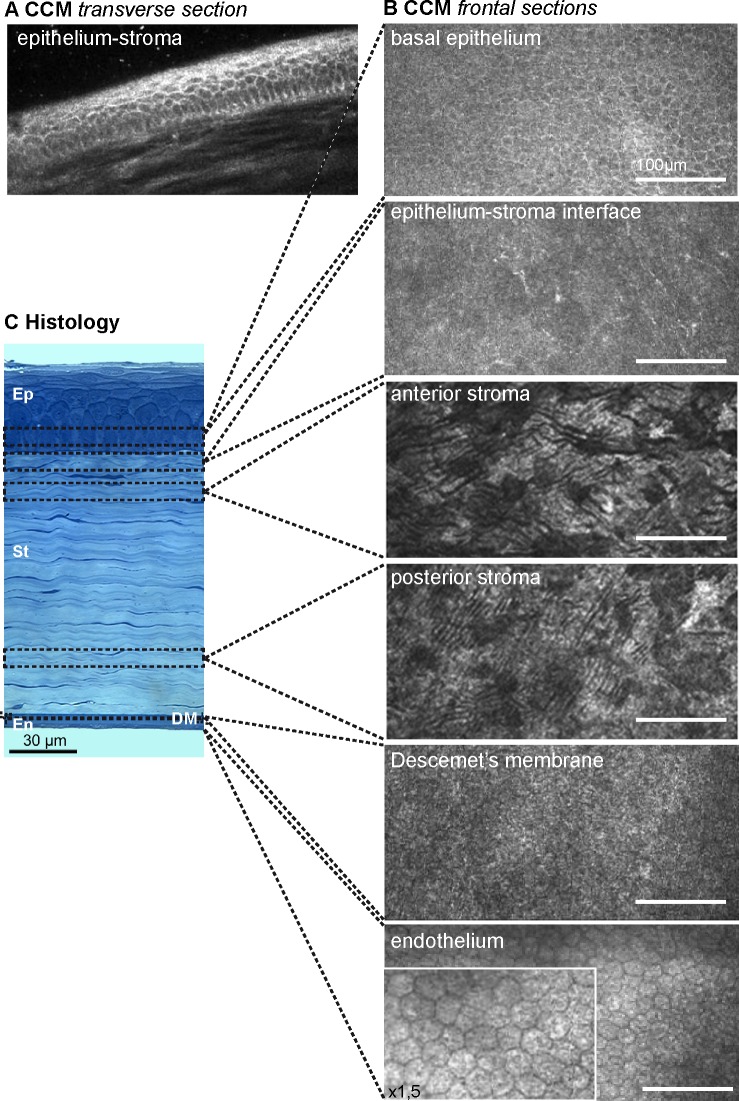

Figure 1 illustrates a non-diabetic rat cornea observed by CCM examinations, showing the light-scattering interfaces. In the transverse section (Fig. 1A), the epithelium presented a healthy structure composed of distinct epithelial layers with regular basal cells and thin superficial cells. Frontal sections (Fig. 1B) were generated in each corneal layer. The basal epithelium cells were visualized through the detection of the junctions between their lipid-rich membranes and their cytoplasm. Whereas Bowman's layer did not appear on histologic sections in the rats (Fig. 1C), in vivo CCM examination allowed the detection of an amorphous membrane with fine nerve plexi (Fig. 1B). In the stroma, CCM allowed the detection of the keratocytes. In the posterior cornea, the DM appeared amorphous and the hexagonal endothelial cells, with a 20 μm regular diameter, exhibited a honeycomb pattern.

Figure 1. .

In vivo corneal confocal microscopy and histology in the normal rat cornea. (A) Transverse section of the epithelium-stroma interface, and (B) frontal sections of all the corneal layers generated by in vivo CCM. (C) Semi-thin transverse section stained with toluidine blue, illustrating the different corneal layers visualized by CCM. En, endothelium; Ep, epithelium; St, stroma.

Epithelium and Anterior Stroma of Diabetic Corneas

During CCM examinations of the diabetic GK rats, abnormalities of reflectance were observed as early as 3 months of age. Main in vivo CCM patterns are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3. .

Main In Vivo Confocal Microscopy Patterns Observed in Corneas from Diabetic Rats

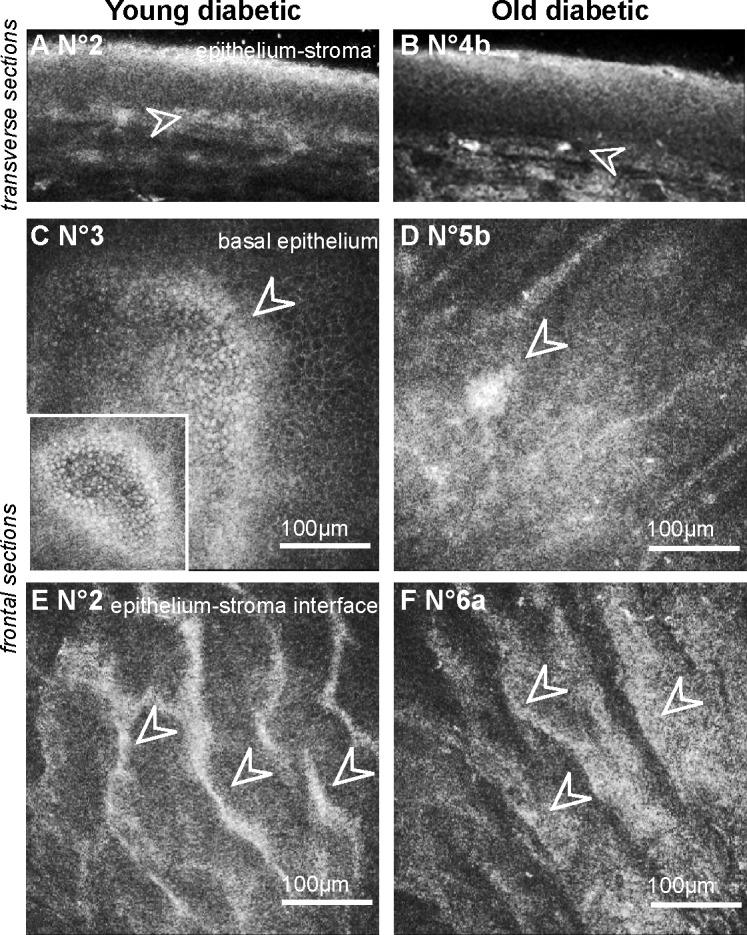

In young as in old diabetic rats, hypersignals at the interface between the epithelium and the anterior stroma faded the normal signals from epithelial cell junctions in the transverse sections (Figs. 2A–B). In all the youngest GK rats' corneas (n = 3/3), the frontal sections revealed an irregular basal epithelium with focal areas composed of cells without distinct junctions and adjacent hyper-reflective borders (Fig. 2C). In the oldest diabetic rats' corneas (n = 6/6), focal hyper-reflective areas (Fig. 2D) were also detected at this level. At the Bowman's layer level, in young (n = 1/3) (Fig. 2E) as well as in old diabetic rats (n = 4/6) (Fig. 2F), hyper-reflective “swelling” was highlighted in corneal peripheries.

