Abstract

The purpose of this paper is to evaluate the progress made by European cities in relation to Healthy Urban Planning (HUP) during Phase IV of the World Health Organization's Healthy Cities programme (2003–2008). The introduction sets out the general principle of HUP, identifying three levels or phases of health and planning integration. This leads on to a more specific analysis of the processes and substance of HUP, which provide criteria for assessment of progress. The assessment itself relies on two sources of data provided by the municipalities: the Annual Review Templates (ARTs) 2008 and the response to the Phase IV General Evaluation Questionnaire. The findings indicate that the evidence from different sources and questions in different sections are encouragingly consistent. The number of cities achieving a good level of understanding and activity in HUP has risen very substantially over the period. In particular, those achieving effective strategic integration of health and planning have increased. A key challenge for the future will be to develop planning frameworks which advance public health concerns in a spatial policy context driven often by market forces. A health in all policies approach could be valuable.

Keywords: Healthy Cities

Introduction

What is the purpose of town planning? Is it to create a beautiful environment, or a well-functioning settlement, or a fairer society? Is it to facilitate economic development? Or it is to ensure long-term sustainability, attempting to reduce our ecological footprint? To some extent, it is, of course, all of these things … but what is the essence of it? The answer given by the Healthy Cities Project (coordinated by the WHO Regional Office for Europe) about human health, and planning human settlements which offer the best opportunity for people now and in the future to enjoy good quality of life.

This follows logically from the WHO definition of health enshrined in its constitution in 1948, in the period of determined idealism that followed the Second World War

“Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. The enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of health is one of the fundamental rights of every human being, without distinction of race, religion, political belief, economic or social condition.”1

This challenges the conventional assumption that health policy is only a matter for health care professionals. On the contrary, a concern for health and well-being becomes central to many aspects of national and local policies. We see in relation to the epidemic of obesity hitting many industrialized countries that solutions are being sought in food policy, retailing, recreation and transport but not primarily in health care. In a similar manner, the link between health and planning across a range of non-communicable diseases is multi-dimensional. It encompasses social, economic and environmental purposes of town planning. Whilst this is intuitively obvious, it is institutionally problematic. This paper outlines the context for the range of issues that should be addressed in planning and their organisational implications, leading to criteria for evaluation of progress in Healthy Urban Planning (HUP). The findings of the evaluation of Phase IV Healthy Cities are presented and discussed. On the basis of these, some conclusions for those involved in health and planning are derived.

Urban Planning as a Determinant of Health

The effect of place on health is an important strand of both conceptualization and policy development.2 The environment has long been recognised as a key determinant of health.3–4

Promoting health solely programs of changing the behavior of individuals or small groups is not very effective, reaching only a small proportion of the population and is seldom maintained in the long-term.5, 6 What is needed is a more fundamental reassessment of the way in which social, economic and environmental impacts shape and are shaped by spatial planning and its result: physical development. This calls for a reassessment of the role of the planning and design of human habitation in promoting health.

