Abstract

Recent trends place an emphasis on school health care, the ultimate goal of which is to protect, maintain, and promote students' health. School health care is a program that integrates health care services, health education, health counseling, and local social health services. The student health examination (SHE) system is a part of school health care and schools and communities must be available to provide professional health services. Pediatricians also have important roles as experts in both school health care and the SHE system. In this article, the history of school health care, its legal basis, and the current status of the SHE system in Korea are reviewed. Furthermore, sample surveys from the past few years are reviewed. Through this holistic approach, future directions are proposed for the improvement of SHE and school health care.

Keywords: School health care, School health examination, Student health examination

Introduction

School is a special environment where school-aged children spend most of their time during the day. Students have low resistance to disease and undergo growth spurts. Recent trends emphasize the importance of preventive student health care and the significance of the roles played by school health care and student health examination (SHE). The ultimate goal of school heath care is to protect, maintain, and promote students' health.

School health care combines health services and education and is viewed as a complete program that integrates health care, education, counseling, and local social services. The goals associated with schooling and social education can only be achieved if students are healthy. Therefore, schools and society must provide professional health services to protect and maintain students' health.

Health among Korean children and adolescents is deteriorating, for example, the prevalence of obesity is increasing, which has caused a sudden increase in medical expenditure. Furthermore, students begin smoking at younger ages, drink alcohol more often, attempt suicide, are involved in sexual experiences, frequently eat meals that have poor nutritional value, and are under substantial stress caused by "examination-related stress." These factors will increase the future burden of disease and medical expenditure, and they highlight the importance of improving students' health-related behavior, educating them about the health problems they might encounter, and detecting diseases at early stages.

In Europe, school health care for children started in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. England and the United States (US) started school health care programs by providing school food services and then expanding the scope of the programs to include medical services and school physical education. The US started a school doctor system in the 1890s. The principal duty of school doctors was to prevent infectious diseases, but they slowly took on other duties that included medical checkups, school health education, and the provision of healthy environments1,2). School health care then evolved from management of school health care services to performance of pivotal roles in educating local communities.

Recent trends in school health care in Korea

In Korea, school health care for children started in the late 19th century, when the new education system was introduced. Hygiene and physical education began in schools after the proclamation of the School Act Number 1 Regulation at the Hansung Teacher Training School, which stated that since physical fitness is an important part of learning, every student should attend to personal sanitation and perform gymnastics to promote health3). After the restoration of independence from Japanese imperialism, the Regulations for Education Act 89 was implemented. This act required every school to conduct physical examinations for their students and to be equipped with caregiving amenities within their facilities; this upheld the importance of school health promotion services.

In 1951, the School Physical Examination Regulation (Education Ministry Act 15) regarding physique, constitution, and fitness was established. In 1953, the School Lunch Aid Service was provided by the United Nations Children's Fund. The School Physical Examination and Tuberculosis Examination Service began in 1955, the Parasiticide Service began in 1957, and the Medical Examination Service began in 1960.

On March 30, 1967, "the School Health Act" (Act 1928) was established to provide appropriate legislative foundations. Standards were also established for hygiene procedures within the school environment and for people in charge of school health. In 1969, the School Health Act was renamed "the School Physical Examination Regulation." This regulation was expanded in 1971 to include a School Disease Control Project and blood tests; in 1977, inspections to control tuberculosis were included.

In 1979, the Education Ministry (Ordinance 446) proclaimed that routine health examinations would be conducted during April and May every year, and that each school would report its results in late July, thereby laying the foundation for school physical examinations. A urinalysis project to assess diabetes mellitus, proteinuria, and hematuria and an oral health project consisting of a fluoride mouth-rinsing program began in 1980. In 1988, a nearsightedness prevention project was augmented, and in 1993, a screening inspection for scoliosis was introduced on a trial basis.

In 1996, the School Physical Examination Regulation (Education Ministry Ordinance 676) was modified to exclude examinations for parasitic infections and to include allergic diseases, extreme obesity, urinalysis, and blood tests as mass screening items. In 1997, the School Physical Examination Article (Education Ministry Article 706) was revised to include hospital-based examination of the physiques and constitutions of high school freshmen, and in 1998, a general health checkup was implemented for all high school students. A congressional petition led to students of all ages, from elementary school to high school, undergoing urinalysis for the early detection of kidney disorders.

In 2002, the Ministry of Education and Human Resources Development revised the School Health Act, which had originally included high school freshmen for mass screening in accordance with the National Health Insurance Act, to include first and fourth grade elementary school students, and middle school and high school freshmen for mass screening tests in accordance with the National Health Insurance Act in preparation for legislation.

In March 2005, the School Health Act (Article 7396) was transformed from a physical examination system to a health screening system. Each school was required to improve the promotion of student health and to establish a system to document the results of health screening. In 2007, the School Health Act was revised to include oral examinations for elementary school students, a mental health care management program, and an education program to improve health-related behavior in students. Hence, the institutional school health system progressed in parallel with the expanding program of school health care.

The legal basis and current status of the SHE system

1. Legal basis

The current SHE system is conducted in accordance with the School Health Act Article 7 (including health examinations), Article 7-2 (establishment of health promotion plans), Article 7-3 (health examination records), School Health Examination Regulations Article 3 (enforcement of health examinations), Article 4 (examination methods for establishing physical development status), Article 4-2 (items and inspection methods for undertaking health surveys), Article 5 (items and inspection methods for undertaking health examinations), Article 5-2 (including processes for undertaking health examinations), Article 6 (additional inspections), National Health Service Article 47-2, Enforcement Ordinance Article 26-4, 26-7, Framework Article on Health Examination Article 14 (the designation of medical institutions), enforcement criteria for health examinations (the official announcement from the Ministry of Health and Welfare), detailed rules for the operation of health examination (Health Examination Department of the National Health Insurance Service), and criteria for the judgment of School Health Examination results and recording methods (the official announcement from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology).