Figure 2. .

Corneal changes at the “epithelium-anterior stroma” level in GK rat corneas highlighted by in vivo CCM. (A–B) Transverse images of the epithelium showing hypersignal and infiltrating cells (white arrowheads) in the corneas of young (A) as old (B) GK rats. (C–D) Frontal images of the basal epithelium, demonstrating focal hyper-reflective areas in diabetic corneas (white arrowheads). (E–F) Frontal images at the epithelium-stroma interface highlighting a hyper-reflective “swelling” in the diabetic corneas (white arrowheads). Scale bar, 100 μm.

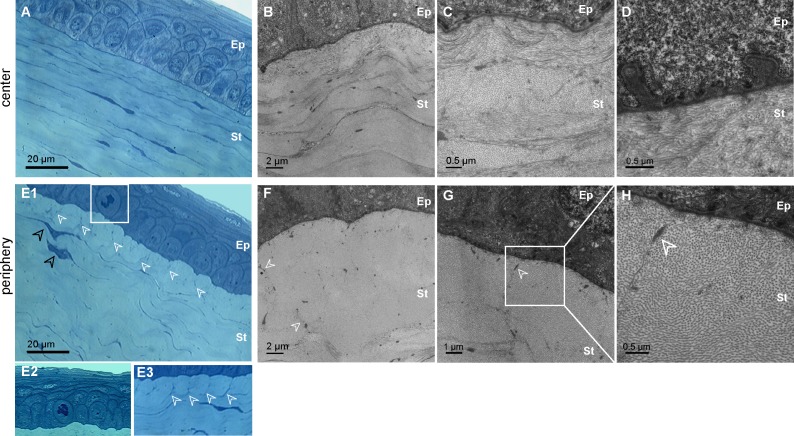

On histology, proliferative epithelial basal cells (Figs. 3E1–E2) were observed in the diabetic cases and the abnormal epithelium-stroma interface was confirmed. Whereas the center of the diabetic corneas demonstrated normal corneal histology at this level (Fig. 3A), changes in extracellular matrix organization were detected in corneal peripheries around activated keratocytes (Figs. 3E1–3E3). These keratocytes exhibit a bigger blue-stained intracellular compartment than the normal cells with elongated and thin nuclei (see Fig. S1 (3.2MB, tif) ). TEM confirmed that the anterior stroma matrix was organized differently in the center than in the periphery of diabetic corneas. In the corneal center, although the epithelial basal lamina appeared thickened with numerous invaginations (Fig. 3D) as already reported,4,5 collagen lamellae were normal (Figs. 3B–3C), similar to the lamellar organization in normal corneas. On the contrary, in the periphery of the diabetic corneas, the anterior lamellar structures showed abnormally tile-shaped accumulation of collagen fibrils with homogeneous diameter, surrounded by micro-fibrils and in contact with the basal lamina (Figs. 3F–3H, white arrowheads).

Figure 3. .

Histology of the “epithelium-anterior stroma” interface in GK rat cornea. (A–D) Corneal center of the diabetic corneas No. 5b (A–C) and No. 6b (D). Semi-thin transverse sections stained with toluidine blue (A) and TEM on ultrathin sections (B–D) illustrate the normal collagen matrix organization (B–C) but also abnormal basal lamina (D). (E–H) Corneal periphery of the diabetic corneas No. 5b (E1–E3, F) and No. 6b (E2, G–H). Semi-thin transverse sections stained with toluidine blue (E) illustrate observed proliferative basal epithelial cell (E1–E2) and changes in extracellular matrix organization (E1–E3, white arrowhead) near activated keratocytes (E1, black arrowhead). TEM on ultrathin sections (F–H) show abnormal tile-shaped accumulation of collagen fibrils, surrounding by micro-fibrils (white arrowhead). Ep, epithelium; St, stroma.

In human corneas from diabetic donors, histology of the anterior corneal layers demonstrated similar alterations of the epithelial basement membrane, but no change was detected in the extracellular matrix organization (not shown).

