Abstract

This article summarizes how members of the European Healthy Cities Network have applied the ‘healthy ageing’ approach developed by the World Health Organization in their influential report on Active Ageing. Network Cities can be regarded as social laboratories testing how municipal strategies and interventions can help maintain the health and independence which characterise older people of the third age. Evidence of the orientation and scope of city interventions is derived from a series of Healthy Ageing Sub-Network symposia but principally from responses by 59 member cities to a General Evaluation Questionnaire covering Phase IV (2003–2008) of the Network. Cities elaborated four aspects of healthy ageing (a) raising awareness of older people as a resource to society (b) personal and community empowerment (c) access to the full range of services, and (d) supportive physical and social environments. In conclusion, the key message is that by applying healthy ageing strategies to programmes and plans in many sectors, city governments can potentially compress the fourth age of ‘decrepitude and dependence’ and expand the third age of ‘achievement and independence’ with more older people contributing to the social and economic life of a city.

Keywords: Healthy cities, Healthy ageing, Third age, Age-friendly, Supportive environments

Introduction

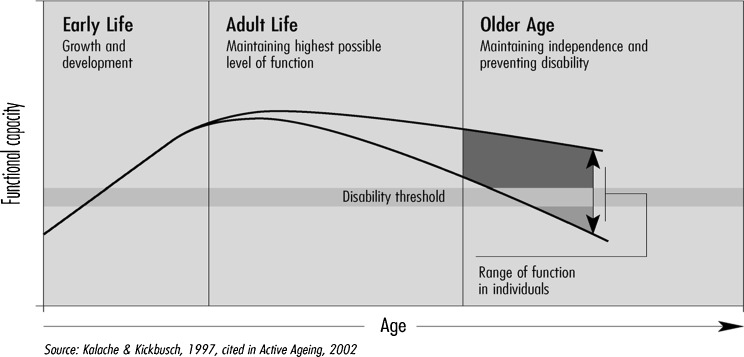

This article summarizes how member cities of the WHO European Healthy Cities Network (WHO-EHCN) are countering orthodox perspectives of global ageing as a ‘demographic time bomb’ likely to impact negatively both on sustainable economic development and demand for health and social support services.1 An alternative policy framework, breaking the tie between age and dependency, is provided by Active Ageing published by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 20022 for the Second United Nations World Assembly in Madrid. Central to the concept of ‘Active’ or ‘Healthy’ ageing is a life-course approach which maintains that early and middle-life interventions can reduce levels of disability in older age (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Life-course approach which maintains that early and middle-life interventions can reduce levels of disability in older age.

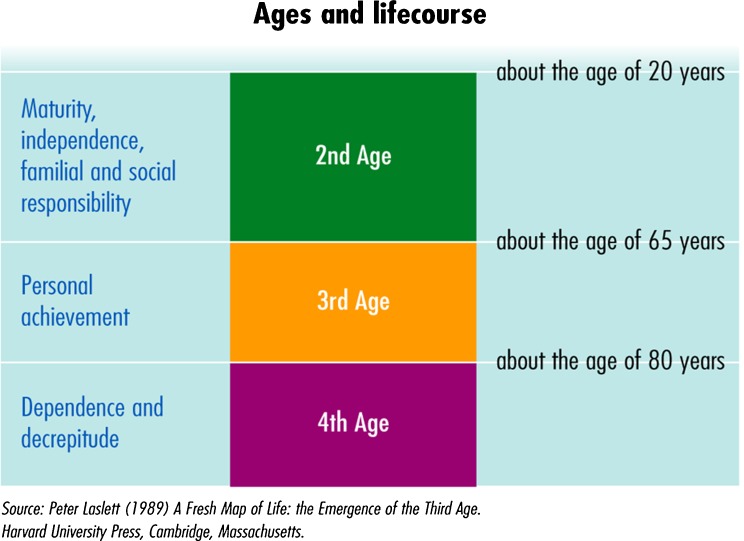

Equally important is the related concept of a third age. According to Laslett,3 this is the age of personal achievement and independence following retirement from formal work but before the onset of ‘dependence and decrepitude’ which characterises the fourth age (Figure 2). Only in the last 50 years, mainly in developed economies, has a significant proportion of older people survived into the third age. They have achieved this status primarily because of an ‘epidemiological transformation’ that has displaced as the principle causes of mortality, communicable diseases such as cholera, diphtheria and influenza with non-communicable diseases such as cancer and heart disease.4 There are significant policy implications. Whereas death could follow infectious disease within days, non-communicable diseases are often much longer term conditions, to be prevented or managed by improving personal ‘lifestyles.’ Though Active Ageing emphasizes early intervention, effectively in the second age, it is difficult, conceptually and practically, to dilute a policy focus on older people by also embracing upcoming, younger population cohorts. Equally, it is difficult to extend an Active Ageing approach to the irredeemably unhealthy and dependent population of the fourth age.5 The focus of this review therefore, is on strategies, policies, programmes and interventions to enhance the lives of older people in the third age.