The goals of SHE are 1) to provide strategies to prevent and treat various diseases through early detection using routine SHE; 2) to provide health consultation, proper treatment, and protection for those in whom early-stage disorders are detected; and 3) to establish policies to improve student health and implement effective student health promotion projects by analyzing the results from SHE and managing key health indicators.

In a survey conducted among school nurses, 84.2% of the nurses felt that the SHE system is helpful in improving student health and 63.2% responded that they had implemented school health activities to promote student health care projects based on the results from the SHE system. In addition, 87.7% of the nurses responded that they utilized SHE results in the next school year4). Taken together, SHE results appear to be frequently utilized to promote student health.

2. Components of the SHE

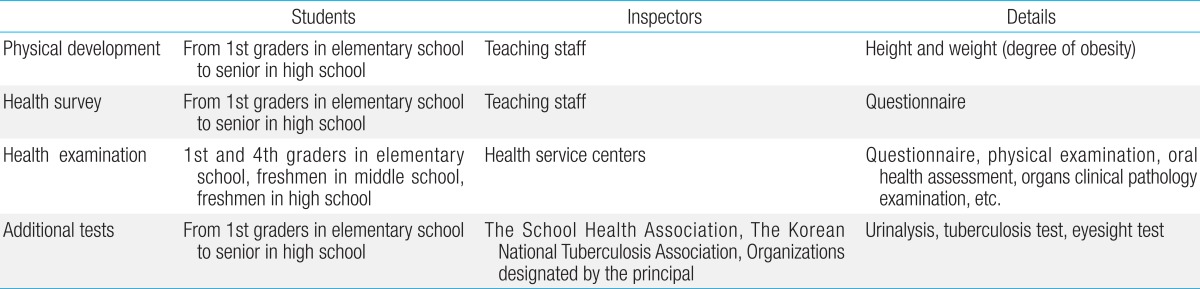

The SHE consists of an assessment of the current status of physical development, a health survey, a health examination, an assessment of the body's capability and additional tests (Table 1). Teachers assess the developmental status of students, from first grade students through to the senior students in high schools, and they conduct health surveys. Growth is assessed by measuring each student's height and weight. The degree of obesity is determined by calculating the body mass index and the relative weight and assessing these values against the age- and sex-specific percentiles on the 2007 Korean Growth Charts. The health survey includes a structured questionnaire to determine vaccinations, past disease history, health behavior, and daily living habits. Details of the health survey are described below.

Table 1.

Classification of student health examinations

For the health examination, first and fourth grade students in elementary schools, freshmen in middle schools, and freshmen in high schools are required to visit nearby health service centers. The content of the health examination is described below, and additional examinations are possible.

3. Health survey

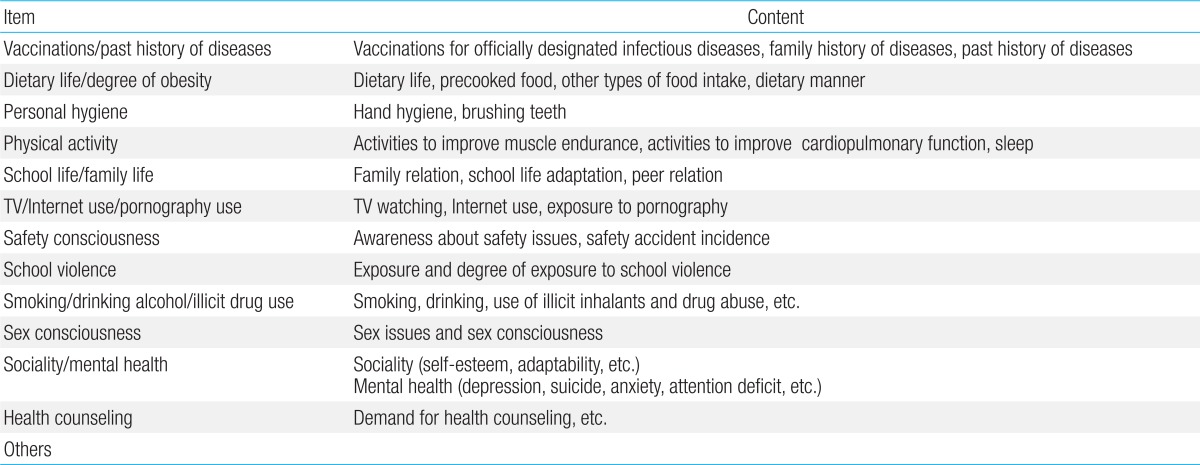

The health survey questionnaires assess several factors, including vaccination history, past disease history, dietary intake, degree of obesity, personal hygiene, physical activity, school life, family life, television/Internet/pornography use, safety consciousness, violence in school, smoking habits/alcohol consumption/illicit drug use, sex awareness, sociability, mental health, health consultation, and miscellaneous. To conduct the health surveys, Superintendents of Education in each city or province are required to assemble and distribute structured questionnaires to each school for delivery to students in elementary, middle, and high schools, and to the teaching staff. Details of the health survey are described below and in Table 2.

Table 2.