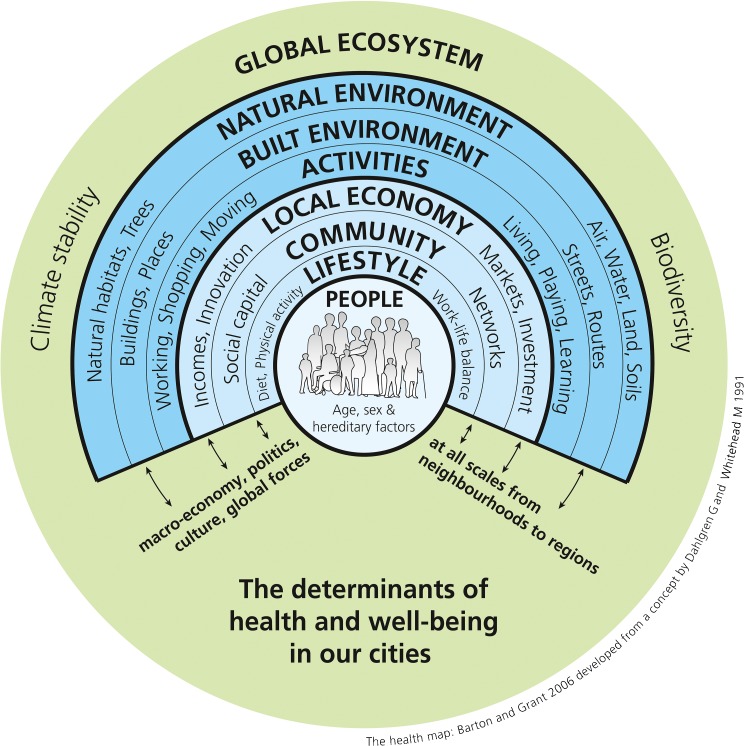

Evidence shows that spatial planning, or ‘urban planning, in our towns and cities has a profound effect on the risks and challenges to population health.7 The broad nature of multiple impacts of human settlement form on health has been described in a settlement health map8 (Figure 1). This was developed for the WHO-sponsored practice guide Shaping Neighbourhoods, now in its second edition.9 Inspired in part by Whitehead and Dahlgren's11 figure of the determinants of health, the diagram shows the various spheres of social and economic life and the wider environment that impact the health of individuals. All these spheres are themselves affected by the changes in the built environment, in complex and interacting ways.

Figure 1.

The determinants of health and well-being in our cities. A settlement health map showing the broad nature of multiple impacts of human settlement form on health.

Many of the urban development trends promoted by the market and facilitated by planning authorities have promoted unhealthy car-dependent lifestyles as an easy choice.12 In so doing, they may constrain choice for healthy lives, exacerbate inequalities and also have implications for sustainable development. For example, across Europe, expanding peripheral city areas exhibit a pattern of low density, use-segregated car-based development dependent on high levels of fossil fuel use. This urban form not only uses land profligately but reduces the viability of local services, makes walking impractical because of long distances and deters cycling through catering substantial for ease of motorised transport. The fashionable office, retail and leisure parks that spring up in the wake of road investment typically rely on 90–95% car use. The segregation of land uses undermines the potential for integrated neighbourhoods, thriving local facilities and local social capital. Both unsustainability and pathogenicity are literally being built into our cities.

In this context, health is a casualty. The decline in regular daily walking and cycling is resulting in increased obesity and risk of diabetes and cardiovascular diseases.13 Health inequalities are exacerbated. People tied to locality—elderly people, children, young parents, unemployed people and immobile people—are especially vulnerable. The decline in local facilities, the reduction in pedestrian movement and neighbourly street life all reduce opportunities for the supportive social contacts so vital for mental well-being.14

The WHO Healthy Urban Planning Initiative

Phase IV of the WHO European Healthy Cities programme included healthy urban planning (HUP) as one of the main themes which all member cities should develop. This review should be seen in relation to its emergence in previous phases. The baseline for work of linking health and urban planning was established in 1998 through a questionnaire survey. Respondents were the heads of urban planning departments in 38 cities participating in the second phase (1993–1997) of the WHO European Network. Regular cooperation between health and planning occurred in only 25% of cases. Nearly one-third of planning heads considered that planning policies were incompatible with health. Several anti-health issues in the planned urban environment were highlighted: excessive levels of motorised traffic, focus on private profit, social segregation and lack of attention to the everyday needs of citizens.15

A comprehensive definition of HUP was developed to address all the health determinants relating to the physical environment of the cities and to reflect the core principles of the WHO strategy for health for all16 such as equity, community participation and intersectoral cooperation. A set of 12 objectives were adopted for the HUP theme, consistent with those of sustainable development and Agenda 21.17 The 12 HUP objectives, which relate to the sequence of spheres of the health map, were:

Promoting healthy lifestyles (especially regular exercise);

Facilitating social cohesion and supportive social networks;

Promoting access to good quality housing;

Promoting access to employment opportunities;

Promoting accessibility to good quality facilities (educational, cultural, leisure, retail and health care);

Encouraging local food production and outlets for healthy food;

Promoting safety and a sense of security;

Promoting equity and the development of social capital;

Promoting an attractive environment with acceptable noise levels and good air quality;

Ensuring good water quality and healthy sanitation;

Promoting the conservation and quality of land and mineral resources; and

Reducing emissions that threaten climate stability.

