Abstract

The methodology of health impact assessment (HIA) was introduced as one of four core themes for Phase IV (2003–2008) of the World Health Organization European Healthy Cities Network (WHO-EHCN). Four objectives for HIA were set at the beginning of the phase. We report on the results of the evaluation of introducing and implementing this methodology in cities from countries across Europe with widely differing economies and sociopolitical contexts. Two main sources of data were used: a general questionnaire designed for the Phase IV evaluation and the annual reporting template for 2007–2008. Sources of bias included the proportion of non-responders and the requirement to communicate in English. Main barriers to the introduction and implementation of HIA were a lack of skill, knowledge and experience of HIA, the newness of the concept, the lack of a legal basis for implementation and a lack of political support. Main facilitating factors were political support, training in HIA, collaboration with an academic/public health institution or local health agency, a pre-existing culture of intersectoral working, a supportive national policy context, access to WHO materials about or expertise in HIA and membership of the WHO-EHCN, HIA Sub-Network or a National Network. The majority of respondents did not feel that they had had the resources, knowledge or experience to achieve all of the objectives set for HIA in Phase IV. The cities that appear to have been most successful at introducing and implementing HIA had pre-existing experience of HIA, came from a country with a history of applying HIA, were HIA Sub-Network members or had made a commitment to implementing HIA during successive years of Phase IV. Although HIA was recognised as an important component of Healthy Cities’ work, the experience in the WHO-EHCN underscores the need for political buy-in, capacity building and adequate resourcing for the introduction and implementation of HIA to be successful.

Keywords: Health impact assessment, HIA, Health in All Policies, HiAP, Evaluation

Introduction

Health in All Policies (HiAP) is a strategic approach promoted by the European Union (EU) in which the impacts of non-health policies on health, through the determinants of health, are considered during the planning of policies, decision making about policy options and the design of implementation strategies.1 The methodology of health impact assessment (HIA) has been used as a mechanism to enable health implications to be taken into account during the policy-making process.1 In its conclusions on HiAP, the Council of the European Union urged the Commission, member states and the European Parliament to ensure the visibility and value of health in EU legislation and policies through, inter alia, HIA.2 Under the principle HiAP in the White Paper on health, the Commission of the European Communities promotes the use of impact assessment (IA) as a way of strengthening the integration of health concerns at community, member state and regional levels.3

In 1999, the WHO Regional Office for Europe defined HIA as:

“a combination of procedures, methods and tools by which a policy, program or project may be judged as to its potential effects on the health of a population and the distribution of effects within the population”.4

Thus, predictions are made about potential trends in determinants of health and health outcomes as a result of implementing a specific proposal by way of an analysis of its effects on the socio-economic as well as the biophysical or environmental determinants of health. The purpose in using HIA is to give politicians and other decision makers information about the likely effects on health and well-being of a specific proposal, and supporting that information with suggestions about how the proposal could be modified to optimise health gain through health protection, health improvement, and reducing health inequalities by working with the principle of equity.

Since the mid-1990s, there has been considerable interest in developing the use of HIA in different contexts within Europe: in the EU,5 within individual countries,6,7 at a regional level8,9 and in networks of cities, such as signatories to the Aalborg Commitments (application of HIA comes under Commitment 7).10 During phase III of the World Health Organization European Healthy Cities Network (WHO-EHCN; 1998–2002), the WHO European Office began work on the EU-funded PHASE Project to develop an HIA toolkit for use at a local government level throughout Europe. This product11 provided a foundation for the introduction of HIA in the WHO-EHCN during Phase IV (2003–2008).