Health survey items and their contents

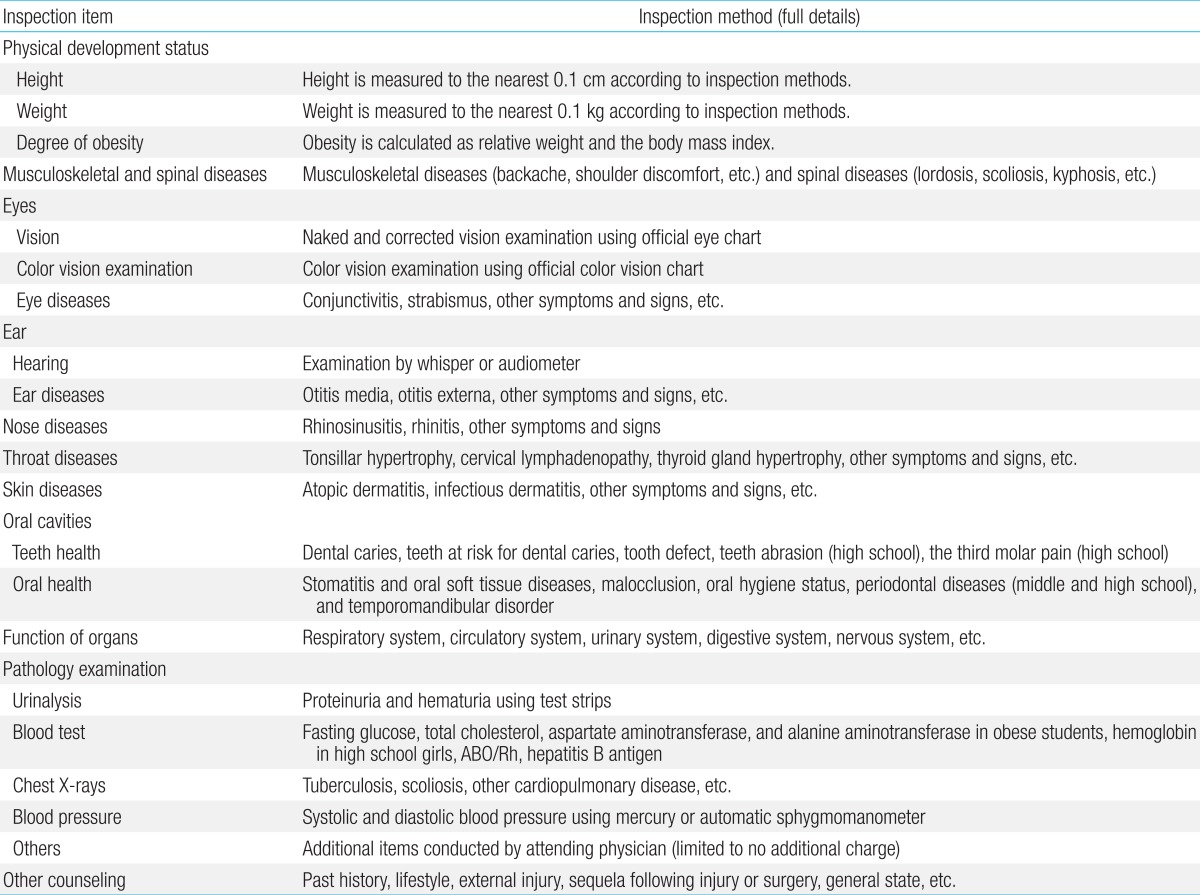

4. Content of the health examination

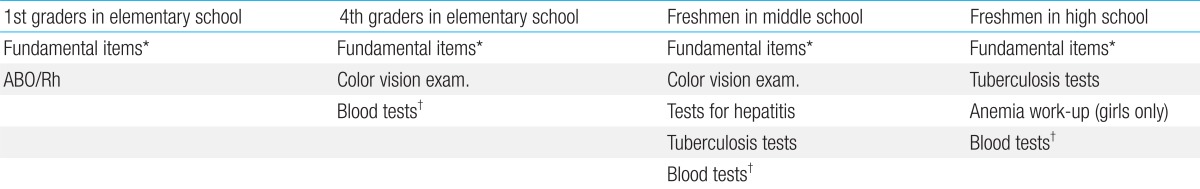

The items included in the health examinations differ according to the age of the students, their gender, and the presence of obesity. Fundamental items are the same for all grades, and additional items are assessed in some age groups, for example, ABO/Rhesus blood types for first grade students in elementary school, examination of color vision in fourth grade students in elementary schools, color vision examination, hepatitis tests, and chest radiography for middle school freshmen, chest radiography for high school freshmen, and anemia work-ups for high school female freshmen. If students higher than the fourth grade in elementary school are diagnosed with obesity, they are asked to undergo blood tests for assessing fasting glucose, total cholesterol, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) levels. Table 3 lists the fundamental and supplementary items that comprise the health examination and the full details of all items are given in Table 4.

Table 3.

Items inspected for each grade

*Fundamental items: musculoskeletal and spinal examinations, eye, ear, nostrils, throat, skin, dental check-up (all grades in elementary school), urinalysis, blood pressure, function of organs, and physical examination and counseling. †Blood tests for obese students: fasting glucose, total cholesterol, aspartate aminotransferase ,and alanine aminotransferase.

Table 4.

Full details of inspection items and inspection methods

5. Additional tests

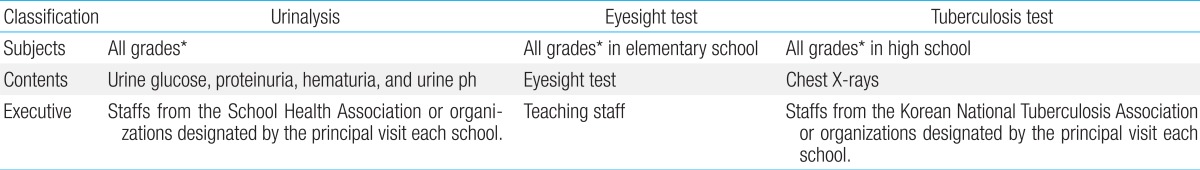

Additional tests are conducted to protect and promote aspects of student health other than those examined by the SHE, and these are detailed in Table 5. The costs of these tests are borne by the schools' basic operating expenses, with additional budgets drawn up for schools that are not given state subsidies. Parents of students with abnormal urinalysis findings are instructed to have their children thoroughly examined medically and to ensure that the abnormalities are properly treated at an early stage.

