Abstract

Hindfoot malunions after fractures of the talus and calcaneus lead to severe disability and pain. Corrective osteotomies and arthrodeses aim at functional rehabilitation and reduction of pain resulting from post-traumatic arthritis, eccentric loading and impingement due to hindfoot malunion. Preoperative analysis should include the three-dimensional outline of the malunion, the presence of post-traumatic arthritis, non-union, or infection, the extent of any avascular necrosis or comorbidities. In properly selected, compliant patients with intact cartilage cover little or no, AVN, and adequate bone quality, a corrective joint-preserving osteotomy with secondary internal fixation may be carried out. In the majority of cases, realignment is augmented by arthrodesis for post-traumatic arthritis. Fusion is restricted to the affected joint(s) to minimise loss of function. Correction of the malunion is achieved by asymmetric joint resection, distraction and structural bone grafting with corrective osteotomies for severe axial malalignment. Bone grafting is also needed after resection of a fibrous non-union, sclerotic or necrotic bone. Numerous clinical studies have shown substantial functional improvement and high subjective satisfaction rates from pain reduction after corrective osteotomies and fusions for post-traumatic hindfoot malalignment. This article reviews the indications, techniques and results of corrective surgery after talar and calcaneal malunions and nonunions based on an easy-to-use classification.

Keywords: Hindfoot malalignment, Post-traumatic arthritis, Corrective arthrodesis, Osteotomies

Introduction

Post-traumatic malalignment of the hindfoot results from malunited fractures of the talus and calcaneus and regularly leads to severe disability and pain. This article reviews the options for surgical corrections of hindfoot malunions. These include a wide range of procedures ranging from joint-preserving corrective osteotomies and secondary internal fixation to fusion of one or more joints with axial realignment and bone grafting, sometimes combined with additional osteotomies and soft tissue procedures.

In order to obtain optimal functional results, patients have to be evaluated carefully with respect to comorbidities, compliance, substance abuse, activity level and functional demands. Clinical examination focuses on gross deformity, soft tissue status, callosities, range of motion in the ankle, subtalar, and talonavicular joints, and neurovascular deficits. Bilateral weight-bearing radiographs of the foot and ankle, and a hindfoot alignment view are obtained. The amount and apex of axial malalignment, the degree of post-traumatic arthritis, the amount of avascular necrosis (AVN), and overall quality of bone stock are noted. Computed tomographic (CT) scanning reveals joint incongruities, the extent of arthritis and bony union, and the exact planes of malunion for planning the correction [1, 2]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to determine the presence and extent of suspected AVN and soft-tissue entrapment associated with talar malunion. Routine leukocyte counts and serum levels of C-reactive protein should be obtained for all patients to rule out infection.

Correction of Talar Malunions

The integrity of the talus and its joints is essential for global foot function. Consequently, malunions of the talus are debilitating conditions for the affected patients. Post-traumatic malalignment results from inadequate fracture reduction or fixation. Non-operative treatment for even slightly displaced talar neck fractures will lead to a symptomatic malunion in about half of the cases [3–5]. Non-union of the talar neck or body is seen in less than 10 % in most series [1, 4]. Fractures of the lateral and posterior processes are frequently overlooked at first presentation and if displaced will rapidly lead to symptomatic arthritis of the subtalar joint [6, 7]. Malunions of the talar head result from overlooked or underestimated fracture-dislocations at the mid-tarsal (Chopart) joint and severely affect function of the talonavicular joint [8, 9]. In addition, malaligned bony fragments or osteophytes lead to impingement of the posterior tibial tendons, tarsal tunnel or sinus tarsi syndrome [10].

A typical deformity after talar neck fractures is varus malalignment secondary to medial comminution at the time of the accident. If the fracture is treated nonoperatively, reduced inadequately due to limited surgical exposure, or fixed inadequately with lag screws, shortening of the medial part of the talus results. Varus malalignment of the hindfoot decreases the mobility of the mid-tarsal and subtalar joints, and compromises the normal relationship between the hindfoot and forefoot [11]. Other deformities that are encountered after incomplete reduction of talar neck fractures include dorsal displacement and depression of the talar body with incongruity in the ankle and subtalar joints [3, 10]. Biomechanical investigations have shown that malalignment of as little as two millimetres at the talar neck results in significant load redistribution between the posterior, medial and anterior facets of the subtalar joint, potentially leading to post-traumatic arthritis [12].

Malunited talar body fractures result in direct step-offs in the ankle and subtalar joints with a high risk of the development of arthritis. The rates of arthritis after talar neck and body fractures provided in the literature vary considerably from 16 to 100 % and appear to increase over time; the reported rates of secondary arthrodesis range between 0 and 33 % of cases [7].

Avascular necrosis (AVN) of the talar body is a specific complication of talar neck and body fractures and is seen to some extent in about 50 % of cases. The reported rates of AVN appear to be dependent on the initial amount of dislocation, which is more pronounced after talar neck fractures than talar body fractures [5, 13, 14]. It is now known that, the rates of AVN can be lowered by early, stable internal fixation and functional aftertreatment as compared to earlier studies. While areas of reduced blood supply can be found with MRI in almost all cases, only total AVN of the talar body eventually leading to collapse of the talar dome becomes clinically relevant [1, 13–16]. With partial AVN, creeping substitution will gradually replace most of the necrotic areas but asymptomatic AVN persists in many cases [4]. For planning corrective procedures after talar malunions, it is therefore important to distinguish between partial AVN with less than approximately one third of the talar body affected, and total AVN, resulting in a collapse of the talar body [10].

Indications

The choice of the best treatment for post-traumtic talar deformities depends on patient-related factors including the amount of post-traumatic arthritis, avascular necrosis, infection and the quality of bone stock, patient compliance and limiting comorbidities. Using these data, a simple classification can be used to plan the correction (Table 1).

Table 1.

