Abstract

Purpose

Fibular periosteal flaps have been used to address chronic lateral ankle instability, but there are no studies in the literature reporting functional outcomes after this particular procedure in high-demand athletes. We postulated that for chronic instability, nonanatomical reconstruction of the lateral ankle ligament with a fibular periosteal flap will return high-demand athletes to their previous levels of activity.

Methods

Forty patients who had grade III ankle sprain and experienced no success after a course of supervised conservative management lasting at least six months and who had a preinjury Tegner score of ≥6 underwent a lateral compartment reconstruction with a fibular periosteal flap. Each patient was given the Tegner and Karlsson questionnaire and was evaluated by the Zwipp method, Foot and Ankle Outcome Score (FAOS) and the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score at the six-month, one, two and three-year time points. Range of motion (ROM) of the affected ankle was assessed, and stress X-rays were performed. Mean patient age was 24.5 (range17–30) years, and no patient was lost to follow-up.

Results

Mean follow-up was 36 (minimum 18) months, mean Tegner scores at the one, two and three-year time points were 8.8, 8.9 and 8.9, respectively, and mean Karlsson scores were 93 ± 5.2, 95 ± 3.1 and 94.9, respectively. AOFAS and FAOS scores improved from a mean of 69.4 and 71.4, respectively, in the preoperative group to a mean of 97.2 and 94.4, respectively, at the last follow-up. The ROM was equal to the contralateral ankle in all but two patients at the two-year follow-up. No major complications were found.

Conclusion

Nonanatomical ligament reconstruction with a fibular periosteal flap for chronic lateral ankle instability was effective in returning high-demand athletes to their preinjury functional levels.

Keywords: Lateral ankle instability, High-demand athlete, Fibula periosteal flap, Functional outcomes

Introduction

Ankle sprains are amongst the most common injuries in the high-demand athlete, with a majority of cases involving the lateral ligamentous complex. The ankle is the second-most common anatomical site for sprains after the knee [1–5]. Therefore, much has been written about operative and nonoperative treatment of severe ankle sprains and the possible secondary chronic instability of the ankle [6–16]. The majority of patients will improve after a treatment protocol involving a period of rest and physical therapy. Different studies show that 10–20 % of patients will have chronic symptomatic ankle instability [2, 7, 17]. In the field of sport traumatology, treating high-demand athletes with chronic ankle instability who have failed a course of supervised, aggressive physical therapy, poses a great challenge. This study shows results at a mean of three years follow-up of reconstruction on grade III chronic ankle sprains using a periosteal flap as a variant of a previous technique described by Rudert et al. [15] in high-demand athletes.

Patients and methods

From January 2004 to June 2009, 40 athletes who presented with chronic ankle instability due to a lateral complex lesion underwent operative treatment of nonanatomical reconstruction with fibular periosteal flap. Of the 40 patients, 27 were men and 13 women. In 25 cases, the lesion was on the right side and in 15 on the left. Mean patient age was 24.5 (17–30) years, and mean follow-up was 36 (18–60) months. Only patients categorized as high-demand athletes were included in our study: 30 were professional; ten were nonprofessionals in high school or college. Sports involved were basketball, volleyball, soccer, track and field and others. All patients had grade III lateral ankle sprain. Thirty-eight patients were operated upon because they failed to improve after at least a full course of supervised conservative management that included rest, bracing, anti-inflammatory medications, proprioceptive training, ankle strengthening and formal physical therapy. Two patients where operated upon in the acute (four days) or subacute (15 days) phase because of an anterolateral capsular tear associated with the lateral ligamentous lesion. Each patient had a thorough history and physical examination. Range of motion (ROM) in both dorsiflexion and plantar flexion was performed subjectively by the operating surgeon on the injured ankle and compared with the contralateral ankle. Any decrease in ROM more than 5° from normal or more than 5° of difference from the contralateral ankle was documented. Provocative tests were performed on the injured ankle, such as the anterior drawer test, squeeze test and talar tilt test. All patients were evaluated pre- and postoperatively with stress X-rays to evaluate the anterior drawer test and talar tilt and talocalcaneal angle. A magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was obtained before surgery to confirm the anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) tear and a concomitant attenuation or tear at the calcaneofibular ligament (CFL) (present in 31 patients) and to determine whether there were any associated injuries or conditions, such as synovitis or osteochondral (OCD) lesions. Patients with associated lesions, such as synovitis, OCD lesions, bony avulsions or fractures, were excluded from our study.