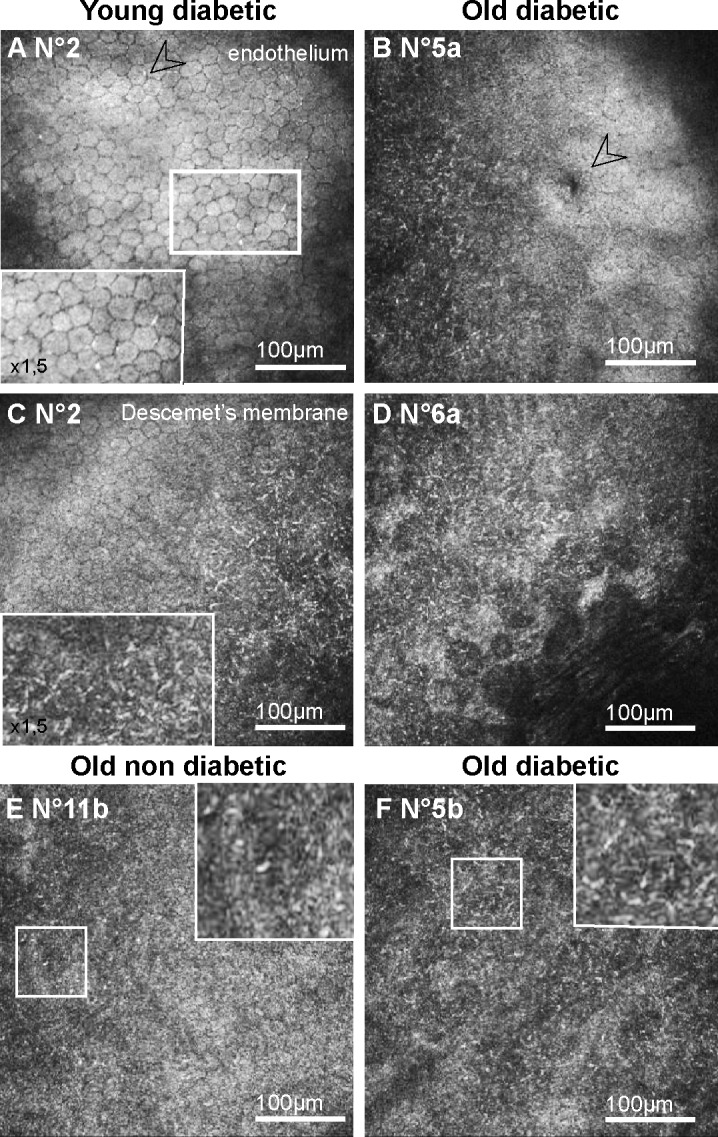

Endothelium and Descemet's Membrane of Diabetic Corneas

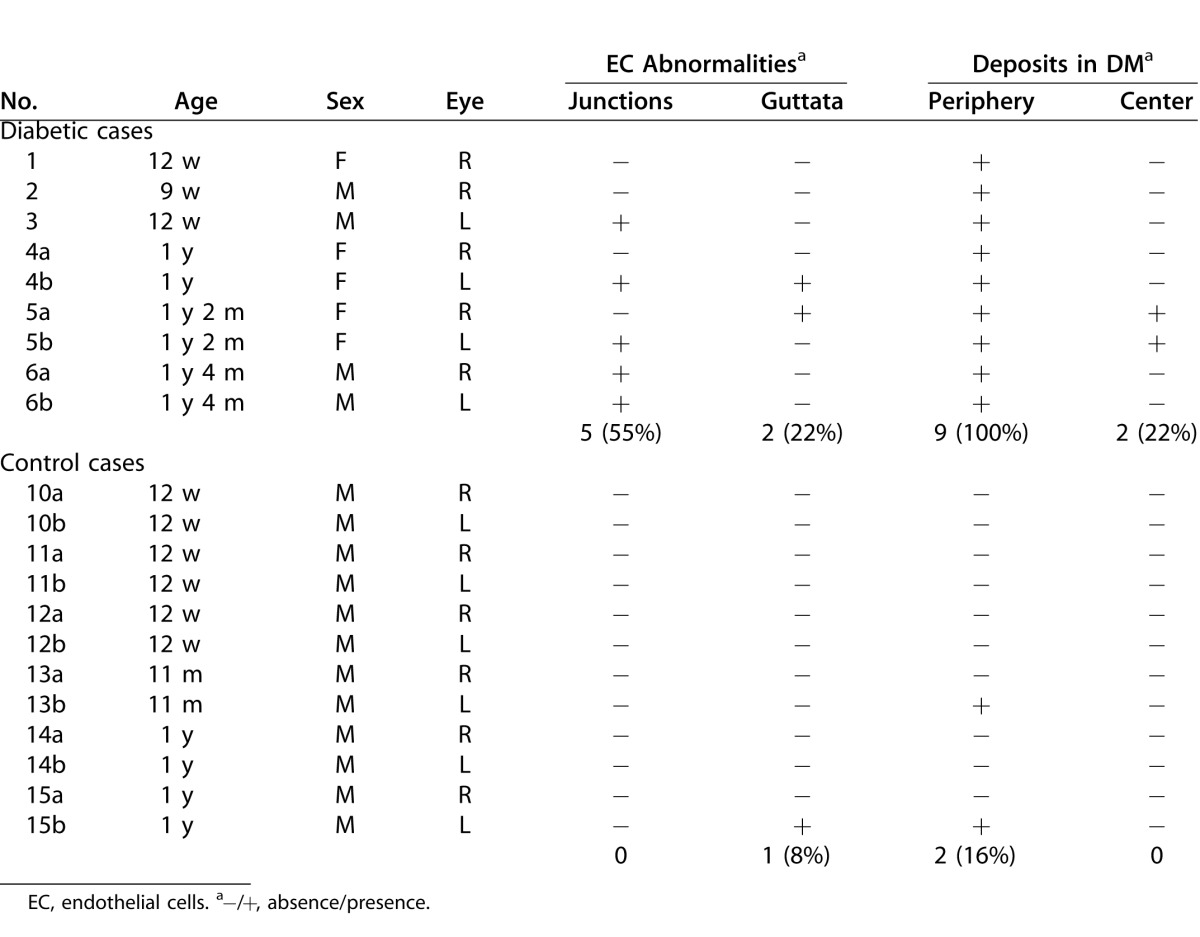

During CCM examination of the GK rats, abnormalities were detected in all the observed corneas, in both the endothelium and the DM (Table 4). Regarding the endothelium, different signs of cell stresses were highlighted. Hyper-reflective patterns were observed at the endothelial cell junctions as early as 3 months of age (n = 1/3) (Fig. 4A) and in the oldest GK rats (n = 4/6) in which other stress signs included endothelial dystrophy (n = 2/6) (Fig. 4B) and abnormal cell morphology (n = 1/6). Just above the endothelial cells, sparse hyper-reflective and rod-shaped structures were detected with high density in the DM periphery of the youngest (n = 3/3) (Fig. 4C) as in the oldest GK rats (n = 6/6) (Fig. 4D). In both corneas from one rat, these rod-shaped structures were detected in the entire DM surface. The same hyper-reflective bodies were also observed with a lesser extent in periphery of two corneas from old control rats (n = 2/6) (Fig. 4E).

Table 4. .

Main In Vivo CCM Findings in the Posterior Part of All the Rat Corneas

Figure 4. .

Corneal changes in the posterior corneas of GK rats highlighted by in vivo CCM. (A–B) Frontal images of the endothelium, demonstrating signs of endothelial cell stresses, as hyper-reflective junctions in young GK rats (A) and cornea guttata (B) in old GK rats. (C–F) Frontal images of the DM, showing hyper-reflective dense deposits in corneal peripheries from both young (C) and old (D, F) GK rats. In old nondiabetic control rat, DM images showed no or sparse (E) hyper-reflective deposits. Scale bar, 100 μm.