Classification of post-traumatic deformities of the talus and options for surgical correction [10, 17]. AVN is considered partial, if less than one third of the talar body is involved

| Type | Features | Treatment options | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active, reliable patient, no symptomatic arthritis | Noncompliant patient, comorbidities, arthritis | ||

| I | Malunion and/or joint displacement | Osteotomy, secondary reconstruction and internal fixation with joint preservation | Corrective fusion of the affected joint(s) |

| II | Non-union with displacement | ||

| III | Types I/II with partial AVN | ||

| IV | Types I/II with complete AVN | Necrectomy, (vascularised) bone grafting, corrective fusion | |

| V | Types I/II with septic AVN | Radical debridement(s), bone grafting, corrective fusion | |

Secondary anatomical reconstruction and internal fixation with preservation of all three joints can be pursued in active, compliant patients with type I–III deformities. In the presence of symptomatic arthritis, with poor patient compliance or bone stock, and relevant comorbidities such as poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, stage IIb peripheral vascular disease, or systemic immune deficiency, fusion of the affected joint(s) with axial realignment is the treatment of choice. Because radiographic arthritis is not always clinically symptomatic and malalignment of the talus and its joints will invariably lead to severe pain around the ankle and hindfoot, the decision to reconstruct or fuse one or more peritalar joints will frequently be made intraoperatively while directly assessing cartilage loss and probing cartilage quality. Therefore both joint reconstruction and fusion must be discussed with the patient prior to surgery [1]. For the ankle joint, total ankle replacement is another treatment alternative.

In the presence of a complete AVN and collapse of the talar body (type IV deformities), excision of all necrotic bone, autologous bone grafting, realignment and fusion of the affected joint(s) is the treatment of choice. In cases of osteomyelitis (type V deformities) repeated debridements of infected and necrotic bone will result in a subtotal talectomy. In staged procedures tibiocalcaneal or tibiotalocalcaneal fusion is peformed after negative swabs have been obtained with proper debridement and lavage. Whenever possible, the talar head and the talonavicular joint are preserved.

Early malunions and nonunions of talar process fractures can be salvaged by complete excision of the malunited fragments [6, 18]. However, symptomatic subtalar arthritis develops rapidly after these injuries and in situ fusion of the subtalar joint may become necessary [7, 19].

Techniques

Secondary anatomical correction (Fig. 1) of properly selected type I–III malunions and nonunions of the talar head, neck and body is carried out through the same surgical approaches that are used in acute fractures [5, 14, 16, 20]. The talar neck and head are exposed via an anteromedial approach. For full exposure of the talar dome, a medial malleolar osteotomy is added. The lateral part of the talar neck and body including the lateral process and subtalar joint are accessed via a curved or oblique anterolateral approach [20]. Posterior approaches are used for malunions of the posterior process or the posterior third of the talar body [5, 6]. In most cases, a posterolateral approach allows a complete overview of the posterior part of the talar body. The flexor hallucis longus muscle and tendon are held away medially thus protecting the tibial neurovascular bundle. A femoral distractor with Schanz screws placed into the tibia and the calcaneus is extremely helpful to gain adequate overview of the ankle and subtalar joint surfaces.

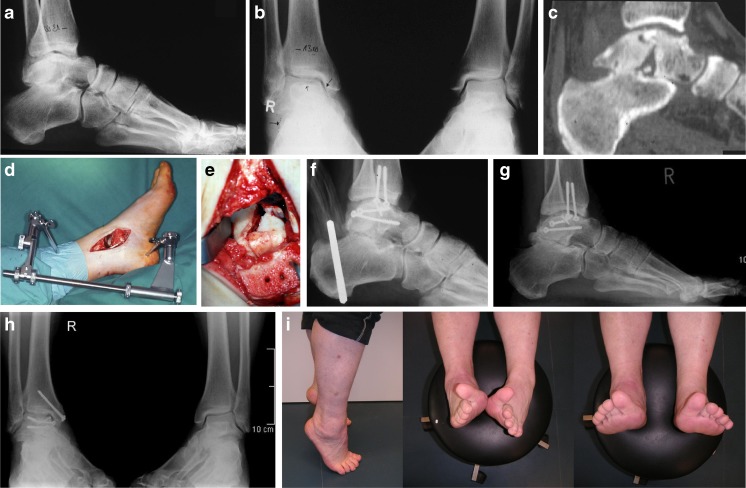

Fig. 1.

a–c Talar malunion (type I) with incongruity of the ankle and subtalar joints secondary to a displaced talar body fracture three months previously. d–e A medial malleolar osteotomy is carried out and a femoral distractor is used to obtain a good overview of the ankle and subtalar joints. f The talar dome can be corrected anatomically at the ankle, the subtalar joint is reduced congruent to the posterior facet of the calcaneus but a defect remains after removal of small fragments. g–i Seven years later the patient is pain free during activities of daily living with only mildly restricted subtalar motion despite radiographic signs of post-traumatic arthritis

The cartilage at the ankle, subtalar, and talonavicular joint surfaces is inspected and probed in all accessible parts. Smaller, superficial lesions may be treated with curettage and drilling or microfracturing techniques. Loose fragments are excised. If a full-thickness defect of the weight-bearing area is present, the affected joint is fused after correction of the deformity. Fibrous intra- and extra-articular adhesions around the talus are released and tenolysis or lengthening of the deep flexor tendons or the Achilles tendon is carried out, if necessary.

The plane of the former fracture, as assessed preoperatively by CT scanning, is exposed. Care is taken not to compromise the blood supply to the talar body around the deltoid ligament, the sinus and canalis tarsi. If a solid malunion is present (type I), an osteotomy along the former fracture plane is carried out step-wise and carefully using small osteotomes. If a non-union is present (type II) the fibrous pseudoarthrosis and underlying sclerotic bone are completely resected until viable cancellous bone becomes visible. The viability of the talar body is then checked after osteotomy or debridement of the non-union with the tourniquet released. Avascular areas of the talar body in type III malunions may require curettage and drilling in order to enhance bone remodelling. The resulting defect is filled with bone graft to avoid shortening or axial deviation [1]. The main fragments are manipulated with K-wires that are used as joy sticks rather than direct clamping to avoid damage to the joint surfaces or further fragmentation. Anatomical reconstruction of the talar neck and the joint surfaces are assessed visually through the bilateral approaches. After temporary fixation with K-wires, axial realignment of the talus is controlled fluoroscopically. Parts of the subtalar joint that are not directly visible despite distraction can be viewed by open arthroscopy using a small-diameter arthroscope or three-dimensional fluoroscopy.

Malunited fractures of the talar head are typically the result of a malunited mid-tarsal (Chopart) fracture-dislocation with residual incongruity of the talonavicular joint [9]. Correction is carried out via an anteromedial or dorsomedial approach to the talonavicular joint. Reconstruction of the talar head aims at preservation of the talonavicular joint and re-establishment of the relation between the medial and lateral columns of the foot.