Figure 2.

Ages and lifecourse.

A city focus on healthy ageing is appropriate not merely because they are home to large numbers of older people, but primarily because city governments have competences for influencing both distal and proximal determinants of health.6,7 Traditionally responsible for social services and for regulating living and working conditions in most European states,8 their highly developed civic institutions can also shape a social and physical environment which encourages healthy ‘lifestyles.’ This was the rational for selecting Healthy Ageing as one of the three core themes of Phase IV of the WHO-EHCN. Member cities, especially those recruited to the Healthy Ageing Sub-Network can be regarded as laboratories for finding and implementing solutions, to benefit their local communities and to disseminate innovation to other European cities and the wider public health community.

Methods

The objective of this review is modest; to describe and assess the activity of member cities in relation to four aspects of healthy ageing given priority in Phase IV of the WHO Healthy Cities Network of 77 cities, and providing a framework for the Healthy Ageing Sub-Network of 19 cities. The principal source of data is responses is the General Evaluation Questionnaire (GEQ) which—inter alia—matches the four priorities with four specific questions about how or to what extent did cities (a) raise the profile of their older people at a strategic level and across all sectors of, (b) empower them to control their personal lives and influence decisions affecting their community, (c) support older people with age-friendly environments, and (d) increase their access to a full range of public and private services in the city?

Supplementary data was elicited from the Annual Reporting Templates (ARTs) which cities complete regularly as members of the Network. Sixty city responses to both the GEQ and the 2007–2008 ART summarized briefly over 1,000 actions, interventions, strategies or products. It was not possible to measure their impact but from the range of GEQ responses it is possible to give an indication of focus and balance of city activity in relation to the four priorities. Greater depth and dynamic is elicited from reports of the seven Sub-Network meetings during Phase IV, together with theoretical papers, case studies, guidance and evaluations presented or developed at these meetings. Throughout this process of realist synthesis, Pawson and associates recommend a healthy two-way dialogue with the policy community, from the initial expert framing of the problem to their final judgment on what works.9 In this sense, each meeting was a symposium of city ‘laboratories’ and this review refers to how the Sub-Network process contributed evidence.

Results

Raising Awareness

Raising awareness of the status and role of older citizens is a necessary prelude to strategies and plans to enhance our lives. A healthy ageing approach requires a profile different from the traditional emphasis on illness, dependency and mortality associated with the fourth age. To dispel these negative perceptions, equal weight should be given to positive features which characterise the third age, and the wider determinants of health and independence.

This commitment to a ‘positive and dynamic’ model for profiling older people in cities was made at the inaugural meeting of the Healthy Ageing Sub-Network in Stockholm in 2005.10 There are three parts—(a) who and where are older people? (b) health and social care, and (c) older people in a developing city. The first two elements build upon traditional ways of profiling older people—basic demography, morbidity, mortality and access to services and support. The third dynamic element, the ‘social picture,’ relates to the determinants of health (such as income and social position, housing and the environment) and the life-course approach. Cities were also recommended to measure positive features of ageing such as older people as a resource, participating in civic and family life. Belfast Healthy Cities recommended a list of 72 indicators to measure these dimensions, which were reduced to a more manageable 22 at the third Sub-Network Meeting in Brighton in 2006.11

Over the next 3 years, with Rijeka and Liégè in the vanguard, nearly all of the 19 cities in the Sub-Network had produced older peoples’ profiles using either the Belfast or Brighton forms of WHO guidance (Table 1). During the period 2007–8, the number of other city profiles doubled to 14. A case study from Lodz12 describes the production process, with EU funds used to commission a survey from the Faculty of Sociology of the University of Lodz.

Table 1.

Healthy ageing profiles

| Produced a healthy ageing profile? | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-Network member? | Yes | Planned | No |

| Yes | 17 | 1 | 1 |

| No | 14 | 3 | 31 |

| TOTAL | 31 | 4 | 32 |

A limited evaluation of the impact of the first seven completed profiles was undertaken by Gianna Zamaro in 2007.13 Responding to short questionnaire, sub-Network cities revealed wide differences in the dissemination of profiles, with Liégè and Vienna initially finding it difficult to obtain political support for publication, whereas 200 of 500 of Rijeka’s polished report were distributed within the municipality and 150 to local NGOs. Responding to questions on impact, the majority had (a) presented to or discussed the profile with opinion leaders, politicians and citizens, and raised awareness (b) of population ageing in their city and (c) the concept of active ageing. GEQ responses confirm the political impact of the profile in Belfast and how it enabled Brno ‘to demonstrate that the activities of departments like culture and transportation are important for seniors’ quality of life.’