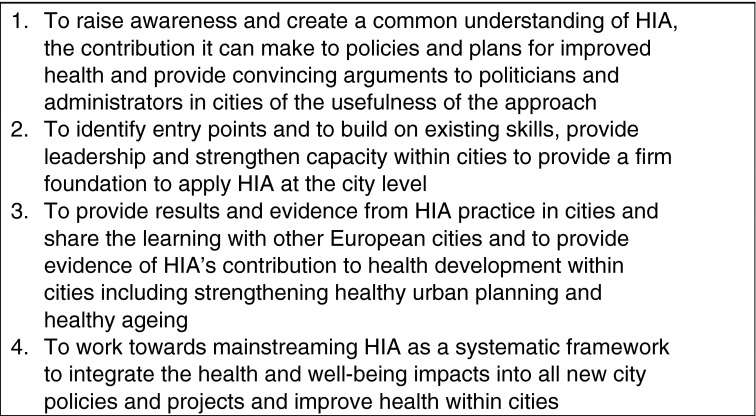

During Phase IV, each city was encouraged to work on at least one of four core themes—HIA, Healthy Urban Planning, Healthy Aging, Physical Activity and Active Living. Each core theme was supported by a Sub-Network of cities responsible for developing that theme on behalf of the WHO-EHCN. The HIA Sub-Network was led by Belfast Healthy Cities and supported by the Institute of Public Health in Ireland and an expert adviser in HIA (the author), who was engaged to provide training and develop aspects of the methodology for use at a local government level. The objectives set for HIA during Phase IV are shown in Box 1.

Box 1: Objectives for HIA during Phase IV of WHO European Healthy Cities

The purpose of this paper is to present the findings of implementing the HIA methodology at a local level in over 30 European countries with widely differing economies, and administrative and sociopolitical backgrounds. Although in recent years there have been evaluations of the effectiveness of HIA in incorporating a consideration of health into policy- or decision making,12–17 and evaluations of introducing HIA into a single country,18 to our knowledge, this is the first evaluation of the simultaneous introduction of HIA in a network of European cities. For cities which are signatories to the Aalborg Commitments, the first European-wide assessment of performance against all commitments was completed in 2010.

Methods

This was a qualitative study based on responses to two electronic surveys sent to the 77 cities designated during Phase IV of the WHO-EHCN: a General Evaluation Questionnaire and the 2007–2008 annual reporting template (ART). Analysis of both sets of responses was supplemented with information submitted by cities in the HIA Sub-Network and information from five of the WHO European Regional and National Networks (Baltic Sea Region, French-speaking, Portuguese, Swedish and Spanish).

Phase IV General Evaluation Questionnaire

Four questions on HIA developed by the HIA Sub-Network were included in the Phase IV General Evaluation Questionnaire.

What were the key challenges for introducing HIA into your city?

Which of the Phase IV objectives for HIA did you have the resources, knowledge and/or experience to achieve?

What were the facilitative factors and obstacles in implementing HIA in your city?

What were the key successes of introducing HIA into your city?

Annual Reporting Template

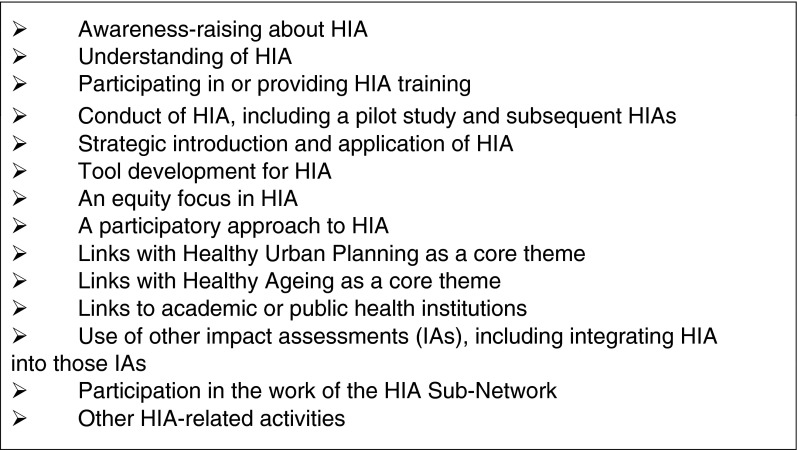

Developed in 2000 from a model known as MARI (monitoring, accountability, reporting and indicators),19 the ART is a mechanism for evaluating the activity of Healthy Cities. Questions about HIA were introduced into the ART for the first reporting cycle of Phase IV. The HIA expert adviser developed 14 criteria against which responses to ART about HIA were assessed (see Box 2). An evaluation of cities’ HIA activity was undertaken for every year of Phase IV.