After anatomical reduction has been checked, fixation of the main fragments is achieved using 2.7–3.5-mm screws. Alternatively, a minfragment plate is applied medially to bridge a former comminution zone or stabilise a rather small talar head fragment. Correct implant position is monitored fluoroscopically, preferably in a 3D mode. Aftertreatment aims at early motion of the ankle, subtalar and mid-tarsal joints. Patients are mobilised under partial weight-bearing of 15–20 kg for ten to 12 weeks postoperatively. The presence of a pre-existing partial AVN should not prolong the period of partial weightbearing and does not appear to influence the functional result of corrective surgery [1].

In a sizeable number of type I–III talar malunions and non-unions, obvious post-traumatic arthritis will be present at the time of patient presentation. For these patients, axial realignment of the talus and fusion of the affected joint(s) is the treatment of choice [7, 21]. Total ankle replacement is a viable treatment option for symptomatic ankle arthritis if the bone stock of the tibia and talus is preserved and no gross deformity is present. Total ankle replacement should be considered in particular, if the subtalar and talonavicular joints are arthritic and need to be fused in order to avoid a pantalar fusion and thus a totally stiff ankle/hindfoot complex. Ankle replacement together with subtalar and/or talonavicular fusion can be carried out either as a single step or a staged procedure [22].

To achieve optimal functional rehabilitation, ankle fusion should be performed with the foot in neutral alignment in the coronal plane and in neutral to slight valgus (0–5°) in the sagittal plane [23]. The ankle joint is accessed via an anterior or lateral (transfibular) approach [24]. The anterior capsule is resected and the joint surfaces are debrided from the remaining cartilage, sclerotic and necrotic bone. Significant malalignment is corrected by asymmetric bone resection, closed or open wedge osteotomy through the plane of the ankle joint and the use of cancellous or corticocancellous bone graft, if necessary. After temporary fixation with a 2.5-mm K-wire, tibiotalar alignment in the coronal and sagittal planes is monitored fluoroscopically. To avoid fusion in equinus, the angle formed by the tibial axis and the inferior aspect of the talus in the lateral view should be less than 115°. In both the anteroposterior and lateral views, the centre of the talar dome should line up with the centre of the tibial axis [23, 25–27]. Arthrodesis is achieved with two to five large fragment (6.5–7.3 mm) cancellous screws, or plates [8, 24, 28, 29].

Malunions of the talar body, the lateral process, and posterior process will frequently lead to symptomatic subtalar arthritis. In cases of malunited lateral or posterior process fractures and progressive cartilage wear after subtalar dislocations, in situ fusion of the subtalar joint is the treatment of choice. With talar inclination and loss of height, all sclerotic or necrotic bone are removed from the subtalar joint; reestablishment of the talocalcaneal height is achieved with a subtalar bone block fusion preferably via a posterolateral approach [7]. The hindfoot must be aligned in its physiological valgus to avoid tilting of the talus in the coronal plane [10]. Stable fusion is usually achieved with two large fragment screws introduced percutaneously from the calcaneus into the talar body.

Talonavicular arthrodesis becomes necessary in cases of malunited intra-articular talar head fractures associated with symptomatic arthritis of the talonavicular joint. It is carried out via an anteromedial or medial approach. Fusion is achieved with screws or small plates. Corrective fusion aims to re-establish the relationship between the medial and lateral foot columns because a mismatch between the two will result in three-dimensional deformities at the midfoot and hindfoot [10, 24].

In type IV deformities, total AVN of the talar body and considerable bone loss will eventually lead to a collapse of the talar dome with loss of height, and axial malalignment at the hindfoot and midfoot (Fig. 2). Resection of all non-viable bone is followed by bone grafting and corrective fusion [7, 13, 21]. If both the ankle and subtalar joints need to be fused, every effort should be made to preserve the talar head and the talonavicular joint as part of the “coxa pedis” [10]. Total talectomy and introduction of a large bone block do not appear to result in higher fusion rates than fusion around the remaining body after excision of all necrotic tissue [13].

Fig. 2.

a Talar malunion (type IV) with AVN leading to collapse of the talar dome and severe arthritis at the ankle joint. b Treatment consists of corrective ankle fusion with interposition of two tricortical bone blocks to restore height

With complete collapse of the talar body, post-traumatic arthritis of both the ankle and subtalar joints, or subtotal talectomy after post-traumatic infection, tibiotalocalcaneal or tibiocalcaneal fusion is the treatment of choice [7, 30]. In cases of osteomyelitis or septic AVN (type V deformity), aggressive debridement, temporary external fixation, and implantation of local antibiotic beads are carried out to eradicate infection. Fusion is then performed as a staged procedure after the infection has resolved, typically with bone grafting, screws, plates, a retrograde intramedullary nail, or external fixation with a large-pin or small-wire frame [7, 30–33]. In cases of tibiocalcaneal arthrodesis, excessive loss of height can be avoided by corticocanellous bone grafting or by sliding a portion from the anterior tibia distally into the defect (Blair fusion [34]). The talar head should be preserved if possible and fused to the anterior aspect of the tibia or bulk bone graft in order to maintain some residual motion through the talonavicular joint. Aftertreatment is tailored individually to the bone quality and the amount of bone grafting required. Partial weight-bearing of 15–20 kg is usually maintained for six to 12 weeks postoperatively in a lower-leg cast or special arthrodesis boot [23]. Physical therapy aims to achieve a compensatory range of motion through the remaining joints.

Results

A first series of ten patients treated with secondary anatomical correction of talar malunions was published in 2005 [1]. Meanwhile, in a series of 22 joint-preserving corrections for selected type I–III malunions and non-unions, we have observed neither development nor progression of AVN. In 12 of 20 patients (60 %) that were followed up for a mean of 4.8 years, progression of arthritis has been noted. However, late fusion of the ankle, subtalar, or talonavicular joint was necessary in only three patients between 1.5 and eight years after correction of the malunion [17]. Similar results have meanwhile been reported by others using the same treatment protocol in 21 patients followed for an average of 14 months [35]. Similarly, Suter et al. [36] saw substantial pain relief and improved functional outcome scores at four years follow-up in seven patients with talar neck osteotomy and grafting for medial shortening. The authors observed no subsequent avascular necrosis or radiographic arthritic changes. Radiographic union of the talar neck osteotomy occurred in six of seven patients, while implant removal was performed in three patients

Corrective arthrodesis with proper realignment and aftertreatment leads to predictable functional rehabilitation of the patients with talar malunion [7, 10, 13, 21]. Using the techniques described above, fusion rates of more than 90 % have been reported in numerous studies over the last 20 years including patients with post-traumatic arthritis after talar fractures [23]. Even after complete talectomy, some residual motion can be achieved through a neo-articulation between the tibia and the navicular, provided that good hindfoot alignment can be achieved [7, 37].