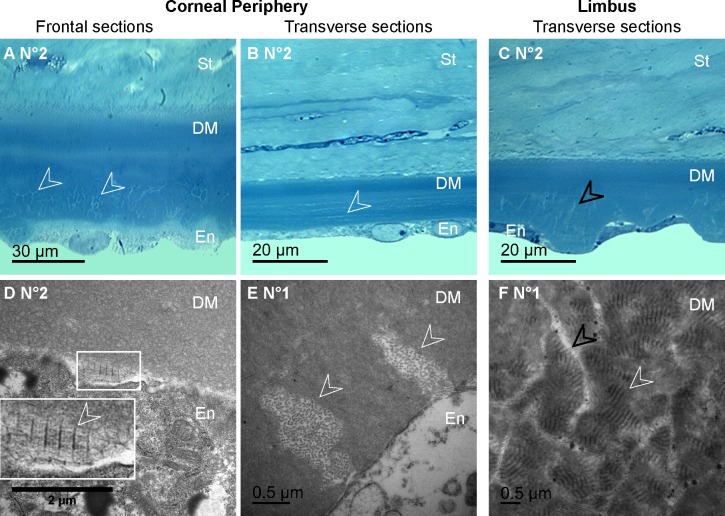

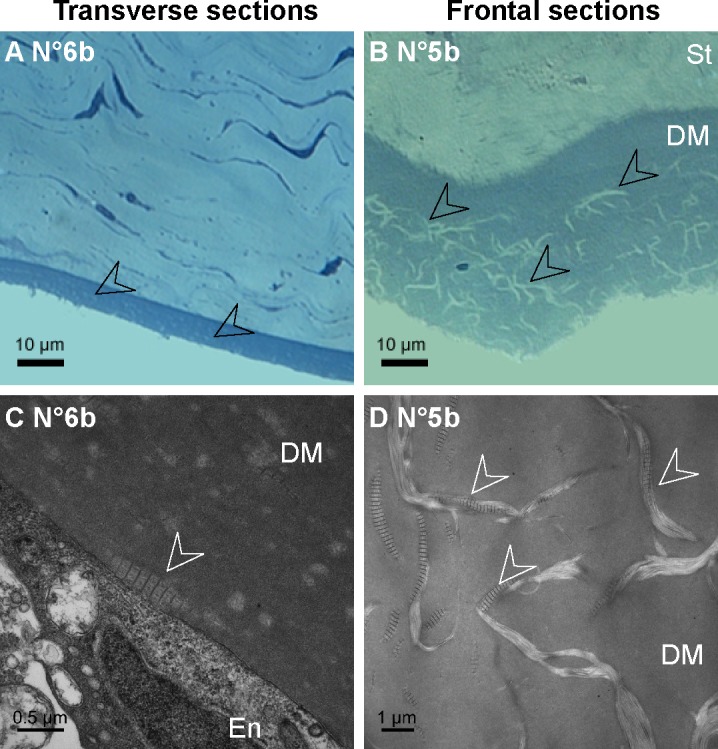

On histology, toluidine blue staining confirmed the presence of abnormal deposits in the DM posterior part of the diabetic corneas (Figs. 5A–5B) but did not allow identifying their composition. This was performed during TEM analysis that revealed the presence of long-spacing collagen fibrils at the same level (Figs. 5C–5D). In all the micrographs, these pathologic collagen fibrils were distributed in the posterior part of the DM, and some of them were observed just near the endothelial cells as illustrated in Figure 5C, suggesting their secretion by these cells.

Figure 5. .

Histology of the DM abnormalities in GK rat corneas. (A–B) Semi-thin sections of the corneal posterior parts, demonstrating abnormal deposits in the DM posterior part on transverse (A) as on frontal (B) sections. (C–D) Transmission electron micrographs of the DM on ultrathin sections, showing long-spacing collagen (C–D, white arrowheads), secreted by endothelial cells (C). En, endothelium; St, stroma.

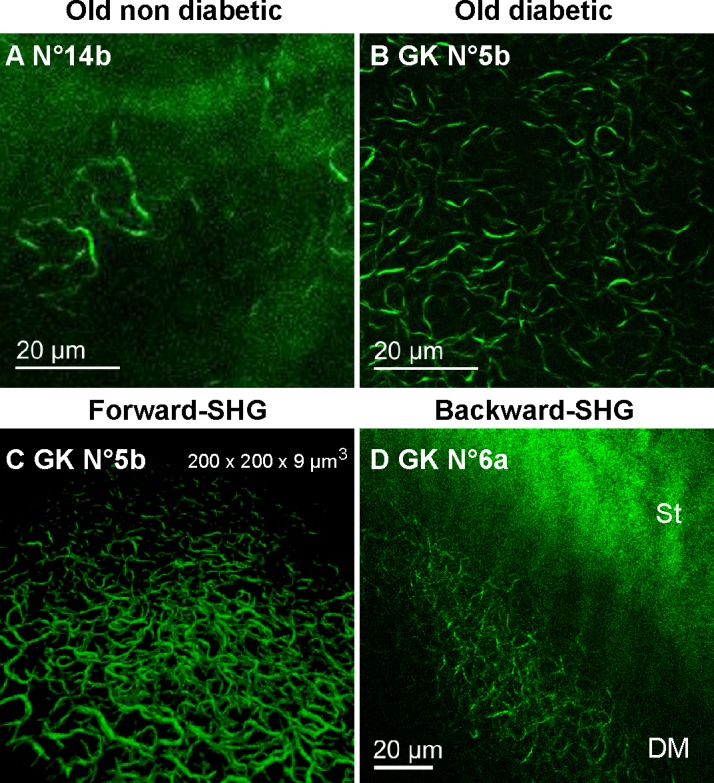

We then used ex vivo SHG microscopy to probe specifically these pathologic collagen fibrils with a larger field of view than in TEM and to characterize their 3D distribution in the DM. In the normal human cornea, ex vivo SHG microscopy reflects the distribution of the type 1 collagen in the stroma, while the nonfibrillar collagen constituting the DM does not exhibit SHG signals.27 In the DM of the GK rat corneas, the hyper-reflective structures highlighted by in vivo CCM exhibited strong SHG signals, while, as expected, other regions of the DM showed no signal. Their SHG-pattern was the same as previously described. The structures had a weak density in two old control corneas (Fig. 6A) and were very dense in all diabetic cases (Fig. 6B). Moreover, acquisition of image stacks with 0.5 μm axial steps enabled 3D reconstruction of DM abnormalities with excellent contrast (Fig. 6C) (see Movie for 3D view). While SHG observations of flat-mounted corneas were performed using forward-detected SHG signals, the proof of feasibility of the abnormalities' detection from the epithelium was carried out in rat eyeballs. Figure 6D demonstrates that the structures in the DM of a diabetic rat cornea exhibited backward SHG signals with the same high contrast, allowing epidetection of these structures.

Figure 6. .