Box 2: Criteria for evaluation of responses about HIA on ART

Sources of Bias

The main sources of bias in this evaluation were the number of non-responders to the Phase IV General Evaluation Questionnaire and to the ART for 2007–2008, the additional number of non-responders to the questions on HIA and the requirement to communicate in English. For many respondents, English was not their first language, and questions and/or responses could have been misinterpreted. People may not have been able to articulate the nuances of experience in their city. The potential for misinterpretation was compounded by the lack of a mechanism through which evaluators could check the content of questionnaire responses with respondents.

Results

Phase IV Evaluation Questionnaire

Three quarters (n = 58) of the designated Healthy Cities responded to the Phase IV General Evaluation Questionnaire. The number of responses to the questions about HIA varied between 41 and 56.

Question 1: Key Challenges

Fifty-six cities responded about the key challenges to implementing HIA. Ten respondents did not identify any specific challenges, and two cited no major challenges due to a long history of HIA or intersectoral work in their city. Two respondents reported that implementation was challenging but did not state why. Of those cities reporting challenges, over two thirds (29/41) identified more than one.

The most frequently cited challenges were a lack of history and knowledge of, and expertise or experience in, conducting HIA (n = 8), the lack of a legal basis for HIA implementation (n = 7 from 6 countries), the newness of the concept/methodology, which meant that time was required to build capacity (n = 6), and a lack of political (n = 6) or professional (n = 5) support due to scepticism, caution, resistance, lack of readiness, cultural barriers or the hierarchical structure of the organisation. Other challenges were limited skills in (n = 2), knowledge of (n = 2) or capacity for (n = 2) HIA and a lack of resources (unspecified n = 2; financial n = 4; human n = 2). Two relatively experienced respondents described the challenges of assimilating the process of HIA in the municipality after its initial implementation in terms of the resources, capacity, expertise and stakeholder engagement required.

Question 2: Achieving the Objectives for HIA in Phase IV

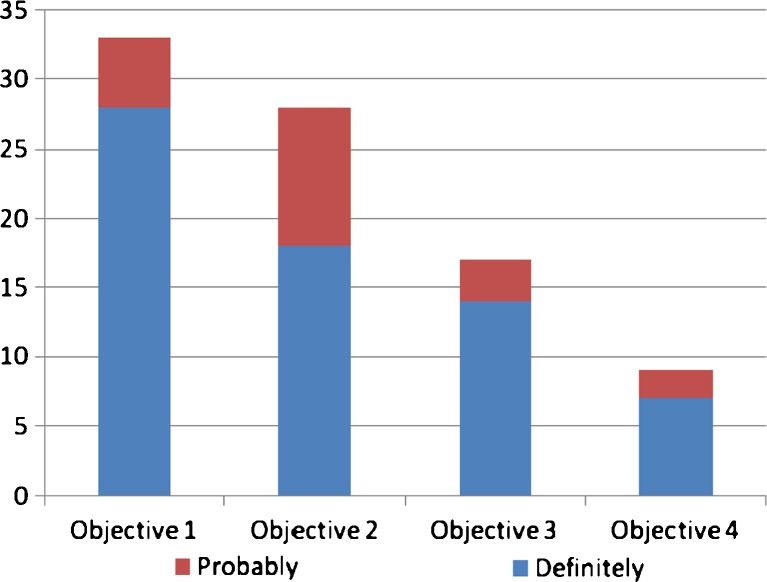

Forty-seven cities responded about achieving the objectives set for HIA during Phase IV. These responses presented difficulties in analysis, which could reflect differences in the cities’ level of awareness of the objectives. Only a few cities answered the question fully: some responded in terms of resources, knowledge and/or experience; others replied in terms of meeting the objectives. In some cases, the responses appeared to encompass work on other core themes or deal with population health status in general. The expert adviser triangulated answers to this question with information given in response to the other questions on HIA or to the ART. Achievements in relation to the HIA objectives are summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Cities achieving the HIA objectives for Phase IV.

Thirty-three cities definitely (28) or probably (5) fulfilled Objective 1 and raised awareness of HIA, creating a common understanding. Fewer cities were able to achieve Objectives 2, 3 and 4. Only seven cities appear to have achieved Objective 4, mainstreaming HIA, and at least two others may have done so. Of the cities able to work on one or more of the objectives, 18 appear to have had sufficient resources, 15 had sufficient knowledge and 12 had sufficient experience. At least seven cities had sufficient resources, knowledge and experience combined, although for some cities the availability of one or more of these factors varied during Phase IV, particularly financial and human resources.