Table 5.

Additional tests and their details

*Excluding the grades in whom health examination is performed.

Teaching staff perform eyesight tests. Middle school and high school teaching staff are advised to perform eyesight test in their schools in a self-regulatory manner. Parents of students with abnormal eyesight test findings are instructed to have their children thoroughly examined medically, and to ensure that treatment is sufficient to manage the early stages of any conditions found.

Students with abnormal findings on chest radiographs, such as tuberculosis, are recommended to notify a community health center about their tuberculosis infection to ensure that they receive appropriate treatment.

The operating system and enforcement processes for health examinations

1. Establishment of plans for school health examinations

The head of each school is required to establish detailed plans for SHE, including the necessary budget, by March every year. The budget for SHE should be supported by the school's basic operating expenses.

2. Selection of medical institutions or dental clinics and contract development

The head of each school must select at least 2 medical institutions and 2 dental clinics that meet predetermined criteria, including appropriate facilities, adequate manpower, and computerized processing of health care-related information. These organizations should be selected in consultation with the school management committee. Schools should prepare a contract for SHE and consult the medical institutions about the timing of the medical examinations, the number of comprehensive medical examinations that can be undertaken per day, and the counseling services provided by the doctors. If suitable medical institutions are few in number and the numbers of examinees are low, schools may select only 1 medical institution, subject to approval by the Superintendent of Education.

3. Enforcement of SHE

Students should visit medical institutions and undergo health examinations during the contracted periods. The health examination and health survey (substituted by the questionnaire) should be conducted, and the developmental status of each examinee should be established at each medical institution. No additional tests besides those identified in the School Health Act or School Health Examination Regulations are approved for implementation.

4. Reporting of health examination results by medical institutions

Each medical institution should notify the students or guardians and the head of each school about the results of the health and oral examinations within 15 days of completion of the examinations. These results and other records, including radiographs and official reports on the radiographs, should be retained by the medical facility for 5 years in accordance with the minor regulations for health examination by the National Health Insurance Corporation. Medical institutions can ask schools to pay for the expenses associated with a health examination within 30 days of completion of the examination.

5. Measures implemented by schools after the notification of health examination results

Schools should record the results of health and oral examination in each student's health record and utilize the results to promote student health. Students with infectious diseases, including those with suspected infectious diseases, should undergo a complete medical examination immediately. The schools should notify the students or their guardians about the health examination results and instruct them to ensure that the medical examinations are thorough, the appropriate treatments are administered, and the students' health status is followed up thereafter. Schools should pay the expenses associated with the SHE within 15 days of the requisition date notified by the medical institutions. The head of each school should establish plans to promote school health by analyzing the SHE results (health survey, health examination, and the developmental status).

6. Inspection rates for health examinations and their outcomes

The inspection rates for the SHE demonstrated differences among regions and schools, and were 98.8% in 2006, 99.2% in 2007, 99.6% in 2008, and 99.5% in 2009. These were the highest inspection rates among all of the national health screening programs. Each school manages the quality of the SHE by conducting customer satisfaction surveys for students and parents regarding the medical institutions, and they determine ways to improve the SHE. Furthermore, when required, the school sends official documents that instruct the medical institutions to resolve any SHE-related issues that might be raised by the customer satisfaction surveys. The government requires each school to publish the results of the customer satisfaction survey on its Website's homepage to ensure that the local community and the school share the results and to promote the SHE. The medical institutions are not named as part of these results.

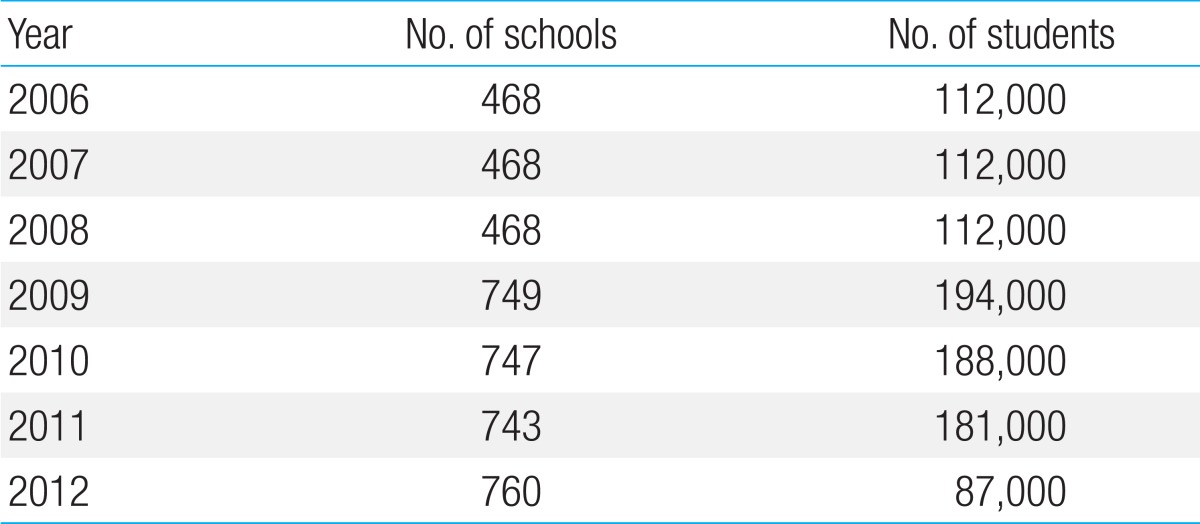

In addition, the government promotes the generation of health indicators obtained through sample surveys, student health promotion founded on evidence-based data, and policy development for school health. The Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology improved the sample survey system by implementing a 3-year sliding scale system that started in 2009. The results are available on a website called the Student Health Information Center (https://schoolhealth.kedi.re.kr). The numbers of schools and students that participated in sample surveys from 2006 to 2012 are listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Numbers of schools and students participating in sample surveys from 2006 to 2012