A quarter of cities responding to the GEQ refer to policies or strategies which raise awareness of older people and responded to their concerns. Most of these refer specifically to policies for older people. Examples are Copenhagen’s ‘Policy for the Elderly’ and Brighton’s ‘Older Person’s Services Strategy.’ Others have embedded older people’s priorities within more generic plans. Athens refers to their policy for the elderly as one of the core themes of the Municipal Strategy; for Liverpool, ‘healthy ageing’ is a key objective of the city’s ‘Sustainable Community Strategy.’ Brno, Posnan and Sandnes reveal greater priority for older people in updating their overarching ‘City Development Plans.’ All these documents signal some level of institutional support for a healthy ageing approach, highlighted for example by inter-departmental and interagency collaboration in Belfast and Dresden. Though some cities responses refer to traditional priorities for health and social services in response to demographic changes, more highlight the commitment of departments and agencies responsible for the ‘dynamic’ determinants referred to earlier. For example, Barcelona refers to departments responsible for ‘sports, housing, participation and leisure activities as well as social and health care.’ Izhevsk refers to commitments from municipal departments responsible for transport, architecture, culture, housing and urban planning.

A quarter of GEQ responses identify older people as a resource to society. According to Udine, they are ‘a precious resource for the community…and their contribution should be recognized and appreciated.’ Copenhagen’s vision of the good life of older people is ‘where society is aware of the resources and experience they possess and makes use of it in their work life, as volunteers and in families.’ Milan, Udine and Helsingborg are the only other cities to refer to older people’s contribution to work in the formal economy, and only then to signal the absence of proper acknowledgement. Most other responses focus on either intergenerational support to family members or volunteering within the wider community. Both Horsens and Copenhagen have strategies to encourage volunteering. Vitoria-Gasteiz refers to ‘intergenerational solidarity.’ Cankaya highlights the tradition of mutual family support in Turkish society where ’older people are always admired and respected by the younger generation.’ Sant Andreu de la Barca regards their ‘contribution to society’ as looking after their own health so they are better able look after their grandchildren. Østfold reports older people ‘active helping both old people and young people.’ Siexal provides a comprehensive summary; ‘We believe our elderly are empowered through their associative capacity, their participation in community life, involvement in cross-generational projects and taking a public stance on matters of local interest.’

Empowerment

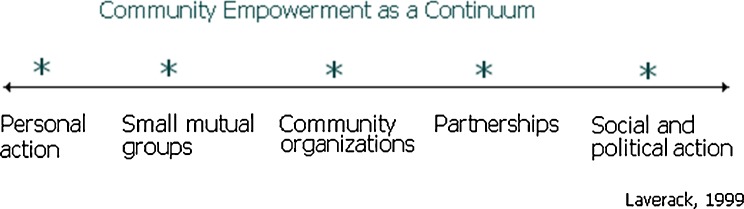

The concept and general practice of community empowerment is reviewed by Dooris and Heritage in their article for this special edition. They address generic questions of empowerment which have evolved over all four Phases of the WHO European Healthy Cities Network. However, the Phase IV GEQ also asked a specific question about the empowerment of older people. An alternative theoretical model to Davidson’s ‘Wheel of Participation’14 was provided by Laverack, in a WHO working paper on ‘Empowering Older People’ presented to a Sub-Network meeting in Brighton in 2006.15 Based on his earlier work,16,17 he identified empowerment as a continuum ranging from personal action to more collective forms of community action (Figure 3). The empowerment of older people offers the opportunity for individuals to build ‘power-from-within’ and for ‘communities of interest’ to collectively gain more access to the decisions and resources that influence their health and its determinants.

Figure 3.

Community empowerment as a continuum.

Though personal empowerment tends to dominate the international literature on health promotion and ageing, only a fifth of responses to the GEQ refer to this end point of the continuum. Vienna and Helsingborg are the most comprehensive. Vienna refers back to the “Plan 60” case study18 presented to the Sub-Network meeting in Liégè in 2007. ‘Empowerment’ courses were targeted at 150 retired professional people who were interested in planning and implementing non-profit projects. Helsingborg’s ‘Passion for Life’ project aims ‘to offer knowledge and tools to senior citizens for them to create a healthy life and empower them to take active responsibility for their own ageing.’ These ‘tools,’ as identified by other city responses, include education, health promotion, social and physical activity. Ljubljana provides the most comprehensive education model of study circles based on ‘the mutual learning of students, mentors and university experts.’ Implemented by the Society for Education in the Third Age, education is regarded as ‘basic for social inclusion and for encouraging an active life.’ Østfold reports how ‘older people become more empowered as they actively participate in voluntary work, community work and physical activity.’ For Udine and Torino, active, healthy lifestyles both contribute to and are a consequence of empowerment.