Question 3: Facilitative Factors for and Obstacles to Implementing HIA

Fifty-one cities responded about the facilitating factors for and the obstacles/barriers to implementing HIA. Twenty-nine cities identified more than one facilitating factor, and seven of these cities identified four or more. Fifteen cities identified more than one barrier to implementing HIA, and one of these cities identified as many as four barriers.

The two most frequently cited facilitating factors (n = 9 in both cases) were political support and training in HIA. Next was collaboration with either an academic or public health institution (n = 6) or a local health agency (n = 2). Other facilitating factors were the resources provided by WHO and the HIA Sub-Network in the form of documents (n = 4) or access to/working with the expert adviser (n = 3). A pre-existing culture of intersectoral working helped (n = 4), as did a national policy context that encouraged the use of HIA (n = 3). Other facilitating factors were membership of a network (whether the HIA Sub-Network (n = 2), a National Network or the WHO-EHCN (n = 2)) and a willingness or interest on behalf of politicians and technicians to be involved with HIA implementation (n = 3). For the two most experienced cities, they both cited a dedicated post in HIA and experience of working on HIA during phase III as facilitating factors.

The most frequently cited barrier to implementing HIA was a lack of knowledge (n = 6), followed by a lack of understanding of what HIA can offer (n = 4). Other barriers included the lack of a legislative basis for HIA (n = 3), a lack of political support (n = 2) and a lack of skilled personnel/experts in HIA (n = 2). Competing demands on resources due to the need to conduct other IAs (n = 2) and a lack of training or of willingness to participate in training (n = 2) were also cited as barriers, as was the perceived complexity of HIA, especially in a local government context (n = 2). The two most experienced respondents mentioned the lack of capacity to respond to all requests for HIAs as a barrier.

Question 4. Key Successes

Of 46 responses to the question about key successes when introducing HIA, only 27 cities identified successes. Twenty-one cities identified more than one success (over a quarter of the whole WHO-EHCN): ten cities reported two successes, five cities cited three, and four cities identified four successes. However, the two most experienced cities identified seven and ten successes, respectively. Although the successes were diverse in nature, most of them related to the HIA process (n = 13), including conducting a pilot HIA (n = 5), undertaking more than one HIA (n = 4), developing the city’s HIA activity from piloting to mainstreaming HIA in one sector of work (n = 1), mainstreaming the use of a locally developed HIA tool (n = 1) and applying HIA (or HIA integrated into another IA) to all major proposals, e.g. planning policies or major built developments (n = 2).

Respondents reported as a success the effect of conducting HIA on decision making. The use of HIA had influenced decision making about proposals important to the municipality (n = 3), e.g. a Sustainable Development Plan or Housing Strategy, or had led to the uptake of specific suggestions from the HIA thereby changing individual proposals at a local (n = 2) or national level (n = 1). HIA was seen to improve the decision-making process: it was “better informed”, and HIA had added value (n = 2), or brought transparency to the process (n = 2), especially important when there was conflict about a proposal (n = 1).

Other successes related to building capacity for HIA: the provision of and participation in HIA training (n = 4), raising awareness of HIA among politicians and technicians (n = 3), and developing stakeholder consultation (n = 2), including community participation (n = 1). Integrating a concern for health or HIA into another IA or appraisal (e.g. strategic environmental assessment, sustainability appraisal or integrated IA; n = 3) was also cited as a success.

Finally, five respondents commented that the introduction of HIA had strengthened intersectoral working in the municipality. For two respondents, HIA was instrumental in putting health and/or the methodology on the agenda of other organisations (n = 2), even to the extent that partner organisations in one city would be attempting to mainstream HIA themselves. For two HIA Sub-Network members, one of the successes was teaching HIA at their city’s university.

Information on HIA Activity from ART

Of 77 Network Cities, 62 responded to ART 2007–2008; of these, 51 answered questions on HIA (66.23% of Healthy Cities and 82.25% of ART respondents). During 2007–2008, the majority of cities responding about HIA on ART (44/51; 86%) undertook some activity relating to HIA, which represents over half the cities in the WHO-EHCN. One quarter of these were judged most active in HIA through addressing five or more of the HIA evaluation criteria.