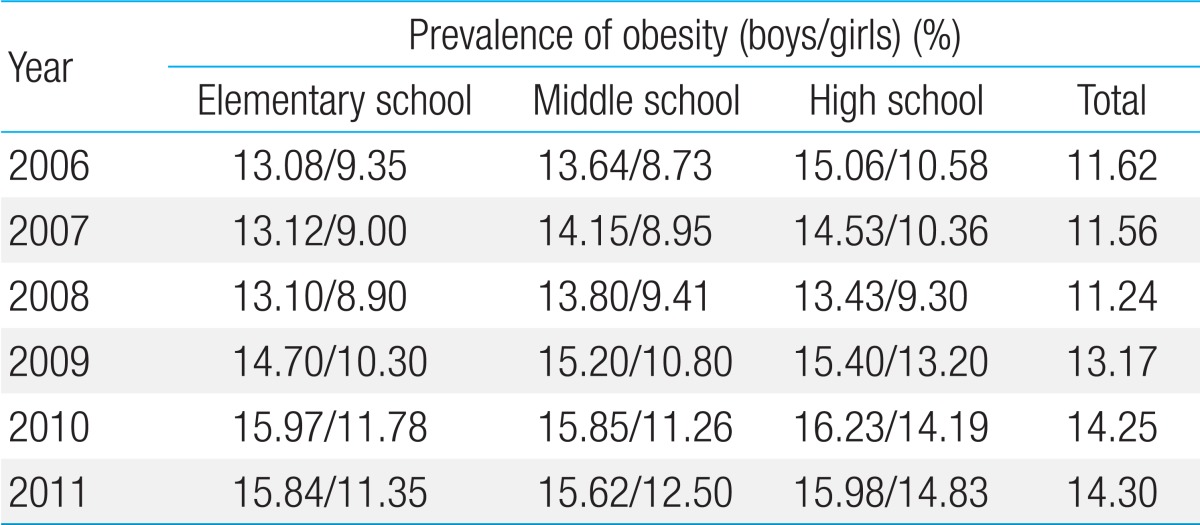

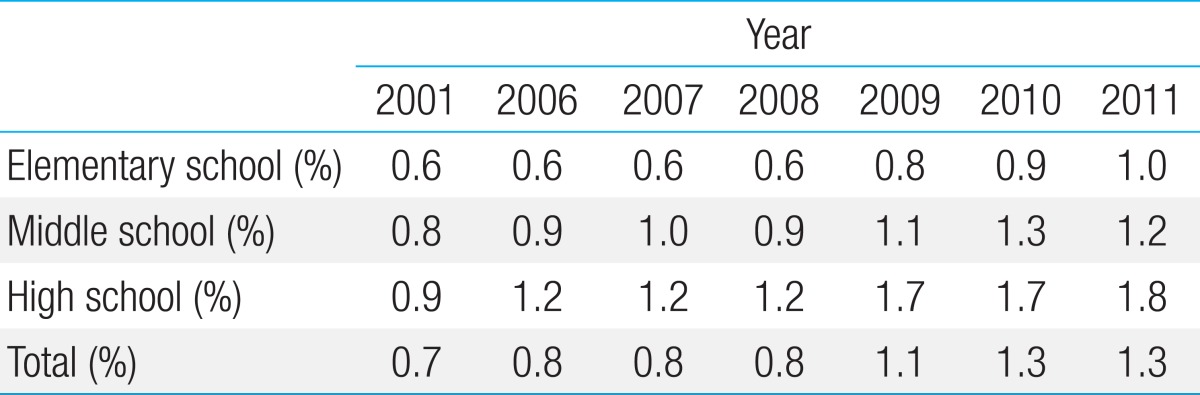

The prevalence of obesity increased from 11.6% in 2006 to 14.3% in 2011 (Table 7). The prevalence of severe obesity increased from 0.7% in 2001 to 0.8% in 2006 and 1.3% in 2011 (Table 8). These results suggest that more proactive measures are required to control obesity among students.

Table 7.

Prevalence of obesity according to relative weight from 2006 to 2011

Table 8.

Prevalence of severe obesity in 2001 and from 2006 to 2011

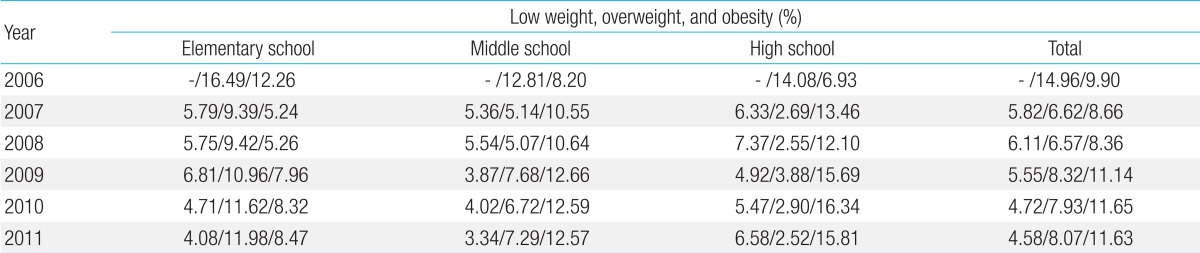

The prevalence of overweight and obesity based on body mass index increased from 6.6% and 8.7%, respectively, in 2007 to 8.1% and 11.6%, respectively, in 2011 (Table 9). The standard values for growth and development in children and adolescents was updated in 2007, so, the analysis on the results of 2006 was based on the previous standard values.