Subsequently, in phase III, HUP was adopted on an experimental basis. Volunteer cities under the leadership of Milan formed a city action group and progressively developed the principles and practice of health-integrated planning with the aid of the WHO Collaborating Centre for Healthy Cities and Urban Policy, based in Bristol's University of the West of England.18

Levels of Health Integration in Planning

The experience of the cities in Phase III led us to identify three distinct levels of integration of health and planning. These levels provide a simple classification of HUP development and are used in the later analysis.

The first level is basic. It is recognition of the essential life support role of settlements: provision of shelter, access to food and clean water, fresh air and effective sewage treatment. It was the realisation that the industrial cities of the 19th century were inimical to health that led directly to modern planning. In Western Europe, we mostly take this primary level of planning/health dependency so much for granted that it is almost subliminal. Elsewhere that is not always the case. Sprawling, high density shanty towns lack essential services. Communicable diseases are rife. Effective health planning through well-designed settlements is difficult to achieve, swamped by the sheer pace of urbanisation.

The second level goes beyond environmental health. There is the recognition that many facets of settlement planning and design affect health and well-being: parks in otherwise dense cities give opportunities for physical activity, contact with nature, fresher air and aesthetic delight; allotments support access to fresh food, physical activity and social cohesion; cycle networks, encourage healthy activity, a safer environment, reduced car reliance, equity in access and combat the rise in greenhouse emissions; and housing renewal and economic development projects may reduce health inequalities. With such projects, the addition of health is an extra dimension and draws in an extra constituency of political support. However, the effectiveness of this approach is fragmented and limited by the broader drivers and structures of economic and spatial development, which often precipitate change in the opposite direction.14 The focus of this level is to tackle the ‘downstream’ outcomes of poorly integrated planning but not to tackle the ‘upstream’ drivers.

The third level is where health is fully integrated into the planning process. Planning for health and well-being becomes a fundamental purpose of plans at local, city and regional levels. It meshes with other core themes of environmental sustainability, social justice and economic development. This level is much rarer. It relies on effective collaborative programmes, reinforcing each other, bridging between departments and agencies that conventionally adopt a silo mentality. It is not simply a matter of public health units working closely with planners but of housing officials, greenspace managers, regeneration and transport planners all working together. In particular, if the long-term health of the population is accepted as fundamental to urban planning, then ways of pursuing economic objectives without creating unhealthy settlement form have to be found.14

Methodology

This article reviews cities in relation to HUP activity as part of a wider evaluation of Phase IV of the WHO European Healthy Cities network. The review is based on the response to the Phase IV General Evaluation Questionnaire (GEQ) and the Annual Reporting Templates (ARTs) for 2008.

There are several limitations to a methodology assessing multi-sectoral activity in countries across Europe though a questionnaire. To increase the validity for this evaluation, results have been triangulated by comparing three overlapping sources of information.

The first source is the answers to the direct questions on HUP in the questionnaire. Of the 77 cities in Phase IV, 51 cities responded to the HUP parts of the questionnaire. The questions sought to find out (a) how far the Healthy Cities project in the municipality was effective in relation to specific strategic HUP priorities and (b) what the Healthy Cities team considered the most important HUP issues. The second source is the responses to broader questions of health equity where HUP is not the prime focus but we might expect it to feature if the city has a well-developed awareness of how planning influences health.

The third source is the responses to related questions in the ART returns. These were collected each year during Phase IV and provide an overview of progress in terms of the quantity and quality of HUP activity as self-assessed by the cities. The criteria used to assess progress were:

The number and scale of HUP projects or programs;

The degree to which all 12 HUP objectives are addressed;

The degree to which the HC team is working with varied planning agencies; and

The level of HUP training.

There will be inevitable discrepancies and limitations to reliability. Each set of responses might well be from different people, reflecting different sectoral knowledge and professional biases. The second set, in particular, might be from someone with little direct knowledge of HUP, focussing on things they understand best. Due to language and cultural differences, it is not always possible to know for sure what respondents mean and assumptions need to be made in interpreting responses. There is also the problem that some responses may reflect wishful thinking not actual achievement. The triangulated approach has, though, allowed us to reduce error, synthesising data from more than one source when summarising a city's achievements.