Just over two fifths of cities (21/51; 41.17%) raised awareness and increased the level of understanding of HIA in the municipality, a greater number than in the previous year. One third (17/51; 33.3%) were actively involved in HIA training: attending courses or by giving training to politicians and technicians in the municipality and/or to partner organisations. HIA training had declined when compared with the previous year, possibly reflecting reduced need after relatively high levels of training in previous years.

Almost two fifths of cities (19/51; 37.25%) had conducted or were in the process of undertaking at least one HIA, and seven cities had completed more than one, representing an increase in activity compared with the previous year. The range of proposals investigated was broad but with an emphasis on redevelopment and spatial planning. Over one quarter of cities (14/51; 27.45%) took a strategic approach to the introduction and/or implementation of HIA, a slight decline over the previous year.

Seven cities (13.72%) had developed either the HIA methodology or tools (the same number as in the previous 2 years), six of which were UK or Scandinavian cities. Six cities (11.76%) had an explicit focus on equity in HIA, all of which were UK or Scandinavian cities—a slight increase on previous years. Over one third of cities (18/51; 35.29%) had taken a participatory approach to HIA, in its planning or application, a sign that a growing number of cities were involving relevant stakeholders in HIA, including the community.

Over one quarter of cities (14/51; 27.45%) made links between HIA and Healthy Urban Planning, a growing trend during Phase IV, especially in UK and Scandinavian cities. However, only two cities (3.9%) made links between HIA and Healthy Aging, and only one city made a link between HIA and Physical Activity and Active Living.

Almost one third of cities (15/51; 29.41%) made links with academic and/or public health institutions to take HIA forward, another trend that developed during Phase IV, and some cities were able to make links with more than one institution.

Just over one fifth of cities (11/51; 21.56%) integrated HIA or a concern for health into a range of other IAs and appraisals—strategic environmental assessment, environmental IA, integrated IA, human IA, gender IA and sustainability appraisal—representing an increase in such activity over the previous year.

Five cities (9.8%) were active HIA Sub-Network members (the same as in the previous year). About one sixth of cities (10/51; 17.64%) were involved in other HIA-related activities, such as running national or international HIA conferences, setting up regional HIA networks or using HIA as an indicator of good management practice, representing a slight decline in such activities over the previous year.

Discussion

The majority of cities were able to meet Objective 1 for HIA during Phase IV of the WHO-EHCN, i.e. raising awareness and increasing understanding of HIA. By 2006–2007, the level of understanding in the WHO-EHCN was quite high (despite a small number of respondents to ART whose understanding appeared to be incomplete). However, far fewer cities were able to meet the more demanding Objectives 2–4 (see Figure 1), probably because these activities require not only greater investment of time and resources but also changes to the prevailing culture, ways of working and, in some cases, structural organization in the municipality. In the absence of any or all of these factors, there may be barriers to implementation.

Some of the barriers to introducing and implementing HIA in the WHO-EHCN appear to be the same or similar to barriers to the use of HIA in decision making identified in the literature: the lack of a statutory or policy requirement for HIA,12,13,17,20 a lack of support from decision makers, including politicians,12,14 a lack of joint or intersectoral working,13,16 difficulties in integrating HIA into existing organizational structures13 and a lack of resources.12

In an independent evaluation of the HIA work in Helsingborg Healthy Cities,20 Halling found that the need to explain and clarify the purpose of HIA was a pre-requisite for successful implementation because confidence in the methodology was necessary before people were prepared to invest resources in it and before politicians had the courage to use the results.

The importance of familiarity with and confidence in the HIA methodology was underlined by analysis of ART. Cities that were able to address five or more of the HIA evaluation criteria for ART throughout Phase IV tended to be in the HIA Sub-Network or from the UK or Scandinavia. However, in 2007–2008, the proportion of cities not belonging to one or both of these categories did increase to almost half. Nonetheless, of the top five performing cities in 2007–2008, four are from the UK and three are in the HIA Sub-Network. For the last 3 years of ART evaluation, the two most outstanding cities have been Belfast, lead city for the HIA Sub-Network, and Liverpool, a city at the forefront of introducing HIA into the UK. This finding is supported by the Europe-wide study of Ollila et al.,1 in which work on HIA was noted as being strongest in the UK.