Table 9.

Prevalence of low weight, overweight, and obesity based on body mass index from 2006 to 2011

Low weight was defined as a value below the 5th percentile of body mass index, based on the standard values for growth and development in children and adolescents published in 2007. The assessment of the prevalence of low weight began in 2007. The prevalence of low weight changed from 5.8% in 2007 to 6.1% in 2008, 5.6% in 2009, 4.7% in 2010, and 4.6% in 2011 (Table 9). The relatively high percentages suggest that more attention should be paid to managing low weight in students.

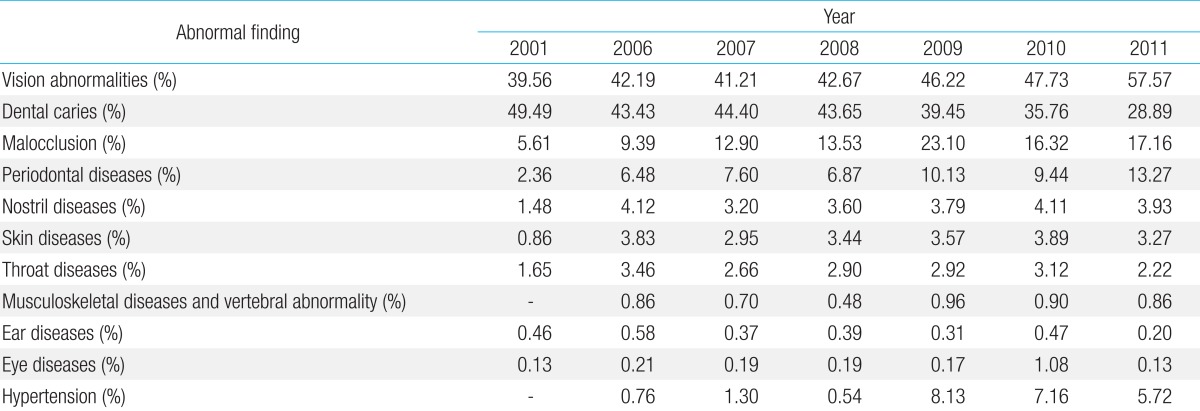

In order of prevalence, the following conditions were common in 2011: abnormal eyesight, oral diseases (dental caries, malocclusion, and periodontal diseases), nasal diseases, skin diseases, and throat diseases. The prevalence of abnormal eyesight was 39.6% in 2001, 42.2% in 2006, and 57.6% in 2011, indicating a dramatic increase in recent years. The prevalence of dental caries was 49.5% in 2001, 43.4% in 2006, and 28.9 % in 2011, showing a decrease in recent years. However, if malocclusion and periodontal diseases are included in oral diseases, the prevalence of oral diseases was 57.5% in 2001, 59.3% in 2006, and 59.3% in 2011, and ranked second in order of prevalence (Table 10).

Table 10.

Abnormal findings classified according to the affected organ in 2001 and from 2006 to 2011