The overall assessment thus involves analysis of the responses in relation to the following key themes—set out in the findings below:

Significance of Healthy Cities for two key planning goals,

Explicit recognition of HUP issues by the Healthy Cities team,

Implicit awareness of the significance of HUP for health, and

Progress with HUP throughout Phase IV.

These allow judgements of the number of cities which are at each of the three levels of HUP engagement referred to in “Introduction” and some assessment of general progress through Phase IV.

Findings

Significance of Healthy Cities for Key Planning Policy Areas

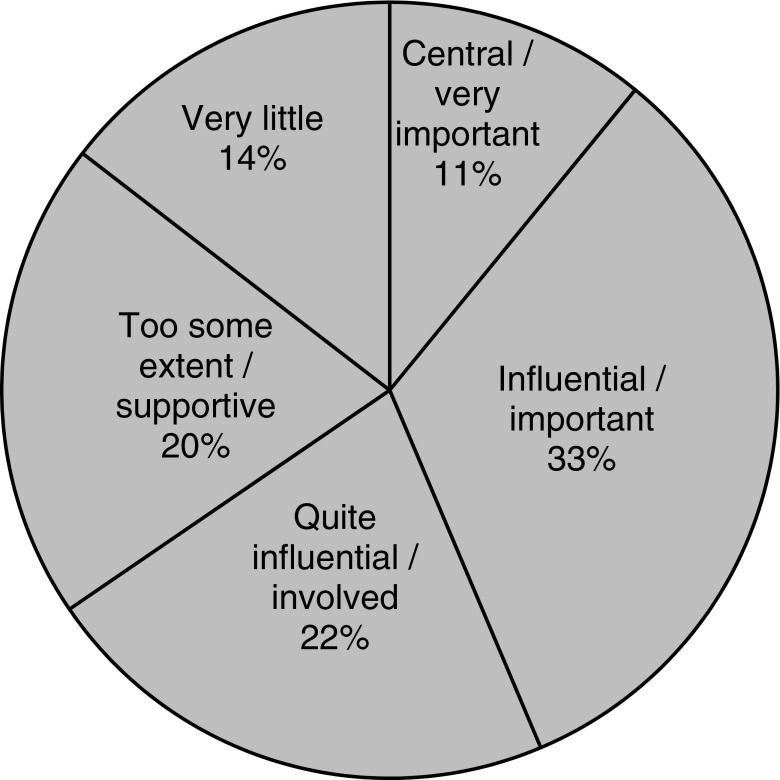

The General Evaluation Questionnaire asked cities to assess how influential the healthy cities initiative (‘Healthy Cities’) has been in advancing the strategic priorities of healthy aging and access for all in the urban environment. These are key planning issues, reinforced by Phase IV as priority areas for action. We would expect a positive answer if the HUP agenda is actively pursued in the city. For the analysis, we allocated responses into five classes:

Healthy Cities central to the program/critical/very important,

Healthy Cities a partner in the process/influential/important,

Healthy Cities involved but not keyquite influential,

Healthy Cities supportive of the program but only peripherally involved, and

Healthy Cities does not yet have significant impact/no relevant program.

Figure 2 indicates that almost two-thirds (65%) of the respondents consider they are actively involved with planners and are quite/centrally/very influential in shaping such programmes. Others (20%) are aware of policies in these fields and support them, but have little direct involvement. A small minority, 15%, believe that their authority has not yet acted on such concerns.

Figure 2.

Respondents' response to the question: “To what extent has Healthy Cities been influential in advancing strategic HUP priorities to support healthy aging and promote access and mobility for all in the urban environment of your city? (Q6.12)”. Results indicate that almost two thirds (65%) of the respondents consider they are actively involved with planners and are quite/centrally/very influential in shaping such programmes.