Responses to both questionnaires demonstrate that the cities most successful at implementing HIA during Phase IV had previous experience of HIA, came from a country with a history of HIA work or made a significant commitment to HIA for several years in succession. In general, facilitating factors to the introduction and implementation of HIA in the WHO-EHCN were the converse of the barriers: political support, HIA training and skills development, links with an academic/public health institution, collaboration with a local health agency, access to HIA expertise and materials, previous experience of HIA, membership of a network, pre-existing culture of intersectoral working and a supportive national policy context. Some of these facilitating factors are the same or similar to those identified in other studies of the use of HIA in decision making: training and skills development,6 intersectoral working,12,13,16 repeated use or experience of HIA17 and a supportive policy environment.12,13

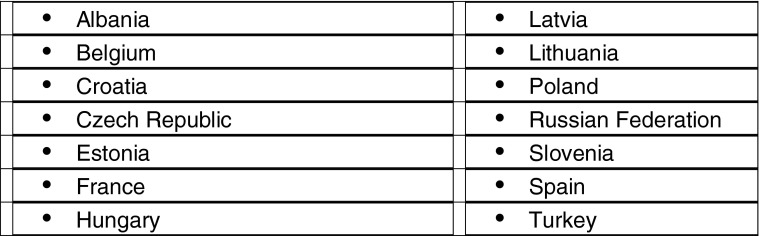

For many respondents, HIA was a relatively new concept and perceived as a complex methodology, not just for the city but in the country as a whole (see Box 3). Thus, there was a lack of information about the methodology in the native language, of case studies to draw upon, of experts and academic/public health institutions where the methodology is studied or taught and no or limited support for HIA at a national or regional government level.

Given this background, together with the lack of a statutory requirement for HIA, it is remarkable what many cities achieved in a relatively short space of time, particularly in terms of training and skills development, planning and performing HIA using a participatory approach and influencing decision making to improve health. Owing to the introduction of HIA in Phase IV, some Healthy Cities lobbied governments at a regional (Italy), federal (Switzerland) or national level (France and Lithuania) to adopt an HIA approach. Lobbying was particularly successful in Switzerland: in 2008, the federal health authorities sponsored a new law on prevention that introduced HIA.

Box 3: European countries with Healthy Cities where HIA was a concept at the beginning of Phase IV

Bekker14 has argued that for HIA to be effective in integrating health into public policy making, it is necessary to redesign HIA. She challenges the WHO European Office definition of HIA,4 identifying several problems including that it carries “connotations of putting a policy to the test rather than optimising that policy”.14 This thesis deserves consideration and could be one reason why it is difficult to introduce and implement HIA in local government. It is noticeable that some Healthy Cities have been exploring ways of adapting HIA to their needs, making it fit for purpose, which may coincide with Bekker’s concept of “redesign”. Milner has made a similar suggestion about the need to adapt HIA to the working environment of local government using theories of organisational development.21

In Banken’s analysis of institutionalising HIA,22 he promotes a model of HIA whereby non-health actors produce public health knowledge for use by decision makers, requiring knowledge transfer from public health but supported by public health quality control to ensure that HIA does not become a symbolic function lacking effectiveness in the real world. This model would appear to be suitable for application in local government, and some Healthy Cities seem to have developed the necessary foundations for institutionalising HIA during Phase IV.

Conclusion

Although there is undoubtedly scope for the redesign or adaptation of HIA, it is important not to lose sight of the gains already made from introducing and implementing HIA highlighted in this and other evaluations, e.g. improving understanding of health (particularly the social model) and the determinants of health,16,17 putting health on the agenda of policy- and decision makers,14,16 initiating or improving intersectoral working on health16,17 and influencing decision making about proposals.16 Furthermore, it is vital to ensure that the learning points from HIA are taken forward in the drive to integrate a concern for health in policy- and decision making. During phase V (2009–2013), the overarching goal is “Health and Health Equity in All Local Policies”, and Healthy Cities are expected to address systematically the health impacts of policies and strategies, as well as health inequalities, social inclusion and the needs of disadvantaged and vulnerable groups.23 The HIA methodology can support cities in realizing this vision.