Each patient was given a Tegner questionnaire at the initial visit to determine their preinjury and current or postinjury activity levels. Further inclusion criteria were a preinjury Tegner score 7 or more and an uninjured contralateral ankle: the mean preinjury Tegner score was 8.7(range 6–10), and mean postinjury Tegner score dropped to 5.4 (range 2–6). These patients underwent surgical repair of the lateral ankle ligament in which a fibular periosteal flap was used as a modification of the technique published by Rudert et al. [15]. Time to surgery averaged ten (range 15 days to two years) from the original injury. Postoperative results were evaluated using the method introduced by Zwipp et al., which includes both subjective and objective parameters. The AOFAS, FAOS and the Karlsson score were used [14]. All patients were evaluated pre- and postoperatively at three, six, nine and 12 months, then yearly with respect to the recovery to pre-injury activity level as the endpoint. All patients were treated with the same surgical technique performed by one of the two senior authors.

Surgical technique

A tourniquet is used during surgery to avoid bleeding

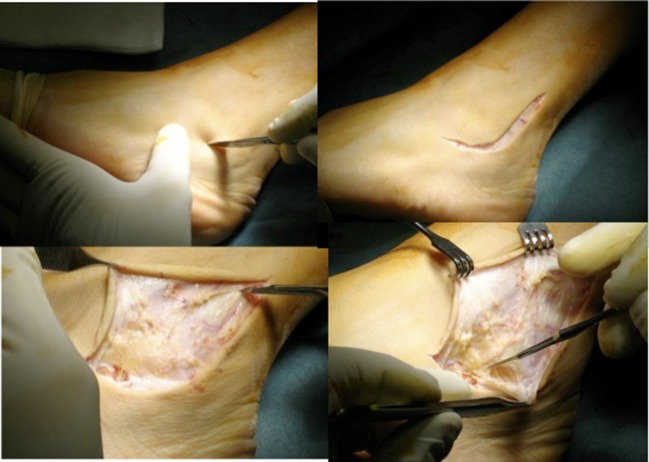

The surgical approach comprises a curved, L-shaped incision with an anterior concavity starting six centimetres proximally from the tip of the lateral malleolus, passing slightly posterior to the malleolus and ending about three centimetres distally from its tip to provide good exposure of the grafting site for the periosteal flap and for the ankle joint (Fig. 1)

Fig. 1.

Phases of the surgical approach

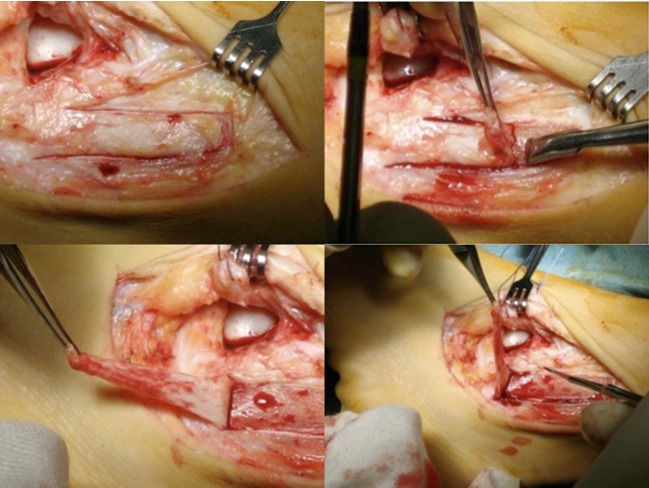

The periosteal flap is isolated proximally to distally for about five centimetres and the maximum width possible to split it in two if CFL ligament reconstruction is needed (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Isolation of the fibular periosteal flap