Correction of calcaneal malunions

Nonoperative treatment and inadequate reduction of displaced intra-articular calcaneal fractures regularly results in painful malunion with numerous complications resulting from the pathomechanics of these injuries. Residual articular incongruity rapidly leads to subtalar and calcaneocuboid arthritis. Hindfoot malalignment results from displacement of the calcaneal tuberosity, typically in varus and shortening [38]. The original fracture mechanism with axial impaction leads to a loss of calcaneal height leading to anterior ankle impingement because of the talar inclination and heel widening with bulging of the lateral wall resulting in lateral subfibular abutment and peroneal tendon impingement [39, 40].

Calcaneal fracture-dislocations with lateral and upward displacement of the whole tuberosity produce chronic peroneal tendon dislocation and sometimes a deformity of the distal fibula from direct impaction [41, 42]. Chronic soft tissue distension and scarring from calcaneal deformities may lead to irritation of the posterior tibial or sural nerves [43]. These conditions severely affect function of the ankle, subtalar, and calcaneocuboid joints resulting in an altered gait pattern most notably on uneven ground and problems with normal footwear [44]. The patients regularly report disabling pain at the tip of the lateral malleolus. On clinical examination they are tender to palpation in the sinus tarsi and subfibular region as well as along the peroneal tendons [38].

Indications

Similar to talar malunions, treatment of calcaneal malunions should be tailored individually to the specific sequelae associated with calcaneal malunions, the patient’s functional demands, compliance, and comorbidities. Stephens and Sanders [38] were the first to develop a classification system and treatment protocol for calcaneal malunions based on CT scans. Type I malunions included a large lateral wall exostosis, with or without far lateral subtalar arthrosis. Type II malunions included a lateral wall exostosis and post-traumatic subtalar arthrosis involving the entire joint. Type III malunions included a lateral wall exostosis, subtalar arthrosis, and malalignment of the calcaneal body resulting in significant hindfoot varus or valgus angulation. They proposed a lateral wall exostectomy and a peroneal tenolysis (as originally described by Cotton in 1921 [45]) for type I malunions, an additional subtalar bone block fusion using the excised lateral wall as autograft for type II malunions, and an additional Dwyer calcaneal osteotomy [46] to correct hindfoot malalignment in type III malunions.

In order to address all types of calcaneal malunions, Zwipp and Rammelt [10, 41] have developed a classification system with five types of deformities (Table 2). The bone quality for each type is encoded with an additional letter. Rarely, extra-articular malunions or intra-articular malunions with remaining viable cartilage may be treated with joint-sparing corrective osteotomy and secondary internal fixation [47]. These malunions may be collectively termed “type 0”.

Table 2.

Classification of post-traumatic deformities of the calcaneus (modified from Zwipp & Rammelt [10]) and options for surgical correction [42]. The quality of the bone may be encoded with an additional letter for each type of malunion

| Type | Characteristics | Treatment options | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Extra-articular or intra-articular malunion without arthrosis | Joint-preserving osteotomy | A Solid malunion |

| I | Subtalar joint incongruity with arthrosis | Subtalar in situ fusion | |

| II | Additional hindfoot varus/valgus | Subtalar bone-block fusion (+ osteotomy) | |

| III | Additional loss of height | Subtalar bone-block fusion (+ osteotomy) | B Nonunion |

| IV | Additional lateral translation of the tuberosity | Oblique calcaneal osteotomy with subtalar fusion | |

| V | Additional talar tilt at the ankle joint | Ankle revision, subtalar bone block fusion and osteotomy | C Necrosis |

Type I deformities with painful subtalar arthritis (similar to Stephens & Sanders type II) can be treated successfully with subtalar in situ fusion, which may be accompanied by decompression of the lateral wall and peroneal tendon tenolysis in case of a painful exostosis.

Type II malunions (similar to Stephens & Sanders type III) require a corrective subtalar fusion. Varus or valgus malalignment is corrected either by asymmetric joint resection, introduction of wedge-shaped bone blocks or an additional osteotomy through the tuberosity.

Type III malunions are treated with a subtalar distraction bone block arthrodesis to re-establish calcaneal height and relieve anterior tibiotalar impingement [39, 44]. Regularly, these malunions are combined with varus or valgus deformity. With severe loss of height or varus/valgus malalignment, an additional corrective osteotomy may be required [8, 42].

Type IV malunions result from fracture-dislocations of the calcaneus with lateral, upward and posterior dislocation of almost the whole calcaneal body. The treatment of choice is a corrective osteotomy along the former fracture plane and subtalar fusion [42, 48]. Bony correction is combined with rerouting of the displaced peroneal tendons behind the tip of the fibula and reconstruction of the superior peroneal retinaculum.

Type V malunions display a varus tilt of the talus within the ankle mortise resulting from extreme depression and deformity of the calcaneal body. These conditions require revision of the ankle joint via an additional anterior midline incision with careful debridement of all ingrown tissue followed by stepwise realignment of the talus and calcaneus and corrective subtalar fusion via bilateral approaches [8, 41].

Solid unions (A) are treated by corrective osteotomies and fusion as described above. In case of nonunions (B) these corrective procedures are preceded by debridement of the fibrous pseudoarthrosis and supplemented by bone grafting. Avascular necrosis of the calcaneus (C) is very rare and requires radical necrectomy followed by step-wise realignment that may require corticocancellous or vascularised bone grafting. If chronic infection is suspected, the procedure is staged with temporary implantation of antibiotic PMMA-beads or cement. Achilles tendon lengthening may be necessary in severe deformities in type II–V malunions.