The majority of city responses to the GEQ refer to collective forms of empowerment by communities representing the interests of older people. These range from the small mutual groups, such as the clubs in Rennes, Liverpool, Novocheboksarsk and Athens, to city-wide organizations such as the veterans associations in Russian cities or the Elders Councils in Gyor and Newcastle. Though it is difficult for certain to ascertain their degree of autonomy in relation to their municipality, ‘unions’ or ‘associations’ appear to be independent organisations, whereas ‘councils,’ though independent in thought, appear to be organised and supported by city authorities. The Pensioners Association of Rijeka and the Ljubljana City Retirement Association are both primarily social support organizations, whereas the Elders’ Councils of Copenhagen, Horsens, Kuopio, Barcelona, Newcastle, Brighton, Turku and Gyor are engaged in the ‘social and political action’ at the collective end of the continuum. There is municipal support for both forms of city-wide organization. For example in Lodz the Polish Union of Senior Citizens, Pensioners and Invalids is ‘supported by the city budget to carry out action for the elderly population in the field of health, education, physical activity and active living.’ In Brighton and Horsens, elections to the Older People’s Councils are organised by the municipality. In Manchester, new members of the Older People’s Board are mentored by council officers to ensure they are confident in taking on the role.

A third of city responses to the GEQ describe how the voice of older people is heard and acted upon by the municipality and its partner agencies. The mechanisms for ‘voice’ are forums, working groups and more permanent advisory committees, all drawing their membership from community organisations or councils representing the interests of older people, and all clustered in the active ‘participation’ quadrant of Davidson’s Wheel.19 Most responses suggest strategic engagement with municipal decision-makers. In Dimitrovgrad, for example, NGO’s such as the Veteran’s Soviet and Womens’ Unity ‘take part in forming municipal policy and making important decisions.’ Belfast has a Strategic Healthy Ageing Group with access ‘to strategic decision-makers’ in the council and specifically in the domains of health and social care, housing and transport. Liverpool’s ‘Empowerment Network’ ‘ensures representation on ‘strategic decision-making groups.’ In their brief responses cities do not elaborate how these voices are acted upon. However, an insight is provided by the case studies presented by Newcastle and Sunderland to the sub-network meetings in Brighton20 and Liégè.21 Newcastle’s Elders’ Council signals priorities to the Older People’s Programme Board which gives strategic direction and is supported by a core team of staff responsible for work programmes. In Sunderland, six 50+ Forums give a ‘voice’ to older people and their priorities frame the agenda of the Older Persons’ Partnership Action Group of managers from key agencies with the resources to deliver.

Supportive Environments

In responding to the GEQ on supportive environments, cities drew on practical and theoretical developments in healthy urban planning (HUP). Guidance by Barton and Tsourou published by WHO22 during Phase III identified 12 objectives for HUP and Sub-network meetings in Phase IV elaborated the healthy ageing dimension of the concept. In the HUP sub-network meeting in Milan in June 2007, Agis Tsouros identified six objectives; to (a) promote age-friendly built environments; (b) create safe and secure pedestrian environments; (c) foster age-friendly community planning and design; (d) improve mobility options for seniors; (e) support recreation facilities, parks and tracks; and (f) encourage housing choices. Introduced by Lena Kanström, from the lead city of Stockholm, at a joint HUP/HA Sub-network meeting of 14 cities in Rijeka in 2007, these provided a framework for case studies from Brighton, Udine and Vienna. The Spectrum tool developed by Barton and Grant was also deployed practically to appraise and grade a major project to renovate a swimming pool complex in Rijeka for use by older people.