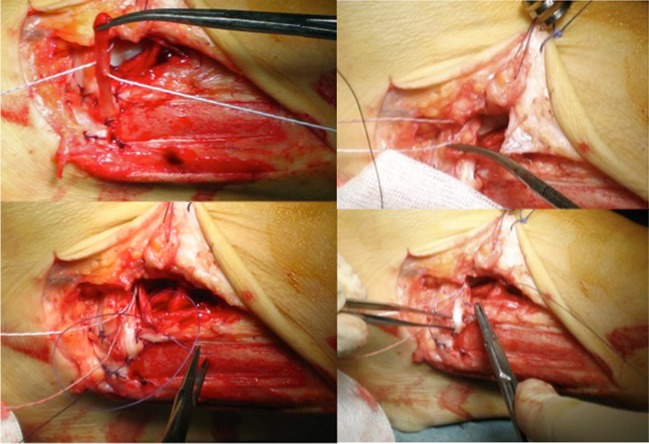

The fibular flap is turned, and at the two distal angles, two 2–0 or 3–0 Vicryl sutures are placed to reinforce the insertion and avoid stripping from the fibula when the neoligament is tensioned.

ATFL reconstruction varies according to whether or not a residual ligament is present. If so, it can be overlapped by the periosteal flap, with the foot in eversion, and sutured with 3–0 Vicryl separated stitches after anchoring it to the talus with a 2.8-mm titanium anchor. If there is no residual ATFL, it will be recreated de novo with the fibular flap. In both cases, if the neoligament is long enough, it can be doubled by fixing it to the talus at half its length and then turning the distal half back on the fibula (Fig. 3). Ligament fixation on the talus must be performed with the foot in slight eversion. Minor variations of the technique can be used according to the pathology found during surgery.

Fig. 3.

If a residual ligament is present, it can be overlapped by the periosteal flap, with the foot in eversion, and sutured with Vicryl 3–0 separated stitches after anchoring it to the talus with a 2.8-mm titanium anchor. If there is no residual anterior talofibular ligament (ATFL) it will be recreated de novo with the fibular flap. In both cases, if the neoligament is long enough, it can be doubled, fixing it to the talus at half of its length and then turning the distal half back on the fibula

A lesion of the CFL ligament is usually complete and the ligament difficult to recognise. The posterior half of the doubled flap is fixed distally and slight posteriorly from the tip of the malleolus on the calcaneum with a 2.8-mm titanium suture anchor. During reconstructive manoeuvres, the foot is kept in eversion to maintain a slight overcorrection to retain tension in the reconstructed structures. When a capsular lesion is found, repair with reabsorbable 2–0 Vicryl sutures can be performed. The postoperative protocol comprises several phases:

Immobilisation in a plaster cast with no weight bearing for three weeks

Weight bearing in a plaster cast for three weeks

Progressive ROM recovery starting from cast removal

Proprioceptive rehabilitation and muscle strengthening with isometric exercises first, then progressively isotonic, from day 50 postoperatively

Eccentric muscle strengthening from day 65 postoperatively

Beginning sport activity no earlier than four months postoperatively

Results

Thirty-eight athletes returned to their preinjury sports activity levels; two returned to a lower professional level compared with their preinjury status (men; soccer and basketball, respectively). Subjective evaluation according to Zwipp et al. [14] gave the following results:

No spontaneous pain in any patient, and no provoked pain in 39

No pain on walking

Slight pain after intense activity in two patients

No episode of ankle sprain

Complete functional recovery (in particular, of the sensation of stability) in all patients

Objective evaluation showed:

Negative Tinel test in all patients

Jump on a single foot possible in all patients

Anterior drawer test negative in all patients in comparison with contralateral ankle

Lateral tilt slightly positive in one patient, with no clinical counterpart

Negative modified Romberg test in all patients

FAOS evaluation considering the different subscales showed:

Mean of 93.8 in the pain subscale

Mean of 95.2 in the activities of daily living (ADL) subscale

Mean of 94.4 in the quality-of-life (QOL) sport subscale

Mean of 94.9 in the subscale

Mean of 96.1 for all other symptoms combined

Mean of 71.4 for preoperative FAOS score considering the different subscales

Mean of 97.2 for AOFAS, improved from a mean of 69.4 preoperatively

All patients returned to their preinjury Tegner scores of over 6 by the final follow-up. Mean Tegner scores at six months and one, two and three years were 7.9, 8.8, 8.9 and 8.9, respectively. Karlsson scores averaged 90 ± 6.4, 93 ± 5.2, 95 ± 3.1 and 94.9 at six months and one, two and three years, respectively, starting from a mean preoperative score of 78.2. By 1.5 years, ROM was equal to the contralateral ankle in all but two patients who showed a decrease in dorsiflexion and plantar flexion of 5–10°, but subtalar motion was preserved.

There was no major complication, such as recurrence or neurovascular injuries. One patient had a superficial wound infection successfully treated with antibiotics given orally and requiring no surgical irrigation or debridement. Stress X-rays performed six months postoperatively showed a talar tilt angle of 2.7 ° (±0.5°) against a 16.5° (±2.5°) angle preoperatively, and a talar–calcaneal angle ranging from 10.8° (±1,6°) preoperatively to 2.8° (±0.5°).

Discussion

Here we report results obtained with a specific technique for reconstructing the lateral compartment of the ankle in a group of high-demand athletes. Different surgical techniques are published in the literature to treat these types of injuries. We used the well-known technique published by Rudert et al. [15], which we slightly modified and adapted to the different anatomical conditions found at surgery. A recent meta-analysis [18] showed an advantage of surgery over conservative treatment in four areas: return to preinjury level, recurrence, chronic pain and subjective or functional instability. In high-demand patients, reducing these complications is of paramount importance, especially for professional athletes, which is the reason surgical treatment is mostly used in such patients. A paper by Li et al. [19] stresses three key points: return to preinjury level, need to use specific criteria to evaluate outcome, and reduction of comorbidity such as reduced subtalar motion and possible deterioration of function. Concerning this last point, those authors promote an anatomical technique that shows very good results.

Different studies show the advantages of using a nonanatomical technique, such as Watson–Jones or Chrisman-Snook reconstructions [15, 20–25], for high-demand athletes. In our study, we used five different scores in an attempt to compare results with those of the different studies published. We also decided to perform stress X-rays as an objective instrumental evaluation of outcomes [9]. All 40 of our patients were rated on the Tegner scale as 6 or more based on preinjury activity; 40 of 40 returned to that level of competition. Mean one and two year follow-up Karlsson scores rated functional results as good to excellent. Furthermore, ROM was well maintained in our study group. Only two patients had decreased ROM in plantar flexion and dorsiflexion of 5–10°, as measured on follow-up: their Tegner scores were greater than 6 and their Karlsson ankle scores over 90; they returned to their previous level of activity. No patient lost subtalar motion. Therefore, we believe that a decrease in ROM may not adversely affect the functional level.

Our results are not in line with the study published by Krips et al. [26], who compared anatomical versus nonanatomical repair for lateral instability in high-demand athletes. They found that anatomical repair resulted in significantly less-restricted ankle ROM in dorsiflexion (three vs 15 patients) and returned more athletes to their previous activity levels compared with the tenodesis group. Also, the number of patients rated good or excellent by the scoring system of Good et al. was significantly higher (36 vs 21 patients) in the anatomical repair group. A study published by Karlsson et al. [8] showed very good results after three years using a simple anatomical technique of shortening and reinserting the lateral ankle ligament. Although results were good to excellent results in 88 % of patients, the technique was not applied to high-demand athletes in whom, in our opinion, it could be less forgiving. The authors also conclude that this method should be used with great care in patients with generalised joint hypermobility or in patients with long-standing ligament insufficiency.