Techniques

In type I malunions with isolated post-traumatic arthritis, in situ fusion of the subtalar joint can be carried out via an oblique lateral, extended lateral or posterolateral approach. For removal of a lateral plate, lateral wall exosectomy and peroneal tenolysis the patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position and an extensile lateral approach is over the lateral calcaneal wall as in open reduction and internal fixation of acute fractures [49]. The lateral wall exostectomy starts posteriorly and the osteotome or oscillating saw is directed slightly medially relative to the longitudinal axis of the calcaneus to release subfibular impingement. The talofibular joint is protected by a blunt retractor. A large fragment may later be used as autograft for subtalar fusion. The peroneal tendons are gently freed from adhesions along the lateral calcaneal wall. In patients with post-traumatic arthritis, the subtalar joint is debrided of remaining cartilage and sclerotic bone and the subchondral bone is perforated with a small drill bit to promote vascular ingrowth. In patients with a type II malunion, a closing wedge osteotomy is performed for varus malalignment, and a medial displacement calcaneal osteotomy is performed for valgus malalignment [38]. The subtalar joint is fused in neutral to slight valgus alignment with two large (6.5–8.0-mm) partially threaded cancellous screws placed via stab incisions from the posterior calcaneal tuberosity into the talar dome and neck.

Type III malunions with loss of height are treated with a subtalar distraction bone block fusion (Fig. 3) preferably over a posterolateral (Gallie) approach [50] with the patient in the prone position [39]. This incision allows good assessment of the hindfoot axis with respect to the lower leg and wound closure without tension even if considerable lengthening is needed. One or two tricortical bone blocks are harvested from the posterior iliac crest and inserted pressfit into the subtalar joint after debridement. Slight varus or valgus deformities can be corrected via the shape and size of the bone grafts; more pronounced axial malalignment requires an additional osteotomy [38, 42]. Similarly, extreme upward displacement of the tuberosity will require an additional vertical osteotomy of the calcaneal tuberosity to re-establish the lever arm for the Achilles tendon and the plantar aponeurosis and the longitudinal arch of the foot [8, 42, 51]. Fixation of the subtalar fusion is achieved with two 6.5-mm fully-threaded cancellous screws, and additional screws are needed for fixation of an osteotomy.

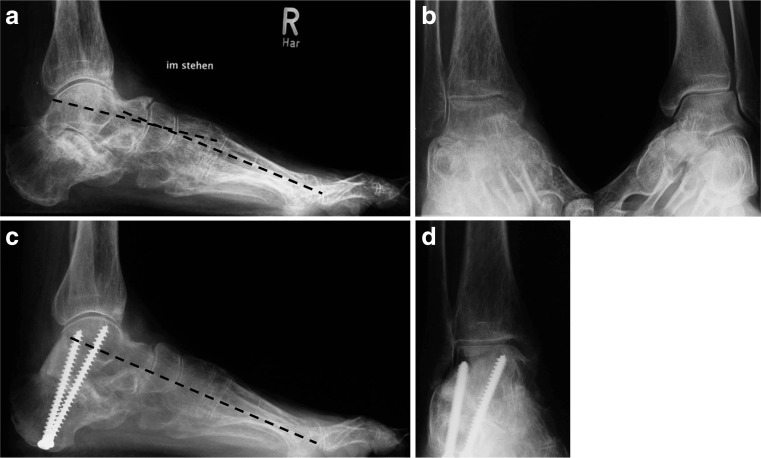

Fig. 3.

a,b Type III calcaneal malunion with severe loss of height after nonoperative treatment. c,d Subtalar distraction bone block arthrodesis leads to a restoration of height with correction of the talus-first metatarsal axis in the lateral radiographs

Type IV malunions or nonunions after fracture-dislocations of the calcaneus are best treated with a corrective three-dimensional osteotomy (Fig. 4) in a modification of the technique described by Romash [48]. Re-alignment includes a medial, anterior and plantar shift of the displaced calcaneal body with stable refixation to the sustentaculum fragment, which is the only portion of the calcaneus that is still in place. This manoeuvre also restores the calcaneal height, width, and axial alignment [41, 42]. The patient is placed either prone or supine, allowing bilateral approaches and manipulation. The lateral incision begins over the lateral malleolus and extends in a curved manner along the course of the peroneal tendons to the calcaneocuboid joint as described for acute fracture dislocations [52]. If a lateral plate has to be removed, the original extensile approach is used and a full-thickness fasciocutaneous flap is raised. The dislocated peroneal tendons are carefully identified in the subcutaneous tissue and freed from adhesions. To clearly identify the former fracture line in cases of solid malunions, an additional medial (McReynolds) approach is helpful. The tibial neurovascular bundle is identified and held away cranially with the flexor hallucis longus tendon while the medial wall is carefully exposed. The malunited fracture presents as a deep groove on the medial calcaneal wall. The fracture plane is marked with a Kirschner wire and the correct position is verified fluoroscopically with an axial view. The osteotomy is carried out with a standard osteotome, preferably from medial to lateral to avoid damage to the neurovascular bundle running near the medial fracture line. In some instances the wide gap between the sustentacular and tuberosity fragments leads to a manifest non-union. In these cases all fibrous and loose tissue is debrided until viable cancellous bone becomes visible. From the subtalar joint surfaces any remaining cartilage and sclerotic bone is removed.

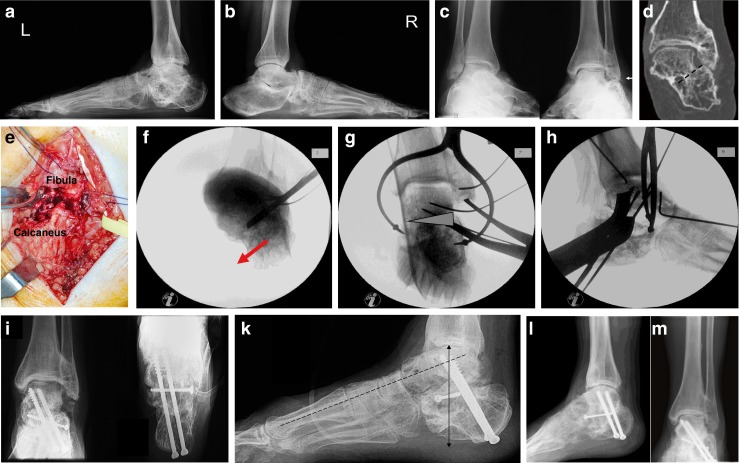

Fig. 4.