Undoubtedly, discussion in the two sub-networks attuned GEQ responses to the principles and practice of healthy urban planning for older people. Three Healthy City projects have themselves been instrumental in elaborating the concept. Sule Onur, coordinator from the Turkish city of Kadikoy gave a theoretical overview on ‘The Value of Urban Design in Relation to Healthy Ageing’ to the Rijeka meeting,23 drawing on the four dimensional model of the ‘Good Life’ developed by American psychologist MP Lawton.24 In its response to the GEQ, Manchester refers to a vision of ‘The Ageless City’ developed with the Manchester University School of Architecture. Udine was one of 33 cities across five continents involved in developing and testing the Vancouver Protocol of ‘Age-Friendly Cities.’ Initiated by WHO Geneva in 2006, this project aimed to ‘stimulate global awareness and multi-sectoral action to improve age-friendliness in urban settings’.25

Such comprehensive overviews of supportive environments are probably necessary for the most advanced, integrated level of HUP identified by Barton and Grant in their article for this special supplement. In their responses to the GEQ, 13 cities take a strategic view of intersectoral partnerships and plans. In an ascending hierarchy, there is evidence first of inter-departmental cooperation in Milan, Udine, Copenhagen and Newcastle, with extensive collaboration in Poznan between the departments of Health and Social Affairs, Urban Planning and Architecture, Environmental Protection and Transportation. The Transport Plans of Belfast, Sheffield and Liverpool reconcile the interests of older people with other essential users. At a more comprehensive level, the interests of older people are incorporated into spatial urban development frameworks in Izhevsk, Ljubljana, Liverpool, Brighton and Sheffield. At the highest level, the General City Plan of Novocheboksarsk supports older people with ‘the creation of a comfortable, secure and attractive environment, which contributes to healthy physical activity, forms a friendly social atmosphere and provides high quality housing conditions.’

Over half of responses to the GEQ fit into Barton and Grant’s intermediate classification of enhancing supportive environments, focusing primarily on housing and mobility. Though responses generally reflect a traditional concern with physically adapting houses to overcome disability and promote independent living, there is also evidence of innovation around a more holistic concept of the home as providing ‘ontological security’ as defined by Giddens.26 A case study from Turku links ‘subjectively felt security’ to the determinants of ‘health, functional ability, social relationships and housing issues’.27 Both the Sub-Network cities of Brighton and Gyor were involved in the Wel_Hops project (2005–2007) which examined European good practice in the design of older peoples’ housing.28 Funded by The European Union under the INTERREG IIIC, this programme concluded that ‘independence and quality of life is more than just bricks and mortar; it requires inclusion in the local community.’ In its response both to the ARTs and GEQ, Milan refers to an innovative approach to social housing which highlights interactions with the social life of the neighbourhood. At a Sub-Network in Francesco Minora (of Milan Polytechnic)29 and Laura Donasetti (Healthy City Coordinator) and the late Emilo Cazzani (Chief City Planner) described how the municipality was responding to this model.

A third of the GEQ references to supportive environments relate to access and mobility. Both Vienna30 and Udine31 refer to their comprehensive approach to neighbourhood development (elaborated at the Rijeka sub-network meeting) which emphasis age-friendly environments to promote ‘socialization’ and intergenerational solidarity. However, most cities tend to emphasise discrete measures to remove ‘architectural’ barriers to walking. Athens refers to the ‘reconstruction of pavements;’ there are new pedestrian pathways within residential areas of Eskisehir, to the parks of Horsens and Leganes, along the waterfront in Montijo and into Vitoria’s old town. Safety is a priority for the ‘slow moving’ people of Novocheboksarsk; Rijeka, Torino, Manchester, Sant Andreu de Barca and Liverpool highlight the need for good traffic management systems to help pedestrians cross roads safely. Implicit in these myriad actions is the promotion of physical activity to enable older people, in Vienna’s words ‘to mentally and physically age in a self-determined and healthy way.’

Access

Within the wider European context, conventional debate on accessibility reflects demographic trends assumed to increase demand for health and social care services. The issue of access arises when the supply of these services does not match demand and must be rationed. In most European states, the dilemma is experienced acutely by city governments which have a competence for social care. Though beneficiaries may provide an element of co-funding, the full cost of care is generally beyond the means of the majority of disabled and dependent older people. Provision must therefore be subsidised by municipalities and when their budgets are constrained, access may limited or denied.

These macro-economic issues tend to be subsumed rather than explicit in city responses to the ARTs and GEQ, probably because municipalities have limited discretion to vary the size of welfare budgets. Sunderland proudly reports that it is one of only three municipalities in England providing a service to older people with low levels of disability. However in general such provision is heavily constrained by the allocation of resources from central government (which provides most municipal income) and by the framework of national laws which requires municipalities to provide resource-intensive services for highly dependent older people of the fourth age. For example Vitoria-Gastiez reports on a new Spanish Law for the Promotion of Personal Independence and Care for People in a Situation of Dependency. The wider macro-economic debate about social welfare provision and access is located in negotiations between city councils (many with strategies to expand provision) and central governments which provide most resources from taxation. Healthy Cities have not enjoined this debate.