Our result are comparable with those presented by Li et al. [19] and Messer et al. [27] who found no evidence of instability on physical examination or stress radiographs in 14 of their 16 patients who underwent the modified Broström procedure with suture anchors for lateral ankle instability. Long-term follow-up of the Gould-modified Broström procedure also showed good to excellent results in all patients by Ferkel and Chams [28] at 60-months’ follow-up. In our study only two patients did not reach the same preinjury activity level but as professional athletes were able to return to high-level professional activity in a lower league.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to evaluate results of using the fibular periosteal flap technique on high-demand athletes with chronic lateral ankle instability; a similar study by Sjolin et al. [24] in 1991 showed a high percentage of positive results, but the study group was not composed exclusively of high-demand athletes.

There are some disadvantages of this technique, which are basically related to the postoperative protocol, which requires six weeks of plaster casting to allow the process of ligamentisation of the periosteal flap. The theoretical possibility of failure in this process of ligamentisation did not occur in our experience, as we found no recurrence or failure. The biggest issue surrounding the actual surgical technique is to obtain a good flap and to protect it from stripping of the distal end before overlapping it. Another important phase of the procedure is flap fixation and tensioning, which must be performed in a slight overcorrection. The advantage of this nonanatomical reconstruction technique is the possibility of avoiding complications and functional problems associated with other nonanatomical techniques, which moves some authors towards developing improved anatomical techniques [8, 14, 15, 19, 20, 29, 30].

According to results of our study, we can state that this technique produces results comparable with results of other nonanatomical techniques published in the literature and that are still considered by many authors to be the gold standard in high-demand athletes. As results were maintained at five years follow-up (mean three years) allows the possibility of guaranteeing to such patients the safe continuation of their careers.

Conclusions

Reconstructing the lateral ankle compartment with a fibular periosteal flap is, in our experience, a safe and reliable surgical solution to chronic lateral ankle instability in high-demand athletic patients and has a low complication and recurrence rate. The main goal for high-demand athletes is recovery to sport activity at the preinjury level, especially for professionals, and the possibility of maintaining or improving that activity level. According to our results, the technique appears to be a reliable compromise between anatomical and nonanatomical techniques for obtaining stability, recovering ROM and returning the patient to the preinjury level of activity. It is, however, important that specific attention be given to an appropriately designed postoperative protocol.