Acknowledgements

Elisabeth Bengtsson of Helsingborg Healthy Cities, Terry Blair-Stevens of Brighton & Hove Healthy Cities, Joan Devlin of Belfast Healthy Cities, Heini Parkkunen of Turku Healthy Cities and Jean Simos of the HIA Unit at the University of Geneva all made valuable comments on this paper, for which I am grateful.

References

- 1.Ståhl T, Wismar M, Ollila E Lahtinen E, Leppo K (eds) Health in All Policies: prospects and potentials. Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland and European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies, Helsinki, 2006. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_information/documents/health_in_all_policies.pdf. Accessed on: May 15, 2012.

- 2.Council of the European Union. Council Conclusions on Health in All Policies (HiAP). 2767th Employment, Social Policy, Health, and Consumer Affairs Council meeting. Brussels: Council of the European Union; 2006. Available at: http://www.consilium.europa.eu/ueDocs/cms_Data/docs/pressData/en/lsa/91929.pdf. Accessed on: May 15, 2012.

- 3.Commission of the European Communities. Together for Health: a strategic approach for the EU 2008–2013. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities; 2007. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/health/ph_overview/Documents/strategy_wp_en.pdf. Accessed on: May 15, 2012.

- 4.Health Impact Assessment: main concepts and suggested approach. Gothenburg Consensus Paper. Brussels: World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hubel M, Hedin A. Developing health impact assessment in the European Union. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(6):463–464. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lock K, Gabrijelcic-Blenkus M, Martuzzi M, et al. Health impact assessment of agriculture and food policies: lessons learnt from the Republic of Slovenia. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81(6):391–398. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Healthy without care. Report to the Minister of Health, Welfare and Sport. Zoetermeer: Council for Public Health and Health Care; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Breeze C, Hall R. Health impact assessment in government policymaking: developments in Wales. World Health Organization Europe, EHCP Policy Learning Curve, 2001.

- 9.Key messages from Health Impact Assessments on Mayor of London Draft Strategies. London: London Health Commission; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Aalborg Commitments. Available at: http://www.aalborgplus10.dk/default.aspx?m=2&i=307. Accessed on: July 30, 2008.

- 11.Ison E. The introduction of health impact assessment in the WHO European Healthy Cities Network. Heal Promot Int. 2009;24(Sl):si64–si71. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davenport C, Mathers J, Parry J. Use of health impact assessment in incorporating health considerations in decision making. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2006;60:196–201. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.040105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ahmad B, Chappel D, Pless-Mulloli T, White M. Enabling factors and barriers for the use of health impact assessment in decision-making processes. Public Health. 2008;122(5):452–457. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bekker M. The politics of healthy policies. Redesigning Health Impact Assessment to integrate health in public policy. Eburon: Delft; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wismar M, Blau J, Ernst K, Figueras J (editors) The effectiveness of health impact assessment. Scope and limitations of supporting decision-making in Europe. Brussels:The European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies; 2007

- 16.Findlay G. (ed) Health Inequalities and Equality Impact Assessment of ‘Health Care for London: Consulting the Capital.’ London: London Health Commission; 2008. Available at: http://www.london.gov.uk/lhc/docs/publications/hia/healthcareforlondon/hfl_hiia_eqia_FinalReport.pdf. Accessed on: May 15, 2012.

- 17.Cost Benefit Analysis of Health Impact Assessment. Final Report. Heslington: York Health Economics Consortium for the Department of Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mannheimer LN, Gulis G, Lehto J, Ostlin P. Introducing Health Impact Assessment: an analysis of political and administrative intersectoral working methods. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17(5):526–531. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckl267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Leeuw E. Evidence for Healthy Cities: reflections on practice, method and theory. Heal Promot Int. 2009;24(Sl):si19–si36. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dap052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halling C. Health Impact Assessment in Helsingborg. A follow up of the local community’s work with Health Impact Assessments. Lund: Department of Social Medicine and Global Health, Lund University; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milner SJ. Using HIA in local government. In: Kemm J, Parry J, Palmer S, editors. Health Impact Assessment. Concepts, theory, techniques, and application. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banken R. Strategies for Institutionalizing HIA. European Centre for Health Policy (ECHP) Health Impact Assessment Discussion Papers Number 1. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Official Call for Expressions of Interest to Phase V (2009–2013) of the WHO Healthy Cities Network in Europe. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2008. [Google Scholar]