Instead the focus of Healthy Cities is explicitly on reducing functional disability, promoting independence and implicitly reducing budgetary pressures. In effect the great surge of healthy ageing actions reported in the ARTS constitutes cities as ‘Laboratories of the Third Age.’ Their innovation is to step beyond, what is now in most European countries, a mainstream agenda of rebalancing resources away from institutional to domiciliary or ‘community’ care. For Healthy Cities, ‘the preservation and stimulation of health’ as described by Ljubljana, is key to the independence which characterises the third age. Local interventions are designed either to maintain health or reduce risk factors leading to illness and disability. For the majority of cities responding to the GEQ, ‘access’ is defined primarily by the availability of these ‘preventive’ services.

Russian cities tend to highlight preventive medical services, for example the Restorative Medicine and Rehabilitation Centre in Stavropol and the Section on Arterial Hypertension in Novocheboksarsk. However these are exceptions. The majority of cities share Poznan’s emphasis on ‘participation in cultural and social life’ to ‘develop intellectual and physical fitness’ and ‘opportunities for older people in Cherepovets to remain socially, intellectually and physically active.’ Strategies and plans (especially in the UK) provide a holistic framework for a range of ‘preventative’ interventions to complement traditional medical and social services.

Cities report two main types of intervention. First are those which enhance social networks and improve mental health. Though many older people receive formal help to accomplish basic activities of daily living in their own homes, nevertheless they may feel isolated and lonely. Cities report a variety of innovative projects to integrate them into their wider community. In a case study presented to the Healthy Ageing Sub-Network, Udine described a programme called ‘Servizi di Prossimità’ ‘to promote equal access to services, not only in terms of concrete needs but also good social relationships aimed at tackling isolation and marginalisation.’ In this case, a network of community volunteers enhanced relationships.32 In the case of Aydin, a number of ‘Sympathy Houses’ encouraged resident’s to have become ‘active members of the complex’ and their mental health has improved. In Izhevsk 30 circles and clubs have improved ‘social communication’ and improved the ‘emotional and psychological status of pensioners.’

Second, a third of city responses to the GEQ refer to the provision of either cultural or physical activities. The implicit assumption (made explicit by Poznan) is they contribute to ‘intellectual or physical fitness.’ Often, these two aspects are combined in a holistic approach. Kupio’s model programme has ‘helped bring culture to elderly homes’ and also includes ‘a network of gyms for elderly people.’ Athens has special programmes of theatre and archaeological visits and also ‘athletics centres and gyms.’ Izhevsk has educational and literary clubs and also dancing. Manchester highlights a mobile library service and also ‘tai chi, dance, curling and aqua-aerobics.’ Sunderland’s ‘sport and leisure facilities, libraries, arts centres and community venues offer a wide range of activities for the physical and emotional well-being of older residents.’

Cities also define access as removing physical and financial barriers. Manchester refers to ‘Design for Access’ as part of its healthy urban planning process. Participation in activities outside the home, and especially beyond the immediate neighbourhood, depends on user-friendly transport. Low platform buses, referred to in Sunderland’s profile and Lodz’s GEQ, are exemplars of universal design to accommodate people with physical disabilities. Cities may also modify the rigidities of conventional public transport systems by providing supplementary door-to-door schemes for older people. Udine, Stockholm33 and Sunderland presented case studies to the Sub-Network in Parnu of such ‘Soft-line’ services run by NGOs; and responding to the GEQ, Sant Andreu de la Barca refers a ‘door-to-door service which takes the elderly with reduced mobility anywhere they need to go.’ A quarter of responses to the GEQ also refer to free or subsidised services, primarily for public transport, but also extending to recreational and leisure venues.

Finally, as Montijo reports, it is necessary to ‘raise older peoples’ awareness of what is available and how they can access it.’ A quarter of city responses to the GEQ highlight a proliferation of methods of communication: ‘e-news’ in Galway, Dresden and Stockholm; ‘tele-assistance’ in Barcelona and Kupio; directories in Belfast, Manchester and Sant Andreu de la Barca; home visits by professionals in Dresden, Turku and Sheffield to access ‘hardest to reach groups in the poorest neighbourhoods.’ A few cities refer to the need for coordination, a traditional concern of those attempting to navigate the labyrinth of social services. The French cities of Rennes and Dunkerque refer respectively to a ‘Local Information and Co-ordination Centre’ and a ‘Local Social Action Centre’ which perform this function. Brighton initiated a ‘Central Access Point of Information’ and Sheffield refers to ‘A single point of access to a wide range of advice and information.’