a,b Malunited fracture dislocation (Type IV malinion) in a 42 year old female patient one year after a fall from a height. The lateral radiographs reveal loss of height and shortening of the left calcaneus. c The ankle AP radiographs show lateralisation of the calcaneal body with direct deformation of the distal fibula. d CT scanning reveals the exact outline of the former fracture line. e After performing a lateral approach, the direct contact between fibula and calcaneus is seen. The peroneal tendons (held with a soft strap) are typically displaced subcutaneously. f Treatment consists of an oblique osteotomy along the former fracture plane that corrects all aspects of the malunion. g Subtalar fusion is supplemented by bone grafting from lateral (wedge) and screw fixation (h) across the former fracture into the sustentaculum. Additional soft tissue procedures in this case included Achilles tendon lengthening, ankle arthrolysis with lateral debridement and osteophyte excision, and peroneal tendon rerouting. i,k Postoperative radiographs show correction of the calcaneal axis in all three planes and restoration of the talocalcaneal height (double arrow) and talus-first metatarsal axis (interrupted line). l,m Four years later the radiographs show solid union in the corrected position without notable progression of the pre-existing ankle arthritis. Function is widely restored and pain markedly reduced

After completion of the osteotomy or debridement of the pseudoarthrosis, the large bony fragment is freed from any fibrous adhesions and gradually shifted downwards and medially. Lengthening of the Achilles tendon may be necessary and is then carried out as a Z-plasty via two or three stab incisions. Mobilisation and reduction of the calcaneal body may be difficult to achieve because of massive soft tissue retraction. Therefore, correction is carried out stepwise and helped by leverage with a smooth or sharp elevator introduced like a shoehorn into the osteotomy site. A femoral distractor placed between the distal aspect of the tibia and the medial part of the calcaneal tuberosity further assists correction. A laminar spreader introduced between the superior aspect of the calcaneal body and the undersurface of the talus or the tip of the fibula finally helps achieving restoration of the talocalcaneal height and allow measurement of the size of a bone block needed for correction. When reduction of the calcaneal body has been achieved, a large, curved bone reduction forceps is placed between the sustentaculum tali and the lateral wall of the calcaneus, and the main fragments are fixed temporarily with 2.0-mm K-wires. Restoration of the shape of the calcaneus is verified by intraperative lateral and axial or three-dimensional fluoroscopic images. Any remaining defect in the subthalamic portion of the calcaneus is filled with autologous bone graft from the anterior iliac crest. Fixation of the main fragments and fusion of the calcaneus to the talus is usually achieved with cancellous 4.5–6.5-mm lag screws. Finally, the peroneal tendons are rerouted behind the lateral malleolus and the superior peroneal retinaculum is reconstructed. Standard lateral and axial radiographs are obtained to verify correct hindfoot alignment and screw position.

Type V malunions require an additional anteromedial or midline approach to the ankle. The joint is cleared from capsular adhesions and fibrous tissue and the talar body is mobilised. With the cartilage still viable, the ankle joint can be salvaged in most instances. The malunion of the calcaneus is reduced step-wise as described above according to the individual deformity, and the talus is lifted gradually from inside the calcaneal body via bilateral incisions while carefully preserving its blood supply as highlighted above. After adequate reduction of the calcaneus and talus the subtalar joint is fused with screws and additional bone grafting. The lateral ankle ligaments are reefed as required.

Extra-articular malunions and selected intra-articular malunions with remaining viable cartilage may be treated with joint-sparing corrective osteotomies and secondary internal fixation [47]. Extra-articular malunions mostly result from fractures of the tuberosity behind the posterior facet of the subtalar joint. The tuberosity is usually displaced cranially. The deformity is approached from lateral side over the former fracture plane, where the osteotomy is carried out. The tuberosity is gradually shifted plantarwards after carefully freeing it from fibrous adhesions and percutaneous Achilles tendon lengthening. Fixation is achieved with partially-threaded cancellous screws.

In rare cases of malunited intra-articular calcaneal fractures and fracture-dislocations, joint-preserving corrective osteotomies are feasible. In our experience this requires careful selection of patients with remaining intact cartilage at the subtalar joint, adequate bone stock, and good compliance while in the majority of cases intra-articular malunion will rapidly lead to joint deterioration necessitating subtalar fusion at the time of correction [47]. Correction is carried out via the same approaches used for primary fracture fixation. For the classical joint-depression or tongue type fractures this is an extensile lateral approach with the patient positioned on the uninjured side [53]. Any implants introduced from the lateral side are removed. The subtalar joint is carefully freed from fibrous adhesions and the cartilage status is assessed by direct probing. The osteotomy is performed step-wise with small chisels along the former fracture as indicated by the preoperative CT scans. This requires an osteotomy at the angle of Gissane, a second behind the posterior facet, and a third osteotomy below the depressed lateral joint fragment, connecting the other two. The joint-bearing fragment is now derotated and elevated to the posterior facet of the talus that is used as a template. After temporary fixation with K-wires and fluoroscopic control of reduction, internal fixation is achieved with a lateral plate. The subthalamic bone defect is filled with either local bone graft or a corticocancellous graft from the anterior iliac crest [47].

Malunited calcaneal fracture-dislocations with remaining intact cartilage over the posterior facet of the subtalar joint are subject to the same osteotomy and three-dimensional re-alignment as in type IV malunions with arthritis as described above including a medial and plantar shift of the displaced calcaneal body with screw fixation to the sustentaculum fragment, peroneal tendons rerouting behind the lateral malleolus and suture of the superior peroneal retinacle [47].

Postoperatively, patients are restricted to partial weight-bearing in a below knee cast for six to 12 weeks postoperatively, depending on the individual bone quality and the amount of bone grafting. After radiographic union has been confirmed, weight-bearing is gradually increased in the patient’s own shoe and range of motion exercises are initiated.

Results

As early as 1921, Cotton described favourable results with an aggressive lateral exostectomy for malunited calcaneal fractures with expansion of the lateral calcaneal wall affecting subtalar motion and the peroneal tendons [45]. He combined this procedure with an extra-articular osteotomy, originally described by Gleich in 1893, for the treatment of flat feet and resection of symptomatic plantar heel spurs [54]. The subtalar joint was forcefully manipulated but not fused. Magnuson later duplicated Cotton’s favourable results, using a large bone wrench to mobilise the subtalar joint [55].