Specific detection of the DM abnormalities using ex vivo SHG microscopy in diabetic rat corneas. (A–B) False color images generated by forward-detection of SHG signals in the flat-mounted corneas from 1-year old control (A, 20x objective) and diabetic (B, 60x objective) rats. (C) 3D reconstruction of the structures forward-detected in the GK cornea No. 7. (D) False color images generated by backward-detection of SHG signals in a diabetic rat eyeball. DM, Descemet's membrane; St, stroma.

Movie.

3D SHG view of the DM of the GK cornea No. 7 in false colors (200 × 200 × 9 μm3). Strong SHG signals are emitted by fibrillar collagen abnormalities, which allows their spatial characterization. Note that the fibrils in the foreground appear larger than in the background because of the 3D viewer.

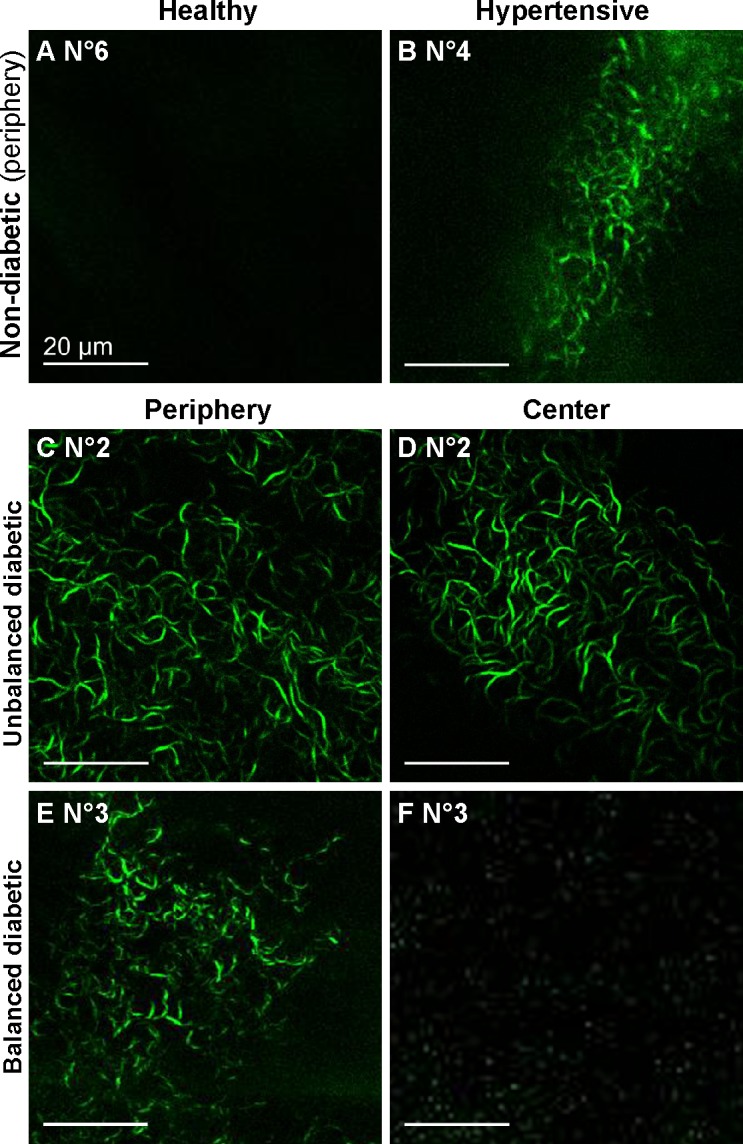

Three human corneas from diabetic patients (No. 1–3) (see Table 2) were also analyzed using SHG microscopy and compared to corneas from nondiabetic donors (No. 4–6). Observations at the DM level are synthesized in Table 5. No signal (No. 6) (Fig. 7A) or sparse signs of aging (No. 5) were detected in the DM of the corneas from nondiabetic donors. In the corneas from the third nondiabetic donors, with arterial hypertension and dyslipedemia (No. 4), few structures exhibiting SHG signals were detected only in the DM periphery (Fig. 7B). In the diabetic cases, whereas these structures were observed in the entire DM of the corneas from patients with unbalanced diabetes (No. 1 and No. 2) (Figs. 7C–7D), they were found only in the corneal periphery of the patient with balanced diabetes (No. 3) (Figs. 7E–7F).

Table 5. .

Main Ex Vivo SHG Findings in the DM of Human Corneas

Figure 7. .

Ex vivo SHG images in the DM of human corneas. (A–B) False color images of the corneas from nondiabetic donors, showing sparse SHG signals in corneal periphery of one hypertensive patient (B, in green; 20x objective). (C–F) False color images of the corneas from two diabetic donors, demonstrating the presence of SHG signals (in green) in the entire DM in the case of unbalanced diabetes (C–D; 60x objective) and only in the DM periphery in the case of balanced diabetes (E–F; 20x objective). Scale bar, 20 μm.

Histologic and TEM analysis confirmed that these abnormalities were identical to those observed in the diabetic rat corneas. They displayed long-spacing collagen fibrils, located in the inner part of the DM (Figs. 8A–8C), and therefore most likely produced by endothelial cells (Figs. 8D–8E). Senescence of the donors' endothelial layers was also observed, as shown in Figures 8C–8F identifying corneal endothelial dystrophy with endothelial cell extensions and long-spacing collagen.

Figure 8. .

Histology of the DM abnormalities in human corneas. (A-C) Semi-thin sections of the posterior corneas from diabetic donors, demonstrating abnormal deposits in the posterior part of the DM (A–B, white arrowheads) and endothelial dystrophy associated with cell extension in the limbus region (C, black arrowheads). (D–F) Transmission electron micrographs of the diabetic corneas DM, showing collagen secreted by endothelial cells (white arrowheads), appearing as long-spacing collagen on frontal sections (D) and as fibrils on transverse sections (E). In the limbus region (F), TEM also showed long-spacing collagen fibrils (white arrowheads) between endothelial cell extensions (black arrowheads). En, endothelium; St, stroma.

Discussion

In the present study, in vivo CCM highlighted structural abnormalities in the entire corneal thickness of the GK model of type 2 diabetes. It confirms the potential of this noninvasive imaging modality as a diagnostic tool, as extensively studied for 5 years for diabetic neuropathy.31,32 For this purpose, in vivo CCM is currently used in both preclinical33 and clinical34 studies. The contrast mechanism of this system relies on spatial variations of refractive indices, like in light-scattering interfaces, as junctions between cytoplasm or extracellular fluid and lipid-rich membranes of cells, nucleus and mitochondria.35 CCM allows easy recognition of the corneal nerves and, so, the development of a new algorithm to perform image rebuilding of the sub-basal nerve plexus.36 However, confocal reflectance microscopy shows limited contrast and specificity to identify the structures responsible for the abnormal reflectance detected in the DM of the GK rat corneas.