Discussion

The study was designed to describe and assess the orientation of Healthy Cities towards a healthy ageing approach to policy and programme development. Though the GEQ questions may have encouraged cities to over-report such an approach, there is nevertheless evidence of deep and widespread commitment. In raising awareness of older people, cities eschewed the orthodoxy of a demographic time bomb, where ever larger numbers of dependent older people are a drain on the economy and an increasing burden on health and social support services. These are socio-economic challenges of the fourth age and there is no unequivocal evidence on whether greater longevity has increased the quantum of functional incapacity and the number of dependents.34 Instead, though not explicitly using the term, cities preferred to focus in effect, on the third age of independence and achievement, many highlighting older peoples’ contribution to society and the economy.

Consequently the issue of access was not generally regarded as overcoming barriers to receiving health and community care services, though undeniably age discrimination coupled with financial constraints may limit the provision of these services. Instead the focus of responses was explicitly on increasing access to upstream (or distal) physical and social activities to maintain physical and mental health. Implicit is the model in Active Ageing of functional capacity declining over the life-course. Cities were equating ‘Healthy Ageing’ with ‘Active Ageing’ first to defer the onset of illness and disability associated with the fourth age, and equally important, enhance the living environment better to celebrate the third age.

Cities reported myriad initiatives to encourage active lives, though the focus was on context rather than personal agency, reflecting the WHO slogan ‘making healthy choices the easier choices.’ The supportive environments reported by cities added an age-friendly dimension to the principles of ‘healthy urban planning,’ another core theme of Phase IV of the Network. Besides the more obvious removal of physical barriers to activities of daily living in the home and to mobility in the neighborhood and beyond, cities emphasised supportive social environments. Many responses demonstrated a sophisticated understanding of the interplay between the physical and social characteristics of a neighborhood or city. However, a challenge for Network cities is to measure and monitor interventions, their immediate outcomes and wider impacts. It is easier to assess the benefits of independent living in homes adapted to overcome functional disabilities, more difficult to measure the impact of systemic modifications to the wider city environment, the highest level of integrated planning recommended by Barton and Grant in their article for this special supplement.

Though issues of personal empowerment tend to dominate the international literature on health promotion and health care provision, most city responses were towards the collective and community interpretations of empowerment at the other end of the continuum presented by Laverack. This emphasis probably derives from the position of respondents near or at the centre of municipal administrations, keen to describe how the voice of older peoples’ ‘community of interest’ may be heard in forums and committees reaching out beyond health and social service reform; emphasising intersectoral strategies and policies to give effect to their priorities.

This review was not designed to assess whether policies were effectively delivered, but at least there is some indication that at a corporate city level, the voice of older people is heard and acted upon by municipalities and their partners. The wider impact of the collective effort by the Healthy Ageing Sub-Network is more difficult to assess. However, it clearly contributed to and benefited from two products which evolved over the series of meetings and messages, and were converted into WHO guidance at the end of Phase IV. Demystifying the Myths of Ageing35 promoted an age-friendly orientation for city policy makers, political decision-takers and their partners: Healthy Ageing Profiles36 provided the baseline of a common local planning platform. There is some evidence that both are effectively challenging the orthodox interpretations of ageing across European states and within European cities.

Conclusion

There are two key messages from this review. First, membership of the WHO Healthy Ageing Network has encouraged cities to adopt a healthy ageing approach to older people rather than a traditional focus on illness and dependency. Second, by applying healthy ageing strategies to programmes and plans in many sectors, city governments can potentially compress the fourth age of decrepitude and dependence and expand the third age of achievement and independence,’ with more older people contributing to the social and economic life of the city.

Both messages have greater resonance with city and national governments in a period of austerity, first because the cost of health and social services for older people is a very large component of municipal and national budgets all across Europe and beyond. Second, it is necessary to extend healthy working lives in order to reduce high dependency ratios engendered by the increase in retired populations. A life-course approach to active ageing should in time reduce budgetary pressures, and early interventions to provide a supportive social and physical environment are largely the responsibility of local governments and their partners. Both of these propositions are now significant components of the WHO European Strategy and Action Plan for Healthy Ageing.37 Phase IV of the WHO European Healthy Cities Network is contributing city experience and expertise to convert this European strategy into local reality.

Acknowledgments

The evaluation was commissioned by the WHO Regional Office for Europe. Thanks to Lena Kanstrom, Gianna Zamaro, Angela Flood and Claes Sjostedt who were the planning group for the WHO-EHCN Healthy Ageing Sub-Network, and the contribution of 19 city representatives.

References

- 1.European Commission. Confronting Demographic Change: a new solidarity between the generations. The Green Paper on Demographic Changes. Brussels, EC; 2005.