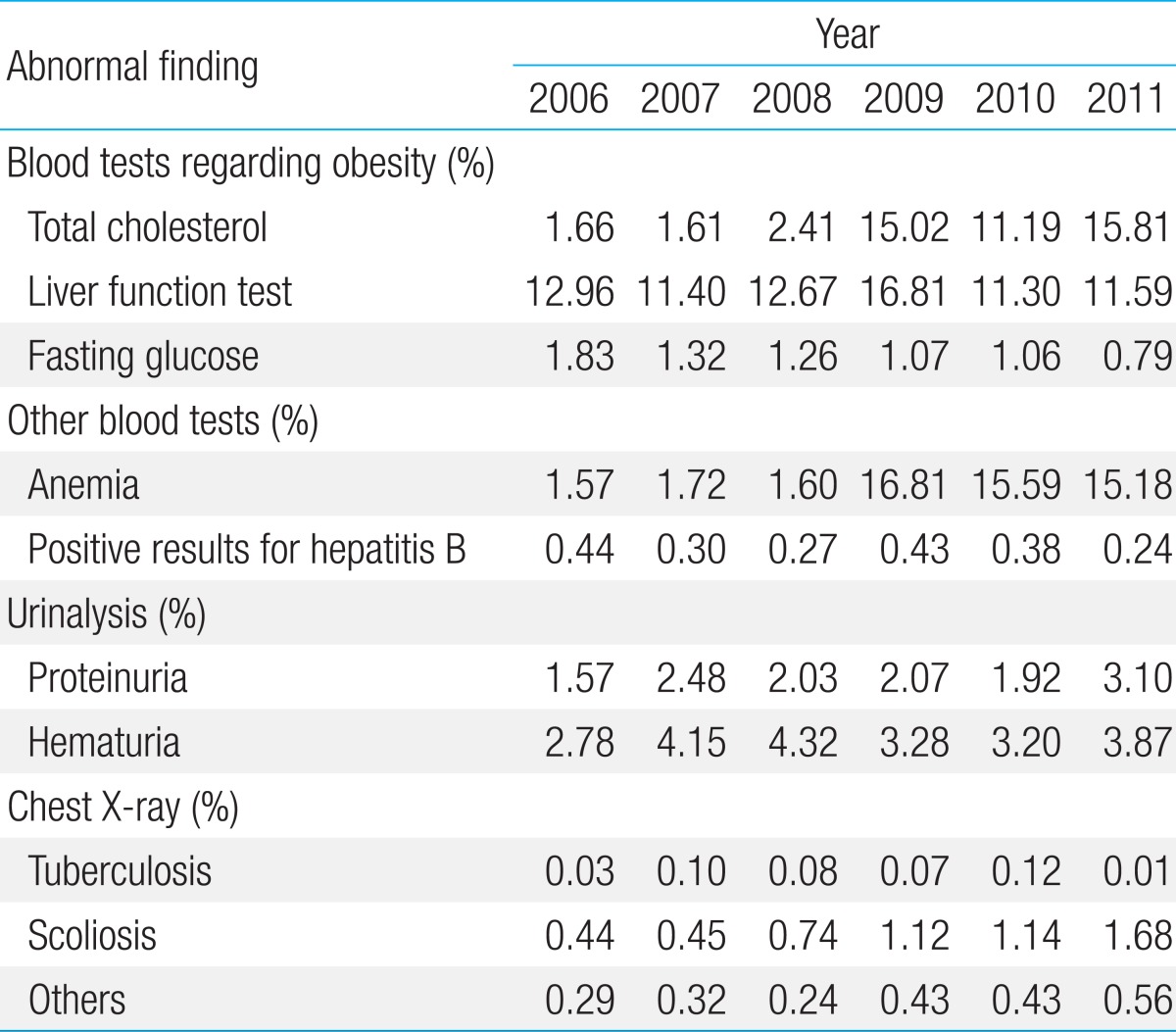

Blood test results of obese students in 2011 revealed that 15.8% of these students had elevated total cholesterol levels, 11.6% had elevated liver enzyme levels, and 0.8% had elevated fasting glucose levels (Table 11). The reasons for the increases in the prevalence of elevated total cholesterol levels and abnormal liver enzyme function initially observed in 2009 may relate to changes in the testing criteria. The criterion for elevated total cholesterol changed from ≥251 mg/dL before 2009 to ≥200 mg/dL or ≥95th percentile of the normal values beginning in 2009. The criteria for AST and ALT levels also changed from ≥51 IU/L and ≥46 IU/L, respectively, to an AST level >55 IU/L and an ALT level >45 IU/L for students <10 years of age, and >45 IU/L and 45 IU/L, respectively, for those >10 years of age. Therefore, careful observation for more years appears to be needed before drawing any conclusions regarding the abnormal blood test results of obese students.

Table 11.

Abnormal findings on laboratory and radiologic tests from 2006 to 2011

Blood pressure increased dramatically from 2009, and 5.7% of students had hypertension in 2011. This increase may be ascribed to changes in the criteria for the measurement of hypertension, from a systolic pressure ≥140 mmHg or a diastolic pressure ≥90 mmHg to a systolic/diastolic pressure that is >90th percentile of the normal values for gender, age, and height according to 2007 Korea Growth Charts (Table 10).

The prevalence of anemia among high school female freshmen was 16.8% in 2009, 15.6% in 2010, and 15.2% in 2011 (Table 11). The criterion for anemia changed from <10 g/dL of hemoglobin before 2009 to <12 g/dL after 2009. The apparent increase may simply reflect the change in the criterion for anemia. Therefore, the proportion of students showing hemoglobin levels <10 g/dL is likely to be low among the students diagnosed as having anemia based on the <12 g/dL criterion after 2009.

The prevalence of middle school freshmen who tested positive for the hepatitis B antigen was 0.4% in 2006 and 0.2% in 2011. The prevalence of abnormal urinalysis findings in 2011 was 7%. The prevalence of abnormal findings on chest radiographs in 2011 was 2.3%, and an increase in the prevalence of scoliosis was observed. Other abnormal findings on radiographs included non-tuberculosis disorders, cardiovascular disorders, and unknown diagnoses (Table 11).

Drawbacks and suggestions

Since 2006, the venue of SHE changed from schools to medical institutions. Despite high inspection rates and health education, the system underlying the SHE needs to be improved as does the review of health care, if it is to continue to yield valuable outcomes.

A previous study of the actual condition of the system, which proposed an improvement plan for SHE, was published in 2011. Based on a customer satisfaction survey that was aimed at parents and students, the study reported that the degree of satisfaction with the health survey items, medical examination items, and the program's progress was relatively high. This survey also indicated that 81.2% of the parents, 76.6% of the students, and 84.2% of the school nurses found the SHE system to be helpful in student health management. In addition, 63.2% of the school nurses responded that they had implemented school health activities to promote student health care projects based on the SHE results, thereby implying that SHE results were frequently utilized4).

The school nurses pointed out that a major difficulty with the SHE system is that medical institutions are located far away from schools. This problem needs to be resolved because the nurses consider the location of the medical institutions and the quality of medical examinations to be the most important features when selecting medical institutions.

Realistically, it is difficult to have each student visit medical institutions whenever he or she wishes throughout the year. The SHE system is based on patients visiting medical institutions individually, thereby minimizing absences from class and increasing the rates of inspection. It is necessary to find a method to improve the quality of screening examinations by minimizing absences from class and increasing the rates of inspection. Further, there is a clear requirement for a guideline on student medical examination items and for an indicative standard based on domestic data obtained from scientific evidence. A comprehensive overview of the health status of Korean adolescents has been published5), and a study by Lee et al.6) made recommendations for health examinations of children and adolescents. However, only limited data have been collected on the overall health examination system, the different inspection items, and school health care.

The World Health Organization Global School Health Initiative, launched in 1995, seeks to mobilize and strengthen health promotion and education activities at the local, national, regional, and global levels. The initiative is designed to improve the health of students, school personnel, families, and other members of the community through schools. Hence, there is a clear requirement to understand SHE in the context of providing school health care services. For example, the content of student medical examinations and health care services provided for each school grade varies in relation to different objectives and the type of organization.

The Bright Futures Project, started by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services in 2002, is a national health promotion initiative dedicated to the principle that optimal health involves trusting relationships between the health professional, the child, the family, and the community as partners in health practice. It advises clinicians to utilize health promotion guidelines at each age, taking into consideration the 6 key concepts that underlie primary care, namely, building relationships, conversation and communication, education, health promotion and prevention of diseases, time and scheduling, and public relations. It further describes the visit period and test items7).