To complement these in vivo CCM observations, TEM imaging revealed the nature of the long-spacing collagen deposits in the DM. Nevertheless, these classic methods require stained corneal sections and are long to carry out. As SHG microscopy allows specific detection of collagen fibrils in unstained tissues, this femtosecond laser-based technology was tested as a quickest alternative method. SHG is a multiphoton mode of contrast that appears at half of the excitation wavelength and is specific for dense non-centrosymmetric structures, such as collagen fibrils. In contrast, nonfibrillar collagen, such as type IV and type VIII collagen in the DM, exhibits no SHG signal because of its centrosymmetric organization. We, therefore, expected SHG to be a valuable tool to evidence fibrillar collagen deposits among nonfibrillar matrix. Accordingly, comparison between in vivo CCM images and ex vivo SHG images demonstrated that the hyper-reflective structures found in the DM of the GK rat corneas exhibited strong SHG signals, in both forward and backward directions, on a SHG silent background. These results showed that SHG microscopy could detect hyperglycemia-induced abnormalities with excellent contrast in GK corneas, as well as in human corneas from diabetic donors. Comparative imaging of corneas from hyperglycemic individuals therefore provided complementary information on DM structural changes. We noted that the long-spacing collagen fibrils in the DM were thinner than 1 μm in TEM images, while they appeared larger in CCM images because of the lower resolution (1 μm pixel size) and of the automatic contrast setting that impedes the detection of thin structures.

Backward-detected SHG imaging has been demonstrated in ex vivo ocular globes and could thus provide a diagnosis for chronic hyperglycemia-induced effects in the corneal tissue. First developments toward a clinical imaging system have been reported recently28 and showed that in vivo SHG imaging can generate quantitative information about the collagen architecture in the stroma. This femtosecond laser-based imaging system could thus provide additional diagnosis of structural abnormalities in the stroma, observed in other corneal pathologies.

From a pathophysiologic point of view, this study has highlighted focal abnormal reflectance in the basal epithelium of diabetic corneas that is a sign of diabetic keratopathy. On histology, numerous epithelial basal cells were in a proliferative state, as reported by Wakuta et al.l9 The increased proliferation of epithelial cells in the cornea of GK rats was demonstrated to be associated with a delay in wound healing and, thus, to affect the epithelial barrier function. These features were met again in the streptozotocin-induced model of type 1 diabetes,37 and in diabetic patients using the fluorescein test6 or in vivo CCM.8 The well-known epithelial basement membrane abnormality of diabetic corneas3–5 was also observed in our study, in both rat and human corneas. The increased reflectivity measured at the interface between the epithelial basal cell layer and the anterior stroma by Morishige et al39 and Takahashi et al40 could explain the hyper-reflectance detected on the CCM transverse images of the GK rat epitheliums generated in our experiments. From a biochemical point of view, the abnormalities noticed at the epithelium-stroma interface in the cornea of GK rats might reflect the chronic hyperglycemia-induced effects, in particular the Maillard reactions. These reactions result in the formation of AGEs, which are responsible for non-enzymatic glycation reactions on the extracellular matrix proteins. Their effects increase with aging41 and are amplified by diabetes.42 Increased protein glycations12–14 and oxidative stress43 are involved in diabetic cornea alterations, such as decreased stability in the epithelial basement membrane and changes in the collagen matrix of the anterior stroma. However, whether AGEs have cytotoxic effects mediated by the AGE receptors (RAGE) on corneal keratocytes remains to be studied.

Regarding the posterior layers of the diabetic corneas, various endothelial abnormalities, in particular endothelial dystrophy and abnormal cell morphology, were noticed in the corneas of the oldest GK rats. Corneal observations in diabetic patients using CCM or specular microscopy have actually shown that diabetes may disturb the stromal hydration through decreased endothelial cell density,17 in particular after cataract surgery,18 and polymegathism (changes in their size).19,20 The endothelium may thus be under greater metabolic stress in diabetic than in healthy subjects. Endothelial cells are known to be sensitive to AGEs44 and to express their receptors.45 Therefore, AGE formation may be responsible for non-enzymatic glycation, leading to endothelial cell loss,45 but also for the RAGE pathway activation. This may induce changes in gene expression in endothelial cells and, so, the abnormal secretion of long-spacing collagen in the DM of diabetic rat16,15 and human corneas.5 These pathologic collagen fibrils were detected as hyper-reflective and rod-shaped structures in the DM and in the endothelial cell junctions using in vivo CCM, and then, TEM which allowed imaging their synthesis by the endothelial cells. Blood sugar levels revealed the hyperglycemic state of the observed GK rats; however, they are not indicative of the metabolic effects of diabetes. For such a purpose, glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) should be measured. Even if this indicator was not followed at the time of our experiments, the preliminary data currently measured in our facilities show that HbA1c levels start to increase before 3 months of age in GK rats in comparison with Wistar rats. Recent papers46,47 have also demonstrated that, whereas HbA1c slightly increased from 4 to 5% at 12 weeks and then reached a plateau in Wistar rats, HbA1c levels in GK rats showed a delayed increase relative to glucose at 4 weeks, and then gradually increased until the end of the studies, from 4 to 5%, to 9% at 12 weeks46 or to over 11% at 20 weeks of age.47 These data allowed us to state that the deposits observed in the DM at 12 weeks of age in GK rat corneas were synthesized as soon as the diabetes induced metabolic effects.

Moreover, these abnormalities were observed in human corneas from diabetic donors, with higher density in the cases of unbalanced diabetes, notably in the cornea from a patient with a HbA1c level over 9%, than in balanced diabetes, in the case of a donor with a normal HbA1c level. These collagen deposits have also been observed in the corneas from hypertensive old patients in our study, and reported in other endothelial pathologies, such as iridocorneal-endothelial syndrome48,49 and Fuch's dystrophy,48–51 in which AGEs accumulate as well as oxidative stress.52 Diabetes-induced tissue changes have been characterized as accelerated aging in many organs, and also in collagen changes.53 Our observations let us hypothesize that the abnormal collagen synthesis is an age-related phenomenon observed earlier and exacerbated in diabetic conditions and, probably, in other metabolic diseases inducing an oxidative stress on corneal endothelial cells.