- 2.Active ageing: a policy framework. Geneva: WHO; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laslett P. A fresh map of life: the emergence of the third age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kalache A, Barreto SM, Keller I. Global ageing: the demographic revolution in all cultures and societies. In: Johnson ML, editor. The Cambridge handbook of age and ageing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith J. The Fourth Age: a period of psychological mortality. Berlin: Max Planck Institute for Human Development; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Whitehead M. A typology of actions to tackle social inequalities in health. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2007;61:473–478. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.037242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grady M, Goldblatt P, editors. Addressing the social determinants of health: the urban dimension and the role of local government. Copenhagen: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Green G. Health and governance in European cities. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pawson R, Greenhaigh T, Harvey G, Walshe K. Realist review—a new method of systematic review designed for complex policy interventions. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2005;10(Suppl 1):21–34. doi: 10.1258/1355819054308530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ritsatakis A. A positive and dynamic model for profiling older people in cities. Unpublished paper presented to the first Healthy Ageing Sub-Network Meeting. Stockholm. 2005.

- 11.Kanström L, Zamaro G, Sjostedt C, Green G. Updated guidance for completing the healthy aging profile. Unpublished WHO Working Paper; 2006.

- 12.Iwanicka I. Lifestyles of senior citizens in Lodz. Case study presented to the WHO International Conference. Zagreb; 2008.

- 13.Zamaro G. Impact of healthy ageing profiles on city policies and practice. Rijeka: Presentation to the Healthy Ageing Sub-Network Meeting; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Davidson S. Spinning the wheel of participation. Planning. 1998;1262:14–15. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laverack G. Empowering older people. Background Working Paper. Healthy ageing phase IV sub-network. Copenhagen: WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laverack G. Addressing the contradiction between discourse and practice in health promotion. Unpublished PhD thesis. Melbourne: Deakin University; 1999.

- 17.Labonte R, Laverak G. Capacity building in health promotion. Part 1. For whom? And for what purpose? Critical Public Health. 11(2): 111–127.

- 18.Hübel U. Plan 60 guidance for active retirement. Case Study presented to Sub-Network Meeting. Liégè; 2007.

- 19.Davidson S. Op.cit., 1998.

- 20.Douglas B. Empowerment and participation of older people; quality of life partnership. Case Study presented to Sub-Network Meeting. Brighton; 2006.

- 21.Patchett A. Empowering older people in Sunderland. Case Study presented to Sub-Network Meeting. Liégè; 2007.

- 22.Barton H, Tsourou C. Healthy urban planning—a WHO guide to planning for people. London: E&FN Spon; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Onur S. The value of urban design in relation to healthy ageing. Unpublished paper presented to the Sub-Network meeting. Rijeka; 2008.

- 24.Lawton MP. Environment and other determinants of well-being in older people. Gerontologist. 1983;23:349–357. doi: 10.1093/geront/23.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Global age-friendly cities: a guide. Geneva: WHO; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Giddens A. Modernity and self identity: self and society in the late modern age. Cambridge: Polity; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arve S, Minna Railo M. Experiences of insecurity of the oldest old people living at home. Case study presented to the WHO international conference. Zagreb; 2008.

- 28.Emilia-Romagna Territorial Economic Development S.p.A. (ERVET) et al. Older persons’ housing design: a European Good Practice Guide. Bologna, Wel-hops Network, 2007. http://www.brighton-hove.gov.uk/indexcfm?request=c113815 (accessed 6th October 2008) Case Study presented to Sub-Network Meeting. Rijeka; 2007.

- 29.Minora F. Ageing and Housing: four different ways to look at Accessibility. Case Study presented to Sub-Network Meeting. Brighton; 2006.

- 30.Huebel U, Häberlin U. sALTo- self-determined ageing in urban neighbourhoods. Case Study presented to Sub-Network Meeting. Rijeka; 2007.

- 31.Zamaro G, Grizzaffi B. Planning together sustainable integrated urban networks. Case Study presented to Sub-Network Meeting. Rijeka; 2007.

- 32.Zamaro G. ‘Servizi di Prossimità’ (Services closer to people’s needs) Case study presented to Sub-Network meeting. Brno; 2008.

- 33.Kanström L. Accessibility in Stockholm county. Case Study presented to the Sub-Network meeting. Pärnu; 2007.

- 34.Hank K. How successful do older people age? Findings from SHARE. J Gerontol B. Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66B(2):230–236. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ritsatakis A. Demystifying the myths of ageing. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kanström L, Zamaro G, Sjostedt C, Green G. Healthy ageing profiles: guidance for producing local health profiles for older people. Copenhagen: World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. Strategy and Action Plan for Healthy Ageing in Europe (2012–2016). EUR/RC62/10. Copenhagen. WHO. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/169738/RC62wd10-Eng.pdf. (accessed 4th September 2012)