Kalamchi and Evans [56] proposed a modified Gallie fusion [50] of the subtalar joint via a posterolateral approach in which a portion of the lateral exostosis was excised and inserted posteriorly as autograft into the subtalar joint. They found that their technique allowed correction of heel valgus to neutral, and they reported good results in six patients. Carr et al. [39] reported on a first small series of subtalar distraction bone block arthrodesis. Good early results and correction of hindfoot alignment were seen in six of eight patients, one patient had a nonunion and two had varus malunions. Since then, numerous studies have reported union rates between 86 and 100 %, substantial correction of talocalcaneal height (five to 11 mm), patient satisfaction rates between 50 and 96 %, and significant improvement of the average AOFAS scores as compared to the preoperative values [44]. Correction of radiographic parameters correlated positively with the functional results including pedobarography.

Romash [48] reported satisfactory results in nine of ten feet with a multiplanar calcaneal osteotomy through the primary fracture line. We found this technique to be especially helpful in type IV and V malunions after calcaneal fracture dislocations and found substantial improvement in 12 cases with a 100 % union rate [41]. Clare et al. [49] reported the five-year results on 45 malunions in 40 patients treated according to the protocol by Stephens & Sanders [38]. The union rate was 92.5 %. All 45 feet were plantigrade and 43 (93.3 %) were aligned in neutral to neutral–slight valgus alignment.

Recently, we reported on five patients with intra-articular calcaneal malunions treated over a course of ten years with joint-sparing corrective osteotomy along the former fracture, soft tissue balancing, and secondary internal fixation at a mean of three months after the original injury [47]. At a mean of four-years follow-up, all patients were satisfied with the result and no secondary fusion was required. The AOFAS score improved significantly from 19 preoperatively to 81 at follow-up and radiographic parameters were corrected to near normal values.

Summary and conclusions

Hindfoot malunions resulting from malunited fractures, nonunions or necrosis of the talus and calcaneus regularly lead to severe disability and pain in the affected patients. A thorough preoperative analysis should reveal the source of pain, the exact three-dimensional outline of the malunion, the presence of post-traumatic arthritis, non-union, or infection, the extent of any avascular necrosis or comorbidities. The existing classification systems of post-traumatic talar and calcaneal malunions are easy to use and helpful in determining the optimal treatment. In properly selected, compliant patients with an intact joint cartilage, adequate bone quality, little or no AVN, a corrective osteotomy with secondary internal fixation preservation of the joints may be carried out. In the majority of cases, especially after intra-articular calcaneal fractures, axial realignment must be supplemented by an arthrodesis for manifest post-traumatic arthritis. Fusion is restricted to the affected joint(s) to minimise loss of function. Correction of the malunion is achieved by asymmetric joint resection, distraction and structural bone grafting, and corrective osteotomies for severe axial malalignment. Bone grafting is also needed after resection of a fibrous non-union, sclerotic or necrotic bone. Correction of the osseous deformity is supplemented by soft-tissue balancing around the hindfoot. Numerous clinical studies have shown substantial functional improvement and high subjective satisfaction rates from the reduction of pain and functional rehabilitation after corrective osteotomies and fusions for post-traumatic hindfoot malalignment.