To conclude, we have used complementary imaging techniques to demonstrate that diabetes alters the structure of all corneal layers. In diabetic rat corneas, we have mainly highlighted structural abnormalities at the epithelium-stroma interface and fibrillar collagen deposits in the DM. This latter feature has also been observed and characterized in human corneas using SHG microscopy, and confirmed by TEM. Subclinical abnormalities could predispose diabetic patients to wound healing delay and also serve as early signs of diabetes-induced tissue structure modifications. Our observations in the DM demonstrated that diabetes altered the collagen structure of this layer, with the formation of long-spacing collagen fibrils synthesized by corneal endothelial cells. Whether these changes could be correlated to blood–sugar-level control remains to be demonstrated. Moreover, we have shown that SHG microscopy, an emerging multiphoton imaging method that is highly specific for collagen fibrils, could provide a diagnosis for chronic hyperglycemia-induced effects in the corneal tissue. Further studies are required to evaluate if diabetes-induced corneal collagen alterations can predict the development of diabetic retinopathy.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Isabelle Sourati and Patrick Sabatier (Banque Française des Yeux, Paris), Jean-Marc Legeais (Sorbonne Paris Cité, Paris Descartes University; AP-HP Hôtel-Dieu Hospital, Department of Ophthalmology), and Patricia Crisanti (INSERM UMRS 872, Team17: Physiopathology of ocular diseases, therapeutic innovations).

Laura Kowalczuk was supported by the “Agence Nationale de la Recherche”, ANR-08-TecSan-012 “NOUGAT.” Gaël Latour was supported by “RTRA-Triangle de la Physique” and “Fondation de France - Fondation Berthe Fouassier.” The work at LOB was supported by ANR-10-INBS-04.

Disclosure: L. Kowalczuk, None; G. Latour, None; J.-L. Bourges, None; M. Savoldelli, None; J.-C. Jeanny, None; K. Plamann, None; M.-C. Schanne-Klein, None; F. Behar-Cohen, None