Explicit Recognition of HUP Issues by the Healthy Cities Team

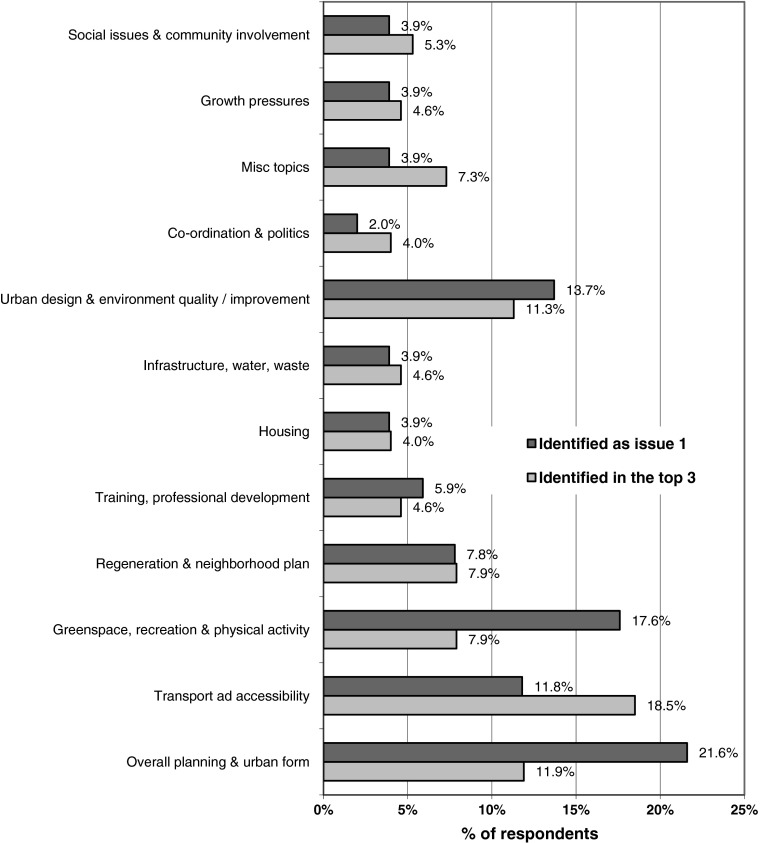

A second question was asked for the three most important HUP issues in your city. In analysing the different answers, they were clustered into 12 topics. Figure 3 indicates in what proportion of the answers a topic was a top priority and also how often it was included in the top three priorities.

Figure 3.

Respondents' response to the question: “What were the three most important HUP issues in your city? (Q6.9)”. Results indicate in what proportion of the answers a topic was a top priority and also how often it was included in the top three priorities.

There were 51 valid responses to this question. The overall planning and urban form topic was highlighted more (22%) than any other topic, though only as a top three priority in 12% of responses. The greenspace/recreation/physical activity topic accounted for almost 18% of priorities, but only 7% included it within the top three. Transport and accessibility accounts for 12% priority and was the most often included in the top three (19%). Urban design and environmental quality/improvement are also given good recognition by cities with over 13% reporting it as a top issue and over 11% of cities putting the issue within the top three.

Issues not ranked so highly included community/social issues, housing, coordination/politics, infrastructure, growth pressure and training. A few cities, between 2% and 5%, considered one of these was important.

Implicit Awareness of the Significance of HUP for Health

Another way of assessing the degree to which Healthy City teams are fully aware of the significance of planning for health is to see how far they identify planning policies when discussing a key health issue. Two questions provided an opportunity for this.

Cities were asked whether there were specific policies and programs that address equity and health inequalities (Q4.4). Despite often giving quite full answers, very few of the Healthy City teams identified any planning-related policies in their response. Yet policies for urban form, transport, housing, regeneration, etc. can have a significant impact on equity.

However, when asked, in the next question (Q4.5), if there are other important policies and programs that have an (implicit) impact on equity and inequality, the response of 56 respondents was rather different: 25% were quite clear about the relationship, normally identifying a number of issues, 43% did not mention any spatial or built environment policy area as having an influence on equity and 35% identified one spatial/environmental policy area or made a statement which could well have been intended to include such policies but was not very clear.