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is an independent panel of nonfederal experts in preventive and evidence-based medicine and is composed of primary care providers. It conducts scientific reviews of evidence from a wide range of clinical preventive health care services and provides recommendations for primary care clinicians and health systems8). The recommendations made by the USPSTF for preventive health care services for adolescents are somewhat different from those proposed by the Bright Futures Project.

The Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) in England was founded to review children's basic health examinations. It published its recommendations in 1989 in the book "Health for All Children"9). The RCPCH then expanded its scope from conducting tests to diagnosing diseases and then to preventing diseases and promoting health. It also considered the recommendations from the UK National Screening Committee. These guidelines differ slightly from those issued in the US.

The Greig Health Record, endorsed by the College of Family Physicians of Canada and the Canadian Pediatric Society, is an evidence-based health promotion guide for clinicians caring for children and adolescents aged 6-17 years10). In Australia, guidelines are available for preventive activities in general practice for the primary care of high-risk patients and the general population11). These guidelines are slightly different from other guidelines.

The reason for each country and/or each guideline having different examination periods may be that each country and/or guideline has its own objectives and organizing committee, and that they consider the characteristics of their local communities. Therefore, evidence-based health examination items appropriate for Korean students are required, together with suitable enforcement periods and research on preventive health care services

It is necessary to provide the best follow-up service, compensate for weak points in our current follow-up service, and evaluate the quality of the service continuously. To review issues in detail and to establish plans for the future, data obtained from Korean students is required. Therefore, a follow-up system should be established. By conducting sample surveys, the numbers of abnormal findings on health examination can be counted; however, we cannot determine whether the diagnosis was confirmed or whether proper medical treatment was administered subsequently.

Previous studies have only reported follow-up examinations of students with abnormal urinalyses12,13). Therefore, a follow-up system should be established for all students with abnormal findings. Hence, individualized follow-up systems and improvements in the health examination test items are needed. Efficient information management systems should also be constructed to make the best use of the health examination results.

In the long-term, an information management system that interconnects the SHE results with student health surveys and other health-related statistical data is needed. This system will enable each school and school board to have access to a database that interconnects schools, local communities, and health services and will ensure that health examination results are used to establish school health policy. Furthermore, it will lessen the effort and expense needed to conduct sample surveys. Ultimately, this system will help to integrate all health examinations run by the government.

The weak points in managing the current SHE system need to be addressed. For example, there are no special conditions for disabled students. Indeed, school boards rarely have special conditions for disabled students. In addition, no data are available for inspection rates for disabled students. Therefore, specialized content and complementary measures for disabled students and minorities are urgently needed.

We need to find ways to support students from 1-parent families or 2-income families where a parent may not be available to accompany the student to medical institutions for the SHE. The SHE itself is run inflexibly, and committees or advisory organizations may be needed to manage the SHE more flexibly by considering local issues. Interest in the student health survey and school health care, and cooperation from the local community can be maximized by establishing connections between the school, health care professionals, and local communities.

Conclusions

Above all, SHE and student health education should be considered as tools to promote students' health. Every act implemented in a school should be of educational value and should promote school health; this is necessary if students are to enjoy their classes and school life and it is also an important part of education. The SHE is an important part of the study program where a student verifies his or her own health status, consults with medical staff to obtain medical advice, and improves his or her health; hence, it should be treated as a key part of school education. Therefore, it is necessary to find a way to use the SHE program and its content and processes directly in the school curriculum.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.Veselak KE. Historical steps in the development of the modern school health program. 1959. J Sch Health. 2001;71:369–372. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2001.tb03518.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chang CG. Development of school health system and projects in Korea from 1945 to 2010. J Korean Soc Sch Health. 2012;25:143–146. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Encyclopedia of Korean Culture. School health [Internet] Seongnam: The Academy of Korean Studies; [cited 2013 Mar 1]. Available from: http://encykorea.aks.ac.kr. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Song JC, Shin HJ, Kim IA, Kwon SC. Research on actual condition and improvement plan for SHE (sources of support for research: Daejeon Metropolitan office of Education) Daejeon: Daejeon Metropolitan office of Education; 2011. pp. 16–194. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee HK. Report about the health status of Korean adolescents: a comprehensive overview of the Korean adolescent health through demographics. Korean J Pediatr. 2006;49:1267–1274. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee CG, Ahn DH, Seo JW, Shin CH, Lim DH, Jung SH, et al. Systematic research for the development of the Korea National Health Screening and Promotion Program for Children and Adolescents. Seoul: Korean Pediatric Society; 2009. pp. 61–234. [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Academy of Pediatrics. Bright futures. 3rd ed. Elk Grove Village: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 8.U.S. Department of health and human services agency for healthcare research and quality. The guide to clinical preventive services 2010-2011. Recommendations of the U.S. preventive services task force. Rockville: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Royal College of Paediatrics and Child. Health for all children. 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2003. pp. 106–268. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Greig A, Constantin E, Carsley S, Cummings C. Preventive health care visits for children and adolescents aged six to 17 years: the Greig Health Record - Executive Summary. Paediatr Child Health. 2010;15:157–162. doi: 10.1093/pch/15.3.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Royal Australian College of General Practitioners; National Preventive and Community Medicine Committee. Guidelines for preventive activities in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2001;Spec No:S1i–S1xvi. S1-1–S1-61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chung SH, Park SS, Kim SD, Cho BS. The impact of early detection through school urinary screening tests of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis type. Korean J Pediatr. 2007;50:1104–1109. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yum MS, Yoon HS, Lee JH, Hahn H, Park YS. Follow-up of children with isolated microscopic hematuria detected in a mass school urine screening test. Korean J Pediatr. 2006;49:82–86. [Google Scholar]