References

- 1.Brownlee M. Biochemistry and molecular cell biology of diabetic complications. Nature. 2001;14(6865):813–820. doi: 10.1038/414813a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Omri S, Behar-Cohen F, de Kozak Y, et al. Microglia/macrophages migrate through retinal epithelium barrier by a transcellular route in diabetic retinopathy: role of PKCζ in the Goto Kakizaki rat model. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(2):942–953. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schultz RO, Van Horn DL, Peters MA, Klewin KM, Schutten WH. Diabetic keratopathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1981;79:180–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Azar DT, Spurr-Michaud SJ, Tisdale AS, Gipson IK. Altered epithelial-basement membrane interactions in diabetic corneas. Arch Ophthalmol. 1992;110(4):537–540. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1992.01080160115045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rehany U, Ishii Y, Lahav M, Rumelt S. Ultrastructural changes in corneas of diabetic patients: an electron-microscopy study. Cornea. 2000;19(4):534–538. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200007000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gekka M, Miyata K, Nagai Y, et al. Corneal epithelial barrier function in diabetic, 110 patients. Cornea. 2004;23(1):35–37. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200401000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang PY, Carrel H, Huang JS, et al. Decreased density of corneal basal epithelium and subbasal corneal nerve bundle changes in patients with diabetic retinopathy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2006;142(3):488–490. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2006.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen WL, Lin CT, Ko PS, et al. In vivo confocal microscopic findings of corneal wound healing after corneal epithelial debridement in diabetic vitrectomy. Ophthalmology. 2009;116(6):1038–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wakuta M, Morishige N, Chikama T, Seki K, Nagano T, Nishida T. Delayed wound closure and phenotypic changes in corneal epithelium of the spontaneously diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(2):590–596. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kaji Y, Usui T, Oshika T, et al. Advanced glycation end products in diabetic corneas. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(2):362–368. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McDermott AM, Xiao TL, Kern TS, Murphy CJ. Non-enzymatic glycation in corneas from normal and diabetic donors and its effects on epithelial cell attachment in vitro. Optometry. 2003;74(7):443–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sady C, Khosrof S, Nagaraj R. Advanced Maillard reaction and crosslinking of corneal collagen in diabetes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1995;214(3):793–797. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1995.2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sato E, Mori F, Igarashi S, et al. Corneal advanced glycation end products increase in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes Care. 2001;24(3):479–482. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.3.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akimoto Y, Kawakami H, Yamamoto K, Munetomo E, Hida T, Hirano H. Elevated expression of O-GlcNAc-modified proteins and O-GlcNAc transferase in corneas of diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(9):3802–3809. doi: 10.1167/iovs.03-0227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rehany U, Ishii Y, Lahav M, Rumelt S. Collagen pleomorphism in Descemet's membrane of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats: an electron microscopy study. Cornea. 2000;19(3):390–392. doi: 10.1097/00003226-200005000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Akimoto Y, Sawada H, Ohara-Imaizumi M, Nagamatsu S, Kawakami H. Change in long-spacing collagen in Descemet's membrane of diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats and its suppression by antidiabetic agents. Exp Diabetes Res. 2008 doi: 10.1155/2008/818341. 2008:818341. doi: 10.1155/2008/818341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shenoy R, Khandekar R, Bialasiewicz A, Al Muniri A. Corneal endothelium in patients with diabetes mellitus: a historical cohort study. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2009;19(3):369–375. doi: 10.1177/112067210901900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mathew PT, David S, Thomas N. Endothelial cell loss and central corneal thickness in patients with and without diabetes after manual small incision cataract surgery. Cornea. 2011;30(4):424–428. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3181eadb4b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JS, Oum BS, Choi HY, Lee JE, Cho BM. Differences in corneal thickness and corneal endothelium related to duration in diabetes. Eye (Lond) 2006;20(3):315–318. doi: 10.1038/sj.eye.6701868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.González-Méijome JM, Jorge J, Queirós A, Peixoto-de-Matos SC, Parafita MA. Two single descriptors of endothelial polymegethism and pleomorphism. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248(8):1159–1166. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1337-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zipfel WR, Williams RM, Webb WW. Nonlinear magic: multiphoton microscopy in the biosciences. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21(11):1369–1377. doi: 10.1038/nbt899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yeh AT, Nassif N, Zoumi A, Tromberg BJ. Selective corneal imaging using combined second-harmonic generation and two-photon excited fluorescence. Opt Lett. 2002;27(23):2082–2084. doi: 10.1364/ol.27.002082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han M, Giese G, Bille JF. Second harmonic generation imaging of collagen fibrils in cornea and sclera. Opt. Express. 2005;13(15):5791–5797. doi: 10.1364/opex.13.005791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Teng SW, Tan HY, Peng JL, et al. Multiphoton autofluorescence and second-harmonic generation imaging of the ex vivo porcine eye. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2006;47(3):5251–5259. doi: 10.1167/iovs.04-1520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morishige N, Wahlert AJ, Kenney MC, et al. Second-harmonic imaging microscopy of normal human and keratoconus cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2007;48(3):1087–1094. doi: 10.1167/iovs.06-1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Steven P, Hovakimyan M, Guthoff RF, Hüttmann G, Stachs O. Imaging corneal crosslinking by autofluorescence 2-photon microscopy, second harmonic generation, and fluorescence lifetime measurements. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2010;36(10):2150–2159. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2010.06.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aptel F, Olivier N, Deniset-Besseau A, et al. Multimodal nonlinear imaging of the human cornea. Invest Ophthalol Vis Sci. 2010;51(5):2459–2465. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-4586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Latour G, Gusachenko I, Kowalczuk L, Lamarre I, Schanne-Klein M-C. In vivo structural imaging of the cornea by polarization-resolved second harmonic microscopy. Biomed Opt Express. 2012;3(1):1–15. doi: 10.1364/BOE.3.000001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.European Eye Bank Association (EEBA): EEBA Directory; EEBA. Amsterdam: 2010. 18th ed. eds. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Labbé A, Liang H, Martin C, Brignole-Baudouin F, Warnet JM, Baudouin C. Comparative anatomy of laboratory animal corneas with a new-generation high-resolution in vivo confocal microscope. Curr Eye Res. 2006;31(6):501–509. doi: 10.1080/02713680600701513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schultz RO, Peters MA, Sobocinski K, Nassif K, Schultz KJ. Diabetic corneal neuropathy. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 1983;81:107–124. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pritchard N, Edwards K, Shahidi AM, et al. Corneal markers of diabetic neuropathy. Ocul Surf. 2011;9(1):17–28. doi: 10.1016/s1542-0124(11)70006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Davidson EP, Coppey LJ, Holmes A, Yorek MA. Changes in corneal innervation and sensitivity and acetylcholine-mediated vascular relaxation of the posterior ciliary artery in a type 2 diabetic rat. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2012 doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8806. Epub ahead of print. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-8806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tavakoli M, Kallinikos P, Iqbal A, et al. Corneal confocal microscopy detects improvement in corneal nerve morphology with an improvement in risk factors for diabetic neuropathy. Diabet Med. 2011(10); 28:1261–1267. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03372.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03372.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guthoff RF, Baudouin C, Stave J. Atlas of Confocal Laser Scanning In-vivo Microscopy in Ophthalmology. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg;; 2006. Principles of confocal in vivo microscopy; pp. 3–22. In. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Allgeier S, Zhivov A, Eberle F, et al. Image reconstruction of the subbasal nerve plexus with in vivo confocal microscopy. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011;52(9):5022–5028. doi: 10.1167/iovs.10-6065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yin J, Huang J, Chen C, Gao N, Wang F, Yu FS. Corneal complications in streptozocin-induced type I diabetic rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2011(9); 52:6589–6596. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7709. doi: 10.1167/iovs.11-7709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Taylor HR, Kimsey RA. Corneal epithelial basement membrane changes in diabetes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1981;20(4):548–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Morishige N, Chikama TI, Sassa Y, Nishida T. Abnormal light scattering detected by confocal biomicroscopy at the corneal epithelial basement membrane of subjects with type II diabetes. Diabetologia. 2001;44(3):340–345. doi: 10.1007/s001250051624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Takahashi N, Wakuta M, Morishige N, Chikama T, Nishida T, Sumii Y. Development of an instrument for measurement of light scattering at the corneal epithelial basement membrane in diabetic patients. Jpn J Ophthalmol. 2007;51(3):185–190. doi: 10.1007/s10384-007-0427-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Malik NS, Moss SJ, Ahmed N, Furth AJ, Wall RS, Meek KM. Aging of the human corneal stroma: structural and biochemical changes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 19921138(3):222–228. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(92)90041-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stitt AW. The maillard reaction in eye diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1043:582–597. doi: 10.1196/annals.1338.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim J, Kim CS, Sohn E, Jeong IH, Kim H, Kim JS. Involvement of advanced glycation end products, oxidative stress and nuclear factor-kappaB in the development of diabetic keratopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2011;249(4):529–536. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kaji Y, Amano S, Usui T, et al. Advanced glycation end products in Descemet's membrane and their effect on corneal endothelial cell. Curr Eye Res. 2001;23(6):469–477. doi: 10.1076/ceyr.23.6.469.6968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kaji Y, Amano S, Usui T, et al. Expression and function of receptors for advanced glycation end products in bovine corneal endothelial cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2003;44(2):521–528. doi: 10.1167/iovs.02-0268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Gao W, Bihorel S, DuBois DC, Almon RR, Jusko WJ. Mechanism-based disease progression modeling of type 2 diabetes in Goto-Kakizaki rats. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn. 2011;38(1):143–162. doi: 10.1007/s10928-010-9182-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Xue B, Sukumaran S, Nie J, Jusko WJ, Dubois DC, Almon RR. Adipose tissue deficiency and chronic inflammation in diabetic Goto-Kakizaki rats. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levy SG, McCartney AC, Sawada H, Dopping-Hepenstal PJ, Alexander RA, Moss J. Descemet's membrane in the iridocorneal-endothelial syndrome: morphology and composition. Exp Eye Res. 1995;61(3):323–333. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(05)80127-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Levy SG, Moss J, Sawada H, Dopping-Hepenstal PJ, McCartney AC. The composition of wide-spaced collagen in normal and diseased Descemet's membrane. Curr Eye Res. 1996;15(1):45–52. doi: 10.3109/02713689609017610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang C, Bell WR, Sundin OH, et al. Immunohistochemistry and electron microscopy of early-onset fuchs corneal dystrophy in three cases with the same L450W COL8A2 mutation. Trans Am Ophthalmol Soc. 2006;104:85–97. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gottsch JD, Zhang C, Sundin OH, Bell WR, Stark WJ, Green WR. Fuchs corneal dystrophy: aberrant collagen distribution in an L450W mutant of the COL8A2 gene. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46(12):4504–4511. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang Z, Handa JT, Green WR, Stark WJ, Weinberg RS, Jun AS. Advanced glycation end products and receptors in Fuchs' dystrophy corneas undergoing Descemet's stripping with endothelial keratoplasty. Ophthalmology. 20071453(8):114–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2006.10.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hamlin CR, Kohn RR, Luschin JH. Apparent accelerated aging of human collagen in diabetes mellitus. Diabetes. 1975;24(10):902–904. doi: 10.2337/diab.24.10.902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]