Progress with HUP Throughout Phase IV

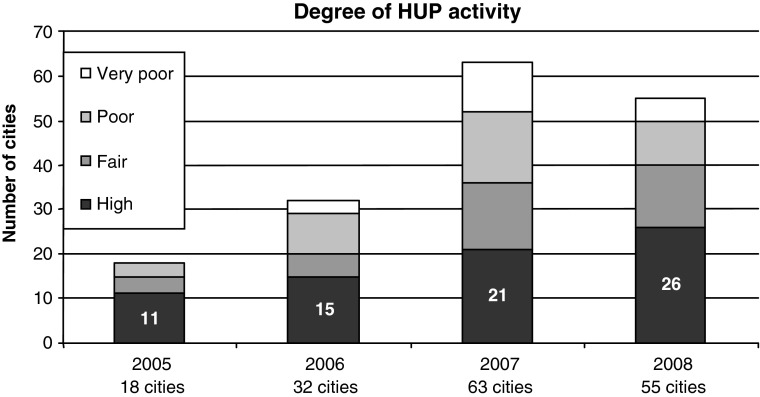

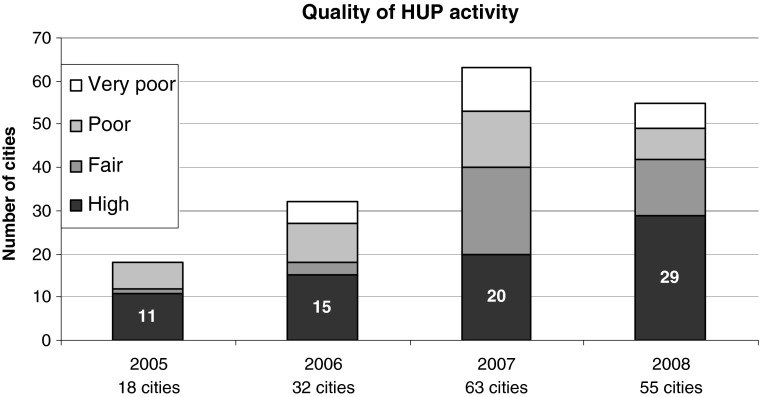

Progress of HUP through the duration of Phase IV can be tracked through review of data provided each year in the annual city returns as provided by the Annual Reporting Templates (ARTS). All cities have to provide a detailed return about their activity across the whole program including the HUP core theme. These replies were looked at in detail and assessments made of the level of activity (i.e., quantity) and the nature of that activity (i.e., quality).

Each year, the degree of cities' HUP activity was assessed on a range from very poor to high. ‘Very poor’ may mean no reported activity or a single meeting or plan for a small project. A ‘poor’ degree of activity indicates implementation of one small project. The cities scoring ‘fair’ are involved both in meetings/training and a significant level of project implementation. Cities achieving a high degree of activity all have vibrant HUP programmes: typically an active programme of training and stakeholder meetings and a major project program, sometimes including fully health-integrated plan-making.

Figure 4 shows how the degree of HUP activity has grown through each year of Phase IV. The number of cities assessed as having high degree of HUP activity has grown year on year, from 11 in 2005 to 26 in 2008. Many cities, new to the network, joined in 2006 and 2007. This led to a sharp increase in cities scoring poor and very poor, especially in 2007. In the final year of the phase, 2008, there is a reduction in the number of cities in both these categories. This is mainly due to these new entrants familiarising themselves with HUP and beginning to make better progress.

Figure 4.

The number of cities assessed as having high degree of HUP activity has grown year on year, from 11 in 2005 to 26 in 2008.

The quality and range of HUP activity from each city was also assessed from information in the annual city reports. Quality was assessed by the degree to which city HUP activity:

Addressed the twelve HUP objectives,

Demonstrated integration with Healthy Impact Assessment and Healthy Ageing (two other phase IV themes),

Displayed a range of activity at different spatial scales,

Evidenced both an integrated strategic approach and implementation at the local level, and

Involved a good range of relevant planning agencies and community stakeholders.

These five indicators of quality set a tough challenge for any city but are also mutually supportive in that each additional one that is addressed will lower the effort in addressing the remaining ones. Cities did not have to meet all the five indicators at a consistently high level to be scored as having a high quality of activity—a subset of cities did, however, manage this as will be reported below.