References

- 1.Balduini FC, Vegso JJ, Torg JS, Torg E. Management and rehabilitation of ligamentous injuries to the ankle. Sports Med. 1987;4:364–380. doi: 10.2165/00007256-198704050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barker HB, Beynnon BD, Renstrom PA. Ankle injury risk factors in sports. Sports Med. 1997;23:69–74. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199723020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferran NA, Maffulli N. Epidemiology of sprains of the lateral ankle ligament complex. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(3):659–662. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fong DT, Hong Y, Chan LK, Yung PS, Chan KM. A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports Med. 2007;37(1):73–94. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeung MS, Chan KM, So CH, Yuan WY. An epidemiological survey on ankle sprain. Br J Sports Med. 1994;28(2):112–116. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.28.2.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Good CJ, Jones MA, Livingstone BN. Reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle. Injury. 1975;7:63–65. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(75)90065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holmer P, Sondergaard L, Konradsen L, Nielsen PT, Jorgensen LN. Epidemiology of sprains in the lateral ankle and foot. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:72–74. doi: 10.1177/107110079401500204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson J, Bergsten T, Lansinger O, Peterson L. Lateral instability of the ankle treated by the Evans procedure: A long-term clinical and radiological follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70:476–480. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.70B3.3372575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karlsson J, Bergsten T, Lansinger O, Peterson L. Reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle for chronic lateral instability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70(4):581–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karlsson J, Peterson L. Evaluation of ankle joint function: The use of a scoring scale. Foot. 1991;1:15–19. doi: 10.1016/0958-2592(91)90006-W. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Konradsen L, Bech L, Ehrenbjerg M, Nickelsen T. Seven years follow-up after ankle inversion trauma. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2002;12:129–135. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0838.2002.02104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krips R, Van Dijk C, Lethtonen H, Halasi T, Moyen B, Karlsson J. Sports activity level after surgical treatment of chronic anterolateral ankle instability. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30:13–19. doi: 10.1177/03635465020300010801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu S, Baker CL. Comparison of lateral ankle ligamentous reconstruction procedures. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(3):313–317. doi: 10.1177/036354659402200303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pijnenburg AC, Bogaard K, Krips R, Marti RK, Bossuyt PM, van Dijk CN. Operative and functional treatment of rupture of the lateral ligament of the ankle: a randomized, prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85:525–530. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.85B4.13928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudert M, Wülker N, Wirth CJ. Reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle using a regional periosteal flap. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1997;79(3):446–51. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.79B3.7183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tegner Y, Lysholm J. Rating systems in the evaluation of knee ligament injuries. Clin Orthop. 1985;198:43–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Colville MR. Surgical treatment of the unstable ankle. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6:368–377. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199811000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kerkhoffs G, Handoll H, DeBie R, Rowe BH, Struijs PA. Surgical versus conservative treatment for acute injuries of the lateral ligament complex of the ankle in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2:CD000380. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000380.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li X, Killie H, Guerrero P, Busconi BD. Functional outcomes after the modified broström repair using suture anchors anatomical reconstruction for chronic lateral ankle instability in the high-demand athlete. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:488–94. doi: 10.1177/0363546508327541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bell SJ, Mologne TS, Sitler DF, Cox JS. Twenty-six-year results after Brostrom procedure for chronic lateral ankle instability. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(6):975–978. doi: 10.1177/0363546505282616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fujii T, Kitaoka HB, Watanabe K, Luo ZP, An KN. Comparison of modified Brostrom and Evans procedures in simulated lateral ankle injury. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2006;38(6):1025–1031. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000222827.56982.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riegler HF. Reconstruction for lateral instability of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66:336–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Snook GA, Chrisman OD, Wilson TC. Long-term results of the Chrisman-Snook operation for reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1985;67(1):1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sjolin Sjølin SU, Dons-Jensen H, Simonsen O. Reinforced anatomical reconstruction of the anterior talofibular ligament in chronic anterolateral instability using a periosteal flap. Foot Ankle. 1991;12(1):15–8. doi: 10.1177/107110079101200103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vainionpää S, Kirves P, Läike E. Lateral instability of the ankle and results when treated by the Evans procedure. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8(6):437–439. doi: 10.1177/036354658000800610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Krips R, Van Dijk C, Halasi T, et al. Anatomical reconstruction versus tenodesis for the treatment of chronic anterolateral instability of the ankle joint: A 2- to 10-year follow-up, multicenter study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2000;8(3):173–179. doi: 10.1007/s001670050210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Messer TM, Cummins CA, Ahn J, Kelikian AS. Outcome of the modified Brostrom procedure for chronic lateral ankle instability using suture anchors. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21(12):996–1003. doi: 10.1177/107110070002101203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ferkel R, Chams R. Chronic lateral instability: Arthroscopic findings and long-term results. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(1):24–31. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Korkala O, Lauttamus L, Tanskanen P. Lateral ligament injuries of the ankle: Results of primary surgical treatment. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1982;71(3):161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lauttamus L, Korkala O, Tanskanen P. Lateral ligament injuries of the ankle: Surgical treatment of late cases. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1982;71(3):164–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]