References

- 1.Rammelt S, Winkler J, Heineck J, Zwipp H. Anatomical reconstruction of malunited talus fractures. A prospective study of 10 patients followed for 4 years. Acta Orthop. 2005;76:588–596. doi: 10.1080/17453670510041600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chan G, Sanders DW, Yuan X, Jenkinson RJ, Willits K. Clinical accuracy of imaging techniques for talar neck malunion. J Orthop Trauma. 2008;22:415–418. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e31817e83d9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canale ST, Kelly FB., Jr Fractures of the neck of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg (Am) 1978;60:143–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schuind F, Andrianne Y, Burny F, Donkerwolcke M, Saric O, Body J, Copin G, De Clerq D, Opdecam P, de Marneffe R. Fractures and dislocations of the astragalus. Review of 359 cases [in French] Acta Orthop Belg. 1983;49:652–689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rammelt S, Zwipp H. Talar neck and body fractures. Injury. 2009;40:120–135. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2008.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giuffrida AY, Lin SS, Abidi N, Berberian W, Berkman A, Behrens FF. Pseudo os trigonum sign: missed posteromedial talar facet fracture. Foot Ankle Int. 2003;24:642–649. doi: 10.1177/107110070302400813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rammelt S, Winkler J, Grass R, Zwipp H. Reconstruction after talar fractures. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11:61–84. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2005.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zwipp H. Chirurgie des Fußes. Wien New York: Springer; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rammelt S, Zwipp H, Schneiders W, Heineck J. Anatomical reconstruction after malunited Chopart joint injuries. Eur J Trauma Emerg Med. 2010;36:196–205. doi: 10.1007/s00068-010-1036-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zwipp H, Rammelt S. Posttraumatic deformity correction at the foot [German] Zentralbl Chir. 2003;128:218–226. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-38536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Daniels TR, Smith JW, Ross TI. Varus malalignment of the talar neck. Its effect on the position of the foot and on subtalar motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78:1559–1567. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199610000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sangeorzan BJ, Wagner UA, Harrington RM, Tencer AF. Contact characteristics of the subtalar joint: the effect of talar neck misalignment. J Orthop Res. 1992;10:544–551. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100100409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adelaar RS, Madrian JR. Avascular necrosis of the talus. Orthop Clin North Am. 2004;35:383–395. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2004.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vallier HA, Nork SE, Barei DP, Benirschke SK, Sangeorzan BJ. Talar neck fractures: results and outcomes. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:1616–1624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schwarz N, Eschberger J, Kramer J, Posch E. Radiologic and histologic observations in central talus fractures [German] Unfallchirurg. 1997;100:449–456. doi: 10.1007/s001130050141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindvall E, Haidukewych G, DiPasquale T, Herscovici D, Jr, Sanders R. Open reduction and stable fixation of isolated, displaced talar neck and body fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:2229–2234. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200410000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rammelt S, Zwipp H. Secondary correction of talar fractures: asking for trouble? Foot Ankle Int. 2012;33:359–362. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2012.0359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Langer P, Nickisch F, Spenciner D, Fleming B, DiGiovanni CW. In vitro evaluation of the effect lateral process talar excision on ankle and subtalar joint stability. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28:78–83. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sneppen O, Christensen SB, Krogsoe O, Lorentzen J. Fracture of the body of the talus. Acta Orthop Scand. 1977;48:317–324. doi: 10.3109/17453677708988775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cronier P, Talha A, Massin P. Central talar fractures–therapeutic considerations. Injury. 2004;35(Suppl 2):SB10–SB22. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kitaoka HB, Patzer GL. Arthrodesis for the treatment of arthrosis of the ankle and osteonecrosis of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:370–379. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.80B3.8383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee KB, Kong IK, Seon JK. Staged total ankle arthroplasty following Ilizarov correction for osteoarthritic ankles with complex deformities: a report of three cases. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30:80–83. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2009.0080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zwipp H, Rammelt S, Endres T, Heineck J. High union rates and function scores at midterm followup with ankle arthrodesis using a four screw technique. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:958–968. doi: 10.1007/s11999-009-1074-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hansen ST. Functional reconstruction of the foot and ankle. Philadelphia: Willliams & Wilkins; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hefti FL, Baumann JU, Morscher EW. Ankle joint fusion—determination of optimal position by gait analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1980;96:187–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00457782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Buck P, Morrey BF, Chao EY. The optimum position of arthrodesis of the ankle. A gait study of the knee and ankle. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:1052–1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thomas R, Daniels TR, Parker K. Gait analysis and functional outcomes following ankle arthrodesis for isolated ankle arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:526–535. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Braly WG, Baker JK, Tullos HS. Arthrodesis of the ankle with lateral plating. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15:649–653. doi: 10.1177/107110079401501204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Plaass C, Knupp M, Barg A, Hintermann B. Anterior double plating for rigid fixation of isolated tibiotalar arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2009;30:631–639. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2009.0631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chou LB, Mann RA, Yaszay B, Graves SC, McPeake WT, 3rd, Dreeben SM, Horton GA, Katcherian DA, Clanton TO, Miller RA, Van Manen JW. Tibiotalocalcaneal arthrodesis. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21:804–808. doi: 10.1177/107110070002101002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cierny G, 3rd, Cook WG, Mader JT. Ankle arthrodesis in the presence of ongoing sepsis. Indications, methods, and results. Orthop Clin North Am. 1989;20:709–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson EE, Weltmer J, Lian GJ, Cracchiolo A., 3rd Ilizarov ankle arthrodesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1992;280:160–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rammelt S, Pyrc J, Agren PH, Hartsock LA, Cronier P, Friscia DA, Hansen ST, Schaser K, Ljungqvist J, Sands AK (2013) Tibiotalocalcaneal Fusion Using the Hindfoot Arthrodesis Nail: A Multicenter Study. Foot Ankle Int. Apr 23. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Yu GR, Li B, Yang YF, Zhou JQ, Zhu XZ, Huang YG, Yuan F, Zwipp H. Surgical treatment of malunited or nonunited talus fractures [Chinese] Zhonghua Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2010;48:658–661. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dennis MD, Tullos HS. Blair tibiotalar arthrodesis for injuries to the talus. J Bone Joint Surg [Am] 1980;62:103–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suter T, Barg A, Knupp M, Henninger H, Hintermann B. Surgical technique: talar neck osteotomy to lengthen the medial column after a malunited talar neck fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2013;471:1356–1364. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2649-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hajipour L, Iftekhar F, Allen PF. Post-traumatic talectomy. A 60-year follow-up. Foot Ankle Surg. 2009;15:40–42. doi: 10.1016/j.fas.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stephens HM, Sanders R. Calcaneal malunions: results of a prognostic computed tomography classification system. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17:395–401. doi: 10.1177/107110079601700707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carr J, Hansen S, Benirschke S. Subtalar distraction bone block fusion for late complications of os calcis fractures. Foot Ankle. 1988;9:81–86. doi: 10.1177/107110078800900204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sangeorzan BJ, Hansen ST., Jr Early and late posttraumatic foot reconstruction. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1989;243:86–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rammelt S, Zwipp H. Arthrodesis with re-alignment. In: Coetzee JC, Hurwitz SR, editors. Arthritis and arthroplasty: The foot and ankle. Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier; 2009. pp. 238–248. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zwipp H, Rammelt S. Subtalar arthrodesis with calcaneal osteotomy [German] Orthopäde. 2006;35:387–404. doi: 10.1007/s00132-005-0923-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sanders R. Displaced intra-articular fractures of the calcaneus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000;82:225–250. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200002000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rammelt S, Grass R, Zawadski T, Biewener A, Zwipp H. Foot function after subtalar distraction bone-block arthrodesis. A prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:659–668. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.86B5.14205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cotton F. Old os calcis fractures. Ann Surg. 1921;74:294–303. doi: 10.1097/00000658-192109000-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dwyer FC. Osteotomy of the calcaneum for pes cavus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1959;41-B:80–86. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.41B1.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rammelt S, Grass R, Zwipp H (2013) Joint-preserving osteotomy for malunited intra-articular calcaneal fractures. J Orthop Trauma. Mar 19. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Romash MM. Reconstructive osteotomy of the calcaneus with subtalar arthrodesis for malunited calcaneal fractures. Clin Orthop. 1993;290:157–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Clare MP, Lee WE, 3rd, Sanders RW. Intermediate to long-term results of a treatment protocol for calcaneal fracture malunions. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:963–973. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.01603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gallie WE. Subastragalar arthrodesis in fractures of the os calcis. J Bone Joint Surg. 1943;25:731–736. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang PJ, Fu YC, Cheng YM, Lin SY. Subtalar arthrodesis for late sequelae of calcaneal fractures: fusion in situ versus fusion with sliding corrective osteotomy. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20:166–170. doi: 10.1177/107110079902000305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zwipp H, Rammelt S, Barthel S. Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) of calcaneal fractures. Injury. 2004;35(2 Suppl):46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benirschke SK, Sangeorzan BJ. Extensive intraarticular fractures of the foot. Surgical management of calcaneal fractures. Clin Orthop. 1993;292:128–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gleich A. Beitrag zur operativen Plattfussbehandlung. Arch Klin Chir. 1893;46:358–362. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Magnuson PB. An operation for relief of disability in old fractures of the os calcis. JAMA. 1923;80:1511–1513. doi: 10.1001/jama.1923.02640480015005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kalamchi A, Evans JG. Posterior subtalar fusion. A preliminary report on a modified Gallie’s procedure. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1977;59:287–289. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.59B3.330541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]