Figure 5 shows that the quality and range of HUP activity at the high end increased year on year, from 11 cities in 2005 to 29 in 2008. When those 29 are looked at in detail, two-thirds of them (19) were graded as having very good quality, up from 11 the year before. These are the cities where HUP activity is at level 3, in the previously described three level model.

Figure 5.

The quality and range of HUP activity at the high end increased year on year, from 11 cities in 2005 to 29 in 2008.

As with the degree of activity, described above, we see a pattern in 2006 and 2007 of many new cities joining the network and having a fair, poor or very poor quality of activity. All of these categories are reduced in the final year, with a marked increase in high quality.

Discussion

Taken as a whole, results from the General Evaluation Questionnaire give some contradictory messages. Direct questions about HUP often elicit very positive responses. Indirect questions indicate that whilst some respondents have a formidable grasp of the health and planning interplay, many others do not. Checking the results against a second good source of data, the ARTS, had the advantage of providing a different perspective and providing a time series over Phase IV.

There is an encouraging picture of the degree to which each Healthy City team is actively involved in planning policy making. Certainly, a level of engagement between planning and health agencies is indicated that did not exist when the first survey was undertaken in 1998.

In terms of the range of HUP, there are examples both of cities concentrating on specific projects and of others with more broad ranging programs. One of the real problems in developing the HUP program has been an approach seen in many cities which emphasises action as a series of specific projects such as park improvements, allotment provision, safe road crossings, cycle lanes (i.e., level 2 as defined at the start of this paper). However, all research suggests that without a strategic (level 3) approach to HUP, the value of individual projects will be limited.7

There is evidence of a high degree of explicit recognition of HUP issues by the Healthy Cities' teams. It is interesting to note that the environmental health concerns related to water, air and waste—i.e., level 1 of the three HUP levels—are highlighted by only a small number of municipalities. This indicates the degree to which basic life support is not critical—except in a few, mainly eastern, countries. Transport, urban form, urban design and environmental quality issues are given the greatest weight by many. The interest in environmental quality runs in parallel with the emphasis on specific improvement projects (level 2). The degree of significance given to overall planning and urban form was unexpected. Contrary to experience in earlier years, this suggests that now, a significant proportion of cities are aware of, and concerned about, strategic planning. However, in many instances, strategic awareness is not yet reflected in strategic (level 3) action. The importance given by some cities to the need for training, professional development, inter-departmental cooperation and political awareness reinforces the message that organisational development is necessary to tackle HUP effectively.

There was a disappointing response in terms of awareness of the significance of spatial planning for health equity. This demonstrates the degree to which many Healthy Cities teams have still failed to fully grasp the nature of the built environment/health relationship. However, there are clear signs of deepening understanding. The quarter of cities that fully recognised the planning/equality relationship were often very strong in their statements—not equivocal at all. The policy areas identified differed somewhat from those given in answer to other questions: employment/economic policies (affecting income and status) and housing policies (affecting affordability, overcrowding, poor living conditions and fuel poverty) are prominent; and transport/accessibility, environmental quality, strategic planning and regeneration policies all also feature significantly.

Two-thirds of cities consider that the Healthy Cities program has been influential in shaping planning policy in the interests of a healthy urban environment. Overall, a quarter of cities are already working effectively at level 3. Most of the rest are at level 2. Cities are mainly very comfortable with activity at this level. The challenge is to use the HUP approach to work across disciplinary and professional boundaries as a core spatial planning value to achieve level 3.

It is also clear that some cities are still at level 1—i.e., concerned with basic environmental health. This reflects the number of new entrants to the network, in particular, the Eastern European cities. At the end of Phase IV, those that had engaged with the programme were already attempting the second level—working on discreet projects that enhance quality of life.

Analysis of the ARTs demonstrates progress in the adoption of HUP, especially towards the end of Phase IV. The analysis actually underplays the degree of change. This is because at the beginning of the Phase, some Cities' views of what HUP meant was less developed, so their self-assessment was perhaps less realistic—i.e., giving an inflated view of their achievements. Advocacy of HUP by the WHO Regional Office—which in this phase saw a sub-network leading HUP development with peer/peer sharing and training from expert advisors—has, from our own observation and feedback from cities, made an impact, and the accuracy of self-assessment is now much better.

Conclusions

This evaluation indicates that the level of understanding of the significance of planning for health by the Healthy Cities movement has developed significantly over the period of phase IV, but still has some way to go. A broad conclusion is that the Healthy Cities program can be effective in promoting the critical importance of linking health and planning and in disseminating and developing good practice. In many cities, it has helped to transform the political and professional agenda, integrating health with sustainable development and the planning of the human environment. However, many cities are still struggling with the more strategic and holistic approach of level 3. Two common factors seem to be that they are hampered by internal institutional barriers and by an evolving spatial form which is driven by ‘what the market can deliver’. Such barriers militate against any form of integrated working; it is not just HUP that will be disadvantaged. Any city, as a large complex organisation, will suffer from this to an extent, and we can see that the successful cities are those that engage a broad range of stakeholders and form wide ranging partnerships providing a continual bulwark against sectoral silos.

Level 3 brings with it a heavy responsibility: many current policy assumptions widespread across Europe like business parks and retail parks need careful and honest review. The integration of health and planning, therefore, requires, in most cities, a fundamental change in organisational structures and remits. This type of change can be supported by a programme which promotes knowledge exchange and a reflective discourse on values between public health professionals and planners19. In democratic societies, it depends on strong consensus in the population. It also requires effective leadership from the top, willing to rethink established policy. Commitment to a Health in all Policies approach would concentrate minds.

References

- 1.Constitution of the World Health Organization, 14 U.N.T.S No. 185 (1948), Art. 1. Available at http://www.who.int/governance/eb/who_constitution_en.pdf.

- 2.Macintyre S, Ellaway A, Cummins S. Place effects on health: how to conceptualise, operationalise and measure them? Soc Sci Med. 2002;55:125–139. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lalonde M. A New Perspective on the Health of Canadians. Ottawa: Healthy and Welfare Canada; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marmot M, Wilkinson R, editors. Social Determinants of Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawlor D, et al. The challenges of evaluating environmental interventions to increase population levels of physical activity: the case of the UK National Cycle Network. J Epidemiol Commun Health. 2003;57:96–101. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.2.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McCarthy M. Transport and health. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson R, editors. Social Determinants of Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braubach M, Grant M. Evidence review on the spatial determinants of health in urban settings IN Urban Planning, Environment and Health, from Evidence to Policy Action, Annexe 2 p 22–97. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barton H, Grant M. A health map for the local human habitat. J R Soc Promot Heal. 2006;126(6):252–253. doi: 10.1177/1466424006070466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barton H, Grant M, Guise R. Shaping Neighbourhoods for Local Health and Global Sustainability. London: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dahlgren G, Whitehead M. version published. In: Whitehead M. Tackling inequalities: A review of policy initiatives, in Benzeval M, Judge K, and Whitehead M eds. Tackling inequalities in health: An agenda for action. London: Kings Fund; 1991; 1995.

- 11.Whitehead M, Dahlgren G. What can we do about inequalities in health? Lancet. 1991;338:1059–1063. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91911-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rao, Prasad, Adshead and Tissera (2007) The built environment and health, The Lancet, Published Online, September 13, doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61260-4 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Franklin T, et al. Walkable streets. New Urban Futures. 2003;10:5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barton H. Land use planning and health and well-being. Land Use Policy. 2009;26(Supplement 1):S115–S123. doi: 10.1016/j.landusepol.2009.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barton H, Tsourou C. Healthy Urban Planning—a WHO Guide to Planning for People. London: E&FN Spon; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.health21—the Health for All Policy Framework for the WHO European Region. (1999) Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe, (http://www.who.dk/InformationSources/Publications/Catalogue/20020322_1, accessed on 17 September 2003).

- 17.Agenda 21: Earth Summit—The United Nations Programme of Action from Rio. New York: United Nations Publications; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Barton H, Mitcham C, Tsourou C, editors. Healthy urban planning in practice: experience of European cities. Report of the WHO City Action Group on Healthy Urban Planning. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pilkington P, Grant M, Orme J. Promoting integration of the health and built environment agenda through a workforce development initiative. Public Health. 2008;122(6):545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]